Abstract

Fullerenes are promising drug candidates, but they are virtually insoluble in water. Surface hydroxylation of fullerenes and their encapsulation in nanocarrier systems, such as dendrimers, can be used to increase their solubility. However, hydroxylated fullerene (hydroxyfullerene, fullerenol) has lower bioactivity than fullerene. Our previous research showed that fullerene is encapsulated by the Lys-2Gly dendrimer. This study demonstrates, for the first time, that hydroxylated fullerenes C60(OH)n with n = 12, 24, 36 form complexes with the same dendrimer. All these fullerenols are encapsulated near the dendrimer’s center, similar to fullerene. Surprisingly, the complex’s structure remains stable even at the maximal hydroxylation (n = 36), despite a significant reduction in hydrophobicity of the fullerene surface. We demonstrated that this stability results from an increase in the number of hydrogen bonds between the dendrimer and the fullerenol with increasing n. Thus, we established that the mechanism of complex formation changes from hydrophobic interactions to hydrogen bonding as hydroxylation increases. This means that simultaneous partial hydroxylation of the fullerene and encapsulation within a water-soluble dendrimeric nanocarrier enhances its solubility in water. This combined approach enables the use of less hydroxylated fullerene derivatives to achieve desired solubility while maintaining higher biological activity.

1. Introduction

Fullerenes are bioactive molecules that are insoluble in water [1,2]. They are considered a promising system for drug delivery [3,4,5], but clinical trials have only recently begun [6]. Fullerenes have antioxidant [7,8,9], antibacterial [10], antiviral [11], and antitumor [12,13,14] activities. To improve the solubility of fullerene, its water-soluble derivatives containing hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amino groups are often used [15,16]. To address the poor solubility of fullerenes, several strategies have been developed. Conjugation with cyclodextrins, peptides, or polyethylene glycol spacers has been shown to significantly enhance their solubility [17,18,19,20,21]. Alternatively, encapsulation within carbon nanotubes or liposomes has been proposed as a delivery method [22,23,24].

Dendrimers are hyperbranched, monodisperse nanostructures characterized by a precise size and architecture and by a multitude of surface groups. They are used as nanocontainers in biomedical applications, particularly in drug and gene delivery [25,26]. Dendrimers can encapsulate bioactive molecules via various interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, electrostatic) [4], forming complexes that protect the cargo and enhance its bioavailability [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. The ability to tailor their chemical structure allows for the design of delivery systems with controlled and targeted release [34,35]. Dendrimers were used for the delivery of enoxaparin [36], berberine [37], quercetin [38], resveratrol [39], curcumin [40], doxorubicin [41,42] and paclitaxel [43,44]. Conjugates of dendrimers with fullerenes have also been developed [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59].

While well-characterized synthetic dendrimers like polyamidoamine (PAMAM) and polypropylene imine (PPI) are promising delivery systems [36], their clinical application is often limited by toxicity and a restricted number of modification sites. To overcome these drawbacks, strategies such as PEGylation, acetylation, and conjugation with amino acids or peptides have been employed to modify the terminal groups [60,61,62,63,64,65]. In this context, peptide dendrimers offer a distinct advantage due to their natural amino acid composition, which inherently improves their biocompatibility profile [66,67]. Polylysine dendrimers are safe and biodegradable [68,69,70,71,72,73]. They exhibit antibacterial [74,75,76,77,78], antiviral [79,80], and antiangiogenic [81,82,83,84] properties. A key advantage of peptide dendrimers is their synthetic versatility; they can be constructed from virtually any amino acid residues, both on the surface and within their core, to optimize the encapsulation of bioactive molecules [85,86,87,88,89]. This capability addresses issues of poor solubility and aggregation, enabling the use of lower drug doses [90]. Furthermore, in combination therapies, peptide dendrimers can produce a synergistic effect, particularly against cancer cells [91].

Numerous studies have also been performed using the molecular dynamics (MD) method to study the conjugation of dendrimers with bioactive molecules [92,93,94,95,96,97], in particular, with fullerenes [98,99,100]. But there is a notable lack of studies in the literature regarding dendrimer–fullerenes and dendrimer–fullerenols host–guest complexes [101,102,103,104]. MD simulations of dendrimer–fullerene interactions were performed in our previous work [105]. It was shown that fullerenes effectively penetrate both second- and third-generation lysine dendrimers, as well as a second-generation peptide dendrimer with repeating Lys-2Gly units, forming stable complexes with them.

In this paper we investigate the interactions of the Lys-2Gly dendrimer with fullerenol. In view of both the anticancer and antiamyloid activity [106,107] of both molecules, a synergistic effect [108] of their combination can be assumed. A further benefit of peptide dendrimers lies in the adjustable nature of their host–guest interactions. Inserting residues with different hydrophobicity [109,110,111,112] enables optimization of the hydrophobic environment for fullerenol encapsulation within the dendrimer. Encapsulating partially hydroxylated fullerene (i.e., fullerenol) within a dendrimer allows us to use fewer hydroxyl groups to achieve fullerene solubility, keeping its biological activity.

2. Model and Method

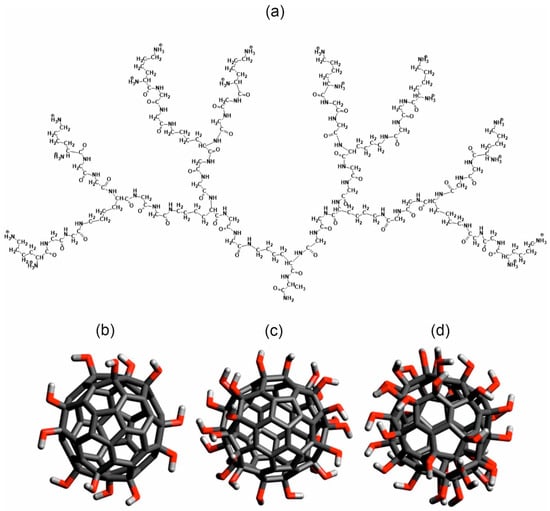

In this work, we have studied the formation of a complex between lysine-based peptide dendrimers and fullerenol in an aqueous solution using the molecular dynamics (MD) method. MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS package [113]. AMBER-99SB-ILDN [114] was used as a force field. We considered a second-generation lysine-based dendrimer with double glycine (2Gly) spacers between lysine branching points (Lys-2Gly dendrimer). We utilized full-atom models of this dendrimer and fullerenols (see Figure 1). Table 1 shows structural parameters of the Lys-2Gly dendrimer. The peptide dendrimer under consideration contains the following (see Figure 1): 1 alanine residue (in the core), 7 branched (internal) lysine residues (branching points), 28 glycine residues (2 residues between each adjacent pair of branches in the dendrimer) and 8 terminal lysines with two positively charged NH3+ end groups in each (one of these two NH3+ groups is the N-terminus of the peptide chain (which is charged at normal pH), the other is in the side group of this terminal lysine, which is also charged at normal pH). The total charge of the dendrimer is 16 (8 terminal lysines with a charge of +2 in each), and the charge of fullerenol is zero; therefore, in order to achieve the electroneutrality of the entire system, which is required for the correct operation of the MD method, 16 negatively charged chlorine counterions were added to the system. The simulated system was placed in a periodic cubic simulation cell filled with 23,682 water molecules (the TIP3P model was used).

Figure 1.

(a) Molecular structures of chemical bonds of Lys-2Gly dendrimer (generation G2) and hydroxylated fullerenes (b) C60(OH)12, (c) C60(OH)24, and (d) C60(OH)36. Carbon atoms and C-C bonds shown by dark gray color, oxygens by red, and hydrogens by light gray.

