Abstract

This study analyzes the functioning and sustainability of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium spp.) value chain in the Mangroves Marine Park, Democratic Republic of Congo, using the VCA4D methodology, which integrates economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Data were collected through in-depth interviews, direct observations, and documentary review. The value chain, vital for local communities, also supplies urban markets in Boma, Muanda, Matadi, and Kinshasa. It involves five main actor groups: fishers, middlemen, retailers, restaurateurs, and consumers. High informality, fishers’ dependence on downstream actors, and the lack of traceability and sanitary control compromise overall efficiency and food safety. Value added is predominantly captured by urban retailers, particularly in Kinshasa. Socially and environmentally, the chain exhibits major vulnerabilities, including precarious livelihoods, low female inclusion, limited access to services, and anthropogenic pressures on ecosystems. The study therefore recommends, among other measures, establishing a sustainable management framework, including the protection of breeding areas and regulation of fishing effort, and strengthening actor capacities through improved preservation infrastructure and promotion of transparent pricing mechanisms. These measures aim to enhance the equity, resilience, and sustainability of this critical fishery resource.

1. Introduction

Fishery represents a critical sector with the potential to contribute substantially and sustainably to food and nutritional security in developing countries. In Africa, the fishery sector supplies approximately 22% of the animal protein consumed, sourced from both freshwater and marine ecosystems [1]. Situated astride the equator, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) boasts an extensive hydrographic network, with inland waters covering approximately 3.5% of the national territory [2] and accounting for nearly 52% of Africa’s freshwater resources [3]. This considerable hydrological endowment positions the DRC strategically for the sustainable development of fisheries and aquaculture across the continent.

The aquatic fauna of the DRC comprises both vertebrate and invertebrate species. The latter, estimated at 1596 species, include 1423 freshwater and 183 marine species [4]. Among aquatic invertebrates, crustaceans and mollusks play a pivotal role, providing resources for human consumption and supporting fish populations. Beyond their economic importance, these organisms perform essential ecological functions, including the decomposition of organic matter and the release of nutrients that sustain the growth of aquatic plants [5].

Within this group, giant freshwater prawns of the genus Macrobrachium rank among the most heavily exploited species. Globally recognized as high-value fishery products, they are highly sought after in both local and international markets [6]. In the DRC, shrimp fishing represents a long-standing traditional practice deeply embedded in rural communities. It is particularly intensive in the river Congo estuary, within the Mangroves Marine Park (MMP) [7,8]. Within this protected area, Macrobrachium spp. constitute an increasingly important fishery resource, both economically and socially.

However, the value chain remains characterized by rudimentary practices, socioeconomic vulnerability among stakeholders, escalating pressure on the resource and associated ecosystems, and insufficient integrated governance [8]. These challenges raise a critical question: how can the economic valorization of the Macrobrachium spp. value chain be reconciled with the preservation of socio-environmental balance within the MMP?

This study addresses this question by assessing the social, economic, and environmental sustainability of the Macrobrachium spp. value chain. Specifically, it aims to (i) examine the functioning of the Macrobrachium spp. value chain; (ii) identify the social and economic issues associated with the exploitation of this resource; (iii) evaluate the environmental impacts of capture, processing, and marketing practices; and (iv) identify constraints and opportunities that may influence the chain’s sustainability, with a view to formulating strategic recommendations for a more equitable, resilient, and integrated management of the sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

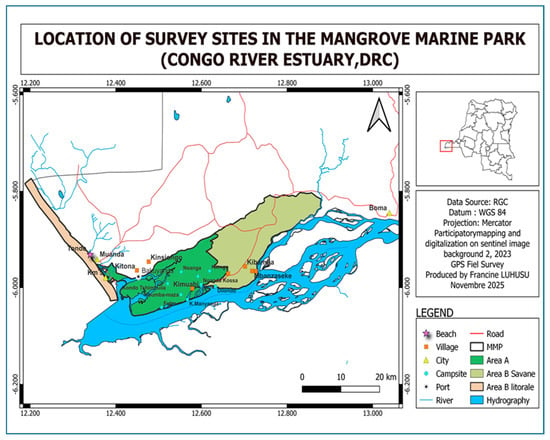

The study was carried out in Zones A and B of the MMP (Figure 1), a Ramsar-designated site located at the estuary of the river Congo, within the Muanda Territory of Kongo-Central Province, DRC. Zone A (19,685 ha) comprises mangrove ecosystems under strict protection, whereas Zone B (43,476 ha) includes humid savanna areas subject to partial protection.

Figure 1.

Location of the Study Sites within the MMP.

The park covers a total area of 768 km2, approximately 20% of which is composed of marine environments. It is geographically positioned between 5°45′ and 6°55′ South latitude and 12°45′ and 13°00′ East longitude, at altitudes below 500 m. The region experiences a humid tropical climate (Köppen AW4), with mean annual temperatures ranging from 22 °C to 24 °C. Its hydrographic network is influenced by both marine and fluvial waters, particularly in the stretch between Boma and Banana.

2.2. Data Collection

This study was designed to encompass the entire Macrobrachium spp. marketing chain, targeting all actors operating at various levels, including fishermen and fish traders in island villages and camps, as well as retailers and restaurateurs in the cities of Muanda, Boma, and Kinshasa. This approach ensured comprehensive coverage of the commercial circuit and provided a holistic understanding of practices and interactions across the value chain.

