Abstract

As ports evolve to meet sustainability targets, seamless coordination between road and rail operations becomes fundamental to success. This study addresses the Train Loading Planning Problem (TLPP) which focuses on assigning outbound containers to train wagons under slot, weight, and pattern constraints aiming to examine its broader systemic implications. A compact mixed-integer programming formulation is developed and enhanced through a column-generation approach that efficiently prices feasible wagon plans. The optimization module is embedded within a discrete-event simulation of terminal processes including yard handling, gate operations, and train timetables. The study tests a TLPP-based rail planning algorithm within a DES of terminal and hinterland operations to quantify the impact under realistic variability. Using operational data from the Port of Valencia, realistic planning scenarios are evaluated across varying demand mixes and train frequencies. Results indicate that integrating rail capacity with optimized wagon loading reduces set-up time by 20%, delivery lead time by 54%, container dwell time by 80%, and greenhouse gas emissions by 54% compared with a trucking forwarding baseline, while maintaining throughput and alleviating congestion at terminal gates and yards. From a computational perspective, the column-generation approach achieves improved runtimes to the compact MIP and scales linearly to the number of variables. The proposed framework delivers ready to use load plans and practical insights for the deployment of additional rail capacity, supporting sustainable logistics in port environments.

1. Introduction

Maritime transportation plays a crucial role in global supply chains, with over 90% of international freight transport involving the shipping industry [1]. At the global level, according to UNCTAD, maritime trade volumes reached 12.3 billion tons in 2023, marking a 2.4% growth compared to 2022 [2]. This dominance is particularly evident in Europe, where the total weight of goods transported to and from main EU ports via short sea shipping reached 1.6 billion tons in 2023, with projections indicating steady growth [3]. Despite their economic importance, ports represent a significant environmental challenge, contributing approximately 3% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [4] and roughly 11% of transport-sector CO2 emissions [5]. The concentration of emissions is particularly pronounced within port areas, where shipping activities account for 5% of total shipping GHG emissions yet represent approximately 50% of all port-related emissions [6]. This environmental impact is exemplified by major port-city complexes such as Rotterdam, where annual CO2 emissions can reach 13.7 million tons [7], representing 2% of the Netherlands’ total freight transport CO2 emissions [8].

Concurrently, mounting global and regional policy pressures are driving the maritime transport sector toward decarbonization. Key initiatives include the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) revised GHG Strategy, which mandates net-zero shipping emissions by approximately 2050, and the European Union’s Green Deal, targeting a 55% emission reduction by 2030 to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Furthermore, the 2011 EU White Paper on Transport established modal shift targets to transfer 30% of freight journeys over 300 km from road to rail or waterways by 2030, increasing to 50% by 2050, as part of a comprehensive strategy for sustainable logistics [9]. These policy frameworks recognize that ports often located adjacent to densely populated urban areas must substantially reduce their carbon and pollution footprints to align with climate objectives and protect local air quality. This imperative creates additional pressure on both seaports and inland ports, which already face the ongoing challenge of handling increasing cargo volumes while maintaining operational speed and efficiency [10].

Port operations from ship berth to inland delivery present substantial opportunities to reduce delays, energy consumption, and GHG emissions through optimization and technology. Inefficiencies in berth scheduling, yard storage, and intermodal transfers cause vessel idling and truck queuing, increasing fuel use and emissions. Approximately, vessels spend 4–6% of their yearly operations, equivalent to 15–22 days/year, waiting at anchor [11] leading to unnecessary fuel consumption and emissions. Improved vessel scheduling can reduce ships’ port-area emissions by 8–12% [12], while automated mooring systems save approximately 33 tons of CO2 annually per installation [4]. Digitizing cargo flows and optimizing yard equipment yields significant pollution reductions, with idling time cuts delivering fuel savings of 7–19% depending on efficiency gains [13]. Integrated operational measures can decrease peak CO2 and NOx emissions by over 30%, while strategic compact terminal designs could cut intra-terminal CO2 emissions up to 70% by minimizing transport distances [14]. Equipment electrification and renewable energy integration prove effective. Valencia Port reduced carbon emissions by 30% between 2008 and 2019 despite a 42% growth in cargo through combined electrification, renewable energy, and operational improvements [15].

Enhanced port–hinterland connectivity is generally associated with rapid and efficient transfer of cargo [2]. Optimizing port–hinterland connections is fundamental to achieving landside efficiencies and modal shift targets, particularly through rail integration. Rail freight emits 3–4 times less CO2 per ton-km than road transport, accounting for under 1% of EU transport GHG emissions [16]. European ports like Rotterdam and Valencia demonstrate success through on-dock rail terminals and inland connections, with intermodal expansion reducing heavy truck traffic by 20–30% and associated emissions. Maximizing benefits requires efficient port–rail interfaces including automated cranes and digital coordination platforms to prevent bottlenecks and ensure rail integration simultaneously enhances throughput and sustainability [9,17].

Central to creating this efficient port–rail interface is the complex task of planning how containers are loaded onto train wagons. This challenge, known as the Train Loading Planning Problem (TLPP), involves strategically assigning containers to maximize the capacity and value of the train while adhering to strict weight, balance, and safety constraints. As a critical step in the intermodal chain, the TLPP has been the subject of extensive academic research focused on developing sophisticated optimization models to solve this intricate puzzle [10]. However, while the optimization of the TLPP itself has seen significant progress, a comprehensive review of this research reveals three critical limitations that prevent a holistic evaluation of the true benefits of rail integration [18]. First, optimization models are typically evaluated in isolation without considering their interaction with broader terminal operations such as yard handling, gate processing and train scheduling, a narrow focus that overlooks how loading decisions affect system-wide performance metrics including throughput, dwell times, and congestion patterns. Second, sustainability assessments remain superficial, often limited to theoretical container counts without quantifying actual environmental impacts such as truck-kilometers saved, CO2 emission reductions, or air quality improvements. Third, operational realism is insufficient in existing studies, which typically assume deterministic conditions and ignore the stochastic nature of port operations, a simplification that limits the practical applicability of proposed solutions and their performance under real-world uncertainty.