Table 1.

Molecular weight (Md) and nominal charge of the dendrimer (Q), the number of positively charged NH3+ groups (NH3+) in the terminal lysines, and the number of glycine amino acid residues (NGly) in the dendrimer spacers.

The equilibrated initial conformations of the dendrimers were taken from a previous work, which investigated a single dendrimer in water [115]. Initially, the center of mass of the dendrimer was placed in the center of a periodic cubic cell, and the fullerenol was placed in the middle between this center and one of the six faces of the cubic cell. For each type of fullerenol (with n = 12, 24, or 36 OH groups), three of these six possible initial positions of the fullerenol were selected to start three independent MD calculation runs. In this particular study, we designate these three initial positions of the fullerenol as “left”, “back”, and “top”, corresponding to the direction of displacement of fullerenol relatively center of the periodical cube.

The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation included the preliminary steps: (1) the energy minimization of the isolated dendrimer and fullerenol molecules; (2) the immersion of the molecules in an aqueous solution with counterions; and (3) the energy minimization of the system. Then, the initial MD simulation in NVT ensemble at temperature T = 300 K for initial equilibration was carried out as described in detail in Ref. [115]. The size of the cubic periodic cell was 9 nm. Main MD calculations were carried out in the NPT ensemble at normal condition (temperature T = 300 K and pressure 1 atm) and consisted of two trajectories (first one at times t = 0–250 ns and second one (it was a continuation of the first trajectory) at times t = 250 ns–500 ns of full 500 ns calculations). The formation of the dendrimer–fullerenol complex was studied using the first trajectory and the calculation of average values of the complex was performed using the second trajectory. We used, for analysis of trajectories, both GROMACS tools and computational codes previously developed by the authors for polymers [116,117,118,119,120,121] and dendrimers [122,123,124,125,126].

3. Results

3.1. Formation of the Dendrimer–Fullerenol Complex

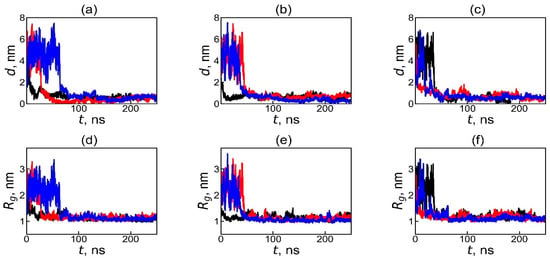

The formation of the dendrimer–fullerenol complex was evaluated by analyzing the time dependences of the distance d between dendrimer and fullerenol, as well as the time dependences of the size (radius of gyration Rg) of the subsystem, consisting of all dendrimer and fullerenol atoms. Calculation of d was performed as follows: (1) At each time moment, the position of the center of mass is calculated in Cartesian coordinates (x,y,z) in three-dimensional space for the first molecule (x1,y1,z1) and for the second molecule, (x2,y2,z2) and (2) the distance between these two points in space is calculated, as usual, as d = sqrt[(x1 − x2]2 + (y1 − y2)2 + (z1 − z2)2]. This calculation is performed by standard function gmx distance of Gromacs package. The time dependences of d are shown in Figure 2. Before the simulation, the fullerenol was positioned outside the dendrimer, far from its center of mass. After the first contact with the dendrimer, the value of distance d either goes to plateau almost immediately (see black curves on Figure 2a,b and red curve on Figure 2c) or fluctuate strongly during some time t between 10 and 70 ns (see the other two curves on the same plots), but a rapid step-like decrease in the d(t) value is observed for all curves sometime within this 10–70 ns. Then, the value of distance reaches a plateau value which is less than 1 nm with small root-mean-square (see Figure 2a–c and Table 2). The step-like decrease in d(t) indicates that all three types of fullerenols C60(OH)n (n = 12, 24 and 36) are captured by the dendrimer within the first 10–70 ns, leading to the formation of stable dendrimer–fullerenol complexes.

Figure 2.

The time dependences of the instantaneous value of the distance d between the centers of mass of the dendrimer and fullerenol molecule in the dendrimer–fullerenol systems: (a) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)12, (b) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)24, and (c) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)36 during the first 250 ns of the calculation, and (d–f) the time dependences of the sizes (radii of gyration, Rg) for these systems, respectively. The black, red, and blue curves correspond to the initial positions of the fullerenol—“left”, “back”, and “top”—relative to the center of periodic box which coincides with center of mass of the dendrimer at time t = 0.

Table 2.

Average values of asphericity (α), size (Rg) of Lys2Lys and complex containing both Lys2Lys and fullerenol, and the distance (d) between dendrimer and fullerenol after complex formation (averaging through interval t = 250–500 ns where dendrimer and fullerenol always stay together in stable complex). For comparison, the data for the Lys-2Gly and its complex with fullerene C60 previously reported in Refs. [105,115] are also provided.

To analyze the formation of the dendrimer–fullerenol complex, we calculated the radius of gyration, Rg [127], for subsystem containing all dendrimer and fullerenol atoms during all time moments belonging to first 250 ns of simulation (independently on do dendrimer and fullerenol contact with each other or not).

where mi and ri are the mass and radius vector of the i-th atom of each dendrimer and each fullerenol atom relative to the center of mass of the subsystem consisting of all atoms of the dendrimer and all atoms of fullerenol (at any time moment including times when they are not in complex with each other), and Ntot is the total number of atoms in both the dendrimer and the fullerenol. The size of the subsystem Rg(t) in Figure 2d–f demonstrates similar behavior with that of the distance between dendrimer and fullerenol d(t) curves for the same trajectories (Figure 2a–c). In all systems, Rg has large value at t = 0 because at this time fullerenol is far from the dendrimer, strongly fluctuates between 10 ns and 70 ns (depending on curve (initial position of fullerenol)), and then decreases sharply at different times within the first 10–70 ns of the simulation (depending on initial position of fullerenol). Following the drop, the Rg values fluctuate slightly, and the average values (from 1.05 to 1.13 nm) quickly reach a plateau and then remain almost unchanged over time. Thus, the similar behavior of the time dependences of d and Rg confirms the formation of the dendrimer–fullerenol complex (for all studied systems and all initial positions of fullerenol) within first 70 ns.

3.2. Analysis of the Structure and Properties of a Stable Dendrimer–Fullerenol Complex

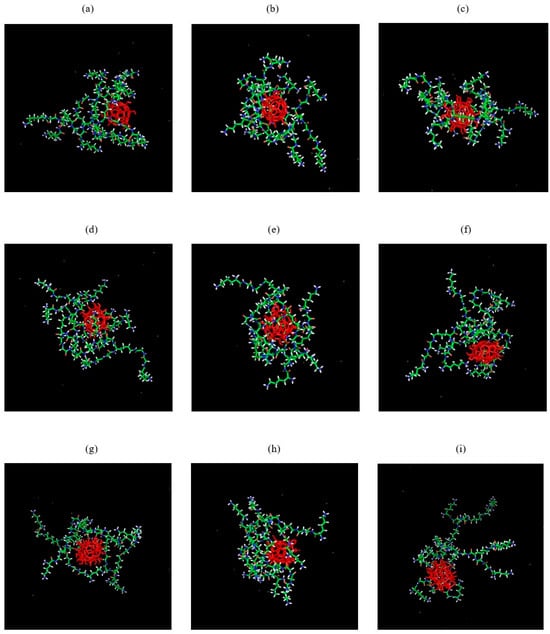

The relative positions of the dendrimer and fullerenol molecules in the complex at t = 500 ns of the simulation are shown in Figure 3. Analysis of snapshots similar to Figure 3 at intermediate times demonstrates that, following the establishment of the plateau in both distance d(t) and Rg(t) (see Figure 2), the fullerenol and dendrimer remain in contact. After the formation of the stable complexes (at t = 250–500 ns), some parameters of the obtained complexes, as well as the dendrimer and fullerenol molecules, were calculated (see Table 2) to obtain more precise quantitative confirmation of this qualitative picture.

