Abstract

Background: Feto-maternal hemorrhages (FMHs) due to placenta disruption and bleeding from fetal maternal circulation can lead to life-threatening fetal anemia. These hemorrhages are more often of small volume and remain unreported. Sensitization to fetal red blood cell (RBC) antigens can occur during pregnancy, at delivery, or after invasive procedures. The sensitized mother produces IgG antibodies (abs) that cross the placenta and cause the hemolysis of fetal RBCs, release of hemoglobin, and increased levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the fetus or neonate. The result is hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). Methods: In this study, we aim to provide a structured overview of RBC alloimmunization in pregnancy. A literature search was conducted using PubMed. English articles published from January 2010 to October 2025 were selected by the authors. The contributing manuscripts focused on managing RBC alloimmunization in pregnancy, FMH screening and quantification, antenatal and postnatal testing, Rh immune globulin (Rh Ig or Anti-D) prophylaxis, and national registry data. Results: Frequencies of RBC abs vary among American, Caucasian, and Asian populations because of genetic diversity, different antibody detection and antibody identification methods, and FMH tests. More specifically, the erythrocyte rosette is a simple screening test for FMH. A positive rosette must be quantified by the Kleihauer–Betke (KB) or flow cytometry (FC). The KB results may be overestimated or underestimated. The advantages of FC include high accuracy, specificity, and repeatability. Ultimately, anti-D prophylaxis protocol varies from country to country. Conclusion: Maternal alloimmunization is an uncommon and highly variable event. Although introducing anti-D prophylaxis has decreased the Rh immunization rate, it is still an unmet medical need. In brief, mitigation strategies for RBC alloimmunization risk include accurate maternal and neonatal testing at different time points, adequate Rh immune globulin prophylaxis in D-negative pregnant women, preventing sensitizing events, adopting a conservative transfusion policy, and upfront ABO and Rh (C/c, E/e) and Kell matching in females under 50 years of age.

1. Introduction

Feto-maternal hemorrhages (FMHs) due to placental disruption can lead to life-threatening fetal anemia or infant deaths. However, this hemorrhaging can be of small volume and remains unreported in the majority of cases [1,2]. Massive FMHs are recognized as a challenging and missed event that may be harmful to the fetus [3].

Antenatal RBC antibody screening is performed to identify pregnancies at risk for HDFN. If maternal antibody (abs) detection is positive, antibody identification is undertaken.

Once a clinically significant antibody is recognized, antibody titers or levels are measured, and this is repeated every 2 to 4 weeks. Antibody titration tests act as a tool to determine when the pregnant woman should be referred to a specialist in maternal–fetal medicine to monitor fetal anemia by measuring the peak blood flow of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) by Doppler ultrasound [4]. The recommended method to perform abs titration is the saline antiglobulin tube test, with a 60 min incubation at 37 °C and anti-IgG reagents [5]. An anemic fetus has decreased blood viscosity and increased blood flow velocity, as measured by color Doppler ultrasonography. Normal ranges and charts are available that show fetal middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocities throughout the second and third trimester. The most important indicator of fetal anemia has been demonstrated to be a threshold of 1.5 multiples of the median (MoM) [6,7]. Among the multiple causes of fetal anemia, the most common is the antibody-mediated destruction of RBCs via maternal alloimmunization. In fact, the red cells are destroyed by macrophages after an antigen–antibody reaction [6].

Sensitizing to fetal RBC antigens, inherited from the father, can occur during late pregnancy or at the time of delivery, after trauma or invasive procedures, or after neoplasms or other causes of bleeding from the fetal to maternal circulation [8]. The minimum volume of fetal RBCs known to immunize pregnant women is 0.1 mL. About 0.1% of women have FMH of more than 30 mL RBCs according to Mollison; about 0.3% of women have more than 30 mL fetal blood according to Sebring et al. [1,2]. The threshold commonly used to define a massive FMH varies from 30 mL to 150 mL, depending on fetal size and gestational age [9].