Data collection was conducted over a 90-day period, from June to August 2024, to capture representative practices and activities throughout this timeframe. A purposive sampling strategy was employed, yielding a sample of 67 fishermen (33 in Zone A and 34 in Zone B), supplemented by in-depth interviews with other key actors in the value chain: fish traders (n = 6), retailers (n = 10), restaurateurs (n = 5), and consumers (n = 14).

Purposive sampling was used due to the absence of a comprehensive sampling frame of fishers. It allowed for the selection of respondents with in-depth knowledge of Macrobrachium spp. fisheries and representative of the different activity zones, taking into account their experience, availability, and involvement in the value chain. The sample size was determined based on information saturation, meaning that responses began to repeat without providing new relevant data.

Prior to the survey, the questionnaires and interview guides were pretested to assess the relevance of the questions, evaluate respondents’ understanding, and make necessary adjustments to ensure the reliability of the data collected.

Data were collected using structured questionnaires, in accordance with the Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D) methodology, as developed by the European Commission (INTPA F3) and the European Alliance for Agricultural Knowledge for Development (AGRINATURA). Variables examined included socio-demographic characteristics, value chain organization, operational costs, and stakeholder perceptions and expectations regarding sustainability. An enumerator, recruited from among the fish traders, was responsible for recording daily shrimp catches in Zones A and B of the MMP over a one-year period, from September 2023 to August 2024.

2.3. Data Analysis

The analysis adopted a functional approach comprising four components: stakeholder mapping, product typology, trends in catches and prices, and governance mechanisms. Species identification was based on morphological criteria selected from the FAO species identification guide for marine species of the central eastern Atlantic, Volume 1: Crustaceans [9].

The economic assessment combined accounting analysis (value added and net operating profit) with Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) using the Win4Deap 2.1 software. The model was output-oriented and applied under the assumptions of both constant returns to scale and variable returns to scale [10,11]. If the CRS and VRS scores are equal to 1, the production unit is efficient because it uses its resources optimally to generate maximum net income. These actors thus constitute the efficiency frontier and can serve as a benchmark for other units. If CRS and VRS < 1, the production unit is underutilizing or wasting its resources, possibly due to an organization that is unsuited to the current size of their operation. Prices were converted into constant values to account for inflationary effects.

The social assessment used the “Social Profile” tool (VCA4D), based on a four-level rating scale, to assess the degree of social performance of the actors: 1 = Not at all, 2 = Moderate or low, 3 = Significant, and 4 = High. These indicators were applied to questions divided into six key areas: working conditions, land rights and access to water, gender equality, food and nutritional security, social capital, and living conditions. All questions were adapted to the local context and the categories of actors concerned.

Finally, the environmental assessment was conducted to identify the critical pressures exerted on ecosystems by the various links in the value chain.

Data were processed using Excel 2013. Analysis of catch and price trends in Zones A and B, as well as graph generation, was performed using R. Temporal trends in the time series were characterized using the non-parametric Mann–Kendall test (Kendall and tidyverse packages). Study site mapping was conducted in QGIS 10.8, and stakeholder mapping was carried out using Microsoft Office 2013.

3. Results

3.1. Functioning of the Macrobrachium spp. Value Chain in the PMM

3.1.1. Stakeholder Mapping and Commercial Channels

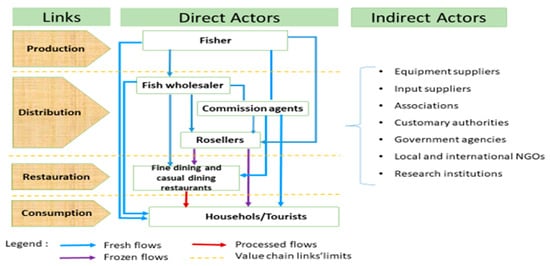

Figure 2 presents a map of the main stakeholders in the Macrobrachium spp. value chain, highlighting product flows at each stage and their respective commercial channels.

Figure 2.

Value chain mapping of Macrobrachium spp. in the MMP.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the value chain is structured around four main stages: production, distribution, processing, and consumption, supported by various indirect stakeholders.

Production

Production occurs within the MMP in the river Congo estuary and is based on artisanal fishing, primarily practiced by men from the Kongo (70%) and Solongo (23%) ethnic groups. The average age of fishers is 38 years. This activity, essential for local subsistence, is deeply rooted in tradition. Some fishers also act as fish traders by purchasing shrimp from others to supplement their stock and meet demand.

Distribution

Distribution involves several categories of stakeholders:

- Fish traders: Locally known as cooperants, they are central actors, well-established in fishing areas. They purchase from fishermen, transport, and store the prawn on ice in basic coolers. They deliver the product to the ports of Muanda and Boma.

- Resellers: Primarily fishmongers established in electrified areas (Moanda and Boma), they possess refrigeration equipment allowing them to maintain the prawn in good condition. They handle both wholesale and retail sales, while also facilitating distribution to more distant urban markets (Matadi and Kinshasa).

- Commission Agents: Intermediaries tasked with selling on behalf of fishermen or fish traders, often in cities, in exchange for a margin.

Processing

The culinary processing of Macrobrachium spp. prawns takes place within various types of establishments located in the main urban centers (Muanda, Boma, Matadi, Kinshasa). Three main segments are distinguished: (i) upscale restaurants, targeting a wealthy clientele with elaborate dishes in a refined setting; (ii) popular restaurants, often managed by women, which ensure wide accessibility through affordable offerings in markets and public spaces, notably on Tonde Beach; and (iii) street vending, particularly prevalent in Kinshasa, where prawn are sold as skewers, making the product available to low-income households.

