Abstract

Synchronous interactions from different locations have become a globally accepted modus of interaction since the COVID-19 outbreak. For centuries, professional cadastral survey activities always required an interaction modus whereby surveyors, neighboring landowners, and local officers were present simultaneously. During the systematic adjudication and land registration project in Indonesia, multiple problems in the land information systems emerged, which, up to date, remain unsolved. These include the presence of plots of land without a related title, incorrect demarcations in the field, and the listing of titles without a connection to a land plot. We argue that these problems emerged due to ineffective survey workflows, which draw on inflexible process steps. This research assesses how and how much the use of augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR) technologies can make land registration services more effective and expand collaboration in a synchronous and at distant manner (the so-called same time, different place principle). The tested cadastral survey workflows include the procedure for a first land titling, the one for land subdivision, and the updating and maintenance of the cadastral database. These are common cases that could potentially benefit from integrated uses of augmented and virtual reality applications. Mixed reality technologies using VR glasses are also tested as tools, allowing individuals, surveyors, and government officers to work together synchronously from different places via a web mediation dashboard. The work aims at providing alternatives for safe interactions of field surveyors with decision-making groups in their endeavors to reach fast and effective collaborative decisions on boundaries.

1. Introduction

The disadvantage of the current approach in land registration in Indonesia, encompassing mandatory delimitation, demarcation, and registration of land boundaries, is expensive [1] and difficult to complete due to either emerging ownership disputes or the reluctance of owners to participate in the process [2]. In Indonesia’s land registration projects, both of these behaviors emerge. Although the current registration policy is relatively effective, given the issuance of nearly 60 million new certificates in only 5 years’ time, the administration is also faced with inefficient boundary demarcations, which causes an insufficient number of titles, a surplus of demarcation boundaries [3], and high volumes of unmapped titles. To overcome this quandary, the National Land Office launched community-based land registration projects that aim to optimize the role and effectiveness of para-surveyors (community representatives trained and assigned to conduct spatial and legal data collection) in helping local land offices in executing the land registration systematic project [4]. This project idea originated from the principles of fit-for-purpose (FFP) land administration, which advocate for adapting survey and registration activities to what is possible and required in local contexts [5,6]. As envisioned by [7], an FFP land administration would accommodate affordable modern technologies, and this research provides initial findings in utilizing the technologies for FFP-LA use cases. In this regard, using state-of-the-art technologies for such purposes spearheads smarter land administration, as shown in some previous use cases [8]. Despite these efforts, ownership disputes remain high and landowner participation is still not optimal [9]. As also addressed by [10,11], there are still inefficient registration processes, problems with validation, and major resource constraints, which collectively cause problems in resolving the disputes and resistance of landowners to accept outcomes.

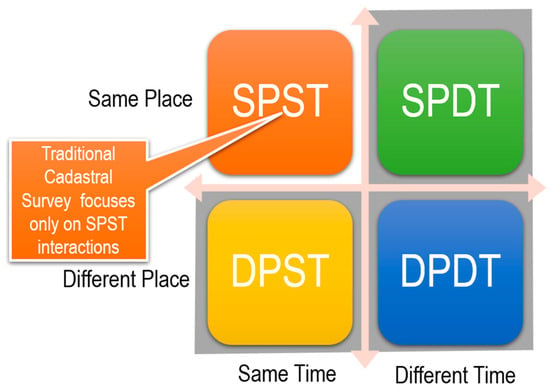

One FFP principle suggests using “aerial imageries rather than field surveys”. Although appealing to practitioners, many village landowners reject this principle, as they feel more secure with agreed visible boundaries. To address this concern, this study tests and verifies if and to what extent a mix of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) could be an effective collaborative survey tool to help surveyors and field workers collaborate with local offices in their endeavors to accelerate the demarcation of disputed or unmapped land boundaries. AR and VR are relatively new technologies that enable the implementation of an old but relevant concept of groupware that classifies a work environment into ‘same-time, same-place’, ‘same-time, different-place’, ‘different-time, same-place’, and ‘different-time, different-place’ settings [12]. Traditional cadastral surveys are commonly performed only in a ‘same-time, same-place’ working environment; if other types of groupware classified in the different quadrants, they are not feasible for the requirements of cadastral surveys [13]. This study presents cases to test how and the extent to which AR and VR can be effective for collaborative cadastral surveys. This research enhances the FFP LA principles using AR and VR devices to leverage a collaborative environment for land registration practices.

The work aims to assess work mechanisms by extending cadastral surveys from same-place and same-time interactions into different-place and same-time interactions in order to accelerate fast and effective collaborative decisions on boundary mapping. The cases of first titling, data maintenance, and quality improvements are used in this work. For these cases, apps for augmented reality users and virtual reality users are developed and tested. The research draws on three case studies of land demarcation in a sample of representative urban wards in the Yogyakarta province. By assessing how and how much land surveyors and policymakers accept the possible new work environment setting for handling land registration and data improvements, we evaluate the potential and conditions of the technology for collective synchronous decisions.

Section 2 describes the theoretical embedding, followed by Section 3 describing the cases and methods to develop the applications. Section 4 presents the results of a mixed-reality environment where surveyors and adjacent landowners work from the field, landowners from their private places, and government surveyors work from the office. It evaluates and assesses how effective and efficient AR/VR technology for supporting boundary demarcation and adjudication increases the quality and completeness of land registration. Additional information, 3D models, and relevant information visualization on land values, zones, and other related restrictions and responsibilities are added to complete a comprehensive boundary survey and mapping. Section 4 discusses the findings, whilst Section 5 draws the conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Land Registration in Indonesia

Indonesia’s land registration system, governed by the 1960 Basic Agrarian Law (BAL) and regulated by government regulation 24/1997, operates on a negative publication system with a positive tendency. This means that the resulting land certificate serves as ultimate evidence of ownership, but it is not an absolute, state-guaranteed title and can be legally challenged by other parties, typically within five years of issuance, if a claimant provides stronger proof. There are two different registration services: first titling for first-time land registration and derivative services that include, among others, subdivision, merging, inheritance transfer, and sell–buy transfer services. First land titling requires mandatory delimitation, demarcation, and registration of land boundaries.

Despite being a government mandate, the completion of cadastral mapping and land titling has historically been slow. To dramatically accelerate progress, The Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency (BPN) launched the Complete Systematic Land Registration Project in 2017 as a national priority. This program significantly boosted the annual products of first-time registration rates from about one million parcels (pre-2017) to nearly 60 million in only five years. As of 2025, there have been over 94 million land titles issued (see [14]). The government heavily promotes these land certificates as a key tool for rights holders to gain socio-economic benefits, such as better access to bank credit.

However, concerns persist regarding the quality and robustness of the hastened process. Local land offices often prioritize the volume of certificate issuance over rigorous data validation. This issue is compounded by the sporadic and incomplete digitalization of crucial land-registration documents, raising questions about the long-term reliability of the titles in enforcing definitive property rights [15].

2.2. Research Rationale

Cadastral surveys are not exclusively restricted to a same-time, same-place setting. For the cases of first-time land registration, solving unmapped certificates, and executing boundary resurveys, group interactions using the same-time, different-place and different-time different-place schemes could be used. For example, in order to expand opportunities for landowners to participate, a digital dashboard enables invited guests to tag their parcel location on the parcel map and to provide notations related to their land’s legal certainty. Such a possibility can be used to replace offline invitations at a given time slot in the village office, which has been proven to be attended by less than 40% of invited names (as implemented in several cities during the quality-improvement project) due to time and distance constraints [13]. Figure 1 draws four quadrants of collaboration mechanics in cadastral surveys and highlights the common tendency in traditional cadastral survey practices. Here, the term collaboration mechanics, which covers coordination and communication in groupware [16], can be adopted for evaluating use of geospatial groupware tools like participatory mapping maps [17]. Table 1 exemplifies use cases where AR/VR can be utilized to realize groupware extensions in the cadastral surveys.

Figure 1.

Four possible quadrants of collaboration mechanics in a cadastral survey (source: [13]).

Table 1.

Examples of collaboration mechanics and scenario-based design in the uses of mixed-reality technologies.

Table 1 modifies the possible groupwork interactions previously presented in [13]. For each of the possible quadrants of collaboration mechanics (except for SPST, i.e., SPDT, DPST, and DPDT), the cadastral survey, with support of mixed-reality technologies, can be used to solve landowner absences in cases of (1) first-time and derivative land registrations and (2) title search and validation in the field. SPST is not included in the table because it represents the conventional cadastral survey method, in which landowners, neighbors, and land officers must meet directly at the same location and time. Therefore, it is not applicable to this research, which focuses on collaboration and the use of mixed reality in land and cadastral surveying. The activity scenario, information scenario, and interaction scenarios were formulated to make user and functional requirements clearer and workable to be used as references to develop AR and VR user interfaces. Such an approach for developing possible groupware interactions is based on the foundation of a scenario-based design methodology [18], which has been implemented earlier in developing Mobile Collaborative AR for archeological prospecting [19].

2.3. Collaborative AR/VR for Cadastral Mapping

Utilizing virtual environments will improve immersive experience and spatial orientation skills [20,21]. Augmented reality and virtual reality are emerging methods for visualizing digital information, including in the geospatial domain [22]. The nature of Augmented Reality, which merges the physical world and digital objects, is an ideal ground for location-based applications and is also helpful for reinforcing spatial skills [23,24]. This technology allows users to interact with virtual objects together in the same physical space or remotely, improving communication and coordination effectiveness [25].

AR superimposes digital content onto the physical world, providing users with enhanced real-time data visualization that facilitates better land administration and spatial planning decision-making. AR-based tools can help surveyors visualize geospatial data in real-time during fieldwork, significantly reducing the need for the manual interpretation of maps and data. AR enables surveyors to overlay cadastral information directly onto the physical landscape, making it easier to verify property boundaries, detect discrepancies, and ensure the accuracy of land records. This real-time visualization can potentially enhance the accuracy and efficiency of land management practices.

As it merges the physical and virtual worlds, AR allows for dynamic interactions between real and digital elements. Although some authors have pinpointed some concerns in the effective uptake and unrealistic expectations of adopting AR/VR in actual organizational processes (e.g., [26,27,28]) emphasizing, for example, that many practitioners still lack the practical experience and sensory skills to deal with these technologies, we posit that, especially in the domains of land administration and urban planning, most practitioners are sufficiently acquainted with various types of 3D and 4D technologies, and therefore mixed reality (MR) can facilitate real-time data analysis and visualization for such practitioners.

In this regard, augmented reality (AR) applications for formal, legally recognized cadastral surveys remain an unaddressed research area globally, including in Indonesia. The majority of AR/VR/MR research in the built environment, conversely, is centered on leveraging AR and VR technology with Building Information Modeling (BIM) data for efficient building projects and designs (see, e.g., [29]). El-Shimy et al. [30] explored the use of MR in urban planning simulations, where MR allows planners to interact with 3D digital models overlaid with physical environments. This facilitates better collaboration and decision-making by providing stakeholders with a comprehensive view of the spatial data in real-world contexts. Chang et al. [31] introduced an efficient VR-AR communication method using virtual replicas in extended reality (XR) remote collaboration, which emphasizes enhancing communication and collaboration efficiency through the use of virtual replicas in XR environments. We assume that this technology can connect surveyors, landowners, and land officers in determining land boundaries. MR or collaborative AR-VR technologies can potentially improve cadastral surveys by integrating geospatial data directly into the field. Their research motivates the idea that implementing MR reduces the time needed for boundary marking by allowing surveyors to visualize and manipulate cadastral data directly within the physical environment, enhancing accuracy and efficiency.

Despite The Ministry of Land Affairs and Spatial Planning’s (ATR/BPN)’s successful achievements in securing land rights by the systematic registration project, land tenure remains insecure for rural and customary communities, as they are often not properly or sufficiently involved in the registration processes. Hence, bottom-up, participatory interactions are useful and lead to more effective registration acceptance if and when collaborative communication can be facilitated through visual 3D representation of the environment [32,33]. This research explores the Unity3D (2022.3.0f1) game engine for creating multi-platform 3D map visualizations (VR and AR apps) from mixed sources of 3D city models and cadastral maps. This research connects the apps built from the game engine to build collaborative communication with land office personnel, especially for implementing first titling, maintenance processes, and quality improvement in land registration services. This paper only focuses on the DPST quadrant type from Table 1, at which ‘same-time, different-places’ using AR and VR can be used as an alternative to the existing workflows.

3. Materials and Methods

This study’s test and validation methods are scenario development and comparative analysis. Scenario development addresses how certain workflows could be changed (ideally, improved) and the requirements for the changes. Comparative analysis tests and measures the results of the changes and validates if these results are sufficiently effective in a qualitative (rather than a quantitative) manner. Although typically, the quality of a cadastral surveys is measured with quantitative statistical methods, we opted for a qualitative approach because we aimed to explore if and how AR/VR could be incorporated as a tool to enhance organizational (workflow) efficiency and effectiveness rather than to investigate the positional accuracy outcome when incorporating AR/VR in the process. The subsequent subsections elaborate and clarify how we used the analytical methods.

3.1. Scenario Test: Existing vs. Proposed Approaches

This research assumes that geospatial collaboration with AR/VR, especially for land registration services, enables better synchronous communication and coordination among main actors and can thus help surveyors measure land parcels in the field while conducting blended interactions with officers and landowners as well as with village leaders from different places to derive a solution for a contested delimitation.

The technological capacities of collaboration through mixed reality are more mature than they were one to two decades ago. They are gradually becoming a realistic and effective type of groupware for generating and simulating alternatives [34]. Mixed reality, ranging from AR to VR, has become a more commonplace tool for professionals to collaborate with. Augmented reality or virtual reality (AR/VR) devices on top of a game engine are frontiers in building construction [35,36], monitoring applications [37], urban planning [38], urban development [39], and archeology reconstruction [40].

The appropriateness of the two technologies is tested for three workflow environments:

- 1st time land registration/titling—testing if and how AR/VR can enhance the effectiveness of the workflow and quality of the output when landowners cannot attend the meeting with surveyors/adjudicators.

- Data transactions/updates—subdivisions, merging, and transactions—testing if and how AR/VR can enhance the effectiveness of the workflow and quality of the spatial and legal output (use of AR/VR compared to using web services by legal officers) when landowners cannot attend the meeting with surveyors/adjudicators.

- Quality improvement of cadastral data—testing if and how AR/VR can improve title search and discovery by community leaders and neighbors based on the last landowners’ names and neighboring parcels, typically performed in a meeting facilitated by land officers and surveyors to plot the remaining unmapped titles in a village or urban ward (see [15]).

Validation of the testing criteria includes 4 moments/points in the workflow:

- Preparation time (input)—becoming acquainted with local situation and environment.

- Linkage between spatial and textual data is effectively performed (throughput).

- Spatial and textual quality (output).

- No complaints/user satisfaction (outcome).

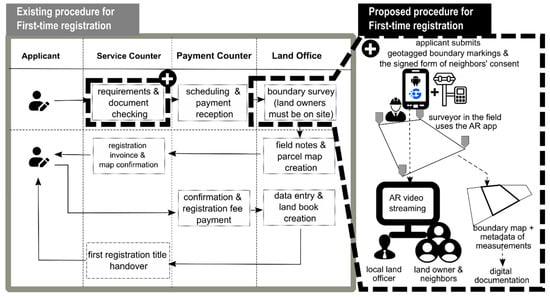

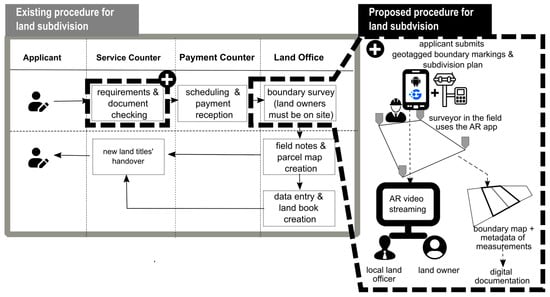

The comparison between the existing and proposed workflows is visually summarized in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The existing workflows refer to the regulation made by the Head of the National Land Agency Regulation in 2010 (Regulation No. 1 of 2010) on Land Service Standards and Regulations. The regulation specifies first-time titling and land subdivision as two out of the many available land registration services. Land subdivision is among the services of land data maintenance.

Figure 2.

First-titling registration scenario using Geoclarity: the existing vs. proposed procedure (black dashed box).

Figure 3.

Land subdivision scenario using Geoclarity: the existing and proposed procedure (black dashed box).

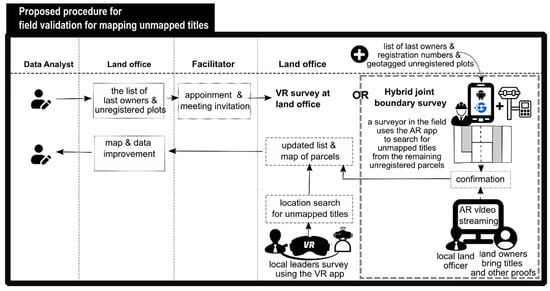

Figure 4.

Unmapped land parcel data quality improvement scenario using Geoclarity with VR survey at the land office or hybrid survey (AR and video communication) via the dashboard.

The proposed method for mapping unmapped titles is motivated by challenges in accelerating the recording and inclusion of unmapped titles. As observed during the execution of Indonesia’s land registration projects, there is still a high number of land titles issued which rely on heterogeneous data qualities, including the accuracy of boundary descriptions, the existence of unmapped land parcels, double issuance of certificates relating to the same parcel, and incomplete or inaccurate registration of person data. This scenario focuses on the workflow which checks and includes unmapped land parcels in the land records, also known as K4. To execute this workflow flow, local leaders are guided by surveyors or land officers (either in the field or at the office) to inspect the virtual environment of an area of interest, with the purpose of verifying and correcting the existing land records.

Figure 2 presents the existing and proposed alternative procedure if physical attendance of a landowner or applicant is not possible or does not occur. Similarly, Figure 3 presents the existing and alternative workflow for a registration update process in the case of a subdivision of land plots. Figure 2 and Figure 3 involve an applicant, land officers (who handle the service counter and payment counter), a surveyor, a landowner, and neighbors. Figure 4 presents the proposed procedure for solving unmapped titles. This scenario involves three actors: the analyst, surveyors (can also be as facilitators), the community/village head or leaders, and the land officer.

As seen in Figure 2, the existing sporadic survey is conducted in two phases. The first phase is known as sporadic adjudication and the cadastral survey. The second part is the follow-up after the cadastral survey, which results in a parcel map. Once the parcel map is produced, the applicant can then apply for the right registration until the land title is verified and signed by the head of the land office. The developed first-titling scenario here only focuses on the first phase (i.e., cadastral survey processing), which currently requires the landowners (or at their least legal representatives on their behalf) to be in place when the survey is performed. In the proposed scenario (represented as black dashed boxes), the applicant is requested to include the geotagged data of their boundary markings and the neighbors’ consent. Based on the appointment schedule created by the land office, a surveyor visits the land parcel. The AR app can help surveyors orientate the parcel to be surveyed and to extract relevant information related to spatial plan and tax of the parcel in order to confirm the parcel to landowners who might join remotely. The surveyor can switch from an AR camera to the corresponding overlaid 3D building outlines and parcel data boundaries, where the AR survey will take place. Landowners and neighbors can see the AR screen using real-time video streaming. This same-time, different-place interaction is facilitated and recorded by the land officer mediating the interaction. Surveyors fill out the field survey form to complete the survey. The result is submitted to the cadastral database and verified by land officers for further processing (second phase of first-time registration). Landowners can track the process the land office runs (including public announcement) until the title is published and covered.

As seen in Figure 3, initially, a right-holder (as an applicant) requests changes to their land boundaries (i.e., subdivision). This application prompts BPN surveyors to conduct field surveys and collect updated geospatial data, given that the application documents are submitted and the payment is completed. Some required documents include the signed neighbors’ consent in regard to parcel boundaries and the proposed split line and modification of the parcel. In the existing procedure, the physical attendance of the landowner to join the survey is required. Otherwise, a landowner’s representative or someone on the landowner’s behalf must be at the location when the survey is conducted. The proposed procedure encourages applicants to include geotagged points of existing and proposed splitting point boundaries in their application form. Landowners and neighbors can join the surveyor’s work in dividing the parcel virtually using real-time video streaming. During the process, the proposed splitting lines are overlaid onto the AR camera and shared to landowners via video streaming. This process is assumed to increase the effectiveness with which surveyors can execute a division in the field because it allows them to (virtually) see the lines directly in the system instead of having to mark a virtual line in the field. Once the parcel’s modification is confirmed, the cadastral survey can be carried out with the GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) instrument. Further, the data are verified by the BPN land office, and the progress can be tracked until the new land certificate titles of the updated parcel are published and delivered.

As seen in Figure 4, the process begins with a data analyst identifying issues and making a list of the unmapped land parcels, followed by an activity where land officers or surveyors who act as facilitators hold a meeting with community leaders to share a list of the unmapped land parcels and names of the last owners. The community leader analyses the list based on the owner’s name and address. Next, via a collaborative meeting on the dashboard or teleconference app, land officers (can also be surveyors) guide community leaders to find the location of unmapped land parcels using a VR app. They explore the virtual environment and suggest the actual location of the unmapped title onto the suggested land parcel location. The collaboration process is carried out through digital interaction and communication between land officers and local leaders. In this workflow, local leaders can interact with virtual objects—such as buildings, 3D models, and land parcels—either from a first-person perspective or a bird’s-eye view to identify and mark blank areas (those without red polygon lines) that represent unregistered parcel boundaries. At the current stage, the proposed workflow enables users to mark locations digitally. However, in future developments, these marked points will be uploaded to a GIS dashboard for accurate geodetic measurements using surveying instruments. The roles of each participant in this scenario mirror those in the traditional SPST domain, where local leaders indicate boundary positions and land officers record and measure them. Traditionally, this process requires both parties to meet physically in the same place. With the proposed technology, local leaders and land officers can instead collaborate within a shared virtual environment anytime and from anywhere. Their participation occurs simultaneously through digital platforms, enhancing flexibility and accessibility. In cases of conflict or disagreement, initial resolution can be achieved through digital communication, which may later be followed by a direct meeting if further clarification is needed. Alternatively, a similar approach of video streaming on the AR app screen is performed by land surveyors when visiting unregistered parcels, indicated as unplotted titles. Web dashboard technology can be utilized to enable the integration of video teleconferencing with the video streaming of the AR camera with a group video call into an integrated screen. This can also be seen as a mediating tool interconnecting landowners, surveyors, and neighbors at the same time from different locations. When the location search of unmapped titles is successful, the data and map are updated.

3.2. Development of a Collaborative AR, VR, and Web Mediation Dashboard

In order to develop a validation test environment, named Geoclarity—Geocollaboration Tools for Land Registration Survey with Augmented and Virtual Reality—three applications are developed: (1) an AR app that superimposes an AR camera with 2D parcel boundaries on 3D building outlines and attributes; (2) a VR app that presents a 3D city model which contains 2D cadastral boundaries and attributes; and (3) a mediation dashboard, integrating field surveys and coordination meetings in a live stream. The mediation dashboard is intended to mediate boundary delimitation and to allow for the confirmation of relevant parties, landowners, officers in the land office, and surveyors, in the field in real time using livestream coordination. All these three are primary tools to validate the appropriateness of the three new proposed workflows defined in Section 2.3. AR and VR are developed using game engine software, i.e., Unity. Unity has been identified as one of the potential geovisualization platforms, given the nature of interactivity and partial support for geospatial data [41].

An internet connection is necessary to access cadastral databases at the current location. The data are provided in GeoJSON format, which facilitates lightweight processing on local devices. Additionally, the internet connection allows for access to the Google ARCore Geospatial API, which updates your location and scans the surrounding area. The Geospatial API utilizes Google’s visual positioning system (VPS) to improve location accuracy. The VPS employs camera input and computer vision to match your surroundings with a vast database of geotagged images, primarily sourced from Google Street View. This technology enables the system to determine your device’s precise position and orientation, even in areas where GPS signals are weak or obstructed.

The AR app is made possible by the utilization of ‘cloud anchors’, which are used to identify features (e.g., cadastral boundaries and spatial plan polygons accessed from the server’s databases) and to represent those features overlaid on the AR camera. The requirements and software components for developing an AR application with Unity SDK are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Application requirements for AR app and corresponding software components.

In addition to the AR app, a VR app is developed fully with Unity SDK and utilizes the same geospatial databases used by the AR app. Table 3 specifies the software components used in creating the VR app.

Table 3.

Application requirements for VR app and corresponding software components.

This third application is a collaborative dashboard monitor, seen as a mediation dashboard, showing AR live streaming from the field and teleconferencing cameras of related parties. This monitor is to help surveyors inspect and measure land parcels in the field while obtaining confirmation or guidance from officers or landowners located in different places to derive an agreeable contradictory boundary determination. The web mediation dashboard is designed to support field and office or home coordination involving stakeholders and can be used to support data updates (i.e., land subdivision) and quality improvements (i.e., matching field parcels against unmapped title data). Table 4 provides information related to the software components required for developing a web mediation dashboard.

Table 4.

Application requirements for web mediation dashboard.

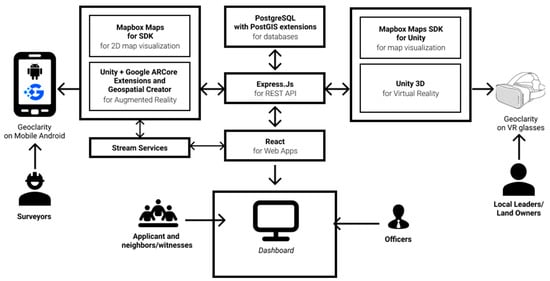

Figure 5 presents the architectural design of the Geoclarity framework and their software components.

Figure 5.

Architecture of technical implementation of Geoclarity and its software components.

Property data are generated into two different data formats. Two-dimensional geometries of land parcels and spatial polygons were converted into GeoJSON format and stored in spatial databases (i.e., PostGIS). Meanwhile, 3D buildings were created directly in Unity as prefabs and imported as game objects in the Unity platform. Mapbox Maps SDK for Unity was used to georeference game objects.

The newest cadastral map and its attributes for three urban wards (i.e., Terban, Kotabaru, and Cokrodiningratan) in Yogyakarta City are provided by the local land office. These three wards were chosen for their data completeness. The tax property data were provided by the asset and financial management agency, while the spatial plan map was provided by the Spatial and Land Agency of Yogyakarta City. Three-dimensional models of these three wards were developed by the researchers at UGM and their partners.

3.3. Focused Usability Testing of Geoclarity Uses

In order to validate the implementation of all use cases in the real world, enabling the same-time and different-place interactions in the cadastral survey, a focus group of usability testing was performed. The focus group involved government and private surveyors working in the study area and surroundings. More specifically, the usability testing was attended by two lead/senior surveyors, four surveyors working at the local land offices, and one private surveyor, all familiar with the study area. Focus groups are among the data collection techniques implemented to support user experience research, including evaluating a serious application for specialized users in usability testing [42,43]. In this case, the focus group is selected to gather effective feedback for the use of new tools with new technology for cadastral surveyors with a strong background in surveying and experiencing various technical and social challenges when performing the surveying task.

As the focus was to validate the use cases and developed applications, the focus group discussion (FGD) was first divided into two sessions: the first session is the presentation of proposed use cases (against their standard/familiar procedures) and introduction to the apps to support real-world’s tasks in conducting boundary search and delimitation on the location for (a) first-time registration, (b) parcel subdivision and field validation before transactions (data updates), and (c) virtual field visit to plot unmapped titles. The second session is to receive the participants’ feedback about the validity of the workflow and their experiences in working with AR and VR apps.

The feedback and focused comments were collected to answer some critical questions relevant to the design of applications:

- Is preparation time (input) enough for becoming acquainted with the local situation and environment? Question 1.

- Is the spatial and textual data linkage effectively performed (throughput)? Question 2.

- Is spatial and textual quality fit for purposes (output)? Question 3.

- Do users have no complaints and express satisfaction (outcome)? Question 4.

- Are use cases relevant to their daily tasks? Question 5.

These questions were closely related to issues of capacity, specifically regarding the use and understanding of new equipment and processes. Additionally, concerns were raised about whether the technology would pose problems for landowners and whether the system could be replicated. The capacity issues pertained to input and throughput (questions 1 and 2). Furthermore, it was important to determine whether the technology posed challenges for landowners and whether the entire approach could be replicated at the local level. These aspects directly relate to questions of output, outcomes, and the relevance of use cases (questions 3, 4, and 5). During the discussion session, participants were encouraged to express their projections and concerns regarding potential challenges to adopting the system for practical work.

4. Results

4.1. Geoclarity Geo-Collaboration Tools for Land Registration Survey with Augmented and Virtual Reality

Augmented Reality (AR) has emerged as a transformative technology in the development of Geoclarity collaboration tools. By overlaying digital information onto the physical world, AR enhances the precision and efficiency of geospatial data collection and visualization. In the context of land registration, AR enables surveyors to demarcate boundaries and identify discrepancies directly in the field accurately. This technology also facilitates real-time collaboration between surveyors and landowners, regardless of their physical location (video conference). Surveyors are provided with the capability to digitally complete survey sketches with an AR application. Along with determining field boundaries, surveyors can contribute to quality improvement by reporting data errors based on field confirmation results.

VR technology can be utilized to present simulations for the maintenance of spatial and textual land data, such as in the process of land parcel division and dispute mediation. Additionally, the virtual environment can be used to explore surrounding areas, regardless of visiting the site in person. Community leaders can indicate unmapped land parcels (K4) in the virtual world based on their location familiarity and community members living in their area.