According to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) green-top guideline no.22, different clinical scenarios may be associated with FMH, such as pregnancy events (abdominal trauma in the third trimester, spontaneous or therapeutic abortion, antepartum hemorrhages); pregnancy complications (ectopic pregnancy, placental abruption, stillbirth, fetal demise); and medical procedures (amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling, cordocentesis, external cephalic version, manual placenta removal) [8,10,11,12]. The mother who is sensitized produces IgG antibodies that cross the placenta. These antibodies may cause the hemolysis of fetal RBCs, release of hemoglobin, and increased levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the fetus or neonate. The result is hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). RBCs destruction starts in utero and causes anemia, liver and spleen enlargement, cardiac failure, jaundice, kernicterus, and even death. The degree of disease severity varies from mild to severe [13,14,15].

2. Materials and Methods

We aim to provide a structured overview of RBC alloimmunization in pregnancy. The contributing manuscripts focused on managing RBC alloimmunization, FMH screening and quantification, antenatal and postnatal testing, Rh immune globulin prophylaxis, and national registry data. A literature search was conducted using Pub Med, and English articles published from January 2010 to October 2025 were selected by the authors using the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords: RBC alloimmunization and pregnancy, HDFN, fetal anemia and middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity, FMH screening and quantification, erythrocyte rosette, Kleihauer–Betke, flow cytometry and fetal hemoglobin or D antigen, FMH and mixed field gel column, antenatal and postnatal testing, Rh immune globulin prophylaxis or Anti-D prophylaxis, pregnancy transfusion, and intrauterine and neonatal transfusion.

3. Results

3.1. RBC Alloimmunization in Pregnancy

The International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) recognizes 48 blood group systems. The most important blood group systems are ABO, Rh, Kell, Kidd, Duffy, and MNS because of their association with clinically significant antibodies [16,17].

There are several donor factors that impact RBC alloimmunization, for example, disease state and “strong responder status”, degree of inflammation, number of transfusions, ethnicity, pregnancies, and drugs. There are also factors intrinsic to the antigens of red blood cells that impact RBC alloimmunization, for example, the density of antigens on red blood cell membranes and immunogenicity, which is estimated as the number of individuals that produce an immune response to a specific molecule [17]. In addition, factors related to the preparation method of red blood cells (for example, washing and irradiation), serologic phenotyping, or process errors also impact RBC alloimmunization.

About 1–3% of the hospital patient population will form alloantibodies according to recent and previous data [18,19]. Patients with hemoglobinopathies and myeloid malignancies receive multiple transfusions and have shown high alloimmunization rates. More specifically, studies have reported alloimmunization rates from 29 to 47% in patients with sickle cell disease and from 5% to 48% in patients with thalassemia, as well as from 3% to 59% in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia [20,21,22,23,24]. Low alloimmunization rates have been reported in patients with lymphoid neoplasms and patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), likely due to immune system derangement [25,26,27].

Anti-D, anti-c, and anti-K are the most common antibodies involved in severe HDFN. Other antibodies frequently associated with HDFN are anti-C, anti-e, anti-E, anti-Fya, and anti-Jka [28]. Multiple alloimmunization causes increased risk for HDFN, especially when anti-D is associated with other antibodies such as anti-D plus-C, anti-D plus-E, anti-c plus-E, anti-K plus Fya, anti-K plus-E, and anti-E plus Jka [29].

Maternal alloimmunization is an uncommon and highly variable event. ABO incompatibility is the most frequent cause of HDFN, and it is generally a mild disease. It is often recognized during the first pregnancy due to the presence of naturally occurring ABO antibodies. Interestingly, ABO incompatibility is responsible for mitigating alloimmunization rates to non-AB antigens [30]. HDFN caused by RhD incompatibility between the fetus and mother is a more severe disease; it is observed after the first pregnancy, as recently reported by Zwiers and colleagues [31,32].

