Abstract

Bangladesh is at the forefront of climate change impacts because of its geographical location, high population density, and constrained socio-economic infrastructure. Our objective is to explore the impacts of climate change on human security components and conflict constellation, and identify adaptation actors through the lens of experts in Bangladesh. We conducted 12 semi-structured qualitative interviews with lead experts using the Problem-centred Interview (PCI) methodology and inductively applied content analysis to analyse the data, complemented with descriptive statistics. Experts see a shift in baseline risk due to the increase in frequency and severity of natural hazards. It exacerbates existing vulnerabilities by declining agricultural productivity, undermining water security and increasing migration. Food, economic, and water security are predominantly impacted, where women and the poor suffer disproportionately. Impacts on urban areas, energy and community security are under-researched. Experts agreed that climate change is a “threat multiplier” and could aggravate political insecurity, leading to conflicts. Individuals and households are primary adaptation actors, followed by governmental and non-governmental organisations. This research contributes to the broader understanding of the complex nexus of climate change impacts, human security, and conflict constellation, complements climate models and provides policy-relevant insights for inclusive, long-term adaptation grounded in local realities in Bangladesh.

1. Introduction

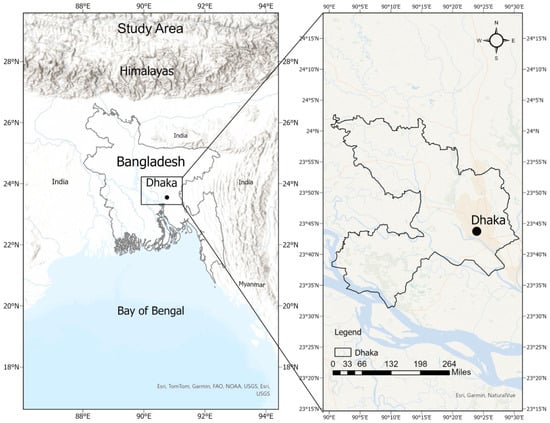

Climate change poses direct and indirect threats to human security through the intensification of physical hazards and socio-political tensions that may lead to societal instability and conflict [1,2]. We chose Bangladesh as our case study area because of its high vulnerability and its extensive experience with natural hazards. Case studies enable detailed examination of the human dimensions of climate change, offering insights that broader analyses may overlook [3]. Bangladesh is a low-lying country nestled between the Himalayas and the Bay of Bengal (Figure 1) [4]. It is often labelled as “ground zero” for climate change, as it is susceptible to rising sea levels, floods, salinity intrusion, cyclones and droughts [5,6]. Changes in temperature, precipitation and seasonal patterns are decreasing crop yields, consequently reducing food availability and compromising community livelihoods [7]. Despite its little contribution to global emissions, the dense population, agricultural reliance, weak governance, restrained infrastructure, and socioeconomic conditions aggravate its vulnerabilities [8,9]. Women, children, and marginalised groups suffer disproportionately because of low adaptive capacity and constrained access to resources [10,11]. Both internal and transboundary environmental migration increases resource competition in destination areas that feeds social unrest [12]. Moreover, climate variability poses numerous health hazards, e.g., heat and salinity-related illnesses, malnutrition and vector-borne disease outbreaks after extreme events, thereby compromising public health [13,14].

Figure 1.

Map of Bangladesh showing its disaster-prone position (left) and location of Dhaka, where the interviews were conducted (right).

Research on climate change in Bangladesh is extensive yet fragmented, and that mostly addresses the physical environment and human security issues separately [15,16]. Ahmed et al. [17] show that biophysical changes (e.g., rising temperatures, sea-level rise, and natural hazards) exacerbate socio-economic burdens on agriculture, health, and livelihoods. Rahaman et al. [18] identified the southwest coastal region as particularly vulnerable and highlighted gender-based violence and disproportionate effects on children and the poor. Recent studies pointed out that displacement, food insecurity, health risks, and socioeconomic instability are key threats to human security [19,20]. Where most studies focus on security components separately, Sultana et al. [21] found in their broad literature review that economic, food, environmental, health, and water security are mostly impacted. However, comprehensive research examining climate change impacts on all human security components through the lens of experts with long-standing experience with multiple stakeholders is largely missing, indicating a significant research gap.

Existing expert interviews on Bangladesh have focused on climate adaptation, instead of impacts [22,23,24]. There has been scholarly interest in climate-induced migration as many experts acknowledge migration as an active adaptation strategy and discuss the complex interplay with environmental changes [25,26]. In their expert evaluation, Sovacool et al. [27] examined climate adaptation projects’ outcomes in coastal areas and found that coastal afforestation projects are effective for livelihood resilience. On the other hand, Rahman et al. [28] report that Bangladesh faces challenges in accessing international climate funds that impede adaptation efforts. Furthermore, the causal linkage between climate change and conflict is often not clearly stated [21], but rather perceived as a catalyst that exacerbates migration and resource scarcity [29,30]. Moreover, existing future climate projections predict changes in physical variables, e.g., substantial increase in minimum and maximum temperatures along with intensified annual precipitation by 2100 [31,32]. While such numerical modelling is essential, experts’ forecasts on social dynamics based on their practical knowledge and human experience remain equally crucial [33].

To address the research gap, 12 semi-structured interviews guided by a problem-centered interview approach were conducted with lead experts in the field. Inductive content analysis was used to detect emerging themes, complemented by descriptive statistics. Expert insights are vital for devising policies that mitigate climate-related risks and protect public welfare. The study also serves as a reference for future comparisons and identifies under-researched areas [34]. Therefore, our specific research objectives are: (a) experts’ perceptions on the role of climate change in the hazard-prone context of Bangladesh; (b) its impacts on various human security components; (c) the disproportionate vulnerabilities of certain population groups; (d) linkages between climate impacts and conflict; and (e) key actors driving adaptation. We focus on internal environmental migration within Bangladesh driven by sudden and slow onset climatic and environmental stressors, e.g., extreme weather events, salinity intrusion, flooding, riverbank erosion, drought [35]. This is to maintain a clear analytical scope, since transboundary migration comprises additional political and legal complexities that go beyond the aims of this research.

2. Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

Human security is a comprehensive and multidimensional concept that protects the well-being, dignity, and rights of individuals and communities [36]. The concept of security in this context has undergone a paradigm shift from a state-centric perspective focusing on safeguarding national sovereignty to a people-centric view emphasising the protection and empowerment of individuals and communities [37]. The idea gained attention in the 1994 Human Development Report by the United Nations Development Programme [38]. It introduced a two-fold idea of human security, emphasising freedom from want and fear. It broadened the concept of security to include seven components: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security.

Since then, the concept has evolved in the scholarly, policy and operational framework. It encompasses security facets that exceed the conventional military or state-oriented standpoint, acknowledging that an individual’s security is inextricably linked with societal, financial, ecological, and governmental circumstances [39]. It considers the interconnectedness and interdependence of various security dimensions and recognises that a person’s security is an aggregate function of multiple components [40]. The 6th assessment report of IPCC defines it in the context of climate change “as a condition that exists when the vital core of human lives is protected, and when people have the freedom and capacity to live with dignity” and identifies three pillars: freedom from fear, freedom from want and freedom to live in dignity [41]. The report specified that climate change has a high potential to undermine human security by threatening livelihoods, culture, and identity, increasing involuntary migration, and challenging a state’s capability to maintain circumstances that ensure human security.

