Abstract

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) aim to improve safety and comfort of road users while contributing to the reduction of traffic congestion, air pollution, fuel consumption, and enabling mobility and accessibility of disabled and older people. As AV technology is rapidly advancing, there is an urgent need to explore how those new mobility services will impact urban transport systems, including the users, the infrastructure, and the design of future urban areas. This paper applies a systematic review to assess the role of AVs in urban areas. It reviews 41 articles published between 2003 and 2023, and uses inductive and deductive coding approaches to identify seven themes and thirty sub-themes within the literature. The seven include: benefits, attitudes, and behaviours and user perception, climate adaptation, climate mitigation, legislation and regulations, sustainability, and infrastructure. Studies related to benefits accounted for 25% of the sample, followed by behaviours and user perception (24%) and sustainability (22%). The least amount of research has been undertaken on the role of AVs to support climate adaptation. Geographically, almost half (#22) of the papers originate within Europe, followed by America (#10) and Asia (#7). There is only limited research originating from the Global South. This systematic review sets the scene for considering how AVs in public transport can be implemented in urban areas by establishing the current state of knowledge on user attitudes, perceptions, and behaviour, the benefits of AVs, the infrastructure and legislation and regulations required for AVs, and the role AVs have in climate mitigation, adaptation, and sustainability.

1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are perceived as the future of transportation in our cities [1]. The intelligent mobility sector is developing within the framework of AV technology, which is expected to have a global market share of £900 billion by 2025 [2]. Currently, approximately 1.3 million people are killed in traffic accidents annually [3]. Human error accounts for more than 90% of traffic accidents; the decision makers believe that AV is a promising travel alternative that could help reduce road deaths and injuries [4]. Researchers predict AVs will enhance road safety standards and management [5]. Consideration of security aspects becomes paramount when preparing the integration of AV technology in urban environments. Recent studies using unique data sets, including detailed AV accident data, have begun to reveal the specific conditions and manoeuvres that caused accidents, informing the development of targeted safety management strategies and actions to reduce those risks [6]. In this trajectory toward a safer and more intelligent transportation ecosystem, the inclusion of diverse AV modes, encompassing private cars and buses, assumes paramount importance. These distinct AV modes promise to not only enhance individual travel experiences through advanced technology but also revolutionize public transportation, contributing to the overarching goal of creating a safer and more seamlessly integrated urban mobility network.

AVs are becoming increasingly able to sense surrounding environments without the need for human interactions. The implementation of AVs has potential benefits to urban areas, including increasing climate resilience by providing more reliable and safer transport alternatives, reduced carbon emissions via switching to battery charging or improved driving efficiency, and reducing the need for a city centre and thereby allowing for additional space for green infrastructure to facilitate sustainable living. Moreover, the incorporation of Avs into public transport systems has the potential to minimize spatial requirements in urban areas. This opens up avenues for expansive green initiatives, not only aimed at promoting sustainable living but also addressing the urgent need for environmentally sensitive urban development.

Additionally, the utilization of Avs as a mode of shared mobility assumes a crucial role in alleviating traffic congestion across the city. These reductions directly contribute to easing traffic gridlocks, facilitating the creation of a car-free environment that fosters a transition towards more pedestrian-friendly spaces. It is estimated that the deployment of Avs in urban areas will result in a substantial 35% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, representing a significant stride towards a more visionary urban future [7,8].

To properly address the implications of urban mobility’s shift toward more pedestrian-friendly environments, we must investigate the continuing transition from a human-centred to an autonomous-centred driver paradigm. This phase includes a diverse mix of semi-AV, fully AV, and non-AV, and displays a diverse set of barriers and opportunities. The co-existence of several AV technologies on the same roads needs a thorough understanding of the security, safety, and operational difficulties that occur, as well as the design of effective methods to alleviate these barriers.

The ability to distinguish between densely populated metropolitan areas and non-urban areas, such as suburbs, peripheries, intercity routes, and roadways, has a substantial impact on a number of sectors. AV infrastructure requirements in urban and non-urban environments might greatly vary, to start [9]. In urban areas, handling dense traffic and pedestrian interactions may need complex signalling systems, dedicated lanes, and extensive mapping. On the other hand, in non-urban settings, highway safety features and long-distance efficiency may take precedence. Furthermore, the primary uses of AVs in urban areas are last-mile issues, traffic reduction, and the enhancement of public transit [10,11]. To improve sub-urban connection and long-distance transport, AVs can also be used in non-urban areas. The adoption of AVs in urban regions may have various social and economic consequences, as opposed to non-urban situations. For instance, it might affect urban public transportation systems and lessen isolation in isolated communities. Furthermore, alternative strategies may be required to be used by legislative frameworks that approve the use of AVs [12,13,14]. In metropolitan areas, laws concerning zero-emission zones and the integration of AVs into public transport may be necessary, whereas high-speed travel safety requirements may have greater significance in non-urban areas.

According to the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) [15], there are six levels of driving automation ranging from 0 (fully manual) to 5 (fully automated). Level 1 has the lowest level of automation, limited to providing warnings, and Level 2 has partial driving automation that can control both acceleration/deceleration and steering. Levels 3 and 4 have substantial driving automation capabilities compared to lower levels. However, the fundamental difference between Levels 3 and 4 is that level 4 automation can intervene in case of a system failure. Level 5 means fully automated AVs (level 5 driving automation); they are not currently commercially available, and testing has only taken place in controlled environments [16]. Fully commercial AVs are not available in the market and in urban spaces. There has been no testing as to how Level 5 vehicles could undergo widespread adoption onto road networks. This applies to both AVs integrated into public transport systems and those used as private cars.

The current state scenario of fully automated Avs is marked by significant advancements and persistent challenges. Leading companies include Waymo, Cruise, Tesla, and Baidu. Waymo is the first to introduce a completely autonomous taxi service in Phoenix, Arizona, demonstrating the commercial use of Level 5 autonomy [17]. A significant advancement for commercial AV services, Cruise has also gained approval for autonomous rides in San Francisco [5]. Regulatory barriers, safety concerns, and technological difficulties prevent the AV market from being widely adopted despite these developments. With rising investments from major automakers and tech companies, the market is anticipated to increase at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.3% between 2021 and 2030 [18]. Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), radar, cameras, and artificial intelligence algorithms are some of the critical technologies that enable autonomous vehicles to navigate. Luminar and Waymo, for example, prioritise LiDAR sensors for improved vehicle vision, whereas Tesla focuses on AI and data to develop autonomous driving capabilities [19]. Additional companies involved in AV technology include Cruise, Aurora, Argo AI, Zoox, and Wayve.

As AV technology is rapidly advancing, there is a growing need to explore how an increased usage of AVs can impact our urban areas to put necessary plans and processes in place before having AVs appear in our transportation systems. To date, most research conducted on AVs has considered the development and adaptation of the technology itself with some primary focus on private vehicles. There is little research investigating the attitudes of road users towards AVs, and how the wide uptake of AVs can impact the utilization and design of urban areas. Therefore, a systematic review is carried out in this study to investigate the role of AVs in urban areas by considering:

- RQ1: What are the attitudes and behaviours of road users towards AVs?

- RQ2: How would the infrastructure be changed to enable AVs in urban areas?

- RQ3: How and in what way will the regulations and legislations around AVs evolve with a focus on urban areas?

- RQ4: What are the implications of AVs for urban areas in terms of achieving sustainable living, climate mitigation, and adaptation targets?

The outcomes of this review will inform us about the key roles that Avs in public transport play in the sustainability design of urban regions, and user attitudes, perceptions, and behaviour. Moreover, this research will advance our understanding of how urban design should change for accommodating AVs in urban areas. This systematic review will provide some useful information to policy makers to consider how to organise cities and urban areas to accommodate new mobility services.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review of the literature is performed using the databases of Scopus and Web of Science to search answers for the research questions raised in the introduction. The systematic review uses a qualitative text mining software, NVivo 12, to analyse, organise, and uncover insights [20].