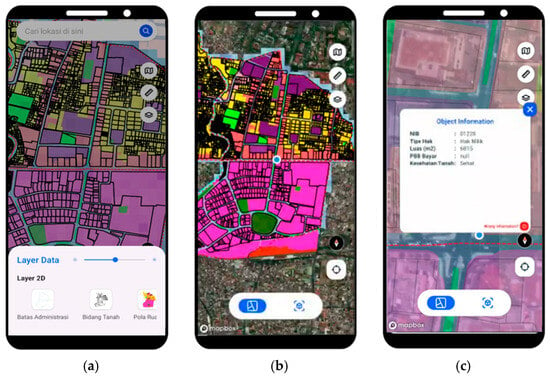

4.1.1. AR Survey

The results of the AR app with Geoclarity collaboration tools can be seen in Figure 6. The app has abilities to help surveyors to open and geolocate 2D layers of land parcels or land registration maps and conduct detailed spatial plan zonation as a spatial layer with transparency on top of the photo map (Figure 7). Surveyors are able to switch to the AR camera. By activating the AR camera and targeting the AR camera to the fronts of objects, the app provides assistance to surveyors to superimpose the outlines of parcel boundaries on top of the physical objects seen by the camera onto the app screen (Figure 6). Additional tools include displaying attributes, measuring areas and distances via AR survey, and providing field notes and reports for each parcel surveyed.

Figure 6.

The display of AR mode: (a) AR app can switch to AR mode, (b) parcel boundaries can be seen superimposed over the physical property objects, (c) distance measurements can be performed by targeting points on the targeted objects.

Figure 7.

The display of 2D map view: (a) Land parcel boundaries can be displayed as 2D layers on the AR app, (b) land parcel boundary layers can be displayed with orthophoto, and (c) parcel information can be previewed by interactively clicking on the targeted land parcel.

The AR survey provides a comprehensive spatial dimension for cadastral surveying, enabling land officers to conduct surveys directly using a smartphone. Through this approach, various tasks—such as distance and area measurements, as well as overlaying real-world buildings with digital land parcel boundaries—can be efficiently performed in the field. This method introduces a more practical and accessible alternative to conventional surveys, as it allows real-time visualization and interaction with cadastral data. However, achieving high precision in AR-based surveys remains challenging, particularly in narrow corridors, densely built-up areas, and small streets where satellite signals or camera alignment may be limited. The accuracy and quality of the overlay between land parcels and real-world structures also depends heavily on the performance of the mobile device’s positioning sensors, including GPS, IMU, and the camera’s calibration quality.

4.1.2. VR Survey

Figure 8 illustrates the display of buildings with level of detail three (LOD3) and the corresponding complete attribute. The LOD3 building models were manually generated from LiDAR and orthophoto data acquired using high-definition UAV LiDAR sensors. The detailed technical procedures for the building modeling process are described in our previous study [44], which supports this research. The resulting models were then visualized in a VR environment to enable an interactive land surveying process. VR also has the ability to allow users to measure land parcel measurement outcomes and to explore building attributes related to their ownership, use, tax, and permit statuses. When a land parcel is clicked, it can display information to clarify details for the user or landowner. Figure 8 shows the development of the VR app. The app has the ability to allow users to perform a parcel search by its identifier. In addition to those functionalities, the VR app can also help users to display attributes and to look for the nearest places of interest, and to conduct measurements.

Figure 8.

VR survey can be performed using VR glasses where landowners and local leaders can search land parcels based upon their parcel identity, looking at their attributes, measuring distances, and exploring 3D city buildings and spatial plans: (a) the display shown in the glasses to navigate, browse, identify attributes, search, and measure property objects; (b) a closeup aerial view land of parcel boundaries of an area of interest before clicking on a parcel and revealing its attributes.

With the spatial data obtained, land officers can perform queries and measurements within the digital environment, including retrieving parcel information directly. The proposed technology is designed to overcome the limitations of the SPST domain, which traditionally requires land officers, landowners, and neighboring landholders to meet physically to agree on parcel boundaries. Through the use of VR and AR surveys, this process becomes collaborative—allowing landowners and neighbors to jointly mark parcel boundaries, which are then validated by land officers. The application facilitates effective collaboration among stakeholders, as each participant can visualize the real world blended with digital cadastral data (mixed reality) to accurately identify and mark boundary positions.

Once marked, the workflow follows a similar concept to mobile GIS applications such as ODK or QField, where boundary data can be uploaded to a central server and visualized in a GIS dashboard. This enables land officers or surveyors to perform accurate GNSS-based positioning without the need for simultaneous physical meetings with landowners and neighbors. Moreover, GNSS measurements can be performed directly while the AR application runs in parallel, enabling asynchronous participation—landowners or neighbors can identify boundaries via AR even when they are not physically present. For example, in first-time titling, boundaries can be initially delineated using AR, and once consensus is reached among landowners and neighbors, precise geodetic measurements are carried out using GNSS. A similar process applies to land subdivision surveys. In the case of mapping unmapped titles, VR technology provides a digital representation that allows land officers, landowners, and neighbors to collaboratively identify and mark boundaries remotely. After final confirmation, GNSS measurements are conducted to ensure positional accuracy.

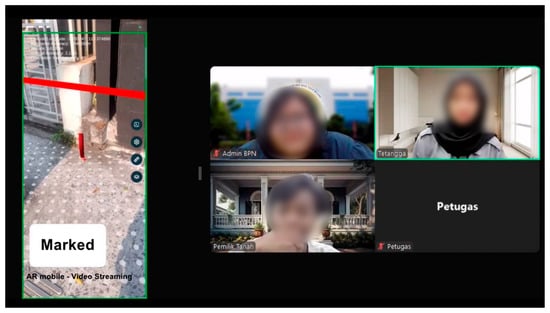

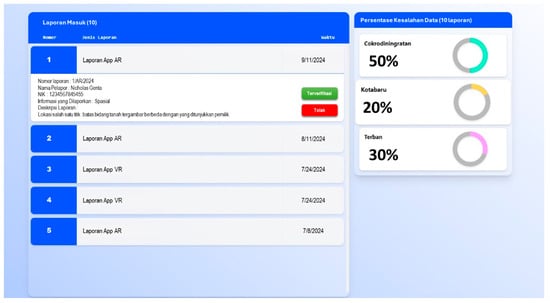

4.1.3. Dashboard

There are several processes in land administration services that need to be conducted on a different platform to ensure accessibility from anywhere without the use of specialized devices. This platform is a mediation dashboard, which can present an AR camera, a Video Conference Camera, and a 3D virtual environment (VR view) if necessary. Such video conference dashboards can be replaced using other familiar teleconference software (e.g., Zoom, Google Meet, or Microsoft Teams) (Figure 9). Another window is field report management, which enables the inspection and editing of field reports submitted through AR/VR forms. This field report management handles field submissions performed by surveyors, landowners, and notaries related to errata or missing information about their land parcel of interest (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Real-time video streaming between surveyor (AR app), landowners, neighbors, and land officers via a web mediation dashboard.

Figure 10.

Dashboard pages that handle field data submissions and requests for map improvements.

4.2. Results of Scenarios Testing

There are multiple actors and a multitude of activities that play roles in the business process of land registration services. For instance, according to the existing regulation (No. 1/2010), in total there can be more than 21 actors and 59 physical/digital documents involved within the 72 existing land registration services. This research is limited only to three scenarios of land registration services, namely, first-time titling, maintenance of land registration data (i.e., land subdivision), and one scenario of a quality improvement task in land registration. For these three scenarios, there can be at least seven actors involved: government surveyors from the land agency office, local land officers, private surveyors, landowners, neighbors (in case of first-time titling and land subdivision), and also the attendance of the village head or community representatives in the case of registration data improvements.

