Abstract

Jakarta frequently experiences flooding due to several sources. To address this, the Indonesian government initiated the Great Garuda Seawall (GGSW), a structural countermeasure to protect the city from floods. This study assesses the effectiveness of the GGSW using a storm surge model. Four events were simulated to evaluate storm surge variations: without the GGSW, and in three construction phases (initial, intermediate, and completion phases). The results derived from the model depict the maximum storm-surge heights near the Jakarta coastline as 10 cm, 12 cm, 14 cm, and 24 cm for the events of Borneo Vortex, Hagibis–Mitag, Peipah, and Cold Surge, respectively. The effects also extended slightly to the Kepulauan Seribu Regency. Among the construction phases, the intermediate phase was identified as the most critical because the eastern reservoir gate remained open. In the completion phase, attention is needed for the gate connection between reclaimed lands and the Jakarta mainland, especially near the Bekasi region, where coastal erosion risk is high. Overall, the GGSW is not yet fully effective in preventing coastal flooding because some areas still experience no reduction in storm surge height. Furthermore, an evaluation based on GGSW construction phases is also important because this project generally involves reclamation islands and water pumps, which must be carefully cross-engineered.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Indonesia has decided to move its capital city from Jakarta on Java Island to Ibu Kota Nusantara (IKN) on Kalimantan Island. One of the reasons why is that there is an imbalance in the population distribution among the islands in Indonesia, where Java Island is home to almost 150 million people, and 56% of the total population of Indonesia lives there [1]. High population density has led to various problems, such as air pollution that leads to respiratory disease due to the large number of private vehicles used [2]. Included in these problems are water-related issues, which are often associated with hydrometeorological disasters, such as splintering of the water supply [3] and flood disasters [4]. From the Disaster Risk Assessment of Jakarta Province for the Year 2022–2026 published by the Jakarta Regional Disaster Management Agency [4], four out of five high-potential hazard disasters in Jakarta are related to hydrometeorological phenomena, such as floods, extreme waves, erosion, drought, and extreme weather. One of the disasters that occurs annually, and is always increasing, is flood disasters. Although the capacity of Jakarta’s society to handle flood disasters is moderate, the vulnerability is still high [4]. Therefore, flood disasters are given the highest priority to be handled in the disaster risk management of DKI Jakarta Province [4,5].

1.2. The Literature Review

Jakarta experiences three different types of floods: fluvial (typically occurring from the upstream of rivers and flowing into the northern part of Jakarta, leading to overtopping the dykes); pluvial (a flood caused by short-term high rainfall intensity increasing the infiltration capacity [6]); and coastal floods (occurring in the northern part of Jakarta coastline due to the increase in sea level). Moreover, the area close to the sea can also have tidal surges, whose variations in extreme ocean waves can impact coastal floods, including in North Jakarta.

One of the more severe flood events that happened in Jakarta occurred in January 2007, with total damages amounting to IDR 5.16 trillion [7] (equivalent to 17% of the national government budget for Jakarta). The pluvial flood was succeeded by the highest rainfall, exceeding 340 mm on February 2 at Pondok Betung Station [8], and it was allegedly associated with a cold anomaly and the Borneo Vortex event. Trilaksono et al. [8] identified the modulation of probability rainfall rate using cumulative distribution functions on a pentad time scale using time-lagged ensemble simulation. They observed various surges, highlighting that the surge event coinciding with the Jakarta flood was associated with a cold anomaly where the highest rainfall was recorded. A cold anomaly was detected from 29 January to 4 February because of a deep equatorial penetration identified. Further analysis revealed that the presence of a typical Borneo Vortex circulation, a low-pressure convergence scheme generated by northeasterly winds extending southeastward near Sumatra, is transporting easterly winds across West Java. This circulation pattern may contribute to storm surge dynamics. Even though there is an absence of direct tropical storms over Indonesia, the other vortex systems can indirectly influence oceanic and atmospheric conditions that contribute to heightening the storm surge.

In addition to sea level rise, land subsidence can worsen conditions. Andreas et al. [9] investigated that subsidence in many areas coincides with flood-prone zones, such as Pluit, Sunter, Kamal Muara, and Joglo. Using LiDAR-based elevation models, the study projected that approximately 26.86% of Jakarta could be below sea level by 2025, increasing to 35.61% by 2050. Takagi et al. [10] also conducted field surveys at a coastal community of Pluit Ward, Jakarta, in November 2017, and the land appears to be situated −3 m below the highest tide level. Latief et al. [11] examined the sea level rise for the past decade and future projections in the northern part of Jakarta Bay. Over the past decade, between 2003 and 2012, it rose by 8.4 cm, and further increases are projected for 2020–2040. These projections are strongly influenced by land subsidence; without its contribution, sea level rise is estimated to range between 59.5 and 171.9 cm. In summary, the rate of land subsidence is 1–20 cm per year. The combination of high rainfall, increasing sea level rise, and land subsidence could produce flooding to flow in Jakarta, starting from North Jakarta, where flood-prone areas dominate.

The Indonesian government has planned a giant sea-wall land reclamation project as the primary disaster solution in the North of Jakarta [12], namely, the Great Garuda Seawall (GGSW), or sometimes it is called National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) [13,14]. Currently, the GGSW is ongoing in its initial phase (phase A), which includes coastal and river wall constructions over a length of 38.9 km, planned to be completed by 2030 [15]. Garschagen et al. [16] used document analysis and original empirical household survey data to review and evaluate existing adaptation measures and to analyze the transformational pattern from previous risk reduction approaches. The results show that the GGSW is likely to transform Jakarta’s flood hydrology scheme. The GGSW construction can also influence hydrological behavior, like increasing sea level rise and water discharge, so its design needs further improvement [14] and requires a comprehensive review to meet technical assessments [17]. In addition, from the point of view of land subsidence, the GGSW is not quite enough to tackle inundation in Jakarta [18,19], and will not succeed without a sewage system [20]. Based on Latief et al. [11], who modeled two scenarios of whether land subsidence was stopped in 2030 or continued, the simulations show that the walls effectively avoid flood at first, but will lose effectiveness in 2040 if land subsidence is still happening.

Januriyadi et al. [19] assessed the GGSW based on an economic approach. In spite of the GGSW being able to slightly reduce the flood damage cost, it has still failed to reduce the uncertainty of floods in the future. For the small-scale flood structural countermeasure, Bricker et al. [21] also discussed the failure of a canal embankment to tackle the flood in Jakarta in 2013. Both modeling and field observation results showed that the canal embankment has experienced a reduction in canal gate capacity, so the seawater level can rise higher than expected. The failure of the canal embankment also happens because the location is on the lowest elevation level, so overtopping of water can possibly occur. Moreover, North Jakarta is experiencing significant land subsidence where the land surface is lower than sea level, and this can increase the potential for embankment failure.

