Abstract

A major obstacle to textile recycling is the presence of dyes, which limits the reuse of fibers in high-value applications. Despite previous studies on, cotton decolorization, the systematic development of an optimal formulation that preserves fabric integrity remains lacking. This study addresses this gap by investigating a decolorization method for mixed-dyed cotton textiles that enables successful redyeing while preserving fabric quality. Reactive and vat-dyed cotton fabrics were treated with sequential reductive and oxidative processes, in a full factorial design. The impact of input parameters on tensile strength was evaluated through statistical analysis using analysis of variance at a significance level of α = 0.05. The developed recipe was subsequently validated on post-consumer cotton textiles. Stripping efficiency was assessed using K/S values, and fabric quality was evaluated through tensile strength, pilling, and fuzzing appearance. Temperature showed the strongest influence on dye removal. Fabric strength was significantly affected by temperature and oxidizing agent, and by interactions of temperature with reducing agent and oxidation time. The optimized process achieved 98–99.5% color removal and retained 95% of the fabric’s tenacity. A stripping efficiency of >90% for post-consumer cotton validates the method’s applicability in real-world circular systems.

1. Introduction

The textile industry faces a significant challenge in managing post-consumer textile waste, with millions of tons being discarded annually. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017), nearly 73% of textile waste ends up in landfills or is incinerated, with only approximately 1% being reused or recycled []. According to a 2020 study by the Federal Association for Secondary Raw Materials and Waste Management in Germany, it is forecasted that Germany alone will produce nearly 1.5 million tons of textile waste annually by 2025 []. Cotton, the second most widely used fiber after polyester, contributes significantly to textile waste, and its production has severe environmental impacts, including high water consumption, pesticide use, and greenhouse gas emissions []. For instance, producing a single pair of jeans requires approximately 3781 L of water []. Cotton cultivation also accounts for approximately 11% of global pesticide use, and producing 1 kg of cotton fabric consumes 140 MJ of energy and releases 5.3 kg of CO2 [,,]. Hence, the reintegrating of post-consumer cotton textiles is crucial for reducing landfill waste and mitigating environmental damage caused by both the virgin fiber production and disposal stages.

A key obstacle to textile recycling is the presence of dyes, which hinder the reuse of fibers in high-value applications. More than 8000 chemicals are employed in textile processing, including dyes, mordants, softeners, finishes, and coatings. These chemicals significantly limit the recyclability of fabrics []. Cotton, is dyed using a variety of dye classes, each with specific interactions with cellulose fibers []. Among them, reactive and vat dyes, known for their strong bonds with cellulose, ensure excellent color fastness but pose significant challenges for decolorization [,].

Chemical stripping techniques, such as oxidative and reductive decolorization, have been previously studied for the decolorization of textiles [,,,,,,]. In their study, Oğulata and Balci demonstrated that although sodium dithionite (Na2S2O4) is commonly used as a reducing agent in industrial applications due to its favorable cost-to-effectiveness ratio, its rapid decomposition reduces its efficiency, leading to a preference for thiourea dioxide []. To address sodium dithionite’s rapid decomposition, Wang et al. (2023) developed a two-step method to maximize its utilization []. This approach was considered in the present study by avoiding the use of toxic reducing agents, such as thiourea dioxide, while enhancing the effectiveness of sodium dithionite in achieving higher stripping results. These studies, however, have primarily focused on reactive-dyed cotton. Bigambo et al. (2021) demonstrated the high stripping efficiency of a sequential acid/dithionite/peroxide method for vat- and sulfur-dyed cotton []. Nevertheless, the reliance on high chemical concentrations, extended processing times, and dye-class-specific methods raises concerns about their applicability within circular systems. However, alternative methods such as microwave-assisted, enzyme-assisted, and plasma-assisted decolorization have also been explored to address the ecological challenges of chemical approaches, though these techniques still face limitations related to scalability and consistency [,]. Moreover, a research gap remains in establishing a statistical relationship between process parameters and their impact on fabric integrity. Hence, preserving the quality and evaluating the re-dyability of textiles after decoloring them in closed-loop textile applications is essential for replacing virgin fibers with recycled fibers in the textile supply chain. This contributes significantly to reducing energy consumption and environmental pollution []. This study presents a novel sequential alkali–reduction–oxidation approach in which polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) copolymers are incorporated during the reduction step to inhibit dye reattachment to fibers, providing an effective strategy for the removal of mixed dyes from cotton textiles.

In this study, pretreated cotton fabric (desized, scoured, and bleached) was dyed with reactive and vat dyes, representing the most commonly used dye classes for cotton. Direct dyes were excluded from this study because their non-covalent fiber binding enables easy stripping under mild conditions. Sulfur dyes were also omitted, as their dyeing and decolorization chemistry closely resembles that of vat dyes. Instead, the study focused on reactive dyes containing widely applied chromophores azo (accounting for ~95% of reactive dyes []) and anthraquinone as well as common reactive groups such as vinyl sulfone and dichlorotriazine []. Additionally, vat dye with anthraquinone chromophore was included, since ~80% of vat dyes are based on this structure []. Together, this selection provides a comprehensive representation of market-relevant dye classes. The study employed the Full Factorial Design of Experiment methodology. The effectiveness of the developed method was evaluated using a comprehensive set of tests, including colorimetric analysis (ΔE), tensile strength, pilling and fuzzing assessment, redyeing performance, and the color fastness of redyed fabrics. Furthermore, fabric tenacity was statistically evaluated using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to establish relationships with the main effects and interactions of input parameters on tenacity. By addressing the limitations of existing methods, this study contributes to the advancement of sustainable and scalable decolorization techniques for textile recycling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

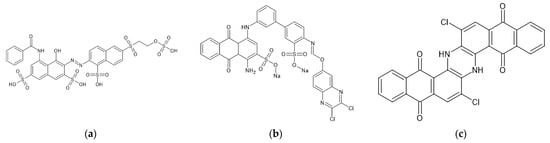

Pretreated (desized, scoured, and bleached) plain woven 100% cotton fabric (194 g/m2) was obtained from Niederrhein University of Applied Science, Mönchengladbach, Germany. Post-consumer cotton textiles from Recycling Atelier Augsburg of Institute for Textile Technolgy Augsburg gGmbH, Germany and Technical University of Applied Sciences Augsburg, Germany. Remazol Brilliant Red F3B, Levafix Brilliant Blue EB were supplied by DyStar Colors Distribution GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany and Tecothren Blue CLF was supplied by Textile Color AG, Sevelen, Switzerland. Reducing Agents (Na2S2O4), Glauber Salt (Na2SO4), Alkaline Agent (NaOH), and Acidic Agents (Citric Acid) were provided by Carl Dicke GmbH & Co. KG, Mönchengladbach, Germany. Leveling agent (Serabid MIP) was provided by CHT R. Beitlich GmbH, Tübingen, Germany, and the oxidizing agent (H2O2) was supplied by AnalytiChem GmbH, Duisburg, Germany. Table 1 presents the details of the dye stuffs used in this study. Figure 1a, Figure 1b, and Figure 1c represent the chemical structures of the Remazol Red F3B, Levafix Blue EB, and Tecothren Blue CLF, respectively.

Table 1.

Selected dye types.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of dyes: (a) Remazol Red F3B. (b) Levafix Blue EB. (c) Tecothren Blue CLF.

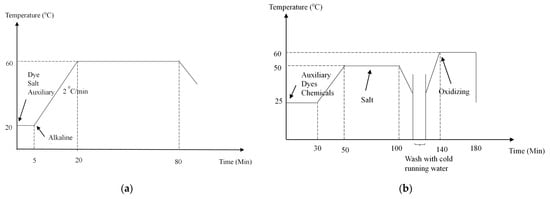

2.2. Dyeing Treatments

The cotton fabric was dyed with Remazol Red F3B, Levafix Blue EB, and Tecothren Blue CLF using the recommended commercial exhaust dyeing methods provided by the respective suppliers. Dyeing was carried out in sealed stainless steel dye pots with a 250 cm3 capacity, housed in an Ahiba Pro laboratory dyeing machine from Datacolor GmbH, Marl, Germany. The dye recipes of reactive dyeing and vat dyeing are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Dyeing profiles for both reactive and vat dyeing are shown in Figure 2a,b, respectively. After dyeing, all the fabrics were thoroughly washed according to the washing instructions provided by the respective suppliers and then air-dried.

Table 2.

Dye recipe for reactive dyeing [].

Table 3.

Dye recipe for vat dyeing [].

Figure 2.

Dyeing profiles: (a) Reactive dyeing []. (b) Vat dyeing [].

2.3. Decoloring Experiments

The stripping experiments were conducted on dyed fabrics using the Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology. Sixteen experimental recipes were designed using a two-level variation of four key parameters: reducing agent concentration, oxidizing agent concentration, oxidation time, and temperature. Due to limited fabric availability, the number of levels was restricted. Hence, the specific values for each parameter were carefully selected based on an extensive literature review and preliminary experiments to ensure the validity and reliability of the selected levels. The objective was to evaluate their impact on color removal and retention of fabric strength. The complete set of stripping recipes is presented in Table 4. Once the optimum decolorization recipe was identified through DoE, it was applied to post-consumer fabrics to evaluate its effectiveness on real-world textile waste. The decoloring treatments were carried out in sealed stainless steel dye pots of 100 cm3 capacity, housed in a Mathis laboratory dyeing machine from Werner Mathis AG, Oberhasli, Switzerland, with a liquor ratio of 1:15. The decolorization experiments were conducted in three primary stages: alkali hydrolysis, alkali reduction, and alkali oxidation. The process commenced with alkali hydrolysis, wherein the dyed fabric was subjected to treatment in an alkaline solution containing 6 g/L NaOH for 10 min to weaken the dye-fiber bonds. This was followed by the alkali reduction step, in which fabrics were treated with 4 g/L NaOH and reducing agents at concentrations specified in Table 4. Additionally, 5 g/L of Sokalan HP 56 from BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, a dye transfer inhibitor, was incorporated into the reducing solution to prevent reattachment of dissolved dye particles. After 40 min, the fabrics were thoroughly washed with warm and cold water. In the final step, alkaline oxidation, the washed fabrics were subjected to treatment in an oxidizing solution containing 4 g/L NaOH and oxidizing agents at concentrations and treatment durations outlined in Table 4. All treatments were conducted at the respective temperatures specified for each recipe in Table 4. Finally, the treated fabrics were washed in an acidic solution prepared with 20% citric acid (pH 4–5) to neutralize the alkalinity of the stripped fabrics. This was followed by thorough rinsing with hot and cold water to ensure complete removal of residual chemicals.

Table 4.

Decoloring recipes.

2.4. Analytical Instruments and Methods

2.4.1. Colorimetric Measurements

The colorimetric measurements were carried out using a Spectra Vision Data color spectrophotometer from Datacolor GmbH, Marl, with illuminant D65 and the 100 Standard Observer. The samples were folded four times to ensure the opacity. DE (total color difference against the respective dyed fabric) after stripping treatment of the experimented fabrics and post-consumer fabrics, and the R (Reflectance factor) of dyed fabrics, stripped fabrics with the selected final recipe, and post-consumer fabrics (before and after stripping) were measured. The K/S value (color strength) of the dyed and stripped fabrics was determined using the Kubelka-Munk equation (Equation (1)), measured at the wavelength corresponding to the maximum absorption (i.e., the point of lowest reflectance (R)) for each individual dye []. The stripping efficiency of the decolorized fabric was calculated using Equation (2). This evaluation was performed on fabrics treated with the final optimized decolorization process, as well as on post-consumer textile samples.

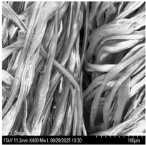

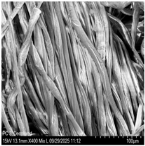

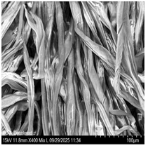

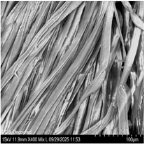

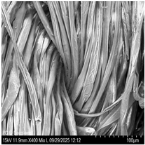

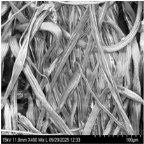

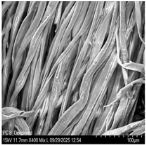

2.4.2. SEM Analysis

The topography of the post-consumer samples before and after decoloring was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM: TM4000Plus Tabletop microscope, Hitachi, Tokio, Japan) to assess the possible fiber damages and the presence of residual chemicals.

2.4.3. Tensile Strength (DIN EN ISO 13934-1) []

Tensile Strength was tested using Zwick Universal Testing machine from ZwickRoell GmbH & Co.KG, Ulm, Germany, with a 2 N pre-load, 100 mm/min speed, and 200 mm distance between the two clamps. 50 mm × 50 mm clamping jaws were used. The strength retention of decolored fabrics against the dyed fabrics was calculated using Equation (3).

2.4.4. Pilling and Fuzzing Test (DIN EN ISO 12945) []

Pilling and Fuzzing tests were conducted using the Martindale Pilling and Abrasion Tester from Mesdan S.p.A, Garda, Italy. The appearance of the samples was analyzed and graded after each revolution round (125, 500, 1000, 2000, 5000, 7000) by comparing them with the standard reference images, graded from 1 (worst) to 5 (best).

2.4.5. Color Fastness to Dry/Wet Rubbing Test (DIN EN ISO 105-X12) []

The decolored fabrics with recipe 16 were re-dyed with Levafix Blue EB and tested for color fastness using a standard crocking meter from James H. Heal, Halifax, UK, under both dry and wet conditions. The test was conducted by applying a (9 +/− 0.2) N downward force by the friction pin which was covered with a white color fabric (friction fabric) and performing a rectilinear 20 reciprocating movement (10 forward and 10 backward) with the frequency of 1 cycle per second over a distance of (104 +/− 3) mm []. For evaluation, each tested friction fabric was backed with three layers of white friction fabric, and the staining was assessed using grey scale under D65 light source.

2.4.6. Fabric Composition of Post-Consumer Fabrics

Post-consumer materials collected from Recycling Atelier Augsburg of Institute for Textile Technology Augsburg gGmbH and Technical University of Applied Science Augsburg were analyzed using the trinamiX Mobile NIR Spectroscopy device from trinamiX GmbH, Ludwigshafen, Germany, at the Center of Textile Logistics (CTL) at Hochschule Niederrhein, to confirm their composition as 100% cotton before being subject to stripping treatment. This portable spectrometer operates within a spectral range of 1450 to 2450 nm, with a spectral resolution of 1% of the wavelength, and utilizes six tungsten-halogen lamps as a light source [].

2.4.7. Statistical Analysis

ANOVA was performed to mathematically evaluate the significance of input parameters, including reducing agent concentration, oxidizing agent concentration, oxidation time, and temperature, on the tenacity of treated fabrics. The analysis was conducted using JASP (version 0.95.4), statistical analysis software.

3. Results

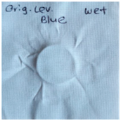

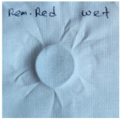

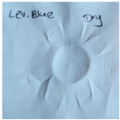

3.1. Visual Representation of Decolored Fabrics

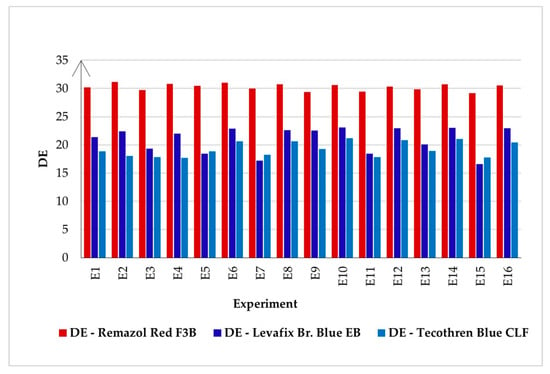

Table 5 presents data color spectroscopy images, where E1–E16 correspond to the 16 decolorization recipes detailed in Table 4. DE values of the stripped fabrics were measured against the dyed fabric to determine the amount of color change.

Table 5.

Visual representation of the dyed and decolored fabrics.

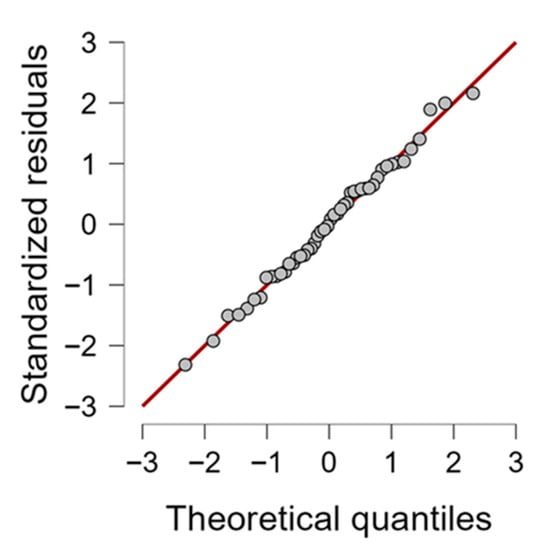

3.2. Statistical Analysis of Tenacity Impact

To gain a better understanding of the impact of stripping parameters on fabric tenacity, an ANOVA statistical analysis was conducted. Given the limited availability of fabric, one sample from each of the three dyed fabrics (Remazol Red F3B, Levafix Blue EB, and Tecothren Blue CLF) treated with the same recipe was used as three replicates. While this design may introduce some variability, it offers a practical framework for comparison. Future studies could expand the number of fabrics and replicates to further reinforce the statistical strength of the results. The statistical significance of the main effects and interaction effects was determined by the p-value less than 0.05. Table 6 presents the ANOVA results, conducted at a 95% confidence interval. In this study, the highlighted cells represent cases where p < 0.05, demonstrating significant effects on the measured outcomes (tenacity). The assumptions of ANOVA were verified before interpreting results. Normality of residuals was confirmed using Q–Q plots (Figure 3), where the majority of data points aligned closely with the diagonal reference line, indicating conformity to a normal distribution and supporting the validity of the ANOVA results.

Table 6.

ANOVA table for tenacity.

Figure 3.

Q–Q plot of Anova residuals.

Red. Conc.—Reducing agents Concentration.

Oxi. Conc.—Oxidizing agents Concentration.

Oxi. Time—Oxidizing Time.

DF—Degree of Freedom.

F—Ratio of variance of between the group means to variance within the group means.

P—Probability that the observed difference occurred by random chance.

3.3. Further Quality Validation for the Selected Recipe

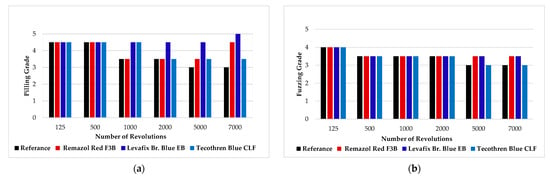

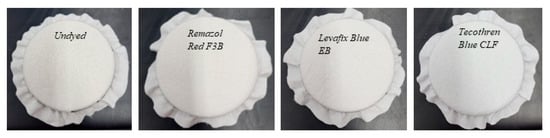

Recipe 16 (Table 4) was identified as the optimal formulation, demonstrating the best combined performance in terms of color removal and fabric strength retention. This recipe was further validated by calculating the stripping efficiency, assessing tenacity, conducting pilling and fuzzing tests, redyeing, and a rubbing test. Application of the optimized decolorization protocol (Recipe 16) to fabrics dyed with Remazol Red F3B, Levafix Blue EB, and Tecothren Blue CLF yielded stripping efficiencies of 99.8%, 99%, and 96%, respectively, based on their color strength (K/S) values (Table 7). Further, tenacity analysis of the treated fabric using the optimized recipe compared to the untreated fabric revealed a tenacity loss of only 5%. The pilling and fuzzing appearance results are presented in Figure 4a,b, respectively. Pilling and fuzzing appearance of the stripped samples after 7000 turns are presented in Figure 5. The re-dyeability performance of the decolorized fabrics was evaluated by re-dyeing them with Levafix Blue EB and measuring the color difference relative to the originally dyed fabric. Additionally, the wet and dry rubbing fastness results are presented in Table 8.

Table 7.

Stripping efficiency of the decolored fabrics (Selected Recipe/Recipe 16).

Figure 4.

Martindale pilling and fuzzing test results (a) Change in pilling appearance with number of revolutions. (b) Change in fuzzing appearance with the number of revolutions.

Figure 5.

Pilling and fuzzing appearance of the stripped samples after 7000 turns.

Table 8.

DE and colorfastness results of redyed fabrics.

3.4. Assessment of the Selected Recipe on the Post-Consumer Fabrics

Fourteen post-consumer samples were collected from Recycling Atelier Augsburg of Institute for Textile Technology Augsburg gGmbH and Technical University of Applied Sciences Augsburg and were first analyzed using the trinamiX mobile NIR spectroscopy to confirm their composition. Among them 100% cotton fabrics were treated with the selected recipe and stripping efficiencies of them are shown in the table below.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Stripping Treatment on Color Removal

According to Figure 6, the even-numbered experiments (high-temperature experiments) consistently show higher DE values compared to the odd-numbered ones, a pattern further supported by the data color spectroscopy images (Table 5). These findings underscore the pivotal role of temperature in color removal, regardless of the dye type. The increase in the kinetic energy of the dye molecules at higher temperatures enhances their solubility and weakens their affinity to the fiber, thereby promoting dye desorption. Additionally, elevated temperatures accelerate the chemical reactions of reducing and oxidizing agents, significantly improving their reaction efficiency and overall decolorization effectiveness [,]. Among the tested dyes, Remazol Red demonstrates the highest color removal efficiency across all 16 recipes, outperforming Levafix Blue and Tecothren Blue. The high susceptibility of the azo group (−N=N−) to nucleophilic attack renders Remazol Red particularly vulnerable to reduction, resulting in the cleavage of the azo bond and subsequent loss of color [,].

Figure 6.

Color change (DE) of the decolored fabrics (measured against the respective dyed fabric).

4.2. Statistical Analysis

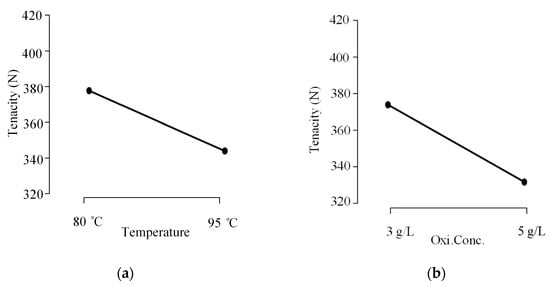

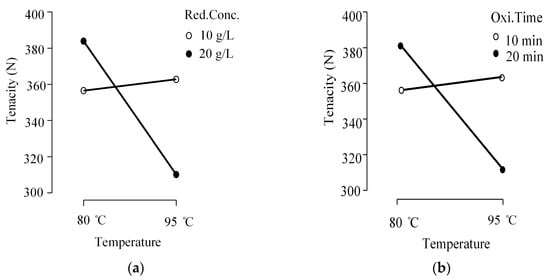

The following descriptive plots can better represent the main and interaction effects of Table 6. According to the main effect plots (Figure 7a,b), two parameters are significant.

Figure 7.

Main effects plots (a) Effect of temperature on average tenacity. (b) Effect of oxidizing agents’ concentration on average tenacity.

- -

- Temperature

- -

- Oxidizing Agents’ Concentration

The higher slope of the average tenacity in Figure 7a,b indicates that temperature and the concentration of oxidizing agents have a significant impact on tenacity. (The main effect plots for the other two parameters show a lower slope; hence, the effect is minimal and not included here). This can be attributed to the reduction in fiber crystallinity resulting from the disruption of hydrogen bonds within the cellulose polymer chains by thermal energy at higher temperatures [,]. Additionally, high temperatures accelerate hydrolytic reactions, especially in alkaline media, causing the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds in cellulose and reducing the molecular weight, which makes fibers more brittle and weaker [,]. Oxidizing agents react with hydroxyl groups in the cellulose polymer chains, converting them into carbonyl (C=O) and carboxyl (−COOH) groups []. This modification disrupts hydrogen bonding, weakening fiber structure and reducing tenacity. In addition, oxidizing agents contribute to reducing the degree of polymerization by breaking down the cellulose polymer chains, which results in weaker fibers [].

According to the interaction plots, two interactions are significant.

- -

- Reducing Agents’ Concentration × Temperature

- -

- Oxidizing Time × Temperature

Crossed lines of Figure 8a,b indicate the significance of the interactions of the given parameters. Based on this finding, it can be predicted that the reducing agent begins to affect tenacity at high temperatures. This could be attributed to the increased reaction kinetics of reducing agents at higher temperatures [,]. However, this effect is not as pronounced with oxidizing agents. A more comprehensive study is recommended, with additional rounds of repeated experiments, to further validate this finding. However, the interaction between oxidation time and temperature has been shown to have a significant impact on fabric tenacity. Oxidizing time could also reflect the overall oxidative effect, which, when combined with elevated temperature, further intensifies fiber tenacity loss. This is consistent with the individual contributions of both factors, as discussed in the main effects plots.

Figure 8.

Interaction effects plots (a) Interaction of temperature and reducing agents’ concentration on average tenacity. (b) Interaction of temperature and oxidizing time on average tenacity.

4.3. Final Recipe Selection

Based on colorimetric and tenacity results, Recipe 16 was identified as the best-performing recipe. Its combination of higher temperature (95 °C) for effective color removal and lower levels of the other three parameters (reducing agents’ concentration, oxidizing agents’ concentration, and oxidizing time) to minimize tenacity loss ensures an optimal balance between dye stripping efficiency and fabric quality preservation. Due to its reduced chemical consumption, this formulation also ensures safer chemical usage. However, scaling up the process would generate a certain effluent load, underscoring the need for future studies focusing on optimizing the process to minimize chemical inputs and exploring more sustainable alternatives to reduce the overall environmental burden.

4.4. Further Quality Validation

The pill appearance results show a slight initial negative effect, with increased pill formation, although values remain comparable to the reference sample. However, in Remazol Red and Levafix Blue samples, the appearance improved with the increasing number of turns due to the easier removal of pill balls. In contrast, Tecothren Blue did not exhibit the same improvement, despite undergoing identical treatment conditions (Figure 4a). This discrepancy may be attributed to the remaining color in the decolored fabric, as Tecothren Blue showed lower color removal efficiency compared to the other two dyes, potentially influencing the visual assessment.

The fuzzing appearance remained nearly unchanged after the initial round, with only a slight variation observed in the Tecothren Blue sample (Figure 4b). These results suggest that the selected decoloring recipe does not negatively impact the fabric’s pilling and fuzzing performance.

Additionally, the DE values close to 1 for all three redyed fabrics (Table 8) indicate that the stripped fabric can successfully achieve the desired color in redyeing, remaining visually indistinguishable from the original dyed fabric.

More importantly, the high dry and wet rubbing fastness results suggest effective cleavage of dye-fiber bonds during decolorization, facilitating stronger bonding between the fiber and dye molecules in the re-dyeing process.

4.5. Post-Consumer Validation

Five samples out of fourteen were identified as not 95–100% cotton. This highlights the importance of utilizing reliable technology for identifying material compositions in sorting facilities before proceeding to subsequent processing stages. Those samples were classified as being greater than 95% cotton samples through manual sorting by the sorting facility where the samples were collected. This is particularly crucial in decolorization, as different fiber types undergo distinct dyeing processes, directly influencing the appropriate decolorization method.

Eight out of nine treated post-consumer fabrics showed stripping efficiencies above 90% (Table 9), indicate that the selected decolorization recipe effectively removed the dye, achieving satisfactory color removal from the post-consumer fabrics. However, within the small sample set of nine, the observation of a single sample showing only 68% color removal highlights the inherent variability of dyes and finishing agents in real post-consumer textiles, underscoring the challenge of developing a universal decolorization recipe. Nonetheless, SEM analysis revealed minimal to no surface damage to fibers following the decolorization treatment and no detectable chemical residues on the fiber surfaces.

Table 9.

Visual representation and SEM analysis of the before-and-after decoloring of post-consumer cotton fabrics, DE, and stripping efficiency.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an optimized decolorization recipe was developed for mixed-dyed cotton fabrics, placing equal emphasis on fabric tenacity retention alongside color removal. This work offers a practical solution to a key challenge faced by textile recyclers, addressing the limitations of existing methods in their applicability to real-world post-consumer textiles and providing a comprehensive quality assessment to enable high-value product applications.

The following conclusions can be drawn from this experimental study.

- ▪

- Use of dye transfer inhibitor agents is essential in decoloring vat-dyed fabrics.

- ▪

- Temperature has a significant impact on decoloring.

- ▪

- Temperature and Oxidizing agents alone have a significant impact on the fabric’s tenacity.

- ▪

- The interaction of reducing agents’ concentration × temperature and oxidizing time × temperature has a significant impact on the fabric’s tenacity.

- ▪

- The developed decoloring recipe can strip the 96–99.8% color from mixed dyed cotton fabrics satisfactorily while preserving about 80–95% of the fabric’s tenacity.

- ▪

- The developed recipe has successfully cleaved the dye fiber bonds, enabling successful redyeing.

- ▪

- Decolored fabrics exhibit improved pilling performance, characterized by the easier removal of pill balls.

- ▪

- The developed recipe can successfully remove more than 90% color from the post-consumer fabrics.

The developed decolorization recipe compatible with existing dyeing machines eliminates the need for specialized equipment, enabling seamless industrial integration and scalability. This versatile and efficient approach supports sustainable textile recycling, contributing to environmentally friendly practices in the industry.

Future research could explore alternative decolorization agents that maximize efficiency while further minimizing fabric degradation and environmental impact. Additionally, the identification of dye types present in post-consumer textiles remains an open question, which, if addressed, could significantly enhance the development of a comprehensive decolorization strategy. Moreover, scaling up the process to a mini-bulk level would facilitate the production of fiber, yarn, and fabric from decolorized textiles, enabling a comprehensive assessment of its feasibility within a closed-loop recycling system. A comprehensive Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is also necessary to evaluate its sustainability in comparison to virgin cotton production. These investigations would contribute to a more effective and sustainable framework for textile recycling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., G.S., E.A.M.A. and M.C.; methodology, material preparation, testing, data collection, data analysis, E.A.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.M.A.; review, M.R., G.S. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Simone Wagner, Gudrun Lieutenant-Bister, and Petra Glinde from Hochschule Niederrhein for their valuable support in the finishing laboratory, color measurements, and analytical testing. Please note that all product and company names referenced in this article may be trademarks of their respective owners, regardless of explicit labeling.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Georg Stegschuster and Mesut Cetin were employed by the company Institute for Textile Technology Augsburg gGmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Institute for Textile Technology Augsburg gGmbH has roles in the design of the study, providing post-consumer textiles for experiments, reviewing the manuscript, and the decision to publish the results.

