Abstract

Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) and feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L. Sch. Bip.), both members of the Asteraceae family, are widely distributed in Serbia and traditionally used for their medicinal properties. Chamomile is primarily known for its gastrointestinal effects, while feverfew is noted for its antimigraine activity. Although the biological activity of each plant has been individually studied, there has been a lack of research related to their blends. So, the aim of this study was to prepare various chamomile/feverfew blends and their extracts with special focus on extraction temperature, to obtain superior herbal extract with the best functional characteristics. In order to characterize the obtained blend extracts this study included spectrophotometric and UHPLC Q-ToF MS analysis of prepared (selected) extracts, as well as evaluation of their antioxidant (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and CUPRAC) and antimicrobial properties. Antibacterial activity was evaluated against two Gram-positive and four Gram-negative bacterial strains using the broth microdilution method. Untargeted analysis showed the same phytochemical profile for both selected extracts (B3 and B9), as well as differences in distribution and abundance of identified compounds depending on applied extraction temperature (cold or heat-assisted). These differences in profile most probably contributed to variations in the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the extracts. The most potent antioxidant activity (123.04 µM TEAC/g) was observed for the 3:1 feverfew/chamomile blend (ABTS assay), while the highest metal-chelating capacity (1288.95 µM VCEAC/g) was recorded in extracts obtained by heat-assisted extraction (CUPRAC assay). Antibacterial activity of all blends ranged from 0.625 to 2.5 mg/mL, regardless of the extraction method. The findings indicate that combined extracts of chamomile and feverfew represent a promising source of bioactive compounds with potential applicability in both food science and pharmaceutical (biomedical) research.

1. Introduction

Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) and feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L. Sch. Bip.), both medicinal plants from Asteraceae family, have a long tradition of use in European and American herbal medicine [1,2]. In Europe, chamomile and feverfew flowers have traditionally been used as antispasmodic, carminative, anti-stress, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antimigraine agents [1]. Feverfew, in particular, has also been traditionally employed in the treatment of various health problems, such as arthritis, colds, fever, gastrointestinal disturbances, toothaches, and cardiovascular disorders [3,4]. Today, both species are widely incorporated into commercial products, including cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, detergents, perfumes, creams, antimigraine capsules, confections, strong alcoholic beverages, and teas [1,4]. Whether used individually, in blends, or encapsulated into natural polymers, chamomile and feverfew display strong antioxidant [5] and antibacterial [6] activities. Their essential oils have shown considerable potential in treating skin inflammation, rashes, and skin peeling, as well as a sedative effects in aromatherapy [7]. Feverfew extracts have also demonstrated antiviral, prophylactic, and anticancer activities. Their broad biological effects include the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, reduction in vascular smooth muscle spasms, and suppression of platelet granule secretion [4]. Numerous pharmacological and clinical studies suggest that feverfew extracts may possess antimigraine activity, likely through the inhibition of serotonin-mediated platelet aggregation [8,9]. However, their clinical efficacy appears to vary depending on the dosage, formulation, and study design, underscoring the need for further research using standardized extracts and rigorous methodologies. The biological effects of feverfew are mainly attributed to parthenolides, a class of sesquiterpene lactones with demonstrated anticancer activity against several human cancer cell lines, including fibroblasts, virus-transformed cells, and nasopharyngeal epidermoid carcinoma [10]. Phytochemical analyses have revealed that chamomile flowers are rich in phenolic acids (65% caffeic and ferulic acid, and unidentified phenolic derivatives), flavonoids (1.9–16.8%, including luteolin, patuletin, quercetin, and apigenin), and coumarins (less than 0.1%, including herniarin and umbelliferone). Feverfew flowers contain flavonoids (quercetin, apigenin, apigen-7-gluconoride, luteolin, chrysoeriol, santin, jaceidin, etc.), and parthenolids (parthenolide, constunolide, 3-β-hydroxy parthenolide, secotanaparthenolide, and epoxysantamarin) [11,12,13,14].

Plant polyphenols are well known for their potent antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [15]. Additionally, blends of medicinal plants often demonstrate superior biological activity compared to single-plant extracts, largely due to synergistic interactions between polyphenols [16]. The compounds present in the plant material can effectively be extracted and formulated into various products, including dry and liquid extracts, plant blends, herbal teas, medicinal drops, and pharmaceutical preparations [17]. The efficiency of polyphenol extraction depends on several critical parameters, including extraction temperature, duration, solvent type, solid-to-solvent ratio, and the ratio of plant materials within the blend [18]. Both high and low temperatures employed during the extraction process can have side effects, i.e., high temperatures can degrade thermolabile compounds, whereas excessively low temperatures may reduce extraction yield, prolong processing time, and thus limit biological efficacy. Solvent polarity and concentration also play decisive roles in extraction efficiency [18], with the binary solvent systems or aqueous-alcoholic mixtures frequently producing extracts with high antioxidant capacity [19].

Although the pharmacological potential of chamomile and feverfew flowers has been extensively studied individually, research into their combined use remains scarce, despite [20,21] their established applications in treating neurological and gastrointestinal disorders [22,23]. Possible synergistic effects resulting from blending these species, especially when varying the ratios of the starting plant materials have not been thoroughly investigated. Previous studies have shown the significant influence of temperature extraction on the content of bioactive compounds and the biological activities of some of the plant extracts [24]. Keeping this in mind, the aim of this study is to systematically examine the impact of extraction temperature (cold, room temperature and heat-assisted) on the phytochemical profile of selected chamomile/feverfew blends, as well as to evaluate their antioxidant and antibacterial potential. The biological activity of the resulting extracts was evaluated with aims to identify which blend and prepared extract has the greatest potential for further medicinal applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Standards

Copper (II) chloride; 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline; 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman -2-carboxylic acid; ammonium acetate; sodium hydroxide; potassium ferricyanide; disodium hydrogen phosphate; sodium dihydrogen phosphate; potassium ferricyanide (tris-potassium hexacyanoferrate(III)); aluminum chloride; sodium nitrite; sodium carbonate; Folin–Ciocâlteu reagent; povidone iodine; vitamin C (ascorbic acid); trichloroacetic acid; 7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazin-3-one 10-oxide; potassium persulfate; methanol; acetonitrile; and formic acid were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany). Distilled water (pH 6.5) was used for the preparations of all solutions.

2.2. Preparation of Chamomile and Feverfew Extracts

Chamomile and feverfew plant material were obtained from the Institute for Medicinal Plant Research „Dr Josif Pančić”, Serbia. The extracts were prepared using three extraction methods differing in extraction temperature: cold extraction (4 ± 1 °C), room temperature extraction (21 ± 1 °C), and heat-assisted extraction (63 ± 1 °C). Additionally, different mass ratios of the two plant materials were applied, as summarized in Table 1. The illustrated experimental procedure is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the extraction of chamomile/feverfew blends, using 70% ethanol (v/v) as the extraction solvent, and a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:10.

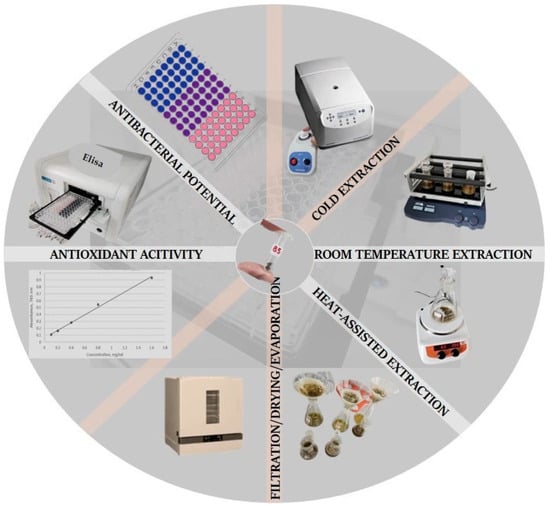

Figure 1.

An illustrated experimental protocol for the preparation of chamomile and feverfew blend extracts under varying extraction conditions and blend ratios, followed by the assessment of biological activities (antioxidant and antibacterial) of the obtained extracts.

After extraction, the raw extracts (Figure 2) were filtered through quantitative filter paper (90 mm, Qté. 100, Filtres Fioroni®, Orléans, Centre-Val de Loire, France), dried in the laboratory convection oven (MOV-212, Sanyo Instruments, Osaka, Japan) at 35 °C for 96 h, and stored in the dark at 21 ± 1 °C until further analysis.

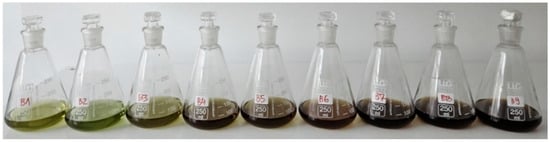

Figure 2.

