1. Introduction

In recent decades, the Alps have undergone profound transformations in their socio-ecological systems, spatial configurations, and cultural identities. While historically shaped by agricultural, pastoral, and silvicultural practices, these landscapes are increasingly affected by structural trends such as demographic decline, climate change, land abandonment, and the reconfiguration of rural economies. More recently, some Alpine regions have seen a reversal of the historical trend of emigration, with niches of immigration from urban areas or other countries, motivated by the quality of environment or quality of living in small communities, as in the amenity migration of retiring people or internal migration of young people [

1]. The phenomenon of second homes, which account for 25% of the housing stock in the Alps and significantly exceed hotel accommodation, also contributes to the change in local Alpine communities [

2]. The Alpine region is gradually becoming a destination for leisure and tourism, and some areas are like businesses that monetise scarce resources, such as scenic landscapes. When these areas are close to large cities and associated with hydroelectric power and tourism infrastructure industries, they can change their socio-economic and demographic characteristics even more rapidly [

3,

4].

Studies on Alpine social capital and collective agricultural, forestry, and pastoral resources management have shown that mountain communities can demonstrate strong institutional resilience rooted in customary norms and local governance [

5,

6]. For this reason, attempts to impose a common regional identity have often been counterproductive. On the other hand, transformative development can come from welcoming new ideas and knowledge brought about by collaboration with universities and migrants [

4], together with improvements in the multi-level governance of mountain socio-ecological systems [

7].

Local governance is increasingly challenged by external narratives and actors, including destination marketing organisations, real estate investors, and regional planning agencies that promote simplified imaginaries of mountain (futures)—such as the “leisure park”, the “heritage village”, or the “sustainable tourism destination” [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In short, mountain places are arenas where exogenous investment logics and endogenous place-making frequently collide.

Land use policies and planning in such regions are often caught between two extremes: reactive interventions addressing perceived deficits (e.g., lack of infrastructure) and externally driven models of development focused on tourism-led growth [

13]. Both imply a series of assumptions about a certain continuity of present conditions (social, environmental, economic) and about the stability of values and relationships between actors. Both approaches tend to privilege short-term economic returns over long-term landscape stewardship and community well-being [

14]. Moreover, they often disregard the complex layering of local meanings, identities, and attachments to place that continue to shape life in highland areas [

15].

Territorial development is not a purely technical or economic issue, but is deeply influenced by “images of the future” and implicit assumptions about what are desirable futures. These visions of the future are not mere projections, but reflect and foreshadow the direction a society will take. As Polak observed, the rise and fall of images of the future precedes or accompanies the rise and fall of cultures [

16]. This means that debates about development are not just about specific projects, but are rooted in competing visions of what a mountain area should become.

Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) offers a way to make visible the deeper narrative layers that underpin particular futures [

17]. Sohail Inayatullah, author of the CLA, argues that changing narratives about the societal problems can lead to new solutions. CLA has spread internationally in a variety of contexts such as education, demography, work, and technological innovations [

18]. To our knowledge, CLA has never been applied to the study of Alpine regions, nor to the imaginaries shaping tourism or territorial development within the Alps.

We adopted the CLA paradigm in selected Alpine areas to ask which narratives, worldviews, and metaphors underpin different proposals for site development, and whether developments are driven by external pressures and actors or by the local community itself, which is able to steer its own development.

The Alps provide an ideal context for applying CLA because they combine enduring institutions of local governance and collective ownership with increasing external pressures from tourism, mobility, and demographic changes. This tension between endogenous and exogenous narratives makes Alpine territories particularly suitable for exploring how metaphors and imaginaries shape development trajectories.

Despite extensive research on Alpine governance, tourism, and sustainability, little attention has been paid to the cultural and narrative underpinnings of how futures are imagined and negotiated. This study addresses that gap by applying CLA to reveal the deep metaphors that shape territorial development pathways in the Alps.

In addition, different imaginaries of territorial development imply varying thresholds of acceptability regarding the environmental impacts of economic activities. Accordingly, shifts in dominant narratives can transform how tourism carrying capacity and overtourism are evaluated. In other words, an identical number of visitors at a given site and time may be perceived either as a case of overtourism or as a desirable outcome, depending on the prevailing vision of the community’s economic future.

