Abstract

People with disability are disproportionally affected by disasters due to layers of marginalisation from an interaction of personal, social, economic, political, and environmental factors. These intersect with gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation, and result in additional discrimination and social exclusion that reinforce inequality and stigma. There has been little focus on the intersection of disability and gender in disability-inclusive disaster risk reduction (DIDRR) in high-income countries. This paper reports on a scoping review exploring the intersection of gender and sexual identity and disability in disaster in both peer-reviewed and grey literature. Building greater awareness of the specific needs of marginalised groups such as women, gender, and sexually diverse people into DIDRR will reduce the disproportionate impacts of disaster on these groups.

1. Introduction

People with disability make up 15% of the world’s population [1] and are disproportionally affected by disasters due to layers of marginalisation [2,3,4].

While there has been little research exploring the experiences of people with disability during and after disaster [5], there is an expanding body of research exploring how to reduce impact by facilitating mainstream agencies to include people with disability in disaster risk reduction [6,7]. This is a challenge as people with disability are a heterogeneous group, who experience barriers in diverse ways due to long-term physical, mental, intellectual, and sensory impairments [8]. Disaster vulnerabilities result from an interaction of personal and social, economic, political, and environmental factors. These intersect with gender and gender identity, sexual orientation, age, race, culture, and religion, and result in additional discrimination and social exclusion) [8,9].

Gartrell et al. [10] found there are additional and unequal impacts of disasters on women with disability compared to other people with disability. These include higher fatality rates, greater risk of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), impacts from culturally defined gender roles (i.e., caretaking roles that lead to being stranded at home during a disaster, with less mobility during and after disaster), and having less financial independence and lower physical fitness to enable various forms of escape. However, the recognition of women’s vulnerabilities in disaster has led to more research and disaster policy to ensure their needs are met, but there has been minimal focus on other gender and sexually diverse identities, and more intersectional research beyond the binary is required for a more comprehensive understanding of gendered experiences of disaster [11,12]. For other marginalised groups such as lesbian, gay, trans, queer, and other sexually or gender diverse (LGBTQ+) people, disasters can result in further exclusion or marginalisation. For example, government policies and non-government organisation (NGO) practices can lead to a loss of personal and communal spaces that expose them to verbal and physical abuse and stigmatisation [13]. Kolkawski-Hayner and Goldin [14] argue that women and LGBTQ+ individuals with disability such as acquired brain injury are more likely to be negatively impacted in a disaster, including COVID-19, due to violence, a lack of family support and community resources, and higher rates of poverty and social isolation. This leads to more symptoms of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbance as the intersection of other bases of discrimination such as gender and sexual identity often reinforce inequality, stigma, and social expectations [2].

While programmes to support disability inclusive disaster risk reduction (DIDRR) have been developing, there has been little focus on the intersection of disability and gender in DIDRR in high-income countries. This paper reports on a scoping review exploring the intersection of gender, sexual identity, and disability in disaster in both peer-reviewed and grey literature. More specifically, we wanted to identify the key challenges faced by people with disability who are women, men, gender, and sexually diverse before, during and after disasters, and the identified recommended strategies for informing the development of training resources tailored to individuals affected by disasters and those involved in the emergency management sector in Australia. These resources aim to enhance the awareness and understanding of the unique needs of these marginalized groups within the context of disaster risk reduction and response.

2. Review Process/Methods

Scoping review was the chosen method to describe the extent, range, and characteristics of literature as it addresses a specific topic or field of study in order to summarise the findings from a diverse body of knowledge and to aid in planning interventions or future research [15].

2.1. Review Questions and Inclusion Criteria

During the pre-planning phase, a study protocol was developed following the PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines [16] and the JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) Methodological Guidelines [17] for conducting a scoping review. The protocol was formulated to address the following questions:

- What is known about the intersectionality of gender, sexual identity, and disability in disaster?

- What are the key challenges faced by people with disability who are women, men, and gender and sexually diverse before, during, and after disasters?

- What are the identified enablers/recommended strategies (from whose perspective) for the inclusion of this cohort in disaster risk reduction?

The scoping review employed broad criteria of participants, concept, and context (PCC) to enable the inclusion of a wide range of evidence and knowledge. Participants included people with disability who are women, men, and gender and sexually diverse. The core concept examined in this scoping review is the intersectionality of disability and gender, disability, sexual identity, and disaster. The context of this review is the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries as this aligns with the Australian context, making the findings relevant and transferable to our region. This review focuses on exposures related to natural hazards and pandemics while excluding terrorism, war, biological/chemical threats, and cyber-attacks.