The scenarios testing new collaboration mechanics in first-time titling, land subdivision, and quality improvements are presented in Table 5, Table 6, and Table 7, respectively. Those three processes represent the key stages of land administration, which are fundamental steps in land and cadastral surveying. For each process, scenario testing was conducted to demonstrate, evaluate, and validate the capability of Geoclarity as a new collaborative mechanism for land and cadastral surveys. Each of the tables present the proposed steps, their check results, and the corresponding feedback from participants.

Table 5.

The results of the validation test for scenario one: first-titling survey.

Table 6.

The results of the validation test for scenario two: land subdivision survey.

Table 7.

The results of validation test for scenario three: mapping unmapped titles.

Based on the evaluation results and additional feedback from officials, government surveyors, and private surveyors, all participants agreed that the proposed workflow and technology are relevant to the daily practices of land and cadastral surveying. The feedback obtained from the scenario testing indicated a positive response from stakeholders toward adopting a new form of collaborative technology. The proposed system and workflow aim to address several challenges in land surveying and registration—particularly in first-time titling, land subdivision, and quality improvement. By implementing this approach, the mandatory requirement for the SPST condition can be reduced, allowing land officers, landowners, and neighboring landholders to interact asynchronously. This issue can be effectively mitigated through the proposed technology, which provides collaborative tools and mechanisms for conducting land surveys more efficiently.

5. Discussion

In the context of first-time registration and plot subdivision/merging practices in Indonesia, the current procedure that requires same-time and same-place interactions for all cadastral surveys related to land registration services has been in place since 1997, known as Agrarian Ministry Regulation No. 3/97. Ministry Regulation No. 16 from 2021 allows the use of AR/VR and internet collaboration technologies for boundary determination (Article 19c of the Ministry Regulation). Despite this development, there are currently no formal technical guidelines available for surveyors to implement these techniques. Therefore, there is a clear need for the creation of comprehensive technical guidelines.

Based on the FGD and focused usability testing, senior government surveyors appreciated the scenario and its implementation with the developed AR and VR technology, not only because regulation has been possible, but also because of its potential to solve eminent problems in relation to boundary demarcation and survey for land registration. The FGD involved both government and private surveyors, and the detailed questions and feedback are explained in Section 3. Based on the results of scenario testing, most surveyors argue that the case of the plot subdivision is very appropriate to be strengthened with an AR survey by the surveyor in the field and to be confirmed by landowners remotely in case they cannot attend the survey physically. One participant also argued that the case of a sell–buy transaction can also be supported by such an AR survey, as parcel boundaries might look different or unseen in the field compared to what is printed in the certificate. The coordination and communication via teleconference (supporting collaboration mechanics in the ‘same-time, different-place’ cadastral survey) are seen as useful by participants to support the video streaming of the AR survey. Even one participant argued that the recording of the survey’s collaboration should be used as part of metadata and digital documents for the sake of the clarity of data maintenance (future division, merging, and buy–sell) in the future. The web mediation dashboard is also seen as a potentially necessary tool to be installed in each land office in the country. Specifically, this web mediation dashboard accommodates location searches in looking for unmapped titles. Almost all land offices should now provide a meeting room to facilitate mediation and complaints related to boundary disputes and claims.

Potential uses of the system beyond the three use cases are possible. As mentioned by a participant from a district office, the tool could also be used to support land-consolidation survey activities. This participant shared his past experience with a land-consolidation survey involving landowners who inherited a large parcel of land, but it was conducted without the attendance of future landowners. This created issues when the final certificate was printed.

Additionally, a senior surveyor suggested that the design for land subdivision, specifically for land consolidation, could be overlaid onto an augmented reality (AR) camera. This design could then be shared with future landowners during online meetings. This type of interaction, referred to as asymmetric collaboration [34], involves the surveyor sharing the physical environment using the AR app while their remote collaborators or stakeholders use different interfaces, such as a coordinated teleconference screen and the VR app. Almost all participants viewed this method as a significant advancement in enhancing the quality of land surveys.

With increased maturity of AR and VR technology and use scenarios, such typical asymmetric remote collaboration could also accommodate transitional interfaces from AR to VR or vice versa [34], and from non-immersive display devices into fully immersive display devices [34,45].

Criticism for the use of mobile AR is based on its reliability to help navigate and look for parcels in the tight alleys easily found in the city. The location precision can be challenging in cases where the city corridor is very narrow. The precision and accuracy values depend on the quality of the positioning sensors of the mobile phone; hence, the minimum requirements for working with the AR apps should be determined. In cases where the splitting boundary lines are unseen or covered by existing buildings (e.g., divided parcels are within houses or crossing building rooms), the AR survey can be useful for comprehending the splitting area. Despite its interactivity potential and ease of use of the application, a senior surveyor noted feeling a headache and became dizzy as the fly mode in the VR app moved too fast.

Design for other collaborations in different quadrants (different-places and different-times via the 3D annotation forum; same-place and different-time with tabletop kiosk) could be realized depending on which level of engagement for land registration services the users express their interest.

Some of the limitations include the dependency on internet access. This may indeed limit the direct use or access of models stored online and thus the efficiency and effectiveness of opting for AR/VR methods. This dependency can, however, be addressed with a VPS (visual positioning system) or a QR code of objects, whereby the landscape can be reproduced locally without any access to the internet.

This system is primarily intended for use in urban areas. It is designed to function in the field even with unstable or weak internet connections. An internet connection is necessary to load cadastral data into the GeoJSON format, which allows for relatively lightweight processing on local devices. Additionally, the internet connection is used to access the Google ARCore Geospatial API for updating user locations and scanning surrounding areas. A weak or unstable internet connection can hinder optimal location synchronization, although data inputs can still be performed. When the internet connection is restored, the app will automatically upload the entries and form data in the server.

However, when online collaboration via a dashboard in the local office is required to facilitate interactions among the land officer, landowner, and surveyor, a strong internet connection is essential for all parties involved. There remains a digital divide between urban and rural areas in the country; approximately 20% of the population, or about 5000 villages in remote areas, still lack internet connectivity (as reported here: https://cgd.ibc-institute.id/building-a-connected-indonesia-through-digital-infrastructure-and-connectivity/ (accessed on 19 November 2025)). Consequently, this system cannot be utilized in rural and remote locations with no internet connections.

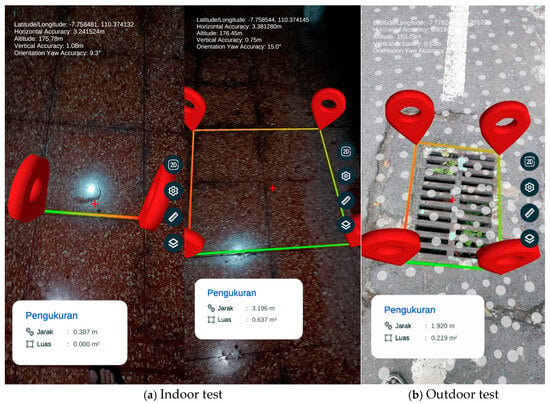

The app offers tools for measuring distance (from a starting point to an endpoint) and area (using connected points to form an area). The results are displayed in the measurement box (see Figure 11). Surveyors can measure distances by aiming at a point seen in the screen and placing the point icon at both the starting and ending segments (or at the vertices of segments in the case of a rectangle, viewed from the camera screen). Field tests have shown that these measurements yield positive results, with a maximum distortion of only 0 to 5 centimeters. In addition to distance and area measurements, the app displays location and accuracy information in the top left corner of the screen. This includes position coordinates, absolute positioning accuracy, vertical accuracy based on global elevation, and orientation accuracy. As a result, with the current capabilities of mobile point positioning, this tool is deemed suitable for measuring distances between two boundary points in the field and is ready for implementation and adoption by surveyors.

