Abstract

Endoperoxides constitute a distinctive class of highly oxygenated terpenoids defined by the presence of a cyclic peroxide (–O–O–) bond, a structural motif responsible for their pronounced chemical reactivity and diverse biological effects. Naturally occurring endoperoxide-containing terpenoids are broadly distributed across terrestrial and marine taxa, including higher plants, algae, fungi, and bryophytes, where they are believed to participate in chemical defense and ecological interactions. This review provides a comprehensive overview of naturally occurring endoperoxide terpenoids, focusing on their natural sources, structural diversity, and reported biological activities. Particular emphasis is placed on compounds exhibiting antiprotozoal and antitumor activities, exemplified by artemisinin and its derivatives, which remain cornerstone agents in antimalarial therapy and continue to attract interest for their anticancer potential. Structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis, supported by computational prediction using the PASS (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances) platform, is employed to examine correlations between peroxide-containing frameworks and biological function. Comparative assessment of experimental data and predicted activity profiles identifies key structural features associated with antiprotozoal, antineoplastic, and anti-inflammatory effects. Collectively, this review highlights endoperoxides as a valuable and chemically distinctive class of bioactive natural products and discusses their promise and limitations as leads for further pharmacological development, particularly in light of their intrinsic reactivity and stability challenges.

1. Introduction

Highly oxygenated terpenoids are a diverse class of terpene-derived natural products characterized by the presence of multiple oxygen-containing functional groups, including hydroxyl, carbonyl, epoxide, and peroxide moieties. Depending on their carbon framework, these compounds are commonly classified as mono-, di-, or triterpenoids and are widely distributed in plants, fungi, algae, and other organisms. Their elevated oxygen-to-carbon ratio contributes to pronounced chemical reactivity and underlies a broad spectrum of biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, antiallergic, and antiparasitic effects [1,2,3,4,5].

Among highly oxygenated terpenoids, endoperoxides represent a particularly important subgroup. These compounds contain a peroxide bond (–O–O–) embedded within a cyclic structure, typically forming five- or six-membered rings. The peroxide linkage is intrinsically weak and highly reactive, rendering endoperoxides prone to redox transformations and homolytic cleavage. As a result, endoperoxide-containing molecules play a central role in oxidative stress–mediated biological processes and exhibit remarkable pharmacological properties [6,7,8,9]. Natural endoperoxides are predominantly found in terrestrial plants, fungi, algae, and marine organisms [5,6,7,8,9,10].

The most prominent example of a biologically active endoperoxide is artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Artemisia annua. Artemisinin and its semi-synthetic derivatives, including artesunate and artemether, constitute the cornerstone of modern antimalarial therapy. Their mechanism of action involves activation of the endoperoxide bond by ferrous iron (Fe2+) within the malaria parasite, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species and carbon-centered radicals that damage essential parasite biomolecules [11,12,13,14,15].

Another biologically significant class of endoperoxides includes prostaglandin endoperoxides, such as PGG2 and PGH2, which are key intermediates in prostaglandin biosynthesis from arachidonic acid in animals. These molecules are produced through cyclooxygenase (COX)-mediated oxidation and are central regulators of inflammation, pain, fever, and vascular homeostasis. The pivotal role of prostaglandin endoperoxides explains why COX enzymes are major pharmacological targets of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin and ibuprofen [16,17,18].

Beyond antiparasitic and inflammatory pathways, both natural and synthetic endoperoxides have attracted increasing attention as potential anticancer, antibacterial, and antiviral agents. Their biological effects are largely attributed to their ability to generate reactive oxygen species and induce oxidative damage in target cells [5,9,19]. However, the high reactivity of endoperoxides also poses challenges, as these compounds may exhibit limited stability under thermal or photochemical conditions, leading to uncontrolled radical formation and potential toxicity [1,9,10,20,21,22].

This review focuses on the biological activities of naturally occurring endoperoxides derived from algae, mosses, and higher plants, with particular emphasis on their anticancer and antiprotozoal potential, chemical diversity, and mechanistic aspects of action.

2. Distribution in Nature

Natural products containing rare five-membered endoperoxide rings have been identified in a limited but chemically diverse range of organisms, primarily higher plants, mosses, and medicinal herbs [14,23,24]. These compounds are of particular interest due to the structural strain and high reactivity associated with cyclic peroxide motifs.

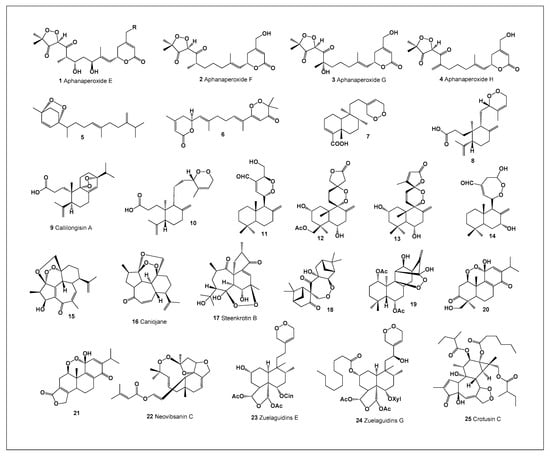

Aphanaperoxides E (1), F (2), G (3), and H (4) were isolated from the stem bark of Aphanamixis polystachya [25]. Their chemical structures and biological activities are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1. In addition, a peroxide-containing compound (5) was obtained from Artemisia absinthium, while nemoralisin G (6) was isolated from Aphanamixis grandifolia (Figure 2) [26].

Figure 1.

Illustrates representative bioactive endoperoxide-containing terpenoids isolated from algae, mosses, and higher plants, highlighting both their taxonomic diversity and structural complexity. Despite originating from phylogenetically distant organisms, these metabolites share a defining cyclic endoperoxide (–O–O–) moiety, underscoring the convergent evolution of peroxide-based chemical defenses across terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. In algae and bryophytes, endoperoxides are often associated with ecological functions such as allelopathy, anti-predatory defense, and protection against microbial colonization, whereas in higher plants they are frequently linked to defense against herbivores and pathogenic microorganisms. Structurally, the compounds shown in Figure 1 encompass a wide range of terpenoid frameworks, including sesquiterpenes, diterpenes, and triterpenes, with the endoperoxide bridge embedded within rigid polycyclic scaffolds. This structural constraint is critical, as it governs the three-dimensional orientation and reactivity of the peroxide bond, directly influencing biological activity. Many of the depicted molecules exhibit pronounced antiprotozoal, antitumor, or anti-inflammatory activities, which are mechanistically associated with peroxide activation under reductive or iron-rich biological conditions, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species or carbon-centered radicals. Collectively, Figure 1 emphasizes that bioactive endoperoxides are not confined to a single biological lineage but are widespread across algae, mosses, and vascular plants. Their shared structural motif, coupled with diverse peripheral functionalization, provides a valuable framework for structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis and highlights these natural products as privileged scaffolds for the development of new antiparasitic and anticancer agents.

