Traditional Agrarian Landscapes and Climate Resilience in the Rural–Urban Transition Between the Sierra de las Nieves and the Western Costa del Sol (Andalusia, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

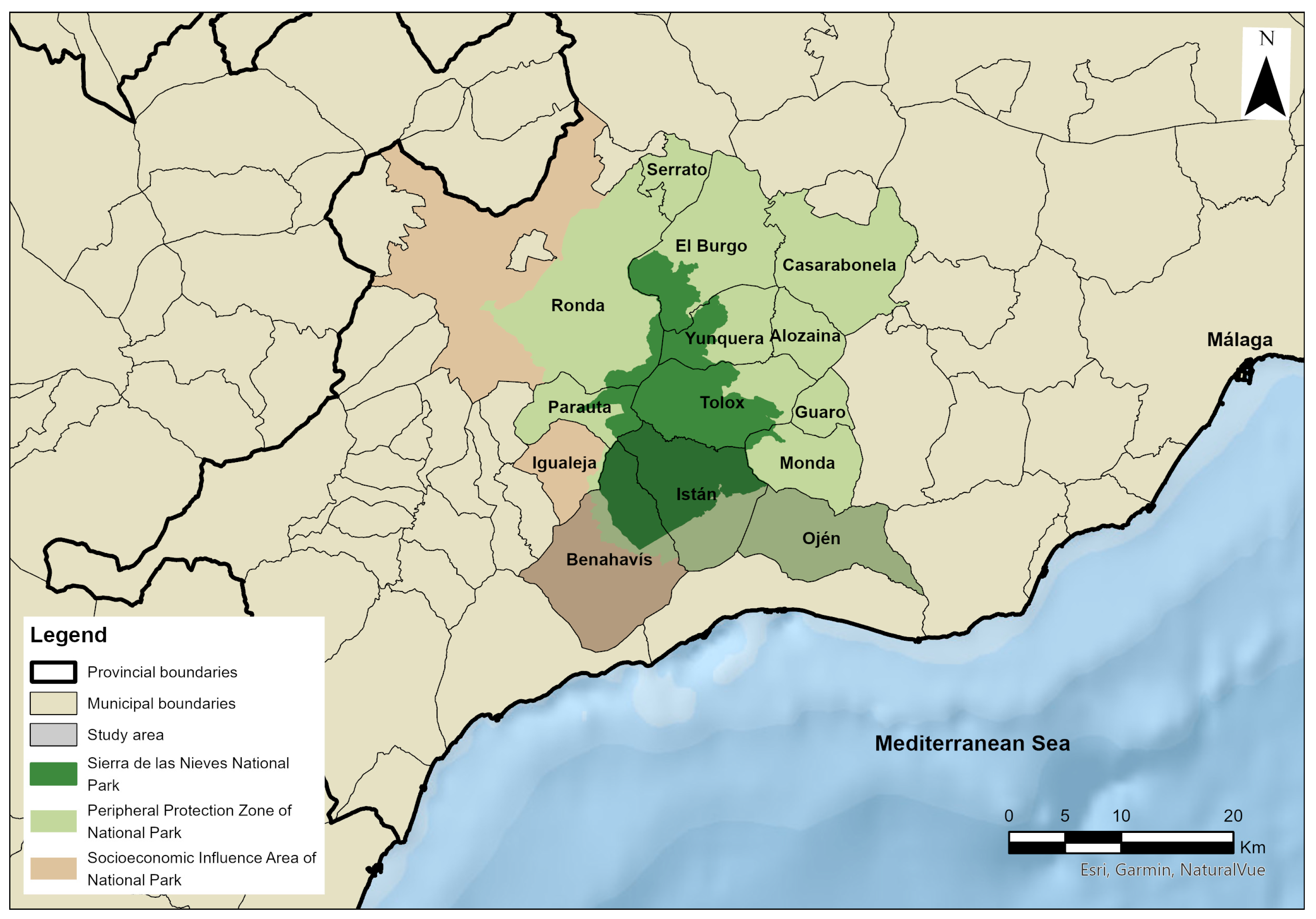

2.1. The Study Area and Its Geographical Context

2.1.1. Physical and Socio-Economic Setting of the Study Area

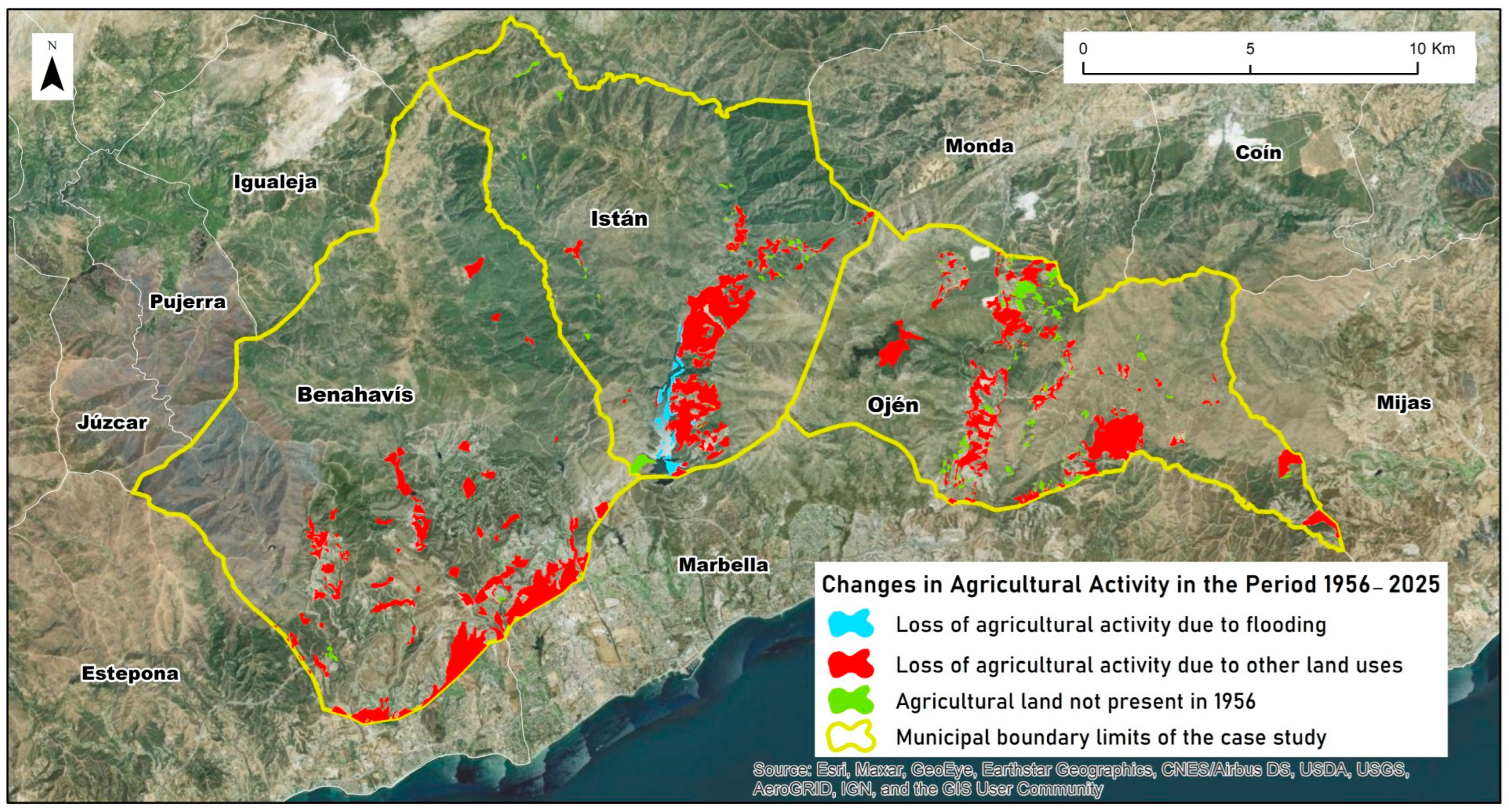

2.1.2. The Progressive Abandonment of Traditional Agricultural Landscapes in the Sierra de las Nieves—Costa del Sol Transition Zone

- -

- The difficulty in modernizing an agricultural system generated minimal profits. Investment was redirected toward tourism, as it represented an activity with greater and more immediate profitability.

- -

- The near impossibility of mechanization due to the challenging conditions of the physical environment characterized by steep slopes. The introduction of machinery for land management or crop harvesting was virtually unfeasible, limiting operations to animal labor and manual collection.

