Abstract

Truth-telling, a community intervention to increase reconciliation after systemic injustices, has been employed recently to increase public awareness of harms perpetuated by the child welfare industry in the U.S. Guided by participatory action research principles, we examined a public truth telling initiative over two years which was co-designed by a trans-experiential team of emerging adults with lived expertise and child welfare system professionals in Kentucky. The aims of the truth-telling events were to raise awareness about the experiences of Black American youth in the Kentucky child welfare system and generate ideas for improvements. We conducted a longitudinal collaborative autoethnography (n = 9, 2 time points) to examine our collective experience of developing and hosting the truth-telling circles and supporting activities. Key themes included the transformative impact on the alumni of receiving validation and acknowledgement, as well as forming social and professional connections. Some concerns related to timing of activities and group dynamics also were reported. In addition, the four lived expert truth-tellers engaged in a systematic consensus workgroup process to select a list of 10 priority practice and policy recommendations, such as child welfare system alumni being hired to provide emotion regulation and self-advocacy skills training directly to youth.

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

Truth telling, a formal community intervention strategy for redressing group harms and promoting community uplift and healing, has been increasing in the U.S. over the past two decades [,]. Truth telling has demonstrated promise not only as a form of educating communities and societies about the human costs of violence, mistreatment, and oppression, but also as a means of direct healing for survivors of shared trauma [,]. Individuals transitioning to adulthood who have spent time in out-of-home care face unique obstacles to the successful transition to adulthood [,]. These obstacles can be exacerbated for those, such as Black youth, who have experienced racial bias or cultural insensitivity. Therefore, truth telling represents a potential tool to concurrently provide community education about the experience of the transition from the foster care system to adulthood for Black Americans and also help emerging adults make sense of their experiences in ways that promote positive identity development and potentially mental well-being.

1.2. Achievement of Developmental Milestones Associated with the Transition to Adulthood for Black Youth Involved in the Child Welfare System

Transitioning to adulthood is a longer and more complex process today than in other times in history [,]. The transition to adulthood can be even more complicated, non-linear, and challenging for youth and emerging adults who experienced different forms of out-of-home care (i.e., foster care, residential placement) [,,]. Typical markers of the successful transition to adulthood are the achievement of milestones across development domains, including exploration and stabilization of a core identity, means for financially supporting oneself, developing skills to maintain romantic relationships, and choosing a vocation [], with the achievement of these goals typically being scaffolded and supported by biological parents []. Youth who have spent time in out-of-home care have, by definition, experienced some interruptions in their relationships with biological parents, thus leaving them more vulnerable to insufficient family support to transition to adulthood compared to youth being raised exclusively by biological family members. In addition, restrictions and limitations in financial resources available to foster care alumni can pose significant challenges to their ability to obtain stable housing and financially support themselves []. Traumatic events occurring before, during, and after out-of-home care, and their psychological impacts, can also make it difficult for those previously involved in the foster care system to attend to the various tasks needed to transition to independence.

1.3. Disproportionalities and Disparities Impacting Black Youth in Child Welfare Nationally and in Kentucky

A discussion of the struggles of Black American children and youth involved in the foster care system requires a brief overview of the two related but distinct concepts of “disproportionality” and “disparity”. Racial disproportionality refers to the under- or over-representation of certain groups in the child welfare system at levels that are disproportionate to their numbers in the overall child and family population []. Racial disparity refers to the unequal treatment of certain groups due to their race [], which may increase disproportionality and adverse child welfare and other life outcomes.

Evidence of the over representation of Black American children in the nation’s child welfare system has been well documented in academic research, with many more Black families and children likely to be referred for intake and investigation, to be placed in foster care, to experience longer stays in care, and to reunify with their families more slowly than non-Black children [,,,,]. In 2022, Black children accounted for 13.9 percent of the overall child population in the U.S., but 23 percent of the foster care population, for a disproportionality rate of 1.65 []. The disproportionality rate in Kentucky is even higher at 1.71, with Black children making up 16.3 percent of those in foster care in 2022 [], while only 9.54 percent of the youth in the state in that year were Black []. In other words, Black youth in Kentucky have a 71% elevated risk of being involved in the foster care system compared to what would be expected by their representation in the general youth population.

The causes of disparity, disproportionality, and inequity more broadly in child welfare and other human services systems have been extensively studied and documented. These causes are often grouped into the following categories: (1) policy and legislation, (2) disproportionate needs, (3) institution and organizational factors, and (4) racial bias and discrimination []. These factors likely co-exist and are inter-related, and together provide a deeper understanding of the dual phenomena of disparity and disproportionality [].

1.4. Truth Telling to Address Systemic Harms and Injustices

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) have played a significant role in addressing historical and systemic injustices around the world. For example, South Africa’s TRC focused on Apartheid-era human rights abuses [], South Korea’s addressed colonial and post-war massacres and political repression [] (and Sierra Leone’s [] and Guatemala’s both focused on civil war atrocities []. In the U.S., the first TRC was launched in 2004 to promote accountability and healing in the aftermath of a racialized terrorist attack in Greensboro, NC, in 1979. In that year, the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party killed five demonstrators and wounded several others who were engaged in a multi-racial union protest []. Some features of TRCs include public hearings, calls to action, national awareness campaigns and public acknowledgment, recommendations for prosecutions and reparations, cultural revitalization efforts, and policy reforms.

In a child welfare context, there are some notable TRCs and related inquiries with the aim of uncovering past abuses, forcible removals of children from families, tribes and communities, and genocidal practices. Canada’s TRC (2008–2015), which investigated the legacy of the Indian Residential School system where over 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families, resulted in numerous calls to action addressing child welfare and affirming Indigenous jurisdiction over child welfare []. In Maine, the Wabanaki-State Child Welfare TRC (2013–2015) was the first of its kind in the United States to address the removal of Wabanaki children from their communities, and in addition to awareness building and creating a space for healing, the Commission recommended systemic changes to child welfare []. In Australia, the forced removal of Aboriginal children or the “Stolen Generations” was reported in the 1997 report Bringing Them Home, laying the groundwork for subsequent national apologies, a formal National Sorry Day, and other policy reforms []. Most recently, in 2021, the Yoorrook Justice Commission, which is the first Indigenous-led TRC in Australia, launched to address systemic injustice against Aboriginal people, which includes the harms caused by child welfare systems [].

Community truth-telling initiatives have been reported as leading to a number of positive outcomes. Truth tellers have described experiencing healing, validation, and interpersonal reconciliation through TRCs [,]. In addition, participants in TRCs have reported they can help increase public knowledge and re-orient framing of past systemic harms to more democratic and justice-oriented conceptualizations []. Some limitations of TRCs have also been reported, including that they may help facilitate but be insufficient on their own to usher in widespread political or social change, particularly when curated by local or national governments [,].

Truth-telling may be informed by the post-traumatic growth framework, which suggests that some survivors experience newfound strengths, perspectives, and purpose after a traumatic event []. Post-traumatic growth can be manifested as a variety of positive personality, attitude, and behavior changes, such as a greater appreciation of life, more empathy for others, deeper spiritual understanding, richer interpersonal relationships, and more meaningful and grounded personal identities [,]. Importantly, some studies have suggested post-traumatic growth is facilitated by social support, such as experiencing validation and connection from others in a person’s interpersonal network [,].

