Evaluating Machine Learning and Statistical Prediction Techniques in Margin Sampling Active Learning for Rapid Landslide Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data

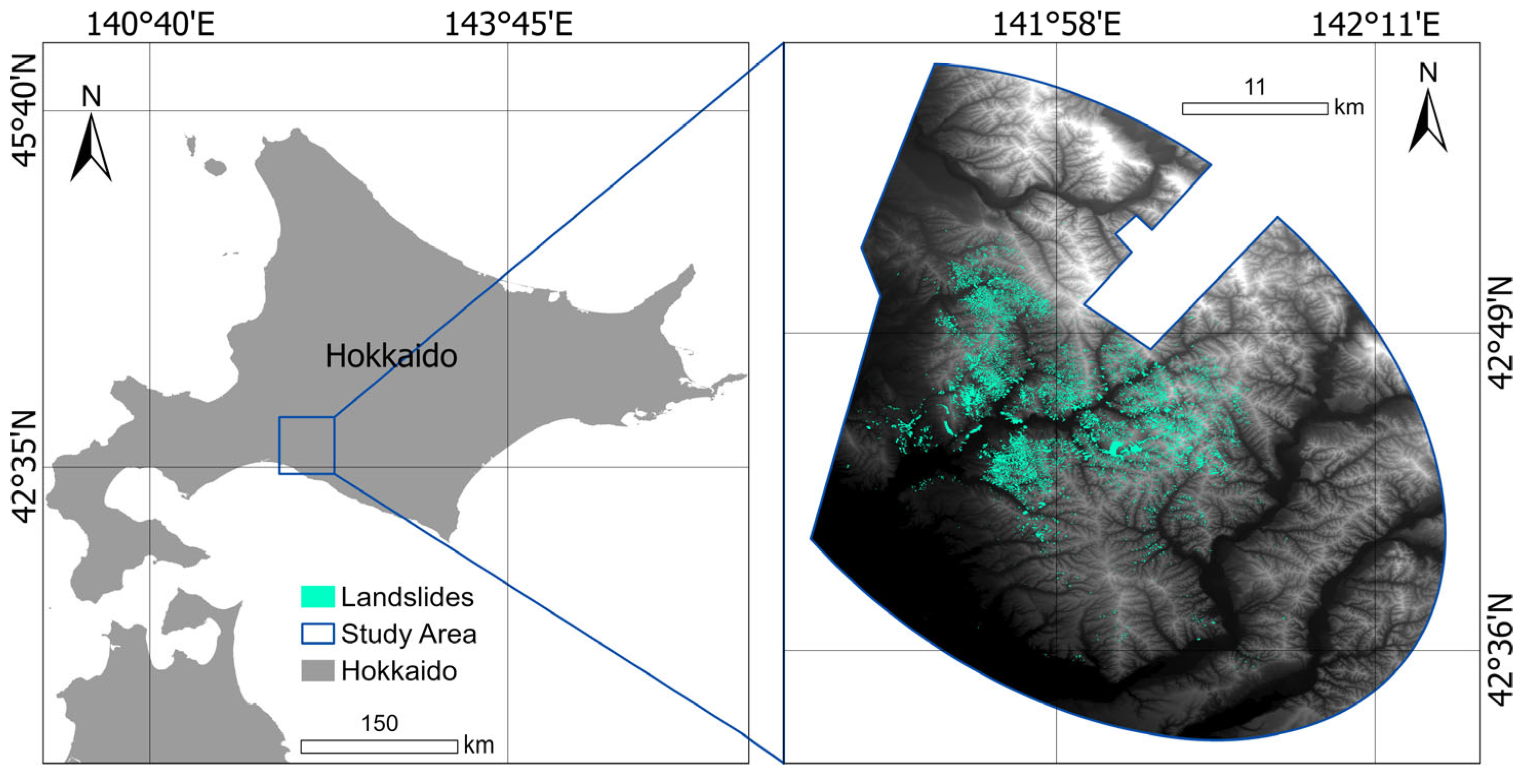

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Pixel-Based Landslide Inventory