This study addresses two main research questions: (i) which narratives and metaphors underpin contrasting models of territorial development in selected Alpine contexts, and (ii) how the use of Causal Layered Analysis can enrich spatial planning and participatory foresight in mountain regions.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the methodological approach based on Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) and the criteria for selecting the four Alpine study areas.

Section 3 presents the main results, distinguishing the narratives and metaphors emerging from each case.

Section 4 discusses the findings in relation to the existing literature and introduces the implications for spatial planning and anticipatory governance. Finally,

Section 5 concludes by summarising the main contributions, highlighting the limitations of the study, and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

While the analytical logic follows CLA four layers, our operationalization introduces two innovations: (i) it combines ethnographic field data with document and media analysis to populate each layer with place-specific evidence, and (ii) it links the interpretation of narratives to measurable aspects of socio-ecological carrying capacity, bridging futures analysis with spatial planning practice.

The research is situated within the field of social sciences and adopts a qualitative approach grounded in applied ethnography. The methodological framework combines participant observation and long-term engagement with local communities. Data collection involved direct participation in community meetings and events, informal conversations, and systematic note-taking on local social dynamics, rather than a formal interview protocol. In addition, digital ethnography and continuous review of local newspapers and media sources provided contextual understanding and triangulation of narratives at different levels of discourse.

In particular, fieldwork was carried out intermittently over a period of 15 years (2010–2025), directly gathering the perceptions and opinions of informants through anthropological dialogues, in-depth interviews, and life stories according to ecological anthropological methodology [

19]. The time devoted to observations can be estimated at approximately 128 days, distributed unevenly among the four research fields, with a greater presence among the communities of Monte Bondone and a lesser presence in Seiser Alm. Data were also collected through digital ethnography, mainly on social media (Facebook and Instagram), from local associations, public institutions, and relevant informants (

Table 1). Sources were prioritised as follows:

These sources include the following: institutional documents of the municipalities (Trento, Rabbi, Pinzolo, Castelrotto) and provincial offices (Trento and Bolzano); development project documents, both those subject to public deliberation and those involving private owners (in particular ASUCs’ projects); articles in the media (daily and weekly newspapers).

To structure and interpret qualitative information, we followed the four-level Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) paradigm. The CLA interprets discourses on reality and the future on four levels:

Litany: The diffused description of the problem, often including quantitative data used for political purposes, as reported in media headlines.

System or social causes: The short-term explanation, including social, economic, and political factors, found in reports or technical documents supporting policies or plans.

Discourse or worldview: Distinguishes the deeper assumptions underlying problems, which are important for understanding the issue from a possible multiplicity of world views, which is part of critical thinking.

Myth or metaphor: Includes deeper narratives, collective archetypes, and emotional and subconscious dimensions (embedded in cultures, e.g., Western or Eastern); art and science fiction easily access this level.

The objective of using CLA is to derive a more explicit definition of underlying values and references, and, starting from possible changes at distinct levels (interpretations, discourses, or worldviews), a richer variety of plausible scenarios.