There are several different approaches to undertaking a systematic literature review. In order to decide the most appropriate approach for this systematic review, we undertook a critical review on previous studies that undertook systematic reviews in several related academic disciplines (Table 1). All studies utilized the PRISMA approach (see Supplementary Materials), i.e., the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. This method ensures transparency and complete reporting of research. As such, this paper applies a methodology consistent with other authors [21]. The scope includes peer-reviewed conference papers. Furthermore, the search was exclusive to documents produced from 2003 to 2023 and documents published in the English language only. To narrow the search area, this method uses a four-step clustering algorithm (i.e., Scope, Target Group, Subject Domain, and Methods). To simplify, this process of narrowing down involves excluding somewhat unrelated studies. It is done by using the OR operator within the keywords of each category and the AND operator within each group [22]. This helps refine the search to find more relevant information. Hence, this review was developed based on the intersection area of all four clusters.

Table 1.

Article selection process from literature.

2.1. Keywords Selection

Selecting keywords for a systematic review entails careful consideration to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature. The selection in this paper was on the basis of relevance to research questions, inclusiveness, variability (including synonyms), and consultation among the researchers. For the scope cluster, the terms “Autonomous Vehicles” AND “Urban Areas” were used to define the largest scope with what the search should start. In addition to that, synonyms such as “Self-Driving Cars”, “Intelligent Vehicles”, “Driverless Cars”, “Urban Spaces”, “Urban Environments”, and “Downtown Areas” were considered.

The target group of this review was primarily concerned with the subsets of urban areas. The main terms for the target group cluster were: “sustainability”, “climate mitigation”, “climate adaptation”, “legislation”, “attitudes and perception, and user behaviours”, “user benefits”, “legislations and regulations”, “Infrastructure”.

The subject domain of this review was concerned with the subsets of the target group. The main terms for the subject domain were: “Awareness and education”, “Consumer behaviour and the environment”, “Social norms and values”, “Attitude-behaviour change interventions”, “Economic benefits”, “Social benefits”, “Environmental benefits”, “Adaptation and decision making”, “Resilience to climate change impacts”, “Risk management”, “Resources management”, Low-carbon transportation”, “Renewable energy sources”, “Mitigation measures”, “Industrial decarbonization”, “Enforcement and compliance”, “National polices”, “Safety and comfort standards”, “Environmental regulations”, “Sustainable development”, “Circular economy”, “Corporate social responsibility”, “Accessibility, equity and social justice”, “Trust and credibility, “User preferences and needs”, “Expectations and satisfaction”, “Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I)”, “Roadway design”, “Charging stations”.

The fourth group, the methods of data collection or handling based on the collective approach of data, was assigned. The terms included in this cluster were “questionnaire”, “survey”, “interview”, “participants”, “modelling”, and “intervention”.

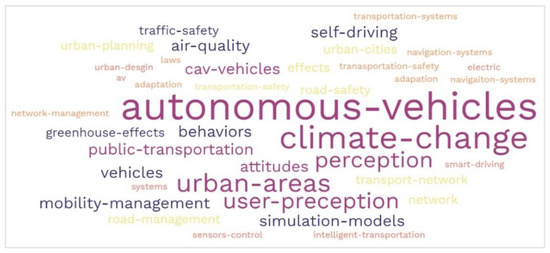

A word cloud of the most frequent keywords was generated as shown in Figure 1. The purpose of this is to observe the common themes and repeated words among the search results.

Figure 1.

Word cloud of search results.

2.2. Database Search

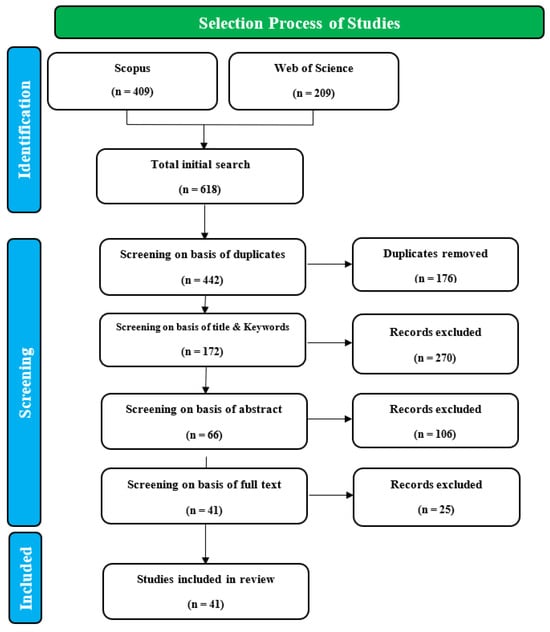

The search through Scopus and Web of Science databases was performed, and generated 409 and 209, respectively. Articles were merged and duplicates were removed, reducing the number to 442 articles. Among these articles, 112 were conference papers, while the rest were peer-reviewed articles.

Establishing and adhering to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria is imperative for maintaining the rigour, transparency, and focus of a systematic review. These criteria act as a set of predefined rules that guide the selection of studies for analysis. The inclusion and exclusion criteria concentrate on relevance and precision, minimization of bias, consistency, and reproducibility, and addressing the research questions. Under these criteria, any articles unrelated to the main scope (i.e., both autonomous vehicles and urban areas), whether directly or indirectly, were excluded straight away. The primary focus of this review was on urban areas; hence, articles related to rural areas were removed. Similarly, articles that were not concerned with autonomous vehicles were also excluded. Furthermore, if the criterion was met, an additional verification was necessary to ensure that the studies under consideration had explicitly mentioned a framework or index either in their title or keywords. For the first screening stage, both conditions are applied to the 442 articles, hence reducing the number of articles by 270.

In the second screening stage, abstracts were examined with regards to the target group and subject domain (i.e., sustainability, climate mitigation, and climate adaptation). In this stage, the focus was on the target group and subject domain, specifically sustainability, climate mitigation, and climate adaptation. By narrowing down the selection based on these criteria, the aim was to ensure that the studies under consideration were directly aligned with the core themes of the systematic review. This step is crucial to maintain relevance and address the specific research objectives. This stage excluded 106 articles, reducing the total number of articles to 66.

In the third screening stage, full-text articles were also investigated based on the target group and subject domain (i.e., sustainability, climate mitigation, and climate adaptation). This stage involved the examination of full-text articles which allowed for a more detailed evaluation of the articles in terms of their relevance to the target group and subject domain. This thorough examination aimed at maintaining a high standard of quality in the selected studies, ensuring that only those with substantive contributions to sustainability, climate mitigation, and climate adaptation were retained. This round was the last one and reduced the total number of included articles by 25. Subsequently, 41 studies were selected to be included in this analysis. Although the final number of included articles, 41, may appear relatively small, the emphasis was on quality over quantity.

The systematic review was concerned with selecting studies that meet rigorous criteria that enhance the reliability and validity of findings. Emphasizing a smaller, more focused sample is a standard strategy in systematic reviews, ensuring methodological rigour and a comprehensive examination of the literature. All the identification and screening stages are summarized and better demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Selection process of studies—identification of studies via databases (this study).

Figure 2 illustrates the process used for the identification of relevant studies, displaying how various databases were systematically searched and filtered to compile the research material. This graphical representation serves as a clear visual aid, detailing the methodology behind the selection of studies, including the criteria for inclusion and exclusion, ensuring transparency and replicability in the research process.

2.3. Utilizing NVivo for In-Depth Coding and Analysis in Systematic Review

In this study, the researchers used NVivo software to code the articles. This approach was informed by the established literature emphasizing the benefits of using NVivo for systematic research [27]. Although inclusion and exclusion criteria shape the initial selection of studies, coding approaches contribute to the subsequent analysis. Collectively, these components create a comprehensive and structured framework for conducting a systematic review. The researchers in this study employed both inductive coding, where themes and patterns emerge directly from the data, and deductive coding, which involves using existing theories or concepts to analyse the data. Themes were systematically constructed based on inductive and deductive approaches. The inductive approach is primarily guided by the data itself and remains unaffected by any preconceived frameworks or the researcher’s initial assumptions. The analysis is primarily driven by the data, aiming to reduce bias, and allowing it to shape the conclusions. In contrast, in the deductive approach, the researchers may provide a less detailed description of the overall data. This is because they are influenced by their own theories and interests, leading them to focus more on certain aspects of the data for a more thorough analysis. The codes were then grouped into themes, which played a crucial role in developing the conceptual framework for AVs in urban areas. The paper thoroughly discussed all the codes that appeared across the 41 articles.