The raw extracts of chamomile/feverfew blends (B1–B9), obtained by different extraction methods and conditions before drying.

2.2.1. Cold Extraction Under Refrigerated Centrifugal Agitation

Dried and powdered chamomile and feverfew samples were extracted using 70% ethanol (v/v) in 50 mL centrifuge tubes, applying a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:10. The extraction process began with vortex mixing (Grant Bio PV-1 Vortex mixer, Shepreth, Cambridgeshire, UK) at 1500 rpm for 10 min at 21 ± 1 °C. The mixture was then subjected to refrigerated centrifugal agitation using a centrifuge (Centrifuge 5430R, Eppendorf®, Hamburg, Germany) for 20 min at 4 ± 0 °C, with continuous agitation at 200 rpm. After this extraction step, the rotor speed was increased to 3000 rpm to facilitate sedimentation. The supernatant was subsequently filtered through quantitative filter paper, dried, and stored as described in the previous section. The extraction approach is based on what is reported in the literature, where refrigerated centrifugal agitation is employed as a mild extraction technique to preserve thermolabile bioactive compounds [24].

2.2.2. Extraction at Room Temperature

Room temperature extraction was performed in 250 mL Erlenmayer flaks using a digital linear shaker (SK-L330-Pro, Nantong Chem-Land Co., Ltd., Nantong, China) at a constant agitation speed of 200 rpm and temperature (ambient) of 21 ± 1 °C. The extraction solvent was 70% ethanol (v/v), applied at a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:10. The obtained extracts were filtered, dried, and stored at 21 ± 1 °C until further measurements.

2.2.3. Heat-Assisted Extraction

For heat-assisted extraction, 10 g of dried powdered chamomile/feverfew blend was weighted into a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask, followed by the addition of 100 mL of 70% ethanol (v/v). The extraction was performed at 63 ± 1 °C for 30 min under agitation at 200 rpm, using a magnetic stirrer equipped with a support rod and an external temperature probe (uniSTIRRER 3 pro, LLG LABWARE, Meckenheim, Germany). A hexagonal PTFE-coated stirrer bar (50 × 7 mm) was used to ensure uniform mixing throughout the extraction process. The obtained extracts were filtered, dried, and stored at 21 ± 1 °C until further measurements.

2.3. Total Phenolic (TPC) and Flavonoid (TFC) Content

The TPC in the dry extracts of blends of chamomile and feverfew was determined by a modified Folin–Ciocalteu method [25], adapted for 96-well microplates. Ethanol solutions (100 µL, 1 mg/mL) were mixed with Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent water solution (75 µL, 1:10 v/v) and sodium carbonate water solution (75 µL, 20% w/v). The reaction mixtures were incubated in the dark for 2 h, after which the absorbance was recorded at λmax = 765 nm on a BioTek Elisa Epoch 2 microplate reader (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Gallic acid was used to construct the calibration curve (0.1–1.6 mg/mL), and the results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of extract (mg GAE/g).

The TFC of the dry extracts was determined by a modified aluminum chloride colorimetric assay [26], adapted for 96-well microplates. Ethanol solutions (50 µL, 1 mg/mL) were mixed with sodium nitrite water solution (15 µL, 1 M) and vortexed for 30 s using a vortex mixer (Grant Bio PV-1 Vortex mixer, Shepreth, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom) with an equilibration time of 3 min. Subsequently, an aqueous aluminum chloride solution (15 µL, 10% w/v) was added to the mixture, followed by repeated mixing and equilibration. After 5 min, the water solution of sodium hydroxide (100 µL, 1 M) was added and mixing was repeated. Finally, the reaction mixture was kept in the dark for 30 min and the absorbance was read at λmax = 425 nm using a BioTek Epoch 2 ELISA microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Catechin was used to calculate the standard curve (25–400 µg/mL) and the results were expressed as micrograms of catechin equivalents (CE) per gram of extract (µg CE/g).

2.4. UHPLC Q-ToF MS Analysis

Considering that all blends contain different ratios of chamomile and feverfew, it can be assumed that all extracts contain similar phytochemical profiles but different relative abundance of extracted bioactive compounds. To understand the influence of temperature on extraction of bioactive compounds, chamomile/feverfew (1:3 w/w) blend extracts obtained by cold and heat-assisted extraction were chosen for comprehensive chromatographic analysis. Selected blend extracts were analyzed by the Agilent 1290 Infinity ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (6530C Q-ToF-MS) (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Stevens Creek Blvd, CA, USA). The method used for the analysis of the extracts was the previously established and reported UHPLC method (including mobile phase, gradient elution program, flow rate, and injection volume), with the same Q-ToF operating parameters [27]. Chromatographic separation was carried out at 40 °C, using a Zorbax C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm) (Agilent Technologies, Inc., CA, USA). The QToF-MS system was equipped with a Dual Agilent Jet Stream electrospray ionization (ESI) source, and extracts were recorded in both positive (ESI+) and negative (ESI-) ionization modes. The QToF-MS spectra were recorded in full-range acquisition from 100 to 1700 m/z, with a set scan rate of 2 Hz. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) was employed for suspect screening, using the Auto MS/MS acquisition mode (100–1700 m/z, 1 spectra/s, and 1000 ms/spectrum) and fixed collision energy (30 eV). Agilent MassHunter and MS-DIAL (ver. 4.60) software (http://prime.psc.riken.jp/, accessed on 1 November 2025) were used for data collection, evaluation, analysis, and presentation of MS data. All unknown compounds were tentatively identified based on their monoisotopic mass, MS fragmentation and additionally confirmed by comparison with available standards and/or data from the literature. Accurate masses of identified components and fragment ions were calculated using ChemDraw software (version 12.0, CambridgeSoft, Cambridge, MA, USA). The CAS SciFinder-n (https://scifindern.cas.org/, accessed on 1 November 2025) and PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 1 November 2025) databases were used to search for chemical compounds based on formulas and structures. Peak areas for each identified compound were normalized and exported from MS DIAL (5.1.0.2). software.

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

Due to the complex chemical composition of medicinal and aromatic plants, it is necessary to use different methods in order to determine their antioxidant capacity. The ABTS and DPPH antioxidant assays are characterized by the determination of the extracts’ ability to scavenge free radicals, thus reducing them into their inactive form and halting further oxidation, whereas CUPRAC and FRAP assays are employed to assess the extracts’ potential to be an elector donor, playing a key role in the mechanism of antioxidant action.

2.5.1. ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay

The radical scavenging activity (RSAABTS•+) of the extracts from chamomile and feverfew blends was evaluated using the ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) assay, adapted for 96-well microplates [28]. A potassium persulfate aqueous solution (88 µL, 2.45 mM) was added to ABTS aqueous solution (5 mL, 4 mg/mL) and left for 16 h to create ABTS radicals (ABTS•+). The working solution of ABTS•+ was prepared by diluting the stock solution 100-fold with 96% ethanol (v/v) to obtain an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.02 at λmax = 734 nm. An aliquot of 280 µL of ABTS•+ solution was mixed with a sample ethanol solution (20 µL, 1 mg/mL) and the absorbance was read (λmax = 734 nm) after 30 min of incubation in the dark at 21 ± 1 °C. A mixture of 96% ethanol (v/v) and ABTS•+ solution served as the control. Each measurement was performed in triplicate using a BioTek Epoch 2 ELISA microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The absorbance values were recorded and the RSAABTS•+ was calculated following the formula presented in Equation (1):

where Acontrol is the absorbance of the control solution and Asample was the absorbance of the appropriate test solution. A standard curve was prepared using Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) in concentrations ranging from 0.04 to 1 mg/mL. The results of RSAABTS•+ were expressed as millimoles of Trolox equivalent to the antioxidant capacity (TEAC) per gram of extract (mM TEAC/g).

RSAABTS•+ (%) = [(Acontrol (734 nm) − Asample (734 nm))/Acontrol (734 nm)] × 100

2.5.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

DPHH radical scavenging activity (RSADPPH•) was determined by the modified DPPH method previously described by Batinić et al. [29], adapted for 96-well microplates. The DPPH stock solution was prepared by dissolving 0.252 mg of DPPH (2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl) reagent in 9 mL of 96% ethanol (v/v). An aliquot of 280 µL of DPPH• solution was mixed with the sample ethanol solution (20 µL, 1 mg/mL) and the absorbance at λmax = 517 nm was read after 30 min of incubation of the reaction mixture in the dark at 21 ± 1 °C. The control consisted of freshly prepared DPPH• solution mixed with 70% ethanol (v/v) instead of the sample. Each measurement was performed in triplicate using a BioTek Epoch 2 ELISA microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The absorbance of each sample was recorded and the RSADPPH• was calculated using Equation (2):

where Acontrol is the absorbance of the control solution and Asample is the absorbance of the sample ethanol solution. A standard curve was prepared using Trolox (0.04–1 mg/mL) and the values of RSCDPPH• were expressed as millimoles of Trolox equivalents antioxidant capacity (TEAC) per gram of extract (mM TEAC/g).

