Abstract

Acrylic resin is widely used in removable dental prostheses due to its biocompatibility, low cost, and ease of handling; however, it presents mechanical limitations and a high susceptibility to microbial colonization, particularly by Candida albicans. The incorporation of nanoparticles into polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) has been investigated as a strategy to mitigate these drawbacks. This scoping review evaluated the impacts of incorporating chitosan (CTS) nanoparticles into PMMA on antimicrobial activity and mechanical properties. A comprehensive search of the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and BVS databases resulted in the retrieval of 1912 records. After removing 557 duplicates and applying the eligibility criteria, 9 in vitro studies were included. Despite methodological heterogeneity, most studies reported enhanced antifungal activity against C. albicans and improvements in mechanical properties, such as microhardness and overall strength, when CTS was incorporated. Thus, CTS appears to be a promising additive for denture base resins, with the potential to reduce denture-associated infections and increase the longevity of prostheses. Nevertheless, standardized methodologies and well-designed in vivo and clinical investigations remain essential to determine optimal concentrations, incorporation techniques, and long-term clinical performance before implementation. A scoping review design was selected due to the exploratory nature of the study and the heterogeneity of available evidence, which precludes direct comparisons and quantitative synthesis.

1. Introduction

The growing demand for prosthetic rehabilitation has led to an increase in the use of complete and partial removable dentures [1]. The most widely used material for this purpose is polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), due to its biocompatibility, low cost, ease of handling, and acceptable esthetics [2,3]. Despite these advantages, PMMA presents limitations, particularly related to its mechanical strength [4] and susceptibility to microbial colonization [5].

Among the microorganisms involved, Candida albicans is of particular concern due to its ability to form resistant biofilms on prosthetic surfaces, leading to oral mucosal inflammation, patient discomfort, and reduced denture longevity [6]. This clinical scenario underscores the importance of developing PMMA with enhanced antimicrobial and mechanical properties.

In recent years, the incorporation of nanoparticles into PMMA has been investigated as a strategy to overcome these drawbacks [7]. While various nanoparticles (e.g., metallic) have been tested [8,9,10], their use may compromise esthetics or biocompatibility. In this regard, chitosan (CTS) emerges as a promising alternative. In comparison, other nanoparticles such as silver, titanium dioxide (TiO2), zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), and copper [11] have also been incorporated into PMMA [12]. Silver exhibits strong antimicrobial effects; however, its tendency to cause discoloration and potential cytotoxicity may limit its long-term use [13]. TiO2 and ZrO2 have been shown to improve mechanical performance; however, concerns remain regarding changes in esthetics and surface translucency [14]. In contrast, CTS is characterized by both antimicrobial and bioactive properties as well as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and a lack of discoloration, making it particularly attractive for use in denture base applications [15,16]. In this regard, as an abundant, biodegradable, and non-toxic natural polysaccharide which exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, chitosan (CTS) emerges as a promising alternative [11,13]. Its inherent esthetic neutrality and versatility further contribute to its appeal for a range of dental applications.

The ability of CTS to inhibit microbial adhesion and growth, along with its favorable bioactivity, has led to its application in various dental fields, such as restorative materials and dentifrice formulations [14,17]. Indeed, recent investigations across these domains have reported encouraging results, demonstrating enhanced antimicrobial efficacy against common oral pathogens, improved mechanical performance, and favorable biocompatibility in diverse dental contexts. Nevertheless, a consensus is lacking regarding the most effective forms of incorporation, optimal concentration, or the clinical impacts of CTS-modified PMMA.

Given the current lack of consensus and the emerging, yet heterogeneous, nature of the available evidence, this scoping review aimed to comprehensively map and synthesize the literature on the effects of incorporating CTS nanoparticles into PMMA, with a focus on its mechanical and antimicrobial properties. A scoping review was chosen over a systematic review due to the exploratory nature of the study, which allowed for a broader identification of all relevant evidence, recognition of diverse methodologies, and the straightforward elucidation of existing knowledge gaps. This approach is optimal for developing a foundational understanding to guide more focused research and potential clinical applications in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

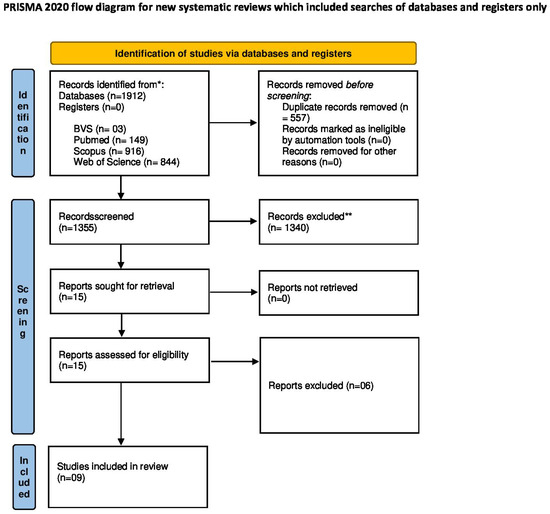

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, and a PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the study selection process is presented in the Results Section. The review protocol was not prospectively registered in databases such as PROSPERO, as scoping reviews are exploratory in nature and often do not meet the eligibility criteria for such registration. Nonetheless, the PRISMA-ScR guidelines were followed to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility. A completed PRISMA 2020 checklist is available in the Supplementary Materials.

This methodological approach enabled the mapping of central concepts, exploration of research areas, and identification of knowledge gaps. To construct the clinical question, the following concepts were taken into consideration: CTS nanoparticles, removable prostheses, and antimicrobial and mechanical properties. Based on these definitions, the following research question was formulated: “Does the addition of CTS nanoparticles improve the antimicrobial activity and mechanical resistance of PMMA in the manufacture of removable dentures?”. The structured PECO framework that guided the formulation of this research question is presented in Appendix A, Table A1.

Two independent researchers (D.M.D. and L.P.B.) conducted the electronic searches. The search was conducted until 7 October 2022 across four electronic databases—Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, Virtual Health Library, and Scopus—without restrictions on language or publication date (see Appendix A, Table A2 for the search strategies). Before the selection process, reviewer calibration was tested using Cohen’s Kappa with 20% of the included articles, and the resulting Kappa value (K = 0.90) indicated excellent agreement. According to the standard categorization, Kappa values are interpreted as follows: <0.20 = poor, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial, and >0.81 = excellent.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In vitro studies evaluating the incorporation of chitosan nanoparticles into PMMAto improve its mechanical and/or microbiological properties were included. The following were excluded: (1) in vivo studies, due to methodological heterogeneity and the limited number available; (2) case reports and case series; (3) literature reviews; and (4) studies that did not involve both chitosan and PMMA simultaneously, or that investigated variables outside the scope of this review.

2.2. Databases and Search Strategy

The articles retrieved in the search were exported to the EndNote® program (Clarivate Analytics®, version X7) for management and removal of duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened independently, and potentially eligible articles or those with insufficient information were read in full. Articles were then either included or excluded according to the eligibility criteria.

The search yielded a total of 1912 records. After removing 557 duplicates, 1355 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 15 articles were selected for full-text reading, and 6 were subsequently excluded due to not meeting the eligibility criteria. Therefore, 9 studies were included in the final review. Manual searches of reference lists from the included studies were also performed. In cases of disagreement, a third researcher (R.G.) was consulted.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extracted from the included studies comprised authors, year of publication, study design, sample, type and concentration of CTS, evaluated outcomes, tests used, and main results.

No formal validated risk of bias assessment tool was applied, as standardized instruments for in vitro studies within the context of a scoping review are scarce. However, a systematic qualitative critical appraisal of the included studies was performed, evaluating aspects such as sample size, experimental design, CTS characterization (concentration and type), method reproducibility, and clarity of outcome reporting. This acknowledged absence of a structured risk of bias evaluation tool represents a limitation, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation of the findings.

The study identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram, presented in Section 3 (Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The database search resulted in the retrieval of 1912 records from PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and BVS. After automatic and manual deduplication, 557 duplicates were removed, leaving 1355 records for title and abstract screening.

During screening, 1340 records were excluded for the following reasons: (i) studies not involving CTS or PMMA (n = 942), (ii) studies unrelated to PMMA (n = 243), and (iii) studies not reporting antimicrobial or mechanical outcomes (n = 155). A total of 15 articles were selected for full-text reading. Of these, six were excluded: (i) three studies did not evaluate both CTS and PMMA simultaneously, (ii) two studies addressed variables outside the scope of this review, and (iii) one study was not available in full text. Thus, nine in vitro studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis. The study selection process is detailed in the PRISMA 2020 diagram (Figure 1), and the exclusion criteria for each stage are detailed in Appendix A Table A3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for study selection. [18].

The included studies were conducted in Asia (3), Europe (4), South America (1), and North America (1), and were published between 2008 and 2020.The types of PMMA investigated varied: three studies used thermopolymerizable PMMA [19,20,21], two used self-polymerizable resin [22,23], two employed ultraviolet-polymerized resin [24,25], and the resin type was not specified in two studies [26,27]. A comparative summary of all included studies (author, year, CTS type and concentration, methods, tested parameters, and key findings) is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of PMMA modified with chitosan was evaluated in four studies [19,20,21,22]. A general trend toward enhanced antifungal effects was observed, particularly against Candida albicans, although inconsistencies were noted regarding biofilm formation.

Gondim et al. [19] and Namangkalakul et al. [20] reported significant antifungal effects. Gondim et al. [19] observed reductions in Candida albicans and Candida spp. biofilm formation, correlated with improvements in surface roughness and microhardness—which was attributed to the polycationic nature of chitosan—without compromising material properties. Namangkalakul et al. [20] demonstrated the inhibition of Candida albicans adhesion to PMMA, suggesting its potential as an antifungal adhesive. Both studies employed MIC and MFC assays, which provide strong methodological support.

In contrast, Song et al. [21] demonstrated that the method of incorporation significantly impacted antimicrobial performance. Chemical grafting produced more stable activity against Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans, whereas physical addition yielded higher initial antifungal capacity but also greater degradation after aging. Walczak et al. [22] confirmed the antifungal effects of chitosan salts (CS-HCl, CS-G) at concentrations ranging from 0.1% to 3%, but also reported increased surface roughness, which could compromise clinical performance.

Overall, these findings suggest that the form, concentration, and method of incorporation directly impact antimicrobial outcomes and may alter surface characteristics. Studies using MIC and MFC assays [19,20] provided more robust and clinically relevant data, whereas those relying mainly on qualitative outcomes [21,22] offered more limited applicability. Notably, the increase in surface roughness observed in some protocols [22] could paradoxically promote microbial colonization, highlighting the importance of optimizing incorporation strategies.

3.3. Mechanical and Surface Properties

3.3.1. Hardness and Surface Roughness

Herla et al. [23] demonstrated that resilient denture coatings with chitosan salts (CS-HCl, CS-G) increased Shore A hardness but also surface roughness. Similarly, Walczak et al. [22] observed that higher chitosan concentrations reduced fungal growth but simultaneously increased roughness. This trade-off is clinically relevant because roughness is associated with microbial adhesion, whereas hardness is desirable for material durability.

3.3.2. Microhardness

Gondim et al. [19] found that the addition of chitosan improved microhardness while maintaining antifungal activity, suggesting dual benefits. Although these results are promising, long-term investigations are needed to confirm whether such effects persist under clinical conditions.

3.3.3. Abrasion Resistance

Wieckiewicz et al. [24] investigated the abrasion resistance of chitosan coatings on PMMA and PET. They reported stable adhesion after sandblasting; however, performance was dependent on the concentration and application method, with PMMA showing less homogeneous coating removal due to wettability issues. These results suggest that abrasion resistance can be enhanced, but uniform application remains a limitation.

3.3.4. General Mechanical Resistance

Adiana et al. [25] reported a significant improvement in the mechanical resistance of PMMA with 1% high-molecular-weight chitosan (79.003 vs. 74.628 MPa). Zaharia et al. [26] corroborated these findings, attributing the improvements to strong chemical bonding and structural reinforcement within the polymer matrix.

3.3.5. Structural and Morphological Alterations

Flores-Ramírez et al. [27] demonstrated that functionalization of chitosan with glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), followed by mixing with PMMA and polybutyl acrylate (PBA), improved thermal stability. This highlights a promising approach for developing PMMA materials with enhanced performance through molecular-level modifications.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the incorporation of chitosan generally improves the mechanical properties of PMMA. However, trade-offs exist: increased hardness and strength are desirable, but higher surface roughness may offset these advantages by facilitating microbial colonization. Among the included studies, those employing chemical functionalization [21,27] yielded more consistent and clinically relevant outcomes than those using physical coatings [22].

4. Discussion

Building upon the patterns and trends identified in the Results section, the incorporation of chitosan into PMMA demonstrates promising yet complex potential, particularly regarding modulating mechanical and antimicrobial properties. This discussion aims to synthesize the collective evidence, highlighting consistencies, elucidating contradictions, and identifying critical knowledge gaps that must be addressed for the eventual clinical translation of chitosan-modified PMMA.

4.1. Antimicrobial Properties: Synthesis of Effects and Unresolved Variables

A consistent trend across the reviewed literature is the demonstrated capacity of chitosan to enhance the antimicrobial properties of PMMA, predominantly against Candida spp. and Streptococcus mutans. This antifungal action is often attributed to chitosan’s polycationic nature, which disrupts cell membranes and inhibits microbial adhesion, as evidenced by studies showing reduced biofilm formation [19] and the inhibition of Candida albicans adhesion to PMMA [20]. However, the precise conditions for optimal antimicrobial efficacy remain unclear, with evident variability in the available results: some studies have reported enhanced antimicrobial activity [19,20], while others observed challenges or even increased microbial proliferation under specific conditions or at higher concentrations [21,22].

This divergence underscores the critical influence f factors such as chitosan’s form (e.g., molecular weight, chemical modification), its concentration, and the specific incorporation method. For instance, the superior performance of chemically grafted chitosan over physically mixed forms highlights the importance of stable integration [21]. At the same time, the increased surface roughness observed alongside antifungal effects suggests potential trade-offs in material properties [22]. Such findings highlight a current knowledge gap regarding the optimal standardized formulation that balances broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity with desirable material characteristics.

4.2. Mechanical Properties: Interpreting Resistance Gains and Surface Compromises

The reviewed evidence generally indicates that the incorporation of CTS can positively influence the mechanical integrity of PMMA. Enhancements in mechanical resistance have been reported, with specific concentrations yielding significant improvements compared with control groups [25]. The functionalization of chitosan to facilitate stronger chemical bonding with PMMA further supports these gains, contributing to improved thermal stability and overall mechanical performance [23,24]. This suggests that chitosan can reinforce the PMMA matrix, particularly when integrated through robust chemical interactions.

Despite these observed improvements, the findings also reveal a consistent challenge related to surface properties. Studies frequently report an increase in surface roughness or compromised wettability when chitosan is incorporated into or coated onto PMMA [22,23]. This suggests a potential inherent trade-off: while chitosan may enhance bulk mechanical properties, existing methods for its incorporation often lead to compromised surface smoothness, which is crucial for patient comfort, hygiene, and long-term material performance in the oral cavity. The effectiveness of a coating, for example, is highly dependent on the application method and concentration, leading to inconsistent outcomes [24]. This inconsistency necessitates a more nuanced approach to development, focusing on strategies that optimize both internal mechanical strength and surface characteristics.

4.3. Clinical Implications: Feasibility of Chitosan Incorporation in Dentures

From a clinical perspective, the in vitro observations of enhanced antimicrobial and mechanical properties present a compelling case for chitosan-modified PMMA in denture applications. The ability to control colonization by Candida albicans and improve material durability could address two significant clinical challenges. Recent studies have demonstrated that incorporating chitosan into PMMA can enhance its antimicrobial and mechanical properties. For instance, Ramamurthy et al. [28] observed a reduction in microbial colonization in chitosan-reinforced PMMA. Similarly, Chander et al. [29] reported improvements in mechanical properties with specific concentrations of chitosan nanoparticles. Additionally, Srimaneepong et al. [30] highlighted the effects of chitosan nanoparticles on the flexural strength and hardness of heat-cured PMMA before and after thermocycling. However, the step from in vitro potential to reliable clinical application remains substantial.

4.4. Limitations and Need for Further Research

Despite its limitations, the present review has several strengths. It provides a systematic summary of the available in vitro evidence, simultaneously addressing both the antimicrobial and mechanical properties of chitosan-modified PMMA. By grouping the findings according to categories of parameters and critically discussing their consistencies and contradictions, this review offers a comprehensive overview that can guide future research and material development.

This scoping review has several limitations. First, the small number of included studies (n = 9) restricts the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Second, considerable methodological heterogeneity was observed regarding the forms (e.g., molecular weight) and concentrations of chitosan, PMMA modification methods, and testing protocols. This variability impedes direct comparisons between studies and underscores the need for standardized methodologies in future research. Third, and most critically, all included studies were conducted in vitro. While valuable for initial characterization, these controlled conditions cannot replicate the complex oral environment, including saliva, enzymatic activity, pH fluctuations, masticatory forces, and diverse biofilms. Consequently, these promising in vitro results cannot be directly extrapolated to the clinical context, highlighting the need for robust in vivo and clinical trials to validate these findings.

Although the included studies did not report significant cytotoxic effects, the potential biocompatibility issues at higher concentrations of chitosan remain unclear. Future investigations should specifically address the cytotoxicity and long-term safety of chitosan-modified PMMA to ensure its clinical applicability. These limitations collectively indicate that while our review identifies promising avenues for the utilization of chitosan-modified PMMA, the current evidence base does not yet permit the formulation of strong clinical recommendations. Future research must prioritize addressing these limitations through standardized methodologies and a clear progression toward in vivo and human clinical trials to validate the observed benefits under real-world conditions.

4.5. Concluding Remarks and Future Recommendations

The collective in vitro evidence suggests that chitosan holds significant potential as an additive to PMMA to improve its antimicrobial and mechanical properties, thereby addressing critical shortcomings of traditional denture materials. However, the available findings are characterized by variability, indicating the need for rigorous, standardized investigations to define optimal concentrations and incorporation methods, as well as to thoroughly characterize both beneficial effects and potential trade-offs (e.g., surface roughness). Future research must progress from standardized in vitro studies to comprehensive in vivo and, ultimately, clinical trials to validate the long-term performance and safety of chitosan-modified PMMA under real-world conditions.

Beyond optimizing chitosan incorporation, a broader perspective on the development of self-disinfecting biomaterials is warranted. Recent studies highlight the role of chitosan as a promising biomaterial in dentistry, demonstrating its antimicrobial efficacy, biocompatibility, and potential to enhance the mechanical properties of resins such as PMMA Fakhri et al. [31]. This suggests that future efforts could explore combining PMMA with other potent antimicrobial molecules, possibly integrating multiple strategies. Such an approach could lead to the development of materials with sustained self-disinfecting properties, reducing the need for constant external hygiene measures by patients. Innovative strategies like these could pave the way for more effective, sustainable, and patient-friendly biomaterials for a wide range of dental applications and implants.

5. Conclusions

The incorporation of chitosan into PMMA has been shown to improve both the antimicrobial and mechanical properties of the resulting materials. Specifically, it enhanced antifungal activity, particularly against Candida albicans, and reduced microbial adhesion to denture surfaces. Mechanical evaluations showed increased microhardness and flexural strength, although the surface roughness and abrasion resistance varied depending on the type and concentration of chitosan, as well as the incorporation method. While these findings suggest potential clinical benefits, the existing evidence remains limited and heterogeneous. Standardized in vitro protocols and well-designed in vivo and clinical studies are required to confirm the long-term performance, safety, and clinical applicability of chitosan-modified PMMA.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/oral5040085/s1.

Author Contributions

D.M.D., Investigation and Writing; L.P.B., Investigation and Writing; L.D.d.A.e.S., Writing—Review and Editing; M.E.d.C.S., Methodology; R.G., Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Brazil, Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the professors and departments of the School of Dentistry at Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, as well as the Federal University of Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, for their valuable support, guidance, and contributions throughout the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| CTS | Chitosan |

| CS-HCl | Chitosan hydrochloride |

| CS-G | Chitosan glutamate |

| GMA | Glycidyl methacrylate |

| PBA | Poly(butyl acrylate) |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| NSC | N-succinyl chitosan |

| LMWC | Low-molecular-weight chitosan |

| HMWC | High-molecular-weight chitosan |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MFC | Minimum fungicidal concentration |

| MAO | Microarc oxidation |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of the PECO search strategy.

Table A1.

Description of the PECO search strategy.

| Participants | In Vitro and Laboratory Studies |

|---|---|

| Exposure | Acrylic resin modified with chitosan |

| Comparison | Absence of chitosan |

| Result/Outcome | Mechanical resistance and antimicrobial activity |

Table A2.

Search strings used.

Table A2.

Search strings used.

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE (via PubMed) | ((Chitosan [MeSH Terms] OR Poliglusam [Title/Abstract] OR Nanoparticles [MeSH Terms]) AND (Removable dentures [Title/Abstract] OR Denture, Partial [MeSH Terms] OR denture base [Title/Abstract] OR acrylic resins [Title/Abstract] OR PMMA [Title/Abstract] OR denture polymer [Title/Abstract] OR polymethyl methacrylate [MeSH Terms] OR acrylic copolymers [Title/Abstract] OR denture base materials [Title/Abstract] OR thermoplastic denture [Title/Abstract] OR thermoplastic resin [Title/Abstract] OR dentures [MeSH Terms] OR Denture, complete [MeSH Terms] OR resin-based composite [Title/Abstract] OR Denture, Partial [MeSH Terms]) AND (Anti-Infective Agents [MeSH Terms] OR Antimicrobial properties [Title/Abstract] OR antimicrobial formulations [Title/Abstract] OR antimicrobial agents [Title/Abstract] OR antimicrobial [Title/Abstract] OR antimicrobial action [Title/Abstract] OR microbiological properties [Title/Abstract] OR antimicrobial effects [Title/Abstract] OR Mechanical Tests [MeSH Terms] OR Mechanical propert* [Title/Abstract] OR tensile strength [MeSH Terms] OR tensile test [Title/Abstract] OR flexural strength [MeSH Terms] OR flexural test [Title/Abstract] OR mechanical characterization [Title/Abstract])) |

| Web Of Science (via Periodicos CAPES) | ((Chitosan OR Poliglusam OR nanoparticles) AND (“Removable dentures” OR “Denture Partial” OR “denture base” OR “acrylic resins” OR PMMA OR “denture polymer” OR “polymethyl methacrylate” OR “acrylic copolymers” OR “denture base materials” OR “thermoplastic denture” OR “thermoplastic resin” OR dentures OR “Denture complete” OR “resin-based composite” OR “Denture Partial”) AND (“Anti-Infective Agents” OR “Antimicrobial properties” OR “antimicrobial formulations” OR “antimicrobial agentes” OR antimicrobial OR “antimicrobial action” OR “microbiological properties” OR “antimicrobial effects” OR “Mechanical Tests”OR “Mechanical propert*” OR “tensile strength” OR “tensile test” OR “flexural strength” OR “flexural test” OR “mechanical characterization”)) |

| VHL | ((Chitosan OR Poliglusam) AND (dentures) AND (Antimicrobial OR microbiological properties OR Mechanical Tests OR Mechanical properties OR tensile strength OR tensile test OR flexural strength OR flexural test)) |

| Scopus (via Periodicos CAPES) | ((Chitosan OR Poliglusam OR nanoparticles) AND (“Removable dentures” OR “Denture Partial” OR “denture base” OR “acrylic resins” OR PMMA OR “denture polymer” OR “polymethyl methacrylate” OR “acrylic copolymers” OR “denture base materials” OR “thermoplastic denture” OR “thermoplastic resin” OR dentures OR “Denture complete” OR “resin-based composite” OR “Denture Partial”) AND (“Anti-Infective Agents” OR “Antimicrobial properties” OR “antimicrobial formulations” OR “antimicrobial agentes” OR antimicrobial OR “antimicrobial action”OR “microbiological properties” OR “antimicrobial effects” OR “Mechanical Tests” OR “Mechanical propert*” OR “tensile strength” OR “tensile test” OR “flexural strength” OR “flexural test” OR “mechanical characterization”)) |

Table A3.

Summary of study selection stages and exclusion criteria.

Table A3.

Summary of study selection stages and exclusion criteria.

| Stage of Selection | Number of Excluded Studies | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract Screening | 1340 |

|

| Full-Text Assessment | 6 |

|

References

- Gad, M.; Abualsaud, R.; Alqarawi, F.; Emam, A.; Khan, S.; Akhtar, S.; Mahrous, A.; Al-Harbi, F. Translucency of nanoparticle-reinforced PMMA denture base material: An in-vitro comparative study. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, R.; Byron, R.; Osborne, P.; West, K. PMMA: An essential material in medicine and dentistry. J. Long Term Eff. Med. Implant. 2005, 15, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, A.; Harijanto, E.; Soebagio. The impact strength of heat-cured acrylic with chitosan nanogel combination. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Abualsaud, R.; Fouda, M.; Rahoma, A.; Al-Thobity, A.; Khan, S.; Akhtar, S.; Al-Harbi, F. Effects of denture cleansers on the flexural strength of PMMA denture base resin modified with ZrO2 nanoparticles. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Torres, L.; Flores-Arriaga, J.; Serrano-Díaz, P.; González-García, I.; Viveros-García, J.; Villanueva-Vilchis, M.; Villanueva-Sánchez, F.; García-Contreras, R.; Arenas-Arrocena, M. Antifungal biomaterial for reducing infections caused by Candida albicans in edentulous patients. Gac. Med. Mex. 2021, 157, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Al-Thobity, A. The impact of nanoparticles-modified repair resin on denture repairs: A systematic review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2021, 57, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhawiatan, A.; Alqutaym, O.; Aldawsari, S.; Zuhair, F.; Alqahtani, R.; Alshehri, T. Evaluation of silver nanoparticles incorporated acrylic light cure resin trays. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12, S173–S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, P. Applications of Nanoparticles in Orthodontics. In Dental Applications of Nanotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sodagar, A.; Bahador, A.; Khalil, S.; Shahroudi, A.; Kassaee, M. The effect of TiO2 and SiO2 nanoparticles on flexural strength of poly(methyl methacrylate) acrylic resins. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2013, 57, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodagar, A.; Kassaee, M.; Akhavan, A.; Javadi, N.; Arab, S.; Kharazifard, M. Effect of silver nanoparticles on flexural strength of acrylic resins. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2012, 56, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Meng, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Chitosan derivatives and their application in biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, R.; Jalan, S. Comparative Evaluation of Flexural Strength of Heat-Polymerized Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Base Material Reinforced with Silanized Aluminium Oxide Nanoparticles and Silanized Tetragonal Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticles—An In Vitro Study. J. Int. Clin. Dent. Res. Organ. 2025, 17, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrahlah, A.; Fouad, H.; Hashem, M.; Niazy, A.A.; AlBadah, A. Titanium Oxide (TiO2)/Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Denture Base Nanocomposites: Mechanical, Viscoelastic and Antibacterial Behavior. Materials 2018, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayiumy, A.; Elsokkary, M. Effect of Adding Chitosan Nanoparticles on Flexural Strength and Hardness of Heat-Cured Acrylic Resin before and after Thermo-Cycling. Egypt. Dent. J. 2023, 69, 3427–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.M.; Abualsaud, R.; Rahoma, A.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Al-Abidi, K.S.; Akhtar, S. Effect of Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticles Addition on the Optical and Tensile Properties of Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Base Material. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, V.; Cascione, M.F.; Toma, C.C.; Albanese, G.; De Giorgi, M.L.; Rinaldi, R. Silver Nanoparticles Addition in Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Dental Matrix: Topographic and Antimycotic Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 15, 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabnia, R.; Ghasempour, M.; Gharekhani, S.; Gholamhoseinnia, S.; Soroorhomayoon, S. Anti-Streptococcus mutans property of a chitosan-containing resin sealant. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondim, B.L.C.; Castellano, L.R.C.; Castro, R.D.; Machado, G.; Carlo, H.L.; Valença, A.M.G.; Carvalho, F.G. Effect of chitosan nanoparticles on the inhibition of Candida spp. biofilm on denture base surface. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 94, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namangkalakul, W.; Benjavongkulchai, S.; Pochana, T.; Promchai, A.; Satitviboon, W.; Howattanapanich, S.; Phuprasong, R.; Ungvijanpunya, N.; Supakanjanakanti, D.; Chaitrakoonthong, T.; et al. Activity of chitosan antifungal denture adhesive against common Candida species and Candida albicans adherence on denture base acrylic resin. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 181.e1–181.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Zhong, B.; Lin, L. Evaluation of chitosan quaternary ammonium salt-modified resin denture base material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 85, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, K.; Schierz, G.; Basche, S.; Petto, C.; Boening, K.; Wieckiewicz, M. Antifungal and surface properties of chitosan-salts modified PMMA denture base material. Molecules 2020, 25, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herla, M.; Boening, K.; Meissner, H.; Walczak, K. Mechanical and surface properties of resilient denture liners modified with chitosan salts. Materials 2019, 12, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weckiewicz, M.; Wolf, E.; Richter, G.; Meissner, H.; Boening, K. New concept of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) surface coating by chitosan. Polymers 2016, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiana, I.; Abidin, T.; Agusnar, H.; Dennis. Effect of adding high molecular nanochitosan on transverse strength of heat-polymerised polymethyl methacrylate denture base resin. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2017, 6, 4996–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, A.; Ghisman, V.P.; Stefanescu, C.L.; Musat, V. Thermal, morphological and structural characterization of chitosan-modified hybrid materials for prosthodontics. Rev. Chim. (Buchar. Orig. Ed.) 2016, 67, 2022–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ramírez, N.; Luna-Bárcenas, G.; Vásquez-García, S.R.; Muñoz-Saldaña, J.; Elizalde-Peña, E.A.; Gupta, R.B.; Sanchez, I.C.; González-Hernández, J.; Garcia-Gaitan, B.; Villasenor-Ortega, F. Hybrid natural-synthetic chitosan resin: Thermal and mechanical behavior. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2008, 19, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, T.; Ahmed, S.; Nandini, V.V.; Boruah, S. Comparison of the antimicrobial efficacy of conventional versus chitosan-reinforced heat-polymerized polymethylmethacrylate dental material: An in vitro study. Cureus 2024, 16, e68856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, N.G.; Venkatraman, J. Mechanical properties and surface roughness of chitosan-reinforced heat-polymerized denture base resin. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2022, 66, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimaneepong, V.; Thanamee, T.; Wattanasirmkit, K.; Muangsawat, S.; Matangkasombut, O. Efficacy of low-molecular-weight chitosan against Candida albicans biofilm on polymethyl methacrylate resin. Aust. Dent. J. 2021, 66, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, E.; Eslami, H.; Marouf, P.; Pakdel, F.; Taghizadeh, S.; Ganbarov, K.; Yousefi, M.; Tanomand, A.; Yousefi, B.; Mahmoudi, S.; et al. Chitosan biomaterials application in dentistry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).