1. Introduction

Human use of wildlife has existed for millennia [

1,

2], the impacts of which have been cited as contributing to biodiversity loss [

3,

4,

5]. There has been a long-standing ambition of International Governmental Organisations (IGOs), NGOs and governments to seek the alignment of conservation actions with poverty alleviation to engender mutual benefits from wildlife resources [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Trade in wildlife resources has been reported to provide direct use value to local communities [

10,

11,

12,

13] and as having conservation benefits when traded within a sustainable management framework [

9,

14,

15] following the ‘lose it or use it’ agenda [

16,

17]. However, relatively few case studies reported within the literature highlight the difficulties in achieving such aims. This was often due to either social or biological factors or a combination of both [

18,

19,

20].

Trade in wildlife species to supply global pet market demands has been reported across many taxa groups [

21], such as snakes [

22], shrimps [

23], primates [

24], crayfish [

25], chameleons [

26,

27] and amphibians [

28,

29]. Global conventions exist to monitor the sustainability of the international wildlife trade, principally the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), with member states reporting on international trade in species listed on any of the Convention’s three Appendices, including exports, imports, and re-exports [

30,

31,

32]. Following CITES interventions, trade-related impacts on the traded resource, which can include individuals and/or their derivatives, have been shown to have variable effects, both predicted and unpredicted [

27,

33,

34,

35] and countries have been reportedly expanding commercial activities in their wildlife. For example, Argentina’s annual trade in wildlife was reported to be worth millions of US dollars and one of the principal industries on the continent, significantly depleting the wildlife populations of South America [

10]. Furthermore, it has been stated that within Latin American countries, weak enforcement of environmental laws was one of the major reasons for facilitating the over-exploitation of wildlife [

36,

37,

38].

Avian taxa have been extensively utilised within the pet trade, with varying factors driving the demand, such as rarity value, singing abilities, aesthetic desirability, etc. [

21,

32,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. It has been estimated that approximately 45% of bird species were overexploited by the wildlife trade [

46]; however, the total number of individual birds involved in the trade and the values they generate vary greatly between species. For example, [

47] estimated that four million birds were legally traded annually. Brazil alone has been stated to supply up to 50,000 wild songbirds worth US

$630,000.00 year-1 [

40], while in Indonesia, at least 300 bird species were traded in wildlife markets and contributed US

$80 million to the national economy annually [

48]. Parrot and parakeet species were commonly cited as those in greatest demand [

21,

42], with Peru, Bolivia and Argentina recorded as major source countries [

49] and a greater demand reported for larger sized or rarer species [

45,

50]. For example, estimated retail values of between US

$5000–

$12,000 per hyacinth macaw and

$60,000–

$90,000 per lear macaw were reported in 2003 [

51], which equate to US

$7257–17,417 per hyacinth and

$87,083–130,624.24 per lear macaw in 2021.

However, no study has previously investigated, longitudinally, the levels of trade in Ramphastidae, a family of medium to large birds consisting of toucans, toucanets, mountain toucans and aracaris [

52]. Six genera exist in the Ramphastidae family (from here on referred to as Toucans), all relatively long-lived, slow breeding, frugivorous birds synonymous with tropical forests and considered keystone species and amongst the most endangered species of Neotropical Aves [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58] (

Figure 1). The levels of conservation status vary across species, as does their IUCN RED list status and whether CITES is listed or not (

Table 1), while alternative governance mechanisms also exist (see

Table 2). Despite Toucans being highly charismatic and trade reported within these species from the 1960s, there have been only a few accounts of trade. However, commonly, data presented were for very short periods, and the best historical dataset is a total of 2441 Toucans exported between 1968 to 1991 across a minimum of 24 species [

59]. More recently, it has been reported that

Ramphastos tucanus and

R. vitellinus were of conservation concern in Ecuador due to the trade [

60], and stated how international trade had contributed to

Andigena laminirostris,

R. ambiguous and

R. culminatus population declines [

61]. Alternatively,

R. sulfuratus was sold for up to US

$2000 in domestic markets within El Salvador [

62]. Despite the scarcity of literature on the Toucan trade, it had still been reported that

R. sulfuratus and

R. swainsoni were cited as species at risk from trade under the Central America Free Trade Area-Dominican Republic (CAFTA-DR) [

63]. Legislation has been reported to affect wildlife trade dynamics in various ways [

27], and many of the Toucan range states have existing legislation protecting them [

59].