Table 1.

Biological activities of endoperoxides derived from plants.

Figure 2.

Representative plant sources of naturally occurring endoperoxides. (a) Aphanamixis polystachya (Meliaceae), native to South and Southeast Asia, widely used in Ayurvedic medicine with reported anticancer, antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. (b) Schistochila acuminata (Schistochilaceae), a liverwort adapted to shaded, moist habitats, characterized by deeply dissected leaves. (c) Amphiachyris amoena, an annual wildflower endemic to central Texas (USA), traditionally used for digestive, dermatological, and febrile conditions. (d) Premna oligotricha, an aromatic shrub distributed in East and Southeast Asia and parts of East Africa, employed in traditional medicine for malaria, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and cardiovascular disorders. All images were obtained from sources permitting non-commercial use.

A clerodane-type peroxide (7) was discovered in the liverwort Schistochila acuminata [27], an example of which is shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, two labdane-type peroxides (8 and 10) were identified in Croton stipuliformis [28]. From Callicarpa longissima, callilongisin A (9) was isolated and demonstrated pronounced anti-inflammatory activity [29].

Additional labdane-derived endoperoxides have been reported from various plant species. A labdane diterpene peroxide (11) was isolated from Alpinia chinensis [30]. Amphiachyris amoena yielded amoenolide K (12), while Premna oligotricha produced an ent-labdane peroxide (13). Another related compound, 7β-hydroxycoronarin B (14), was found in both Hedychium coronarium and Actinidia chinensis.

The flowering plant Jatropha integerrima afforded 2-epi-caniojane (15), whereas the roots of Jatropha curcas yielded caniojane (16) and steenkrotin B (17), the latter exhibiting mild antiplasmodial activity [30]. In addition, a highly potent antimalarial endoperoxide (18) was isolated from Amomum krervanh [31], underscoring the therapeutic relevance of naturally occurring peroxide-containing terpenoids.

Jungermatrobrunin A (19), isolated from the liverwort Jungermannia atrobrunnea, possesses a distinctive peroxide-containing molecular architecture [32]. Triptotins A (20) and B (21) were obtained from Tripterygium wilfordii [33], a representative specimen of which is shown in Figure 1 Neovibsanin C (22), isolated from Viburnum awabuki, represents a rare structural class of diterpene endoperoxides [34]. In addition, Zuelania guidonia yielded zuelaguidins E (23) and G (24) [35], while crotusin C (25) was isolated from Croton caudatus [36].

Analysis of the biological activities summarized in Table 1 reveals that, among the 25 naturally occurring endoperoxides discussed, only compound 14 (7β-hydroxycoronarin B) exhibited strong antineoplastic activity. In addition, this compound demonstrated moderate antiprotozoal activity against Plasmodium species. In contrast, strong antiprotozoal activity was observed for six compounds (11, 15, 16, 18, 19, and 22). Among these, only three compounds—11, 19, and 22—displayed moderate antineoplastic activity as a secondary effect, whereas compounds 15, 16, and 18 showed only weak antineoplastic activity.

From a pharmacological perspective, compound 14 (7β-hydroxycoronarin B) emerges as the most promising candidate for further investigation due to its pronounced antineoplastic potency. Among the endoperoxides with strong antiprotozoal activity, compound 15 is noteworthy, although its antineoplastic activity remains limited. These findings highlight the potential of specific peroxide-containing terpenoids as selective leads for either anticancer or antiprotozoal drug development.

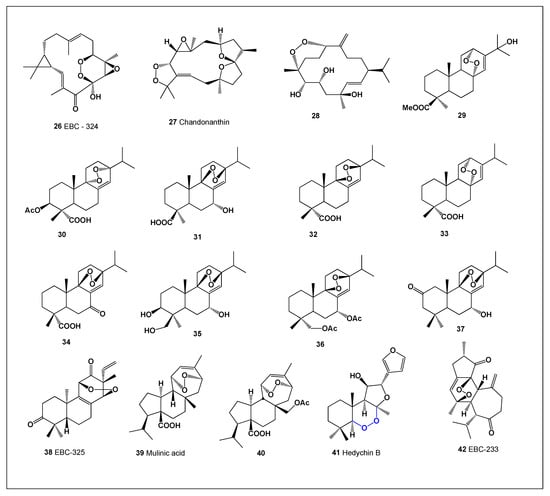

Compound 26 (Figure 3), with its biological activity summarized in Table 2, was isolated from the aerial parts of Croton insularis [37]. Another peroxide-containing metabolite, chandonanthin (27), a cembrane-type terpenoid, was identified in the ethyl acetate extract of the liverwort Chandonanthus hirtellus [38]. In addition, a cembrane endoperoxide (28) was isolated from the flowers of Greek tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), a representative specimen of which is shown in Figure 4 [39].

Figure 3.

Bioactive diterpenoid endoperoxides derived from algae, liverwort and plants.

Table 2.

Biological activities of endoperoxides derived from algae and plants.

Figure 4.

Representative plant sources of naturally occurring endoperoxides. (a) Tripterygium wilfordii (thunder god vine), a perennial vine used in traditional Chinese medicine, rich in bioactive diterpenoids and triterpenoids with immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activities, though associated with notable toxicity. (b) Zuelania guidonia (syn. Casearia laetioides), a shrub or small tree native to the Caribbean and Central America, traditionally used medicinally and as food, and known to produce peroxide-containing terpenoids. (c) Croton caudatus, widely used in Southeast Asian ethnomedicine for liver, febrile, and inflammatory disorders; its extracts show cytotoxic activity against cancer cell lines. (d) Nicotiana tabacum, a globally cultivated Solanaceae species with historical medicinal uses; its leaves contain alkaloids and terpenoids applied in traditional treatments for inflammatory and dermatological conditions.

The methyl ester of a diterpenic acid (29) was obtained from the leaves of Juniperus thurifera and J. phoenicea [40], while several structurally related diterpenic acids (29–31) were subsequently identified in extracts from other plant species. Notably, compound 27 was also isolated from Salvia oxyodon [41], indicating a broader taxonomic distribution.

Among these compounds, endoperoxide 27 is particularly noteworthy, as it exhibited strong antineoplastic and antiprotozoal activities, a rare and highly desirable combination for peroxide-containing natural products. Its three-dimensional molecular structure is presented in Figure 5, providing structural insight into its pronounced dual bioactivity.

Figure 5.

Additional plant sources of naturally occurring endoperoxides. (a) Elodea canadensis, a submerged freshwater plant native to North America, inhabits slow-moving waters and exhibits strong allelopathic activity through the release of bioactive secondary metabolites. (b) Lepechinia caulescens, an aromatic perennial native to the Americas and Hawaii, produces essential oils with pronounced antibacterial activity, including bactericidal effects against Vibrio cholerae. (c) Abies marocana, a critically endangered conifer endemic to the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, yields seed and needle extracts traditionally used for respiratory ailments and in perfumery. (d) Caryopteris nepetaefolia, an East Asian Lamiaceae species valued ornamentally, is rich in terpene-based volatile metabolites responsible for its eucalyptus-like aroma.

Abietic acid–derived endoperoxides (28–31) have been reported from several plant species, including Abies marocana, Elodea canadensis, Lepechinia caulescens, and Caryopteris nepetaefolia (a representative specimen is shown in Figure 5) [41,42,43,44,45,46]. Two closely related abietane-type endoperoxides, compounds 32 and 33, were isolated as acetate derivatives from the cones of Cedrus atlantica [47]. Croton laevigatus yielded crotolaevigatone G (34), while Croton insularis was the source of two additional endoperoxide-containing metabolites, EBC-325 (35) and EBC-233 (42) [48,49]. Furthermore, two diterpenoid acids, mulinic acid (36) and isomulinic acid (37), were isolated from Mulinum crassifolium [50].

A structurally unique peroxide-containing compound, hedychin B (41), was isolated from the rhizomes of Hedychium forrestii [51]. This compound exhibited pronounced cytotoxic activity against HepG2 and XWLC-05 cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 8.0 and 19.7 μM, respectively.

Analysis of the biological activities of the endoperoxides summarized in Table 2 revealed several notable trends. Compounds 27, 28, 35, and 37 demonstrated strong antineoplastic activity, whereas compounds 27, 41, and 42 showed strong antiprotozoal activity. Unexpectedly, three compounds—33, 39, and 40—exhibited strong anti-inflammatory activity in combination with moderate antiprotozoal and antineoplastic effects.

Anti-inflammatory (antiphlogistic) activity describes the capacity of a compound to suppress or modulate inflammatory responses, which are complex physiological processes involving immune cells, cytokines, prostaglandins, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Inflammation underlies a wide range of acute and chronic pathological conditions, including autoimmune disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular dysfunction, and cancer. Consequently, anti-inflammatory agents represent one of the most important classes of therapeutic drugs, accounting for approximately half of all clinically used analgesics [7,8,9,10].

Endoperoxide-containing natural products displaying anti-inflammatory activity are of particular pharmacological interest because their mechanisms of action often differ from those of conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Rather than acting solely through cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition, many endoperoxides exert their effects by modulating redox-sensitive signaling pathways, suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukins, or interfering with transcription factors including NF-κB and AP-1. The presence of the peroxide (–O–O–) moiety is thought to play a critical role in these processes, as it can undergo controlled activation in inflammatory microenvironments, leading to localized generation of reactive species that selectively modulate immune signaling [10,11,12,13,14,15].

From a structure–activity relationship (SAR) perspective, anti-inflammatory endoperoxides often possess rigid terpenoid frameworks that stabilize the peroxide bridge and enable selective interaction with cellular targets. Subtle variations in ring size, oxidation pattern, and stereochemistry can markedly influence potency and selectivity, highlighting the importance of three-dimensional molecular architecture. Notably, several natural endoperoxides exhibit anti-inflammatory activity at micromolar or submicromolar concentrations while displaying reduced cytotoxicity compared to classical anti-inflammatory agents [1,5,7,10].

Overall, the prevalence of anti-inflammatory activity among natural endoperoxides reinforces their pharmacological relevance and supports their continued investigation as alternative or complementary leads to existing anti-inflammatory drugs. Their unique redox-driven mechanisms, combined with structural diversity derived from algae, bryophytes, and higher plants, position endoperoxides as promising scaffolds for the development of next-generation analgesic and anti-inflammatory therapeutics [1,3,8,12].

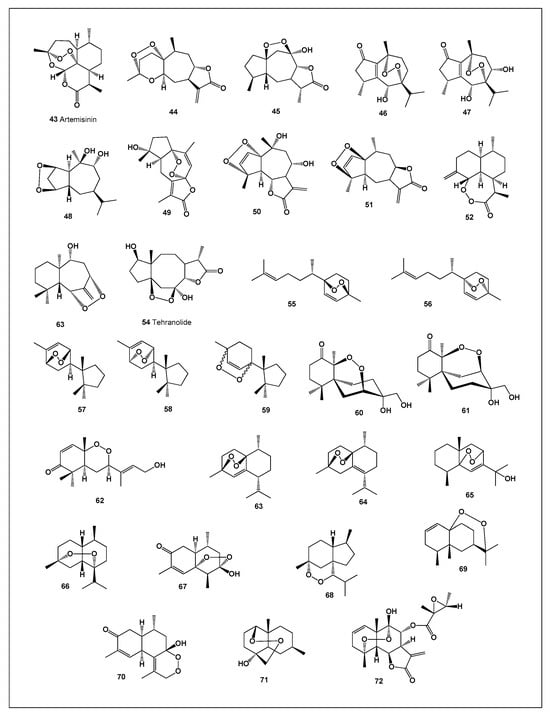

Artemisinin (43; structure shown in Figure 6, biological activity summarized in Table 3, and 3D representation presented in Figure 7) is a natural metabolite and represents the fastest-acting drug currently available for the treatment of tropical malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum. In 1971, Chinese researchers isolated the compound responsible for the antimalarial activity of Artemisia annua leaves. This substance, originally termed qinghaosu (QHS) and later named artemisinin, is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a unique endoperoxide moiety. Notably, unlike most conventional antimalarial agents, artemisinin lacks a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ring system [11,52,53].

Figure 6.

Bioactive endoperoxides derived from plants. Plants represent one of the most important natural sources of endoperoxide-containing terpenoids, many of which have been used in traditional medicine long before their chemical structures and mechanisms of action were elucidated. These compounds are predominantly derived from sesquiterpene, diterpene, and triterpene biosynthetic pathways and are frequently associated with plant defense against herbivores, pathogens, and environmental stress. The characteristic endoperoxide (–O–O–) bridge confers unique redox properties that are closely linked to their biological activity. Among plant-derived endoperoxides, artemisinin from Artemisia annua is the most prominent example and remains the cornerstone of modern antimalarial therapy. Its endoperoxide moiety is essential for activity, undergoing iron-mediated cleavage within Plasmodium parasites to generate reactive oxygen-centered radicals that damage vital parasitic proteins and membranes.

Table 3.

Biological activities of endoperoxides derived from plants.