This study addresses these gaps by developing an integrated optimization and simulation framework that embeds a strengthened train loading formulation within realistic terminal operations. Rather than focusing on isolated research questions, the paper is structured around three key contributions that jointly advance the existing literature in TLPP modeling, solution approaches, and system-level assessment:

- C1: We propose a new mixed-integer formulation of the Train Loading Planning Problem that explicitly models per-slot weight limits and admissible container combinations at the wagon-pattern level. The model supports realistic loading patterns, and their associated weight configurations, by merging size-forcing rules and slot weight caps in a unified framework. The pattern and weight catalog is derived directly from the detailed loading requirements and safety rules provided by the Port of Valencia. To the best of our knowledge, this configuration of slot-level weight constraints and pattern-based container layouts has not been studied in the TLPP literature. At the same time, the formulation remains sufficiently generic so that other ports can apply it by inserting their own wagon types and pattern rules, enabling straightforward replication and comparative analysis across different terminals.

- C2: We design a column-generation-inspired solution approach that combines heuristic plan generation with a restricted master problem over a pool of wagon plans. Instead of full pricing, fast-greedy, sampled-greedy, and local-search operators generate diverse, high-quality loading plans per wagon, which are then selected through a compact 0–1 master problem. This hybrid approach preserves the Dantzig–Wolfe “one-plan-per-wagon” structure and achieves near-MIP solution quality, while substantially accelerating computational times and maintaining scalability across different instance sizes and wagon configurations.

- C3: We embed the proposed TLPP formulation and plan-pool solution method into a discrete-event AnyLogic simulation of the Port of Valencia, covering vessel arrivals, yard handling, gate operations, and train/truck dispatching. This approach is used to evaluate the asymptotic impact of optimized train loading on port-wide sustainability and performance indicators, including truck-kilometers, GHG emissions, container dwell times, and gate congestion, under varying demand scenarios and rail capacity configurations. In this way, the TLPP is assessed not only as an isolated optimization problem but as a sustainability enabler within the broader port–hinterland logistics system.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review of train loading optimization, port sustainability initiatives, and simulation-optimization approaches in maritime logistics. Section 3 presents our methodological framework, detailing the mixed-integer programming formulation for the TLPP, the column-generation enhancement, and the discrete-event simulation model of terminal operations. Section 4 describes the case study set-up at the Port of Valencia, including data collection, scenario design, and performance metrics. In addition, Section 4 presents and analyzes the computational performance of the TLPP model in terms of execution time and benchmark analysis compared to the exact MIP model. Finally, Section 5 concludes with a summary of key contributions, limitations of the current study, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The Train Loading Planning Problem (TLPP) is a critical operational challenge in optimizing port–rail integration, focused on assigning outbound containers to a train’s wagons to maximize utility while adhering to numerous constraints. At its core, the problem is a highly complex variant of the 3D Bin Packing Problem, where “items” (containers) must be optimally placed into “bins” (the wagons of the train). This classification is important because bin packing problems are NP-hard, meaning that finding the single best solution becomes computationally intractable as the number of containers and wagons grows. The TLPP is further complicated by multiple layers of real-world operational rules that go beyond simple spatial fitting. These include strict adherence to individual wagon slot and overall weight capacities, managing a mix of container sizes and weights, and ensuring a balanced weight distribution across the train for safety [10,19,20]. The primary objectives are to maximize the number of loaded containers and minimize unproductive container re-handling in the yard.

Early research approached the TLPP using integer programming (IP) with significant simplifications, such as considering only one container type and ignoring wagon weight limits [21]. Methodologies quickly evolved to incorporate greater realism. Bruns and Knust (2012) [22] introduced three distinct ILP formulations that maximized train utilization by considering multiple container types, various wagon configurations, and detailed weight and stability constraints. Other models introduced objectives like fuel efficiency [23] and accounted for operational uncertainty through robust optimization techniques [24].

In parallel with TLPP advances, the Physical Internet (PI) has emerged in port and intermodal logistics as a paradigm for modular, open, and networked cargo exchange (using standardized π-containers, interoperable nodes and routings that enable synchromodal, real-time switching across modes). Positioning a TLPP optimization within a PI-oriented corridor invites loading patterns that are not only wagon-feasible but also routing-aware and mode-switch-ready, so that yard moves, train paths, and hinterland services co-evolve under shared protocols; this aligns with the roadmap vision of ALICE for scalable, sustainable port-centric intermodal hubs and corridors, and with operational policies that induce low-carbon modal shifts without sacrificing service quality [25]. This framing opens a concrete avenue for future research: designing TLPP matheuristics whose objectives and constraints are explicitly coupled to PI primitives (container modularity, hub openness, and service composability) and synchromodal control rules [26,27,28].

A pivotal shift occurred when research began tailoring models specifically for seaport terminal environments. Ambrosino et al. (2011) [29] were pioneers in this area, developing mathematical formulations and heuristics with a biobjective: maximizing train throughput while minimizing unproductive yard moves or rehandles. Their work highlighted that in space-constrained ports, the time spent on rehandles is a crucial component of the total operation time, especially under the common assumption of a sequential loading process [29]. Subsequent studies by this group further explored the trade-offs between packing density and yard logistics by comparing different loading sequences and solution methods on real port data [20,30].

Given the TLPP’s computational complexity, heuristic and metaheuristic algorithms are widely used to find high-quality solutions in a practical timeframe. Approaches such as Lagrangian relaxation have been employed to tackle multi-train planning and minimize container travel distance from the yard to the train [31]. More recent studies have successfully applied advanced metaheuristics like adaptive large neighborhood search (ALNS) to efficiently schedule automated cranes for train loading under various operational modes [17]. Another study by Ambrosino et al. (2021) [32] introduced a matheuristic approach that combines randomized heuristic techniques with mixed-integer programming to test the effectiveness of each method in finding good solutions in an acceptable computation time.