Therefore, this study aimed to comprehensively review the extent and dynamics of commercial trade through the analysis of secondary datasets. The aim was directed to identifying the spatial and temporal trends, focusing on: (1) the major countries contributing to the supply and demand of Toucans, and primary sourcing methods, (2) notable trade routes, (3) significantly featured species, and (4) estimating the economic value of the Toucan. The entire CITES database record was analysed and presented to commence addressing this research gap.

The aim of this study was to robustly investigate the size of the trade in Toucans, highlighting those species in high demand, identifying the main export and import countries, the structure of the trade network and the economic value of the trade. Presently, these data and information are lacking in the literature and thus are not considered in current conservation management plans. Therefore, this study will fill current knowledge gaps to allow better future conservation plans and actions.

3. Results

A total of 22,218 individual toucans were exported between 1985, the first reported trading events, to 2018, the latest reported trading events, using the importer-reported CITES dataset. The majority of these individuals were reported as sourced from the wild (

n = 18,080, 81.4%), followed by ranched (

n = 2234, 10.1%), then captive bred (

n = 1349, 6.1%) with the remaining categories accumulatively accounting for 147 (0.6%) individuals. The 22,218 individuals traded were recorded across 10 species (

Table 4), with

Ramphastos vitellinus accounting for the most individuals (

n = 4783, 21.5%), followed by

Ramphastos toco (

n = 4276, 19.3%) and

Ramphastos tucanus (

n = 3809, 17.1%) making up the top three most traded Toucan species.

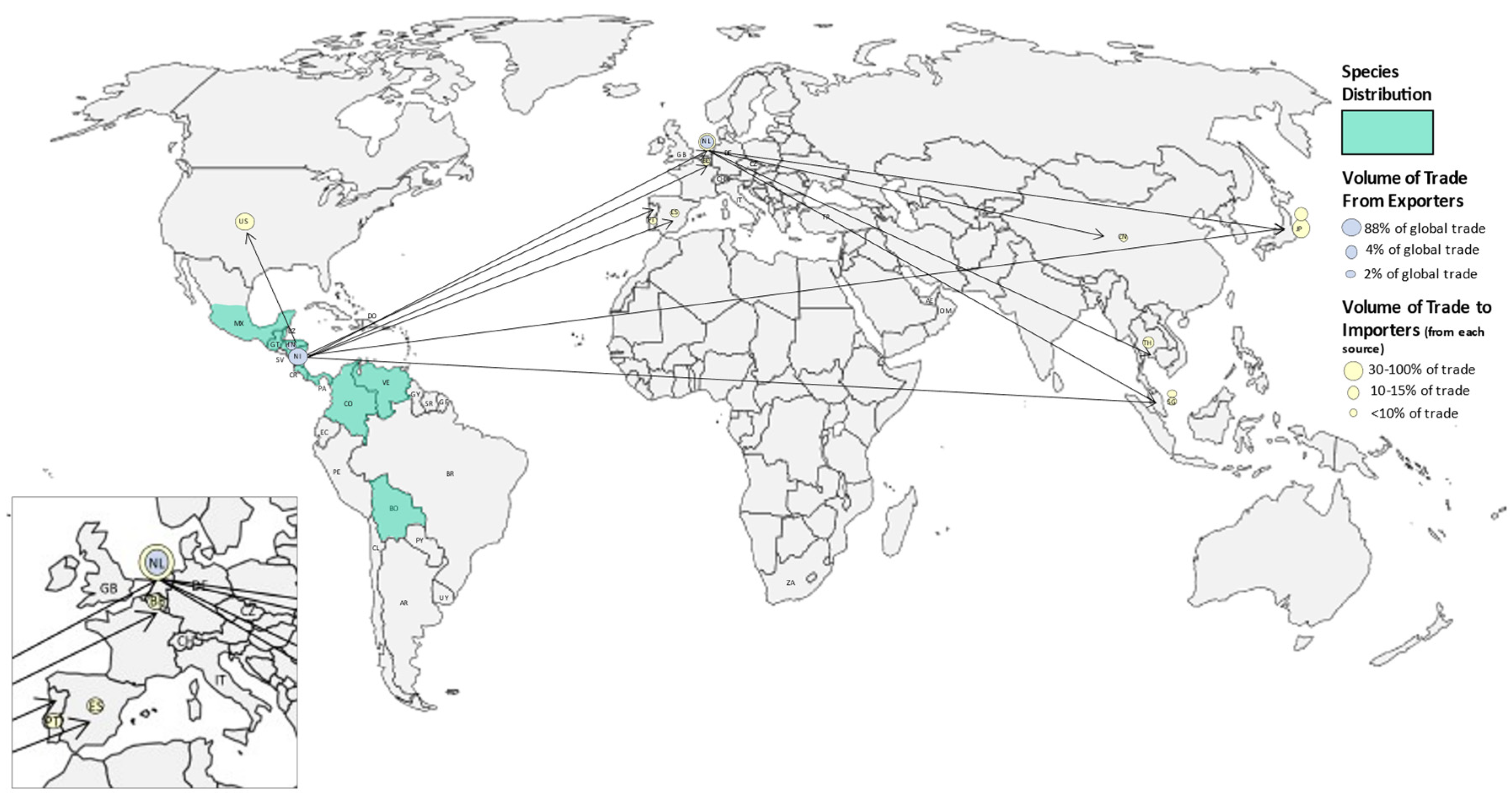

The four major export countries were all native range state countries of Toucans and together accounted for nearly 89% of the total exports (

Table 5); these being Guyana (

n = 8703 individuals; 39.2%) followed by Suriname (

n = 7422; 33.4%), Nicaragua (

n = 3100; 14.0%) and Paraguay (

n = 521; 2.34%). A total of 47 countries reported exporting or re-exporting Toucans, with those contributing >1% to the trade presented in

Table 5. Conversely, a total of 61 countries were reported importing Toucans, with 21 of those countries contributing >1% to the total number imported (

Table 6). Of those importing countries presented in

Table 6, European countries accounted for over 51% of the imported Toucan trade, with the Netherlands alone accounting for nearly 25% of imports.