Sultana et al. [21] expanded the human security framework by adding water and energy security to the original seven components and modifying their criteria (Table 1). While water security may overlap with food, health or environmental security, its distinctive role in all life on the planet and indispensable utility needs independent consideration. Climate change intensifies water insecurity by intensifying hydrological extremes, changing precipitation patterns, and disrupting freshwater supply and quality [41]. These changes increase competition for shared water resources and escalate geopolitical tensions, especially in water-stressed areas [42]. Similarly, energy is a requisite part of human history and development and the key to climate change mitigation [43]. It has influenced human life from basic needs to societal stability [44], clearly perceptible in historical and ongoing wars and conflicts [45]. Therefore, we have adopted the extended conceptual framework by recognising the relevance of our study and its importance in formulating policies that address these interlinked challenges.

Table 1.

Criteria for connecting climate change impacts to human security components [21].

2.2. Interviews

According to Von Soest [46], experts are observers of social processes and offer vital insights into inner causal mechanisms found in the field, often missing in academic literature. It helps aggregate disintegrated information and gives an idea of the bigger picture by linking micro and macro-level analysis. While numerous studies in Bangladesh have examined climate change impacts, few have provided comprehensive, expert opinions or addressed conflict linkages. Expert interviews in existing research typically supplement other methods, e.g., interviews, focus group discussions or surveys, revealing a gap in research methodology [47,48,49].

To bridge the gap, we have conducted 12 semi-structured Problem-centred Interviews (PCI) with influential experts in Bangladesh. PCI is a qualitative method utilised to obtain detailed insights and expertise from individuals with specialised knowledge that focuses on complex issues within a defined domain [50]. The interviewer employs open-ended questioning and encourages interviewees to share their insights, experiences, and recommendations to generate rich qualitative data [50]. Effective PCI requires the interviewer’s strong subject knowledge, facilitation skills, and openness to revising their assumptions, which Murray [51] described as a “well-informed traveller”. The first author conducted the interviews and possessed these attributes through relevant academic credentials and practical experience.

Expert respondents were selected based on their experience, institutional stature and contributions in shaping the country’s policies regarding climate adaptation. They have worked closely with multiple crucial stakeholders, e.g., government, vulnerable communities, donor agencies. The initial group of experts (8) were invited based on their published research and external recommendations, followed by further recruitment via snowball sampling [52]. The experts covered a broad range of institutional backgrounds from academia (University of Dhaka, Independent University Bangladesh), think tanks (Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies, Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies, Centre for Participatory Research and Development), NGOs and international development agencies (Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Action Aid International and Global Centre on Adaptation). Table 2 profiles the interviewees by age, gender, education, experience, and professional sector.

Table 2.

Profile of the experts (N/A indicates information that experts were not willing to share).

The interviews were conducted in English from August 2022 to October 2023, in person in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and online using video call technology, each lasting 45–90 min. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it involved anonymous survey data and no personal identifiers were collected. Each interview was conducted and recorded with the respondents’ written consent before participation, ensuring data protection, confidentiality, voluntary participation and responsible research conduct [53].

Guiding questions (Table 3) were shared beforehand to improve the quality. We developed the interview questions deductively from the extended human security framework [21,36,38] and the climate-security literature that shows specific causal pathways relevant to Bangladesh’s deltaic and hazard-prone context [7,15,17,29]. The guiding questions capture experts’ perceptions of climate-induced hazard patterns, impacts on each human security dimension, disproportionate vulnerabilities, conflict constellations, and adaptation actors. The questions, therefore, address our research objectives, reflect the multidimensional nature of human security and incorporate IPCC-identified climate risks in South Asia, e.g., disrupted hydrology, economic loss and large-scale rural–urban migration [41]. Although our research primarily focuses on climate change impacts, we included one question on adaptation actors in Bangladesh, considering urgent concerns about the lack of coordination among various adaptation actors [54]. Previous research shows fragmentation and limited coherence among governmental, non-governmental, and community-level actors in Bangladesh’s adaptation landscape, which can weaken the effectiveness of impact-focused interventions [55,56,57]. Including this question allowed us to situate observed climate impacts within the broader governance context of adaptation responses.

Table 3.

Guiding Questions for the Interview.

2.3. Data Analysis

This study is primarily qualitative in design. The first author conducted the interviews qualitatively and analysed the results using descriptive statistics following the content analysis method [58]. We followed the COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research) checklist to ensure the methodological integrity of the qualitative interview [59] (see Supplementary Data). We used descriptive statistics (e.g., counts of mentions across interviews) to reduce researcher bias and errors by capturing the frequency of specific themes and consistency of expert narratives [60]. Besides, reflexive practices, where researchers consciously reflect on their perspectives for objectivity, were employed throughout data processing to further reduce human biases [61].

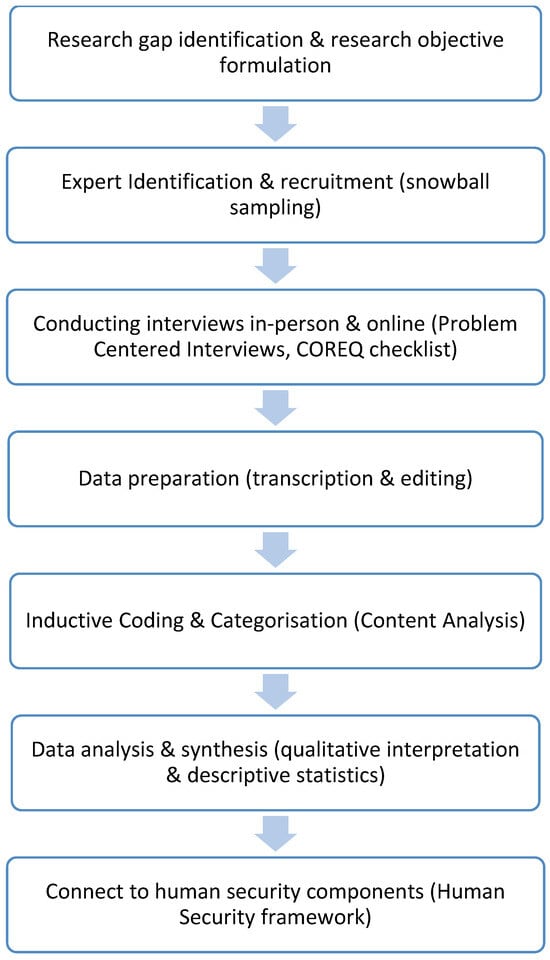

The interviews were transcribed and minimally edited to remove redundancies and interjections common in spoken language [22]. The data was analysed inductively using the content analysis methodology in MAXQDA software (version 24) [62,63], creating a coding scheme from the interview guidelines and the information provided by the respondents and refining it iteratively [64]. Each information was coded once per respondent to avoid duplication. Descriptive statistics were used to describe and summarise the data, analyse frequencies, and compare them among the experts [65,66]. Finally, we connected the impacts to each human security component following the criteria in Table 1. The transcripts and coding scheme of the interviews are published in an online data repository (see Supplementary Data). Figure 2 depicts the stepwise methodological framework in a concise flow chart.