Consumption

Consumption is concentrated among urban households in the cities of Muanda, Boma, Matadi, and Kinshasa, as well as among tourists, primarily during festive events. In rural areas, consumption remains marginal, as households prefer more affordable local products such as fish and clams.

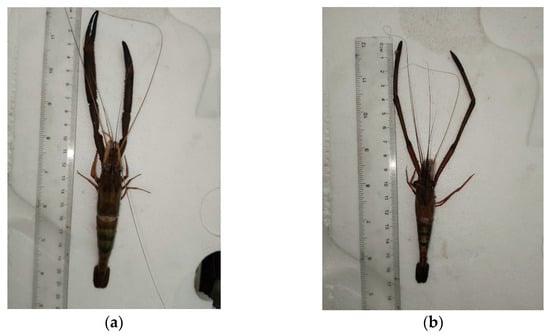

3.1.2. Macrobrachium spp. Species Targeted by the Value Chain

The studied value chain primarily concerns two species of giant freshwater prawns: Macrobrachium vollenhovenii (Herklots, 1857) (Figure 3a) and M. macrobrachion (Herklots, 1851) (Figure 3b). In the local “Solongo” or “Kongo” languages, they are named “Kosa Nzadi” and “Kosa Mpadunga” respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) M. vollenhovenii; (b) M. macrobrachion.

The two species exhibit distinct morphological characteristics:

- M. vollenhovenii has a robust second pair of pereiopods with large blue chelae. Its rostrum is short and does not exceed the antennal scale.

- M. macrobrachion possesses a second pair of pereiopods that are slender and long, lacking chelae but with velvety tips. Its rostrum is longer than the antennal scale and curves upwards.

Unlike marine shrimp of the Penaeidae family, Macrobrachium prawns live primarily in freshwater as adults but require brackish water during their larval stage.

Within the MMP, the two species are generally caught together using traditional baited traps, with palm nuts or dead crabs used as bait. According to the fishers, M. vollenhovenii constitutes the majority of the catch by volume. During sale, these species are mixed and sold fresh. However, they can also be frozen or transformed into prepared dishes by retailers and restaurateurs.

It is important to note that fresh shrimp are often sold by advance order, with prices negotiated beforehand. While this practice ensures a degree of stability in transactions, it may also increase the economic dependence of small-scale producers on their regular buyers.

3.1.3. Temporal Trends in Catches and Prices of Macrobrachium spp. from September 2023 to August 2024

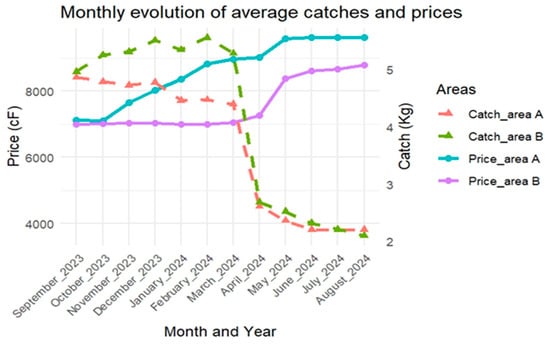

Figure 4 illustrates the monthly trends in average catches and sale prices for Macrobrachium spp. in Zones A and B of the MMP.

Figure 4.

Monthly trends in average catches and prices of Macrobrachium spp. in Zones A and B of the MMP, from September 2023 to August 2024 (Source: field data, 2024).

The monthly analysis of average catches and sale prices (Figure 4) reveals a classic inverse relationship between supply and demand. From September 2023 to March 2024, catches remained high and stable, between 4.5 and 5.5 kg, likely due to the rainy season which favors the reproduction and availability of Macrobrachium prawns in the Congo estuary. During this period, prices in Zone B were stable at around 7000 cf/kg (2.50 USD/kg), while in Zone A, they increased progressively from 7000 to nearly 9000 cf/kg (3.20 USD/kg), attributable to better access to urban markets, notably the tourist city of Muanda.

From April 2024 onwards, a sharp decline in catches was observed in both zones, falling from approximately 5 kg to 2.5 kg per fisher, likely linked to the onset of the dry season, which brings less favorable conditions and increased fishing pressure. Despite this, prices increased markedly, reaching nearly 9000 cf/kg in Zone B and stabilizing around 9500 cf/kg (3.4 USD/kg) in Zone A.

The Mann–Kendall statistical test applied to catch and price data in Zones A and B confirms these trends. Catches decreased significantly in both zones, with a more pronounced decline in Zone A (Tau = −0.9150; p < 0.0001; slope = −0.27 kg/month) than in Zone B (Tau = −0.5152; p = 0.0210; slope = −0.28 kg/month). Concurrently, monthly average prices followed a marked upward trend, particularly in Zone A (Tau = 0.9460; p < 0.0001; slope = 268 cf/kg/month) and to a lesser extent in Zone B (Tau = 0.7816; p = 0.0007; slope = 164 fc/kg/month).