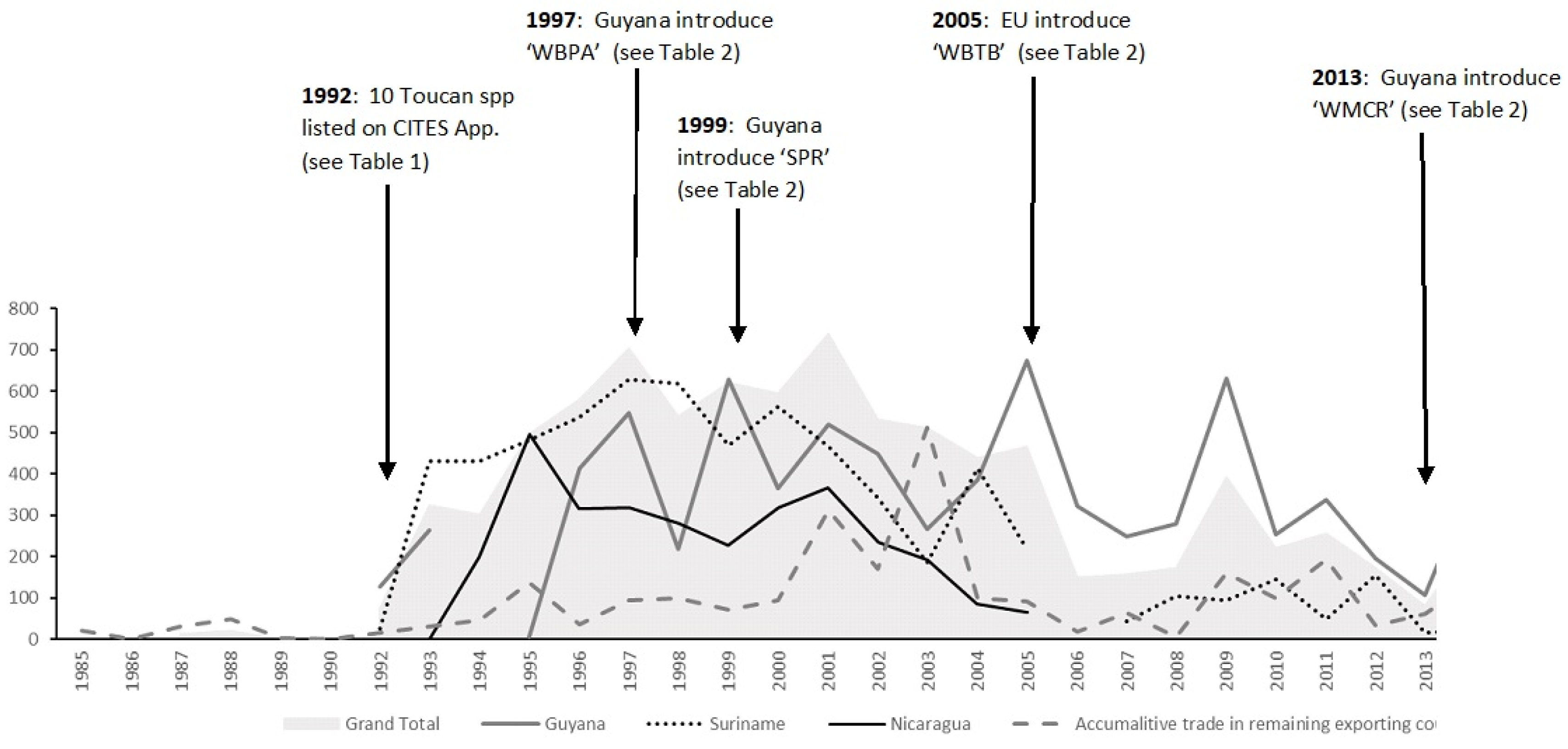

The trade dynamics of both the most commonly exported species (

Figure 2) and major export countries (

Figure 3) can be observed in the temporal trends of the trade. Also displayed in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 are relevant legislation/governance and when they were introduced. The period of trade can be divided into three using major legislative changes, these being; (1) pre Toucans being listed on CITES (pre CITES); (2) post CITES pre EU WBTB and (3) post EU WBTB (

Table 7). The ‘pre CITES’ section refers to a time period before any Toucans had been listed in CITES’ Appendices. The second period, ‘post CITES pre EU WBTB’, refers to a period after Paraguay’s CITES Management Authority (MA) had submitted a proposal to list 23 Toucan species (11 Pteroglossus spp and 12 Ramphastos spp) to CITES Appendices at the eighth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP8) held in Kyoto, Japan in March 1992. A total of 10 Toucan species were successfully adopted to CITES Appendix II or III (

Table 1). At the beginning of this period, there was a rapid, positive linear increase in the number of Toucans reported as exported between 1992 and 1997, which was best described by the linear regression equation log y = 264.34x + 526,302 when 1992 was taken as the year 0 (adjusted R

2 = 0.95,

n = 6,

p < 0.007). The third period is posting the introduction of the ‘European Communities (Avian Influenza) (Precautionary Measures) Regulations Order, 2005 (S.I. No. 678 of 2005)’, which witnessed the cessation of importing wild birds into member states. Across the three periods, the second period accounted for over 65% (14,523 individual Toucans), compared with 0.5% (period 1) and 34% (period 3), of the total number of Toucans being exported, equating to an average of over 1117 individuals exported per year within period 2 compared to just 25 in period 1 and 542 in period 3 (

Table 7).

A total of 24 online sites were found selling Toucans dated 2019 and 2020, advertising 15 species of Toucan. Retail prices ranged from the lowest for

Pteroglossus viridis at US

$440.62 up to US

$13,400 for

R. toco, with an average price of US

$4495.75 (

Table 8). Using the average 2020 Toucan retail price, a yearly real price value was calculated (in US

$), adjusting for inflation, which was then used to calculate the total yearly trade value for each trading year (calculated yearly real price × number traded in that year). The retail value of the trade varied across the three regulatory/legislative time periods, with the trade being valued at over US

$200,000, period 2 at over US

$42 million, and period 3 at nearly US

$29.5 million. The total real price valorisation of the Toucan trade was nearly US

$72 million at the retail scale.

The structural network (trade routes) of the trade at the international scale followed a similar pattern between four of the top six most heavily traded species (

R. vitellinus,

R. tucanus,

P. aracari,

P. viridis;

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7;

Table 4). For these four species, exports originated mainly from Guyana and Surinam, with destinations spread around the globe and fewer re-export country destinations observed. The international structural networks for

Ramphastos toco (

Figure 8) displayed a much wider geographic spread with exports sourced from south, central, and northern Latin American countries. Alternatively,

R. sulfuratus (

Figure 9) was majorly sourced from Nicaragua with globally spread destination countries. The Netherlands was a major and consistent destination country for these exports across all species as well as being a major re-exporting country itself. However, despite the high economic gains, the CITES quotas were not exceeded in the years reviewed (

Table 9), suggesting the countries traded within CITES defined sustainable levels providing robust ‘non-detrimental findings’ (NDFs) were conducted.

4. Discussion

It has been stated that Toucans perform important seed dispersal tasks within forest systems; such ecosystem services were not so well recognised before 1992. Furthermore, given their large size, slow growth rates and low fecundity [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58], it would be prudent to consider their regional population densities to be relatively low too. In addition to low population sizes, population declines have been reported across several Toucan species. For example,

Ramphostos toco has become rare in some northern localities of Argentina while an 11-year study in Paraguay reported sharp population declines in

R. toco,

R. dicolorus and

P. castanotis due to both habitat destruction and harvesting individuals for the pet trade [

59]. Similarly, IUCN Redlist assessments conducted in 2016 and 2018 (

Table 1) reported all but one species (

P. viridis; stable) of the 10 CITES-listed species as having decreasing populations while, of the remaining 40 species, 32 had decreasing populations, 5 * stable and 3 * unknown with many of these statuses not having changed from previous assessments in 2014. (

Table 1). Whilst there were a few species-specific variations, Guyana, Surinam and Nicaragua were the major exporting countries reporting over 86.5% of the exported birds (

Table 5). Therefore, even without knowing local trade structures, it would be only logical to consider those countries as having reduced Toucan populations regionally and, potentially, nationally, which means rewilding projects could be hindered or miss certain floral species, especially dominant tree species, within forest communities for those flora species where Toucan species performed as dispersal agents [

56,

57,

58].

With over 99% of Toucan exports being reported post the CITES listing and an incredibly rapid rate of increase, essentially from zero to over 1117 years per year within 5 years and continuing for the following 13-year period (

Table 7;

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Support for the trade in Toucan species was well established before the CITES listing, hence Paraguay’s rationale for its proposal to CITES CoP8. However, trade data presented by Paraguay were patchy, utilising import data reported by the US mainly, which reported 9821 individuals between 1968 to 1972 and 3427 individuals between 1984 to 1991 in 3 known Toucan species [

59]. For the period where reported exports overlap, the pre-CITES period, Paraguay’s CITES proposal recorded a total of 1899 individuals exported compared with just 102 (

Table 7) within the CITES dataset. Additionally, Paraguay’s CITES proposal named three species being exported that were listed as endangered, EN (

P. bitorquatus), vulnerable, VU (

R. culminatus) and near threatened, NT (

R. ambiguus), with all three species reported as having decreasing populations (

Table 1). Therefore, Paraguay’s actions in 1992 should be viewed positively for facilitating data capture, which has permitted a more robust review and, therefore, managed the legal trade. Concomitantly, a more robust review promotes a greater understanding of any conservation needs. Ten species of Toucan recorded a minimum of 22,218 individuals exported, which was much greater than previously presented values. This highlights that much greater conservation efforts need to be afforded towards Toucans and that these need to start at the earliest opportunity, which could be listing all the remaining Toucan species on CITES Appendices at CITES Cop19.

Whilst national legislation exists within many Toucan range state countries, concerns have been raised as to how well enforced such national legislations were [

36,

37,

51,

59]. For example, of the imports to the US between 1984–91, 48.6% were from Argentina despite explicit protective legislation being in place. It has been commonly reported that local and regional trade network actors will utilise ‘traditional’ trade routes that, depending upon the locality, will often cross regional and national borders [

38,

41,

59]. However, it has also been reported that due to the inherent secrecy around wildlife trade, it was often extremely difficult to obtain detailed information about networks, legal and illegal, both structural and economic, who filled the different actor roles, etc., which places serious constraints on any potential conservation initiatives [

27,

29,

41]. It should be deemed as a high priority to seeking to obtain data that allow the mapping of who occupies which actor roles, especially from collection to export, and the economics of the trade, which will be variable both across species and geographies. However, without this detailed information, it is unable to know whether the nearly US

$72 million generated by the trade at the retail level could be better distributed along the structural trade network and, thus, offer both greater economic opportunities to local communities’ concomitant with conservation benefits through habitat protection.

Whilst it was reported that national legislation within exporting countries was not being adhered to consistently [

36,

37,

51,

59], the trade’s dynamics (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) were affected by legislation impacting import countries, highlighting three legislative periods (

Table 7). Focusing on the third of these, the ‘post CITES listing & EU WBTB’ period, the Netherlands, a European region country, was the major importing country, accounting for nearly 25% of the reported total exports. Thus, with the emergence of several temporally and geographically spread avian influence outbreaks across Europe, the EU legislation banning wild bird imports was strictly enforced on the occasions of such outbreaks, which meant the cessation of imports to the Netherlands that could result in the peaks and troughs observed post-2005 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). However, despite these national/regional legislation impacts, the export of Toucans was still averaging over 542 individuals per year over those 14 years in just the 10 CITES-listed species. Considering Toucans are a slow-growing and breeding species, 542 individuals removed from the wild would have a significant impact on survival. Therefore, given the wide distribution of Toucans across many Central and Latin American countries, the management mechanisms responsible for wildlife trade, such as the Central American Wildlife Enforcement Network (ROAVIS) and South American Wildlife Enforcement Network (SudWEN), need greater commitment. Alternatively, biodiversity concerns can be written into trade agreements or partnerships (e.g., FTAs or TPAs), ensuring Parties adopt laws and measures to fulfil obligations under multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs), such as CITES [

51] or more broadly reaching agreements, such as the ‘Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean’ (ECLAC) or MERCOSUR agreement to which Guyana and Surinam are associate states. Furthermore, it has been proposed that FTAs/TPAs could operate as the framework to address the illegal wildlife trade in future agreements with countries that have a significant illegal wildlife trade, such as within U.S.-Peru TPA [

51].

Finally, it should be highlighted again here that this study has utilised and presented values developed from the imported reported CITES data. One should be aware of its implications, not least that the values presented should be considered minimum values. Also, at no point has the study presented aspects of illegal wildlife trade (IWT) whilst being fully aware that they are interlinked [

38] and were likely to be significant for Toucans that were high in individual value. Furthermore, it is important to note that domestic trade and confiscations of illegal birds were not included here, which could constitute a sizeable demand in itself, especially in regard to cultural dress, utilises the feathers of these and other bird species, and demand for pets. Thus, this study should be viewed as only just starting to highlight the need for much greater conservation attention and research orientated at Toucans as a matter of urgency. A review of the CITES NDFs for each of the main species is a good starting point to ensure trade is within sustainable levels, especially given the ecosystem services the species provide.