Figure 3.

The pictures of Lys2Gly–fullerenol systems at time t = 500 ns of MD calculations: (a–c) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)12, (d–f) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)24, (g–i) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)36 for three different initial positions (“left”, “back”, and “top”, respectively) of the fullerenol in each system.

The asphericity of the dendrimer and complexes were calculated as described in Refs. [128,129]:

where l1, l2, and l3 are the eigenvalues of the inertia tensor of the dendrimer or complex. If the molecule or complex is spherical, then all eigenvalues l1, l2, and l3 are equal, and the asphericity is 0. According to Table 2, the asphericity of Lys2Gly dendrimer and all our complexes is less than 0.01, indicating a nearly spherical shape of both Lys2Gly dendrimer and its complexes with fullerenols. This finding is in good agreement with results for Lys-2Gly dendrimer and its complexes with fullerenes C60 and C70 in an aqueous solution, which also exhibited similarly very small asphericity values [105].

Table 2 shows that the average sizes <Rg> of the Lys2Gly dendrimer in the complex (is close to 1.2 HM for all three types of fullerenols) and the entire complex remains almost unchanged in size (Rg is close to 1.1 nm for all fullerenols) despite variation in the number of OH groups of fullerenol in this complex. This smaller Rg of the complex in comparison with size Rg of dendrimer for all types of fullerenol is understandable because all three fullerenols are located very close to center of mass of dendrimer.

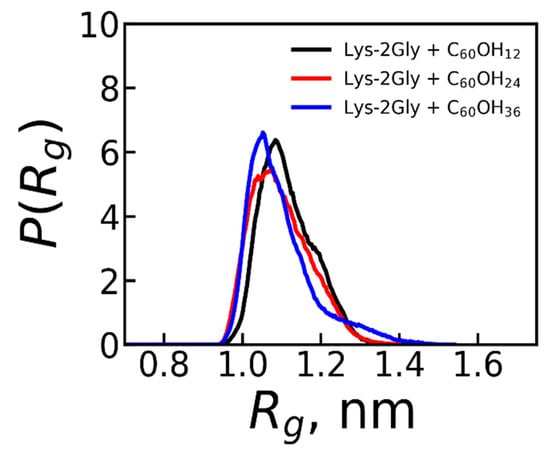

Despite the fact that the average value of Rg size of the complex is near the same for all three types of fullerenol, the distribution function of this value P(Rg), which describes how many times each value of Rg appears during the simulation (see Figure 4), is different for different fullerenols. At the same time, the positions of peaks of this distribution for all types of fullerenols are rather close to each other and to the average value of <Rg> = 1.1 nm for each system (see Table 2).

Figure 4.

The distribution function of size (Rg) of the complexes of the Lys-2Gly with C60(OH)12, C60(OH)24, and C60(OH)36 obtained from the second part of the trajectory (Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns.).

The average depth of fullerenol encapsulation within the dendrimer is correlated with the average dendrimer–fullerenol distance d in the complex (see Table 2). For all complexes studied, this distance is close to 0.5 nm and is practically independent of the hydroxylation degree of fullerenol (n).

3.3. Radial Density Profile

As demonstrated above, the stable dendrimer–fullerenol complexes exist in all the systems considered. To characterize the internal structure of these complexes, we calculated the radial density profile function

where ρ(r) is the average density of a thin spherical layer of all or specific atoms at a distance r from the center of mass of the dendrimer, and <m(r)> is the average total mass of atoms in the same layer of volume V(r). Since the number of atoms in fullerenol is significantly smaller than in the dendrimer, we considered how deeply fullerenol penetrates into the dendrimer and how it changes the distribution of the dendrimer’s atoms in the complex compared to a single dendrimer. For this, we calculated the radial density profile of three types of atoms: (a) only fullerene atoms, (b) only dendrimer atoms, and (c) all atoms of the complex, i.e., both dendrimer atoms and fullerene atom. The ρ(r) dependencies are shown in Figure 5.

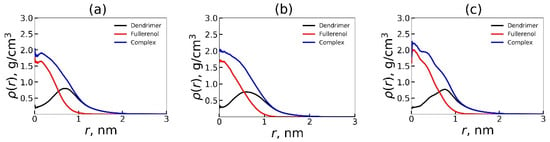

Figure 5.

The radial density profile functions for the atoms of Lys-2Gly dendrimer, fullerenol, and the dendrimer + fullerenol complex relatively center of mass of dendrimer: (a) C60(OH)12, (b) C60(OH)24, (c) C60(OH)36. The density profiles were averaged over three different initial positions (“left”, “back”, and “top”) of the fullerenol relative to the center of cubic simulation cell. Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns.

Figure 5a–c show that the dendrimer exhibits similar encapsulation efficacy of all three type of fullerenols. The radial dependence of density profile of fullerenol relative to the dendrimer center of mass is very similar but slightly differs between the fullerenols with different numbers of OH groups. In all cases, the radial density profile for fullerenol (red curve) has a maximum at r = 0. Thus, the fullerenols are located at the center of mass of the dendrimer, thereby expelling the dendrimer atoms (black curve) from center toward periphery. Consequently, the maximum of the density profile for dendrimer atoms is shifted by fullerenol approximately to r = 0.7–0.8 nm from the center of mass of dendrimer, creating a spherical cloud of dendrimer atoms around fullerenol.

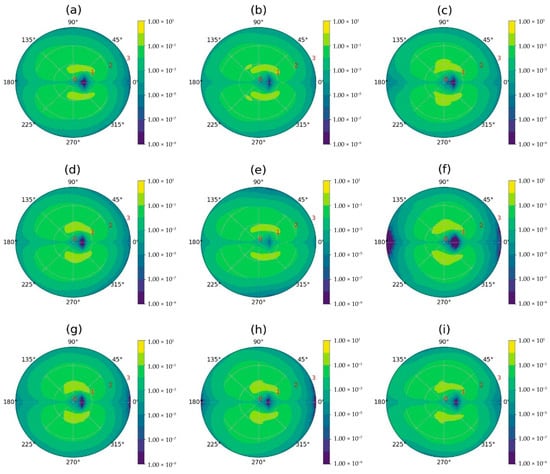

We also constructed two-dimensional (2D) sector-radial mass distributions of the dendrimer relative to its center of mass (Figure 6) to determine whether the interaction between the dendrimer and fullerenol depends only on the radial distance r or also on the angles in spherical coordinates [130]. In Figure 6, the dark blue region, indicating low dendrimer atom density, coincides with the position of the fullerenol’s internal cavity. At the same time, the highest density (yellow) of dendrimer atoms exists around fullerenol, forming two radial areas of almost permanent contact with it; but they do not fully isolate fullerenol from water. However, the dendrimer atoms located in lower density (yellow-green and green regions) surround the fullerenol molecule and partially protect it from contact with water. The findings demonstrate that the Lys-2Gly dendrimer encapsulates all studied fullerenols despite the different number of hydrophilic OH groups (n = 12, 24, and 36).

Figure 6.

