Abstract

Parassi mullet (Mugil incilis) is an ecologically and economically important species that supports small-scale artisanal fisheries. However, scarce knowledge of its reproductive biology limits the development of management and conservation strategies. This research describes key milt and sperm characteristics, including milt volume, sperm concentration, motility, and ultrastructural features. Males produced an average of 40.0 ± 20 µL of milt, with sperm concentrations between 6.00 and 20.37 × 109 spermatozoa mL−1. Sperm motility varied between 10% and 80%, with a mean duration of 14.13 ± 4.49 min. Mature spermatozoa measured 33.79 ± 0.67 µm and exhibited a subspherical head without an acrosome, a short midpiece, and a cylindrical flagellum. The nucleus contains electron-dense heterogeneous chromatin. The centriolar complex was positioned outside the nuclear fossa consistent with Type II spermiogenesis. The flagellum comprises a main piece and tapering end piece. The axoneme had 9 + 0 arrangement at the basal body region and the typical 9 + 2 configuration along its length. These results provide the first detailed description of sperm morphology in parassi mullet and contribute to an understanding of its reproductive biology, supporting future applications in taxonomy, toxicology, conservation and aquaculture programs.

1. Introduction

The Mugilidae family comprises 73 species of fish that inhabit coastal marine and brackish waters globally, with some species also found in freshwater environments. These fish, commonly referred to as mugilids or mullets, hold considerable ecological and commercial significance [1,2,3]. Most species are euryhaline, spawning in the sea, and their larvae or juveniles migrate to coastal waters, estuaries, marshes, lagoons, and deltas [2,4]. Recent years have witnessed a notable increase in mullet landings [4] alongside a rise in coastal marine aquaculture activities [5]. Furthermore, due to their crucial role in coastal ecosystems, members of this family have been extensively studied in toxicological research over the past two decades [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Parassi mullet (Mugil incilis) inhabits the coastal waters of the western Atlantic, with sightings reported from Central America to Pernambuco in Brazil [12]. The species serves as a crucial ecological component in the estuaries and coastal lagoons of the Caribbean, functioning as a detritivore and playing a significant role in nutrient recycling and the preservation of water quality. Its function within trophic networks as a food resource for fish and birds, combined with its extensive harvesting by artisanal fisheries, underscores its ecological, economic, and social significance in coastal communities. Along the northern coast of Colombia, this species is caught year-round through artisanal fishing, significantly supporting local fisheries and featuring in traditional cuisine [12,13]. However, information regarding this species, as well as other members of the Mugilidae family, is generally limited, particularly concerning its reproductive biology [14].

Numerous studies have highlighted the significance of milt and sperm quality as critical determinants of reproductive success in both marine and freshwater fish, whether in natural habitats or aquaculture settings [15,16,17,18]. Key parameters that are well-documented include sperm motility, milt pH, sperm concentration, osmolarity, fertility, and the chemical composition of seminal plasma, along with various cellular and molecular functions [19,20,21]. Conversely, the phylogenetic classification of mugilids presents challenges at both the intrafamily and interfamily levels [22]. Nevertheless, examining sperm ultrastructure may provide valuable insights into resolving these phylogenetic issues [23]. In this regard, understanding the reproductive biology of this species is essential for laying the groundwork for future aquaculture initiatives, restocking efforts, and toxicological research. Therefore, the objective of the current study is to present fundamental parameters of milt and sperm, including volume, motility, and sperm concentration in parassi mullet. Additionally, this research offers the first detailed description of the morphology and ultrastructure of the spermatozoa of this species, utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Experimental Protocol

The study was conducted during the reproductive season of this species (from December to February) [14], in the coastal region of Ciénaga, Magdalena, Colombia. A total of 14 wild male specimens (n = 14; total length: 16.78 ± 1.75 cm; average weight: 41.31 ± 9.02 g) were collected by local fishermen. Sex was determined by visual inspection through gentle abdominal massage. Males were identified by the release of milt, while individuals that did not release either milt or eggs were classified as indeterminate. Only males that liberated milt during abdominal massage were included in the evaluations.

These specimens were transported alive in 50 L plastic bags filled with aerated water to the Aquaculture laboratory at the Universidad del Magdalena. The transportation process lasted approximately 40 min. At the laboratory, the fish were weighed, measured and anesthetized with eugenol (1 mL of eugenol: 10 mL of absolute ethanol: 10 L of water) [24]. After cleaning the urogenital area, the semen was extracted by abdominal massage, then collected using 1 mL syringes and immediately transferred to 2 mL sterile vials to record its volume and for storage at 4 °C until the time of analysis.

2.2. Length–Weight Relationship, Relative Condition Factor and Fulton’s Condition Factor

The length–weight relationship (LWR), relative condition factor (Kn), and Fulton’s condition factor (K) were calculated using the available data on total length and body weight. To offer a more comprehensive assessment of fish condition and population dynamics, the formula W = aTLb was utilized to estimate the length–weight relationship. This was achieved through linear regression using logarithmically transformed data. The linear equation Log (W) = log (a) + b log (TL) was employed, resulting in the determination of values for a, which represents the intercept of the relationship, and b, which denotes the slope or growth coefficient.