References

- A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Forbrig, S.; Fischer, T.; Heinz, B. Demand, consumption, reuse and recycling of clothing and textiles in Germany. Textile Study 2020, 9, 1–60. Available online: https://www.bvse.de/dateien2020/2-PDF/02-Presse/06-Textil/2020/bvse-Textilstudie_2020_eng.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Ütebay, B.; Çelik, P.; Çay, A. Effects of cotton textile waste properties on recycled fibre quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmink, R.; Baghaei, B.; Skrifvars, M. Development of biocomposites from denim waste and thermoset bio-resins for structural applications. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 106, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-317-93521-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Pichandi, S.; Parveen, S.; Fangueiro, R. Natural Plant Fibers: Production, Processing, Properties and Their Sustainability Parameters. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing, Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Springer Science+ Business Media: Singapore, 2014; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, C.A.; Handoko, W.; Pahlevani, F.; Sahajwalla, V. Cascading use of textile waste for the advancement of fibre reinforced composites for building applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Environmental impact of textile reuse and recycling—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkannan, S.; Miguel, M.; Gardetti, A. Sustainable Textiles: Production, Processing, Manufacturing & Chemistry Sustainability in the Textile and Apparel Industries. Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/16490 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Kataria, J.; Rawat, H.; Tomar, H.; Gaurav, N.; Kumar, A. Azo Dyes Degradation Approaches and Challenges: An Overview. Sci. Temper 2022, 13, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.G.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, M.R. Effects of reductive stripping of reactive dyes on the quality of cotton fabric. Fash. Text. 2015, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, C. Decolorization properties and mechanism of reactive-dyed cotton fabrics with different structures utilized to prepare cotton pulp. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4735–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Ali, S.; Noureen, S.; Zahira, T.; Akhtar, A.; Khan, M.A.A. Study of microwave-assisted sequential color stripping of cellulosic fabric dyed with reactive blue black 5 and reactive turquoise CLB. Cellulose 2023, 30, 5339–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Alam, M.; Noureen, S.; Ali, S.; Tahir, A.T.; Shoukat, A. Transforming waste cellulosic fabric dyed with Reactive Yellow C4GL into value textile by a microwave assisted energy efficient system of color stripping. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oğulata, R.T.; Balci, O. Investigation of the stripping process of the reactive dyes using organic sulphur reducing agents in alkali condition. Fibers Polym. 2007, 8, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigambo, P.; Carr, C.M.; Sumner, M.; Rigout, M. Investigation into the removal of pigment, sulphur and vat colourants from cotton textiles and implications for waste cellulosic recycling. Color. Technol. 2021, 137, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, C. Efficient decolorization of reactive dyed cotton fabric with a two-step NaOH/Na2S2O4 process. Cellulose 2024, 31, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Z.; Shafique, J.; Summuna, B.; Lone, B.; Rehman, M.u.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Hashim, M.J.; Vladulescu, C.; Shafique, T. Development of efficient strain of Ganoderma lucidum for biological stripping of cotton fabric dyed Reactive Blue 21. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 7550–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichim, M.; Sava, C. Study on recycling cotton fabric scraps into yarns. Bul. AGIR 2022, 3, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold, T.; Pham, T. Textile Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Bechtold, T., Pham, T., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, N.N. Textile Dyes; WPI Publishing: Jericho, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-429-11329-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DyStar Textilfarben GmbH Co.; Levafix® Remazol®. High-Performance Reactive Dyes for all Requirements and Processes; Springer: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Textilcolor, A.G. Dye Stuffs Tecothren Vat Dyes; Textilcolor AG: Seveln, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.N.; Li, X.; Zhu, M.K.; Hu, J.H.; Yuan, Y.J.; Li, C.C.; Long, J.J. Color stripping of reactive-dyed cotton fabric in a UV/sodium hydrosulfite system with a dipping manner at low temperature. Cellulose 2019, 26, 4125–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 13934-1; Textiles—Tensile properties of fabrics—Part 1: Determination of maximum force and elongation at maximum force using the strip method. Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN) / Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2013.

- DIN EN ISO 12945-1; Textiles—Determination of fabric propensity to surface pilling, fuzzing or matting—Part 1: Pilling box method. Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN) / Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- DIN EN ISO 105-X12; Textiles—Tests for Colour Fastness—Part X12: Colour Fastness to Rubbing. Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN)/Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- Bia Analytical Ltd. Operational Manual: Portable Authenticity Testing. Available online: https://www.bia-analytical.com (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Asad, S.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Pourbabaee, A.A.; Sarbolouki, M.N.; Dastgheib, S.M.M. Decolorization of textile azo dyes by newly isolated halophilic and halotolerant bacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2082–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, H.; Hasani, H. Effect of the different processing stages on mechanical and Surface properties of cotton-knitted fabrics. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2010, 35, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Litim, N. Impact of Modified Glyoxalic and Co-polymer Acrylic Crosslinkers Effect on the Crystallinity and Mechanical Properties of Finished Cotton. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2019, 9, 1000391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrales, L.; Abidi, N. On the thermal degradation of cellulose in cotton fibers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2010, 102, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.-J.; Eom, S.H.; Wada, M. Thermal decomposition of native cellulose: Influence on crystallite size. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, J.; Pouyet, F.; Chirat, C.; Lachenal, D. Formation of Carbonyl and Carboxyl Groups on Cellulosic Pulps: Effect on Alkali Resistance. BioResources 2014, 9, 7299–7310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshikj, E.; Tarbuk, A.; Grgić, K.; Mangovska, B.; Jordanov, I. Influence of different oxidizing systems on cellulose oxidation level: Introduced groups versus degradation model. Cellulose 2019, 26, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GENERAL CHEMISTRY LibreTexts (Textmap of Petrucci’s Book). Available online: https://LibreTexts.org (accessed on 25 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).