- -

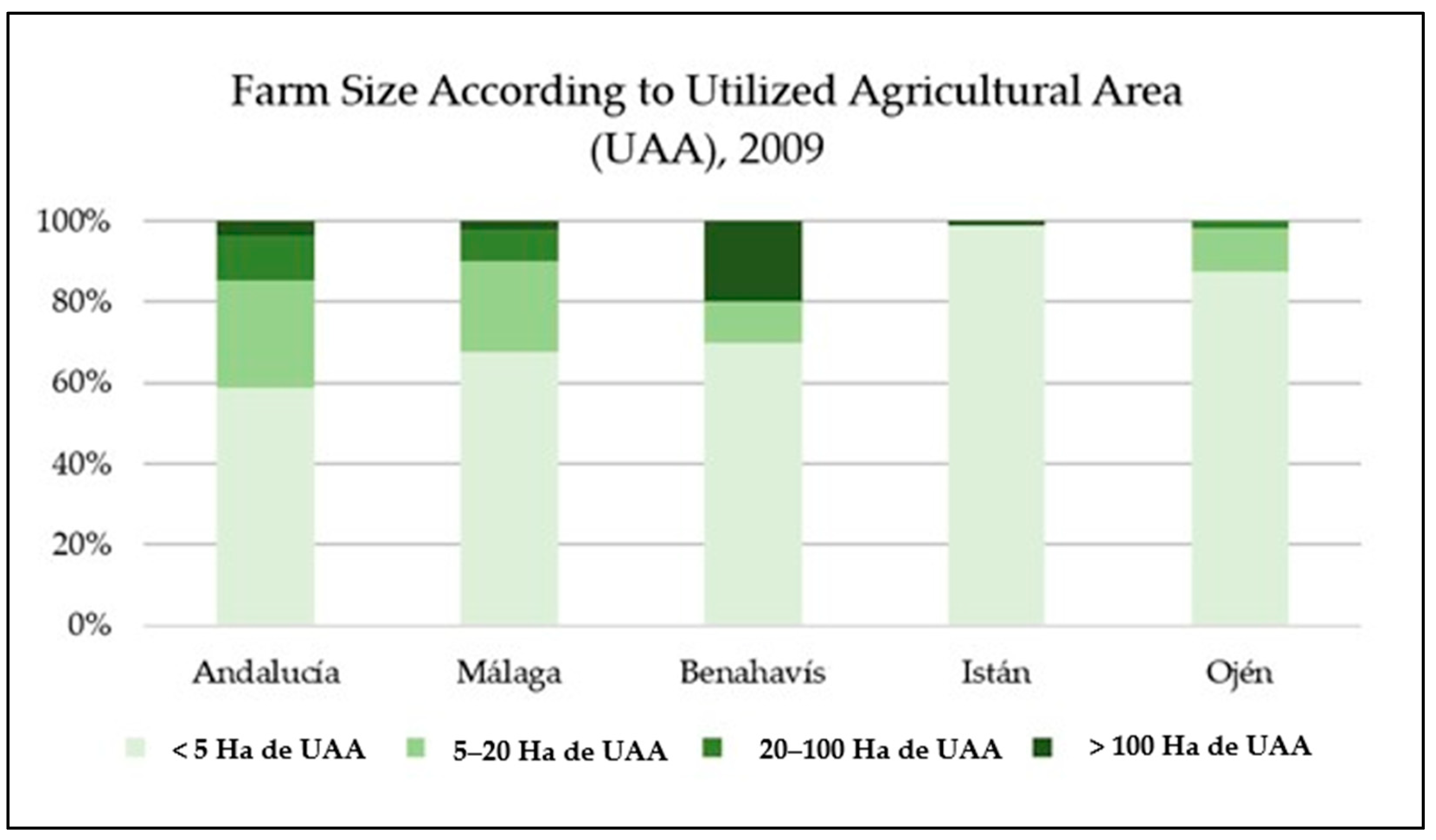

- The traditional smallholding culture, with farms of very limited size (Figure 5), and above all, the fragmentation and disorganization of plots inherited from historical land occupation models.

- -

- The progressively declining profitability of agricultural production, either due to competition from other regions where production and commercialization occurred under more favorable conditions, or because of the extensive nature of local farms, which lacked the capacity for large-scale production.

2.2. Methodology: Analysis Based on Land-Use Changes

3. Results

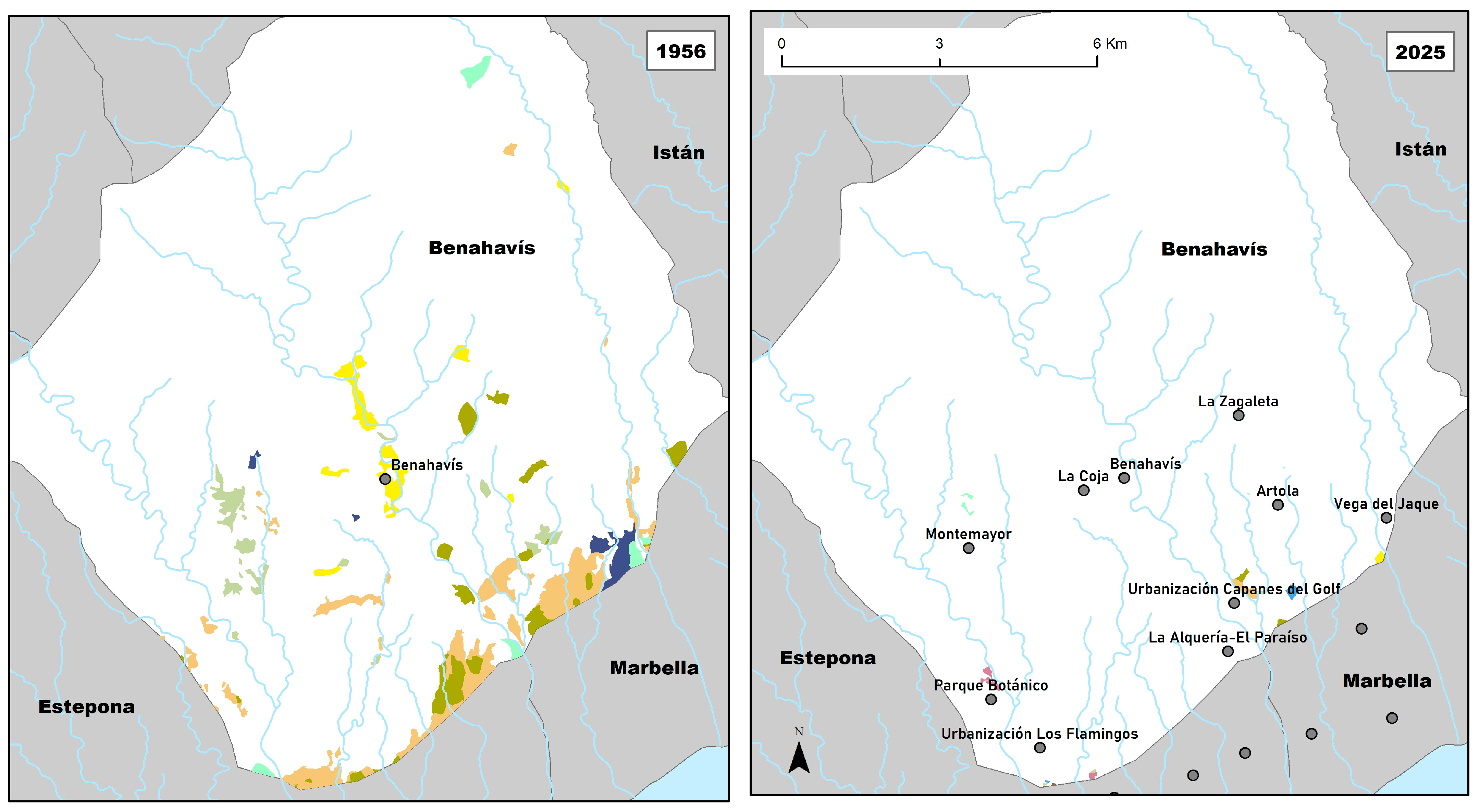

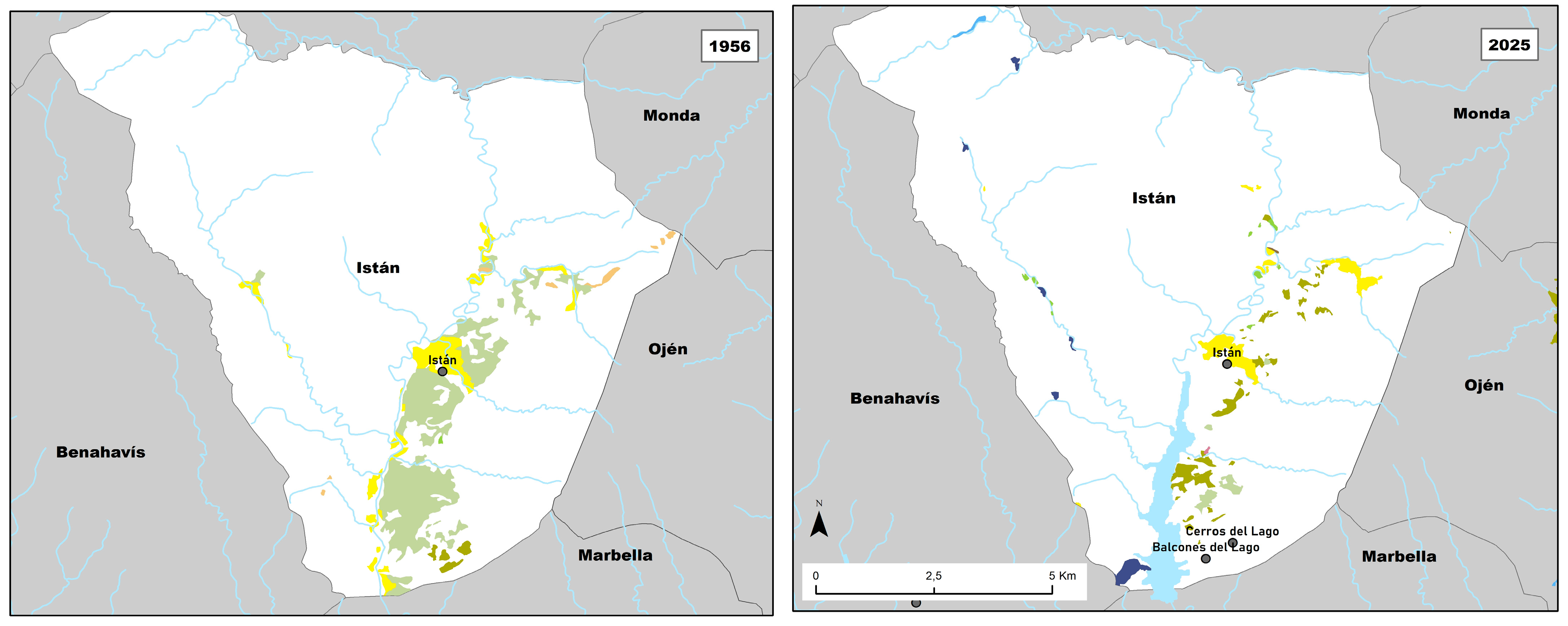

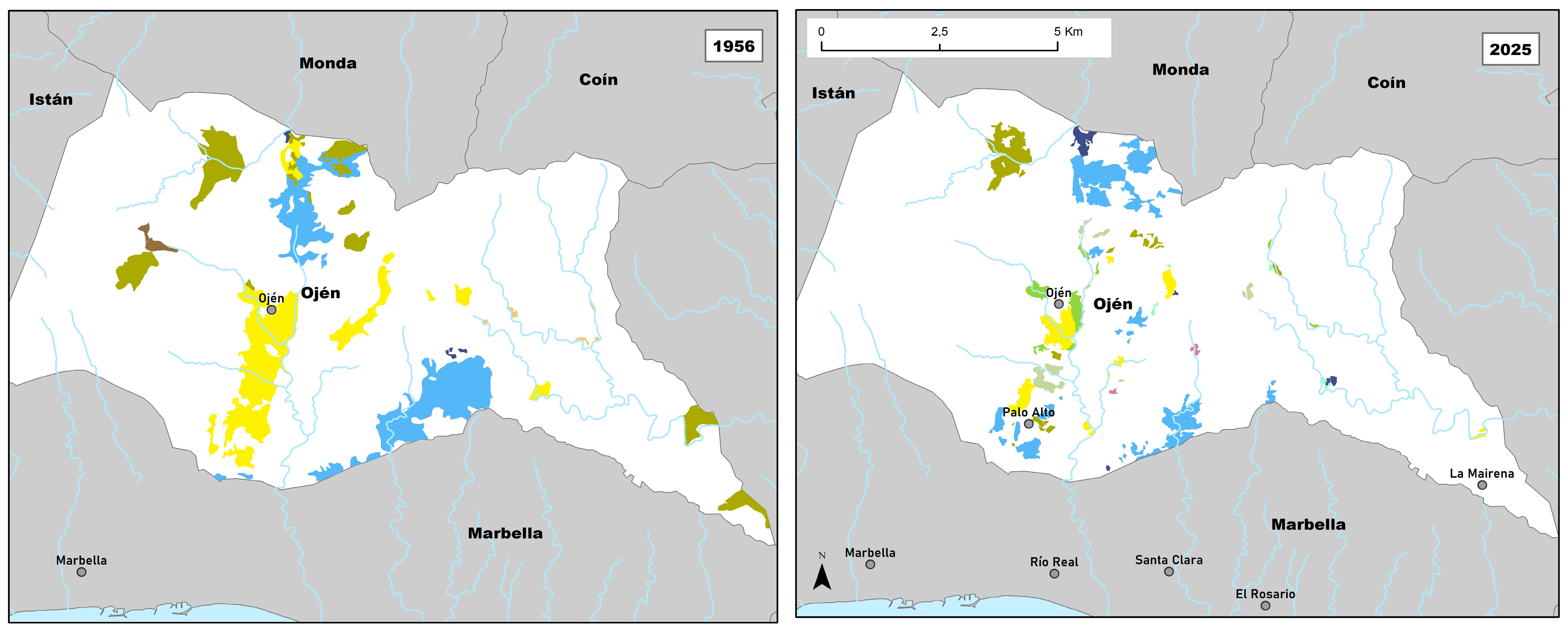

3.1. Characterization of the Ager and Its Evolution

| Benahavís | Istán | Ojén | Total Study Area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of agricultural land lost | 95.3 | 64.9 | 52.1 | 68.0 |

| % of agricultural land converted to urban use | 62.2 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 20.2 |

| % of agricultural land that has undergone renaturalization | 34.3 | 70.5 * | 59.8 | 52.8 |

3.2. Alteration of the Landscape and Consequences of the Loss of Traditional Agricultural Landscapes

- -

- Biodiversity, by reducing varied habitats for other wild species as agricultural landscapes become uniform.

- -

- Biological pest control, by undermining natural ecological balance due to reliance on pesticides typical of intensive, commercially oriented crops such as subtropicals.

- -

- Water resources and their regulation, as the surface area dedicated to crops like avocado—consuming enormous amounts of water—expands exponentially.

- -

- Soil conservation, through the use of fertilizers and amendments unnecessary for traditional agriculture and the loss of practices that prevented erosion.

4. Discussion

4.1. Agrarian Dynamics, Landscape Transformation and Territorial Vulnerability

4.2. Proposed Strategies for Adaptation to the Climate Crisis

- -

- Establishment of economic incentives aimed at maintaining traditional crops and the associated local land management practices and techniques, promoting agroecological models and sustainable agriculture respectful of the environment.

- -

- Financial support for the modernization of plots through the acquisition of machinery that allows agriculture to become a complementary activity to other occupations of the local population, optimizing the time dedicated to it and facilitating agricultural tasks. This measure would help attract younger generations with other primary jobs to engage part-time in agriculture, thus stimulating innovation.

- -

- Promotion of sustainable natural resource management through investment in infrastructures and technologies adapted to the needs of traditional agricultural practices.

- -

- Recognition and enhancement of the tangible cultural heritage linked to agricultural activity as a key element for reinforcing territorial identity.

- -

- Strengthening of the local agricultural social fabric, integrating traditional knowledge with scientific and technical advances, thereby fostering participatory territorial governance.

4.3. Limitations of Spatial Databases and Improvement Proposals

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- European Commission. Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe: The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/adaptation-and-resilience-climate-change/eu-adaptation-strategy_en (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; Florence, 20 October 2000; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000; Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/reference-texts (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Plieninger, T.; Höchtl, F.; Spek, T. Traditional Land-Use and Nature Conservation in European Rural Landscapes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire Management in Mediterranean-Type Regions: Paradigm Change Needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Landscape Fragmentation in Europe; EEA Report No 2/2021; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/landscape-fragmentation-in-europe (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Pausas, J.G.; Fernández-Muñoz, S. Fire Regime Changes in the Western Mediterranean Basin: From Fuel-Limited to Drought-Driven Fire Regime. Clim. Change 2012, 110, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Noblejas, H.; Orellana-Macías, J.M. Percepción del riesgo de incendio forestal y su impacto en la valoración de la vivienda: La transición entre la Sierra de las Nieves y la Costa del Sol (Málaga, España). BAGE. Boletín Asoc. Española Geogr. 2025, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.; Irwin, E.G.; Morrow-Jones, H.A. Consumer Preference for Neotraditional Neighborhood Characteristics. Hous. Policy Debate 2004, 15, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J.K.; Helsley, R.W. Lectures on Urban Economics; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, S.; Mourato, S.; Resende, G.M. The Amenity Value of English Nature: A Hedonic Price Approach. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2014, 57, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 9/2021, de 1 de Julio, de Declaración del Parque Nacional de la Sierra de las Nieves (Boletín Oficial del Estado, Número 157). 2021. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2021-10958 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales; Madrid, Spain. Madrid, Spain, 2025. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/parques-nacionales-oapn (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Pixabay. Available online: https://pixabay.com/es/photos/casas-rustico-paisaje-turismo-809394/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Mignon, C. Campos y Campesinos en la Andalucía Mediterránea; Servicio de Publicaciones Agrarias: Madrid, Spain, 1982; pp. 1–606. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Zotano, J. El Papel de Los Espacios Montañosos Como Traspaís del Litoral Mediterráneo Andaluzel Caso de Sierra Bermeja (Provincia de Málaga). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/4564 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- El Español. Available online: https://www.elespanol.com/malaga/20231227/pueblo-malaga-multiplica-poblacion-ultimos-anos/820168374_0.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Padrón Municipal; INE: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://sede.ine.gob.es/padronciudadano/pages/frmPresentacion.xhtml (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Ocaña-Ocaña, M.C.; Gómez-Moreno, M.L. Changes in Territorial Organization: Caso de estudio: Dinámicas territoriales en Málaga, la axarquía:¿Qué organización del territorio? Entre la urbanización difusa y la nueva agricultura. In España y el Mediterráneo: Una reflexión desde la Geografía española. Aportación española al XXXI Congreso de la Unión Geográfica Internacional; Alario Trigueros, M., Ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones: Valladolid, Spain, 2008; pp. 67–71. ISBN 978-84-612-5196-4. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2913891 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Censo Agrario 2009; INE: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://ine.es/CA/Inicio.do (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN). Centro de Descargas del CNIG. Coberturas de Ortofotografía Aérea Histórica (Vuelo Americano) y del Plan Nacional de Ortofotografía Aérea (PNOA); Ministerio de Transportes y Movilidad Sostenible: Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. CORINE Land Cover (CLC). Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura; Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA). Sistema de Información Geográfica de Parcelas Agrícolas (SIGPAC); MAPA: Madrid, España. Available online: https://servicio.mapama.gob.es/en/agricultura/temas/sistema-de-informacion-geografica-de-parcelas-agricolas-sigpac-/objetivos (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Castro-Noblejas, H.; De la Fuente-Roselló, A.L. Análisis de las relaciones entre tipologías constructivas y la expansión urbana en espacios turísticos litorales. Aplicación a la Costa del Sol Occidental (Málaga, España). In XVI Coloquio de Geografía Urbana: Procesos Urbanos y Turísticos en Escenarios Post-Pandemia. En Visiones Desde dos Continentes; Asociación Española de Geografía (AGE) y Universidad de Málaga: Málaga–Melilla, Spain, 27–30 June 2022; University of Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10630/24621 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- López Ontiveros, A. Caracteres geográficos de Andalucía. In Gran Atlas de España; Aguilar, S.A., Ed.; de Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Álvarez, J.R. Los Sistemas Agrarios Tradicionales de la Axarquía y la Serranía de Ronda; Diputación de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mayordomo-Maya, S.; Hermosilla-Pla, J. Heritage Evaluation of the Carob Tree MTAS in the Territory of Valencia: Analysis and Social Perception of the Ecosystem Services and Values from Cultivating It. Land 2024, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cacho, S.; Fernández-Salinas, V.; Hernández-León, E. Paisajes y Patrimonio Cultural en Andalucía: Tiempo, Usos e Imágenes; Vol. II; Andalusian Institute of Cultural Heritage: Seville, Spain, 2010; Available online: https://repositorio.iaph.es/handle/11532/263940 (accessed on 5 February 2025). (In Spanish)