In addition, when building a GGSW scheme, the bathymetry around Jakarta Bay, especially between the 17 reclaimed islands, became narrower. The narrowing of the channel can cause the tidal waves and water levels to increase in height as they move between the islands [22]. The changes in sea bottom topography could also change the water circulation around Jakarta Bay, which makes the area outside the land reclamation zone experience increased water levels [23]. It becomes important to fulfill the need for an engineering and science-based approach that must consider the potential failures and how to ensure the effectiveness of structural countermeasures. The water level and surge height increase after reclamation [23,24], in which the GGSW also has several reclamation phases.

1.3. Research Objective

A phenomenon that can directly influence coastal flooding is storm surge. Storm surge is simply water that is pushed toward the shore, generated by the combination of forces of the wind and low air pressure around the storm [25]. Some storm surges are associated with strong storm phenomena, and then they can produce high water levels near the coast. In Indonesia, storm surge is not as strong as in the mid or high latitudes because of the smaller Coriolis effect. Because of that, limited storm surge research has been conducted [26]; rather, other phenomena may influence storm surge in the equator, such as the Borneo Vortex, Cold Surge, Madden–Julian Oscillation, etc. Based on a survey on the knowledge of storm surges, 55% of respondents in North Jakarta said they did not know what they were [10]. This underlines the need for strengthening awareness of storm surge risks for society. Ningsih et al. [23,26] conducted an analysis of storm surge in Jakarta Bay using residual water levels that were calculated by removing tidal components from the total water level. Ningsih et al. [23] used the Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS) for three scenarios for modeling, such as before, after, and the differences between the construction of the GGSW during the Hagibis–Mitag Typhoon. The results showed that the GGSW can lower the water height in some places, but it increases the height in reclamation areas that have narrow gaps. To improve upon previous research [23], this research adds several different phenomena and evaluates the effectiveness based on the phases of construction of the GGSW. Building upon those reviews, the objective of this research is to evaluate the effectiveness of the GGSW based on the three phases of construction of the GGSW using storm surge simulations during four different storms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

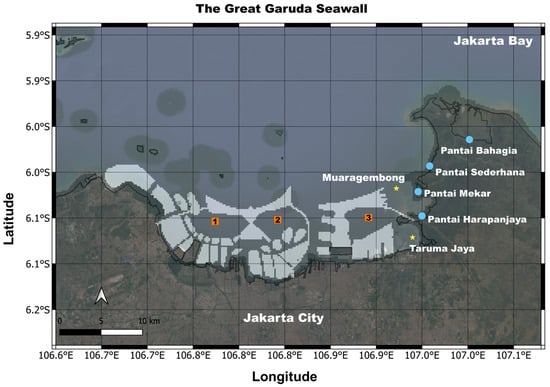

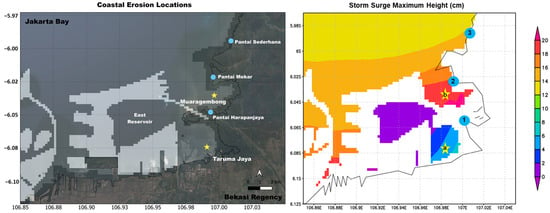

Based on Figure 1, the study area focuses on Jakarta Bay and Jakarta City, the current capital of Indonesia. The construction of the GGSW is planned alongside the northern coast of Jakarta, stretching from Tangerang on the west side to Bekasi on the east side. The project includes 17 reclaimed islands, with the largest island designed to represent the Indonesian national symbol, the Garuda Bird. There are also three reservoirs: the Western Garuda Reservoir, the Eastern Garuda Reservoir, and the East Reservoir. Two areas where storm surges are assumed as high are the Tarumajaya and Muaragembong districts, both located in Bekasi Regency. In addition, areas prone to coastal erosion are located along several beaches in Bekasi Regency, including Pantai Harapanjaya, Pantai Mekar, Pantai Sederhana, and Pantai Bahagia.

Figure 1.

Jakarta Bay and the master plan of the GGSW. The orange box represents the construction planning of Western Garuda Reservoir (1), Eastern Garuda Reservoir (2), and East Reservoir (3). The points of analysis include the Tarumajaya and Muaragembong districts, presented in star shapes, and several beaches that are prone to coastal erosion, presented by circle shapes, such as Pantai Harapanjaya, Pantai Mekar, Pantai Sederhana, and Pantai Bahagia.

2.2. Storm Surge Model

In this study, an evaluation of the effectiveness of the GGSW was performed using storm surge height as the primary indicator of coastal flood in North Jakarta. Four storm scenarios and four construction phases of the GGSW are simulated. The structure is defined as effective when the simulated storm surge height decreases after the seawall’s construction compared to the pre-construction condition.

Several storm-surge numerical models were used in previous studies; these include unstructured grid models such as ADCIRS [27,28,29], applied in the Caspian Sea and Southern Louisiana, and FVCOM [30,31], applied in the Coast of Korea and Scituate Harbor. Unstructured grid models can provide a good result with high resolution for complex coastal areas [28]. However, there are also structured grid models such as Delft3D-FLOW [32] and ROMS [23], which are computationally simple and commonly used for modeling Jakarta Bay as a study area.

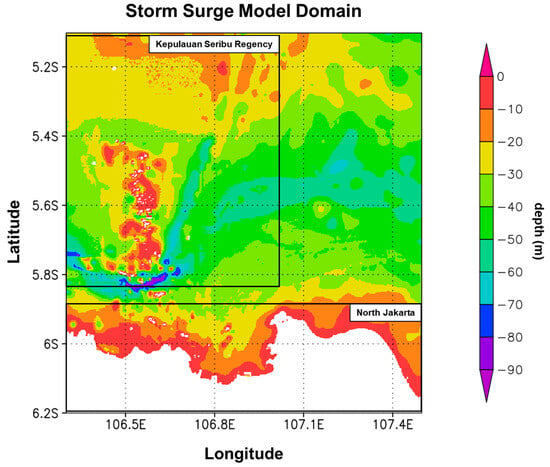

In our study, the storm surge heights were simulated using the storm-surge-structured numerical model developed by the University of Tokyo [33], which is appropriate for Jakarta Bay due to its simple, straight coastline. Since the focus of this study is to evaluate water level changes along the planned GGSW, this study focuses on Jakarta Bay covering the area from North Jakarta to the Kepulauan Seribu Regency (Figure 2). The domain is extended to Kepulauan Seribu because it consists of many small islands, and even more severe impacts could inundate these low-lying island areas. The term “Seribu” itself refers to “thousands” or the presence of many islands. This model was selected because the GGSW is constructed along the Jakarta Bay coastline, and the model is suitable for evaluating how such coastal structures reduce storm-surge-induced flooding.

Figure 2.

Storm surge model domain.

