Abstract

Atomic-scale strain is the basis of a material’s macroscopic deformation behavior. The current measure of atomic-scale strain in the form of the Green–Lagrange tensor loses its physical meaning beyond the yield point, as atomic neighborhoods undergo significant reconstructions. We have recently introduced a new atomic-scale strain measure, namely, atomic bond strain, through our study of bond behavior in multicomponent metallic glasses. Here, we apply this new strain measure to uniaxial tensile tests (simulated using molecular dynamics) of several representative single-crystal FCC (face-centered cubic) metals under varied strain rates. We show that this new strain measure displays remarkable near-linear correlation with stress, not only in the elastic regime, but also in the plastic regime where complex dislocation dynamics (nucleation, bursting, motion, annihilation, regeneration) and stress fluctuations take place. This suggests that the overall stress of the materials even in the plastic regime is predominantly determined by the degree of bond stretching among all atoms. This appears to contradict the common conceptions that the plastic flow stress of a crystalline material is governed by dislocation events involving only a small fraction of atoms around dislocations, and that the stress–strain relationship is highly non-linear for plastic deformation. The contradictions can be reconciled by considering the causal sequence: dislocation events alter bond stretching, and bond stretching directly determines the stress. This brings a novel insight into the nature of plastic deformation, owing to the newly introduced atomic bond strain. How well the near-linear correlation between the stress and the atomic bond strain holds in other materials (e.g., non-FCC single crystals, polycrystals, quasicrystals, elements, alloys, and compounds) is an intriguing and important topic for future investigation, following the example of this work.

1. Introduction

Materials’ macroscopic mechanical behavior is fundamentally a statistical manifestation of the atomic-scale response to external load [1,2,3]. For example, it is well established that the overall stress of a material can be evaluated by averaging the atomic-scale stress (in the form of a virial tensor) of all atoms over the total sample volume [4]. The atomic stress tensor is clearly defined in terms of atomic positions, velocities and mutual forces for a given atomic configuration (state) [4].

By analogy with the atomic stress tensor, it is currently a common practice to evaluate atomic-scale strain for each atom in the form of the Green–Lagrange (G–L) tensor, based on the local neighborhood deformation of each atom relative to a reference configuration (state) [5,6,7]. For each atom i, a set of neighboring atoms within a cutoff radius (often chosen to be the first nearest-neighbor distance) is identified, and the local deformation gradient tensor is computed as the best-fit linear transformation that maps the reference positions of neighbors j to their current positions . This is achieved by minimizing the quantity:

Once the local deformation gradient is obtained, the G–L strain tensor is calculated as:

This widely used measure of atomic strain provides a tensorial, atom-resolved measure of local deformation, and naturally accounts for large elastic strains and rotations. It is particularly useful for visualizing heterogeneous strain distributions near dislocations, grain boundaries, or interfaces. However, the G–L atomic strain has a well-known limitation: once the neighborhood (i.e., neighbor identities) of an atom changes due to yielding or significant plasticity, the neighbor correspondence across states and the linear-mapping assumption underlying break down, and the quantitative values in the resulting G–L strain tensor are no longer physically meaningful—although they can still be used qualitatively to highlight more highly strained atoms.

In our recent study of bond behavior in metallic glasses [8,9], we introduced a new measure of atomic-scale strain, namely, atomic bond strain , which is defined as:

where and are the mean length of all existing bonds in the new and reference states, respectively. The averaging of bond lengths can be performed using the full magnitudes of bond vectors, or projected lengths along a particular direction (such as the loading direction in uniaxial testing). By averaging the bond lengths within the respective states, this atomic bond strain eliminates the dilemma of establishing neighbor correspondence across states that the G–L strain evaluation faces upon significant neighborhood reconstructions. In other words, this atomic bond strain remains physically meaningful throughout elastic and plastic deformation. In our recent papers [8,9], we used this new atomic-scale strain measure to highlight the differences among various types of bonds in multicomponent metallic glasses in their response to uniaxial loading and compositional changes. Here, we apply this atomic bond strain concept to examine the uniaxial tensile behavior of single crystals of several representative FCC metals, namely, Pt, Cu and Al.

In crystalline materials, dislocations are widely considered a critical factor governing the apparent strength [1,2,3,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. They are used to explain the much lower yield strength and plastic flow stress observed in experiments than theoretically expected for a perfect crystal. Their dynamic generation, annihilation and motion are also used to explain the variations in the flow stress, including strain hardening, during continuous deformation. Dislocations are line defects with a core radius typically on the order of 1 nm or less, and a local strain field spanning a few nanometers and decaying in inverse proportion to the distance from the dislocation line. The atoms directly associated with dislocations constitute only a small fraction of all atoms in a material, particularly at low dislocation densities. Due to the emphasis on the role of dislocations, the vast majority of atoms forming the structural backbone of a material that are not directly associated with dislocations are typically excluded from discussions of plastic flow stress in crystalline materials.

Meanwhile, it is widely acknowledged that the stress–strain relationship is linear, obeying Hooke’s law, in the elastic regime of most materials, but becomes non-linear past yielding [1,2,3]. Departure from linearity in the stress–strain relationship is in fact regarded as the signature marking the onset of plastic deformation. The non-linearity of the plastic deformation has been widely attributed to dislocation activities.

In this paper, by applying the new atomic bond strain concept to the uniaxial tensile deformation of single-crystal Pt, Cu, and Al, we show that the bond network among all atoms, the vast majority of which are the backbone atoms away from dislocations, plays a strikingly important role in determining the apparent stress even in the plastic deformation regime. The atomic bond strain (projected in the loading direction) based on the mean bond length in the network displays a nearly perfect linear correlation with stress throughout the elastic and plastic deformation of the FCC metals—despite complex dislocation dynamics and constant fluctuations in stress occurring after yielding. This finding is in apparent contradiction with the prevailing conceptions about plastic deformation mentioned above, opening a new perspective on the fundamental nature of plasticity.

2. Methods

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of uniaxial tensile tests were performed on single-crystal Pt, Cu, and Al, three representative FCC metals, using the LAMMPS (Large-Scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator, version 03/03/2020) software [19,20] and quantum-mechanically based EAM (embedded-atom-method) potentials specifically developed for these elements (https://sites.google.com/site/eampotentials/pt, accessed on 1 August 2025). For each metal, a perfect single-crystal square rod was created with 32, 32, and 128 unit cells and S–S–P boundary conditions (S = shrink-wrapped, non-periodic; P = periodic) in the x ([1 0 0]), y ([0 1 0]), and z ([0 0 1]) directions, respectively. Each sample contained 540,800 atoms, which represents a fairly large system for MD simulations.

Each single-crystal rod was first relaxed at 300 K for 50 ps under the NPT ensemble (with controlled number of particles, N, pressure, P, and temperature, T), and then subjected to tensile loading in the z-direction at a constant sample-strain rate of 10−4/ps until fracture, using the Fix Deform command in LAMMPS. For the Al rod, an additional simulation was performed at a sample-strain rate of 2 × 10−5/ps, which is lower than that used in most MD studies. During the tensile loading, the Nosé–Hoover thermostat was used to maintain the sample temperature at ~300 K, and the atomic positions and the zz-component of the per-atom stress tensor, , were periodically output by LAMMPS.

After the tensile simulations, the OVITO (Open Visualization Tool, version 2.9) program [21], together with custom Python (version 3.5.2) scripts, was used to analyze and visualize the atomic configurations, atomic and sample stresses and strains, dislocations, and atomic bonds. More specifically, the sample stress, , was computed by summing the LAMMPS atomic stresses —which represent the product of the atomic stress and atomic volume—over all atoms and dividing by the sample volume, thereby yielding a volume-weighted average corresponding to the macroscopic sample stress. The sample volume was determined using the Construct Surface Mesh modifier in OVITO. Note that the sample volume may differ from the simulation cell volume, especially once non-uniform deformation begins. For this reason, the pressure tensor evaluated by LAMMPS—which is also based on the atomic stress tensor but uses the simulation cell volume—is not used here for .

The G–L atomic strain tensor for each atom was computed directly using the Atomic Strain modifier in OVITO. The relaxed state just before the start of tensile loading was used as the reference, and the cutoff distance for this modifier was set equal to the upper bound of the first nearest-neighbor distance, determined from the valley between the first and second peaks of the radial distribution function (also calculated within OVITO). As will be shown in Section 3, this upper bound of the first nearest-neighbor distance remains unchanged during the entire deformation process, thus permitting the use of a single value of the cutoff distance across all timesteps for a given material and simulation.

For the atomic bond strain analysis, atomic bonds were identified using the same cutoff distance as described above. The absolute values of the z-components of the bond vectors were averaged at each timestep to yield the mean bond z-length. The atomic bond z-strain was then computed from the mean bond z-length data following Equation (3), using the relaxed state just before the start of tensile loading as the reference.

3. Results and Discussion

Since the core results are similar across the different materials and simulations, we focus on the Pt tensile test at a sample-strain rate of 10−4/ps in the main part of this section, with additional data from the other materials and simulations presented at the end.

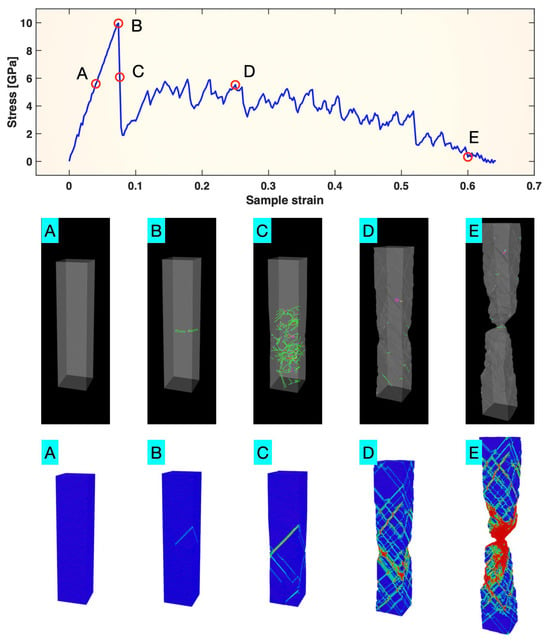

The top panel of Figure 1 presents the plot of stress vs. sample strain from the Pt tensile test. It shows an initial linear elastic regime, a clear yield point (Point B) triggering a sharp stress drop, and then an extended non-linear plastic regime with constantly fluctuating stress as the sample strain increases. This stress vs. sample strain plot is overall consistent with conventional expectations for single-crystalline metals.

Figure 1.

(top) Stress–sample strain curve of single-crystal Pt tensile-tested at a strain rate of 10−4/ps; (middle) dislocations in the sample and (bottom) color map of atomic z-strain () from the G–L atomic strain tensor, in the five states A, B, C, D, and E marked on the stress–sample strain curve. In the (middle) panel, dislocations are color-coded by type. In the bottom panel, blue indicates the minimum strain, and red indicates the maximum.

The middle panel of Figure 1 presents the dislocations identified using OVITO in the Pt sample in the five states (A–E) marked on the stress vs. sample strain plot, representing the pre-yielding, yielding, immediately post-yielding, extended plastic deformation, and near-fracture stages, respectively. In the pre-yielding stage (A), the sample was a perfect single crystal, with no dislocations. At yielding (B), the first dislocations nucleated and began moving across the sample dimensions. In stage C—immediately following yielding—a burst of dislocations, most of which were the 1/6 <112> Shockley partials, was observed. The sudden formation and motion of the relatively large number of dislocations are apparently associated with the sharp drop in the stress displayed in the top panel of Figure 1 around C. As many of these burst dislocations quickly annihilated either through mutual interaction or by disappearing at the sample surfaces, the deformation entered the extended plastic stage (D). In this stage, as well as the near-fracture stage (E), the dislocation density remained relatively low, but dislocations were dynamically (re-)generated, moved and annihilated. The dynamic evolution of dislocations is logically connected with the observed stress fluctuations.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 shows the color map of the zz-component (referred to as the “atomic z-strain” hereafter), , from the G–L atomic strain tensor computed with respect to the relaxed state just before tensile loading. The blue atoms are the least strained, while the green and red atoms represent intermediate and high strain levels, respectively. The more-strained atoms (green and red) essentially delineate the glide planes of both previously annihilated and active dislocations in each state. Note that in the extended plastic deformation regime (states D and E), the number of active dislocations was quite low, as shown in the middle panel of Figure 1. The vast majority of atoms forming the structural backbone of the sample were not directly associated with active dislocations.

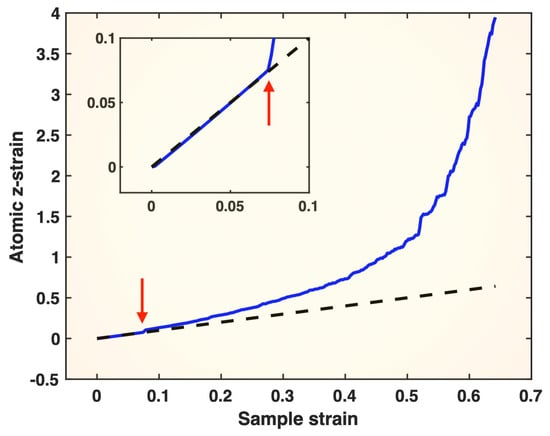

As mentioned in the Introduction, after the sample yields, the G–L atomic z-strain (as well as other components of the G–L tensor) can still qualitatively distinguish highly strained atoms from less strained ones, but its quantitative value becomes physically invalid due to the breakdown of neighbor correspondence and the linear-mapping assumption across configurations/states. In Figure 2, the G–L atomic z-strain averaged over all atoms is plotted against sample strain. Within the elastic regime, the G–L atomic z-strain recovers the sample strain closely, demonstrating its physical validity in this regime. However, after yielding (marked by the red arrows in Figure 2), the G–L atomic z-strain progressively deviates from the sample strain as plastic deformation proceeds, with the deviation accelerating as fracture is approached. Its values in the plastic regime, climbing up to ~4 (400%), are clearly unphysical. Due to the loss of physical validity, the G–L atomic z-strain can neither recover the sample strain nor capture any stress features in the plastic regime observed in the top panel of Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Averaged atomic z-strain (blue solid line) from the G–L strain tensor plotted versus sample strain for the single-crystal Pt tensile-tested at a strain rate of 10−4/ps. The dashed line is the sample strain plotted versus itself, serving as a reference line. The inset is the enlarged low-strain section of the main figure. The red arrows mark the moment of yielding of the sample.

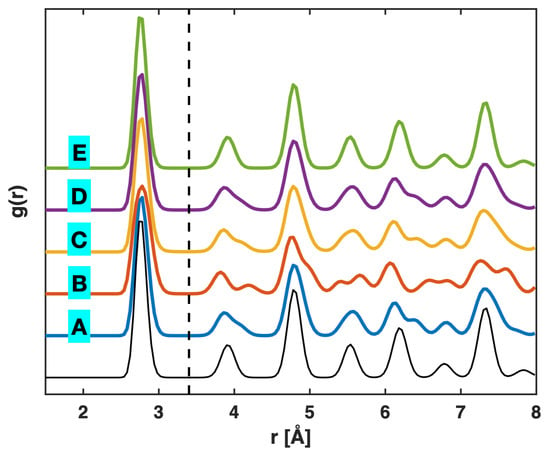

Figure 3 presents the radial distribution function (RDF) plots from the Pt tensile test, in the five states (A–E) marked on the stress–sample strain curve in Figure 1, as well as in the relaxed state (the bottom unlabeled curve) just before the start of tensile loading. The RDF is evaluated as the atomic number density within a radial distance of to around an average atom, normalized against the overall atomic number density in the material, i.e., , where , is the count of atoms within the radial bin from to , is the total number of atoms in the material, and is the sample volume (not simulation cell volume) [8,9]. The peaks in an RDF plot correspond to different coordination shells (first, second, and so on). In particular, the first RDF peak is associated with the first nearest-neighbor distance, which spans a certain range due to thermal vibrations, even in the relaxed state. Compared with the relaxed state prior to tensile loading, the elastic regime (state A) causes only mild modifications to the RDF, with slight peak broadening and minor peak splitting (see the 5th peak). At yielding (state B), the RDF exhibits more noticeable peak splitting, affecting multiple peaks. Right after yielding, in state C, the RDF rapidly recovers most of the features observed in the elastic regime (state A) and remains nearly unchanged throughout the subsequent plastic deformation regime (state D). Near fracture (state E), the RDF appears essentially identical to that of the relaxed state before tensile loading. Note that the RDF assessment was performed spherically around each atom (and averaged over all atoms); hence, it includes contributions from both the loading (longitudinal) and transverse directions, rather than specifically representing atomic distribution along the loading direction.

Figure 3.

Radial distribution function g(r) of the tensile-tested single-crystal Pt in the five states A, B, C, D, and E marked on the stress–sample strain curve in Figure 1. The bottom unlabeled curve represents the relaxed state just before the start of tensile loading. The vertical dashed line marks the upper bound of the first nearest-neighbor distance which is essentially unaffected by deformation.

From the RDF plots in Figure 3, it is observed that the valley between the first and second RDF peaks, that is, the upper bound of the first nearest-neighbor distance is essentially unchanged throughout the deformation process. This allows a constant cutoff distance to be used for bond identification in the following bond analysis, as well as in the G–L atomic strain determination discussed above.

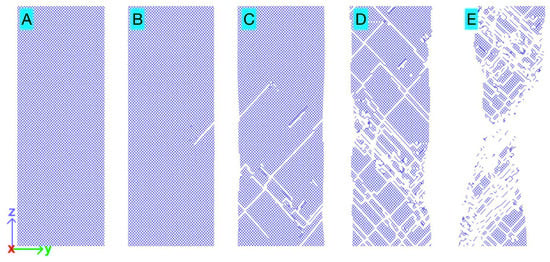

Figure 4 presents visualizations (snapshots) of atomic bonds in the tensile-tested Pt within a selected single atomic layer near the central x-position, spanning the full y-range and a reduced z-range that captures the final necking region (refer to the lower panel in Figure 1 for 3D views of the full sample). The five snapshots correspond to the five states (A–E) marked on the stress–sample strain curve in Figure 1. In the elastic regime (state A), the bonds are stretched in the z-direction (and compressed in the x and y directions), and the snapshot shows no broken bonds. At yielding (state B), the snapshot shows that some bonds have been broken due to the passage of the first-nucleated dislocations. In the subsequent plastic deformation, as more dislocations were dynamically generated (and annihilated) in the sample and moved through this atomic layer, the snapshots for states C, D, and E show an increasing number of broken bonds. It is important to note that the broken bonds observed in the single atomic layer do not represent actual “holes” in the structure. The atoms involved in the broken bonds are, in fact, reconnected with atoms in neighboring atomic layers through new bonds. At any step of plastic deformation, the remaining original bonds and the newly formed bonds work together to provide the structural integrity of the sample, requiring continued stress for further sample strain.

Figure 4.

Bond visualization in a selected area within the tensile-tested single-crystal Pt in the five states A, B, C, D, and E marked on the stress–sample strain curve in Figure 1. The area was selected to include only a single atomic layer (for clarity) perpendicular to the x-direction near x = 0, spanning the full range in y and a reduced z-range covering the final necking region.

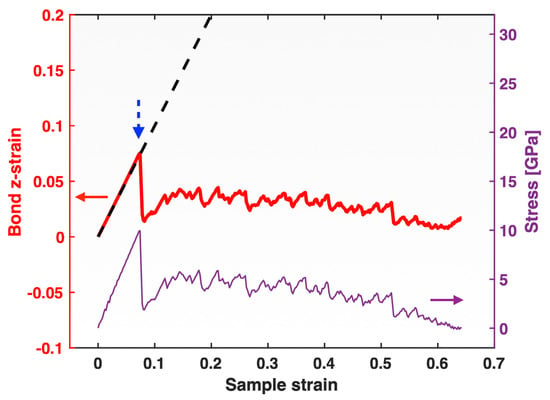

The red curve (thick solid line) in Figure 5 represents the atomic bond z-strain defined by Equation (3) (implemented in the loading direction), plotted against sample strain. Similar to the G–L atomic z-strain (shown in Figure 2), the bond z-strain closely matches the sample strain in the elastic regime, and deviates from it after yielding. However, unlike the G–L atomic z-strain, the bond z-strain does not increase to unphysically large values in the plastic regime. Instead, it exhibits a sharp drop upon yielding and then remains below the sample strain, while undergoing constant up-and-down fluctuations throughout plastic deformation. The overall behavior of the bond z-strain versus sample strain is reminiscent of the stress–sample strain behavior observed in Figure 1. Upon replotting the stress–sample strain curve (thin solid line) in the same Figure 5, it becomes evident that all the detailed fluctuations in the bond z-strain, erratic as they are, closely match those appearing in the stress throughout the extended plastic flow regime, except during the very final stage when the sample approached fracture (which will be discussed later).

Figure 5.

Bond z-strain (thick red line, left y-axis) along with stress (thin purple line, right y-axis) plotted versus sample strain for the single-crystal Pt tensile-tested at a strain rate of 10−4/ps. The dashed line is the sample strain (sharing the left y-axis) plotted versus itself, serving as a reference line for the bond z-strain plot. The blue dashed arrow marks the moment of yielding of the sample.

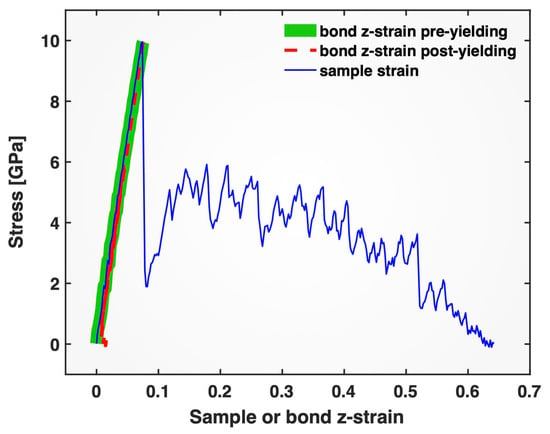

The close correlation between the bond z-strain and the sample stress appears even more striking when the stress is plotted directly against the bond z-strain, as shown in Figure 6 by the thick green line prior to yielding and the thin dashed red line after yielding. For comparison, the conventional stress versus sample strain plot (thin blue line) is also included in the same figure. In stark contrast to the well-known highly non-linear stress–sample strain correlation during plastic flow, the correlation between the stress and the bond z-strain remains nearly perfectly linear throughout the extended plastic regime (except for the very final fracture stage). In this presentation (Figure 6), the erratic fluctuations in both the stress and the bond z-strain seem to have disappeared, but this is only because their fluctuations are so well matched, as shown in Figure 5: whenever the bond z-strain increases, the sample stress increases, and whenever the bond z-strain decreases, the sample stress decreases, and their ratio, which can be understood as a “bond modulus” (sample stress over bond z-strain), remains nearly constant.

Figure 6.

Stress plotted versus bond z-strain (pre-yielding: thick green solid line; post-yielding: thin red dashed line) and sample strain (thin blue solid line) for the single-crystal Pt tensile-tested at a strain rate of 10−4/ps.

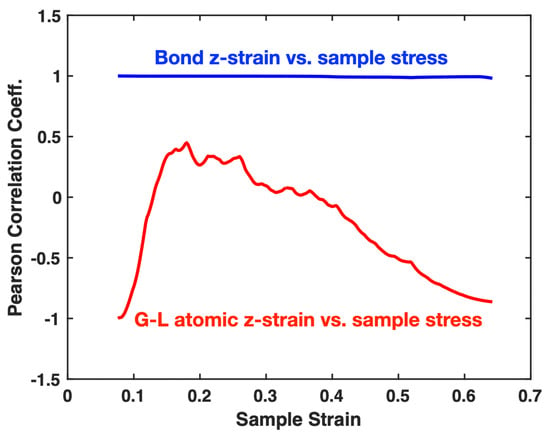

An alternative way to demonstrate the linear correlation between the bond z-strain and sample stress is the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC). For two data sets x and y, the PCC is defined as: , which ranges from −1 to +1, with +1 indicating a perfect positive linear correlation. Figure 7 shows the cumulative PCC values, calculated on a rolling basis starting from the yielding moment, for the bond z-strain versus sample stress, as well as for the G–L atomic z-strain versus sample stress, plotted against sample strain in the plastic deformation regime of the Pt sample. For the bond z-strain, the PCC remains nearly constant at 1 throughout the regime, indicating an almost perfect positive linear correlation with the stress. In contrast, the PCC for the G–L strain is significantly lower than 1 and exhibits erratic variations, suggesting no clear positive linear correlation with the stress.

Figure 7.

Cumulative Pearson correlation coefficients for the bond z-strain vs. sample stress and for the G–L atomic z-strain vs. sample stress, plotted against sample strain in the plastic deformation regime of the single-crystal Pt tensile-tested at a strain rate of 10−4/ps.

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 strongly suggest that what directly controls the apparent sample stress in both the elastic and the plastic regimes of deformation at nearly all times is the bond z-strain, which represents the degree of bond stretching in the tensile direction and involves all the existing bonds and atoms. While this is well expected for the elastic regime, its persistence into and throughout the extended plastic regime goes beyond conventional expectations and is revealed here only through our new atomic bond strain concept.

As mentioned in the Introduction, the conventional understanding of plastic deformation in crystalline materials is that dislocation activities (e.g., generation, motion, and annihilation), which involve only a small fraction of atoms, govern the apparent flow stress, and that the resulting stress–strain relationship is highly nonlinear. This seems to conflict with our results, which show that nearly all aspects of the stress behavior can be explained by a simple linear correlation with the bond z-strain, without invoking any quantities related to dislocations.

The apparent contradiction can be reconciled by considering dislocation activities as temporary interruptions to the stretching of bonds in the material. When a dislocation forms and moves, it not only breaks some old bonds and creates some new ones in its vicinity, but, more importantly, relaxes all bonds in the material, both old and newly formed, near and far from the dislocation. This relaxation reduces the overall bond stretching (i.e., bond z-strain) in the material, causing the apparent stress to drop. When a dislocation is stopped or annihilated, its bond-relaxing effect disappears, and the overall bond stretching in the material increases, resulting in a rise in the apparent stress.

With these causal relationships and the dislocation activities revealed in the middle panel of Figure 1, the near-linear correlation between the stress and the bond z-strain, the sharp drop in both upon yielding, and their erratic but synchronous fluctuations throughout the extended plastic flow regime can be well understood.

At the very final stage of the Pt tensile test shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the bond z-strain exhibits a slight increase while the stress continues to decrease toward zero. This small deviation from the main trend discussed above can be attributed to the highly localized necking region just before fracture, as seen in the last frame (E) of the middle or bottom panel in Figure 1. The highly localized necking causes a severe spatial decoupling between the stress and bond z-strain contributors. The bonds within the necking region make a significant contribution to the stress, whereas the vast majority of bonds outside this region dominate the overall bond z-strain, leading to the observed discrepancy between the stress and bond z-strain behaviors.

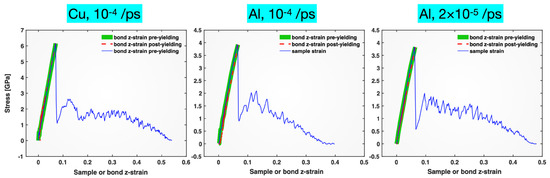

The core results presented above for the Pt tensile test are similar to those obtained for the Cu and Al single crystals tensile-tested at strain rates of 10−4 or 2 × 10−5/ps. The plots of the stress versus the bond z-strain and the sample strain from these other materials/tests are provided in Figure 8. They all show the striking near-linear correlation between the stress and the bond z-strain in both the elastic and the plastic deformation regimes.

Figure 8.

Stress plotted versus bond z-strain (pre-yielding: thick green solid line; post-yielding: thin red dashed line) and sample strain (thin blue solid line) for single-crystal Cu (left), Al (middle) and Al (right) tensile-tested at a strain rate of 10−4, 10−4, and 2 × 10−5/ps, respectively.

4. Conclusions

We have applied our new strain measure, the atomic bond strain, to analyze MD-simulated tensile deformation behavior of Pt, Cu, and Al, three representative FCC metals, in comparison with the conventional G–L atomic strain. The G–L atomic strain accurately captures the overall sample strain in the elastic regime, but loses its physical validity and fails to represent either the sample strain or stress in the plastic regime. The atomic bond strain, in contrast, retains its physical validity throughout the deformation. In the elastic regime, it also accurately captures the sample strain. At yielding and during the subsequent extended plastic regime, the atomic bond strain exhibits almost identical behavior (including up-and-down fluctuations) to the sample stress. Direct plots of the stress versus the atomic bond strain reveal a striking nearly perfect linear correlation between the two, in both the elastic and the plastic regimes, suggesting that the atomic bond strain (involving all bonds and all atoms) directly controls the stress at nearly all times. This finding appears in sharp contrast to the widely recognized nonlinear characteristic of plastic deformation, and the common conception that dislocation activities involving a small fraction of atoms govern the plastic flow stress of crystalline materials. The apparent contradiction can be reconciled by considering dislocation activities as temporary interruptions to bond stretching and the level of bond stretching directly determining the flow stress.

The results in this work offer a new perspective on the fundamental nature of plasticity in crystalline materials, enabled by our recently proposed atomic bond strain concept. Expanding this approach to non-FCC metals and alloys, single crystals, polycrystals, quasicrystals, and even amorphous solids (such as metallic glasses) is an intriguing and important direction for future research, which could fundamentally reshape our understanding of materials mechanics.

As an outlook, the new atomic bond-strain perspective introduced here has the potential to impact several areas. First, it may lead to a more unified picture of elastic constants, Poisson’s ratio, yielding criteria, and flow stress across different material systems in which dislocations play varied roles. Second, it may inspire new strategies for designing materials with improved strength and/or ductility by tailoring bond-strain characteristics (e.g., stretchability and rotatability). Third, in certain material systems where deformation proceeds via twinning or phase transformations rather than dislocations, the atomic bond-strain perspective may reveal more fundamental insights into these mechanisms, as twinning and mechanically induced phase transformations involve bond-topology reorganizations. Finally, the new perspective may also enhance our understanding of physical and chemical properties closely related to bond strain, such as melting temperature, phonon spectrum, reactivity, and catalytic activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, D.X.; validation, formal analysis, and investigation, D.X., T.T. and N.S.; resources, D.X.; writing—original draft preparation, D.X.; funding acquisition, D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under grants No. DMR 2221854 and CMMI 2525114.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The molecular dynamics simulations were conducted on the High Performance Computing Cluster maintained by the College of Engineering, Oregon State University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Callister, W.D.; Rethwisch, D.G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, 9th ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Incorporated: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.F.; Hashemi, J. Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Askeland, D.R.; Wright, W.J. The Science and Engineering of Materials, Enhanced, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.; Plimpton, S.; Mattson, W. General formulation of pressure and stress tensor for arbitrary many-body interaction potentials under periodic boundary conditions. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 154107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mott, P.; Argon, A.; Suter, U. The Atomic Strain Tensor. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 101, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.L.; Langer, J.S. Dynamics of viscoplastic deformation in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 57, 7192–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, F.; Ogata, S.; Li, J. Theory of shear banding in metallic glasses and molecular dynamics calculations. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 2923–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Gordon, O.; Ye, M.; Chen, L.; Thaiyanurak, T.; Wang, Z. Non-Equal Contributions of Different Elements and Atomic Bonds to the Strength and Deformability of a Multicomponent Metallic Glass Zr47Cu46Al7. Molecules 2024, 29, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaiyanurak, T.; Gordon, O.; Ye, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, D. Compositional Effects on the Tensile Behavior of Atomic Bonds in Multicomponent Cu93-xZrxAl7 (at.%) Metallic Glasses. Molecules 2025, 30, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.M.; Hirth, J.P.; Lothe, J. Theory of Dislocations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nabarro, F.R.N. Theory of Crystal Dislocations; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, D.; Bacon, D.J. Introduction to Dislocations, 3rd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nix, W.; Lee, S. Micro-pillar plasticity controlled by dislocation nucleation at surfaces. Philos. Mag. 2011, 91, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nix, W. Yielding and Strain Hardening in Metallic Thin Films on Substrates: An Edge Dislocation Climb Model. Math. Mech. Solids 2009, 14, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Eckert, J.; Löser, W.; Schultz, L. Novel Ti-base nanostructure-dendrite composite with enhanced plasticity. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Hu, W.; Datye, A.; Liu, J.; Schroers, J.; Schwarz, U.; Yu, J. Revealing the relationships between alloy structure, composition and plastic deformation in a ternary alloy system by a combinatorial approach. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Oh, H.; Gludovatz, B.; Kim, S.; Park, E.; Zhang, Z.; Ritchie, R.; Yu, Q. Real-time observations of TRIP-induced ultrahigh strain hardening in a dual-phase CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schall, P.; Cohen, I.; Weitz, D.; Spaepen, F. Visualization of dislocation dynamics in colloidal crystals. Science 2004, 305, 1944–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; Veld, P.J.I.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D.; et al. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular-Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO-the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.