2.4. Geographical Coverage and Cross-Tabulation Analysis

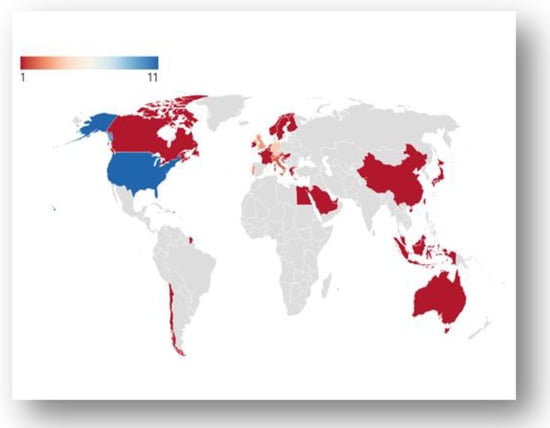

A geographical coverage map was drawn to present the distribution of the 41 articles across the globe (Figure 3). Articles were found in 31 countries and across 4 continents, which are as follows: 22 from Europe (Spain, Germany, Greece, Portugal, Switzerland, France, UK, Belgium, Hungary, Italy, Greece, Croatia, Netherlands, Austria, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Ireland), 10 from America (USA, Chili, Canada), 7 from Asia (UAE, KSA, Taiwan, China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan), 1 from Africa (Egypt), and 1 from Oceania (Australia).

Figure 3.

Geographical coverage of research across the globe (this study).

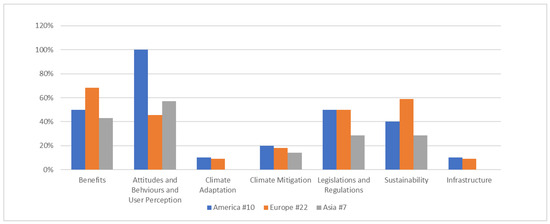

A cross-tabulation analysis was carried out considering the seven main themes with particular attention to regions specified as follows: America, Europe, and Asia, with case studies published in journals and conferences.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of each category based on different regions. As illustrated in Figure 4, benefits are some of the most prominent considered factors of the papers written in America, Europe, and Asia. The Europe region has considered all seven factors. Both Europe and America regions considered factors such as benefits and legislation and regulations and sustainability almost equally. However, Asia pays less attention to climate mitigation and adaptation compared to America and Europe. One could argue that the lower use of cars in comparison to developed countries might contribute to this situation [28]. To clarify, they might not fully recognize the changing climate, therefore resulting in a lack of proactive adaptation and mitigation measures. In addition, the Asia region did not consider infrastructure as a factor of investigation.

Figure 4.

Distribution of each factor based on different regions (this study).

3. Results

3.1. Themes and Sub-Themes in the Systematic Literature Review

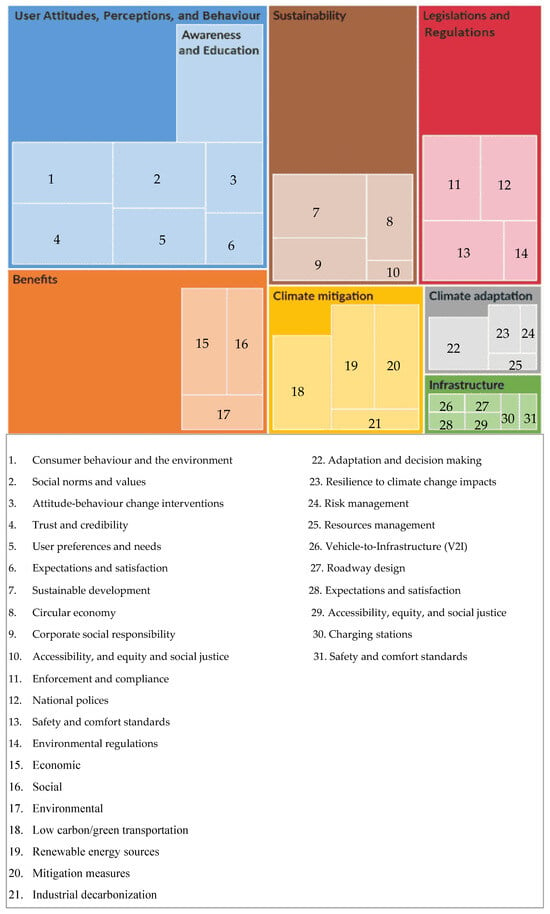

Upon conducting the systematic review, 41 articles were identified and selected in this review. Seven different themes and thirty-two sub-themes were obtained using a hybrid model which considered inductive and deductive approaches (selection process detailed in the above methodology). This methodology enables a comprehensive investigation of the present status of knowledge regarding AVs, including both newly discovered insights and those informed by pre-existing theoretical frameworks. The seven themes include: benefits, user attitudes, perception and behaviour, climate mitigation, legislation and regulations, sustainability, and infrastructure (Table 2). The sub-themes are shown in Figure 5. By highlighting particular aspects of each theme, these sub-themes provide the overall themes with more depth. This detailed approach guarantees a thorough examination that is attuned to the complex aspects of the selected themes. This section describes and discusses the current state of knowledge as related to these themes and sub-themes.

Table 2.

Main categories and themes.

Figure 5.

Main categories and themes based on mapping output exported from NVivo (some details were added to it).

3.2. Benefits

The benefits theme was created with three sub-themes: economic, social, and environmental. These sub-themes were given a wide scope to accommodate the benefits of AVs in urban areas. From a social and economic perspective, according to studies [29,30,31], AVs in public transportation have improved traffic flow and reduced congestion. By decreasing transportation times and related expenses, these developments improve the economic efficiency of urban areas.

Additionally, an increased access to AVs improves the welfare of workers, travel distances, and city size [31]. The implementation of AV in urban areas could have positive impacts on public transportation. This is in terms of lower risk of traffic incidents and higher traffic efficiency compared to other modes [32].

Moreover, AV fleets have positive environmental impacts on land use. Urban parking spaces may be reduced to as much as 90% when AVs are implemented in ridesharing mode [32]. These include increased efficiency in traffic management and routing, the possibility of platooning to cut fuel consumption, optimized vehicle utilization through ride-sharing services, and the promotion of shared transportation. It is critical to recognize that the environmental impact of AVs is determined not only by the energy source or combustible used (such as electric or non-polluting cars, green hydrogen), but also by mode of transportation (public versus private).

An assessment of AVs in urban areas demonstrated positive effects on network capacity and traffic stability. These effects are achieved as the AV penetration rate (% of AVs in roads) increases above (10–20%) [33]. Similarly, some studies indicate a substantial increase in accessibility and encouragement of urban sprawl from AVs [34,35,36,37]. This confirms the earlier findings [38,39].

AV shuttles improve current transit services by making cost-efficient benefits [32]. Associated environmental benefits include improved air quality with average reduction of nitrogen dioxide concentrations up to −4% [30,40,41]. AVs and micro mobility can improve transportation landscape and safety [42].

The system of electric AVs can reduce journey time, free up parking in urban areas, and generate cost benefits for customers [43,44,45].

AVs can promote an increased usage of public transportation in urban areas [46]. Additionally, AV technology could solve many of the traffic issues [47].

There is, however, a high impact of occlusions on the safety of cyclists in urban intersections, while the maximum detection range of the AVs sensor systems has a minor influence in the considered scenario [48]. Public transport use could fall by 18% [49]. Walking and cycling could fall by 13% and hence reduce their health benefits [49].

3.3. User Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behaviour

The user attitudes, perceptions, and behaviour theme was created with seven sub-themes: awareness and education, consumer behaviour and the environment, social norms and values, attitude–behaviour change interventions, trust and credibility, user preferences and needs, and expectations and satisfaction. The emerging sub-themes have been considered in diverse ways in previous studies. To elaborate, several earlier studies have used these sub-themes in their investigations. In terms of consumer behaviour and the environment, passengers tend to be more interested in arriving at the desired location at a lower price than in AV technology [50]. From an attitude–behaviour change perspective, Avs in both private and public transportation improve people willingness to travel further [31]. Hence, homes and workers could be moved in the long term.