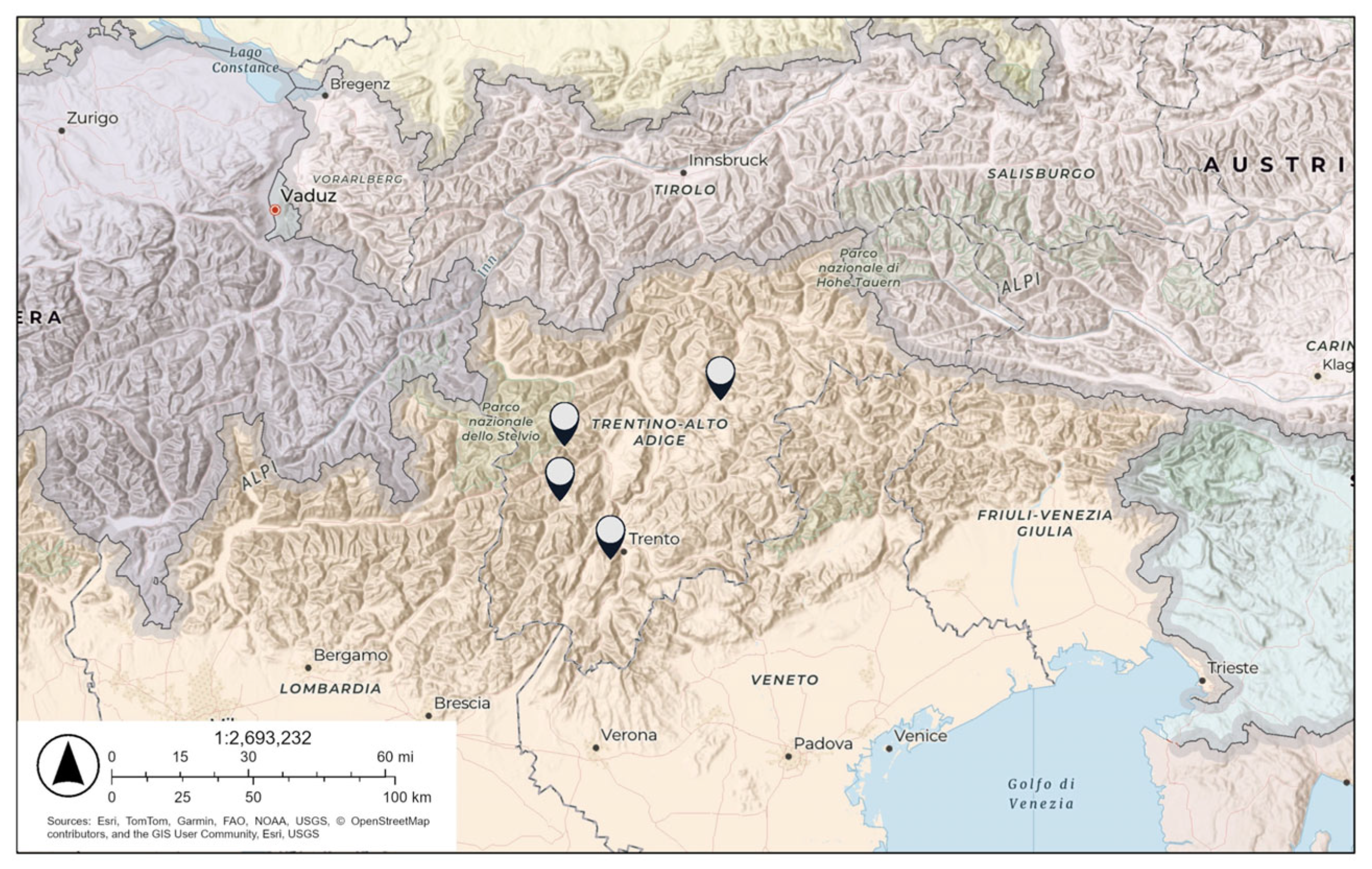

The selection of study areas is based on criteria of opportunity (prior knowledge and proximity), variety of current development policies, and the presence of local communities capable of guiding territorial development. Four areas in the Italian Alpine region of Trentino-Alto Adige Südtirol were therefore selected: Monte Bondone, Val di Rabbi, Seiser Alm (Italian name Alpe di Siusi), and Campiglio Dolomiti di Brenta ski area (

Figure 1;

Table 2).

The four study areas represent a variety of governance regimes that embody traditional forms of shared ownership and decision-making. They provide particularly insightful contexts to explore how local narratives and metaphors shape collective imaginaries and, consequently, the range of possible and desirable futures for mountain communities.

The Monte Bondone mountain range belongs to the Trento municipality and combines natural heritage with recreational facilities, covering an area of approximately 275 km

2. Part of this territory is protected as a Natura 2000 site and as a local network of nature reserves: the Special Area of Conservation IT3120015 ‘Tre Cime/Monte Bondone’; another part is promoted as a ski area. The proximity to the urban area of Trento (with more than 120,000 residents) gives rise to recurring proposals for cable car connections as a lever for tourism, which is already relatively developed. Monte Bondone records around 250,000 tourist overnight stays per year (see

Table 2 for further data).

Monte Bondone holds a significant heritage of collective property managed under Italian Law 258/1957 on the Separate Administrations of Civic Use Properties (ASUCs), which independently govern communal assets. Three hamlets—Sopramonte, Vigolo Baselga, and Baselga del Bondone—have their own committees, while others fall under the municipality of Trento. The ASUCs have been crucial in safeguarding these assets from speculative interests. In Sopramonte, the ASUC manages nearly 1000 hectares of agricultural, forestry, and pastoral land and funds public works for the community. In Vigolo Baselga, the committee was formed to resist unilateral municipal decisions seen as harmful to local interests, while in Baselga del Bondone it was created to restore self-management after a forest fire and the illegal occupation of pastures. Together, the three ASUCs have opposed urbanisation projects and unsustainable initiatives, such as a new artificial snow basin, reaffirming their key role in protecting the mountain’s natural and cultural heritage in line with Italian Law 168/2017 [

20].