2.2. Evidence Sources and Search Strategies

The sources of evidence and knowledge included peer-reviewed empirical studies (such as experimental studies, observational studies, and cross-sectional studies), and grey literature (such as discussion papers, book chapters, and policy papers). The search for peer-reviewed empirical studies was conducted in Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, ProQuest, and Web of Science. The search for grey literature was conducted in international databases and websites that index resources from international organizations, including PreventionWeb, AskSource, DIDRRN, ReliefWeb, Natural Hazards Center, GOV.UK, Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (AIDR), and Disability Advocacy Resource Unit (DARU). Both qualitative and quantitative data published in English since 2010 were included. While the criteria were for empirical studies in OECD countries, initial searches revealed limited research that met the criteria. Given the nature of the grey literature, the criteria for grey literature were expanded to include all countries as limiting this to OECD countries would have produced more limited results.

Table 1 presents the search strings developed in consultation with a research librarian. A complete search strategy for empirical studies in Medline is included in the Supplementary Materials (File S1).

Table 1.

Search strings.

2.3. Screening and Study Selection

After removing duplicates, the empirical studies and grey literature retrieved from the databases and websites were imported into Covidence software for screening. Following the screening methods outlined in the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Guide (2020), two reviewers (F.N. and P.S.) conducted dual screening of 20% of peer-reviewed abstracts, with conflicts resolved by a third reviewer (K.J.C.). F.N. then screened the remaining 80% abstracts, and P.S. screened all excluded abstracts, with conflicts resolved by K.J.C. Then, F.N. and P.S. conducted further screening of full-text records. Three authors (P.S., M.V., and T.C.) screened the grey literature. All reviewers agreed on the final inclusion of empirical studies and grey literature. The reference lists of the studies included in the full-text screen were also searched for additional sources.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction followed the Cochrane Rapid Reviews guide. The first reviewer (F.N. for empirical studies and P.S. for grey literature) extracted data using a charting framework consisting of elements such as study information, methods, study focus, and key findings (see Table 2). The second reviewer (P.S. for empirical studies and F.N. for grey literature) checked for the correctness and completeness of the extracted data. Any conflicts or differences in opinions, such as whether a study or report met the criteria, were resolved through discussion among three reviewers (F.N., P.S., and K.J.C.).

Table 2.

Summary of sources and key findings.

Table 2.

Summary of sources and key findings.

| Author, Date, and Country of Population Studied | Study Title | Study Design/Type | Journal/ Source Location | Aims of Research | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gul et al., 2022 [18] Turkey | The Access of Women with Disabilities to Reproductive Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study | Qualitative | International Journal of Caring Sciences | To determine the access of women with disabilities to reproductive health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Challenges: Fear of COVID-19 infection, barriers accessing sexual and reproductive health services, communication difficulties, lack of family and social support. Recommendations: Nurses should take a role in the development of policies and efforts to ensure continuity in SRH services for women with disabilities. |

| Hannawi et al., 2022 [19] USA | Impact of COVID-19 pandemic-associated social changes on boys with moderate to severe autism | Quantitative | Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders | To assess the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting social changes on boys with autism spectrum disorder. | Challenges: Loss of services/therapies, difficulty adjusting to changes impacting behaviour, challenges with online learning, no social interactions. |

| Jordan et al., 2022 [20] USA | COVID-19 Pandemic: Mental Health in Girls With and Without Fragile X Syndrome | Quantitative | Journal of Paediatric Psychology | To examine the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among school-aged girls with Fragile X syndrome. | Challenges: Difficulty adjusting to changes and online learning increased anxiety, lack of social interaction. Recommendations: Learn new skills using technology, encourage coping skills and independence with a consistent daily routine. |

| Molony et al., 2022 [21] UK | Sound and Vision: Reflections on running a community- based group for men with learning disabilities online, during the pandemic | Qualitative/ reflection | British Journal of Learning Disabilities | To assist the men with learning disabilities to create new friendships and to cope (COVID-19 context) or recover from mental health problems via the sharing of interests and concerns, and to press for more helpful local services and inclusive communities. | Challenges: Reluctance to use technology, unstable internet connection/inadequate financial support, lack of services/therapies. Recommendations: Benefits of technology for virtual gatherings and sharing of resources, referral for speech and language assessment. |

| Platero et al., 2023 [22] Spain | Community responses to LGBT+ adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 confinement in Madrid | Qualitative | International Social Work | To explore the experiences of a group of LGBTQ+ people in Madrid coping with the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–May 2020). | Challenges: Increased control by others, barriers to sexual rights, fear of discrimination and increased anxiety. Lack of awareness regarging disability and LGBTQ+ community. Recommendations: Strategies to overcome anxiety use of online support programmes. |

