Abstract

Research on families with a child with Down syndrome (DS) focused primarily on the impact on parents, with less attention to siblings, yet typically developing siblings are particularly important for individuals with DS as they play a unique role in the family and often become their sibling with DS’s primary caregivers. One of the central aspects in sibling dynamics is acceptance, an area that has largely been ignored in research to date. The current study examined variables that predict typically developing siblings’ acceptance of their brother/sister with DS, focusing on the internal resources of optimism and sense of coherence (SOC), and the potential mediating role of social support and emotions towards the sibling. Functionality of the brother/sister with DS was explored as a moderating variable. Participants included 306 Israeli typically developing siblings (201 sisters, 105 brothers) ranging in age from 18 to 27 (M = 21.54, SD = 2.50). Participants reported their sibling’s independent functioning as higher or lower independence. The results showed that both social support and negative emotions towards the brother/sister mediated the relations between optimism and acceptance and SOC and acceptance. Functionality of the brother/sister with DS moderated these relations, such that acceptance was more strongly predicted by negative emotions when the sibling was low-functioning. The study’s findings emphasize the importance of social support and emotions as mediators between the personal resources of optimism and SOC, with functionality as a significant moderator. As individuals with DS have varying levels of functionality, it is necessary to take this variable into consideration and appropriately adapt support for typically developing siblings. Further, examining acceptance and how it may be predicted by personal resources lends itself to practical insights regarding supporting siblings and promoting sibling relationships.

1. Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is one of the most common chromosomal disorders around the world and is a neurodevelopmental condition associated with intellectual disability [1]. Children with DS have prominent physical characteristics, various physiological difficulties, and numerous cognitive and communication difficulties [2]. These unique characteristics of DS—distinct appearance, cognitive difficulties, and need for support—may make it challenging for them to adjust to society and form normative social relations. The research literature on families with a child with intellectual disabilities, including siblings of individuals with DS or other intellectual disabilities with unknown etiology, focuses mainly on the impact of the disability on the psychological health of parents, with less attention paid to siblings (e.g., Ref. [3]). However, sibling relations can be the longest throughout the life of an individual, and siblings influence each other at all stages of development throughout their lives [4]. Siblings are particularly important for individuals with intellectual disabilities, as they play a prominent role in the family and will often care for the sibling for much of their lives, in particular, by serving as a guardian after the parents cease their caring role [5,6]. Aiming to address this, the current study delved into typically developing siblings’ acceptance of individuals with DS. The following sections address the variables that may be associated with acceptance and research that demonstrates their importance.

1.1. Siblings of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

When a sibling is diagnosed with a disability, the typically developing sibling experiences intricate, and sometimes conflicting, emotions regarding the sibling’s disability [4]. Further, the dynamic within the family system is often complex, including difficulty relating to parents, exposure to challenging behaviors by the sibling with disability [7], and often, significant responsibility for individuals with intellectual disabilities [6,8]. Studies have similarly found that siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities take on numerous roles for their sibling including caregiving, friendship, advocate, and legal representative or guardian [9,10]. This role thus goes much beyond that of a typical sibling relationship.

Studies conducted on siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities have demonstrated that the typically developing siblings report various areas that impact their quality of life. One of the aspects that comes up frequently is the ambivalence of their relations with their sibling and the mixed impact of being a sibling to an individual with disabilities (e.g., Ref. [11]). On the one hand, there is evidence of increased risk for mental illnesses amongst siblings of individuals with intellectual disabilities, such as anxiety, depression, negative impact on social wellbeing, and increased interpersonal problems [12,13,14,15]. Additionally, siblings expressed negative emotions towards their brother/sister with disability and described moments of conflict, disagreement, or burden due to their responsibilities of taking care of the sibling [16]. On the other hand, it was found that siblings of individuals with intellectual disorders see themselves as more mature, tolerant, and empathic, with better social abilities than their peers as a result of their daily lives [17,18]. Mothers of children with DS and other disabilities reported better sibling relations than mothers of typically developing children [19]. Many siblings decide to fiercely maintain their relationship with their sibling with an intellectual disability, often involving commitment, responsibility, and love towards them. These siblings see relationships with their sibling with disability as a mutual space for growth and sharing [20,21]. Understanding the aspects that influence sibling relations can provide insight into what might promote sibling growth [22]. One of the central aspects in the sibling dynamic is acceptance.

1.2. Sibling Acceptance

Accepting an individual with a disability implies recognizing that the characteristics associated with the disability are an immutable part of who they are, not trying to change the individual, and understanding that they need to relate to the individual “as they are” [23]. Research on parents’ acceptance of a child’s disability has shown that greater acceptance was associated with greater positivity towards the child and better relations with the child [24,25]. Some research on siblings’ acceptance emerges from siblings of individuals with autism. This research indicates that acceptance is a process that develops over time, and is helped by greater understanding of the diagnosis and needs of the brother/sister with disability and improvements in communication with them [26,27]. In a systematic review, siblings’ acceptance of their brother/sister with intellectual and developmental disabilities helped in their adjustment, and parents’ positive views and acceptance influenced the siblings’ acceptance [10].

Given that acceptance can impact the nature of sibling relationships (e.g., Ref. [26]), with greater acceptance promoting more positive sibling relations, it is important to explore variables that may relate to acceptance. For example, a study by Alon [28] found that internal resources such as optimism and sense of coherence (SOC) predicted the acceptance of siblings with autism. The current study thus focuses on a number of variables that have been shown to relate to sibling relations and may influence acceptance, including variables relating to the typically developing sibling: internal resources (SOC, optimism), social support, and emotions towards the sibling, as well as the independent functioning (i.e., level of need for support) of the brother/sister with DS.

1.3. Sense of Coherence

SOC is considered a life orientation that enables people to identify and utilize the best resources to cope with various stressors in their lives [29,30]. Having a stronger SOC can help the individual perceive stressors as manageable and promote healthier adaptation [29]. The research literature supports the importance of SOC in physical and mental health, a more positive family environment, and adjustment to having a brother/sister with a disability [31,32]. A number of studies have shown that parents with a child with an intellectual disability reported lower SOC than a control group of parents with children without an intellectual disability [33,34]. Similarly, a study of Swedish parents of children with DS found that parents with higher SOC had lower levels of perceived stress [35]. To date, it seems that research on the SOC of siblings with DS is lacking. Yet, as evidenced from research on parents, SOC reflects a person’s ability to perceive life’s demands as meaningful, manageable, and comprehensible [29]. For siblings who play important roles in the lives of the sibling with DS, often also taking on primary caretaking roles, SOC is likely to shape their emotional experiences and their acceptance. As such, the current study explored how SOC relates to and impacts the acceptance of siblings with DS.

1.4. Optimism

Internal factors such as optimism—belief in positive future outcomes [36]—have been found to serve as a resilience factor against poor psychosocial outcomes such as depression, and helps individuals cope with caregiving stress in families with a child with disabilities [34,37,38]. This may be because more optimistic worldviews provide a sense of hope, meaning, and control over the situation in these families [39]. Recently, a study of Malaysian caregivers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities found that the use of optimism as a coping strategy was associated with better relationships, increased personal growth, and more positive perceptions [40]. Others also found that parents of children with intellectual disabilities who find positive aspects in caring for a child with intellectual disabilities related increased personal growth and strength [41]. Studies focused specifically on siblings of individuals with autism indicate that lower levels of optimism seem to relate to more negative perceptions of the impact of the child and higher levels have a protective value [42,43]. Although researched less extensively amongst siblings of individuals with DS, a study by [44] of typically developing siblings of individuals with autism or DS found that siblings who were less pessimistic regarding the future of individuals with DS had closer sibling relations. In light of the relation between optimism and more positive family outcomes, along with the potential protective ability of optimism, the current study examined whether optimism is related to siblings’ acceptance of their brother/sister with DS.

1.5. Social Support

Extensive research has shown the benefits of social support for the wellbeing and functioning of families of individuals with disabilities [45,46]. For example, perceived social support was negatively related with parenting stress among parents of children with DS in Nigeria [47]. Similarly, parents of children with DS reported that social support helped them cope with caregiving and emotional difficulties [48]. Greater perceived social support was also related to increased confidence of caregivers in their ability to provide care [49]. In terms of siblings, those who receive social support report feeling less alone and that they are not the only ones experiencing their situation [50]. Furthermore, amongst siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, greater perceived social support was associated with lower levels of stress [51], and lower perceived social support predicted poorer sibling outcomes [50]. In light of the importance of social support for siblings of individuals with disabilities, in the current study we explored the relations between social support and sibling acceptance.

1.6. Emotions Toward a Sibling with DS

Siblings of individuals with DS and other intellectual disabilities often experience mixed emotions towards their brother/sister with the disability. Some reported feelings such as guilt, happiness, helplessness, and stress [51,52]. Others related negative emotions such as jealousy, anxiety, shame, frustration, embarrassment, or sadness [3]. Compared to siblings of typically developing brothers/sisters, siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities showed fewer positive emotional attitudes [14]. At the same time, having a sibling with a disability positively impacted the typically developing sibling’s emotions, attitudes, and readiness to take an active part in caring for the brother/sister with a disability [53]. Similarly, siblings of individuals with DS considered the overall quality of their sibling relationships to be quite positive [6]. The current study examined the contribution of emotions towards the acceptance of a sibling with DS.

1.7. Level of Independent Functioning of the Sibling with DS

Aside from the variables that relate to the typically developing sibling, the nature of the disability itself may relate to the level of acceptance. For instance, siblings had lower levels of acceptance of their brother/sister with autism combined with intellectual disability compared to autism without intellectual disability [28]. Similarly, a lower level of functionality was associated with more negative feelings towards the brother/sister with a disability [54]. Roberts noted that the more severe the intellectual disability, the greater the impact on the typically developing sibling and their mental health [55]. Further, more challenging behaviors exhibited by the sibling with an intellectual disability was associated with more negative feelings [56]. There is a spectrum of capability for individuals diagnosed with DS, which includes independent functioning, mobility, and cognition [57]. Independence is an important and central variable in children’s functioning, as parents are concerned with the future independence of their child with DS [58]. The level of independence is also related to communication ability. Studies that explored the relations between functionality and sibling relations explored, for example, communication ability and its relation to relations with a sibling with DS [59]. Individuals with DS who have less independent functioning have greater support needs compared to those with more independent functioning. As such, level of independence may moderate the relations between variables such as social support, optimism, and emotions and acceptance.

1.8. Current Study

Given the prominent role that typically developing siblings play in the lives of their brother/sister with DS [15], the current study examined how personal resources (SOC, optimism), social support, and emotions towards the brother/sister relate to siblings’ acceptance of the individuals with DS. There is some evidence that social support may moderate the relation between optimism and more positive outcomes in families with a child with a disability [38,40]. Additionally, both SOC and social support have been shown to contribute to more positive outcomes, but a mediation model has not been explored in relation to siblings of individuals with disabilities. Further, emotions are a meaningful variable that not only have a focused effect, but rather serve as a broad influence on the siblings’ adjustment [8]. As such, this study examined whether social support and emotions mediate the relation between SOC and acceptance and between optimism and acceptance. Further, there is some suggestion that the level of independence—that is, the extent to which they need support—of the sibling with DS may moderate the relations between these variables. The model examined in the current study is presented in Figure 1. The study hypotheses are presented below:

Figure 1.

Proposed study model showing the hypothesized mediation paths from optimism and sense of coherence (SOC) to acceptance through perceived social support and emotions towards the brother/sister with Down syndrome, and the moderating role of perceived independence in the relation between negative emotions towards the sibling and acceptance.

- Personal resources (optimism, SOC) and social support will directly predict acceptance;

- Social support and emotions will mediate the relation between optimism and acceptance and between SOC and acceptance;

- Level of independence of the brother/sister with DS will moderate the relation between emotions and acceptance, with lower independence associated negatively between emotions and acceptance.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Study participants were 304 siblings of individuals with DS, including 201 sisters (66%) and 103 brothers (34%). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 27 (M = 21.54, SD = 2.50). Of the individuals with DS, 60% were boys and 40% were girls. Participants ranged in age from 5 to 38 years old (M = 14.98, SD = 6.6). Of the participants, 61.1% were single and 37.3% were married, and the remaining were divorced or separated. Regarding participants’ socio-economic status, this information was not specifically solicited, but given that the majority were students in higher education or in their mandatory army service, their SES was relatively low. Participants were asked to rank the level of independent functioning of their sibling with DS, taking their age into consideration, as independent or not independent. According to the participants’ report, the sibling with DS were high-independent (38%) or low-independent (62%).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Questionnaire

The 27-item demographic questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section included items relating to the participating sibling: age, sex, SES, education, and the like. The second section included items relating to the sibling with DS: age, sex, degree of independence, and living location.

2.2.2. Sibling Acceptance Questionnaire

Based on the original questionnaire [60], the 25-item Hebrew Siblings Acceptance questionnaire [61] examined the typically developing sibling’s level of acceptance of the sibling of their sibling with a disability (e.g., “I can openly discuss my sibling’s difficulties”, “I feel better when I tell people that my sibling has DS”). Participants rated the items on a scale of 1 = disagree completely to 5 = agree completely. Average scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of acceptance. Reliability for the current study was good, with Cronbach’s α = 0.81.

2.2.3. Optimism

We used the Hebrew version [62] of the Life Orientation Test [36] to examine optimism. This eight-item questionnaire measured participants’ expectations of future outcomes. Items were phrased in both positive (e.g., “I’m always optimistic about the future”) and negative terms (e.g., “Things never work out the way I wanted them to”). Items were ranked on a scale between 1 = disagree and 5 = agree very much. After reversing negative items, the scores were averaged, such that higher scores reflected greater optimism. Reliability for the current study was sufficient, with Cronbach’s α = 0.76.

2.2.4. Sense of Coherence

We used the Hebrew version [63] of the Sense of Coherence questionnaire [64] to examine SOC. This 16-item questionnaire examined how much a person believes that the stimuli in their environment are predictable, controllable, and that the events in their life will work out for the best (e.g., “Do you think most things work out in the end?”). Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5. Reliability for the current study was good, with Cronbach’s α = 0.86.

2.2.5. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

We used the Hebrew version [65] of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [66]. This 12-item scale explored participants’ subjective view of how much social support they receive from three sources—family, friends, and meaningful others (e.g., “I received the help and emotional support that I need from my family”). Participants scored items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Scores were averaged, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of support. Reliability for the current study was good, with Cronbach’s α = 0.89.

2.2.6. Emotions Towards Siblings

The Hebrew 20-item Emotions Towards Siblings questionnaire [67] examined the composition and intensity of participants’ emotions towards their sibling with DS. Respondents ranked the extent of the particular emotion on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much. Five items examined positive emotions (e.g., “How much do you experience these feelings towards your sibling with DS: devotion, empathy...”). The other 15 items examined negative emotions (e.g., “How much do you experience these feelings towards your sibling with DS: anger, jealousy, indifference...”). We reversed the scores of the items relating to positive emotions to form an overall measure of emotions towards the sibling, where higher scores indicated more negative emotions towards the sibling with DS. Reliability of the questionnaire was sufficient, with Cronbach’s α = 0.79.

2.3. Procedure

The study received ethics approval by the ethics board of Michlalah Jerusalem (with no approval number). Participants were recruited through social network platforms for siblings of individuals with DS such as Facebook groups, WhatsApp groups, and Israeli internet forums. Inclusion criteria were that the typically developing participants would be in emerging adulthood (between the ages of 18–30), and that the brother/sister with DS would have no comorbid diagnoses (such as autism). The study and its goals were explained in writing to each sibling who expressed an initial interest in participating. Participants completed a consent form wherein standards of ethics and confidentiality were guaranteed. Participants received the questionnaires digitally or by hand. The majority (95%) completed them digitally, and the researcher collected those completed by hand. The questionnaire was generally completed in roughly 20 min. Participant received no remuneration for their participation.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). Descriptive analyses were conducted for the primary study variables (acceptance, SOC, optimism, social support, emotions), followed by Pearson correlations. There was nearly no missing data within the dataset and in cases where there were, imputation methods were used based on majority responses. In order to determine whether there were differences in the study variables based on the independence/support needs of the sibling with DS, t-tests for independent samples were conducted. Finally, to examine the mediation analysis and the moderated mediation analyses, the Hayes [68] process was used, Model 87, with the bootstrapping approach (5000 resamples to estimate the 95% confidence intervals) for the significance of effects.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

The results of the analysis of the primary study variables are presented in Table 1. On average, participants were above the midpoint of the scale (ranging from 1 to 5) in their levels of acceptance, SOC, optimism, and social support, but were below the midpoint of the scale in their negative emotions towards their brother/sister with DS.

Table 1.

Means, SD, and correlations between primary study variables.

As can be seen in Table 1, Pearson correlations between the variables revealed statistically significant positive relations between acceptance of the brother/sister with DS, SOC, optimism, and social support. Further, significant negative relations emerged between negative emotions towards the brother/sister and the remaining variables. In other words, greater acceptance was associated with higher SOC, optimism, and social support, and lower negative emotions towards the brother/sister with DS.

3.2. Differences Based on Functionality

Results of the t-tests examining differences based on the brother/sister with DS’s independent functioning are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Differences in study variables between siblings of high-/low-independent functioning individuals with DS.

As can be seen, statistically significant differences emerged in acceptance, SOC, optimism, and negative emotions, but not for support. That is, siblings of brother/sisters with more independence (i.e., lower need for support) had greater levels of acceptance, higher SOC, and optimism, and lower levels of negative emotions compared to siblings of brothers/sisters with lower independence (higher support needs).

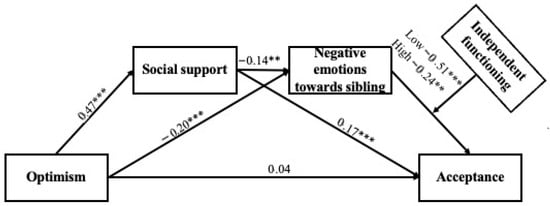

3.3. How Optimism Relates to Acceptance

To examine how optimism relates to acceptance, the process model was conducted. The results, presented in Table 3 and Figure 2, reveal that support was positively and significantly predicted by optimism, negative feelings towards the sibling were negatively and significantly predicted by support and optimism, and acceptance was predicted positively and significantly by support. The interaction between emotions towards the brother/sister and independence was significant, reflecting moderation by independent functioning. That is, acceptance was predicted negatively and significantly by emotions: the relation was more negative for participants with a less independent brother/sister and less negative (but still statistically significant) for siblings with more independent brothers/sisters.

Table 3.

Mediation model between optimism and acceptance via support and emotions, moderated by independent functioning.

Figure 2.

The mediation of the relationship between optimism and acceptance, showing both the direct path from optimism to typically developing siblings’ acceptance of their brother/sister with Down syndrome and the indirect paths through perceived social support and negative emotions towards the sibling. The figure also shows the moderating role of functionality on the relations between negative emotions towards the sibling and acceptance. (**: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001).

The path between optimism and acceptance through social support was statistically significant (B = 08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.03–0.14]) (B = regression coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval). Further, the path between optimism and acceptance through emotions towards the brother/sister was statistically significant for participants with a less independent brother/sister (B = 0.11, SE = 0.03, CI [0.05–0.16]) and for those with a more independent brother/sister (B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, CI [0.02–0.10]). Finally, the path between optimism and acceptance through support and emotions was statistically significant for participants with a low-independence sibling (B = 0.03, SE = 0.01, CI [0.01–0.06]) and with a high-independence sibling (B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, CI [0.00–0.04]). In other words, the higher the optimism, the higher the support and lower the levels of negative emotions, and the higher the support, the lower the emotions and higher the acceptance. Lower levels of negative emotions are associated with higher levels of acceptance, both for participants with a low-independence brother/sister and those with a high-independence brother/sister.

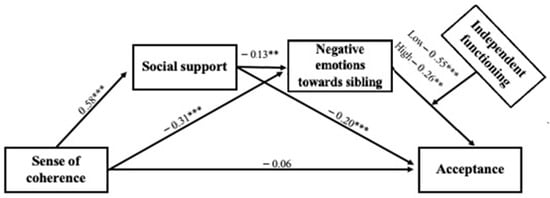

3.4. How SOC Relates to Acceptance

To examine how SOC relates to acceptance, the process model was run. The results, detailed in Table 4 and Figure 3, reveal that social support was positively and significantly predicted by SOC. Negative emotions towards the brother/sister with DS were predicted negatively and significantly by social support and SOC, and acceptance was predicted positively and significantly by social support.

Table 4.

Mediation model between SOC and acceptance via support and emotions, moderated by independent functioning.

Figure 3.

The mediation of the relationship between sense of coherence (SOC) and acceptance, showing both the direct path from SOC to typically developing siblings’ acceptance of their brother/sister with Down syndrome and the indirect paths through perceived social support and emotions towards the sibling. The figure also shows the moderating role of independent functioning on the relations between negative emotions towards the sibling and acceptance. (**: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001).

The interaction between negative emotions towards the sibling and independence was significant, reflecting moderation by independent functioning. In other words, acceptance towards the brother/sister with DS was significantly negatively predicted by emotions, with this relation more negative for participants with a sibling who was low-independence, and less negative (but still significant) for participants with a sibling who was high-independence.

The mediation between SOC and acceptance via social support was statistically significant (B = 0.115, SE = 0.034, 95% CI [0.05–0.18]). In addition, the mediation between SOC and acceptance via negative emotions towards the brother/sister with DS was significant for participants who had a sibling who was low-independence (B = 0.170, SE = 0.04, CI [0.10.26]) and a sibling who was high-independence (B = 0.081, SE = 0.033, CI [0.03–0.16]). Finally, the mediation between SOC and acceptance via social support through emotions towards the sibling was significant for both participants with a low-independence sibling (B = 0.041, SE = 0.016, CI [0.01–0.08]) and for those with a high-independence sibling (B = 0.019, SE = 0.03, CI [0.00–0.05]). In other words, the higher SOC, the greater social support and lower levels of negative feelings towards the brother/sister with DS. The lower the negative emotions, the higher the acceptance of the sibling, both for participants with a low-independence sibling and those with a high-independence sibling.

4. Discussion

The current study examined typically developing siblings’ acceptance of their brother/sister with DS. It was hypothesized that optimism and SOC would directly predict acceptance, and that this relation would be mediated by social support and emotions towards the sibling with DS, while the independent functioning of the sibling with DS would moderate these relationships. The hypothesis that optimism and SOC would directly predict acceptance was not supported. Instead, the relationship between these variables was significantly mediated by social support and emotions. The hypothesis that independence of the sibling with DS would moderate these relations was supported, such that acceptance was predicted by emotions towards the sibling, with a negative relation for participants with a low-independence sibling and lower levels of negative emotions for those with a high-independence sibling. Similarly, acceptance was significantly predicted by SOC, mediated by social support and emotions, and moderated by independence.

4.1. The Important Contribution of Social Support

Both SOC and optimism are considered resources internal to the individual, with SOC helping the individual cope with stress factors, while optimism is a resilience factor for challenging situations, such as having a sibling with a disability. Nonetheless, the results showed that SOC and optimism predict acceptance, but only through social support. Numerous studies demonstrated the positive and influential role of social support for families with individuals with disabilities, and particularly for siblings in these families. It was also found that caregivers who perceive greater social support are more confident in their ability to integrate their caregiving demands into daily life [49]. Research on SOC and optimism in families with a child with DS is quite limited and focused primarily on parents [34,37,38]. The current study thus expands the research to include sibling relations, and reinforces the important contribution of social support. That is, even having the internal resources of optimism and SOC was not sufficient to directly predict sibling acceptance, but rather, this was mediated by social support. Perhaps the social support enables the siblings to harness their internal resources and utilize them to show greater acceptance of their sibling with DS. This highlights the need to strengthen social support amongst siblings, particularly as they often take up the caretaking role over time [6]. Moreover, programs that promote social support might also aim to focus on personal resources as a way to further strengthen the individual.

4.2. Emotions as a Lens

Results showed that emotions mediated the relations between optimism and acceptance and between SOC and acceptance. These results spotlight the overarching impact of emotions. Throughout their lives, siblings encounter various experiences that may generate complex emotions towards their sibling with a disability [8]. Emotions then serve as a central factor that frame siblings’ psychological adjustment [3]. To date, however, emotions have largely been examined in the context of outcomes, as opposed to a mediator. The current study’s results seem to indicate that emotions serve as a lens through which experiences are viewed and interpreted. That is, experiences that are perceived and interpreted as being more positive then proceed to shape the typically developing siblings’ acceptance [28]. When experiences are tinged with a more negative light, this then continues to negatively impact acceptance, possibly reducing this important aspect of the sibling relationship. In this light, siblings should be given numerous opportunities to express and process the varied and complex emotions that they experience. Therapeutic support can provide the space for siblings to undergo this process and receive legitimization and support.

The relations between emotions and acceptance was moderated by independence of the brother/sister with DS. Specifically, negative emotions towards the brother/sister with DS depend on the level of independence of the sibling with DS, such that for a low-independence sibling, the higher the levels of negative emotions, the lower the level of acceptance. This relation was weaker for participants with a high-independence sibling. This is in line with previous research on siblings of individuals with autism [28], and extends it to siblings of individuals with DS, with an emphasis on independent capabilities, since we did not ask about cognition, understanding communication, etc., but about the ability to function independently. Greater dependence, which indicates higher support needs, seems to pose specific challenges for the typically developing siblings. When the sibling with DS requires more assistance in daily functioning, this often translates into greater caregiving demands, more frequent responsibilities, and higher emotional strain for the typically developing sibling [69]. These kinds of demands may make it more difficult for typically developing siblings to maintain positive emotional experiences, complicating the process of acceptance.

4.3. Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the current study’s results. Data were collected solely through self-report questionnaires. While this method is widely used and appropriate for assessing personal experiences, self-report measures may be subject to biases such as social desirability and common method variance. Additionally, quantitative research allows for a larger sample size that may allow for greater generalizability than qualitative research. However, incorporating additional data collection tools such as structured interviews, diaries, or observational methods in future studies may provide a deeper understanding of sibling acceptance processes by focusing on lived experiences, emotional nuances, and family dynamics that quantitative measures may not fully capture. Additionally, the study relied solely on typically developing siblings’ reports, including their assessment of the level of independence of the sibling with DS. Because this is measured by a single sibling-reported item, it may not fully capture the complexity of functional independence, which is multidimensional and often assessed by parent report or formal functional scales [70]. Future research would benefit from using multiple informants, including parents or spouses, and using validated measures of adaptive functioning to provide a more accurate and comprehensive assessment [15,46,71]. The age range of the individuals with DS was quite broad, and future studies may consider exploring whether age plays a role in sibling acceptance. Future research may also consider other variables as mediators/moderators of the relationships that were explored. This may include family, parenting, stress levels, TDS’ personality characteristics, as well as other characteristics of the sibling with DS, such as behavior problems, other psychiatric diagnoses, etc. It would also be helpful to examine acceptance at different ages, as this is a developmental issue. Finally, echoing Kovshoff [72]’s call, there is a need for future research exploring sibling relations in the context of other disabilities.

5. Conclusions

The results of the current study yield a number of implications relating to siblings of brothers/sisters with DS. The findings highlighted the impact of the independence of the sibling with DS on the relations between emotions and acceptance. As not all siblings are the same, it is important to find appropriate methods to help typically developing siblings to cope with having a sibling with DS with varying levels of independent functioning, particularly those with greater support needs. Acceptance of a sibling with DS can be an important element of sibling relations, and serve as a basis for later years when they become the primary caretakers [52]. As acceptance seems to be lower for siblings of lower independence, they may be at greater risk for mental and physical health issues and should have increased support and adapted guidance [5]. Further, the study examined mediating and moderating variables that had previously been explored, mainly in the context of outcome variables, highlighting the study’s uniqueness. Additionally, the inclusion of acceptance and investigating how it is predicted by personal resources lends itself to practical insights regarding ways of supporting siblings of individuals with DS. There is a need to further explore the experiences of siblings of individuals with DS, both in research and in practice.

Funding

This research was supported by the Shelem Foundation. The author did not receive any funding or financial support to cover the Article Processing Charge (APC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Michlalah Jerusalem College (date of approval: 19 February 2022). Ethics approval reference: Michlalah Jerusalem College Institutional Ethics Committee approval for the research proposal submitted to the Shelem Foundation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request, due to ethical restrictions and confidentiality considerations.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the participants and their families for their cooperation and openness throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no financial or non-financial competing interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

This article employs person-first language (e.g., “individuals with Down syndrome”) to reflect the ethical, cultural, and academic norms of disability research in Israel, emphasizing the person before the diagnosis. This choice aligns with institutional ethical standards and the inclusive research approach adopted by the author.

References

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhan, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, L. Global, regional, and national burden and trends of down syndrome from 1990 to 2019. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 908482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwhaibi, R.M.; Omer, A.B.; Khan, R.; Albashir, F.; Alkuait, N.; Alhazmi, R. Assessment of the Correlation between the Levels of Physical Activity and Technology Usage among Children with Down Syndrome in the Riyadh Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10958. [Google Scholar]

- Yaldiz, A.H.; Solak, N.; Ikizer, G. Negative emotions in siblings of individuals with developmental disabilities: The roles of early maladaptive schemas and system justification. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 117, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A. What is ‘sibling support’? Defining the social support sector serving siblings of people with disability. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 291, 114466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, D.; D’Eath, M.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M. Health and well-being of sibling carers of adults with an intellectual disability in Ireland: Four waves of data. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2023, 51, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, L.; Schneider, B. Family support for (increasingly) older adults with Down syndrome: Factors affecting siblings’ involvement. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2023, 27, 315–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, N.K.; Hastings, R.P.; Bailey, T. Behavioural adjustment of children with intellectual disability and their sibling is associated with their sibling relationship quality. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2023, 67, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldin, L.; Saxena, M. Mutual exchange: Caregiving and life enhancement in siblings of individuals with developmental disabilities. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2232–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, A.; Smith, M.M. Sibling involvement in interventions for children with a disability: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 4579–4589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muries-Cantan, O.; Schippers, A.; Giné, C.; Blom-Yoo, H. Siblings of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review on their quality of life perceptions in the context of a family. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 69, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levante, A.; Martis, C.; Del Prete, C.M.; Martino, P.; Primiceri, P.; Lecciso, F. Siblings of persons with disabilities: A systematic integrative review of the empirical literature. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 28, 209–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, R. Psychosocial Stress Among Siblings of Individuals with Disabilities: The Interplay of Religiosity, Gender, and Cultural Background. Religion 2025, 16, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, R.; Ungar, W.J. Impact of growing up with a sibling with a neurodevelopmental disorder on the quality of life of an unaffected sibling: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommantico, M.; Parrello, S.; De Rosa, B. Adult siblings of people with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities: Sibling relationship attitudes and psychosocial outcomes. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 99, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, B.; Magiati, I.; Roberts, R.; Pellicano, E.; Glasson, E.J. Risk and resilience factors impacting the mental health and wellbeing of siblings of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions: A mixed methods systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 98, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Seo, H.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A. Confirmatory factor analysis of a family quality of life scale for Taiwanese families of children with intellectual disability/developmental delay. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 55, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Long, K.A. Family impact and adjustment across the lifespan: Siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In APA Handbook of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Clinical and Education Implications: Prevention, Intervention, and Treatment; Glidden, L.M., Abbeduto, L., McIntyre, L.L., Tassé, M.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.O.; Allred, D.W.; Mandleco, B.; Freeborn, D.; Dyches, T. Caregiver burden and sibling relationships in families raising children with disabilities and typically developing children. Fam. Syst. Health 2014, 32, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelsma, F.; Caubo-Damen, I.; Schippers, A.; Dane, M.; Abma, T.A. Rethinking FQoL: The dynamic interplay between individual and family quality of life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, R.A.; Seabra-Santos, M.J. “I would like to have a normal brother but I’m happy with the brother that I have”: A pilot study about intellectual disabilities and family quality of life from the perspective of siblings. J. Fam. Issues 2022, 43, 3148–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findler, L.; Vardi, A. Psychological growth among siblings of children with and without intellectual disabilities. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.T.; Williamson, R.L.; Casey, L.B.; Stockton, M.; Elswick, S. Sibling relationships when one sibling has ASD: A preliminary investigation to inform the field and strengthen the bond. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.; McGill, P. The sibling’s perspective: Experiences of having a sibling with a learning disability and behaviour described as challenging. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2019, 24, 138–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yetkin, A.İ.; Aksoy, V. Maternal acceptance–rejection and mother–child interaction in Turkish mothers of children with developmental disabilities. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2019, 31, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjy, R.S.; Fielding, A.; Falkmer, M. “It’s better than it used to be”: Perspectives of adolescent siblings of children with an autism spectrum condition. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Hanna, P.; Jones, C.J. A systematic review of the experience of being a sibling of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, R. Predicting typically-developing siblings’ acceptance of their sibling with ASD during emerging adulthood. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2022, 99, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 36, 725–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M. The sense of coherence in the salutogenic model of health. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmak, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lingstrom, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Espinosa-Medina, A.; Lopez-Martinez, C.; Orgeta, V. Sense of coherence, burden and mental health in caregiving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 242, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einav, M.; Margalit, M. Sense of coherence, hope theory and early intervention: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Teach. Train. 2019, 10, 64–75. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/60055 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Al-Krenawi, A.; Graham, J.R.; Al Gharaibeh, F. The impact of intellectual disability, caregiver burden, family functioning, marital quality, and sense of coherence. Disabil. Soc. 2011, 26, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichler, K.; Lewandowska-Walter, A.; Trawicka, A. Communication in the family and the sense of coherence in mothers of children and young people with disability. Acta Neuropsychol. 2017, 15, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedov, G.; Anneren, G.; Wikblad, K. Swedish parents of children with Down’s syndrome: Parental stress and sense of coherence in relation to employment rate and time spent in child care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2002, 16, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985, 4, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, H.L. Coping with caregiving: Humor styles and health outcomes among parents of children with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 104, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, É.; McMahon, J.; Gallagher, S. Optimism and benefit finding in parents of children with developmental disabilities: The role of positive reappraisal and social support. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 65, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Baxter, D.; Rosenbaum, P.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bates, A. Belief systems of families of children with autism spectrum disorders or Down syndrome. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2009, 24, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamir Singh, P.S.; Azman, A.; Drani, S.; Mohd Nor, M.I.H.; Che Ahmad, A. Navigating the terrain of caregiving of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Importance of benefit finding and optimism. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beighton, C.; Wills, J. How parents describe the positive aspects of parenting their child who has intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 1255–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, C.M.; McGregor, C.; Hough, A. Self-reported stress among adolescent siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder and Down syndrome. Autism 2019, 23, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.S. Sibling Warmth, Coping, and Distress Among Emerging-Adult Siblings of Individuals with and Without Autism. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Seltzer, M.M. Siblings of individuals with autism or Down syndrome: Effects on adult lives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2007, 51, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhofer, S.M.; Orm, S.; Haukeland, Y.B.; Fredriksen, T.; Wakefield, C.E.; Fjermestad, K.W. A systematic review of social support for siblings of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 126, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, B.; Magiati, I.; Roberts, R.; Skoss, R.; Glasson, E.J. Psychosocial interventions and support groups for siblings of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions: A mixed methods systematic review of sibling self-reported mental health and wellbeing outcomes. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 26, 143–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyedibe, M.C.C.; Ugwu, L.I.; Mefoh, P.C.; Onuiri, C. Parents of children with Down Syndrome: Do resilience and social support matter to their experience of carer stress? J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, P.; Kara Uzun, A. Stressful experiences and coping strategies of parents of young children with Down syndrome: A qualitative study. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2023, 36, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, S.D.; Souders, M.C.; Aryal, S.; Pinto-Martin, J.A.; Deatrick, J.A. A comparison of family management between families of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and families of children with Down Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2024, 38, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, S.; O’Leary, R.; Hayden, N.K.; Baumbusch, J. A realist review of programs for siblings of children who have an intellectual/developmental disability. Fam. Relat. 2022, 2022, 2083–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, C.M. Self-reported guilt among adult siblings of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 124, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, A.; Siman Tov, A. Involvement, Readiness for Primary Caregiving, Loneliness, and Self-Efficacy: A Comparison between Adult Sisters and Brothers of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2024, 71, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, M.E.; Lerner, M.D. Intervention and support for siblings of youth with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, H.E.; Carlton, M.E.; Carter, E.W. Social connections among siblings with and without intellectual disability or autism. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 58, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.L. A review of the literature on siblings of individuals with severe intellectual and developmental disabilities. Int. Rev. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 60, 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort, C.; Paradis, A.; Rivard, M.; Dewar, M. Siblings of individuals with intellectual disabilities or autism: A scoping review using Trauma Theory. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 3482–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, K.; Haugen, K.; Torres, A.; Santoro, S.L. Description of daily living skills and independence: A cohort from a multidisciplinary Down syndrome clinic. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.E.; Burke, M.M. Future planning among families of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 17, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymouri, R.; Najafi Fard, T.; Amaraei, K.; Bahrami, E.; Ghorbani Kalkhajeh, S.; Yousefi, S. Analyzing the Effectiveness of Communication Skills on Sibling Relationship of Adolescents with Down Syndrome. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2022, 20, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, T. The Relationship Between Mother and Child with a Handicap as a Function of Guilt Feelings and Coping Styles. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig-Gorfinkel, A. Self-Esteem, Parents’ Cooperative Coping Style, Sex of the Healthy Other, and Healthy Siblings’ Acceptance of Their Siblings with Intellectual Disability. Thesis for Psychology Certification, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel, 2004. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner, M.; Ben-Zur, H. Coping with a national crisis: The Israeli experience with the threat of missile attacks. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 14, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, Y.; Florian, V.; Kravitz, S. Sense of coherence: Socio-demographic characteristics and perception of mental and physical health. Psychology 1991, 2, 119–125. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Statman, R. Women’s Adaptation to Their Retirement from the IDF. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, D.; Solomon, Z. In the shadow of schizophrenia: Impact of the disease on siblings. Soc. Wellbeing 2003, 1, 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford publication: New Yor, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Leane, M. “I don’t care anymore if she wants to cry through the whole conversation, because it needs to be addressed”: Adult siblings’ experiences of the dynamics of future care planning for brothers and sisters with a developmental disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.V.; Balla, D.A. Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, 2nd ed.; Pearson Assessments: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kruithof, K.; IJzerman, L.; Nieuwenhuijse, A.; Huisman, S.; Schippers, A.; Willems, D.; Olsman, E. Siblings’ and parents’ perspectives on the future care for their family member with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: A qualitative study. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 46, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovshoff, H.; Cebula, K.; Tsai, H.-W.J.; Hastings, R.P. Siblings of children with autism: The Siblings Embedded Systems Framework. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2017, 4, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).