Val di Rabbi, a relatively remote valley in the province of Trento, attracts a growing number of seasonal tourists drawn by its thermal springs, scenic landscapes, and outdoor attractions such as the suspended walkway (“Tibetan bridge”). Land in the valley is still managed collectively through the historic system of Consortelle (collective estates), established in medieval times to ensure family subsistence, with membership passed down through inheritance. This system remains vital for maintaining the balance between the natural landscape and human presence. The entire territory is owned by local inhabitants and divided into 23 Consortelle, each corresponding to a hamlet and governed by its own statute regulating asset management and community life [

21].

Seiser Alm, the largest plateau in Europe (1680–2350 m), encompasses the municipalities of Kastelruth, Seis am Schlern, Völs am Schlern, and part of the Sciliar-Catinaccio Nature Park. Private traffic is restricted from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., with most visitors arriving by cable car or bus. The area also features collective properties owned by residents, known as “Amministrazioni Separate dei Beni di Uso Civico” (ASBUC) or “Interessenze”, linked to the “Maso Chiuso” (“Geschlossener Ho”f, or entailed farm) institution. The collective ownership of agricultural, forestry, and pastoral resources follows regulations rooted in Germanic law (“Gemeinschaft zur gesamter Hand”, common ownership), requiring land use and maintenance by groups of two to twelve farms [

22].

The Campiglio Dolomiti di Brenta ski area, comprising the municipalities of Madonna di Campiglio, Pinzolo, Folgarida, and Marilleva, features 156 km of slopes served by 59 ski lifts, making it one of the largest and most developed ski destinations in the Dolomites. Much of the land here is collectively owned, and the managing bodies generate income not only from forestry and pastoral activities but also by leasing land for ski facilities, apartment buildings, and hotels. Many traditional mountain huts have been converted into lodges offering food and drinks to hikers and skiers, with the resulting revenues reinvested to improve the area and benefit the local community [

23].

Generative AI tools (Gemini 2.5 Pro and ChatGPT 4.5) were employed to assist in the synthesis of dispersed secondary data, such as visitor numbers and local planning documents. All outputs were reviewed, validated, and corrected by the authors, who retain full responsibility for the accuracy and interpretation of the material presented. The use of AI did not substitute fieldwork, ethnographic observation, or document analysis but served as an auxiliary support for efficiency and consistency.

Data reported in

Table 2 about visitor and housing data were compiled from provincial tourism boards, municipal records, and official statistical datasets and cross-checked for consistency across the years 2018–2024. The categories reported in

Table 3 were derived from an inductive coding process applied to the ethnographic notes, planning documents, and media sources. Data were organised according to the four CLA levels (litany, system, discourse, metaphor), allowing the identification of three recurrent narrative constellations—exogenous, endogenous, and transformative—across the study areas.

3. Results

Here, we present a layered reading of the different narratives surrounding the development of selected Alpine territories (

Table 2). The narratives are deliberately distinguished into two opposing perspectives, between which real cases are positioned in a dynamic and changing way, each with its own mix of forces that locally dominate the discourse and, consequently, development projects. The common premises of these contrasting discourses and scenarios concern the dominant framing of problems, causes, and solutions, such as: “inland areas are at risk of depopulation” (litany level); “the lack of services and jobs boosts depopulation” (social causes or systemic level); “mountain communities must be supported or revitalised, with service levels equal to those in cities” (world view or general discourse). Underlying these discourses is the metaphor of the mountain as a “garden to be cultivated” where mountain traditions and communities are “endangered species”.

According to the mountain-as-adventure-park metaphor, development is market-driven and centred on attractions, branding, and active holidays. Success is measured by tourist arrivals, overnight stays, and spending. This system logic relies on territorial marketing and packaged services to sustain the local economy, but it also heightens seasonality and the risk of overcrowding. The community is viewed mainly as service providers, while visitors are treated as consumers of scenic beauty.