The ABO antibodies are mainly IgM and natural antibodies. IgM is capable of binding complement and causing intravascular hemolysis, but is not capable of crossing the placenta. The Rh system is highly complex and polymorphic and includes more than 50 antigens. These antigens are highly immunogenic proteins. The most important are D, C, c, E, and e. The most immunogenic is the D antigen. The Rh antibodies are mainly IgG, which is capable of crossing the placenta and causing HDFN and inducing hemolytic transfusion reactions [30].

The presence or absence of the D antigen (“Rh positive” and “Rh negative”, respectively) varies according to ethnicity and different molecular mechanisms. Specifically, 8% of Black, 15% of Caucasian, and 1% of Asian individuals are D-negative. Weak D is a serologic D phenotype that may be the result of several mutations, reacting moderately with anti-human globulin. Although the weak D antigen is less immunogenic, it is still capable of causing alloimmunization in D-negative recipients. Similarly, the partial D serologic phenotype that misses a portion of the D antigen can also cause alloimmunization in D-negative recipients. With a widespread availability of the RhD genotype, it is possible to identify RhD gene variants and provide Rh Ig only to those who are at risk of RBC alloimmunization [33].

Because of the high immunogenicity of the D antigen, up to 85% of exposed D-negative individuals will produce anti-D antibodies that will persist in the long term. These antibodies can cause severe HDFN with anemia, hydrops fetalis, and even death. The HDFN incidence has greatly reduced with the prophylactic use of Rh immune globulin, a polyclonal IgG anti-D prepared from human plasma [29].

3.2. FMH Screening and Quantification

The erythrocyte rosette is a simple test to screen for FMHs. It is sensitive to detecting more than 10 mL of fetal whole blood. The fetal cells appear as aggregates or rosettes using a light microscope when the maternal RBCs are treated with anti-D and an indicator. The test may be a false positive if the mother has a variant of the D-antigen or a positive antiglobulin test (DAT) due to autoantibodies; in addition, it may be a false negative if the fetus has a variant of the D-antigen. It cannot be used to analyze FMHs in a D-positive mother or a D-negative mother carrying a D-negative fetus [34].

If the rosette is positive (more than one rosette observed in a low-power field of a light microscope), FMHs should be quantified using the Kleihauer–Betke (KB) test or flow cytometry (FC). The KB test is based on the properties of fetal RBCs, which contain mainly fetal hemoglobin (Hb F) resistant to acid, whereas adult hemoglobin is acid-sensitive. A peripheral blood smear from a maternal blood sample is exposed to acid and stained with hematoxylin. The fetal cells appear a dark pink color, while the maternal blood sample appears pale and “ghost” colored. Variations in the estimation of FMH volume by the KB are documented using different formulas. In addition, the KB test may overestimate FMH in hemoglobinopathies and other hematologic diseases, and it may underestimate FMH for ABO-incompatible pregnancies, advanced gestational age, and overweight pregnant women [34].

The advantages of flow cytometry include high accuracy, specificity, and repeatability. Combined flow cytometry methods using both anti-D and anti-Hb F antibodies may distinguish D-positive from D-negative fetal and maternal cells [34,35,36,37].

Results are presented in KB or FC as the percentage of fetal red cells. The volume of FMH is based on the percentage of fetal RBCs multiplied by the mother’s blood volume, which is about 5000 mL. A 300 mcg dose of Rh Ig is well known to protect against 15 mL of packed RBCs and 30 mL of whole blood [38]. The calculated volume of FMH can be divided by 30 to determine the number of required vials of Rh immune globulin to add.

Interestingly, a mixed-field RBC agglutination (a mixture of agglutinated and unagglutinated RBCs) on the maternal sample may support a diagnosis of massive FMH in the case of feto-maternal ABO/Rh differences in the red blood group [39]. Even if fetal blood transfers of more than 30 mL are clinically significant, they do not correlate with fetal mortality and morbidity. Massive FMHs may be non-specific in symptoms, and they are missed in about 40% of cases, but they may be harmful to the fetus due to its frail compensatory mechanism after bleeding [40].

