Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This study reveals that mining activities in Mazapil, Zacatecas, Mexico, have caused significant changes in the terrain, with ground depressions greater than −333 m and waste accumulations greater than +152 m.

- Remote sensing (RS) techniques were used, with multi-temporal Landsat 5 and 8 images, as well as Digital Elevation Models (DEM) from 1998 and 2014.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The analysis quantified a total excavation volume of 413,524,124 m3 and an embankment volume of 431,194,785 m3.

- Despite limitations related to DEM resolution and data availability, the method used proved to be effective for remote quantification of large-scale topographic alterations.

Abstract

Mining activities are conducted to extract valuable minerals from the Earth, which are used to manufacture many objects. However, these operations generate landform alterations, such as deep excavations, artificial embankments, and landscape reshaping. In this study, landform changes were monitored in a mining area in Mazapil, Zacatecas, Mexico, using geomatic techniques. Multitemporal Landsat satellite images and digital elevation models (DEMs) from different years were used to detect and quantify landform alterations and estimate the volumes of removed material. The results show ground depressions greater than −333 m and waste material accumulations greater than +152 m, with an average standard deviation of ±3.6 m. A total excavation volume of 413.524 million m3 and a total fill volume of 431.194 million m3 were quantified, with an estimated standard deviation of ±810 m3. The proposed methodology proved effective for the remote quantification of large-scale relief disturbances in open-pit mining areas. It can also be used for environmental monitoring and hydrological risk assessment in active and inactive mining areas.

1. Introduction

Mining is one of the most important economic activities globally, enabling the extraction of minerals and materials essential for the manufacture of many products. However, mining operations generate a series of negative physical, environmental, and social impacts [1,2]. Among the most obvious effects are direct alterations to the Earth’s crust such as excavations, the accumulation of waste material, and tailings dams, which cause deforestation, erosion, the modification of natural hydrology, and the generation of solid and liquid toxic wastes [3,4]. These mining wastes can contaminate the air, soil, and water if not properly treated [5,6].

Due to mining-induced impacts, extensive research has been conducted worldwide. Studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and Asia have shown that multitemporal satellite imagery, DEMs, photogrammetric techniques, and other sensors can effectively detect landscape disturbances, changes in water bodies, and changes in vegetation cover [7,8,9,10]. For example, some authors assessed environmental changes in southwestern Sierra Leone, West Africa, using multi-date Landsat infrared imagery, supplemented with hydrological and biophysical field data, to monitor the temporal and spatial dynamics of features in mining areas [7]. Others evaluated the use of multitemporal Landsat 5 and 7 imagery, SPOT Panchromatic data (from the French “Satellite Pour l’Observation de la Terre”), and ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer) to map the natural environment and assess the impact of mining activities on land and water resources in Greece [8]. Another study conducted a first-order risk assessment in the Witwatersrand Basin of South Africa to help identify vulnerable land use near gold and uranium mines, generating risk maps using RS and GIS [11]. Researchers evaluated the use of DEMs from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) and ASTER space missions to identify changes in local topography and surface hydrology around the Geita gold mine in Tanzania [12]. They also assessed environmental conditions and developed a monitoring system for potential area and perimeter changes in acid lakes in the Canakkale open-pit lignite mining area in Turkey, using RS at a regional scale [13]. More recent approaches have integrated machine learning (ML) algorithms with RS and GIS to perform automated and scalable assessments of mining-driven transformations. In this area [10], large-scale automatic detection of open-pit mining areas was carried out by integrating multitemporal DEMs and multispectral imagery, using object analysis and the “Random Forest” algorithm in Inner Mongolia, China. Furthermore, research has been conducted on the environmental impact of underground coal mining at the Bogdanka mine in Poland, using spectral indices, satellite radar interferometry, GIS tools, and ML algorithms, based on optical, radar, geological, hydrological, and meteorological data. Research has also been conducted to assess the environmental impact of the area affected by a dam collapse in Brazil, using satellite imagery [14]. Open-pit mines have been identified in Hubei Province, China, using Artificial Intelligence and Enhanced R-CNN Mask and Model Transfer Learning (IMRT) [15]. Others have assessed the impact of mining activities on the biophysical characteristics of the land surface using multitemporal optical and temperature satellite imagery in several countries. The results indicated that forest and green space cover decreased from 9.95 km2 in 1989 to 5.9 km2 in 2019 for the Sungun mine [16]. In Mexico, environmental externalities associated with mining activities have been evaluated, such as those observed at a mine in Mazapil, Zacatecas, where land-use change, vegetation loss, and groundwater dynamics were analyzed [17]. Anthropogenic transformations of the landscape have been visually identified and vectorized on aerial images in a mining area of Karviná, in the Ostrava-Karviná mining district, Czech Republic [18]. Review studies have been conducted on the classification of landforms, identifying the global distribution of studies and the methods, datasets, units of analysis, and validation techniques used. These reviews found that studies were predominantly conducted in Europe, South and East Asia, and North America. The methodologies used were expert knowledge, object-based analysis, and pixel-based analysis. The most frequently used datasets were DEMs, and the validation techniques were primarily based on expert knowledge [19].

Monitoring of changes in relief has been carried out using conventional land surveys, which previously relied on mechanical instruments such as theodolites, tape measures, and leveling devices [20]; however, they have been replaced by robotic total stations, Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), terrestrial laser scanners, and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) sensors [21,22]. However, these methods are often limited by high operational costs and limited temporal coverage. In contrast, recent advances in RS, including airborne and satellite photogrammetry and radar interferometry [23,24,25], have enabled continuous, large-scale, and non-invasive monitoring of terrain morphology, offering an effective alternative to traditional ground-based measurements. Despite these advances, satellite information has been underutilized due to a lack of awareness of its potential and its limitations related to geometric resolution. However, for environmental monitoring in mining areas, satellite imagery is a highly cost-effective and replicable technique.

Within this framework, the overall objective of this study was to detect and measure mining-induced relief alterations in Mazapil, Zacatecas, Mexico, using satellite imagery and GIS processing. This approach was designed to overcome the limitations of field surveying by combining multitemporal satellite imagery and DEMs to detect relief changes and estimate material extraction volumes.