A clear example is Madonna di Campiglio, where one ASUC, under pressure from public institutions, allowed private speculation by a consortium of non-local entrepreneurs, a controversial plan to transform Malga Zangola—an area known for its biodiversity and traditional pastures—into a modern après-ski bar. The project, led by a Milan-based business group, includes a large building with video screens, loudspeakers, and strobe lights, catering to an international clientele. The national environmental NGO Legambiente awarded a ‘black flag’ (as opposed to the ‘green flag’, awarded to sustainability initiatives) to the Municipality of Pinzolo and the Landscape Protection Commission for endorsing a project that violated environmental and heritage principles.

A representative case for the mountain-as-heritage model is Seiser Alm, where landowners and administrative institutions collaborate to create a sustainable environment by regulating visitor numbers and tightly managing access. Here, the landscape is highly curated—designed as a “postcard” setting for tourists. Even the infrastructure is strategically positioned and regularly renewed to preserve a specific territorial brand [

24] with traditional architectural styles. This curated authenticity extends to residents, who are expected to wear the traditional Blaue Schurz apron as part of the visitor experience. While this system promotes participation and territorial stewardship, it also risks portraying the community as a custodian of a fixed legacy, potentially excluding newcomers and innovation—a form of “heritage under lock and key”.

For several years now, Monte Bondone has been the scene of a clash between opposing models of development, placing it dynamically between the extremes associated with the metaphors of the mountain-as-heritage and the mountain-as-adventure-park. There, public institutions, which should act as mediators, seem to favour a short-term economic vision in which investments in winter skiing prevail. Conversely, local communities through the ASUCs seem to possess both knowledge of the area and the ability to envisage its long-term development, having implemented proactive management practices that can serve as models. Shared management based on dialogue and cooperation could help build a broader community capable of addressing current territorial challenges in a win-win dynamic. Recent surveys have observed that occasional visitors tend to prefer collectively managed areas, which are better preserved, richer in biodiversity, and offer a more authentic and open experience of the mountains.

The Rabbi Valley seems to have two distinct identities: on the one hand, spa tourism is managed by a series of specialised local agencies, which copy a model inspired by the 19th century Kurhaus, updated to the modern wellness market [

25]. On the other hand, collective owner associations carry out traditional activities related to livestock farming and alpine pasture management. The two worlds seem to interact little; so, for now, the metaphors mountain-as-heritage and the mountain-as-adventure-park seem to coexist peacefully. Niche spa tourism ignores traditional rural activities, so the locality is only a backdrop and a complement to the (artificial) attractions of the valley. Only recently has the Stelvio National Park sought to promote a series of itineraries for spa visitors, while operators in the agricultural sector are seeking to promote, through their presence in institutional governance bodies, a range of local products that can be linked to wellness services [

26].

According to Inayatullah, shifting from one metaphor to another has the potential to generate different discourses, systems, and litanies, and then different possible futures. The Monte Bondone case reveals early signals of another possible narrative, something that can be associated with the open-hybrid-village metaphor, emerging at the system and discourse levels. The central idea is to have multiple ways of living and belonging to the place. Residents, returnees, long-term stayers, and commuters can all contribute to generating value. The community is perceived as permeable, welcoming, and digitally and physically connected. The system’s logic is based on co-living, co-working, and widespread hospitality to diversify livelihoods, moving beyond short-term tourism. In fact, Bondone families host tourists or travellers in their own homes or second homes converted into B&Bs, and farms offer accommodation in exchange for volunteering with farm work.

Operational indicators of the open-hybrid-village model can include the ratio of resident-days to tourist-days, local entrepreneurship (e.g., evaluated by the number businesses owned by local people), the number of active co-management agreements, and the presence of community-based services that integrate digital and physical participation in the quality of life perceived by residents and tourists. These elements characterise communities capable of active resilience, which do not simply passively endure foreign elements, but recognise the needs of those who live there, in addition to hospitality, strengthening social ties, including intergenerational ones, and adopting and spreading social innovations.

This system’s logic may see local institutions (consortia, cooperatives) aligning ecological indicators (soil, water, biodiversity) with social ones (care, learning, livelihoods). Thus, the community would be seen as a group of intergenerational caretakers, and visitors as contributors (e.g., through volunteering in the community). These examples illustrate the broader tendencies documented in regional planning and tourism studies across the Alps [

8,

10,

15], suggesting that the observed dynamics are not isolated but reflect recurring tensions between conservation and commodification in mountain governance.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how Causal Layered Analysis can reveal the deeper assumptions shaping Alpine territorial futures. To our knowledge, this is the first application of Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) to Alpine contexts. While a substantial body of literature exists on Alpine tourism, landscape governance, and rural development, previous research has rarely addressed how underlying narratives and metaphors influence collective imaginaries and future-oriented strategies. This study therefore introduces CLA as a novel interpretive tool to reveal these deeper layers within the discourse of Alpine territorial development and connects our empirical findings to broader debates in critical futures studies and anticipatory governance.