The condition factor was derived from the formula proposed by [25,26]:

where W = weight (g), and TL = Total length (cm).

The relative condition factor (Kn) was derived using the following formula [27]:

Kn = Wo/Wc, where Wo = Observed weight and Wc = Calculated weight.

2.3. Milt and Sperm Assessment

Macroscopic evaluation encompassed the assessment of color and the viscosity of milt [28]. To determine sperm concentration, the milt was diluted at a ratio of 1:1000 with a fixative solution (Stopmilt R, Patent Registration Number, INAPI: 52193, of the Catholic University of Temuco) that did not activate the sperm, maintaining a pH of 5.0. After 5 min, sperm concentration was quantified using a Neubauer chamber at a magnification of 400× under an optical microscope (Primo Star; Carl Zeiss microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) [29,30]. Sperm motility was assessed subjectively at the same magnification. Briefly, two microliters of milt were combined with 50 μL of filtered seawater, with the pH (7.79). Motility was evaluated immediately following activation by the same observer. The motility score was assigned following the methodology of [31], using a scale from 0 to 4: 0 = immotile spermatozoa; 0.5 = <10% motile sperm, slow swimming; 1 = 10–30% motile sperm, slow swimming; 2 = 30–50% sperm moving, slow swimming; 3 = 50–80% sperm moving, fast swimming; 4 = 80–100% sperm moving, fast swimming. Each measurement was performed in triplicate, and results were reported as the percentage of sperm cells exhibiting movement [32]. The total motility duration was recorded using a stopwatch until 95% of the sperm had stopped moving.

2.4. Sperm Ultrastructure by SEM and TEM

For the assessment of sperm morphology and morphometric characteristics, milt samples (3 µL) were preserved in 2 mL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde, which was prepared in a 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 7.2 for a duration of 2 h. Following this fixation, the samples underwent multiple rinses with the sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 7.2. For SEM analysis, a drop of the fixed sample was applied to coverslips that had been previously treated with 1% polylysine. The samples were then dehydrated through a series of graded ethanol solutions and subjected to critical point drying using a Hitachi HCP-2 apparatus (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The dried specimens were mounted on holders and coated with a 1 nm layer of gold palladium. Observations were conducted using a scanning electron microscope (AURIGA Compact FIB-SEM, Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC., Peabody, MA, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. For TEM analysis, the rinsed samples were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) for 2 h. Subsequently, the samples were stained with a 2% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate for 1 h, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and infiltrated with epoxy resin. Ultra-thin sections (90 nm) were then stained with 2% alcoholic uranyl acetate and lead citrate before being examined in a transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV. Measurements of the SEM and TEM microphotographs were performed using ImageJ 153p bundled with 64-bit Java 8 software (https://imagej.net/Fiji (accessed on 13 February 2024)) [27].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The descriptive statistics for milt characteristics and sperm ultrastructural parameters were analyzed using Statgraphics 19-X64 software. The distribution of each variable was assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For the length–weight relationship, the data were logarithmically transformed (total length and weight) and analyzed using linear regression in Excel. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results

3.1. Length–Weight Relationship, Relative Condition Factor and Fulton’s Condition Factor

The exponential equation of the length–weight relationship demonstrated that there was an 86% variability in weight (R2: 0.86) in relation to length. Furthermore, b = 2.09 indicated a negative allometric growth for parassi mullet, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Length–Weight Relationship, Relative Condition Factor, and Fulton’s Condition Factor (K) of parassi mullet.

3.2. Milt Characteristics

Parassi mullet does not exhibit sexual dimorphism. Male specimens produce low volume of milt, averaging 40.00 ± 20.00 µL, characterized by a white color and high viscosity. The sperm concentration ranged from 6.00 to 20.37 × 109 spermatozoa per mL. The average motility was recorded at 35.86 ± 25.82%, with variability between 10% and 80%. Additionally, the mean duration of motility was 14.13 ± 4.49 min (11.00 to 21.04 min).

3.3. Sperm Ultrastructure

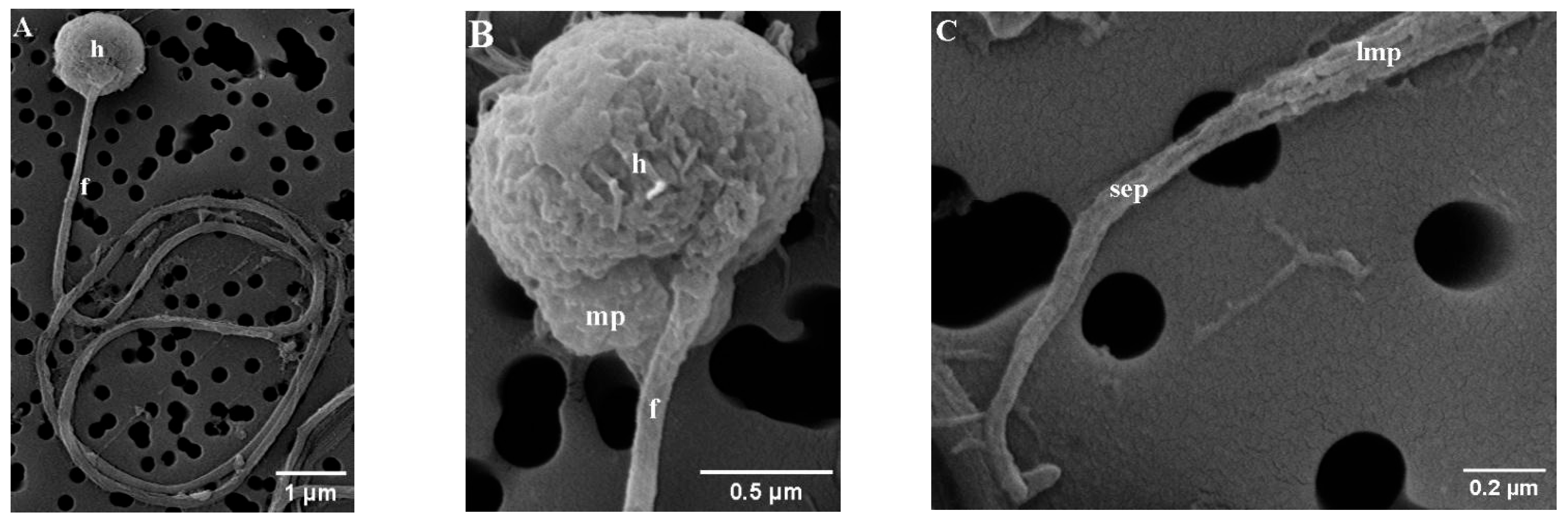

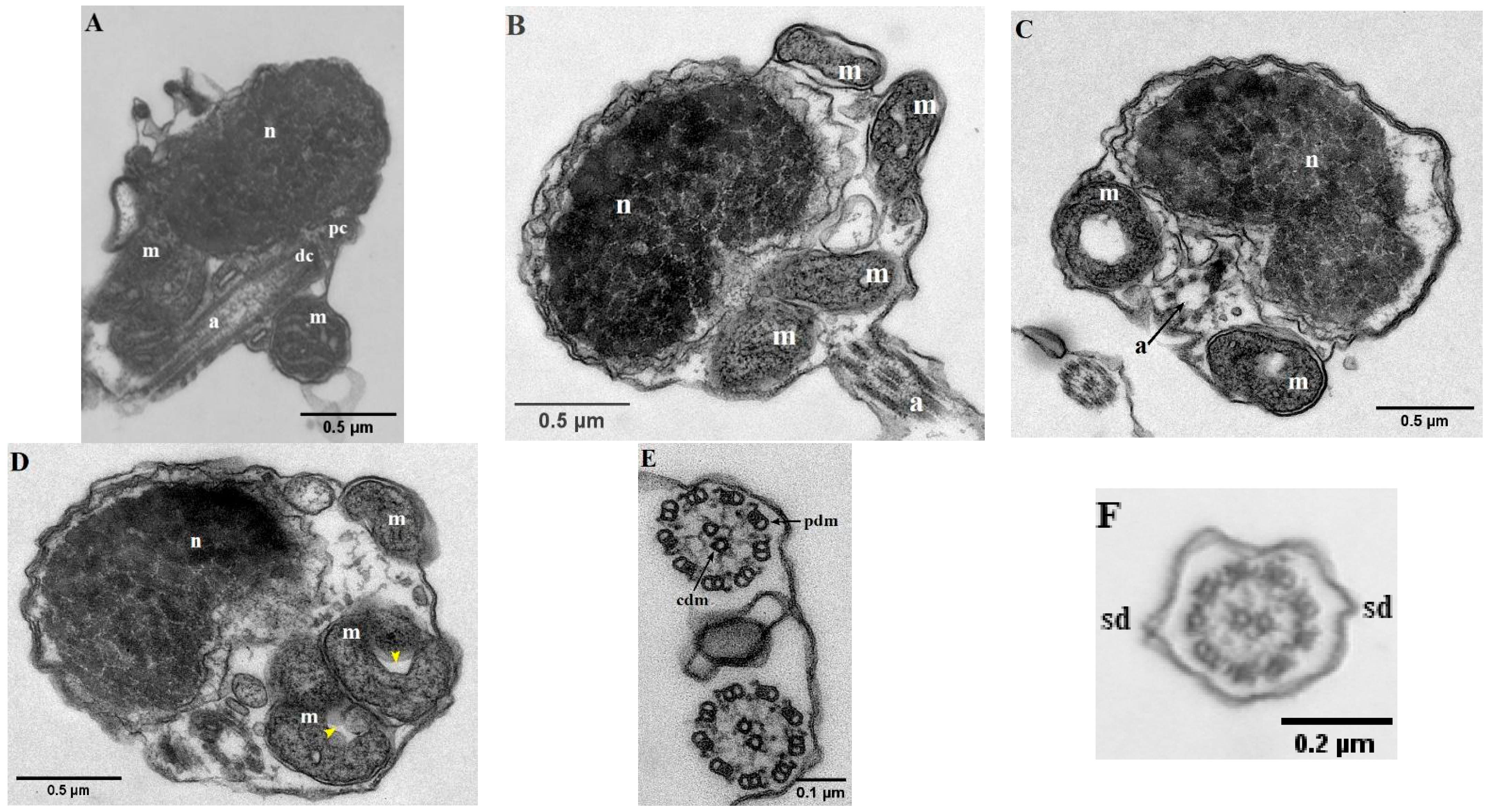

The mature spermatozoa of Parassi mullet exhibit a total length of 33.79 ± 0.67 µm and comprise three distinct sections: the head, a midpiece, and an elongated cylindrical flagellum (Figure 1A–C). SEM images illustrate that the head lacks an acrosome, is subspherical in form, and displays slight asymmetry in its diameters, with the caudal-cranial axis measuring 1.04 ± 0.01 µm and the perpendicular axis measuring 1.28 ± 0.08 µm (Figure 1A,B). TEM images indicate that the head predominantly contains an ovoid, electron-dense nucleus characterized by a heterogeneous texture, which is surrounded by a nuclear membrane (Figure 2A–D).

Figure 1.

Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of parassi mullet sperm, showing: (A) The morphology of the sperm head and main flagellum; (B) Detail of the head (h), midpiece (mp), and flagellum (f); (C) Details of the flagellum, highlighting the posterior region of the long main piece (lmp) and all the short end-piece section (sep).

Figure 2.

Transmission electronic micrographs (TEM) of parassi mullet spermatozoa. (A–D) Longitudinal section of the head showing the nucleus (n), mitochondria (m), proximal centriole (pc), distal centriole (dc) and axoneme (a). (E,F) Cross-section of the axoneme showing the characteristic 9 + 2 pattern of peripheral doublet microtubules (pdm), central doublet microtubules (cdm); and two lateral side-fins (sd). The yellow arrows indicate the ring-shaped mitochondrion.

At the base of the nucleus lies a small nuclear fossa, which is succeeded by the mid-piece, measuring 0.27 ± 0.03 µm along the caudal–cranial axis. This mid-piece contains four mitochondria along with the centriolar complex (Figure 2A,B). In longitudinal sections, the mitochondria appear as rounded structures (with a diameter of 0.46 ± 0.07 µm) and elongated ovoid forms. Each mitochondrion seems to form an independent ring positioned vertically (Figure 2D). These organelles display irregular cristae and an electron-dense matrix, and they are separated from the axoneme by a cytoplasmic canal created by the invagination of the plasma membrane. The centriolar complex is situated outside the nuclear fossa, with the proximal centriole located adjacent to the nucleus and oriented nearly perpendicular to the distal centriole. As a result, both the centriolar complex and the proximal segment of the flagellum are arranged tangentially to the nucleus (Figure 2A). The flagellum has a total length of 32.41 ± 0.60 µm and is characterized as a cylindrical structure that eccentrically traverses the mid-piece (Figure 1B). It is divided into two distinct segments: (i) a long main piece measuring 30.71 ± 0.28 µm and (ii) a short end-piece measuring 1.20 ± 0.01 µm. The main piece maintains a consistent width in both its anterior (0.11 ± 0.00 µm) and posterior (0.12 ± 0.00 µm) regions, while the end-piece is narrower (0.05 ± 0.01 µm). Cross-sectional analyses of the flagellum indicate that the axoneme exhibits a 9 + 0 configuration at the transition from the basal body (Figure 2C), whereas the remainder of the structure displays the typical 9 + 2 configuration, consisting of nine outer doublet microtubules and a single central pair (Figure 2E,F). Additionally, the flagellum features two small lateral extensions or ridges, referred to as side fins (Figure 2F).

4. Discussion

The volume of milt and sperm concentration in male fish species are critical determinants of reproductive success. Our findings indicate that parassi mullet generates a low volume of milt with variable sperm concentrations. The existing scientific literature provides limited information on milt volume in mugilid species. However, the milt volume observed in parassi mullet is similar to that of lebranche mullet (Mugil liza) under captive conditions (45.30 ± 33.40 µL), yet significantly lower than the volumes reported for the same species in the wild, which exceed 2000 µL [18]. Given that the males assessed in this study were wild specimens, it suggests that parassi mullet may be less efficient in milt production compared to other mugilids. Furthermore, it seems that this species produces milt in quantities that are considerably lower—by a factor of 2 to 8—than most fish species [21]. The authors note that both milt volume and sperm concentration can differ not only between species but also among individuals of the same species. In terms of milt volume, it has been reported to range from 0.1 to 356 mL, depending on the species. Only a few species, particularly within the Acipenseridae family, exhibit high milt volumes, while most fish produce less than 1 mL [21]. Notably, coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) is also known to produce a high volume of milt [33].

Conversely, the elevated viscosity noted in the milt samples can be attributed to the high concentration of sperm. This is supported by findings that indicate a reduction in the viscosity of snowtrout (Schizothorax richardsonii), in which milt correlates with lower spermatocrit values [15]. Furthermore, earlier research has established a significant positive relationship between sperm concentration and spermatocrit [15,33,34]. When compared to other teleost species, the sperm concentration of parassi mullet is considered intermediate and is similar to that reported in salmonids.

Motility is one of the main parameters used in the evaluation of gamete quality, which is an essential factor for obtaining viable larvae [35,36]. The motility rate emerged as the most variable parameter in this study. While the peak values align with those documented by Magnotti [18] for lebranche mullet, the average sperm motility observed in parassi mullet is significantly lower. In contrast, the motility duration recorded in this study was twice as long as that of lebranche mullet spermatozoa. The discrepancies among various studies may indicate inter-specific differences. The considerable variability in motility rate may be attributed to (i) individual differences, and (ii) the quality of the activating solution, particularly salinity and pH. These factors are crucial for the activation and regulation of sperm motility, especially in marine and estuarine species [18,37,38]. The spawning locations and reproductive behaviors of this species remain largely unexplored. In this study, seawater was utilized, as optimal motility rates for lebranche mullet spermatozoa were observed within a salinity range of 34.60–34.80 g L−1 and a pH of 8.5–8.7 [18]. However, Pomarico [14] noted that the reproductive period for parassi mullet aligns with a salinity range of 0 to 10 ppm in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (CGSM), which is the principal coastal lagoon in Colombia [39]. This raises the question of whether this species reproduces in the lagoon, which would require further consideration of salinity and pH when selecting or adjusting activation media. Despite using a single activation solution, substantial variation in sperm motility was observed in this study. These differences may reflect the effects of male maturity stage. In contrast, the motility rate and duration for lebranche mullet were influenced by the specific pH and salinity conditions [18]. Consequently, future research should focus on identifying the spawning sites and environmental conditions for parassi mullet, as well as to evaluate the effects of activation media with different salinities on sperm motility.

The length–weight relationship exhibited a negative allometric growth (b = 2.09). While the condition factor (K) serves as an indicator of the nutritional and health status in fish, a value exceeding 1 is regarded as indicative of good body condition [40]. Although a K value greater than 1 typically indicates good body condition, the obtained value (K = 0.87) was low, potentially influenced by factors such as food availability or temperature [41]. Nevertheless, the Kn (1.03) indicates that, in relation to its population, the fish maintain a favorable condition. Overall, the results suggest an adequate physiological state that may be associated with the reproductive phase and characteristic of the species, season, or maturity phase. This allows for the inference that the fish have energy reserves available for growth and reproduction, which may be associated with the characteristic milt production volume of the species (Table 1). This behavior aligns with observations made in other species of Mugilidae [42,43,44], highlighting the necessity to interpret K and Kn complementarily in population and reproductive studies.

Fish spermatozoa can be categorized into two structural types: complex and simple. The simple type, which is predominant among species, is characterized by a spherical or subspherical head, a short midpiece containing one or more mitochondria, and a single flagellum [45]. In contrast, complex spermatozoa, which are less common, possess additional structures such as a pronounced nuclear fossa or an acrosome [46]. The spermatozoa of parassi mullet aligns with the simple classification. Despite the existence of over seven studies examining sperm ultrastructure within this family, data on dimensional parameters remain scarce. The measurements for the flagellum length and total spermatozoa in parassi mullet are comparable to those reported for wild lebranche mullet [18]. Both species exhibit a spherical or subspherical head; however, the head of lebranche mullet is approximately 1 µm larger. These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in methodology, as the previous study utilized images stained with Rose Bengal and employed light microscopy. Additionally, research on grooved mullet (Chelon dumerili) (formerly known as Liza dumerili) indicated that the head and midpiece measured around 2.4 µm in diameter [47], whereas in parassi mullet, these structures were only 1.3 ± 0.03 µm in length.

In teleost fish, the mid-piece of spermatozoa is typically short and contains approximately 4 to 5 mitochondria situated at the base of the nucleus, a feature indicative of a primitive structural type [45]. The findings of the current study support this characterization, suggesting that the spermatozoa of parassi mullet can be classified as primitive. The number of mitochondria in fish spermatozoa can differ across species, even within the same family. In this study, four mitochondrial units were identified. Similarly, in golden gray mullet (Chelon auratus) (formerly known as Liza aurata) four independent spheroidal mitochondria, measuring between 0.55 and 0.66 µm in diameter, were arranged in a ring around the canal [46]. Lebranche mullet is also reported to possess up to four mitochondria [46].

In contrast, white mullet (Mugil curema) has been documented to have between 9 and 10 mitochondria, each approximately 0.59 µm in diameter [48]. A longitudinal section of the anterior region of the spermatozoon of parassi mullet reveals that both the proximal and distal centrioles, collectively referred to as the centriolar complex, are positioned outside the nuclear fossa and are tangential to the nucleus. This arrangement aligns with previous descriptions for grooved mullet, thinlip gray mullet (Chelon ramada), white mullet (Mugil curema), and lebranche mullet [46]. Such organization suggests that the flagellum develops parallel to the nucleus without any nuclear rotation, which is characteristic of type II spermiogenesis [23] and is typical among perciform fishes [49]. This observation is consistent with the historically established close phylogenetic relationships between these two groups; indeed, some studies have classified mullets as perciforms [50]. However, the phylogenetic classification of mugilids remains a topic of ongoing debate [1,51].

Parassi mullet possess a singular flagellum that consists of a main segment and a terminal piece, a characteristic noted in most teleosts. The overall length of this flagellum is similar to that documented for lebranche mullet [18]. Upon examination in cross-section, the flagellum appears cylindrical, with both the anterior and posterior sections of the main segment exhibiting a consistent width, while the terminal piece is narrower, approximately half the width of the main segment. Cross-sectional analysis of the flagellum indicates that the axoneme displays a 9 + 0 configuration at the junction with the basal body, transitioning to a 9 + 2 arrangement throughout the remainder of the flagellum. This finding aligns with earlier studies on other mugilids, including white mullet [48] and thinlip gray mullet [46]. According to Jamieson [46], this axonemal configuration is typical for fish spermatozoa flagella. The primary role of the axoneme, in conjunction with mitochondria, is to facilitate motility [37]. In fish that engage in external fertilization, the straightforward 9 + 2 flagellar structure and the limited presence of mitochondria in the mid-piece are prevalent. Conversely, mammals display a more intricate flagellar structure, characterized by the 9 + 2 axonemal pattern and a greater number of mitochondria in the mid-piece [52,53]. These structural variations are linked to the viscosity of the fertilization environment; sperm in externally fertilizing fish operate in a relatively low-viscosity aquatic medium, while mammalian sperm navigate a more viscous female reproductive tract [47]. Additionally, the flagellum of parassi mullet features a small pair of lateral fins, a structural trait that contrasts with previous findings in other mugilids, which have reported the absence of such fins [47,48,54]. Although these fins may appear quite short, they could serve as a distinguishing feature of this species among other mugilids.

A solid understanding of the basic reproductive biology of a species is essential for detecting alterations caused by external factors, including pollutants. To date, most toxicological studies on mullet species have focused on evaluating the effects of contaminants on enzymatic responses, primarily oxidative stress in organs such as the heart [11], intestine [9], liver, and blood [7,8]. However, evidence from other fish species demonstrates that pollutants can directly impair reproductive parameters. For example, banded knifefish (Gymnotus carapo) exposed to 20 μM cadmium for 24–96 h exhibited reductions in sperm count and morphological alterations [55], while tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exposed to estradiol (E2) showed shortened flagella, decreased motility, and reduced fertilization capacity [56]. In this context, the results of the present study, particularly sperm concentration, motility duration, and morphological traits, provide essential reference points for future reproductive toxicology research in parassi mullet. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to determine whether the observed variability in motility rate reflects natural intraspecies variation or results from methodological constraints associated with the activation conditions used in this study.

5. Conclusions

Parassi mullet generates a low volume of milt with varying sperm concentrations. Significant variability in motility rates was also noted, likely attributable to differences in the maturity stages of the males. Ultrastructural analysis revealed that parassi mullet, similar to other teleosts, displays primitive-type sperm characteristics. Additionally, the positioning of the flagellum in relation to the nucleus suggests that this species, like other members of the mugilid family, undergoes type II spermiogenesis. Future research should aim to explore further reproductive parameters, such as the specific spawning season and locations, a comprehensive evaluation of sperm motility using CASA, investigations into sperm activation solutions, and the establishment of protocols for storage and cryopreservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M., L.S.-V. and A.R.-F.; methodology, K.M., A.R.-F., L.S.-V. and I.V.; formal analysis, K.M., L.S.-V. and A.R.-F.; investigation, K.M., L.S.-V. and A.R.-F.; resources, A.R.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and A.R.-F.; writing—review and editing, K.M., L.S.-V., A.R.-F. and I.V.; supervision, A.R.-F., L.S.-V. and I.V.; project administration, A.R.-F.; funding acquisition, A.R.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the project entitled: Effect of a global warming scenario on the reproduction of fishes of aquaculture interest. 80740-266-2021—AmSud 2020 (MINCIENCIAS). This study was financed by the project entitled: Mugil cephalus production trials under controlled conditions. No 82521 was supported by the Colombian Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (MINCIENCIAS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Magdalena (protocol code Act 003 of 2020 and date of approval 25 November 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the SEM and TEM technical support of the Electron Microscopy Unit, a core facility—Zeiss Reference Center of Universidad Austral de Chile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. Fishes of the World, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trape, S.; Blel, H.; Panfili, J.; Durand, J.D. Identification of tropical Eastern Atlantic Mugilidae species by PCR-RFLP analysis of mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene fragments. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2009, 37, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.M.M.; da Silva, V.E.L.; Assis, I.O.; Fabré, N.N. Interspecific otolith shape and genetic variability as tools for identifying tropical sympatric and congeneric mullet species. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 81, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (FAO)—Blue Transformation in Action; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2024; p. 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (FAO): Towards Blue Transformation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2022; p. 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz de Cerio, O.; Bilbao, E.; Izagirre, U.; Etxebarria, N.; Moreno, G.; Díez, G.; Cajaraville, M.P.; Cancio, I. Toxicology tailored low density oligonucleotide microarray for the thicklip grey mullets (Chelon labrosus): Biomarker gene transcription profile after caging in a polluted harbour. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 140, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Moradas-Ferreira, P.; Reis-Henriques, M.A. Oxidative stress biomarkers in two resident species, mullet (Mugil cephalus) and flounder (Platichthys flesus), from a polluted site in River Douro Estuary, Portugal. Aquat. Toxicol. 2005, 71, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, L.; Niu, C. Immune defense parameters of wild fish as sensitive biomarkers for ecological risk assessment in shallow sea ecosystems: A case study with wild mullet (Liza haematocheila) in Liaodong Bay. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 194, 10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marijić, V.F.; Raspor, B. Metallothionein in intestine of red mullet, Mullus barbatus as a biomarker of copper exposure in the coastal marine areas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 54, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.; Barboza, L.G.; Vieira, L.R.; Botelho, M.J.; Vale, C.; Guilhermino, L. Relations between microplastic contamination and stress biomarkers under two seasonal conditions in wild carps, mullets and flounders. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 204, 06925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinkovitch, T.; Imbert, N.; Sanchez, W.; Le Floch, S.; Thomas-Guyon, H. Toxicological effects of crude oil and oil dispersant: Biomarkers in the heart of the juvenile golden grey mullet (Liza aurata). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 88, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, M.; Dantas, D.V. Biogeography and Distribution of Mugilidae in the Americas. In Biology, Ecology and Culture of Grey Mullet (Mugilidae), 1st ed.; Crossetti, D., Blaber, S.J.M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Galván-Borja, D.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Barrios-García, L. Occurrence of Ascocotyle (Phagicola) longa Ransom, 1920 (Digenea: Heterophyidae) in Mugil incilis from Cartagena Bay, Colombia. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 168, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomárico, J.L. Indicadores Reproductivos de la Lisa Mugil incilis (Hancock, 1830) en la Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Colombia. Master’s Thesis, Universidad del Magdalena, Santa Marta, Colombia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, N.K.; Raghuvanshi, S.K. Spermatocrit and sperm density in snowtrout (Schizothorax richardsonii): Correlation and variation during the breeding season. Aquaculture 2009, 291, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, J.; Egeland, T.B.; Purchase, C.F.; Nordeide, J.T. Fish sperm competition in hatcheries and between wild and hatchery origin fish in nature. Theriogenology 2019, 133, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatello, L.; Bertotto, D.; Cerri, R.; Parmeggiani, A.; Govoni, N.; Trocino, A.; Xiccato, G.; Mordenti, O. Sperm quality in wild-caught and farmed males of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 198, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnotti, C.; Figueroa, E.; Farias, J.G.; Merino, O.; Valdebenito, I.; Oliveira, R.P.S.; Cerqueira, V. Sperm characteristics of wild and captive lebranche mullet Mugil liza (Valenciennes, 1836), subjected to sperm activation in different pH and salinity conditions. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 192, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effer, B.; Figueroa, E.; Augsburger, A.; Valdebenito, I. Sperm biology of Merluccius australis: Sperm structure, semen characteristics and effects of pH, temperature and osmolality on sperm motility. Aquaculture 2013, 408, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, E.; Valdebenito, I.; Farias, J.G. Technologies used in the study of sperm function in cryopreserved fish spermatozoa. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.K.; Cejko, B.I. Sperm quality in fish: Determinants and affecting factors. Theriogenology 2019, 135, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.M.D.M.; Perez, A.; Fabré, N.N.; Pereira, R.J.; Mott, T. Integrative taxonomy reveals extreme morphological conservatism in sympatric Mugil species from the Tropical Southwestern Atlantic. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2021, 59, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagio-Grassiotto, I.; Baicere-Silva, C.M.; Oliveira Santana, J.C.; Mirande, J.M. Spermiogenesis and sperm ultrastructure as sources of phylogenetic characters. The example of characid fishes (Teleostei: Characiformes). Zool. Anz. 2020, 289, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, T.M.; Almeida-Monteiro, P.S.; de Nascimento, R.V.; do Cândido-Sobrinho, S.A.; Sousa, C.T.N.; Ferreira, Y.M.; de Paula, K.T.; Salmito-Vanderley, C.S.B. Effects of taurine, cysteine and melatonin as antioxidant supplements to the freezing medium of Prochilodus brevis sperm. Cryobiology 2024, 114, 104858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, R. Cube law, condition factor and weight–length relationships: History, meta-analysis and recommendations. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 22, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeogun, A.O.; Ibor, O.R.; Onoja, A.B.; Arukwe, A. Fish condition factor, peroxisome proliferator activated receptors and biotransformation responses in Sarotherodon melanotheron from a contaminated freshwater dam (Awba Dam) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 121, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cren, E.D. The length-weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in the perch (Perca fluviatilis). J. Anim. Ecol. 1951, 20, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifiantini, R.I. Semen Collection and Evaluation Techniques in Animals; IPB Press: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Casallas, P.; Velasco Santamaría, Y.; Medina Robles, V. Determinación del espermatocrito y efecto del volumen de la dosis seminante sobre la fertilidad en yamú (Brycon amazonicus). Rev. Colomb. Ciencias Pecu. 2006, 19, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; International Council for Standardization in Haematology. Recommended Methods for the Visual Determination of White Blood Cell Count and Platelet Count (No. WHO/DIL/00.3); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan, R.; Munuswamy, N. Cryopreservation of sperm in Grey mullet Mugil cephalus (Linnaeus, 1758). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 185, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Robles, V.M.; Sandoval-Vargas, L.Y.; Suárez-Martínez, R.O.; Gómez-Ramírez, E.; Guaje-Ramírez, D.N.; Cruz-Casallas, P.E. Cryostorage of white cachama (Piaractus orinoquensis) sperm: Effects on cellular, biochemical and ultrastructural parameters. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 29, 101477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Vargas, L.; Risopatrón, J.; Dumorne, K.; Farías, J.; Figueroa, E.; Valdebenito, I. Spermatology and sperm ultrastructure in farmed coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvedt, H.B.; Benfey, T.J.; Martin-Robichaud, D.J.; Power, J. The relationship between sperm density, spermatocrit, sperm motility and fertilization success in Atlantic halibut, Hippoglossus hippoglossus. Aquaculture 2001, 194, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurangwa, E.; Kime, D.E.; Ollevier, F.; Nash, J.P. The measurement of sperm motility and factors affecting sperm quality in cultured fish. Aquaculture 2004, 234, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, V.; Asturiano, J.F. Sperm motility in fish: Technical applications and perspectives through CASA-Mot systems. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2018, 30, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.M.H.; Cosson, J.; Bondarenko, O.; Linhart, O. Sperm motility in fishes: (III) diversity of regulatory signals from membrane to the axoneme. Theriogenology 2019, 136, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, R.; Cosson, M.P. Some problems related to the assessment of sperm motility in freshwater fish. J. Exp. Zool. 1992, 261, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.; Pineda, J.; Trujillo, L.; Rueda, M.; Ibarra-Gutiérrez, K. Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta: The Largest Lagoon-Delta Ecosystem in the Colombian Caribbean. In The Wetland Book; Finlayson, C., Milton, G., Prentice, R., Davidson, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauden, H.N.; Lyu, S.; Alfatat, A.; Mwemi, H.M.; Alam, J.F.; Chen, N.; Wang, X. Population dynamics and seasonal variation in biological characteristics of black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) in Zhanjiang coastal waters, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1515753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Shelton, P.A.; Rideout, R.M. Varying components of productivity and their impact on fishing mortality reference points for Grand Bank Atlantic cod and American plaice. Fish. Res. 2014, 155, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guino-o, R.S. Length-weight and length-length relationships and Fulton condition factor of Philippine mullets (Family Mugilidae: Teleostei). Silliman J. 2012, 53, 176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Cruz, L.; Quiñonez-Velázquez, C.; García-Domínguez, F.A.; Pérez-Quiñonez, C.I.; Aguilar-Camacho, V. Aspectos reproductivos de Mugil curema (Perciformes: Mugilidae) en dos zonas de Baja California Sur, México. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2021, 56, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, R.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, A.; Ganesan, K.; Thangappan, A.K.T.; Lal, K.K.; Mohindra, V. Evaluating the influence of environmental variables on the length-weight relationship and prediction modelling in flathead grey mullet, Mugil cephalus Linnaeus, 1758. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, A.S. Fertilization in Fishes and the Problem of Polyspermy; Translated from Russian by Israel Program for Scientific Translations; Israel Program for Scientific Translations: Jerusalem, Israel, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, B. Ultrastructure of Spermatozoa: Acanthopterygii: Mugilomorpha and Atherinomorpha. In Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Fishes (Agnathans and Bony Fishes); Jamieson, B., Ed.; Science Publishers: Enfield, NH, USA, 2009; Volume 8A, pp. 447–502. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Horst, G.; Cross, R.H.M. The Structure of the Spermatozoon of Liza Dumerili (Teleostei) With Notes on Spermiogenesis. Zool. Afr. 1978, 13, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eiras-Stofella, D.R.; Gremski, W.; Kuligowski, S.M. The ultrastructure of the mullet Mugil curema Valenciennes (Teleostei, Mugilidae) spermatozoa. Rev. Bras. Zool. 1993, 10, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, R.J.; Smith, C. Reproductive Biology of Teleost Fishes, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, N.A.; Nirchio, M.; De Oliveira, C.; Siccharamirez, R. Taxonomic review of the species of Mugil (Teleostei: Perciformes: Mugilidae) from the Atlantic South Caribbean and South America, with integration of morphological, cytogenetic and molecular data. Zootaxa 2015, 3918, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dettaï, A.; Cruaud, C.; Couloux, A.; Desoutter-Meniger, M.; Lecointre, G. RNF213, a new nuclear marker for acanthomorph phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2009, 50, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirashima, T.; Sound, W.P.; Hirashima, T.; Noda, T.; Noda, T. Collective sperm movement in mammalian reproductive tracts. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 166, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertika, S.; Singh, K.K.; Rajender, S. Mitochondria, spermatogenesis, and male infertility—An update. Mitochondrion 2020, 54, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruslé, S. Ultrastructure of spermiogenesis in Liza aurata Risso, 1810 (Teleostei, Mugilidae). Cell Tissue Res. 1981, 217, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergilio, C.S.; Moreira, R.V.; Carvalho, C.E.V.; Melo, E.J.T. Tissue and Cell Evolution of cadmium effects in the testis and sperm of the tropical fish Gymnotus carapo. Tissue Cell 2015, 47, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Bai, F.; Gao, T.; Chen, Y.; Wu, F.; Xie, X.; Wang, D.; Sun, L. Prepubertal exposure to 17 β-estradiol downregulates motor protein genes, impairs sperm flagella formation, and reduces fertility in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 285, 107422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.