3.1.4. Governance of the Macrobrachium spp. Value Chain

Governance of the value chain within the MMP remains largely informal:

- Absence of written contracts: Relationships between fishermen and fish traders are based on verbal agreements, often grounded in social ties. This system fosters dependence on fishermen on traders, particularly through cash advances;

- Weak collective organization: Few actors are organized into groups. The association of prawn fishermen of Fubu in Kimuabi (APECREFUKI/ASBL), with only 22 members, remains poorly representative. The lack of formal structures for retailers and restaurateurs limits their representation capacity and advocacy;

- Lack of sanitary controls: Trade occurs without clear hygiene or environmental standards, in the absence of effective regulatory oversight;

- Distrust related to weighing scales: In Boma, discrepancies between the electronic and mechanical scales used by fish traders and retailers, respectively, fuel mistrust and result in economic losses.

3.2. Financial and Economic Sustainability

3.2.1. Financial Viability of Stakeholders

The financial viability of the different stakeholders is presented and analyzed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Annual individual operating account for the Macrobrachium spp. value chain (in USD).

Table 1 highlights financial disparities among stakeholders across the different zones. The fishing activity proves to be particularly profitable, especially in Zone B, where a higher Value Added (VA) of 2513 USD and lower variable costs (529 USD) enable an annual Net Operating Income (NOI) of 2349 USD, compared to 1751 USD in Zone A.

Fish traders exhibit a low Value Added, with 85 USD in Zone A and 283 USD in Zone B, and a limited Net Operating Income, underscoring their vulnerability. Urban resellers, particularly those in Kinshasa, record the best performance (VA: 20,358 USD; NOI: 19,712 USD), attributable to their access to and control over lucrative market outlets. In comparison, the profitability of retailers in Boma and Muanda remains moderate, while popular restaurants, especially those on the beach, operate on a very thin margin (NOI: 294 USD) due to high intermediate consumption costs.

3.2.2. Technical Efficiency of Stakeholders

The DEA of the giant shrimp value chain (Table 2) reveals a mean technical efficiency score of 0.723 under VRS and 0.594 under CRS for all stakeholders, with values ranging from 0.073 to 1.00.

Table 2.

Technical efficiency of stakeholders in the Macrobrachium spp. value chain.

Fishermen and fish traders in Zone B, as well as the resellers based in Kinshasa, demonstrate optimal efficiency, with both their Constant Returns to Scale (CRS) and Variable Returns to Scale (VRS) scores equal to 1. This indicates that they utilize their resources effectively and can serve as benchmarks.

Fish traders in Zone A and the resellers in Boma and Muanda exhibit Increasing Returns to Scale (IRS), a sign that they have not yet reached their optimal operational size. To improve the scale efficiency of these actors, it would be economically advantageous to consolidate their activities into larger production units, thereby reducing unit costs, rather than maintaining multiple small units with high average costs.

Conversely, fishers in Zone A are characterized by Decreasing Returns to Scale (DRS), indicating that they have exceeded their optimal scale. This situation may result from heterogeneous governance and a poorly structured market. To enhance their efficiency, it is essential to improve value chain governance and promote greater formalization of transactions.

3.3. Social Sustainability of the Value Chain

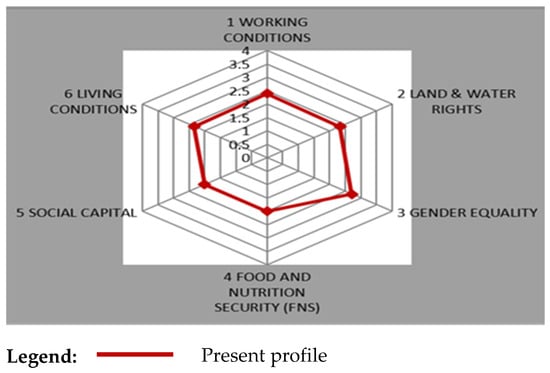

Figure 5 presents the social sustainability profile of the Macrobrachium spp. value chain in the MMP.

Figure 5.

Social sustainability profile of the Macrobrachium spp. value chain in the MMP.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the Macrobrachium spp. value chain within the MMP exhibits notable social weaknesses, particularly concerning working conditions, access to land and water, food security, social capital, and living conditions.

3.3.1. Working Conditions

At fishing and landing sites, the absence of adequate infrastructure (storage facilities, landing piers, access to drinking water, drying racks, etc.) degrades working conditions. Intermediary actors, particularly retailers, frequently rely on informal recruitment, without contracts or legal protection. This situation fosters the use of unpaid or low-paid labor, with limited adherence to safety standards, working hours, and social protection.

3.3.2. Access to Land and Water

Within the MMP, legislative frameworks provide limited security for land tenure and access to water resources, particularly for local communities and artisanal fishermen. While access to water remains free and unregulated, access to land is largely based on customary systems managed by traditional chiefs, which are socially recognized but lack a national legal basis.

3.3.3. Food Security

The Muanda territory, located in the coastal region of the country, has both agricultural and fisheries potential. Most of its fish production comes from artisanal fisheries, due to the sharp decline of the industrial fishing sector since the 1990s [2]. As a result, local production now represents only about 2% of the national fish output, estimated at 240,000 tons per year [12]. Although partially offset by increases in certain food crops (cassava, rice, eggplant, etc.), local agricultural production remains insufficient, maintaining a high dependency on food imports.

3.3.4. Living Conditions

Access to healthcare in the MMP primarily relies on health centers in Nteva (Zone A), Kibamba, and Katala (Zone B), supported by community relays responsible for awareness-raising, rapid malaria testing, and referral of severe cases. Although this system constitutes the local health backbone, its effectiveness is limited by the lack of suitable medical transport, hindering emergency evacuations, especially in remote areas.

Access to drinking water remains problematic: fishermen and fish traders often use river water, which promotes waterborne diseases. Sanitation infrastructure is virtually non-existent.

In the education sector, only one primary school (in Kimuabi) is in good condition. Others are poorly equipped. There are no secondary schools or vocational training centers on site. The distance and cost of secondary education in Muanda or Boma severely limit opportunities for youth.

3.3.5. Gender Equality

Analysis of gender equality reveals gender segregation in the Macrobrachium value chain, where women’s participation in fishing remains very limited or even non-existent. This exclusion can be explained by several factors, such as searching for and collecting materials, making traps by hand, spending long periods of time away from home at night, sometimes far from the family home, and prolonged exposure to the elements (sun, rain, wind).

3.4. Environmental Sustainability of the Macrobrachium spp. Value Chain

The analysis reveals that the value chain activities significantly compromise its environmental sustainability. The exploitation of timber species (Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn, Annona senegalensis Pers., Milicia excelsa (Welw.) C.C. Berg, Lannea welwitschii (Hiern) Engl, Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw., Raphia sp. and various lianas) for the construction of pirogues, traps, and housing exert notable pressure on the MMP’s resources. Crabs, often used as bait in Zone B, are not spared from this pressure.

The production of charcoal, widely used for cooking shrimp and other foods, exacerbates deforestation in the mangroves, leading to a progressive loss of biodiversity.

Fishing and marketing practices also generate pollution. Used batteries from torches and electronic scales, often discarded in the water, release heavy metals (mercury, cadmium, lead) that are toxic to aquatic fauna and humans. Furthermore, maritime transport is accompanied by fuel leaks, oil spills, and gas emissions, degrading water quality.

In terms of health, several risks affect actors in the sector: human losses due to shipwrecks, chronic back pain, waterborne diseases (diarrhea, typhoid fever) caused by contaminated water and poor hygiene practices, as well as various dermatological conditions provoked by prolonged handling of shrimp and exposure to water.

3.5. Value Chain Constraints and Opportunities

Fishermen face low mechanization, a lack of effective preservation means, an absence of permits, and fragile organization, exacerbated by weak administrative presence, military harassment, and a legal vacuum. Pressure on stocks raises concerns about their sustainability. However, the permanent availability of shrimp, access to dynamic markets, and the presence of technical and financial partners offer opportunities to professionalize and strengthen the sector’s resilience.

Fish traders, despite their dominant position in production sites, face significant logistical challenges: distance from ice production units and poor ice quality, rudimentary transport infrastructure, poor network coverage, and difficulties in accessing credit. On the other hand, they benefit from year-round product availability, good market outlets (Boma, Muanda, Kinshasa), and active transporters.

Retailers, with weak professional organization, suffer from limited access to financing and the refrigeration equipment essential for transport to distant urban markets like Matadi and Kinshasa. Their logistical performance is further hampered by recurrent traffic congestion on National Road 1 (RN1). Nevertheless, their high bargaining power, proximity to production zones for those based in Muanda and Boma, and access to electricity constitute strategic assets to be strengthened to improve their competitiveness.

Beach restaurateurs, generally poorly organized, face precarious hygiene conditions, marked by the absence of hand-washing facilities and limited access to electricity. Yet, the freshness of the product, its gastronomic value, and tourist appeal are levers for valorization.

Finally, consumers, despite limited purchasing power and high prices, benefit from direct access to a local, fresh product available year-round. This direct link between production and consumption strengthens the local resilience of the chain.

4. Discussion

4.1. Value Chain Functioning

Freshwater giant prawns of the genus Macrobrachium (notably M. vollenhovenii and M. macrobrachion) constitute an essential resource for African artisanal fisheries [13]. Within the MMP, this value chain involves five main actors: fishers, middlemen, retailers, restaurateurs, and consumers. Interactions are largely based on interpersonal relationships, providing local flexibility but increasing fishers’ dependence on traders and limiting their bargaining power, a pattern also observed by Masirika et al. [14] in Lakes Edward and Albert.

Macrobrachium spp. are primarily marketed fresh to solvent urban markets such as Boma, Muanda, Matadi, and Kinshasa, corroborating observations by Blanc et al. [15] in Cameroon.

Advance-order sales, also reported for oysters in Senegal [16], reflect an optimization strategy related to the product’s high perishability. The joint analysis of catches and prices highlights strong seasonality and spatial disparities, confirming the income instability characteristic of artisanal fishing [17].

The weak organization of actors, combined with limited institutional support and distrust of associations, hampers collective structuring and access to services [18]. Marginal inclusion of women, due to socio-cultural norms and institutional deficits, restricts equitable governance of this value chain [19].

Additionally, the imbalance in weighing instruments (mechanical scales downstream versus electronic scales upstream) reflects the absence of fair regulation and a strong power asymmetry typical of informal sectors [14].

The near-total absence of traceability and sanitary control exposes consumers to health risks and undermines product credibility in urban markets. This governance deficit is not specific to the MMP but is recurrent in other African fisheries, such as the oyster sector in Senegal [16], where regulation is poorly applied and control systems are almost non-existent.

4.2. Financial and Economic Sustainability

The predominance of retailers, particularly in Kinshasa, in capturing the added value of the Macrobrachium spp. value chain has also been observed in other African fisheries [20]. This situation, which stems from the subordinate relationships established between producers and downstream actors, limits fishers’ access to more profitable markets. This constraint is mainly explained by their weak bargaining power, the lack of appropriate infrastructure for preserving fresh fish, and the difficulties in meeting the quality standards required by buyers [21]. Unlike these works, this study underscores the limited capacity of fish traders in the MMP to capture wealth. Despite 100% technical efficiency for fish traders in Zone B, their profitability is limited. It is even critical for fish traders in Zone A. High intermediate costs (transport, ice storage, logistics) restrict their margin and bargaining power. They must improve management to enhance profitability and technical efficiency. Finally, fishers, particularly in Zone B, display economic performance and technical efficiency, linked to open access to the resource and low operating expenses [15], which reduces their costs and allows them to capture a significant share of the value added, in contrast with the weak positioning observed in Benin [20].

4.3. Social Sustainability

Social assessment highlights structural vulnerabilities affecting community resilience and overall system sustainability. Working conditions are largely informal, characterized by the absence of contracts, non-compliance with safety standards, and lack of social protection, consistent with FAO [22] observations on artisanal fisheries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Land and water access rights remain precarious due to the conflicting coexistence of customary and state regimes. A comparable situation was observed in the central Chari basin in Chad, where the duality between customary and modern law leads to usage conflicts, vulnerability to expropriation, and low security for fisheries investments [23].

Despite modest agricultural progress, the Muanda territory remains dependent on food imports, highlighting a fragility in nutritional self-sufficiency and limiting the potential of local fishery resources as a lever for vulnerable populations [22].

Inadequate sanitary infrastructure and limited access to clean water and healthcare compromise community health [24]. Restricted access to secondary and vocational education, exacerbated by high costs, limits social mobility, particularly for girls [25].

4.4. Environmental Sustainability

Excessive pressure on unregulated fishery resources, also observed in other African artisanal fisheries [1,16,26,27], compromises ecosystem resilience and the long-term sustainability of the value chain.

Contamination of aquatic environments by organic and inorganic pollutants, including bioaccumulation of heavy metals in prawns, poses a health risk to local consumers [28].

Moreover, the use of unsanitary water during post-harvest handling and in popular restaurants promotes the transmission of waterborne diseases such as cholera and typhoid fever [29].

Finally, chronic exposure to contaminated water affects the health of fishers and riparian communities, notably through dermatological affections and musculoskeletal disorders linked to the physical demands of artisanal fishing [30,31].

4.5. Constraints and Opportunities

As observed in other African and Congolese artisanal fisheries [1,2,14,23], structural constraints (low mechanization, lack of effective preservation devices, absence of permits, and precarious organization) limit the expansion of fishing areas, increased catches, and commercial valorization. Furthermore, as highlighted by Ndoazen et al. [23], the weak institutional framework revealed in this study exposes fishers to increased vulnerability, military harassment, and legal insecurity linked to the conflict between customary and state land tenure systems. The absence of legal texts adapted to contemporary fisheries and environmental realities allows actors to operate freely, undermining organization and sustainability [32].

Strengthening associative structures constitutes a strategic lever for inclusive fisheries governance and the empowerment of small-scale producers. The example of Lake Kivu in the eastern part of the DRC, with the grouping of fishers’ associations “Synergie” which formalized artisanal fishing through adapted institutional mechanisms [33], is an illustration.

Several assets revealed in this study support a transition towards sustainable fishing: annual availability of Macrobrachium spp., relative security stability, proximity to dynamic urban centers, and the presence of institutional actors. Nevertheless, the national budgetary allocation to the sector (1%) remains insufficient to guarantee the effectiveness of these structures [2].

The lack of adequate infrastructure (landing ports, roads, storage equipment, and rudimentary transport means) constitutes a major constraint for fish traders and retailers downstream in the value chain. This deficit, associated with limited access to credit, characterizes the intermediary link in fishery chains in the DRC and promotes significant post-harvest losses, compromising profitability and sustainability [2].

Finally, the weak organization of restaurateurs and non-compliance with hygiene standards, also observed in Kisangani [34] and Abomey-Calavi [35], are explained by the absence of sanitary control and training in food hygiene.

5. Conclusions

This study on the value chain of giant freshwater shrimp (Macrobrachium spp.) in the MMP highlights a sector with high potential but hindered by numerous constraints. A vital resource for local populations, this value chain is organized around five categories of actors (fishermen, fish traders, retailers, restaurateurs, consumers) linked by non-formalized relationships, thereby limiting the bargaining power of fishers. Deficient economic governance, marked by a lack of traceability and sanitary control, leads to an unequal distribution of value added, favoring urban retailers, particularly in Kinshasa.

On the social front, major structural and functional challenges persist, such as precarious living and working conditions, insufficient access to essential services, low inclusion of women, and obstacles to youth education, compromising their empowerment. The environment is under increasing pressure due to unregulated exploitation and significant pollution, threatening the resource’s sustainability and consumer health. Overall, this value chain remains economically, socially, and ecologically fragile. To ensure its sustainability, it is crucial to establish regulatory mechanisms, strengthen local capacities, collectively structure the actors, and improve institutional and community coordination. In this regard, four key interventions are recommended:

- Establish a sustainable resource management framework, including biological rest periods, protection of breeding areas, and an authorization and monitoring system for fishers to control fishing pressure.

- Strengthen coordination among control agencies (Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN), naval forces, river police, maritime authorities, and fisheries administration) to enhance surveillance, traceability, and the enforcement against unsustainable practices, particularly in sensitive areas.

- Improve the efficiency of value chain actors through training in sustainable fishing techniques, upgrading local processing and preservation capacities (ice production, reduction in post-harvest losses), and promoting transparent price-setting mechanisms.

- Enhance the socio-economic inclusion of vulnerable actors by supporting the formalization of professional organizations, increasing women’s participation in downstream segments (processing and marketing), and improving access to basic social services to strengthen the resilience of fishing communities.

Finally, this study has certain limitations. It focused exclusively on Macrobrachium prawns harvested in the Congo River estuary, thereby excluding other areas of the MMP where the resource is also exploited. Moreover, the daily catch data are based on fishers’ self-reported declarations collected through non-probability sampling, which prevents an accurate estimation of the total production at the scale of the park. In addition, self-consumption and post-harvest losses elements that are essential to value chain analysis were not considered. These limitations highlight the need for further research combining participatory observation and systematic surveys covering the entire MMP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.K., V.M.Z., B.M. and J.-C.M.; methodology, F.L.K., V.M.Z., B.M. and J.-C.M.; software, L.P.B.B. and S.W.M.; validation, V.M.Z., B.M. and J.-C.M.; formal analysis: F.L.K., L.P.B.B., H.D.T., P.N.M., H.D.T. and S.W.M.; investigation, F.L.K.; data curation, F.L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.K.; writing—review and editing, L.P.B.B., H.D.T., P.N.M., P.F.E.E., V.M.Z., B.M. and J.-C.M.; visualization, F.L.K. and S.W.M.; supervision, V.M.Z., P.N.M. and J.-C.M.; funding acquisition, F.L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received additional funding from the French Embassy in the Democratic Republic of Congo through the FSPI Project (Solidarity Fund for Innovative Projects), University Cooperation: 2023-29. It was also supported by the Congolese Foundation for Medical Research, in collaboration with the Bayer Foundation (Germany), through the 2023 Regional “Women and Science” Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Academic and Research Council (CAR), the Ethics Committee of the UNESCO Regional Postgraduate School for Integrated Management of Forests and Tropical Territories (ERAIFT/UNESCO) (protocol code N’ERAIFT/CAR/BM/9/05/2024 and date of approval 9/05/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to all the fishers, fish traders, retailers, restaurateurs, and consumers who generously agreed to devote their time and share their experiences and knowledge for this study. Their contribution was decisive for the success of the field data collection. The authors also thank the local authorities and the management team of the MMP for facilitating field activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MMP | Mangroves Marine Park |

| VCA4D | Value Chain Analyses for Development |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| INTPA F3 | Sustainable Agri-Food systems and Fisheries |

| AGRINATURA | European Alliance on Agricultural knowledge for Development |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| Kg | Kilogram |

| cF | Congolese franc |

| APECREFUKI | Association of prawn fishermen of Fubu in Kimuabi |

| ASBL | Association Sans But Lucratif |

| P | Production |

| IC | Intermediate Consumption |

| VA | Value Added |

| CF | Fixed Costs |

| CRS | Constant Returns to Scale |

| VRS | Variable Returns to Scale |

| DRS | Decreasing Returns to Scale |

| IRS | Increasing Returns to Scale |

| NOI | Net Operating Income |

References

- Jacquemot, P. L’Afrique Face à L’épuisement de Ses Ressources de la Pêche Maritime. Policy Brief, n°35/24. 2024. Available online: https://www.policycenter.ma (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- FAO. Plan Prioritaire de Relance de la Pêche en République Démocratique du Congo 2021–2030; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fao.org (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Bondjembo, T.; Lingbelu, I. Document Évaluatif sur la Problématique D’eau Douce et la Situation des Écosystèmes et des Espèces Halieutiques/Aquatiques des Cinq Provinces du Grand Équateur Démembré. Online Report 2020. Available online: https://www.ctidd-rdc.org (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- MECNDD. Stratégie et Plan d’action Nationaux de la Biodiversité (2016–2020). Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/cd/cd-nbsap-v3-fr.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Grant, I.F. Les Invertébrés Aquatiques; Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich at Medway, Chatham Maritime: Kent, UK, 2016; pp. 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sintondji, S.W.; Gozingan, A.S.; Sohou, Z.; Taymans, M.; Baetens, K.; Lacroix, G.; Fiogbé, E.D. Prediction of the distribution of shrimp species found in southern Bénin through the lake Nokoué-Ocean complex. J. Aquac. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2022, 2, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhusu, K.F.; Mbadu, Z.V.; Michel, B.; Micha, J.C. A targeted resource, the giant freshwater prawns Macrobrachium species in the Mangrove Marine Park in DR Congo. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshimuanga, K.A.; Baudouin, M.; Luhusu, K.F.; Micha, J.C. Analyse fonctionnelle de la chaîne de valeur de la crevette géante d’eau douce (Macrobrachium sp.) du Parc Marin des Mangroves en République Démocratique du Congo. Rev. Sci. Tech. Forêt Environ. Bassin Congo 2022, 18, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, K.E.; De Angelis, N. (Eds.) The Living Marine Resources of the Eastern Central Atlantic. Volume 1: Introduction, Crustaceans, Chitons, and Cephalopods; FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–663. [Google Scholar]

- Bamenga, B.; Michel, B. Analyse Financière et Économique de la Filière du Café Robusta en Province de la Tshopo. Adv. Res. Econ. Bus. Strateg. J. 2025, 6, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, O.B.; Petersen, N.C.; Podinovski, V.V. Scale characteristics of variable returns-to-scale production technologies with ratio inputs and outputs. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 318, 383–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANAPI. Guide de L’investisseur; ANAPI: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2020; 167p. [Google Scholar]

- Koussovi, G.; Niass, F.; Bonou, C.A.; Montchowui, E. Reproductive characteristics of the freshwater shrimp, Macrobrachium macrobrachion (Herklots, 1851) in the water bodies of Benin, West Africa. Crustaceana 2019, 92, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masirika, J.M.; Mukabo, G.O.; Kasereka, P.K.; Jariekong’a, J.U.; Tulinabo, G.H.; Micha, J.C.; Ntakimazi, G.; Nshombo, V.M. Etude par la chaîne de valeur de la filière d’exploitation de Bagrus spp. dans la partie congolaise des Lacs Albert et Edouard. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2020, 14, 2304–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.P.; Drago, N.; Hummel, L.; Meke Soung, P.N.; Nguyen, H.; Ujeneza, N. Chaîne de Valeur des Crevettes de Grande Taille au Cameroun; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; 49p. [Google Scholar]

- Drago, N.; Kourgansky, A.; Thiao, D.; Mbaye, A.; Bernard, I.; Le Bihan, E. Chaîne de Valeur des Huîtres au Sénégal: Rapport d’analyse et de Conception de la Chaîne de Valeur; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; 353p. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Strengthening Coherence Between Social Protection and Fisheries Policies—Framework for Analysis and Action; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 671/1; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamesa, D.; Ferolin, M.C.; Sison, M.P.; Suson, P.; Porras, M.D. Harnessing community-based aquaculture for the sustainable development of small scale fishery. J. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 3, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollabodé, N.; Kpadé, C.P.; Montchowui, É.; Jabi, J.A. Performance économique des chaînes de valeur des crevettes d’eaux douces au Bénin. Cah. Agric. 2021, 30, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Value Chains, Post-Harvest and Trade. Available online: https://www.fao.org/voluntary-guidelines-small-scale-fisheries/key-thematic-areas/value-chains--post-harvest-and-trade/en (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainability in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/CA9229EN.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Ndoazen, A.; Mangar, P.; Sobdibe, P.Y.; Micha, J.C. Etude socio-économique, environnementale et fonctionnelle de la chaîne de valeur poisson dans le Bassin Central du Chari au Tchad. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2024, 18, 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhindo, V.M.; Kasereka, K.L.; Ahuka, O.L.A. Problématique de ramassage et transport des accidentes du trafic routier à Butembo, dans l’est de la République Démocratique Du Congo. KisMed 2021, 11, 503–509. [Google Scholar]

- Polepole, P.M. Analyse des Politiques et Instruments Nationaux, Régionaux et Internationaux sur la Participation des Femmes dans les Espaces Décisionnels en Éducation en RDC: Pour une Proposition des Nouvelles Méthodes; Rapport COCAFEM/GL & COFAS—EDUFAM; COFAS: Taranto, Italy, 2022; 43p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Integrating Inland Capture Fisheries into the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; FAO: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintondji, S.W.; Gozingan, A.S.; Sohou, Z.; Lacroix, G.; Huybrechts, P. Les Enjeux de la Gestion Durable des Crevettes de la Lagune Nokoué au Bénin: Réglementation, Conservation et Sensibilisation. CEBioS, Policy Brief 2025, N° 18; Institute of Natural Sciences: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyegeme-Okerenta, B.M.; West, L.O. Potential Toxic elements in shellfish from three rivers in Niger Delta, Nigeria: Bioaccumulation, dietary intake, and human health risk assessment. Environ. Anal. Health Toxicol. 2023, 38, e2023011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministère du Plan. Plan Stratégique Multisectoriel D’élimination du Choléra et Contrôle des Autres Maladies Diarrhéiques en République Démocratique du Congo (2023–2027). 2023; 270p. Available online: https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/national-cholera-plan-dr-congo.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Adekola, J.; Fischbacher-Smith, M.; Fischbacher-Smith, D.; Adekola, O. Health risks from environmental degradation in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2016, 35, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiébaut-Rizzoni, T. Amorcer le Processus de Transition Écologique Dans la Pêche Artisanale: Apports d’une Approche Multi-Niveaux Pour l’implémentation d’un Filet de Pêche Biodégradable. Ph.D. Thèse, Université de Bretagne Sud, Lorient, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vambi, N.B.; Subi, M.O.; Tasi, M.J.P. Ruée vers les ressources halieutiques dans le Parc Marin des Mangroves à Muanda en République Démocratique du Congo. Rev. Afr. Environ. Agric. 2018, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Akonkwa, B.; Ahouansou, M.S.; Nshombo, M.; Lalèyè, P. Caractérisation de la pêche au lac Kivu. Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakule, L.L.; Amosi Kikwata, G.; Basandja Longembe, E.; Tagoto Tepungipame, A.; Kazadi Malumba, Z.; Panda Lukongo, K. Food hygiene in makeshift restaurant at Kisangani central market, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Rev. 2025, 6, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnelé, B.D.L.C.; Ouassa, P.; Vissin, E.W.; Gibigayé, M. Factors of Food contamination in street restaurants in the municipality of Abomey-Calavi in Southern Benin, West Africa. Int. J. Prog. Sci. Technol. 2023, 41, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).