Building on a comparative reading of four cases, we showed that two dominant, partly antagonistic, models—mountain-as-playground (market-driven, attraction-oriented) and mountain-as-heritage (rule-driven, conservation-oriented)—coexist and frequently collide. We also identified weak signals for a third, emergent constellation that we term the open-hybrid-village, in which multiple forms of belonging and contribution (residents, returnees, extended stay visitors, digital workers) are recognised and mobilised. What we interpret as the findings across the CLA layers can be applied beyond our cases to the wider Alpine region; here below are some considerations about that.

4.1. Interpreting the Layered Findings Across Cases

In line with recent calls for participatory foresight in mountain governance [

7,

14], the CLA shows three different perspectives that could open up spaces for dialogue between actors, in which the definition and transition between different locally desirable visions are the subject of explicit debate and anticipatory governance. Below we present the three perspectives through the CLA levels, in which different communities in the Alpine region could find elements of similarity, desirability, or undesirability. The three metaphors could evoke entire sets of indicators, rules, and investment orientations.

Litany (the visible problem): In the playground model, success is narrated through visitor-centric indicators (arrivals, overnights, skier-days). In the heritage model, the litany is dominated by preservationist metrics (access limits, compliance rates, landscape aesthetics). Across both discourses, depopulation and service decline are treated as key symptoms to be countered by external investment and/or restrictive regulation. By contrast, the open-hybrid village reframes the litany through people-and-place indicators such as resident-days, livelihood diversity, quality-of-life self-assessments, and stewardship effort (e.g., days of volunteer maintenance, citizen science contributions, care and ecosystem services, positive externalities).

System/causes (institutional and economic logics): The playground model aligns with destination branding, large-scale lift infrastructure, and real-estate dynamics that amplify crowding. The heritage model relies on plans, standards, and protected-area instruments that rightly safeguard ecological values yet can harden into gatekeeping and status quo bias. In both, local communities risk becoming either merely service providers to external demand (as for adventure parks) or custodians of a fixed past (heritages). The open-hybrid village may mobilise polycentric governance, self-government, linking collective landholders (ASUC/Consortelle/Interessenze), public administrations, parks, and civic groups, to orchestrate co-living/co-working, small-scale hospitality, and circular value chains (agro-forestry, care, learning, repair). This system logic can broaden local economies and reduce dependency on tourist seasons.

Worldview/discourse (implicit assumptions about development and community): The playground worldview casts visitors as consumers and locals as service labour; the heritage worldview centres “natives” as exclusive custodians. The open-hybrid village contests both by adopting an inclusive community of place: residents, long-term guests, return migrants, and commuters are recognised as contributors, bound by reciprocity, and shared maintenance of socio-ecological functions.

Myth/metaphor (deep history): The playground evokes exclusively a playful dimension and approach to the place, where everything is possible and without limits; heritage evokes a museum under lock and key, vitrified, unchangeable; the open-hybrid village evokes a living collective asset which is not a garden to be kept pristine for spectators, but a resilient socio-ecological system animated by intergenerational management and negotiated openness.

The narrative of metaphors and what they may imply is intentionally exaggerated to represent the boundaries of a space of possibilities: real cases are and will move in intermediate positions, according to the debates between actors and the relationships between economic, social, and environmental elements. In fact, our cases show a mix of these elements, although some directions seem to be dominant today: Campiglio is oriented towards the mountain-as-adventure-park; Seiser Alm is an example of a garden-to-be-tended; Monte Bondone and Val di Rabbi show the seeds of change in civic protest against standardised tourism or landscape models.

4.2. Reframing “Carrying Capacity” Through CLA

Since the way in which a problem is framed determines the indicators, thresholds, and actors involved in its solution, our hypothesis is that the way in which desirable futures are defined also determines a different framing of the carrying capacity of an Alpine area. With this in mind, we believe it is interesting to apply the CLA to the assessment of anthropogenic carrying capacity.

A contemporary view of “carrying capacity” in nature-based tourism moves beyond a single fixed number and treats capacity as a set of “measurable thresholds” for change in both resource conditions (e.g., trail erosion, vegetation loss) and the quality of visitor experience (e.g., encounter rates, perceived crowding). In natural parks, this approach is operationalised through Visitor Use Management (VUM) families—LAC, VERP, VIM, IVUMF, and TOMM—which are all variants of a management-by-objectives cycle: set objectives select indicators and thresholds, monitor and implement actions, and iterate [

27,

28]. In these processes aimed at managing visitor use to achieve and maintain the desired resource conditions and visitor experience quality, the quality of life of the local community residents is rarely considered.

The counting of indicators seems to be expressions of the litany level, while usage-impact functions and access policies can be framed at the system level; debates about “wildlife protection” versus “visitor experience quality” can be placed at the worldview/discourse level; and deep myths/metaphors (e.g., the mountain as “sanctuary” versus “playground”) ultimately determine which thresholds local communities or society at large can accept.

CLA could make the definition and negotiation of ‘acceptable impact thresholds’ more systemic and forward-looking. Conventional visitor use models define carrying capacity as a threshold for resource conditions and visitor experience. However, when applied in isolation, they prioritise litany- and system-level concerns about flows and impacts, leaving worldviews and metaphors unchallenged. A CLA perspective highlights the value judgements inherent in capacity debates (e.g., “nature reserve” versus “playground”) and can help broaden the object of carrying capacity from visitor-site interactions to socio-ecological carrying capacity by combining, for example,

Ecological thresholds: soil, water, habitat, disturbance regimes;

Experiential thresholds: frequency of encounters, perception of crowding;

Community thresholds: affordability for residents, percentage of long-term rentals versus second homes, sustainability of essential services in all seasons, transmission of place-based knowledge.

This expanded vision suggests adding two families of indicators to spatial planning and landscape management practices in the Alps, such as the following:

- (1)

Community well-being and continuity (e.g., length of stay of residents, stability of school enrolment, volunteer involvement in management, percentage of local supply).

- (2)

Quality of governance (e.g., degree of participation of collective owners in planning decisions; existence of co-management agreements; transparency of revenue redistribution).

At the operational level, these indicators can be integrated into management cycles by objectives alongside ecological and experiential parameters, with thresholds negotiated through participatory foresight. These findings resonate with Ostrom’s view that collective action and local rule-making are central to resilient socio-ecological systems [

29,

30] and extend this perspective by showing how shared narratives and metaphors act as governance resources.

4.3. Methodological Implications: What CLA Can Add to Spatial Planning

Conventional planning approaches focus on indicators and forecasts and present problems; CLA reveals the deeper cultural and narrative assumptions driving policy and investment choices. Its contribution lies in opening deliberative spaces where technical and symbolic dimensions of planning can be jointly negotiated, enabling more anticipatory and plural governance of mountain territories. Three contributions emerge:

Explicitation of assumptions: The CLA makes explicit the often implicit assumptions that organise plans and projects. In our cases, it revealed how “more tourism, the better” is taken for granted in situated narratives and how “closed heritage” risks excluding new actors. Naming these assumptions allows us to redefine the framework before locking in the present with investments.

Dialogue across knowledge systems: By stacking litany, system, worldview, and metaphor, CLA provides a common scaffold where technical evidence (counts, thresholds), institutional analysis (rules, incentives), and cultural insights (identity, belonging) can be held in the same conversation, reducing the false trade-off between numbers and narratives.

Design of transformative options: While conventional planning tends to “close” the future (by predicting it and influencing the present on the basis of the most probable forecast), the critical approach to futures aims to open alternatives. Considering metaphors as design levers helps to generate multiple (richer) options that neither idealise conservation nor are based on growth-oriented logic, but allow us to imagine permeable communities adapted to the constraints and opportunities of the Alps.

In this study, the conceptual nature of CLA is central: by reframing how actors talk about and interpret their territories, it reveals how changing narratives can ultimately transform the criteria, values, and tangible actions that shape territories. The framework thus serves as a cognitive and interpretive bridge between discourse and practice, rather than an empirical model derived directly from data.

4.4. From Case Findings to Alpine-Wide Implications and One Suggestion

Collective land ownership systems are strategic resources for the long term. Institutions such as ASUC/Consortelle/Interessenze can consolidate hybrid models that are more adaptive and resilient to economic and environmental uncertainties. Involving these collective actors in planning processes as co-governors and not just as stakeholders can improve the alignment between the enhancement and care of the territory and the community.

Mobility planning shapes the local future. Access rules (e.g., Seiser Alm) that influence flows, if based on forward-looking visions, can better reconcile the quality of the experience and the well-being of residents with the preservation of territorial identity in the long term.

Future literacy for governance: Establishing a participatory and continuous definition of desirable visions for the territory using CLA at the municipal or valley level (e.g., in annual assemblies on “images of the future”) can help evaluate local development strategies in relation to multiple worldviews and avoid embarking on fragile or exogenous development paths that are difficult to reverse.

These suggestions are compatible with existing planning tools, but require an explicit cultural change: treating imaginaries as governable objects rather than invisible drivers.

It is important to emphasise that the results are not intended to favour the hybrid village model, nor to claim that it is better than the others (mountain-playground, mountain-heritage). On the one hand, elements of the three narratives can coexist in a single territory; on the other hand, all three extreme positions are not sustainable in the long term. Only the community can define its own desirable future and the implications it will have to manage. The key value we intend to promote is the conscious plurality of visions, with the relative definition of problems and solutions, which emerges from a plurality of actors.

Based on these considerations, we imagine the dissemination of workshops “on local futures” as an opportunity for local communities to distinguish between exogenous visions (guided by external actors/values) and endogenous visions (rooted in the community and the territory), share narratives, and orient the present more consciously and collaboratively. A quick guide for this workshop could be the following series of questions (

Table 4).

4.5. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Our analysis is based on four Italian cases with uneven data depth, combining long-term ethnography with document and media scans; this constrains transferability across the wider Alpine arc. The aim was theory building rather than statistical generalisation. Future sampling should adopt a comparative, multi-country design (among the interested seven) to test whether the three narrative constellations recur under different policy regimes and property institutions [

4].

CLA is interpretive and sensitive to researcher framing. While this is a feature (surfacing imaginaries), it can introduce confirmation bias, especially where long engagement in some sites strengthens contextual insight but may also influence interpretation. We countered this by (i) contrasting ethnographic insights with media and plan document analysis; (ii) checking consistency across layers; and (iii) explicitly naming alternative metaphors. Future work should pair CLA with participatory scenario planning and structured elicitations (e.g., Delphi) to validate layer transitions and term choices [

14,

31].

Large language models supported the translation and rapid synthesis of dispersed materials; we are aware that LLM-assisted estimates must be documented, reproducible, and validated against primary sources before being used for policy purposes.

The paradigm of Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) responds to the intention of broadening the spectrum of possible (and thinkable) futures and questioning the “presentification of the future”. We think our results advance the understanding of how Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) can be operationalised in mountain contexts, contributing to both critical futures studies and participatory spatial planning.

Practical takeaway (for planners and communities): When debating a project or plan in the Alpine space, ask at each CLA layer: What problem counts? Which system logics are we privileging? Whose worldview defines the community? Which metaphor is steering us—and is it the one we want? Designing with these questions up-front can widen the option space and support more legitimate, resilient pathways for Alpine territories.

5. Conclusions

This paper applied Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) to four Alpine contexts to explore how competing narratives and metaphors shape territorial development pathways. The study revealed two dominant models—the mountain-as-adventure-park and the mountain-as-heritage—which often coexist and clash, while weak signs of an alternative metaphor, the open-hybrid-village, point to a more pluralistic and participatory future. By reformulating the concept of “carrying capacity” through CLA, the paper extends the concept beyond ecological and experiential thresholds to include community well-being and the quality of governance. Methodologically, it shows how CLA can integrate spatial planning by testing hypotheses, promoting dialogue between knowledge systems, and designing transformative options. The results suggest that collective landscape management and participatory forecasting processes can improve local anticipatory governance. The limitations of the study lie in its qualitative and site-specific design, which limits its generalisability but provides a valuable interpretative lens for future comparative and participatory research in mountain regions.

The key message is that landscape management and planning should not be limited to solving today’s problems or anticipating immediate ones, but should include visioning exercises that make explicit the implicit “images of the future” that guide decisions, facilitating collective negotiation and the emergence of alternative, potentially more open futures.