- Mata-Olmo, R.; Molinero, F.; Sanz-Herráiz, C. Atlas de los Paisajes de España; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2003; pp. 1–683. ISBN 84-8320-236-0. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/servicios/banco-datos-naturaleza/informacion-disponible/paisajes.html (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Observatorio de Precios y Mercados (Junta de Andalucía). Datos básicos de Aguacate (Campaña 20242/5); Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2024. Available online: https://ws142.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/observatorio/servlet/FrontController?action=RecordContent&table=11114&element=5125231&subsector=& (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Observatorio de Precios y Mercados (Junta de Andalucía). Datos básicos de Mango (Campaña 2024/25); Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2024. Available online: https://ws142.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/observatorio/servlet/FrontController?action=RecordContent&table=11113&element=4965388&subsector=& (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Antrop, M. Why Landscapes of the Past Are Important for the Future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botequilha-Leitão, A.; Ahern, J. Applying Landscape Ecological Concepts and Metrics in Sustainable Landscape Planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K.; Marks, B.J. FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Quantifying Landscape Structure; USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, General Technical Report PNW-GTR-351; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station (PNW): Portland, OR, USA, 1995. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr351.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Desarrollo Sostenible, Junta de Andalucía. Guía de Buenas Prácticas Para la Producción Integrada en Olivar; Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2019. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/guia_pp_v1_2019011.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Junquera, V.; Rubenstein, D.I.; Levin, S.A.; Hormaza, J.I.; Vadillo, I.; Jiménez-Gavilán, P. Severe Water Crisis in Southern Spain Under Expanding Irrigated Agriculture: A Multidimensional Drought Analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2508055122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Landscape change and the urbanization process in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Blandy, S. Introduction: International perspectives on the new enclavism and the rise of gated communities. Hous. Stud. 2005, 20, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, J.M.; Romero-Padilla, Y.; Navarro-Jurado, E. Atributos urbanos contemporáneos del litoral mediterráneo en la crisis global: Caso de la zona metropolitana de la Costa del Sol. Scr. Nova 2015, 19, 515. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/37323 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Matos-Márquez, L.A.; Bardella-Castro, J.D.; Martins, E.L. Servicios ecosistémicos culturales y métodos de valoración: Una revisión sistemática. Tur. Soc. 2024, 34, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F. Valoración de los ecoservicios en los agroecosistemas españoles: Un estado de la cuestión. Obs. Medioambient. 2016, 19, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Baggethun, E.; de Groot, R.S.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: From early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Olmo, R. El paisaje, patrimonio y recurso para el desarrollo territorial sostenible. Conocimiento y acción pública. Arbor 2008, 184, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-García, P.; Domínguez-Gómez, J.A.; Zoido-Naranjo, F. Los paisajes como patrimonio cultural y natural: Perspectivas y retos. Obs. Medioambient. 2015, 18, 45–68. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5205662 (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Nogué-Font, J. El paisaje en la ordenación territorial: La experiencia del Observatorio del Paisaje de Cataluña. Estud. Geográficos 2010, 71, 415–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Álvarez-Montoya, J.M.; Pavón-Benítez, L.; Sánchez-González, P. Una mirada compleja al fenómeno de la despoblación rural. In El Camino Hacia las Sociedades Inclusivas; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 1223–1236. ISBN 978-84-1122-373-7. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/84233 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ramírez-Suárez, W.M.; López-Chouza, J.C.; Flores-Acosta, M.A.; Sánchez-Cárdenas, S.; Rodríguez-Morejón, P.L. La biodiversidad y los servicios ecosistémicos en sistemas agroecológicos. Una revisión. Pastos Y Forrajes 2024, 47. Available online: http://www.scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03942024000100002 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Santín-González, C.; Madrigal-González, J.; Cerdà-Serrano, X.; Pausas-Ferrer, J.G. Incendios Forestales; Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC): Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Padilla, J.; Martínez-Murillo, J.F. Análisis cartográfico del nivel de afectación de los incendios forestales sobre áreas urbanizadas en la Costa del Sol occidental (1991–2013). Papeles De Geogr. 2019, 65, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejería de Sostenibilidad, Medio Ambiente y Economía Azul, Junta de Andalucía. Plan Andaluz de Prevención y Extinción de Incendios Forestales (Plan INFOCA); Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2025. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/infoca (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Jara y Sedal. Available online: https://revistajaraysedal.es/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Cocampo. Informe Sobre la Estructura del Suelo Rústico en España; Cocampo: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://www.cocampo.com/es/es/noticias/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Informe-2025-Cocampo-sobre-la-Estructura-del-Suelo-Rustico-en-Espana.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Consejería de la Presidencia, Interior, Diálogo Social y Simplificación Administrativa, Junta de Andalucía. Perímetros de incendios forestales en Andalucía 2008–2024 [Dataset]; Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2007. Available online: https://portalrediam.cica.es/geonetwork/static/api/records/933fa6f2-1316-4e99-9baa-49c86d0cfc0c (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Consejería de Sostenibilidad, Medio Ambiente y Economía Azul, Junta de Andalucía. Red de Información Ambiental de Andalucía (REDIAM); Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2025. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/acceso-rediam (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Silva-Pérez, R. Agricultura, paisaje y patrimonio territorial. Los paisajes de la agricultura vistos como patrimonio. Boletín De La Asoc. Española De Geogr. (BAGE) 2008, 49, 309–334. Available online: https://bage.age-geografia.es/ojs/index.php/bage/article/view/786 (accessed on 21 February 2025). (In Spanish).

- Nadal-Romero, E.; García-Ruiz, J.M. Market as a factor in soil erosion: The expansion of new and old crops into marginal Mediterranean lands. Reg. Environ. Change 2025, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Noblejas, H. Paisaje y Desarrollo Inmobiliario en el Litoral Mediterráneo Andaluz: El caso de la Costa del Sol Occidental (Málaga). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2023. Available online: https://riuma.uma.es/xmlui/handle/10630/26729 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2018/1091 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 July 2018 on integrated farm statistics and repealing Regulations (EC) No 1166/2008 and (EU) No 1337/2011. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L 200, 1–29. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/1091/oj/eng?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (Annex 3); World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 1992; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide08-es.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Castro Noblejas, H.; De Paola, P.; y Vías Martínez, J. Landscape value in the Spanish Costa del Sol’s real estate market: The case of Marbella. Land 2023, 12, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero-Hernando, F. Atlas de los Paisajes Agrarios de España; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2013. Available online: https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/37111 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

| Benahavís | Istán | Ojén | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total agricultural plots | 52 | 1017 | 1955 |

| Size range (ha) | 0.1–1068 | 0.1–665 | 0.1–216 |

| Area of plots with agricultural activity (ha) | 1360.1 | 2290.5 | 2198.8 |

| Average plot size (ha) | 26.2 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Median plot size (ha) | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Percentage of cultivated area relative to the total agricultural plot area | 3.0 | 19.9 | 33.2 |

| Crop Type | Benahavís | Istán | Ojén | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circa 1956 | 2025 | Circa 1956 | 2025 | Circa 1956 | 2025 | |

| Olive | 141.7 | 4.2 | 19.5 | 86.0 | 259.6 | 93.4 |

| Olive, almond, other dryland crops | 85.3 | 0.9 | 500.9 | 25.4 | 403.5 | 32.0 |

| Olive and almond with irrigated tree crops (Citrus and tropical fruits) | - | 4.8 | - | 5.3 | - | 253.0 |

| Polyculture: vegetable garden and irrigated tree crops (Tropical fruits, citrus, and other fruit trees) | 92.5 | 2.7 | 152.5 | 86.0 | 373.3 | 82.9 |

| Irrigated tree crops: tropical fruits and citrus | - | - | 1.3 | 10.4 | - | 42.2 |

| Tropical fruits | - | 7.3 | - | 1.2 | - | 4.2 |

| Vegetable garden | 41.5 | 2.9 | - | - | - | 5.4 |

| Pasture | 46.4 | - | - | 30.5 | 6.0 | 21.6 |

| Cereal | 329.8 | 8.7 | 18.2 | - | 7.3 | - |

| Silviculture | - | 0.3 | - | 1.1 | 15.6 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro Noblejas, H.; Rodríguez Escudero, Á.D. Traditional Agrarian Landscapes and Climate Resilience in the Rural–Urban Transition Between the Sierra de las Nieves and the Western Costa del Sol (Andalusia, Spain). Geographies 2025, 5, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040078

Castro Noblejas H, Rodríguez Escudero ÁD. Traditional Agrarian Landscapes and Climate Resilience in the Rural–Urban Transition Between the Sierra de las Nieves and the Western Costa del Sol (Andalusia, Spain). Geographies. 2025; 5(4):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040078

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro Noblejas, Hugo, and Álvaro Daniel Rodríguez Escudero. 2025. "Traditional Agrarian Landscapes and Climate Resilience in the Rural–Urban Transition Between the Sierra de las Nieves and the Western Costa del Sol (Andalusia, Spain)" Geographies 5, no. 4: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040078

APA StyleCastro Noblejas, H., & Rodríguez Escudero, Á. D. (2025). Traditional Agrarian Landscapes and Climate Resilience in the Rural–Urban Transition Between the Sierra de las Nieves and the Western Costa del Sol (Andalusia, Spain). Geographies, 5(4), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040078