RSADPPH• (%) = [(Acontrol (517 nm) − Asample (517 nm))/Acontrol (517 nm)] × 100

2.5.3. FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) Assay

The FRAP of the extracts of the chamomile and feverfew blends was determined according to the experimental procedure described by Sultana et al. [30], adapted for 96-well microplates. A concentrated ethanol extract (5 mg) was mixed with sodium phosphate buffer solution (100 µL, 0.2 M, pH 6.6) and potassium ferricyanide water solution (100 µL, 1% w/v). The reaction mixture was incubated overnight at 50 °C by using a digital thermostatic water bath (DK-2000-IIIL, Nantong Chem-Land Co., Ltd., Nantong, China). An aliquot of 50 µL of the incubated mixture was combined with 25 µL of trichloroacetic acid (10%, w/v) and the mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm, for 30 min, at 5 ± 0 °C in a refrigerated centrifuge (Centrifuge 5430R, Eppendorf®, Hamburg, Germany). The 70 µL of supernatant was decanted and diluted with 37.5 µL of distilled water and 17.5 µL of ferric chloride aqueous solution (0.1%, w/v). The absorbance of the final solution was read at λmax = 700 nm using a BioTek Epoch 2 ELISA microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). A standard curve was calculated using vitamin C in the concentration range of 0.15625–2.5 mg/mL. Results were expressed as micromoles of vitamin C equivalents antioxidant capacity (VCEAC) per gram of extract (µM VCEAC/g). All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were averaged.

2.5.4. Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC) Assay

The ability of chamomile and feverfew blend extracts to reduce cupric ions (Cu2+) was evaluated using the CUPRAC method as previously described by Milošević et al. [31], adapted for 96-well microplates. The assay mixture consisted of 90 µL of copper(II) chloride (10 mM), 90 µL of 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline, i.e., neocuproine (7.5 mM), 110 µL of ammonium acetate buffer solution (1 M, pH 7) and 10 µL of the sample solution (1 mg/mL). The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark at 22 ± 1 °C for 30 min. After incubation, the absorbance was read at λmax = 450 nm using a BioTek Epoch 2 ELISA microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). A standard curve was prepared using vitamin C in the concentration range 0.03125–0.5 mg/mL. The results were expressed as micromoles of vitamin C equivalent antioxidant capacity (VCEAC) per gram of extract (µM VCEAC/g). All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were averaged.

2.6. Antibacterial Activity

2.6.1. Bacterial Strains

Multidrug resistant isolates belonging to the ESKAPE group (Table 2) were used in this study. The isolates were not collected by the research team but were obtained directly from the hospital’s microbiology laboratory. These isolates had been routinely processed by the physicians (internists and surgeons) who are obliged, as part of standard diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, to collect swabs or other clinical materials from patients suspected of having hospital-acquired infections. All samples were therefore taken solely for clinical purposes, independently of this research, and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval of the Local Ethical Committee of University Hospital Center “Dr Dragiša Mišović−Dedinje”, Belgrade, Serbia [No. 15341/3-2025; 21 July 2025]. Upon completion of routine diagnostics, the microbiology specialist provided the research team exclusively with pure, identified bacterial isolates, without any patient identifiers or access to medical records. The research team had no involvement in patient sampling, clinical decision-making, or specimen collection procedures, nor did the microbiology specialist have insight into how swabs were taken, as this is not part of her professional responsibilities. Thus, only anonymized isolates, belonging to the hospital microbial flora, were used for experimental analyses.

Table 2.

Antibacterial susceptibility of isolates belonging to the ESKAPE group.

Identification of isolates and determination of their resistance profiles were performed using the Vitek 2 system (bioMerieux, Marcy I’Etoile, France). Antimicrobial resistance was interpreted according to the breakpoints established by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) were used for determining bacterial resistance.

After identification and characterization, the isolates were stored at –80 °C in the Microbiology Department, Department of Physical Chemistry, VINČA Institute of Nuclear Sciences–National Institute of the Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade.

2.6.2. Bacterial Cultivation

Bacterial cultivation was performed by streaking frozen stock cultures onto Mueller Hinton Agar plates (MHA, Torlak, Belgrade, Serbia), followed by incubation for 24 h at 37 °C. The bacterial inoculum used for further testing were adjusted to be 0.5 Mc Farland standard, corresponding to 1 × 108 CFU/mL.

2.6.3. Estimation of Antibacterial Potential

The antibacterial potential of the blends was assessed using the broth microdilution assay. For the selected bacterial isolates, 10% povidone iodine (0.98–125 mg/mL) was used as the positive control. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined according to the method previously described by Vasilijević et al. [32]. Briefly, blends were serially two-fold diluted in tryptic soy broth (TSB) across the columns of 96-well microtiter plates. All blends were tested over the same concentration range, i.e., 0.04–5 mg/mL. An inoculum containing 2 × 104 CFU/well (equivalent to a bacterial suspension of 1 × 105 CFU/mL) was added to each well after the serial dilution of the blends. After 24 h of incubation, resazurin (7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazine-3-one 10-oxide) was added as a growth indicator at a final concentration of 0.0675 mg/mL per well. Following an additional 3 h of incubation, MICs were determined as the lowest concentrations of the blends that prevent visible growth of bacteria, i.e., the lowest concentrations with no visible color change within the wells. MBCs were determined by plating of the aliquots (15 mL) from wells showing no visible growth onto Mueller–Hinton Agar plates. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data presented in the text were the mean values of three independent experimental measurements. The statistical analysis was performed by using one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s post hoc test (IBM SPSS Statistisc Data Editor 26) among the data from the tests used in this research. To assess the normality of the investigated samples, descriptive statistics and Levene statistics from Test of Homogeneity of Variances (p < 0.05, n = 3) were used. Also, the data in the table and diagrams are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content

Phenolic compounds, including both phenolic acids and flavonoids (in the form of free flavonoid glycosides and aglycones), are well known for their wide range of biological activities, particularly antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antienzymatic activities, making them important micronutrients in both food and feed applications. The content of polyphenols and their derivatives depends on several factors, including the polarity and concentration of the used solvent, the degree of polymerization of polyphenols, and chemical and physical interactions between phenolic compounds with other plant constituents, which may lead to the formation of insoluble complexes [33]. There is currently no universally accepted extraction method suitable for recovering all phenolic compounds from plant material. Commonly used solvents include polar chemicals such as water, methanol, ethanol, and their binary mixtures. The total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) were quantified based on calibration curves of gallic acid (y = 0.554x + 0.0619, R2 = 0.996) and catechin (y = 3.1765x + 0.1354, R2 = 0.9956). The results for different blend extracts of chamomile and feverfew are presented in Figure 3.

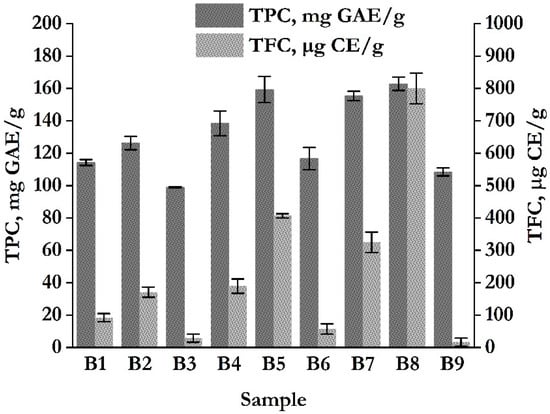

Figure 3.

Total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) of chamomile and feverfew blend extracts obtained by cold extraction (B1–B3), room temperature extraction (B4–B6), and heat-assisted extraction (B7–B9).

The results demonstrated a consistent trend in the variation in total polyphenol and flavonoid content across all tested samples. Notably, when the comparison is made from the standpoint of the employed extraction method, samples B7–B9, obtained via heat-assisted extraction (HAE), exhibited the highest level of both polyphenols and flavonoids compared to the other two extraction methods—cold extraction (B1–B3) and room temperature extraction (B4–B6). This outcome is anticipated, as elevated extraction temperatures are known to enhance the release of bioactive compounds from the plant cell structures and facilitate their dissolution in the extraction medium, thereby directly increasing the yield of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. In addition, 70% ethanol (v/v) as a polar solvent, exhibits a high affinity for polar compounds [34]. The 30% water content in the ethanol-water binary system plays a significant role, especially under elevated extraction temperatures, by reducing the dielectric constant of the solvent mixture. This reduction leads to decreased viscosity and surface tension, promoting faster and more efficient diffusion of bioactive constituents into the surrounding medium. Regarding the influence of herbal drug ratios within the blends, the 3:1 ratio in favor of chamomile proved to be most effective. Specifically, extracts B2, B5, and B8, corresponding to this ratio, yielded the highest polyphenol and flavonoid contents (126.29 mg GAE/g and 170.63 µg CE/g; 159.31 mg GAE/g and 406.74 µg CE/g; 162.85 mg GAE/g and 800.25 µg CE/g, respectively). This finding may be attributed to the rich phytochemical profile of chamomile, which contains various phenolic compounds, especially apigenin, luteolin, and their derivatives [1]. These classes of organic bio-constituents are more efficiently extracted in binary ethanol-water systems, particularly under elevated temperatures, and contribute substantially to the total phenolic and flavonoid content. Also, chamomile has a higher proportion of essential oil compounds and unipolar molecules, which are less readily extracted using 70% ethanol (v/v). Interestingly, the results for TFC at lower extraction temperatures align with findings reported by Foschi et al. [33], who observed that lower temperatures (<15 °C) favor the solubilization of glycosylated flavones and flavonols, while higher temperatures (>25 °C) enhance the extraction of phenolic acids. Accordingly, cold extraction yielded the lowest levels of both phenolic and flavonoid compounds, likely due to limited cell wall rupture and reduced tissue breakdown, in contrast to extraction methods conducted at room temperature or elevated temperatures. Results of ANOVA with Duncan post hoc tests are presented in Tables S1–S8. ANOVA results showed a statistically significant difference between all investigated samples (p < 0.05). Duncan post hoc test for TPC content showed that there was a statistically significant difference between samples prepared by different extraction methods (example B8 and B5 sample, B4 and B1, B9 and B1, B6 and B1, etc.), which means that the extraction temperature has a significant influence on total phenolic extraction yield. The maximum extraction yield is observed in the B8 sample. Results for TFC content showed a statistically significant difference across all samples, indicating that TFC content is extremely sensitive to extraction conditions and temperature. Statistically significant differences between all samples for TFC also showed that, in addition to extraction temperature, the ratio of chamomile to feverfew influences results, likely due to the different phytochemical profiles of both plants.

3.2. UHPLC Q-ToF MS Profile of Selected Blend Extracts

Phytochemical profiles of the chamomile/feverfew blends (1:3 w/w) extracted under extremely different temperature conditions (cold and heat-assisted extraction) are presented in Table 3. Untargeted analysis revealed a total of 43 compounds, which can be classified in the following groups: phenolic acids (compounds 1–12), flavonoids (compounds 13–33), phenylamides (compounds 35–37), sesquiterpene lactones (compounds 38–42), and other compounds (coumarin, 34; and abscisic acid, 43). All compounds were tentatively identified based on their exact mass and typical MS/MS fragments which are reported in Table 3. Some of the identified compounds were confirmed by comparison with available standards (these compounds are labeled in Table 3), while other compounds were additionally confirmed by data from the literature. Representative references related to the previous identification of these compounds in the Asteraceae family, especially Tanacetum (Tanacetum parthenium) and/or Matracaria (Matricaria chamomilla) species, are put in Table 3. The distribution and abundance of the identified compounds in the investigated extracts are reported in Table S9. A comparison of peak areas among samples was performed separately for each identified compound.

Table 3.

Identification and characterization of bioactive compounds (phenolic compounds, coumarins, phenylamides, sesquiterpens lactone, and sesquiterpenoids) in selected chamomile/feverfew blend extracts. Compound name, mean retention times (RT), molecular formula, calculated mass, m/z exact mass, mean mass accuracy (mDa), and MS fragments are presented in Table 3.

3.2.1. Phenolic Compounds

Hydroxybenzoic acids and its glycosides. Besides hydroxybenzoic acid (1), three isomers of dihydroxybenzoic acid (2–4) were also detected. Among them, dihydroxybenzoic acid is. I and dihydroxybenzoic acid is. II were identified by comparison with standards and recognized as protocatechuic acid (2) and gentisic acid (3), respectively. Compound 5 was identified as dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside, with typical fragments appearing at 152/153 m/z (deprotonated dihydroxybenzoic acid) and 108/109 m/z (-CO2). Mentioned compounds have been previously reported as constituents of the aerial parts of feverfew (T. parthenium) [6]. Hydroxycinnamic acid and derivatives represent the next subgroup of phenolic acids, with seven compounds identified in the examined blend extracts. Caffeic acid (6) was identified in free form, confirmed by comparison with standard, and recently it has also been reported in the extracts of German chamomile (M. chamomilla L.) [5]. Various caffeic acid derivatives were also identified, including caffeic acid glucuronide-methyl ester (8), caffeoylquinic acid, i.e., chlorogenic acid (9), and dicaffeoylquinic acid (10). These caffeic acid derivatives have been previously reported in both chamomile and feverfew and exhibit characteristic fragmentation patterns [5,31,48]. In addition, caffeic acid hexoside (7), ferulic acid hexoside (11), and caffeoyl-ferulic acid hexoside (12) were identified. Caffeic acid hexoside has been previously reported in T. parthenium [6], while ferulic acid hexoside has been found in Matricaria recutita L. [39]. This is the first report of caffeoyl-ferulic acid hexoside, which so far has not been detected in neither chamomile nor feverfew. This compound was detected based on typical fragments related to caffeic (179, 161, and 135 m/z) and ferulic (193, 149, 134 m/z) acid.

Flavonoids were the most abundant group, with 22 identified compounds, which can be divided into three subgroups: (I) flavonol aglycones (O-methylated flavonols), glycosides, and acyl derivatives; (II) flavone aglycones, glycosides, and acyl derivatives; and (III) those flavanones (eriodictyol). Except quercetin (13), other detected flavonol aglycones can be characterized as 3-O-methylated flavonol aglycones (14–19). Quercetin was identified based on typical fragments at 151 m/z [1,3A−], 178 m/z [1,2A−], 121 m/z [1,3B−], and 107 m/z [0,4A−] [49], and confirmed by comparison with the available standard. On the other hand, 3-O-methylated compounds present typical compounds that have been found in the genus Tanacetum L. [35,38], with unique monoisotopic masses and typical fragments obtained by sequential loss of several methyl groups (two, three, or four) and neutral loss of CO (−28 Da). According to our knowledge, this is the first report about quercetin dimethyl ether (15) and its presence in chamomile and/or feverfew. Compounds 14, 16, 17, 18, and 19 are structurally related compounds identified as ermanin, santin, axillarin, centaureidin, and casticin, respectively, and were previously reported in feverfew [35,38]. In addition to aglycones, several glycosides were identified and recognized as quercetin 3-O-glucoside (20), quercetagetin 7-O-glucoside (21), and patuletin 7-O-hexoside (22). These glycosides showed typical fragments (deprotonated aglycones) which were obtained by loss of hexosyl (glucosyl) unit (−162 Da). Compound 23 was identified as patuletin 7-O-(6″-O-caffeoyl)hexoside (655 m/z) with main fragments appearing at 493 m/z, 331 m/z, and 316 m/z, obtained by sequential loss of caffeoyl moiety, hexosyl unit, and methyl group. This compound has been previously reported in yellow chamomile (Anthemis tinctoria) [40].

Flavone aglycones, glycosides, and acyl derivatives present characteristic compounds derived from chamomile, as previously reported by various studies [5,37,41,42,43]. Except compound 25, other identified compounds from this group correspond to apigenin (24) and luteolin (26), their glucosides (27 and 28), and acyl derivatives (29–32). Apigenin (117 m/z [1,3B−],), luteolin (133 m/z [1,3B−]), and their glycosides were identified based on typical fragments [49], and they were additionally confirmed with available standards. Compound 25 is an unknown isomer of apigenin, with the same exact mass (269 m/z), formula (C15H9O5−), and similar fragmentation pattern but with a different elution time, and it is characterized as trihydroxyflavone. Particularly interesting compounds were apigenin acyl derivatives, which were recorded in both positive and negative modes. The main fragments for these apigenin derivatives was radical anion/deprotonated (268/269 m/z) or protonated (271 m/z) apigenin aglycone, depending on the applied ionization mode. Other fragments were obtained by loss of acetyl (29), malonyl (31 and 32), or caffeoyl units (30), depending on the apigenin derivatives. Proposed structures of identified apigenin acyl derivatives are presented at Figure 4. Some identified flavones, such as apigenin, luteolin, and apigetrin, have been shown to possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [50,51,52]. In other flavonoids, only flavanone eriodictyol was detected, based on typical fragments at 151 m/z [1,3A−], 135 m/z [1,3B−], 125 m/z [1,4A−], and 107 m/z [0,4A−], obtained by retro Diels–Alder reaction. Eriodictyol was previously reported in Tanacetum parthenium [35]. Compound 34 was identified as daphnetin 7-O-glucoside (daphin) and belongs to a subgroup of coumarin glycosides. This compound showed the main fragment at 177 m/z (deprotonated daphnetin), obtained by loss of glucosyl unit. Coumarins and concretely daphnin present typical compounds derived from chamomile [44].

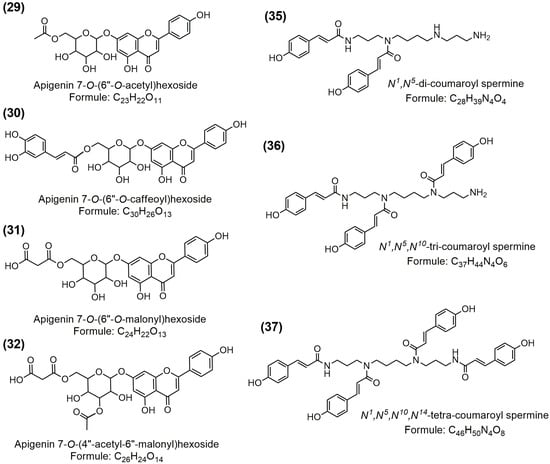

Figure 4.

Proposed structure of apigenin acyl derivatives and phenylamides identified in the analyzed chamomile/feverfew blend extracts (for compounds annotation see Table 3).

3.2.2. Phenylamides

In addition to phenolic compounds, phenylamides (phenolic acid-polyamine derivatives) were also found in prepared chamomile/feverfew extracts. In this study, spermine derivatives containing two, three, and four coumaroyl moieties were identified in positive ionization mode. Phenylamides have been previously reported as main bioactive compounds present in pollen grains [53,54,55], which explains their presence in the blend containing chamomile and feverfew flowers. As phenylamides exhibit a typical MS fragmentation in positive ionization mode, with some typical fragments, their structure can be predicted [53,54,55]. For structure elucidation, the following fragments were the most important: (a) fragments indicating on coumaroyl moiety (147 m/z and 119 m/z); (b) fragments obtained by loss of coumaroyl moiety/moieties (349 m/z; 495 m/z; or 641 m/z); (c) fragments obtained by the cleavage of spermine core containing the coumaroyl moiety/moieties (204 m/z; 275 m/z; 218 m/z; 421 m/z; 521 m/z); and (d) low intensity fragment obtained by loss of NH3 indicating on rearrangement of coumaroyl moiety in spermine core [53,54]. In this case, coumaroyl moieties were attached to the terminal and central nitrogen atoms of the spermine core. Considering mentioned fragments and previously reports related to tentative identification of phenylamides [27,53], these compounds were recognized as N1,N5-di-coumaroyl spermine (35), N1,N5,N10-tri-coumaroyl spermine (36), and N1,N5,N10,N14-tetra-coumaroyl spermine (37). Some previous studies have also found phenylamides in chamomile [36] and other species from the Asteraceae family [56] and have indicated their effectiveness against neurological disorders and cancer [56,57]. It can be assumed that these compounds also contribute to the biological, and more specifically the antioxidant activity of the prepared extracts in this study. Proposed structure of the identified spermine derivatives are shown at Figure 4.

3.2.3. Sesquiterpene Lactones

Sesquiterpene lactones are well-known compounds derived from the Tanacetum species. In this study, five lactone compounds were detected, while only three were identified by comparison with the standard or literature data. Compound 38 was recognized as (−)-dehydrocostus lactone, based on its monoisotopic mass and MS fragmentation [46,58]. Further, parthenolide is the main constituent in feverfew and in medicine the most important antimigraine compound [48,59]. Parthenolide was identified in its dehydro form (-H2O) at 231 m/z (main fragment of parthenolide), due to its unstable epoxy group that can obviously easily cleavage in an ionic source. However, an ESI scan of the parthenolide peak recorded the exact mass of parthenolide at m/z 249. Parthenolide was additionally confirmed by comparison with standards which showed the same behavior under the applied ionization conditions. Costunolide is known as the main natural precursor of parthenolide; however, this compound has been shown to possess strong anticancer activity [58,60]. Compound 41 was identified as costunolide, with unique exact mass and typical fragments [46,58]. Considering obtained fragments and predicted formulas, compounds 39 and 42 obviously belong to sesquiterpene lactone, but these compounds were not recognized and they were labeled as unknown sesquiterpene lactones.

Considering obtained profiles, all identified compounds were independently found in both extracts, by applied temperature of extraction. However, relative abundance and distribution of individually bioactive compounds varied in the extracts, probably due to extraction conditions and applied temperature regimes. Mutual comparison of the peak areas for each identified compound clearly shows the difference in bioactive compound abundances among extracts (Table S1). For examples, mutual comparison of B9 and B3 extracts showed the following: (I) higher abundance of all hydroxybenzoic acids and glycosides, caffeic acid derivatives and glycosides, flavonol glycosides, apigenin and luteolin and their derivatives, and coumarin and phenylamides in the B9 extract (heat-assisted extraction); (II) higher abundance of all flavonol aglycones and sesquiterpene lactones in the B3 extract (cold extraction). Finally, the relative abundance and distribution of bioactive compounds obviously contributes to differences in the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the analyzed blend extracts and their further applications.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of Prepared Blend Extracts

It is well known that no single analytical method can comprehensively assess antioxidant activity due to the complexity of the reaction mechanisms involved in biological systems [35,36]. Therefore, in this study, four widely accepted spectrophotometric assays were employed, each based on distinct reaction principles. The antioxidant potential of the chamomile and feverfew blend extracts was evaluated using the DPPH and ABTS assays, while their reducing capacity was accessed via the CUPRAC assay, which measures the reduction of copper(II) ions (Cu2+) to copper(I) ions (Cu+) in the presence of the inorganic ligand neocuproine, and the FRAP assay, which quantifies the reduction of ferric ions (Fe3+) to ferrous ions (Fe2+) in the presence of TPTZ (2,4,6,-tripyridyl-s-triazine).

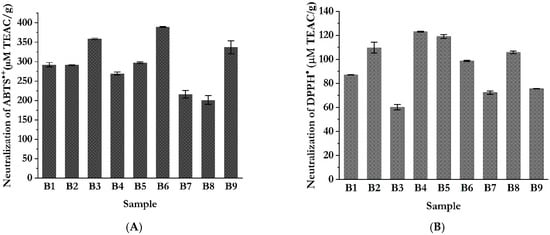

A notably higher antioxidant activity (Figure 5), as measured by ABTS assay (Figure 5A), was observed in samples B3, B6, and B9, all of which were prepared using blends with a 3:1 ratio in favor of chamomile. This result may be attributed to the phytochemical profile of chamomile, which is known to contain a variety of glycosylated flavonoids, particularly apigenin derivatives, as well as phenolic acids such as chlorogenic and caffeic acids, all of which are recognized for their strong radical scavenging potential [61]. Furthermore, these extracts were obtained under milder extraction conditions (cold extraction at 4 °C and room temperature extraction at 22 °C), which likely contributed to the preservation of thermolabile antioxidant compounds. It is well documented that elevated extraction temperatures can induce the degradation of the structural transformation of sensitive bioactive molecules, particularly hydrophylic flavonoid glycosides, thereby reducing their antioxidant capacity [61].

Figure 5.

In vitro antioxidant activity of extracts of blends of chamomile and feverfew evaluated by the free radical scavenging methods; (A) ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) assay; (B) DPPH (2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl) assay.

When the radical scavenging ability was assessed using the DPPH assay (Figure 5B), the results showed a notable correlation with both the TPC and TFC of the extracts. When looking at the results, with the aim of finding the best ratio of the two used plant materials in the blends, the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity was observed in extracts obtained from blend formulations containing feverfew and chamomile in a 3:1 ratio, favoring feverfew. This observation can be attributed to the phytochemical profile of feverfew, which, as previously discussed, is particularly rich in both phenolic acids and flavonoid compounds, as well as phenylamides [62,63]. In terms of extraction conditions, the most pronounced DPPH radical scavenging activity was recorded in extracts obtained at room temperature (25 °C), with values reaching up to 123.04 µmol TEAC/g. This finding suggests that moderate temperatures, combined with mild agitation, are sufficient to facilitate the effective release of antioxidant compounds from plant matrices, while also minimizing the thermal degradation of sensitive bioactive molecules. These conditions appear to provide a favorable balance between extraction efficiency and compound stability, which may be compromised under more intensive thermal extraction regimes.