In the case of mixed-field RBC agglutination, it is of value to obtain a complete differential diagnosis. In fact, mixed-field agglutination may be observed after the transfusion of non-identical ABO/Rh RBC units; hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with major, minor, or bidirected ABO/RhD incompatibility; or a poor-quality sample [41,42,43].

3.3. Antenatal and Postnatal Testing

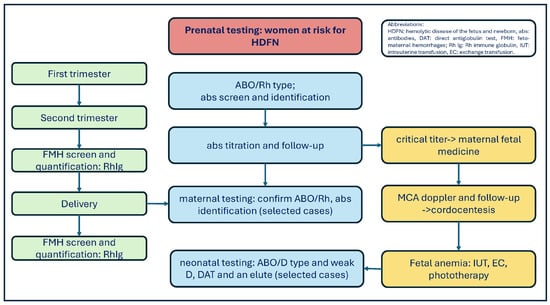

The rationale for prenatal testing includes identifying D-negative pregnant women who are candidates for Rh Ig and confirming D typing at 26 or 28 weeks, identifying pregnant women with antibodies capable of causing HDFN, and performing antibody titration at 2 or 4 weeks until an increase of two dilutions or greater. The saline antiglobulin tube test with a 60 min incubation at 37 °C and anti-IgG reagent is the recommended method to perform antibody titration; a critical titer is considered to be 16 [37]. Antibody titers below critical titers predict mild to moderate HDFN, with the exception of anti-K. A repeated titer of more than 32 is an indication in color Doppler imaging to assess the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV). When fetal anemia becomes moderate to severe, as indicated by Doppler MoM measurements, invasive testing is mandatory. In fact, cordocentesis is performed in such cases to confirm fetal anemia and support hematocrit levels less than 30% via RBC intrauterine transfusion (IUT). Patients with a moderate or severe HDFN require close observation of bilirubin levels at birth to properly start phototherapy and/or exchange transfusion with the aim of reducing maternal antibody levels and improving neonatal anemia [4,6].

Prenatal maternal testing performed in the first trimester consists of ABO and Rh typing, antibody detection/identification, and titration [33]. Postpartum maternal testing consists of ABO- and Rh-typing, FMH screening and quantification, antibody screen (detection), and the identification in selected cases of suspected HDFN. Postpartum neonatal testing consists of ABO- and D-typing to determine anti-D prophylaxis, a weak D test for D-negative typing, DAT, and/or an eluate test (in selected cases of suspected HDFN).

The objectives of the prenatal and postnatal tests are briefly summarized in Figure 1. First of all, it is important to identify RhD-negative pregnant women in their first and second trimesters; secondly, clinically significant alloantibodies must be identified and monitored as early as possible during pregnancy, and information must be provided to the obstetrician. Thirdly, the Rh type of infants born to Rh-negative mothers must be determined, and postpartum FMH must be quantified. Ultimately, it is important to transfuse the affected fetus or newborn and pregnant woman with appropriate RBC units [38].

Figure 1.

Prenatal testing for women at risk for HDFN and fetal anemia.

3.4. Rh Immune Globulin Prophylaxis

The mechanism of Rh immune globulin prophylaxis has not been completely clarified [44]. In addition, administering Rh immune globulin (Rh Ig) is recommended for sensitizing events, during the antepartum and postpartum period; however, the administration procedure varies between the United States of America, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia. FMH studies are performed worldwide after the postpartum period [15], and Rh immune globulin must be injected intravenously or intramuscularly according to the product label [45,46].

A dose of 50 micrograms (mcg or 250 IU) or 120 mcg (600 IU) of Rh Ig is recommended in the majority of countries before 12 weeks of gestation. Before this period, the total fetal blood volume is estimated to be less than 5 mL.