Figure 2.

Step-by-step illustration of the methodology.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Hazards in Bangladesh

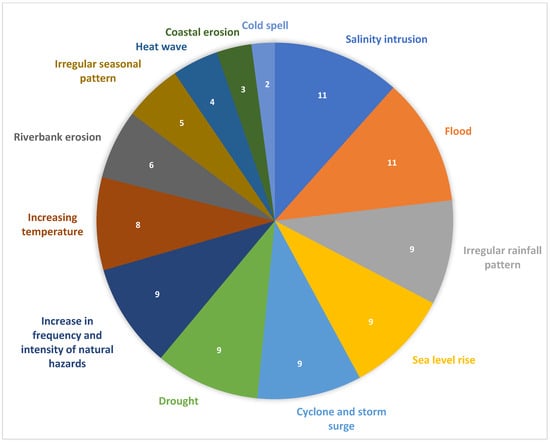

Most of the experts divided the climate hazards into slow onset (e.g., sea level rise, salinity intrusion) and rapid onset or extreme events (e.g., cyclones and storm surges, flash floods) for Bangladesh (Figure 3). Flood and salinity intrusion are natural hazards the most mentioned climate hazards (11 experts). Nine of the 12 experts reported an increasing frequency and intensity of these hazards, as key distinctions between climate-driven and natural hazards. Higher temperatures intensify rainfall, causing more frequent summer floods, while winter water shortages aggravate northern droughts. Due to its geographical position, Bangladesh remains highly prone to natural hazards. As one expert cited:

“Bangladesh is God’s laboratory for natural disasters.”(Interviewee D, lines: 315–316, page: 8)

Figure 3.

Climate hazards affecting Bangladesh, according to the experts.

3.2. Impacts on Human Security

“Entire Bangladesh is impacted this way or that way, directly or indirectly.”(Interviewee J, line: 171, page: 4)

This statement from one of the experts summarises the extent of climate change impacts in Bangladesh. One of our key findings is that all experts perceive climate change mainly through migration and negative consequences for agricultural productivity and water-related issues. Many of the impacts are derivatives of these three critical impacts. Table 4 exhaustively collects all the impacts. Experts unanimously note migration, diminished crop yields and economic losses, with two experts declaring agriculture the hardest-hit sector.

Table 4.

Impacts of climate change and affected human security components.

According to most experts, climate change impacts the hydrological cycle, eventually leading to a loss in crop production and both individual and national revenue generated from it:

“Climate change is the change in hydrology.”(Interviewee D, line: 261, page: 7)

Most emphasise shifts in water availability hindering irrigation and household use, depleting groundwater, and exacerbating salinity, drought, and waterlogging. High salinity in soil, groundwater, and surface water reduces arable land and fish stocks, contributing to declining agricultural productivity and therefore undermining food and economic security. Two experts specifically mentioned the loss of homestead gardens and their negative impact on rural households’ capacity to grow their food. Two-thirds of interviewees report unsafe or insufficient drinking water, including in migrant-receiving areas. One-third of the interviewees see waterlogging (4) as a consequential problem, applicable both in urban areas due to poor drainage systems and in rural areas where water is trapped and eventually changes the landscape, having ramifications for agriculture, mobility and secure housing conditions.

Water-related health issues are mostly through high salinity in surface water sources (8), leading to hypertension (4), skin diseases (4) and reproductive health issues for women (6), e.g., pre-eclampsia in pregnant women. A minority of the experts brought up heat strokes (2), disease outbreaks (3) and disrupted access to healthcare facilities (4). Interestingly, two experts cited worsening air pollution, and one described malnutrition-driven physical and mental stunting in children in climate-stressed regions.

Migration or displacement emerged as a dominant theme (12 experts). Five experts describe seasonal migrations, where particularly men leave salinity, flood, or drought-prone areas to seek work in urban centres. About two-thirds of experts cite accommodation insecurity, given how extreme events damage housing and infrastructure. Seven experts point to negative consequences for ecosystems and biodiversity, particularly the Sundarbans. Political security emerged as a concern that can potentially be exacerbated by large-scale migration into neighbouring countries. Two experts cite impaired voting rights for displaced groups and disrupting the foundational environment for a person to exercise any political rights.

Few experts tie higher urban energy demand to rising temperatures and potential damage to energy infrastructure (e.g., hydropower plants) from floods or sea-level rise. Two experts predicted that the energy needed to pump irrigation water would increase during the summer. One-third of the experts linked climate events to damaged energy infrastructure and prolonged power outages, because of floods or extreme weather events. One expert highlighted reduced firewood and fuel due to salinity intrusion, an indication of salinity’s far-reaching consequences. However, only a minority (3) denied that climate change currently worsens energy security, whereas the majority predicted it as a future risk.

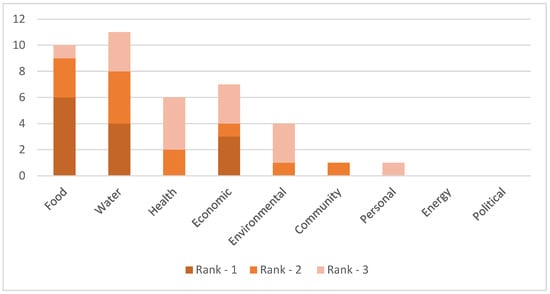

We asked the experts to rank the first three human security components that they perceive to be most vulnerable to climate change impacts (Figure 4). Experts repeatedly identified food, water, economic, health, and environmental security as most at risk. The majority (6) placed food security in the first place, followed by water security (4) and economic security (3). Interestingly, none of the experts identified energy or political security as the top three.

Figure 4.

Experts’ ranking of the first three human security components to be impacted by climate change in Bangladesh.

3.3. Disproportionately Affected Population

Almost all of the experts (11) mentioned women being disproportionately affected, followed by the low-income (10), children (8), disabled (8), indigenous community (7), fishermen (5), elderly (5), farmers (3) and people depending on forest resources (1). Three experts pointed out that landless or marginal farmers suffered more than the financially affluent ones.

3.4. Impacts on Conflicts

While opinions varied on the direct role of climate change on conflicts, experts broadly agreed that it intensifies existing anthropogenic challenges (7), especially in salinity-prone shrimp-farming areas and around migration. One-third cited land grabbing by wealthy farmers or corporations in the southwest and northern “Barind” region. Five experts emphasised competition and conflict over scarce resources, with three linking criminal activities by impoverished migrants to severe economic insecurities. Local political elites often monopolise water distribution in areas of scarcity, increasing the suffering of the poor (2).

3.5. Adaptation Actors

Seven experts mentioned, “Everybody is adapting,” indicating Bangladesh’s longstanding adaptation to climate change. Eleven experts identified the government as an active actor, followed by non-governmental organisations (8) and research institutes (6), especially focusing on agricultural research. Conversely, only a third of the respondents reported the private sector’s engagement in integrating climate change into their businesses, with one expert commenting on their apparent indifference.

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate Hazards in Bangladesh

Experts pointed to increased frequency and intensity as the major distinguishing factor of climate-induced hazards from naturally occurring hazards [17,67], stressing the unreliability of historical patterns for future risk assessments:

“With the advent of human-induced climate change, the hazards are no longer natural anymore… The past is no longer reliable for the future. The future is going to be very different.”(Interviewee B, lines: 24–28, page: 1)

Experts further identified changing rainfall patterns, sea-level rise, salinity intrusion, and rising temperatures as distinctive characteristics of climate hazards, supported by literature [15,17]. Rimi et al. [68] demonstrated that the likelihood of a 1 in 100-year rainfall event has increased considerably compared to pre-industrial times, projected to increase even further under 1.5 and 2.0 °C scenarios. While certain research attributes landslides to heavy rainfall caused by climate change, experts have not established this connection [69,70]. One expert strongly argued that riverbank erosion and landslides are caused by anthropogenic mismanagement (e.g., illegal hill cutting and inefficient dredging). Since Bangladesh is an active delta, sediment management through regular dredging and tidal river management remains crucial [71]. However, future research could investigate the effects of climate hazards on landslides and riverbank erosion and their interconnections with anthropogenic factors.

4.2. Impacts on Human Security

Our study demonstrates that climate change impacts on human and environmental systems are closely interconnected. Migration, decreased agricultural productivity, and water scarcity are the key impacts and many subsequent impacts are derived from these. Bangladesh is an active delta between the Himalayan Mountain ranges and the Bay of Bengal, traversed by numerous rivers and tributaries. Historically, floods essentially enhanced soil fertility with sediment deposits for crop cultivation. Climate change has altered the timing and amount of precipitation, limiting the positive effects of floods on agricultural productivity. All experts identified decreased crop yield and economic loss [72,73], with two experts identifying that agriculture is hit the hardest by anthropogenic climate change in Bangladesh [7,17]. Because the economy relies heavily on climate-sensitive agriculture, our results confirm the IPCC AR5 projection that climate change threatens human security by undermining livelihoods [74]. Catastrophic weather events damage infrastructure, e.g., roads, embankments and irrigation systems, which reduces agricultural productivity and impairs GDP. Moreover, five experts mentioned the ripple effect of economic repercussions on GDP and the national economy could potentially result in political and social unrest [75]. This consensus among researchers emphasises the centrality of adverse impacts on agriculture and, subsequently, food and economic security.

The disruption in the hydrological cycle and resulting water security issues stand out as critical issues for household consumption (e.g., drinking water) and irrigation [17]. Water availability can be insufficient or excessive, and often arises at the wrong time or with unsuitable quality, as summarised well by two-thirds of the experts:

“It’s an issue of too much water, too little water, wrong type of water and wrong time of water.”(Interviewee I, lines: 104–105, page: 3)

Salinity intrusion in southwestern Bangladesh is a multifactorial phenomenon that is exacerbated by the backwater effect of sea-level rise [49]. The severity can be felt when one expert mentioned that when he was about to visit a family, he was asked to bring safe drinking water instead of sweets as gifts. However, anthropogenic factors play a big role, e.g., a lack of freshwater due to transboundary upstream river dam operations, as one expert explains:

“…Climate change is a trigger, it is one of the drivers, not the only driver.”(Interviewee K, line: 88, page: 3)

To adapt to this situation, people change their occupations and diversify their income, which is well documented in the literature [57,76]. However, a lack of transferable skills often constrains them, keeping them trapped in a cycle of poverty.

Climate change exacerbates health vulnerabilities by increasing exposure to salinity and water scarcity, weakening nutritional status, and intensifying infectious diseases. According to one expert, the sudden overnight losses of livelihood following extreme events have even led to suicide among Indigenous farmers, reflecting the psychological toll of climate change [77,78]. An expert highlighted the prevalence of developmentally stunted children and mentally imbalanced individuals in climate-stressed regions, attributing these outcomes to malnutrition and water shortages. These findings align with broader concerns about climate-induced health insecurities in Bangladesh [79]. Interestingly, two experts also cite deteriorating air quality during cold spells, which is rarely discussed in contemporary research. Future research could therefore investigate the impacts on health, especially mental health, more closely.

Cities operate on different rhythms and structures than rural areas, resulting in distinct climate impacts and adaptation mechanisms. Due to the vulnerability of agriculture to climatic variability and its economic significance, most research focuses on rural impacts. But since climate change knows no boundaries, urban hubs are not immune to climate shocks [80]. Bangladesh is a centralised country, and most of its economic activity is focused in heavily populated urban centres. Our research identifies that urban impacts are overshadowed by studies on rural locations, presenting the under-emphasis on urban climate concerns.

Seven experts stated that climate hazards damage Bangladesh’s biodiversity and ecosystems [81]. Three experts directly pointed out the Sundarbans mangrove forest’s decreasing biodiversity because of uncontrolled salinity [82]. With its role as a cyclone buffer and provider of vital ecosystem services, the Sundarbans’ deterioration means far-reaching environmental security threats [83,84].

Bangladesh struggles with ensuring a consistent energy supply, yet research on the consequences of climate change on energy security is insufficient. Two experts mentioned a surge in urban energy demands caused by increased temperatures and heat waves [85]. Although some experts questioned the connections between climate change and energy security, the majority considered it a critical future threat. A critical question is whether the energy landscape is minimally impacted by climate change or if there is a significant research gap. Provided the economically constrained environment in Bangladesh, priorities are given to water, food and livelihood. Besides, the adaptive capacity of Bangladeshi people is relatively high [6,86]. For example, human-powered vehicles, e.g., “rickshaws”, and battery-run three-wheelers, meet substantial portions of mobility needs despite a heavy reliance on fossil fuels for transport [87]. Regular power outages are common, especially in rural areas, so people must find alternative ways to cope with the situation. Such adaptation shows broader acceptance of energy insecurity as a deferred concern.

Displacement or migration was agreed among all experts to be a significant climate change impact, consistent with the prediction of IPCC AR5 [74]. Experts acknowledge that both temporary and permanent rural-urban migration contribute to additional pressure on densely populated and economically struggling cities [30,88]. Migrants suffer from inadequate sanitation and insecure housing in slums [89], along with social capital loss and limited access to education [90]. Stojanov et al. [22] reported a similar mixed pattern of temporary and permanent migration due to environmental stressors in their expert interviews. One expert even cited the economic migration of Bangladeshi workers to the Middle East as being more prevalent in climate-stressed regions. All experts agree that migration massively endangers economic, food and health security. While political security was seldom discussed, two experts cautioned that large-scale migration might limit political rights and possibly lead to broader civil unrest. Experts perceive the existing climate change scenario in Bangladesh as a series of cascading effects, where the climate future in a business-as-usual scenario is most likely to worsen every dimension of human security.

4.3. Disproportionately Affected Population

Our findings align with existing literature that climate change affects certain demographic groups disproportionately, where women are documented as the most vulnerable [7,91,92]. Farmers, fishermen, and indigenous communities are especially vulnerable because of their economic dependence on farming, which is severely affected by climate change [93]. Huq et al. [94] explained that marginal or landless farmers suffer more than affluent farmers, an observation mentioned by the experts as well. Comparative studies could empirically investigate such disparities among marginalised and richer farmers, assessing the economic impacts and the efficiency of the resilience mechanisms. Policy intervention should design social protection initiatives and livelihood diversification programs specifically for marginalised groups to develop resilience against climate risks.

Women’s distinct vulnerabilities are compounded by sociocultural norms that limit access to education, resources, and decision-making authority [10]. Bangladeshi society is primarily patriarchal, where men play the role of guardians for women. The migration of male family members exposes women to further insecure conditions [95]. Their reproductive health is negatively impaired by exposure to intolerable salinity levels in water, e.g., pre-eclampsia during pregnancy [76,96]. Some experts have highlighted the particular vulnerability of adolescent girls. In drought-prone “Barind” and salinity-affected southwestern areas, they have to walk long distances for safe water, increasing the risk of sexual harassment [97]. Women’s reduced food consumption to ensure other family members have enough, and higher school dropout rates, reflect wider identity-based risks to community security. However, the lack of research on this topic raises similar concerns to energy security. It remains unclear whether this discrepancy is due to a genuine absence of evidence or a lack of research, which could be addressed in future studies. In-depth intersectional analyses are needed to better understand how overlapping identities, e.g., gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, compound vulnerability and shape adaptive strategies. Longitudinal studies are necessary to investigate the long-term health effects of salinity exposure, especially concerning reproductive and psychosocial disorders. Adaptation policies need to include gender-mainstreaming measures, e.g., economic empowerment, capacity building, and specialised healthcare services for women.

4.4. Impacts on Conflicts

Climate change is increasingly being considered a “threat multiplier” [98,99], which is unanimously agreed upon by the experts. It exacerbates existing socioeconomic vulnerabilities, inequalities, and socio-political instability by undermining food and economic security for agricultural-dependent communities, e.g., by increasing resource competition and migration [1]. Although experts differ on the direct role of climate change in the conflict in Bangladesh, they agree that it aggravates existing challenges and competition over scarce resources, therefore indirectly creating socio-political tension, especially regarding shrimp cultivation in salinity-prone southern areas and migration [100].

One-third of the experts mentioned land grabbing by influential farmers or corporations as a central issue of concern. Salinity intrusion in the south has encouraged significant land-use change, with most farmers switching to shrimp and crab aquaculture from crop cultivation. Similar issues are observed in the northern “Barind” region, where water scarcity forced farmers to convert paddy fields to mango orchards, leading to more disputes over scarce water resources and leaving smallholder farmers in a vicious cycle of poverty [101]. Tensions are aggravated as a result of inequalities and corruption in access to scarce resources, thus further increasing gaps between rich and poor [102]. Corruption and mismanagement are also reported in climate adaptation projects and emergency relief distribution, where political actors seek to control resources at the cost of intended beneficiaries. The majority of experts believe that climate change is not currently leading to conflicts but has the potential to trigger violent conflict and political instability, predominantly in contexts of internal and transboundary migration [30]. Such risks have the potential to escalate when ongoing crises, e.g., extreme events or inflation, exceed the adaptive capacity of individuals [98]. As Interviewee F stated:

“We all know that hungry people are angry people, so they could create political instability within the country.”(Interviewee F, lines: 118–119, page: 3)

Besides, underprivileged migrants in host regions are reported to engage in criminal activities due to severe economic hardships (Islam, 2023). Poor people in the Sundarbans region who depend on its ecosystem services are reported to be susceptible to illegal activities (e.g., piracy) or being recruited by extremist groups, thereby threatening political security [30,103]. One expert further mentioned the prevalence of domestic violence in climate-stressed regions as a result of livelihood insecurities [95]. Despite these concerns, Bangladeshi individuals have a high adaptive capacity that prevents such escalation from turning into violent conflict:

“Bangladesh has the highest adaptive capacity of any country in the world.”(Interviewee B, line: 171, page: 4)

Moreover, one expert gave an example of cooperation, where displaced communities stayed together and successfully negotiated with political elites. Besides, migration may facilitate economic resilience and adaptive capacity in destination areas if managed properly [104]. Some experts condemned the tendency to blame climate change for disruptions that primarily stem from anthropogenic factors and held poor policy and governance failure responsible [9,105]. It leaves less room to exercise one’s agency to find solutions, as one expert passionately cited:

“If I don’t have a job, is this climate change? The answer is no, the population is high, and there isn’t sufficient employment in the country… There is no point in only attacking them (Western countries). We must build our own capacity; we must build our own response mechanism.”(Interviewee D, lines: 220–221, 487–489, page: 6, 12)

Future research could examine land-use conflicts resulting from climate-driven changes with particular attention to governance structures and power relations that influence resource distribution. Additionally, how economic vulnerability influences gender-based violence in climate-stressed areas and their causal linkages could be explored. Policy recommendations include social protection, capacity building and livelihood diversification initiatives to reduce economic vulnerability among marginalised communities.

4.5. Adaptation Actors

Climate change adaptation has become an integral aspect of daily life in Bangladesh, often occurring implicitly within communities, as reflected by experts noting it as an organic, decades-long process. The Government of Bangladesh and NGOs are increasingly mainstreaming adaptation measures, which is reflected in policy documents, e.g., five-year plan and Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan, whereas research institutes focus more on agriculture-related research [106]. However, experts emphasised insufficient coordination between formal and informal institutions [56]. On the contrary, the private sector is relatively reluctant toward proactive environmental engagement. As a developing nation, Bangladesh prioritises economic growth, aligning with the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis [107,108]. EKC hypothesises that environmental degradation escalates with industrial growth but then declines once a certain income threshold is surpassed, as cleaner technologies and stricter environmental regulations become more affordable [109]. Studies confirm that Bangladesh is in the initial phase of environmental degradation, predicted to worsen with increasing climate change impacts [110]. It could explain the reluctance of the private sector, as their focus is on economic development, even at the cost of the environment. Petzold et al. [54] showed in their global assessment that individuals or households are predominantly involved in adaptation implementation in the south and government organisations in planning, with a significant lack of engagement from the private sector, complementing our findings for Bangladesh.

Experts characterised current adaptation efforts as reactive, localised, short-sighted, and risk-driven, emphasising the need for preventive, long-term, comprehensive and vulnerability-based national strategies. Future research could conduct comparative analyses assessing the effectiveness of coordinated versus uncoordinated climate adaptation strategies between formal and informal institutions. The reasons behind the private sector’s limited engagement could be explored to harmonise economic growth with sustainable development objectives. Policies should focus on long-term adaptation plans that prioritise vulnerability reduction rather than short-term risk management guided by insights from successful local adaptation models. Simultaneously, governments should encourage private-sector involvement through economic incentives, regulatory frameworks, and awareness campaigns.

4.6. Limitations

The limitations of our research are the relatively small sample size and the reliance on a single researcher for interview coding, which risks potential bias [111]. However, focusing on in-depth interviews with leading experts and adapting reflexive measures for data analysis countered the limitations [61]. Besides, we employed qualitative methods to assign specific climate impacts to human security components instead of other existing quantitative approaches, e.g., human security index [112,113]. Nevertheless, we introduced descriptive statistics for a comprehensive overview, and detailed quantitative analysis goes beyond the scope of our research [66]. Adhering to the COREQ checklist [59] and adopting Mayring [62] and Kuckartz et al. [63] for the content analysis, supplemented by descriptive statistics, enhances the results and our interpretation. While comparative intra- or inter-regional analyses could show additional contrasts, it is outside the scope of a problem-centred interview approach, as it prioritises in-depth contextual understanding. Nonetheless, the human security framework provides a transferable analytical structure that can support future comparative research in countries with similar socio-ecological conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study enhances our understanding of the implications of climate change on human security components and conflict constellations enunciated by leading experts in Bangladesh. We found that anthropogenic climate change distinctly alters the frequency and intensity of natural hazards, making it distinguishable from historical trends. Declining agricultural productivity, water scarcity and migration are the key pathways through which climate change affects human security components. Food, water and economic security as the first three components to be impacted by climatic variability, followed by health and environmental security. Experts agree that climate change acts as a “threat multiplier” and significantly amplifies existing vulnerabilities, potentially leading to political unrest and conflict.

Experts concluded that reduced agricultural productivity considerably hinders economic stability, cascading through GDP losses and potentially leading to socio-political tensions. Water security emerges as a crucial concern, with irregular availability and deteriorating quality exacerbating household vulnerabilities and agricultural practices. In addition, salinity intrusion significantly compromises freshwater availability, which eventually contributes to land-use change, reduced agricultural productivity, and worsening health issues, especially for women. Marginalised groups, e.g., women and low-income populations, bear a disproportionate burden due to their unique vulnerabilities. Rural-urban migration is a significant consequence that increases competition for resources and further strains already overburdened urban infrastructure, thus creating precarious living conditions. Although experts did not make direct connections between climate change and conflict, it is recognised as a potential risk factor that can increase social and political instability at both domestic and international levels. Nevertheless, the considerable adaptive capacity of Bangladeshi society frequently neutralises such tensions, demonstrating significant resilience within structural constraints. Adaptation occurs organically among individuals and households, assisted by government and non-governmental organisations with limited coordination. The minimal role of the private sector highlights an urgent need for integrated, long-term adaptation measures focused on vulnerability reduction rather than short-term reactive measures.

A key theoretical implication of our research is the human security framework, which gives a structured lens through which public managers can assess and address climate-related vulnerabilities across multiple dimensions. Its alignment with established UN approaches strongly supports its applicability in policy and operational contexts. In addition, this study uncovers critical knowledge gaps on climate change impacts in urban areas and on energy and community security components, which could be addressed in future research. The conditions under which climate-induced migration promotes cooperation instead of conflict need further research, focusing on successful examples of community-led negotiations and integration in host areas. As agriculture is the hardest-hit sector, government and public managers should invest in salt-tolerant crops, crop diversification, extension services, and resilient irrigation infrastructure, focusing on local adaptive practices. Considering less climate mainstreaming in urban areas, public managers should integrate climate adaptation into municipal planning and improve public health measures for migrant-receiving areas. Healthcare infrastructure should be strengthened, for example, by mobile healthcare services and improved access to safe water and nutrition, especially since women’s health is critical in salinity and drought-prone areas. Most importantly, climate adaptation policies need to be participatory, gender and conflict-sensitive, addressing underlying socioeconomic inequalities and corruption.

The vast knowledge and experience of experts have given us valuable insight into the present status and significant projections of the climate future of Bangladesh. Our research can significantly complement the climate model outcomes, as model simulations cannot capture the subtleties of human experience. This study serves as a vital reference for future research and development of effective policies and strategies, thus apprising the transition towards a more resilient and equitable climate future for Bangladesh.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geographies5040077/s1. Files S1: Coding Scheme; Files S2: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ): 32-item checklist.

Author Contributions

F.S., Conceptualisation, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Visualisation, Formal Analysis, Project Administration, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing. J.S., Conceptualisation, Supervision, and Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2037 “CLICCS–Climate, Climatic Change, and Society” Project Number: 390683824.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it involved anonymous survey data and no personal identifiers were collected. Each interview was conducted and recorded with the respondents’ written consent before participation, ensuring data protection, confidentiality, voluntary participation and responsible research conduct.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The published transcripts and coding scheme of the interviews can be found in the data repository of the Center for Sustainable Research Data Management (ZFDM), University of Hamburg, under: https://www.fdr.uni-hamburg.de/record/14338; https://www.fdr.uni-hamburg.de/record/14393 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (Version 4o and 5.1) by OpenAI solely for grammar correction and language editing. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Von Uexkull, N.; Buhaug, H. Security implications of climate change: A decade of scientific progress. J. Peace Res. 2021, 58, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffran, J. Climate Change: Human Security Between Conflict and Cooperation. In Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 2, pp. 807–819. [Google Scholar]

- Barkmann, T.; Siebert, R.; Lange, A. Land-use experts’ perception of regional climate change: An empirical analysis from the North German Plain. Clim. Change 2017, 144, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Islam, M.S. Climate change and its impact on sustainable development in Bangladesh. Int. J. Econ. Energy Environ. 2017, 2, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dastagir, M.R. Modeling recent climate change induced extreme events in Bangladesh: A review. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2015, 7, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, S. Climate change and Bangladesh. Science 2001, 294, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikder, R.; Xiaoying, J. Climate change impact and agriculture of Bangladesh. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 4, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafuzzaman, M. Local Context of Climate Change Adaptation in the South-Western Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewly, H.J.; Nadiruzzaman, M.; Warner, J. Causal connections between climate change and disaster: The politics of ‘victimhood’ framing and blaming. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2023, 45, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.T.; Islam, M.M.; Rana, M.S. Climate Change and Environmental Security in Bangladesh: A Gender Perspective. J. Knowl. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md, A.; Gomes, C.; Dias, J.M.; Cerdà, A. Exploring gender and climate change nexus, and empowering women in the South Western Coastal Region of Bangladesh for adaptation and mitigation. Climate 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, R. Climate-Induced Migration: Impacts on Social Structures and Justice in Bangladesh. S. Asia Res. 2019, 39, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Ahmad, S.; Mahmud, A.S.; Hassan-uz-Zaman, M.; Nahian, M.A.; Ahmed, A.; Nahar, Q.; Streatfield, P.K. Health consequences of climate change in Bangladesh: An overview of the evidence, knowledge gaps and challenges. WIREs Clim. Change 2019, 10, e601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasib, E.; Chathoth, P. Health impact of climate change in Bangladesh: A summary. Curr. Urban Stud. 2016, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Islam, M.N.; Barkat Ali, K.M.; Kawser, U. Climate Change Impacts on Human Health Problems and Adaptation Strategies in the Southeastern Coastal Belt in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh II: Climate Change Impacts, Mitigation and Adaptation in Developing Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 103–136. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hossain, M.; Majumder, A. Impact of climate change on agricultural production and food security: A review on coastal regions of Bangladesh. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innov. Technol. IJARIT 2018, 8, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, M.A. Spatial overview of climate change impacts in Bangladesh: A systematic review. Clim. Dev. 2023, 15, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.A.; Saba, Z.; Quader, M.A. Climate change and social protection: Threats for contemporary human security issues in Bangladesh. S. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 4, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Altaf, L. Climate Change and Human Security in South Asia: Case Study of Bangladesh. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.M.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Ahsan, R.; Afroz, T.; Ahmed, S. Climate change, migration and human rights in Bangladesh: Perspectives on governance. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2019, 60, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F.; Petzold, J.; John, S.; Muehlberger, V.; Scheffran, J. Systematic Mapping of Climate Change Impacts on Human Security in Bangladesh. Climate 2024, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, R.; Kelman, I.; Ullah, A.K.M.A.; Duží, B.; Procházka, D.; Blahůtová, K.K. Local Expert Perceptions of Migration as a Climate Change Adaptation in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Sabrina, H.; Zzaman, R.U.; Islam, S.L.U. Green building aspects in Bangladesh: A study based on experts opinion regarding climate change. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 9260–9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Sarker, P.K.; Hirono, R.; Giessen, L. Implications of Development Cooperation and State Bureaucracy on Climate Change Adaptation Policy in Bangladesh. Climate 2020, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, J.M. Climate change and migration in Bangladesh: Empirically derived lessons and opportunities for policy makers and practitioners. In Limits to Climate Change Adaptation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 59–105. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanov, R.; Boas, I.; Kelman, I.; Duzí, B. Local expert experiences and perceptions of environmentally induced migration from Bangladesh to India. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2017, 58, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; D’Agostino, A.L.; Meenawat, H.; Rawlani, A. Expert views of climate change adaptation in least developed Asia. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 97, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Ahmad, M.M. Perception of local experts about accessibility to international climate funds: Case of Bangladesh. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, K.; Kinney, P.L. Exploring the Climate Change, Migration and Conflict Nexus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malji, A.; Obana, L.; Hopkins, C. When Home Disappears: South Asia and the Growing Risk of Climate Conflict. Terror. Political Violence 2022, 34, 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jihan, M.A.T.; Popy, S.; Kayes, S.; Rasul, G.; Maowa, A.S.; Rahman, M.M. Climate change scenario in Bangladesh: Historical data analysis and future projection based on CMIP6 model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, H.M.T.; Islam, A.M.T.; Shahid, S.; Alam, G.M.M.; Biswas, J.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Roy, D.K.; Kamruzzaman, M. Future precipitation projection in Bangladesh using SimCLIM climate model: A multi-model ensemble approach. Int. J. Clim. 2022, 42, 6716–6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, A.N.; Ichino, N. Using Qualitative Information to Improve Causal Inference. Am. J. Political Sci. 2015, 59, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Evely, A.C.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Kruijsen, J.; White, P.C.L.; Newsham, A.; Jin, L.X.; Cortazzi, M.; Phillipson, J.; et al. Knowledge exchange: A review and research agenda for environmental management. Environ. Conserv. 2013, 40, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, O.Q.; Suza, M.; Savelli, A.; Nelson, K.M. Exploring the relationship between climate change events and migration decisions: Evidence from a choice experiment in Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 113, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Human Security. Human Security Now; Commission on Human Security: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, R. Human security: Paradigm shift or hot air? Int. Secur. 2001, 26, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 1994: New Dimensions of Human Security; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J.; Matthew, R.A.; O’Brien, K. Global environmental change and human security. In Globalization and Environmental Challenges: Reconceptualizing Security in the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffran, J.; Remling, E. The social dimensions of human security under a changing climate. In Handbook on Climate Change and Human Security; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 137–163. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Glossary. In Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Möller, V.v.D., Matthews, J.B.R., Méndez, C., Semenov, S., Fuglestvedt, J.S., Reisinger, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2897–2930. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, A.T. Water and human security. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2001, 118, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S.I.; Jollands, N. Human security and energy security: A sustainable energy system as a public good. In International Handbook of Energy Security; Elgar Original Reference; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Brown, M.A. Competing Dimensions of Energy Security: An International Perspective. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffran, J. Limits to the Anthropocene: Geopolitical conflict or cooperative governance? Front. Political Sci. 2023, 5, 1190610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Soest, C. Why do we speak to experts? Reviving the strength of the expert interview method. Perspect. Politics 2023, 21, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanjeela, M. Understanding the struggles of Bangladeshi women in coping with climate change through a gender analysis. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2023, 27, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Ali, S. Exploring Local Perceptions of Climate Change Impact and Adaptation in Rural Bangladesh; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 1322. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.A.; Shelia, V.; Ludwig, F.; de Bruyn, L.L.; Rahman, M.H.U.; Hoogenboom, G. Bringing farmers’ perceptions into science and policy: Understanding salinity tolerance of rice in southwestern Bangladesh under climate change. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döringer, S. ‘The problem-centred expert interview’. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.C. Book Review: The Problem-Centred Interview; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bott, L.-M. Linking migration and adaptation to climate change. How stakeholder perceptions influence adaptation processes in Pakistan. Int. Asienforum. 2016, 47, 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, M.; Hay, I. Research Ethics for Social Scientists; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Petzold, J.; Hawxwell, T.; Jantke, K.; Gresse, E.G.; Mirbach, C.; Ajibade, I.; Bhadwal, S.; Bowen, K.; Fischer, A.P.; Joe, E.T.; et al. A global assessment of actors and their roles in climate change adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenack, K.; Stecker, R.; Reckien, D.; Hoffmann, E. Adaptation to climate change in the transport sector: A review of actions and actors. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2012, 17, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Nursey-Bray, M. Adaptation to climate change in agriculture in Bangladesh: The role of formal institutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 200, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaporte, I.; Maurel, M. Adaptation to climate change in Bangladesh. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskat, M.; Blackman, D.A.; Muskat, B. Mixed methods: Combining expert interviews, cross-impact analysis and scenario development. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2012, 10, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Corlett, S.; Mavin, S. Reflexivity and researcher positionality. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2018; pp. 377–399. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. In Approaches to Qualitative Research in Mathematics Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Fakis, A.; Hilliam, R.; Stoneley, H.; Townend, M. Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Information From Interviews: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2014, 8, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey, R.W. Descriptive statistics for summarising data. In Illustrating Statistical Procedures: Finding Meaning in Quantitative Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 61–139. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, S.; Huq, M.; Khan, Z.H.; Ahmed, M.M.Z.; Mukherjee, N.; Khan, M.F.; Pandey, K. Cyclones in a changing climate: The case of Bangladesh. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimi, R.H.; Haustein, K.; Barbour, E.J.; Sparrow, S.N.; Li, S.; Wallom, D.C.; Allen, M.R. Risks of seasonal extreme rainfall events in Bangladesh under 1.5 and 2.0 °C warmer worlds—How anthropogenic aerosols change the story. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 5737–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, I.; Joshi, A.; Alam, M.; Jayasinghe, S.; Laila, N. Climate Change Induced Landslide Susceptibility Assessment—For Aiding Climate Resilient Planning for Road Infrastructure: A Case Study in Rangamati District, Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 9th AUN/SEED—Net Regional Conference on Natural Disaster, Online, 15 December 2021–16 December 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; p. 012010. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, N. Analysis of landslide-induced fatalities and injuries in Bangladesh: 2000–2018. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1737402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.N. Deltaic floodplains development and wetland ecosystems management in the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna Rivers Delta in Bangladesh. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 2, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, O.; Mahzab, M.; Raihan, S.; Islam, N. An Economy-Wide Analysis of Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture and Food Security in Bangladesh. Clim. Change Econ. 2015, 6, 1550003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Rahman, M.A. Impacts of climate change on crop production in Bangladesh: A review. J. Agric. Crops 2019, 5, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Pulhin, J.M.; Barnett, J.; Dabelko, G.D.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; Levy, M.; Oswald Spring, U.; Vogel, C.H. Human Security; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, S.S.; Delin, H.; Ma, M.Y. Aftermath of climate change on Bangladesh economy: An analysis of the dynamic computable general equilibrium model. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 2597–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, M.; Uddin, M.N.; Hasan, M.M.; Wang, X.J.; Shiru, M.S.; Shahid, S. Prioritization of sectoral adaptation strategies and practices: A case study for Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorunnahar, M.; Mily, M.A.; Khatun, L.; Rahman, M.A.; Pranto, R.A.; Uddin, K.S. How is Bangladesh Growing More Susceptible to Infectious Disease Epidemics as a Result of Climate Change? A Systematic Review. Asian J. Res. Infect. Dis. 2023, 12, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahsin, N.; Gąsior, W.Z.; Olszewska-Guizzo, A. Climate Change and Mental Health in Bangladesh: A Cultural Variability Perspective. In Climate Change and Health Hazards: Addressing Hazards to Human and Environmental Health from a Changing Climate; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, M.P. Food and health security impact of climate change in Bangladesh: A review. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 3484–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.; Arfanuzzaman, M. The effects of human capital and social factors on the household income of Bangladesh: An econometric analysis. J. Econ. Dev. 2020, 45, 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Reza, M.I.; Rahman, S.; Kayes, I. Climate change and its impacts on the livelihoods of the vulnerable people in the southwestern coastal zone in Bangladesh. In Climate Change and the Sustainable Use of Water Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, S.; Sobhan, I.; Wheeler, D. The impact of climate change and aquatic salinization on mangrove species in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Ambio 2017, 46, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Nobi, M.N.; Roskaft, E.; Chivers, D.J.; Suza, M. Value of the storm-protection function of sundarban mangroves in Bangladesh. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 13, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titumir, R.A.M.; Shah Paran, M. Ecosystem services and well-being in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh: A multiple evidence base trajectory. In Assessing, Mapping and Modelling of Mangrove Ecosystem Services in the Asia–Pacific Region; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 263–281. [Google Scholar]

- Shourav, M.S.A.; Shahid, S.; Singh, B.; Mohsenipour, M.; Chung, E.S.; Wang, X.J. Potential Impact of Climate Change on Residential Energy Consumption in Dhaka City. Environ. Model. Assess. 2018, 23, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, R.; Towfiqul Islam, A.R.M.; Shill, B.K.; Monirul Alam, G.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Morshadul Hasan, M.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Shouse, R.C. Nexus between vulnerability and adaptive capacity of drought-prone rural households in northern Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.A.; Hasan, M.Z.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Khan, M.Z.R.; Ahsan Habib, M. Affordable Electric Three-Wheeler in Bangladesh: Prospects, Challenges, and Sustainable Solutions. Sustainability 2022, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.M.P.; Ilina, I.N. Climate change and migration impacts on cities: Lessons from Bangladesh. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Kniveton, D.; Cannon, T. Trapped in the prison of the mind: Notions of climate-induced (im)mobility decision-making and wellbeing from an urban informal settlement in Bangladesh. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Hasan, M.K.; Hasan, M.R.; Younos, T.B. Climate change impacts and adaptations on health of Internally Displaced People (IDP): An exploratory study on coastal areas of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggers, A. Climate change is not gender neutral: Gender inequality, rights and vulnerabilities in Bangladesh. In Confronting Climate Change in Bangladesh: Policy Strategies for Adaptation and Resilience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, S.S.; Cui, Y.W.; Delin, H.; Zhang, X.Y. The economic influence of climate change on Bangladesh agriculture: Application of a dynamic computable general equilibrium model. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2023, 15, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.N.Q.; Haq, S.M.A. Indigenous people’s perceptions about climate change, forest resource management, and coping strategies: A comparative study in Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 679–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, N.; Hugé, J.; Boon, E.; Gain, A.K. Climate Change Impacts in Agricultural Communities in Rural Areas of Coastal Bangladesh: A Tale of Many Stories. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8437–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Eklund, E. Climate Change Impacts in Coastal Bangladesh: Migration, Gender and Environmental Injustice. Asian Aff. 2021, 52, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.E.; Scheelbeek, P.F.; Shilpi, A.B.; Chan, Q.; Mojumder, S.K.; Rahman, A.; Haines, A.; Vineis, P. Salinity in drinking water and the risk of (pre)eclampsia and gestational hypertension in coastal Bangladesh: A case-control study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Nasreen, M.; Hossain, F. Gender Culture in Water Security of Coastal Bangladesh. In Coastal Disaster Risk Management in Bangladesh: Vulnerability and Resilience; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffran, J.; Ide, T.; Schilling, J. Violent climate or climate of violence? Concepts and relations with focus on Kenya and Sudan. In Climate Change and Genocide; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mach, K.J.; Kraan, C.M.; Adger, W.N.; Buhaug, H.; Burke, M.; Fearon, J.D.; Field, C.B.; Hendrix, C.S.; Maystadt, J.F.; O’Loughlin, J.; et al. Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict. Nature 2019, 571, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. Climate change and lethal violence: A global analysis. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2025, 17, 216–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Bamboo Beating Bandits: Conflict, Inequality, and Vulnerability in the Political Ecology of Climate Change Adaptation in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2018, 102, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, P.; Thompson, P.M. Adaptation or conflict? Responses to climate change in water management in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 78, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Huq, M.; Mustafa, M.G.; Sobhan, M.I.; Wheeler, D. Impact of Climate Change and Aquatic Salinization on Fish Habitats and Poor Communities in Southwest Coastal Bangladesh and Bangladesh Sundarbans; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Kang, Y.H.; Billah, M.; Siddiqui, T.; Black, R.; Kniveton, D. Climate-influenced migration in Bangladesh: The need for a policy realignment. Dev. Policy Rev. 2017, 35, O357–O379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiruzzaman, M.; Scheffran, J.; Shewly, H.J.; Kley, S. Conflict-Sensitive Climate Change Adaptation: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N. Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in least developed countries in South and Southeast Asia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2013, 18, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R. Environmental kuznets curve and causal links between environmental degradation and selected socioeconomic indicators in Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5426–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Karim, A.A.M.E.; Ahmed, Z.; Hakan, A. Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) for Bangladesh: Evidence from fully modified OLS approach. JOEEP J. Emerg. Econ. Policy 2021, 6, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic-Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.; Alam, R.; Ansarin, A. The environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis for Bangladesh: The importance of natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, and hydropower consumption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 17208–17227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.D.; McAllister, C.; Grinnell, L.D.; Walters, K.G.; Appunn, F. Applying Constant Comparative Method with Multiple Investigators and Inter-Coder Reliability. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, D.A. The Human Security Index: An Update and a New Release; Document Report Version 2.0; Homeland Security Investigations (HSI): Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Carolan, M. The food and human security index: Rethinking food security and ‘growth’. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2012, 19, 176–200. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).