Simultaneously, researchers have refined exact optimization methods to make them more tractable for real-world applications. A key innovation is the use of column generation and branch-and-price, where instead of assigning individual containers, the algorithm generates feasible loading patterns for each wagon. This approach reduces problem size and symmetry, enabling efficient solutions for complex scenarios [33]. Models have also become more sophisticated in capturing physical constraints; for instance, Ambrosino and Caballini (2019) [10] proposed ILP models that embed detailed weight distribution principles to ensure axle loads are not exceeded, demonstrating their effectiveness on real-world data from Italian terminals. This focus on computational efficiency has yielded dramatic results. Ng and Lin (2022) [34], by developing a tailored three-stage algorithm for U.S. double-stack trains, reduced solution times from over two hours to mere seconds, making real-time, on-the-fly optimization feasible.

To summarize the evolution and scope of research on the TLPP, Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the reviewed studies. The table categorizes these works based on three key dimensions: the train and container characteristics considered (e.g., weight limits, container types), the primary optimization objectives (e.g., maximizing loaded containers, minimizing rehandles), and the solution methodologies employed (e.g., integer programming, heuristics). This synthesis highlights a clear progression from early, simplified models toward more comprehensive formulations that incorporate a wide range of operational constraints such as wagon-specific weight limits, diverse container types and container priority. Furthermore, it illustrates the growing emphasis on objectives directly relevant to terminal operations, such as minimizing unproductive moves and the corresponding shift toward heuristic and metaheuristic methods to achieve computational efficiency for real-world applications.

Table 1.

TLPP approaches comparison.

3. Problem Description and Methods

3.1. System Description and Simulation Environment

The generalized problem studies modal swift strategies at the Port of Valencia that aim to evaluate rail forwarding as a complement to trucking for outbound containers. Train integration in the port’s terminal operations is crucial for transporting cargo to destinate warehouses and raises concerns related to the port’s operational performance and sustainability.

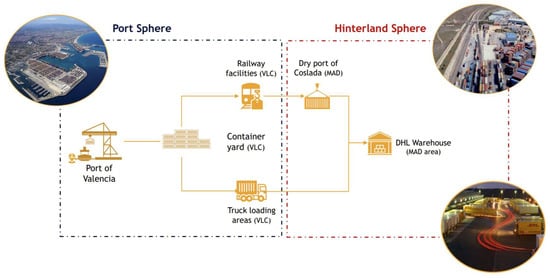

The idea behind rail integration is to use two types of routes in parallel to deliver containers to customers. The first type of multimodal route refers to rail transport from port to dry port followed by truck delivery to a warehouse. The second option refers to direct delivery only by truck from a port to a warehouse Figure 1. The Valencia–Madrid corridor corresponds to approximately 365 km by road and about 420 km by rail.

Figure 1.

System overview of the container flow from vessel arrival at the Port of Valencia to the final destination warehouse in Madrid.

To evaluate this integration in the port’s terminal operations, we decided to conscript a custom simulation model to fully understand the impact of this integration by providing related metrics and KPIs. Our holistic approach was to develop an end-to-end simulation model to assemble each individual process of the Port of Valencia. The whole process includes complete container transport from vessel arrival at Port of Valencia to the delivery to a specific warehouse.

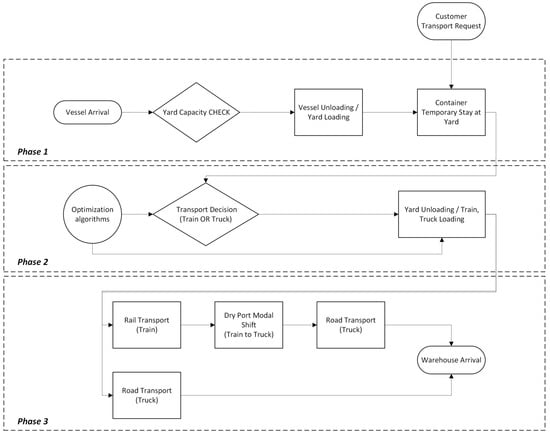

Specifically, the simulation model flowchart design, divided in three smaller phases, provides a virtual replica of port operations (Figure 2). Phase 1 includes vessel arrivals, containers unloading, and yard storage. Phase 2 includes transport decision, yard handling, and train/truck loading. The embedded connection of the simulation model with optimization algorithms (integration of “Transport Decision” and “TLPP” algorithms) provides efficiency in the train/truck loading process. First, the optimization algorithm decides the “transport mode” based on train and truck fleet capacities. Second, the algorithm faces the TLPP and allocates containers to wagon slots based on container parameters (size, weight, etc.) and wagon constraints. Within the integrated framework, the TLPP optimization module is invoked once per simulated operational day at the beginning of the day, consistent with day-ahead planning practices in real terminals. At each request, the AnyLogic model extracts the set of rail-eligible containers (including size type, weight, destination, and availability time) and assembles them into an input instance that follows exactly the same data structure as the TLPP formulation described in Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5. The optimization module returns a detailed loading plan, specifying the assignment of containers to wagons and slots, which is then executed as a sequence of loading and departure events in the simulation. Data exchange and parameter updating thus occur only at these daily decision points, with no additional sub-daily synchronization between simulation and optimization. Phase 3 includes the transport of containers to the destinated warehouse. For the multimodal route (train + truck), a modal shift takes place in a specific hinterland (dry) port. For each individual route, measurement of emissions provide, according to parameters such as vehicle type, emissions factors and cargo weight. emissions are computed by multiplying the truck and train kilometers generated by the simulation with mode-specific emission factors provided by the Port of Valencia. These factors embed the port’s internal assumptions on fleet composition and loading, so the reported environmental results reflect corridor level performance for the Valencia–Madrid services under the simulated conditions. After the simulation experiments, based on objective and measurable criteria, we provide some useful KPI values (Table 2). These KPI values directly support both operational and sustainable perspectives. The quantitative calculation is provided directly from the simulation model developed on AnyLogic Software (https://www.anylogic.com/) by the relevant statistics extraction modules. Table 2 provides in the KPI description the definition of what each KPI refers to.

Figure 2.

Simulation process diagram.

Table 2.

Simulation experiments collected KPIs.