A dose of 120/125 mcg (600/625 IU) or 300 mcg (1500 IU) is suggested after 12 weeks of gestation in the United Kingdom/Australia and Canada and the US, respectively. A dose of 300 mcg of Rh immune globulin is recommended in all countries after 28 weeks of gestation, while a two-dose administration of 125 and 120 mcg at 28 weeks and 34 weeks is suggested in British and Australian guidelines. The two-dose option is also indicated in the Canadian guidelines [15]. At present, there is no trial comparing single-dose and two-dose schedules of Rh immune globulin.

In the majority of countries, a full dose of Rh Ig is recommended 72 h to 10 days after delivery. In addition, the English guidelines suggest a postpartum dose of 100 mcg (500 IU), while the Australian guidelines suggest FMH quantification to select an appropriate dose of Rh immune globulin [15].

3.5. Registry Data

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on alloimmunized singleton pregnancies in Stockholm between 1996 and 2016. Of the 1724 alloimmunized pregnancies, 1079 were at risk for HDFN. Anti-D was detected in 492 (46%) pregnancies, followed by anti-E in 161 (15%) and anti-c in 128 (12%). A total of 8% of pregnancies had intrauterine blood transfusion (IUT), with the highest pregnancy risk affected by anti-D combined with one or two antibodies. The majority of cases treated with IUT had a titer of 64 or above, except for two pregnancies of a woman with anti-c. In addition, Swedish guidelines recommend surveillance with MCA Doppler evaluation in both cases of a titer of 8 for anti-c and anti-Kell [42]. Ultimately, neonatal treatments (phototherapy and exchange transfusions) were most commonly reported in the anti-D and anti-D combined group [47].

Utilizing data from national health registries, a patient-based cohort study of more than 25,000 single pregnancies at risk for HDFN was conducted in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark between January 2000 and December 2021. Compared to non-HDFN neonates, those who received IUT and neonatal transfusion had a lower gestational age, higher rates of neonatal unit admission, and were most commonly diagnosed with growth and neurological disorders [48].

Interestingly, RBC abs were identified in a large database in the USA from 2010 to 2021. Among 10 million pregnancies, comprising 14.4% of all pregnancies, 1.5% screened positive for red blood cell antibodies. An estimated prevalence of 1518 of 100,000 pregnancies was documented. Among these data, three-quarters of RBC antibodies demonstrated a high risk for HDFN according to the 2015 Swedish national guidelines. RBC abs detection and identification were performed using solid-phase technology. Abs titers were determined using the hemagglutination technique, performed in a tube without potentiating agents as a reciprocal of the lowest dilution at which agglutination was macroscopically noted. However, the prevalence of anti-D was difficult to interpret, making alloimmunization difficult to distinguish from passive immunity. Anti-D remains second to anti-K. Anti-K is well known to suppress fetal erythropoiesis by targeting red blood progenitor cells and can induce red blood cell hemolysis and earlier severe anemia [49]. More specifically, anti-D (568/100,000), anti-K (68/100,000), and anti-c (29/100,000) were mainly recognized among high-risk HDFN according to the 2015 Swedish guidelines.

The estimated prevalence of RBC abs was consistent with that of previous rates from a single center in the USA. This prevalence is higher than that of other countries (for example, Sweden, Norway, Australia, and Canada), likely due to genetic diversity, prenatal antibody screening, the survival of congenital hemoglobinopathies, and advanced maternal age [50].

Among 18,010 Chinese pregnant women admitted to the Dongguan Maternal and Children Health Hospital in South China, from January 2021 to February 2023, 121 cases with irregular red blood cell antibodies were noted (0.67%). In total, 25 pregnant women with passively acquired Anti-D were excluded from the analysis. Irregular RBC antibodies were observed in 28 primigravida mothers and 93 women with a history of multiple pregnancies, distributed principally in the Rh, MNS, and Kidd blood group systems. For primigravida women and women with a history of multiple pregnancies, a red blood cell antibody detection and panel for antibody identification was performed by gel antiglobulin tests. The difference in the percentage of pregnant women with irregular RBC antibodies between the two groups was statistically insignificant. Interestingly, Mur and Dia were included in the antigenic profile of reagent RBCs used for performing antibody screens and identification in Chinese women. More specifically, anti-Mur and anti-Dia were observed in nine cases and one case, respectively [51].

