Abstract

Organophosphate pesticides are among the most persistent and toxic contaminants in aquatic environments, requiring effective strategies for detection and remediation. In this work, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to investigate the adsorption of nine representative organophosphates (glyphosate, malathion, diazinon, azinphos-methyl, fenitrothion, parathion-methyl, disulfoton, tokuthion, and ethoprophos) on mercaptobenzothiazole disulfide (MBTS) and MBTS-functionalized graphene (G–MBTS). All simulations were performed in aqueous solution using the SMD solvation model with dispersion corrections and counterpoise correction for basis set superposition error. MBTS alone displayed a range of affinities, suggesting potential selectivity across the organophosphates, with adsorption energies ranging from 0.27 to 1.05 eV, malathion being the strongest binder and glyphosate the weakest. Anchoring of MBTS to graphene was found to be highly favorable (1.26 eV), but the key advantage is producing stable adsorption platforms that promote planar orientations and –/dispersive interactions. But the key advantage is not stronger binding but the tuning of interfacial electronic properties: all G–MBTS–OP complexes show uniform, narrow HOMO-LUMO gaps (∼0.79 eV) and systematically larger charge redistribution. These features are expected to enhance electrochemical readout even when adsorption strength was comparable or slightly lower (0.47–0.88 eV) relative to MBTS alone. A Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) analysis of the G–MBTS–malathion complex revealed a dual stabilization mechanism: multiple weak C–H⋯ interactions with graphene combined with stronger S⋯O and hydrogen-bonding interactions with MBTS. These results advance the molecular-level understanding of pesticide–surface interactions and highlight MBTS-functionalized graphene as a promising platform for the selective detection of organophosphates in water.

1. Introduction

Organophosphate (OP) insecticides are some of the most commonly used chemicals for agriculture. Farmers have relied on them for decades because of their effectiveness and versatility against a wide variety of pests [1]. At the same time, it is well known that OPs are often applied in amounts greater than recommended, which has contributed to a number of environmental and health issues [2]. These compounds break down slowly; they can persist in soil, sediment, and water for long periods of time [1]. Over time, residues may enter water supplies and food chains. This means that even if concentrations are low, people can still be exposed on a chronic basis [2]. Such exposures have been associated with neurotoxicity through acetylcholinesterase inhibition, as well as disruptions of the endocrine and immune systems [3]. For these reasons, there is an urgent need to develop technologies that can both monitor and remove OPs with a high degree of selectivity [4].

Classical chromatographic techniques are still considered the standard for measuring OP levels. They are highly accurate and specific, which makes them extremely valuable in a laboratory setting [5]. However, they also come with practical limitations: expensive instrumentation, complicated operation, and sample preparation that can be both tedious and time-consuming. In addition, these methods are not portable and require skilled personnel. As such, they are not suited for quick field analysis or real-time monitoring [6]. Such shortcomings have motivated the search for alternative approaches. Particularly, the use of advanced functional materials that can combine detection and remediation in a single platform [7].

Recent reviews emphasize the rapid progress of enzyme-free, nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors for organophosphate detection, underscoring the need for stable, low-cost, and selective materials capable of reversible charge-transfer sensing under ambient conditions [8,9].

Carbon-based materials, graphene and its derivatives in particular, have shown potential for this type of application in the past. Graphene has a large surface area, high conductivity, and a surface chemistry that can be tuned to interact with different molecules [10]. Its oxide and reduced oxide have been widely studied for the adsorption of OP pesticides [11,12,13]. Their aromatic surfaces allow – stacking with organic molecules, which increases their affinity for aromatic OPs [14]. In addition, nanoscale GO has been shown to improve both adsorption rates and capacities for compounds such as malathion and diazinon. The presence of oxygenated functional groups also plays a role in molecular recognition and binding strength [15].

Mercaptobenzothiazole disulfide (MBTS) is another compound of environmental concern. It is an organosulfur molecule that persists in the environment and is capable of engaging in different noncovalent interactions: hydrogen bonding, chalcogen bonding, and – stacking among them. It has previously been used to modify carbon paste electrodes for the detection of water pollutants [16]. The performance of this sensor was significantly improved due to the introduction of MBTS on its surface. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations from that study highlighted the importance of adsorption energy and charge transfer when governing the sensitivity and selectivity of the electrode [17,18,19,20,21].

Building on this, the present work explores the use of MBTS as a modifier for graphene nanoflakes to tune its surface chemistry, trying to enhance the molecular recognition of a set of OP. This set spans from polar/non-aromatic (glyphosate) to aromatic thiophosphates (e.g., azinphos-methyl, fenitrothion), sampling different interactions: dispersion/– for aromatics, hydrogen/chalcogen bonding for P=O/P=S moieties, and weaker contacts for highly polar species.

2. Computational Details

All quantum chemical calculations were carried out using the ORCA 4.1.2 package [22,23]. Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed at the PBE/def2-SVP [24,25] level of theory within the framework of density functional theory (DFT). Dispersion interactions were treated using Grimme’s D3 correction with Becke–Johnson damping (D3BJ) [26]. Solvent effects were modeled implicitly using the SMD solvation model, with water as the solvent [27]. To correct for basis set superposition error (BSSE) in adsorption energy calculations, the counterpoise correction method was applied [28].

The adsorption energy () of the organophosphate molecules on the modified carbon surface was computed according to the following expression:

where is the total energy of the adsorbate–adsorbent system, and are the energies of the isolated surface and pollutant molecule, respectively, and is the counterpoise correction for basis set superposition error. are presented in eV and larger values indicate a stronger interaction.

Atomic charges calculations through CM5 [29], along with topological analysis of the electron density were performed using the Multiwfn 3.8 program [30] to locate and characterize bond critical points (BCPs) [31] and to evaluate relevant quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) parameters [32]. Molecular structures were visualized and rendered using VMD [33] and Chemcraft.

3. Results and Discussion

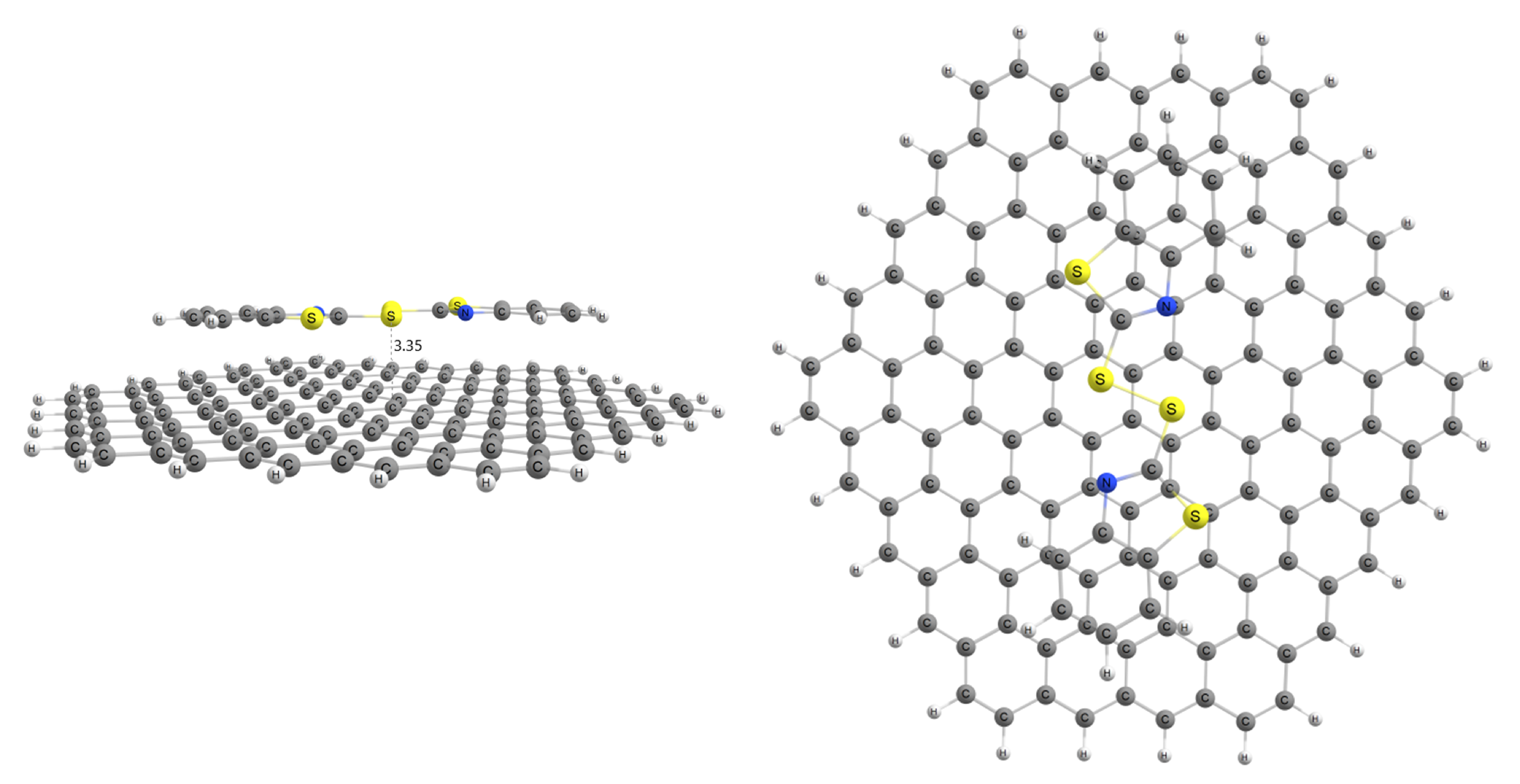

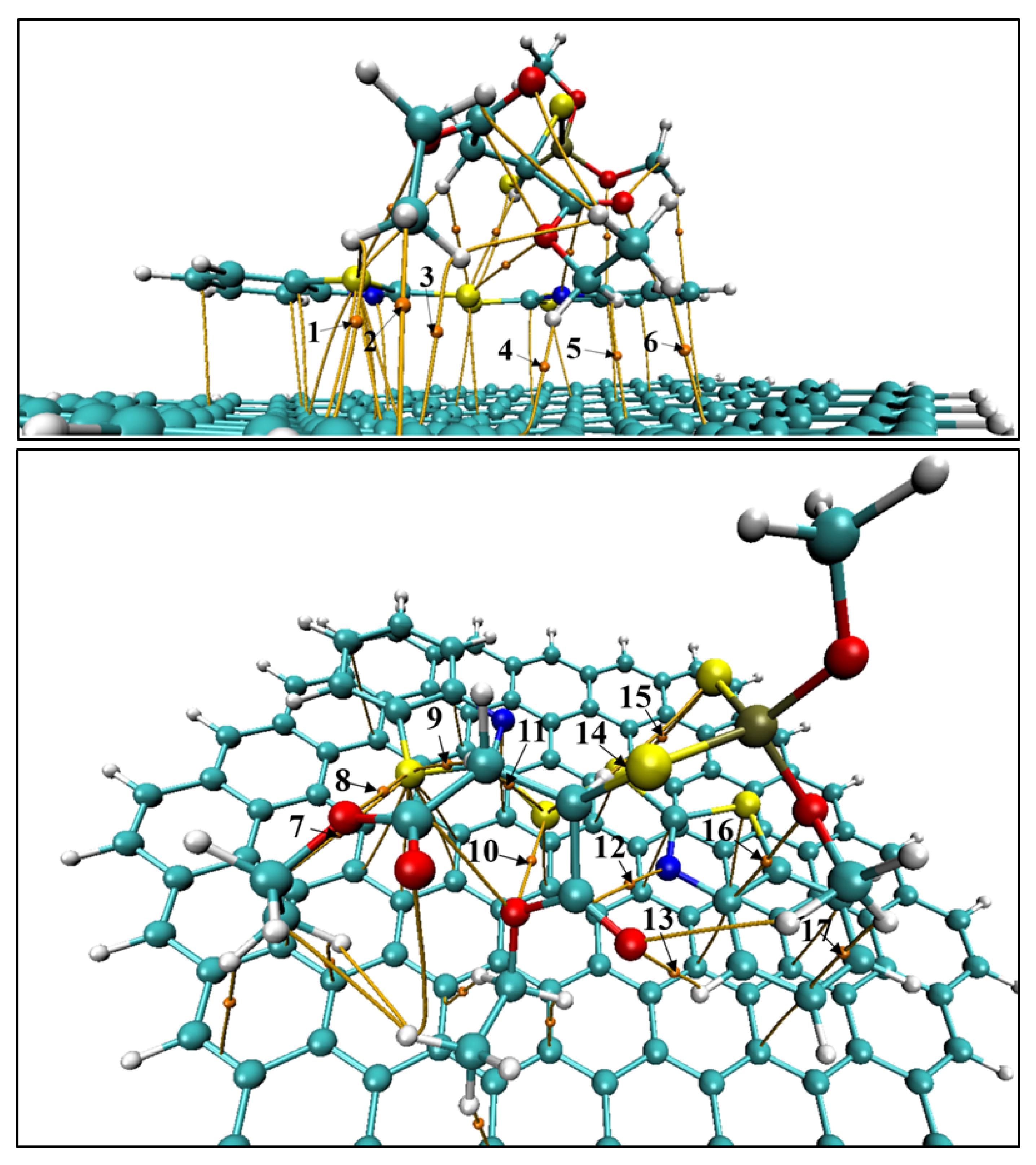

The adsorption of MBTS over a graphene nanosheet was modeled to determine its viability as an adsorbent for this work, and the resulting structure is presented in Figure 1. Optimized coordinates can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1.

MBTS adsorbed on graphene nanoflake.

MBTS-modified graphene has an adsorption energy of 1.26 eV, indicative of a stable adsorption process. This, along with the distance of 3.35 Å between MBTS and the carbon layer, is in accordance with previously published studies. Before modeling this modified system as an adsorbent, it is important to establish if and how our selected organophosphates interact with MBTS by itself.

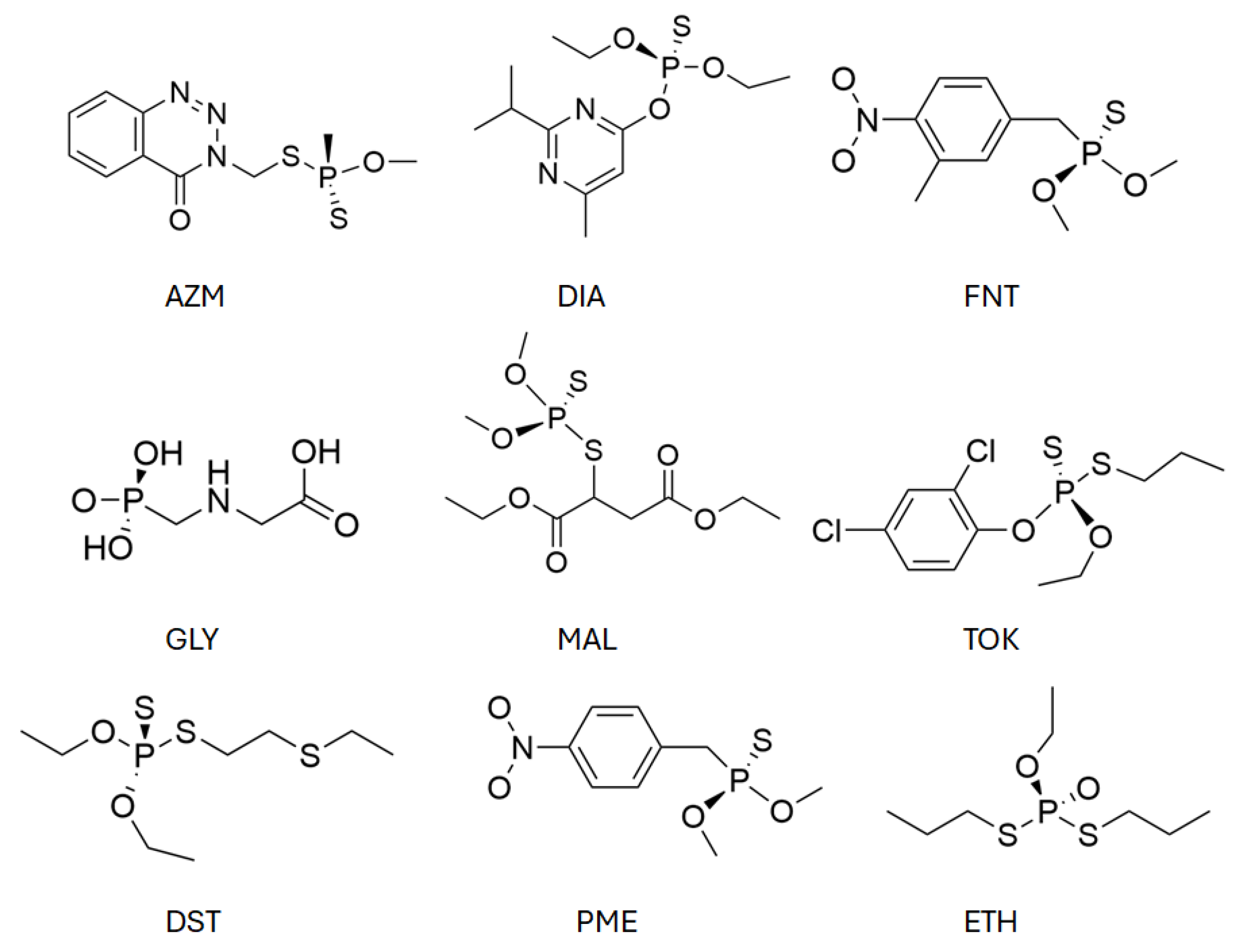

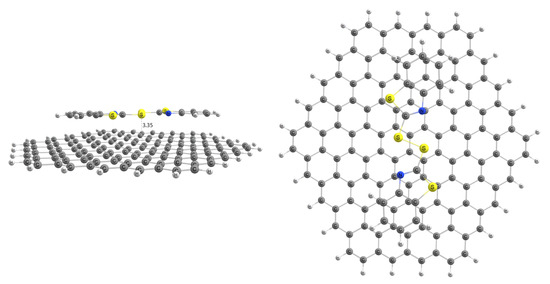

The selected organophosphate (OP) pollutants comprise glyphosate (GLY), malathion (MAL), diazinon (DIA), azinphos-methyl (AZM), fenitrothion (FNT), tokuthion (TOK), disulfoton (DST), parathion-methyl (PME), and ethoprophos (ETH), whose chemical structures are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the organophosphates under study. Abbreviations: GLY = glyphosate, MAL = malathion, DIA = diazinon, AZM = azinphos-methyl, FNT = fenitrothion, TOK = tokuthion, DST = disulfoton, PME = parathion-methyl, ETH = ethoprophos.

These compounds were chosen due to their high agricultural relevance, frequent detection in contaminated water sources, and the diversity of their functional groups, which enables different adsorption modes. Glyphosate is a highly polar phosphonic acid herbicide, while the remaining compounds are insecticides containing thiophosphate or phosphate ester moieties, often accompanied by aromatic rings or aliphatic substituents. Such structural features allow for a range of noncovalent interactions with the adsorbent, including – stacking, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. This chemical diversity provides a comprehensive basis for assessing the interaction capability and potential selectivity of the MBTS-modified graphene surface across pollutants of varying polarity, size, and steric demand.

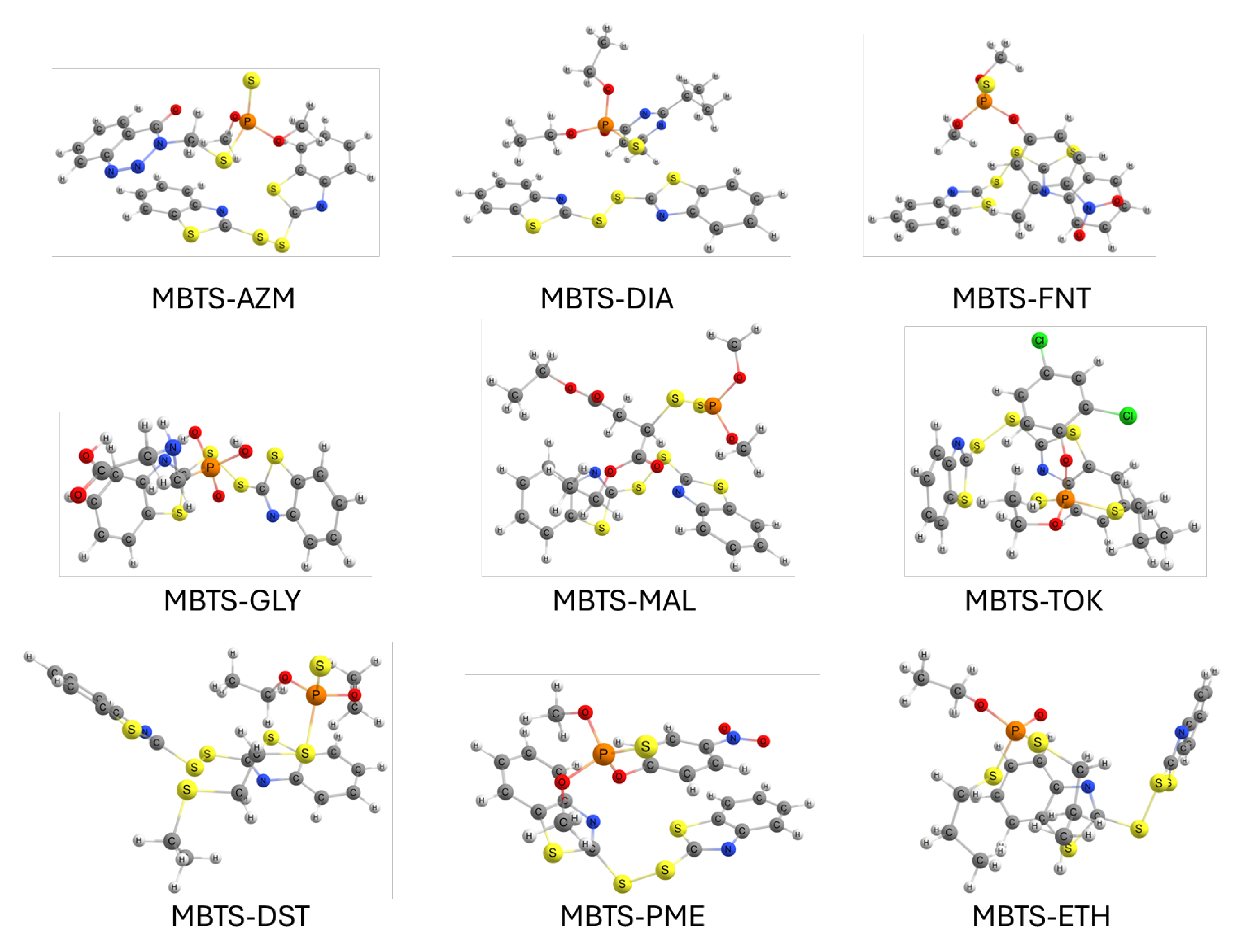

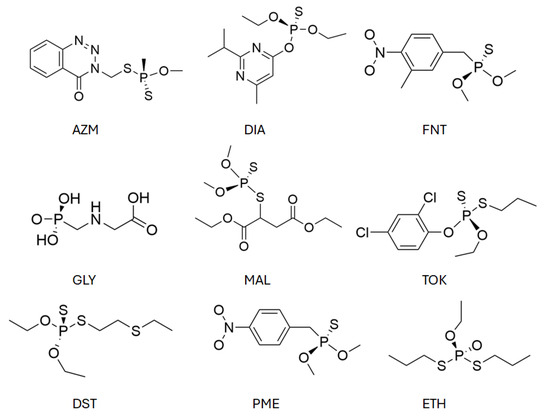

For each MBTS–OP system, several initial configurations were constructed by varying the relative orientation and position of the organophosphate molecule with respect to the MBTS fragment. Geometry optimizations were performed for all starting arrangements, and the results reported herein correspond to the most stable conformations, i.e., those with the lowest total energy obtained after full optimization. Figure 3 shows the resulting structures. Optimized coordinates can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 3.

Optimized geometries for adsorption complexes between OPs and MBTS.

In all cases, the molecules adopt orientations that maximize non-covalent interactions such as – stacking between the benzothiazole ring and aromatic moieties of the organophosphate, hydrogen bonding involving phosphoryl oxygen or alkoxy groups, and short S⋯O/P contacts suggestive of chalcogen bonding. The flexibility of the MBTS disulfide bridge allows for conformational adjustments that enhance surface contact, while some organophosphates exhibit noticeable distortions in their alkyl or aromatic substituents to optimize binding. Variations in binding modes, from head-on approaches centered on the phosphoryl group to lateral alignments maximizing dispersion, are expected to influence the adsorption strength and electronic interactions. Table 1 summarizes the adsorption energies, HOMO–LUMO gaps, and charge transfer between MBTS and each organophosphate.

Table 1.

Adsorption energies between MBTS and the selected organophosphates, along with FMO gaps and charge distribution of the resulting adsorption complexes. Charge transfer recipient have negative values.

The adsorption energies reveal notable differences in interaction strength between MBTS and the studied organophosphates. The MBTS–MAL complex exhibits the highest adsorption energy (1.0520 eV), indicating the strongest interaction, likely due to the combined effect of multiple contact points between the malathion phosphoryl group, alkoxy substituents, and MBTS’s aromatic/disulfide moieties. Intermediate adsorption energies are observed for MBTS–AZM, MBTS–FNT, MBTS–TOK, MBTS–DST, MBTS–PME, and MBTS–ETH (0.6192–0.7329 eV), suggesting that these molecules adopt geometries that balance – interactions with hydrogen bonding or chalcogen bonding. The lowest adsorption energies correspond to MBTS–DIA (0.4106 eV) and MBTS–GLY (0.2710 eV), the latter likely reflecting glyphosate’s smaller hydrophobic contact area and lack of aromatic groups. The HOMO–LUMO gap values range from 2.2492 eV (MBTS–DIA) to 2.8314 eV (MBTS–ETH), with modest variations suggesting that adsorption does not drastically alter the electronic structure of the MBTS framework but may subtly tune its reactivity. Charge distribution analysis shows that most complexes exhibit electron transfer from MBTS to the organophosphate (0.0399–0.1217 e−), consistent with electron density donation through the benzothiazole and disulfide groups. Notably, MBTS–DST and MBTS–ETH show reverse charge transfer ( e− and e−, respectively), which could be attributed to the stronger electron-withdrawing nature of their substituents. These electronic and energetic trends align with the binding motifs observed in Figure 3 and suggest that both molecular size and functional group composition critically influence adsorption performance.

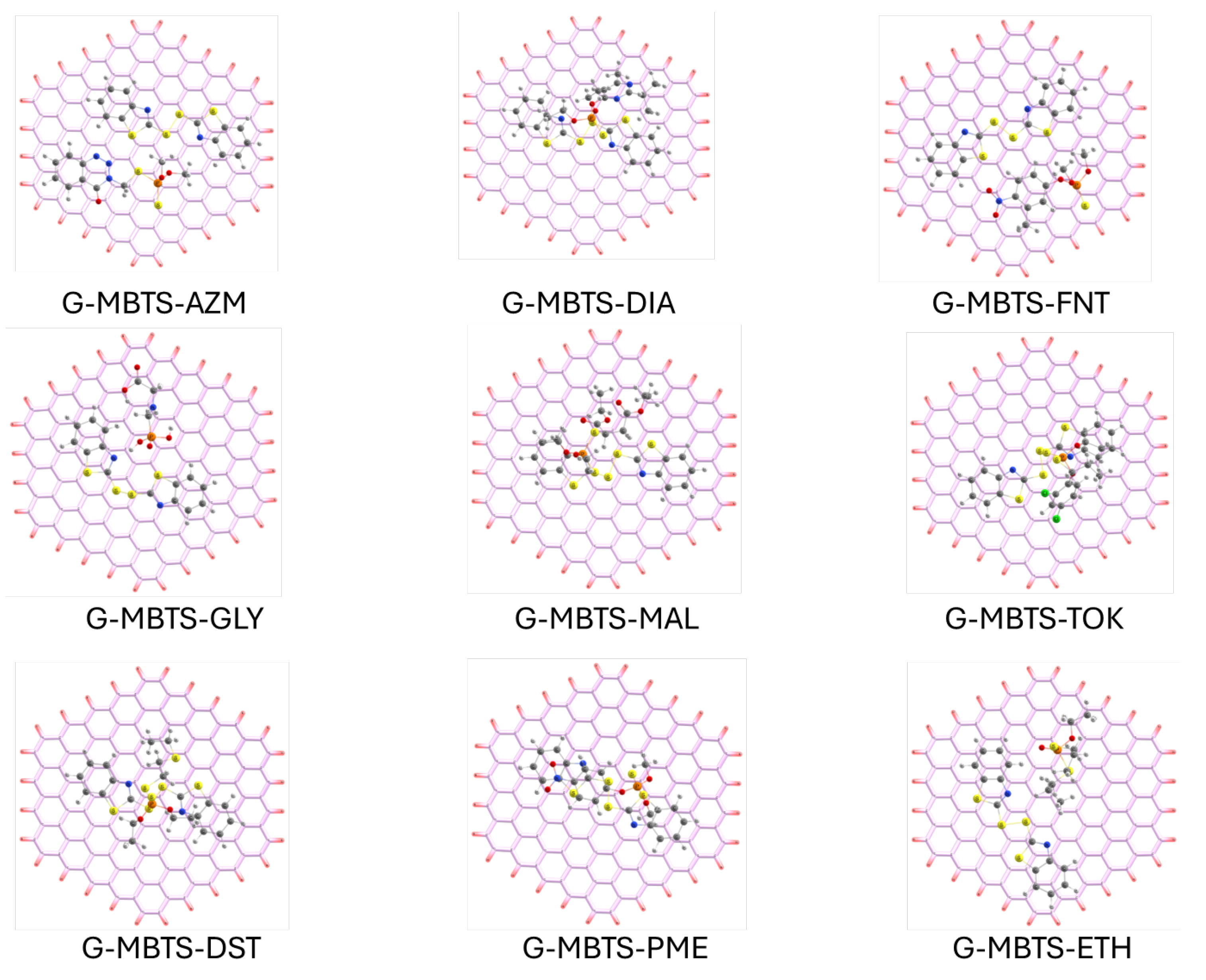

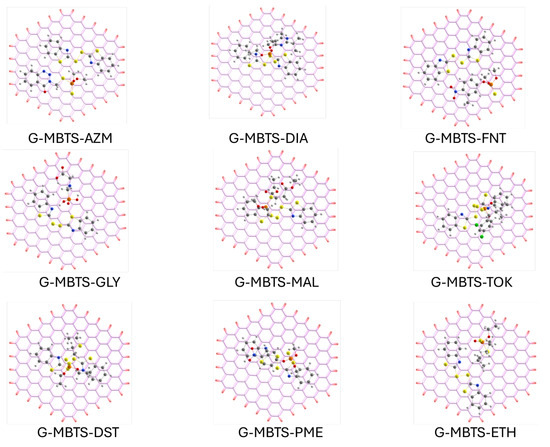

After analyzing the adsorption complexes of MBTS with the organophosphates, it is evident that the interaction strength and electronic effects are strongly dependent on the size, functionalization, and aromaticity of each pesticide. To further probe the role of the graphene substrate, we extended the analysis to MBTS anchored on graphene (G–MBTS) and its corresponding adsorption complexes with the same set of organophosphates. Several initial orientations relative to the surface were tested. The reported values correspond to the lowest-energy pose found after optimization. Optimized coordinates can be found in the Supplementary Material.

The optimized geometries (Figure 4) reveal that the graphene surface enforces more planar adsorption motifs, with both MBTS and the organophosphates adopting orientations that maximize – stacking and van der Waals contacts with the extended aromatic lattice. For aromatic organophosphates such as azinphos-methyl, fenitrothion, and parathion-methyl, the molecules align nearly parallel to the graphene sheet, favoring large-area dispersive interactions. In contrast, non-aromatic or highly polar species like glyphosate adsorb in a more tilted configuration, minimizing overlap with the graphene -system and explaining their much weaker stabilization. The MBTS moiety itself remains strongly anchored to graphene, as indicated by its large adsorption energy (1.2665 eV), and mediates additional non-covalent interactions with the pollutants via its disulfide and benzothiazole groups. This adsorption energy, and the rest of the energetic values for the set of complexes, is listed in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Adsorption complexes between the organophosphates and MBTS-modified graphene. P: orange, S: yellow, O: red, N: blue, C: white and H: white.

Table 2.

Adsorption energies, FMO energy gaps and charge distribution for complexes under study. Charge transfer recipient have negative values.

The adsorption energies of the G–MBTS–OP systems (0.4674–0.8796 eV) are generally comparable to or slightly lower than those observed for MBTS–OP in isolation, reflecting the geometric constraints imposed by the graphene support. However, the charge transfer is systematically enhanced, with G–MBTS–MAL showing the largest redistribution ( e−) despite a slightly reduced adsorption energy relative to MBTS–MAL alone (0.8796 vs. 1.0520 eV). This highlights that the graphene substrate does not necessarily amplify adsorption strength, but it plays a decisive role in modulating electronic properties, particularly by narrowing the HOMO–LUMO gap to approximately 0.79 eV across all systems. Such electronic tuning suggests that G–MBTS could serve as a more effective sensing material than MBTS alone, since conductivity and charge redistribution are crucial for detection applications. Notably, glyphosate remains an outlier, with a nearly negligible adsorption energy (0.0616 eV) and substantial charge redistribution ( e−), underscoring its poor compatibility with the hydrophobic graphene environment. In future works, explicit solvent and ion-pair models, or oxygenated defect sites on graphene, could further stabilize polar analytes without compromising the electronic sensitivity of the surface. The consistent narrowing of the HOMO–LUMO gap to about 0.79 eV in all G–MBTS–OP complexes is a key electronic signature of the hybrid surface. This small and uniform gap implies that once MBTS is anchored, graphene behaves as a narrow-gap, charge-responsive material whose conductivity is highly sensitive to minor charge perturbations. Such electronic tuning favors mesurable impedance or voltammetric responses even for weakly bound analytes. G–MBTS–GLY small adsorption energy and large charge transfer further supports this interpretation: reversible, charge transfer driven interactions, rather than very strong adsorptions, are expected to dominate the sensing response of MBTS–functionalized graphene. Similar charge transfer-based sensing responses have been reported experimentally for other graphene hybrid electrodes, demonstrating how modifiers can amplify interfacial charge sensitivity [34].

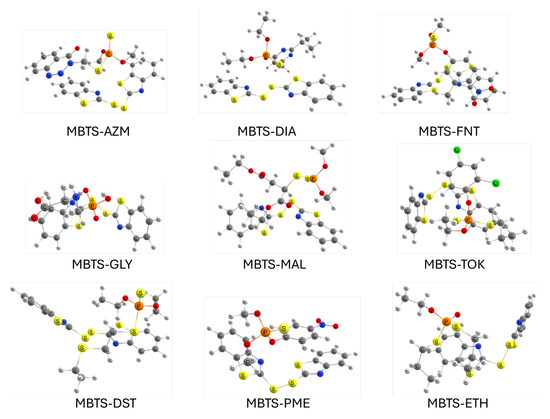

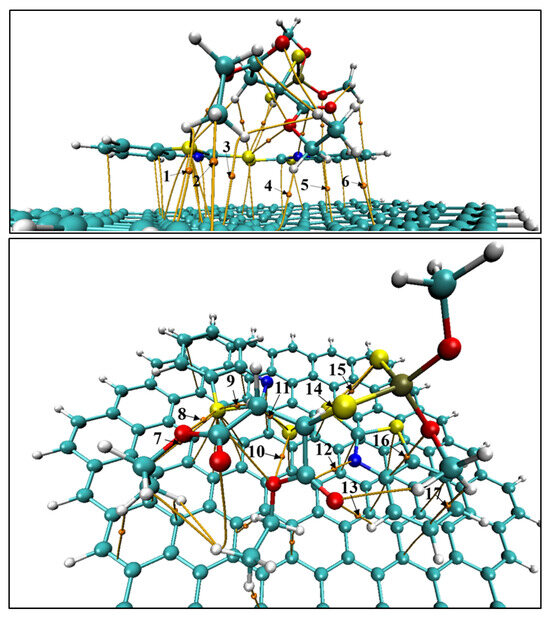

Given that the G–MBTS–MAL complex exhibited the largest charge transfer and one of the strongest adsorption energies among the studied systems, this case was selected for a more detailed characterization of the intermolecular interactions. In particular, a topological analysis of the electron density within the framework of the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) was carried out, focusing exclusively on the bond critical points (BCPs) located between malathion and the MBTS modifier, as well as between malathion and the graphene surface. This allows us to identify and quantify the specific contacts responsible for stabilization, complementing the energetic and electronic descriptors discussed above.

Here we focus on QTAIM inspection on BCPs linking malathion with MBTS and with graphene in the G–MBTS–MAL adduct (Figure 5), to determine which contacts underpin the adsorption and the large charge redistribution reported above. Parameters for each BCP are listed on Table 3.

Figure 5.

BCPs involved in the G-MBTS-MAL adsorption complex. (Top) BCPs between graphene and malathion. (Bottom) BCPs between malathion and MBTS. C: cyan, H: white, O: red, S: yellow, N: blue, P: olive.

Table 3.

QTAIM parameters for the bond critical points (BCPs) in the G–MBTS–MAL adsorption complex.

The index, which is a covalency descriptor, remains close to zero across all BCPs. This confirms that these interactions are of closed-shell nature and dominated by electrostatic or dispersion forces. For the malathion–graphene interface (BCPs 1–6) the bond paths are all C⋯H type, i.e., C–H⋯ contacts to the graphene sheet. Their electron densities are small (– a.u.) with positive Laplacians (– a.u.) and small positive energy densities (– a.u.), diagnosing weak, closed-shell interactions dominated by dispersion/electrostatics. The high ellipticities, especially for BCP 4 (; also the largest among C⋯H contacts), reveal anisotropic accumulation. This is characteristic of interactions with an extended -surface. Collectively these six BCPs form a dispersed anchoring “mat,” consistent with the orientation of malathion over graphene.

At the malathion–MBTS interface (BCPs 7–17) the picture becomes more directional and somewhat stronger. The largest density is the S⋯O chalcogen bond (BCP 10, ; a.u.), followed by several S⋯H hydrogen bonds (BCPs 9, 11, 14; –) and an O⋯H hydrogen bond (BCP 13, ). All display and , again indicating closed-shell, non-covalent character, but with larger than the graphene contacts. Additional contacts include N⋯C (BCP 12), S…S (BCP 15; , suggestive of anisotropic chalcogen–chalcogen interaction), and C⋯O/C⋯H (BCPs 16–17), which round out a multi-point recognition network between malathion and the MBTS disulfide/benzothiazole fragment.

Quantitatively, the MBTS–malathion set shows a higher average (≈0.00685 a.u.) and larger cumulative (≈0.043 a.u.) than the graphene–malathion contacts (average a.u.; cumulative a.u.), indicating that MBTS provides the dominant local stabilization, while graphene contributes a distributed CH… platform that helps position malathion and increases the contact area. This topology rationalizes the trends discussed for G–MBTS–MAL in the previous table: despite a slightly smaller adsorption energy than MBTS–MAL in isolation, the larger number of parallel contacts to graphene plus the directional S⋯O/S⋯H/O⋯H interactions to MBTS create efficient electronic coupling pathways, which is consistent with the largest charge transfer observed for G–MBTS–MAL. In short, MBTS supplies the strong, directional chalcogen- and H-bonding “hooks,” while graphene supplies the -scaffold that broadens the interaction footprint—together yielding the distinctive energetic–electronic signature of the G–MBTS–MAL adduct.

4. Thermodynamic Considerations

The adsorption energies reported here correspond to 0 K electronic values that include dispersion and BSSE corrections within the implicit water model. At finite temperature, vibrational and configurational entropy contributions will reduce the magnitud of these values, so the actual adsorption free energies in aqueous phase are expected to be less exergonic. From a sensing standpoint, however, this moderation is advantageous: electrochemical impedance and voltammetric responses occur in milisecond to second timescales, and reversible adsorption ensures rapid exchange of analytes while maintaining strong charge transfer coupling. Therefore, MBTS-functionalized graphene is better interpreted as a charge transfer sensor rather than a permanent adsorbent, consistent with the uniform narrow gap and large interfacial charge redistribution observed for the G–MBTS–OP systems.

5. Conclusions

The results indicate that MBTS interacts selectively with different organophosphates, with malathion showing the strongest binding ( eV) and glyphosate the weakest ( eV). Anchoring of MBTS on graphene is energetically favorable ( eV) and induces planar adsorption geometries that promote dispersive and – interactions.

The adsorption of organophosphates on G–MBTS results in energies comparable to, or slightly lower than, those observed for MBTS alone (0.47–0.88 eV), but consistently leads to larger charge transfers and reduced HOMO–LUMO gaps (∼0.79 eV). QTAIM analysis of the G–MBTS–malathion complex shows that stabilization arises from a combination of multiple weak C–H⋯ interactions with graphene and stronger, directional S⋯O and hydrogen-bonding interactions with MBTS.

Overall, these results indicate that MBTS-functionalized graphene acts as an electronically sensitive and reversible platform for organophosphate detection. The uniform narrowing of the HOMO–LUMO gap to about 0.79 eV and the enhanced charge redistribution upon adsorption suggest that its sensing performance originates from charge-transfer modulation rather than strong chemisorption. Therefore, the system should be considered a charge-transfer sensor rather than a permanent adsorbent. Further sensing engineering could be guided by following the computed FMOs and charge redistribution. Experimental validation through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, cyclic voltammetry, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy would provide direct evidence of the predicted interfacial charge transfer. Notably, previous experimental studies have demonstrated that even weakly adsorbed analytes can yield strong electrochemical responses through interfacial charge-transfer modulation rather than permanent binding [35,36,37]. Future work incorporating explicit solvent and defect models will refine the adsorption thermodynamics and help bridge the gap between theoretical predictions and measurable sensing responses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/compounds5040043/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P.-U. and U.G.R.-L.; methodology, K.P.-U., G.K.J. and U.G.R.-L.; software, Z.G.-S.; formal analysis, G.K.J. and J.M.F.-Á.; investigation, K.P.-U., G.K.J., J.P.M.-S. and A.A.-V.; resources, Z.G.-S., J.P.M.-S. and U.G.R.-L.; data curation, J.P.M.-S. and A.A.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K.J.; writing—review and editing, K.P.-U. and J.M.F.-Á.; visualization, J.P.M.-S. and A.A.-V.; supervision, Z.G.-S.; funding acquisition, K.P.-U. and J.M.F.-Á. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Universidad de Colima under the internal program “Fortalecimiento a la Investigación 2023”. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the Faraday UTEM Cluster (FONDEQUIP EQM180180) for computational resources.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ulises Guadalupe Reyes-Leaño was employed by the company Agrobiocol Green. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mali, H.; Shah, C.; Raghunandan, B.; Prajapati, A.S.; Patel, D.H.; Trivedi, U.; Subramanian, R. Organophosphate pesticides an emerging environmental contaminant: Pollution, toxicity, bioremediation progress, and remaining challenges. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 127, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ore, O.T.; Adeola, A.O.; Bayode, A.A.; Adedipe, D.T.; Nomngongo, P.N. Organophosphate pesticide residues in environmental and biological matrices: Occurrence, distribution and potential remedial approaches. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2023, 5, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Nian, B.; Yu, C.; Maimaiti, D.; Chai, M.; Yang, X.; Zang, X.; Xu, D. Mechanisms of neurotoxicity of organophosphate pesticides and their relation to neurological disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024, 20, 2237–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, W.; Pei, H.; Hu, N.; Li, Z.; Suo, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, J. The simultaneous detection and removal of organophosphorus pesticides by a novel Zr-MOF based smart adsorbent. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Gholami, A.; Akhgari, M. A novel method for the determination of organophosphorus pesticides in urine samples using a combined gas diffusion microextraction (GDME) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) technique. Methodsx 2025, 14, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, A.; Vashishth, R.; Singh, S.; James, A.; Chellam, P.V. Biosensors for detection of organophosphate pesticides: Current technologies and future directives. Microchem. J. 2022, 178, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejigu, A.; Tefera, M.; Guadie, A.; Abate, S.G.; Kassa, A. A Review of Voltammetric Techniques for Sensitive Detection of Organophosphate Pesticides in Environmental Samples. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 29929–29949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Hasnat, M.A. Recent advancements in non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor development for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides in food and environment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathiraja, G.; Bonner, C.D.J.; Obare, S.O. Recent Advances of Enzyme-Free Electrochemical Sensors for Flexible Electronics in the Detection of Organophosphorus Compounds: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Urbina, K.; Jayaprakash, G.K.; Flores-Moreno, R.; Reyes-Leaño, U.G.; Gómez-Sandoval, Z.; Flores-Álvarez, J.M.; González-Ramírez, H.N.; Rikhari, B. Exploring the adsorption behavior of N-octyl pyridinium ionic liquids on graphene: Insights into reactivity and stability. J. Ion. Liq. 2025, 5, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, G.; Roy, N.; Mukherjee, A. Recent Developments in the Applications of GO/rGO-Based Biosensing Platforms for Pesticide Detection. Biosensors 2023, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.; Singh, M.B.; Tomar, N.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Dabodhia, K.L.; Singh, P. Adsorption of pesticides using graphene oxide through computational and experimental approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1291, 136043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Yu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, Z.; Yang, Q. Determination of organophosphorus pesticides based on graphene oxide aerogel solid phase extraction column. Se Pu (Chin. J. Chromatogr.) 2022, 40, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, G.K.; Swamy, B.K.; Rajendrachari, S.; Sharma, S.; Flores-Moreno, R. Dual descriptor analysis of cetylpyridinium modified carbon paste electrodes for ascorbic acid sensing applications. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334, 116348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadawattana, P.; Kawashima, K.; Sittiwanichai, S.; T-Thienprasert, J.; Mori, T.; Pongprayoon, P. Exploring the Capabilities of Nanosized Graphene Oxide as a Pesticide Nanosorbent: Simulation Studies. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 8951–8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Álvarez, J.; Cortés-Arriagada, D.; Gómez-Sandoval, Z.; Jayaprakash, G.K.; Ceballos-Magaña, S.G.; Muñiz-Valencia, R.; Rojas-Montes, J.; Pineda-Urbina, K. Selective detection of Cu2+ ions using a mercaptobenzothiazole disulphide modified carbon paste electrode and bismuth as adjuvant: A theoretical and electrochemical study. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 15052–15063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghravanian, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Es’haghi, Z.; Beyramabadi, S.A. Experimental sensing and density functional theory study of an ionic liquid mediated carbon nanotube modified carbon-paste electrode for electrochemical detection of metronidazole. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2017, 70, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudur Jayaprakash, G.; Kumara Swamy, B.E.; Nicole Gonzalez Ramirez, H.; Tumbre Ekanthappa, M.; Flores-Moreno, R. Quantum chemical and electrochemical studies of lysine modified carbon paste electrode surface for sensing dopamine. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 4501–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, G.K.; Swamy, B.E.K.; Chandrashekar, B.N.; Flores-Moreno, R. Theoretical and cyclic voltammetric studies on electrocatalysis of benzethonium chloride at carbon paste electrode for detection of dopamine in presence of ascorbic acid. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 240, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, G.K.; Swamy, B.E.K.; Casillas, N.; Flores-Moreno, R. Analytical Fukui and cyclic voltammetric studies on ferrocene modified carbon electrodes and effect of Triton X-100 by immobilization method. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 258, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudur Jayaprakash, G.; Swamy, B.E.K.; Flores-Moreno, R.; Pineda-Urbina, K. Theoretical and Cyclic Voltammetric Analysis of Asparagine and Glutamine Electrocatalytic Activities for Dopamine Sensing Applications. Catalysts 2023, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System, Version 4.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paier, J.; Hirschl, R.; Marsman, M.; Kresse, G. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional applied to the G2-1 test set using a plane-wave basis set. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 234102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1396–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boys, S.; Bernardi, F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Jerome, S.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Charge Model 5: An Extension of Hirshfeld Population Analysis for the Accurate Description of Molecular Interactions in Gaseous and Condensed Phases. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Matta, C.F. On the connections between the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) and density functional theory (DFT): A letter from Richard FW Bader to Lou Massa. Struct. Chem. 2017, 28, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Khalid, W.; Atif, M.; Ali, Z. Graphene oxide–cerium oxide nanocomposite modified gold electrode for ultrasensitive detection of chlorpyrifos pesticide. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 27862–27872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.Z.; Ge, W.; Carey, B.; Daeneke, T.; Rotbart, A.; Shan, W.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Z.; Chrimes, A.F.; Wlodarski, W.; et al. Physisorption-Based Charge Transfer in Two-Dimensional SnS2 for Selective and Reversible NO2 Gas Sensing. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10313–10323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Talib, M.; Novikov, S.M.; Arsenin, A.V.; Volkov, V.S.; Mishra, P. Physisorption-Mediated Charge Transfer in TiS2 Nanodiscs: A Room Temperature Sensor for Highly Sensitive and Reversible Carbon Dioxide Detection. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 3264–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powroźnik, P.; Krzywiecki, M. Intertwining Density Functional Theory and Experiments in the Investigation of Gas Sensing Mechanisms: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).