The introduction of Avs in the transportation systems could result in considerable changes of travel behaviour, mode choice, and car ownership [48]. To cause an attitude–behaviour change intervention, governments may impose incentives or restrictions on private and public transportation [51]. Additionally, the planning principles for mobility services based on AVs such as less flexible travel motivations could have a direct effect on passengers [52].

The implementation of AVs into the transportation system could promote the use of public transportation (i.e., bus, trains, and trams) [53], causing a behaviour shift among the populace. The improvement of public transportation large-scale restricted traffic areas and pedestrian areas induces a significant modal shift towards better environmentally friendly alternatives [54]. Furthermore, the value of trip time for AVs will potentially decrease significantly, as individuals will be more productive in AVs [55].

On the contrary, in terms of social norms and values, AVs create a social dilemma [56]. Although most individuals think that everyone would benefit from utilitarian AVs (those that reduce the number of fatalities on the road), these same people have a personal motive to travel in AVs that protect them at all costs. Moreover, the projected distribution of accessibility impacts could encourage public transportation to be superfluous [34].

AVs show immense potential for future mobility development, not only in large cities and urban areas, but also in suburban and rural locations [50]. There are special issues in these places due to limited availability and access to public transportation. AVs are seen as a potential answer to these difficulties by delivering on-demand transportation services that can serve a variety of interest groups, transcending the restrictions of traditional bus lines with set bus stops to enable the effective implementation and adoption of autonomous vehicles in rural areas, it is critical to understand the local residents’ needs and expectations. Factors like availability, accessibility, and cost have a significant impact on how users perceive autonomous mobility services. Whether they are thinking about using private or public transportation, people carefully analyse these factors, which shapes their views and choices [50]. Moreover, respondents saw fewer crashes as the primary benefit of AVs, showing a positive view of safety improvements [57,58]. Their main issue, however, is device failure, emphasizing the importance of dependability and faith in technology. In terms of willingness to pay (WTP), the average WTP for adding complete (Level 4) automation to their vehicles ($7253) is much greater than the WTP for adding partial (Level 3) automation ($3300) [59]. This indicates that that responders may be more willing to accept fully autonomous capabilities. Another factor to consider is the influence of demographics and travel characteristics. This is with respect to how income, gender, technological familiarity, urban residency, and crash experience influence respondents’ interest and WTP for AV technologies [57]. Similarly, this influences the adoption of shared AVs. This is according to rates of adoption of shared AVs under various pricing scenarios, considering the influence of peers’ adoption decisions [57]; it not only affects this, but also home-location decisions. This means analysing how the availability and prevalence of AVs and SAVs influence people’s decisions about where to live [57].

Another researcher focuses on addressing the problem of jointly detecting pedestrians and recognizing 32 pedestrian attributes from a single image [52]. These characteristics include visual appearance, behaviour, and road crossing predictions, which are major safety concerns. AVs can enable safe interactions with pedestrians in urban contexts by making decisions that take into consideration the presence and characteristics of pedestrians [52]. Correlations between users’ sociodemographic traits, mobility preferences, and predicted aspects or features of mobility services offered by AVs are discovered through surveys and studies [59]. A framework for organizing mobility services based on AVs is provided by insights by considering customer preferences and expectations. The acceptance and usability of AVs in urban environments are eventually improved by this user-centric approach, which assists in designing services that are in line with passengers’ wants and preferences [59,60].

3.4. Climate Adaptation

Climate adaptation involves implementing strategies to modify systems, processes, and behaviours in response to climate change effects [61]. Within this theme, four sub-themes were identified: adaptation and decision making, resilience to climate change impacts, risk management, and resources management. In terms of resilience to climate change impacts, AVs might bring health risks like air pollution, noise, and less physical activity all things that connect to climate concerns [32]. Nonetheless, given the right rules and regulations, these self-driving vehicles could actually make our streets safer, reducing the chances of accidents [32]. From a resilience to climate change impacts perspective, a study examined the effects of AVs on pollutant in a medium-sized Portuguese urban region using numerical modelling [62]. Results indicate a small rise in emissions with 30% of AVs penetration (% of AVs in in the road network), but a significant 30% reduction when these AVs are electric; hence, this promotes a future of greener and healthier communities. For the same reason, adaptation and decision-making efforts can benefit from promoting healthy AV use patterns, particularly by incorporating entirely electric vehicles in ride-sharing and ride-splitting systems. To ensure positive adaptation and health outcomes, establishing appropriate rules and regulatory frameworks before widespread AV deployment is crucial [32,62].

3.5. Climate Mitigation

Climate mitigation refers to efforts to reduce or eliminate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the atmosphere in order to alleviate the causes of climate change [63]. The climate mitigation theme was generated with 4 sub-themes: low carbon/green transportation, renewable energy sources, mitigation measures, and industrial decarbonization. When AVs operate exclusively on electric power sourced from renewables, participate in ridesharing initiatives, and seamlessly integrate with public and active transportation modes, they offer substantial potential for public health benefits. These characteristics collectively promote physical activity, enhance urban environmental conditions by improving air quality and reducing noise, and contribute to a healthier urban design by freeing up more public space [32]. This holistic approach reflects a shift toward sustainable and health-conscious urban mobility solutions.

Other researchers looked at the effects of AVs on the environment, especially how they affected urban air quality, with a focus on Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) emissions in a medium-sized urban region [40,41,62]. These studies find that the electric autonomous option results in significant reductions in NOx emissions by comparing three scenarios, including a baseline representing current traffic conditions, an autonomous scenario with a 30% AV market penetration, and an electric autonomous scenario with 30% battery-electric AVs. This highlights the potential for AV technology to aid in climate adaptation by reducing emissions by improving urban air quality and has a direct impact on cities’ resilience and sustainability [32]. This connection stems from the knowledge that better air quality reduces environmental impact and promotes long-term resilience, which are characteristics of sustainable activities. Sustainable urban development is taking steps to limit negative environmental effects. Cities may build more resilient and sustainable environments for their citizens by cutting emissions and improving air quality. Clean air initiatives support larger environmental responsibility objectives and improve a city’s capacity to adapt to changing conditions.

On the other hand, serious risks can arise when AVs are adopted for personal use, depend on fossil fuels, lead to more kilometres driven, increased traffic congestion and occupation of public spaces. All these factors contribute to increased inactivity, deterioration of the urban environment (air quality and noise), and reduction of public space available for social interaction and physical activity [32].

3.6. Legislation and Regulations

The legislation and regulations theme was produced with 4 sub-themes: enforcement and compliance, national polices, safety and comfort standards, and environmental regulations. Due to the lack of legislation, autonomous vehicle deployment and operation require some form of regulation [55,64,65]. The inherent need for AV technology to address privacy and security concerns emphasizes the imperative to resolve potential issues in these areas [64].

The absence of an AV regulatory framework contributes to technological ambiguities and hazards that require resolution [64]. The real-world implications extend to urban planning, impacting parking optimization, land rents, and mass transit, with potential regulatory consequences [31,32]. The adoption of proper policies and regulatory frameworks emerges as essential for AV implementation [32]. The usage of public spaces more frequently, a greater reliance on fossil fuels, and increasing traffic congestion are some potential dangers connected to the deployment of AVs. These dangers stress on how urgently strict laws and regulations are essential. Reducing these risks and making sure that AVs will improve urban mobility and environmental sustainability can be attained by regulating the use of renewable energy, managing traffic, and encouraging the use of shared vehicles. This demonstrates how good governance may transform opportunities to increase the efficiency and environmental friendliness of transportation networks from barriers to AV adoption. This involves comprehensive laws considering relevant deployment factors, including environmental effects and public health [51].

The safety of AVs for use in congested metropolitan streets is acknowledged, underscoring the requirement for restrictions to ensure their safety and dependability before integration into regular city traffic [66]. Shared-use AVs present opportunities to lower taxi costs and enhance economic effectiveness in public transportation [66]. Governmental measures to support and encourage shared-use AVs and diverse public transportation options are deemed feasible. The potential for individually owned AVs to travel unattended may require regulation, particularly in areas where this could contribute to traffic congestion.