4. Discussion

Interestingly, ABO incompatibility is responsible for mitigating alloimmunization to non-AB antigens [30]. RhD alloimmunization incidence was shown to decrease from 16% to 2% after antenatal Rh Ig prophylaxis and from 2% to 0.2% after its postpartum administration [5,42]. Rh immune globulin has significantly reduced the prevalence of RhD HDFN, although differences remain between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. Rh disease still results in perinatal death and disability [51,52,53,54,55].

Rh Ig is of no benefit once a person has been actively immunized and has formed anti-D. Rh Ig is not suggested for the mother if the infant is found to be D-negative. In rare cases, the infant’s RBCs can be covered by maternal immune anti-D, causing a false negative Rh type, “blocked Rh phenomenon”. In such cases, an eluate obtained from an infant’s RBC may reveal anti-D [56].

American registry data suggest useful risk mitigation strategies for RBC alloimmunization in pregnancies; for example, a national blood donor database contains information on genotype patients with serologically weak/variant D and adopts a prophylactic antigen matching for RhD, Rh c, and Kell in women aged < 50 years, optimizing preoperative hemoglobin levels [55,56]. The prevalence of alloimmunization in some subgroups of patients, such as those with thalassemia and SCD, can be as high as 30–40%. The reasons for this high rate are not fully clarified; possible explanations include multiple RBC transfusions during acute inflammatory events and Rh variant epitopes in Black individuals [57].

Asian registry data underlines the importance of rare red blood group and adequate RBC reagents to identify antibodies and select appropriate RBC units [50,58]. Interestingly, the Scandinavian registry supports further studies to monitor patients who received IUT and neonatal transfusions in order to reduce the burden of patients with growth and neurological disorders [50].