Figure 11.

The tools on the right side of the screen enable surveyors to switch from AR camera to 2D map, manage settings, use a ruler to measure distances, and load thematic layers. The measurement box (‘Pengukuran’) shows the resulting distance (‘Jarak’) and area (‘Luas’). The position coordinates, absolute positioning accuracy, vertical accuracy based on global elevation, and orientation accuracy are also displayed in the top left corner of the screen: (a) Indoor measurement tests. (b) An outdoor measurement test, as performed in [46].

Currently, boundary surveys still depend on traditional measuring tools and geodetic positioning devices for creating survey documentation. This paper focuses solely on comparing the accuracy of distance measurements, without addressing other positioning techniques. The quality of positioning in augmented reality (AR) surveys has been identified as a challenge that requires further investigation.

Regarding the acceptance of survey activities performed with the tool, the submitted survey documentation—consisting of screen captures or screen recordings from the survey—can serve as additional sources of evidence in the field. This documentation can be verified and linked to the survey dashboard, as shown in Figure 10. Once all survey requirements are met, the survey’s activities can be individually verified and accepted. Using the records from the dashboard alongside field survey sources, offices can further process the registration of new and subdivided parcels, utilizing this information as official documentation.

Calculating the exact cost improvement when using AR/VR as compared to conventional methods for first registration and subdivision is not obvious. Nevertheless, we would argue that while conventional methods require from two to three field surveyors to travel to the area, the AR/VR approach could be executed with just one surveyor on site and one information operator in the main office. It would thus reduce the travel and field costs. Additionally, there is a time reduction for registration and division, but this will also depend on the complexity of the object and/or landscape. Using the traditional approach to land surveying in Indonesia often requires a lengthy and complex process. Extensive administrative and field procedures are needed before a land parcel can be certified. In conventional surveys, the “same-time, same-place” condition is mandatory—landowners, neighboring landholders, and land officers must meet directly to agree on land boundaries, which can take considerable time. For example, in a first-time titling process, landowners are required to visit the land office, complete several administrative procedures, and schedule a joint meeting involving the landowners, land officers, land surveyors, and neighboring landholders to reach an agreement on boundary lines. This process typically takes between one and three months for a single parcel under the traditional system. Although the proposed technology has not yet been fully tested or implemented in actual office operations—since this study introduces it conceptually and through scenario testing—it has the potential to significantly shorten the process to only one to two weeks. This improvement is possible because the “same-time, same-place” requirement is eliminated: land surveyors and neighboring landholders can review and confirm boundaries asynchronously through VR and AR environments, while administrative procedures can be completed online through the dashboard and video conferences. This requires, therefore, further field tests, measuring and comparing the time and cost of AR/VR-supported surveys for a variety of such field characteristics.

Studying how using AR/VR extensively in daily work processes would have any physical side effects (such as nausea, dizziness, and eyestrain) was not part of this study, but this may become an issue as well when regarding the consistency in the quality of the data. This may require further tests.

6. Conclusions

This study tested for three work land administration-related work processes in Indonesia, i.e., first titling, data maintenance of land subdivision, quality improvement, and if and how utilizing AR and VR technology could improve the efficiency and effectiveness. The tests were carried out by and with land surveyors, and the assumption was the AV/VR technology would allow for synchronous work at different locations, and by different actors, and would thus drastically improve the speed and the quality of outcome of the processes.

The evaluation results demonstrate that the field preparation time for each of the work processes can be significantly reduced when using a pragmatic approach. The quality improvement of the work with the use of AR/VR, automatically linking the spatial and textual data, also proves to be effective as compared to conventional processes, as they currently still rely on procedural splits spatial and textual data in many local land offices. Hence, the new ‘fit’ of spatial and textual data derives a ‘fit-for-purpose’ quality, which proves to be more acceptable for participants and beneficiaries of the work processes given their clear expression of satisfaction and absence of complaints. Last but not least, all use cases were confirmed (by respondents) to be relevant to their daily tasks. The experiments conducted for each Geoclarity use scenario highlight the advantages and superiority of the proposed application and system for cadastral surveying and land registration compared to conventional, less efficient methods. The main finding indicates that the proposed application functions effectively as a geo-collaborative tool for land registration.

The respondents’ feedback on the presented alternatives of cadastral surveys were also positive, given that the field surveyors and decision-making group could reach effective decisions on boundary mapping, and more effectively solve the practical field and location challenges which surveyors normally face. From the focus group session, it became evident that using the AR apps and AR live streaming is especially beneficial for the case of land subdivision surveys, but it also enhances first-titling surveys. Despite the observed benefits, efficiency, and effectiveness, there is still a need for further tests and research. This includes a more quantitative assessment of the derived positional accuracy when using AR/VR, assessing the physical work effects when extensively relying on AR/VR for field surveyors, and assessing the feasibility of adopting the technologies formally and institutionally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.; methodology, T.A. and W.T.d.V.; software, A.N.P. and C.W.; validation, N.G.S. and F.A.; formal analysis and investigation, T.A.; investigation, W.T.d.V. and T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, W.T.d.V., T.A. and C.W.; visualization, T.A., C.W., A.N.P., F.A. and N.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Capstone Grant 2024 and also by Aubrey Barker Fund/FIG Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) through the Capstone Grant 2024. The authors are also grateful for Benny Emor from Geosquare for his collaboration during the research’s implementation. We would like to thank Miranty Sulistyowati for her help in preparing use cases and coordinating the user meeting, and also to Ali Surojaya for his help with earlier research graphics. We also would like to thank the Head of Surveys from the Sleman, Kulonprogro, and Yogyakarta land offices and their teams for their valuable inputs. The references [46,47] are master theses resulted from this project and supervised by the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Permadi, I.; Herlindah. Electronic title certificate as legal evidence: The land registration system and the quest for legal certainty in Indonesia. Digit. Evid. Electron. Signat. Law Rev. 2023, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.; Bedner, A.; Berenschot, W. The Perils of Legal Formalism: Litigating Land Conflicts in Indonesia. J. Contemp. Asia 2025, 55, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martono, D.B.; Aditya, T.; Subaryono, S.; Nugroho, P. The Legal Element of Fixing the Boundary for Indonesian Complete Cadastre. Land 2021, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T.; Maria-Unger, E.; vd Berg, C.; Bennett, R.; Saers, P.; Lukman Syahid, H.; Erwan, D.; Wits, T.; Widjajanti, N.; Budi Santosa, P.; et al. Participatory Land Administration in Indonesia: Quality and Usability Assessment. Land 2020, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, S.; Bell, K.C.; Lemmen, C.; McLaren, R. Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration; International Federation of Surveyors (FIG): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Metaferia, M.T.; Bennett, R.M.; Alemie, B.K.; Koeva, M. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration and the Framework for Effective Land Administration: Synthesis of Contemporary Experiences. Land 2022, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, S.; McLaren, R.; Lemmen, C. Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration—Providing Secure Land Rights at Scale. Land 2021, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.T.; Bugri, J.T.; Mandhu, F. Responsible and Smart Land Management Interventions: An African Context, 1st ed; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.; Wahyono, E.; Wijaya, G.; Prayoga, R.A.; Prihatin, S.M.; Purbawa, Y.; Sidipurwanty, E.; Juniati, H.; Sakti, T.; Humaedi, M.A. Dynamic implementation of land registration acceleration through community participation: A case study in Banjar District, South Kalimantan Province. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehrehbargh, F.J.; Rajabifard, A.; Atazadeh, B.; Steudler, D. Current challenges and strategic directions for land administration system modernisation in Indonesia. J. Spat. Sci. 2024, 69, 1097–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T. Visualizing Title Uncertainty and Quality Issues in the Digital Era of Land Administration. 2023. Available online: https://fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/7_2023/papers/se02/SE02_aditya_12363.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Applegate, L.M. Technology support for cooperative work: A framework for studying introduction and assimilation in organizations. J. Organ. Comput. 1991, 1, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T.; Adi, F.N.; Laksono, D.P. Survey Pemetaan Batas Bidang Tanah Kolaboratif Lintas Ruang dan Lintas Waktu dengan Piranti AR/VR. In Proceedings of the 72nd ASEAN Flag Council Meeting in conjunction with the FIT-ISI Annual Surveyor Forum 2019, Jakarta, Indonesia, 28–30 November 2019; pp. 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of ATR/BPN. Pendaftaran Tanah Sistematik Lengkap (Complete Systematic Land Registration). Available online: https://www.atrbpn.go.id/ptsl (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Aditya, T.; Santosa, P.B.; Yulaikhah, Y.; Widjajanti, N.; Atunggal, D.; Sulistyawati, M. Title Validation and collaborative mapping to accelerate quality assurance of land registration. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelle, D.; Gutwin, C.; Greenberg, S. Task analysis for groupware usability evaluation. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2003, 10, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T. Usability Issues in Applying Participatory Mapping for Neighborhood Infrastructure Planning. Trans. GIS 2010, 14, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosson, M.B.; Carroll, J.M. Scenario-Based Design. In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies and Emerging Applications; Jacko, J., Sears, A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 1032–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Nigay, L.; Salembier, P.; Marchand, T.; Renevier, P.; Pasqualetti, L. Mobile and Collaborative Augmented Reality: A Scenario Based Design Approach. In Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices; Paternò, F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-M.; Yaqin, M.A.; Lan, V.H. Enhancing Spatial-Reasoning Perception Using Virtual Reality Immersive Experience. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2024, 67, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, J.; Mula, F.J.; Bartlett, K.A.; Naya, F.; Contero, M. The Influence of Immersive and Collaborative Virtual Environments in Improving Spatial Skills. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Yang, T.; Liao, H.; Meng, L. How does map use differ in virtual reality and desktop-based environments? Int. J. Digit. Earth 2020, 13, 1484–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.A.; Velarde, K.G.; Torres, A.L. Augmented Reality for the Development and Reinforcement of Spatial Skills: A Case Applied to Civil Engineering Students. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2024, 14, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, S.M.A.H.; Gunawardana, P.A.M.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Rajaratnam, D. Examining the potential use of augmented reality in construction cost management tools and techniques. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 22, 1847–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M.; Clark, A.; Lee, G. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Found. Trends® Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2015, 8, 73–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadhossein, N.; Richter, A.; Richter, S. ‘What’s the matter with Augmented Reality’—Obstacles to Using AR and Strategies to Address Them. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, 3–5 July 2024; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2024/track09_digittrans/track09_digittrans/7 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Leite, H.; Vieira, L.R. The use of virtual reality in human training: trends and a research agenda. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, E.d.M.; de Arruda, Â.M.; Brandim, A.d.S.; Sebaio, A.G.; Pereira, B.A.; Santos, E.I.d.S.; Caixeta, H.G.; do Nascimento, J.P.; Lemos, L.d.F.; Pereira, M.V. Innovations in Virtual and Augmented Reality: Transforming Organizational Culture Management for the 21st Century. In Interconnections of Knowledge: Multidisciplinary Approaches; Seven Editora: São José dos Pinhais, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panya, D.S.; Kim, T.; Choo, S. An interactive design change methodology using a BIM-based Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shimy, H.; Ragheb, G.A.; Ragheb, A.A. Using Mixed Reality as a Simulation Tool in Urban Planning Project for Sustainable Development. J. Civ. Eng. Arch. 2015, 9, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.; Lee, Y.; Billinghurst, M.; Yoo, B. Efficient VR-AR communication method using virtual replicas in XR remote collaboration. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 2024, 190, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, M.; Campbell-Arvai, V. Co-designing vacant lots using interactive 3D visualizations—Development and application of the Land.Info DSS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilola, S.; Jaalama, K.; Kangassalo, P.; Nummi, P.; Staffans, A.; Fagerholm, N. 3D visualisations for communicative urban and landscape planning: What systematic mapping of academic literature can tell us of their potential? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 234, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ens, B.; Lanir, J.; Tang, A.; Bateman, S.; Lee, G.; Piumsomboon, T.; Billinghurst, M. Revisiting collaboration through mixed reality: The evolution of groupware. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2019, 131, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindele, N.; Taiwo, R.; Sarvari, H.; Oluleye, B.I.; Awodele, I.A.; Olaniran, T.O. A state-of-the-art analysis of virtual reality applications in construction health and safety. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M. AR in the Architecture Domain: State of the Art. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Schönberger, C.; Lienhart, W. Interactive planning of GNSS monitoring applications with virtual reality. Surv. Rev. 2024, 56, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imottesjo, H.; Kain, J.-H. The Urban CoCreation Lab—An Integrated Platform for Remote and Simultaneous Collaborative Urban Planning and Design through Web-Based Desktop 3D Modeling, Head-Mounted Virtual Reality and Mobile Augmented Reality: Prototyping a Minimum Viable Product and Developing Specifications for a Minimum Marketable Product. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohil, M.K.; Ashok, Y. Visualization of urban development 3D layout plans with augmented reality. Results Eng. 2022, 14, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskas, L.; Paulauskas, A.; Blažauskas, T.; Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R. Reconstruction of Industrial and Historical Heritage for Cultural Enrichment Using Virtual and Augmented Reality. Technologies 2023, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksono, D.; Aditya, T. Utilizing A Game Engine for Interactive 3D Topographic Data Visualization. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Gómez, R.; Cascado-Caballero, D.; Sevillano, J.-L. Academic methods for usability evaluation of serious games: A systematic review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2016, 76, 5755–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, B.; Herold, S. Potential effectiveness and efficiency issues in usability evaluation within digital health: A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 208, 111881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T.; Andaru, R.; Santosa, P.B.; Wijaya, C.; Surojaya, A.; Nugroho, A.; Ashaari, F.; Sulistyawati, M.N.; Nasywa, A.; Emor, B.; et al. Design of Mixed Reality Applications for Visualizing Integrated 3D Land Information Services. In Proceedings of the 12th International FIG Workshop on LADM & 3D LA, Kuching, Malaysia, 24–26 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Çöltekin, A.; Lochhead, I.; Madden, M.; Christophe, S.; Devaux, A.; Pettit, C.; Lock, O.; Shukla, S.; Herman, L.; Stachoň, Z.; et al. Extended Reality in Spatial Sciences: A Review of Research Challenges and Future Directions. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, A.N. Use of AR Technology for Visualizing 3D information of Land and Spatial Plan Maps in Terban and Kotabaru, Yogyakarta City. Master’s Thesis, Magister in Geomatics Engineering at UGM, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2024. (In Bahasa Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

- Ashaari, F. Utilization of a Virtual Reality Application for Presenting Land and Spatial Plan Information in Argomulyo Village, Bantul Regency. Master’s Thesis, Magister in Geomatics Engineering at UGM, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2024. (In Bahasa Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).