Abstract

Following the Itaewon Halloween Crowd Crush of 29 October 2022, this study examines how public sentiment evolved on Naver, South Korea’s most influential digital platform. While prior research has focused on mainstream media and global social networks, little is known about localized discourse on Naver. To address this gap, we analyzed 2107 user-generated posts collected via Python-based web scraping across three time periods: the immediate aftermath, first anniversary, and passage of the Itaewon Special Law. Semantic network analysis, sentiment classification, and logistic regression were applied to uncover patterns in discourse and emotional tone. Results reveal a shift from grief and outrage in 2022 to demands for political accountability, safety reform, and memorialization by 2024. High-frequency keywords reflected media and government narratives, while low-frequency terms exposed grassroots voices and emotional nuance. Regression analysis confirmed statistically significant associations between sentiment, title length, and year. These findings suggest that digital platforms not only mirror public sentiment but also shape the emotional and political framing of national tragedies. By tracing sentiment over time, this study contributes to understanding how echo chambers, narrative framing, and temporal context interact in shaping collective responses to crisis.

1. Introduction

1.1. Halloween in Itaewon, Crowd Crush, and Public Response

Like many nations, South Korea observes various holidays and cultural events throughout the year. Among them, Halloween has gained popularity in Seoul’s multicultural district of Itaewon, owing to its international character, proximity to the U.S. military base, and sizable foreign resident population [1,2]. On 29 October 2022, this annual celebration turned catastrophic with the Itaewon crowd crush, resulting in the deaths of over 150 people [3,4]. This tragic event underscores the urgency of understanding how digital communication platforms mediate public response during collective trauma.

Public discourse following the crowd crush was shaped not only by mainstream media but also by online platforms that enable real-time emotional expression, demands for accountability, and collective sense-making. While previous studies have examined media framing and social media reactions [5], the role of Naver, Soth Korea’s main portal for news, blogs, forums, and user commentary, remains underexplored.

This study addresses that gap by analyzing sentiment and discourse patterns on Naver, focusing on how emotions evolved, and which narratives gained prominence over time. By examining the public’s response across three key periods, the immediate aftermath, the first anniversary, and the legislative response, this research demonstrates how sentiment reflects and reinforces collective identity, accountability claims, and platform-driven echo chambers. In doing so, it contributes to crisis communication scholarship by highlighting how digital ecosystems shape emotional and political discourse after large scale tragedies.

1.2. Crowd Crush Analysis in Other Countries

Effective communication is widely recognized as a cornerstone of disaster response and community resilience. Scholars argue that crisis communication networks should extend beyond official institutions to include citizen groups and grassroots participation [6]. During such events, individuals increasingly turn to digital platforms to seek information emotional expression, and collective organization, with online news and social media playing central roles [7].

The rise of Web 2.0 and internet social networking (ISN) has further transformed this information ecosystem, as search engines, social media platforms, and microblogging services provide crucial venues for both information retrieval and peer-to-peer exchange [8]. Researchers have used sentiment analysis to assess emotional responses in crowd disasters globally, such as the 2022 Indonesian soccer stadium stampede, where fear and outrage dominated online discourse [9], and the 2014 Shanghai’s New Year’s Eve crush, which also saw surges in negative sentiment [10].

Beyond retrospective analysis, predictive approaches have been proposed, such as leveraging map query data to forecast potential crowd disasters [11]. Complementary methods highlight the value of sentiment classification lexicons for improving situational awareness and supporting more effective crisis communication [12].

In addition to sentiment trends, digital infrastructures shape communication dynamics by distributing influence unevenly. For instance, a study of the #MarchForOurLives campaigned showed that a small number of “core advocates” generated agenda-setting messages, while most users functioned as amplifiers, circulating these messages at scale [13]. Taken together, these studies highlight the value of integrating sentiment analysis with network-based approaches to understand how public discourse, influence, and emotional response converge during crises.

1.3. Understanding Echo Chambers

South Korea’s highly digitized society, with one of the world’s fastest internet infrastructures, has made platforms like Naver central to everyday information access and civic discourse. As the country’s leading search engine and portal [14], Naver integrates news, blogs, forums (Cafes), and Q&A communities (Knowledge iN), creating a comprehensive platform for both top-down information dissemination and bottom-up dialog [15,16,17,18,19]. Compared to microblogging platforms like Twitter, Naver supports longer, more deliberate forms of engagement, making it uniquely positioned for capturing how users process collective topics, interests, communities, and opinions. This enables more complex and prolonged conversations than platforms with brief updates [20].

At the same time, Naver’s integrated structure and recommendation algorithms raise the potential for echo chamber formation, environments where users are repeatedly exposed to similar opinions, reinforcing bias and emotional intensification [21]. This dynamic is particularly relevant during crises like the Itaewon crowd crush, where emotionally charged discourse can harden into polarized or exclusionary narratives.

Recent studies emphasize the importance of social media sentiment analysis and echo chambers during emergencies, particularly for informing effective crisis communication strategies. Echo chambers can distort public understanding, leading to bias and reduced communication efficacy, especially in ideologically aligned communities [22]. Researchers advocate for the integration of topology-based measures with semantic analysis of community opinions, utilizing aspect-based sentiment analysis and consensus metrics to assess polarization and message diffusion [23]. Sentiment tracking also enhances situational awareness by capturing emotional shifts and training patterns in real time [24]. The semantic evolution of user behavior during disasters often reflects rapid conformity and alignment, shaped by social ties embedded in digital networks [25]. Understanding the dynamics of echo chambers and sentiments within Naver is essential for analyzing public sentiment and community responses in this interconnected digital arena.

1.4. The Relationship Between Public Sentiment and Echo Chambers

Echo chambers in social networks refer to closed systems where users are predominantly exposed to beliefs, opinions, and information that reinforce their existing views, resulting in amplification of shared attitudes and the marginalization of opposing perspectives [26]. These environments arise from three mechanisms: selective exposure, in which users preferentially engage with like-minded content [27]; algorithmic filtering that personalizes and reinforces existing preference [28]; and social reinforcement, through which group-based interactions further consolidate beliefs and intensity polarization [29]. Together these processes limit access to diverse viewpoints and foster ideological homogeneity within digital discourse.

Understanding both public sentiment and echo chambers is critical, as these elements are deeply interconnected in shaping discourse during national crises. In the context of catastrophe communication, this study draws on appraisal theory, echo chamber theory, and social identity theory. Psychological constructs such as social identity influence risk perception and individual readiness to respond [30]. Social identity theory also explains how self-conception and cognition affect group dynamics and intergroup connections [31].

These theoretical perspectives intersect with research on sentiment and discourse in digital environments. Studies show that information spreads rapidly on platforms like Twitter (now X), where bots contribute to opinion polarization [32]. Echo chambers are further amplified by algorithms that exploit users’ emotions and biases, prioritizing emotionally charged content and reinforcing cognitive biases.

From an appraisal theory standpoint, combining network topology with semantic analysis enables a more granular understanding of how emotionally driven narratives evolve. Techniques such as aspect-based sentiment analysis and consensus group metrics are valuable for mapping these dynamics. Social identity theory highlights the role of strategic communication and the influence of opinion leaders in facilitating information flow during crisis contexts [33]. Together, these studies show that psychological, social, and communication factors play a complex role in disaster situations like this to reveal the cohesiveness of the digital community and their beliefs [34].

The Itaewon incident illustrates how public attitudes on social media—especially on Naver—were increasingly influenced by echo chamber dynamics, intensifying public opinion like the events of the Sewol ferry disaster. The online platform enables users to express emotion, demand accountability, and circulate critical information—particularly among those near the event [35]. The themes and narratives that surfaced on Naver reflect a cyclical structure shaped by the platform’s design and user behaviors. Factors such as motivation, expertise, and participation level influence the content being produced and shared. Hyperlinks within user comments provide vital insights into public perception and allow users to connect with and build upon existing material [36]. These links also serve as social cues, reflecting offline relationships and shaping online interaction dynamics [37]. While often driven by entertainment and consumer activity, Naver’s trending search data can surface collective anxieties and concerns during national emergencies [38].