2.3. Predictor Variables

3. Methods

3.1. Landslide Modeling Techniques

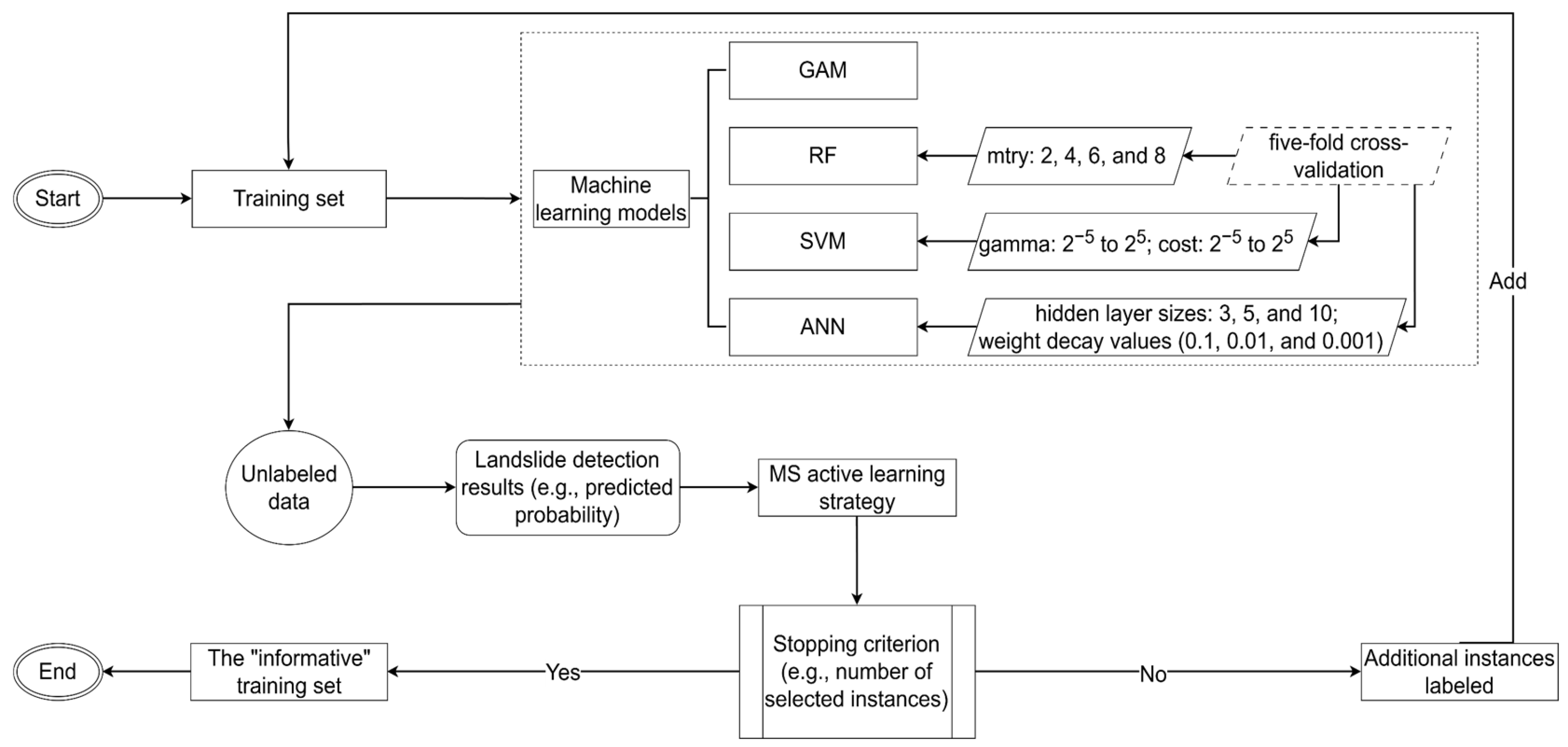

3.2. Margin Sampling Active Learning

3.3. Experiment Design and Performance Evaluation

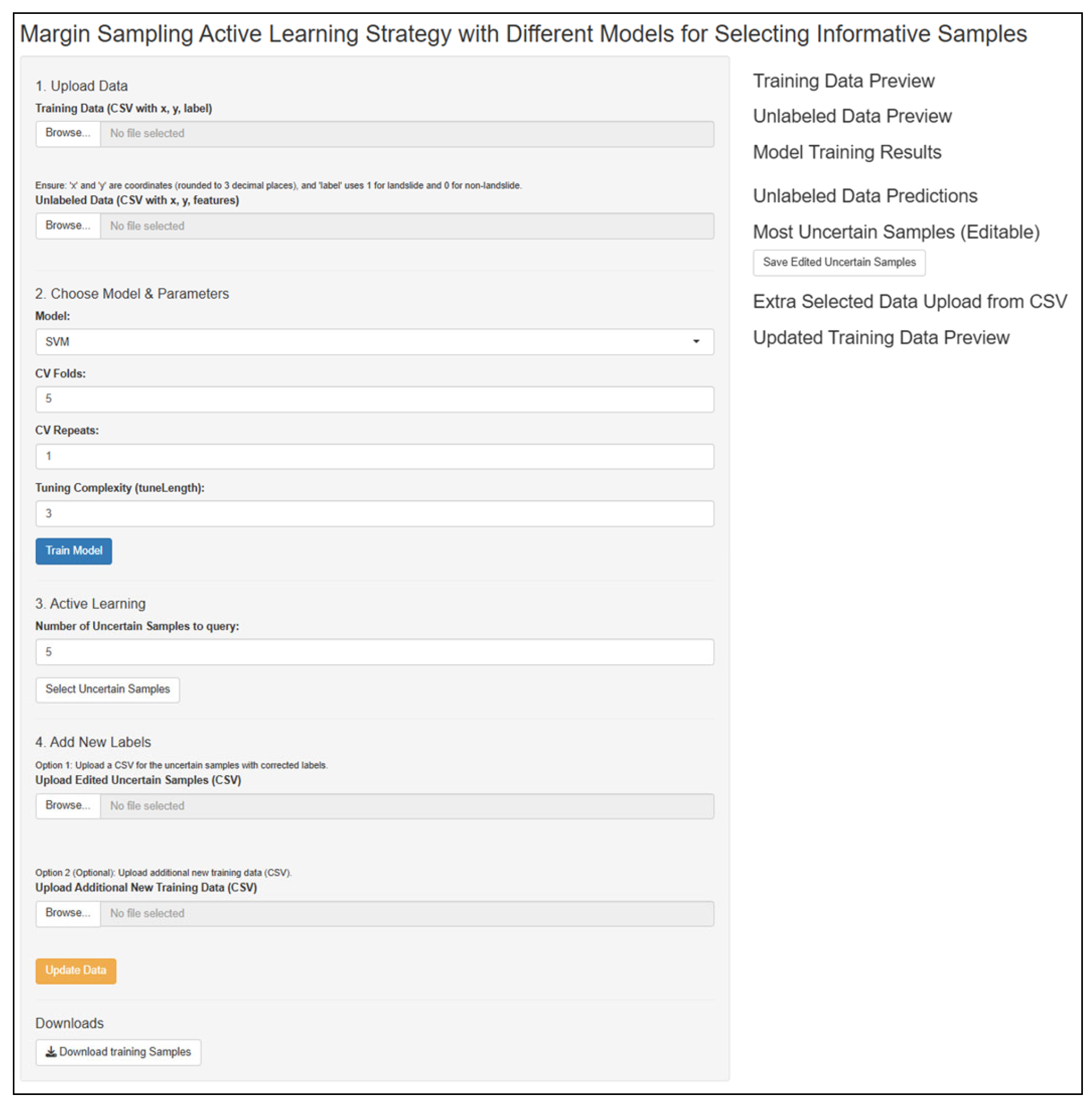

3.4. Graphical User Interface

4. Results

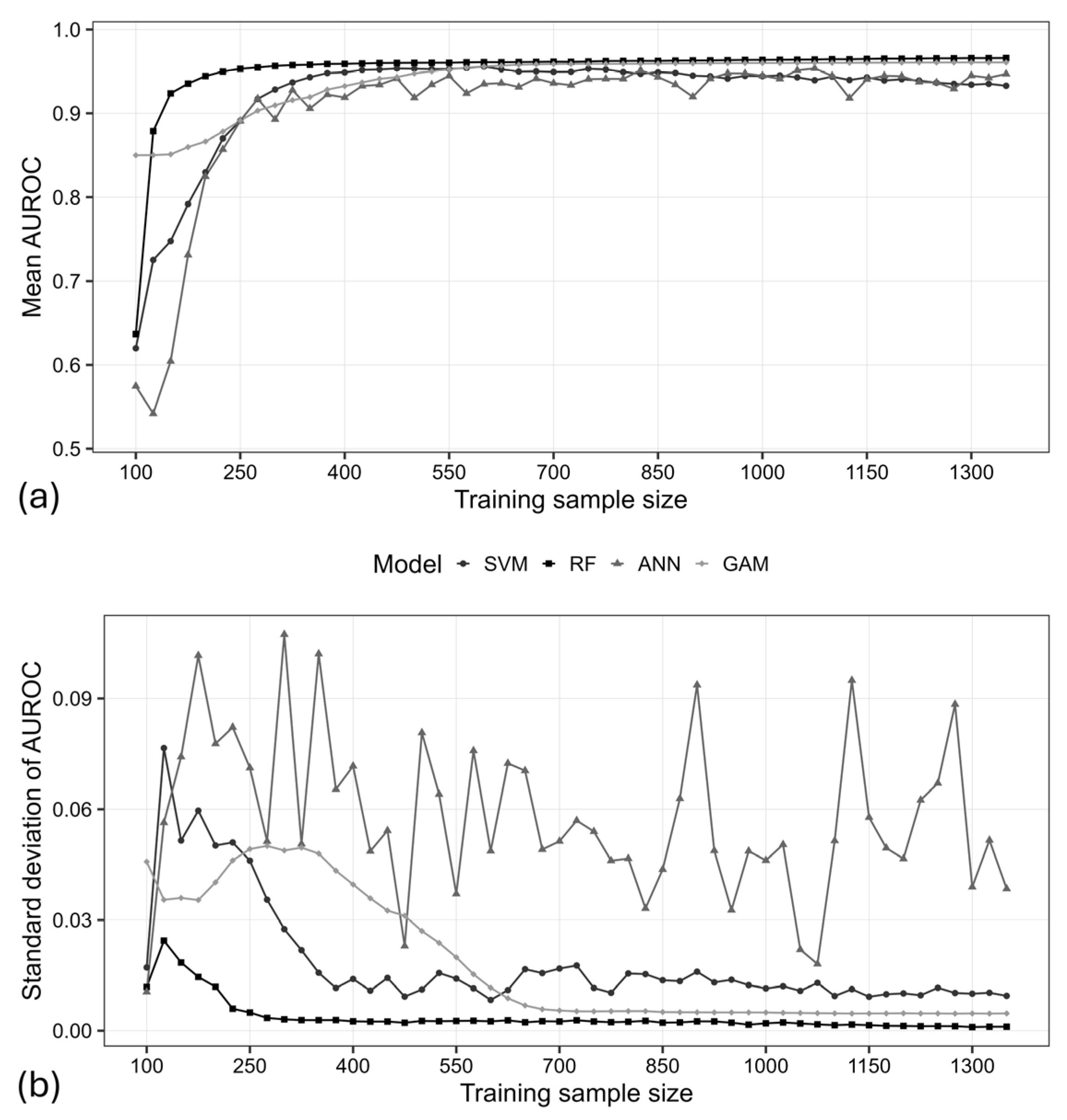

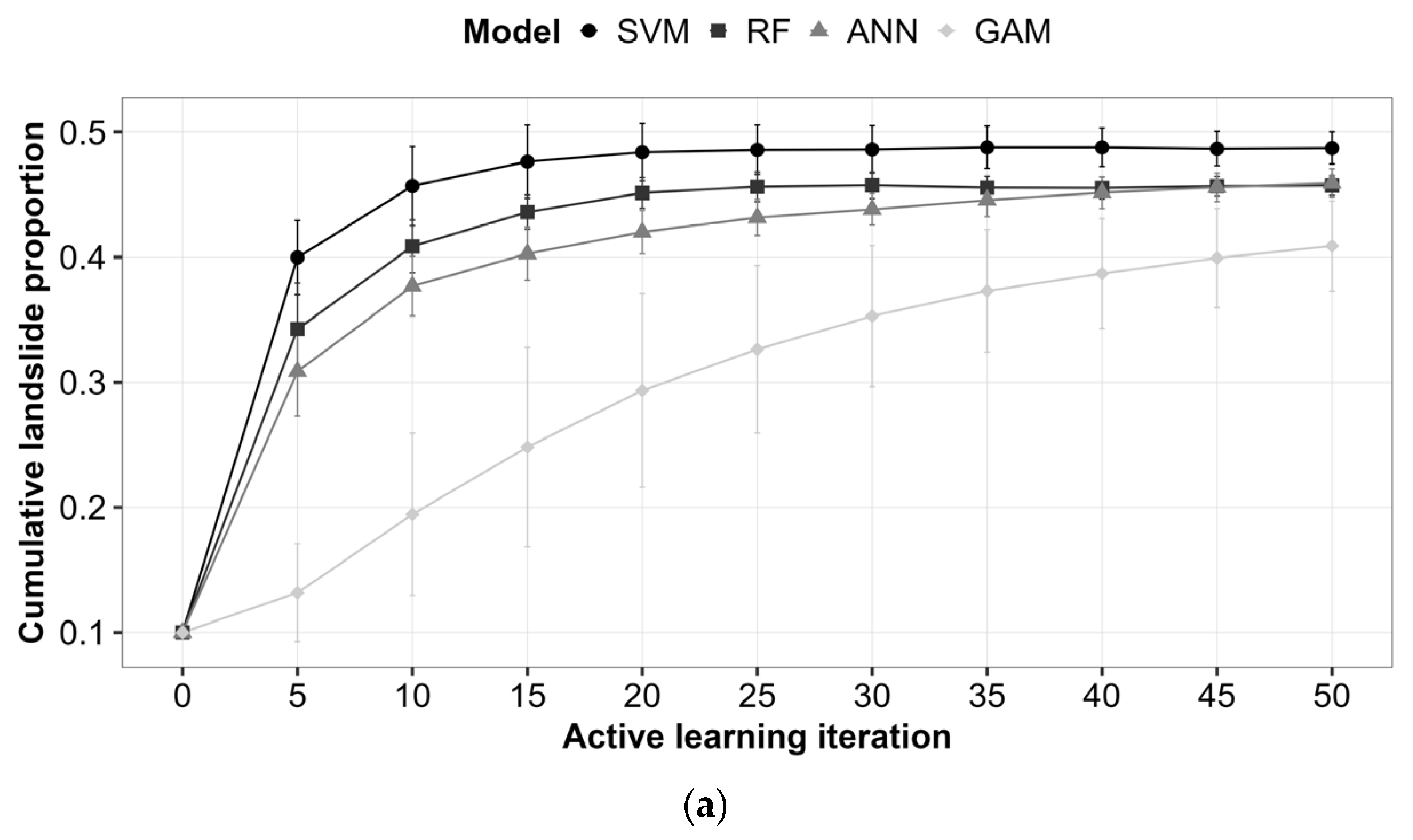

4.1. Comparison of Predictive Accuracy

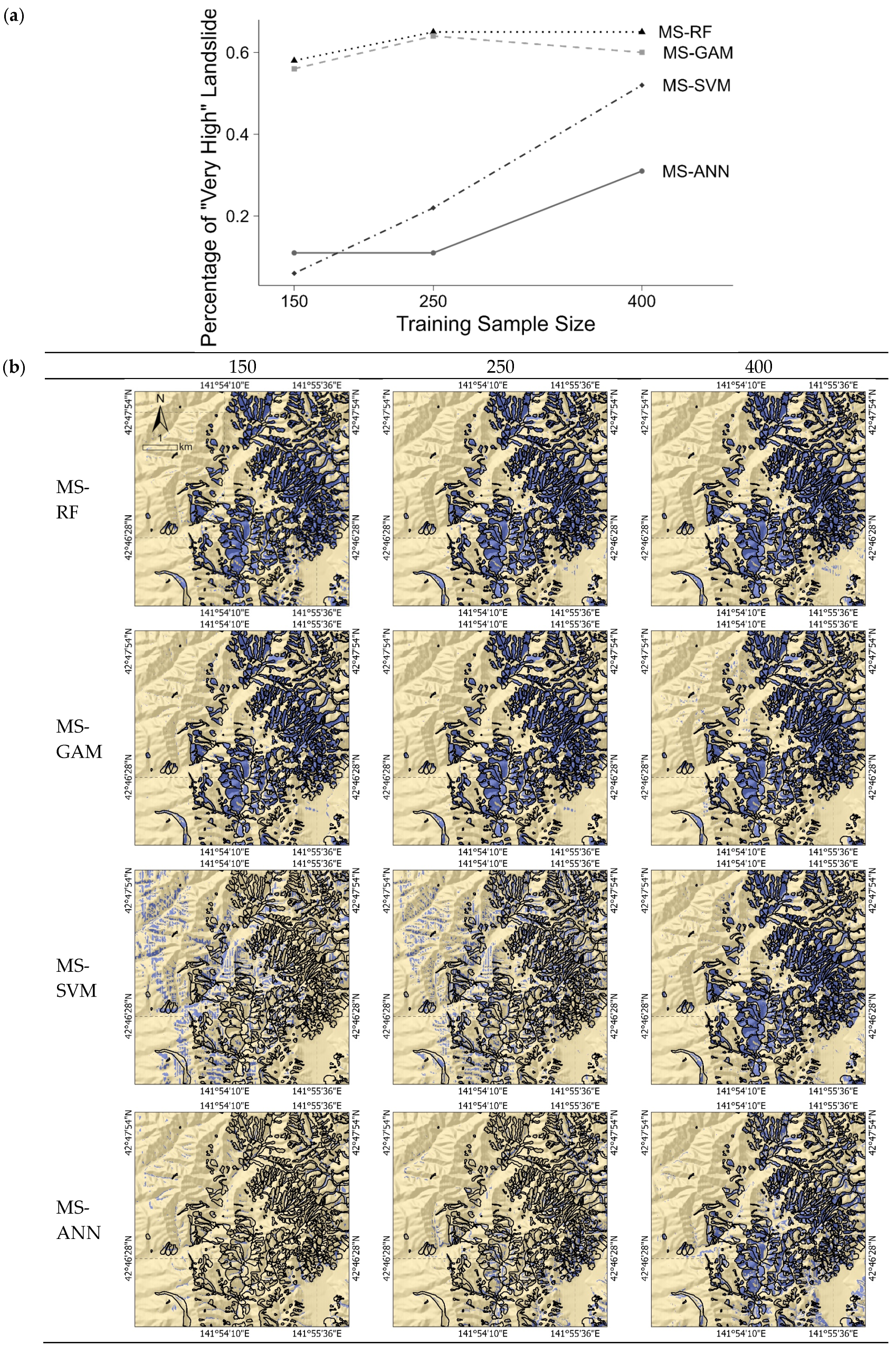

4.2. Comparison of Landslide Detection Map Appearances

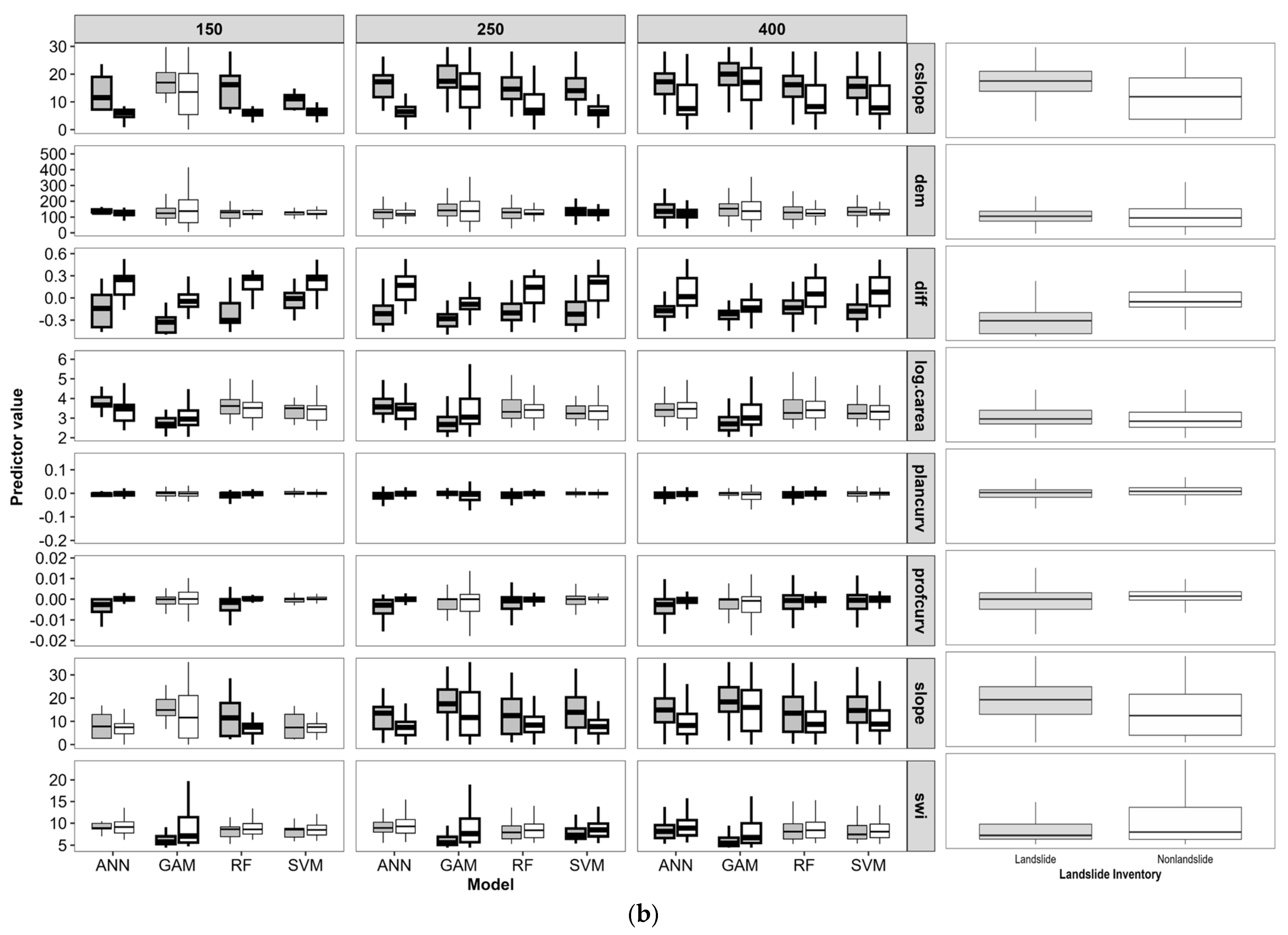

4.3. The Distribution of Landslide and Non-Landslide in the Training Set

4.4. A Ranking of Predictor Importance

5. Discussion

5.1. Impact of Model Selection on Margin Sampling

5.2. The Importance of Training Data Quality in Landslide Detection Assessment

5.3. Limitations and Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Froude, M.J.; Petley, D.N. Global Fatal Landslide Occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merghadi, A.; Yunus, A.P.; Dou, J.; Whiteley, J.; ThaiPham, B.; Bui, D.T.; Avtar, R.; Abderrahmane, B. Machine Learning Methods for Landslide Susceptibility Studies: A Comparative Overview of Algorithm Performance. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 207, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, B.; Dwivedi, R. Review on Remote Sensing Methods for Landslide Detection Using Machine and Deep Learning. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Xu, Q.; Ge, D. Detecting Slow-Moving Landslides Using InSAR Phase-Gradient Stacking and Deep-Learning Network. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 963322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagli, N.; Frodella, W.; Morelli, S.; Tofani, V.; Ciampalini, A.; Intrieri, E.; Raspini, F.; Rossi, G.; Tanteri, L.; Lu, P. Spaceborne, UAV and Ground-Based Remote Sensing Techniques for Landslide Mapping, Monitoring and Early Warning. Geoenviron. Disasters 2017, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Pang, H.; Li, Y.; Fan, L.; Wei, S.; Yuan, Z.; Fang, Y. Applications and Advancements of Spaceborne InSAR in Landslide Monitoring and Susceptibility Mapping: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsironi, V.; Ganas, A.; Karamitros, I.; Efstathiou, E.; Koukouvelas, I.; Sokos, E. Kinematics of Active Landslides in Achaia (Peloponnese, Greece) through InSAR Time Series Analysis and Relation to Rainfall Patterns. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, A.C.; Guzzetti, F.; Chang, K.-T.; Monserrat, O.; Martha, T.R.; Manconi, A. Landslide Failures Detection and Mapping Using Synthetic Aperture Radar: Past, Present and Future. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 216, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, M.; Amitab, K.; Maji, A.K.; Jasińska, E.; Gono, R.; Leonowicz, Z.; Jasiński, M. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning: A Literature Survey. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, B. Active Learning; Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978-3-031-00432-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Ward, R.; Wang, Z.J. Active-Learning-Incorporated Deep Transfer Learning for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 4048–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Brenning, A. Active-Learning Approaches for Landslide Mapping Using Support Vector Machines. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Brenning, A. Unsupervised Active–Transfer Learning for Automated Landslide Mapping. Comput. Geosci. 2023, 181, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Pijush, S. A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning-Based Methods in Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Geol. J. 2023, 58, 2283–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, J.N.; Brenning, A.; Petschko, H.; Leopold, P. Evaluating Machine Learning and Statistical Prediction Techniques for Landslide Susceptibility Modeling. Comput. Geosci. 2015, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, L. Review on Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Support Vector Machines. CATENA 2018, 165, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien Bui, D.; Tuan, T.A.; Klempe, H.; Pradhan, B.; Revhaug, I. Spatial Prediction Models for Shallow Landslide Hazards: A Comparative Assessment of the Efficacy of Support Vector Machines, Artificial Neural Networks, Kernel Logistic Regression, and Logistic Model Tree. Landslides 2016, 13, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, M.; Galanti, Y.; Bartelletti, C.; Persichillo, M.G.; Barsanti, M.; Giannecchini, R.; Avanzi, G.D.; Cevasco, A.; Brandolini, P.; Galve, J.P.; et al. The Influence of the Inventory on the Determination of the Rainfall-Induced Shallow Landslides Susceptibility Using Generalized Additive Models. CATENA 2020, 193, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Wang, F.; Iio, A. Characteristics of Landslides Triggered by the 2018 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake, Northern Japan. Landslides 2019, 16, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, S.; Twele, A.; Martinis, S. Landslide Mapping in Vegetated Areas Using Change Detection Based on Optical and Polarimetric SAR Data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Goli Mokhtari, L.; Shirzadi, A.; Shahabi, H.; Bahrami, S. A Comparison Study on the Quantitative Statistical Methods for Spatial Prediction of Shallow Landslides (Case Study: Yozidar-Degaga Route in Kurdistan Province, Iran). Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Samui, P.; Chwała, M.; He, Y. Landslide Susceptibility Research Combining Qualitative Analysis and Quantitative Evaluation: A Case Study of Yunyang County in Chongqing, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.V.; Wakai, A.; Sato, G.; Viet, T.T.; Kitamura, N. Simple Method for Shallow Landslide Prediction Based on Wide-Area Terrain Analysis Incorporated with Surface and Subsurface Flows. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2022, 23, 04022028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, M.I.; Aristizábal, E.; Gómez, F. Morphometrical Analysis of Torrential Flows-Prone Catchments in Tropical and Mountainous Terrain of the Colombian Andes by Machine Learning Techniques. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 983–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małka, A. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping of Gdynia Using Geographic Information System-Based Statistical Models. Nat. Hazards 2021, 107, 639–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenchow, J.; Brenning, A.; Richter, M. Geomorphic Process Rates of Landslides along a Humidity Gradient in the Tropical Andes. Geomorphology 2012, 139–140, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planet Team. Planet Application Program Interface. In Space for Life on Earth; Planet Team: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 2017, p. 2. Available online: https://api.planet.com (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Fiorucci, F.; Ardizzone, F.; Mondini, A.C.; Viero, A.; Guzzetti, F. Visual Interpretation of Stereoscopic NDVI Satellite Images to Map Rainfall-Induced Landslides. Landslides 2019, 16, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.J. Generalized Additive Models. In Statistical Models in S.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-203-73853-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoubzadeh-Bavandpour, A.; Rajabi, M.; Nozari, H.; Ahmad, S. Support Vector Machine Applications in Water and Environmental Sciences. In Computational Intelligence for Water and Environmental Sciences; Bozorg-Haddad, O., Zolghadr-Asli, B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 291–310. ISBN 978-981-19-2519-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tyralis, H.; Papacharalampous, G.; Langousis, A. A Brief Review of Random Forests for Water Scientists and Practitioners and Their Recent History in Water Resources. Water 2019, 11, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.W. Machine Learning Methods in the Environmental Sciences: Neural Networks and Kernels; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-521-79192-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, Second Edition; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-37027-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S. Mgcv: Mixed GAM Computation Vehicle with Automatic Smoothness Estimation, R Package Version 1.8–12; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Van Engelen, J.E.; Hoos, H.H. A Survey on Semi-Supervised Learning. Mach. Learn. 2020, 109, 373–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, M.; Kovačević, M.; Bajat, B.; Voženílek, V. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Using SVM Machine Learning Algorithm. Eng. Geol. 2011, 123, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Pradhan, B.; Jebur, M.N.; Bui, D.T.; Xu, C.; Akgun, A. Spatial Prediction of Landslide Hazard at the Luxi Area (China) Using Support Vector Machines. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 75, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Wing, J.; Weston, S.; Williams, A.; Keefer, C.; Engelhardt, A.; Cooper, T.; Mayer, Z.; Kenkel, B.; Benesty, M. Caret: Classification and Regression Training; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Qin, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, R.; Song, Y.; Lang, T.; Zhou, X.; Huangfu, W.; et al. Mapping Landslide Hazard Risk Using Random Forest Algorithm in Guixi, Jiangxi, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wänstedt, S. The Introduction of Neural Network System and Its Applications in Rock Engineering. Eng. Geol. 1998, 49, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Youssef, A.; Varathrajoo, R. Approaches for Delineating Landslide Hazard Areas Using Different Training Sites in an Advanced Artificial Neural Network Model. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2010, 13, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardeshi, S.D.; Autade, S.E.; Pardeshi, S.S. Landslide Hazard Assessment: Recent Trends and Techniques. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beguería, S. Validation and Evaluation of Predictive Models in Hazard Assessment and Risk Management. Nat. Hazards 2006, 37, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattini, P.; Crosta, G.; Carrara, A. Techniques for Evaluating the Performance of Landslide Susceptibility Models. Eng. Geol. 2010, 111, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, C.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Zeileis, A.; Hothorn, T. Bias in Random Forest Variable Importance Measures: Illustrations, Sources and a Solution. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, A.; Long, S.; Fieguth, P. Detecting Rock Glacier Flow Structures Using Gabor Filters and IKONOS Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 125, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Duan, P.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Non-Landslide Sampling Strategies on Machine Learning Models in Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predictor Variable | Landslides Median (IQR) | Non-Landslides Median (IQR) | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| slope angle (°, slope) | 18.51 (11.42) | 9.88 (17.54) | DEM with a 10 m × 10 m resolution |

| plan curvature (radians per 100 m, plancurv) | −0.00007 (0.01242) | 0.00105 (0.02024) | |

| profile curvature (radians per 100 m, profcurv) | −0.00029 (0.00448) | 0.0000 (0.00295) | |

| upslope contributing area (log10 m2, log.carea) | 2.72 (0.65) | 2.91 (0.67) | |

| elevation (m, dem) | 138.7 (73.99) | 117.75 (139.1) | |

| SWI | 5.72 (2.05) | 7.38 (6.76) | |

| catchment slope angle (cslope) | 19.46 (8.04) | 10.95 (14.81) | |

| NDVI difference (diff) | −0.29 (0.28) | −0.03 (0.21) | PlanetScope optical images with a 3 m × 3 m resolution |

| landslide type | co-seismic landslides | ||

| landslide process | shallow debris slides | ||

| triggering mechanism | earthquake | ||

| geological units | sedimentary and volcanic rocks | ||

| Training Size | Model | Mean AUROC | Top 1% | Top 2% | Top 4% | Top 5% | Top 10% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | Precision | Recall | Precision | Recall | Precision | Recall | Precision | Recall | |||

| 150 | ANN | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.31 |

| GAM | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.18 | 0.66 | 0.35 | |

| RF | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.23 | 0.80 | 0.42 | |

| SVM | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.22 | |

| 250 | ANN | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.38 |

| GAM | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 0.37 | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.74 | 0.39 | |

| RF | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 0.18 | 0.84 | 0.22 | 0.81 | 0.42 | |

| SVM | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 0.76 | 0.40 | |

| 400 | ANN | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.77 | 0.40 |

| GAM | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.41 | |

| RF | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.09 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 0.80 | 0.42 | |

| SVM | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.41 | |

| Variable | Rank | Max Variable Importance | MS-GAM | MS-ANN | MS-SVM | MS-RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diff | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| cslope | 2 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.25 |

| log.carea | 3 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| SWI | 4 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.1 |

| slope | 5 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.11 |

| plancurv | 6 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| dem | 7 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| profcurv | 8 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liang, C.; Yan, D.; Wang, Z. Evaluating Machine Learning and Statistical Prediction Techniques in Margin Sampling Active Learning for Rapid Landslide Mapping. Geomatics 2025, 5, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040074

Miao J, Wang Z, Liang C, Yan D, Wang Z. Evaluating Machine Learning and Statistical Prediction Techniques in Margin Sampling Active Learning for Rapid Landslide Mapping. Geomatics. 2025; 5(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Jing, Zhihao Wang, Chenbin Liang, Dong Yan, and Zhichao Wang. 2025. "Evaluating Machine Learning and Statistical Prediction Techniques in Margin Sampling Active Learning for Rapid Landslide Mapping" Geomatics 5, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040074

APA StyleMiao, J., Wang, Z., Liang, C., Yan, D., & Wang, Z. (2025). Evaluating Machine Learning and Statistical Prediction Techniques in Margin Sampling Active Learning for Rapid Landslide Mapping. Geomatics, 5(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040074