Another advancement in the literature on public health and community-focused interventions is the study of arts-based story-telling. Story-telling in general is synergistic with values in non-Western cultures, including the Black diaspora, such as emphasizing oral traditions, connection between intellect and emotions, interpersonal relationships, and prioritizing the broader community []. Personal narratives that incorporate art can be an organic and authentic way of expressing one’s understanding of an experience that allows one to overcome limitations in expressing feelings that are difficult to put into words [], particularly ones that involve traumatic events []. The process of creating art as a vehicle for self-expression can also be therapeutic as it can facilitate meaning-making, processing of emotions and thoughts, and relaxation [,]. Additionally, communicating thoughts and feelings through art can have the benefit of allowing audience member participants to understand another person’s experience through multiple modes, written or verbal expression as well as visual and/or auditory arts. This can allow participants to process shared material more deeply by engaging multiple senses [,]. Thus, an art-based truth-telling initiative to elevate and illuminate experiences of Black youth in the foster care system can potentially facilitate processing and healing among truth tellers and engagement and learning by witnesses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Project Description

The Truth Telling Circles (TTC)-Louisville project was one of three sites funded by a national foundation and was part of the Together in Truth (TinT) Initiative, which had an advisory group of 50 national multi-disciplinary, geographically dispersed and ethnically diverse advocates, researchers, academics, philanthropists, and industry leaders co-designing a set of principles and practices for truth telling. The TinT coalesced around the idea that truth-telling about the U.S. child welfare system had the potential to not only lead to structural policy and practice changes, but also healing for all involved with child welfare systems and processes. To normalize and nest truth telling in the realities of local contexts, non-profit organizations in three local communities were recruited, including Louisville, Kentucky, the Pueblo of Nambe tribal nation in New Mexico, and Washington, D. C., to co-create and co-design a truth telling process. This paper will report on the TTC-Louisville site.

The implementation and evaluation of the TTC-Louisville project was guided by a participatory action research (PAR) orientation. PAR emphasizes the role of context and socio-political position on the perspectives of participants and researchers and therefore, as well as of research leading towards action to benefit those studied. Torre (2009) has crystallized these ideas into nine assumptions, such as “All people have valuable knowledge about their lives and experiences”, “All people have the ability to develop strong critical analyses (of the world, data, social experiences, etc.),” and “Change is an ongoing process” []. More recently Feekery (2023) has articulated seven characteristics of PAR to guide participatory research teams, specifically that PAR is Cyclical, Collaborative, Context-specific, Critically reflective, Combining theory and practice, Change-focused, and Conversation-driven [].

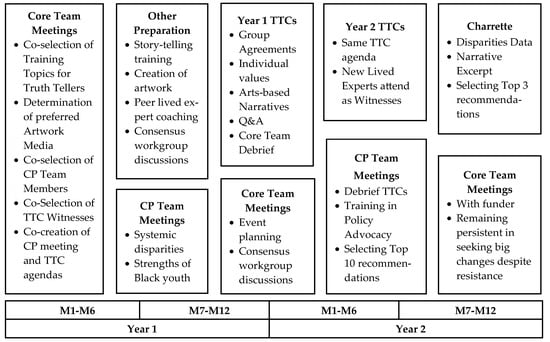

During the two years that are a focus of this study, the TTC-Louisville project engaged in a sequential set of iterative activities designed to achieve the two-fold purpose of: (1) Raising awareness regarding experiences of Black youth in the foster care system in Kentucky; and (2) Generating ideas for changes in child welfare practice or policy in the state. Consistent with the collaborative, community-centered emphasis of the project, considerable time and energy were devoted to establishing and building relationships among the core team, as well as selecting the specific community partners. In addition, project activities were sequenced such that initial planning meetings with the core team and community partners focused on establishing a collective understanding of systemic influences on racial disparities and disproportionalities in the child welfare system, providing training on trauma-informed story-telling methods for the truth tellers, planning an agenda for the truth telling circles that would be empowering and promote safety, and determining the witness list. In line with the PAR characteristic of iterative and cyclical learning [], and the fact that this was a pilot study, the core team engaged in debrief sessions after each community partner and truth telling circle event. Those lessons then informed the format and focus of subsequent project activities. As the project unfolded, toward the end of year one, core team and community partner meetings became more focused on distilling commonalities across the stories and translating the narratives into potential actions that could be taken to improve child welfare system practice and policy. See Figure 1 below for a depiction of the sequence of these activities.

Figure 1.

Timeline of TTC-Louisville Activities. Notes. CP = Community Partner, TTC = Truth Telling Circle, Y = Year, M = Month.

Core Team. The TTC-Louisville project core team met bi-weekly to monthly throughout the two years of the project. In Year 1, the core team consisted of 10 collaborators including two co-leaders, a professional foster care alumni advocate and a young adult lived expert with experience in the foster care system; three other young adult lived experts; a representative from the national TinT technical assistance team; and the implementation science and evaluation consultants. The main grantee organization had the following criteria for selecting lived experts: (1) Identify as Black American, (2) Had personal experience as a youth in the child welfare system in Kentucky, and (3) Had been involved in a foster care alumni advocacy organization. In Year 2, the core team consisted of 7 people, including 3 lived experts who continued as members of the Core Team, and 4 of the members acting in a professional capacity. The number of professional members of the Core Team was reduced in Year 2 because of a decrease in grant funding. Each lived expert acted as a contractor during their time working on the grant, which was between 1 and 2 years depending on the individual lived expert and was paid $25 per hour for their time spent on project activities, such as attending meetings, planning, preparing of art-based testimonies, and providing public testimonials. The lived experts were not paid for their time drafting and reviewing this manuscript in their roles as voluntary co-authors, which began approximately 6 months after the end of Year 2.

In Year 1, the lived expert co-leader co-designed the activities and contributed to the collaborative process by encouraging transparent communication, accountability, and the alignment of individual contributions with the project’s collective goals. A central focus during these core team meetings was fostering a safe and brave space that encouraged candid dialogue among team members. The team collectively developed core team meeting agendas, which included a beginning ritual of re-affirming that members would support a safe and brave space for all team members and a “check-in” question, such as a positive development that had happened in team members’ lives since the last meeting. The core team collaboratively planned the execution of all grant project activities, including Community Partner Team member list selection and meetings, training of lived experts in trauma-informed truth telling, TTC agendas, and Witness lists and instructions. The Community Partner and Witness lists were collaboratively developed with team members generating ideas of ideal representatives from non-profit youth-focused organizations, the child welfare system, and other community groups. Given this was a pilot study with the use of truth telling circles with a new population, we also drafted together a manual to capture the various components of the TTCs. In Year 2, we continued to make decisions together and co-planned all Community Partner meetings, TTCs, and the culminating community charrette.

