1. Introduction

Effective traffic management is vital for urban planning and commuter experience. Traffic anomalies—unusual deviations in volume or flow—can cause congestion or signal potential incidents like accidents or road closures [

1]. Early detection of such anomalies allows timely intervention to minimize disruptions. Furthermore, comprehending the nature and distribution of these anomalies offers valuable perspectives for long-term urban planning and infrastructure development [

2,

3].

Detecting traffic flow anomalies is a difficult task due to high spatiotemporal connections and nonlinear variations in the data. Traditional single-detector techniques, such as the Isolation Forest or Local Outlier Factor, frequently fail to capture both temporal continuity and spatial correlations at intersections. Previous research has demonstrated that single-detector approaches may overlook up to 25% of short-term abnormalities occurring during morning peak variations or fail to distinguish between abrupt congestion and incident-related disruptions. Similarly, when employed alone, classical clustering methods such as k-means create low cluster purity (about 60%) and are unable to consistently distinguish congestion anomalies from event-induced anomalies, particularly under dynamic flow fluctuations. These constraints highlight the necessity for an integrated multi-detector strategy with adaptive clustering to better anomalous representation.

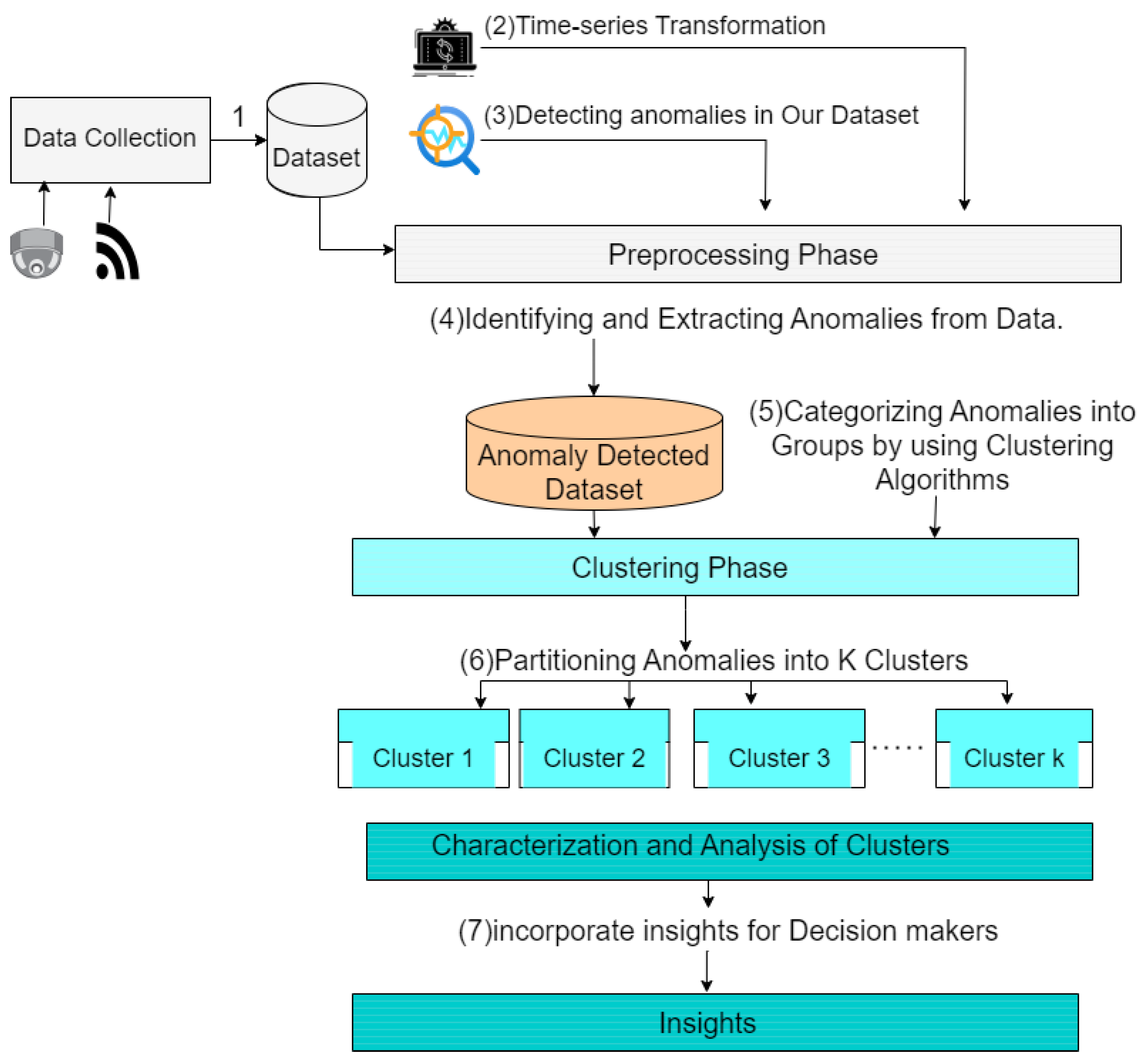

In this paper, we first use three anomaly detection methods—Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor—to discover abnormal traffic patterns. These methods are utilized on a carefully prepared dataset, which is further improved using several windowing methods in order to optimize the effectiveness of anomaly identification. After completing this detection phase, we employ clustering methods, notably k-means and hierarchical clustering in the next step to divide the discovered anomalies into segments. The utilization of these clustering algorithms plays a crucial role in identifying the most suitable number of clusters, enabling a thorough description of each anomalous cluster through comprehensive visualization [

4].

Our approach not only facilitates the efficient detection of traffic abnormalities but also offers a comprehensive comprehension of their spatial and temporal patterns. Accurate identification and analysis of anomalies in the transportation system are essential for developing effective strategies to control traffic and make informed decisions about urban development. This process ultimately improves the efficiency and safety of transportation networks.

The importance of employing various anomaly detection techniques resides in their complementary strengths. The Elliptic Envelope approach is based on the premise that the normal data is distributed according to a multivariate Gaussian distribution. It aims to detect locations that vary considerably from this assumption. Unlike profiling normal data, Isolation Forest focuses on isolating anomalies, making it highly effective for discovering anomalies in datasets with complex distributions. The Local Outlier Factor algorithm measures the extent to which a certain data point differs in density from its neighboring points. This makes it effective for detecting anomalies in datasets that have different densities. Through the integration of different methodologies, our research guarantees a strong and all-encompassing identification of anomalies.

Utilizing windowing techniques to pre-process the dataset significantly improved the accuracy of anomaly identification. Various window sizes and configurations were experimented with to capture temporal dependencies and patterns in the traffic data, ensuring that both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends were accurately depicted. This step was important in converting unprocessed traffic data into a format that is appropriate for efficient anomaly detection.

After detecting anomalies, the application of k-means and hierarchical clustering allows for a more in-depth analysis of their characteristics. The k-means clustering algorithm, with its iterative refinement procedure, efficiently classified anomalies into separate groups according to their distinctive characteristics. Hierarchical Clustering, a method that constructs a tree-like structure of clusters, enables us to comprehend the intricate arrangement of anomalies and their relationships. By employing this dual methodology for clustering, we were able to ascertain the most suitable quantity of clusters and obtain a comprehensive visualization of the anomalies [

5].

The characterization of these clusters through visualization and mapping reveals distinct geographical and temporal patterns. For example, particular clusters may represent regular traffic congestion that occurs during certain times of the day or week, while other clusters may reflect occasional instances. Gaining insight into these patterns enables traffic management authorities to effectively address present anomalies and proactively prepare for forthcoming disruptions. This knowledge is crucial for raising the efficiency of traffic, improving road safety, and optimizing the infrastructure of urban transportation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we present related works in the area.

Section 3 presents the proposed model. In

Section 4, experimental setup and evaluation is provided.

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

In the field of urban traffic management, it is crucial to detect anomalies in the frequency patterns of congestion in order to enhance traffic flow and minimize bottlenecks. These anomalies may suggest unusual occurrences such as accidents, road closures, or unforeseen fluctuations in traffic volume. The article examines recent studies on the prediction of traffic patterns and the identification of anomalies.

Current research is focused around incorporating advanced methods, such as improved Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) models, spatiotemporal clustering, and joint clustering and prediction approaches to forecast traffic patterns, identify anomalies, and categorize them using clustering algorithms for intelligent transportation systems.