5. Conclusions

Maternal RBC alloimmunization is an uncommon and highly variable event. Frequencies of RBC abs vary among populations because of genetic diversity, methods for antibody detection and identification, transfusion products, and technological resources. Finally, it is important to conduct proper history-taking, using a multidisciplinary approach and clear communication between blood banks and clinicians [59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M., L.C. and V.C.E.C.; writing—review and editing, P.M., L.C., V.C.E.C., A.F. (Antonietta Faleo), A.F. (Antonietta Ferrara), L.S. and L.P.; supervision, T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the team of Immunohematology and Transfusion Medicine, Policlinico Riuniti Foggia; Rosario Magaldi, Neonatologist; and Libera Elvira Maria Schiavone, Clinical Pathologist, for their valuable comments. The authors thank the Peer Reviewers and Editorial Board of the journal for their excellent assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mollison, P.L. Quantitation of transplacental haemorrhage. Br. Med. J. 1972, 3, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebring, E.S.; Polesky, H.F. Fetomaternal hemorrhage: Incidence, risk factors, time of occurrence, and clinical effects. Transfusion 1990, 30, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroustrup, A.; Plafkin, C.; Savitz, D.A. Impact of physician awareness on diagnosis of fetomaternal hemorrhage. Neonatology 2014, 105, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari, G.; Deter, R.L.; Carpenter, R.L.; Rahman, F.; Zimmerman, R.; Moise, K.J., Jr.; Dorman, K.F.; Ludormirsky, A.; Gonzalez, R.; Gomez, R.; et al. Noninvasive diagnosis by Doppler ultrasonography of fetal anemia due to maternal red-cell alloimmunization. Collaborative Group for Doppler Assessment of the Blood Velocity in Anemic Fetuses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, W.J.; Scientific Section Coordinating Committee of the AABB. Practice guidelines for prenatal and perinatal immunohematology, revisited. Transfusion 2001, 41, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelman, J.; Gurney, L.; Kibly, M.; Morris, R.K. Identification and management of fetal anemia: A practical guide. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 23, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, N.; Johnson, J.A.; Ryan, G. Fetal anemia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, H.; Massey, E.; Kirwan, D.; Davies, T.; Robson, S.; White, J.; Jones, J.; Allard, S. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus. Med. 2014, 24, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kecskes, Z. Large Fetomaternal Hemorrhage: Clinical Presentation and Outcome. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003, 13, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, F.; Veale, K.; Robinson, F.; Brennand, J.; Massey, E.; Qureshi, H.; Finning, K.; Watts, T.; Lees, C.; Southgate, E.; et al. Guidelines for the investigation and management of red cell antibody in pregnancy. A British Society for Haematology Guideline. Transfus. Med. 2025, 35, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, L.; Walsh, C.M.; Barty, R.; Callum, J.; Yan, M.T.S.; VanderMeulen, H.; Robitaille, N.; Fung, K.F.K.; Ng, E.; Hume, H.; et al. Guidance for Prenatal, Postnatal, and Neonatal Immunohematology Testing in Canada: Consensus Recommendations from a Modified Delphi Process. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2025, 47, 103088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, L.; Clarke, G. Canadian Consensus for Prenatal, Postnatal, and Neonatal Immunohematology Testing: A Need for Improved Guidance. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2025, 47, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haas, M.; Thurik, F.F.; Koelewijn, J.M.; van der Schoot, C.E. Haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Vox Sang. 2015, 109, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, J.E.; Delaney, M. Hemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn: Modern Practice and Future Investigations. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2016, 30, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, J.D.; Dahlke, J.D.; Sutton, D.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Chauhan, S.P. Prevention of RhD Alloimmunization: A comparison of four national guidelines. Am. J. Perinatol. 2018, 35, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, G. Human Blood Groups, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Science: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, M.E.; Lomas-Francis, C.; Olsson, M.L. The Blood Group Antigens Factsbook; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson, J.E.; Tormey, C.A. Understanding red blood cell alloimmunization triggers. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2016, 2016, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, J.L.; Pineda, A.A.; Gorden, L.D.; Bryant, S.C.; Melton, L.J., 3rd; Vamvakas, E.C.; Moore, S.B. RBC alloantibody specificity and antigen potency in Omsted country, Minnesota. Transfusion 2001, 41, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeltge, G.A.; Domen, R.E.; Schaffer, P.A. Multiple red cell transfusions and alloimmunization. Experience with 6996 antibodies detected in a total of 159,262 patients with 1985 to 1993. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1995, 119, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, C.D.; Su, L.L.; Hillyer, K.L.; Hillyer, C.D. Transfusion in the patient with sickle cell disease: A critical review of the literature and transfusion guidelines. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2007, 21, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteocci, A.; Pierelli, L. Red blood cell alloimmunization in sickle cell disaese and thalassemia: Current status, future perpectives and potential role of molecular typing. Vox Sang. 2014, 106, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, G.L.; Vassanelli, A.; De Franceschi, L.; Marson, P.; Lisi, R.; Ostuni, A.; Giagante, A.; OIriga, R.; Fiorin, F. Transfusion strategies in thalassemia and sickle cell disease SITE-SIMTI-SIdEM Good Practice. Blood Transfus. 2025, 23, 536–554. [Google Scholar]