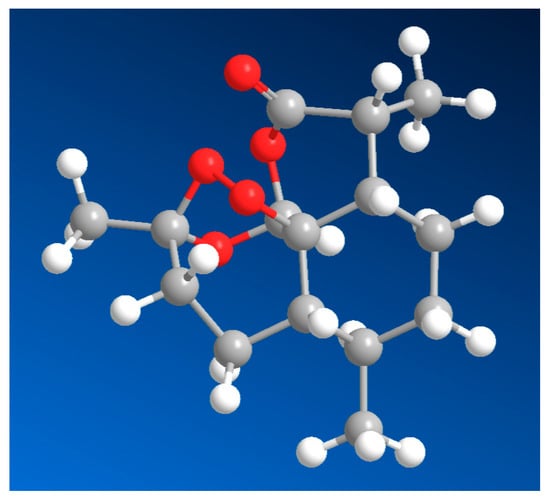

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional molecular representation of artemisinin (43), a sesquiterpene lactone endoperoxide isolated from the leaves of Artemisia annua. Artemisinin is the cornerstone of modern antimalarial therapy and exhibits potent activity against Plasmodium spp., as well as documented efficacy against Leishmania protozoan parasites. The three-dimensional topology highlights the compact, rigid framework of the molecule and the spatial orientation of the endoperoxide bridge, a key pharmacophoric feature responsible for its bioactivity. The peroxide moiety undergoes reductive activation in the presence of iron or heme, generating reactive oxygen-centered radicals that damage essential parasitic biomolecules. Beyond its antiprotozoal effects, artemisinin and its derivatives have demonstrated significant antineoplastic activity across multiple cancer cell lines, where the 3D molecular volume and peroxide accessibility are thought to facilitate selective activation in iron-rich tumor environments.

Beyond its well-established antimalarial efficacy, artemisinin (photographs of Artemisia annua are shown in Figure 8) has demonstrated potent anticancer activity across a wide range of human cancer cell models. Its pleiotropic anticancer effects include inhibition of cell proliferation through cell-cycle arrest, induction of apoptosis, suppression of angiogenesis, disruption of tumor cell migration, and modulation of nuclear receptor signaling. These effects arise from the ability of artemisinin to interfere with multiple intracellular signaling pathways simultaneously. Importantly, artemisinin exhibits high selectivity toward malignant cells and shows efficacy against a remarkably broad spectrum of cancers in both in vitro and in vivo models. By targeting several hallmarks of cancer concurrently, artemisinin is well suited for combination therapy and is less prone to the development of drug resistance [54,55,56].

Figure 8.

Artemisia annua (annual wormwood, sweet wormwood, annual mugwort, or one-year sagebrush) is a widespread species native to temperate regions of Asia and now naturalized in many parts of the world, including North America. Despite its common occurrence along roadsides and in disturbed habitats, A. annua is the natural source of artemisinin, a sesquiterpene endoperoxide of exceptional biomedical importance. (a,d) Leaves of A. annua; (b,c) inflorescences of A. annua.

Xanthane-type terpenoid 44 was isolated from Xanthium strumarium [57], while compound 45 was obtained from Artemisia diffusa [58]. Nardoperoxide (46) and its related analog (47), both exhibiting pronounced antimalarial activity, were isolated from Nardostachys chinensis [59,60]. Compound 48 was identified in Croton arboreous [61], whereas compound 49, isolated from Curcuma wenyujin, demonstrated notable antiviral activity [62].

Endoperoxide 50 was isolated from Achillea setacea [63], and compound 51 from Pulicaria undulata [64]. Artemisia annua yielded the rare endoperoxide arteannuin H (52), while compound 53 was again isolated from Illicium tsangii [65,66,67,68,69]. Two diastereomers, 54 and 55, identified as 3,6-epidioxy-1,10-bisaboladiene, were isolated from Senecio ventanensis [70]. Finally, tehranolide (56), a potent antimalarial endoperoxide, has been reported from several Artemisia species growing in Iran [71].

A broad array of endoperoxide-type sesquiterpenoids has been identified from diverse natural sources [72]. Compounds 57–59 were isolated from the Japanese liverwort Jungermannia infusca [73,74], while chamigranes merulin B (60) and merulin C (61) were obtained from a Thai fungal species [75,76]. Okundoperoxide (62), exhibiting significant antiplasmodial activity, was discovered in Scleria striatinux (Cyperaceae) [77].

Two muurolane-type endoperoxides—1,4-peroxymuurol-5-ene (63) and 1,4-peroxy-5-hydroxy-muurol-6-ene (64)—were isolated from Illicium tsangii [69]. Schisansphene A (65), a hydroperoxide-containing sesquiterpenoid, was obtained from Schisandra sphenanthera (magnolia berry) [78]. Additionally, (+)-muurolan-4,7-peroxide (66) was identified in the essential oil of Plagiochila asplenioides [79].

From the invasive plant Eupatorium adenophorum, compounds 67, 68, and 69 were isolated [80,81,82]. Other structurally unique endoperoxides include compound 70 from Ligularia veitchiana [83], compound 71 from Xylopia emarginata [84], and compound 72 from Montanoa hibiscifolia [85].

The biological activity data summarized in Table 3 are of particular importance, as they include artemisinin (43), a unique natural endoperoxide with an exceptional pharmacological profile. Artemisinin demonstrates strong antineoplastic and antilanoma activities, along with moderate antimetastatic and anti-apoptotic effects. However, its most distinctive feature is its potent activity against protozoal parasites, including Plasmodium falciparum, Leishmania tropica, and Trypanosoma brucei, as well as pronounced antibacterial activity. Computational prediction of biological activities corroborated the extensive experimental data reported in the literature, confirming the multifunctional pharmacological profile of artemisinin [11,52,53,54,55,56].

Figure 8 presents a three-dimensional activity profile of artemisinin (43), while Figure 6 illustrates Artemisia annua, the plant source responsible for biosynthesis of this bioactive endoperoxide. Among the thirty endoperoxides (43–72) evaluated, nine compounds (43–45, 50, 53, 54, 57–59) exhibited strong antineoplastic activity, and fourteen compounds demonstrated strong antiprotozoal effects. Notably, four endoperoxides—53, 57, 64, and 65—combined strong antiprotozoal activity with pronounced anti-inflammatory properties, highlighting their potential as multifunctional therapeutic agents.

3. Comparison of the Biological Activity of Endoperoxides

The biological activity of a molecule is fundamentally governed by its chemical structure, a concept formalized through the structure–activity relationship (SAR) paradigm. Early qualitative observations by Brown and Fraser [86] in the 19th century established that subtle structural modifications can lead to profound changes in biological response, a principle later systematized by Hansch and Fujita [87] into quantitative structure–activity relationships (QSAR). These frameworks have since become central to medicinal chemistry, toxicology, and natural product research, enabling rational interpretation of how molecular features dictate biological function [88].

In the context of endoperoxide-containing terpenoids, SAR analysis reveals that the peroxide moiety (–O–O–) is the dominant pharmacophoric element underlying biological activity. This highly strained and redox-active functional group is essential for antiprotozoal activity, particularly against Plasmodium species. Artemisinin and its derivatives exemplify this relationship: reduction in the endoperoxide bond by ferrous iron or heme iron within the parasite generates reactive oxygen-centered radicals that alkylate vital proteins and lipids, ultimately leading to parasite death. Compounds lacking the intact peroxide bridge consistently show dramatic loss of antimalarial efficacy, underscoring its indispensable role [89].

Comparative analysis across natural endoperoxides indicates that antiprotozoal activity correlates most strongly with peroxide accessibility and electronic activation. Molecules featuring sterically exposed endoperoxide rings, such as 1,2,4-trioxanes and 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes, tend to exhibit higher potency than those in which the peroxide is shielded within rigid polycyclic frameworks. Additionally, the presence of lipophilic substituents adjacent to the peroxide often enhances membrane permeability and intracellular accumulation, further increasing antiparasitic effectiveness [90,91,92,93].

In contrast, anticancer activity displays a more nuanced SAR profile. While the peroxide bond remains crucial, additional structural factors—including overall molecular size, ring fusion patterns, and substituent polarity—play significant roles. Endoperoxides with extended polycyclic scaffolds or conjugated systems often demonstrate selective cytotoxicity toward tumor cells, likely due to enhanced redox cycling and preferential induction of oxidative stress in cancer cells, which are already under elevated oxidative pressure. Unlike antiprotozoal activity, anticancer effects frequently tolerate greater structural variation outside the peroxide core, suggesting multiple overlapping mechanisms such as mitochondrial dysfunction, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis induction [94].

Anti-inflammatory activity represents a third SAR category with partially overlapping but distinct structural requirements. Several endoperoxides exhibit inhibition of nitric oxide production, cyclooxygenase expression, or pro-inflammatory cytokine release. In these cases, the peroxide moiety may contribute indirectly by modulating intracellular redox signaling rather than by direct radical-mediated cytotoxicity. Compounds with additional hydroxyl groups or polar functionalities often show enhanced anti-inflammatory profiles, suggesting that hydrogen-bonding capacity and receptor interactions are more influential than peroxide reactivity alone [95,96].

Comparative evaluation across these three activity domains—antiprotozoal, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory—indicates that while the endoperoxide bond is a unifying structural feature, the optimal surrounding molecular architecture differs depending on the biological target. Antiprotozoal activity requires efficient peroxide activation and radical generation; anticancer activity benefits from redox cycling combined with scaffold-driven selectivity; and anti-inflammatory effects appear to rely on balanced redox modulation and molecular recognition [97].

These experimentally observed trends are supported by computational predictions obtained using the PASS (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances) system. PASS analysis consistently assigns high probabilities for antiprotozoal and antineoplastic activities to endoperoxide-containing terpenoids, particularly those with trioxane or tetraoxane motifs. Notably, PASS predictions also highlight potential anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory activities for several compounds that have not yet been experimentally evaluated, suggesting promising directions for future bioassay-guided investigations [98].

Overall, the comparative SAR and QSAR analysis presented here demonstrates that endoperoxides constitute a multifunctional pharmacological class, in which a conserved reactive motif is adapted through structural diversification to produce distinct biological outcomes. This versatility underscores the value of endoperoxide scaffolds as privileged structures in drug discovery and highlights the importance of integrated experimental and computational approaches for fully elucidating their therapeutic potential.

PASS Program (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances)

PASS Online is a widely used computational platform designed for the in silico prediction of biological activity profiles of chemical compounds based solely on their structural formulas. The system predicts more than 10,000 types of biological activities, including pharmacological effects, mechanisms of action, toxic and adverse effects, interactions with metabolic enzymes and transporters, and potential influences on gene expression. Because PASS requires only a two-dimensional chemical structure as input, it can be applied not only to isolated natural products but also to virtual compounds that have not yet been synthesized [99,100].

Access to PASS Online is freely available following user registration and acceptance of the service’s terms and conditions. The predictive models implemented in PASS are based on structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis derived from an extensive training set comprising over 1,000,000 biologically characterized substances, including approved drugs, clinical candidates, lead compounds, and known toxic agents. Continuous expansion of the training dataset aims to improve prediction accuracy, particularly for emerging chemical scaffolds and newly defined biological targets [101,102].

The overall predictive performance of PASS has been rigorously evaluated. Using leave-one-out cross-validation—where each compound is excluded from the training set and its activities predicted based on the remaining data—the average accuracy across the training set has been reported to be approximately 95%. Additional robustness assessments were performed using a large reference dataset containing one million compounds associated with 10,000 biological activities. In these studies, repeated random partitioning of the dataset into training and evaluation subsets demonstrated that PASS retains reasonable predictive accuracy even when up to 60% of the training information is removed, underscoring the stability of the underlying algorithm [98,99,100,101].

PASS has been employed for several decades by medicinal chemists, pharmacologists, and toxicologists, and numerous studies have shown that PASS predictions are frequently validated by subsequent synthesis and biological testing. Nevertheless, the applicability of PASS is most reliable for compounds that fall within the “drug-like” chemical space represented in the training set. Predictions for compounds belonging to entirely new chemical classes—particularly those containing multiple structural descriptors absent from the training database—should be regarded as exploratory. If a compound contains more than two novel descriptors, prediction outcomes are best interpreted as preliminary hypotheses rather than definitive activity assignments [99,100].

It is also important to note that PASS may predict both agonistic and antagonistic effects for the same biological target, reflecting potential receptor or enzyme affinity rather than functional outcome. Consequently, experimental validation remains essential to determine the actual mode of action. PASS does not aim to predict whether a compound will ultimately become a drug; instead, it serves as a prioritization tool to identify the most promising leads for further biological evaluation [100,101,102].

Among computational approaches applied to natural product research, PASS has proven particularly valuable for structurally complex and chemically reactive molecular classes, such as endoperoxides and highly oxygenated steroids. These compounds often challenge conventional SAR methodologies due to labile functional groups and redox-sensitive mechanisms. In such cases, PASS-based predictions provide an efficient strategy to highlight dominant biological activity profiles, guide experimental design, and support rational selection of candidates for downstream pharmacological studies [97,98,103].

4. Conclusions

Naturally occurring endoperoxide-containing terpenoids represent a chemically and biologically distinctive class of secondary metabolites whose activities are intimately linked to the presence and structural context of the cyclic peroxide (–O–O–) moiety. Across the compounds reviewed, antiprotozoal, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory activities are all associated with peroxide functionality; however, the underlying structural determinants governing these bioactivities are not identical and depend strongly on molecular framework, substitution pattern, and stereochemical environment.

Antiprotozoal activity, particularly antimalarial potency, is most consistently associated with endoperoxides embedded within rigid polycyclic scaffolds, such as sesquiterpene lactones and trioxane systems typified by artemisinin and its analogs. In these compounds, the spatial proximity of the peroxide bond to electron-rich or metal-coordinating centers enables iron-mediated cleavage, generating reactive oxygen-centered radicals that selectively damage parasite biomolecules. PASS predictions strongly supported these observations, assigning high probabilities (Pa > 0.8) for antiprotozoal and antiparasitic activities to artemisinin-like scaffolds and structurally related endoperoxides.

In contrast, antitumor activity appears to depend on a broader set of structural features beyond peroxide presence alone. Endoperoxides displaying cytotoxic or antiproliferative effects often combine the peroxide unit with additional electrophilic functionalities, extended conjugation, or lipophilic substituents that facilitate cellular uptake and interaction with multiple intracellular targets. PASS analysis predicted high probabilities for antineoplastic, apoptosis-inducing, and kinase-modulating activities across several structurally diverse endoperoxides, indicating that tumor-related activity may arise from multitarget mechanisms rather than a single peroxide-driven pathway.

Anti-inflammatory activity represents a partially overlapping yet distinct activity profile. Compounds exhibiting suppression of nitric oxide production, cytokine release, or inflammatory enzyme expression frequently possess more flexible frameworks and reduced steric congestion around the peroxide bond, potentially limiting radical-mediated cytotoxicity while preserving redox-modulating capacity. PASS predictions consistently indicated moderate-to-high probabilities for anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and enzyme-inhibitory activities for these compounds, supporting experimental observations and suggesting that peroxide-containing terpenoids can act as redox-sensitive signaling modulators.

Overall, PASS-based computational analysis complemented experimental data by revealing dominant activity spectra, highlighting shared trends among structurally related compounds, and identifying potential bioactivities for endoperoxides that have not yet been experimentally evaluated. While PASS does not predict clinical drug likeness, it provides a robust framework for prioritizing endoperoxide scaffolds for targeted biological testing and for guiding future structural optimization.

In summary, although the cyclic peroxide motif is a unifying structural feature across antiprotozoal, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory endoperoxides, the precise biological outcome is dictated by scaffold architecture, functional group context, and stereochemical arrangement. These findings underscore the importance of integrating experimental bioassays with computational prediction tools to better understand the multifunctional nature of endoperoxides and to support their rational development as leads for therapeutic intervention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.D.; methodology, V.M.D.; software, A.O.T.; investigation, V.M.D.; resources, V.M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.T. and V.M.D.; writing—review and editing, A.O.T. and V.M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Valery M. Dembitsky was affiliated with Bio-Pharm Laboratories. The remaining authors declare that the study was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial ties that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dembitsky, V.M. Highly oxygenated cyclobutafggne ring in biomolecules: Insights into structure and activity. Oxygen 2024, 4, 181–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.; Gohr, S.T.; Köllner, T.G.; Bathe, U.; Lackus, N.D.; Padilla-Gonzalez, F.; Tissier, A. Biosynthesis of biologically active terpenoids in the mint family (Lamiaceae). Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 1887–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, J.S.; Perestrelo, R.; Ferreira, R.; Berenguer, C.V.; Pereira, J.A.; Castilho, P.C. Plant-derived terpenoids: A plethora of bioactive compounds with several health functions and industrial applications—A comprehensive overview. Molecules 2024, 29, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, F.R.; Salehi, H.; Khallaf, M.A.; Rizwan, K.; Gouda, M.; Ahmed, S.; Simal-Gandara, J. Limonoids: Advances in extraction, characterization, and applications. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1871–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Ermolenko, E.; Savidov, N.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Antiprotozoal and antitumor activity of natural polycyclic endoperoxides: Origin, structures and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive peroxides as potential therapeutic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive fungal endoperoxides. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vil, V.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Savidov, N.; Dembitsky, V.M. Peroxy steroids derived from plants and fungi and their biological activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7657–7667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vil, V.A.; Yaremenko, I.A.; Ilovaisky, A.I.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Dembitsky, V.M. Peroxides with anthelmintic, antiprotozoal, fungicidal and antiviral bioactivity: Properties, synthesis and reactions. Molecules 2017, 22, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terent’ev, A.O.; Borisov, D.A.; Vil, V.A. Synthesis of five- and six-membered cyclic organic peroxides: Key transformations into peroxide ring-retaining products. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 34–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klayman, D.L.; Lin, A.J.; Acton, N.; Scovill, J.P.; Hoch, J.M.; Milhous, W.K.; Theoharides, A.D. Isolation of artemisinin (qinghaosu) from Artemisia annua growing in the United States. J. Nat. Prod. 1984, 47, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.F.S.; Janick, J. Distribution of artemisinin in Artemisia annua. Prog. New Crops 1996, 1, 579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, S.O.; Vaughn, K.C.; Croom, E.M., Jr. Artemisinin, a constituent of annual wormwood (Artemisia annua), is a selective phytotoxin. Weed Sci. 1987, 35, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, B.; Qu-Bie, A.; Li, M.; Luo, M.; Feng, M.; Liu, Y. Endoperoxidases in biosynthesis of endoperoxide bonds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 136, 136806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, A.; Liu, C.; Arsenault, P.R. DMSO triggers the generation of ROS leading to an increase in artemisinin and dihydroartemisinic acid in Artemisia annua shoot cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2010, 29, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehl, F.A., Jr.; Humes, J.L.; Egan, R.W. Role of prostaglandin endoperoxide PGG2 in inflammatory processes. Nature 1977, 265, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.L.; Urade, Y.; Jakobsson, P.-J. Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5821–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruana, A.; Savona-Ventura, C.; Calleja-Agius, J. COX isozymes and non-uniform neoangiogenesis: What is their role in endometriosis? Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2023, 167, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsegyan, Y.A.; Vil, V.A.; Terent’ev, A.O. Macrocyclic organic peroxides: Constructing medium and large cycles with O–O bonds. Chemistry 2024, 6, 1246–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Vil, V.A. Medicinal chemistry of stable and unstable 1,2-dioxetanes: Origin, formation, and biological activities. Sci. Synth. Knowl. Updates 2019, 38, 333–381. [Google Scholar]

- Clennan, E.L. Aromatic endoperoxides. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 99, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Yaremenko, I.A. Stable and unstable 1,2-dioxolanes: Origin, synthesis, and biological activities. Sci. Synth. Knowl. Updates 2020, 38, 277–321. [Google Scholar]

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Vil’, V.A.; Demchuk, D.V.; Terent’ev, A.O. Rearrangements of organic peroxides and related processes. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1647–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamez-Fernández, J.F.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Ibarra-Rivera, T.R.; Rivas-Galindo, V.M. Plant-derived endoperoxides: Structure, occurrence, and bioactivity. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 827–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.F.; Zhang, X.P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ma, G.X.; Tian, Y.; Wu, L.Z.; Chen, S.L.; Yang, J.S.; Xu, X.D. Four new diterpenes from Aphanamixis polystachya. Fitoterapia 2013, 90, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; He, H.P.; Di, Y.T.; Li, S.L.; Zuo, G.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, X.J. Chemical constituents from Aphanamixis grandifolia. Fitoterapia 2014, 92, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.L.; Jong, J.R. A cyclic peroxide of clerodenoic acid from the Taiwanese liverwort Schistochila acuminata. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2001, 3, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, F.; Takaishi, Y.; Kashiwada, Y.; Osorio, C.; Duque, C.; Acuña, R.; Fujimoto, Y. ent-3,4-seco-Labdane and ent-labdane diterpenoids from Croton stipuliformis (Euphorbiaceae). Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2406–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Cheng, Y.B.; Liaw, C.C.; Chen, C.H.; Guh, J.H.; Hwang, T.L.; Tsai, J.S.; Won-Bo, W.; Shen, Y.C. Bioactive diterpenes from Callicarpa longissima. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Brown, G.D. Labdane diterpenoids from Alpinia chinensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamchonwongpaisan, S.; Nilanonta, C.; Tarmchampoo, B.; Thebtaranonth, C.; Thebtaranonth, Y.; Yuthavong, Y.; Kongsaeree, P.; Clardy, J. An antimalarial peroxide from Amomum krervanh Pierre. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1821–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.B.; Zhu, R.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Guo, H.F.; Wang, X.N.; Xie, C.F.; Yu, W.T.; Ji, M.; Lou, H.X. ent-Kaurane diterpenoids from the liverwort Jungermannia atrobrunnea. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Xi, M.; Li, Y. Triptotin A and B, two novel diterpenoids from Tripterygium wilfordii. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 947–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, M.; Minami, H.; Hayashi, E.; Kodama, M.; Kawazu, K.; Fukuyama, Y. Neovibsanin C, a macrocyclic peroxide-containing neovibsane-type diterpene from Viburnum awabuki. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6261–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C.; De Ford, C.; Castro, V.; Merfort, I.; Murillo, R. Cytotoxic clerodane diterpenes from Zuelania guidonia. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Yang, K.X.; Yang, X.W.; Khan, A.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Luo, X.D. New cytotoxic tigliane diterpenoids from Croton caudatus. Planta Med. 2016, 82, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graikou, K.; Aligiannis, N.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Chinou, I.; Michel, S.; Tillequin, F.; Litaudon, M. New diterpenes from Croton insularis. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Harrison, L.J.; Tan, B.C. Terpenoids from the liverwort Chandonanthus hirtellus. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 4035–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, R.; Wahlberg, I.; Enzell, C.R.; Berg, J.E. Tobacco chemistry: Structure determination and biomimetic syntheses of two new tobacco cembranoids. Acta Chem. Scand. 1988, 42, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; del Moral, J.F.Q.; Aitigri, M. Oxygenated diterpenes and other constituents from Moroccan Juniperus phoenicea and Juniperus thurifera var. africana. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, J.; Pérez, L.; Rabanal, R.M.; Valverde, S. Diterpenoids from Salvia oxyodon and Salvia lavandulifolia. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, P.; Parrilli, M.; Previtera, L. Two endoperoxide diterpenes from Elodea canadensis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4609–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; Sánchez, J.F.; Álvarez-Mansaneda, E.J.; Dorado, R.M.; Haidour, A. Endoperoxide diterpenoids and other constituents from Abies marocana. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, G.; Sánchez, E.; Hernández, J.; Alvarez, L.; Martínez, E. Abietanoid acids from Lepechinia caulescens. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 3159–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Feliciano, A.; del Corral, J.M.M.; Gordaliza, M.; Castro, M.A. Two diterpenoids from the leaves of Juniperus sabina. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.G.; Chou, G.X.; Mao, X.D.; Yang, Q.S.; Zhou, J.L. Nepetaefolins A–J, cytotoxic chinane and abietane diterpenoids from Caryopteris nepetaefolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 1742–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrero, A.F.; Quílez del Moral, J.F.; Herrador, M.M.; Arteaga, J.F.; Akssira, M.; Benharref, A.; Dakir, M. Abietane diterpenes from the cones of Cedrus atlantica. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslovskaya, L.A.; Savchenko, A.I.; Gordon, V.A.; Reddell, P.W.; Pierce, C.J.; Parsons, P.G.; Williams, C.M. Isolation and confirmation of the proposed cleistanthol biogenetic link from Croton insularis. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1032–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslovskaya, L.A.; Savchenko, A.I.; Pierce, C.J.; Gordon, V.A.; Reddell, P.W.; Parsons, P.G.; Williams, C.M. Unprecedented 1,14-seco-crotofolanes from Croton insularis: Oxidative cleavage of crotofolin C via a putative homo-Baeyer–Villiger rearrangement. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 14226–14230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola, L.A.; Morales, C.; Rodríguez, B.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; de la Torre, M.C.; Perales, A.; Torres, M.R. Mulinic and isomulinic acids: Rearranged diterpenes with a new carbon skeleton from Mulinum crassifolium. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 5413–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Gao, J.J.; Qin, X.J.; Hao, X.J.; He, H.P.; Liu, H.Y. Hedychins A and B, 6,7-dinorlabdane diterpenoids with a peroxide bridge from Hedychium forrestii. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F. Discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu). Molecules 2009, 14, 5362–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahnum, D.; Abimanyu, H.; Senjaya, A. Isolation of artemisinin as an antimalarial drug from Artemisia annua L. cultivated in Indonesia. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2012, 12, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, G.L.; Sundar, S.N. Anticancer activities of artemisinin and its bioactive derivatives. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009, 11, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sun, Z.; Kong, F.; Xiao, J. Artemisinin-derived hybrids and their anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yi, C.; Li, W.W.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.Z.; Ling, H.B. The current scenario on anticancer activity of artemisinin metal complexes, hybrids, and dimers. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, 2200086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.A. Xanthanolides and xanthane epoxide derivatives from Xanthium strumarium. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustaiyan, A.; Nahrevanian, H.; Kazemi, M.; Larijani, K. Antimalarial effects of extracts of Artemisia diffusa against Plasmodium berghei. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, Y.; Kurumada, K.; Takeuji, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Shibata, Y.; Ikemoto, N.; Kim, H.S.; Shibata, Y.; Ikemoto, N.; Wataya, Y.; et al. Novel antimalarial guaiane-type sesquiterpenoids from Nardostachys chinensis roots. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, Y.; Takeuji, Y.; Akasaka, M.; Nakagawasai, O.; Tadano, T.; Kisara, K.; Kim, H.S.; Wataya, Y.; Niwa, M.; Oshima, Y. Nardoguaianones A–D, novel guaiane endoperoxides from Nardostachys chinensis and their biological activities. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 7673–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Guadarrama, A.B.; Ríos, M.Y. Three new sesquiterpenes from Croton arboreus. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Cai, X.Q.; Yan, P.C.; Yue, L.; Lin, C.; Shao, W.W. Sesquiterpenoids from Curcuma wenyujin with anti-influenza viral activity. Phytochemistry 2013, 85, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, M.; Vogler, B.; Tsankova, E. Terpenoids from Achillea setacea. Z. Naturforsch. C 2000, 55, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, M.E.F.; Nakamura, S.; Tawfik, W.A.; Abdel-Azim, N.S.; Abdel-Lateff, A.; Matsuda, H.; Pare, P.W. Rare hydroperoxyl guaianolide sesquiterpenes from Pulicaria undulata. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 12, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Brown, G.D. Abietane diterpenes from Illicium angustisepalum. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Brown, G.D.; Haynes, R. A novel endoperoxide and related sesquiterpenes from Artemisia annua possibly derived from allylic hydroperoxides. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 4345–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, L.K.; Ngo, K.S.; Brown, G.D. Biomimetic synthesis of arteannuin H and the 3,2-rearrangement of allylic hydroperoxides. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 15127–15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, K.S.; Brown, G.D. Allohimachalane, seco-allohimachalane, and himachalane sesquiterpenes from Illicium tsangii. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, K.S.; Brown, G.D. Santalane and isocampherenane sesquiterpenoids from Illicium tsangii. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alza, N.P.; Murray, A.P. Chemical constituents and acetylcholinesterase inhibition of Senecio ventanensis Cabrera (Asteraceae). Rec. Nat. Prod. 2016, 10, 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Rustaiyan, A.; Faridchehr, A.; Bakhtiyar, M. Sesquiterpene lactones of the Iranian Asteraceae family: Chemical constituents and antiplasmodial properties of tehranolide (Review). Orient. J. Chem. 2017, 33, 2506–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, Y.; Abdelwahab, G.; Heraiz, A.A.; Sallam, M.; Othman, A. Exploring sesquiterpene lactones: Structural diversity and antiviral therapeutic insights. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1970–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, F.; Suzuki, M.; Takaoka, S.; Asakawa, Y. New sesqui- and diterpenoids from the Japanese liverwort Jungermannia infusca (Mitt.) Steph. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 46, 1184–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nagashima, F.; Suzuki, M.; Takaoka, S.; Asakawa, Y. New acorane- and cuparane-type sesquiterpenoids and labdane- and seco-labdane-type diterpenoids from Jungermannia infusca. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 9117–9128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokpaiboon, S.; Sommit, D.; Bunyapaiboonsri, T.; Matsubara, K.; Pudhom, K. Antiangiogenic effects of chamigrane endoperoxides from a Thai mangrove-derived fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokpaiboon, S.; Sommit, D.; Teerawatananond, T.; Muangsin, N.; Bunyapaiboonsri, T.; Pudhom, K. Cytotoxic nor-chamigrane and chamigrane endoperoxides from a basidiomycetous fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efange, S.M.N.; Brun, R.; Wittlin, S.; Connolly, J.D.; Hoye, T.R.; McAkam, T.; Wirmum, C.K. Okundoperoxide, a bicyclic cyclofarnesyl sesquiterpene endoperoxide from Scleria striatinux with antiplasmodial activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.H.; Tan, C.M.; He, J.C.; Duan, P.S.; Qin, L.P. A novel eudesmene sesquiterpenoid from the stems of Schisandra sphenanthera. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2011, 47, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adio, A.M.; König, W.A. Sesquiterpene constituents from the essential oil of the liverwort Plagiochila asplenioides. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, F.; Matsumura, N.; Ashigaki, Y.; Asakawa, Y. Biologically active compounds from bryophytes. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 2003, 94, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Hou, J.; Gan, M.; Shi, J.; Chantrapromma, S.; Fun, H.K.; Herman, W.V.; Sung, H.H.Y. Cadinane sesquiterpenes from the leaves of Eupatorium adenophorum. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, G.W.; Niu, X.M.; Li, W.Q.; Wang, F.S.; Li, S.H. Terpenes from Eupatorium adenophorum and their allelopathic effects on Arabidopsis seed germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.Z. Two eremophilane-type sesquiterpenoids from the rhizomes of Ligularia veitchiana. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2009, 25, 480–483. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, I.C.; Roque, N.F.; Contini, K.; Lago, J.H.G. Sesquiterpenes and hydrocarbons from the fruits of Xylopia emarginata (Annonaceae). Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2007, 17, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Murillo, R.; Castro, V.; Merfort, I. Sesquiterpene lactones from Montanoa hibiscifolia that inhibit the transcription factor NF-κB. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.C.; Fraser, T.R. The connection of chemical constitution and physiological action. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1868, 25, 224–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hansch, C.; Fujita, T. p-σ-π analysis: A method for the correlation of biological activity and chemical structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 1616–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A. Exploring QSAR: Fundamentals and Applications in Chemistry and Biology; ACS: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Microbiological aspects of unique, rare, and unusual fatty acids derived from natural amides and their pharmacological profiles. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 13, 377–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratov, E.N.; Bajorath, J.; Sheridan, R.P.; Tetko, I.V.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V.; Tropsha, A. QSAR without borders. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3525–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive steroids bearing an oxirane ring. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Baranin, S.V. Boronosteroids as potential antitumor drugs: A review. Tumor Discov. 2025, 4, 025290069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Naturally occurring norsteroids: Design and pharmaceutical applications. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadia, A.C.M.; Gnoatto, S.C.B. Chemistry and biological properties of Ascaridole: A systematic review. Fitoterapia 2025, 188, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, T.; Jiao, A.; Mou, X.; Dong, X.; Cai, Y. Molecular endoperoxides for optical imaging and photodynamic therapy. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2025, 523, 216258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.K.; Alka, A.; Agarwal, A. Endoperoxides as Antimalarials: Development, Structural Diversity, and Pharmacodynamic Aspects of 1, 2, 4, 5-Tetraoxane-Based Structural Scaffolds. SynOpen 2025, 9, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shaha, C. Plant-derived products as anti-leishmanials which target mitochondria: A review. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2025, 27, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E.N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y.C.; Todeschini, R.; et al. QSAR modeling: Where have you been? Where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4977–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PASS Online. Available online: https://way2drug.com/PassOnline/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lagunin, A.; Stepanchikova, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. PASS: Prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A.; Zakharov, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. QSAR modelling of rat acute toxicity on the basis of PASS prediction. Mol. Inform. 2011, 30, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the biological activity spectra of organic compounds using the PASS online web resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanuš, L.; Naor, T.; Gloriozova, T.; Dembitsky, V.M. Natural isothiocyanates of the genus Capparis as potential agonists of apoptosis and antitumor drugs. World J. Pharm. 2023, 12, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.