Abstract

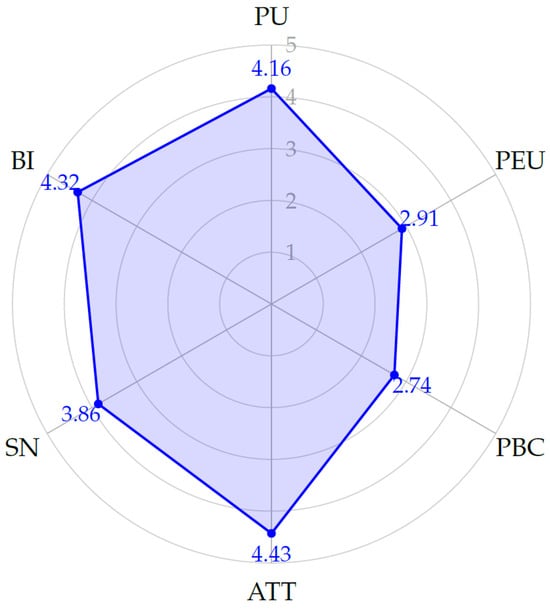

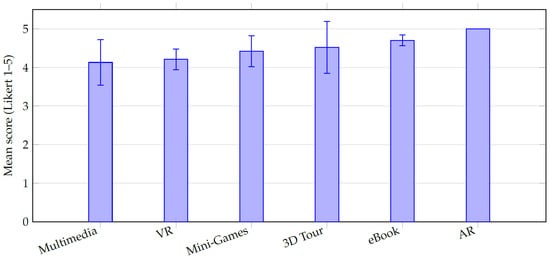

Cross-modal and immersive technologies offer new opportunities for experiential learning in early childhood, yet few studies examine integrated systems that combine multimedia, mini-games, 3D exploration, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR) within a unified environment. This article presents the design and implementation of the Solar System Experience (SSE), a cross-modal extended reality (XR) learning suite developed for preschool education and deployable on low-cost hardware. A dual-perspective evaluation captured both preschool teachers’ adoption intentions and preschool learners’ experiential responses. Fifty-four teachers completed an adapted Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) questionnaire, while seventy-two students participated in structured sessions with all SSE components and responded to a 32-item experiential questionnaire. Results show that teachers held positive perceptions of cross-modal XR learning, with Subjective Norm emerging as the strongest predictor of Behavioral Intention. Students reported uniformly high engagement, with AR and the interactive eBook receiving the highest ratings and VR perceived as highly engaging yet accompanied by usability challenges. The findings demonstrate how cross-modal design can support experiential learning in preschool contexts and highlight technological, organizational, and pedagogical factors influencing educator adoption and children’s in situ experience. Implications for designing accessible XR systems for early childhood and directions for future research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Digital technologies have become deeply embedded in children’s everyday lives, shaping how they play, communicate, and explore the world through richly mediated environments [1]. From animated stories and interactive videos to early learning apps and mobile games, preschool-aged children today encounter a wide spectrum of digital experiences both at home and in educational settings. This pervasive exposure has motivated educators and researchers to explore how such technologies can be reimagined not merely as entertainment, but as tools that nurture curiosity, creativity, and active learning from an early age [2]. At the same time, this growing ubiquity underscores the need for intentional, developmentally appropriate, and pedagogically grounded designs that move beyond isolated applications toward coherent, classroom-ready learning experiences.

Among emerging innovations, immersive and interactive media such as Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR)—collectively referred to as Extended Reality (XR)—along with interactive eBooks and serious games, are uniquely positioned to offer distinctive opportunities for experiential and multi-sensory learning [3]. These environments can allow learners to visualize abstract phenomena, manipulate digital objects, and observe the consequences of their actions within controlled yet vivid settings [4]. In preschool contexts, such experiences align naturally with experiential [5] and constructivism [6] learning theories that emphasize learning through doing, observing, and reflecting [7]. However, their effective use requires careful calibration of complexity, scaffolding, and cognitive load [8], making it essential to integrate immersive modalities into broader pedagogical sequences rather than treat them as standalone novelty tools.

Educational research has long recognized that no single medium suffices to address the diverse cognitive, affective, and social needs of young learners. Cross-modal or multimodal approaches—combining visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and interactive components—are increasingly viewed as essential for fostering deep and sustained engagement [9]. When properly orchestrated, sequences of complementary media (e.g., video, game, eBook, VR/AR) can balance structure and exploration, providing a continuum from guided instruction to open discovery [10]. Yet, despite strong theoretical support, empirical work demonstrating the classroom feasibility of such approaches in early childhood education remains limited. Most existing studies examine single applications or isolated prototypes, leaving open how full ecosystems of interconnected modalities can be designed, implemented, and evaluated in real preschool environments.

Successful implementation depends not only on children’s capabilities but also on teachers’ readiness, confidence, and perceived institutional support [11]. Teachers’ perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, and normative expectations play decisive roles in shaping the adoption of emerging technologies [12]. Early childhood educators often express enthusiasm but face infrastructural limitations, lack of training, and curricular pressures when introducing XR-driven activities [13]. Accordingly, evaluating immersive media in early childhood requires a dual lens: examining (a) teachers’ adoption intentions and pedagogical readiness prior to implementation, and (b) children’s in situ experiential responses during authentic classroom use. These complementary viewpoints help determine both feasibility and actual educational value.

To address these needs, the present study introduces and evaluates a cross-modal immersive educational game developed for Greek preschool education, targeting, as a case study, specific curricula modules that blend technology-oriented activities with space science concepts. The game, suitably named “Solar System Experience” (SSE), rather than privileging a single technology, brings together complementary components. In essence, it comprises an interactive media suite of short multimedia clips, playful mini-games, an interactive eBook with quizzes, three-dimensional (3D) space exploration applications (in free- and guided-tour modes), and XR modules in VR and AR, organized around a common educational theme: the Solar System. The design embodies the principle that different modalities contribute uniquely to learning, with structured media providing conceptual clarity and immersive media eliciting emotional engagement and curiosity. The system was implemented and evaluated in real preschool classrooms to examine both feasibility and pedagogical impact. Importantly, the suite was engineered to operate on accessible, low-cost hardware commonly found in Greek schools, ensuring that the proposed approach remains realistic and scalable within typical early childhood education contexts.

Under this light, the study’s contribution is multifaceted:

- It proposes a cross-modal XR learning framework tailored to early childhood, demonstrating how conventional and immersive technologies can be sequenced to scaffold understanding through multisensory engagement. This framework concretizes how different modalities can be aligned to support progressive conceptual development in preschool learning.

- It presents an integrated design and implementation of a complete educational game suite (i.e., the SSE) based on this framework, articulating how VR, AR, interactive eBooks, and mini-games can coexist within a coherent pedagogical narrative. Rather than describing isolated components, the study treats SSE as a unified software learning ecosystem, detailing its technical and pedagogical interconnections and offering an implementable model for multimodal orchestration within realistic classroom conditions.

- It conducts a dual-perspective evaluation combining teachers’ adoption intentions with students’ in situ experiences characterized by high granularity, providing a holistic view of feasibility, usability, engagement, and educability across modalities. Here, “dual-perspective evaluation” refers explicitly to the combined analysis of teachers’ responses, guided by an adapted Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [14] and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [15] assessment instrument, alongside kindergarten students’ experiential ratings during actual classroom use. These perspectives are grounded in authentic Greek preschool curricular interventions.

- It derives empirically grounded guidelines for designing and implementing experiential learning in preschool contexts, bridging the gap between theoretical promise and classroom practice. These guidelines synthesize insights across system design, cross-modal sequencing, and parallel evaluation perspectives.

Together, these contributing aspects aspire to advance the understanding of how cross-modal interactive and immersive media can support meaningful, age-appropriate, and experiential learning in early childhood education. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has explored such cross-modality while collecting parallel empirical data from both preschool teachers and learners in relation to immersive XR learning.

Accordingly, the study addresses a clearly articulated research gap by treating SSE as a software learning ecosystem and evaluating both its adoption conditions and its interaction performance in situ. To guide the empirical evaluation and structure the dual-perspective analysis, the following research questions (RQs) are formulated:

- RQ1.

- How do preschool teachers perceive the design, usability, and classroom applicability of the SSE cross-modal XR learning suite, and which factors shape their behavioral intention to adopt such a system in their teaching practice?

- RQ2.

- How do preschool students experience and evaluate the different components of the SSE suite as a digital learning system, in terms of usability, engagement, and comparative experiential quality across modalities?

Beyond addressing RQ1 and RQ2, the SSE suite and accompanying dual-perspective evaluation serve as a replicable blueprint for cross-modal XR ecosystems in preschool education. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature; Section 3 outlines the methodological approach; Section 4 presents the design of the SSE; Section 5 details the applications; Section 6 reports teacher and student results; Section 7 synthesizes implications; and Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Immersive, interactive, and multimodal technologies have increasingly attracted scholarly attention as potential drivers of enriched learning experiences across educational levels. While prior research highlights the benefits of discrete technologies such as VR, AR, or serious games, a growing body of work stresses the importance of multimodal orchestration rather than isolated interventions. Accordingly, this section synthesizes three key strands of literature relevant to the present study: (i) VR and AR in education; (ii) serious games and gamification; and (iii) cross-modal and multimedia approaches for experiential learning.

2.1. Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality in Education

Virtual Reality has been explored as an educational tool for more than three decades. Early definitions conceptualized VR primarily in terms of immersion and telepresence [16], establishing its foundation as a medium capable of fostering a sense of “being there”. Subsequent frameworks, such as the I3 paradigm (Interaction, Immersion, Imagination) [17], extended this foundation by emphasizing VR’s multisensory affordances (visual, auditory, and occasionally haptic), thereby framing VR as a technology suited for experiential learning [18].

Contemporary systematic reviews have demonstrated consistent benefits of VR for increasing motivation, engagement, inclusion, and conceptual understanding across education domains [19,20,21]. VR’s contribution to conceptual learning is especially notable in contexts that require visualization of abstract or non-intuitive phenomena, as VR environments can situate learners within dynamic, manipulable representations that facilitate conceptual change [22]. Moreover, immersive VR experiences have been shown to enhance affective engagement, attention, and memory retention [23], and to support the development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills [24]. These findings align with experiential learning theories [25] and emerging evidence on embodied cognition [26], illustrating how immersive interaction can strengthen perceptual grounding and conceptual clarity.

Though VR’s capability to facilitate a visual understanding of complex concepts for students and, hence, reduce misconceptions, is undeniable [27,28], research in early childhood education remains more limited, albeit steadily expanding. Existing studies show that when VR is adapted to the developmental needs of young children—through simplified interfaces, short sessions, and guided facilitation—it can support exploratory learning, curiosity, and spatial reasoning [29]. However, challenges persist, including cognitive load, motion sickness, usability constraints, and the need for adult mediation [30]. Low-cost mobile VR solutions (e.g., Google Cardboard) offer accessible alternatives, particularly in resource-limited school contexts, though they demand careful interaction design (e.g., gaze-based selection, sensory stabilization) [31]. Recent reviews further emphasize that VR’s educational impact is maximized when embedded within a pedagogical framework that ensures conceptual integration rather than technological novelty [19].

Augmented Reality differs from VR by overlaying digital content onto the physical environment [32], creating hybrid learning spaces that combine tangible interaction with digital augmentation. AR supports situated and embodied learning, enabling young learners to explore concepts through manipulation of 3D models, markers, or physical artifacts [33]. Reviews have demonstrated AR’s positive effects on motivation, spatial understanding, and conceptual acquisition [34,35]. In preschool contexts, AR has been applied to storytelling, science education, and language development [36], typically through marker-based systems or tablet-mediated interactions. AR’s lower cognitive and physical demands, relative to VR, make it particularly suitable for early childhood classrooms both from learner [8] and educator [11] standpoints.

Studies suggest that AR can foster fine motor skills, collaborative exploration, and early scientific reasoning, especially when 3D models or gamified elements are incorporated [37,38], even more so than 2D material [39]. Yet, scholars also emphasize that AR’s educational effectiveness depends not only on technological quality but on pedagogical orchestration, including task structure, scaffolding, and alignment with curricular goals [40].

Together, the VR and AR literature indicates strong potential for immersive learning in preschool settings [3], while underscoring the need for thoughtful, developmentally appropriate design. In the present study, these insights are realized through low-cost, classroom-ready VR and AR modules that are embedded in a broader cross-modal sequence rather than deployed as stand-alone prototypes.

2.2. Serious Games and Gamification in Education

Serious games integrate instructional objectives within interactive game environments [41,42], drawing on principles of feedback, challenge, and narrative to support cognitively meaningful learning. Meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that serious games can outperform traditional instructional methods in terms of knowledge acquisition, engagement, and retention [43,44]. These effects are particularly pronounced when game mechanics are conceptually aligned with learning goals rather than appended superficially.

Beyond cognitive gains, serious games can enhance visual–spatial abilities and problem-solving skills [45]. Such effects may be further supported when game experiences incorporate immersive or semi-immersive interaction, as reflected in the I3 paradigm [17]. As such, they provide structured opportunities for experiential learning through iterative experimentation and active manipulation, resonating strongly with constructivism learning frameworks and experiential theories [6,46]. When combined with VR/AR affordances, game-based environments may also leverage heightened presence and curiosity, contributing to deeper engagement [47].

From a pedagogical perspective, serious games can help counteract the limitations of linear, didactic teaching by encouraging active participation and self-directed exploration [48]. The literature further indicates that game-based learning can foster intrinsic motivation, curiosity, and emotional involvement, provided that challenges are developmentally appropriate and scaffolded to support young learners’ needs [49].

Gamification, defined as the use of game-like elements (e.g., points, badges, quests) in non-game contexts [50], has emerged as a complementary approach for enhancing engagement in early childhood education [51]. However, evidence suggests that simple “pointification” yields short-lived motivational effects [52]. More effective implementations rely on deeper gamification structures, including narrative progression, meaningful feedback loops, and exploratory challenges that connect with learners’ intrinsic interests [53]. A major meta-analysis [54] found that although educational gamification tends to rely heavily on reward systems, future research should prioritize richer, constructivism-supportive gamification models. This aligns with the present study’s emphasis on integrating game mechanics and gamified feedback within a broader, sequenced learning pathway (from conventional media to semi-immersive 3D to XR), rather than relying primarily on extrinsic rewards.

2.3. Cross-Modal Educational Approaches

Preschool learning environments increasingly favor concrete, multisensory experiences that help young children build conceptual understanding through active engagement and perceptual grounding. As such, immersive and multimodal technologies—whether VR, AR, games, or interactive media—offer important opportunities for enriched inquiry-based learning [55]. However, several studies emphasize that developmental appropriateness depends on careful orchestration: interaction design must remain simple, sessions short, and adult mediation consistent [56].

While much research focuses on the educational impact of individual technologies, multimedia learning theories underscore that no single modality is sufficient for supporting the diverse cognitive and affective needs of young learners [57]. Instead, structured combinations of modalities can promote deeper, more durable learning outcomes [58]. Videos and animations are effective for initial explanation and attention capture; games support active experimentation; interactive books foster narrative comprehension and literacy; and VR/AR environments provide spatial immersion and hands-on manipulation [23]. A progression across these media supports a shift from guided to exploratory learning while maintaining conceptual continuity.

Studies on multimodal sequencing demonstrate that combining modalities across the VR–AR continuum can significantly enhance motivation, comprehension, and retention compared to single-medium approaches [59]. Moreover, multimodal systems can support early “precision education”, offering adaptive pacing and personalized resources based on learner needs [60].

Recent advances in embodied learning theory reinforce the importance of designing for movement, sensory engagement, and physical interaction. Embodied cognition frameworks posit that understanding emerges through perceptual-motor experience, which can be amplified by XR environments where learners actively navigate or manipulate content [26]. This is particularly relevant in preschool contexts where bodily engagement is a core mechanism for meaning-making.

Despite these advantages, the applicability of immersive and multimodal tools remains uneven across educational contexts. Schools vary widely in technological infrastructure, teacher preparedness, and socio-economic conditions, leading to persistent digital divides that directly impact whether XR and multimodal solutions can be implemented effectively [61]. These disparities not only shape access to devices but also affect instructional coherence, as teachers may lack the training or institutional support needed to integrate complex digital modalities into existing curricula.

Moreover, multimodal learning environments are most effective when accompanied by appropriate and adaptive scaffolding [62]. Young children benefit from teacher mediation, predictable interaction metaphors, and structured exploration paths that balance autonomy with guidance [56]. Designing such scaffolds requires aligning digital affordances with pedagogical intentions so that cognitive load remains manageable during highly stimulating XR experiences.

Research also highlights that much of the existing work on immersive media for children focuses on isolated modules (e.g., one AR activity, one VR prototype, or a single serious game), and rarely addresses how such tools can be combined in coherent learning ecosystems. Few studies investigate cross-modal progressions (e.g., moving from videos, to mini-games, to interactive books, to XR), despite theoretical frameworks strongly supporting such orchestrated learning sequences. Evidence suggests that carefully sequenced multimodal systems can produce synergistic effects, yet empirical validation remains limited, particularly in preschool settings. The SSE suite directly addresses this gap by implementing and empirically evaluating such a cross-modal progression with both teacher and student data in authentic preschool classrooms.

2.4. Research Gap

Across the literature on VR/AR in education, serious games, gamification, and cross-modal learning, several gaps emerge that motivate the present study.

- Most empirical research examines single-modality systems in isolation, offering limited insight into how diverse technologies can be orchestrated into unified pedagogical workflows. This creates a disconnect between theoretical arguments for multimodal integration and actual classroom practice. For example, the work in [63] investigates a multimodal educational game for first-grade learners using audiovisual animation but without XR components. Other studies [8,64] examine the benefits of AR for motivation and conceptual understanding, but remain restricted to AR-only approaches. Similarly, [65] compares traditional teaching to VR-enhanced instruction, focusing exclusively on VR. Collectively, these studies highlight isolated modality use rather than cross-modal orchestration.

- Very few works present technically integrated XR ecosystems that combine multiple modalities around a common thematic narrative—particularly in early childhood education. Although gamification is blended with VR in [66] and with AR in [67], to our knowledge no existing system integrates multimedia, mini-games, interactive books, 3D exploratory environments, and both VR and AR within a coherent workflow. Existing systems are typically domain-specific, hardware-intensive, or targeted at older learners, leaving a gap in accessible, age-appropriate XR ecosystems for preschool contexts. In contrast, the SSE suite combines these components so that immersive experiences function within a broader educational sequence rather than as stand-alone interventions, thereby providing a technically unified and pedagogically orchestrated ecosystem beyond the single-modality focus of prior work.

- Cross-modal research rarely addresses practical constraints such as low-cost hardware, limited infrastructure, or varying teacher readiness—factors especially relevant in public preschool environments such as Greek schools [68]. Few studies explore how immersive tools can be adapted for equitable use in resource-constrained classrooms. In view of this gap, the current study demonstrates how such modalities can be integrated coherently and developmentally appropriately in real preschool classrooms under everyday constraints.

- Although teacher readiness is recognized as a critical determinant of adoption [12,13], few evaluations integrate both educator and learner perspectives within the same study (e.g., [39,64,65]). Some works discuss implications for both groups [9,69], yet they do not directly link the perceptions of those implementing immersive systems (teachers) and those experiencing them (students). There remains a lack of dual-perspective, field-based evaluations that combine (a) validated adoption models for teachers and (b) fine-grained, module-level experiential data from preschool learners.

The present study addresses these limitations by introducing the SSE, a fully integrated, low-cost cross-modal educational suite designed specifically for preschool learners. It contributes: (i) a pedagogically coherent XR ecosystem spanning multimedia, games, interactive books, VR, and AR; (ii) realistic implementation under everyday classroom constraints; and (iii) a dual-perspective evaluation incorporating both teacher adoption intentions and children’s in situ experiential responses. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to investigate such a system using a cross-modal, developmentally appropriate, and resource-aware design in Greek preschool education.

3. Methods

Teaching in primary school often takes the form of projects [70], which may stem from children’s in-class activities or be guided by the kindergarten teacher within a broader learning framework. Within this context, topics are typically approached interdisciplinarily: knowledge is built through multiple curricular perspectives, aiming at children’s holistic development while strengthening soft skills, creative communication, and collaboration in an organized learning environment [71].

In the present study, these pedagogical principles were translated into a structured methodological process that guided the design, development, and orchestration of the cross-modal SSE suite. The following subsections outline the hybrid development model, the pedagogical and interaction design principles adopted, and the technical workflow used to integrate multiple digital modalities into a coherent educational system.

3.1. Development Methodology: Hybrid ADDIE and FDD

To facilitate the development of the SSE, instructional design modeling [72] was taken into consideration. Instructional Design Models (IDM) have been proposed in the literature as an effective means for creating educational games [47]. In the present work, the development of the SSE followed a hybrid methodological approach that combined (i) the “Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation” (ADDIE) IDM and (ii) a “Feature-Driven Design” (FDD) software engineering process. This hybridization reflects the dual nature of the project, i.e., educationally grounded yet technically complex.

ADDIE [73] provided an overarching structure for the entire project. The Analysis phase examined preschool developmental characteristics, curricular constraints, and infrastructural limitations in Greek kindergartens. The Design phase (see Section 4) specified learning objectives, cognitive load boundaries, interaction metaphors, and cross-modal sequencing. During Development (see Section 5), assets and prototypes were iteratively implemented in Unity and web technologies. Implementation involved staged classroom testing, and Evaluation consisted of dual-perspective data collection from teachers and students (see Section 6).

FDD [74,75] complemented ADDIE by structuring the engineering of each system component into small, testable feature units. Each SSE application (3D tour, interactive eBook, AR marker system, VR gaze-based interface) was treated as a feature cluster. For every feature, the workflow included breakdown, class and object modeling in Unity, functionality scripting, iterative prototyping, and refinement based on early testing. This ensured modularity, efficient debugging, and parallel development across the suite.

Table 1 synthesizes how ADDIE and FDD jointly shaped the design and implementation of each SSE application, illustrating how pedagogical goals and development practices were aligned throughout the production lifecycle.

Table 1.

Summary of ADDIE and FDD application across the SSE modules.

The combination of ADDIE and FDD enabled SSE to maintain educational coherence at the macro level while supporting precise feature construction at the micro level. This hybrid process is particularly suitable for preschool XR systems, where pedagogical soundness and low-friction interaction must be balanced with software robustness.

3.2. Pedagogical and Interaction Design Principles

Building on the literature reviewed in Section 2, the SSE embodied principles from experiential learning, multimodal learning theory, and embodied cognition.

Experiential learning [76,77] informed the design of activities that require observation, hands-on interaction, and reflective engagement. The SSE’s cross-modal sequence, from videos to games, to 3D exploration, to XR immersion, and so on, mirrors experiential learning cycles by gradually increasing agency and sensory involvement.

Multimodal learning theory [57] guided the orchestration of complementary media types. Structured content (e.g., multimedia, eBook) was used for conceptual introduction, while exploratory or immersive content (e.g., 3D, VR, AR) was introduced later to deepen affective engagement and reinforce spatial understanding.

Embodied learning [10,26] informed interaction design by encouraging movement, manipulation of digital objects, and sensory-rich engagement. Aligning with recent research [78], this was especially evident in the 3D and XR components, where learners explored spatial relations through camera motion, head-tracking, or device movement.

To enhance user experience (UX) and ensure developmental appropriateness for preschool students, the SSE incorporated: (1) low-complexity interaction metaphors (point-and-click, drag, tap, gaze dwell), (2) short interaction loops to fit attention spans, (3) structured transitions between modalities to regulate cognitive load, and (4) consistent iconography and user interface (UI) design across all applications. These principles ensured the SSE components remained intuitive, predictable, and pedagogically aligned with preschool learners’ attentional and motor profiles (e.g., working-memory capacity and emergent fine-motor control), enabling learners to navigate increasingly complex modalities without becoming overwhelmed and without allowing interaction demands to overshadow the underlying conceptual goals. Concretely, this was tackled through short interaction loops, single-action input schemes (e.g., tap, click, dwell), and predictable cause and effect mappings appropriate for preschool learners.

3.3. System Architecture and Design Workflow

The SSE was implemented as a modular ecosystem comprising web-based applications, 3D game environments, mobile XR modules, and supporting pedagogical materials. A cross-modal workflow ensured smooth transitions between modalities; each component was built as an independent module following FDD principles but aligned through shared narrative elements, consistent UI metaphors, and compatible input schemas. As a result, SSE functions as a cohesive ecosystem rather than a set of disconnected applications.

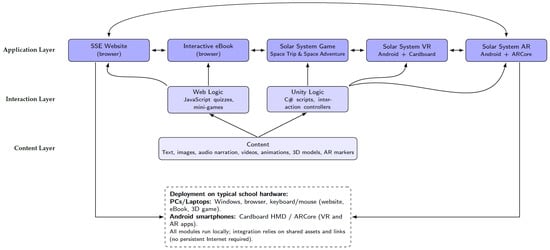

Architecturally, the system follows a three-layer design: (i) an application layer, which includes the website, interactive eBook, game interfaces, and XR modules that pupils directly engage with; (ii) an interaction layer, implemented mainly in Unity (C# scripts) and JavaScript (JS), which handles interaction mechanics (e.g., gaze-based selection, puzzle logic, 3D navigation, quiz progression) and state transitions between modules; and (iii) a content layer, which stores multimedia assets (videos, images, audio narration, animations), 3D models, and AR markers used across the suite. Communication between layers is deliberately simple and file-based (e.g., local asset bundles and web links) to avoid complex networking requirements and to ensure that individual components can be deployed independently on typical school hardware.

Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of this architecture, illustrating how the web front-end (website and eBook) acts as an access hub and content anchor, while Unity-based 3D, VR, and AR modules form the interactive core. The schematic also highlights the deployment topology; web components are served through standard browsers on laptops or tablets, whereas Unity applications run locally on Windows laptops (3D) and Android smartphones (XR), with all devices relying on local execution rather than persistent Internet connectivity. This arrangement reflects typical ICT conditions in Greek public schools, where network reliability and centralized server infrastructure cannot be assumed.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the SSE system architecture, showing the three-layer structure formed by the content, interaction logic and the SSE applications, their interconnection as a cross-modal workflow, as well as their deployment on typical school hardware (PCs/laptops and Android smartphones with Cardboard/ARCore).

Web-based components (website, interactive eBook, multimedia) were developed using standard HTML/CSS/JS for maximum compatibility with the browsers and devices commonly found in Greek public schools [68]. This decision reflects an intentional low-cost strategy rooted in the infrastructural realities of early childhood education, where specialized hardware is rarely available [61].

3D Space touring applications (Space Trip and Space Adventure) were developed in Unity, enabling real-time rendering, responsive camera systems, and lightweight physics calculations suitable for intuitive exploration. Interaction design prioritized stability and predictability. Hence, students move through space using simple controls, and information is surfaced via point-and-click mechanics, minimizing motor demands. Frame rates and polygon budgets were constrained during development so that 3D scenes remain responsive on mid-range laptops with integrated graphics.

XR modules (VR and AR) were also implemented in Unity using the Google Cardboard XR Plugin and AR Foundation with ARCore, respectively, and taking into account the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) sensors of mobile devices (e.g., accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer). These tools were selected because they support accessible, low-cost hardware and provide stable pipelines for mobile-based gaze interaction (VR) and image-marker tracking (AR). This technical decision aligns with pedagogical constraints; that is, XR experiences must remain brief, intuitive, and comfortable for young learners. In practice, this meant limiting the number of concurrent dynamic objects in view, simplifying shaders and lighting, and carefully tuning camera motion to accommodate the limited field-of-view and basic inertial sensors of mid-range smartphones.

To ensure coherence across modalities, a unified design system was created, covering visual identity (color palettes, layouts, iconography), standardized interaction elements (buttons, panels, markers), common feedback mechanisms (audio cues, assistive popups, subtle animations), and a uniform narration style. This consistency reduced cognitive load and prevented disorientation when moving from 2D interfaces to 3D or XR formats, supporting a structured progression from familiar to immersive experiences.

3.3.1. Implementation Stack and Technical Constraints

To complement the architectural overview and clarify how technical constraints informed the cross-modal design workflow, Table 2 summarizes the core elements of the SSE implementation stack and their corresponding pedagogical and interaction implications. These aspects are described in detail in upcoming sections.

Table 2.

Implementation stack and technical constraints shaping the SSE design.

3.3.2. System Specifications and Testing Environment

The SSE was developed and evaluated (see Section 6) using accessible, low-cost consumer hardware representative of the typical Information and Communications Technology (ICT) infrastructure available in Greek schools. Table 3 summarizes the exact hardware and software configurations used during development and classroom testing.

Table 3.

Hardware and software specifications used for development and testing of the SSE suite.

These configurations reflect the ongoing digital divide and ICT disparities among Greek schools, where specialized high-end equipment or reliable technical support are often absent. Most primary schools still rely on basic Internet connectivity and low-cost devices such as laptops, tablets, and projectors [68]. Designing SSE to run smoothly on affordable hardware therefore maximizes its potential penetration in both educational environments and student households.

At the same time, hardware limitations (e.g., occasional FPS (frames per second) drops, thermally induced performance throttling during extended VR use, and reduced gyroscope accuracy) informed concrete implementation choices. For example, VR scenes were optimized by restricting dynamic light sources and simplifying shaders, limiting the number of simultaneously visible celestial bodies, and using baked lighting where possible. Similarly, AR tracking was tuned for robustness in typical classroom lighting, with printed markers sized for reliable detection by mid-range cameras. These measures helped keep latency, tracking jitter, and visual clutter within tolerable bounds for preschool users while preserving the educational fidelity of the Solar System representation.

3.4. Cross-Modal Orchestration Strategy

A central methodological goal was to orchestrate modalities in a developmentally appropriate sequence that mitigates overload by establishing conceptual structure before introducing spatially and sensory-rich experiences. In alignment with Cognitive Load Theory [79], this would improve memory processing and understanding of information by regulating intrinsic and extraneous load through careful modality sequencing. SSE therefore adopts a progressive immersion strategy, beginning with familiar, low-friction formats and gradually introducing more complex or immersive ones: (1) multimedia clips, (2) mini-games, (3) interactive eBook, (4) 3D exploration (Space Trip and Space Adventure), and (5) XR immersion (VR and AR). Each step increases agency, interactivity, and sensory complexity while maintaining conceptual continuity, in line with multimodal learning frameworks [57], scaffolded discovery [56], and embodied learning [10].

This sequence was initially defined during the Analysis and Design phases of ADDIE and then refined through pilot testing observations during Implementation. The goal was to help pupils maintain focus, reduce confusion, and facilitate smoother transitions into more demanding XR experiences. Accordingly, the early steps (segmented clips, short games, and eBook activities) provide a stable scaffold that reduces the likelihood of cognitive overload during later XR exposure.

Additionally, several of these design choices also serve accessibility needs, since short, segmented activities, minimal text dependency, large visual cues, and predictable interaction structures can support learners with early reading difficulties, lower fine-motor control, or attentional variability. By privileging low-friction modalities and clear visual anchors, the SSE suite maintains usability for a diverse range of preschool learners.

3.5. Methodological Alignment with Preschool Pedagogy

It is worth mentioning that the methodological design of the SSE is aligned with the broader pedagogical framework of Greek preschool education, which nowadays emphasizes interdisciplinary, exploratory, and play-based learning [80]. The use of structured play (in games and puzzles), multimodal storytelling (in the eBook), spatial exploration (in 3D applications), and embodied interaction (in XR modules) reflects the core learning domains of early childhood (e.g., cognitive, socio-emotional, motor, and creative development).

Teacher mediation was incorporated as a methodological requirement in all phases. Teachers were encouraged to facilitate transitions between modalities, support comprehension during immersive activities, and help students reflect on their experiences, a fact that is consistent with established practices in inquiry-based learning for young children [81].

3.6. Evaluation Design and Instruments

To examine the feasibility, usability, and experiential value of the SSE suite, a dual-perspective evaluation was designed involving (a) preschool teachers and (b) kindergarten students. This subsection outlines the participants, procedures, and measurement instruments used. Statistical analyses and detailed findings are presented in Section 6. In this design, teacher data were collected via a self-report adoption questionnaire, whereas student data were gathered during in situ classroom interventions with the SSE applications, capturing experiential responses under everyday teaching conditions.

3.6.1. Teacher Evaluation: TAM/TPB-Based Adoption Questionnaire

Fifty-four preschool teachers participated voluntarily in a cross-sectional survey assessing their intention to adopt the SSE suite in classroom practice. The instrument was adapted from established Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [14] and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [15] scales, with item wording contextualized for immersive learning in early-childhood education. Note that the resulting sample of 54 teachers corresponds to the full set of in-service early-childhood educators who both had exposure to the SSE suite and consented to participate. Although not large enough for covariance-based structural modeling, this number is typical for exploratory TAM/TPB applications in early-childhood contexts and adequate for the descriptive and regression analyses reported next.

The administered questionnaire included six latent constructs: Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEU), Attitude Toward Use (ATT), Subjective Norm (SN), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and Behavioral Intention (BI). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Internal consistency for all constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s . At the analysis stage, descriptive statistics were computed for all items, construct interrelations were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients, and multiple regression was applied with BI as the dependent variable and PU, PEU, PBC, ATT, and SN as predictors. More advanced modeling (e.g., confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)) was not pursued due to sample size constraints.

Participation was anonymous and no identifying information was collected. The questionnaire was administered as an online self-report instrument outside the student intervention sessions, without laboratory-style controls or standardized environmental conditions, focusing on teachers’ perceptions rather than behavior in an experimental setting. Evaluation results are reported in Section 6.1.

3.6.2. Student Evaluation: Experiential Questionnaire and Classroom Procedure

Seventy-two kindergarten students (ages 5–6) participated in structured classroom sessions, representing the complete cohort of pupils enrolled in the three collaborating public kindergartens where the interventions took place, involving all components of the SSE suite (multimedia content, mini-games, the interactive eBook, 3D exploration, VR, and AR). The students’ interaction flow with the SSE applications was randomized to minimize order effects, while ensuring consistent exposure and allowing for natural teacher facilitation.

After the activities, students completed an age-appropriate 32-item experiential questionnaire. Items were presented using a child-friendly Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 5) and administered with teacher/researcher assistance to support comprehension without influencing responses. Given the participants’ age, items were also orally presented using standardized phrasing to preserve quantitative consistency.

The questionnaire consisted of:

- General Experience (Q1–Q16), assessing affective response, motivation, usability, and perceived learning.

- Module-Specific Experience (Q17–Q32), evaluating multimedia, mini-games, the interactive eBook, 3D exploration modes, VR, and AR (see Section 5).

No personal or demographic data beyond age group and classroom were collected. Reliability analyses for these item groups (Cronbach’s ) and descriptive findings along with evaluation results are reported in Section 6.2. It is worth noting that, given the age of the participants and the exploratory character of this first deployment, this part of the evaluation was intentionally focused on descriptive and comparative patterns rather than on complex inferential modeling.

4. Design of the Cross-Modal SSE Learning Suite

The methods described above (hybrid ADDIE–FDD development, pedagogically grounded interaction principles, system architecture, and cross-modal orchestration) jointly shaped the SSE applications. The overall design process is also aligned with game motivators and design principles for educational games described in [82].

4.1. Cross-Curricular Framework

For this study, we focused on the “Earth, Planetary System and Space” module in the Greek kindergarten curriculum. Adopting a cross-curricular approach, the module links the broader thematic field of “Child and Exact Sciences” with “Child and Communication”, which includes the “Information and Communication Technologies” sub-module.

Table 4 summarizes the outcomes of bridging these two domains. The core idea lies in the design and creation of an immersive educational game that incorporates VR, AR and gamification mechanics, along with conventional serious video game applications and supplementary digital material, to offer multimodal interaction and multimedium pedagogical content that promotes experiential learning inside and outside the classroom.

Table 4.

Cross-curricular approach adopted in the current study.

Within this framework, SSE provides a structured digital environment in which each technological component directly supports the targeted learning outcomes. VR and 3D exploration foster spatial reasoning and planetary visualization; AR links physical classroom activities with digital augmentation; and multimedia clips, eBooks, and mini-games reinforce factual knowledge and conceptual understanding. The modalities are intentionally aligned with curriculum competencies so that cognitive, perceptual, and exploratory goals are addressed holistically through diversified interaction.

4.2. Game Overview

The SSE aims to provide a holistic educational experience in which kindergarten students actively construct knowledge. Through interaction with an immersive virtual environment that combines multiple media and gamification mechanics, students explore realistic visualizations of key concepts while receiving complementary digital material. Inspired by [54], both training and assessment take place within the virtual environment via mini-tests and mini-games, supporting a playful yet structured learning journey.

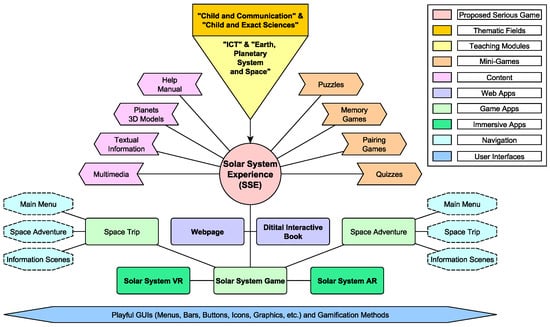

Figure 2 presents a high-level information structure of the SSE. Note that the overall approach is influenced in part by the Theory of Constructivism [6] and grounded in the belief that knowledge should be steadily constructed as part of the educational process itself in order to make the whole experience more productive and contextually meaningful to the students. Therefore, the structure is separated into different parts that employ diversified engagement mediums and may be progressively explored based on the desired learning outcomes.

Figure 2.

High-level visualization of the SSE suite application structure.

To support the developmental characteristics of preschool learners, interaction mechanisms, session duration, sensory load, and narrative pacing were carefully calibrated. VR employs gaze-based controls and limited locomotion to manage cognitive load, while AR relies on simple manipulation metaphors linking digital content to tangible classroom contexts. Multimedia components provide pre-training before immersive exploration, ensuring that each application contributes a clear pedagogical function within the overall learning pathway.

4.3. Game Motivators and Design Principles

As stated, the design strategy applied to SSE to increase the game’s instructional effectiveness is heavily influenced by the educational game design framework discussed in a systematic review of 41 relevant studies [82]. The framework demonstrates a taxonomy of fourteen (14) major game motivator classes that can contribute to motivated engagement in educational games. Table 5 summarizes the motivators and how they are adopted here.

In refining the SSE design, each motivator was applied with explicit consideration of preschool cognitive characteristics, limited reading fluency, and the need for immediate, multimodal feedback. Rather than being added as isolated game features, motivators were explicitly mapped onto instructional goals defined by the cross-curricular framework and ADDIE analysis. In this way, they support learning intention, exploratory behavior, and sustained engagement while promoting conceptual understanding of the Solar System.

These principles shaped both the multimedia components and the transitions between modalities. Coherence and signaling informed the structuring of video segments before mini-games; pre-training guided introductory clips before VR exploration; and segmenting influenced the pacing of tasks within mini-games and eBook interactions. Thus, multimedia principles acted as cross-cutting constraints, ensuring that each component served a clear cognitive purpose within the overall learning flow.

4.4. Gameplay

The ultimate goal of the SSE game is for preschool pupils to learn facts about all planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) in the Solar System. To do so, SSE expands the educational process by using a virtual environment that realistically represents a model of the Solar System. By interacting with the virtual environment, students are able to explore key attributes of the planets such as their conditions (e.g., weather, temperature, wind speed, ground and air composition, oxygen and water levels, gravity), formation, texture, size, and structuring. They can also understand spatial relations among planets, recognizing their relative distance from the Sun and their orbital behavior.

4.5. Multimedia Learning Principles

In parallel, the design incorporates the multimedia learning principles of [57] when creating instructional material for interactive e-learning, with the aim of fostering active and creative engagement (see Table 6).

It is worth mentioning that, besides educational material and textbooks of the Greek educational system, all astronomical information has been retrieved and reproduced in detail from credited scientific sources such as the European Space Agency (ESA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Observatory of Athens (NOA). High-resolution planetary textures (equirectangular projection) are based on NASA’s elevation and imagery datasets. For instance, the textures used for 3D rendering of the planets correspond to high-resolution planetary maps in equirectangular projection of their surface, and are based on NASA’s actual elevation and imagery data libraries.

Table 5.

Game motivators associated with SSE. Adapted from [82].

Table 5.

Game motivators associated with SSE. Adapted from [82].

| Motivator | Definition | Usage Description |

|---|---|---|

| Challenge | Players are presented with tasks that are suitable to their skill level. | All applications are specially tailored for kindergarten students, based on the acquired knowledge and with playful design, high level of replayability, help systems, and no repercussions in case of mistakes or erroneous operations. |

| Competence | Users develop new skills or abilities by completing challenges and reaching goals. | The SSE is created with the aim of sharpening knowledge acquisition, which is immediately reflected within the game world as each piece of new information (e.g., on the planetary system) builds on the knowledge received in previous steps and is evaluated via in-game challenges. |

| Competition | Learners compete with other players (interpersonal) or themselves (intrapersonal), or cooperate (collaborative) towards a common objective. | Though not the main goal of SSE, for each challenge, special game elements such as timers, stars, or progress bars are incorporated to drive students into a positive competitiveness state, but within a safe virtual environment. Students can also form groups and tackle the tasks together. |

| Control | Users are free to influence the game world and its events. | Options are provided to choose the exploration mode and elements are enabled to interact with the visual objects (e.g., enlarge planets). |

| Curiosity | Provide cognitive and sensory experiences that ignite interest for content exploration. | Students are allowed to freely navigate the complete solar system from the cockpit of a spaceship, while the VR and AR apps enable manipulation of the celestial objects via gaze and gestures, respectively. |

| Emotions | Evoke emotions that make the experience memorable and appealing. | UIs are adapted to have a playful design, tasks offer rewards to arouse feelings of accomplishment, VR/AR and gaming properties foster fun and awareness, gamification is used to provide motivation, and meanwhile, great efforts are made to increase engagement in all mediums. |

| Fantasy | Refers to mental images of situations that are not typically found in the real world. | The capability of traveling around the solar system, piloting a spacecraft, and visiting planets, moons, meteorites and the sun triggers the fantasy of the users, while the ability to superimpose the real world with visual augmentations of the celestial objects evokes their imagination. |

| Feedback | Relates to the timely game response to user interaction. | The SSE incorporates various feedback mechanics, including instant dialog boxes, information popup windows, encouraging messages, visual interactive elements, menu tools, progress bars and rewards, etc. |

| Immersion | Reduce user self-awareness and perception of time by increasing concentration and feelings of presence. | The SSE embeds multimodal sensory stimuli, including visual, audio, and haptics, using both conventional and immersive technologies as well as (photo-) realistic solar system representations and conditions to strengthen the sense of “being there”. |

| Novelty | Offer inventive and innovative experiences by combining leading-edge interaction technologies. | The SSE integrates a plethora of state-of-the-art content exploration tools, combining web technologies, video games, multimedia, gamification, VR, and AR. |

| Rules & Goals | Have rules that govern activities and events in the game world and set boundaries, including goals and how to reach them. | Students are given comprehensive instructions for each activity and its goals within the game world; a help manual has been created to provide further assistance, while a website has been developed to offer extra clarifications and information. |

| Real World Relation | Link the real world with the game world to make it relatable to users. | The SSE presents content, interaction, and navigation that directly relates to the real world, e.g., focus gaze on an object to inspect it in VR mode. |

| Social Interaction | Enhance feelings of belongingness and connectedness with others. | The SSE challenges, activities, and tasks can be solved in cooperation with other students and provide recognition upon successful completion that can be shared among them for increased synergism. |

| Usefulness | Adopt a purpose other than plain entertainment and link it to milestones. | The SSE sharpens skill training and understanding in relation to the targeted learning module and makes players aware of its goals with appropriate resources from start to finish. |

Within this environment, specific educational objectives are addressed through playful, easy-to-use graphical user interfaces (GUIs) and supplementary media. Each section introduces a celestial body and is followed by mini-games or challenges that reinforce the content. Gameplay follows a progressive exploration structure: conceptual material is first presented through multimedia and textual/visual hints, followed by guided interaction (e.g., focusing on a planet, activating information windows), and finally by exploratory activities such as VR or 3D spaceship navigation. A help manual is accessible at all times, and the non-linear exploration model allows teachers to flexibly embed SSE into their routines, with high replayability through dynamically generated challenge content.

Table 6.

Multimedia learning principles associated with SSE. Adapted from [57].

Table 6.

Multimedia learning principles associated with SSE. Adapted from [57].

| Principle | Definition | Usage Description |

|---|---|---|

| Coherence | People learn better when extraneous material is excluded; keep the design concise, short, and relevant to the instructional goal. | Succinct help, guidance, and feedback are used throughout the SSE to direct students’ concentration on the actions they should take. |

| Signaling | People learn better when essential material is highlighted. | Important textual or graphics information and interaction tools are highlighted with playful coloring, high contrast, and centralized positioning. |

| Redundancy | People learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics, narration, and onscreen text. | The design avoids concurrent display of on-screen text, audio, and media presenting the same information; videos are preferred when possible. |

| Spatial Contiguity | Corresponding text and graphics should be close to each other. | Informational overlays appear near the planet or object being studied. |

| Temporal Contiguity | Narration and graphics should be presented simultaneously. | Textual elements are paired with simultaneous imagery or audiovisual cues. |

| Segmenting | Lessons presented in user-paced segments enhance learning. | Learning content is broken down into small tasks and missions. |

| Pre-training | Teaching key terms first aids subsequent learning. | Each major activity includes a brief tutorial or video introducing core concepts. |

| Modality | Spoken explanations are superior to text-only formats. | Narrated videos accompany most conceptual explanations. |

| Multimedia | People learn better from words and graphics than words alone. | Text is always coupled with imagery, sound, 3D assets, or animations. |

| Personalization | Conversational style enhances engagement. | Instructions and messages are written in child-friendly, positive phrasing. |

| Voice | Human voice enhances learning. | All sound narration uses recordings by real educators. |

| Embodiment | Human-like movement or gestures aid comprehension. | Demonstration videos use real gestures; VR/AR afford embodied interaction. |

4.6. Game Interaction

Because SSE is designed for preschool-aged users, particular emphasis is placed on lowering interaction complexity and ensuring that all inputs are intuitive, scaffolded, and accompanied by immediate feedback.

4.6.1. User Interface (UI)

The UI elements draw inspiration from children’s existing exposure to playful digital interfaces. In general, regardless of age, users prefer engaging with websites or applications that adopt a similar logic and structuring to what they are already familiar with. For this reason, the UI design—despite its immersive properties and focus on experiential knowledge of the Solar System—is influenced by serious video games for early childhood that already feel familiar to this age group.

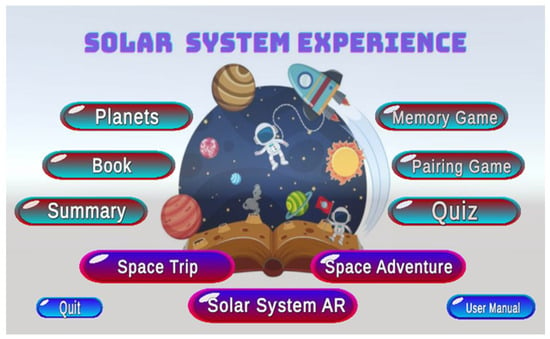

Under this light, the different game screens have been developed with great attention to simplicity and fun design (e.g., see the “Main Menu” scene in Figure 3), with organized and guided steps so the student can easily get acquainted with the various graphical components and their role. Moreover, it provides variety in how information is presented, with continuous positive feedback. While erroneous input may appear (e.g., when the user commences intermediate in-game activities or mini-game missions like quizzes), as is the case in video games in general, any such occurrences are totally reversible with clear indications as to the correct pathway the student must take to complete the given task, making the experience more well-rounded and fulfilling. At the same time, these mistakes in the user’s choices have a constructive and educative nature since they anyway lead back to the corresponding learning material, providing food for thought and requiring critical thinking from the children in order to solve them.

Figure 3.

Main Menu of the SSE.

To reinforce user-friendliness and coherence, interface elements were kept consistent across all modalities (games, VR, AR, interactive eBook). Core interaction elements appear with the same form, font, position, size, and coloring so that moving between media does not require relearning the interface logic.

4.6.2. User Experience (UX)

Regarding UX, the game was designed so that the commands are clear and intuitive and do not present usability problems. Beyond playful styling, the primary goal was to make the game easy to learn so toddlers could use it effectively in educational contexts without risk of information overload. For this reason, any 2D content follows a minimalist design, avoiding unnecessary textual information, with options grouped on the user’s screen according to their content and icons referencing corresponding operations. Within the 3D virtual environments, on the other hand, the screen was limited to graphics necessary for clear navigation or redirection to other useful materials. The aim was to increase the learners’ attention span, allowing them to concentrate on the key aspects of the displayed 3D content without getting constantly distracted.

Still, if for any reason some functionality remains incomprehensible to the students, a “User Manual” button has been added with help instructions (see Figure 4). For instance, in cases where users need assistance in some task they find difficult to perform, through the given guidelines, the teachers, or even the students themselves, can immediately and easily identify what is required of them in order to reach the solution to the problem they are facing.

Figure 4.

Views of the SSE User Manual; currently, supported language is Greek but English translations are planned in future updates. (Left): Guidelines on how to play the SSE games; (Right): Instructions on how to use the AR and VR applications.

Regarding engagement, several interaction patterns, in line with embodied learning principles, promote bodily engagement and improve UX: AR encourages device movement around 3D models, VR uses gaze-based activation for teleportation, and the 3D spacecraft controller enables spatial maneuvering through familiar keyboard mappings. To support diverse classroom devices, loading times, texture resolutions, and UI scaling were systematically optimized, minimizing bugs and display issues, thereby enabling reliable use in typical Greek kindergarten environments where hardware capabilities vary widely [68].

Additionally, the cross-modal sequencing was intentionally designed to accommodate learners with varying levels of motor coordination, attentional control, and emergent literacy skills. Low-specification modalities such as multimedia clips, the interactive eBook, and AR markers require minimal fine-motor skill, while VR and 3D exploration rely on simple gaze-based navigation mechanics or point-and-click interactions. Although SSE does not yet include dedicated accessibility profiles, these multimodal entry points offer flexible interaction pathways that can support diverse learner needs in inclusive settings.

5. The “Solar System Experience” Game Application Suite

All applications of the SSE game have been created using the Unity game engine (available at: https://unity.com/; last accessed: 11 December 2025). Unity was selected because it (i) runs on relatively low-cost hardware, (ii) offers extensive documentation and community support, (iii) provides free plans and an asset store with reusable resources, and (iv) supports multiple platforms, such as PCs, gaming consoles, mobile devices, Web exports and HMDs, as well as interoperability with third-party libraries and SDKs (e.g., Google Cardboard SDK, Vuforia, Mixed Reality ToolKit, Spatial.io). In line with the cross-modal instructional design described earlier, Unity’s cross-platform workflow enabled consistent implementation across modalities (2D, 3D, VR, AR) while preserving pedagogical alignment and a coherent interaction logic throughout the SSE.

Although Unity supports a wide range of targets, the SSE is specifically tailored to desktop-based systems (PCs, laptops) with Windows OS and Android-based mobile devices (smartphones, tablets). This choice ensures that the main game (Space Trip and Space Adventure, jointly termed the Solar System Game) and the immersive mobile applications (Solar System VR and Solar System AR) are compatible with low-cost technologies typically available in Greek schools, which often lack high-end devices due to budget constraints [68]. These systems are also more familiar to inexperienced users and widely available at home, increasing the likelihood that students can revisit the SSE outside school under parental supervision. This design decision aligns with the methodological emphasis on feasibility and ecological validity (Section 3), ensuring that SSE can be deployed under realistic infrastructural constraints. To further broaden access, future builds for additional platforms and language localizations (beyond Greek) are planned.

Besides the downloadable SSE game, an interactive eBook and a public website have been developed to complement and promote the suite. Combined, these components function as interlinked entry points within the cross-modal learning pathway described in Section 4, supporting structured transitions between modalities and progressive knowledge acquisition. The following subsections briefly present each application.

5.1. The Website

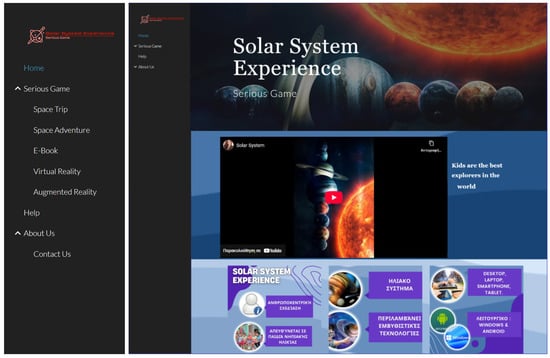

The SSE website (Figure 5), titled “Solar System Experience-Serious Game” (available at: https://sites.google.com/view/solarsystemexperience; last accessed: 13 December 2025), serves as the main public entry point to the suite, providing access to all content and project information. It was developed with Google Sites, a structured wiki-like web authoring tool that enables rapid prototyping without additional software installation. Google Sites is free to build, host and maintain, supports online collaboration among team members, and can be extended by embedding services from Google Workspace (e.g., Maps, Forms) or custom code. The website thus functions as a navigational hub in the SSE ecosystem, enabling consistent access to cross-modal components for both learners and teachers.

Figure 5.

Views of the SSE website. (Left): The navigation menu; (Right): The home page.

The website is structured to provide easy access to:

- Home, offering a general introduction to the SSE game suite and a suggested navigation path across applications.

- Serious Game, listing individual applications, short descriptions, and download links.

- Help, containing documentation on how to install and use the applications.

- About, presenting the goals of the SSE and the development team, along with contact information.

Content is maintained by the development team. In future iterations, a migration to a more robust Content Management System (e.g., WordPress, WIX) is envisaged. Such a CMS upgrade would facilitate multilingual support and improved analytics for monitoring usage patterns and user navigation.

5.2. The Interactive eBook

The interactive eBook was created using standard web technologies (HTML/CSS and JavaScript) to ensure compatibility with mainstream web browsers. It functions as an alternative digital textbook, consolidating Solar System information in textual and audio-visual format (video and images). While it can be used independently, it is designed to integrate with the rest of the SSE components. Besides expository content, it embeds mini-games, additional material that did not fit into the game applications, and direct download links for the VR/AR modules. Importantly, the eBook acts as the “multimedia anchor” of the SSE sequence by providing structured conceptual grounding before learners transition to exploratory 3D, VR, or AR experiences.

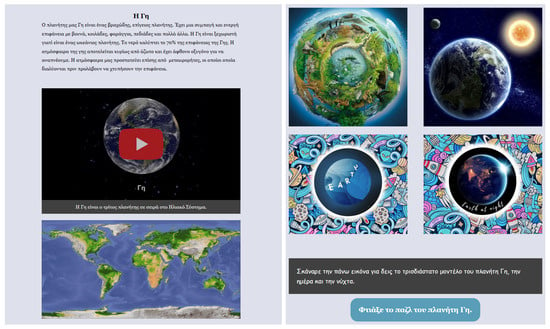

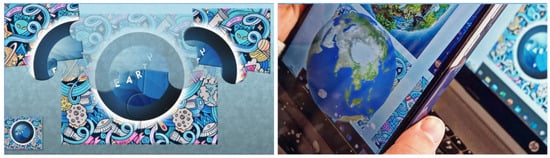

The eBook is organized into sections, one per celestial body, each including a concise textual description and associated video and photographic material. Figure 6 illustrates part of the “Earth” section.

Figure 6.

Information for planet Earth inside the interactive eBook. (Left): Textual information accompanied by video narration and texture analysis; (Right): Photos and custom markers for accessing the “Earth during the day” and “Earth during the night” 3D models in AR mode.

Beyond presenting the planets, the eBook employs gamification to encourage continued engagement [53]. Students can complete small digital mini-games (e.g., puzzles) to win 3D models of planets, which can subsequently be viewed in AR on compatible devices. These reward-based elements link conceptual learning with interactive reinforcement and prepare learners for subsequent XR activities within the broader suite.

A dedicated “Time to Play” section offers two types of activities: (i) visual mini-games (puzzles, memory, pairing) and (ii) simple quizzes (True/False, multiple choice) that consolidate knowledge. These activities were aligned with the cognitive and motivational characteristics of preschoolers, emphasizing short interaction loops, immediate feedback, and low penalty for errors.

Finally, after completing all activities, following standard gamification practices [38], students can unlock an additional section on Pluto. This hidden module acts as a final reward, providing extra information on a dwarf planet that is usually less prominent in introductory Solar System teaching. This optional extension supports differentiated learning pathways, enabling highly motivated learners to deepen their exploration without overloading others.

5.3. The Solar System Game

The Solar System Game is the core 3D experience of the SSE, allowing students to explore a virtual model of the Solar System. It is divided into two scenes: Space Trip and Space Adventure. The former offers a guided tour that gradually introduces celestial bodies in a pedagogically meaningful order, mirroring the sequence used in the interactive eBook. The latter provides a free exploration mode with greater freedom of movement (FOM), similar to modern 3D games. Students can switch between the two modes at any time, though new players are advised to start with the guided tour. This dual-structure reflects the segmenting strategy discussed in Section 4, where structured scaffolding precedes open exploratory learning.

5.3.1. Space Trip Mode

The Space Trip scene (Figure 7) introduces students to the 3D environment and acts as their first “excursion” into space. A realistic depiction of the Solar System is presented, with planets revolving around the Sun and rotating around their axes. The tour starts from the Sun and proceeds through the planets from the inner to the outer Solar System, taking into account that many preschoolers have limited prior experience with 3D navigation.

Figure 7.

Views from the Space Trip scene. (Left): Initial point of entry; (Right): Zooming into a planet (Earth).

Interaction is limited to selecting a celestial body and performing point-and-click actions to open informational pop-up windows. All interactive elements are implemented as event triggers in C#. Popup windows and interaction hotspots follow spatial and temporal contiguity principles so that inspection and textual information appear together, supporting immediate conceptual linking for young learners. The scene is deliberately designed as a gentle first contact with the environment to minimize insecurity and encourage students to continue to the more demanding Space Adventure scene. In this sense, Space Trip functions as a cognitive and interactional “warm-up” that lowers initial barriers for children with limited familiarity with digital games or 3D environments.

On top of this, the use of single-action point-and-click selection, fixed camera paths, and predictable object behavior was intended to support children with emerging motor coordination or attentional difficulties. By avoiding multi-step interaction sequences and rapid input timing, Space Trip maintains low motor demands while preserving a sense of agency.

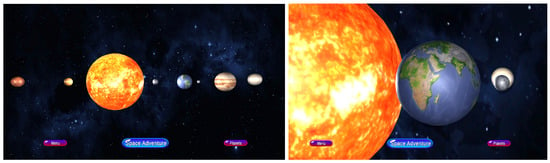

5.3.2. Space Adventure Mode

In Space Adventure (Figure 8), students pilot a 3D spacecraft around the Solar System in third-person perspective (3PP). The spacecraft acts as a controller and visible avatar, allowing students to approach celestial bodies and inspect them from different angles. Prior studies report no major differences in spatial presence between 3PP and first-person perspective (1PP) [83]; here, 3PP was preferred because it also introduces students to basic aerospace concepts and rocket science.

Figure 8.

Views from the Space Adventure scene. (Left): Initial point of entry; (Right): close-up view of Saturn.

Movement is controlled via the keyboard (right/left, up/down, forward), without backward motion to maintain consistency with real-world aircraft and spacecraft movement. Additional horizontal maneuvers facilitate better positioning around planets. This relatively restricted movement scheme serves an additional purpose: it limits the need for simultaneous key combinations, reducing motor complexity and supporting learners who may struggle with coordinating multiple directional inputs.

Besides navigation, interaction is again performed by aiming at points of interest (POIs) and clicking to retrieve information. This is intentional in order to match various preschool motor and cognitive profiles, offering minimal controls, predictable motion, and persistent visual anchors that support ease of use without overwhelming the learner.

Overall, the Space Trip and Space Adventure modes form complementary components within the cross-modal sequence. The former strengthens conceptual clarity via guided visualizations, while the latter fosters curiosity, autonomy, and exploratory behavior. Together, they offer a structured yet flexible learning pathway that accommodates diverse learner profiles.

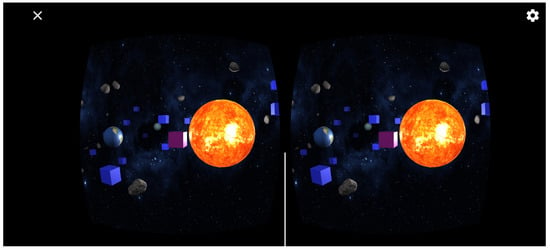

5.4. Solar System VR

“Solar System VR” is designed for stereoscopic projection and focused on placing students “inside” the 3D Solar System model. It thereby extends the visual–spatial learning afforded by desktop applications into a fully embodied environment.

The VR app targets Android devices and was developed using the Google Cardboard (developer page: https://developers.google.com/cardboard; last accessed: 12 December 2025). XR Plugin for Unity (SDK available at: https://github.com/googlevr/cardboard-xr-plugin; last accessed: 12 December 2025), a software development kit (SDK) that supports motion tracking, stereoscopic rendering, and input via viewer buttons. It can be used with cardboard-like viewers or other mobile-based HMDs. This low-cost configuration follows the design principle of technological frugality, making VR feasible in typical Greek preschool classrooms.

These hardware conditions directly influenced the interaction model, as IMU-based head tracking and limited processing power made continuous locomotion or controller-based schemes impractical. Consequently, gaze-triggered dwell activation was adopted as a stable, low-overhead technique that minimizes fine-motor demands and reduces usability frictions under low-cost constraints. In parallel, simplified shaders and reduced scene complexity were employed to maintain frame-rate stability across heterogeneous devices.

To further support access, a “Manufacturer Kit” is provided, including technical specifications and drawings for lenses, conductive strips, and casing patterns so that schools or families can build their own cardboard headsets from simple materials (cardboard, lenses, magnets, rubber bands). This hands-on construction activity reinforces constructivism principles [6] and strengthens students’ sense of ownership over their tools.

The VR scene is rendered in first-person perspective (1PP) using stereoscopic imaging: separate views are presented to each eye, and the brain combines them into a single 3D percept via stereopsis [84]. Planets revolve around the Sun and rotate around their axes, as in the 3D desktop applications.

To simplify space exploration and accommodate young learners’ attentional span, motor coordination, and head–body stability, navigation is based on teleportation to POIs represented as cubes discreetly placed around celestial bodies. The system tracks head movement and uses gaze-based activation. In detail, students must focus the center of their vision on a cube for three seconds to trigger teleportation, implemented in C# via ray casting. This minimalist gaze-based interaction avoids reliance on handheld controllers and reduces motor and cognitive demands, supporting predictable navigation in the stereoscopic environment while still promoting active discovery.

During the dwell period, the cube gradually changes from deep blue to bright red, indicating activation (Figure 9). When the timer elapses, the user is transported to the new location, gaining a different vantage point of the Solar System. This simple mapping between visual focus and system response makes interaction easy to learn. A dedicated tutorial section in the help manual guides students and teachers in using VR safely and effectively.

Figure 9.

View of the Solar System mobile VR environment during a gaze-triggered teleportation operation.