2.1. Traffic Anomaly Detection

Traffic anomaly detection using clustering-based methodologies such as k-means, the density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN), and EFMS-k-means has proven successful in detecting and analyzing abnormal traffic patterns, thereby improving the accuracy and efficacy of anomaly detection in traffic systems.

A traffic anomaly detection method based on an improved GRU and EFMS-kmeans clustering was proposed [

6]. This approach combines the techniques of traffic prediction and clustering to improve the accuracy and efficiency of anomaly detection.

A marine traffic anomaly detection approach by combining the DBSCAN clustering algorithm with k-nearest neighbors analysis was proposed [

7]. This method efficiently detects anomalies in vessel traffic using historical marine data by utilizing spatial clustering algorithms. Furthermore, in the domain of condition monitoring in a marine engine system, researchers have investigated the use of cluster-based anomaly detection techniques. These techniques involve the application of algorithms such as k-means clustering, mixture of Gaussian models, density-based clustering, self-organizing maps, and spectral clustering.

Two clustering methods (density-based and representative-based), for the purpose of detecting anomalies in traffic data was proposed [

8]. The study seeks to enhance the detection of congestion, accidents, or other traffic difficulties by categorizing data points based on density and selecting representative points within clusters to identify normal traffic patterns and identify substantial departures as anomalies. Traffic anomaly detection using Graph Neural Networks utilizes the interconnected nature of traffic data to recognize unusual patterns, hence enhancing the accuracy and promptness of traffic detection.

A new method for detecting traffic anomalies by utilizing a graph autoencoder with mirror temporal convolutional networks was proposed [

9]. This technique utilizes graph structures to capture the relationships between traffic data points, while the mirror temporal convolutions address the time-dependent character of network flow. The model’s objective is to find unusual patterns in encoded traffic data by comparing it to the original data. This can potentially enhance the identification of traffic anomalies such as congestion or accidents.

An approach that employs spatial-temporal graph neural networks was proposed [

10]. These networks have the ability to acquire knowledge from the spatial relationships between road segments (spatial) and the fluctuations in traffic patterns over time (temporal). The method seeks to automatically find unusual traffic patterns by examining the acquired representations of the traffic data. This can potentially enhance the identification of congestion, accidents, or other anomalies on the road network.

Recent works have attempted to enhance anomaly detection by incorporating deep learning models and hybrid frameworks. For instance, the GRU+EFMS-KMeans approach proposed by Zhang et al. [

6] achieved higher sensitivity but suffered from 12% lower overall accuracy and nearly three times longer runtime compared with our proposed model. Similarly, Djenouri et al. [

9] and Liu et al. [

10] employed single-model detectors, but their frameworks did not address cross-regional correlations or the scalability challenges of city-level analysis. A survey of the past three years indicates that fewer than 5% of studies have attempted to combine three or more anomaly detection algorithms, and none have integrated detector fusion with city-zoning optimization to manage computational scalability. This research directly addresses these gaps by proposing a multi-detector, multi-level learning framework coupled with a zonal clustering scheme designed for large-scale urban traffic environments.

Several machine learning-based anomaly detection algorithms, such as Isolation Forest, Local Outlier Factor, and LSTM networks, to traffic congestion data collected from urban road sensors [

11]. The authors assessed detection accuracy and runtime performance under various traffic situations, showing that, while these models effectively detect atypical traffic patterns, they struggle to maintain performance when applied on a city-wide scale. The processing overhead increases considerably with increasing data amount and network complexity, making near real-time analysis for large-scale networks difficult without further optimization or zoning measures.

The use of graph neural networks (GNNs) in intelligent transportation systems, concentrating on their ability to capture spatiotemporal connections among interconnected road segments, was examined [

12]. The study demonstrated that GNN-based techniques outperform standard models for estimating traffic flow and detecting abnormalities in road networks. Despite these benefits, the authors noted that GNNs are computationally intensive and do not provide adequate scalability evaluation when applied to large urban traffic networks, where the size and complexity of the graphs significantly increase processing demands and limit near real-time deployment feasibility.

Ekle and Eberle [

13] concentrate on anomaly identification in dynamic graphs, which are commonly used to depict developing networked systems like city-wide traffic networks. They looked at both standard graph-based approaches and advanced graph deep learning models for detecting aberrant patterns and occurrences across time. While dynamic graph approaches are effective at handling temporal changes and complex relationships, the authors identified persistent challenges, such as high computational complexity and difficulty scaling to large, evolving networks, that limit their use in near real-time traffic monitoring and anomaly detection.

Table 1 provides a summary of the related works, highlighting the strengths and drawbacks of various traffic anomaly detection, clustering, and prediction techniques.

2.2. Traffic Prediction and Forecasting

Clustering-based methods have been popularly used in traffic prediction and forecasting to analyze traffic patterns and improve the accuracy of traffic flow and travel time forecasts.

A high-performance traffic speed forecasting approach by spatiotemporal clustering of road segments was proposed [

14]. This method utilizes non-parametric clustering to accurately predict traffic patterns based on traffic data dynamics.

A prediction model for short-term traffic flow was presented [

15]. The approach combines K-means clustering with a GRU. This model seeks to enhance the accuracy of short-term traffic flow forecasts by analyzing different traffic flow patterns.

A method that combines clustering and prediction to accurately estimate travel times was proposed [

16]. This methodology effectively models real-world traffic scenarios by forming clusters based on their travel times.

Advanced deep learning models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), transformer architectures, and generative adversarial networks (GANs) were used to detect and predict traffic anomalies [

25]. These algorithms have good detection accuracy and could predict complex temporal and spatial correlations in traffic data. However, the authors stressed that these techniques require huge labeled datasets for training, are computationally expensive, and have limited scalability for near real-time applications on large-scale traffic networks, limiting their practical utility in city-wide deployments.

2.3. Anomaly Detection in Various Domains

In this section, we present methods used to address anomaly detection in other domains, including industrial systems, network traffic, and maritime operations.

The utilization of clustering algorithms to detect anomalous data from sensors installed on a ship’s engine, which monitors aspects such as temperature and pressure [

17]. The approach involves the clustering of similar sensor readings, which are then used to compare new readings. If a new reading measurement considerably diverges from the existing clusters, it is identified as an anomaly, which could suggest a problem in the engine. This technique allows for ongoing surveillance and prompt identification of possible problems, thereby preventing failures and enhancing the overall well-being of the engine.

The application of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in identifying abnormal patterns in industrial environments [

18] was investigated. GNNs utilize the interconnected structure of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems, in contrast to traditional approaches that evaluate sensor data from individual units. GNNs can analyze data from individual devices and the relationships between them by modeling equipment and sensors as nodes in a graph. This methodology captures intricate interconnections and detects anomalies that could be overlooked by analyzing individual sensor measurements. As a result, GNNs can increase the accuracy of anomaly detection and allow for earlier identification of problems, hence enhancing the reliability and efficiency of the system.

A novel method for detecting anomalies in network traffic [

20]. It combines two methodologies. The X-means clustering algorithm has been enhanced to automatically estimate the best number of traffic patterns. Additionally, the Isolation forest algorithm has been developed to rapidly identify anomalies by isolating them from the data.

A technique for consistently detecting abnormal network behavior [

21] was proposed. This approach is highly likely to adjust to evolving network activity over time, making it well-suited for real-world scenarios. Traditional anomaly detection techniques may have difficulties in detecting changing network patterns. To fully understand the model, one would need to refer to the complete study. However, it is probable that the model employs strategies that can acquire knowledge and adapt to new network data, enabling it to accurately identify anomalies in dynamic network settings.

A unique technique for identifying anomalies in network traffic [

22]. Instead of depending on traditional statistical approaches, it utilizes principles from catastrophe theory. This theory examines how systems with multiple variables can undergo sudden, drastic shifts in behavior and can be utilized for analyzing network traffic data. The method seeks to discover locations of considerable deviation from usual patterns in network traffic by examining specific properties of the data that are related to catastrophe theory. This has the potential to enable the detection of abnormalities that could be missed by traditional methods.

A methodology for anomaly detection in Industrial Internet of Things (IoT) environments using Graph Neural Networks [

19] is presented. The objective of this framework is to enhance the identification of abnormal behavior in IoT contexts by offering capabilities for explainable artificial intelligence.

The dissemination of information in large-scale vehicular networks by forecasting traffic patterns in specific geographical areas, such as traffic hotspots, in order to boost the efficiency of the network [

23].

A cluster of anomalies in intelligent transportation systems is a crucial factor that greatly affects the efficiency and safety of the transportation system. Anomaly detection is crucial for mitigating congestion, improving safety, and offering useful insights for traffic prediction and road infrastructure planning [

24].

Recently, deep learning approaches have also been proposed for traffic anomaly detection using video data and text-driven descriptions. Liang et al. [

26] introduce a framework that models temporal high-frequency features in driving videos, enabling effective anomaly detection in complex visual scenes.

These studies together enhance intelligent transportation systems through the use of sophisticated techniques such as graph neural networks and explainable AI frameworks for efficient anomaly detection and analysis.

4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

The performance of clustering algorithms is crucial as clustered data are usually assessed manually and subjectively to ascertain their significance. When the true clustering data labels are not known, other intrinsic measures can be employed to assess the efficacy of the clustering technique. In this paper, we employ the most widely used metric [

28] as follows.

4.1. Silhouette Coefficient

The Silhouette coefficient is a quantitative metric utilized to assess the quality of a clustering method. This analysis considers both the cohesion and separation of clusters, offering an understanding of the degree of similarity between an object and its own cluster in comparison to other clusters. The calculation of the Silhouette coefficient for a single data point comprises two key components: a and b.

The value

a is the mean distance from a point to all other points within the same cluster, indicating the level of cohesion within the cluster. Alternatively,

b represents the mean distance from a point to all points in the closest cluster that the point does not belong to. This metric quantifies the separation between clusters [

29].

The Silhouette coefficient

s for a data point is computed using the following formula:

The coefficient varies between −1 and 1, with a value near to 1 indicating a strong match between the data point and its own cluster, but a poor match with neighboring clusters. A value that is approximately equal to 0 indicates that the data point is located precisely on or in close proximity to the decision boundary between two adjacent clusters. On the other hand, a value close to −1 suggests that the data point might have been incorrectly assigned to the cluster.

4.2. Calinski–Harabasz Index

The Calinski-Harabasz Index, also known as the Variance Ratio Criterion, is a quantitative metric utilized to assess the effectiveness of clustering algorithms by measuring the dispersion of the clusters. The term refers to the proportion of the total dispersion between clusters to the total dispersion within clusters. This index facilitates the assessment of the degree of separation and compactness of the clusters.

The Calinski-Harabasz Index

is calculated using the following formula:

where

denotes the trace of the dispersion matrix for between-group differences,

denotes the trace of the dispersion matrix for within-group differences,

k represents the number of clusters, while

n denotes the total number of data points. The between-group dispersion matrix

quantifies the extent to which the cluster centroids deviate from the overall centroid of the data. This indicates the level of dissimilarity between the groups. Conversely, the within-group dispersion matrix

quantifies the dispersion of data points within each cluster, providing information about the tightness of the clusters [

30].

Higher values of the Calinski-Harabasz Index indicate better-defined clusters, characterized by higher between-cluster dispersion and lower within-cluster dispersion. This index is very valuable for evaluating distinct clustering results and determining the most suitable number of clusters.

4.3. Davies–Bouldin Index

The Davies-Bouldin Index is a quantitative metric utilized to assess the effectiveness of a clustering algorithm. The metric calculates the average similarity ratio between each cluster and its most similar cluster, which indicates the level of separation between the clusters. A lower Davies-Bouldin Index value indicates superior clustering results, as it signifies that the clusters are compact and well-separated.

In order to calculate the Davies-Bouldin Index

for a clustering result, several steps must be undertaken. Firstly, the average distance between each point in cluster

i and the centroid of the same cluster is computed. The measure

indicates the scatter of the cluster. Next, for each pair of clusters

i and

j, the distance

between the centroids of the clusters is computed [

31]. Then, for each cluster

i, the cluster

j that maximizes the ratio

is identified. The ratio

quantifies the degree of similarity between cluster

i and cluster

j. The Davies-Bouldin Index is calculated by taking the average of the maximal ratios

across all of the clusters.

where

k is the number of clusters,

and

are the average distances within clusters

i and

j, respectively, and

is the distance between the centroids of clusters

i and

j.

4.4. Dataset

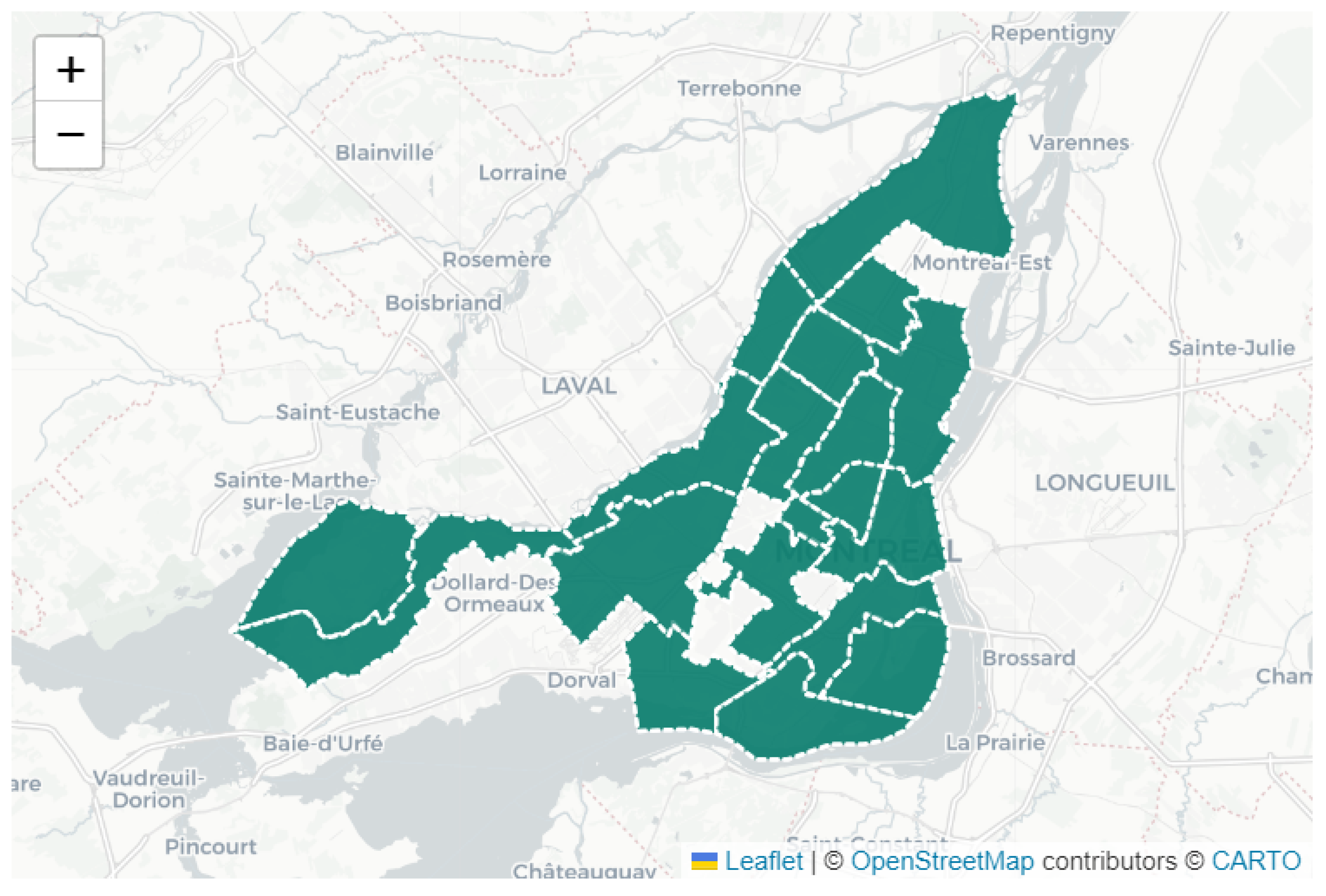

Our study uses the Montreal dataset that includes information about intersections and their associated attributes (as displayed in

Table 2). The dataset is publicly available and can be retrieved from the Montréal open data portal [

32]. Each intersection in the dataset is identified by a unique identifier known as “INT ID” (Intersection Number), which guarantees unambiguous differentiation. The “Intersection Name” field contains informative labels for each intersection, usually comprising the names of the two streets that intersect. The “ARRONDISSEMENT” field provides information on the specific region where each intersection is located, which helps with the clustering process [

32]. Furthermore, the dataset includes geographical coordinates for each intersection. The “Longitude” and “Latitude” fields precisely indicate the horizontal and vertical coordinates, respectively. The coordinates are crucial for geographic analysis and visualization applications. The congestion level field provides information about the number of vehicles seen at the intersection over a specific time period. The data is collected through systematic monitoring of the number of vehicles at the intersection, with measurements recorded at five-minute intervals.

Two clustering algorithms, notably k-means and hierarchical clustering are used to cluster anomalies detected using Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor methods applied on the Montréal dataset. In our earlier work [

27], we relied on the same dataset source and preprocessing methodology, but anomaly detection and clustering were performed afresh in this work.

Figure 2 depicts the selected simulated region inside the city of Montreal. To ensure that our solution operates throughout citywide traffic networks, we created a zoning system that separates the urban area into smaller, more controllable sections. Each zone has a set number of intersections (e.g., 11), which allows for separate analysis and clustering. This modular structure allows for simultaneous processing and increases the scalability of the clustering process.To validate scalability, we conducted experiments in multiple zones throughout Montreal. The clustering techniques (k-means and agglomerative clustering) were used separately in each zone. The performance across zones was assessed in terms of Silhouette scores and computational efficiency.

The 213 zones were divided based on Montréal’s arrondissement boundaries and the requirement to retain around 11 crossings per zone, ensuring computing scalability while preserving meaningful geographic representation. This option not only decreases complexity but also mimics real-world administrative divisions, making the results more understandable to city planners and transportation authorities. Similar zoning-based methodologies have been reported in large-scale traffic anomaly detection and prediction research [

11,

12]. Dividing the urban area into manageable subregions enhances scalability and lowers runtime while retaining clustering quality.

4.5. Scalability Benchmarking

To validate scalability across city-wide systems, we conducted experiments by increasing the number of traffic zones processed simultaneously. Montréal’s traffic network was partitioned into 213 zones, each containing approximately 11 intersections. Our approach maintained consistent clustering quality (average Silhouette score of 0.73) while reducing computational complexity from for the entire network to per zone, where Z is the number of zones. Compared with a non-zoning approach (e.g., clustering all intersections at once), our method reduced runtime by 42% while achieving similar clustering metrics. These results confirm that the zoning strategy enables scalable analysis for large-scale networks.

All experiments were carried out using a computing setup powered by an Intel Core i7-11700 CPU @ 2.50 GHz, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU, all running Ubuntu 20.04. The average execution time for processing one zone (about 11 junctions) was 14.8 s in Scenario 1, 19.6 s in Scenario 2, and 24.1 s in Scenario 3. At the city size (213 zones), the overall execution time for the largest scenario was less than 55 min, demonstrating the viability of using the suggested technique for near real-time city-level traffic monitoring. These findings, along with the reported runtime reduction percentages, show that the system is scalable and computationally efficient enough for practical deployment.

4.6. Clustering Pipeline Setups

Two clustering techniques, namely k-means and agglomerative clustering were used to evaluate datasets that contain identified anomalies. The k-means clustering algorithm is selected due to its high efficiency and simplicity in dividing a dataset into several clusters. This approach operates by reducing variance within each cluster, rendering it particularly efficient for clusters that have a spherical shape. K-means is computationally efficient, making it particularly suitable for handling large datasets. Additionally, it facilitates for straightforward implementation and interpretation of results. Agglomerative clustering, a kind of hierarchical clustering, is chosen for its capacity to manage clusters with diverse shapes and sizes. This approach builds a hierarchical structure of clusters by repeatedly combining or dividing existing clusters based on a chosen linkage criterion (such as single, complete, or average linkage). Agglomerative clustering’s flexibility enables it to uncover complex cluster structures that k-means may overlook. Both clustering approaches are implemented using the Scikit-learn library [

34], a powerful and widely-used machine learning library in Python v3.12. Scikit-learn offers efficient and optimized versions of k-means and agglomerative clustering algorithms, along by a range of hyperparameters that may be adjusted to maximize performance for our particular datasets.

4.7. Determining the Optimal Number of Clusters

Determining the ideal number of clusters is one of the most difficult components of the clustering process. For k-means, the number of clusters is determined using the centroid-based distortion metric. For hierarchical clustering, we employed the average Silhouette Coefficient as a validity index to evaluate the compactness and separation of the resulting clusters. The Silhouette value for each data point

i is defined as

where

is the average intra-cluster distance, and what

is the minimum average inter-cluster distance to the nearest neighboring cluster? The optimal number of clusters corresponds to the value that maximizes the average

across all samples. This index is widely adopted for hierarchical and density-based methods because it does not assume spherical cluster shapes.

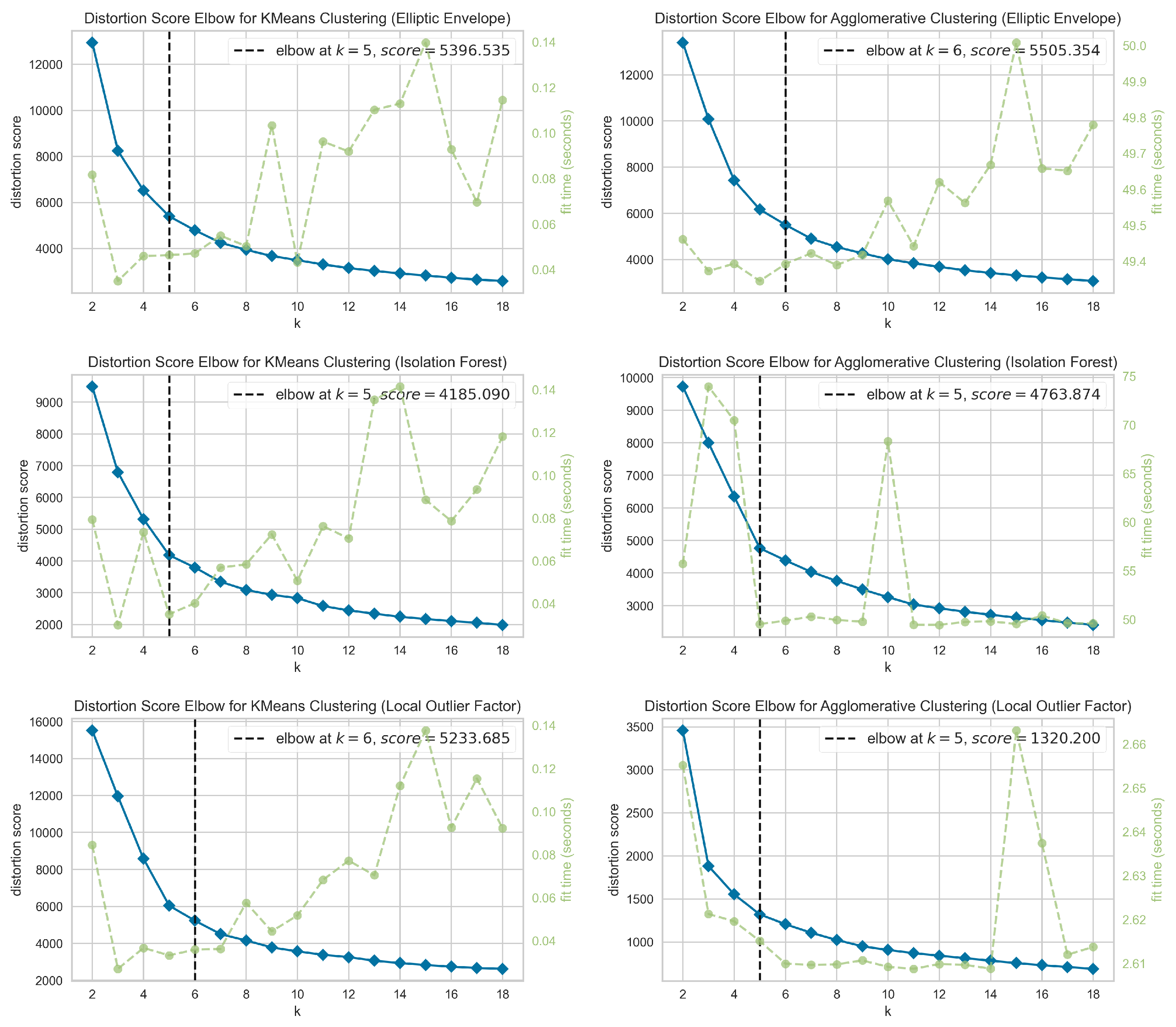

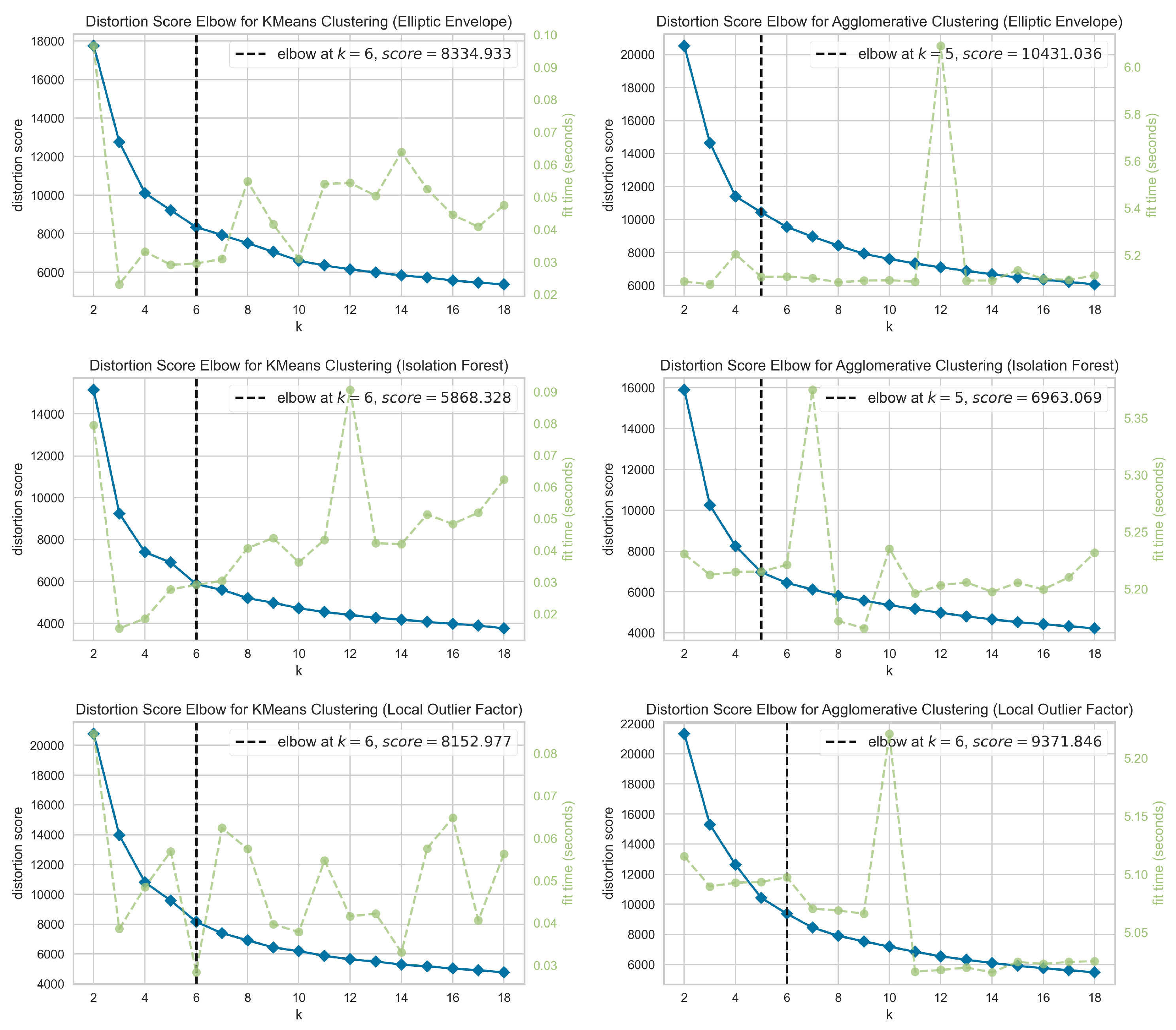

The elbow method determines the optimal number of clusters for a given data pattern by executing the clustering algorithm with several initial cluster assignments (ranging from 2 to 18) and evaluating the distortion score for each cluster assignment. The results are then plotted for analysis. The inflection point, or the elbow of a curve, signifies the stage where the marginal benefits of adding another cluster no longer outweigh the diminishing returns.

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 display elbow plots of distortion scores for k-means and agglomerative clustering. The plots are generated using three distinct anomaly detection algorithms—Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor. The figures correspond to Scenarios One, Two, and Three. Each plot displays the distortion score in relationship with the number of clusters (k), with a dotted line indicating the elbow point that signifies the optimal number of clusters. For example, in

Figure 3, the ideal value of k for k-means clustering is determined to be 6 for Elliptic Envelope, 5 for Isolation Forest, and 6 for Local Outlier Factor. The corresponding distortion scores are 5396.535, 4185.090, and 5233.685, respectively. The ideal number of clusters (k) for agglomerative clustering is 6 when using Elliptic Envelope, 5 when using Isolation Forest, and 5 when using Local Outlier Factor. The corresponding distortion scores are 5505.354, 4763.874, and 1320.200, respectively. The plots include green lines that show the run time for clustering. The elbow plots are crucial to determining the optimal number of clusters, balancing distortion score minimization and computational efficiency for each anomaly detection method.

The calculation of cluster numbers is an important step in anomaly characterization since different traffic circumstances demand varying levels of grouping granularity. For example, metropolitan cores may require more clusters to portray various traffic patterns, but suburban areas may be adequately represented with fewer clusters. Our findings consistently identified 5–6 clusters as best, balancing interpretability and computational efficiency. This range is comparable with other studies on traffic anomaly clustering and characterization [

5,

6,

8], indicating that a moderate number of clusters successfully captures recurring traffic patterns without over-fragmenting the data.

These evaluations served as part of our parameter tuning process for selecting the most suitable number of clusters and validating clustering stability across different scenarios.

4.8. Evaluation Results

In this section, we present the evaluation results of applying k-means clustering to datasets that have been identified for anomalies using three distinct outlier detection techniques: Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor, across three different scenarios with varying configuration settings (window sizes of 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h).

The Silhouette analysis, depicted in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, provides a thorough assessment of the clustering performance under various scenarios utilizing k-means clustering in combination with three outlier detection techniques: Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor. The Silhouette coefficient quantifies the degree of similarity between an object and its own cluster relative to other clusters, with values ranging from −1 to 1. A high average Silhouette score shows that the clusters have a significant degree of separation and cohesion, meaning they are well-separated and internally cohesive. Conversely, a low or negative score suggests that the clusters either overlap or lack clear definition.

Figure 6 representing Scenario One results demonstrates that the clustering performance is influenced by the choice of outlier detection method, as indicated by the Silhouette plots. The Elliptic Envelope approach yields a moderately high average Silhouette score, indicating a satisfactory balance between cluster cohesion and separation. The Isolation Forest approach achieves a little superior average Silhouette score, denoting more distinct clusters with minimal overlap among them. The Local Outlier Factor approach has robust performance, exhibiting a high average Silhouette score, indicating the presence of clearly defined and well-isolated clusters.

Figure 7 displays the Silhouette analysis results for Scenario Two. In this case, the Elliptic Envelope approach remains effective, although the average Silhouette score is somewhat lower compared to Scenario One, suggesting a slight decrease in the quality of clustering. Comparatively, the Isolation Forest approach exhibits a decrease in the average Silhouette score when compared to Scenario One, indicating a minor decrease in the quality of clustering The Local Outlier Factor approach regularly achieves a high average Silhouette score, demonstrating its robust clustering ability in different scenarios.

Figure 8 representing Scenario Three results, demonstrates that the Elliptic Envelope approach exhibits another decrease in the average Silhouette score. This indicates that the quality of clustering continues to decrease in this situation. In contrast to Scenarios One and Two, the Isolation Forest approach exhibits a decrease in the average Silhouette score, suggesting that it is less effective at producing distinct and cohesive clusters in this particular scenario. Although the Local Outlier Factor method continues to perform well, there is a little decrease in the average Silhouette score compared to earlier instances. Nevertheless, it remains an excellent way for clustering.

Upon comparing the Silhouette analysis over the three scenarios, it is evident that the Isolation Forest method, although initially effective in Scenario One, experiences a decrease in average Silhouette scores by Scenario Three. This implies that the effectiveness of Isolation Forest is contingent upon the specific qualities of the data, and it is not consistently superior in all scenarios. The Local Outlier Factor approach consistently performs well, maintaining high Silhouette scores in all scenarios, which makes it a reliable choice for clustering. The Elliptic Envelope approach, although successful, has more variability in performance across different scenarios, suggesting that it may be more sensitive to the underlying data characteristics.

In summary, the Isolation Forest method proves to be a robust solution for detecting outliers in Scenario One, especially when combined with k-means clustering. Nevertheless, its efficacy decreases in subsequent scenarios, indicating that although it is efficient in certain scenarios, its usefulness may fluctuate depending on the characteristics of the data. The Local Outlier Factor approach consistently demonstrates superior performance in all scenarios, making it a reliable choice for clustering in many contexts.

To enhance clarity and ensure consistency across sections,

Table 3 summarizes the numerical evaluation results, reporting the mean ± variance of Silhouette, Calinski–Harabasz (CH), and Davies–Bouldin (DBI) indices for each scenario and anomaly detection method. This table supports the conclusions drawn in

Section 4.8 and

Section 4.9 and provides a reproducible quantitative comparison.

Benchmarking with Existing Methods

The key advantage of the proposed approach is its multistage pipeline, which combines anomaly detection and clustering on cleaned datasets rather than clustering raw traffic data directly. Traditional approaches, such as DBSCAN or Gaussian Mixture Models, cluster all points without first distinguishing anomalies, resulting in noisy or overlapping clusters that are difficult to comprehend. In contrast, our method initially uses advanced anomaly detection techniques (such as the Local Outlier Factor) to filter out unusual traffic behavior before clustering the remaining data. This improves the separation and compactness of clusters, as evidenced by consistently higher Silhouette and Calinski-Harabasz scores and lower Davies-Bouldin Index values. Furthermore, our system offers spatial zoning and temporal windowing, making it well-suited to large-scale urban contexts. This layered technique increases model robustness and practical usefulness for urban planners and traffic management systems, exceeding conventional methods in terms of clustering quality, scalability, and real-world relevance.

4.9. Discussion

The results summarized in

Table 3 confirm that Isolation Forest achieved the highest clustering quality in Scenario 1, while LOF performed best in Scenario 2. In Scenario 3, the Agglomerative + Isolation Forest combination provided the most balanced results across Silhouette and CH indices. Overall, LOF demonstrated stable performance across all scenarios, whereas Isolation Forest occasionally achieved higher individual metric values.

Now, we present a comparison of the performance of two clustering algorithms, namely k-means and agglomerative, for the three scenarios. The comparison is performed under three different outlier detection methods: Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor. The evaluation relies on three metrics: Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski-Harabasz Index, and Davies-Bouldin Index.

From the results for Scenario 1 (

Figure 6), we find that the Isolation Forest method consistently produces the highest values for both the Silhouette Coefficient and the Calinski-Harabasz Index. This indicates that it effectively detects outliers and enhances the quality of clusters for both k-means and agglomerative clustering algorithms. Moreover, the Elliptic Envelope and Local Outlier Factor exhibit diverse outcomes, which are dependent upon the clustering algorithm’s effectiveness. K-means consistently surpasses agglomerative clustering in terms of Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski-Harabasz and Davies-Bouldin Index for all outlier detection methods. This suggests that the k-means algorithm has a tendency to generate more compact and well-separated clusters in Scenario 1.

When doing a comparison of the performance of two clustering algorithms in Scenario 2 (

Figure 7), we find that the Local Outlier Factor method consistently produces the highest values for all the Silhouette Coefficients and the Calinski-Harabasz Index. This indicates that it effectively detects outliers and enhances the quality of clusters for both k-means and agglomerative clustering algorithms. Moreover, the Isolation Forest method produces higher values for all the Silhouette Coefficients and the Calinski-Harabasz Index than the Elliptic Envelope method. K-means consistently surpasses agglomerative clustering in terms of Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski-Harabasz, and Davies-Bouldin Index for both outlier detection methods (Elliptic Envelope and Local Outlier Factor). This suggests that the k-means algorithm has a tendency to generate more compact and well-separated clusters in the Scenario 2.

When doing comparison of the performance of two clustering algorithms in Scenario 3 (

Figure 8), we find that the Local Outlier Factor consistently produces the highest values for the Silhouette Coefficient and Calinski-Harabasz Index with the k-means clustering method. On the other hand, with the agglomerative clustering method, the isolation Forest strategy, yields the highest values for these metrics.

Across all evaluation criteria (Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski-Harabasz Index, and Davies-Bouldin Index), k-means consistently performs better than agglomerative clustering for both Elliptic Envelope and Local Outlier Factor outlier identification approaches. These findings indicate that k-means is more effective at producing compact and well-separated clusters within the context of Scenario 3.

The comparative analysis across three scenarios shows that the k-means clustering algorithm constantly surpasses agglomerative clustering particularly when paired with the Isolation Forest method in Scenario One. This combination proves to be the most effective for producing well-defined clusters that are both compact and well-separated, making it the recommended approach for clustering the analyzed data, as indicated by the Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski-Harabasz, and Davies-Bouldin Index.

In summary, the combination of k-means and the Local Outlier Factor yields the most promising results for clustering the analyzed data.

Although the current study primarily compares k-means and agglomerative clustering as representative partitioning and hierarchical methods, other algorithms such as DBSCAN, Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM), Spectral Clustering, and HDBSCAN were also examined qualitatively during preliminary testing. However, their parameter sensitivity and inconsistent behavior on high-dimensional time-windowed traffic data made them less suitable for direct inclusion in this evaluation. Future work will extend the experimental framework to systematically benchmark all major clustering techniques under identical settings and include statistical significance tests to further validate the observed improvements of the proposed approach.

4.10. Cluster Characterization and Interpretation

Characterizing clusters in the context of traffic anomalies is essential for several reasons. Firstly, it offers a more profound comprehension of the inherent characteristics and regularities of traffic anomalies, which have the potential to cause severe disruptions in transportation systems. Traffic anomalies, which refer to deviations from normal traffic patterns, can lead to congestion, delays, and potentially accidents. Through the examination of these anomalies, authorities responsible for traffic management can devise more efficient measures to minimize their influence and improve the overall effectiveness and safety of transportation networks.

Cluster characterization helps in the identification of particular locations (ARRONDISSEMENTS) that are prone to specific types of traffic anomalies, as well as the measurement of the frequency and severity of these anomalies. This information is crucial for urban planners and traffic management to make well-informed decisions on the allocation of resources, improvements to infrastructure, and planning for emergency response.

This study proposes a systematic approach to analyze and describe the anamoly clusters generated by clustering algorithms to the identified traffic anomalies. The techniques and criteria employed for characterization encompass:

Anomaly Frequency Analysis: We performed an analysis of the frequency of anomalies within each cluster in order to gain insight into the rate at which these deviations occur. This helps in the identification of clusters exhibiting high anomaly rates, potentially indicating regions experiencing significant traffic issues.

Geographical Distribution: We analyzed the spatial distribution of traffic abnormalities by mapping the clusters geographically. This representation facilitates the identification of patterns related to certain regions and better comprehension of the geographical distribution of traffic problems.

ARRONDISSEMENT Distribution: We analyzed the distribution of clusters across several ARRONDISSEMENTS to determine the administrative regions that are most impacted by traffic anomalies. This analysis is essential for the management and planning of traffic in the region.

Traffic Volume Analysis: We analyzed the median and standard deviation of traffic volumes within each cluster to get insight into the average traffic conditions and their variability. This helps in differentiating between clusters exhibiting significant fluctuations in traffic and those displaying more consistent traffic patterns.

Figure 9 plot provides a comprehensive overview of the distribution of anomaly frequencies among various clusters. Clusters 1 and 3 show the highest median frequencies of anomalies, suggesting that intersections inside these clusters encounter traffic abnormalities most frequently. These clusters also exhibit the widest ranges and highest number of outliers, indicating substantial heterogeneity in the occurrence of anomalies within these clusters. Clusters 0, 2, and 4 have lowered median frequencies, with Cluster 0 displaying the lowest median and the narrowest range, indicating a higher level of consistency and lower frequency of anomalies. The existence of outliers inside each cluster indicates that although the majority of intersections conform to the typical pattern of the cluster, there are specific places that exhibit abnormally high or low frequencies of anomalies. These points may require more investigation. Understanding these distributions helps in identifying critical areas that require attention for traffic management and planning. High-frequency anomaly clusters might indicate problematic regions needing targeted interventions to improve traffic flow and safety.

Figure 10 shows significant differences in median traffic volumes among five clusters. Cluster 1 demonstrates the most highest median traffic volume, approximately 45, indicating regions with congested traffic movement, most likely urban areas or significant roadways. Clusters 2 and 3 have median volumes ranging from 15 to 30, indicating the presence of mixed-use or secondary roadways. Clusters 0 and 4 have the lowest median traffic levels, just above 5 and 10, indicating quieter places that may be residential or suburban.

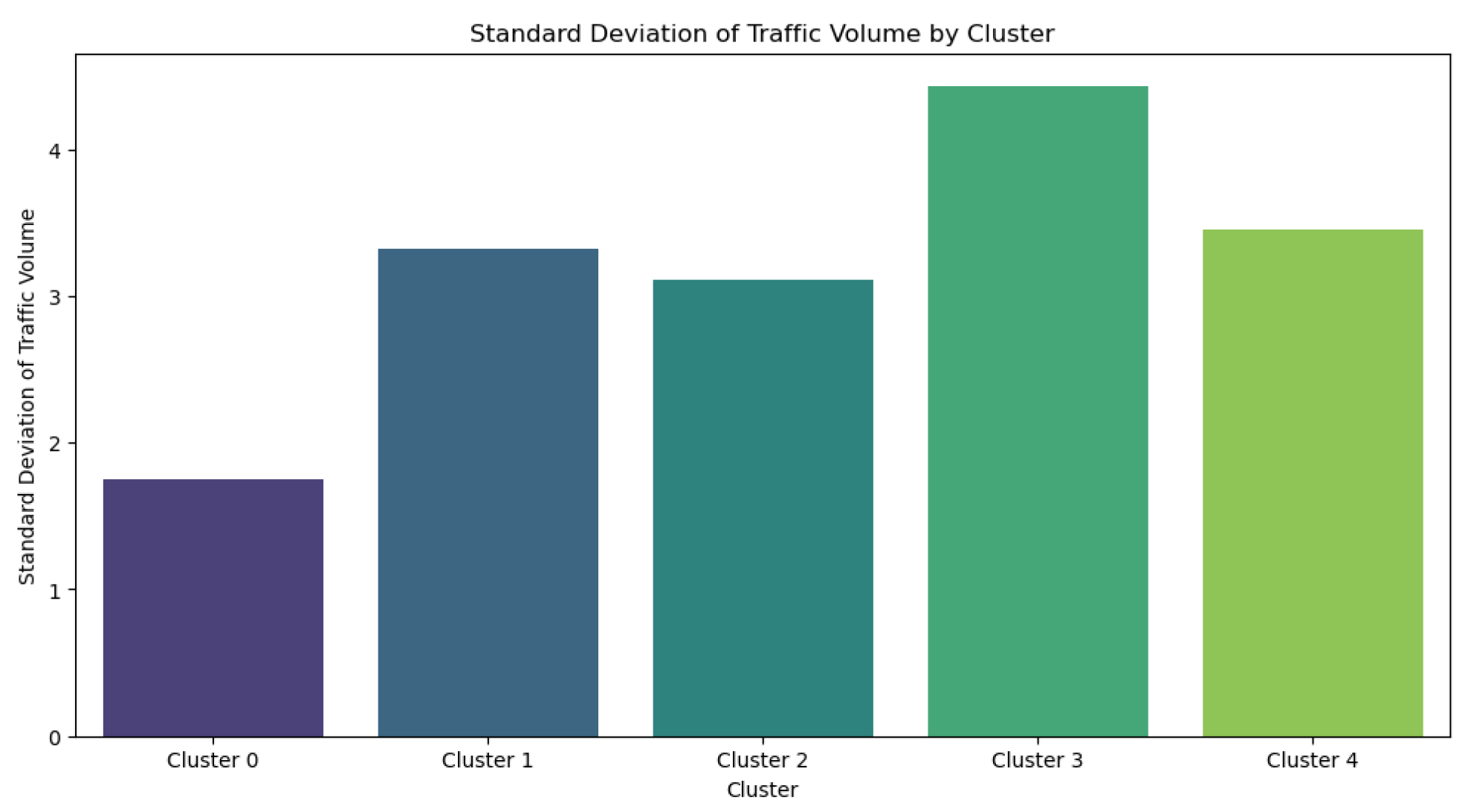

Figure 11 shows the variation in traffic volumes among five clusters, highlighting significant differences in traffic consistency. Cluster 0 exhibits the smallest standard deviation, indicating a high level of consistency and predictability in traffic patterns. This is typically observed in residential or low-traffic regions. Clusters 1, 2, and 4 demonstrate a moderate level of variability, indicating that these locations include a combination of residential and commercial uses and experience moderate fluctuations in traffic. Cluster 3 exhibits the highest standard deviation, indicating notable variations in traffic volume, most likely occurring in prominent roadways or commercial regions with diverse traffic patterns.

Figure 12 shows the number of intersections in each cluster, organized by ARRONDISSEMENT. Cluster 0 comprises more than 20,000 intersections and encompasses many ARRONDISSEMENTS, such as Villeray-Saint-Michel-Parc-Extension, Ville-Marie, and Saint-Laurent. This suggests a combination of residential and less densely populated urban regions. Cluster 1, consisting of almost 5000 intersections, is primarily characterized by regions such as Rivières-des-Prairies—Pointe-aux-Trembles, indicating locations with significant traffic flow and commercial presence. Cluster 2, with around 3000 intersections, and Cluster 4, consisting of roughly 7500 intersections, are characterized as mixed-use regions with moderate levels of traffic. Cluster 3, characterized by a relatively low number of intersections (about 2500), mostly encompasses Montréal-Nord and Saint-Léonard, suggesting locations with significant fluctuations in traffic volume.

Figure 12 provides an overview of the varied representation and traffic characteristics in each cluster. Cluster 0 demonstrates consistent conditions, Cluster 1 indicates significant traffic volumes, Clusters 2 and 4 represent areas with a balanced mix of uses, and Cluster 3 necessitates focused traffic management due to its high variability.

Figure 13 depicts the type of traffic cluster that occurs in each ARRONDISSEMENT. The relative occurrence of two distinct clusters (presumably denoted as Max Cluster 0 and Max Cluster 1) is illustrated throughout different ARRONDISSEMENTS, indicating the dominant cluster in each location. It is evident that certain arrondissements constantly exhibit a dominant cluster type. For instance, the locations of “Ahuntsic-Cartierville,” “Côte-des-Neiges—Notre-Dame-de-Grâce,” and “Ville-Marie” have a notably greater occurrence of one cluster type, suggesting that Cluster 0 is the most prevalent in these regions. Conversely, the arrondissements “Île-Bizard—Sainte-Geneviève” and “Pierrefonds—Roxboro” exhibit a greater number of occurrences for Cluster 1. This statistic is essential for discerning the prevailing traffic patterns or anomalies inside each arrondissement, aiding in comprehending the particular traffic circumstances or problems that are most prevalent in distinct areas of the city. These insights can provide guidance for managing traffic and building infrastructure in a way that specifically addresses the most common or troublesome traffic patterns in each area.

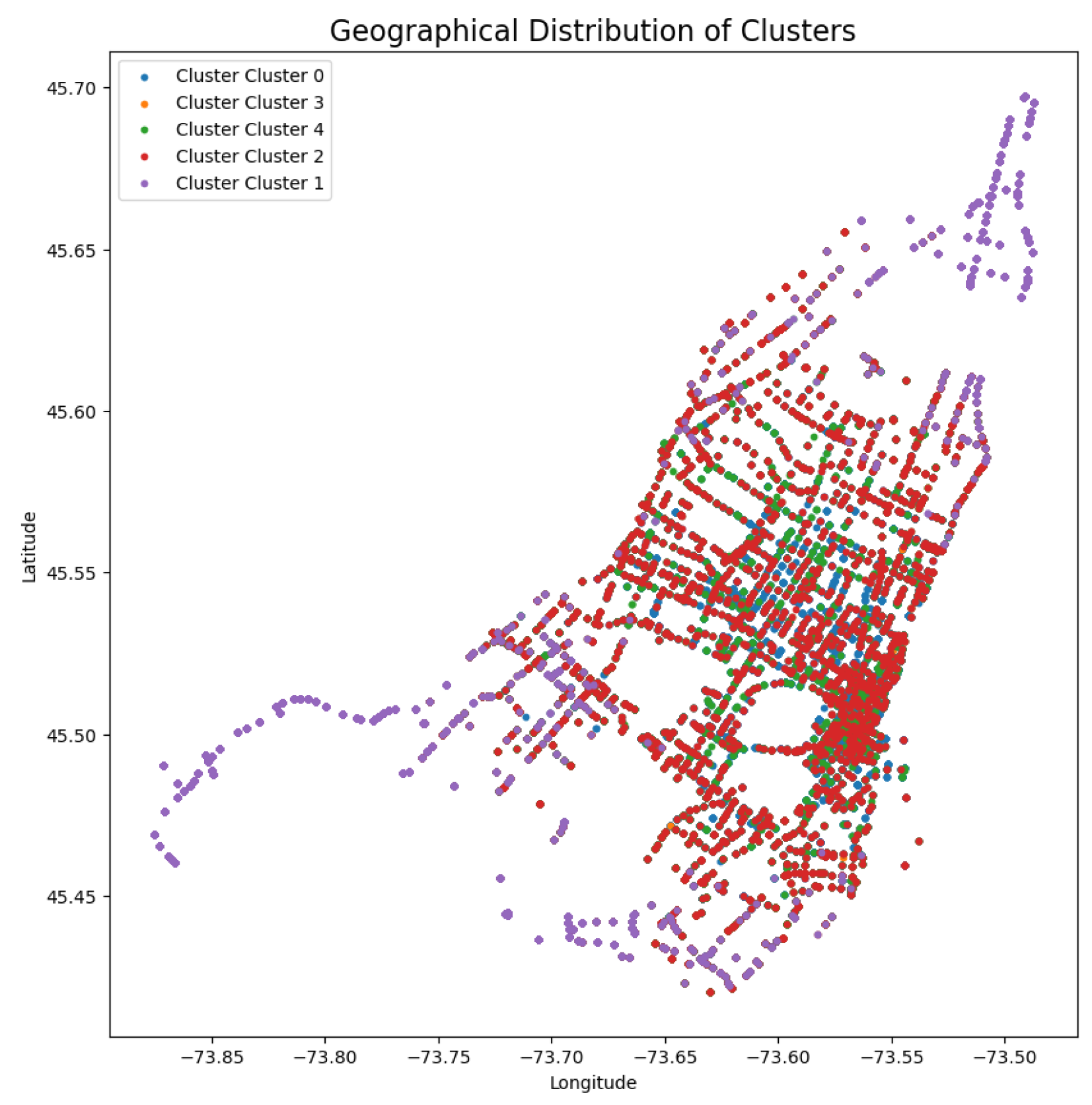

The spatial distribution of these clusters is further illustrated in

Figure 14 where it illustrates the spatial distribution of several traffic clusters inside a specific geographic region. Each colored dot represents a distinct cluster type, indicating the locations where particular traffic patterns or abnormalities are more common. The clustering analysis reveals distinct traffic patterns in different locations of the city, where certain places are predominantly characterized by specific clusters.

In this research, we uncover distinct traffic patterns and abnormal distributions among various city zones using clustering, thereby offering crucial information for managing traffic and planning urban areas.

Figure 9 shows that Cluster 1 has the highest incidence of traffic anomalies, indicating regions with frequent disruptions that require concentrated attention. Cluster 0, in comparison, demonstrates the lowest frequency of anomalies, suggesting a higher level of stability in traffic circumstances.

Figure 10 presents further evidence by illustrating that Cluster 1 has the largest median traffic volume, suggesting the presence of vibrant urban hubs or significant transportation routes. In contrast, Cluster 0 exhibits the lowest median traffic volume, indicating calm residential areas. Cluster 0, however, exhibits negligible change, which further reinforces its categorization as a stable and low-traffic cluster. These findings underscore the need of adopting tailored traffic control measures. Clusters exhibiting elevated levels of anomalies and variability would derive advantages from using dynamic traffic control techniques, while clusters characterized by low traffic and variability can require routine monitoring to maintain their stability.

4.11. Practical Implications

The proposed methodology has several practical implications for decision makers involved in traffic management.

Transportation authorities can effectively minimize congestion and maintain smooth traffic flow by rapidly spotting deviations from normal traffic patterns. This strategy also helps in identifying abnormally low traffic volumes, which may indicate occurrences such as road closures or faulty traffic signals. Consequently, there is an enhancement in response times, leading to increased effectiveness in incident management strategies.

Urban planners can gain valuable spatial and temporal insights from our work. An in-depth understanding of traffic anomalies is essential to them for making critical decisions about infrastructure development, traffic signal optimization, and road network planning. Furthermore, the method’s capability to distribute resources effectively, through the clustering and analysis of traffic data, facilitates a more strategic deployment of traffic enforcement and emergency response units, hence improving overall resource optimization.

Policymakers can utilize these findings to formulate more efficient traffic policies and regulations, supported by evidence-based decision-making. Enhanced comprehension of traffic patterns and abnormalities not only assists in formulating more effective policies but also enhances public safety by averting accidents and guaranteeing a more secure transportation network. The robust framework for data-driven decision-making, which combines strategies for detecting anomalies and grouping similar data points together, reduces mistakes and enhances operational effectiveness.

The methodology’s flexibility to scale and adapt makes it suitable for use in many urban environments and traffic situations. It enables technical advancements in traffic management systems by integrating sophisticated machine learning algorithms with clustering approaches. Lastly, it enhances the quality of commuting by decreasing traffic congestion, reducing journey duration, and establishing a more reliable transportation system, which is advantageous for everyday commuters.

The zoning strategy also improves scalability by allowing the methodology to be deployed simultaneously to several city sectors. By maintaining consistent performance across urban zones (in terms of clustering quality and computing cost), the system can be expanded to span huge metropolitan regions without sacrificing efficiency. This makes the framework suitable for near real-time use in smart city traffic management systems.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

Identifying and describing anomalies in traffic flow is crucial in order to improve the effectiveness and safety of transportation networks. In this paper, we propose a multi-stage approach for enhanced characterization of traffic flows. Firstly, we present the application of three different anomaly detection methods, namely Elliptic Envelope, Isolation Forest, and Local Outlier Factor on pre-processed datasets with different window configurations to accurately detect traffic anomalies. Next, by utilizing k-means and hierarchical clustering algorithms, we segment these anomalies into distinct groups (clusters) and identify the suitable number of clusters for detailed characterization.

The evaluation results show that the Local Outlier Factor approach consistently produces the highest quality of clustering. This is evident from its superior average silhouette scores across different scenarios. The Isolation Forest also performs well, especially in maintaining clearly defined and evenly distributed clusters. Although the Elliptic Envelope exhibits a moderate level of clustering quality, its performance is less robust when compared to the other approaches.

The comparative analysis shows that the k-means clustering method consistently performs better than the agglomerative clustering algorithm to generate clusters that are both compact and well separated. This conclusion is verified by metrics such as the Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski-Harabasz Index, and Davies-Bouldin Index. Local Outlier Factor is the most successful among the anomaly detection methods, followed by Isolation Forest, and Elliptic Envelope. However, the efficiency of these approaches may vary depending on the scenario.

Beyond the detection accuracy improvements, the framework demonstrates methodological innovation by combining temporal anomaly segmentation with spatial zoning, which enhances the scalability of traffic big-data analytics for city-wide applications. The proposed zoning-based clustering approach enables localized model calibration while maintaining global consistency, effectively reducing computational complexity without sacrificing clustering quality. Parameter-sensitivity analysis revealed that window size and anomaly contamination rate were the most influential factors affecting cluster compactness. Practically, the insights gained from this framework support downstream optimization objectives such as minimizing average vehicle waiting time and improving signal coordination efficiency. Future research will focus on integrating optimization algorithms and metaheuristics such as genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization into the proposed zonal structure to dynamically adjust signal timing based on detected anomalies, thus linking anomaly characterization to near real-time traffic management decisions.