In the storm surge model, it is assumed that vertical motion is neglected compared to horizontal motion, and the pressure is assumed to be hydrostatic. Regarding these assumptions, shallow water equations (SWEs) are used as the fundamental governing equations. The model consists of two momentum equations—both in the continuity equation—and the equation of motion.

The continuity equation is described below:

The equation of motion is described below:

where and represent the linear flow rates in the and directions, respectively; implies the water surface elevation; is the gravitational force; is the total water depth; accounts for the water level increase caused by a decrease in atmospheric pressure; is the Coriolis force; is the shear stress at the sea surface; is the frictional stress at the seabed; and is the seawater density.

For open boundary conditions, they are defined as the edge of the model domain (open ocean). As a result, the open boundary provides a description of where water can flow in and outflow. Consequently, a gradient boundary condition is set to zero, where the sea level is determined from atmospheric pressure and wind pushed to the water. As calculated numerically, the water level is updated in each loop using the previous value, which corresponds to a zero-gradient condition.

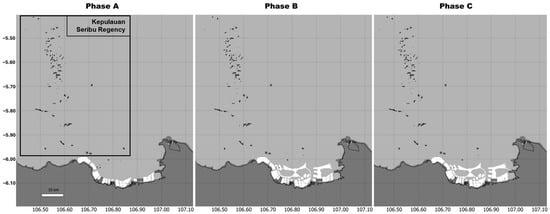

To analyze the effect based on the phases of construction, the bathymetry data from the Indonesian Spatial Agency [34]—with 6-arcsecond resolution (~180 m)—were used as the input data for the storm surge model. We used QGIS 3.34 software to produce three types of bathymetry data based on three phases of the GGSW using georeferencing tools. In the three phases of GGSW construction, namely phases A, B, and C (Figure 3), all of the reclamation area was defined as 1 m above sea level. The vulnerable locations of coastal erosion based on [35] are also depicted (Figure 1).

Figure 3.

The Phases of the GGSW’s constructions.

As shown in Figure 2, the phases of constructing the GGSW are depicted. The first phase of construction is phase A, in which the existing sea wall along North Jakarta’s coastline will be strengthened, and 17 small islands will be reclaimed near the shore [23]. The second phase, phase B, involves constructing the outer seawall as an extension of the wings of Garuda Island, reflecting the shape of Indonesia’s national mascot. In the outer sea walls, two gates are used to create offshore storage for river discharge to avoid North Jakarta from pluvial flooding during the wet season, particularly during the spring high tides. Because there is an absence of storage in the city, the only possible way to provide storage for river discharge is offshore by using two lagoons (Eastern Garuda Reservoir and Western Garuda Reservoir) for exchanged water (Figure 1). On one hand, to handle any pluvial flooding, the volume of water will flow into the lagoons and be pumped to the ocean outside [36] if the lagoons are full. The existing water-pumping site is located in Pantai Muara Baru near the reclaimed island [36]. On the other hand, if there is any rise in the water level from the sea because of coastal flooding, the gate will be closed to prevent water from entering. Finally, in phase C, the construction of another lagoon will begin (Eastern Reservoir), and the outer sea wall construction will be installed in the eastern part of Jakarta Bay to totally close off the lagoon.

2.3. Numerical Weather Simulations

In this study, the meteorological conditions used as forcing data for the storm surge model were derived from numerical weather simulations by the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) Model [37].

The WRF Model is an advanced mesoscale numerical weather prediction system developed for use in both atmospheric research and operational forecasting. It can generate simulations using real atmospheric data (from observations and analyses), as well as under idealized conditions.

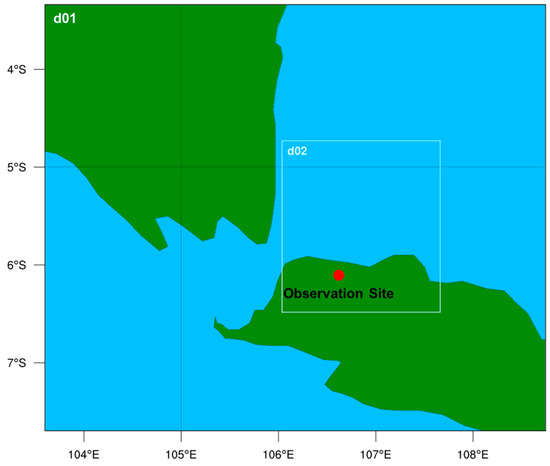

In the WRF Model, the NCEP Final Operational Global Analysis (FNL) data [38] were used as the initial and boundary conditions. We use a nested model in both computational domains with resolutions of 5 km and 1 km. Previous studies have demonstrated the use of a 1-kilometer inner WRF domain for Jakarta [39] and Indonesia’s future capital city [40] since it is appropriate for capital city-scale forcing. The coastline of North Jakarta (Figure 1), which includes an approximately 40-kilometer stretch of the GGSW, requires local atmospheric inputs. By using the two nested domains, the model is able to provide local pressure and wind variations that strongly influence storm surge in this region. For both domains, the domain grid size in the east–west and north–south directions is 115 × 98 and 181 × 196 grid points, respectively. These were centered at 5.521° S for latitude and 106.172° E for longitude on a Mercator projection (Figure 4). For the vertical direction, 42 sigma levels were defined as coordinates.

Figure 4.

WRF domain configuration. The red dot indicates the meteorological observation site at Soekarno–Hatta International Airport.

The physical schemes used in this study (Table 1) include the following: Kain–Fritsch for cumulus [41]; WRF Single-Moment 5-class (WSM5) for microphysics [42]; Dudhia for shortwave radiation [43]; the Rapid Radiative Transfer Model (RRTM) for longwave radiation [44]; the NOAH Land Surface Model [45]; Revised MM5 for the surface layer [46]; Urban-Canopy Model for urban surface physics [47]; and the Yonsei University (YSU) [48] scheme for the planetary boundary layer.

Table 1.

WRF parameterization.

To run the WRF and storm-surge models, we perform them with four cases of identified storms that influenced the storm surge height, as mentioned below:

- Case 1: Typhoon Peipah from 7 to 11 November 2007.

- Case 2: Typhoon Hagibis followed by Mitag from 18 to 27 November 2007.

- Case 3: Borneo Vortex from 21 to 26 January 2007.

- Case 4: Cold Surge from 28 January to 4 February 2007.

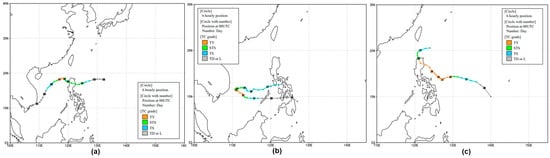

According to the Japan Meteorological Agency [49], Peipah formed over the sea far east of the Philippines, Hagibis formed over the sea east of the Philippines and moved westward, eventually impacting the southern part of the Philippines, and Mitag formed over the sea east of the Philippines (Figure 5). According to the tracking, the tracks of three typhoons were actually a bit far from Indonesia, especially around Jakarta Bay. Based on Trilaksono et al. [8], the Borneo Vortex consists of northeasterly winds over the South China Sea that change their direction to southeastward over and around Sumatra, and the wind is roughly eastward over West Java. A Cold Surge occurs because of the cold anomaly as the winds over the South China Sea become almost northerly when wind speed increases near West Java.

Figure 5.

Tracks of (a) Peipah, (b) Hagibis, and (c) Mitag. The growth of typhoons is represented as TY for Typhoon, STS for Severe Tropical Storm, TS for Tropical Storm, TD for Tropical Depression (Source: Japan Meteorological Agency).

Storm phenomena in cases 1 and 2 are identified based on Ningsih et al. [23,26], who analyzed the residual water level as a non-astronomical variable, and storm phenomena in cases 3 and 4 are identified based on Trilaksono et al. [8]. Notably, based on cases 1, 2, 3, and 4, the model periods are 120 h, 234 h, 138 h, and 186 h, respectively. For validating the WRF results, we use hourly METAR data from Soekarno–Hatta International Airport at a latitude of 6.270° S and a longitude of 106.889° E gathered by Iowa State University [50].

Within those four cases, we estimate the storm-surge maximum height that can be triggered by several storms, which can bring higher water levels along Jakarta’s waterways and increase sea level height.

3. Results

3.1. WRF Validation

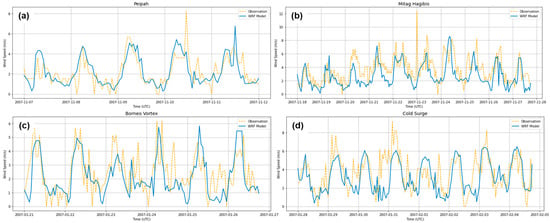

The WRF wind speed results were verified with the METAR observation data from Soekarno–Hatta International Airport (Figure 4).

Compared to the observation (Figure 6), the wind speed at 10 m from the WRF model in the cases of Peipah, Hagibis–Mitag, Borneo Vortex, and Cold Surge showed a correlation coefficient of 0.71, 0.58, 0.61, and 0.56, respectively. Meanwhile, the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) results yielded values of 1.07, 1.90, 1.28, and 1.73, respectively (Table 2). Overall, the WRF performed well in providing the inputs for storm surge models.

Figure 6.

Validation results from the WRF Model based on four cases: Peipah (a), Hagibis–Mitag (b), Borneo Vortex (c), and Cold Surge (d).

Table 2.

WRF verification.

3.2. Atmospheric Conditions near the Surface

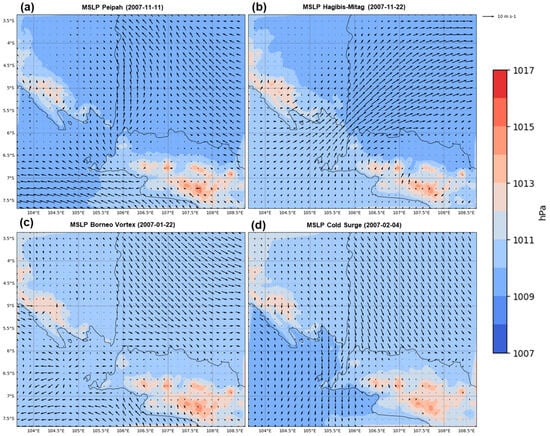

The analysis focuses on the days when these phenomena were suspected to have influenced the occurrence of storm surge around Jakarta Bay (Figure 7). The impact of these phenomena on meteorological conditions, derived by the WRF model, is shown as the 24-hour average 10-meter wind speed overlaid with mean sea level pressure during four different events: Peipah (7–11 November), Hagibis–Mitag (18–27 November), Borneo Vortex (21–26 January), and Cold Surge (28 January–4 February).

Figure 7.

Twenty-four-hour average of meteorological conditions near the surface during the period of (a) Peipah (00-23 UTC on 11 November 2007), (b) Hagibis–Mitag (00-23 UTC on 22 November 2007), (c) Borneo Vortex (00-23 UTC on 22 January 2007), and (d) Cold Surge (00-23 UTC on 4 February 2007) based on the WRF simulations.

During Peipah (Figure 7a), the mean sea level pressure exceeds 1009 hPa, in which two different wind flows—southeasterly (SE) and southwesterly (SW)—meet at Jakarta Bay. These two wind flows converge around Jakarta Bay, resulting in the wind velocity directed toward the coastline being relatively weak. During Hagibis–Mitag (Figure 7b), there is a strong southwesterly (SW) wind flow with a mean sea level pressure of 1009 hPa extending across Banten, where it turned to a westerly (W) direction near Jakarta Bay.

Different from Peipah and Hagibis–Mitag, the Borneo Vortex and Cold Surge have winds that are directed towards the coastline area of Jakarta Bay. During the Borneo Vortex (Figure 7c), the mean sea level pressure was around 1010 hPa. The dominant wind was northwesterly (NW), which slightly changed to a westerly (W) direction near the Jakarta Bay coastline. As the last case, the strongest storm surge can potentially feature from a Cold Surge (Figure 7d). This condition drove winds directly toward the coast, potentially accumulating seawater along the shoreline and increasing the risk of storm surge. A strong north–northwesterly (NNW) wind flow that was vertically aligned toward the coastline of Jakarta Bay occurred with a mean sea level pressure of 1010 hPa. This consistent wind flow continuously pushes on the sea surface, resulting in water accumulation along the Jakarta Bay area, highlighted particularly in the area where the GGSW was planned, which can generate a higher water level. Consequently, this event produces the strongest influence on storm surge.