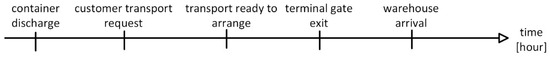

The time-based KPIs (set-up time, delivery lead time, and container dwell time) were calculated using a consistent procedure within the discrete-event simulation model. In AnyLogic simulation software, time measurements were collected through pairs of TimeMeasureStart and TimeMeasureEnd blocks, which record the time each agent spends between two defined points in the process flow (Figure 3). In this study, each container is treated as an individual agent.

Figure 3.

Events nodes that KPIs estimations use over simulation time.

For each KPI, the elapsed time can be described through a pair of time t variables according to the next formula. For each agent i, the elapsed time is given by

where denotes the total number of containers processed in a single simulation experiment. After executing a total of experiments (samples), and considering variable as the time the transport request was received from the customer and as the time when the transport is ready to be carried out (just after truck/train loading finish), the overall mean Set-up time KPI value is obtained as

Similarly, considering variable as the actual time that each container reaches the warehouse, the overall mean Delivery lead time KPI is obtained as

Similarly, considering as the moment of container discharge from the vessel and as the time that the loaded truck/train exits the terminals exit, the overall mean Container dwell time KPI is obtained as

This calculation approach for the three time-related KPIs ensures that the reported results represent the mean performance across all simulated operational days.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were calculated separately for each transport segment and then aggregated per transport chain. For each route, emissions were computed using the standard formulation:

The total GHG emissions were aggregated across all containers per simulation experiment and then averaged over 30 simulation experiment samples. The reported KPI percentage of change is shown in Table 3. Selected KPIs collected from the simulation experiments compare the average (per route) GHG emissions between the traditional direct delivery route and the proposed multimodal (rail + truck) route.

Table 3.

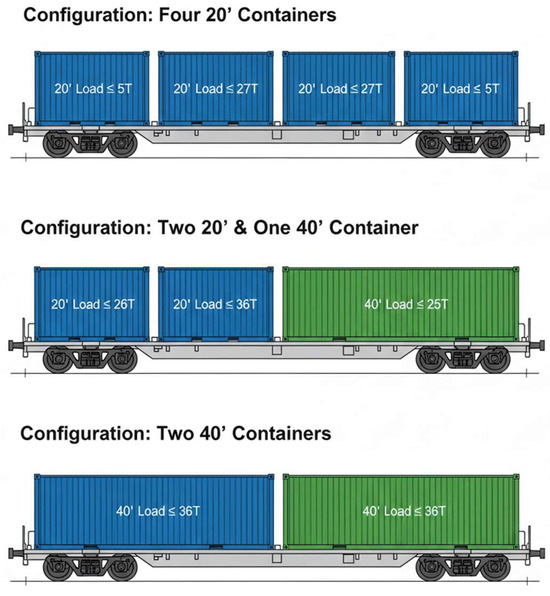

Selected KPIs collected from the simulation experiments.

3.2. Train Loading Planning Problem Description

In this section, we present a deterministic Train Loading Model that assigns containers with given attributes to train wagons so as to maximize the number of containers forwarded by rail during a planning period. The model captures constraints at physical limitation level (per-position weight limits and size admissibility) and pattern-specific rules (e.g., mandatory (20, 20, 40) layouts). We then describe a decomposition that reformulates the model into a set-partitioning master and solves it by column generation. We consider a fixed train composition with a set of wagons. Each wagon admits one of a finite set of patterns (slot layouts). A pattern exposes discrete positions (slots), each with a weight limit and, optionally, a set of admissible sizes. Containers are indivisible items characterized by size (e.g., 20/40) and weight. The valid loading patterns provided by the port authority are fixed and limited to {(20, 20, 20, 20), (20, 20, 40), (40, 40)}, with eight permissible weight combinations for the first pattern, four for the second, and one for the third. The loading patterns shown in Figure 4 represent the admissible slot combinations provided by the Port of Valencia’s engineering team for the Valencia–Madrid service. These patterns reflect the operational rules used in practice and form the constraints that the TLPP optimization must satisfy, rather than a physical model of a specific wagon type.

Figure 4.

Wagon configuration patterns.

To support the model developed, let denote the set of containers and the set of wagons. For each wagon, let , let be the set of acceptable loading patterns for each with , and let be the set of positions (slots) in that pattern . Let be the size set and the containers of size . For each option and slot , define a required size map if that slot is forced to a size, and let be the set of forced slots. Data include container weights , slot limits constraints , and eligibility flags (size/handling/time feasibility).

For decision variables, let equal 1 if container occupies position of pattern on wagon ; let indicate that pattern is selected on wagon ; and let denote whether container is loaded by rail (served). Equivalently, an unserved indicator can be used in place of .

The objective (O-1) counts how many containers are forwarded by rail, aligning directly with the operational goal to maximize the number of containers forwarded with the most sustainable alternative. Constraint (1) selects exactly one option for each wagon. Constraint (2) allows at most one container per slot and activates a slot only if its option is chosen while (3) ensures each container appears in at most one slot overall (and defines ). The constraint (4) enforces the per-slot cap from the tables. (5) screens infeasible placements. (6) is the size-forcing rule: for every wagon, pattern, slot, and triple, exactly one container of the required size occupies that slot, if the option is chosen together with (2) it excludes wrong-size placements.

3.3. Solution Approaches and Complexity

The train-loading problem couples a per-wagon, slot-level packing decision respecting size-forcing and per-slot weight limits with a global exclusivity constraint that each container can be used at most once across wagons. Modeling each wagon option as a pattern and each feasible slot assignment as a plan yields a maximum set-packing structure over an exponential plan set, so the problem is NP-hard (even with fixed option catalogs) and quickly becomes not tractable for exact strategies. We introduce a baseline greedy myopic approach of wagon-by-wagon heuristic that assigns containers to wagons sequentially on the residual pool of containers. This approach is very fast and easy to implement, but it is order-dependent, performs no backtracking, and fails to price the opportunity cost of scarce containers (e.g., a 40′ that fits only tight caps), so it can block better global combinations. An exact compact MIP activates one option per wagon and uses binary slot variables with size-forcing and weight constraints; it delivers probably optimal solutions (or optimality-gap certificates) on small/medium instances, but its size scales with the number of eligible containers–slot pairs (and patterns), leading to many binaries and potentially large branch-and-bound trees. A column-generation (Dantzig–Wolfe) formulation mitigates this by treating each feasible wagon plan as a column so that the master problem selects one plan per wagon and enforces container uniqueness, while pricing subproblems (one per wagon) generate improving plans by solving a small assignment/MIP that already embeds all slot physics. This yields strong LP bounds, generates only useful plans, scales well to larger instances, and can be made exact with branch-and-price or by solving a small integer master over the generated columns, retaining clear, implementable load plans.

To fully utilize trains’ loading capacity we update the objective accordingly so that it maximizes the number of containers loaded on the train while it also maximizes slot-level weight utilization. In practice, we implement this via a single scalar surrogate with . To streamline the model, we eliminate explicit eligibility constraints: containers are time-filtered before optimization (arrival departure lead time) and only those in the time-feasible set enter the model. Size feasibility is enforced structurally by the slot–size equalities (6), and weight feasibility by per-slot limits (4). No other eligibility predicates are modeled as it is considered redundant.

3.4. The Greedy Myopic Wagon-by-Wagon Baseline Method

As a fast benchmark we solve wagons sequentially so, for a fixed order of wagons, we choose the best feasible pattern for the current wagon and fill all of its slots. After each assignment we remove those containers from the pool and proceed to the next wagon, similar to [10,20]. This produces a feasible, often high-quality, solution quickly, but it is order-dependent, lacks backtracking, and does not account for the opportunity cost of allocating scarce containers that may be critical for later wagons. Therefore, the decision variable while the , thus the size of the problem decreases significantly. The challenge is to see how this model, and under which conditions, performs better than the original. In any case, this can serve as a good baseline for other semi-exact methods.

3.5. Column-Generation Approach

This section describes the columns-generation approach [35] that aims to speed up the exact MIP solution while it also captures the full problem rather that the greedy sub-optimal. We consider a plan for wagon selects one option and assigns exactly one container to each , satisfying (1)–(3) locally. Let indicate whether is used in . We also define and . The restricted master problem (RPM) chooses one plan per wagon:

with . Let and be duals of (8) and (9).

The reduced cost that serves as a criterion for insertion of a new plan of for the wagon is

For a fixed wagon , pricing generates a feasible plan by selecting one option and assigning time-feasible, correct-size containers to each forced slot under the slot weight caps . The result is a feasible loading . Because each option has only a few forced slots, this per-wagon problem is a tiny assignment/MIP, letting us return one or several best plans per call and rapidly enrich the restricted master.

with binaries defined only for correct-size pairs. Especially, takes the value 1 if container selected elsewhere is 0. Similarly to the original problem, indicates whether container assigned under pattern in slot . If (11), we append the resulting plan to the master. When no wagon yields positive reduced cost, the RMP is optimal for the full master LP; an implementable solution is obtained by solving a small integer master over the generated columns ().

After time-filtering and building the option catalog , we seed each wagon with one feasible plan obtained by pricing at to guarantee master feasibility. We then iterate solve the restricted master to obtain and run pricing independently for every to generate one or more improving plans, append any plan with positive reduced cost, and repeat until no improvements arise. Each generated plan is stored as an immutable record holding , , the explicit slot map , its incidence vector , and . Master variables are created in the same index order as the per-wagon plan lists, so reconstruction is direct: once the final integer master selects one column per wagon, we read off for , set from the stored slot map, and set for all containers used by the chosen columns. This “MIP-and-store” workflow keeps local wagon physics in the pricing problems, keeps the master compact, and produces auditable, slot-by-slot load plans aligned with the notation.

3.6. The Dantzig–Wolfe Inspired Plan-Pool Heuristic

The column-generation approach is tractable when the compact model explodes in size (e.g., millions of slot-level variables) so the problem is re-expressed with a few high-level plans found on demand. In our train-loading setting, the compact MIP is already modest and solver-friendly (≈4 slots per wagon, 10–15 wagons per assignment). The optimization loop then becomes pure overhead: solve an LP master, run many pricing problems (per wagon/option, sometimes K-best), and re-optimize a degenerate master that keeps adding near-duplicate columns. Consequently, we have one well-engineered branch-and-cut on the compact model that often outpaces thousands of tiny solves plus repeated re-solves similar to [36]. CG remains useful here only when the option catalog or side-constraints balloon (e.g., long trains, many special patterns, etc.), so pricing is much cheaper than handling all variables upfront.

We keep the Dantzig–Wolfe master but replace pricing with fast generation. For each wagon , a plan chooses an option and assigns slots to containers where its value is . We build a pool on three stages:

- (1)

- a global greedy baseline assigns wagons one-by-one while removing used containers

- (2)

- per wagon, sampled greedy generates ≈ alternatives from a % sample of containers

- (3)

- fast LNS perturbs existing plans by destroying 1–2 slots and greedy repair to add ≈+ synthetic plans. Given pools , we solve a small 0–1 master once per iteration:

We then eliminate SL% of the weakest plans (protecting the current master-optimal and the baseline), refresh with new sampled-greedy/LNS plans, and iterate times.

This metaheuristic preserves DW’s “one-plan-per-wagon + packing” structure but deletes the slowest piece that is pricing. It ensures an always feasible baseline, along with fast and scalable sampling combined with LNS to reduce degeneracy. Complexity is roughly linear in the number of pooled plans, which we collect per wagon, so runtime is predictable. The most suitable way is to utilize when the compact MIP is solvable, but for better utilization than greedy with tight time limits, switch to full CG only when option complexity explodes and true pricing becomes cheaper than enumerating rich plan pools.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the use case derived from simulation experiments, which assess process improvements enabled by the introduction of a train-based alternative, as well as the computational performance of the TLPP under multiple instance sizes. The objective is to propose implementation guidelines according to the size and complexity of the problem.

4.1. Simulation Experiments Set Up and Results Discussion

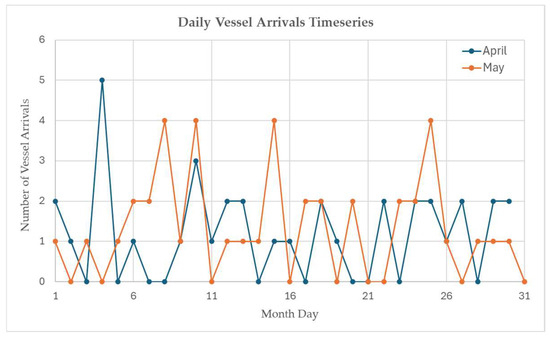

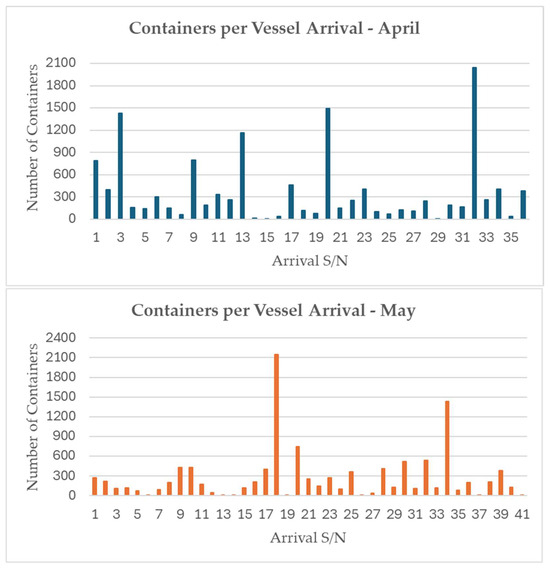

The dataset employed in the simulation consists of historical vessel arrivals (Figure 4), TEU drop-offs per vessel (Figure 5 and Figure 6), train schedules, and truck and train cost and time parameters. The simulation incorporates certain simplifications and blind spots, particularly with respect to yard capacity, as it excludes demand generated by other port operators and considers only the reference company. Following Valencia Port guidance that available yard space is almost always sufficient, the yard capacity is therefore assumed to be unlimited. This assumption implies that congestion effects inside the yard are not represented and that the reported dwell times should be interpreted as lower bound estimates. Detailed sensitivity analysis under explicit yard capacity constraints was not conducted due to lack of reliable occupancy data, although introducing rail as an additional forwarding mode is expected to reduce yard pressure rather than create new bottlenecks.

Figure 5.

Daily vessel arrivals for the Port of Valencia in April and May 2025.

Figure 6.

Distribution of containers handled per vessel arrival during April 2025 (above) and May 2025 (below).

Movements of containers to and from the yard are approximated using probability distributions provided by the port rather than empirical data samples fitted directly to statistical distributions. Distribution fitting techniques were applied exclusively to vessel arrival processes and the number of container demand generators. For each container, the dataset included information on weight, size category (20 ft or 40 ft), arrival time, transport request, and contractual lead time, as extracted from the port management system.

The simulation experiments were conducted over a two-month period (April–May 2025). Each scenario is simulated over a finite horizon of 30 operational days. For each scenario, 30 independent replications are run in AnyLogic, with the random number generator configured to use different random seeds across replications while keeping the experiment settings reproducible. The KPIs reported in Table 3 correspond to the mean values over these 30 runs, and standard deviations are used to verify that the results are statistically stable. No separate warm up period is defined, because the 30 day horizon represents a finite planning period and the start-up phase is part of the operational behavior that the study seeks to capture. These experiments were used to generate critical KPIs for the Port of Valencia to support investment assessment and strategic planning. The publicly available KPIs of the case study are summarized in Table 3. These KPIs are mobilized to provide to the Port of Valencia managerial insights, evaluation of results, and strategic improvement guidelines.

The simulation results, benchmarked against baseline values from port data, clearly demonstrate the operational and environmental benefits of incorporating the train option into hinterland transport operations. Set-up time decreased by 20%, indicating smoother and more efficient coordination of resources. Delivery lead time was reduced by 54%, highlighting the capacity of rail services to absorb container flows and accelerate throughput. Container dwell time exhibited the most significant reduction, at 80%, confirming that the additional transport resource alleviates bottlenecks in the yard and expedites cargo turnover. From a sustainability perspective, greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 54%, reflecting the lower per-unit carbon intensity of rail compared to road transport.

4.2. Train Loading Plan Problem Experiments Set-Up and Results Discussion

The computational efficiency of the TLPP was evaluated through controlled experiments. A synthetic dataset was constructed using probability distributions derived from historical vessel arrival data recorded at the Port of Valencia for April and May 2024. For each configuration, 10 independent samples were generated, resulting in a broad set of test cases to evaluate algorithmic performance across computational time and weight distribution efficiency.

The experiments were executed using PuLP, gurobipy and Gurobi 13. All tests were performed on a machine equipped with an Intel(R) Core (TM) i9-14900KF processor and 128 GB of RAM. The performance results provide insights into both the computational scalability and the practical efficiency of the TLPP solution approaches.

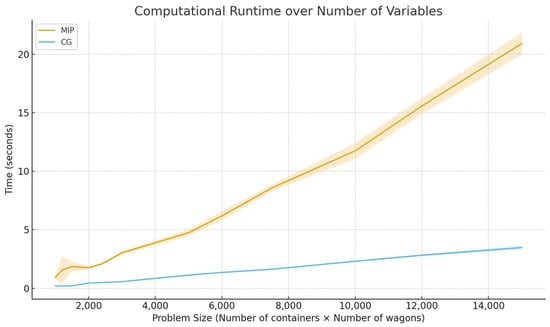

The computational experiments, conducted across instances of 100, 200, 500, and 1000 containers with wagon fleet sizes of 10, 12, and 15 (which is also the maximum of available wagons), reveal important insights into the comparative performance of the exact MIP formulation and the column generation plan-pool heuristic. Table 4 presents the results in terms of solution time, relative weight maximization, and wagon utilization ratios. Notably, the two approaches achieve broadly comparable computational times across all problem sizes, removing runtime as a differentiating factor in this experimental setting.

Table 4.