This cyclical nature, where user behavior and platform architecture mutually reinforce one another, reflects how algorithmic features surface emotionally resonant or high-engagement content, which then shapes user responses and amplifies dominant narratives. As users engage with this content, platforms further optimize for those behaviors, deepening the feedback loops [39,40]. Thus, examining both platform dynamics and user-generated content is essential for a comprehensive understanding of public discourse in South Korea, offering critical insights for crisis management, policymaking, and the formulation of effective communication strategies in future emergencies [41].

Building on prior research regarding social media’s role in shaping public mood after traumatic events [42], this study contributes by integrating sentiment analysis with an examination of echo chamber formation on Naver. Most existing studies have treated these components separately, either analyzing echo chamber dynamics or focusing on platform-specific discourse. This research bridges that gap by examining how emotional patters and discursive clustering evolved concurrently following the Itaewon crowd crush. By analyzing online content, the research seeks to gain insights into the evolving public sentiment, and the role echo chambers play in shaping opinions and areas of concern following the incident.

This study contributes to the literature in two keyways. First, it offers a dual-layered approach by integrating sentiment analysis with semantic network methods, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of public discourse in the aftermath of the Itaewon crowd crush. While prior research has often isolated either echo chamber dynamics or platform-specific sentiment trends, this bridges the two by mapping how emotionally charged narratives co-evolve within echo chamber structures on Naver. Second, by focusing on Naber, South Korea’s dominant digital platform with a unique blend of search, blog, and forum features, this study extends disaster communication research beyond Western-centric platforms like Twitter. The methodological innovation lies in capturing both the structure and content of discourse, offering deeper insights into how digital publics form, reinforce, and contest narratives during national trauma.

Utilizing semantic and sentiment analysis, this study will identify and explore emerging themes and topics within public dialog on Naver. The research is guided by the following key questions:

- Echo Chambers and Public Sentiment: How did echo chamber dynamics on Naver influence public sentiment and opinions regarding the Itaewon Halloween crowd crush incident?

- Key Topics and Public Concerns: What were the primary themes and areas of public concern identified through data analysis on Naver in the aftermath of the incident?

- Sentiment Shifts Over Time: How did the sentiment on Naver evolve during and after the Itaewon tragedy, and what role did echo chambers play in shaping these shifts.

Beyond addressing these research questions, this study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it addresses the empirical problem of how emotional polarity and discourse structures co-evolve within digital eco chambers during crisis communication, a dimension overlooked when these phenomena are examined separately. To solve this, the study applies an integrated analytical model combining semantic network analysis and sentiment classification to capture how emotional tone and information structures reinforce one another. The model is evaluated using user-generated comments from Naver, South Korea’s largest news and community porta, collected during the aftermath of the Itaewon crowd crush. These data represent emotionally charged, real-time discourse shaped by algorithmic visibility and user participation. Second, the study offers a local, platform-specific perspective by analyzing Naver, which remains underexplored in crisis communication research. Third, it links theories to explain how emotion, selective exposure, and group identity shape collective meaning-making during national crises.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection, Analysis Processes and Methods

Just like the web, the goal of Naver is to disseminate information about South Korea and actively serve as an information hub. The web is an abundant source of big data, including native digital traces from search engines and social media sites [43]. Web-based data span digital books, libraries, research articles, blogs, news, personal viewpoints, and online discussions, all of which can be analyzed to quantify social phenomena using diverse methodologies [44]. These types of data, especially from online interactions, provide valuable insights into human nature and collective communication dynamics [45].

Many studies have examined public discourse on various platforms using web analysis, often applying Python-based techniques for tasks such as extracting emotional data or classifying comment content; this research extends those approaches by combining sentiment and semantic analysis in an integrated design [46,47].

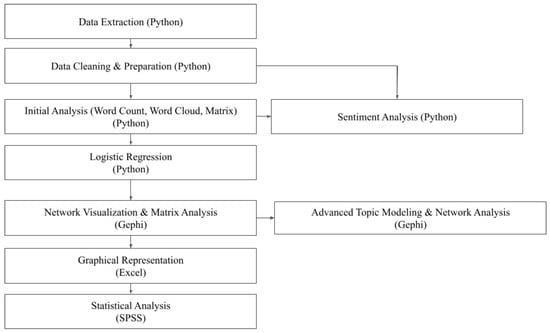

Figure 1 shows the research process for this study. Data collection began with Python-based scraping of publicly available content from Naver. To ensure precision and relevance, we conducted a multi-stage keyword testing process. Approximately 12 initial keyword combinations were generated by combining event-related and location-specific terms (e.g., “Itaewon Halloween”, “Itaewon Incident”, “Halloween Tragedy”, and “Seoul Crowd Crush”). Each combination was evaluated using Python scripts that returned sample outputs, which were manually inspected to assess contextual relevance, noise level, and topical focus. Many of these early keywords retrieved content unrelated to the Itaewon crowd crush, such as other Halloween festivities or other entertainment news, indicating low semantic precision.

Figure 1.

Process flowchart for semantic and sentiment analysis.

Based on this, a second round of testing incorporated Boolean operators and quotation marks (“ ”, +) to improve context capture. Quotation marks were used to retrieve exact phrases, while the plus sign ensured that all linked terms were included in the search query. During validation, sample queries such as Itaewon + Crowd + Accident and other Korean terms were cross-checked against trending search results and top-linked Naver articles to confirm topical relevance. These tests showed that “Itaewon Disaster” and “Itaewon Crush Accident” consistently produced posts and comments directly related to the 2022 crowd crush, confirming their contextual precision and minimizing off-topic retrievals.

Data were then collected across all accessible Naver verticals to ensure comprehensive coverage of public discourse. For each entry, metadata such as titles, timestamps, main text, and user comments were extracted while adhering to ethical standards for web-based research. Three collection windows were defined to capture temporal shifts in sentiment and attention:

- From 29 October 2022 (Incident Date) to 30 November 2022: This period captures initial reactions and discussions immediately following the tragedy.

- From 29 October 2023 (First Anniversary) to 11 November 2023: This timeframe examines online discourse surrounding the first anniversary of the incident.

- From 1 January 2024 to 10 May 2024 (Passage of Special Law): This period explores public sentiment leading up to and following the passage of the Special Law related to the Itaewon tragedy.

Following extraction, all scripts were developed and executed in PyCharm Community Edition 2023.2 on macOS, using Python 3.11 with several scripts (e.g., KoNLPy, pandas 2.1, numpy 1.26, scikit-learn 1.3) to merge, de-duplicate, and normalize the dataset. Posts and comments were sorted by date, relevance, and engagement level. Text preprocessing included tokenization, stop-word removal, and morphological analysis using the Komoran module in KoNLPy, which performs part-of-speech tagging, optimized for Korean-language text. This ensured linguistic precision by accurately identifying nouns, modifiers, and key terms essential for semantic interpretation. For topic categorization, a semi-supervised approach was employed. High-frequency keywords were manually grouped into thematic clusters and validated through iterative refinement and cross-checking against top-performing posts. Preliminary measures such as daily post volume and average sentiment per topic were computed to trace temporal discourse trends before deeper analysis.

The study employs a Python–Gephi hybrid analytical framework to integrate structural and affective analyses. In Python, word co-occurrence matrices were generated to map relationships among key terms, which were then visualized and clustered in Gephi to reveal the semantic structure of discussions. This enabled identification of high- and low-frequency keyword groups and their interconnections within emerging narratives. Parallel to this, Python-based sentiment analysis classified emotional polarity (positive, neutral, negative) using rule-based lexicons and logistic regression to test associations between sentiment, engagement, and temporal patterns. Together, these methods provide a reproducible, data-driven model for understanding how emotional tone and information structure co-evolve in echo chambers during crises. While enhancing interpretative precision, this approach is limited to publicly accessible Naver data, which may constrain cross-platform generalizability.

2.2. Semantic and Sentiment Analysis

Building upon this framework, the analyses were designed to examine how structural and emotional patterns jointly shape discourse within Naver’s echo chambers. Semantic Network Analysis, a meaning-centered network technique that examines textual relationships through word co-occurrence [48] was used to identify dominant narratives and how they clustered around key terms. This approach is particularly suited to exploring echo chambers, as it reveals how ideational proximity and repetitive framing reinforce shared group perspectives. Edges were retained in the semantic co-occurrence network if word pairs appeared together at least twice across documents (co-occurrence threshold = 2), ensuring that only stable lexical associations were visualized.

The final dataset consisted of 2107 entries derived from the optimized keywords “Itaewon Tragedy”, yielding 1674 entries, and “Itaewon Crush Accident”, resulting in 433 entries, reduced from initial totals of 19,750 and 4666 after cleaning. Using Python, we performed word counts, generated word clouds, and built co-occurrence matrices to map lexical relationships and thematic proximities. These matrices were visualized with the help of Gephi version 0.9.7 “http://gephi.org/” (accessed on 23 July 2024) [49], whose spatialization and clustering capabilities enabled the identification of core themes and interpretative communities [50,51,52].

Topic detection followed, through a combination of algorithmic and manual grouping. High- and low-frequency keywords were compared against raw content to ensure contextual accuracy, allowing for precise interpretation of thematic clusters and their evolution across time.

Complementing this, sentiment analysis was employed to capture the affective dimensions of public discourse [53,54]. This method uses computational and linguistic principles [55] to detect positive, negative, and neutral tones within posts and comments. Comparing sentiment shifts across collection periods revealed how emotional responses changed from immediate crisis reactions to later reflection [56]. Logistic regression provided a statistical perspective on relationships between sentiment polarity, publication timing, and engagement level, supporting a quantitative understanding of emotional evolution within Naver echo chambers. These analyses operationalize the link between emotion, discourse structure, and digital behavior, offering a multidimensional understanding of how collective sentiment and ideological clustering interact during national crises.

3. Results

3.1. Understanding Linguistic Patterns and Echo Chambers in Naver

Research literature topic detection can be performed using machine learning and expert assessment. Automated keyword clustering can evaluate big text corpora and produce impartial and uniform results [57]. This can be complemented by manual qualitative analysis to help identify current issues and future trends [58].

Large quantities of text, especially bibliometric networks of scientific literature references, can reflect research discipline progression through collaboration and citations, public attitude, and strategic decision-making in tackling complex social issues. This research analyzed linguistic patterns and communication dynamics using these methods [59]. The examination of Naver material relating to the “Itaewon Tragedy” and “Itaewon Crush Incident” reveals an intriguing insight.

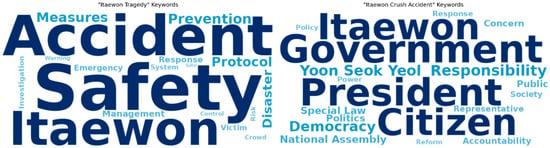

Word clouds, providing versatile visualizations of word analysis, were conducted to support various analytical tasks [60,61]. Figure 2 effectively summarizes the co-occurring words. On the left, we clearly see that conversations around this topic focus on safety in relation to accident. Most of the content from Naver discussed the safety protocols that did not happen and preventive measures that should have been put in place, which is associated with the Itaewon accident. On the contrary, the one on the right focuses on the impact of the citizens. Most of the contents highlights the public concern and discourse around the government, especially the president, clearly stating that there is significant societal and political dimension to it.

Figure 2.

“Itaewon Tragedy” (left) and “Itaewon Crush Incident” (right) keywords word cloud.

Authoritative discourses and grassroots voices generated echo chambers that magnified some narratives and marginalized others, shaping public opinion through asymmetric influence structures observable in digital communication [62]. Such dynamics mirror patterns of digital resistance, where online discourse actively constructs polarization and “otherness”, positioning groups in opposition and reinforcing divides during moments of crisis. To further analyze the texts, we examined high-frequency keywords, which are ubiquitous in language and prevalent in institutional influence like mainstream media [63], reflecting formal communication and standardized terminology used by authoritative bodies or organizations. Based on their distinctiveness, low-frequency word analysis reveals a particular narrative that informs individual expression and peer-to-peer discourse. Slang, colloquialisms, and domain-specific jargon may illuminate personal communication styles and community dynamics [64].

As we analyzed the raw data behind every keyword seen in Table 1, results show that search queries “Itaewon tragedy” and “ Itaewon crush accident” reveal distinct patterns that reflect the content’s origin and nature; content linked to high-frequency keywords predominantly stems from media outlets and governmental outlets.

Table 1.

Word frequencies (high and low).

News articles and governmental remarks emphasize public safety, government accountability, and the disaster’s social consequences [65]. Tragic events, public safety, responsibility, and governance failings dominate narratives. TBS Seoul https://tbs.seoul.kr/tv/index.do (accessed on 23 December 2024) and Ilgan Sports https://isplus.com/ (accessed on 23 December 2024), among others, provide most of the content, but other regions contribute. Despite subtle differences in opinion about the incident and its aftermath, media coverage emphasizes accurate reporting and analysis, driving public reaction.

Low-frequency keywords like “military police”, “judicial examination”, and “liberalism” frequently appear in personal, opinionated debates on social media, local media, and personal sites. These terms reveal hidden public discourse outside dominant narratives through colloquial expressions or personal viewpoints. A year after the catastrophe, forums like Ppomppu debate the military presence in Itaewon and political response, unlike high-frequency material. Low-frequency terms show critical and supporting reactions to political and social measures, such as law enforcement efforts and Samsung’s donations to impacted individuals. High-frequency words influence society and official discourse, while low-frequency keywords capture nuanced, critical views from public contributors.

3.2. Emerging Themes and Echo Chambers

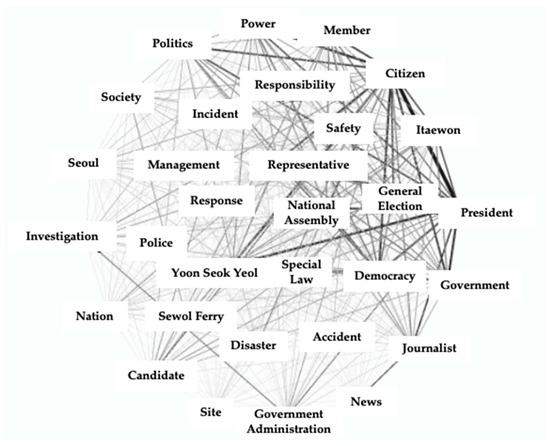

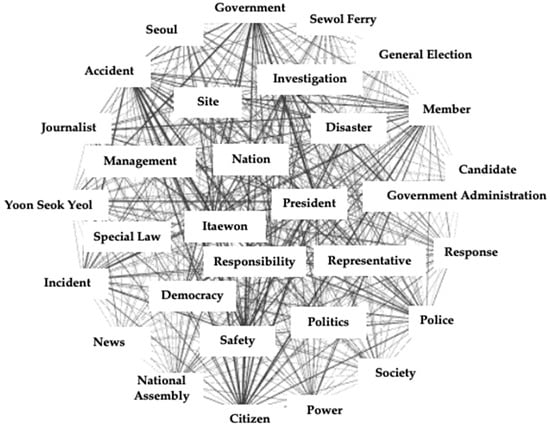

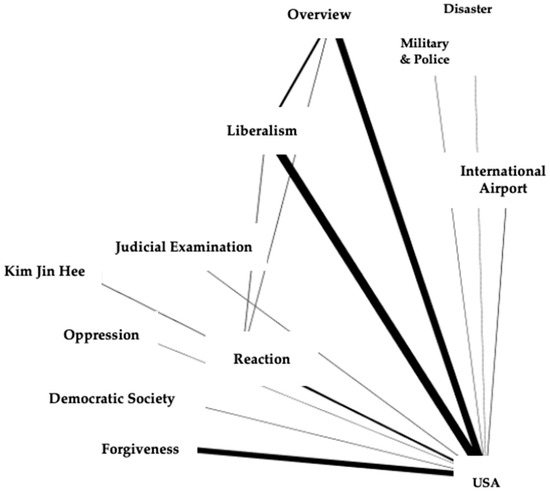

Visualization maps in Figure 3 and Figure 4 show high-frequency word pairings, while Figure 5 shows low-frequency word pairing keywords. Each word pairing reveals significant themes and relationships, creating separate sets. Disaster and safety, accountability and governance, and public reaction and media coverage are frequently visualized. In contrast, low-frequency word pairings cover international relations and ideology, disaster response and safety standards, societal support, and emotional responses.

Figure 3.

Word pairing keywords—Itaewon tragedy high-frequency keywords.

Figure 4.

Word pairing keywords—Itaewon crush accident high-frequency keywords.

Figure 5.

Word pairing keywords—Itaewon tragedy and Itaewon crush accident low-frequency keywords.

In semantic network visualizations (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), nodes represent keywords extracted from the Naver dataset. Edges (connecting lines) represent co-occurrence relationships indicating that two terms appeared together within the same content. Edge thickness reflects the frequency of co-occurrence; thicker lines indicate that two keywords appeared together more frequently across corpus. The spatial layout was generated using Gephi’s ForceAtlas2 algorithm, which positions frequently co-occurring terms closer together based on their relational strength. Dense overlapping of edges, particularly visible in the central regions of Figure 3 and Figure 4, indicates semantic convergence zones where multiple keywords are highly interconnected, revealing how institutional and political terms form tightly clustered discourse patterns. In contrast, Figure 5’s sparse structure with minimal edge overlap demonstrates the fragmented nature of low-frequency discourse, where alternative perspectives remain less interconnected.

Public discourse may generate echo chambers due to these variances. High-frequency content reinforces official, factual narratives on public safety and accountability. Low-frequency content creates echo chambers for various and individualized perspectives, reflecting divergent views and deeper emotional responses, making the occurrence and its repercussions more complex and essential.

We can see in the figures that high-frequency keyword pairing is strongly related to the president, citizens, Yoon Seok Yeol, and the government. These combinations show how political leadership and public involvement in South Korea are intertwined. During major events like this Itaewon disaster, the media highlight in their content that citizens want transparency, responsibility, and a decisive response from their leaders. Their voices and government replies are amplified and explained by the media, shaping government and public discourse. This shows that the political environment and social undercurrents driving media coverage and civilian expectation underpin contemporary South Korea political discussion. Other high-frequency pairings also included the Sewol ferry, the government, and power; these are related to contents that highlight the power issue practiced by the government and media that also happened during the Sewol ferry incident, prompting discussions of it happening again in the Itaewon incident.

On the contrary, low-frequency keywords focused on public discourse on domestic issues, where some discussed nuanced views of international and ideological circumstances. Also, forgiveness and reaction keywords reflect changing social attitudes on accountability, healing, and crisis response. Most of the low-frequency keywords are more personal to the feelings of the content author.

In summary, this analysis supports the communication patterns and linguistic dynamics showing that high-frequency keywords heavily focus on government leadership, political accountability, and the media’s role in disaster reporting and information dissemination, making high-frequency words more inclined to mass targeting of communication following common themes and words that are palatable to many. Contradictory to high-frequency results, low-frequency results show themes and topics focused on personal opinions, recognition of individual voices, and societal reactions, and this is where most emotions are more visible such as anguish, frustration, etc.

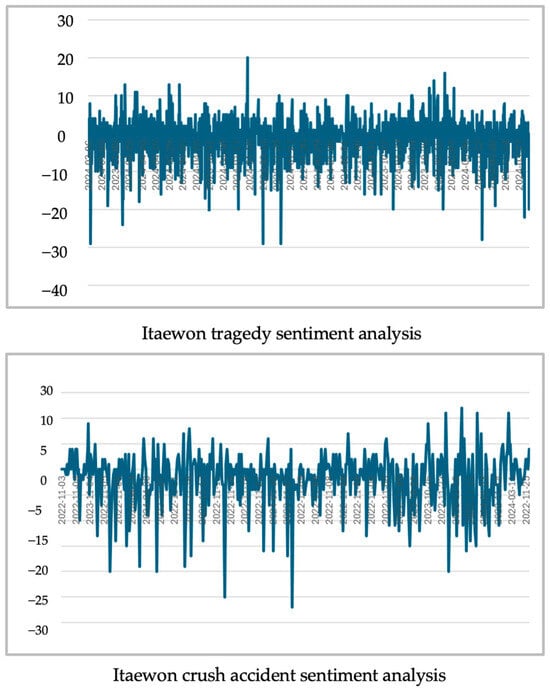

3.3. Analyzing Public Sentiments

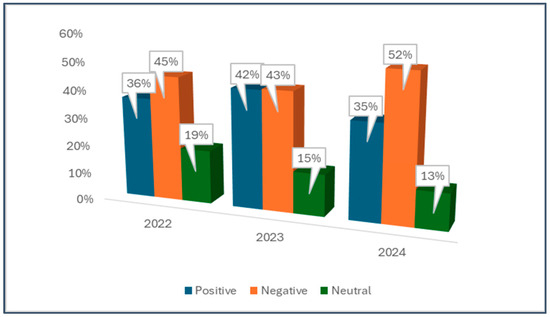

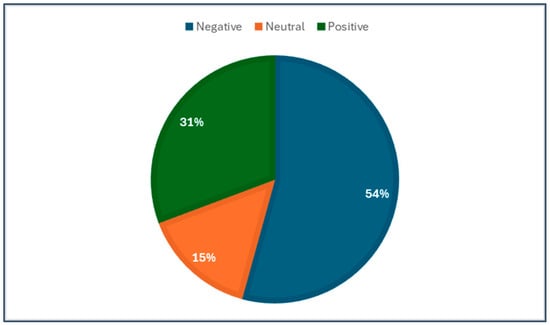

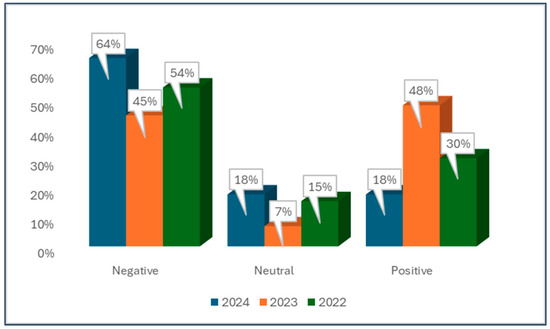

The 2105 titles referenced in Figure 6 show a three-year trend marked by volatility in public sentiment, with frequent peaks and troughs that reveal not only fluctuating emotional reactions but also shifting public concerns. These oscillations suggest that sentiment was not static but responsive to political, legal, and social developments related to the Itaewon tragedy. The “Itaewon Tragedy” dataset generated a predominantly negative trajectory that intensified in 2024, reflecting how the label itself kept the discourse tied to unresolved grief and demands for accountability. By contrast, the “Itaewon Crush Accident” dataset demonstrated a decline in negative sentiment, indicating that framing the incident in more technical and procedural terms allowed the public to focus on systemic reforms and recovery measures rather than prolonged mourning. This divergence suggests how naming and framing influence not only the tone of discourse but also the trajectory of collective emotional processing.

Figure 6.

Three-year trend and fluctuation analysis of sentiments.

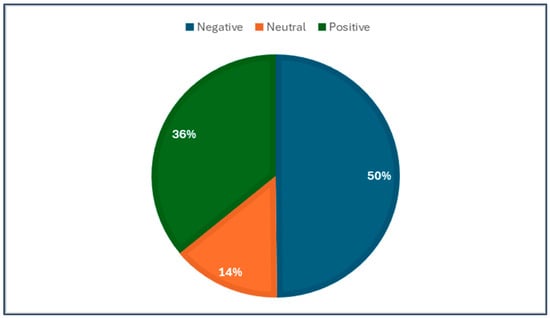

Sentiment analyses are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. Negative sentiments dominated much of the discourse and appeared to reveal more than emotional reactions. They likely point to erosion of trust, institutional vulnerability, and collective trauma. For example, “Chief Hwang Sang-mu Resigns Amid Controversy Over Remarks on Journalists and Concern for Upcoming Elections” illustrates how political resignations did not merely evoke fear and anxiety but likely symbolized instability in governance and heightened perceptions of systemic fragility. Similarly, “Strategies for Addressing Trauma Among Organizational Members” signals that distress extended beyond immediate victims to organizational and social levels, suggesting that the tragedy’s ripple effects on collective psychological stability were significant. Titles such as “Two-year turmoil resulting from Presidential Election Disputes” further channeled anger and frustration, not only documenting unrest but also likely reflecting unresolved conflicts that reinforced the sense of crises. During the first wave of COVID-19 in Greece, sentiment analysis of Twitter data similarly documented volatile shifts across anger, fear, sadness, and disgust, indicating that crises tend to generate turbulent emotional landscapes that both reflect and reshape public resilience [66].

Figure 7.

“Itaewon Tragedy” sentiment breakdown—all years.

Figure 8.

“Itaewon Tragedy” sentiment breakdown—year by year.

Figure 9.

“Itaewon Crush Accident” sentiment breakdown—all years.

Figure 10.

“Itaewon Crush Accident” sentiment breakdown—year by year.

Neutral sentiments, while less emotionally charged, provided informational anchors within emotionally saturated discourse. Titles such as “Safety Apathy: Is there a sense of safety?” and “Official Election Campaign for Regional Constituencies in the Upcoming General Election; Rally with Microphone Scheduled for Tomorrow” reflect a factual tone that appears disengaged from emotion. However, their presence may suggest more than indifference. These titles likely stabilized the discursive environment by presenting socio-political developments in procedural terms, allowing the public to refocus on information rather than emotion. Comparable large-scale computational studies reinforce this interpretation, as neutral sentiment has been shown to display greater consistency and detectability than other categories, suggesting that neutrality itself functions as an organized and stabilizing layer of public discourse rather than a residual or insignificant category [67].

Positive sentiments, though less frequent, appeared to offer glimpses of resilience, optimism, and collective adaptation. Titles such as “Establishment of Memorial Space for the Victims of the Itaewon Tragedy at Their Alma Mater” highlight how grief was transformed into commemoration, suggesting that society was able to honor memory while fostering healing. Other directly referenced institutional reform such as “Bipartisan Agreement Reaches Passage of the Itaewon Special Law in the National Assembly Following the Tragedy”, which conveyed hope for justice and systemic change. Similarly, references to “Lessons from the Tragedy of the Sewol Ferry” linked Itaewon to Korea’s broader history of national disasters, evoking both caution and determination to avoid repeating past failures. Finally, “Ground Debate Among Candidates for the National Assembly Election: Power of the People’s Jeong Yeong-seon” reflects civic pride and satisfaction with democratic participation, indicating that even amid crisis, political engagement could generate positive emotions. These expressions of hope and progress are not incidental; they likely represent discursive attempts to reframe tragedy from a moment of loss into a catalyst for reform and solidarity. Collectively, they suggest that digital discourse did not simply mirror trauma but also may have facilitated processes of resilience and adaptation.

The refinement of search keywords produced clear differences in the analytical results. Early datasets generated from broader terms yielded dispersed clusters and mixed, non-crisis-related discussions. After adopting the optimized Korean terms “Itaewon Disaster” and “Itaewon Crush Accident”, combined with advanced text cleaning procedures (e.g., tokenization, stop word removal, etc.), the analysis revealed more cohesive thematic groupings centered on public grief, accountability, and government response. This shift improved the prevision of both semantic clustering and lexical redundancy and clarified sentiment polarity, thereby increasing the overall validity and interpretive accuracy of results.

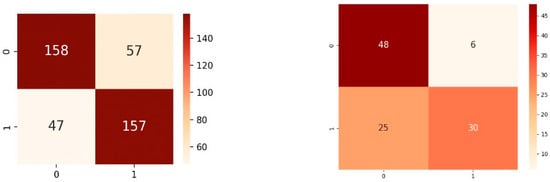

3.4. Evaluating Model Performances

The sentiment classification model was implemented in Python’s scikit-learn library. A logistic regression algorithm (random state = 0) was applied with default parameters to classify sentiment polarity. Input data consisted of tokenized Naver post titles and contents, transformed into TF-IDF vectors using CountVectorizer and TfidfTransformer. The dataset was divided into training and testing sets in a 75:25 ratio to ensure balanced evaluation. Instances corresponding to neutral sentiment were excluded during preprocessing through binary recoding of sentiment scores, ensuring clear polarity distinction between positive and negative classes. This decision is particularly appropriate in crisis communication contexts, where neutral expressions often serve an informational rather than evaluative function.

As shown Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Table 2 and Table 3, this configuration produced balanced performances across classes, with consistent precision and recall values that indicate stable polarity separation. The model effectively captured emotional divergence within Naver discourse, reflecting how affective expression fluctuated in parallel with major crisis related developments.

Figure 11.

Confusion matrix and results of logistic regression model—Itaewon tragedy (left) and Itaewon crush accident (right).

Table 2.

Logistic regression model results for Itaewon tragedy.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model results for Itaewon crush accident.

The sentiment analysis model for the Itaewon Disaster demonstrates a balanced performance, with precision and recall around 0.75, indicating its effectiveness in accurately capturing both positive and negative sentiments related to the event. The confusion matrices in Figure 11 illustrate these performance characteristics, showing the distribution of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives for both datasets.

This balance ensures that the model provides a nuanced understanding of public reactions without disproportionately favoring either sentiment, which is crucial for analyzing the diverse viewpoints surrounding a sensitive topic. Conversely, the Itaewon crush incident model reveals a precision–recall trade-off, achieving high precision (0.83) but low recall (0.55) for positive sentiments and high recall (0.89) but lower precision (0.66) for negative sentiments. This suggests a heightened sensitivity to negative feedback, which is essential for identifying critical issues in crisis scenarios but may result in underrepresenting positive sentiments. This disparity highlights the model’s utility in crisis sentiment analysis while indicating the need for improved positive sentiment detection to provide a more comprehensive understanding of public opinion. Model validation followed a 70-25 train–test split using a customized Korean sentiment lexicon, which assigns polarity values to context-specific tokens. The model’s performance was evaluated using precision, recall, F1, and accuracy scores to ensure both statistical reliability and linguistic accuracy in Korean-language sentiment detection.

3.5. Investigating Relationship Sentiment in Relation to Time and Content

Correlation matrices were generated using the Pearson correlation method implemented in the panda’s library, which enabled the examination of linear relationships among sentiment scores, post, length, and temporal variables. Descriptive statistics for sentiment scores, title length, and year are reported in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A. These provide baseline characteristics of the Itaewon tragedy and Itaewon crush accident datasets and contextualize the subsequent correlation and regression analyses.

For the “Itaewon Tragedy” dataset, the correlation matrix quantifies both the strength and direction of relationships among key variables. A coefficient near zero suggests minimal association, while positive coefficients indicate a tendency for variables to rise together, and negative coefficients signal an inverse pattern. The correlation between sentiment score and title_length is weakly positive (r = 0.087), meaning that longer titles are only slightly associated with higher sentiment scores (see Table A3). While the effect is small, it may suggest that titles with more elaboration carry a slightly evaluative or affective tone.

By contrast, the relationship between sentiment score and year is both statistically significant (p < 0.001) and substantiative, showing that sentiment scores varied systemically across time periods. This points to a temporal influence, with changes in sentiment reflecting evolving public attitudes and media framings of the tragedy (see Table A3).

Similar, title_length is significantly correlated with year (p < 0.001), indicating that how titles are structured has shifted over time. This suggests not only stylistic or editorial evolution in reporting practices but also potential adaptation in how information about the tragedy is communicated to the public (see Table A3).

Taken together, these results highlight that beyond the surface of statistical associations, content characteristics such as title length and the temporal context in which reporting occurs meaningfully shape patterns in sentiment expression. The findings reinforce the need to consider both linguistic form and historical context when analyzing discourse around collective crises.

For the “Itaewon Crush Incident” dataset specifically, the results reveal subtle but meaningful relationships. The weak positive correlation (r = 0.139) between sentiment scores and title lengths indicates that longer titles are slightly more likely to convey positive sentiment. Conversely, sentiment scores and year exhibit a weak negative correlation (r = −0.060), suggesting a mild decline in sentiment over time, through this association is not statistically significant (p = 0.106). Meanwhile, the negative correlation between title lengths and year (r = −0.154, p = 0.001) suggests a trend toward shorter titles in later years, which may reflect changes in journalistic style or editorial practices over time (see Table A4).

Regression analysis provides a more nuanced understanding of these dynamics. The overall model including both year and Title_Count is statistically significant (F = 4.601, p = 0.011), demonstrating that the predictors collectively explain variance in sentiment scores (see Table A5 and Table A6). Among the predictors, Title_Count exerts a statistically significant positive effect (β = 0.090, p = 0.006), implying that as titles become longer, sentiment scores increase. By contrast, year does now show a significant independent effect (β = −0.319, p = 0.413), indicating that temporal variation alone does not reliably predict sentiment once title length is accounted for.

Overall, these findings suggest that structural features of reporting, such as how long a title is, exert a stronger influence on sentiment patterns than temporal progression alone. This highlights the importance of considering textual form alongside historical context when analyzing how media narratives about collective crises evolve.

4. Discussion

Social media platforms facilitate the maintenance of both weak ties—less intimate social connections—and strong ties—close personal relationships. This kind of dynamic enables individuals to feel a sense of interconnectedness on a broader scale, potentially enhancing their perception of social support during significant events [68]. The analysis of linguistic patterns and communication dynamics surrounding the “Itaewon tragedy” and “Itaewon crush accident” yields several breakthrough insights into public discourse and media portrayal of significant events.

The investigation of the Itaewon Halloween crowd crush incident shows how Naver echo chamber dynamics affect public perception. High-frequency keywords from mainstream media supported opinions on government accountability, public safety, and leadership in debates. However, low-frequency keywords revealed more diverse public mood through personal statements and critical opinions. Authoritative discourses and grassroots voices generated echo chambers that magnified some narratives and marginalized others, affecting public opinion. Such dynamics mirror patterns of digital resistance, where online discourse actively constructs polarization and “otherness”, positioning groups in opposition and reinforcing divides during moments of crisis [69].

Compared with earlier studies on crisis-related social media analysis, which often relied on either sentiment classification or network topology mapping alone, this study advances the methodological conversation by employing a dual-layered framework that integrates semantic network analysis with sentiment polarity modeling. Previous works have typically examined emotional tone in isolation or focused narrowly on information diffusion, overlooking how emotional intensity interacts with structural echo chamber formations. The integrated Python–Gephi model developed in this research captures both dimensions simultaneously, revealing how emotionally charged narratives are embedded in network discourse structures. This multi-layered approach thus provides a richer and more context-sensitive understanding of digital communication during crises, highlighting not only what people feel but also how those emotions are circulated and reinforced across online communities.

Data study on Naver revealed that safety measures, government accountability, and victims’ and families’ emotional recovery are the main public concerns. This debate focused on the president and government replies, emphasizing popular need for transparency and decisive action. Discussions about forgiveness, social support, and foreign relations revealed nuanced concerns beyond safety issues, showing a broader socio-political context influencing public attitudes.

Naver sentiment changed complexly during and after the disaster. As the community discussed accountability and legislative responses in the months that followed, public emotions changed from outrage and loss. Echo chamber dynamics helped us appreciate the tragedy’s ramifications better by contrasting dominant media narratives with alternate perspectives. Sentiment analysis showed a progressive shift toward accountability and community support, showing how echo chamber discussions can buffer public reactions and help society respond to crises.

The various emotional responses and public views after the Itaewon Halloween crowd crush incident demonstrate the importance of semantic and public sentiment analysis of echo chambers, appraisal theory, and social identity theory. We may see how dominant narratives and grassroots manifestations impact collective sentiments by monitoring volatile sentiment changes over three years. Understanding echo chambers shows how specific narratives can be amplified, polarizing opinions and inhibiting healthy dialog. Researchers and politicians must consider how media systems affect public sentiment.

Appraisal theory helps explain how people process the events that influence their emotional responses, such as anger toward perceived negligence and expressions of grief and frustration [70]. We can uncover public emotional triggers by evaluating how emotions change in response to incident factors like government accountability and safety measures. Emotional responses in public discourse are not only personally appraised but are also socially constructed, as shown in research demonstrating how social influence shapes the appraisal of others’ sentiments and reinforces collective evaluations [71]. This knowledge can help communicate with the community’s grief, rage, and demand for justice.

Social identity theory also illuminates how people respond to communal identities like victimization or community solidarity. This theory facilitates exploration of group affiliations rooted in self-concept and social beliefs [72]. For instance, Naver users may express solidarity and demand justice for victims, their families, or the communities affected by the tragedy. The investigation shows that sentiments are firmly rooted in group dynamics and cultural narratives. We can better comprehend the emotional environment post tragedy, public concerns, and how different social groups handle collective trauma by using these theories in semantic and sentiment analysis.

Integrating these theoretical frameworks helps us understand and handle the complex interactions that affect public perception. This comprehensive approach is essential for designing crisis communication methods that promote resilience, facilitate social cohesion, and include all voices, especially marginalized ones, after major disasters. These findings carry practical implications. Social media platforms should consider building real-time sentiment monitoring systems to flag emotionally volatile discourse clusters. Media organizations can benefit from understanding public emotional trajectories to adjust framing strategies and avoid amplifying divisive narrative. For the public, increased transparency about algorithmic curation may help mitigate echo chamber effects and encourage exposure to diverse viewpoints.

Looking ahead, scholars and practitioners must explore how platform-centric echo chamber dynamics shape long-term crisis discourse. Future agendas should examine comparative platform behaviors, algorithmic responsibility, and the ethical boundaries of digital amplification during national tragedies. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing proactive crisis communication and more balanced disaster coverage. Taken together, the findings across semantic, sentiment, and network analyses converge to show how emotion and structure co-evolve within Naver discourse. The following conclusion synthesizes these insights to highlight the study’s broader methodological and theoretical contributions.

5. Conclusions

At its core, this study demonstrated how sentiment and structure intertwine in shaping collective meaning during national crises. The Naver data reveal that emotion is not merely expressed online but organized through patterns of connection, amplification, and silence. The results from semantic network, sentiment, and correlation analyses collectively substantiate the argument. The semantic analysis uncovered two intertwined layers of discourse: official narratives emphasizing accountability and safety, and grassroots expressions of grief, frustration, and resistance. Network clustering showed how these perspectives were sustained by echo-chamber mechanisms that intensified alignment and constrained deliberation. The sentiment model achieved balanced precision–recall (~0.75), confirming the reliability of affective polarity detection in Korean-language discourse. Finally, the correlation analysis identified systematic links between sentiment, textual features, and time, indicating that emotional responses followed structured trajectories rather than spontaneous outbursts. Collectively, these patterns reinforce the validity of the proposed analytical design, demonstrating how this research captures the intertwined dynamics of emotion and structure.

The Itaewon Halloween crowd crush emerges not only a tragic social event but also a case through which the mechanics of digital discourse and emotional processing can be better understood. By contrasting “Itaewon Tragedy” and “Itaewon Crush Accident” datasets, we find that framing significantly shaped the trajectory of public emotions. The tragedy frame sustained anger, grief, and demands for justice, while the accident frame encouraged gradual normalization and emphasis on systemic reforms. These findings address our research questions by demonstrating that semantic structures and sentiment fluctuations on Naver are not random but closely tied to the ways crises are linguistically framed and politically situated.

Importantly, the results also show that content features such as title length mattered likely more than chronology in predicting sentiment, suggesting that the depth of framing is critical in determining whether discourse intensifies outrage or enables reflective engagement. This insight advanced the literature on sentiment analysis by linking technical indicators to broader social dynamics of accountability, memory, and resilience. Moreover, the Itaewon case illustrates how echo chambers on Naver did not merely reflect emotions but likely co-produced them, amplifying dominant narratives and marginalizing alternative perspectives. Similar dynamics are evident offline, as studies of Indonesia’s new capital relocation show how state, corporate, and indigenous actors contest access, highlighting how power asymmetries structure inclusion and exclusion [73].

Taken together, this research contributes to ongoing debates of crisis communication by highlighting digital platforms function as arenas where grief, blame, solidarity, and reform are negotiated in real time. It underscores that effective crisis communication strategies must not only manage information flows but also engage with the emotional currents that shape public trust and social cohesion. As in innovation systems research, which calls for integrating social dimensions into technical frameworks [74], this study shows that crisis communication must address not only information flows but also collective emotions and discourse. These findings also resonate with broader concerns in democratic discourse, as social media platforms not only mediate sentiment but also reinforce echo chambers and polarization, limiting inclusive dialog and amplifying societal divides [75]. Similar state-level dynamics are evident in India’s COVID-19 aid response, where rising audience costs compelled leaders to adjust crisis strategies [76]. Future scholarship should build on this by examining how framing, algorithmic visibility, and echo chamber dynamics interact across platforms, and how these processes influence collective recovery after large-scale tragedies. In this way, the Itaewon tragedy serves as both cautionary and instructive case, showing that digital discourse can deepen polarization but also provide pathways for resilience, accountability, and reform.

Limitations and Further Research

The sole use of Naver data analysis limits this study. Naver gives vital insights into popular sentiment, yet it is simply one aspect of South Korean online discourse. A deeper investigation could examine hyperlinks and other metrics linked with Naver authors or accounts to better understand public opinion sources and influencers. Links enable global connection and interaction via the internet. They enhance bilateral communication, coordination, and cooperation through shared interests, backgrounds, or initiatives [77]. Including Kakao and other Korean social media networks beyond Naver may provide a more complete picture of public attitude. To measure public interest and participation with information, future studies could examine engagement measures like shares, comments, and responses.

While this model performed effectively on the Naver dataset, future studies should validate its robustness across multiple platforms or cross linguistic corpora to assess generalizability in different communicative and cultural environments.

Beyond platform scope, this study also does not address the ideological dimensions of discourse. Future research could integrate computational sentiment analysis with critical discourse analysis to reveal how power and ideology are embedded in crisis communication [78]. Future research could better comprehend public conversation around tragedies like the Itaewon tragedy by analyzing more platforms and engagement indicators. Researchers could also compare domestic and international crises, as research on Korean media coverage of the Palestine–Israel conflict shows how Naver’s framing privileges some narratives while sidelining others [79].

This study used publicly available data from Naver, accessed in accordance with the platform’s terms of service. No personally identifiable information was collected or analyzed. All data were aggregated and anonymized prior to analysis. Institutional Review Board approval was not required as the research used publicly accessible, non-reactive data. Derived scripts and data structures are available upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-W.P. and C.V.L.; methodology, H.-W.P. and C.V.L.; software, C.V.L.; validation, H.-W.P. and C.V.L.; formal analysis, C.V.L.; investigation, C.V.L. and H.-W.P.; resources, C.V.L.; data curation, C.V.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.L.; writing—review and editing, C.V.L., and H.-W.P.; visualization, C.V.L.; supervision, H.-W.P.; project administration, H.-W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Statistics Data Used for Regression Analysis

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics for Itaewon tragedy data.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics for Itaewon tragedy data.

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sentiment_score | −1.46 | 4.926 | 1184 |

| Title_Length | 22.42 | 7.726 | 1184 |

| Year | 2024 | 0.000 | 1184 |

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics for Itaewon Crush accident data.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics for Itaewon Crush accident data.

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sentiment_score | −1.91 | 5.325 | 433 |

| Title_Length | 22.49 | 7.906 | 433 |

| Year | 2022.20 | 0.659 | 433 |

Table A3.

Correlations of variables for Itaewon tragedy data.

Table A3.

Correlations of variables for Itaewon tragedy data.

| Correlation Type | Variables | Sentiment_Score | Title_Length | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | Sentiment_score | 1.000 | 0.087 | |

| Title_length | 0.087 | 1.000 | ||

| Year | 1.000 | |||

| Sig (1 tailed) | Sentiment_score | 1.000 | 0.087 | |

| Title_length | 0.087 | 1.000 | ||

| year | 1.000 | |||

| N | Sentiment_score | 1184 | 1184 | 1184 |

| Title_length | 1184 | 1184 | 1184 | |

| year | 1184 | 1184 | 1184 |

Table A4.

Correlations of variables for Itaewon crush accident data.

Table A4.

Correlations of variables for Itaewon crush accident data.

| Correlation Type | Variables | Sentiment_Score | Title_Length | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | Sentiment_score | 1.000 | 0.139 | 0.060 |

| Title_length | 0.139 | 1.000 | −0.154 | |

| Year | −0.60 | −0.154 | 1.000 | |

| Sig (1 tailed) | Sentiment_score | 0.002 | 0.106 | |

| Title_length | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||

| year | 0.106 | 0.001 | ||

| N | Sentiment_score | 433 | 433 | 433 |

| Title_length | 433 | 433 | 433 | |

| year | 433 | 433 | 433 |

Table A5.

Model summary for Itaewon tragedy (top) and Itaewon crush accident (bottom).

Table A5.

Model summary for Itaewon tragedy (top) and Itaewon crush accident (bottom).

| Itaewon Tragedy | Change Statistics | |||||||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std Error of Estimate | R Square Change | F Change | Df1 | Df2 | Sig F. Change | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | 0.087 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 4.909 | 0.008 | 9.064 | 1 | 1182 | 0.003 | 1.833 |

| Itaewon Crush Accident | Change Statistics | |||||||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std Error of Estimate | R Square Change | F Change | Df1 | Df2 | Sig F. Change | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | 0.145 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 5.281 | 0.021 | 4.601 | 2 | 430 | 0.011 | 1.927 |

Table A6.

Regression analysis: ANOVA Itaewon tragedy (top) and Itaewon crush accident (bottom).

Table A6.

Regression analysis: ANOVA Itaewon tragedy (top) and Itaewon crush accident (bottom).

| Itaewon Tragedy | ||||||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | 218.424 | 1 | 218.424 | 9.064 | 0.003 |

| Residual | 28,483.789 | 1182 | 24.098 | |||

| Total | 28,702.213 | 1183 | ||||

| Itaewon Crush Accident | ||||||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | 256.645 | 2 | 128.322 | 4.601 | 0.11 |

| Residual | 11,992.473 | 430 | 27.889 | |||

| Total | 12,249.118 | 432 | ||||

References

- Kim, J.Y. Mourning for Itaewon Halloween tragedy. Inter. Asia Cult. Stud. 2023, 24, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, E. Itaewon’s suspense: Masculinities, place-making and the US Armed Forces in a Seoul entertainment district. Soc. Anthropol. 2014, 22, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, V.; Earl, C. A Visual Guide to How the Seoul Halloween Crowd Crush Unfolded. The Guardian. 1 November 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/31/how-did-the-seoul-itaewon-halloween-crowd-crush-happen-unfolded-a-visual-guide (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Thomas, M.; Lee, H.; Mackenzie, J. Itaewon Crowd Crush: Horror as More than 150 Die in Seoul District. BBC News. 30 October 2022. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-63443044 (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Kang, T. Hold the Suspect!: An Analysis on Media Framing of Itaewon Halloween Crowd Crush. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, J.; Vos, M. Developing a conceptual framework for investigating communication supporting community resilience. Societies 2015, 5, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, A.; Friedman, D.B.; Koskan, A.; Barr, D. Disaster communication on the Internet: A focus on mobilizing information. J. Health Commun. 2009, 14, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Chan, E.; Hyder, A.A. Web 2.0 and Internet social networking: A new tool for disaster management? Lessons from Taiwan. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2010, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujah, O.I.; Ogbu, C.E.; Kirby, R.S. “Is a game really a reason for people to die?” Sentiment and thematic analysis of Twitter-based discourse on Indonesia soccer stampede. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhai, W.; Cheng, C. Crowd detection in mass gatherings based on social media data: A case study of the 2014 Shanghai New Year’s Eve stampede. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Pei, H.; Wu, H. Early warning of human crowds based on query data from Baidu Map: Analysis based on Shanghai stampede. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.06780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragini, J.R.; Anand, P.R.; Bhaskar, V. Big data analytics for disaster response and recovery through sentiment analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M. Twitter and the Affordance: A Case Study of Participatory Roles in the #Marchforourlives Network. Digital 2024, 4, 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W. YouTubers’ networking activities during the 2016 South Korea earthquake. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Shin, D.; Kim, Y. Structural change in search engine news service: A social network perspective. Asian J. Commun. 2012, 22, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAVER. Ad Services. Available online: https://saedu.naver.com/adguide/eng.naver (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Dwyer, T.; Hutchinson, J. Through the looking glass: The role of portals in South Korea’s online news media ecology. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2019, 18, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. Naver SEO: How to Rank in Korea. InterAd. 30 January 2024. Available online: https://www.interad.com/en/insights/naver-seo-guide (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Nam, K.K.; Ackerman, M.S.; Adamic, L.A. Questions in, knowledge in? A study of Naver’s question answering community. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’09), Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, S.; McCombs, M.E. The attribute agenda-setting influence of online community on online newscast: Investigating the South Korean Sewol ferry tragedy. Asian J. Commun. 2017, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, F.; Kambhampati, S. Listening to the Crowd: Automated Analysis of Events via Aggregated Twitter Sentiment. Arizona State University, 1 December 2013. Available online: https://asu.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/listening-to-the-crowd-automated-analysis-of-events-via-aggregate (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Jiang, J.; Ren, X.; Ferrara, E. Social media polarization and echo chambers in the context of COVID-19: Case study. JMIRx Med. 2021, 2, e29570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, M.; Cavaliere, D.; De Maio, C.; Fenza, G.; Loia, V. Towards echo chamber assessment by employing aspect-based sentiment analysis and GDM consensus metrics. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2024, 39–40, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, G.; Hu, X.; Maciejewski, R.; Liu, H. An overview of sentiment analysis in social media and its applications in disaster relief. In Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 639, pp. 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, J. Modelling and analyzing the semantic evolution of social media user behaviors during disaster events: A case study of COVID-19. ISPRS Int. J. Geo. Inf. 2022, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgaertner, B.; Justwan, F. The Preference for Belief, Issue Polarization, and Echo Chambers. Synthese 2022, 200, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R.K. Echo Chambers Online?: Politically Motivated Selective Exposure among Internet News Users. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2009, 14, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, F.; Scheibe, K.; Stock, M.; Stock, W.G. Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles of Fake News in Social Media: Man-Made or Produced by Algorithms? In Proceedings of the Hawaii University International Conferences on Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences & Education (AHSE), Honolulu, HI, USA, 3–5 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brugnoli, E.; Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Scala, A. Recursive Patterns in Online Echo Chambers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D. Disaster risk reduction: Psychological perspectives on preparedness. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity theory. In Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology; Christie, D.J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichenko, Y.; Pham, T.; Talavera, O. Social media, sentiment and public opinions: Evidence from #Brexit and #USElection. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 136, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazli, A.K. A Theoretical Framework on Disaster Communication. J. Acad. Approaches 2024, 15, 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, J. Social identity theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Jung, K.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, H.W. Risk communication on social media during the Sewol ferry disaster. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2019, 18, 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sams, S.; Park, H.W. The presence of hyperlinks on social network sites: A case study of Cyworld in Korea. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, H.W.; Thelwall, M. Hyperlink analyses of the World Wide Web: A review. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2003, 8, JCMC843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Analysis of characteristics and trends of Web queries submitted to NAVER, a major Korean search engine. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2009, 31, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, R.; Wibowo, A. Algorithmic Resonance and User Behavior in Engagement Platforms: Toward a Neuro-Behavioral Model. Telemat. Inform. 2025, 93, 102013. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, A.J.; Rabbi, M.S.; Rainy, T.A. Strategic Use of Engagement Marketing in Digital Platforms: A Focused Analysis of ROI and Consumer Psychology. J. Sustain. Dev. Policy 2025, 1, 170–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteson, A.; Choi, S.; Lim, H. Inference of Korean public sentiment from online news. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2018, 9, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, H.; Cho, Y.; Shim, E.; Lee, K.; Song, G. Public trauma after the Sewol ferry disaster: The role of social media in understanding the public mood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10974–10983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaturo, E.; Aragona, B. Methods for big data in social sciences. Math. Popul. Stud. 2019, 26, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Mehmood, A.; Choi, G.S.; Park, H.W. Global mapping of artificial intelligence in Google and Google Scholar. Scientometrics 2017, 113, 1269–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiorka, W. ‘Big Data’ from Online Interactions Offer A Rich Object of Study for Academics and Policy-Makers Interested in Human Nature and Economic Behaviour. The London School of Economics and Political Science. 2014. Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/72023/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Bai, Q.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Miao, X.; Xiu, Q. The web crawler based on Python to obtain public emotional data analysis—Take the Weibo hot search data as an example. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), Beijing, China, 13–15 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Su, H.; Wen, J.H. Analysis and mining of Internet public opinion based on LDA subject classification. J. Web Eng. 2021, 20, 2457–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chung, D.; Park, H.W. Analytical framework for evaluating digital diplomacy using network analysis and topic modeling: Comparing South Korea and Japan. Inf. Process. Manag. 2018, 56, 1468–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacomy, M.; Venturini, T.; Heymann, S.; Bastian, M. ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yun, J.; Jang, J.; Kim, Y. From ground trust to truth: Disparities in offensive language judgments on contemporary Korean political discourse. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.14712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.H. Contextual variation in Korean evidentiality: A corpus-based analysis of genre, register and discourse. Discourse Cogn. 2024, 31, 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open-source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2009), San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 361–362. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/13937 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Alvares, N.B.; Thakur, N.N.; Fernandes, N.S.P.D.; Jain, N.K. Sentiment analysis using opinion mining. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2016, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejwani, R. Sentiment analysis: A survey. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1405.2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M. Sentiment analysis: An overview from linguistics. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2016, 2, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sams, S.; Lim, Y.S.; Park, H.W. e-Research applications for tracking online socio-political capital in the Asia-Pacific region. Asian J. Commun. 2011, 21, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W. Bibliometric methods for detecting and analysing emerging research topics. Prof. Inf. 2012, 21, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.W.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Machine learning and expert judgement: Analyzing emerging topics in accounting and finance research in the Asia–Pacific. Abacus 2019, 55, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciani, C.; Corbetta, A.; Haghani, M.; Nishinari, K. How crowd accidents are reported in the media: Lexical and sentiment analyses. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.14633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Provan, T.; Wei, F.; Liu, S.; Ma, K. Semantic-preserving word clouds by seam carving. Comput. Graph. Forum 2011, 30, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimerl, F.; Lohmann, S.; Lange, S.; Ertl, T. Word Cloud Explorer: Text analytics based on word clouds. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2014), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danowski, J.A. Bitcoin Price Associations with Political Polarization, Digital Authoritarianism, Trade Protectionism, Deglobalization, and Language Entropy. ROSA J. 2024, 2, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, A.; Rijal, Z. Modern Media Arabic: A study of Word Frequency in World Affairs and Sports Sections in Arabic Newspapers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2011. Available online: https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/2882/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Thelwall, M. Text in social networking Web sites: A word frequency analysis of Live Spaces. First Monday 2008, 13, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.W. Pressure Weighs on Yoon over Accountability in Itaewon Tragedy. Korea Times. 7 November 2022. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/05/113_339275.html (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Skarpelos, Y.; Messini, S.; Roinioti, E.; Karpouzis, K.; Kaperonis, S.; Marazoti, M.-G. Emotions during the pandemic’s first wave: The case of Greek tweets. Digital 2024, 4, 126–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primanda, S.; Hasmawati; Nurrahmi, H. Implementation of IndoBERT for sentiment analysis of Indonesian presidential candidates. Ind. J. Comput. 2024, 9, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.E.; Jung, K.; Park, H.W. Social media use during Japan’s 2011 earthquake: How Twitter transforms the locus of crisis communication. Media Int. Aust. 2013, 149, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, Y.O. Digital resistance: Discursive construction of polarization and otherness in Oduduwa secessionists’ social media activism. Societies 2023, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bippus, A.M.; Young, S.L. Using appraisal theory to predict emotional and coping responses to hurtful messages. Interpersona 2012, 6, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jha, A.K.; Shah, C. Social influence on future review sentiments: An appraisal-theoretic view. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2019, 36, 610–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Attending to identities: Ideology, group memberships, and perceptions of justice. In Advances in Group Processes; Thye, S.R., Lawler, E.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; Volume 25, pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodir, A.; Ahmad, R. Analysis of Critical Agrarian Perspective on Nusantara Capital City (IKN) Development Policy in Indonesia. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2025, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, D.R.; Roig-Tierno, N.; Tur, A.M.; Sendra-Pons, P. Conceptual structure of innovation systems: A systematic approach through qualitative data analysis. ROSA J. 2024, 1, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Morales, G.D.F.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Yan, L. Navigating the Audience Costs of Humanitarian Aid for Rising States: A Case Study of India’s COVID-19 Response. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2025, 24, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, T.; Ma, F. Blog-supported scientific communication: An exploratory analysis based on social hyperlinks in a Chinese blog community. J. Inf. Sci. 2010, 36, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. To Critique Crisis Communication as a Social Practice: An Integrated Framework. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 874833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.S.; Kim, C.-W.; Park, H.W. Naver News analysis and Korean representation of issue between Palestine and Israel. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2025, 24, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]