Considering the diverse landscape of AV possibilities, city officials crafting transportation policy must weigh these options [66]. This highlights the significance of factoring in the effects of AVs when developing transportation laws, potentially resulting in the adoption of specific legislation and standards [44,59,66]. Regulatory measures become imperative for influencing demand across various transportation modes, encompassing AVs, private vehicles, and public transportation [36]. The design of transportation systems, be it private or shared AVs, necessitates legislation governing their operation and integration with existing modes [36]. Urban infrastructure must adapt or undergo a complete redesign to support AVs, emphasizing the need for regulatory measures to guide this transformation [36,37,67,68,69,70].

In essence, navigating the regulatory landscape for AVs involves a comprehensive approach that considers safety, urban planning, and the integration of diverse transportation modes, underscoring the pivotal role of legislation and regulations in shaping the future of transportation.

3.7. Sustainability

The sustainability theme have 4 sub-themes: sustainable development, circular economy, corporate social responsibility, accessibility, and equity and social justice. These sub-categories are identified with respect to the broader perspective of sustainability. Cities may be able to lower the number of single-passenger vehicles on the road by implementing AVs for public transportation, resulting in lower emissions and better air quality [35,65,71]. By encouraging more effective and environmentally friendly transportation options, this can help ensure the long-term viability of urban transportation systems.

Other sustainability aspects include enhancing public transportation and restricting individual vehicle use and urban sprawl [42,46,55]. By enabling a broad dissemination of shared vehicles that might support the mass rapid transit network, the introduction of AVs is considered as a chance to increase the allure of public transportation. By improving public transportation, this attempts to persuade more people to utilize sustainable means of transportation instead of private vehicles, so lowering traffic congestion and emissions [43,44,67,68,72]. To urge sustainability, there is a need to plan the transition towards incorporating autonomous electric vehicles into the urban system [45]. Moreover, implementing travel demand management methods, in conjunction with automobile use limitations and car-free zones, is considered as a way to control transportation demand and reduce reliance on individual cars. This strategy tries to reduce urban sprawl, which is the outward expansion of metropolitan areas that can result in longer distances between various parts of the city and a greater reliance on private automobiles. This encourages a more compact and sustainable urban development pattern by reducing urban sprawl.

The introduction of autonomous vehicles and other new mobility technologies could have both direct and indirect consequences on urban mobility and structure, which raises concerns about sustainability [36]. Although it is evident that AVs would improve safety and traffic flow immediately, it is important to think about the larger implications, some of which may have unforeseen effects. One such worry is the possibility of rising demand and congestion, which might affect not just traffic dynamics but also the design and layout of urban areas and possibly encourage urban sprawl [36]. Extensive travel times and a greater reliance on private automobiles between different city districts can result from urban sprawl, which is characterized by the outward spread of metropolitan centres. The sustainability aspect comes into focus as urban sprawl is recognized as a phenomenon with long-term adverse effects on the environment, society, and the economy [36,73].

3.8. Infrastructure

The infrastructure theme was created with six sub-themes: Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I), roadway design, expectations and satisfaction, accessibility, equity, and social justice, charging stations, and safety and comfort standards. These sub themes have been obtained with consideration to previous studies [44,70,73]. The development of AVs and road safety are coupled to infrastructure. The connectedness of vehicles to other vehicles (V2V) and to everything (V2X), including other vehicles (V2I), enables real-time communication between vehicles and their surroundings. The rapid information sharing made possible by the rollout of 5G, and other high-speed data transfer technologies will assist AVs and enhance road user safety in general, including pedestrian safety, by offering users with timely access to critical information. These infrastructure investments are necessary for the widespread deployment of AVs as well as the safer and more efficient operation of the transportation ecosystem [44]. There are several factors to consider when implementing AVs into the transportation network which are charging infrastructure, dedicated lanes, safety measures, and exposure to electromagnetic radiation [44]. An efficient charging infrastructure is necessary for electric AVs to operate well in urban areas. This infrastructure gives AV users choice by including both wireless and plug-in charging alternatives [44]. Vehicles can charge via plug-in charging, which is dependent on physical connectors at charging stations. Wireless charging, on the other hand, makes charging more convenient by doing away with the necessity for direct contact with charging stations.

To ensure a smooth and safe flow of AV traffic, the integration of AVs into urban environments may also call for the construction of dedicated lanes [44]. These lanes improve general traffic safety in addition to the effectiveness of AV operations.

Road safety standards must be followed, and strict safety measures must be implemented in order to ensure the safety of AVs [44]. Evaluating potential risks, such as exposure to electromagnetic radiation, becomes essential when comparing various infrastructure solutions, in addition to standard safety concerns [44]. This emphasizes the significance of a thorough assessment and management of any possible health or safety risks connected to electromagnetic radiation emissions from unmanned aerial vehicles.

For the successful integration of AVs into urban contexts, it is essential to create a supportive infrastructure. Outside of the charging features, specific lanes and stringent safety protocols are essential for achieving a seamless integration that improves urban mobility’s efficiency and safety [44].

Other major factors to consider are intelligent transportation systems (ITS), road infrastructure upgrades, parking infrastructure, communication infrastructure, and urban planning and development [49,73]. Developing and implementing ITS that enable AVs to interact with one another as well as with infrastructure features such as traffic lights, road sensors, and other vehicles can enhance overall traffic flow and safety [70]. To support their navigation and operations properly, AVs may require specific road infrastructure enhancements such as improved road markings, signage, and dedicated lanes. AVs navigate and make choices using a variety of sensors and communication technologies [70]. Creating a dependable data and communication infrastructure is critical to ensuring continuous connectivity and information exchange. AVs have the potential to influence urban structure and development [70]. As a result, urban planning rules and guidelines must be revised to accommodate AVs, including adjustments to road networks, land use patterns, and zoning regulations.

Table 3 provides a detailed overview of the study characteristics, offering a comprehensive summary of the key themes addressed in each article. This table serves as a valuable resource for readers to quickly grasp the scope and focus of the research conducted across numerous studies included in this analysis. Additionally, it highlights the diversity of topics explored within the literature, aiding in the identification of trends and gaps in current research on the subject matter.

Table 3.

Study characteristics.

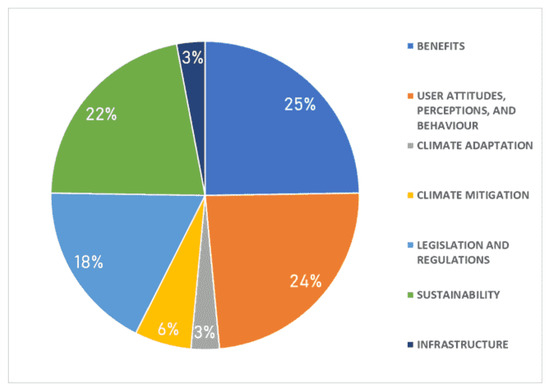

Figure 6 displays the hierarchical distribution of all derived themes and sub-themes, independent of the case study topics, following the coding of all available documents. Distinct colours are used to indicate the themes, and smaller boxes reflect the relative importance proportional to the size of the sub-themes. In general, the investigations covered the seven main themes. Themes that are frequently discussed include those related to benefits, attitudes and behaviours and user perception, sustainability, and legislations and regulations. Different sub-themes and hierarchical levels can be seen within each topic. The percentage of prominence of each theme across the 41 articles is illustrated in Figure 7. The highest percentage of prominence was for benefits (25%) followed by attitudes and behaviours and user perception (24%) and sustainability (22%).

Figure 6.

Themes and sub-themes hierarchy chart obtained from NVivo; hierarchy charts are coloured by hierarchy and sized by coding references.

Figure 7.

The prominence percentage of each theme across the 41 articles (this study).

4. Findings of the Systematic Review

A comprehensive tabulation of study characteristics, encompassing both articles and themes, was compiled and presented in Table 3 (refer to the Results section). The thematic distribution throughout the review articles in the systematic assessment displays a comprehensive exploration of diverse dimensions associated with the implications of AVs for urban areas. The main subject, “Benefits”, is a primary concern in 20 articles, signifying a substantial investigation into the positive outcomes and advantages related to this review. This emphasis highlights the importance of information on the potential advantages that AVs can offer.

“User Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behaviour” appears as another prominent theme, considered in 15 articles. This indicates a growing interest in comprehending how users engage with and reply to AVs, presenting valuable insights into the human elements of AVs in urban areas.

The themes of “Legislation and Regulations” and “Sustainability” are carefully aligned, with 15 and 16 articles respectively exploring these components. This suggests a concerted attempt to examine the legal frameworks and sustainable practices associated with the implementation of AVs. The delicate corporation legal frameworks and sustainable practices is clearly a key focus of the scholarly discourse.

Although “Climate Mitigation” is explored in five articles, “Climate Adaptation” and “Infrastructure” emerge with a more limited presence, considered in two articles each. These themes, despite the fact that they are much less pervasive, indicate a recognition of the environmental and infrastructural dimensions related to AVs. As the field progresses and AVs continue to emerge, those themes can also permit further exploration to address potential gaps in understanding.

Overall, the thematic distribution within the systematic assessment highlights a balanced approach, with a strong emphasis on benefits, user perceptions, and the regulatory and sustainable components of AVs. This comprehensive approach lays the foundation for a refined understanding of AVs from various perspectives.

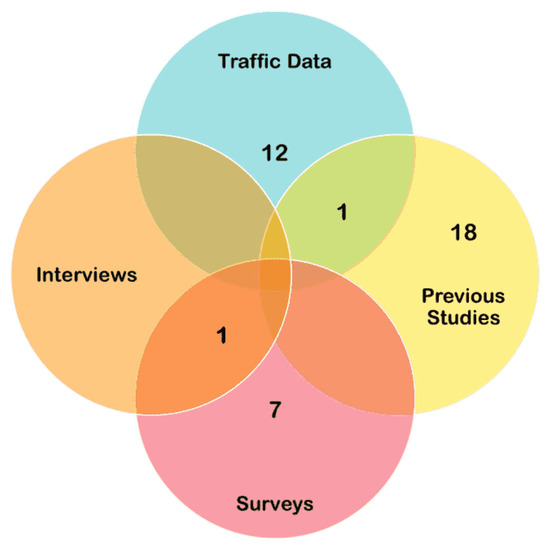

Furthermore, the methods of data collection and analysis of the 41 reviewed articles are shown in Table 4. This table reflects the comprehensive approach followed in this review. For the data collection methods, a substantial number of the studies used empirical evidence, with 12 articles employing traffic data to draw insights. 18 articles were conducted through a critical examination of previous studies, illustrating the need to build on existing knowledge. Surveys along with other approaches contributed to 9 articles. This provided a valuable resource to understand user attitudes, perceptions, and behaviour. Additionally, the singular study that combined surveys with interviews offered a more detailed exploration.

Table 4.

Methods of DC and DA in reviewed articles.

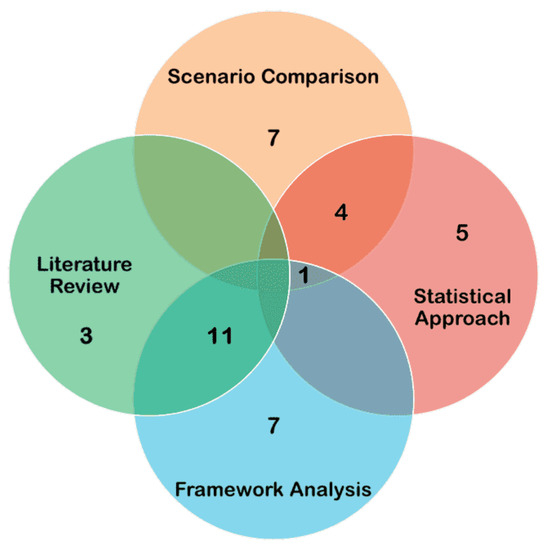

In terms of data analysis, the articles illustrated a diverse methodological approach. Scenario comparison along with statistical approaches were used in four articles, providing statistical rigour coupled with hypothetical exploration. The literature review method was employed in three studies. Moreover, the framework analysis along with literature review approach was prevalent in 11 studies. Followed by comparative analysis (five studies), analytical methods (two studies), and several combinations of framework analysis, scenario comparison and statistical approaches. Furthermore, Venn diagrams highlighting the frequent and common methods for both data collection and analysis were created as presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Data collection (Venn Diagram).

Figure 9.

Data analysis (Venn Diagram).

5. Discussion of the Approach and Limitations

In this study, a comprehensive review of the existing literature through a systematic review, utilizing both inductive and deductive coding approaches was conducted. The inclusion and exclusion criteria carefully shaped the initial selection of studies, forming a robust framework for analysis. This structured methodology allowed for a methodical examination of AVs in urban areas, investigating diverse aspects such as benefits, user attitudes, perceptions and behaviour, sustainability, and climate impact. The primary aim was to offer valuable insights for policymakers and provide guidance for the future development of transport systems and urban design.

Although the findings contribute significantly to informing policymakers on key considerations regarding AVs in urban areas, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations. Firstly, a notable geographic bias appeared, with a significant portion of identified articles originating from Europe and North America. This imbalance not only reflects disparities in resources and infrastructure but also influences the scope and focus of scientific inquiries, potentially overlooking or underrepresenting the challenges and opportunities present in other regions, particularly in the global south. This concentration may pose challenges in generalizing findings to regions with distinct urban transport systems and socio-economic contexts, warranting careful consideration. The implications of this geographical bias may result in AV technologies and urban integration strategies that are not suited to the unique needs, infrastructure, and regulatory landscapes of regions outside of Europe and North America. Overlooking the Global South in AV research neglects the distinct challenges and opportunities presented by these areas, including higher congestion levels, different road user behaviours, and varying infrastructure quality. Addressing these disparities is crucial to ensuring that AV technologies can effectively address the diverse transport needs of urban populations worldwide. The articles highlight a significant research gap in understanding the diverse impacts of autonomous vehicles across different geographic regions, including the Global South. This emphasizes the limitation related to geographic bias mentioned earlier. To better generalize findings, it would be appropriate to go into more detail on how future research should strive to incorporate a greater variety of urban contexts [74,75,76].

The limitation associated with small sample sizes for regions like Asia primarily affects the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Small sample sizes may not adequately capture the diversity and complexity of urban environments, cultural attitudes towards technology, regulatory landscapes, and infrastructural variations present across such a vast and heterogeneous region. This can lead to conclusions that are not fully applicable across different Asian contexts, potentially skewing perceptions of the benefits, challenges, and societal readiness for AVs.

One of the limitations of this systematic review stems from the decision to narrowly define the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of studies, which focused specifically on the role of AVs in urban areas. Although this approach enabled a detailed and focused analysis of the intersection between AVs and urban sustainability, it also necessitated the exclusion of broader research themes related to AVs and sustainability at large. Consequently, several relevant studies that could potentially offer additional insights into the sustainability implications of AVs, were not included within the scope of our review.

The lack of sufficient data and experimental results creates a significant constraint in drawing definitive conclusions about the role of AVs in urban environments. Although existing studies provide valuable insights and hypotheses, they are often based on limited datasets and experimental environments. As a result, the conclusions drawn from these studies may be subject to interpretation and revision as more comprehensive data becomes available.

It is crucial to acknowledge the uncertainty surrounding the future development of AV technology and its integration into urban contexts. Our systematic review attempts to navigate this uncertainty by critically evaluating existing literature and identifying key areas where further research is needed. By acknowledging the speculative nature of the topic, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with the evolving field of autonomous transport.

Works based on AVs “traffic data” are limited and we do not have a wide study about AVs in Urban spaces, so, many conclusions and results are based on limited data and hypothetical conclusions. The prospective of AVs to reduce traffic congestion and challenge the necessity of traditional public transportation infrastructure in future urban planning adds depth to the limitations around understanding the impacts of AVs on urban transport systems. This could be stated when discussing potential oversights in current AV research methodologies [76].

The dynamic nature of the field suggests that the identified themes and sub-themes may evolve as new research emerges, emphasizing the need for ongoing scrutiny and adaptation. Finally, the review focused exclusively on articles published in English, recognizing the language bias inherent in such a choice. Although English is prevalent in academic discourse, it is essential to acknowledge the potential existence of relevant research in other languages. The reflection on these limitations enhances the transparency of the approach and encourages future research to adopt more inclusive strategies.

6. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Forward Look

As AV technology is rapidly advancing, there is an urgent need to explore how those new mobility services will impact on urban transport systems, including the users, the infrastructure, and the design of future urban areas. This paper applies a systematic review to establish the current state of knowledge with regards to the role of AV in urban areas. It conducted a systematic review based on the studies found on literature that were produced from 2003 to 2023 using the PRISMA approach. Results of the systematic review show seven different themes and thirty sub-themes, with articles originating in thirty-one different countries, predominantly in the Global North. Studies related to benefits accounted for 25% of the sample, followed by behaviours and user perception (24%) and sustainability (22%). Least research has been undertaken on the role of AVs to support climate adaptation.

This systematic review sets the scene for considering how AVs can be implemented in urban areas, with a specific emphasis on their potential impacts on public transport. AVs in both private and public transport have the potential to improve road safety and increase access for older people or those living with disabilities. Nevertheless, it is crucial that AVs are introduced in an environmentally considerate way, so that they bring benefits in terms of climate mitigation, adaptation, and sustainability. The findings from two studies suggest that the integration of AVs and electric vehicles could significantly contribute to emission reductions and air quality improvements. This aligns with the focus on the impact of AVs on sustainability and climate adaptation, providing empirical data to support the optimistic viewpoint on AVs contributing to climate goals [74,75]. The continuous development of AVs and their implementation within the public transport system will be game changing. This is in terms of improving accessibility, efficiency, and promoting healthier communities. Insights suggest a significant shift in how urban spaces could be designed, moving away from centralized transport hubs to more distributed systems facilitated by AVs. This could inform a dynamic perspective on urban planning and infrastructure development, encouraging adaptable and AV-friendly cities [76]. Future work will consider the policy and infrastructure changes that are required to implement Level 5 AVs as a public mobility choice within urban areas within the UK.

Table 5 outlines recommendations for the integration of AVs into urban contexts. These recommendations emphasize the importance of environmental standards, public transportation integration, infrastructure development, and inclusive frameworks to ensure sustainable and equitable adoption of AV technology worldwide.

Table 5.

Recommendations for Sustainable Integration of AVs in Urban Contexts.

Based on the findings of this study, several actionable policy recommendations emerge for consideration. Policymakers should develop inclusive frameworks that consider the unique needs and conditions of diverse regions, especially those outside of Europe and North America. This includes facilitating the deployment and adoption in various urban contexts with particular attention to the Global South. Research institutions and governments should promote and adopt cross-regional studies to better grasp the geographical bias in AV research. This entails collaborating on studies that address the challenges and prospects of implementing AVs in the Global South. Investments in infrastructure that support the adoption of AVs and the broader sustainability goals should be prioritized. This is to effectively contribute to urban sustainability goals. Policymakers and governments should encourage international cooperation to establish regulations and standards that facilitate AV deployment across different urban and legal settings.

To ensure a more comprehensive understanding of AVs in urban areas, future research should prioritize inclusivity by focusing on diverse geographic regions, particularly those in the Global South. This can be attained through collaborative international research initiatives, localized pilot studies, and demonstrations tailored to varied urban environments. Engaging with cross-disciplinary stakeholders and allocating resources specifically for AV research in underrepresented regions are also fundamental steps. By broadening the geographic scope of AV research, insights can be developed that address local needs and contribute to more equitable and effective outcomes in AV deployment worldwide.

Future work should focus on how AVs integrate with existing transport systems and services. This entails examining into ways to smoothly include AVs in public transit systems. It is also essential for researchers to explore how AVs impact various transport methods like ridesharing, biking, walking, and how they shape urban mobility patterns and modal shifts. Additionally, investigating the role of Mobility as a Service platforms in proposing different travel options and improving urban transport accessibility is necessary. Additionally, understanding the social and economic impacts of AVs on urban communities is important. Research should assess how AV adoption influences urban land use patterns, property values, and real estate development. Furthermore, studying the labour market impacts of AVs, including job displacement and the emergence of new employment opportunities in AV technology development and maintenance, is essential. Exploring equity considerations such as access to AV mobility services for marginalized communities and addressing transport disparities in urban areas is necessary for ensuring inclusive and sustainable urban development.

Given the speculative nature of the topic, there is a clear need for future research to focus on empirical studies and real-world adoption of AVs in urban contexts. By prioritizing research efforts to produce robust data and experimental results, the potential impacts and challenges of AV integration can be better understood through evidence-based findings.

Drawing from the themes and sub-themes identified in this study, the following are potential research questions to guide future work:

- -

- RQ1: How might systematic reviews broaden their inclusion criteria to incorporate broader research themes related to AVs and sustainability?

- -

- RQ2: How will AVs perform in different urban environments, particularly in the Global South, given that congestion, traffic behaviour and infrastructure quality drastically differ from those in Europe and North America?

- -

- RQ3: What are the broader sustainability implications of AVs beyond urban contexts and how can they contribute to or undermine global sustainability goals?

- -

- RQ4: How can AV technologies be developed and deployed to ensure equal access and benefits for all urban populations, including small and minority communities?

Overall, this research will help improve our understanding on accommodating AVs in urban areas, which need further attention in future research. Furthermore, it will set a framework for policy makers to address key considerations related to AVs into future transport systems and urban design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/futuretransp4020017/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist. Ref. [77] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: E.J.S.F. and D.D.; data collection: H.Y.M.; analysis and interpretation of results: H.Y.M.; draft manuscript preparation: H.Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), grant code/EP/R007365/1.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that they did not use any original data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Badir Alsaeed and Safaa Ibrahim throughout this review. Ferranti’s time is funded by EPSRC Fellowship EP/R007365/1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest concerning the publication of this paper.