Computational results of comparing exact MIP formulation solved by GUROBI solver compared to Dantzig–Wolfe column generation plan-pool heuristic. Time measured in seconds and the total container weight and utilization ration percentages consider exact MIP as baseline. .

The updated computational results reported in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 7 demonstrate a consistent and significant advantage of the proposed column generation (CG) plan-pool heuristic method over the exact MIP solved with Gurobi at a strict optimality gap of 1 × 10−6. Across all instance sizes, CG achieves solution times that are significantly lower than the MIP benchmark. For instance, while the MIP model requires between 1 and 21 s depending on the number of containers and wagons, the CG approach solves the same instances in approximately 0.2 to 3.5 s. This confirms the strong scalability of the method, with the performance gap widening as the number of variables grows.

Figure 7.

Computational scalability of column generation inspired heuristic across different problem instances compared to exact solution.

In terms of optimality, the gap values relative to the proven MIP optimum remain essentially zero for all medium and large instances. This behavior reflects the structure of the TLPP, where multiple near-optimal train loading configurations exist once the problem becomes sufficiently large as the size of wagons cannot expand linearly to the size of containers. In such cases, the CG mechanism efficiently navigates the solution space and identifies high-quality plans without requiring exhaustive enumeration. The only meaningful deviations appear in the smallest instance with 100 containers and 15 wagons, where the search space is structurally limited and precise methods are required. With relatively few feasible combinations to fill all wagons, the method encounters fewer alternative near-optimal plans, which moderately affects its ability to match the exact optimum with the same precision observed in larger instances. However, such problem sizes can be effectively addressed by exact methods as the size remains moderate.

5. Conclusions

This study examined how optimized train loading can support the wider adoption of rail forwarding in port logistics by developing a new formulation of the train loading problem and evaluating its performance in a realistic operational setting. The work demonstrated that the physical constraints governing wagon loading can be integrated into a structured assignment model without compromising computational tractability. By explicitly modeling slot weight limits, size-forcing, and pattern admissibility, the formulation provides a detailed and adaptable representation of real wagon physics that is not addressed in existing literature.

Computational experiments showed that a purely classical column generation strategy is not scalable for this problem, because generating new plans requires solving many small MIP pricing problems and repeatedly reoptimizing a degenerate master. This process becomes an overhead that grows with instance size. The results also showed that the most effective strategy is to avoid full pricing and instead generate plans through fast heuristics that reflect the structure of the wagon patterns. This approach maintains almost the same solution quality as the exact model while reducing computation times by an order of magnitude. It also scales well when more constraints or richer pattern catalogs are added, which means that the model can easily be extended to other terminals or to more detailed operational rules.

Another important finding concerns the behavior of the model under different container-to-wagon ratios. When the number of containers is low relative to the available wagon slots, there are very few feasible loading combinations. In these instances, the search space is small and modern MIP solvers are able to solve the exact formulation efficiently. The results suggest that exact methods remain the preferred option in this case, while the heuristic plan-pool approach becomes the most effective for medium and large instance sizes where many near optimal assignments exist.

Integrating the optimization model with a discrete event simulation provided quantitative results about the impact of improved train loading on terminal operations in the Valencia case study. Under the modeled demand profile, service schedules and yard capacity assumptions, introducing rail as an additional transport mode produced substantial improvements in both operational efficiency and environmental performance. The simulation showed reductions of 20% in set-up time, 54% in delivery lead time, 80% in container dwell time, and 54% in greenhouse gas emissions relative to the trucking-only baseline. These values should be interpreted as scenario-specific indicators of the potential benefits of TLPP-based rail forwarding on the Valencia–Madrid corridor, rather than general benchmarks for all ports.

Moreover, the plan-pool approach can generate high-quality loading plans in a fraction of the time required by exact methods, it becomes feasible to execute hundreds of experiment runs and evaluate large numbers of operational scenarios. This computational efficiency is essential for revealing process-level gains that only emerge when many days, vessel arrivals, and demand profiles are simulated. It also enables us to capture the cumulative impact of rail adoption on container dwell times, gate congestion, and environmental indicators. The ability to run extensive scenario analyses would not be possible with slower optimization methods, and this confirms that tractable algorithms are a prerequisite for understanding how train loading strategies translate into system performance improvements.

Despite these contributions, the study is subject to limitations that drive directions for future research. First, the models were evaluated under simplified assumptions of unlimited yard capacity and deterministic handling processes. Incorporating stochasticity and competitive yard demand would yield a more realistic assessment. Future extensions should explicitly consider the randomness of handling times and yard service rates to better capture operational uncertainty. Second, while the optimization approaches proved effective, there is scope for developing more advanced algorithmic strategies such as adaptive large neighborhood search or reinforcement learning-based heuristics that could further improve scalability and robustness under real-time conditions. In addition, the influence of competition between carriers and terminal operators was not modeled, although it can significantly affect slot allocation, scheduling priorities, and resource utilization. Finally, the static nature of the present analysis should be extended to a dynamic setting, where decisions adapt to online events such as vessel delays, train rescheduling, and the movement of straddle carriers for container stacking, loading, and unloading as well as truck arrival delays. In the current implementation, this uncertainty is represented only in the discrete event simulation, while the TLPP is solved as a deterministic day ahead planning problem based on the realized container set at each departure decision. Future work should first assess whether propagating this uncertainty into stochastic or robust TLPP variants yields material benefits, compared with extending the scope of the model toward joint planning of train loading, yard stacking, and straddle carrier routing. Embedding the TLPP within a real-time digital twin of port operations represents a promising direction to bridge tactical planning with operational execution; however, more feature-rich and scalable models are required to achieve valuable action plans.