| United Nations, 2020 [23] | Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19 | Policy brief: Reference to intersectionality including gender, women and girls in particular, pp. 6–8, 15. | DIDRRN | This policy brief highlights the impact of COVID19 on persons with disabilities and in doing so, outlines key actions and recommendations to make the response and recovery inclusive of persons with disabilities. While the brief contains specific recommendations focusing on key sectors, it identifies four overarching areas of action that are applicable for all. | Challenges: Persons with disabilities experiencing intersectional and multiple discrimination will carry a heavier burden of the economic and social consequences of the pandemic. Recommendations: A combination of mainstream and disability-specific measures are necessary to ensure systematic inclusion of persons with disabilities. Ensure the accessibility of information, facilities, services and programmes in the COVID-19 response and recovery. Ensure meaningful consultation with and active participation of persons with disabilities and their representative organizations in all stages of the COVID-19 response and recovery as well as accountability measures. |

| United Nations, 2018 [24] | Realization of the sustainable development goals by, for and with persons with disability: UN Flagship Report on Disability and Development | Report: Section E relates to gender pp. 124–150 | DIDRRN | This report represents the first UN system wide effort to examine disability and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda in all types of disaster. The report reviews data, policies, and programmes; identifies good practices; and uses the evidence it reviewed to outline recommended actions to promote the realization of the SDGs for persons with disabilities. | Challenges: Persons with disabilities, particularly women, children, and older persons with disabilities, are more vulnerable to exploitation, violence, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in the aftermath humanitarian crises, particularly refugees with disabilities, and experience multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination. Recommendations: persons with disabilities, including women and children with disabilities, should participate in decision-making processes and be active stakeholders at all stages of disaster response and humanitarian action, rebuilding, and inclusion in operational standards, and information should be provided in accessible formats. Awareness raising and capacity building of issues relating to marginalised groups is also important. |

| World Bank Group—Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), 2018 [8] | Five Actions for Disability-Inclusive Disaster Risk Management | Policy brief: Action 4 refers to needs of women, p. 13. | DIDRRN | Literature survey to identify actions relating to improving disability inclusive disaster risk management in all types of disasters. | Challenges: Women with disability face higher barriers during disasters and are at greater risk of gender-based violence. Recommendations: Collect data that is inclusive of persons with disabilities. |

| Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, 2022 [25] | Inclusion and disaster resilience Insights for gender and disability inclusive disaster-resilience-building | Resource/ brief report: Reference to disability and gender throughout report. | AIDR | To provide practical guidance for using the Zurich flood resilience measurement for communities (FRMC) to understand gender and disability dynamics and account for them in flood resilience-building interventions. | Challenges: Women and people with disabilities have difficulty accessing health care and have a lack of access to communication and resources. Recommendations: Inclusion-informed data collection using the flood resilience measurement for communities (FRMC) developed by the Zurich Flood Resiliance Alliance considers the roles, responsibilities, needs, and safety of all participants, understanding that these factors will be different due to intersecting identities and lived experiences. This includes accommodating the different needs of different genders, as well as those of people with disabilities and other marginalised groups during data collection. |

| Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, 2019 [26] | Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems (EWS): Experiences from Nepal and Peru | Report: Intersectionality with reference to disability throughout report. | ReliefWeb | To explore the connection between gender diverse individuals, including those with disability, and EWS and best practices to ensure that EWS are effective for all. | Challenges: The less economic, political, and cultural power women and gender minorities have before an event, the greater their suffering during and in the aftermath. DRR and EWS initiatives take place in locations where some groups have less power than others, where, in some cases, individuals or groups are deliberately marginalised. Recommendations: acknowledgement that gender is a critical consideration that requires gender analysis. A more ambitious EWS is gender transformative, aiming for an improvement over the status quo so that people of all genders can access, understand, and respond to effective early warning. |

| International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2018 [27] | Minimum standards for protection, gender and inclusion in emergencies | Guidance document: Intersectionality with reference to disability throughout the report. | ReliefWeb | To present Red Cross and Red Crescent staff, members and volunteers with a set of minimum standards for protection, gender, and inclusion (PGI) in emergencies. It aims to ensure that emergency programming provides dignity, access, participation, and safety for all people affected by all types of disasters and crises. | Recommendations: Conducting a gender and diversity analysis that must include the participation of women, girls, men, boys, and persons of other gender identities as well as individuals and groups based on age (children, adolescents, and older men and women); disability status (physical, sensory, and intellectual); persons with mental health disabilities; and ethnic, religious, or cultural minorities. Standards that include detailed actions are provided that aim to support dignity, access, participation, and safety. |

| CBM Global, 2022 [28] | An Approach to Disability-Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction—Based on Consultations with People with Disabilities in the Asia and Pacific Regions | Report: Reference to intersectionality including gender and women throughout. | PreventionWeb | To help disability-inclusive DRR become a reality, the Pacific Disability Forum (PDF), the International Disability Alliance (IDA), and CBM Global’s Inclusion Advisory Group worked together to conduct inclusive consultations across Asia and the Pacific, to seek the perspectives, experiences, and priorities of the diverse range of people with disabilities in relation to all types of disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. | Challenges: Women with disability reported being especially at risk, uncovering that that sexual harassment of young women and girls occurs in evacuation shelters. The study found that women and girls with disability experienced physical and sexual abuse when they sought to access hygiene facilities by themselves. |

| United Nations Women, 2020 [29] | Checklist for Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Disaster/Emergency Preparedness in the COVID-19 Context | Resource/ brief report: Reference to disability throughout report. | PreventionWeb | The document presents emerging gender-related issues in COVID-19 in Nepal and suggested actions to help prepare for an emergency. | Recommendation: Evacuation shelters are the same for women and gender minorities with disability. A number of specific actions are recommended supporting this. |

| World Bank, No date [30] | Designing Inclusive, Accessible Early Warning Systems (EWS): Good Practices and Entry Points | Report: Reference to disability, gender and women in particular throughout the report. | PreventionWeb | This paper provides entry points and good practices for designing more inclusive, accessible early warnings and is organized around the four key elements of effective end-to-end EWS. | Challenges: Gaps in disaster risk knowledge, e.g.:

|

3. Results

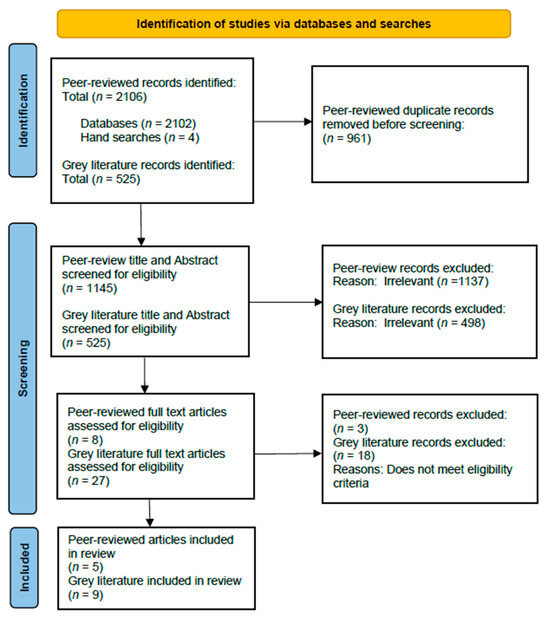

Our search strategy identified 2631 sources (peer-reviewed n = 2106; grey literature n = 525). Duplicates (n = 961) were removed, and the titles and abstracts of remaining sources were screened for eligibility (peer-reviewed n = 1145; grey literature n = 525) with a significant number excluded (peer-reviewed n = 1137; grey literature n = 498) due to not meeting inclusion criteria (for example, not addressing the intersectionality of disability and gender or disability and sexual identity). Full text appraisal resulted in five peer-reviewed studies and nine grey literature publications that were included in this scoping review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search and screening process.

An overview of the 14 sources used in this review are provided in Table 2, and the findings, challenges, and recommendations are detailed in the Discussion section below. The intersection of gender, sexuality, and disability in the context of disaster is not commonly reported. All five of the empirical studies that explored this intersection utilized COVID-19 as the disaster context, demonstrating a large gap in research exploring disability, gender, and sexual identity in the context of natural hazards. Three of the five studies used qualitative methods (focus groups and interviews) and two used quantitative methods (surveys). Each study had a very specific focus and inclusion criteria. For example, women with disability and access to sexual and reproductive health services [18], boys with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [19], men with learning disabilities [21], girls with Fragile X syndrome [20], and LGBTQ+ people with intellectual and developmental disabilities [22]. The grey literature that met the criteria included policy briefs and reports, predominately from the United Nations and the World Bank, that focused more broadly on disability inclusive disaster risk reduction in a variety of disasters, with two focusing specifically on the COVID-19 context.

4. Discussion

This review explored the literature for what is known about the intersection of gender, sexual identity, and disability in disaster, along with the challenges experienced and recommendations to support these groups. The review yielded a limited number of empirical studies and grey literature that were relevant to this review as many lacked a specific intersectional focus. This highlights the gaps in our current understanding of people with disability, diverse sexual orientation, and gender, as well as gaps in policy and practice. Furthermore, the literature presents the gender binary despite having sexually and gender diverse participants. A specific LGBTQ+ lens was difficult to identify in most of the studies. Some empirical studies were conducted in low-income countries and, although outside the criteria of this scoping study, were kept as resource literature.

The United Nations [24] acknowledges that people with disability are more vulnerable to violence, exploitation, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse following disasters, particularly if they are women, children, older persons with disability, and refugees with disability. Furthermore, in the COVID-19 context, the UN [23] identified that women with disability are at much higher risk of, and disproportionally affected by, domestic violence during lockdown measures. As identified in the previous literature [9,25], people with disability with multiple identities and characteristics, such as gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and age, among other factors, experience more immediate and longer-term impacts of the pandemic than the larger population [23].

Of the research findings reported, negative outcomes for participants were overwhelmingly noted, such as reduced social support, communications, and services during COVID-19 lockdowns, resulting in the exacerbations of emotional changes, self-harm, and problematic/aggressive behaviours [18,19,20]. All five studies reported participants having higher levels of fear of infection for themselves and their families, anxiety, insomnia, difficulty transitioning to, and coping with stay-at-home orders in relation to COVID-19 confinement. For LGBTQ+ people, there was an exacerbation of pre-existing risk factors, such as unemployment, poverty, less mobility and access to health care, and less opportunity for agency and control over their own lives. Furthermore, there was increasing fear of discrimination during the pandemic due to reports of bullying during this period, and a general lack of awareness relating to disability within the LGBTQ+ community [22]. For those of this group living in intensive cohabitation with family members, there was increased control with some participants having to be careful with how they interacted online within this environment due to privacy concerns and discrimination from family members regarding their sexual identity. The intersection of disability, gender, and sexuality resulted in family members treating the adult person with disability as a child, limiting their ability to explore their sexualities and gender identities. They felt that they were treated differently to other LGBTQ+ people due to their disability: “…there is an intersectional discrimination” [22].

4.1. Challenges Identified before, during and after Disaster

The most reported challenge in the peer-reviewed literature related to reduced social support for people with disability from family, friends, and neighbours due to COVID-19-related confinement and a lack of access to social and other activities. Furthermore, difficulties with communication were reported, for example, mask wearing negatively impacted the ability to communicate clearly, and poor internet connectivity or reluctance to use videoconferencing platforms limited online connectedness [18,19,20,21]. Hannawi et al. [19] found that boys with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experienced more difficulty sitting for extended periods and focusing on online classes, and this also affected their ability to maintain social connectedness via these means. Similarly, Jordan et al. [20] found that girls with Fragile X syndrome were frustrated with the transition to online learning and a lack of structure. Jorden et al. [20] referred to parents, and mothers in particular, reporting that anxious and highly communicative mothers inadvertently transferred their pandemic related worries to their daughters with disability. Such research regarding the interactions with male parents in this context is critical. Restricted social interactions also created more barriers to what existed pre-pandemic in relation to the sexual rights of LGBTQ+ people with disability [22].

Another challenge related to reduced access to transport, community-based supports/services, and health services/therapies, such as speech and language therapy and occupational therapy for people with disability during the pandemic restrictions [19,20,21]. For instance, Gul and Yagmur, [18] reported barriers for women with disability being able to access reproductive and sexual health services, along with health providers ignoring or demonstrating insensitivity towards them while seeking reproductive health interventions. Participants interpreted their needs as minor within the context of the “larger” pandemic problem: “…during the pandemic process, the COVID concern took precedence over everything. I tried to live my pain at home, I don’t care even if it’s [sic] sick. COVID is so bad.” (18 years old, orthopaedic disability) [18] (p. 1244) Participants also reported that they ignored their own reproductive health symptoms due to difficulty with mobility and accessing transport and health care, particularly if residing at distance from service providers: “If there was a problem before, I could go to the hospital thanks to my neighbour. But I didn’t want her to take me to my obstetrics during the pandemic. That would be very shameful and selfish.” (25 years old, visually impaired). [18] (p. 1246). This Turkish study may have a different cultural context to many high-income countries, and this raises culture as another issue of importance when considering the intersection of disability, disaster, gender, and sexual identity.

Access to services is also a problem in other disasters that result in internally displaced populations or people being forced to leave their countries. Women with disability remain responsible for caregiving roles but experience numerous and intersecting forms of discrimination and stigma that is compounded by racial discrimination and xenophobia. These can limit access to community support services and increase risk of violence [8,24], which reflects other findings [10,31,32].

Of note is the general lack of inclusion of gender and sexual diversity in policy and practice that would inform access to health and social services. According to the World Bank [30], gaps in disaster risk knowledge include a lack of data of vulnerable groups that is disaggregated by factors such as sex, gender, disability status, and age. There is also insufficient inclusion of these factors in disaster risk assessments, insufficient use of community-based co-production approaches to disaster risk reduction, with limited understanding of the specific needs of vulnerable groups who have unequal access to accessible formats for people with disability to disaster risk knowledge [30].

4.2. Enablers and Recommendations

Four of the peer-reviewed studies reported enablers and recommendations that can help in times of disaster to support people with disability who identify as gender and sexually diverse. Technology was the most prominent enabler for providing social support during the pandemic. Platero et al. [22] reported on an online support programme (Diversxs) that helped participants to cope with feelings of isolation, anxiety, insomnia, and stress. In addition to offering them training and access to adapted information, the programme helped participants to explore their sexuality and gender identity. The development of coping strategies to overcome anxiety included the avoidance of watching too many news stories about the pandemic and using the increased free time during the lockdown to reflect on their identities and to try and connect to like-minded people online [22]. Jordan et al. [20] recommended that enablers such as technology be used to develop new skills to maintain possible peer connections using communication via text message and phone calls, creating virtual social opportunities during stay-at-home orders. “…in nearly all arenas, technology consumption has allowed her to stay connected and express herself much more clearly than she tends to do orally.” [20] (p. 32). Moloney et al. [21] found that sharing of graphics, videos, and photographs to provoke discussion or illustrate a point was easier online than with face-to-face support groups, and that technology enabled the participation of men with disability who lived in isolated circumstances to be involved in virtual gatherings. Moloney et al. [21] recommended carer consultation and referral for a sensory and speech and language assessment for men who had sensory and ASD related difficulties and who had difficulty interacting with other people via online forums.

Other recommendations to minimize the emotional impact of the pandemic included using a consistent routine and encouraging independence in daily activities [20]. Gul and Yagmur [18] recommended that health professionals take a role in the development of policies and efforts that are inclusive of people with diverse gender and sexual identities to ensure that pre-disaster vulnerabilities are not exacerbated and that there is continuity of, and access to, health services for people with disability during and after the disaster.

The grey literature focused on both COVID-19 and disasters more generally. The UN [23] policy brief focused on COVID-19 and recommended that the inclusion of people with disability should be adopted as mainstream in response and recovery, including the development of accessible information, services, and programmes that are borne out of meaningful consultation and active participation by people with disability. Furthermore, the strengthening of awareness raising and capacity building of services and community with particular focus on women and girls with disability at risk of gender-based violence was noted. These strategies reflect the DIDRR work of Villeneuve [7], which emphasises a person-centred and capability-focused approach to disaster risk reduction.

Similar recommendations are noted in policy and resource documents by the UN [24], World Bank Group [8], World Bank Group [30], International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies [27], Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance [25,26], CBM Global [28], and UN Women [29], which focus on disasters more broadly and were quite general in nature. The inclusion of disability in some of the documents was, on occasions, harder to identify, and was part of a broader discussion that included other minority groups.

Inclusion and active participation of marginalised groups in decision-making processes, DRR activities, and ensuring early warning systems and emergency information are in accessible formats were common themes across all documents. These marginalised groups include women and children with disability, older persons, people with diverse sexual and gender identities, migrants and refugees, and other minorities.

Awareness raising, particularly of marginalised groups at risk of violence and exploitation, and the capacity building of support/aid workers was a regular theme. The UN [24] report aimed to achieve gender equality and empower women and girls with disability; however, there were no specific information regarding the intersection of this topic and disasters presented.

Another recommendation included gender and diversity analysis and the development of a register/data collection system of people with disability, with specific focus on gender and cross-disability perspectives [8,24,26,30]. The issue of holding such data in a register of vulnerable people raises questions regarding privacy, the maintenance of the register, consent from vulnerable people who may not want to be on the register, and those who may not consider themselves as vulnerable [33]. According to Garlick [34], what such registers actually provide are small lists of older, often socially isolated adults with generic planning materials provided by support/health workers rather than the intended lists of vulnerable residents who need tailored emergency evacuation advice. Villeneuve [35] found, during Disability Inclusive Emergency Planning forums in Victoria, Australia, that conversations about such registers concentrated on misinformation about the purpose of the register, particularly as they related to people with severe and profound disability, those with cognitive impairments, and those who live alone with minimal family and social support. Rather than understanding the register as a tool to aid officials in response and evacuation planning, it was mistaken as having a broader purpose. Questions were consistently raised relating to how the register was used, by whom, the currency of the list, who is considered vulnerable, and whether the people not included on the list could get support. Such misunderstandings can increase uncertainty or raise unrealistic expectations about what supports are available and what can be expected in an emergency, leaving people feeling helpless and abandoned. The World Bank Group [8] recommended alternative ways to assess community risk, vulnerability, and capacity. For example, community mapping that includes existing information to identify people with disability and is inclusive of gender and disability perspectives to connect them to trusted networks of support.

In addition to the recommendations outlined above, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies [27] and UN Women [29] guidelines had more specific disability-inclusive recommendations that related to women and children, older people and people with diverse sexualities and genders. These recommendations considered safety from violence and exploitation. Generally, the standards are quite descriptive, and specific guidance is not provided on how to enact the recommendations. Key points include:

- Consideration of accessibility to evacuation centres that are safe for all gender identities, ages, disabilities, and backgrounds, for example, a safe location, adequate lighting on paths and latrine facilities, separate latrine, and bathing facilities with locks on doors, partitions for privacy for those with a disability who are lactating, menstruating, or require personal assistance.

- Advocate for proportional representation and equal involvement of women, people with disability, and marginalised groups in decision-making and DRR activities.

- Working with community, men, and boys to develop specific actions to reduce the risk of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and violence against children.

- Involvement of staff and volunteers in DRR activities to receive training on disability inclusion, gender, and diversity, SGBV, child protection, and trafficking in human beings with the recognition of specific health needs of women and marginalised groups.

- Care and referral pathways identified for people (including with disability) who are victims of SGBV and human trafficking.

There are several limitations with this review. While a systematic approach was taken and three of the authors reviewed and screened the literature against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, there may be some studies or reports that were missed. As scoping reviews provide an overview of the literature, an evaluation of the included studies was not carried out. All the empirical studies focused on COVID-19; therefore, generalisations to other disasters cannot be made: for example, the prominent theme of technology as an enabler for social connectedness would not be relevant for disasters such as floods or fire and may not be possible in some low-income countries. A clear gap in the literature is the lack or research of natural hazards other than COVID-19, the intersection disability and diverse genders and sexualities, and the inclusion of gender and sexual diversity in policy and practice. The grey literature was not specific to OECD countries, and most of the recommendations are general in nature and synthesised to major points as many were similar. OECD countries were an inclusion criterion, and the very different cultural contexts of these countries mean that generalisations cannot be made. However, as many high-income countries are multicultural, the findings from this study highlight the intersection of culture with disability and gender in disaster. The scarcity of resources meant we had limited literature from which to draw conclusions; however, there were common cross-cutting themes identified.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review provided an overview of empirical studies and grey literature that explored the intersection of gender, sexual identity, and disability in disaster. In particular, the key challenges faced before, during, and after disasters were explored, and the enablers and recommendations for the inclusion of this cohort in DRR were identified. The peer-reviewed literature focused on the COVID-19 pandemic with specific participant groups and research contexts. Overwhelmingly, negative outcomes were experienced by participants in the included empirical studies that impacted their physical and mental health. Recommendations focused on the use of technology to support social connectedness and build coping skills and focussed on specific genders. Other issues were also identified and were similar to those reported in the literature regarding women and gender- and sexually diverse people with disability having difficulty accessing health and support services and experiencing intersecting forms of discrimination and stigma. The grey literature had a broader focus on natural hazard disasters, with women and gender- and sexually diverse people with disability also reporting reduced access to transport, community-based supports, and services, and experiencing SGBV and exploitation. The strong themes identified in both the peer-reviewed and grey literature centre on inclusive approaches to disaster preparedness, including meaningful consultation with people with disability, active participation by diverse minority groups, awareness raising of issues faced, and capacity building of support services. Future research could explore the intersection of gender, sexual identity, disability, and culture in the context of disaster and DRR. Given this review provides a broad overview, implications for practice would be valuable. Building greater awareness of the specific needs of marginalised groups, such as women and gender-diverse and sexually diverse people, into DIDRR will reduce the disproportionate impacts of disaster on these groups.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/disabilities3040036/s1, File S1: Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.P. and M.V.; Supervision, M.V., Methodology, M.V., K.-y.J.C., F.N. and P.S.; Software, investigation, and data curation, F.N. and P.S.; Validation, K.-y.J.C., T.C. and M.V.; Formal analysis, T.C., Writing—original draft presentation, T.C., Writing—review and editing, M.V., K.-y.J.C., L.B. and D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was funded by Gender and Disaster Australia with Australian Commonwealth Government’s support (4-GJ35014).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization; The World Bank. World Report on Disability; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erman, A.; De Vries Robbe, S.A.; Fabian Thies, S.; Kabir, K.; Maruo, M. Gender Dimensions of Disaster Risk and Resilience; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, I.; Stough, L. Disability and Disaster: Explorations and Exchanges; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Masson, V. Gender and Resilience: From Theory to Practice. BRACED Knowledge Manager. 2016. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/gender-and-resilience-from-theory-to-practice/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Phibbs, S.; Good, G.; Severinsen, C.; Woodbury, E.; Williamson, K. Emergency preparedness and perceptions of vulnerability among disabled people following the Christchurch earthquakes: Applying lessons learnt to the Hyogo Framework for Action. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 2015, 19, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, M. Emergency preparedness pathways to disability inclusive disaster risk reduction. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2018, 31, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, M. Disability inclusive emergency planning: Person-centred emergency preparedness. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Glob. Public Health 2022. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Five Actions for Disability-Inclusive Disaster Risk Management; World Bank, GFDRR: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/default/files/GFDRR%20Disability%20inclusion%20in%20DRM%20Brief_FO.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Mowat, J.G. Towards a new conceptualisation of marginalisation. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 14, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartrell, A.; Calgaro, E.; Goddard, G.; Sairath, N. Disaster experiences of women with disabilities: Barriers and opportunities for disability inclusive disaster risk reduction in Cambodia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 64, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, A.; Gray, L.; Canty, J.; Blanchard, K. Beyond binary: (Re)defining “gender” for 21st century disaster risk reduction research, policy, and practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushton, A.; Phibbs, S.; Kenney, C.; Anderson, C. The gendered body politic in disaster policy and practice. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 47, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominey-Howes, D.; Gorman-Murray, A.; McKinnon, S. Emergency management response and recovery plans in relation to sexual and gender minorities in NEW South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolakowsky-Hayner, S.; Goldin, Y. Sex and Gender Issues for Individuals With Acquired Brain Injury during COVID-19: A commentary. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 2253–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISMA. PRISMA for Scoping Reviews. PRISMA Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 2023. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/ScopingReviews (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Kamel, C.; King, V.J.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Stevens, A.; Hamel, C.; Affengruber, L. Cochrane Rapid Reviews. Interim Guidance. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group. 2020. Available online: http://methods.cochrane.org/sites/methods.cochrane.org.rapidreviews/files/uploads/cochrane_rr_-_guidance-23mar2020-final.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Gul, S.; Yagmur, Y. The access of women with disabilities to Reproductive Health Services during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 15, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Hannawi, A.P.; Knight, C.; Grelotti, D.J.; Trauner, D.A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic-associated social changes on boys with moderate to severe autism. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2022, 6, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, T.L.; Bartholomay, K.L.; Lee, C.H.-Y.; Miller, J.G.; Lightbody, A.A.; Reiss, A.L. COVID-19 Pandemic: Mental health in girls with and without Fragile X Syndrome. J. Paediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molony, P.; Dobel-Ober, D.; Millichap, S. Sounds and vision: Reflections on running a community-based group for men with learning disabilities online, during the pandemic. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2022, 50, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platero, R.L.; López-Sáez, M.Á. Community responses to LGBT+ adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 confinement in Madrid. Int. Soc. Work 2023, 66, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19. United Nation. 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Policy-Brief-A-Disability-Inclusive-Response-to-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- United Nations. Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for and with Persons with Disability: UN Flagship Report on Disability and Development. United Nations: Dept of Economic and Social Affairs. 2018. Available online: https://social.un.org/publications/UN-Flagship-Report-Disability-Final.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance. Inclusion and Disaster Resilience Insights for Gender and Disability Inclusive Disaster-Resilience Building. Flood Resilience Alliance. FRMC Tip Sheet Draft. 2022. Available online: https://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/18083/1/1634-Inclusion%20and%20Resilience%20Primer_full%20PDF.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance. Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems: Experiences from Nepal and Peru. Flood Resilience Alliance. 2019. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/gender-transformative-early-warning-systems-experiences-nepal-and-peru (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Minimum standards for protection, gender and inclusion in emergencies. International Federation of Red Cross. 2018. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/Minimum-standards-for-protection-gender-and-inclusion-in-emergencies-LR.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- CBM Global. Our Lesson An Approach to Disability-Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction—Based on Consultations with People with Disa-bilities in the Asia and Pacific Regions. CBM Global Disability Inclusion. 2022. Available online: https://cbm-global.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/CBM-Inclusion-Advisory-Group-IAG-Our-Lessons-report-May-2022.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- United Nations Women. Checklist for Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Disaster/Emergency Preparedness in theCOVID-19 Context. PreventionWeb. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org.np/sites/default/files/doc_publication/2021-01/Checklist%20for%20GESI%20in%20Disaster_Emergency%20Preparedness_May2020_0.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- World Bank Group. Designing Inclusive, Accessible Early Warning Systems: Good Practices and Entry Points. World Bank, GFDRR. World Bank Document. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099050123155016375/pdf/P1765160197f400b80947e0af8c48049151.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Parkinson, D.; Duncan, A.; Leonard, W.; Archer, F. Lesbian and Bisexual Women’s Experience of Emergency Management. Gend. Issues 2021, 39, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D. Investigating the Increase in Domestic Violence Post Disaster: An Australian Case Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 2333–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorian State Government. Review of the ‘Vulnerable People in Emergencies’ Policy: Discussion Paper. 2017. Available online: http://www.daru.org.au/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/VPE-Discussion-Paper.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Garlick, D. The vulnerable people in emergencies policy: Hiding vulnerable people in plain sight. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2015, 30, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, M. Advancing the Development of Inclusive Processes in Community-Led and Municipal Emergency Management Planning in Victoria; The Centre for Disability Research and Policy, The University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).