2d-sectoral-radial distribution of the dendrimer mass relative to its center of mass. The first column of the images (a,d,g) corresponds to the Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)12 system, the second column (b,e,h) to the Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)24 system, and the third column (c,f,i) to the Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)36 system. The rows correspond to the initial positions of fullerenol relative to the dendrimer: (a–c) left, (d–f) back, and (g–i) top. The sphere was partitioned into spherical sectors for the sector-radial distribution functions, with its center defined as the dendrimer’s center of mass and the sectors calculated based on the vector to the fullerenol’s center of mass, following the method described in [130]. Each spherical sector is divided into upper and lower parts. The 2D plot represents dendrimer atom density (yellow: high, blue: low) as a function of radial distance (red numbers, in nm) and angle from the dendrimer’s center of mass. Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns.

3.4. Electrostatic Interactions in Dendrimer–Fullerenol Complex

In this section, we studied how the number of OH groups in encapsulated fullerenol influences the electrostatic characteristics of the dendrimer–fullerenol complex. We calculated the radial distribution of charges of the dendrimer together with counterions, q(r). The electrostatic potential, ψ(r), was obtained by numerically solving the Poisson equation using q(r) (Figure 7) [131,132,133]. Table 3 provides the average electrostatic characteristics, the number of hydrogen bonds, and number of hydrophobic contacts between dendrimers and fullerenols in the system. Hydrophobic contacts defined as carbon–carbon interactions between the dendrimer and fullerenol were quantified using a local criterion, Rlc, below ≈ 0.57 nm. The distance Rlc was obtained from the formula:

where kLJ = 21/6 is the Lennard-Jones parameter, s = 1.5 is the scale parameter of the local criteria, and rC = 0.17 nm is the van der Waals radius of carbon in the AMBER-99SB-ILDN force field.

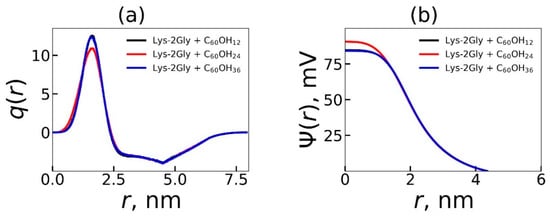

Figure 7.

The electrostatic characteristics—(a) the radial charge distribution, q(r), and (b) the electrostatic potential, ψ(r), of the complexes containing the Lys-2Gly dendrimer and different fullerenols C60(OH)12, C60(OH)24, and C60(OH)36. Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns.

Table 3.

The average electrostatic properties: the maximum cumulative charge (Qmax), potential (ζ), the number of hydrogen bonds in the system (NHb), the number of hydrophobic contacts between the dendrimer and fullerenol (Ncc). Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns. For comparison, the data for the Lys-2Gly and its complex with fullerene C60 studied earlier [105,115] are also provided.

According to Table 3, the electrostatic parameters of all the considered systems are similar. It should be noted that an increase in the number of OH groups on fullerenol reduces the number of hydrophobic contacts by ~1.7 times and increases the number of hydrogen bonds by 3.6 times. The opposite effects of these two factors probably compensate for their individual influence on the size and structure of the complexes.

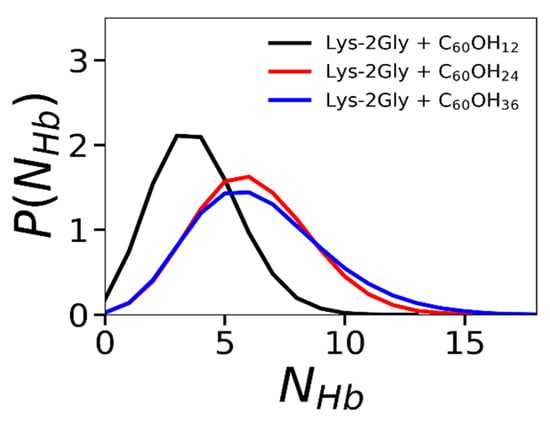

The average number of hydrogen bonds in the complex increases with the number of OH groups on the fullerenol surface (see Table 3). Additionally, we calculated the distribution functions of the number of hydrogen bonds between the dendrimer and fullerenol (C60(OH)12, C60(OH)24 and C60(OH)36) (see Figure 8). We observe that the distribution curves shift toward a higher number of hydrogen bonds with an increase in the hydroxylation degree of the fullerenol, due to an increase in the number of polar OH groups.

Figure 8.

The distribution function of the number of hydrogen bonds between Lys-2Gly dendrimer and three types of fullerenol: C60(OH)12, C60(OH)24, and C60(OH)36. Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns.

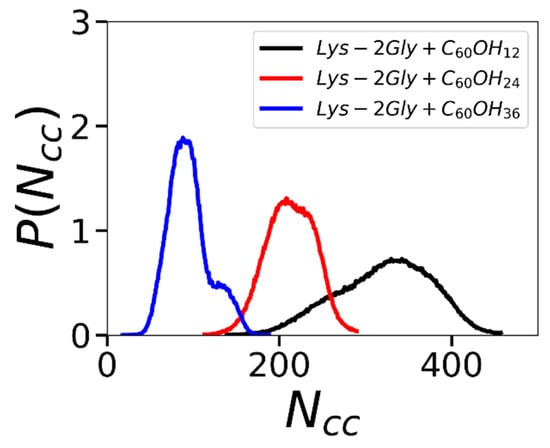

Conversely, the average number of hydrophobic contacts decreases with the increase in the number of OH groups (see Table 3). The distribution functions of the number of hydrophobic contacts between the dendrimer and fullerenols in Figure 9 indicates a clear shift toward a higher number of hydrophobic contacts when the number of OH groups decreases. These findings are consistent with the data presented in Table 3.

Figure 9.

The distribution function of the number of hydrophobic contacts of the Lys-2Gly dendrimer with three types of fullerenols: C60(OH)12, C60(OH)24, and C60(OH)36. Averaging through time interval t = 250–500 ns.

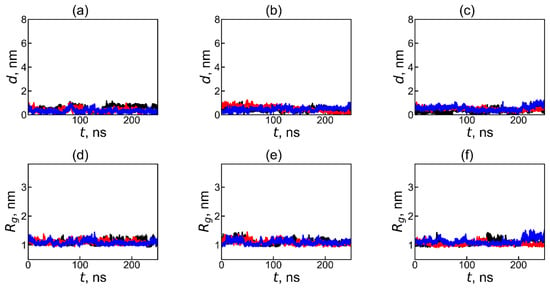

To demonstrate that, after the complex formation, the fullerenol molecule always stay in close contact with dendrimer, we calculated the distance d between the dendrimer center of mass and fullerenol center of mass, as well as size Rg of the complex during the second part of trajectory between 250 ns and 500 ns (i.e., during second MD run which was used for calculation of average characteristics and distribution functions of the dendrimer–fullerenol complex). Comparison of the results in Figure 10 during the second MD run (between 250 ns and 500 ns) and Figure 2 during the first MD run (between 0ns and 250 ns of total 500 ns trajectory) confirms that, during the whole second MD run, the complex is stable and compact.

Figure 10.

The time dependences of the instantaneous value of the distance d between the centers of mass of the dendrimer and fullerenol molecule in the dendrimer–fullerenol systems: (a) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)12, (b) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)24, and (c) Lys-2Gly + C60(OH)36, and (d–f) the time dependences of the sizes (radii of gyration, Rg) for the same systems, respectively, during the last 250 ns of the calculation. The black, red, and blue curves correspond to the initial positions of the fullerenol—“left”, “back”, and “top”—relative to the center of periodic box.

During the second half of the first run (Figure 2) and all of second run (Figure 10), the values and fluctuation of distance d between the center of mass of dendrimer and center of mass of fullerene, as well as fluctuations of size Rg of the subsystem consisting of all atoms of dendrimer and all atoms of fullerene, are very small and consistent with the average value of these parameters in Table 2. Thus, this plot (Figure 10) confirms that this compact complex is stable during the second half of the first run and the whole second run (i.e., during 400 ns of total 500 ns trajectory).

4. Conclusions

In this work, we studied the possibility of encapsulating fullerenols with different numbers of OH groups within amphiphilic peptide dendrimers using atomistic molecular dynamics simulation. The systems contain the same peptide dendrimer with a repeating Lys-2Gly unit and positively charged terminal NH3+ groups as studied earlier [105], but with hydroxylated fullerenes C60(OH)n (n = 12, 24 and 36) instead of fullerene C60 in aqueous solution. It was shown that fullerenol encapsulated near the dendrimer’s center of mass forms stable complexes with it and the dendrimer branches partially hide fullerenol from water. In general, the encapsulation of the considered hydroxylated fullerenes (fullerenols) by the Lys-2Gly dendrimer is very similar to that of fullerene C60 [105]. However, the increase in hydroxylation changes the type of fullerenol interaction with the dendrimer. Increase in the number of polar OH groups on the surface of fullerenol leads to a reduction in the number of hydrophobic contacts and a corresponding increase in the number of hydrogen bonds. Therefore, the fundamental mechanisms that govern the stability of the complex formed between the dendrimer and fullerene derivatives are altered. We conclude that the Lys-2Gly peptide dendrimer could be a suitable nanocontainer for the delivery of not only fullerenes, but also fullerenols with a different number of OH groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V.B., S.E.M., I.M.N. and O.V.S., software, V.V.B., S.E.M., A.Y.V. and O.V.S.; validation, I.M.N., N.N.S. and D.A.M.; formal analysis, V.V.B., S.E.M., A.Y.V. and O.V.S.; investigation V.V.B., S.E.M., A.Y.V. and O.V.S.; resources, D.A.M.; data curation, V.V.B., S.E.M., A.Y.V. and O.V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V.B., S.E.M. and O.V.S.; writing—review and editing I.M.N., N.N.S. and D.A.M.; visualization, V.V.B. and O.V.S.; supervision, I.M.N. and D.A.M.; project administration, D.A.M.; funding acquisition, D.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 23-13-00144). Alexey Y. Vakulyuk acknowledges Saint Petersburg State University for the research project 125022002755-5.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