Lived Expert Training and Relationship Building Outside of Core Team Meetings. We utilized several types of training and coaching modalities and modules to help co-train the lived experts. Over the course of Year 1, the lived expert co-leader provided support and coaching to the other lived experts as they planned, designed, and coordinated each stage of their artwork being created. In addition, a two-lived-expert team of consultants was contracted to provide training related to intentional story-telling and facilitation skills. The consulting team trained the lived experts in strategies for telling their stories in a way that protects them and the audience from harm, including the importance of self-monitoring one’s emotional reactions throughout different components of telling one’s stories and making adjustments as needed. The lived experts also received training in racial trauma, facilitated by one of the identified community partners. Lastly, a local expert in the truth telling process shared knowledge, attended dress rehearsals, and suggested a book to read [] in preparation for the truth telling circles.

Additionally, the project supported relationship building and nurturing amongst the Lived Expert alumni in between the bi-weekly meetings via social activities (e.g., going to Escape rooms, dinners) and one-on-one interactions. As the project progressed, we sought to involve a larger number of Lived Experts in project activities. For example, during Year 2, two Lived Expert core team members and two additional Lived Experts not a part of the core team were supported to attend the Prevent Child Abuse America conference. Additionally, a professional development training was provided to further strengthen their capacity to fill leadership roles within the Thriving Families movement and grant work.

Artwork Creation. The art pieces took between three and six months to create, depending on the level of technical support needed. Members of the core team conducted 1-on-1 assessments with young adult project team members to understand their specific needs, strengths, and aspirations related to creating hybrid oral and art-based truth narratives about their experiences with the child welfare system. These assessments informed tailored support strategies, including contracting with external resources such as artists, videographers, and sound studios, thereby empowering team members to authentically craft and present their truth telling testimonies. Each of the four lived experts created artwork as vehicles and complements to their stories. The art forms utilized included a series of paintings [], mixed medium painting and sculpture, a digital video that mixed graphic art with recorded testimony, and a hip hop song. See Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 2.

Truth-teller Artwork 1: “Identity: Gained & Lost”. Designed by: Glenda Wright, J.D.

Figure 3.

“System vs. Growth”. Designed by: Tia Humphrey.

Figure 4.

“Now or Never”. Produced by: Eltuan “SirSki” Dawson.

Figure 5.

“Cameron Galloway’s Story”. Designed by: Cameron Galloway.

Community Partner Team. Core team members collectively created a list of individuals to invite to a broader Community Partner Team, consisting of professionals and community members interested in reducing disparities in the child welfare system affecting Black youth, including non-profit organizations focused on supporting youth in and alumni of the foster care system, social justice organizations, and mental health and positive youth development scholars-practitioners. The Community Partner Team met on average quarterly during the two years. In the first year, the focus of the Community Partner meetings was to increase awareness and cross-system information sharing about issues relevant to the experiences of Black youth in the child welfare system. The focus of Community Partner meetings included topics such as ways to reduce racial disparities in the child welfare system, to hear anecdotal experiences related to the child welfare system, and the positive development of Black youth in general. These community partner meetings also helped inform and buttress ongoing planning for TTCs, which is described next. Over time, the core team and community partner meetings became increasingly focused on selecting which practice and policy recommendation were the top priorities, and on the core team and partners receiving training from child policy advocacy experts at the main community organization to be able to eventually advocate for the recommendations that were most important and feasible.

Truth Telling Circles and Charrette. Over the two-year course of the project, we held five Truth Telling Circles (TTCs), in which the lived experts presented their arts-based testimonies, as well as a Charrette for the wider community which included an excerpt from a lived expert’s narrative. Witnesses included members of the Core Team who were not Lived Experts (community partner organization representatives, evaluators), and community partner witnesses (e.g., representatives from the child welfare system, community organizations focused on supporting youth or alumni of the child welfare system, social justice oriented community organizations, a court appointed special advocate, state legislators, and friends and other support persons of the truth tellers). In the second year, we also made a concerted effort to invite four new young adult alumni of the child welfare system to attend truth-telling circles as witnesses. Across both years, the total unduplicated number of witnesses to the lived experts’ testimonials was 39. Of note, 3 witnesses who were from agencies came to two truth-telling events, and 4 of the young adult alumni attended two or more truth-telling events.

Each TTC lasted approximately four hours and followed a common agenda that had been co-developed during core team meetings consisting of: Group Agreements, Updates on the state of the child welfare field, Participants and witnesses each selecting a personal value to anchor and center them through the experience, Truth-telling testimonials, Q&A in which witnesses submitted questions to the lived experts and lived experts selected questions to which to respond. Each TTC included a calming room for truth tellers where they could relax and have a snack. The work culminated at the end of year two in a community charrette, co-facilitated by lived experts, in which the recommendations were shared with a large group of professionals and community members and the attendees reflected on the recommendations and their experiences. The core team designed the charrette to engage community partners in the work to create more equitable experiences by sharing findings with the community and creating advocacy opportunities. The team developed a brief document summarizing findings, takeaways, and recognitions from the truth telling work which was provided to charrette participants. One leader shared her post traumatic growth testimony and was joined on a panel, with a peer, to report to the community the findings from the work. Then, participants engaged in a process to identify ways to address the findings through policy and/or practice change.

Post-Year 2 Developments. After the end of Year 2, TTCs and related work has continued. Partly based on the preliminary findings from Years 1–2, the TTC-Louisville initiative received a third year of funding, which is currently underway. In addition, initial findings were instrumental in the team successfully competing for a federal grant to examine community-identified strategies to reduce racial inequities in the child welfare system. One of the strategies that will be implemented and studied is connecting families who have unmet basic and/or behavioral health needs to culturally-responsive, community-engaged social service providers who can help them meet those needs. Of note, the procedures for the study reported on here only relate to the project activities for Years 1 through 2.

2.2. Study Procedures

Throughout the project we attempted to engage in a collaborative, lived-expert-centered process. This involved co-developing a theory of change to capture and represent our collective understanding of the components of community intervention and its potential outcomes. In addition, as a team, we decided the evaluation process should parallel the organic and process-focused nature of the project. Thus, we decided to conduct a collaborative autoethnography to examine the perspectives of the core team on their experiences carrying out the project, and a consensus workgroup process to prioritize practice and policy recommendations. Collaborative auto-ethnography allows for multiple voices and perspectives about a common or overlapping experience to be heard and to analyze together their perspectives of a shared experience []. We chose collaborative auto-ethnography as our main method because it can result in a flattening of the hierarchy between participants and researchers as all involved take on a hybrid role of participant-researcher, can promote trust among the team of co-researchers, is suited to “community-based research and approaches that involve witnessing” (p. 598), and more rigorous interpretation than solo auto-ethnography due to the multiple perspectives provided []. For this project, 9 of us acted as participants, researchers, and co-authors of this resultant paper.

Consensus workgroup processes involve a group of experts who, over multiple sessions together, work to reduce and prioritize a set of recommendations for a field []. One type of consensus building process, the nominal group technique (NGT), has been employed more recently with stakeholders and lived experts to generate priorities regarding concerns and supports [,]. The nominal group technique in general involves four steps: (1) generation of ideas, (2) sharing ideas and clarification, (3) discussion, and (4) voting and ranking ideas []. Variations of the nominal group technique include the use of multiple rounds of voting and discussion, as well as whole-group consensus reaching [,]. We followed an adapted NGT process in that for step 1, generation of initial ideas was accomplished by the evaluation team documenting key aspects of the truth-tellers’ narratives that the truth-tellers identified as difficulties they experienced in the child welfare system and then the evaluators posing potential changes in practice standards or policies that might decrease the likelihood those experiences would occur for other youth. In addition, for step 4, the young adult lived experts coordinated the process of individually ranking and submitting their rankings among themselves and reported on their process at core team meetings.

We utilized the ethical standards for collaborative autoethnography articulated by Lapadat in 2017 as a guide for the ethical conduct of this study: “it is important that participation is fully voluntary, that the focus is mutually agreed upon, and that the sharing context is nonhierarchical and noncoercive” (p. 600) []. Specifically, all co-authors were invited to collaborate on the manuscript via email and/or phone, informed that whether they assisted with the manuscript was their choice, and they could change their mind throughout the process of manuscript preparation. The co-authorship team met multiple times prior to initiation of writing the manuscript to discuss and determine a direction for the paper. None of the young adult lived experts were under contract with the organization that had originally received the grant to fund the TTCs at the time we wrote the manuscript, which also promoted a democratic, noncoercive process. Finally, in consultation with the University of Louisville IRB, we determined that since we studied our own and each other’s perspectives of a shared experience, IRB approval and separate documentation of informed consent were not required.

2.3. Collaborative Autoethnography

2.3.1. Data Collection

Following collaborative autoethnography methodology, team members acted as participant-researchers to collaboratively plan, collect, and provide data. We responded to questions in writing or verbally and had the responses transcribed in real-time. The reflection prompts were organized according to the phases and activities of the project, for Year 1, such as “Preparation”, “Truth Telling Events”, and “Debriefing and Recommendation Generation”. The questions focused on what went well, what could be improved, and lessons learned with regard to the various activities, such as “What was your reaction to the initial Community Partner Meetings focused on debriefing the previous Truth Telling Circles? What went well? What would you improve?”. At the end of Year 1, n = 9 team members provided responses to questions. During the first round of data collection, our team of participant-researchers wrote responses to 5 questions. As a result of the initial team-based data analysis that identified a gap in representing our experiences, a 6th question was added to solicit responses related to unanticipated difficulties team members encountered when carrying out the project. In Year 2, due to the project’s decreased budget, n = 6 of the participating team members answered the questions. We utilized the themes identified in Year 1 responses as themes to code Year 2 data and then, as a result of team-based analysis discussions, drafted additional questions to which the team responded to best reflect our collective experiences of Year 2, and the project overall.

2.3.2. Data Analysis

Our trans-experiential team of researcher-participants included individuals with lived and professional expertise in the child welfare system. These included an African-American Senior Director who has supported youth and young adults who have personal experiences with foster care for nearly 25 years; a Black and Latina American university-based researcher with 15 years of research experience in the child welfare system; a White American child welfare system organizational practice expert with 35 years of experience; and a Black and White American child welfare consultant holding a Juris Doctorate with fourteen years of lived experience spent in kinship care provided by her grandmother, and seven years of lived experience in the Kentucky foster care system, with a professional career spanning over a decade aimed at holistically improving the child welfare system. Our team of participant-researchers also included a Black American child welfare lived expert leader who strives to transform lived experiences into meaningful policy recommendations, so future youth of color don’t face the same inequities; a cisgender, white, older adult woman who was raised in the deep South to parents who were committed to and actively supported civil rights for members of the Black community, who shares and lives out their commitment in education, community and child welfare settings, bringing 33 years of experience in child welfare; a Black and White American young adult/PhD student, who has 15+ years of foster care experience and 9 years of youth development experience specifically within the disadvantaged youth population; a Black/African American social worker with experience as a youth in foster care and 8 years of professional experience supporting other lived experts; and a Black American university-based researcher with focus and experience in child development, and community action.

We engaged in consensual qualitative coding to analyze the data because it is well-suited to analyzing written personal reflections, attitudes, and experiences in a team-based analysis process [,]. This consensual coding process was utilized within the collaborative auto-ethnography emphasis on representing multiple voices and perspectives []. After the Year 1 responses were collected, a smaller group of the team consisting of the evaluators and project director read all responses and identified themes common across them. They discussed the themes together and included their definitions and the responses that would fit underneath them. Next the smaller group presented the initial list of themes to the entire team. Through team discussion, the theme descriptions were refined and expanded upon. In addition, the team discussed whether the questions and themes comprehensively represented our collective experience of the process. We came to the consensus to add an additional question that we responded to related to unanticipated difficulties that arose. This new question was disseminated to all team members to elicit their responses. The smaller analysis team again coded the new set of responses along with applying new codes to the previous responses based on the analysis discussions with the whole core team. Analysis of Year 2 followed a similar set of steps. Because the focus of the project was essentially the same, we initially used the themes we identified in the Year 1 responses as the initial set of themes to code Year 2 responses. We presented these themes with expanded examples of excerpts from Year 2 responses to the entire team. The team agreed that the themes worked relatively well to categorize the excerpts, but that an additional aspect of our experience needed to be captured, namely our views of the reactions of witnesses to the TTC events. Therefore, this question was sent to all team members to collect our responses. The expanded set of excerpts categorized under each theme was presented to the full team, and the team members concluded that the themes captured the similarities and distinctions in perspectives across the team.

2.4. Consensus Workgroup Process Using an Adapted Nominal Group Technique (NGT)

2.4.1. Distilling and Translating Information from TTC Narratives into Initial Pool of Recommendations: Adapted NGT Steps 1–2

For the first step in the adapted nominal group technique (NGT), generation of ideas, at least two of the three evaluation team members took notes based on the stories of the young adults, reactions from the participants, and answers to the follow up questions. The goal was to capture any information and responses that could be translated into policy and practice recommendations. For example, some truth tellers in this study reported that they were worse off after entry into foster care than before, even though their biological families had experienced extreme financial and caregiving challenges. The truth tellers reported that they would have preferred the state wrapped around services and resources to help their biological families keep them at home rather than removing them into foster care and using those funds to pay strangers to “care for them”. Youth experienced food deprivation as part of their experience in foster care even though foster parents are paid enough money to feed the children nutritious meals and snacks, such as being given freeze-dried noodle packages to eat while other members of the family ate more nutrient-dense meals. Some youth were forced to participate in religious denominations that were not their own and they did not want to participate in, and some missed their own churches or other faith communities when removed from family. Some of the young women were not allowed to use, nor were they given, the types of menstrual or hair styling products they needed and desired. Once the core team generated the initial list of 39 ideas for potential policy changes that would help address some of the harmful and dehumanizing aspects of the child welfare system described during this project, the evaluation team grouped the recommendations by service sector and system level. For example, some recommendations focused on policy changes at the federal or state legislative levels (e.g., redistribution of funds used to support foster families to instead support families in crisis to keep children with their parent(s)), while other recommendations focused on DCBS (Department for Community Based Services) policies and practices (e.g., train child welfare workforce in cultural humility and cultural practices; ensure all youth in foster care receive training and education to facilitate relationship skills and building a robust social network). For the second step in our NGT, sharing and clarification, during a core team meeting, the evaluation team explained the organization of the recommendations and provided clarifying information in response to questions.

2.4.2. Child Welfare System Recommendation Priorities Selection Process: Adapted NGT Steps 3–4

Consistent with guidance in the nominal group technique in healthcare literature [], the workgroup to select the team’s top recommendations for child welfare system practice and policy changes occurred over multiple meetings and intervening recommendation ranking, and included some input from collaborators external to the central workgroup at strategically timed points in the process. Specifically, after the initial presentation of the recommendations, the four young adult lived experts discussed these recommendations and their implications. Next, after the meeting, consistent with NGT step 4, ranking, each young adult selected their individual top 10 recommendations. At the second meeting, the Lived Experts reviewed the rankings together. Recommendations that appeared on 3 or 4 of the lived experts’ individual top 10 lists were automatically moved to the workgroup top 10 list. The workgroup then discussed the remaining recommendations that were on 1 or 2 of the lived experts’ individual top lists, with each lived expert advocating for 1 or 2 additional recommendations. Then, through discussion over text, email, and/or verbally, the workgroup selected the remaining top 10 workgroup recommendations based on their perceived feasibility. Subsequently, during a community partner team meeting, community partners provided input on the top 10 recommendations. At the third Lived Expert consensus workgroup meeting, the lived experts together reviewed this feedback and selected 3 top priorities. Then, these recommendations served as the basis for discussion with advocacy experts who joined and guided the core team and community partners in the process of discussing the feasibility of the recommendations. The entire core team also discussed the feedback with policy experts and community partners on the top 3 priorities. Those efforts led to the selection of one top priority that would be the next focus of future advocacy and funding efforts by the team (discussed in the Section 3 below).

3. Results

3.1. Truth-Teller Descriptions of Artwork

Each Truth-Teller Developed a Written Description of the Process and Purpose of Creating Their Artwork. These Descriptions Are Below.

Truth-teller description of Artwork 1, “Identity: Gained & Lost”: During the process of trying to decide which medium to present my artwork in, I attended an event where I met the artist and viewed some of her completed artwork, which she termed “selfie wreaths”. The idea and design for my artwork piece progressed from there. Both individuals worked together to create the artwork utilized during the project. I wanted the artwork to center on identity, the identity I gained and lost during my time in the Kentucky foster care system, and the lifelong impacts I still see and recognize resulting from those experiences. One of the critical themes I wanted to express in my artwork was my mixed-race identity (black and white) and the corresponding personal lens shaped by that identity, and how that shaped my foster care story. I utilized the above artwork to physically represent my spoken testimonial during the TTCs. Overall, I hoped to communicate through my art piece and spoken testimonial that everything is centered on identity, the identity we hold for ourselves, and the identity given to us by the world and others (foster care), and how that identity can shape a young person’s life both in their early years and beyond, and how that identity can be reimagined and centered in understanding of one’s self, healing, and the impact of taking charge over your identity.

Truth-teller description of Artwork 2, “System vs. Growth”: I chose this art form to represent the passage of time within the foster care system in a deliberately exaggerated and symbolic way. The piece reflects both personal individuality and the growth I have experienced throughout my journey. Through this format, I aimed to convey that, although every action and experience creates a ripple—like the butterfly effect—you can still trace the transformation over time. It’s a visual reminder that, despite being dealt a difficult hand, I have a future. And just as importantly, it affirms that those who come after me—other youth in care—have powerful, promising futures of their own.

Truth-teller description of Artwork 3, “Now or Never”: This piece is both music and testimony. I chose to share it because music is the most intimate and natural way I communicate. Among my many passions and abilities, music production has consistently been a defining strength. With Now or Never, I created a melodic rhythm and wrote lyrics that carry a living pulse—meant to move both body and mind—so that my testimony would feel engaging and alive. At its core, the song is a window into how I navigate love and relationships through choice rather than demand. It reflects the lessons of my journey: that even in loss or separation, there is room for compassion, gratitude, and forward motion. More than expression, Now or Never serves as evidence of truth-telling—a lived example of how vulnerability, shared openly, can guide growth, connection, and healing. Disclaimer: I originally collaborated with [studio name], a local recording studio, for this project. Due to a mismatch in the final product and my original vision, I made adjustments accordingly.

Truth-teller description of Artwork 4, “Cameron Galloway’s Story”: I chose this form simply because I’ve always wanted to do something like this. The more descriptive reasoning is because I wanted something permanent. I wanted something people could access from anywhere. I didn’t want to box my story up to only be told while I was present. Kids need to hear something when they are feeling down and doing this method was the best way. I wanted Impact and relatability with youth rather than speaking to adults. All in all I wanted something accessible for youth. Let’s eliminate the barriers and allow people to be impacted no matter their location or who may hold the key to the door of opportunity disadvantaged youth often don’t get access to. As a kid I needed a “person” who I could relate to and believe I could get through the dark times not a “professional” to tell me it’ll be okay. Show me and give me access to proof, I can make it through don’t just tell me it’s possible.

3.2. Collaborative Autoethnography Findings

3.2.1. Strengths

Finding 1: Lived Expert- and Community-Led. Overall, we viewed the process as being led by young adults with lived expertise in the child welfare system as well as a community-based organization that seeks to partner with and empower those transitioning out of the foster care system. The following quote from a professional core team member exemplifies this theme: “The young adults were centered throughout the process of developing their narratives about their time in the foster care system, they were supported every step of the way”.

A lived expert participant recounted that she was pleasantly surprised at the extent to which lived experts were partners and leaders on the project, “This project caught me off guard. The amount of focus on Lived Experts had surprised me. That is so important to me and I believe that by involving other individuals they will be able to see the positive impact of having Lived Experts not only at the table but also being the focus they will be able to shift that to their work as well”.

Another lived expert described how telling their stories through an art medium they each selected resonated with them and was empowering and freeing: “I think it was a chance to perfect our story…think it was an opportunity to create our story in a way in which we viewed it. Meaning, some people’s creativity was shown through legitimate art, picture, or even interview type of style. For me, mine was through the interview style as I view my life as a movie. So, looking deep into the avenue in which people told their stories you got to see how they viewed it based on their creative expression”.

Finding 2: Intentional and Collaborative Process. We also noticed the effort and attention paid to creating a brave, supportive environment for the lived expert truth tellers was something throughout the two years of the project. We described the care and time spent to preparing the Lived Experts to safely and authentically tell their stories, as well as to creating a sequence of activities and purposeful activities for the actual truth telling circles that promoted a brave space for the Lived Experts and prepared witnesses to be present and listen deeply as one aspect that stood out to us. This idea is represented in this excerpt from our responses: “The degree of preparation that occurred was evident. The young people spent so much time and attention curating their stories. I appreciated how [Lived Expert 1] adapted his testimony from Day 1 to Day 2. I also appreciated the decompression space that was provided for the young people as well. The value cards were helpful in grounding all participants”.

In addition to the intentional preparation of the truth tellers, we also described the intentional selection of witnesses. This sentiment is expressed in the following quote, “The participants [witnesses] were hand-picked and turned out to be trustworthy given their reactions to the young adults. Everyone felt inspired yet also ready to make actions happen to change the system (or replace it with family support).” Not only did we report appreciating the intentional process of selecting witnesses, but we also observed the hand-picked group to appear to be engaged and moved by what they heard.

Another aspect of the process that we appreciated was the effort to be collaborative across the project phases. For example, the lived expert who co-led the project during Year 1 said the following, “I did all I could to ensure the process flowed and it did. I wanted to make sure that with everything going on and everyone’s lives we could all contribute in the allotted timeline that was given.” Similarly, another lived expert described the collaboration that took place during the planning process for the first TTC in Year 1, “The project overall, and particularly this phase [preparation and planning], was very collaborative. I loved the shared decision-making that took place and valued having so many people with varying levels of experience with TTCs together at one table. While the collaborative nature of this phase caused things to move a bit slower, I think it was really important to ensure that the TTCs themselves were quality.”

Finding 3: Immediate, Powerful, and Transformative Impact. We also saw the truth telling initiative activities as affecting the core team, community partners, and witnesses in a way that was immediate, palpable, and unique. A professional member of the core team described the impact on her in the following way, “I thought they were transformational. I’m still affected by what was shared during the young adults’ testimonies. Those details were important truths, about the foster care system, that needed to be heard by those of us who were witnesses”.

A lived expert described the meaningfulness of participants witnessing her story, “I felt honored to share my story by people saying ‘sorry that happened to you, it was not okay or your fault’. Even at 27 hearing that meant more than I thought it would. Hearing those hard truths are hard and normally people try to downplay it for their own comfort and having to sit with it and experience our truth in such an impactful way was great”.

In terms of impacts on witnesses and community partners, we perceived that exposing them to personal experiences and data about Black children in the child welfare system was an important outcome. One lived expert described informing the community as an important output, “Education was the best thing about it. The community wasn’t fully educated on the system; I believe TTC allowed the community to be updated and educated on the truth from the youths perspective and from the standpoint of trying to change a system”.

A professional member of the core team remarked on a case worker stating that hearing the testimonies had an impact on her practice, “I was so touched to hear a case worker say during a community partner meeting that because the young adults talked about the importance of including youth in decisions about placement changes that shortly after she attended a truth telling circle she made it a point to ask a child on her caseload for his preferences about where he should move next. Just that one shift, felt like a positive tangible outcome of this process”.

A professional member of the core team described the importance of the charrette in particular as a vehicle for community education, “The reaction and engagement of attendees, foster care system alumni as the MC, the lived expert panel…completion and sharing of our work/report, and the self-care stations were things I thought went well. I also was happy we were able to educate more people about the foster care system”.

Finding 4: Striving for Action. At the same time, we saw the value of our attempts to not only raise awareness and educate the community, but to also translate the wisdom shared through the truth telling into recommendations for policy and practice changes. At the end of Year 1, we expressed hope for being able to plan and implement an advocacy plan through an additional year of funding. One team member expressed this idea in this way, “Hearing the raw testimonies really put things into perspective. Especially seeing the similarities in the testimonies revealed to me that there are consistencies that I think we have the power to help change”.

In addition, we mostly saw the policy campaign advocacy strategies training as positive. “I enjoyed getting everyone in the room and being able to get clear instructions on “what now” with speaking on the results of the TTC”.

3.2.2. Challenges

In addition to the many strengths and positive aspects of the TTC initiative we experienced, we also experienced some difficulties. These difficulties included both shortcomings or obstacles to carrying out planned activities and also some unanticipated individual and interpersonal difficulties.

Finding 1: Not Enough Time and Structure for Some Activities. We thought some activities, notably the process of generating policy and practice recommendations and advocacy campaign development, needed more focused time to be optimally effective and without this, this phase felt rushed and disorganized without a clear path forward for prioritizing recommendations or who should carry them out. This sentiment is exemplified in this quote about the initial workgroup process that occurred during Year 1, “If we had more time to process the list [in Year 1], perhaps together in a room with a process to group and prioritize them (e.g., use a dot exercise) that might have helped us come to more agreement in the end”.

Additionally, a Lived Expert described being disappointed with community partner team meetings, particularly during year two of the project, because they did not seem to have a clear goal or lead to a specific product. She stated, “They did not feel very intentional or impactful. I think these need to be much more structured and intentional, with tangible results coming out of each one. It felt like I/we were just spinning our wheels and meeting checkmarks”.

Finding 2: Team Turnover. We described the difficulties encountered with consistency in both truth teller and professional staff engagement, from the Year 1 planning phase through to the Year 2 final policy/practice recommendations meetings. For example one team member described, “We all know we had 2 young adults who did not share their testimony at the truth telling circle. We had planned to have six, ended up having four…[we] still invited everybody to attend and participate and all that type of thing, even if it was in a different role. I think that that did add some complications… We did it but it kind of changed the direction we were going in”.

A Lived Expert described her disappointment at being the only truth teller at one of the TTCs, “As the sole participant of the second TTC [in Year 2] I do not think this should be done with less than 4 youth, but especially not only one”.

Changes in professional staff personnel was an additional unexpected challenge that was particularly impactful on the lead community organization. This was described in the following manner: “We had admin support at the beginning of this grant and for a good while and then…after several months of having admin. help on this grant, the staff was no longer employed at [Grant Recipient Site] and that greatly impacted on the back side the work… So, I definitely think that staff change impacted the ability to carry it out”.

Finding 3: Emotional Distress. We also perceived that despite the deliberate and conscientious planning, some Lived Experts experienced short-lived emotional reactions and distress during the TTC activities as described in this quote, “you know normally do not cry because you know I do this work a lot. But the second day [TTC] did kind of surprise me when I shared something as I was having a little bit of an ‘Aha” moment. I didn’t realize what exactly upset me about it until I was basically describing it during the TTCs…. That was a little of an unexpected for me, how heavy that would be”.

Another lived expert described a time she felt frustrated during a Community Partner team meeting that was focused on selecting practice and policy priorities. During the core team debrief session that occurred directly after the meeting, she and another Lived Expert reported feeling that the conversation did not sufficiently emphasize their preferences. However, she described that, despite the difficult group process, there were some positive effects of the meeting, “Despite my reaction, I think it was necessary. Regardless of the outcome, we received a lot of necessary information. We were also able to learn from that experience and make adjustments moving forward which I think has proved to be more successful”.

This lived expert saw changes the core team made as a consequence of the meeting as providing some recompense for the difficulties experienced. The adjustments we agreed on to prevent a similar process from occurring were to only involve smaller numbers of individuals in advocacy planning meetings, and also only those individuals who have a positive, solution-focused orientation toward working for large-scale system change.

Finding 4: Limitations in Group Cohesion and Interpersonal Difficulties. We also described some differences in priorities with regard to project goals and structure, across team members, that became evident and remained somewhat unresolved. The following quote illustrates this difficulty, “Hammering out the actual invite list to where I felt comfortable…was a big hurdle for me… We could have done a better job [sic] of finalizing that list earlier on so that we first off made sure to target all the people that we wanted to target and second of all made sure there weren’t any surprise individuals to where we had any anxieties leading into the groups or the TTCs”.

Another team member described the differences in viewpoints across the team in the following way, “As much as we did communicate and as many meetings as we had, there was still times that there wasn’t clarity in some pieces”.

In addition, one team member reported significant interpersonal and inter-organizational conflict toward the end of Year 2. This truth teller, after an ongoing conflict, was eventually separated from the project and subsequently described feeling disrespected and betrayed, partly because, in her view, she contributed more than others to the project:

I did not like the fact that the adult participant who structured the entire event [the Charrette] and put in the most work over the two years of this grant did not receive an invite and was barred from coming to the event. I deserved to be there, and without mincing words, it was beyond disgusting that people barred (and allowed others to barr me) from attending an event that was a result of two years of my work/life story. As a black youth, it raises a lot of concerns that this grant work is “working” to eradicate, which takes away from the credibility of this work and creates a hypocritical lens to the work over the last two years.

Finding 5: Emergent Concerns about Complacency and Intransigence of the Child Welfare System. In the latter half of Year 2, as we reflected on, discussed, and analyzed our experience of the TTC initiative process, particularly obstacles we encountered, some worries emerged among the core team about potential complacency within the broader community and child welfare system workers with the status quo of youth involved in the child welfare system. For example, we also expressed some concerns about, among child welfare industry representatives, the gap between expressing sympathy for the experiences of Black youth in the foster care system and attempting to actually change the system. This sentiment is expressed in the following anecdote:

At the end of the circle process…she [a child welfare system administrator]…said absolutely what the truth tellers would want to hear—that their testimonies were compelling and it made her think about what influence she had to make change. But then in private, she made what I would consider a flippant and almost callous comment, when she said, “I’ve heard this all before; there’s nothing new”. With that comment, I knew that even with a highly curated group of participants who the team thought would not only be receptive but perhaps influential, that truth telling processes are wrought with complexities that I hadn’t fully thought through. She—like so many others in the child welfare industry—have built their entire professional and in some cases personal identity and image around protecting children. So, processes and conversations that confront some of the hard truths of the industry are too painful to really digest or ingest—it becomes too personal. The industry is a self-protecting organism…She was walking away as a highly compensated executive whose company benefits when children are in “care”.

Also, the Lived Expert who was separated from the grant prematurely expressed frustration with the core team potentially not being strategic enough in involving the right decision-makers who might influence child welfare system practice and policy and lack of clarity around sought changes, “[Community partner and member witnesses were impacted] potentially positively if the right community partners would have been selected and closely monitored. What has changed because of this grant? Where are the tangibles? The entire essence of what a TTC is was trampled and spit on; if there are no tangible results from storytelling in this manner, then it is another form of abuse and user behavior”. In the view of this Lived Expert, lack of broadly-known, concrete changes after truth-telling equates to exploitation of the truth tellers.

3.3. Consensus Workgroup: Adapted Nominal Group Technique

Finding 1: Top 10 Recommendations. The Top 10 Recommendations for child welfare policy and practice developed through the lived expert consensus workgroup process are in Table 1 below (the initial pool of 39 recommendations can be found in the Appendix A). Additionally, the workgroup identified a top priority for the team’s advocacy efforts and as the focus for applying for subsequent funding which amounted to an integration of recommendations #4 and #10: Providing evidence-informed financial support and case management to birth parents for the purpose of keeping Black families intact and Black youth out of the foster care system.

Table 1.

Top 10 Recommendations from Louisville TTCs for Child Welfare System Practice and Policy Changes.

4. Discussion

This study examined a pilot initiative to develop and implement a complex, localized truth-telling initiative about the Kentucky child welfare system. With the support of organizational partners and researchers—and co-led and designed by a lived expert and an advocacy-focused professional—the initiative employed strategies rooted in the PAR concepts of collaboration and being conversation-driven []. Its design intentionally embedded truth-telling principles and practices that moved beyond storytelling toward collective action and systems change, consistent with PAR [,]. Given that this truth-telling initiative was co-led and designed by former foster youth as an important lever of the power-sharing process, and was not commissioned by a national, state, or tribal government, it represents a novel and potentially unique approach. Few comparable efforts exist in the literature or in practice, particularly those that attempt to center the leadership of system-impacted individuals in such a sustained and structured way.

Our study of this initiative utilized two methods: a collaborative autoethnography to examine our experiences as a core team of this project and an adapted nominal group technique process to generate policy and practice recommendations for the child welfare field based on the lived experts’ experiences. The first set of findings from the collaborative auto-ethnography were our descriptions of positive aspects of the TTC-Louisville project. We described our appreciation of the intentional cultivation of respectful, supportive relationships among the core team, consisting of both lived experts and individuals acting in a professional capacity, and the emphasis on relationship building and shared decision-making. This finding is similar to the finding that co-regulation, or interpersonal interactions in which two or more people experience interconnected calming of their nervous systems, reduced distress, and acceptance, can be beneficial to youth transitioning out of the child welfare system. Co-regulation is suggested to be beneficial to youth self-regulation, educational achievement, and identity development []. In addition, the lived expert truth tellers described how meaningful and beneficial it was to have others bear witness to their experiences. This finding is similar to other accounts in the literature of the healing power of telling one’s story, in particular when related to traumatic events, which can provide a sense of coherence, understanding, and reclaiming agency [,].

Related to the second set of collaborative autoethnography findings, pertaining to challenges of carrying out the TTC-Louisville project, although extra efforts were made to safeguard the well-being of the truth-tellers throughout the truth telling planning process and circles, some truth tellers experienced some emotional distress. This was not only related to the truth telling circles, but also a result of challenging group dynamics amongst the broader team. Also, it was unclear the extent to which witnesses were going to use the testimonies and their positional power to implement changes in child welfare practice or policy after leaving the truth telling circles. In addition, the efforts to transform truths shared into practice and policy recommendations were more prolonged and met more resistance than we anticipated. While this process didn’t lead to immediate demonstrable changes as hoped or envisioned by the truth tellers, this is an important lesson for others designing or implementing truth telling processes–that is, while preparing and holding truth telling circles are of critical importance, it is essential to budget time and resources to translate narratives into action.

In addition, our adapted nominal group technique process resulted in practice and policy recommendations based on the lived experience of four emerging adult alumni of the foster care system in one state. Some recommendations, such as ensuring non-pathologizing language is utilized in case documentation and ensuring all children and youth entering care name and have access to a minimum of three adults they want to stay in touch with during their time in out-of-home care, may have relevance for child welfare systems in other jurisdictions. In addition, some generated recommendations are consistent with recent findings related to the feasibility and acceptability of evidence-based programs, such as on healthy relationship skills, such as Love Notes, or coping with emotional distress, such as Mind Matters, among youth in the foster care system [,,]. Such skills may be particularly relevant to assisting youth in out-of-home care as they transition to adulthood.

The top recommendation chosen by the lived experts was related to preventing unnecessary child welfare system involvement by helping families meet unmet basic needs. This recommendation is consistent with an increase in attention over the past decade to the importance of prevention of child neglect and the need for families to come into contact with child welfare agencies with a move to find ways to enhance support for families so that they and their children can thrive [,]. In particular, the Opt-In program, supported by the Doris Duke Foundation, is working in three states, including Kentucky, to ensure families have the economic support needed to avoid child welfare involvement (https://www.ddf-opt-in.org/ accessed on 15 July 2025). In addition, the Kentucky legislature passed a revision to its child abuse neglect statute in 2022 to remove signs of poverty as indicators of child neglect so that centralized intake units and investigators do not substantiate neglect if the only issues facing a family are due to being in poverty (KRS 600.020) []. While these are promising steps, laws and policies will need to be passed which prioritize family well-being as part of support for children and seek to strengthen systems that address other areas that can interfere with parenting such as behavioral health coverage for mental health and substance use disorders.

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

This study evidenced several strengths. We carried out a longitudinal qualitative study with a team of lived experts and practice and research professionals in the child welfare system of a truth-telling initiative. Longitudinal qualitative studies can lead to deeper understandings of the experiences of participants, as well as change in perspectives over time, compared to cross-sectional studies []. In addition, the truth-telling project examined was reported by participants as having several characteristics emblematic of lived expert/community-researcher collaboration, including structures to enhance shared decision-making and planning related to TTCs, community partner meetings, and broader community events. The collaborative autoethnography method allowed for multi-vocal reporting of experiences across lived expert, practitioner, and evaluator members of the core team allowing for an examination of the initiative from multiple perspectives. In addition, the lived experts prioritized active engagement of all four of them, through multiple meetings and modes of communication (e.g., text, email, in-person), to build consensus for their prioritized recommendations.

Despite these strengths, this study was not without its limitations. A major goal of the TTC initiative from the outset was to inform discussions of policy and practice change. However, as some of the stories recounted events that had happened 5 to 10 years prior to the TTCs, some of the dynamics reported were not completely reflective of the contemporary child welfare context. For example, some of the Lived Experts reported having no or very limited opportunity to give input on permanency planning, and thus one of their top 10 recommendations was to require caseworkers to solicit and document youth preferences for permanency planning. In comparison, currently, the standard operation procedures in the child welfare system in Kentucky include documenting youth preferences for permanency goals. Future projects also may benefit from determining in advance what strategies will be used to address disagreements among team members.

Although we do not consider our use of collaborative autoethnography—a post-modern methodology focused on shared reflections—a limitation, we acknowledge that the study did not yield findings that are reproducible or generalizable. This contrasts with studies employing larger samples and quantitative methods that allow for the examination of changes over time. Additionally, one lived expert core team member was only retained in the two-year project for one year, and a second lived expert member was retained in the project for one year, nine months. Although these lived experts co-authored this paper, they could only report on their experiences for the partial time they were involved in the initiative, thereby limiting to some extent the comprehensiveness of their reflections on the project.

4.2. Implications and Conclusions

Findings from this study also suggest potential implications for future truth telling initiatives. One major consideration is providing financial means to help meet basic needs, overcome logistical hurdles, and mental health support for truth tellers. In addition, preparation of the truth tellers for potential emotional distress they may experience during the process, which may in the end be experienced as positive overall and may be experienced as a mix of positive and negative for others, is critical. Strategies for truth tellers to monitor their own emotional reactions throughout the process of creating and telling truths should be shared during the process of creating narratives, and truth tellers should be reminded of these strategies often throughout the duration of a truth-telling project. Because of the complexity and obstacles that can be faced in planning and implementing actions, from the outset, time and structures should be set aside to allow for thorough and iterative planning of actions. Relatedly, our study revealed some disconnect between advocates and Lived Experts, on the one hand, and child welfare system and industry professionals, on the other, related to the pace and magnitude of system changes that should be sought. Given their lived experiences and in recognition of the harms that some expressed experiencing in foster care, the Lived Experts in our study felt a great sense of urgency to make bold changes in the system. Their enthusiasm was met in some cases with caution, lukewarm reception, and criticism regarding the likelihood that their top recommendation could be the focus of a successful advocacy campaign.

Future truth telling efforts should consider sharing information about the typical scope and speed at which systems-level changes may be made during the recruitment of potential truth tellers so they can determine how and if they want to share their testimonies. In addition, given there was a gap in time between the lived experts’ experience in the child welfare system and when they prioritized recommendations, future studies could involve iterative rounds of information provided to lived experts such that first potential recommendations are generated directly from their experienced gaps in care, and then relevant updates in policy and practice given to the lived experts, such that their prioritized recommendations can then be refined to best reflect a combination of their experience and current practice. For example, the use of tools that have been developed in the community-based participatory research literature would also help buttress efforts to authentically share power, such as materials developed for having transparent, team-based conversations about conflict management, financial rearrangements, scope of work for each partner, and processes for individuals and organizations entering and leaving collaborative projects [,]. When truth-telling is organized by a third-party outside of truth-tellers themselves, truth-tellers must be engaged as equal partners in determining the stipulations of contracts regarding the use of their narratives and any associated artifacts (e.g., pictures of artwork). Another set of potential truth tellers who could be engaged in truth telling initiatives are the people who work within the child welfare industry. There is an increasing emphasis on moral injury among those who work in child welfare systems [], and, moreover, those working within or tangentially with the system may be in a better position to make changes to the bureaucratic architecture.

In this project, members of a trans-experiential team found an arts-based truth telling initiative to raise awareness about the experiences of Black American youth in the child welfare system in one state, found that the project, in general, strived to collaborate with young adult lived experts and that the connections among the team, and between the team and other community partners, were particularly meaningful. This finding is resonant with theoretical and empirical work finding that key Black American cultural values include collectivism and interdependence [,]. Future efforts to support Black American youth in the child welfare system transition to adulthood may also benefit from harnessing the validating and potentially healing power of relationship and group-based interventions. Such efforts also could naturally help expand and buttress the social capital of Black American youth, another asset important for the transition to adulthood. Overall, despite some challenges and weaknesses of the project, an arts-based truth-telling initiative seemed to be a promising intervention to help support youth with child welfare lived experience transition to adulthood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.-H., E.D., L.M.-H., A.B.; methodology, E.S.-H., A.B., C.A., E.D.; formal analysis, E.S.-H., C.A., N.T., A.B., G.W., T.H., C.G., E.D.; resources, N.T., E.S.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-H., L.M.-H., A.B., N.T., G.W., E.D., C.A.; writing—review and editing, E.S.-H., L.M.-H., N.T., A.B., G.W., E.D.; visualization, E.D., G.W., C.G., T.H.; supervision, E.S.-H.; project administration, N.T., E.D.; funding acquisition, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and Prevent Child Abuse America to Kentucky Youth Advocates.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable; all participants were also researchers and therefore IRB review was not needed.

Informed Consent Statement

All participant-researchers gave permission for their data to be used in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

As the data in this project were qualitative from n = 9 participant-researchers, for confidentiality reasons, the data are not available.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Dawson, who was contracted not only to help streamline the Truth Telling Circle design process during Year 1, but really put the power in the hands of the young adult experts. In addition, we are grateful to Wright & Hunter Consulting, who provided invaluable consultant services as trainers and coaches in this work. We also wish to thank Munnik Creations, Shawn Wright, Kaden Gunn, Timothy Bowen, and Mary-Rachel Starnes, who provided technical and artistic expertise to bring the vision of the truth tellers to fruition. We also would like to thank L.J. Mouton, who provided logistical assistance on the project as both a practicum student and later as an unpaid volunteer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. Author Eltuan Dawson was employed by the company Blackstone Academic Group LLC. (B.A.G.), Glenda Wright was employed by the Wright & Hunter Consulting. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations