The color of

Capsicum fruits is generally attributed to flavonoids and carotenoids, while their pungency is produced by the accumulation of alkaloids known as capsaicinoids [

1,

6,

23]. Although consumers associate green peppers with no heat, Guzmán et al. [

28] point out that fruit color does not predict pungency. Fruit color depends mainly on variety and ripening stage, ranging from green, yellow, or white in unripe fruit to red, dark red, brown, and almost black in ripe fruit [

24].

6.1. Capsaicinoids

The spicy flavor and pungency of chili peppers are due to a group of biomolecules called capsaicinoids, which have an alkaloid structure and are produced exclusively in

Capsicum spp. [

29,

30]. The level of pungency can vary greatly depending on many factors, such as environment, soil fertility, temperature, weather, seasonal variation, seed lineage, and water availability. Pungency is expressed in Scoville Heat Units (SHUs), which is a subjective scale based on the ratio and content of capsaicinoids [

14,

31]. The Scoville units of measurement express the number of times a chili extract has to be diluted into H

2O to lose its pungency [

32]. According to Weiss, there are five general levels of pungency using SHUs (SHUs): non-pungent (0–700 SHUs), mildly pungent (700–3000 SHUs), moderately pungent (3000–25,000 SHUs), highly pungent (25,000–80,000 SHUs), and very highly pungent (>80,000 SHUs), as classified by Weiss [

33].

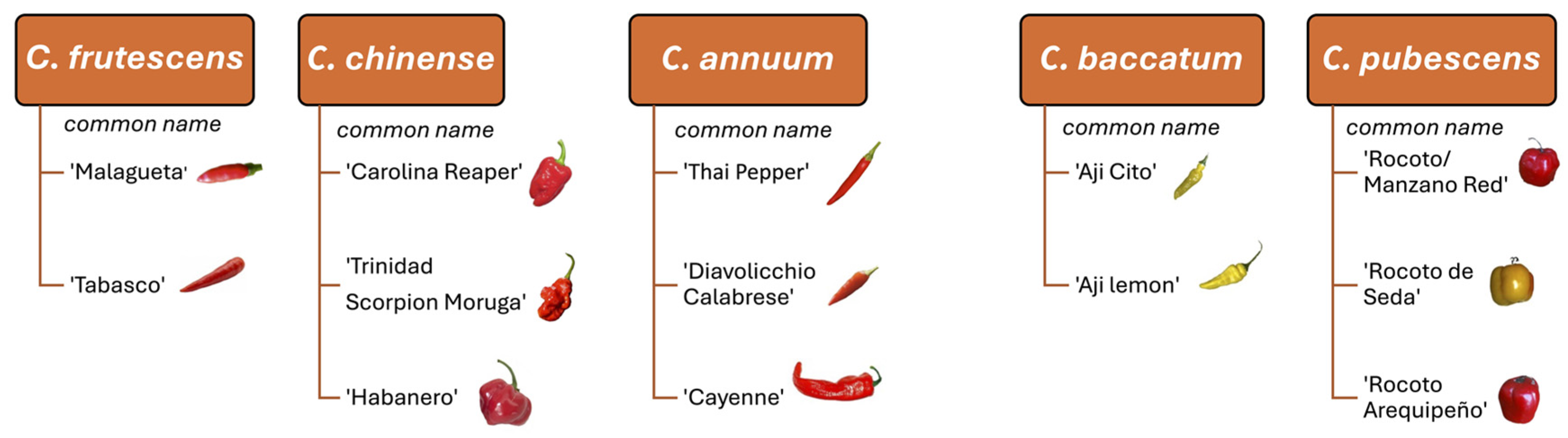

The pungency, measured in SHUs, of the five domesticated species of

Capsicum spp. is as follows:

C. chinense is above 1,000,000 SHUs,

C. frutescens is up to 150,000 SHUs,

C. annuum is up to 100,000 SHUs,

C. pubescens is up to 50,000 SHUs, and

C. baccatum is up to 30,000 SHUs, as described by Duranova et al. [

3].

The Carolina Reaper (

C. chinense) is considered the hottest chili pepper in the world, with an average pungency of 2,200,000 SHUs. When cultivated in the Yucatan region of Mexico, this pepper rates a pungency of 3,006,330 SHUs, which is the greatest value ever recorded [

34].

Among the Italian varieties of

C. annuum, the “Sigaretta” is generally considered the spiciest Italian chili pepper, with a heat rating of 85,000 SHUs. Other typical varieties range in spiciness from 5000 SHUs for the Naso di Cane and Bacio di Satana varieties to 50,000 SHUs for the Diavolicchio Calabrese cultivar [

8,

9].

The synthesis of capsaicinoids predominantly occurs within the placenta of the fruit, where vanillylamine, the precursor, is present in the highest concentration [

6,

35,

36]. These compounds are produced and accumulated in this tissue before diffusing to other compartments within the fruit and other plant organs. Over 85% of capsaicinoids are found in the placenta, reaching concentrations 10 times higher than in other organs during ripening [

35,

37]. The second most effective organ at accumulating capsaicinoids is the seed, which absorbs them from the neighboring placental tissue [

38]. Following the concentration of capsaicinoids, there is a natural decline over time as a result of the plant’s natural metabolic processes [

37,

39].

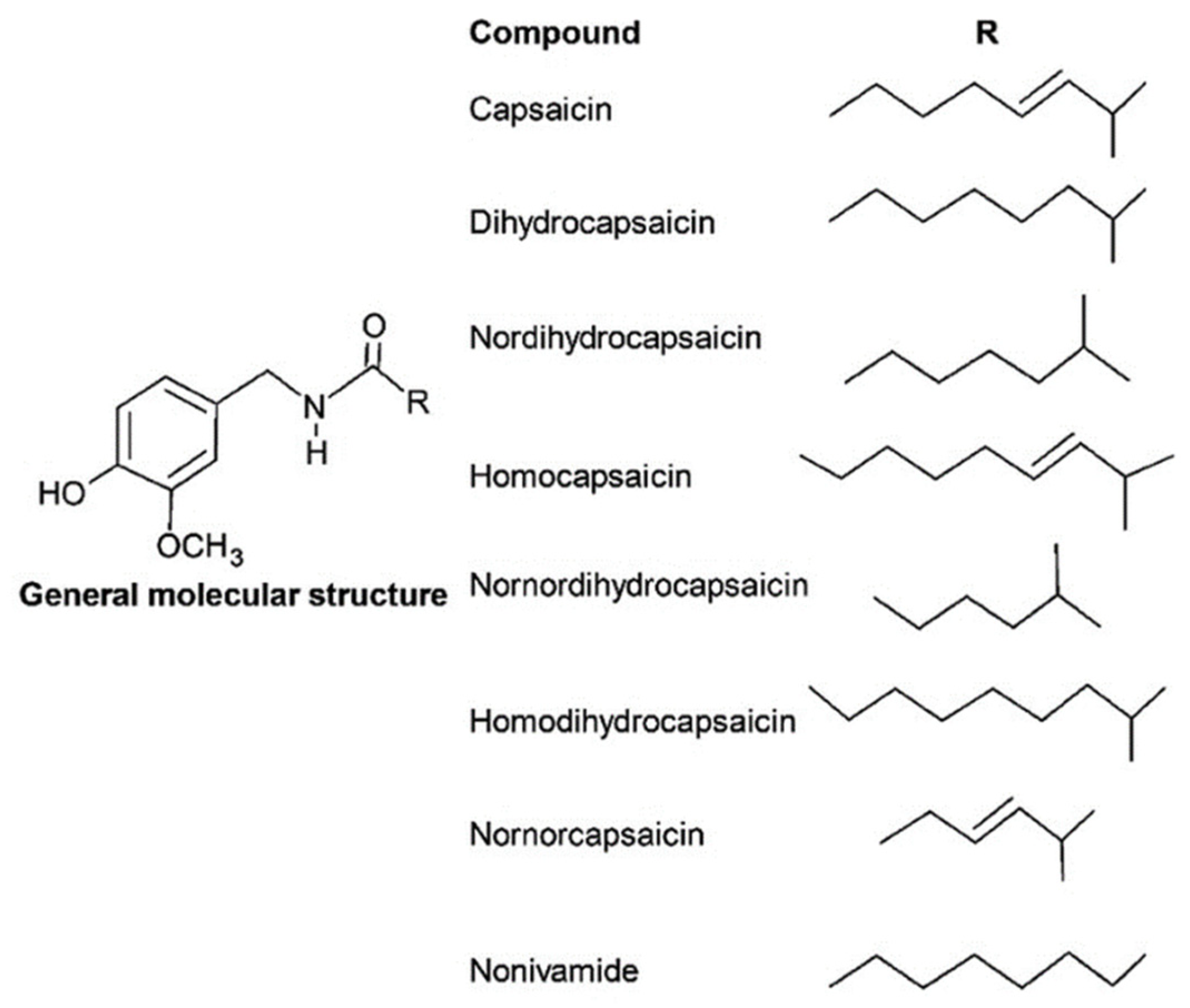

The general chemical structure of capsaicinoids is constituted of a vanillyl group bonded with an amide and an alkyl chain, as depicted in

Figure 5 [

37]. Bioactivity is mainly attributed to the vanillyl group present in the structure [

40,

41].

As shown in

Figure 5, the molecular diversity of capsaicinoids is due to the carbon chain, which may be unsaturated and branched (e.g., capsaicin, homocapsaicin, and nornocapsaicin), saturated and branched (e.g., dihydrocapsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, nornordihydrocapsaicin, and homodihydrocapsaicin), or saturated and linear (e.g., nonivamide). All capsaicinoids identified in the five domesticated

Capsicum spp. are listed in

Table 3.

The major capsaicinoids in

Capsicum spp. are capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin, which account for 89–98% of the total content in fresh fruits and are primarily responsible for about 70% of pungency [

1,

3,

6,

23,

45].

Nonivamide, nornordihydrocapsaicin, homodihydrocapsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, and nornorcapsaicin have been described as the main minor capsaicinoids because of their relatively low abundance [

49,

63,

65]. Nordihydrocapsaicin represents about 7% of the total capsaicinoid content, while homocapsaicin and homodihydrocapsaicin account for about 1%, both having approximately half the pungency of capsaicin. Further, nonivamide (less than 3% of the total content) is a minor capsaicinoid found in chili peppers with a pungency level similar to that of capsaicin. The concentration of these minor capsaicinoids can be used as an indicator of potential adulteration [

6,

37].

Researchers have detected a wide range of variation in the amount of capsaicinoids both within and between species, as shown in

Table 3. Taiti et al. [

43] made a comparison of the content of capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, and homodihydrocapsaicin in 21 different varieties belonging to three different

Capsicum species. The varieties belonging to

C. chinense have shown the greatest level of capsaicinoids (e.g., capsaicin 1089.3–13,630.1 mg/kg; dihydrocapsaicin 201.6–9907.3 mg/kg; nordihydrocapsaicin 14.5–1688.1 mg/kg; and homodihydrocapsaicin 17.9–824.0 mg/kg) compared to

C. baccatum, and

C. annum. This outcome is also confirmed by the results obtained in the study that Sora et al. performed [

47], which analyzed the capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin contents in the pulps and seeds of

C. annum (capsaicin 7.72–61.95 mg/100 g; dihydrocapsaicin 10.02–102.70 mg/100 g),

C. baccatum (capsaicin 2.29–10.01 mg/100 g; dihydrocapsaicin 7.58–39.47 mg/100 g),

C. chinense (capsaicin 21.70–1024.32 mg/100 g; dihydrocapsaicin 14.15–1207.84 mg/100 g), and

C. frutescens (capsaicin 48.27–203.84 mg/100 g; dihydrocapsaicin 68.32–410.30 mg/100 g). However, the capsaicinoid profiles do not exhibit homogeneous behavior in cultivars collected in different locations. Even when they are subject to the same conditions, a wide range of concentrations can be observed for each capsaicinoid [

54].

Overall, the content of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin is one of the main factors that determines the commercial quality of chili peppers [

43,

47,

52]. Depending on their intended use, breeders and consumers may require a lower or higher level of pungency and concentration of capsaicinoids. For medicinal purposes, cultivars with low to moderate capsaicinoid content are preferable in order to formulate safe medicines for human consumption [

6,

41]. In the food industry and for military use, however, products containing a high content of capsaicinoids are desirable, so cultivars with a moderate to high content of capsaicinoids are usually used [

6,

66,

67].

C. chinense cultivars are renowned for their spiciness and typically contain higher levels of capsaicin than other species. This feature makes them more challenging to use as medicine than other species, such as

C. annuum, which is commonly used as a spice or even as a chemical weapon [

6,

68]. However, alternative to capsaicinoids are the capsinoids, with promising advantages over capsaicinoids in clinical applications such as cancer prevention [

69]. The main difference between the two classes is that capsinoids are less pungent than capsaicinoids [

52,

70]. Their molecular structure differs from that of capsaicinoids due to the presence of an ester functional group formed when the vanillyl group connects to the carbon chain. Capsinoids (capsiate, dihydrocapsiate, and nordihydrocapsiate) are synthesized almost exclusively in non-pungent cultivars of the

Capsicum genus [

52,

69,

70].

6.2. Carotenoids

The different colors of

Capsicum fruits are mainly associated with the profile of some pigments (chlorophylls, anthocyanins, and carotenoids), which are all localized in the plastids of the mesocarp (the middle layer of the fruit wall). The green color of chilies is due to chlorophyll, while anthocyanins are responsible for the violet/purple pigments, and carotenoids provide the yellow-orange and red colors [

3,

71].

Carotenoids are the most abundant and important pigments in chili peppers due to their involvement in photosynthesis, in photo-oxidative processes (from extra UV light that is not useful for photosynthesis), and in photo-morphogenesis [

71]. Moreover, they act as precursors of the growth regulator abscisic acid and attract pollinators and seed dispersal agents [

71].

All carotenoids in the

Capsicum species usually contain nine conjugated double bonds, and 95% of these pigments accumulate within chromoplasts, in fibrils, crystals, tubule structures, or in lipophilic globules [

3,

71].

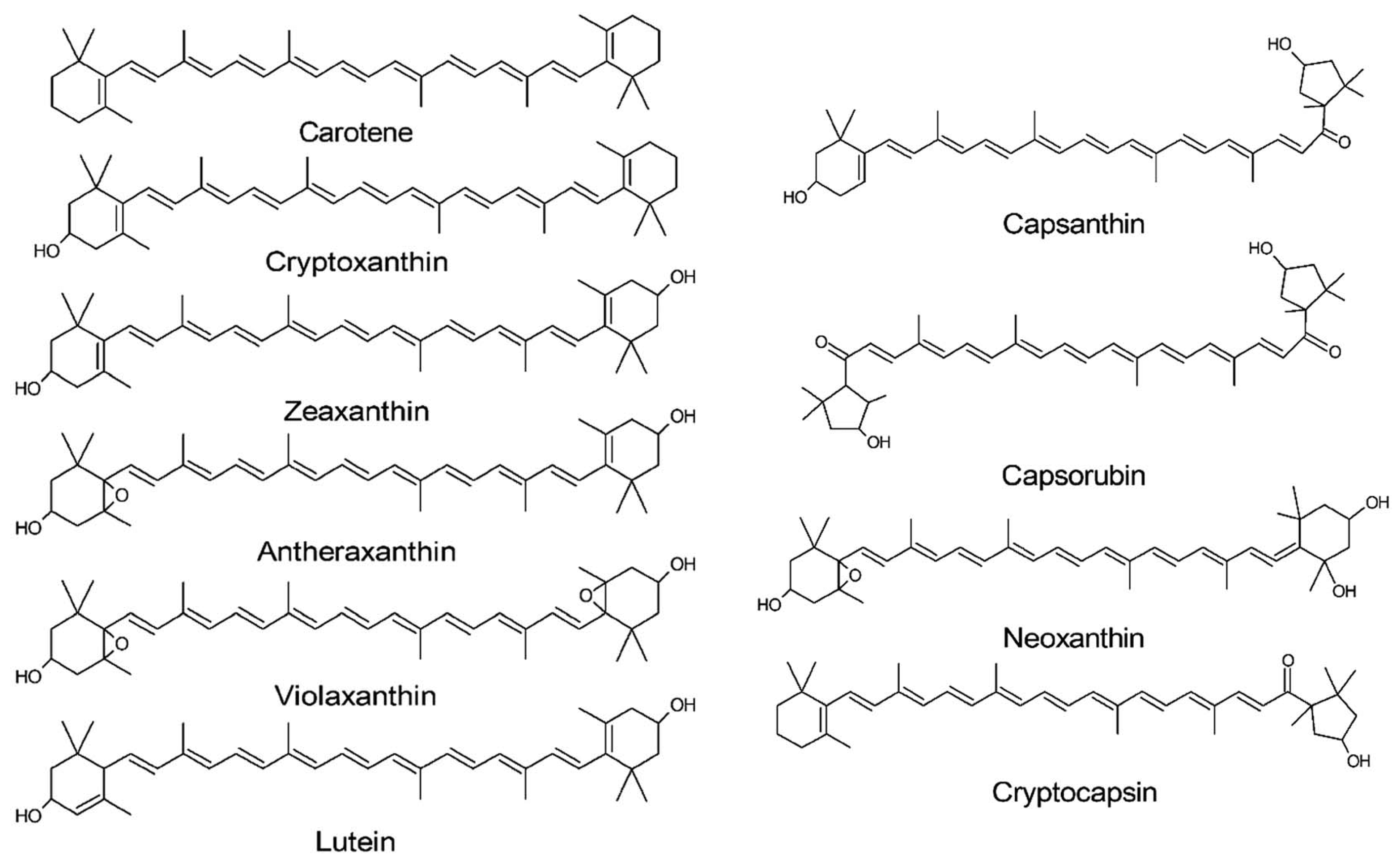

Carotenoids normally have a 40-carbon isoprene structural backbone, with alternating double bonds and the aromatic ring structures at one or both ends of the molecule. According to their chemical structure, carotenoids can be classified into two main groups: carotenes and xanthophylls. Carotenes are linear or cyclized hydrocarbons, such as α-carotene and β-carotene, while xanthophylls include carotenoids with oxygenated functions (hydroxy, keto, methoxy, epoxy, and carbonyl groups) such as lutein, antheraxanthin, violaxanthin, cryptoxanthin, and zeaxanthin [

4,

6,

50,

71].

Considering the classification based on the chromogenic properties, carotenoids are divided into yellow-orange and red fractions. The yellow-orange fraction is composed of carotenoids with different degrees of oxidation: α-carotene, β-carotene, cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, antheraxanthin, and violaxanthin [

4,

6,

23,

50,

71]. The red fraction differs from the yellow one due to the 3-hydroxy β rings being substituted with a 3-hydroxyacylcyclopentane ring. Examples of this fraction are capsanthin, capsorubin, neoxanthin, and cryptocapsin [

71,

72]. In this group, the keto-carotenoids (capsanthin and capsorubin) are found only in the

Capsicum genus [

4,

6,

23,

71].

Red carotenoids are esterified by short-chain fatty acids such as lauric (C12:0), myristic (C14:0), and palmitic acid (C16:0). The yellow ones are esterified with myristic (C14:0), palmitic (C16:0), and linoleic acid (C18:2, Δ9–12). The number of double bonds in the fatty acid chains of yellow carotenoids makes them less stable than their red counterparts [

6,

71]. However, about 20% of the total carotenoids remains in their free form [

6].

The main carotenoids present in

Capsicum genus are reported in

Figure 6 [

4,

6,

50,

71].

The carotenoid profiles in chili pepper fruits are different among

Capsicum species, depending closely on several aspects such as growing conditions, part of the plant, stage of maturity, and post-harvest management practice [

3,

4,

6,

23,

73].

In pepper fruit, more than 30 different carotenoids have been identified, and in

Table 4, the main carotenoids of the five domesticated species belonging to the genus

Capsicum are reported.

Generally, considering all five

Capsicum spp., yellow-fruited cultivars presented violaxanthin and lutein as the main carotenoids (

Table 4). Moreover, in species in which violaxanthin is the major carotenoid, it comprises approximately 30–50% of the total content, while when lutein is the most abundant, it can cover 41–67% [

6,

71]. Yellow/orange varieties are characterized by violaxanthin, lutein, and antheraxanthin, and the absence of red fraction compounds. On the other hand, the red-fruited cultivars presented capsanthin as the major carotenoid, constituting anywhere from 35 to 70% of the total carotenoid, with low levels of the yellow fraction carotenoids reported [

6,

71,

72,

78,

84].

In particular, Li et al. [

42] studied 75 cultivars belonging to four

Capsicum species. In this study, the capsanthin, zeaxanthin, and β-carotene contents in

C. annum (67 varieties),

C. baccatum (one variety),

C. chinense (four varieties), and

C. frutescens (three varieties) were compared.

C. annuum had the highest capsanthin content (170.92 µg/g), but this red carotenoid was not detected in all of them. Zeaxanthin was present in all varieties, with

C. annuum displaying the greatest amount (118.91 µg/g).

C. annuum also showed the maximum concentration of β-carotene (11,158.94 µg/g). Overall, no significant differences were reported in capsanthin and β-carotene among the

Capsicum spp. (

p > 0.05). However, the zeaxanthin content of

C. annuum was significantly higher than that of

C. chinense and

C. frutescens, which did not differ significantly from each other (

p > 0.05) [

42].

Giuffrida et al. [

50] also confirmed this considerable variation in carotenoid composition observed among the various cultivars. They investigated

C. annum (three varieties),

C. chinense (eight varieties), and

C. frutescens (one variety) and identified 52 different carotenoids. The red color cultivars of

C. annum and

C. chinense showed high β-carotene content (10.8% and 4.5–19.1%, respectively), whereas some variety of

C. annum and

C. frutescens were characterized by high capsanthin content (3.3–7.9% and 12.6%, respectively) with no of β-carotene present. Some

C. chinense varieties reported a high lutein amount (48.3%, 17.3%, and 15.6%), and cryptocapsin was only present in one

C. chinense cultivar (1.5%). Moreover, a

C. chinense variety was found to be rich in zeaxanthin (10.8%), antheraxanthin (9.9%), lutein (4.8%), and capsanthin (4.5%).

6.3. Flavonoids

Like carotenoids, flavonoids are known for their chromogenic properties and are responsible for the vivid colors observed in fruits and plants by the human eye [

85,

86]. Plants have been found to accumulate flavonoids, which have several functions. These include protection against UV rays, regulation of growth, the production of antimicrobial agents, and attraction to pollinators [

87,

88,

89,

90].

Flavonoids are low-molecular-weight secondary metabolites that share a common skeleton with diphenylpropanes (C6-C3-C6) and contain two phenyl rings (A and B), which are joined by a heterocyclic C ring of pyran [

3,

6,

23,

85,

87,

88,

89,

90]. They are mainly grouped into seven subclasses based on modifications to their basic skeleton: flavones, flavanols, flavanones, flavonols, isoflavones, and anthocyanins [

87,

88,

89,

90,

91].

In chili pepper peels, flavonoids are mainly accumulated in the form of conjugated O-glycosides and C-glycosides derivates [

3,

6,

23] and in

Figure 7 are shown to be the main flavonoids detected in

Capsicum spp.

According to Nascimento et al. [

62], a botanical scale of chili based on the concentration of flavonoids was proposed, classifying them as low (0.1–39.9 mg/kg), moderate (40–99.9 mg/kg), and high (>100 mg/kg). They also underline the quantitative variation in flavonoids in chili peppers depending on the extraction solvent and the plant part analyzed. The study also reported that chili peppers, when compared to high-concentration plants such as wild mint and grapes, contain a moderate level of flavonoids [

92].

Variations in flavonoid concentrations are primarily the result of the diversity in genotypes, landraces, and varieties, as well as in the ripening phase [

59,

81,

86,

93]. Further, differences related to analytical laboratory parameters such as sample preparation, extraction, and quantification methods also play a role [

3,

6]. Generally, higher levels of flavonoids have been observed in pungent peppers than in sweet ones, in green peppers than in red or orange ones, and in immature peppers than in mature ones [

51,

94,

95]. Furthermore, the content of flavonoids exhibits a contrasting pattern compared to capsinoid and carotenoid contents. It has been reported that, as ripening progresses, flavonoid content decreases by up to 85% compared to its levels during the vegetative stages [

51,

95].

Table 5 lists the flavonoid compounds present in the five domesticated

Capsicum spp., and under each flavonoid aglycone, all the related conjugated derivates are clustered (i.e., O-glycosides and C-glycosides compounds).

Quercetin, luteolin, and apigenin were present in major quantities in

C. annum,

C. baccatum,

C. chinense, and

C. frutescens (

Table 5). Generally, these flavonoids are in their hydrolyzed form and account for more than 40% of the total flavonoid content [

1,

3,

6,

23]. In terms of their chemical structure, quercetin glycosides are only found in the O-glycosylated form and are the most abundant forms (i.e., quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside and quercetin-7-O-rhamnoside). Apigenin glycosides are identified as both C- and O-glycosides, while luteolin is exclusively present in its C-glycosylated structure [

1,

6,

85].

In

C. chinense, quercetin levels were reported to be 156.96 µg/g in the immature stage and 10.21 µg/g at maturity [

6]. Similarly,

C. annuum spp. exhibited 3.3 µg/g of quercetin in the immature stage and 2.7 µg/g in the ripe stage [

94]. These findings indicate that quercetin is widely distributed across

Capsicum species, though its concentration decreases markedly during fruit maturation.

Quercetin is the primary flavonoid involved in photoprotection during photosynthesis [

6]. In

C. pubescens, quercetin is the only detectable flavonoid, as reported by Meckelmann et al. [

64], and no additional studies on flavonoids in this species have been published to date (

Table 5). Finally, within the flavonoid group, anthocyanins have been identified in some purple or violet chili varieties, with delphinidin reported as the main compound responsible for their dark pigmentation. Overall, the exclusive detection of quercetin in

C. pubescens suggests a more limited flavonoid profile in this species, highlighting an area where further biochemical characterization is needed. Moreover, the presence of anthocyanins in specific pigmented varieties underscores the role of flavonoids not only in photoprotection but also in determining fruit coloration, offering potential applications in breeding programs aimed at enhancing nutritional or ornamental traits.

6.4. Volatile Compounds

Capsicum spp. is among the most widely consumed spices worldwide, valued for its distinctive flavor and aroma. The perception of its complex volatile profile plays a key role in consumer acceptance and food selection [

104]. Understanding this volatile composition is essential for distinguishing between species and varieties, ensuring authenticity, supporting quality control, preventing fraud, and verifying geographical origin. Moreover, the food industry increasingly seeks concentrated pepper aromas to flavor products without necessarily adding pungency [

104,

105].

The volatile fraction is responsible for chili pepper aromas with over 200 substances principally grouped in the following chemical classes: alkanes, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters terpenes, hydrocarbons, pyrazine, and sulphur compounds [

6,

43,

53,

57,

61,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108].

A wide variety of esters and terpenes were detected in chili peppers, consistent with previous reports [

43,

54,

57,

61,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110]. Methyl and ethyl esters contribute intense fruity aromas, while terpenes add woody, floral, fruity, and spicy notes [

57,

104,

105,

108]. Aldehydes, though generally low odor, are key to the green, pungent, and herbaceous nuances typical of

Capsicum [

57,

108]. In contrast, alcohol has a higher odor threshold and therefore plays a more limited role in overall aroma. Short-chain ketones, particularly methyl ketones, provide strong aromatic notes, whereas alkanes—aliphatic, aromatic, and branched—are associated with capsaicin biosynthesis and carotenoid degradation, as reported by Pino et al. [

107]. Red-fruited varieties tend to contain higher alkane levels, while orange-fruited types are richer in esters. Across

Capsicum species, ripening typically reduces aldehyde content, yielding a more pleasant aroma in fully matured fruits. At the same time, ester formation depends on alcohol availability, which declines during ripening [

104,

108].

The aroma composition of

Capsicum spp. is a complex mixture of volatile compounds that differ greatly both within and between species [

6,

43]. Kollsmannsberger et al. [

57] found that

C. chinense and

C. baccatum had a high concentration and variety of esters, but

C. pubescens had very few of these. There was also a divergence in terpenoid concentration between

C. chinense and

C. baccatum, with lower concentrations in the latter. Regarding terpenoids,

C. chinense and

C. pubescens differed in the major terpenoids (cubenene and ylangene); see

Table 6.

Himachalene was mainly detected in

C. chinense and also appeared as a distinctive component of the more pungent cultivars of

C. frutescens and

C. annuum, as previously reported [

53,

108]. Similarly, bicyclogermacrene and its derivatives—bicycloelemene and α-gurjunene—were present only in

C. chinense and

C. pubescens but absent in

C. baccatum,

C. annuum, and

C. frutescens. In contrast, germacrene A derivatives such as β-elemene, iso-β-elemene, and 7-epi-α-selinene are typically found in certain

C. annuum varieties [

53,

108] and in

C. pubescens yet were not detected in

C. chinense [

57]. Moreover,

C. pubescens was characterized by notably high levels of the Z and E isomers of muurola-4(14),5-diene, and cyperene was found exclusively in this species.

Among the volatile compounds, the alkyl-methoxy-pyrazines are distinctive for the

Capsicum spp. and are not very common in other plants. These pyrazines are usually associated with a very distinct scent and contribute to creating the typical green and spicy aroma of chili peppers [

107,

110]. In particular, the principal pyrazine in oleoresin and paprika is tetramethyl-pyrazine [

111]; 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine is involved in

C. annuum ripening [

110]; and 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine in the mature fruits of

C. chinense [

107], as reported in

Table 6.

Taken together, these patterns suggest that specific sesquiterpenes and their derivatives can serve as useful chemotaxonomic markers within the Capsicum genus. For example, the presence of himachalene and bicyclogermacrene derivatives helps distinguish C. chinense, while the occurrence of cyperene and abundant muurola isomers uniquely identifies C. pubescens. Conversely, germacrene A derivatives may be indicative of certain C. annuum varieties. These differences likely reflect species-specific biosynthetic pathways and may contribute to the characteristic aroma profiles and pungency levels associated with each species.