The simulation was performed using the equipment of the shared research facilities of HPC computing resources at Lomonosov Moscow State University, the Computer Resources Center of Saint Petersburg State University, and the Interdepartmental Supercomputer Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chawla, P.; Chawla, V.; Maheshwari, R.; Saraf, S.A.; Saraf, S.K. Fullerenes: From Carbon to Nanomedicine. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liu, S.; Yin, J.; Wang, H. Interaction of Human Serum Album and C60 Aggregates in Solution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4964–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Brien, S.C.; Curl, R.F.; Smalley, R.E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, V.M.; Srdjenovic, B. Biomedical Application of Fullerenes. In Handbook on Fullerene: Synthesis, Properties and Applications; Verner, R.F., Benvegnu, C., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 199–239. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa, F. [60]Fullerene and Derivatives for Biomedical Applications. In Nanobiomaterials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemzadeh, H.; Mozafari, M. Fullerene-Based Delivery Systems. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, N.; Pressac, M.; Hadchouel, M.; Szwarc, H.; Wilson, S.R.; Moussa, F. [60]Fullerene Is a Powerful Antioxidant in Vivo with No Acute or Subacute Toxicity. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Bag, S.; Chakraborty, D.; Dasgupta, S. Exploring the Inhibitory and Antioxidant Effects of Fullerene and Fullerenol on Ribonuclease A. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 12270–12283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.-F.; Liu, Z.-Q. Attaching a Dipeptide to Fullerene as an Antioxidant Hybrid against DNA Oxidation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, D.Y.; Adams, L.K.; Falkner, J.C.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Antibacterial Activity of Fullerene Water Suspensions: Effects of Preparation Method and Particle Size. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 4360–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrovsky, L.B.; Kiselev, O.I. Fullerenes and Viruses. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2005, 12, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, C.; Feng, L.; Yang, K.; Liu, Z. Functional Nanomaterials for Phototherapies of Cancer. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10869–10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Mao, R.; Liu, Y. Fullerenes for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy: Preparation, Biological and Clinical Perspectives. Curr. Drug Metab. 2012, 13, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.B.; Shenoy, R.U.K.; Kajampady, M.K.; DCruz, C.E.M.; Shirodkar, R.K.; Kumar, L.; Verma, R. Fullerenes for the Treatment of Cancer: An Emerging Tool. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58607–58627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubo, K.; Matsubayashi, K.; Tategaki, H.; Takada, H.; Oshima, T. Facile Synthesis of Highly Water-Soluble Fullerenes More Than Half-Covered by Hydroxyl Groups. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anilkumar, P.; Lu, F.; Cao, L.; Luo, P.G.; Liu, J.-H.; Sahu, S.; Tackett, K.N., II; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.-P. Fullerenes for Applications in Biology and Medicine. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, F.; D’Anna, F.; Giacalone, R.; Gruttadauria, M.; Riela, S.; Noto, R. Cyclodextrin-[60]Fullerene Conjugates: Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Behavior. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 8105–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Yang, J.; Barron, A.R.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A. Endocytic Mechanisms and Toxicity of a Functionalized Fullerene in Human Cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 191, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Haque, S.A.; Yang, S.-T.; Luo, P.G.; Gu, L.; Kitaygorodskiy, A.; Li, H.; Lacher, S.; Sun, Y.-P. Aqueous Compatible Fullerene−Doxorubicin Conjugates. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 17768–17773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Ebrahimi, A.; Li, J.; Cui, Q. Fullerene-Biomolecule Conjugates and Their Biomedicinal Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Batista Da Rocha, C.; Bennick, R.A.; Zhang, J. Water-Soluble Fullerene Monoderivatives for Biomedical Applications. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202300296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Monthioux, M.; Luzzi, D.E. Encapsulated C60 in Carbon Nanotubes. Nature 1998, 396, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.; Peterlik, H.; Pfeiffer, R.; Bernardi, J.; Kuzmany, H. Fullerene Release from the inside of Carbon Nanotubes: A Possible Route toward Drug Delivery. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 445, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Liposome Formulation of Fullerene-Based Molecular Diagnostic and Therapeutic Agents. Pharmaceutics 2013, 5, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Corrales, D.; Fernández Rojas, N.; Solís Vindas, G.; Santamaría Muñoz, M.; Chavarría Rojas, M.; Matarrita Brenes, D.; Rojas Salas, M.F.; Madrigal Redondo, G. Dendrimers and Their Applications. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2022, 12, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, B.; Borowiec, M.; Franiak-Pietryga, I. There and Back Again: A Dendrimer’s Tale. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 2169–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, K.; Kumar, S.; Poonia, N.; Lather, V.; Pandita, D. Dendrimers in Drug Delivery and Targeting: Drug-Dendrimer Interactions and Toxicity Issues. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2014, 6, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.M.; Cullis, P.R. Drug Delivery Systems: Entering the Mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnik, A.; Carcaboso, A.; Chiappetta, D. Polymeric Nanocarriers: New Endeavors for the Optimization of the Technological Aspects of Drugs. Recent Pat. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 1, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyshenko, M.G. Medical Nanotechnology Using Genetic Material and the Need for Precaution in Design and Risk Assessments. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2008, 5, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhoen, S.; Laufer, S.; Restle, T. Recent Developments in Peptide-Based Nucleic Acid Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 1276–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Xu, T. The Effect of Dendrimers on the Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Behaviors of Non-Covalently or Covalently Attached Drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2291–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karande, P.; Trasatti, J.P.; Chandra, D. Novel Approaches for the Delivery of Biologics to the Central Nervous System. In Novel Approaches and Strategies for Biologics, Vaccines and Cancer Therapies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, A.; Alam, M.; Saxena, K. Dendrimers: A Class of Polymers in the Nanotechnology for the Delivery of Active Pharmaceuticals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 2958–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Emanuele, A.; Attwood, D. Dendrimer-Drug Interactions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 2147–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Thomas, C.; Ahsan, F. Dendrimers as a Carrier for Pulmonary Delivery of Enoxaparin, a Low-Molecular Weight Heparin. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, L.; Sharma, A.K.; Gothwal, A.; Khan, M.S.; Khinchi, M.P.; Qayum, A.; Singh, S.K.; Gupta, U. Dendrimer Encapsulated and Conjugated Delivery of Berberine: A Novel Approach Mitigating Toxicity and Improving in Vivo Pharmacokinetics. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 528, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, K.; Lather, V.; Pandita, D. Evaluation of Polyamidoamine Dendrimers as Potential Carriers for Quercetin, a Versatile Flavonoid. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentek, T.; Newenhouse, E.; O’Brien, B.; Chauhan, A. Development of a Topical Resveratrol Formulation for Commercial Applications Using Dendrimer Nanotechnology. Molecules 2017, 22, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconieri, M.; Adamo, M.; Monasterolo, C.; Bergonzi, M.; Coronnello, M.; Bilia, A. New Dendrimer-Based Nanoparticles Enhance Curcumin Solubility. Planta Med. 2016, 83, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, R.; Wang, S.; Mignani, S.; Caminade, A.-M.; Majoral, J.-P.; Shi, X. Doxorubicin-Conjugated PAMAM Dendrimers for PH-Responsive Drug Release and Folic Acid-Targeted Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqbil, R.M.; Heyder, R.S.; Bielski, E.R.; Durymanov, M.; Reineke, J.J.; da Rocha, S.R.P. Dendrimer Conjugation Enhances Tumor Penetration and Efficacy of Doxorubicin in Extracellular Matrix-Expressing 3D Lung Cancer Models. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, H.M.; Zhou, Z.; Najlah, M.; Yusof, S.R.; Abbott, N.J.; D’Emanuele, A. Delivery of Paclitaxel across Cellular Barriers Using a Dendrimer-Based Nanocarrier. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 441, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Tare, M.S.; Mishra, V.; Tripathi, P.K. The Development, Characterization and in Vivo Anti-Ovarian Cancer Activity of Poly(Propylene Imine) (PPI)-Antibody Conjugates Containing Encapsulated Paclitaxel. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Tashiro, K.; Aida, T.; Zheng, J.-Y.; Kinbara, K.; Saigo, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K. Molecular Design of a Novel Dendrimer Porphyrin for Supramolecular Fullerene/Dendrimer Hybridization. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 9182–9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, K.-Y.; Han, K.-J.; Yu, Y.-J.; Park, Y.D. Dendritic Fullerenes (C 60) with Photoresponsive Azobenzene Groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5053–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, Y.; Accorsi, G.; Nierengarten, H.; Rehspringer, J.-L.; Hönerlage, B.; Kopitkovas, G.; Chugreev, A.; Van Dorsselaer, A.; Armaroli, N.; Nierengarten, J.-F. Fullerodendrimers with Peripheral Triethyleneglycol Chains: Synthesis, Mass Spectrometric Characterization, and Photophysical Properties. New J. Chem. 2002, 26, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaguchi, Y.; Sako, Y.; Yanagimoto, Y.; Tsuboi, S.; Motoyoshiya, J.; Aoyama, H.; Wakahara, T.; Akasaka, T. Facile and Reversible Synthesis of an Acidic Water-Soluble Poly(Amidoamine) Fullerodendrimer. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 5777–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaguchi, Y.; Yanagimoto, Y.; Fujima, S.; Tsuboi, S. Photooxygenation of Olefins, Phenol, and Sulfide Using Fullerodendrimer as Catalyst. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 1142–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.W.; Maru, B.S.; Zhang, X.; Mohanty, D.K.; Fahlman, B.D.; Swanson, D.R.; Tomalia, D.A. Preparation of Fullerene-Shell Dendrimer-Core Nanoconjugates. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1171–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Jensen, A.W.; Abdelhady, H.G.; Tomalia, D.A. AFM Analysis of C 60 and a Poly(Amido Amine) Dendrimer-C 60 Nanoconjugate. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007, 7, 1401–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, U.; Cardinali, F.; Nierengarten, J.-F. Supramolecular Chemistry for the Self-Assembly of Fullerene-Rich Dendrimers. New J. Chem. 2007, 31, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanu, D.; Yevlampieva, N.P.; Deschenaux, R. Polar and Electrooptical Properties of [60]Fullerene-Containing Poly(Benzyl Ether) Dendrimers in Solution. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, U.; Nierengarten, J.-F.; Vögtle, F.; Listorti, A.; Monti, F.; Armaroli, N. Fullerene-Rich Dendrimers: Divergent Synthesis and Photophysical Properties. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, U.; Nierengarten, J.-F.; Delavaux-Nicot, B.; Monti, F.; Chiorboli, C.; Armaroli, N. Fullerodendrimers with a Perylenediimide Core. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yun, M.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Wudl, F.; Yang, C. A Synthetic Approach to a Fullerene-Rich Dendron and Its Linear Polymer via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, U.; Vögtle, F.; Nierengarten, J.-F. Synthetic Strategies towards Fullerene-Rich Dendrimer Assemblies. Polymers 2012, 4, 501–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.; Chang, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, S.; Chu, C.; Tsai, Y.; Imae, T. Self-aggregation of Amphiphilic [60]Fullerenyl Focal Point Functionalized PAMAM Dendrons into Pseudodendrimers: DNA Binding Involving Dendriplex Formation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonlanthen, M.; Gonzalez-Ortega, J.; Porcu, P.; Ruiu, A.; Rodríguez-Alba, E.; Cevallos-Vallejo, A.; Rivera, E. Pyrene-Labeled Dendrimers Functionalized with Fullerene C60 or Porphyrin Core as Light Harvesting Antennas. Synth. Met. 2018, 245, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaszewska, A.; Lazniewska, J.; Trzepiński, P.; Marcinkowska, M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Cytotoxicity of Dendrimers. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chis, A.A.; Dobrea, C.; Morgovan, C.; Arseniu, A.M.; Rus, L.L.; Butuca, A.; Juncan, A.M.; Totan, M.; Vonica-Tincu, A.L.; Cormos, G.; et al. Applications and Limitations of Dendrimers in Biomedicine. Molecules 2020, 25, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, D.; Kesharwani, P.; Deshmukh, R.; Mohd Amin, M.C.I.; Gupta, U.; Greish, K.; Iyer, A.K. PEGylated PAMAM Dendrimers: Enhancing Efficacy and Mitigating Toxicity for Effective Anticancer Drug and Gene Delivery. Acta Biomater. 2016, 43, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhatkar, R.B.; Kitchens, K.M.; Swaan, P.W.; Ghandehari, H. Surface Acetylation of Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) Dendrimers Decreases Cytotoxicity While Maintaining Membrane Permeability. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 2054–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.R.; Carvalho, C.R.; Maia, F.R.; Caballero, D.; Kundu, S.C.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Peptide-Modified Dendrimer Nanoparticles for Targeted Therapy of Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Ther. 2019, 2, 1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharwade, R.; More, S.; Warokar, A.; Agrawal, P.; Mahajan, N. Starburst Pamam Dendrimers: Synthetic Approaches, Surface Modifications, and Biomedical Applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6009–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.S.; Gonzaga, R.V.; Silva, J.V.; Savino, D.F.; Prieto, D.; Shikay, J.M.; Silva, R.S.; Paulo, L.H.A.; Ferreira, E.I.; Giarolla, J. Peptide Dendrimers: Drug/Gene Delivery and Other Approaches. Can. J. Chem. 2017, 95, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapra, R.; Verma, R.P.; Maurya, G.P.; Dhawan, S.; Babu, J.; Haridas, V. Designer Peptide and Protein Dendrimers: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 11391–11441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K.; Tam, J.P. Peptide Dendrimers: Applications and Synthesis. Rev. Mol. Biotechnol. 2002, 90, 195–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Sharma, V.K. Dendrimers: A Class of Polymer in the Nanotechnology for Drug Delivery. In Nanomedicine for Drug Delivery and Therapeutics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 373–409. ISBN 9781118414095. [Google Scholar]

- Martinho, N.; Silva, L.C.; Florindo, H.F.; Brocchini, S.; Zloh, M.; Barata, T.S. Rational Design of Novel, Fluorescent, Tagged Glutamic Acid Dendrimers with Different Terminal Groups and in Silico Analysis of Their Properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 7053–7073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.; Bugno, J.; Lee, S.; Hong, S. Dendrimer-based Nanocarriers: A Versatile Platform for Drug Delivery. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9, e1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmerston Mendes, L.; Pan, J.; Torchilin, V. Dendrimers as Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid and Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2017, 22, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheveleva, N.N.; Konarev, P.V.; Boyko, K.M.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Mikhailova, M.E.; Bezrodnyi, V.V.; Shavykin, O.V.; Neelov, I.M.; Markelov, D.A. SAXS, DLS, and MD Studies of the Rg/Rh Ratio for Swollen and Collapsed Dendrimers. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 194901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, T.; Fu, D.; Chang, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jin, L.; Chen, F.; Peng, X. Recent Progress in Dendrimer-Based Gene Delivery Systems. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016, 20, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompilio, A.; Geminiani, C.; Mantini, P.; Siriwardena, T.N.; Di Bonaventura, I.; Reymond, J.L.; Di Bonaventura, G. Peptide Dendrimers as “Lead Compounds” for the Treatment of Chronic Lung Infections by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1767–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Jeddou, F.; Falconnet, L.; Luscher, A.; Siriwardena, T.; Reymond, J.-L.; van Delden, C.; Köhler, T. Adaptive and Mutational Responses to Peptide Dendrimer Antimicrobials in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Jordan, O.; Hanawa, T.; Borchard, G.; Patrulea, V. Are Antimicrobial Peptide Dendrimers an Escape from ESKAPE? Adv. Wound Care 2020, 9, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas-Arranz, R.; de León, P.; Forner, M.; Defaus, S.; Bustos, M.J.; Torres, E.; Andreu, D.; Blanco, E.; Sobrino, F. Immunogenicity of a Dendrimer B2T Peptide Harboring a T-Cell Epitope From FMDV Non-Structural Protein 3D. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhlwatika, Z.; Aderibigbe, B. Application of Dendrimers for the Treatment of Infectious Diseases. Molecules 2018, 23, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandeel, M.; Al-Taher, A.; Park, B.K.; Kwon, H.; Al-Nazawi, M. A Pilot Study of the Antiviral Activity of Anionic and Cationic Polyamidoamine Dendrimers against the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, L.; Sanclimens, G.; Pons, M.; Giralt, E.; Royo, M.; Albericio, F. Peptide and Amide Bond-Containing Dendrimers. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1663–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.M.V.; Crusz, S.A.; Kolomiets, E.; Buts, L.; Kadam, R.U.; Cacciarini, M.; Bartels, K.-M.; Diggle, S.P.; Cámara, M.; Williams, P.; et al. Inhibition and Dispersion of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms by Glycopeptide Dendrimers Targeting the Fucose-Specific Lectin LecB. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorain, B.; Choudhury, H.; Pandey, M.; Mohd Amin, M.C.I.; Singh, B.; Gupta, U.; Kesharwani, P. Dendrimers as Effective Carriers for the Treatment of Brain Tumor. In Nanotechnology-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Brain Tumors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 267–305. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, B.M.; Iegre, J.; O’ Donovan, D.H.; Ölwegård Halvarsson, M.; Spring, D.R. Peptides as a Platform for Targeted Therapeutics for Cancer: Peptide–Drug Conjugates (PDCs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1480–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A.; Vovk, M.A.; Mikhailova, M.E.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Neelov, I.M.; Lähderanta, E. NMR Studies of Excluded Volume Interactions in Peptide Dendrimers. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A.; Vovk, M.A.; Mikhailova, M.E.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Tolstoy, P.M.; Neelov, I.M.; Lähderanta, E. Lysine-Based Dendrimer with Double Arginine Residues. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18018–18026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A.; Vovk, M.A.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Mikhailova, M.E.; Ilyash, M.Y.; Neelov, I.M.; Lahderanta, E. Stable Deuterium Labeling of Histidine-Rich Lysine-Based Dendrimers. Molecules 2019, 24, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheveleva, N.N.; Bezrodnyi, V.V.; Mikhtaniuk, S.E.; Shavykin, O.V.; Neelov, I.M.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Vovk, M.A.; Mikhailova, M.E.; Penkova, A.V.; Markelov, D.A. Local Orientational Mobility of Collapsed Dendrimers. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 11083–11092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrodnyi, V.V.; Mikhtaniuk, S.E.; Shavykin, O.V.; Neelov, I.M.; Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A. Size and Structure of Empty and Filled Nanocontainer Based on Peptide Dendrimer with Histidine Spacers at Different PH. Molecules 2021, 26, 6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Veiga, F.; Figueiras, A. Dendrimers as Pharmaceutical Excipients: Synthesis, Properties, Toxicity and Biomedical Applications. Materials 2019, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzkiewicz, M.; Kopeć, O.; Janaszewska, A.; Konopka, M.; Pędziwiatr-Werbicka, E.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Bezrodnyi, V.V.; Neelov, I.M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Poly(Lysine) Dendrimers Form Complexes with SiRNA and Provide Its Efficient Uptake by Myeloid Cells: Model Studies for Therapeutic Nucleic Acid Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Yu, B.; Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Cong, H.; Shen, Y. The Drug Loading Behavior of PAMAM Dendrimer: Insights from Experimental and Simulation Study. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Rajhi, A.A.; Ali, E.; Chandra, S.; Hassan Ahmed, H.; Hussein Adhab, Z.; Alkhayyat, A.S.; Alsalamy, A.; Saadh, M.J. Acetyl-Terminated PAMAM Dendrimers for PH-Sensitive Delivery of Irinotecan and Fluorouracil: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 832, 140876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, P.; Panczyk, T.; Brzyska, A. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Carbon Quantum Dots/Polyamidoamine Dendrimer Nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 16740–16750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Tian, W.; Chen, K.; Ma, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of G-Actin Interacting with PAMAM Dendrimers. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2018, 84, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojceski, F.; Grasso, G.; Pallante, L.; Danani, A. Molecular and Coarse-Grained Modeling to Characterize and Optimize Dendrimer-Based Nanocarriers for Short Interfering RNA Delivery. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 2978–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trosheva, K.S.; Sorokina, S.A.; Efimova, A.A.; Semenyuk, P.I.; Berkovich, A.K.; Yaroslavov, A.A.; Shifrina, Z.B. Interaction of Multicomponent Anionic Liposomes with Cationic Pyridylphenylene Dendrimer: Does the Complex Behavior Depend on the Liposome Composition? Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberger, H.; Schwab, C.H.; Hirsch, A.; Gasteiger>, J. Molecular Modeling of Fullerene Dendrimers. J. Mol. Model. 2000, 6, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierengarten, J.-F. Dendritic Encapsulation of Active Core Molecules. Comptes Rendus. Chim. 2003, 6, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawski, M.; Rakesh, L.; Gala, K.; Jensen, A.; Fahlman, B.; Feng, Z.; Mohanty, D.K. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Polyamidoamine Dendrimer-Fullerene Conjugates:Generations Zero Through Four. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007, 7, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Kim, S.H.; Chen, P.; Chen, R.; Spuches, A.M.; Brown, J.M.; Lamm, M.H.; Ke, P.C. Dendrimer–Fullerenol Soft-Condensed Nanoassembly. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 15775–15781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Albrecht, K.; Kasai, Y.; Kuramoto, Y.; Yamamoto, K. Dynamic Control of Dendrimer–Fullerene Association by Axial Coordination to the Core. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, K.; Kasai, Y.; Kuramoto, Y.; Yamamoto, K. A Fourth-Generation Carbazole–Phenylazomethine Dendrimer as a Size-Selective Host for Fullerenes. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, J.-F.; Byrne, D.; Nicoud, J.-F.; Oswald, L.; Nierengarten, J.-F.; Numata, M.; Ikeda, A.; Shinkai, S.; Armaroli, N. Polybenzyl Ether Dendrimers for the Complexation of [60]Fullerenes. New J. Chem. 2000, 24, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrodnyi, V.V.; Mikhtaniuk, S.E.; Shavykin, O.V.; Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A.; Neelov, I.M. A Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Complexes of Fullerenes and Lysine-Based Peptide Dendrimers with and without Glycine Spacers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzkiewicz, M.; Konopka, M.; Janaszewska, A.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Sheveleva, N.N.; Gajek, A.; Neelov, I.M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Application of New Lysine-Based Peptide Dendrimers D3K2 and D3G2 for Gene Delivery: Specific Cytotoxicity to Cancer Cells and Transfection in Vitro. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 95, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, A.; Doi, Y.; Nishiguchi, K.; Kitamura, K.; Hashizume, M.; Kikuchi, J.; Yogo, K.; Ogawa, T.; Takeya, T. Induction of Cell Death by Photodynamic Therapy with Water-Soluble Lipid-Membrane-Incorporated [60]Fullerene. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulchitsky, V.A.; Alexandrova, R.; Suziedelis, K.; Paschkevich, S.G.; Potkin, V.I. Perspectives of Fullerenes, Dendrimers, and Heterocyclic Compounds Application in Tumor Treatment. Recent Pat. Nanomed. 2015, 4, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markelov, D.A.; Mazo, M.A.; Balabaev, N.K.; Gotlib, Y.Y. Temperature Dependence of the Structure of a Carbosilane Dendrimer with Terminal Cyanobiphenyl Groups: Molecular-Dynamics Simulation. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2013, 55, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markelov, D.A.; Polotsky, A.A.; Birshtein, T.M. Formation of a “Hollow” Interior in the Fourth-Generation Dendrimer with Attached Oligomeric Terminal Segments. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 14961–14971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Tang, P.; Qiu, F.; Shi, A.C. Density Functional Study for Homodendrimers and Amphiphilic Dendrimers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 5553–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markelov, D.A.; Semisalova, A.S.; Mazo, M.A. Formation of a Hollow Core in Dendrimers in Solvents. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2021, 222, 2100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Piana, S.; Palmo, K.; Maragakis, P.; Klepeis, J.L.; Dror, R.O.; Shaw, D.E. Improved Side-Chain Torsion Potentials for the Amber Ff99SB Protein Force Field. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2010, 78, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhtaniuk, S.; Bezrodnyi, V.; Shavykin, O.; Neelov, I.; Sheveleva, N.; Penkova, A.; Markelov, D. Comparison of Structure and Local Dynamics of Two Peptide Dendrimers with the Same Backbone but with Different Side Groups in Their Spacers. Polymers 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darinskii, A.A.; Gotlib, Y.Y.; Lyulin, A.V.; Neyelov, L.M. Computer Simulation of Local Dynamics of a Polymer Chain in the Orienting Field of the Liquid Crystal Type. Polym. Sci. 1991, 33, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennari, J.; Neelov, I.; Sundholm, F. Simulation of a PEO based solid polyelectrolyte, comparison of the CMM and the Ewald summation method. Polymer 2000, 41, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennari, J.; Neelov, I.; Sundholm, F. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the PEO Sulfonic Acid Anion in Water. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 2000, 10, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelov, I.M.; Binder, K. Brownian Dynamics of Grafted Polymer Chains: Time Dependent Properties. Macromol. Theory Simul. 1995, 4, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelov, I.M.; Adolf, D.B.; McLeish, T.C.B.; Paci, E. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Dextran Extension by Constant Force in Single Molecule AFM. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 3579–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowdy, J.; Batchelor, M.; Neelov, I.; Paci, E. Nonexponential Kinetics of Loop Formation in Proteins and Peptides: A Signature of Rugged Free Energy Landscapes? J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 9518–9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezrodnyi, V.V.; Shavykin, O.V.; Mikhtaniuk, S.E.; Neelov, I.M.; Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A. Why the Orientational Mobility in Arginine and Lysine Spacers of Peptide Dendrimers Designed for Gene Delivery Is Different? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavykin, O.V.; Neelov, I.M.; Darinskii, A.A. Is the Manifestation of the Local Dynamics in the Spin–Lattice NMR Relaxation in Dendrimers Sensitive to Excluded Volume Interactions? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 24307–24317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavykin, O.V.; Mikhailov, I.V.; Darinskii, A.A.; Neelov, I.M.; Leermakers, F.A.M. Effect of an Asymmetry of Branching on Structural Characteristics of Dendrimers Revealed by Brownian Dynamics Simulations. Polymer 2018, 146, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavykin, O.V.; Leermakers, F.A.M.; Neelov, I.M.; Darinskii, A.A. Self-Assembly of Lysine-Based Dendritic Surfactants Modeled by the Self-Consistent Field Approach. Langmuir 2018, 34, 1613–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, I.V.; Darinskii, A.A. Does Symmetry of Branching Affect the Properties of Dendrimers? Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2014, 56, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłos, J.S.; Sommer, J.-U. Properties of Dendrimers with Flexible Spacer-Chains: A Monte Carlo Study. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 4878–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, J.; Gaspari, G. The Aspherity of Random Walks. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1986, 19, L191–L193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, D.N.; Suter, U.W. Shape of Unperturbed Linear Polymers: Polypropylene. Macromolecules 1985, 18, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.P.; Scanlon, M.J.; Krippner, G.Y.; Chalmers, D.K. Molecular Dynamics of Poly(l-Lysine) Dendrimers with Naphthalene Disulfonate Caps. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Theory of Colloid and Interfacial Electric Phenomena; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 12, ISBN 978-0-12-370642-3. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, H.; Khani, M.; Müller-Plathe, F. Gaussian Charge Distributions for Incorporation of Electrostatic Interactions in Dissipative Particle Dynamics: Application to Self-Assembly of Surfactants. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 4197–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A.V.; González-Caballero, F.; Hunter, R.J.; Koopal, L.K.; Lyklema, J. Measurement and Interpretation of Electrokinetic Phenomena (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 77, 1753–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).