The findings indicate that, for the modeled Valencia–Madrid corridor, integrating rail transport in outbound port operations with advanced optimization and simulation tools can deliver tangible operational and sustainability benefits. Applying this framework to other ports or corridors would require re-calibration of the models and validation under local operational, regulatory, and demand conditions, which defines a clear agenda for further research in dynamic, data-driven, and algorithmically advanced decision-making for sustainable multimodal transport.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.M.; methodology, Z.M.; software, Z.M. and P.G.; validation, Z.M. and D.T.; formal analysis, Z.M.; investigation, D.T. and P.G.; resources, D.T.; data curation, P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.M., D.T. and P.G.; writing—review and editing, Z.M., D.T., P.G. and S.D.; visualization, Z.M. and P.G.; supervision, G.A.; project administration, G.A. and S.D.; funding acquisition, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe innovation action program under Grant Agreement No. 101069731 (Project FOR-FREIGHT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fruth, M.; Teuteberg, F. Digitization in maritime logistics—What is there and what is missing? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1411066. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport: Navigating Maritime Chokepoints; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 3–118. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat, E.C. Key Figures on Europe—2025 Edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-key-figures/w/ks-01-25-003 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Misra, A.; Panchabikesan, K.; Gowrishankar, S.K.; Ayyasamy, E.; Ramalingam, V. GHG emission accounting and mitigation strategies to reduce the carbon footprint in conventional port activities—A case of the Port of Chennai. Carbon Manag. 2017, 8, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Chan, P.; Dequeljoe, M.; Kim, Y.; Barahona, S. CO2 Emissions from Global Shipping: A New Experimental Database; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnes, H.; Styhre, L.; Fridell, E. Reducing GHG emissions from ships in port areas. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielenia, M.; Podolska, A. Carbon footprint generated by individual port websites. The missing idea in the concept of green ports. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1211454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Ballini, F.; Ölçer, A.I. Revisiting port sustainability as a foundation for the implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). J. Shipp. Trade 2021, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaś, A. The Role of Intermodal Transport in the Decarbonization of Seaports. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, XXVII, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, D.; Caballini, C. New solution approaches for the train load planning problem. EURO J. Trans. Log. 2019, 8, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Francis, H. Port Congestion, Waiting Times and Operational Efficiency. Available online: https://www.u-mas.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Port-Congestion-Report-v1.8.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Xia, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y. Joint optimization of ship scheduling and speed reduction: A new strategy considering high transport efficiency and low carbon of ships in port. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 233, 109224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Adland, R.; Prakash, V.; Smith, T. Energy efficiency with the application of Virtual Arrival policy. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 54, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukić, L.; Lai, K.-H. Acute port congestion and emissions exceedances as an impact of COVID-19 outcome: The case of San Pedro Bay ports. J. Shipp. Trade 2022, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Port Technology International. Available online: https://www.porttechnology.org/news/port-of-valencia-cuts-carbon-emissions-by-30-while-managing-trade-boom/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Merk, O. Shipping Emissions in Ports. Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/dp201420.pdf#:~:text=,180%20for%20road (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Oldache, M.; Pervez, A. Research on Train Loading and Unloading Mode and Scheduling Optimization in Automated Container Terminals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Aisha, T.; Audy, J.F.; Ouhimmou, M. Toward an efficient sea-rail intermodal transportation system: A systematic literature review. J. Ship. Trade 2024, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, S.; Morganti, G.; Umang, N.; Crainic, T.G.; Frejinger, E.; Larsen, E. The load planning problem for double-stack intermodal trains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 267, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, D.; Siri, S. Comparison of solution approaches for the train load planning problem in seaport terminals. Transp. Res. Part E 2015, 79, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, P.; Kozan, E. An assignment model for dynamic load planning of intermodal trains. Comput. Oper. Res. 2006, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, F.; Knust, S. Optimized load planning of trains in intermodal transportation. OR Spectr. 2012, 34, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-C.; Barkan, C.P.L.; Önal, H. Optimizing the Aerodynamic Efficiency of Intermodal Freight Trains. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2008, 44, 820–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, F.; Goerigk, M.; Knust, S.; Schöbel, A. Robust load planning of trains in intermodal transportation. OR Spectr. 2014, 36, 631–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballot, É.; Barbarino, S.; van Bree, B.; Liesa, F.; Franklin, J.R.; ’t Hooft, D.; Nettsträter, A.; Paganelli, P.; Tavasszy, L.A. Roadmap to the Physical Internet. Available online: https://www.etp-alice.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Roadmap-to-Physical-Intenet-Executive-Version_Final-web.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Montreuil, B. Toward a Physical Internet: Meeting the global logistics sustainability grand challenge. Logist. Res. 2011, 3, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballot, E.; Montreuil, B.; Zacharia, Z.G. Physical Internet: First results and next challenges. J. Bus. Logist. 2021, 42, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, N.; Gijsbrechts, J.; Boute, R. Synchromodality in the Physical Internet—Dual sourcing and real-time switching between transport modes. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2019, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, D.; Bramardi, A.; Pucciano, M.; Sacone, S.; Siri, S. Modeling and solving the train load planning problem in seaport container terminals. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, Trieste, Italy, 24–27 August 2011; pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino, D.; Caballini, C.; Siri, S. A mathematical model to evaluate different train loading and stacking policies in a container terminal. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2013, 15, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghinolfi, D.; Paolucci, M. A General Purpose Lagrangian Heuristic Applied to the Train Loading Problem. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 108, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, D.; Anghinolfi, D.; Paolucci, M.; Siri, S. An Optimization Approach for the Train Load Planning Problem in Seaport Container Terminals. In Collaborative Logistics and Intermodality; Hernández, J.E., Li, D., Jimenez-Sanchez, J.E., Cedillo-Campos, M.G., Wenping, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Anghinolfi, D.; Caballini, C.; Sacone, S. Optimizing train loading operations in innovative and automated container terminals. In Proceedings of the 19th World Congress, Cape Town, South Africa, 24–29 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.; Lin, D.-Y. Exact algorithms for practical instances of the railcar loading problem at marine container terminals. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 3927268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelsbergh, M.W. A Branch-and-Price Algorithm for the Generalized Assignment Problem. Oper. Res. 1997, 45, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.J.; Rönnberg, E. Integer Programming Column Generation: Accelerating Branch-and-Price Using a Novel Pricing Scheme for Finding High-Quality Solutions in Set Covering, Packing, and Partitioning Problems. Math. Program. Comput. 2023, 15, 509–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).