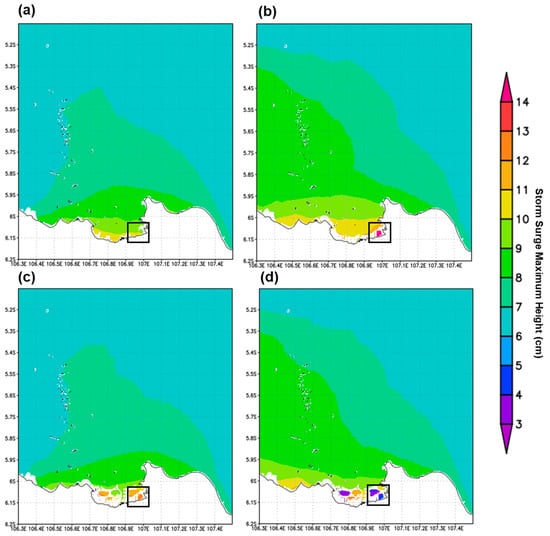

3.3. Results of Storm Surge Simulations

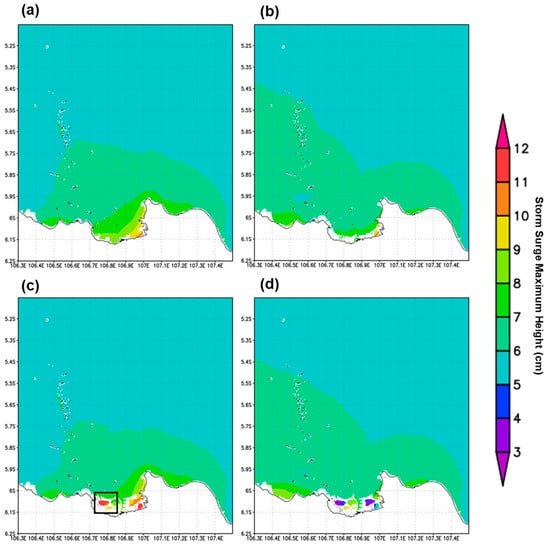

3.3.1. Typhoon Peipah

Based on the storm surge modeling results for Typhoon Peipah (Figure 8), two groups of storm surge patterns exhibited similarities in the spatial distribution of storm surge values. The first group consisted of models without the GGSW and GGSW phase B (Figure 8a,c), while the second group included GGSW phase A and GGSW phase C (Figure 8b,d). In the first group (without GGSW and phase B), the storm surge value of 8 cm only reached a part of the southern Kepulauan Seribu Regency.

Figure 8.

The maximum storm surge height during the period of Peipah with the following scenarios: (a) without GGSW; (b) with phase A of GGSW; (c) with phase B of GGSW; and (d) with phase C of GGSW. Black box indicates Tarumajaya District.

Meanwhile, in the second group (phases A and C), the storm surge value of 9 cm extended to cover the entire Kepulauan Seribu Regency, indicating an expanded area. Furthermore, differences in storm-surge maximum values were also observed in several locations. In phase A (Figure 8b), the maximum storm surge value was recorded, reaching over 14 cm in the area around the coastline of the location of Tarumajaya District, Bekasi (Figure 5). During phase B (Figure 8c), the storm surge height decreased to approximately 13 cm. In phase C (Figure 8d), when all gates were closed, the storm surge height significantly decreased to approximately 3–5 cm.

As shown in Figure 7a, because the wind was blowing in the direction out of the bay, the height of the storm near the Jakarta coastline was not very high.

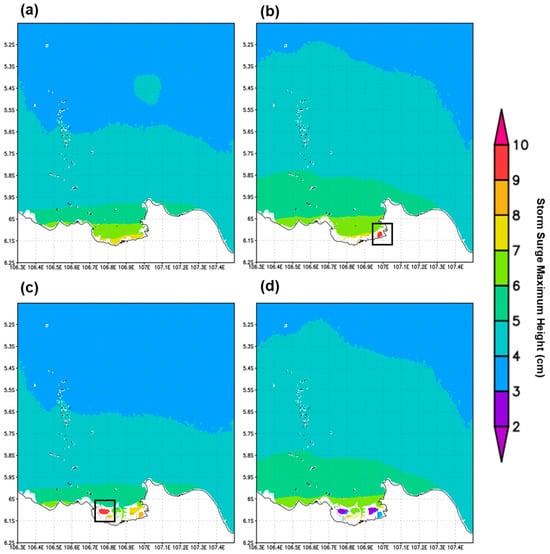

3.3.2. Typhoon Hagibis and Mitag

Based on storm surge modeling results for Typhoon Hagibis–Mitag, a pattern similar to that observed for Peipah occurred. Two groups of patterns showed similarities in the spatial distribution of storm surge values: phase B with no GGSW (Figure 9a,c), and phase A with phase C (Figure 9c,d). Unlike the previous two cases, during phases A and C, almost the entire Kepulauan Seribu experienced storm surge heights of around 7 cm, while the North Jakarta coast experienced a decrease to around 8 cm (phase A) and even to 0–4 cm when all gates were closed during phase C. In the phases without the GGSW and phase B, the Kepulauan Seribu Regency was divided into two zones of storm surge values: approximately 6 cm in the north and 7 cm in the south. The highest storm surge values still occurred along the coast of North Jakarta, reaching over 12 cm in the Western Garuda Reservoir area during phase B.

Figure 9.

The maximum storm surge height during the period of Hagibis–Mitag with the following scenarios: (a) without GGSW; (b) with phase A of GGSW; (c) with phase B of GGSW; and (d) with phase C of GGSW. Black box indicates the highest storm surge height in the Western Garuda Reservoir.

As shown in Figure 7b, because a strong southwesterly wind was blowing out of the bay, the storm surge did not develop significantly along the bay.

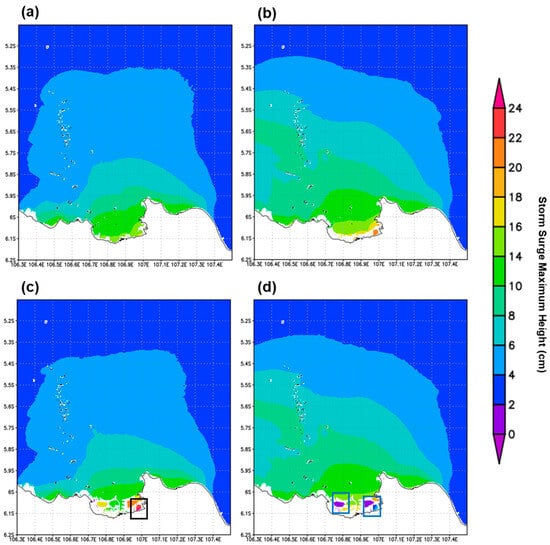

3.3.3. Borneo Vortex

The modeling results for the Borneo Vortex also show a similar pattern: without GGSW with phase B (Figure 10a,c), and phase A with phase C (Figure 10b,d). However, unlike the previous cases, overall, the storm surge values in the Borneo Vortex were relatively lower. The maximum storm surge values in the locations of Tarumajaya District, Bekasi (phase A), and at the Western Garuda Reservoir (phase B) (Figure 5) only reached around 10 cm, indicating that the Borneo Vortex event generated weaker storm surges than the other three cases. As shown in Figure 7c, the dominant wind was northwesterly, which slightly changed to a westerly direction near the Jakarta Bay coastline. This condition explains the relatively low storm surge values along Jakarta Bay.

Figure 10.

The maximum storm surge height during the period of Borneo Vortex with the following scenarios: (a) without GGSW; (b) with phase A of GGSW; (c) with phase B of GGSW; and (d) with phase C of GGSW. Black box indicates the highest storm surge height in Tarumajaya District and the Western Garuda Reservoir.

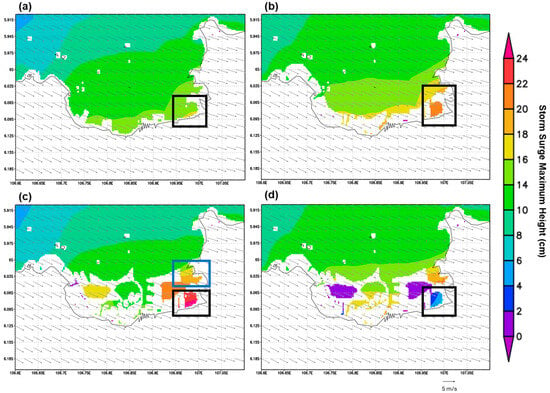

3.3.4. Cold Surge

From the four cases analyzed, Cold Surge had the highest storm surge value, reaching a maximum of more than 24 cm. Similarity patterns also developed into two groups: without GGSW with phase B (Figure 11a,c), and phase A with phase C (Figure 11b,d). In the first group (without GGSW and phase B) (Figure 11a,c), the Kepulauan Seribu Regency generally had a maximum storm surge value of around 6 cm, while the maximum value remained concentrated in the location of Tarumajaya District, reaching more than 24 cm. As shown in Figure 7d, the strong north–northwesterly wind flow that was vertically aligned toward the coastline of Jakarta Bay continuously pushes on the sea surface, resulting in water accumulation along the Jakarta Bay area, especially in Tarumajaya District. This event is considered to have the strongest influence on storm surge.

Figure 11.

The maximum storm surge height during the period of Cold Surge with the following scenarios: (a) without GGSW; (b) with phase A of GGSW; (c) with phase B of GGSW; and (d) with phase C of GGSW. Black box indicates Tarumajaya District as the highest storm surge height, while blue box indicates the lowest storm surge height in the Eastern Reservoir and Western Garuda Reservoir.

Furthermore, in the second group (phases A and C), the implementation of GGSW construction caused significant changes in the spatial distribution of storm surge values in Kepulauan Seribu Regency. This area was divided into three zones, with values decreasing from south to north at approximately 8 cm, 6 cm, and 4 cm, respectively. When all gates were closed in phase C, the Eastern Reservoir and Western Garuda Reservoir areas reached their lowest values, at around 0–2 cm, indicating the high effectiveness of the GGSW closure system in phase C in reducing storm surge height.

4. Discussion

4.1. Critical Considerations for the Construction of the Final Gate in Phase C

In this discussion, one storm period was chosen as producing the highest storm surge height, which occurred during the Cold Surge event (28 January–4 February 2007). In the storm surge model, we focused on discussing the storm-surge maximum height.

From the model, when the simulation without GGSW construction was run, the results show that the highest storm surge of about 14–16 cm occurred along the coastline of North Jakarta and reached 18 cm near Tarumajaya District (Figure 12a)—before construction. This happened because the north–northwesterly wind directly pushed seawater toward the northern coast of Jakarta based on the WRF model results. When the simulation included the GGSW’s phase A construction, the coastline alongside Tarumajaya District, Bekasi Regency, became the most prone area, with storm surge values exceeding 22 cm. From the WRF model, we can state that this increase was due to the NNW wind pushing seawater to the Tarumajaya coastline. Moreover, it was also caused by the narrowing effect between the planned reclamation islands in phase A, which restricted water flow and increased the storm surge height in that area.

Figure 12.

Storm-surge maximum height during the period of Cold Surge with the following scenarios: (a) without GGSW, (b) with phase A of GGSW, (c) with phase B of GGSW, (d) with phase C of GGSW, overlaid with wind vectors based on WRF results focused on Jakarta Bay. Black box indicates Tarumajaya District, while blue box indicates Muaragembong District.

During phase B (Figure 12c), the area of high storm surge expanded further eastward. In the Tarumajaya District itself, the storm-surge maximum height can reach more than 24 cm, followed by the adjacent Muaragembong District, with values around 18–22 cm. In addition, the Eastern Reservoir also remained vulnerable with a maximum 22 cm height because its gate was not yet fully closed. The construction plan for closing the gate is actually included in phase B, but it is only for the Western and Eastern Garuda Reservoirs, whereas the Eastern Reservoir gate was scheduled for closing only in phase C.

In phase C, when the eastern gate was completely constructed, the storm-surge maximum height in Tarumajaya District and the Eastern Reservoir significantly decreased to about 0–4 cm, whereas in Muaragembong District, the storm-surge maximum height is still vulnerable and will reach up to 22 cm. This is because the gate is only restricted to the Tarumajaya District. Therefore, it is important to highlight the need for shifting the gate to also restrict the water entering Muaragembong District. Moreover, constructing all three gates at phase B before continuing to construct the eastern section of GGSW construction in phase C is also important.

4.2. Critical Considerations Regarding Coastal Erosion in Muaragembong

Based on the results of the storm surge model, the Cold Surge with GGSW phase C case is also important. The area with the highest storm surge values was identified in Muaragembong, Bekasi Regency (Figure 13). In this area, there are three beaches potentially affected by storm surge: Pantai Harapan Jaya, Pantai Mekar, and part of Pantai Sederhana, with maximum storm surge heights exceeding 20 cm, 18 cm, and 16 cm, respectively. According to research by Solihuddin et al. [35], these three areas are vulnerable to coastal erosion because they experience both accretion and erosion simultaneously. Accretion is the process of coastal sediment accumulating on the coast, causing the coastline to advance seaward, while erosion is the process of sediment being removed, causing the coastline to retreat inland.

Figure 13.

The vulnerable area of coastal erosion and the maximum surge height. Star shapes indicate the districts (a) Tarumajaya and (b) Muaragembong, while bullet shapes indicate the beaches (1) Pantai Harapanjaya, (2) Pantai Mekar, and (3) Pantai Sederhana.

Severe coastal erosion in Muaragembong has been occurring since the 1980s, caused by the massive plantations of mangroves for marine animal husbandry and the reduction in sediment supply due to reservoir construction; these conditions have likely had a significant impact on coastal erosion in this area.

These findings are important indicators for the development of the GGSW, particularly the Eastern Reservoir, to consider the potential interaction between storm surge and coastal erosion. Therefore, it is important to consider the location of the gate connection point between the reclamation area and the Bekasi mainland, particularly along the Bekasi coastline, which is currently experiencing erosion. According to Solihuddin [35], this coastal erosion has already extended to the northernmost part of Bekasi, reaching as far as Pantai Bahagia (Figure 5).

5. Conclusions

This study simulated storm surge height changes before and during three phases of GGSW construction. To assess the effectiveness of the GGSW, storm surge heights generated by several storm phenomena were estimated during Typhoon Peipah (7–11 November 2007), Typhoon Hagibis–Mitag (18–27 November 2007), Borneo Vortex (21–26 January 2007), and Cold Surge (28 January–4 February 2007).

The storm surge simulations were conducted using wind speed and sea level pressure data as the primary forcing meteorological parameters, obtained from WRF simulations in the Jakarta Bay domain. Typhoons Peipah and Hagibis–Mitag originated from the Philippines, while the Borneo Vortex and Cold Surge were southwesterly winds from the South China Sea that shifted direction southeastward around Sumatra.

The simulation results show that the maximum storm surge height varies, from the highest to the lowest, as follows: 24 cm (Cold Surge), 14 cm (Peipah Typhoon), 12 cm (Hagibis–Mitag Typhoon), and 10 cm (Borneo Vortex). This indicates that the event associated with synoptic-scale forcing, such as the Cold Surge, produces higher storm surge height. Although Cold Surge and Borneo Vortex events are both synoptic phenomena that occurred near Jakarta, only the Cold Surge generated a significantly higher surge. In all events, the maximum value was identified around the Tarumajaya and Muaragembong districts, Bekasi. The construction of the GGSW was proven to influence the difference in storm surge values in all three phases (A, B, and C), both along the coastline of Jakarta Bay and in the Kepulauan Seribu Regency. However, the magnitude of reduction differs depending on the storm event strength and its spatial pattern.

From the research results, phase B is the most critical condition, especially when the Eastern Reservoir is not yet fully closed. In addition, the results show the need for increasing awareness when constructing many reclaimed islands. The reclaimed islands can narrow the gaps between the islands so that they can accumulate seawater and cause high water levels in the surrounding area. In addition, considering the location of the gate connection to close the Eastern Reservoir area is also important, because the surrounding area of the closing gate is a zone that is vulnerable to coastal erosion. Thus, it can be concluded that further studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the GGSW, particularly at each construction stage (phases A, B, and C), and to minimize the potential impact of storm surge, which can exacerbate coastal erosion.

Furthermore, the model results have several limitations. Firstly, the accuracy of the bathymetry data for the storm surge model needs improvement, as the actual conditions in Jakarta Bay and the Kepulauan Seribu Regency are more complex than the simplified bathymetry used in this model. In the current setup, all reclaimed islands were uniformly assigned an elevation of 1 m above sea level, which may not reflect real conditions. Secondly, the storm surge model represents only meteorologically induced surge, neglecting tidal constituents. As tides also contribute to total water levels, generating coastal flooding, future research should incorporate tidal components to provide a more complete representation of flood-generating processes. Thirdly, the WRF model still has limitations in fully capturing meteorological forcing for some synoptic-scale events, which affects the accuracy of the simulated storm surge response. Fourthly, more comprehensive studies are necessary to consider other flooding sources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.M. and K.T.; methodology, K.A.M. and K.T.; validation, K.A.M.; formal analysis, K.A.M.; investigation, K.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.M.; writing—review and editing, K.T.; visualization, K.A.M. and K.T.; supervision, K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to some colleagues who contributed through guidance and discussions, including Edi Riawan, Nining Sari Ningsih, Hartono Wijaya, Luthfiyah Jannatunnisa, and Hananda Dwi Mahetran (Faculty of Earth Sciences and Technology, Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Profil Penduduk Indonesia Hasil SUPAS 2015. 2016. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2016/11/30/63daa471092bb2cb7c1fada6/profil-penduduk-indonesia-hasil-supas-2015 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The Contribution of Outdoor Air Pollution Sources to Premature Mortality on a Global Scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooy, M.; Bakker, K. Splintered Networks: The Colonial and Contemporary Waters of Jakarta. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1843–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana. Kajian Risiko Bencana Nasional Provinsi DKI Jakarta Tahun 2022–2026; Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana (BNPB): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021; Available online: https://inarisk.bnpb.go.id/pdf/DKI%20Jakarta/Dokumen%20KRB%20Prov.%20DKI%20Jakarta_final%20draft.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Budiyono, Y.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Tollenaar, D.; Ward, P.J. River Flood Risk in Jakarta under Scenarios of Future Change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kiyohara, K.; Tachikawa, Y. Comparison of Fluvial and Pluvial Flood Risk Curves in Urban Cities Derived from a Large Ensemble Climate Simulation Dataset: A Case Study in Nagoya, Japan. J. Hydrol. 2020, 584, 124706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (Bappenas) Laporan Penilaian Kerusakan Dan Kerugian Jabodetabek 2007. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/91531036/Bappenas-2007-Laporan-Penilaian-Kerusakan-Kerugian-Jabodetabek (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Trilaksono, N.J.; Otsuka, S.; Yoden, S. A Time-Lagged Ensemble Simulation on the Modulation of Precipitation over West Java in January–February 2007. Mon. Weather Rev. 2012, 140, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, H.; Gumilar, I.; Anggreni Sarsito, D.; Pradipta, D.; Abidin, H.Z.; P Sidiq, T. Insight into the Correlation between Land Subsidence and the Floods in Regions of Indonesia. In Natural Hazards—Risk Assessment and Vulnerability Reduction; Antunes Do Carmo, J.S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78984-821-2. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, H.; Esteban, M.; Mikami, T.; Pratama, M.B.; Valenzuela, V.P.B.; Avelino, J.E. People’s Perception of Land Subsidence, Floods, and Their Connection: A Note Based on Recent Surveys in a Sinking Coastal Community in Jakarta. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 211, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latief, H.; Putri, M.R.; Hanifah, F.; Afifah, I.N.; Fadli, M.; Ismoyo, D.O. Coastal Hazard Assessment in Northern Part of Jakarta. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayatno, A.; Dinianyadharani, A.K.; Sutrisno, A. Scenario Analysis of the Jakarta Coastal Defence Strategy: Sustainable Indicators Impact Assessment. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 11, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wulp, S.A.; Dsikowitzky, L.; Hesse, K.J.; Schwarzbauer, J. Master Plan Jakarta, Indonesia: The Giant Seawall and the Need for Structural Treatment of Municipal Waste Water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, M.Y.; He, Z.; Xia, Y.; Li, L. Impacts of Sea Level Rise and River Discharge on the Hydrodynamics Characteristics of Jakarta Bay (Indonesia). Water 2019, 11, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinas Sumber Daya Air Provinsi DKI Jakarta Pengendalian Rob (NCICD). Available online: https://dsda.jakarta.go.id/pengendalian-rob/ncicd (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Garschagen, M.; Surtiari, G.A.; Harb, M. Is Jakarta’s New Flood Risk Reduction Strategy Transformational? Sustainability 2018, 10, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogie, R.I.; Adam, C.; Perez, P. A review of structural approach to flood management in coastal megacities of developing nations: Current research and future directions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Fujii, D.; Esteban, M.; Yi, X. Effectiveness and Limitation of Coastal Dykes in Jakarta: The Need for Prioritizing Actions against Land Subsidence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januriyadi, N.F.; Kazama, S.; Moe, I.R. Effectiveness of Structural and Nonstructural Measures on the Magnitude and Uncertainty of Future Flood Risks. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2020, 12, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.Y.C. Accelerating the Process for DKI Jakarta Wastewater Management Development in NCICD. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, J.; Tsubaki, R.; Muhari, A.; Kure, S. Causes of The January 2013 Canal Embankment Failure and Urban Flood In Jakarta, Indonesia. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. B1 (Hydraul. Eng.) 2014, 70, I_91–I_96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningsih, N.S.; Yamashita, T.; Aouf, L. Three-Dimensional Simulation of Water Circulation in the Java Sea: Influence of Wind Waves on Surface and Bottom Stresses. Nat. Hazards 2000, 21, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningsih, N.S.; Hanifah, F.; Yani, L.F.; Rachmayani, R. Simulated Response of Seawater Elevation and Tidal Dynamics in Jakarta Bay to Coastal Reclamation. Ocean Dyn. 2024, 74, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.L.; Huang, S.C.; Wang, R.F.; Zhao, X. Numerical Simulation of Effects of Reclamation in Qiantang Estuary on Storm Surge at Hangzhou Bay. Ocean Eng. 2007, 25, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Siek, M.B.L.A.; UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education (Netherlands); University of Technology (Netherlands). Predicting Storm Surges: Chaos, Computational Intelligence, Data Assimilation, Ensembles; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ningsih, N.S.; Suryo, W.; Anugrah, S.D. Study on Characteristics of Residual Water Level in Jakarta, Semarang, and Surabaya Waters–Indonesia and Its Relation to Storm Events in November 2007. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. (IJBAS-IJENS) 2011, 11, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova, A.; Myslenkov, S.; Arkhipkin, V.; Surkova, G. Storm Surges and Storm Wind Waves in the Caspian Sea in the Present and Future Climate. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerink, J.J.; Luettich, R.A.; Feyen, J.C.; Atkinson, J.H.; Dawson, C.; Roberts, H.J.; Powell, M.D.; Dunion, J.P.; Kubatko, E.J.; Pourtaheri, H. A Basin- to Channel-Scale Unstructured Grid Hurricane Storm Surge Model Applied to Southern Louisiana. Mon. Weather Rev. 2008, 136, 833–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Bunya, S.; Westerink, J.J.; Dawson, C.; Luettich, R.A. Scalability of an Unstructured Grid Continuous Galerkin Based Hurricane Storm Surge Model. J. Sci. Comput. 2011, 46, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.-J.; Jun, K.-C. Coupled Storm Surge and Wave Simulations for the Southern Coast of Korea. Ocean Sci. J. 2015, 50, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, R.C.; Chen, C.; Xu, Q. Coastal Flooding in Scituate (MA): A FVCOM Study of the 27 December 2010 nor’easter. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2013, 118, 6030–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Esteban, M.; Mikami, T.; Fujii, D. Projection of Coastal Floods in 2050 Jakarta. Urban Clim. 2016, 17, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K.; Sanuki, H.; Shibuo, Y.; Tajima, Y. Storm Surge Simulation in the Tokyo Bay under Future Climate Conditions Using Pseudo Global Warming Method. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. B2 (Coast. Eng.) 2018, 74, I_613–I_618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badan Informasi Geospasial (BIG) BATNAS–Batimetri Nasional (Indonesia) Dataset. Available online: https://tanahair.indonesia.go.id/portal-web/unduh/batnas (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Solihuddin, T.; Triana, K.; Rachmayani, R.; Husrin, S.; Pramudya, F.A.; Salim, H.L.; Heriati, A.; Suryono, D.D. The Impact of Coastal Erosion on Land Cover Changes in Muaragembong, Bekasi, Indonesia: A Spatial Approach to Support Coastal Conservation. J. Coast. Conserv. 2024, 28, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinas Sumber Daya Air Provinsi DKI Jakarta Pompa Banjir–Infrastruktur Pengendali Banjir. Available online: https://dsda.jakarta.go.id/infrastruktur/infrastrukturpompabanjir (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.; et al. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Model Version 4.1; National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR): Boulder, CO, USA, 2019; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) NCEP FNL (Final) Operational Global Analysis Data. Available online: https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds083.2/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Junnaedhi, I.D.G.A.; Inagaki, A.; Varquez, A.C.G.; Kanda, M. Evaluation of Multiple Simulated Sea-Breeze Events in Tropical Megacity Using High-Temporal-Resolution Observation Data. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 (Hydraul. Eng.) 2021, 77, I_1309–I_1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdillah, M.R.; Adysti, R.T.; Wijaya, W.; Junnaedhi, I.D.G.A.; Trilaksono, N.J.; Suwarman, R.; Marzuki, M.; Hidayat, R.; Miftahuddin, Y.I.; Kombara, P.Y.; et al. Urbanization and Global Warming Impacts of Indonesia’s Future Capital of Nusantara on Air Temperature and Urban Heat Island. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.S.; Fritsch, J.M. Convective Parameterization for Mesoscale Models: The Kain-Fritsch Scheme. In The Representation of Cumulus Convection in Numerical Models; Emanuel, K.A., Raymond, D.J., Eds.; American Meteorological Society: Boston, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 165–170. ISBN 978-1-935704-13-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Dudhia, J.; Chen, S.-H. A Revised Approach to Ice Microphysical Processes for the Bulk Parameterization of Clouds and Precipitation. Mon. Weather Rev. 2004, 132, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhia, J. A History of Mesoscale Model Development. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2014, 50, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlawer, E.J.; Taubman, S.J.; Brown, P.D.; Iacono, M.J.; Clough, S.A. Radiative Transfer for Inhomogeneous Atmospheres: RRTM, a Validated Correlated-k Model for the Longwave. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1997, 102, 16663–16682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, M.B.; Mitchell, K.E.; Lin, Y.; Rogers, E.; Grunmann, P.; Koren, V.; Gayno, G.; Tarpley, J.D. Implementation of Noah Land Surface Model Advances in the National Centers for Environmental Prediction Operational Mesoscale Eta Model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.A.; Dudhia, J.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Montávez, J.P.; García-Bustamante, E. A Revised Scheme for the WRF Surface Layer Formulation. Mon. Weather Rev. 2012, 140, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusaka, H.; Kondo, H.; Kikegawa, Y.; Kimura, F. A Simple Single-Layer Urban Canopy Model For Atmospheric Models: Comparison With Multi-Layer And Slab Models. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2001, 101, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Noh, Y.; Dudhia, J. A New Vertical Diffusion Package with an Explicit Treatment of Entrainment Processes. Mon. Weather Rev. 2006, 134, 2318–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Meteorological Agency. Annual Report on the Activities of the RSMC Tokyo-Typhoon Center 2007; Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA): Tokyo, Japan, 2007. Available online: https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/jma-eng/jma-center/rsmc-hp-pub-eg/AnnualReport/2007/Text/Text2007.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Iowa State University, I.E.M. IEM/ASOS Network Data–Indonesia. Available online: https://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/request/download.phtml?network=ID__ASOS (accessed on 8 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).