Abstract

Metallic implants used in orthopedics, such as titanium alloys, possess excellent mechanical strength but suffer from corrosion and poor bio-integration, often necessitating revision surgeries. Bioactive coatings, particularly hydroxyapatite, can enhance implant osteoconductivity, but high-purity synthetic hydroxyapatite is costly. This study investigates the development and characterization of a low-cost, biocompatible coating using hydroxyapatite derived from an unconventional natural source dromedary bone applied onto a titanium substrate via plasma spraying. Hydroxyapatite powder was synthesized from dromedary femurs through a thermal treatment process at 1000 °C. The resulting powder was then deposited onto a sandblasted titanium dioxide substrate using an atmospheric plasma spray technique. The physicochemical, structural, and morphological properties of both the source powder and the final coating were comprehensively analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy, Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy, X-ray Diffraction, and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Characterization of the powder confirmed the successful synthesis of pure, crystalline hydroxyapatite, with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy analysis verifying the complete removal of organic matter. The plasma-sprayed coating exhibited good adhesion and a homogenous, lamellar microstructure typical of thermal spray processes, with an average thickness of approximately 95 μm. X-ray Diffraction analysis of the coating revealed that while hydroxyapatite remained the primary phase, partial decomposition occurred during spraying, leading to the formation of secondary phases, including tricalcium phosphate and calcium oxide. Scanning Electron Microscopy imaging showed a porous surface composed of fully and partially melted particles, a feature potentially beneficial for bone integration. The findings demonstrate that dromedary bone is a viable and low-cost precursor for producing bioactive hydroxyapatite coatings for orthopedic implants. The plasma spray method successfully creates a well-adhered, porous coating, though process-induced phase changes must be considered for biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

Artificial materials have been developed by researchers, such as bone substitute grafts, to reduce the insufficiency of xenografts and allografts and to lessen the danger of disease transmission (artificial hip joints, bone plates and dental implants) [1]. Traditionally, the most commonly used orthopedic appliances are made of stainless steel (SS), cobalt-based alloys, and titanium (Ti). These alloys have excellent mechanical properties compared to bioactive ceramics, which are inherently weak and brittle [2]. However, these metallic implants have problems of corrosion and wear in the biological environment [3], involving the release of toxic and allergenic corrosion products, which can cause inflammatory reactions leading to need a second surgical intervention for implant removal. This increases the risk of infection and also the financial burden on the patient and/or the healthcare system [4]. The surface of the implant is the first point of contact with the host. Therefore, surface modifications are required to improve the qualities of certain medical devices [5,6]. Various surface modification approaches, such as chemical treatment, physical treatment, and biological procedures, have been utilized on metallic implants to overcome these surface-related difficulties [3]. Many techniques have been developed to improve the surface compatibility of implants with bone [7]. Thus, the hypothesis of biological fixation of weight-bearing implants utilizing bioactive calcium phosphate coatings as an alternative to cemented fixation was introduced in the late 1960s as a way to induce quick implant stabilization and avoid the use of bone cements [8]. However, hydroxyapatite-based bulk ceramics cannot be employed in orthopedic appliances that must bear high stresses during their service life due to their brittle nature [9]. Nevertheless, because of it is chemically similar to inorganic bone matrix, hydroxyapatite can significantly improve the osteoconductivity of metallic implants when used as a covering [10,11]. The clinical relevance of hydroxyapatite coatings is evident in their ability to promote osseointegration, a crucial process for the long-term success of orthopedic and dental implants [9]. By facilitating direct bone-to-implant contact, these coatings reduce the likelihood of fibrous tissue formation, implant loosening, and subsequent revision surgeries, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes and quality of life [9]. Therefore, low-cost alternative research is an urgent need. Due to the high costs inherent in the use of high-purity reagents, laboratory-produced calcium phosphate, as well as commercially available synthetic hydroxyapatite, pose a serious problem [9]. To overcome the cost problems, the use of waste materials is interest to many researchers because of their abundance, low price, and good mechanical and chemical resistance. The use of waste materials as a source of biomaterials is in line with environmental regulations that are becoming increasingly strict in limiting disposal practices or discharge into water [12]. To this end, other methods and procedures are used to produce hydroxyapatite from inexpensive and recyclable materials [13] such as bovine bone, pig bone, ostrich bone, eggshell, Brazilian fish and Japanese fish [14,15]. It is in this perspective that our work is initiated in order to elaborate a coating of hydroxyapatite of natural origin (from dromedary bone rejects) by plasma projection. To our knowledge, little attention has been paid to the valorization of dromedary bone in the medical or environmental field and its use as a coating for a metallic implant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hydroxyapatite Powder Preparation

The source used in this study is the femurs of dromedary bone. The dromedary farm is located in the south-eastern region of Algeria, in the wilaya of Oued-Souf. The extraction of the bone mineral material is performed by heat treatment at 1000 °C for 12 h in an ambient atmosphere, which the preliminary stage of preparation is the treatment of bones by a gas torch to remove all the fat that is present in their surface and to reduce the smell of gas evolution during their calcination. After that, the bones are crushed into small pieces to ensure effective calcination [16,17]. The prepared powder is thermally reprocessed at 1000 °C for 24 h to increase its flexibility and to have the desired particle size for the projection process.

2.2. Coating Elaboration

The coating of natural hydroxyapatite prepared on a titanium dioxide substrate (commercial titanium alloy, Ti6Al4V) by plasma projection is carried out, using a Metco commercial machine, F4-MB, whose conditions for spraying apatite powders of particle size 50–150 μm are presented in Table 1. Moreover, the substrate had dimensions of 5 cm length, 2.3 cm width, and 1 cm thickness, before the elaboration of coating the surface of the substrate is sandblasted (Ferro ECOB Last, BLAST 0.5) by alumina (Al2O3) at blasting angle of 90° with a pressure of 100 psi for 2 to 3 min to roughen the surface of titanium substrate rough.

Table 1.

Optimal parameters retained for the projection of apatite powders by the plasma torch.

2.3. Characterization

The observation of the shape and size of the powder and the surface coating and cross-section was carried out by a scanning electron microscope coupled with an X-EDS microanalysis system (Leo 1530, Carl Zeiss, Hamburg, Germany). The identification of the structures and phase compositions of the powder used for the coating and the coating itself was performed by X-ray diffraction with copper Kα radiation (CuKα, λ = 1.54056 Å) on a diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance, Karlsruhe, Germany), whose spectrum is taken at 2θ: 10–80° with a step size of 0.02. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (IRAffinity-1S, SHIMADZU CORP 01154, Amman, Jordan) was used for the analyses of the powders in the wavelength range of (400–4000 cm−1) to distinguish the presence or absence of the organic material in the bone powder used for coating. FTIR analysis of the coating was performed on the scraped-off powder from the coating surface.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Hydroxyaapatite Powder

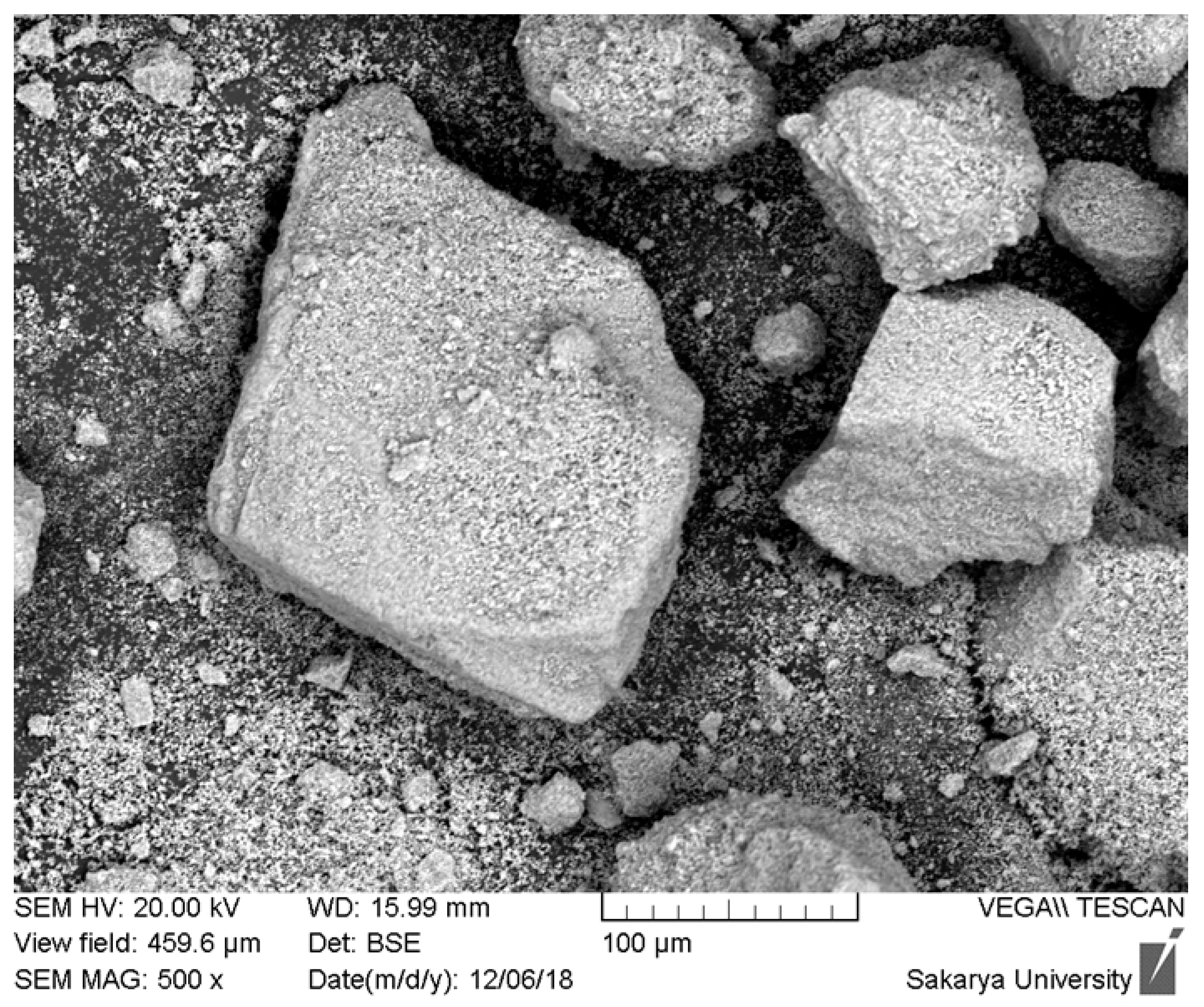

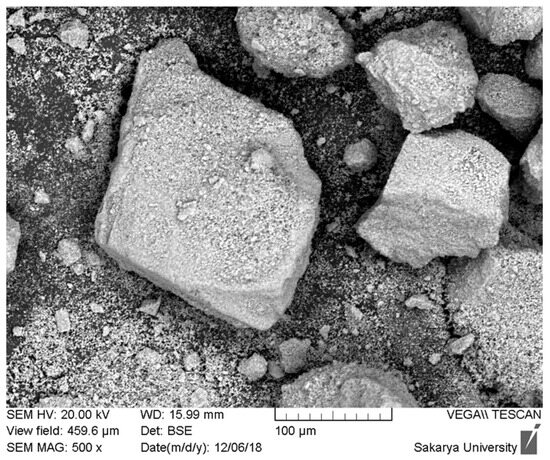

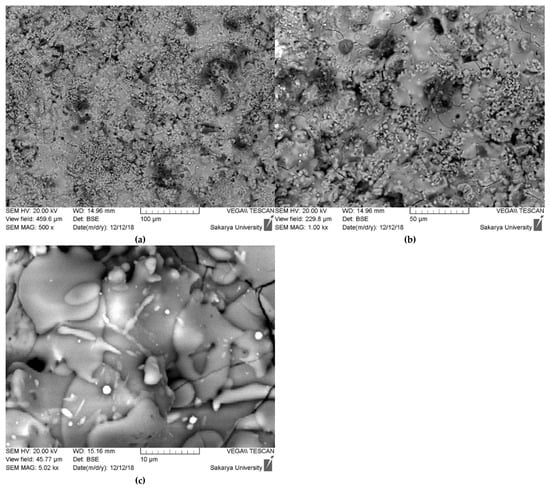

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the hydroxyapatite (HAp) powder extracted from dromedary bone and heat-treated at 1000 °C is presented in Figure 1. This initial morphological characterization is fundamental to understanding the material’s performance during its subsequent use. Observation of the micrograph reveals highly angular and irregular-shaped particles with sharp edges. Furthermore, the particle size distribution is clearly wide and heterogeneous, showing the coexistence of large fragments, some of which exceed 200 µm, and a significant amount of much finer particles adhering to their surface. The granular texture visible on the larger particles suggests that they are dense agglomerates of smaller crystallites, formed during calcination, rather than monolithic particles.

Figure 1.

SEM images of hydroxyapatite obtained from dromedary bone at 1000 °C for 12 h.

This morphology directly explains why the attempts to create a plasma-sprayed coating from this powder did not yield conclusive results. The plasma spray process requires a powder with very specific physical characteristics. Firstly, the angular and variably sized particles have very poor flowability, which causes an irregular and non-reproducible powder feed into the plasma torch. Secondly, the wide particle size distribution leads to heterogeneous thermal behavior in the plasma jet: the finest particles are at risk of overheating and vaporizing, while the larger ones do not have enough time to melt completely to their core. This phenomenon inevitably leads to the formation of a low-quality coating, characterized by high porosity, poor internal cohesion, and weak adhesion to the substrate.

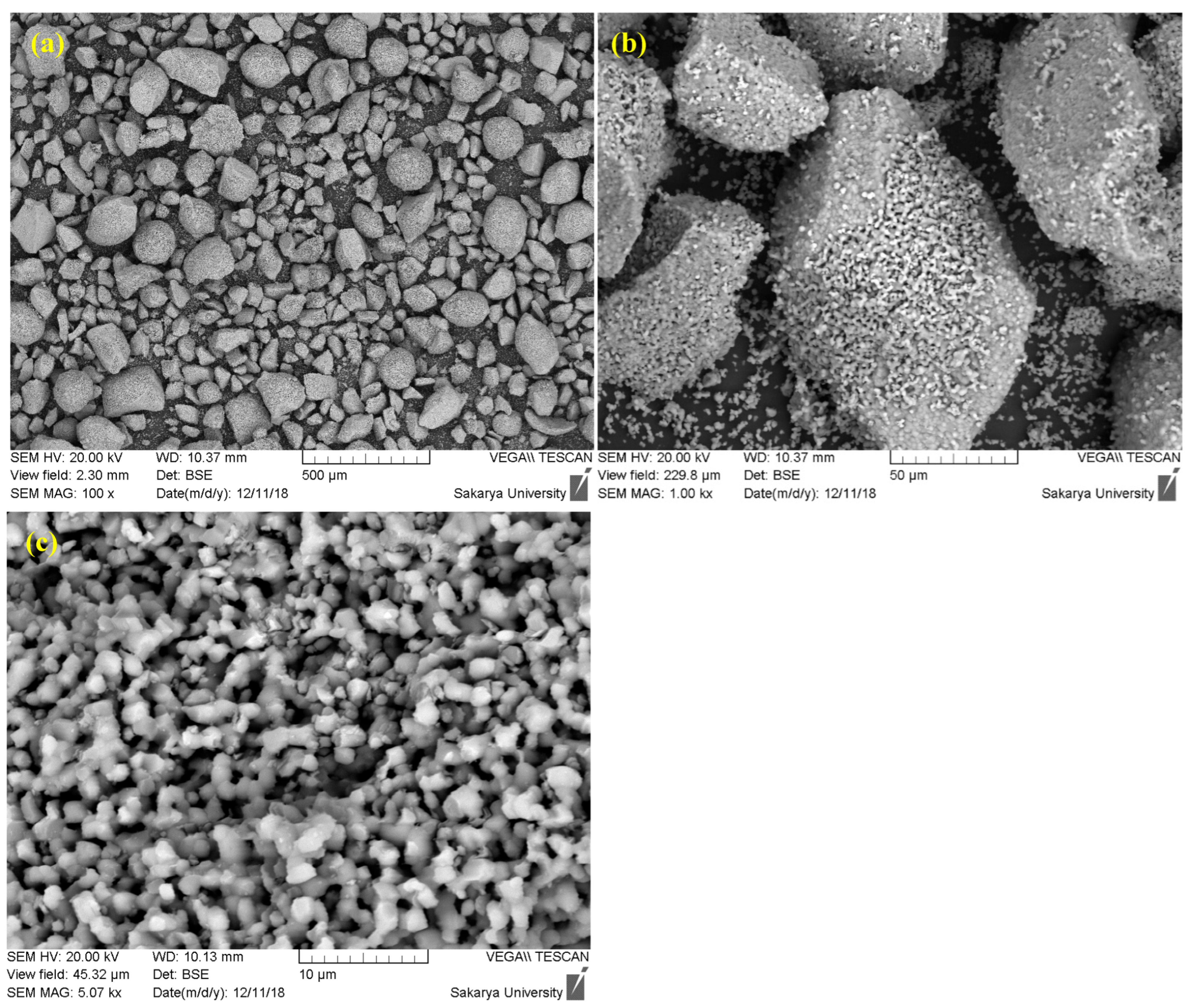

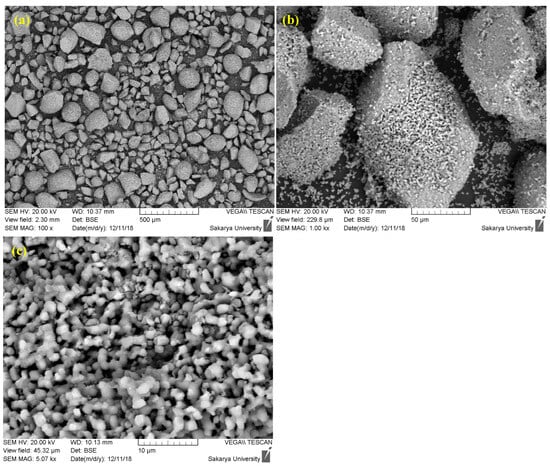

Faced with these limitations, the decision to modify the preparation protocol by introducing a prolonged sintering step is a strategic and justified approach. Sintering, which consists of maintaining the powder at a high temperature (1000 °C) for an extended period (up to 24 h), specifically aims to correct the identified morphological defects (Figure 2). This heat treatment promotes two key mechanisms: densification and spheroidization. Densification occurs through atomic diffusion, which eliminates porosity within the agglomerates, leading to denser and more thermally stable particles. Simultaneously, the minimization of surface energy during sintering tends to transform the angular particles into a more spherical morphology, while promoting controlled grain growth.

Figure 2.

SEM images of hydroxyapatite sintered at 1000 °C for 24 h ((a) 500 µm, (b) 50 µm, (c) 10 µm).

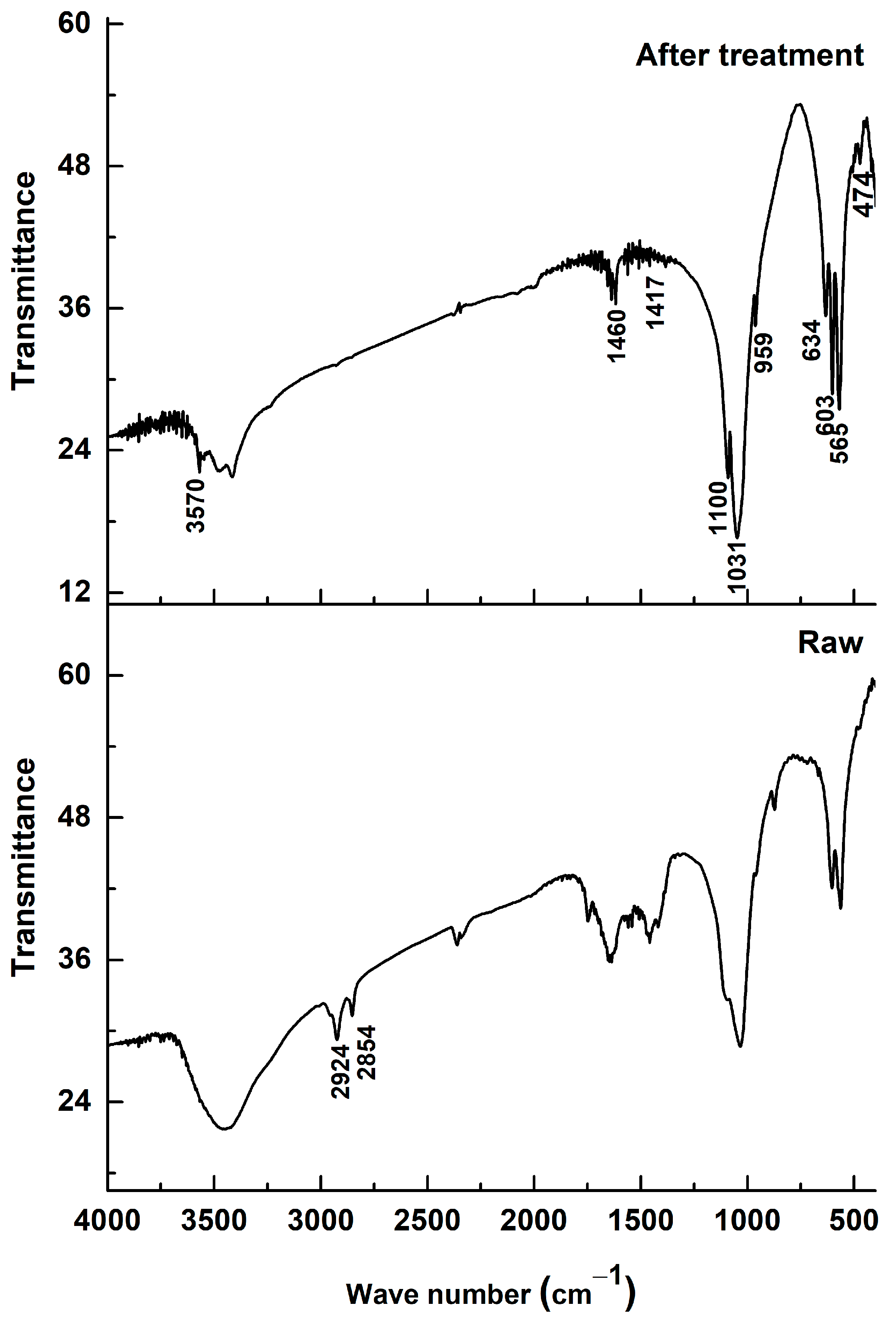

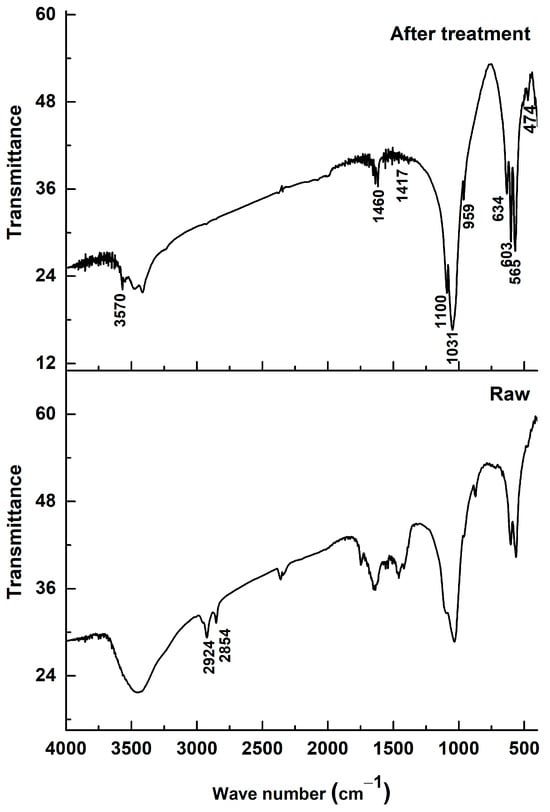

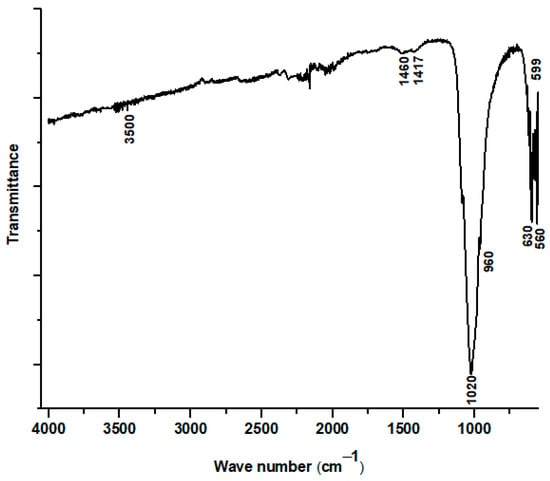

Figure 3 shows the Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of dromedary bone powder before (spectrum “Raw”) and after heat treatment by calcination (spectrum “After treatment”). The purpose of this analysis is to monitor the chemical transformations the material undergoes and to validate the effectiveness of the treatment in obtaining a pure hydroxyapatite powder.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrum of bone dromedary thermally treated.

The spectrum of the raw sample (“Raw”) is characteristic of a natural composite material, bone, which consists of an organic matrix (mainly collagen) and a mineral phase (biological apatite). The presence of the organic matrix is clearly identified by the absorption bands associated with the amide (N-H) and aliphatic (C-H) functional groups of collagen, located at the wavenumbers 2860, 2913, and 2929 cm−1 [18,19]. The broad bands typical of proteins are also observed in the 1500–1700 cm−1 region.

After the calcination treatment, the spectrum (“After treatment”) is radically different. The complete disappearance of the bands at 2860–2929 cm−1 is the most evident proof of the treatment’s success. This absence indicates that all the organic matter contained in the bone has been eliminated by combustion. This chemical change is directly correlated with the observed color change, where the powder turns from black (resulting from the carbonization of organic matter) to white, the characteristic color of purified hydroxyapatite.

Regarding the mineral phase, the characteristic vibration bands of the phosphate groups (PO43−), which are the signature of hydroxyapatite, are present in both spectra. These bands, located at 474, 565, 603, 959, 1031, and 1100 cm−1, are visibly sharper and better resolved after calcination [19,20]. This sharpening of the peaks testifies to a significant increase in the crystallinity and structural order of the apatitic phase, which transforms from a poorly crystalline biological apatite to a well-crystallized ceramic hydroxyapatite.

It is important to note that, although the organic matter is eliminated, some carbonate groups (CO32−) persist after the treatment, as evidenced by the absorption bands at 871, 1417, and 1460 cm−1. The presence of these bands indicates that the resulting hydroxyapatite is a carbonated hydroxyapatite (CHA), where carbonate ions are inserted into the crystal lattice, likely substituting for phosphate and hydroxyl sites. This characteristic is typical of biologically derived apatites and is considered beneficial, as the presence of carbonates can positively influence the behavior of hydroxyapatite in a biological environment, notably by enhancing its bioactivity and resorbability [21].

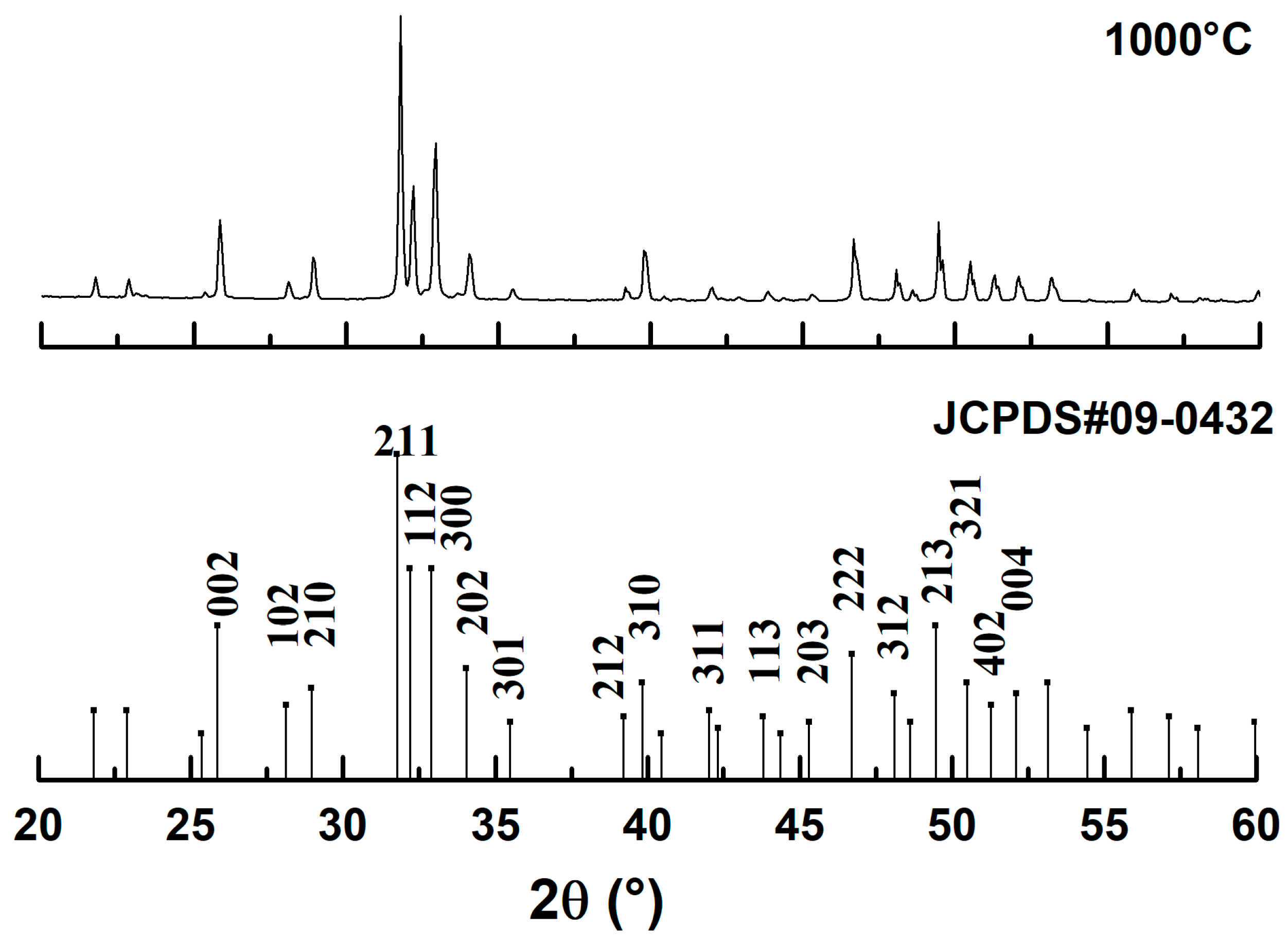

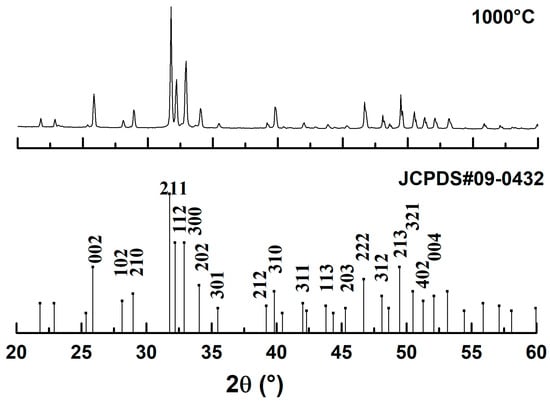

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the dromedary bone powder treated at 1000 °C, shown in Figure 4, provides conclusive evidence of the material’s phase and structure. A direct comparison of the experimental diffractogram with the JCPDS reference standard #09-0432 for hydroxyapatite (HAp) reveals an excellent match, as all observed diffraction peaks correspond precisely in position and relative intensity to the characteristic planes of the HAp crystal structure. Crucially, the complete absence of any additional peaks confirms that the synthesized material is of high phase purity, with no detectable secondary phases such as tricalcium phosphate (TCP) or calcium oxide (CaO) that could result from thermal decomposition. Furthermore, the sharp, intense, and well-defined nature of the diffraction peaks is a clear indicator of the material’s high degree of crystallinity, demonstrating that the heat treatment effectively transformed the poorly crystalline biological apatite into a well-ordered ceramic structure. Therefore, the XRD analysis validates that the calcination process successfully produced a monophasic and highly crystalline hydroxyapatite, confirming its identity and suitability as a high-quality starting material for biomedical applications.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffractogram of dromedary bone after heat treatment.

3.2. Coating Characterization

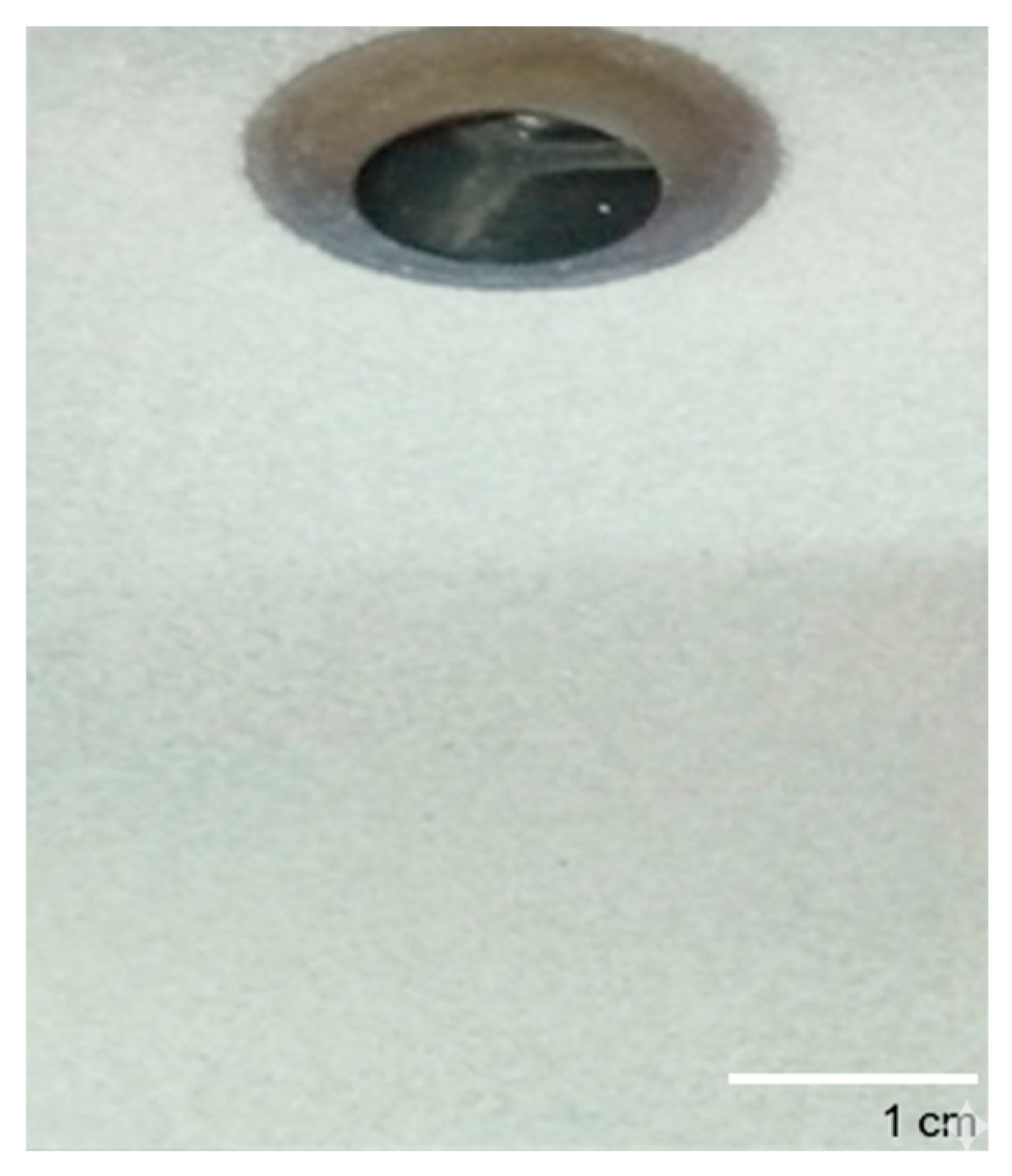

Figure 5 presents a macroscopic view of the coating produced from the naturally derived hydroxyapatite powder deposited onto a metallic substrate via the plasma spray technique. The initial visual inspection reveals a highly successful deposition process. The coating exhibits excellent macroscopic homogeneity, appearing as a uniform, consistent, light-colored layer that provides complete coverage over the entire substrate surface. There are no visible cracks, spalling, or areas of delamination observable by the naked eye. This visual uniformity is a primary indicator of a stable and well-controlled spray process, suggesting that the optimized feedstock powder was effectively and evenly melted and propelled onto the substrate.

Figure 5.

Picture of hydroxyapatite coating prepared from dromedary bone.

Beyond the visual appearance, the mechanical integrity and adhesion of the coating to the substrate are critical for its functional performance, especially in biomedical applications. A preliminary, qualitative scratch test was performed to assess coating adhesion. The test consisted of manually scratching the surface of the hydroxyapatite layer with a steel blade under moderate hand-applied pressure. The aim was not to measure quantitative adhesion strength, but rather to evaluate whether the coating could be easily detached or flaked off. The coating strongly resisted removal, with no visible delamination or spalling observed. This strong resistance is a compelling qualitative indicator of good adhesion between the hydroxyapatite layer and the underlying metallic substrate. Such robust bonding is essential to ensure the long-term stability of an implant under physiological loads and to prevent delamination, which could lead to implant failure and the release of particulate debris into the surrounding tissue.

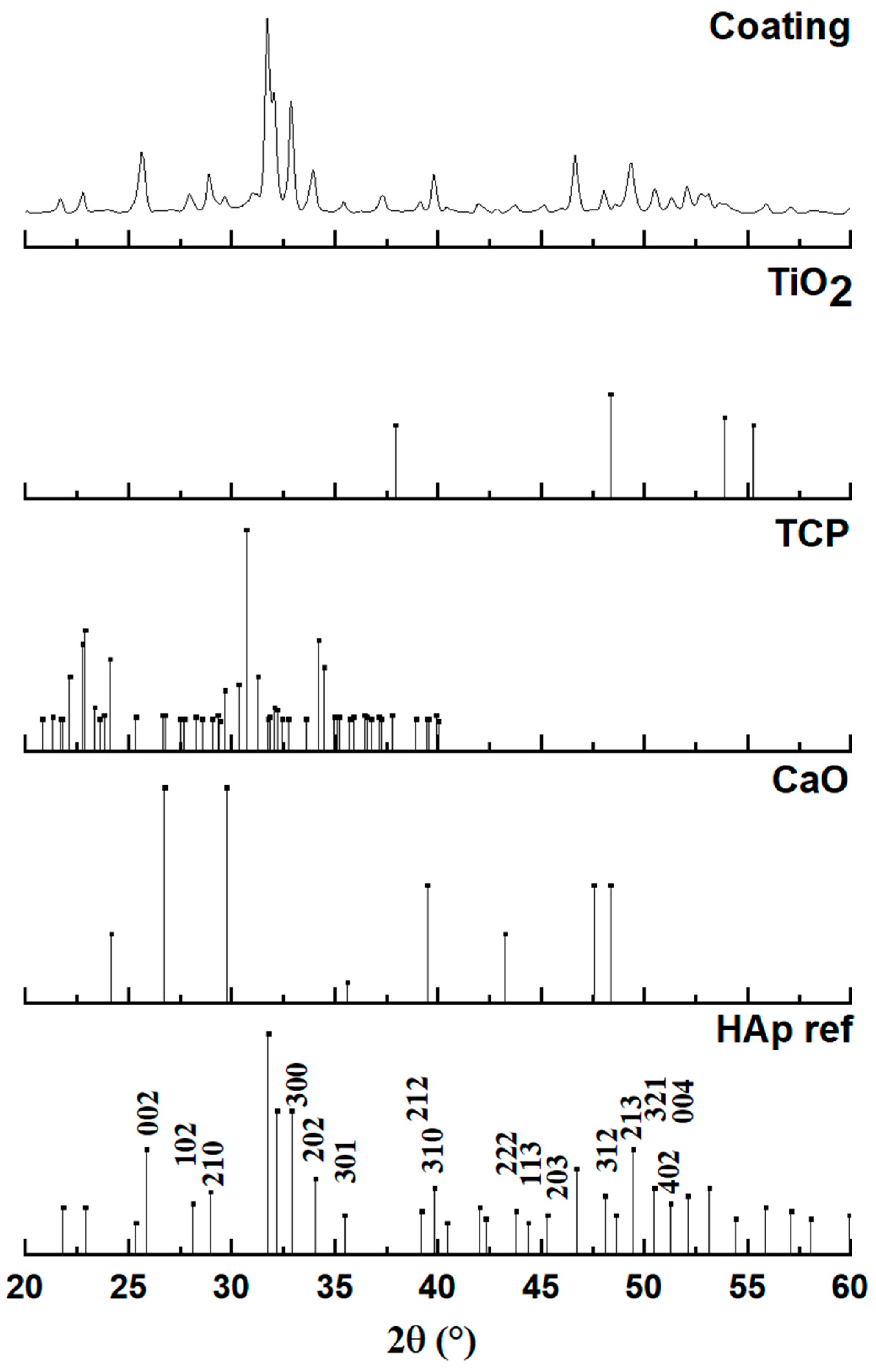

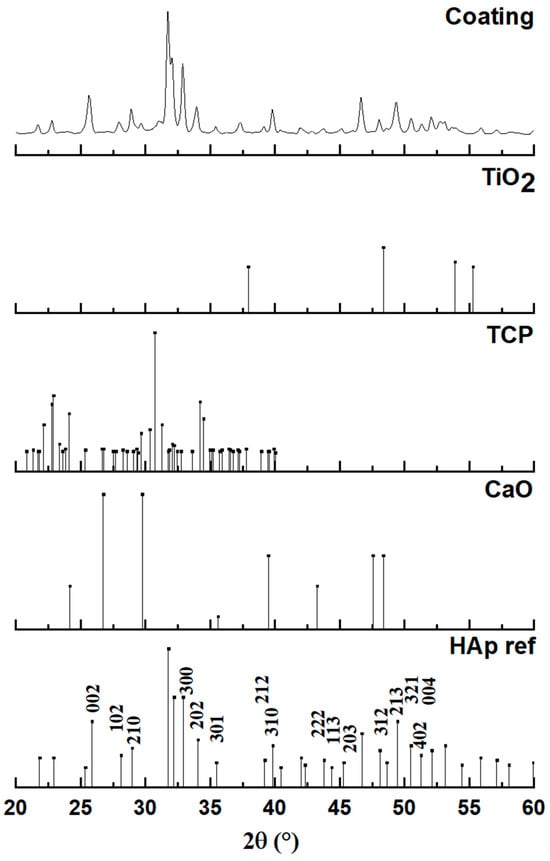

Figure 6 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern obtained from the plasma-sprayed coating, which is analyzed to determine its final phase composition after the high-temperature deposition process. The diffractogram of the coating is compared against standard reference patterns for hydroxyapatite (HAp), tricalcium phosphate (TCP), calcium oxide (CaO), and titanium oxide (TiO2) to identify all crystalline phases present. The analysis confirms that the primary constituent of the coating is indeed hydroxyapatite. The major diffraction peaks in the coating’s pattern align perfectly with the reference for HAp (JCPDS #00-009-0432), confirming its hexagonal crystal structure (space group P63/m). The peaks are observed to be both well-defined and relatively broad, which is a characteristic signature of a nanocrystalline material, indicating that the rapid solidification of molten droplets during spraying resulted in a structure composed of very fine crystallites.

Figure 6.

Diagram of a coating with hydroxyapatite powder obtained by plasma spraying.

However, a detailed examination of the coating’s diffractogram reveals that it is not a purely single-phase material. The presence of several additional, lower-intensity peaks indicates that some phase transformations occurred during the plasma spray process. The appearance of these secondary phases is a known consequence of subjecting hydroxyapatite to the extremely high temperatures within the plasma jet, which can cause partial thermal decomposition. By comparing the pattern to the reference standards, these additional peaks, such as those observed around 29.9°, 30.9°, and 37.5°, can be confidently identified. The analysis shows that the coating contains minor phases of tricalcium phosphate (TCP) and calcium oxide (CaO) in addition to the main HAp phase.

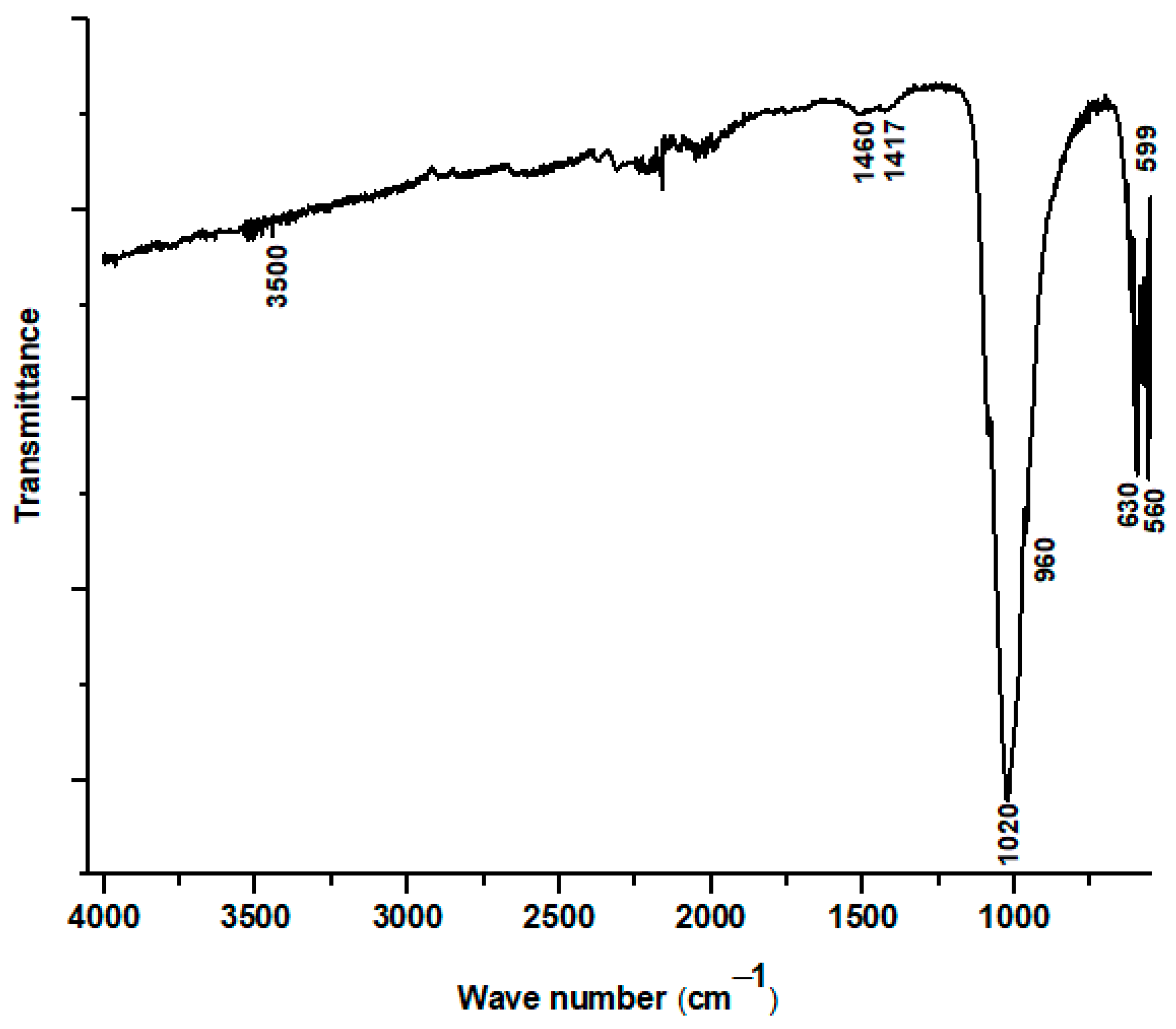

Figure 7 displays the Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) absorption spectrum of the material recovered by scraping the plasma-sprayed coating from the substrate. This analysis provides critical insight into the chemical bonding structure of the coating after it has undergone the extreme temperatures of the plasma spray process. The spectrum confirms that the primary component of the coating remains a calcium phosphate material, evidenced by the strong and well-defined absorption bands at 560, 599, 960, and 1020 cm−1. These peaks are the characteristic vibrational modes of the phosphate (PO43−) group, which is the fundamental building block of hydroxyapatite. Furthermore, the presence of a distinct absorption band at 630 cm−1, associated with the liberational (or wagging) mode of the hydroxyl (OH−) group, provides direct evidence that a hydroxyapatite structure was successfully formed and maintained in the final coating.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectrum of hydroxyapatite coating prepared from dromedary bone.

However, the FTIR spectrum also reveals significant chemical modifications resulting from the high-energy deposition process, corroborating the findings from the XRD analysis. A key observation is the absence of the broad OH− stretching band, which is typically located near 3500 cm−1. The disappearance of this peak, while the 630 cm−1 OH− liberational band remains, indicates a process of partial dehydroxylation. This suggests that a portion of the hydroxyl groups was driven out of the HAp lattice by the intense heat of the plasma, a common thermal decomposition pathway for hydroxyapatite.

Furthermore, a stark difference is noted when comparing this spectrum to that of the initial powder: the complete disappearance of the carbonate bands (previously seen at 871, 1417, and 1460 cm−1). This indicates that the carbonate groups, present in the naturally derived starting material, were thermally unstable and fully decomposed during plasma spraying. This decarbonation process, along with dehydroxylation, is directly linked to the formation of the secondary phases detected by XRD. Specifically, the loss of these functional groups is consistent with the decomposition of hydroxyapatite into calcium oxide (CaO), providing a clear chemical explanation for why CaO was identified as a minor phase in the coating.

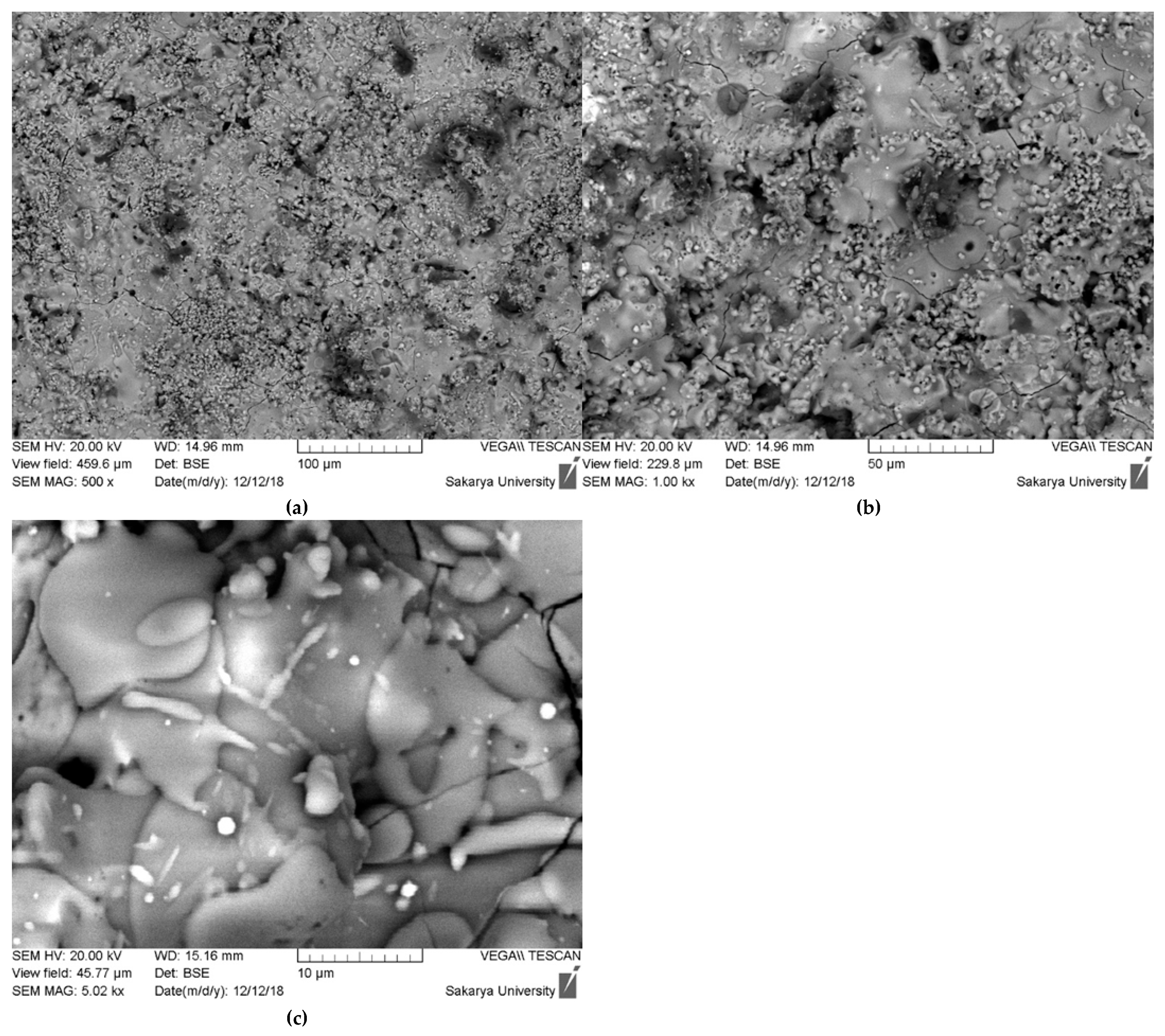

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images presented in Figure 8 provide a detailed, multi-scale examination of the surface morphology and microstructure of the plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coating. At lower magnifications (500× and 750×), the coating exhibits a characteristically rough and heterogeneous surface, which is typical for thermally sprayed ceramic layers. This topography is the result of the irregular stacking and arrangement of individual particles as they impact and solidify on the substrate, creating a complex surface that can be beneficial for promoting initial cell attachment in biomedical applications.

Figure 8.

SEM morphological surface of hydroxyapatite coating ((a) 100 µm, (b) 50 µm, (c) 10 µm).

Upon closer inspection at higher magnification (5.02 kx), the classic lamellar or “splat-based” microstructure inherent to plasma spray coatings becomes evident. The surface is composed of two primary features: fully melted regions and partially melted particles. The fully melted regions appear as smooth, flattened, pancake-like structures known as “splats.” These are formed when hydroxyapatite particles melt completely within the high-temperature plasma jet, then spread out and rapidly solidify upon impact with the substrate or previously deposited layers. In contrast, there are also smaller, globular particles visible on the surface. These are identified as non-fused or semi-fused particles, which retained much of their original particulate shape because they did not have sufficient time or energy to melt completely. Their presence is often linked to a broad particle size distribution in the feedstock powder, where larger particles may only undergo surface melting before reaching the substrate [22,23].

Furthermore, the SEM images reveal other critical microstructural features. A network of fine microcracks is clearly visible across the surface, particularly in the 750× and 5.02 kx images. These are cooling cracks, generated by the significant thermal stresses that arise from the rapid solidification and the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between the ceramic coating and the metallic substrate. While extensive cracking can be detrimental, a controlled network of microcracks can sometimes help to relieve residual stress. Additionally, the back-scattered electron (BSE) mode, which is sensitive to atomic number, shows distinct variations in contrast. The different shades of gray and the presence of small, bright white inclusions are the physical manifestation of the multiphase composition (HAp, TCP, and CaO) that was confirmed by the XRD analysis, with each phase having a slightly different average atomic number and density.

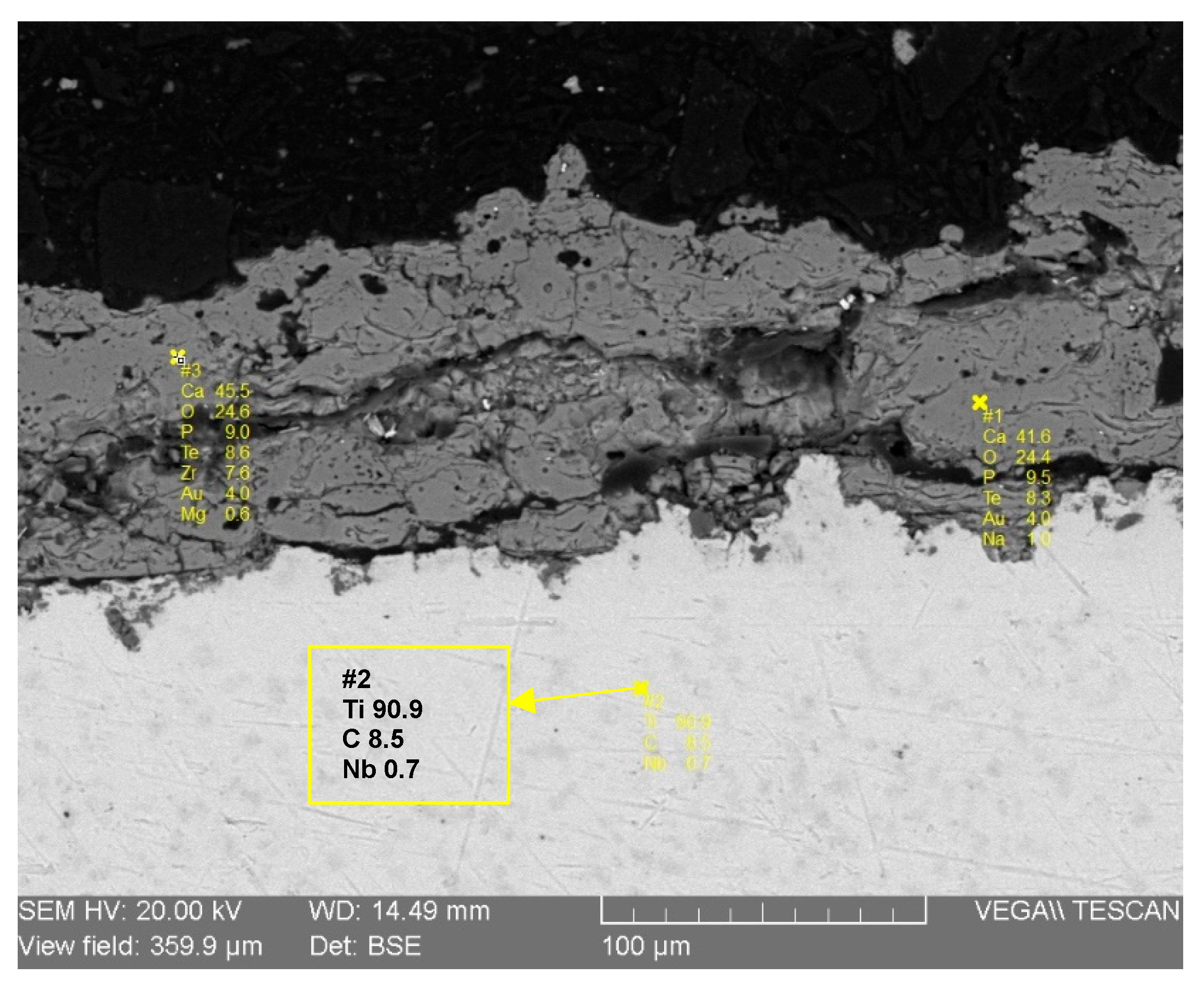

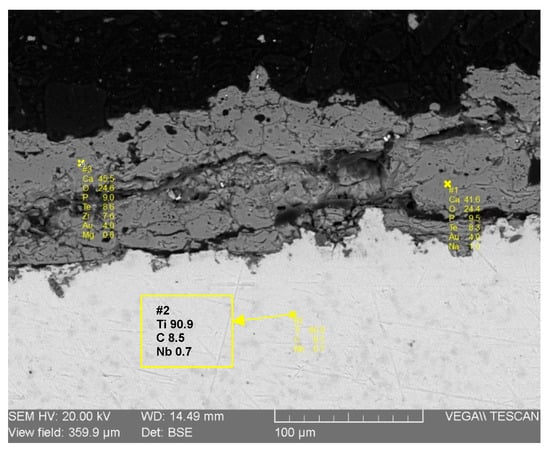

The cross-sectional analysis provides critical information regarding the coating’s chemical composition, internal microstructure, and its interface with the substrate. Figure 9 illustrates the results from Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) spot analyses performed on the coating. The elemental data confirms that the deposited layer is composed primarily of Calcium (41.6 wt%), Phosphorus (9.5 wt%), and Oxygen (24.4 wt%), which are the main constituent elements of hydroxyapatite. This finding is perfectly consistent with the previous XRD and FTIR results. Crucially, the EDS analysis also confirms the absence of any significant pollution elements, which validates the purity of the entire process, from the preparation of the raw bone material to the final plasma spray deposition. This chemical purity is paramount for ensuring the biocompatibility and safety of the implant coating.

Figure 9.

EDS-SEM analysis of hydroxyapatite coating.

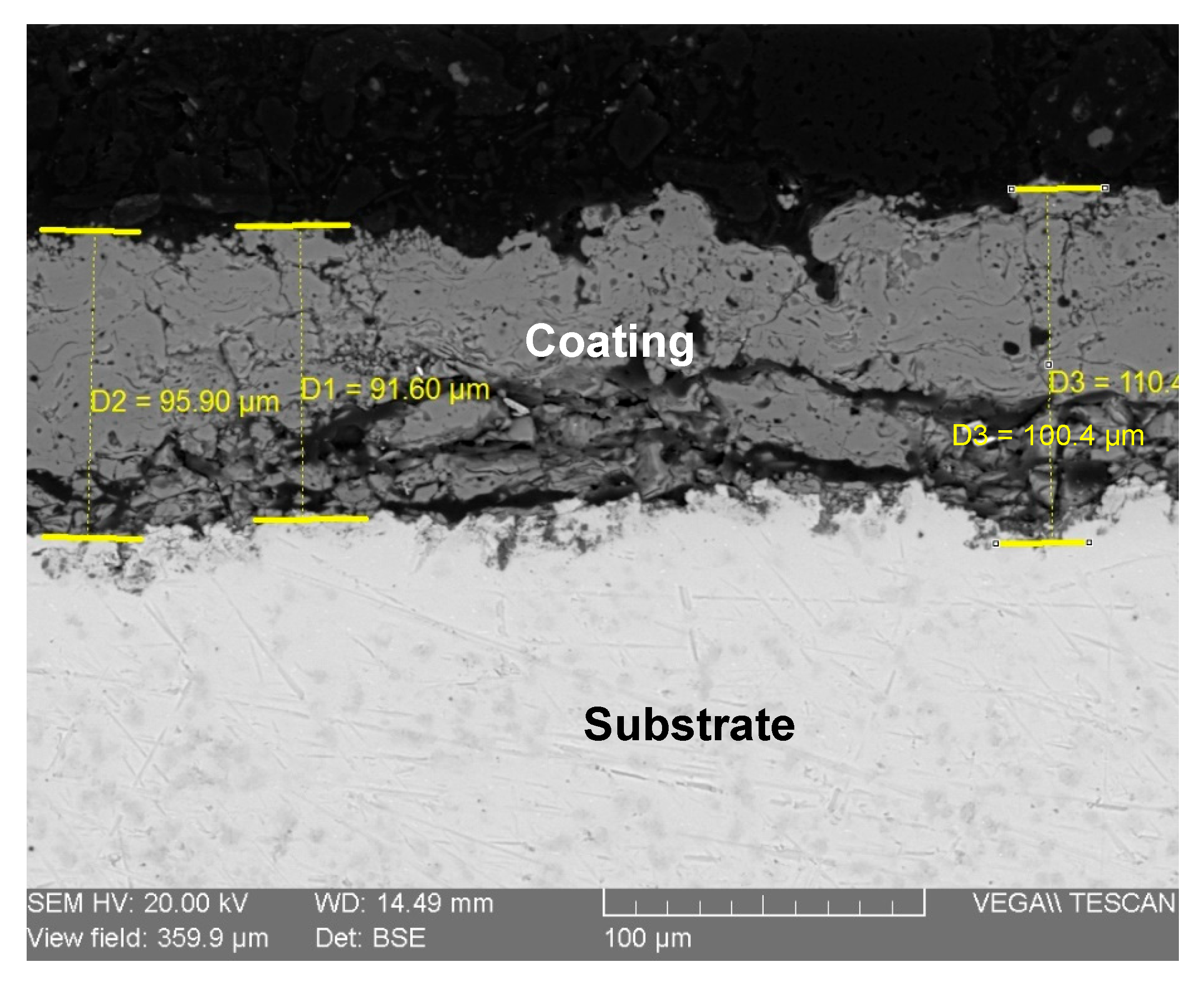

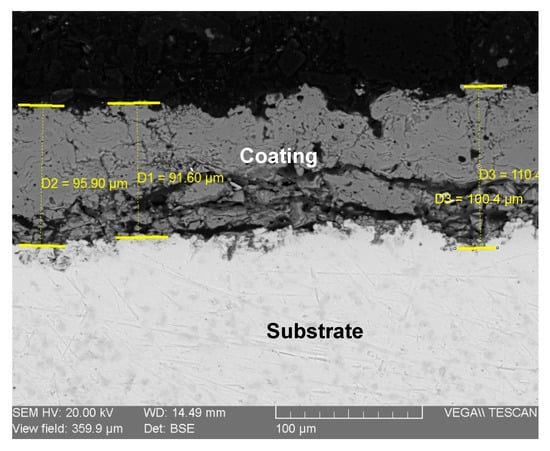

Figure 10 presents the cross-sectional SEM micrograph, which allows for a detailed assessment of the coating’s physical and structural characteristics. Dimensional measurements taken at various points across the section reveal a variable but consistent thickness. The average coating thickness was indeed approximately 95 µm. Based on our measurements presented in Figure 9, the coating thickness ranged from a minimum of 91 µm to a maximum of 110 µm. This thickness is well within the typical range for functional biomedical plasma-sprayed coatings, as supported by other research [24,25]. The image clearly shows a non-uniform coating-substrate interface, which is characteristic of deposition onto a grit-blasted surface. This roughness promotes strong mechanical interlocking between the coating and the substrate, which is a key factor in achieving the good adhesion that was observed qualitatively.

Figure 10.

SEM image of the coating cross-section (hydroxyapatite/Ti).

Furthermore, the internal microstructure of the coating is revealed in the cross-section. The layer is not fully dense, and the non-smooth surface, even after metallographic polishing, is a direct result of this internal porosity. The darker regions visible within the coating layer represent pores and inter-lamellar voids, which are inherent features of the plasma spray process. While high porosity can compromise mechanical strength, a certain degree of interconnected porosity, as seen here, is highly desirable for orthopedic applications. This porous structure provides a three-dimensional scaffold that facilitates the infiltration of biological fluids and encourages the ingrowth of bone cells (osteoblasts), leading to faster and more stable biological fixation (osseointegration) of the implant. Therefore, the observed microstructure is considered beneficial for the intended biomedical application [26].

4. Conclusions

The current research successfully presents dromedary bone waste as a non-negligible, low-cost, and sustainable resource for obtaining natural hydroxyapatite (HAp). This study uniquely demonstrates the feasibility of utilizing this underutilized natural source for the elaboration of biocompatible coatings on titanium dioxide substrates via the plasma spray method.

Through comprehensive characterization using XRD, FTIR, and SEM, the following key technical achievements and indicators were observed:

- HAp Powder Characteristics: The heat treatment process at 1000 °C for 36 h effectively produced a pure HAp powder from dromedary bone, as confirmed by XRD showing no additional phases. FTIR analysis confirmed the successful elimination of organic matter, with only carbonate groups remaining, which can influence biological behavior. SEM revealed that prolonged sintering at 1000 °C for 24 h significantly modified particle morphology to a more spherical shape and increased particle size, optimizing it for the plasma spraying process.

- Coating Homogeneity and Adhesion: Macroscopic observations indicated a good distribution and homogeneity of the natural HAp particles across the metallic substrate surface. Furthermore, the notable difficulty in manually scraping the deposit provided qualitative evidence of good adhesion of the coating to the titanium substrate.

- Coating Phase Composition: X-ray diffraction of the coating confirmed that the main deposited phase is hydroxyapatite, exhibiting a nanocrystalline hexagonal crystal structure. However, the presence of minor additional phases, specifically calcium oxide (CaO) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP), was noted, suggesting partial decomposition of HAp during the high-temperature plasma spraying process. FTIR analysis of the coating also indicated the absence of carbonate bands and partial dehydroxylation, further supporting HAp decomposition and the formation of CaO.

- Coating Microstructure and Thickness: SEM morphological analysis revealed a characteristic lamellar microstructure of thermal spray coatings, comprising fully melted (splat) particles alongside some unmelted or semi-fused globular particles, resulting in a rough, porous surface. This porous structure, with an average deposition thickness of approximately 95 µm (as measured from cross-sectional SEM), is potentially beneficial for enhancing osteointegration in biomedical applications.

This research contributes to sustainable biomaterial development by transforming an agricultural byproduct into a high-value material, offering an alternative to costly synthetic or less sustainable natural HAp sources. The study provides critical foundational data for the subsequent development of natural HAp coatings for metallic implants, demonstrating a promising pathway towards enhancing the biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of orthopedic and dental devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K. and A.G.; methodology: M.K. and A.G.; validation: M.K., A.G., L.B., Y.A., I.A., K.H., C.B. and E.H.K.; formal analysis: M.K., A.G., L.B., Y.A., I.A., K.H., C.B. and E.H.K.; investigation: All authors; resources: M.K. and A.G.; data curation: M.K., A.G., L.B., Y.A., I.A., K.H., C.B. and E.H.K.; writing—original draft preparation: M.K. and A.G.; writing—review and editing: M.K. and A.G., K.H., C.B. and E.H.K.; visualization: All authors; supervision: K.H., C.B. and E.H.K.; project administration: K.H., C.B. and E.H.K.; funding acquisition: C.B. and E.H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Titsinides, S.; Agrogiannis, G.; Karatzas, T. Bone grafting materials in dentoalveolar reconstruction: A comprehensive review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2019, 55, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asri, R.; Harun, W.; Hassan, M.; Ghani, S.; Buyong, Z. A review of hydroxyapatite-based coating techniques: Sol–gel and electrochemical depositions on biocompatible metals. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 57, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmenev, R.A. A review of plasma-assisted methods for calcium phosphate-based coatings fabrication. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 2035–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadanbaz, S.; Dias, G.J. Calcium phosphate coatings on magnesium alloys for biomedical applications: A review. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Wang, R. Surface modifications of bone implants through wet chemistry. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 2309–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, G.; Scrivani, A.; Fini, M.; Giardino, R. Biomedical coatings to improve the tissue-biomaterial interface. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2004, 27, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Thevenot, P.; Hu, W. Surface chemistry influences implant biocompatibility. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Michiardi, A.; Castano, O.; Planell, J. Biomaterials in orthopaedics. J. R. Soc. Interface 2008, 5, 1137–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaraia, K.; Mashtalyar, D.; Piatkova, M.; Pleshkova, A.; Imshinetskiy, I.; Gerasimenko, M.; Belov, E.; Kumeiko, V.; Kozyrev, D.; Fomenko, K. Antibacterial HA-coatings on bioresorbable Mg alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 1965–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, K.; Okido, M. Hydroxyapatite coating of titanium implants using hydroprocessing and evaluation of their osteoconductivity. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2012, 2012, 730693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodard, J.R.; Hilldore, A.J.; Lan, S.K.; Park, C.; Morgan, A.W.; Eurell, J.A.C.; Clark, S.G.; Wheeler, M.B.; Jamison, R.D.; Johnson, A.J.W. The mechanical properties and osteoconductivity of hydroxyapatite bone scaffolds with multi-scale porosity. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizundia, E.; Luzi, F.; Puglia, D. Organic waste valorisation towards circular and sustainable biocomposites. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5429–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, M.S.F.; Abdullah, H.Z.; Idris, M.I.; Wahap, M.A.A. Extraction of natural hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications—A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarup, J.S.; Thomas, R.; Rucharitha, J.; Arunkumar, V.R.; Vasanthi, V. Eggshell-derived hydroxyapatite as a biomaterial in dentistry: A scoping review of synthesis, properties and applications. Evid.-Based Dent. 2025, 26, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, B.; Mirhadi, S.M.; Mehrazin, M.; Yazdanian, M.; Motamedi, M.R.K. Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Hydroxyapatite Using Eggshell and Trimethyl Phosphate. Trauma Mon. 2017, 22, e36139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghedjemis, A.; Benouadah, A.; Fenineche, N.; Ayeche, R.; Hatim, Z.; Drouiche, N.; Lounici, H. Preparation of Hydroxyapatite from Dromedary Bone by Heat Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2019, 13, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghedjemis, A.; Ayeche, R.; Benouadah, A.; Fenineche, N. A new application of Hydroxyapatite extracted from dromedary bone: Adsorptive removal of Congo red from aqueous solution. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2021, 18, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.Y.; Hamdi, M.; Ramesh, S. Properties of hydroxyapatite produced by annealing of bovine bone. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberko, K.; Bućko, M.M.; Brzezińska-Miecznik, J.; Haberko, M.; Mozgawa, W.; Panz, T.; Pyda, A.; Zarębski, J. Natural hydroxyapatite—Its behaviour during heat treatment. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamian, E.; Khandan, A.; Eslami, M.; Gheisari, H.; Rafiaei, N. Investigation of HA Nanocrystallite Size Crystallographic Characterizations in NHA, BHA and HA Pure Powders and their Influence on Biodegradation of HA. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 829, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Vieira, S.; Olhero, S.; Pina, S.; da Cruz e Silva, O.; Ferreira, J. Synthesis, mechanical and biological characterization of ionic doped carbonated hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate mixtures. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Liao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Tyagi, R.; Liu, W. Tribological behaviour of titanium alloy modified by carbon–DLC composite film. Surf. Eng. 2015, 31, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demnati, I. Développement et Caractérisation de Revêtements Bioactifs D’apatite Obtenus par Projection Plasma à Basse Énergie: Application Aux Implants Biomédicaux. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse-INPT, Toulouse, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Derradji, F.Z.; Labaïz, M.; Bououdina, M.; Ourdjini, A.; Montagne, A.; Iost, A. Porous plasma sprayed bioceramic (Ca10 (PO4). 6 (OH)2) coated Ti6Al4V: Morphological, adhesion and tribological studies. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 095401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszek, R.; Pawlowski, L.; Gengembre, L.; Laureyns, J.; Le Maguer, A. Microstructure of suspension plasma sprayed multilayer coatings of hydroxyapatite and titanium oxide. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 7432–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, H.F.; Guidara, A.; Danlos, Y.; Bouaziz, J.; Coddet, C. Synthesis and characterization of alumina-fluorapatite coatings deposited by atmospheric plasma spraying. Mater. Lett. 2016, 185, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).