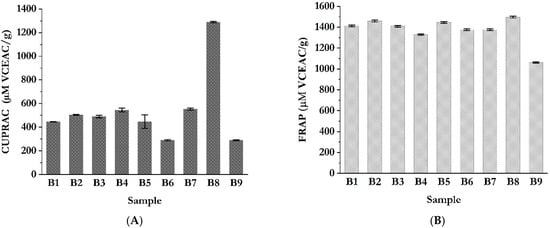

When antioxidant activity was assessed based on the extracts’ ability to reduce copper ions (Figure 6) determined by CUPRAC assay (Figure 6A), no significant differences were observed among the extraction methods performed at lower temperatures (Figure 5A). However, an exception was recorded for sample B8, obtained using HAE from a blend with a 3:1 ratio in favor of feverfew. This extract exhibited a notably higher capacity for copper ion reduction, reaching a value of 1288.95 ± 5.55 µM VCEAC/g. The pronounced CUPRAC activity observed in sample B8 may be attributed to its higher content of the specific bioactive constituents characteristic of feverfew, such as flavonoids and sesquiterpene lactones. These compounds are more efficiently extracted under elevated temperature conditions, which facilitate the disruption of plant cell walls and enhance the solubility and diffusion of antioxidant molecules [64]. As a result, their increased availability contributes to a more effective reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ ions in the CUPRAC assay.

Figure 6.

In vitro antioxidant activity of blend extracts of chamomile and feverfew evaluated by the metal ion-reducing antioxidant power assay; (A) CUPRAC (cupric power-reducing antioxidant capacity) assay; (B) FRAP (ferric-reducing antioxidant power) assay.

The highest FRAP activity was observed in the sample B8, reaching a value of 1496.32 ± 8.49 µM VCEAC/g (Figure 6B). In terms of extraction conditions, lower temperature regimes appeared to favor the metal-chelating and ferric ion-reducing capacities of the chamomile/feverfew blend extracts. This outcome may be attributed to the improved preservation of thermolabile antioxidant constituents, which tend to degrade under high-temperature extraction protocols. Due to a lack in the literature specifically addressing the FRAP activity chamomile/feverfew blends, direct comparisons are limited. However, several recent studies have reported the antioxidant properties of individual extracts of chamomile and feverfew, supporting the observed trends in ferric ion-reducing potential [21,33,64,65].

When comparing the antioxidant potential of the tested blend extracts with standard antioxidant compounds such as vitamin C or Trolox, distinct trends were observed. In radical scavenging assays (ABTS and DPPH), the chamomile/feverfew blends demonstrated considerably lower antioxidant activity—ranging from 2.5- to 8-fold lower than the reference vitamin C standard. Conversely, in metal ion-reducing assays (CUPRAC and FRAP), the extracts exhibited comparable or even superior antioxidant performance, with values approximately 1.2- to 1.5-fold higher than the standards [65,66]. These results suggest that the chamomile/feverfew blends possess antioxidant potential primarily driven by their capacity to reduce transition metal ions, rather than direct free radical scavenging. This could be linked to the specific chemical profile of the blend, including flavonoids and sesquiterpene lactones that are particularly reactive in the reaction mechanism involving metal ions.

The results of Duncan’s post hoc test for these antioxidant tests are presented in Tables S6–S9. Results for DPPH showed a statistically significant difference among all sample groups, indicating that the extraction temperature and the chamomile-to-feverfew ratio in blends have a strong influence on DPPH assays and that the high variability between samples prepared with the same extraction method persists. The Duncan post hoc test for FRAP assays showed that the B9 sample has a statistically significant difference from the other samples; for the CUPRAC assays, the B8 sample; and for the ABTS assays, the B6 and B3 samples. Based on the Duncan post hoc analysis for these four assays, it can be concluded that heat-assisted extraction and the ratio of chamomile and feverfew (1:3) are the most optimal conditions for obtaining an extract with the highest reducing power (FRAP and CUPRAC tests). On the other hand, extraction at room temperature and the ratio of chamomile and feverfew (1:1 and 1:3) are the most optimal for obtaining extracts with the highest ability to neutralize radicals (DPPH and ABTS assays). High extraction temperature affects free radical degradation, resulting in low ABTS and DPPH values.

3.4. Antibacterial Potential of Prepared Blend Extracts

In the third part of this study, the antibacterial potential of chamomile/feverfew blends extracts was evaluated against a panel of multidrug resistant (MDR) bacterial isolates (Table 4). The selection of these strains as model organisms is in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) warning that antimicrobial resistance contributes to over two million deaths annually in the United States alone. The tested MDR strains included both Gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative species (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.), all of which exhibited resistance to at least three different antibiotic classes. The results revealed pronounced antibacterial activity of all tested blends, irrespective of the extraction method or plant ratio. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranged from 0.625 to 2.5 mg/mL, while the minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were typically two-fold higher than MICs, and in some cases exceeded 5.0 mg/mL. These findings indicate a notable inhibitory effect of the extracts, with moderate bactericidal activity. Interestingly, neither the extraction method nor the specific blend composition significantly influenced the overall antibacterial potency. Interestingly, although tested isolates belong to different species and have different susceptibility patterns, substantial variations in their sensitivity to tested blends was not observed. Notably, the tested blends demonstrated significantly greater inhibitory and bactericidal activity compared to the positive control (10% povidone-iodine). This suggests that the chamomile/feverfew combinations may serve as promising candidates for the development of alternative antimicrobial agents, particularly in the context of increasing resistance to conventional antibiotics.

Table 4.

Antibacterial potential of blend extracts of chamomile and feverfew expressed as MIC and MBC (mg/mL).

Several studies have investigated the antimicrobial activity of individual hydroethanolic or alcoholic extracts of chamomile and feverfew, though typically against non-MDR bacterial strains. Michalak et al. [20] reported that feverfew and hydroethanolic extracts from different feverfew plant parts exhibited moderate inhibitory activity against S. aureus and E. faecalis, with MIC values ranging from 1 to 4 mg/mL. Similarly, Afshin et al. [67] reported a MIC of 12.5 mg/mL for feverfew extract against non-MDR S. aureus, which is approximately 10–20 times less potent than the activity observed for the blends tested in this study. To the best of our knowledge, no data are currently available regarding the antibacterial activity of feverfew hydroethanolic extracts against MDR K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., or Enterobacter spp. However, studies involving methanolic extract suggest MICs in the range 12–25 mg/mL against Acinetobacter spp., and Klebsiella spp., indicating significantly lower antimicrobial potential compared to our tested blends. Regarding chamomile, ethanolic extracts were previously evaluated against MRSA and MDR P. aeruginosa, and MICs were in the ranges between 6.25 and 25 mg/mL [68,69]. For Klebsiella spp. [68], inhibitory concentrations of chamomile ethanolic extracts ranged from 1 mg/mL [70] to 8 mg/mL [71], while MIC values against E. faecalis were as high as 32 mg/mL [71]. Collectively, these findings underscore the superior antibacterial efficacy of the tested chamomile/feverfew blends compared to individual alcoholic extracts of either plant. The enhanced activity may be attributed to synergistic or additive effects of bioactive constituents present in the combined extracts, as well as potential interactions between phytochemicals that enhance membrane permeability or target multiple bacterial pathways simultaneously.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of chamomile and feverfew blend extracts, with special focus on extraction and applied temperature regimes, to obtain superior herbal extracts with the best functional properties. To achieve this, prepared (selected) blend extracts were characterized by spectrophotometry and UHPLC Q-ToF MS and subjected to antioxidant and antimicrobial assays/tests. The results demonstrated that extracts obtained through heat-assisted extraction (HAE, 63 ± 1 °C) contained the highest levels of polyphenols and flavonoids. UHPLC-QToF-MS analysis revealed 43 bioactive compounds, which were present in both analyzed extracts (B3-cold extraction and B9-heat-assisted extraction). However, all identified compounds showed different distributions and abundances among the extracts, probably due to extraction conditions and applied temperature regimes. These variations in the compositions of the extracts probably contributed to their antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Strongest radical-scavenging and metal-reducing capacities were observed for extracts derived from chamomile/feverfew blend in a 1:3 ratio. The ANOVA with Duncan post hoc analysis confirmed that the extraction temperature and chamomile feverfew ratio have an influence on obtaining extracts with higher phenolic and flavonoid content and antioxidant activity. Notably, despite differences in phenolic content and antioxidant capacity, all extract blends exhibited potent and comparable antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis) and Gram-negative (K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii) multidrug-resistant strains. These findings highlight the potential of chamomile/feverfew blends and extracts, particularly those obtained via moderate-to-high temperature extraction, can be promising candidates for natural antioxidant and antimicrobial formulations. Future studies should focus on conducting toxicological evaluations to ensure that the investigated extracts meet international standards and regulations in the fields of food, medicine, and related disciplines.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/compounds5040060/s1. Table S1. Levene Statistics from the Test of Homogeneity of Variances. p > 0.05, all variances are homogeneous; Table S2. Results for one-way ANOVA for samples B1–B9 and different tests. The p value is <0.05 for all groups, which means there is a statistically significant difference between groups; Table S3. Duncan post hoc test homogeneous subset for total phenolic content (TPC); Table S4. Duncan post hoc test homogeneous subset for total flavonoid content (TFC); Table S5. Duncan post hoc test homogeneous subset for DPPH; Table S6. Duncan post hoc test homogeneous subset for FRAP; Table S7. Duncan post hoc test homogeneous subset for CUPRAC; Table S8. Duncan post hoc test homogeneous subset for ABTS; Table S9. Distribution and abundance of identified compounds in B3 and B9 extracts. Comparison of peak areas among samples for each identified compound separately.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B. and J.M.; methodology, P.B., N.Č. and J.M.; software, P.B., N.Č., J.M., M.P. and D.M. validation, P.B., N.Č. and J.M.; formal analysis, P.B., N.Č., J.M. and S.Č.; investigation, P.B., N.Č., J.M. and S.Č., M.P. and D.M.; resources, P.B., J.M. and A.K.; data curation, P.B., N.Č., J.M., S.Č., M.P. and D.M.; writing—original draft P.B., N.Č., J.M., S.Č., A.K., M.P. and D.M.; Visualization, P.B.; Supervision: M.P. and T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (451-03-136/2025-03/200003, 451-03137/2025-03/200116, 451-03-136/2025-03/200017, and the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, #GRANT No. 7744714, FUNPRO).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The approval was granted pursuant to Article 73 of the Law on Medicines and Medical Devices (“Official Gazette of RS”, No. 30/2010, 107/2012, 113/2017—other laws, and 105/2017—other laws) and Article 132 of the Law on Health Care (“Official Gazette of RS”, No. 25/2019). The request submitted by Stanislava Čukić, medical doctorspecialist in microbiology, Department of Laboratory Diagnostics for the provision of multidrug-resistant ESCAPE group isolates previously obtained through routine hospital procedures within the Department of Microbiology was reviewed and approved for use in scientific research in line with all relevant ethical and legal standards.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee of University Hospital Center “Dr Dragiša Mišović–Dedinje”, Belgrade. As the collection of the study material originated from routine procedures, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethical Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) assay |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl reagent |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay |

| CUPRAC | Cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity assay |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentration |

References

- Pareek, A.; Suthar, M.; Rathore, G.S.; Bansal, V. Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.): A Systematic Review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanos, R.; Stice, S.A. German Chamomile. In Nutraceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.J.; Heptinstall, S.; Mitchell, J.R.A. Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Feverfew in Migraine Prevention. Lancet 1988, 332, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heptinstall, S.; Williamson, L.; White, A.; Mitchell, J.R.A. Extracts of Feverfew Inhibit Granule Secretion in Blood Platelets and Polymorphonuclear Leucocytes. Lancet 1985, 325, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou, N.S.; Megremi, S.F.; Tarantilis, P. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity, Toxicity, and Phenolic Profile of Aqueous Extracts of Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) and Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Prepared at Different Temperatures. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenzadeh, F.; Chehregani, A.; Amiri, H. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity of Essential Oils of Tanacetum Parthenium in Different Developmental Stages. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé-Antonio, A.; Martínez-Ceja, A.; Romero-Estrada, A.; Sánchez-Carranza, J.N.; Columba-Palomares, M.C.; Rodríguez-López, V.; Meza-Contreras, J.C.; Silva-Guzmán, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, J.M. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Randia aculeata L. Cell Culture Extracts, Characterization, and Evaluation of Antibacterial and Antiproliferative Activity. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Kim, S.L.; Park, Y.R.; Lee, S.-T.; Kim, S.W. Parthenolide Promotes Apoptotic Cell Death and Inhibits the Migration and Invasion of SW620 Cells. Intest. Res. 2017, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Znajdek-Awizeń, P.; Gawron-Gzella, A. Studies on the Antimigraine Action of Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch. Bip.). Wiad. Lek. 2013, 66, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sztiller-Sikorska, M.; Czyz, M. Parthenolide as Cooperating Agent for Anti-Cancer Treatment of Various Malignancies. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, A.; Naseef, P.P.; Kuruniyan, M.S.; Jain, G.K.; Zakir, F.; Aggarwal, G. A Comprehensive Study of Therapeutic Applications of Chamomile. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Niu, F.-J.; Li, K.-W.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.-Z.; Gao, L.-N. Chamomile: A Review of Its Traditional Uses, Chemical Constituents, Pharmacological Activities and Quality Control Studies. Molecules 2023, 28, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadic, V.; Zivkovic, J.; Bigovic, D.; Zugic, A. Variation of Parthenolide and Phenolic Compounds Content in Different Parts of Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schulz Bip., Asteraceae during 18 Months Storage. Lek. Sirovine 2019, 39, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heptinstall, S.; Awang, D.V.C.; Dawson, B.A.; Kindack, D.; Knight, D.W.; May, J. Parthenolide Content and Bioactivity of Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schultz-Bip.). Estimation of Commercial and Authenticated Feverfew Products. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Johnson, I.T.; Saltmarsh, M. Polyphenols: Antioxidants and Beyond. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 215S–217S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.M.; Karboune, S. Combinatorial Interactions of Essential Oils Enriched with Individual Polyphenols, Polyphenol Mixes, and Plant Extracts: Multi-Antioxidant Systems. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as Antimicrobial Agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Sulaiman, I.S.; Basri, M.; Fard Masoumi, H.R.; Chee, W.J.; Ashari, S.E.; Ismail, M. Effects of Temperature, Time, and Solvent Ratio on the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds and the Anti-Radical Activity of Clinacanthus nutans Lindau Leaves by Response Surface Methodology. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszowy-Tomczyk, M. Synergistic, Antagonistic and Additive Antioxidant Effects in the Binary Mixtures. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 63–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Stryjecka, M.; Żarnowiec, P.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Kiełtyka-Dadasiewicz, A. Chemical Composition of Extracts from Various Parts of Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.) and Their Antioxidant, Protective, and Antimicrobial Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanović, A.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Zeković, Z.; Savić, S.; Vulić, J.; Mašković, P.; Ćetković, G. Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant, Antimicrobiological and Cytotoxic Activities of Native and Fermented Chamomile Ligulate Flower Extracts. Planta 2015, 242, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, B.; Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E. Feverfew for Preventing Migraine. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2020, CD002286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Chawla, P. Curative Properties of Chamomile in Gastrointestinal Disorders. In Herbs, Spices, and Medicinal Plants for Human Gastrointestinal Disorders; Apple Academic Press: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2022; pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebrolu, K.K.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Jifon, J.; Patil, B.S. Optimization of Flavanones Extraction by Modulating Differential Solvent Densities and Centrifuge Temperatures. Talanta 2011, 85, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. ISBN 0076-6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraim, A.M.; Ahmed, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hijji, Y.M. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content by Aluminum Chloride Assay: A Critical Evaluation. LWT 2021, 150, 111932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinčić, D.D.; Vidović, B.B.; Gašić, U.M.; Milenković, M.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Stanojević, S.P.; Ilić, T.; Pešić, M.B. A Systematic UHPLC Q-ToF MS Approach for the Characterization of Bioactive Compounds from Freeze-Dried Red Goji Berries (L. barbarum L.) Grown in Serbia: Phenolic Compounds and Phenylamides. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 140044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čutović, N.; Marković, T.; Kostić, M.; Gašić, U.; Prijić, Ž.; Ren, X.; Lukić, M.; Bugarski, B. Chemical Profile and Skin-Beneficial Activities of the Petal Extracts of Paeonia tenuifolia L. from Serbia. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinić, P.; Jovanović, A.; Stojković, D.; Čutović, N.; Cvijetić, I.; Gašić, U.; Carević, T.; Zengin, G.; Marinković, A.; Marković, T. A Novel Source of Biologically Active Compounds–The Leaves of Serbian Herbaceous Peonies. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, B.; Anwar, F.; Ashraf, M. Effect of Extraction Solvent/Technique on the Antioxidant Activity of Selected Medicinal Plant Extracts. Molecules 2009, 14, 2167–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, M.D.; Marinković, A.D.; Petrović, P.; Klaus, A.; Nikolić, M.G.; Prlainović, N.Ž.; Cvijetić, I.N. Synthesis, Characterization and SAR Studies of Bis (Imino) Pyridines as Antioxidants, Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Antimicrobial Agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 102, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilijević, B.; Mitić-Ćulafić, D.; Djekic, I.; Marković, T.; Knežević-Vukčević, J.; Tomasevic, I.; Velebit, B.; Nikolić, B. Antibacterial Effect of Juniperus communis and Satureja montana Essential Oils against Listeria monocytogenes in Vitro and in Wine Marinated Beef. Food Control 2019, 100, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, M.; Marsili, L.; Luciani, I.; Gornati, G.; Scappaticci, C.; Ruggieri, F.; D’Archivio, A.A.; Biancolillo, A. Optimization of the Cold Water Extraction Method for High-Value Bioactive Compounds from Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) Flower Heads Through Chemometrics. Molecules 2024, 29, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitwell, C.; Sen Singh, I.; Luke, C.; Kakoma, M.K. A Review of Modern and Conventional Extraction Techniques and Their Applications for Extracting Phytochemicals from Plants. Sci. Afr. 2023, 19, E01585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Cvetanović, A.; Gašić, U.; Stupar, A.; Bulut, G.; Şenkardes, I.; Dogan, A.; Sinan, K.I.; Uysal, S.; Aumeeruddy-Elalfi, Z. Modern and Traditional Extraction Techniques Affect Chemical Composition and Bioactivity of Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch. Bip. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 146, 112202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Angelis, M.; Amicucci, C.; Banchelli, M.; D’Andrea, C.; Gori, A.; Agati, G.; Brunetti, C.; Matteini, P. Rapid Determination of Phenolic Composition in Chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivelika, N.; Irakli, M.; Mavromatis, A.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Karioti, A. Phenolic Profile by HPLC-PDA-MS of Greek Chamomile Populations and Commercial Varieties and Their Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2021, 10, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Sauleau, P.; David, B.; Lavaud, C.; Cassabois, V.; Ausseil, F.; Massiot, G. Bioactive Flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium Revisited. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulinacci, N.; Romani, A.; Pinelli, P.; Vincieri, F.F.; Prucher, D. Characterization of Matricaria recutita L. Flower Extracts by HPLC-MS and HPLC-DAD Analysis. Chromatographia 2000, 51, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterova, I.; Grancai, D.; Grancaiova, Z.; Pour, M.; Ubik, K. A New Flavonoid: Tinctosid from Anthemis tinctoria L. Pharmazie 2005, 60, 956–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrič, D.; Mravčáková, D.; Kucková, K.; Čobanová, K.; Kišidayová, S.; Cieslak, A.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Váradyová, Z. Effect of Dry Medicinal Plants (Wormwood, Chamomile, Fumitory and Mallow) on in Vitro Ruminal Antioxidant Capacity and Fermentation Patterns of Sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švehlíková, V.; Repčák, M. Apigenin Chemotypes of Matricaria chamomilla L. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2006, 34, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švehlíková, V.; Bennett, R.N.; Mellon, F.A.; Needs, P.W.; Piacente, S.; Kroon, P.A.; Bao, Y. Isolation, Identification and Stability of Acylated Derivatives of Apigenin 7-O-Glucoside from Chamomile (Chamomilla recutita [L.] Rauschert). Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2323–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruľová-Poracká, V.; Repčák, M.; Vilková, M.; Imrich, J. Coumarins of Matricaria chamomilla L.: Aglycones and Glycosides. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Gao, W.; Qu, Z.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C. Pharmacokinetic Study on Costunolide and Dehydrocostuslactone after Oral Administration of Traditional Medicine Aucklandia lappa Decne. by LC/MS/MS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Guo, X.; Yan, C. Study on the Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Costunolide and Dehydrocostus Lactone in Rats by HPLC-UV and UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2014, 28, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Manzano, D.; Tanić, N.; Pesic, M.; Bankovic, J.; Pateraki, I.; Ricard, L.; Ferrer, A.; de Vos, R.; van de Krol, S. Elucidation and in Planta Reconstitution of the Parthenolide Biosynthetic Pathway. Metab. Eng. 2014, 23, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.E.; Tosun, F.; Gülpınar, A.R.; Kartal, M.; Duran, A.; Mihoglugil, F.; Akalgan, D. LC–MS Quantification of Parthenolide and Cholinesterase Inhibitory Potential of Selected Tanacetum L. (Emend. Briq.) Taxa. Phytochem Lett 2015, 11, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rijke, E.; Out, P.; Niessen, W.M.A.; Ariese, F.; Gooijer, C.; Brinkman, U.A.T. Analytical Separation and Detection Methods for Flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1112, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangar, S.P.; Kajla, P.; Chaudhary, V.; Sharma, N.; Ozogul, F. Luteolin: A Flavone with Myriads of Bioactivities and Food Applications. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailänder, L.K.; Lorenz, P.; Bitterling, H.; Stintzing, F.C.; Daniels, R.; Kammerer, D.R. Phytochemical Characterization of Chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) Roots and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential. Molecules 2022, 27, 8508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostić, A.Ž.; Çobanoğlu, D.N.; Milinčić, D.D.; Felek, I.; Düzdaban, P.; Pešić, M.B. Could Phenylamides Emerge as a Powerful Chemotaxonomic Tool? A Case Study of Rapeseed Bee-Collected Pollen Originating from Serbia and Türkiye. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202500339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotirić Akšić, M.M.; Pešić, M.B.; Pećinar, I.; Dramićanin, A.; Milinčić, D.D.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Gašić, U.; Jakanovski, M.; Kitanović, M.; Meland, M. Diversity and Chemical Characterization of Apple (Malus sp.) Pollen: High Antioxidant and Nutritional Values for Both Humans and Insects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Dong, J.; Haubruge, E.; Zhang, H. Phenolamide and Flavonoid Glycoside Profiles of 20 Types of Monofloral Bee Pollen. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Gai, Y.; Chu, W.-J.; Qin, G.-W.; Guo, L.-H. A Novel Compound N1, N5-(Z)-N10-(E)-Tri-p-Coumaroylspermidine Isolated from Carthamus tinctorius L. and Acting by Serotonin Transporter Inhibition. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 19, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Song, K.; Kim, Y.S. Tetra-Cis/Trans-Coumaroyl Polyamines as NK1 Receptor Antagonists from Matricaria chamomilla. Planta Medica Int. Open 2017, 4, e43–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Hu, H. Antitumor Activity and Mechanism of Costunolide and Dehydrocostus Lactone: Two Natural Sesquiterpene Lactones from the Asteraceae Family. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassorelli, C.; Greco, R.; Morazzoni, P.; Riva, A.; Sandrini, G.; Nappi, G. Parthenolide Is the Component of Tanacetum parthenium That Inhibits Nitroglycerin-Induced Fos Activation: Studies in an Animal Model of Migraine. Cephalalgia 2005, 25, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdi, M.; Liu, Q.; Karimzadeh, G.; Malboobi, M.A.; Beekwilder, J.; Cankar, K.; de Vos, R.; Todorović, S.; Simonović, A.; Bouwmeester, H. Biosynthesis and Localization of Parthenolide in Glandular Trichomes of Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L. Schulz Bip.). Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1739–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, M.V.; Rinaldi, F.; Tullio, V.; Gasperi, V.; Savini, I. Comparative Analysis of Phenolic Composition of Six Commercially Available Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) Extracts: Potential Biological Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Shahzad, N.; Kim, C.K. Structure-Antioxidant Activity Relationship of Methoxy, Phenolic Hydroxyl, and Carboxylic Acid Groups of Phenolic Acids. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.M.; Borges, F.; Guimarães, C.; Lima, J.L.F.C.; Matos, C.; Reis, S. Phenolic Acids and Derivatives: Studies on the Relationship among Structure, Radical Scavenging Activity, and Physicochemical Parameters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2122–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marete, E.N.; Jacquier, J.-C.; O’Riordan, D. Effect of Processing Temperature on the Stability of Parthenolide in Acidified Feverfew Infusions. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruygur, N.; Akça, K.T.; Üstün, O.; Tekin, M. In Vitro Antioxidant and Enzyme Inhibition Activity of Tanacetum argyrophyllum (K. Koch) Tzvelev Var. Argyrophyllum Extract. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 19, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Çelik, S.E. Mechanism of Antioxidant Capacity Assays and the CUPRAC (Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity) Assay. Microchim. Acta 2008, 160, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Saeidi, S. Phytochemical Investigation, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Tanacetum parthenium L. Aerial Parts and Root Ethanolic Extracts at Different Phenological Stages. Iran. J. Med. Aromat. Plants Res. 2023, 39, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudineh, F.; Azari, A.A.; Fozouni, L. Antibacterial Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Matricaria chamomilla, Malva cylvestris, and Capsella bursa-Pastoris against Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strains. Avicenna J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 8, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahani Azari, A.; Danesh, A. Antibacterial Effect of Matricaria chamomilla Alcoholic Extract against Drug-Resistant Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Epidemiol. Microbiol. 2021, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekky, A.E. Study of Phytochemical Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Nigella sativa L. and Matricaria chamomilla L. Al-Azhar J. Agric. Res. 2022, 47, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadilly, A.K.; Alwindy, S. In Vitro Assessment of the Antibacterial Activity of Matricaria Chamomile Alcoholic Extract against Pathogenic Bacterial Strains. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2015, 7, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |