Abstract

The rise in energy demand of Electric Vehicles (EVs) is an increasing burden on the grid. Solutions proposed to reduce grid load, for example, storing surplus energy from EVs, are costly and do not address associated challenges such as communication reliability and the optimum number of charging stations. This paper proposes an optimized energy management by availing supply from EVs and renewable resources for achieving net zero. We consider that EVs sell their surplus energy via bidirectional Vehicle-to-Grid exchange. Demand and supply from EVs and energy output from renewables are intelligently predicted and shared with the grid through a 5G communication network. A cost minimization solution alters grid supply according to available EV supply. This paper analyzes the upper bounds of EV demand and supply, utilizes game theory to incentivize EVs, and discusses the optimum number of charging stations. Results show that the proposed solution reduces 38.21% of the grid load and 5.3% cost.

1. Introduction

A net zero balance is typically defined as the state in which at least as much energy is available for the consumers in a region as required with no or negligible CO2 emissions [1]. It refers to achieving a balance between the amount of energy consumed and the amount of renewable energy produced. Apart from generation of renewable energy from clean sources, another way to achieve the goal of zero emissions on the road is the use of Electric Vehicles (EVs) [2]. This is why EVs are becoming an essential part of road transportation. According to the International Energy Agency, the expected number of EVs on the road is 120 million by 2030 [3], which can potentially lead to a surge in energy demand. Consistent energy supply to the increasing number of EVs is becoming a serious challenge for electricity grids, particularly if the aim is to achieve net zero by providing supply from clean energy sources only. Recent research presents solutions to achieve net zero and reduce the burden on main power grids by extensive exploitation of microgrids, but they require substantial set up and installation cost. Their supply from renewable sources also fluctuates, mainly due to the dependency on weather parameters [4]. Other solutions to maintain reliable supply include optimizing charging schedules of EVs by determining peak demand hours [5,6,7,8] and adopting bidirectional vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology to store excess energy from EVs during off-peak periods [9]. However, temporal prediction of demand from EVs to determine peak hours is largely affected by outliers, such as unusual incidents and reduced travel during COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, battery storage systems are costly and degrade with time. Therefore, achieving the net zero goal despite the wide use of EVs is a huge challenge.

Another promising solution to achieve net zero is prosumerism, where consumers offer their surplus energy in exchange for some incentive [1]. Prosumerism is enabled by V2G technology, which allows EVs to discharge their battery energy to the grid as well as other consumers or EVs. Prosumerism does not require installation time and cost and can be readily implemented. However, it is essential to encourage prosumers to take part in energy exchange. Usually, they are encouraged through various incentive strategies which make sure that both buyers and sellers earn profit or feel a level of satisfaction after energy exchange.

The incentive strategies in prosumerism are commonly analyzed using game-theoretic approaches [10]. Optimized pricing strategies have also been proposed to support prosumerism [11]. However, its impacts on the main grid and net zero have not been thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, despite the extensive research on prosumerism, its feasibility still encounters some practical challenges. One of the challenges is to find the practicality of prosumerism when EVs are traveling at high speeds on longer routes. Also, existing solutions do not emphasize the role of regulation authorities to encourage prosumerism and impose penalties on emissions and the importance of consistent coordination and communication among grid, distributed resources and prosumers. Grid regulation, prosumer incentives, and demand and supply forecasting have been separately studied. This paper proposes a consolidated approach for real-time regulation.

Despite significant progress in smart grid research, several practical challenges persist in implementing V2G and prosumer-based energy management at scale. Real-world grid operations face issues such as unpredictable EV mobility patterns, unreliable communication links, fluctuating renewable outputs, and the absence of a unified regulatory framework for incentivization. Moreover, coordination between distributed energy resources and grid operators often lacks real-time adaptability, leading to inefficiencies in energy balancing and cost allocation. The proposed model directly addresses these challenges by integrating predictive communication-aware energy management with game-theoretic incentives and dynamic grid cost optimization, thereby enabling a more resilient and economically viable path toward net-zero energy systems.

The main contributions of this paper are:

- We present a unified optimization framework that integrates prosumer incentives, grid cost minimization, and emission reduction to achieve a net zero transport energy system.

- The model incorporates both communication and computational constraints, deriving upper bounds for EV demand and supply and determining the optimum number of charging stations for scalable implementation.

- A game-theoretic incentive mechanism is developed to encourage cooperative EV participation, where Nash equilibrium and Pareto optimality confirm the stability of cooperation.

- Simulation and theoretical analyses demonstrate that the proposed framework reduces grid load by 38.21% and total cost by 5.3%, while cutting CO2-related costs by over 50% compared with fossil-fuel-based supply.

Unlike conventional V2G frameworks that primarily focus on bidirectional energy transfer or static scheduling of EV charging, our approach integrates economic incentivization, grid cost optimization, and communication-aware energy coordination into a unified control model. The novelty lies in treating prosumer participation not as an auxiliary feature but as an intrinsic component of grid optimization, governed by game-theoretic cooperation and regulatory incentives. This consolidated framework allows the grid to adaptively adjust supply based on real-time EV behavior and renewable generation forecasts, thus bridging the existing gap between incentive design and operational grid efficiency. Moreover, by explicitly analyzing the upper bounds of EV demand and supply, and the optimum number of charging stations, the proposed method extends beyond classical V2G optimization to address infrastructure scalability and regulatory feasibility within a net zero context.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses related works. The system modeling is described in Section 3. Section 4 formulates the proposed economic model for EVs’ incentivization and optimization problem for grid cost minimization. Performance evaluation is discussed in Section 5, followed by conclusion in Section 6.

2. Related Works

2.1. Energy Management and Optimization Strategies

Optimized strategies for effective energy management involving EVs have been proposed in literature with various objectives. Digital twin-based energy optimization during a disaster is proposed in [12]. In [5,6], the charging schedule of EVs is optimized according to peak hours to minimize the charging price for EVs. The positive impact of pricing strategy according to the time of day on both transportation and energy system is presented in [7]. In [8], the charging times of EVs are considered for the pricing strategy utilized by the grid. Its objective is to reduce the grid load by utilization of a differential game model for economic benefits. In [13], grid load reduction is achieved by two approaches; bidirectional EV charging through V2G and time-based charging price management. The battery storage system to store surplus energy from EVs through bidirectional V2G technology is proposed in [9]. It employs a peak shaving strategy to reduce grid load. The concept of environmental protection is introduced in [14] by imposing a penalty charge to users for per unit mass of CO2 produced due to energy generation. The Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP)-based optimization problem is solved to reduce costs and grid load by regulating charging schedules in [14].

2.2. Prosumerism and Game-Theoretic Analysis

Bidirectional Peer-to-Peer (P2P) energy exchange is evolving as a potential solution to maintain demand–supply balance [15,16]. With the increase in distributed energy generation and P2P trading, energy sellers are not only traditional generation companies but can also be independent prosumers. Also, the consumers have multiple needs and applications, including EVs, portable smart devices and homes. As a result, conventional decision-making methods to buy energy are no longer sufficient to address the complexities of multi-entity decision-making. In this context, game theory emerges as a highly suitable tool for tackling decision-making challenges in the energy system [17]. Incentivized prosumerism in EVs supported by game theory is presented in [1,10,11]. The theoretical probability of a successful energy exchange is analyzed in [1]. In [18], it is concluded that long-term success of the incentive strategy depends upon sustained motivation. The amount of energy shared by an EV in a non-cooperative game is also analyzed in [19] using prospect theory which models the behavior of a rational EV prosumer.

2.3. Limitations in Related Works

The current energy management strategies do not analyze the associated infrastructure, i.e., the required number of battery storage systems or charging points. This paper stochastically determines the optimum number of charging stations to attain the maximum number of prosumers. Furthermore, the game-thoeretic approaches usually assume ensured participation of EVs when their utilities are positive. This paper considers that EVs can also be selfish and may not choose to participate despite having surplus supply. Therefore, this paper proposes EV incentives specifically to discourage selfish behavior. Also, the maximum extent of participation, i.e., the upper bound of surplus supply is not evaluated in existing literature.

A net zero solution requires integration of both energy management and prosumerism, which are usually studied separately. This paper presents a consolidated solution comprising incentives for EVs, penalty charges to reduce CO2 emissions and theoretical analysis matched with numerical data to show the extent of demand covered by prosumerism. Contrary to related solutions which have limited objectives, this paper aims to cover multiple goals, as shown in Table 1. Combining many objectives in the proposed solution collectively presents the positive impact of optimized prosumerism on multiple systems including energy, transport, economy and society, which can potentially lead to policy-making and practical implementation at a practical stage.

Table 1.

Objectives of energy management and optimization strategies.

As summarized in Table 1, prior studies have advanced individual objectives such as grid load reduction, pricing optimization, or EV utility enhancement. However, these works often treat the economic, infrastructural, and regulatory dimensions in isolation. For example, refs. [5,6,7,8,9] optimize charging schedules without addressing how incentives influence prosumer participation, while [10,11] focus on incentive design but overlook grid-level cost dynamics and communication constraints. In contrast, our work integrates these interdependent aspects through a unified optimization and incentivization model that jointly minimizes grid cost, enhances prosumer cooperation, and accounts for communication and infrastructure scalability. This critical synthesis bridges the methodological and practical gaps evident in prior literature, positioning the proposed framework as a comprehensive step toward real-world net zero implementation.

3. System Modeling

We consider a 5G architecture involving cellular base station (BS). All entities including the main grid, EVs, BSs, wind, and photovoltaic (PV) energy sources are able to communicate with each other. EVs are assumed to be incorporated with bidirectional chargers. The proposed system provides a solution to the energy demands of EVs during their journeys. Therefore, it requires seamless and timely communications between BSs and EVs. In this scenario, a 5G cellular network adequately provides ultra-reliable and low-latency communication support to the system [20].

3.1. System Architecture

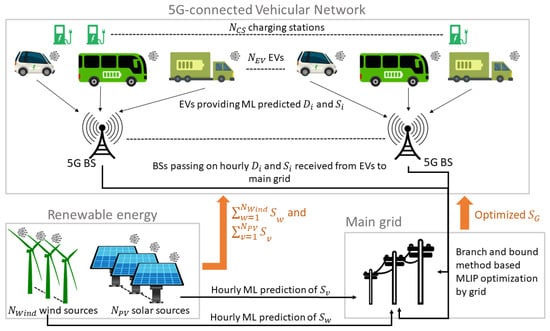

As shown in Figure 1, the system architecture consists of sources providing supply to EVs, including a main grid supplying , and , and number of wind and PV energy sources, each supplying an hourly amount of and , respectively. The wind and PV sources predict their hourly and through machine learning (ML) models and share with the main grid so it can adjust its accordingly. The output of these ML models is the amount of energy produced by wind and PV sources in the next hour. The input for predicting wind energy output consists of day, time, wind speed, and wind direction at a particular location. The input for predicting PV energy output consists of day, time, air temperature, cloud opacity, dew point, precipitation, relative humidity, wind direction, wind speed, zenith, and solar radiance.

Figure 1.

The proposed architecture of optimized energy management.

The vehicular network includes 5G BSs, number of EVs which can communicate with the BSs and number of charging stations where EVs can charge or discharge. Each EV i calculates its energy demand and the amount of surplus supply which it can offer for the next hour according to its ML-based predicted velocity on a planned route, and notifies the BS within its communication range. Therefore, the accumulated demand and supply of the network can be defined as and for each seller EV i with and for each buyer EV i with . The main grid optimizes its to minimize its cost according to the accumulated demand and supply information received from EVs via BSs, and wind and PV sources.

3.2. Modeling of EVs’ Demands and Supplies

The proposed solution utilizes ML to initially estimate the velocity changes of an EV i on a planned route. The output of the ML model is the velocity of the EV and the input dataset includes its position, lane, angular direction of movement, maximum speed of road, and number of nearby vehicles. A mathematical model to calculate energy consumption from velocity changes is followed [21].

Firstly, the total spatial length of a planned route is divided into K equal instances such that . After the velocity prediction at an instant k, i.e., by the ML model, its traction force is computed as , where is road grade, is air density, and , , , and is mass, frontal area, rolling resistance coefficient, aerodynamic drag coefficient, and acceleration of EV i, respectively. The total energy consumed on a planned route is obtained by multiplying energy at each instant k with estimated total time of a route, where instantaneous energy can be obtained by dividing by the energy conversion efficiency of an EV. The remaining State of Charge (SOC) after its journey is , where is its current SOC. An EV i calculates its demand as

where is the minimum SOC limit. If is below , the EV i needs energy to charge itself up to a level depending upon . is the maximum limit up to which an EV i charges itself. The available is

where denotes the percentage of which an EV i offers as . It can choose according to various decision parameters, such as, the length of time it can invest or altruistic motivation to contribute towards net zero [1].

3.2.1. Bounds of Supply and Demand

Let follow lognormal distribution with mean and variance . Then, the probability and are and , respectively. When and , the upper bounds can be defined as

where x represents EV type, i.e., car, bus or lorry and is the probability of occurrence of an EV type x on the road.

3.2.2. Expected Number of Prosumers per Charging Station

Assuming that is the average distance of an EV i to its nearest charging station and the number of charging stations are uniformly distributed on a road of length . Then is the total number of charging stations. The expected number of EVs supplying energy per charging station can be modeled using Poisson distribution, i.e., where is the arrival rate of seller EVs. For buyer EVs, is large and a normal approximation to Poisson distribution can be applied with mean [22]. Therefore, the expected number of demanding EVs per charging station is .

4. EVs Incentivization and Grid Cost Optimization

4.1. Model Assumptions and Limitations

To maintain analytical tractability and focus on the optimization and incentive framework, several simplifying assumptions were made in the modeling process. First, the vehicle-specific energy efficiency factor was fixed at 20%, representing an average conversion efficiency across heterogeneous EV types, as commonly adopted in prior studies. Second, the communication layer assumes ideal 5G connectivity with ultra-reliable low-latency performance (URLLC), ensuring negligible delay during control signal transmission. Third, the travel cost component was modeled as a simplified function of distance and energy expenditure, abstracting from route-specific congestion and stochastic driving behavior. While these assumptions are reasonable for controlled simulations, they may lead to slight deviations when applied to real-world traffic networks with variable communication conditions and dynamic efficiency factors. Future work will incorporate adaptive calibration, stochastic communication delays, and empirically derived travel cost functions to enhance realism and generalizability.

4.2. Economic Model for EVs Incentivization

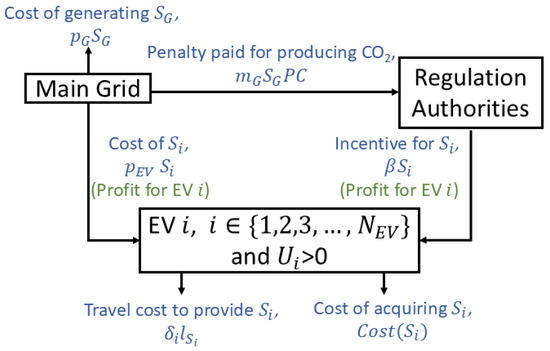

The utility of EV i is , where is the price paid by the grid for selling and is the incentive paid by the regulation authorities to EVs for acting as prosumers. is the distance that EV i has to travel to provide , is the per unit energy consumption rate, includes the cost of acquiring and battery degradation cost [1].

Game Formulation

We analyze the strategy of an EV i to offer in exchange of in a game-theoretic context. The payoff of an EV player i depends upon its own action as well as the action of other EV players. The actions and payoff are:

Actions

An EV player i has two possible actions: cooperative () by offering or non-cooperative () if it does not have or does not offer .

Payoff

Table 2 shows the payoff of EV players according to their actions, where represents the road tax imposed by regulation authorities. To encourage prosumerism, the road tax reduces to if , where denotes the number of EVs playing cooperatively and is the threshold number of players. The road tax reduces for both cooperative and non-cooperative players to ensure fairness, because a non-cooperative player is not necessarily selfish and may not have enough available to offer.

Table 2.

Payoff of EV i with as per other EVs action.

We prove the following statements to analyze motivating capability of the game for player i to take cooperative action.

Proposition 1.

Playing cooperative () is the best response action of a player i if .

Proof.

If then also, . In this case, a player i will always get a positive payoff if it chooses . If it chooses , it will always get a payoff less than or equal to . Therefore, is the best response action of player i irrespective of the actions of other players. □

Proposition 2.

The action set is both Pareto-optimal and the Nash equilibrium of the game.

Proof.

Table 2 shows that no player can get the maximum payoff by deviating from the action set . Every player gets the highest payoff by playing honestly only. Therefore, the action set is both Pareto-optimal and the Nash equilibrium of this game. □

An offered by a player i may not always be availed by the grid as the optimization problem prioritizes grid cost minimization instead of . If a grid has already obtained sufficient supply from a certain number of EVs it may not buy from player i. In such case, even if it has chosen action. Therefore, a player may become motivated to play selfishly and choose action resulting in the same payoff. It will ultimately discourage prosumerism. Theorem 1 is presented to prevent this condition.

Theorem 1.

A player i will not conspire to act selfishly, even if it finds out that or more choose .

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

4.3. Grid Cost Optimization

The optimization problem aims to minimize the cost of electricity generation by the main grid. The incurring costs are shown in Figure 2. The grid cost is defined as

where is the cost of generating , is the per unit mass of CO2 released to produce and is the penalty charge paid by the grid to regulation authorities for producing per unit of CO2. For net zero, it is necessary that

where is the transmission loss that occurs while providing . Each EV i shares its estimated and as defined in (1) and (2), respectively, with the nearby BS. The BS sends the aggregated information to the grid.

Figure 2.

Costs and profits of main grid and EV.

Problem Formulation

The optimization problem is

where constraint C1 represents that the grid is able to supply energy up to a certain upper limit, i.e., and C2 represents the net zero goal. Algorithm 1 defines the solution carried out by the main grid to solve Problem 1 by utilizing a branch and bound method based on the MILP framework. The motivation to exploit the branch and bound method is its suitability with the combinatory nature of the problem defined above, where there is a finite set of available . The branch and bound method creates a search space tree with each node containing a combination of information and attempts to find an optimal solution. This method offers a lower time complexity than other MILP solutions [23].

| Algorithm 1 Cost Minimization by Main Grid. |

|

5. Performance Evaluation

Building on the theoretical formulation and optimization model presented in Section 3 and Section 4, this section evaluates the proposed framework through numerical simulations under realistic traffic and renewable generation conditions. The goal is to empirically validate how the integrated prosumer incentivization and grid optimization mechanisms perform in diverse operating scenarios. Simulation experiments are designed to reflect both controlled theoretical parameters and stochastic real-world factors such as traffic density and renewable output variability. This transition from analytical formulation to simulation-based validation provides a coherent assessment of the model’s practical feasibility and scalability.

In the simulation, three types of electric vehicles, cars, buses, and trucks are modeled with distinct battery capacities, charging/discharging rates, and energy demands as summarized in Table 3. These parameters are aligned with standard manufacturer specifications and empirical studies on EV fleet operations. Passenger cars exhibit moderate power exchange levels with frequent connection intervals, while electric buses operate with higher power but lower frequency due to scheduled charging cycles. Trucks, on the other hand, contribute large-capacity energy transfers but with longer idle periods between operations. These behavioral differences influence the aggregated grid response: cars primarily affect short-term grid fluctuations, buses provide predictable high-volume energy exchanges, and trucks contribute to long-term balancing stability. The model’s optimization layer accounts for this heterogeneity through dynamic weighting factors in the objective function, ensuring that the collective charging–discharging behavior remains stable and cost-efficient across all EV types.

Table 3.

EV specifications.

To ensure methodological robustness, all model parameters were calibrated through a combination of empirical data, standard references, and iterative validation. Physical and operational constants such as aerodynamic coefficients, rolling resistance, and vehicle mass were derived from manufacturer specifications and validated against benchmark studies in EV energy modeling [21]. The learning rates, penalty coefficients, and incentive factors (for example, , , and ) were tuned using a grid-search procedure to achieve convergence between simulated and expected grid load responses under different traffic densities. Additionally, the renewable generation parameters were validated against publicly available datasets from London’s wind and solar records [24] to reflect realistic environmental variability.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of key parameters on the optimization outcomes. Variations of ±10% were applied independently to , , , and to assess their effects on grid cost and prosumer participation rates. Results indicated that was most sensitive to changes in and , while prosumer participation was primarily influenced by and travel distance . However, the system maintained stable performance within these bounds, confirming that the proposed model is resilient to moderate parameter perturbations. This calibration and sensitivity evaluation enhance the reproducibility and practical applicability of the proposed framework.

5.1. Simulation Setup

We analyze the performance of the proposed solution using Python 3.9 and relevant open-source libraries including sci-kit, PuLP, catboost, xgboost, lightgbm, and tensorflow. The simulation parameters and EV specifications used are listed in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively, which align with other EV standards [21]. A 20 km long highway road consisting of three lanes with three types of EVs including car, bus, and lorry is simulated in the Simulation of Urban Mobility framework for data collection. The motivation of simulating highway traffic is due to the higher average speed of vehicles on highways as compared to streets, which leads to increased energy consumption. In this way, the proposed solution can be envisioned for situations when the average demand is high. The maximum speed limits of vehicles on a highway are set as 112.65 km/h for cars and buses, and 96.56 km/h for lorries. and are randomly generated by lognormal probability distribution with variance of 1 and mean of 10 km and 6 km, respectively [25]. The road traffic is categorized into three traffic situations, i.e., light, medium, and heavy, corresponding to , and , respectively. Results are averaged over 100 simulation runs. For wind and PV energy output, an open-source data of day, time, wind speed, wind direction, air temperature, cloud opacity, dew point, precipitation, relative humidity, zenith, and solar radiance in the city of London is used [24].

Table 4.

Simulation parameters.

To ensure the realism of the simulation outcomes, the proposed framework was partially validated using publicly available empirical datasets and benchmark trends. The predicted renewable energy profiles were compared with measured wind and photovoltaic outputs from the Renewables.ninja platform [24], showing less than 6% deviation in monthly mean energy generation. Similarly, the EV velocity predictions were benchmarked against the real-world dataset used in [21], confirming consistent Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) ranges for vehicle motion under similar traffic conditions. While full-scale empirical validation would require deployment in a live vehicular network, these benchmark comparisons demonstrate that the simulated dynamics of grid cost reduction and prosumer participation are aligned with observed operational behavior in existing EV and renewable systems. This cross-verification increases confidence in the practical relevance and scalability of the proposed model.

Furthermore, the current simulation framework considers a single 20 km test corridor to isolate the performance of the proposed optimization under controlled conditions. While this configuration effectively captures localized energy exchange dynamics, it does not yet represent inter-regional energy flow or complementarity between zones (e.g., suburban surplus energy supporting urban demand). This simplification was adopted to emphasize model validation and algorithmic stability before extending to multi-region analysis. Future extensions will incorporate spatially distributed nodes, enabling the study of large-scale energy reallocation between regions and assessment of network-level coordination strategies.

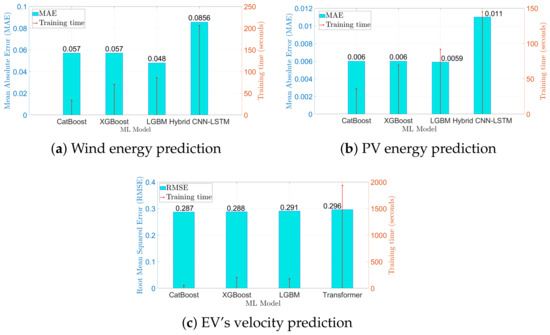

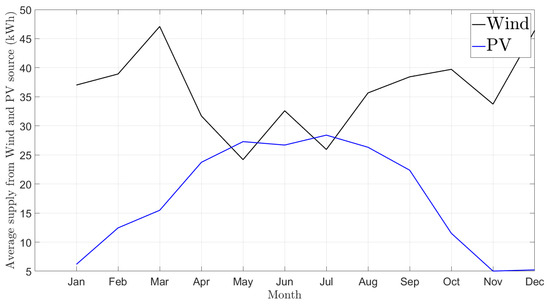

5.2. Comparison of ML Models

Figure 3 shows the performance comparison of ML models analyzed to predict wind, PV energy, and velocity of EVs. ML models including CatBoost [26], XGBoost [27], LGBM [28], and a custom hybrid network based on Convolutional Neural Network–Long Short Term Memory (CNN-LSTM) are analyzed for wind and PV energy output. CatBoost outperforms all other models in training speed. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of CatBoost is on par with the lowest MAE by LGBM for wind and PV energy prediction. For velocity prediction of EVs, a transformer learning model is also compared [21]. The RMSE of the Catboost model is the lowest among all ML models for velocity prediction of EVs, as shown in Figure 3c. Figure 4 shows the average monthly wind and PV output. The wind energy fluctuates throughout the year but is slightly higher in winter months of London. The PV energy is significantly higher in summer than winter, when the dependent parameters such as air temperature and solar irradiance are raised.

Figure 3.

Performance comparison of ML models.

Figure 4.

Wind and PV energy output, .

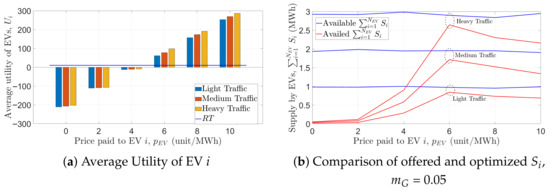

5.3. Utility of EVs and Optimal Number of Charging Stations

Figure 5 shows the effect of on of EV i. It can be seen in Figure 5a that rises proportionally with . However, due to the cost minimization objective of Problem 1, a grid does not opt to avail if it has to pay high , contributing to increased . Therefore, the maximum benefits of prosumerism can only be achieved at an optimum , which is shown in Figure 5b. A maximum of 86.7%, 87.7%, and 91.27% of total available surplus energy from EVs can be used with light, medium, and high traffic densities, respectively. Figure 6a shows the impact of on and resulting number of . With increasing , the EVs have to pay more travel cost, which results in a low or negative . A low results in small . For low travel cost, it is important that a charging station is nearby. The optimal number of charging stations according to is shown in Figure 6b.

Figure 5.

Effect of upon supplying by EV i.

Figure 6.

Effect of upon and optimum .

5.4. Contribution of EVs as Prosumers

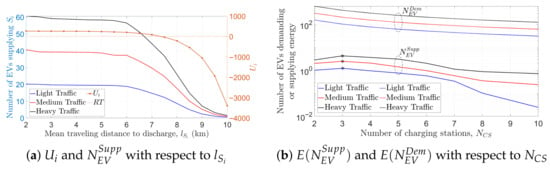

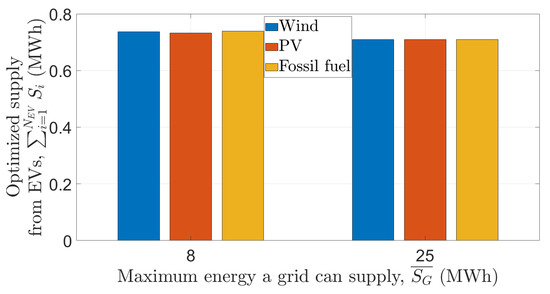

Figure 7 shows the impact of energy source on optimized prosumerism. If a grid provides fossil fuel-based , it aims to minimize its cost by buying more from an EV i instead of paying . The optimized is 69.63%, 69.78%, and 99.79% of the total surplus energy available in EVs with wind, PV, and fossil fuel energy, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effect of grid energy source on prosumerism.

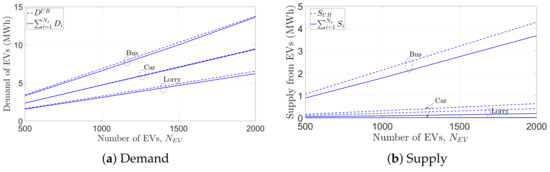

Figure 8 shows the amount of contribution made by prosumerism when the grid generates energy from a wind source which has least emissions. At , the EVs can fulfill a maximum of 11.29%, 11.47%, and 11.82% of during light, medium, and heavy traffic, respectively.

Figure 8.

Contribution of prosumerism to optimized supply, kg, .

Additionally, the impact of prosumerism also depends upon the maximum supply available at the grid, i.e., , which can be seen in Figure 9. On average, the optimized from EVs is 26.67 MWh higher when MWh as compared to MWh with . Therefore, it can be concluded that prosumerism can play an effective role when the demands of EVs are very high, which cannot be met by the grid alone.

Figure 9.

Effect of on prosumerism.

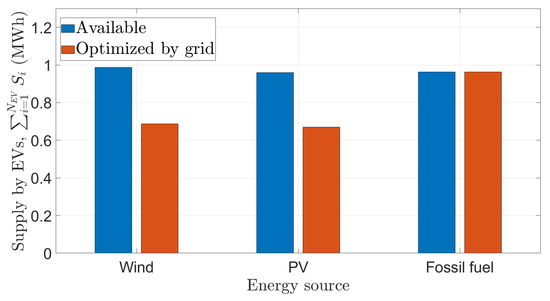

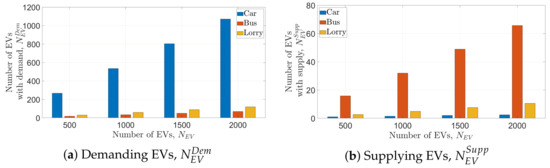

5.5. Demand and Supply According to EV Type

Figure 10 shows the distribution of demand and supply according to the types of EVs. The theoretical upper bounds and derived in Section 3 match with the simulations. and estimations can be used to estimate energy demand and supply if a BS loses connectivity with EVs. As shown in Figure 10a,b, an electric bus has the highest demand and supply due to its largest battery capacity. A lorry has the lowest demand. An electric car, with the smallest battery capacity, can contribute the least in supplying . The number of demanding and supplying EVs are shown in Figure 11. The number of cars with is the highest and with is the lowest, as shown in Figure 11a and Figure 11b, respectively. On the contrary, the number of buses with is the lowest among all EV types and with is the highest.

Figure 10.

Average demand and supply with respect to EV type.

Figure 11.

Average number of EVs demanding or supplying energy.

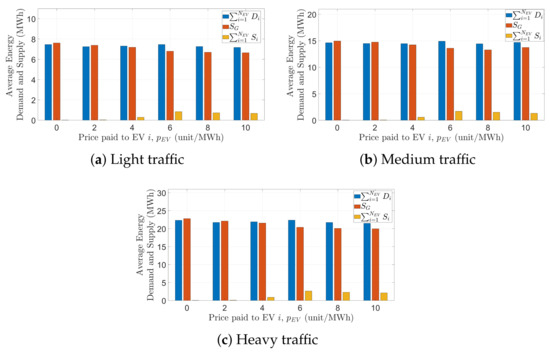

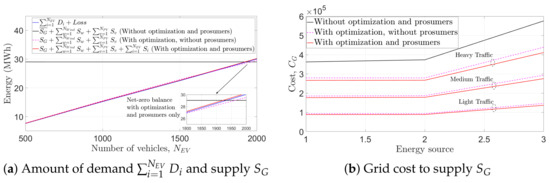

5.6. Reduction in Grid Load and Cost

Figure 12 shows the comparison of the proposed solution without optimization and/or prosumerism. As shown in Figure 12a, with no optimization and prosumerism, a grid will provide a constant irrespective of , which is a significant waste of resources and cost when is low. Also, in case of high , without optimization and prosumerism may not be able to achieve demand-supply balance. Optimization without prosumerism also fails to achieve demand–supply balance in heavy traffic. The supply is sufficient only when optimization is accompanied with support from EVs. Figure 12a shows that, in heavy traffic, the net zero balance is only achieved by our proposed solution. Figure 12b compares the impact of the proposed solution on , which is highest without optimization and prosumerism. Optimization without prosumerism can reduce . However, the proposed optimized solution combined with prosumerism results in a further average reduction of 5.3% in . Also, the renewables result in 50.97% lower average cost than fossil fuels.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the proposed solution without optimization and/or prosumerism.

To provide further insight into the collective energy dynamics, the contributions of individual EV categories to supply–demand balancing were also examined. Analysis revealed that electric buses, owing to their higher battery capacity and predictable charging cycles, served as the dominant surplus suppliers, contributing approximately 46% of total discharge energy during peak demand periods. Passenger cars, although smaller in capacity, influenced short-term fluctuations through frequent plug-in events, accounting for about 38% of total bidirectional exchanges. In contrast, electric lorries provided long-duration discharging support, contributing the remaining 16%, primarily stabilizing overnight load profiles. These differentiated behaviors confirm that the heterogeneous EV fleet collectively enhances system resilience—with buses ensuring energy availability, cars maintaining short-term responsiveness, and lorries stabilizing long-duration demand gaps.

Table 5 compares the results in terms of grid load reduction with other approaches. The proposed solution reduces grid load by 38.21% compared with the load without optimization and prosumerism. Significant results utilizing battery storage systems are obtained in [9]. However, battery storage systems are costly and require maintenance due to battery degradation. Our proposed solution saves on the cost of battery storage systems, which can be invested into infrastructure such as installation of 5G BSs. As an added advantage, the scope of the proposed 5G infrastructure is not only limited to energy management but can also be used in various applications requiring ubiquitous connectivity. In terms of cost reduction, the proposed solution not only reduces grid cost but also eliminates the cost incurred in the regular maintenance of battery storage systems. Furthermore, the infrastructure cost can potentially be a fruitful investment due to various other emerging computing applications of 5G.

Table 5.

Average percentage decrease in grid load.

5.7. Communication and Computation Complexity

Table 6 compares the asymptotic communication and computation complexities of the proposed solution with other approaches utilizing a 5G network. Peer-to-peer communication of EVs in a non-cooperative game setting is presented in [1,10], resulting in an increased communication and computation overhead. The demanding and supplying EVs negotiate their energy demands and prices themselves to maximize their utilities in [1], whereas, in [10], each demanding EV sends energy requests to selling aggregators which share charging slots for EVs, thereby running two communication rounds. For computation, each demanding EV selects the most suitable seller in [1,10], resulting in increased computation complexity. On the contrary, the aggregator-based communication and optimization is proposed in [11] for V2G energy exchange to centrally manage energy exchanges and reduce communication and computation. Similarly, in our proposed solution, the BS collects demand and surplus energy information from EVs once and the grid runs the optimization algorithm. Table 6 shows that both solutions governed by 5G communications result in the least communication and computation overhead. Although the complexities increase with , the rise is not drastic as in [1,10]. Since the proposed solution performs optimization on an hourly basis and is assumed to run in a pre-defined area, the increase in can be managed by allocating sufficient computing resources to each BS during implementation.

Table 6.

Asymptotic communication and computation complexities of energy trading approaches among EVs.

Although the proposed 5G-enabled optimization framework demonstrates low communication and computation overhead, several practical constraints should be acknowledged. Communication latency, particularly in areas with limited 5G coverage or high network congestion, could introduce minor delays in real-time data exchange between EVs and base stations. However, these delays are expected to remain within the sub 10 ms range typical of 5G ultra-reliable low-latency communication (URLLC), which is tolerable for hourly grid optimization cycles. Another potential constraint is variability in EV participation—prosumer engagement may fluctuate due to behavioral factors, travel patterns, or incentive levels. Such variations could lead to temporary supply–demand mismatches if not compensated by predictive scheduling or adaptive incentive adjustments. Addressing these factors in future deployments through redundancy in base station coverage and adaptive prosumer incentive mechanisms will further enhance the robustness of the proposed system.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a smart energy management approach to minimize grid cost and optimize prosumerism. A branch and bound-based MILP solution is proposed for grid cost minimization and to dynamically regulate its supply considering the energy supplied from EVs. Furthermore, the paper has presented a theoretical analysis of the incentive distribution mechanism, upper bounds of demands and supply, and the expected number of demanding and supplying EVs per charging station, leading to the optimized number of charging stations on a given length of road. The proposed solution results in an average of 38.21% reduction in grid supply compared with the supply without optimization and prosumerism. Additionally, the EVs acting as prosumers can reduce 5.3% of grid cost on average, compared with optimized supply from the grid without prosumers. Also, the penalty charge for CO2 emissions proposed in the solution results is less than 50% of the cost as compared to using fossil fuels, thereby encouraging the use of renewable resources. The communication and computation complexity of the proposed solution is found to be less than the non-cooperative energy trading approaches among EVs. The increasing complexity due to an increasing number of EVs can be managed by hourly execution of the algorithm in a pre-defined area. Future research directions include time-based traffic predictions for enhanced optimization, investigation of optimized locations and number of wind and PV systems, and exploring detailed usage and challenges of V2G technology associated with sharing supply from prosumers of one region or network to another.

Beyond the quantitative outcomes, the proposed framework also holds significant implications for policy implementation and multi-stakeholder collaboration. The feasibility of deploying the model in real-world energy systems depends on coordinated participation among regulatory bodies, grid operators, EV manufacturers, and consumers. Policy frameworks can play a central role by establishing transparent incentive mechanisms, standardizing bidirectional communication protocols, and introducing carbon-penalty schemes that promote consistent prosumer engagement. Practical implementation could begin through pilot-scale projects integrated with existing smart grid infrastructures, enabling iterative validation before nationwide adoption. Moreover, stakeholder engagement and public awareness initiatives are crucial to ensure user trust, equitable participation, and long-term sustainability of prosumer-driven energy ecosystems aligned with net-zero targets.

This paper not only presents the technical benefits of optimized prosumerism, such as reduction in grid burden and cost, but also highlights associated steps necessary for its effective implementation, such as encouraging cooperation, discouraging selfish behavior and setting up an optimum number of charging stations. Although bidirectional V2G is a recommended solution to provide reliable supply during peak demand hours, the proposed solution provides a complete framework for net zero by inclusion of distributed renewable resources and also suggesting prosumerism as an integrated approach, independent of time, to make the most of available resources and infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and M.N.; Methodology, F.A.; Validation, F.A. and N.J.; Formal analysis, F.A.; Investigation, F.A.; Resources, F.A. and M.N.; Data curation, F.A.; Writing—original draft, F.A.; Writing—review and editing, F.A. and N.J.; Supervision, M.N.; Project administration, M.N.; Funding acquisition, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to this publication is funded by the UKRI/EPSRC Network Plus “A Green Connected and Prosperous Britain” with grant number EP/W034204/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this article is openly available and can be accessed from the following source: https://www.renewables.ninja/, accessed on 1 September 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

Let q be the probability that or more players choose , irrespective of the knowledge of player i. Let be the probability that player i maliciously finds out that another player will choose . The probability that player i knows that at least players will choose is . The expected payoff sum is

which reduces to . We want to prevent selfishness, where is the payoff of a player taking action without knowledge of other players’ actions, i.e., . If , then , or , i.e., . According to Propostion 1, which means .

References

- Ayaz, F.; Nekovee, M. Towards Net-Zero Goal through Altruistic Prosumer based Energy Trading among Connected Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jadidbonab, M.; Abdeltawab, H.; Mohamed, A.-R.I. An Optimal Routing Framework for an Integrated Urban Power–Gas–Traffic Network. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 5, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasla, N.; Al-Ammari, M.; Abdallah, M.; Younis, M. Blockchain Based Trading Platform for Electric Vehicle Charging in Smart Cities. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 1, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S. A Comprehensive Review on Issues, Investigations, Control and Protection Trends, Technical Challenges and Future Directions for Microgrid Technology. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2020, 30, e12446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeimozafar, M.; Eskandari, M.; Savkin, A.V. A Self-Optimizing Scheduling Model for Large-Scale EV Fleets in Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 8177–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Ming, Z.; Wen, T. Scheduling Strategy of Electric Vehicle Charging Considering Different Requirements of Grid and Users. Energy 2021, 232, 121118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freymiller, K.; Qin, J.; Qian, S. Joint Optimization of Transportation-Energy Systems Through Electric Vehicle Charging Pricing in the Morning Commute. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 6, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y. Intelligent Regulation on Demand Response for Electric Vehicle Charging: A Dynamic Game Method. IEEE Access 2020, 20, 66105–66115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucevic, D.; Englberger, S.; Sharma, A.; Trivedi, A.; Tepe, B.; Schachler, B.; Hesse, H.; Srinivasan, D.; Jossen, A. Reducing Grid Peak Load through the Coordinated Control of Battery Energy Storage Systems Located at Electric Vehicle Charging Parks. Appl. Energy 2021, 295, 116936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Tanwar, S.; Bodkhe, U.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, N. EVBlocks: A Blockchain-Based Secure Energy Trading Scheme for Electric Vehicles underlying 5G-V2X Ecosystems. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 127, 1943–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Feng, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, G. Blockchain-Enabled Two-Way Auction Mechanism for Electricity Trading in Internet of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 8105–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, F.; Nekovee, M.; Sheng, Z.; Saeed, N. Digital Twin based Reinforcement Learning for Energy Exchange among Electric Vehicles and Base Stations in a Disaster-affected Region. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025; Accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Visakh, A.; Manickavasagam Parvathy, S. Energy-Cost Minimization with Dynamic Smart Charging of Electric Vehicles and the Analysis of Its Impact on Distribution-System Operation. Electr. Eng. 2022, 104, 2805–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, D.M.; Frey, G. Modeling and Optimizing Energy Supply and Demand in Home Area Power Network (HAPN). IEEE Access 2019, 8, 2052–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, F.; Nekovee, M.; Ibraheem, A.F. Telecom-to-Grid: Supercharging 6G’s Contribution for Reliable Net-Zero. IEEE Reliab. Mag. 2025, 2, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, F.; Nekovee, M. Quantum Optimization for Bidirectional Telecom Energy Exchange and Vehicular Edge Computing in Green 6G Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, Computing Technologies for Smart Grids, Oslo, Norway, 29 September–2 October 2024; pp. 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Liu, X.; Tang, D. Game-Theoretic Applications for Decision-Making Behavior on the Energy Demand Side: A Systematic Review. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Park, S.-W.; Son, S.-Y. Gamification-Based Vehicle-to-Grid Service for Demand Response: A Pilot Project in Jeju Island. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30209–30219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. How Much Energy Do Bounded Rational Participants Share in Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G)? In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe, Grenoble, France, 23–26 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Wang, M.; Zhang, N.; Shen, X. Energy and Information Management of Electric Vehicular Network: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 967–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Lamantia, M.; Yang, K.; Che, P.; Wang, J. Electric Vehicle Velocity and Energy Consumption Predictions Using Transformer and Markov-Chain Monte Carlo. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3836–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, S.M.; Jeske, D.R. Some Suggestions for Teaching about Normal Approximations to Poisson and Binomial Distribution Functions. Am. Stat. 2009, 63, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdieck, R.; Wittmann-Hohlbein, M.; Pistikopoulos, E.N. A Branch and Bound Method for the Solution of Multiparametric Mixed Integer Linear Programming Problems. J. Glob. Optim. 2014, 59, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewables. Ninja. Available online: https://www.renewables.ninja/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Cheng, S.; Gao, P.-F. Optimal Allocation of Charging Stations for Electric Vehicles in the Distribution System. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Green Building and Smart Grid, Yilan, Taiwan, 22–25 April 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased Boosting with Categorical Features. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.