References

- Hancock, P.A.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Stewart, J. On the future of transportation in an era of automated and autonomous vehicles. Psychol. Cogn. Sci. 2019, 116, 7684–7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transport Systems Catapult. The Case for Government Involvement to Incentivise Data Sharing in the UK Intelligent Mobility Sector. March 2017. Available online: https://cp.catapult.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Transport_Data_Sharing_in_the_UK_Report.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. Road Traffic Injuries. December 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- DfT. Pathway to Driverless Cars: Proposals to Support. July 2016. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/536365/driverless-cars-proposals-for-adas-and_avts.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Fagnant, D.J.; Kockelman, K. Preparing a nation for autonomous vehicles: Opportunities, barriers and policy recommendations. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 77, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zou, Y.; Kong, X.; Wu, L. Investigating the impact of influential factors on crash types for autonomous vehicles at intersections. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Vaddadi, B. Automated vehicles and how they may affect urban form: A review of recent scenario studies. Cities 2019, 94, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massar, M.; Reza, I.; Rahman, S.M.; Abdullah, S.M.H.; Jamal, A.; Al-Ismail, F.S. Impacts of Autonomous Vehicles on Greenhouse Gas Emissions—Positive or Negative? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengilimoglu, T.; Carsten, O.; Wadud, Z. Infrastructure requirements for the safe operation of automated vehicles: Opinions from experts and stakeholders. Transp. Policy 2023, 133, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, K. Exploring the implications of autonomous vehicles: A comprehensive review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippl, J.; Truffer, B.; Fleischer, T. Potential impacts of institutional dynamics on the development of automated vehicles: Towards sustainable mobility? Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 14, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepis, D.; Purchase, S.; Olaru, D.; Smith, B.; Ellis, N. How governments influence autonomous vehicle (AV) innovation. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 178, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, B.; Collins, S.; Jones, R.; Martin, J.J.; Blumenthal, M.S.; Stanley, K.D. A Comparative Look at Various Countries’ Legal Regimes Governing Automated Vehicles. JL Mobil. 2023, 2023, 2. Available online: https://repository.law.umich.edu/jlm/vol2023/iss1/2 (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Parekh, D.; Poddar, N.; Rajpurkar, A.; Chahal, M.; Kumar, N.; Joshi, G.P.; Cho, W. A Review on Autonomous Vehicles: Progress, Methods and Challenges. Electronics 2022, 11, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE Levels of Driving Automation™ Refined for Clarity and International Audience. May 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/blog/sae-j3016-update (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Parkin, J. Urban networks and autonomous vehicles. In Cities for Driverless Vehicles: Planning the Future Built Environment with Shared Mobility; ICE Publishing: Miami Lakes, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.M.; Kalra, N.; Stanley, K.D.; Sorensen, P.; Samaras, C.; Oluwatola, T.A. Autonomous Vehicle Technology: A Guide for Policymakers; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MarketsandMarkets. Autonomous Cars Market by Level of Automation (Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, Level 4, and Level 5)-Global Forecast to 2030. MarketsandMarkets. 2021. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/near-autonomous-passenger-car-market-1220.html (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Tesla, Inc. AI. Tesla. Available online: https://www.tesla.com/AI (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- McNiff, K. What is Qualitative Research? November 2016. Available online: https://lumivero.com/resources/what-is-qualitative-research/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Alsaeed, B.S.; Hunt, D.V.L.; Sharifi, S. Sustainable Water Resources Management Assessment Frameworks (SWRM-AF) for Arid and Semi-Arid Regions: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, H.F.; Hunt, D.V.; Rogers, C.D. Urban Sustainability and Smartness Understanding (USSU)—Identifying Influencing Factors: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanamge, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Goonetilleke, A.; Kamruzzaman, M. How can gamification be incorporated into disaster emergency planning? A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2020, 11, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Desouza, K.C.; Butler, L.; Roozkhosh, F. Contributions and Risks of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Building Smarter Cities: Insights from a Systematic Review of the Literature. Energies 2020, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicianno, B.E.; Sivakanthan, S.; Sundaram, S.A.; Satpute, S.; Kulich, H.; Powers, E.; Deepak, N.; Russell, R.; Cooper, R.; Cooper, R.A. Systematic review: Automated vehicles and services for people with disabilities. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 761, 136103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masello, L.; Sheehan, B.; Murphy, F.; Castignani, G.; McDonnell, K.; Ryan, C. From Traditional to Autonomous Vehicles: A Systematic Review of Data Availability. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2022, 2676, 161–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, C.; Murphy, K.; Meehan, B.; Thomas, J.; Brooker, D.; Casey, D. From screening to synthesis: Using nvivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 579–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, D.A.; Dugas, L.R.; Bovet, P.; Forrester, T.E.; Lambert, E.V.; Plange-Rhule, J.; Schoeller, D.A.; Brage, S.; Ekelund, U.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; et al. Association of car ownership and physical activity across the spectrum of human development: Modeling the Epidemiologic Transition Study (METS). BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Martinez, J.L.; Calafate, C.T.; Soler, D.; Lemus-Zúñiga, L.G.; Cano, J.C.; Manzoni, P.; Gayraud, T. A Centralized Route-Management Solution for Autonomous Vehicles in Urban Areas. Electronics 2019, 8, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.J.; Hu, K.W.; Ho, H.Y.; Xie, B.Z.; Feng, C.C.; Chuang, H.W. A Distributed Urban Traffic Congestion Prevention Mechanism for Mixed Flow of Human-Driven and Autonomous Electric Vehicles. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2021, 14, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosney Radwan, A.; Ghaney Morsi, A.A. Autonomous vehicles and changing the future of cities: Technical and urban perspectives. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2022, 16, 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Rueda, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Khreis, H.; Frumkin, H. Autonomous Vehicles and Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tympakianaki, A.; Nogues, L.; Casas, J.; Brackstone, M.; Oikonomou, M.G.; Vlahogianni, E.I.; Djukic, T.; Yannis, G. Autonomous Vehicles in Urban Networks: A Simulation-Based Assessment. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2022, 2676, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Becker, H.; Bösch, P.M.; Axhausen, K.W. Autonomous vehicles: The next jump in accessibilities? Res. Transp. Econ. 2017, 62, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Aragó, P.; Temmerman, L.; Vanobberghen, W.; Delaere, S. Encouraging the Sustainable Adoption of Autonomous Vehicles for Public Transport in Belgium: Citizen Acceptance, Business Models, and Policy Aspects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Tapia, M.; Robusté, F. Exploring paradigm shift impacts in urban mobility: Autonomous Vehicles and Smart Cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 38, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppenberger, N.; Richter, M.A. The opportunity of shared autonomous vehicles to improve spatial equity in accessibility and socio-economic developments in European urban areas. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. The Travel Impact of Metro Atlanta through Activity-Based Modeling. In Proceedings of the 15th TRB National Transportation Planning Applications Conference, Atlantic City, NJ, USA, 17–21 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Childress, S.; Nichols, B.; Charlton, B.; Coe, S. Using an activity-based model to explore. In Transportation Research Board 2015; Transportation Research Board, National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rafael, S.; Fernandes, P.; Lopes, D.; Rebelo, M.; Bandeira, J.; Macedo, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Coelho, M.C.; Borrego, C.; Miranda, A.I. How can the built environment affect the impact of autonomous vehicles’ operational behaviour on air quality? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazener, A.; Khreis, H. Transforming Our Cities: Best Practices towards Clean Air and Active Transportation. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T.; Karpinski, E. Implications for Interactions between Micromobility and Autonomous Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Connect. Autom. Veh. 2022, 6, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, G.; Pfeiffer, C.; Baumann, M.; Wörner, R. Individual mobility by shared autonomous electric vehicle fleets: Cost and CO2 comparison with internal combustion engine vehicles in Berlin, Germany. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Madeira, Portugal, 27–29 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadou, K.; Gavanas, N.; Pitsiava-Latinopoulou, M.; Bekiaris, E. Infrastructure Planning for Autonomous Electric Vehicles, Integrating Safety and Sustainability Aspects: A Multi-Criteria Analysis Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, M.; Mutavdžija, M.; Buntak, K. New Paradigm of Sustainable Urban Mobility: Electric and Autonomous Vehicles—A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sya’bana, Y.M.K.; Sanjaya, K.H. The Study of Shared-Autonomous Vehicle Design Concept for Urban Public Transportation in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Sustainable Energy Engineering and Application (ICSEEA), Tangerang, Indonesia, 18–20 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suganuma, N. Towards fully automated driving in urban areas. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Artificial Life and Robotics (ICAROB2020), Oita, Japan, 13–16 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pechinger, M.; Schröer, G.; Bogenberger, K.; Markgraf, C. Cyclist Safety in Urban Automated Driving-Sub-Microscopic HIL Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- May, A.D.; Shepherd, S.; Pfaffenbichler, P.; Emberger, G. The potential impacts of automated cars on urban transport: An exploratory analysis. Transp. Policy 2020, 98, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinderer, H.; Stegmüller, J.; Schmidt, J.; Sommer, J.; Lucke, J. Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles in Suburban Public Transport. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Stuttgart, Germany, 17–20 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzer, M.; Babel, F.; Yan, F.; Zhang, B.; You, F.; Wang, J.; Baumann, M. Designing Communication Strategies of Autonomous Vehicles with Pedestrians: An Intercultural Study. In Proceedings of the AutomotiveUI ’20: 12th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, New York, NY, USA, 21–22 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mordan, T.; Cord, M.; Pérez, P.; Alahi, A. Detecting 32 Pedestrian Attributes for Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 11823–11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Malikopoulos, A.A. Enhanced Mobility with Connectivity and Automation: A Review of Shared Autonomous Vehicle Systems. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2021, 13, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, P.; Silvestri, F. Future mobility and land use scenarios: Impact assessment with an urban case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 41, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrow, L.A.; German, B.J.; Leonard, C.E. Urban air mobility: A comprehensive review and comparative analysis with autonomous and electric ground transportation for informing future research. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 132, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefon, J.-F.; Shariff, A.; Rahwan, I. The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. Science 2016, 352, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kockelman, K.M.; Singh, A. Assessing public opinions of and interest in new vehicle technologies: An Austin perspective. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 67, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Strawderman, L.; Carruth, D.W.; DuBien, J.; Smith, B.; Garrison, T.M. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess pedestrian receptivity toward fully autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 77, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földes, D.; Csiszár, C. Framework for planning the mobility service based on autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2018 Smart City Symposium Prague (SCSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 24–25 May 2018. [Google Scholar]