As shown in a review article [19], very few or no studies have been conducted on landform classification in mining areas in Mexico and South America. Therefore, this study contributes to the monitoring of mining areas in Mexico. Additionally, although some studies use DEMs to measure changes in relief, such as [8,12], they do not evaluate the accuracy of the DEMs used or calculate the standard deviation of the obtained results. The present study uses several DEM sources, and a comparison is made to evaluate the existing errors between the different DEMs. Furthermore, this work calculates the standard deviation pixel by pixel, generating a standard deviation map throughout the study area. This allows for visualizing the geographic positions with the highest standard deviation and observing whether they are within the mining area, in a valley, or in the mountains. This enables the potential for in situ verification of the points with the greatest deviation with a GNSS. Likewise, this study details the procedure for calculating elevation differences and extracted material volumes, which will help further research apply the proposed methodology.

This article is divided into several sections: The Introduction describes the problem studied and its importance, defines the current state of the research field and the main objective, and highlights the main contributions of this work. The Materials and Methods Section describe the data and instruments used, as well as the methodology applied. The Results Section presents the experimental results and their interpretation. The Discussion Section discusses the results and how they can be interpreted considering previous studies. Finally, the Conclusions Section makes recommendations for future research, analyzes the implications of the research, and describes how the objectives were met.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

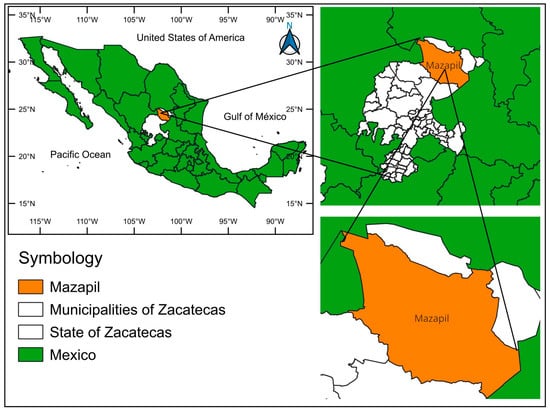

This research was conducted in a mining region of Mexico, located in the state of Zacatecas and the municipality of Mazapil. The study area is geographically located between latitudes 24°33′57.57″ and 24°42′14.56″ north and between longitudes 101°50′45.10″ and 101°27′10.32″ west (Figure 1). This area is part of two physiographic provinces, namely, the Sierra Madre Occidental (52.7%) and the Mesa del Centro (47.3%), which include the sub provinces of Sierras Transversals and Río Grande [26].

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area (source: own elaboration based on maps from [27]).

Mazapil is characterized by a highly variable landform that includes flat terrain, peaks, ridges, slopes, and valleys. Elevations range from 1300 to 3200 m above the mean sea level. The climate is classified as dry temperate, semi-dry temperate, very dry semi-warm, and semi-cold sub-humid, with a mean annual temperature of approximately 17 °C and annual precipitation between 200 and 600 mm, concentrated during the summer months. The dominant vegetation cover consists of shrubland (95.28%), forest (1.68%), grassland (0.90%), mesquite woodland (0.04%), and areas with no clear vegetation (0.09%) [26].

Mazapil is located within the Mexican Silver Belt, one of the most important metallogenic provinces in the country, home to large poly-metallic deposits of gold, silver, lead, and zinc [28]. This mineral wealth has driven the development of large open-pit mining complexes, including the Peñasquito Mining Unit, whose open-pit operation has generated significant transformations in the terrain through excavations, waste dumps, tailings dams, and haul roads [17].

2.2. Methodology

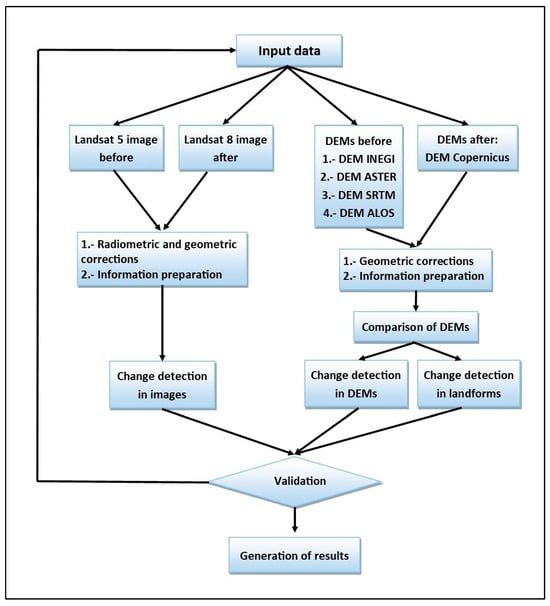

A mixed-methodological approach was implemented, integrating quantitative techniques for the analysis of altimetric differences and volumetric estimation, and a qualitative approach for the characterization of landforms. This strategy was designed based on the general methodology for change detection proposed in [29] and incorporated change detection and classification techniques such as those described in [30]. The method is structured into five stages:

- Acquisition of input data (satellite and DEM images, before and after mining activity).

- Radiometric and geometric corrections and information preparation.

- Change detection and analysis.

- Evaluation of the reliability of the obtained data.

- Generation of results.

Figure 2 presents the proposed methodology in a flowchart.

Figure 2.

Methodology for detecting changes in relief.

This methodology provides a replicable workflow, allowing for the integration of RS and GIS techniques to assess the physical impacts of mining on the landscape.

2.2.1. Acquisition of Satellite Images and DEMs Before and After Mining Activity

In the first stage, multitemporal satellite images were acquired from 1998 and after the development of mining activity in 2014. The images were obtained from the medium-resolution Landsat 5 and 8 satellites, widely recognized for their reliability in environmental monitoring. The years 1998 and 2014 were chosen because they are the years in which the INEGI and Copernicus DEMs were generated, respectively. The images were obtained from the same years to ensure comparability with the DEMs, as mining activity generates changes every week, month, and year. Furthermore, the years 1998 and 2014 allowed us to visualize the before and after of the start of large-scale mining operations.

To extract altimetric information, DEMs were acquired from various sources, such as the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) from 1998, the ASTER satellite from 1999, the SRTM space mission from 2000, the Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS PALSAR) from 2006, and the Copernicus mission from 2011 to 2015, with a geometric resolution of 15, 30, 30, and 17 m, respectively. All data were downloaded from official websites such as INEGI, the United States Geological Survey (USGS), Copernicus Browser, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). These datasets provided us with temporal and redundant information for statistical analysis of the errors and standard deviation of the detected elevation differences. Table 1 shows a summary of the data used by year and data source.

Table 1.

Information on the input data used in this research.

2.2.2. Radiometric and Geometric Corrections and Preparation of Satellite Images and DEM

Satellite image preprocessing included radiometric and geometric corrections, as well as the transformation of the datasets to the WGS84 UTM reference coordinate system, Zone 14 North. This process was performed using GIS software QGIS v3.40.5, ensuring homogenization and spatial compatibility of the inputs. For radiometric corrections, the conversion from Digital Numbers (DNs) to Upper Atmospheric Reflectance (TOA) was performed using the standard equation provided by the data source [38]. This step allowed for the normalization of pixel values, reducing the influence of atmospheric conditions, sensor-specific differences, and acquisition dates, thereby improving the comparability of the multitemporal images.

The DEMs were projected to the WGS84 UTM Zone 14 North reference coordinate system to obtain coordinates in meters. They were interpolated to a pixel resolution of 15 × 15 m to ensure uniformity and subsequently cropped to the extent of the mining area of interest. To measure the magnitude of the differences between the DEMs, a comparison was made, and the vertical error (∆h), mean error (ME), standard deviation (SD), and root mean square error (RMSE) were calculated pixel by pixel [39]. The INEGI DEM was considered the true value, as it is a model obtained with aerial photogrammetry, field information, and higher resolution, using the following equations:

Vertical error (∆h):

where ∆h is the vertical error of a measurement, DEMx is digital elevation model x, and DEMINEGI is the INEGI DEM.

Mean error (ME):

Standard deviation (SD):

Root means square error (RMSE):

In this preprocessing stage, the reflectance values of the satellite images were calibrated, the DEMs were interpolated to the same pixel resolution, and the dataset was projected to the same reference coordinate system and cropped to the extent of the area of interest. This homogenization of the dataset allowed for pixel-to-pixel correspondence, an essential requirement for the subsequent detection of changes in relief and for volumetric calculation.

2.2.3. Detection of Changes in Satellite Images and DEMs

To visualize changes in the mining area using satellite imagery, combinations of shortwave infrared (SWIR), near infrared (NIR), and red bands were used. This false-color band combination is used for vegetation analysis and shows greater differences between soil, vegetation, and water bodies [40].

The monitoring of relief changes in the mining area was conducted by classifying the different relief forms before and after mining activity. The relief type classification method was based on the approach proposed in [41], which allows for the segmentation of relief types from the DEM. This process facilitated the identification of significant geomorphological transformations due to mining operations.

Topographic changes were detected using the different DEM technique. A pixel-by-pixel algebraic subtraction was performed between the 2014 Copernicus DEM [39] and the 1998 INEGI DEM [33], 1999 ASTER DEM [34], and 2000 SRTM DEM [35]. This procedure generated elevation change detection maps and allowed for the correct delineation of excavation and waste material accumulation zones.

In addition, pixel-by-pixel excavation and fill volumes, as well as the total volumes for the area of interest, were calculated. The grid method was applied to calculate the volume (Equations (5)–(7)), which consists of calculating the area of each pixel and multiplying it by the excavation thickness (negative sign) or fill (positive sign). This method, adapted from [20,42], provided a quantification of the volumetric changes associated with mining-induced relief alterations.

∆ Elevations = Recent DEM − Oldest DEM,

Pixel area = (DEM resolution)2,

Volume = Pixel area × ∆ Elevations,

The negative values of delta elevation were interpreted as excavation zones, while positive values corresponded to fill zones. These equations allowed for pixel-by-pixel estimation of excavation and fill volumes across the study area, ensuring accurate quantification of topographic changes resulting from mining activities.

2.2.4. Evaluation of Data Reliability

The validation of the results obtained was conducted by visually comparing the Landsat 5 and 8 images with the DEM. The positional and altimetric accuracy of the relief changes was also evaluated by generating three relief change maps using the different DEMs, which allowed for the calculation of the pixel-by-pixel standard deviation and an average standard deviation for the entire study area and volume.

2.2.5. Generation of Final Maps of Terrain Alterations

Finally, cartographic products were generated to represent the main relief alterations induced by mining, including comparative maps of Landsat images, elevation difference maps, and volume maps. The maps were generated from the collected dataset and processed using different algorithms in QGIS v3.40.5 software. This methodology represents an efficient, replicable, and low-cost alternative to traditional field methods and constitutes a strategic tool for the continuous monitoring of the morphological impact in regions affected by mining activities.

3. Results

3.1. Vertical Error, Standard Deviation, and Mean Square Error for the Different DEMs

The ALOS, ASTER, and SRTM DEMs were compared with the INEGI DEM on a pixel-by-pixel basis, and then the average across all pixels was obtained. Table 2 presents a summary of the results for the mean vertical error, mean standard deviation, and mean square error.

Table 2.

Mean vertical error, mean standard deviation, and mean square error for the ALOS, ASTER, and SRTM DEMs with the INEGI DEM.

The ASTER-INEGI and SRTM-INEGI DEMs present mean vertical errors (MEs) close to zero (1.259 m and 1.272 m, respectively), showing strong altimetric agreement. In contrast, the ALOS DEM displays a significant negative mean vertical error (−14.420 m), reflecting a systematic bias associated with differences in elevation reference surfaces. The standard deviation (SD) and root mean square error (RMSE) further support this pattern: ASTER (SD = 8.560 m; RMSE = 8.652 m) and SRTM (SD = 6.372 m; RMSE = 6.498 m) present moderate variability and adequate alignment for the study area, whereas ALOS (SD = 5.685 m; RMSE = 15.501 m) combines relatively low dispersion with pronounced vertical bias. This behavior justifies the exclusion of the ALOS DEM from the final analysis.

3.2. Detection of Physical Changes in the Mining Area Using Satellite Images and DEMs

3.2.1. Detection of Changes in Satellite Images

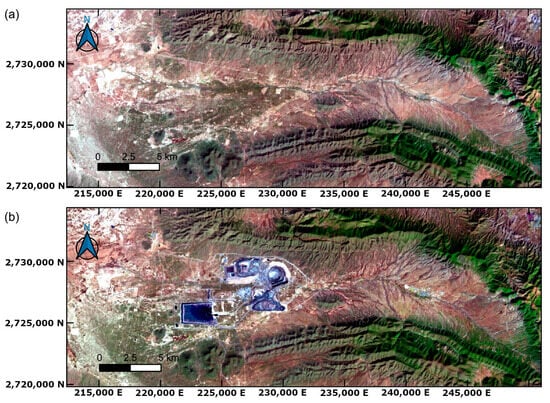

To identify physical changes induced by mining activities in the Mazapil region, false-color composites of multispectral bands were employed. Bands 5, 4, and 3 of Landsat 5 (1998) and bands 6, 5, and 4 of Landsat 8 (2014) were used. This spectral configuration is widely recognized for vegetation analysis, detection of exposed surfaces, and identification of water bodies (Figure 3). In these composites, vegetation is shown in various shades of green, urban areas and bare soil are displayed in shades of pink, and water bodies are represented in black and light blue [40].

Figure 3.

(a) Combination of bands B5 (SWIR 1), B4 (NIR), and B3 (red) from Landsat 5 imagery acquired on 09/02/1998 [28]. (b) Combination of bands B6 (SWIR 1), B5 (NIR), and B4 (red) from Landsat 8 imagery acquired on 05/02/2014 [32].

From these satellite images, the area covered by the tailings dam was measured at 4941 km2, the area of a pit was measured at 3931 km2, and the total area of the different mounds of waste material was measured at 7502 km2.

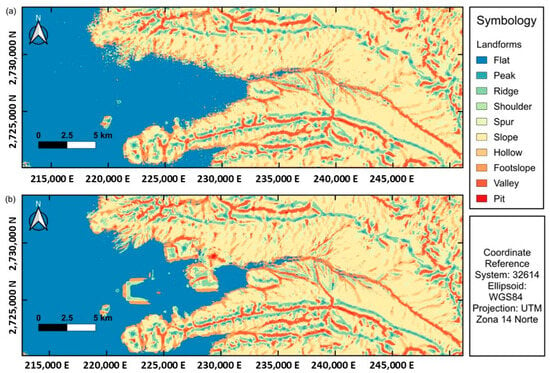

3.2.2. Detection of Relief Changes Using Multitemporal DEM

The detection of mining-induced relief alterations was conducted by classifying relief types for the years 1998 and 2014, comparing pre- and post-mining conditions. The method applied was based on the approach proposed in [41], which uses a computer vision algorithm to calculate Geomorphons (landforms) and their associated geometry. For this study, multiple tests were conducted with a variable search radius, and the best results were obtained using an outer radius of 30 units, an inner radius of 15 units, and a flatness threshold of 2°. This configuration resulted in the classification of the terrain into the following relief types: flat, peak, ridge, shoulder, spur, slope, hollow, toe of slope, valley, and pit [41].

As illustrated in Figure 4, in 1998, the study area was dominated by flat surfaces and gentle slopes, with minimal evidence of anthropogenic alteration. However, the 2014 classification reveals the appearance of large depressions (pits) in the central sector, accompanied by the formation of artificial mounds visible as newly developed ridges and shoulders, resulting from excavation activities and spoil deposition. These transformations are particularly evident in the vicinity of the open-pit mine, where the flat areas have been replaced by extensive depressions, and the surrounding terrain has been reshaped into raised spoil piles. These changes are of such magnitude that they are clearly detectable from space, demonstrating the ability of remote sensing and a Geomorphons-based classification to capture large-scale geomorphological transformations.

Figure 4.

(a) Landforms prior to mining activity derived from the 1998 INEGI DEM. (b) Landforms after mining activity generated from the 2014 Copernicus DEM.

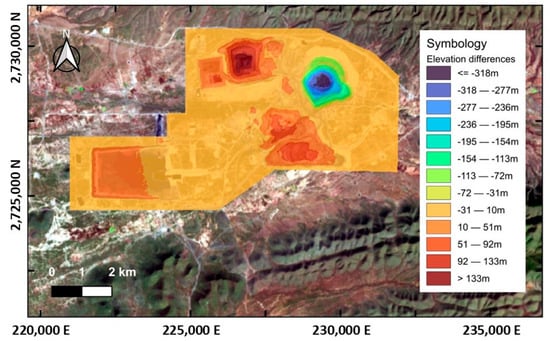

3.2.3. Detection of Elevation Changes Using Multitemporal DEMs

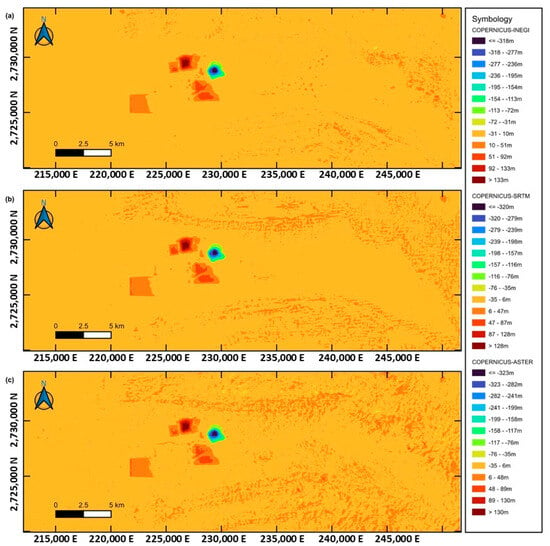

To detect mining-induced land elevation changes, multitemporal DEMs obtained from diverse sources were used. The procedure consisted of performing pixel-by-pixel algebraic subtraction between the 2014 Copernicus DEM and three historical DEMs: the 1998 INEGI DEM, 1999 ASTER DEM, and 2000 SRTM DEM. This analysis allowed us to identify the accumulated altimetric differences between 1998 and 2014 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Elevation differences between (a) the 2014 Copernicus DEM and the 1998 INEGI DEM, (b) the 2014 Copernicus DEM and the 1999 SRTM DEM, and (c) the 2014 Copernicus DEM and the 2000 ASTER DEM.

Figure 5 shows consistent spatial patterns of relief alteration, directly associated with areas of intense mining activity. Negative elevation differences, reaching −318 m with Copernicus-INEGI, −320 m with Copernicus-SRTM, and −323 m with Copernicus-ASTER, are represented in blue, green, and yellow shades, showing deep excavations such as open-pit mines. Conversely, positive elevation changes, up to +128 m in Copernicus–SRTM, +133 m in Copernicus–INEGI, and +130 m in Copernicus–ASTER, are shown in orange and red tones, corresponding to waste rock piles and tailings dams created during mining operations.

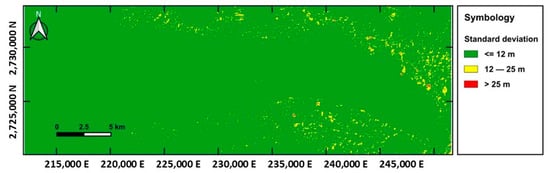

3.3. Evaluation of the Reliability of Elevation Differences Through Standard Deviation Analysis

To assess the reliability and spatial consistency of the elevation difference data, three topographic change maps were generated for the DEM pairs Copernicus–INEGI, Copernicus–ASTER, and Copernicus–SRTM (Figure 5). This redundancy provided a robust comparative basis between DEMs derived from diverse sources and spatial resolutions. The variability was quantified using pixel-by-pixel standard deviation (SD) calculations across the three different maps. For this analysis, the Copernicus–INEGI model was considered the “reference dataset” due to its higher spatial resolution and generation from aerial photogrammetry supported by field-based topographic control, thereby ensuring superior cartographic accuracy. Based on this reference, the standard deviation map shown in Figure 6 was produced.

Figure 6.

Standard deviation map of the Copernicus–INEGI, Copernicus–ASTER, and Copernicus–SRTM DEM comparisons.

The map reveals that most of the study area is characterized by SD values ≤ 12 m (green), which correspond primarily to flat or gently sloping surfaces, where the three DEMs exhibit strong altimetric agreement. Moderate SD values, between 12 and 25 m (yellow), are observed in areas with intermediate slopes, while the highest SD values > 25 m (red) are sparsely distributed and concentrated in mountainous areas, especially along ridgetops and steep slopes. This spatial distribution shows that the greatest altimetric discrepancies between DEMs are associated with steep topographic gradients, where interpolation and sensor-related geometric errors are most likely to occur. Finally, the average of all pixels in the standard deviation map was calculated, resulting in an average SD of ±3.6 m.

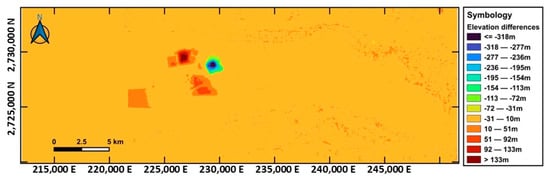

3.4. Generation of the Final Maps

3.4.1. Average Map of Topographic Alterations in the Mining Area

To reduce the uncertainty associated with differences between digital elevation models (DEMs) derived from various sources, an average map of topographic alterations was generated for the study area. This map was produced by calculating the pixel-by-pixel arithmetic meaning of the three elevation difference maps previously obtained, namely, Copernicus-INEGI, Copernicus-ASTER, and Copernicus-SRTM, which are presented in Figure 5.

The result of this integration is shown in Figure 7, where the cumulative average elevation differences between 1998 and 2014 are represented. The color scale is sequential, where dark tones (violet and blue) indicate the greatest reductions in elevation (≤−320 m), corresponding to deep excavation zones, while orange and red tones represent increases in elevation (>+129 m), associated with mine waste accumulation or tailings dam construction.

Figure 7.

Average elevation difference map derived from the Copernicus, INEGI, ASTER, and SRTM DEMs.

As can be seen, the areas with the most intense topographic changes are concentrated in the middle part of the map, where the main pits and mining deposits are found. These zones show maximum excavation depths of −361 m, showing a considerable volume of material removed from the subsurface during the analysis period. In contrast, artificially elevated regions, with a maximum increase of +170 m, are found and are linked to waste rock storage zones.

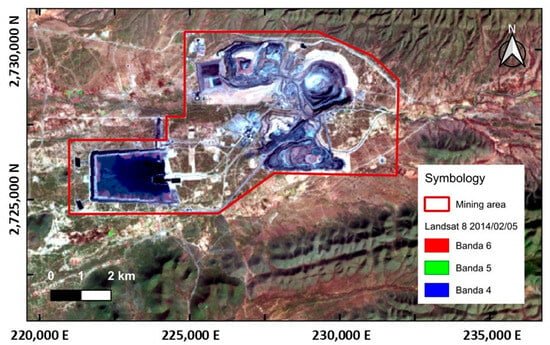

3.4.2. Delimitation of the Active Mining Area

Complementarily, the active mining activity polygon was delineated based on the visual interpretation of the Landsat 8 satellite image obtained on 5 February 2014 (Figure 8). This polygon was traced using the visible boundaries of open-pit mines, tailing dams, artificial water bodies, and haul roads. The overlay of this mining zone on the altimetric analysis products allowed for the spatial validation of the correspondence between the areas showing the greatest topographic alterations and the geographic footprint of industrial mining.

Figure 8.

Map of the mining area over Landsat 8 imagery from 2014.

3.4.3. Elevation Changes Within the Mining Footprint

To isolate only the topographic changes directly associated with mining activity, the average elevation difference map was cropped using the polygon corresponding to the delimited mining area as a mask (Figure 8). The results are presented in Figure 9, which shows only the elevation changes that occurred within the mining perimeter.

Figure 9.

Map of terrain alterations within the mining area.

Figure 9 shows substantial transformations in the natural terrain. Areas shaded from dark blue to yellow represent deep excavations, with elevation losses greater than −333 m relative to the original terrain, while areas ranging from orange to deep brown correspond to waste deposits, where an elevation increase of more than +152 m is recorded. These values confirm a drastic modification of the landscape, consistent with the removal and accumulation patterns characteristic of large-scale open-pit mining.

Table 3 presents quantitative data on the area affected by elevation changes within the mining zone. The deep excavation area covers 2.587 km2, the moderately or undisturbed areas cover 29.281 km2, and the area affected by mining waste dumping is 12.632 km2.

Table 3.

Dominant characteristics by elevation range, area, and percentage.

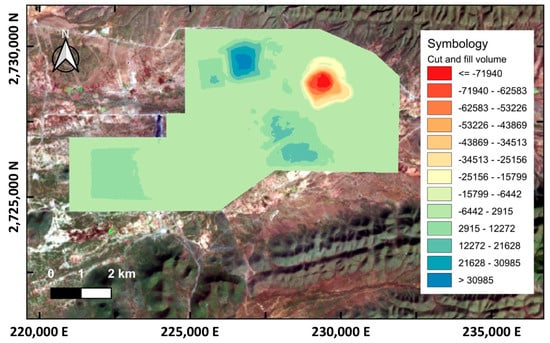

3.4.4. Calculation of Excavation and Filling Volumes Within the Mining Area

Based on the average map of relief alterations, the total volume of excavated material (cut) and accumulated material (fill) within the mining polygon was calculated. The procedure involved computing the volume of each pixel by multiplying its area by the corresponding elevation difference. This approach was adapted from methodologies proposed in [20,42]. The spatial result of the volume calculation is presented in Figure 10, showing volumetric variations distributed within the mining area, expressed in cubic meters per pixel.

Figure 10.

Map of excavation and fill volumes within the mining area.

The highest excavation zones are concentrated in the northeast sector of the polygon, reaching unit volumes greater than −71,940 m3 per pixel, while the largest fill values exceed +30,985 m3 per pixel in tailings dam and deposition platform areas. Subsequently, a summation of all negative (excavation) and positive (fill) pixel values yielded a total excavation volume of 413,524,124 m3 and a total fill volume of 431,194,785 m3. To incorporate the uncertainty associated with the elevation differences used in the calculation, an average standard deviation of ±3.6 m (obtained in Section 3.3) was considered. From this, an estimated volumetric standard deviation of ±810 m3 was calculated as the expected variability threshold in the volumetric estimates per pixel (Table 4).

Table 4.

Volumetric calculation of excavation and fill within the mining footprint.

4. Discussion

Detecting land cover and land use changes using satellite imagery is a technique that has been widely used in various research projects [43,44,45,46]. Therefore, this study used multitemporal imagery to detect land cover and land use changes. For example, the image in Figure 3a from 9 February 1998 shows natural vegetation and soil cover due to limited mining activity in the study area. In contrast, the image in Figure 3b from 5 February 2014 shows a marked transformation of the landscape. Large areas of bright pink and light blue dominate the central part of the image, corresponding to tailing dams, artificial water bodies, and active mining areas.

Multitemporal DEMs were used to detect landform changes, as Landsat images do not provide terrain elevation information. Therefore, different landform classes were obtained according to the classification in [41] between 1998 and 2014. This allowed for the observation of anthropogenic changes in the landscape and can assist in the planning of rehabilitation of affected lands.

These landform changes were measured through elevation changes between 1998 and 2014, using the multitemporal DEMs in Figure 5. The maximum negative elevation differences were −361 m, represented in shades of blue, green, and yellow, associated with deep excavations. On the other hand, the maximum positive elevation changes were +170 m, presented in orange and red hues, corresponding to waste rock piles and tailing dams. Similar alterations have been documented in other mining regions around the world. These include those reported in [12], where topographic changes greater than −250 m were detected at the Geita gold mine in Tanzania using multitemporal DEM differences. Similarly, [10] reported elevation variations between −258 m and +162 m in Inner Mongolia associated with large-scale open-pit mining. The results obtained in Mazapil and elsewhere around the world reinforce the validity of the method and reveal its applicability to diverse mining sites.

These results clearly illustrate the physical impact of open-pit mining on the local topography in less than two decades. The magnitude of the detected altimetric differences shows substantial volumes of removed material, which not only reshapes the original landscape but also has the potential to change hydrological processes, erosion dynamics, and surface runoff patterns.

To assess the reliability of the detected altimetric differences, the standard deviation (SD) of the three generated maps was calculated. The generated SD map shows that the largest altimetric discrepancies between the DEMs are associated with steep topographic gradients, where interpolation, geometric, and sensor-related errors are more likely to occur. The average SD for the entire study area was ±3.6 m, a value considered statistically low for regional-scale elevation change studies. Previous evaluations of the SRTM DEM have reported vertical errors of ±10 m for lowlands and up to ±36 m in mountainous regions [47]. Similarly, the ASTER DEM shows errors ranging from ±7 m to ±26 m depending on the elevation and topography [48]. The accuracy of DEMs varies considerably depending on the terrain type and product used, so it is essential to consider these margins of error when interpreting and using the data in scientific or land management applications.

From the three elevation difference maps obtained, an average elevation difference map was created to smooth out possible local errors present in the individual models and improve the spatial representation of actual topographic changes. This approach has been used in previous studies with similar purposes. For example, [49] compared and examined the accuracy of six freely available global DEMs (ASTER, AW3D30, MERIT, TanDEM-X, SRTM, and NASADEM) in four geographic regions with different topographic and land-use conditions. They used high-precision local elevation models (LiDAR and Pleiades-1A) as reference models. They estimated the accuracy by generating error raster’s by subtracting each reference model from the corresponding global DEM and calculated descriptive statistics such as the mean, median, and root mean square error (RMSE) for this difference.

As not all relief changes correspond to mining activities, the mining area was delimited by a polygon, covering approximately 44.5 km2 and encompassing all associated mining infrastructure. In particular, the tailings dam covers almost 4.9 km2, while the main excavation area of the pit occupies approximately 2.5 km2. This spatial correlation reinforces the validity of the altimetric change detection results, demonstrating that the areas of greatest elevation loss and gain accurately correspond to the operational footprint of mining activities.

After delineating the mining area, the volume of excavation and fill was calculated. The method used has been validated in other international studies on open-pit mining. For example, [50] conducted a study in Central Java Province, Indonesia, to measure the extent of minerals and calculate the extracted volumes using a more ecological approach. Drones (unmanned aerial vehicles) and DEMs were used to measure and calculate the volumetric properties of the minerals, yielding volume deviations of ±768 m3. For this reason, a certain degree of error in volume calculations is normal, and they are suitable for some uses but not for others.

5. Conclusions

The applied methodology proved effective in detecting and quantifying relief alterations in an active mining area through the integration of satellite imagery and multitemporal DEMs. It was possible to clearly identify excavation zones greater than 333 m and embankments greater than 152 m, covering an affected area of 15,219 km2; calculate volumes of excavated material of 413.524 million cubic meters and fill of 431.194 million cubic meters; and generate reliable geospatial products, even without access to the mine. This demonstrates the robustness of the approach for the remote monitoring of large-scale mining landscapes.

Based on the obtained results, we can state that the objectives were largely met, as not only were relief alterations detected, but also the affected areas, the depth and altitude of the alterations, and the excavation and embankment volumes were measured remotely.

The proposed methodology is limited for measuring relief changes and classifying landforms due to the availability of DEMs for a specific date, as well as their resolution and accuracy. Therefore, relief change measurements can only be made for dates determined by DEM availability. Furthermore, the lack of access to active mines limits in situ measurements. These limitations should be considered when implementing this methodology in other regions or at other scales.

However, Landsat satellite imagery offers temporal coverage of 7 or 14 days. Therefore, with these images, it is possible to detect changes in the ground and topography for every year from 1975 to the present. This gives imagery a temporal advantage over DEMs. However, DEMs have the advantage of providing elevation data, which allows us to calculate cut and fill thicknesses and excavation volumes.

Despite these limitations, the approach is particularly suitable for open-pit mines, where relief changes are larger and more visible from satellite sensors. The application of the methodology is recommended for areas where the relief changes are greater than ±3.6 m in elevation, as smaller elevation differences may not be detected with DEMs.

The integration of remote sensing and GIS offers a replicable and low-cost tool for the remote environmental assessment of mining landscapes. These methodologies can be implemented to characterize watersheds, landscapes, and geotechnical risk models in future work. Furthermore, the multitemporal analysis demonstrated the ability to monitor changes over time in mining areas, urban areas, and soil. These findings suggest that the technique can be adapted for continuous monitoring of mining’s secondary impacts.

The findings of this research are expected to contribute to a comprehensive understanding of mining-related landscape transformations. They will provide a replicable and cost-effective methodology to support the management and planning of mining activities. Furthermore, they will support evidence-based environmental planning and enable long-term landscape restoration planning in mining-affected regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.-C. and A.G.C.-M.; methodology, S.D.-C. and A.G.C.-M.; validation, C.F.B.-C., E.D.M.-V., and V.I.R.-A.; formal analysis, C.O.R.R. and L.A.P.-T.; investigation, S.D.-C. and A.G.C.-M.; data curation, S.D.-C. and A.G.C.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.-C. and A.G.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, S.D.-C. and A.G.C.-M.; visualization, E.D.M.-V. and V.I.R.-A.; supervision, A.R.-T. and S.I.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Council for Humanities, Sciences and Technologies (CONAHCYT) of Mexico for the scholarship awarded to Master of Science Saúl Dávila Cisneros to pursue doctoral studies and conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| SPOT | Satellite Pour l’Observation de la Terre |

| ASTER | Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| INEGI | National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

| ALOS | Advanced Land Observing Satellite |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

References

- Werner, T.T.; Bebbington, A.; Gregory, G. Assessing Impacts of Mining: Recent Contributions from GIS and Remote Sensing. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seloa, P.; Ngole-Jeme, V. Community Perceptions on Environmental and Social Impacts of Mining in Limpopo South Africa and the Implications on Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2022, 19, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M. Environmental Impacts of Mining: Monitoring, Restoration, and Control, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-003-16401-2. [Google Scholar]

- Laker, M.C. Environmental Impacts of Gold Mining—With Special Reference to South Africa. Mining 2023, 3, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Huante, P.; Rincón, E. Restauración de Minas Superficiales En México; SEMARNAT: Zapopan, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khobragade, K. Impact of Mining Activity on Environment: An Overview. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2020, 10, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiwumi, F.A.; Butler, D.R. Mining and Environmental Change in Sierra Leone, West Africa: A Remote Sensing and Hydrogeomorphological Study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 142, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charou, E.; Stefouli, M.; Dimitrakopoulos, D.; Vasiliou, E.; Mavrantza, O.D. Using Remote Sensing to Assess Impact of Mining Activities on Land and Water Resources. Mine Water Environ. 2010, 29, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, A.; Trybała, P.; Głąbicki, D.; Buczyńska, A.; Owczarz, K.; Bugajska, N.; Kozińska, P.; Chojwa, M.; Gattner, A. Application of Remote Sensing, GIS and Machine Learning with Geographically Weighted Regression in Assessing the Impact of Hard Coal Mining on the Natural Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Song, C.; Liu, K.; Ke, L. Integration of TanDEM-X and SRTM DEMs and Spectral Imagery to Improve the Large-Scale Detection of Opencast Mining Areas. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.W. Use of Remote Sensing and GIS in a Risk Assessment of Gold and Uranium Mine Residue Deposits and Identification of Vulnerable Land Use. PhD Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Emel, J.; Plisinski, J.; Rogan, J. Monitoring Geomorphic and Hydrologic Change at Mine Sites Using Satellite Imagery: The Geita Gold Mine in Tanzania. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 54, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.S.; Yucel, M.A.; Baba, A. Change Detection and Visualization of Acid Mine Lakes Using Time Series Satellite Image Data in Geographic Information Systems (GIS): Can (Canakkale) County, NW Turkey. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 4311–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Leopoldino, J.; dos Anjos, C.S.; Simões, D.P.; Fernandes, L.F.R. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of the Collapse of the Tailings Dam in Brumadinho, Brazil. Rev. Agrogeoambiental 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, L.; Zhao, L.; Niu, R. Automatic Identification and Dynamic Monitoring of Open-Pit Mines Based on Improved Mask R-CNN and Transfer Learning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Sedighi, A.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Kiavarz, M.; Homaee, M.; Arsanjani, J.J.; Makki, M.; Naimi, B.; Alavipanah, S.K. A Historical and Future Impact Assessment of Mining Activities on Surface Biophysical Characteristics Change: A Remote Sensing-Based Approach. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza Ramos, I.A.; Pech Canché, J.M.; Escobar León, M.C. Externalidades Ambientales Generadas Por La Unidad Minera Peñasquito, Mazapil, Zacatecas, México. 2021. Available online: https://cdigital.uv.mx/server/api/core/bitstreams/3da78d55-fb1a-40d1-a612-05a5d911b417/content (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mulková, M.; Popelková, R. Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Development of Mining Landforms Using Aerial Photographs: Case Study from the Ostrava–Karviná Mining District. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2024, 32, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimbye, Z.E.; Loggenberg, K. A Scoping Review of Landform Classification Using Geospatial Methods. Geomatics 2023, 3, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, W.; Breach, M. Engineering Surveying, 6th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, B.F.; Slattery, D. Surveying with Construction Applications; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghilani, C.D.; Wolf, P.R. Elementary Surveying. An Introduction to Geomatics, 13th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Facciolo, G.; De Franchis, C.; Meinhardt-Llopis, E. Automatic 3D Reconstruction from Multi-Date Satellite Images. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1542–1551. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.-J.; Tseng, C.-W.; Tseng, C.-M.; Liao, T.-C.; Yang, C.-J. Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-Acquired Topography for Quantifying Typhoon-Driven Landslide Volume and Its Potential Topographic Impact on Rivers in Mountainous Catchments. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, I. Corrected Precision of Topographic Measurements by Radar Interferometry. TechRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010; INEGI: Mazapil, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Marco Geoestadístico Integrado, Diciembre 2021; INEGI: Mazapil, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo Neri, R.A. El Impacto Social de La Megaminería En Mazapil, Zacatecas. Context. Latinoam. 2022, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Fernández, L.Á. Métodos de Detección de Cambios En Teledetección 2017. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/entities/publication/adfaa657-89f5-4300-ba18-9111e3b7011a (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Angeles, G.R.; Geraldi, A.M.; Marini, M.F. Procesamiento Digital de Imágenes Satelitales. Metodologías y Técnicas; Bahia Blanca, Argentina, 2020; ISBN 978-987-86-4773-9. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352544576_PROCESAMIENTO_DIGITAL_DE_IMAGENES_SATELITALES_METODOLOGIAS_Y_TECNICAS_2020 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Earth Resources Observation and Science Center. Landsat 4-5 Thematic Mapper Level-1, Collection 2; Earth Resources Observation and Science Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Resources Observation and Science Center. Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager/Thermal Infrared Sensor Level-1, Collection 2; Earth Resources Observation and Science Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Continuo de Elevaciones Mexicano y Modelos Digitales de Elevación; INEGI: Mazapil, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- ASA/METI/AIST/Japan Spacesystems and U.S. Team ASTER DEM Product 1999. Available online: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/documents/434/ASTGTM_User_Guide_V3.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Earth Resources Observation and Science Center. Digital Elevation-Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 1 Arc-Second Global; Earth Resources Observation and Science Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Observation Research and Application Center. ALOS Data Users Handbook; Revision, C., Ed.; Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA): Tokyo, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus. ESA Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (CDSE) 2023. Available online: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- USGS Landsat 8 (L8) Data Users Handbook 2019. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions/landsat-8-data-users-handbook (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Blanchard, S.D.; Rogan, J.; Woodcock, D.W. Geomorphic Change Analysis Using ASTER and SRTM Digital Elevation Models in Central Massachusetts, USA. GIScience Remote Sens. 2010, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS. What Are the Band Designations for the Landsat Satellites? 2025. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-are-band-designations-landsat-satellites (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Jasiewicz, J.; Stepinski, T.F. Geomorphons—a Pattern Recognition Approach to Classification and Mapping of Landforms. Geomorphology 2013, 182, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.; Dan, W. Study on Calculation of Earthwork Filling and Excavation Based on ModelBuilder. Sci. J. Intell. Syst. Res. Vol. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, M.; Tariq, A.; Anwar, M.M.; Khan, A.M.; Arshad, F.; Mumtaz, F.; Farhan, M.; Zhang, L.; Zafar, A.; Aziz, M.; et al. Monitoring of Land Use–Land Cover Change and Potential Causal Factors of Climate Change in Jhelum District, Punjab, Pakistan, through GIS and Multi-Temporal Satellite Data. Land 2021, 10, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashala, M.J.; Dube, T.; Mudereri, B.T.; Ayisi, K.K.; Ramudzuli, M.R. A Systematic Review on Advancements in Remote Sensing for Assessing and Monitoring Land Use and Land Cover Changes Impacts on Surface Water Resources in Semi-Arid Tropical Environments. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, B.E.; Kafy, A.-A.; Samuel, A.A.; Rahaman, Z.A.; Ayowole, O.E.; Shahrier, M.; Duti, B.M.; Rahman, M.T.; Peter, O.T.; Abosede, O.O. Monitoring and Predicting the Influences of Land Use/Land Cover Change on Cropland Characteristics and Drought Severity Using Remote Sensing Techniques. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 18, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuh, Y.G.; Tracz, W.; Matthews, H.D.; Turner, S.E. Application of Machine Learning Approaches for Land Cover Monitoring in Northern Cameroon. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 74, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggel, C.; Schneider, D.; Miranda, P.J.; Granados, H.D.; Kääb, A. Evaluation of ASTER and SRTM DEM Data for Lahar Modeling: A Case Study on Lahars from Popocatépetl Volcano, Mexico. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008, 170, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A.; Welch, R.; Lanh, H. Mapping from ASTER Stereo Image Data:DEM Validation and Accuracy. J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2003, 5, 256–370. [Google Scholar]

- Uuemaa, E.; Ahi, S.; Montibeller, B.; Muru, M.; Kmoch, A. Vertical Accuracy of Freely Available Global Digital Elevation Models (ASTER, AW3D30, MERIT, TanDEM-X, SRTM, and NASADEM). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allobunga, S.; Putri, R.; Siamashari, M.; Julita, I.; Fathoni, A.; Dwiriawan, H. The Mined Volume Calculation in the Traditional Mining Area by Using the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Approach in the Observation Area of CV. Sinergi Karya Solutif, Patikraja District, Banyumas Regency, East Java Province, Indonesia. J. Earth Mar. Technol. JEMT 2022, 2, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).