- Guelsin, G.A.; Rodrigues, C.; Visentainer, J.E. Molecular matching for Rh and K reduces red cell red cell alloimmunisation in patients with myelodyplastic syndrome. Blood Transfus. 2015, 13, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfriend, H.; Walewska, I. Analysis of immune response to red blood cell antigens in multitrasfused patients with different diseases. Mater. Med. Pol. 1990, 22, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg, N.; Peck, K.; Ross, K. Immune response to chronic red blood cell transfusion. Vox Sang. 1983, 44, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boctor, F.N.; Ali, N.H.; Mohandas, K.; Uehlinger, J. Absence of D-alloimmunization in AIDS patients receving mismatched RBCs. Transfusion 2003, 43, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denise, M. Detection and identification of antibodies. In Harmening, Modern Blood Banking and Transfusion Practices, 7th ed.; F.A. Davis Company Publication: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Denise, M. Haemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn (HDFN). In Harmening, Modern Blood Banking and Transfusion Practices, 7th ed.; F.A. Davis Company Publication: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zwiers, C.; Koelewijn, J.M.; Vermij, L.; Sambeeck, J.v.; Oepkes, D.; de Haas, M.; van der Schoot, C.E. ABO incompatibility and Rh Ig immunoprophylaxis protect against non-D alloimmunization by pregnancy. Transfusion 2018, 58, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denise, M. The Rh blood group system. In Harmening, Modern Blood Banking and Transfusion Practices, 7th ed.; F.A. Davis Company Publication: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zwiers, C.; Slootweg, Y.M.; Koelewijn, J.M.; Ligthart, P.C.; van der Bom, J.G.; Van Kamp, I.L.; Lopriore, E.; van der Schoot, C.E.; Oepkes, D.; de Haas, M. Disease severity in subsequent pregnancies with RhD immunization: A nationwide cohort. Vox Sang. 2024, 119, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, S.G.; Flegel, W.A.; Westoff, C.M.; Denomme, G.A.; Delaney, M.; Keller, M.A.; Johnson, S.T.; Katz, L.; Queenan, J.T.; Vassallo, R.R.; et al. It’s time to phase RhD genotyping for patients with a serologic weak phenotype. College of American Pathologist Transfusion Medicine Resource Committee Work Group. Transfusion 2015, 55, 680–689. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.A.; Makar, R.S. Detection of fetomaternal hemorrhage. Am. J. Hematol. 2012, 87, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, J.; Orellana, D.; Chen, L.S.; Russell, M.; Khoo, T.-L. The presence of F Cells with a Fetal Phenotype in Adults with Hemoglobinopathies Limits the Utility of Flow Cytometry for Quantitation of Fetoimaternal Hemorrhage. Cytom. B Clin. Cytom. 2018, 94, 695–698. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjaj, O.I.; Callum, J.; Shehata, N.; Farrell, A.; Clarke, G.; Lieberman, L. Laboratory assessment of fetomaternal haemorrhage and Rh immune globulin management: Canadian practice and scoping review. Br. J. Haematol. 2025, 207, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Liu, T. Overview of detection methods of fetomaternal haemorrhage. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1445757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delay, M.; Sveensson, A.; Lieberman, L. Perinatal Issues in Transfusion Practice, 19th ed; Fung, M.K., Eder, A.F., Spitalnik, S.L., Westhoff, C.M., Eds.; Technical Manual; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 23, pp. 599–611. [Google Scholar]

- Bonstein, L.; Khaldi, H.; Dann, E.J.; Weiner, Z.; David, C.B.; Solt, I. Routine maternal ABO/Rhesus D blood typing can alert of massive fetomaternal haemorrhage. Vox Sang. 2024, 119, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, N.R.; Henry, E.; Bahr, T.M.; Ohls, R.K.; Page, J.M.; Ilstrup, S.J.; Christensen, R.D. Fetomaternal hemorrhage: Evidence from a multihospital healthcare system that up to 40% of severe cases are missed. Transfusion 2022, 62, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matteocci, A.; Pierelli, L. Immuno-Hematologic Complexity of ABO-Incompatible Allogeneic HSC Transplantation. Cells 2024, 13, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennardello, F.; Coluzzi, S.; Curciariello, F.; Todros, T.; Villa, S.; Italian Society of Transfusion Medicine and Immunohaematology (SIMTI) and Italian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (SIGO) Working Group. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of haemolytic disease of the foetus and newborn. Blood Transfus. 2015, 13, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collodel, L.; Tidore, G.; Perali, G.; Carobolante, F.; Skert, C.; Gessoni, G. Transmission of an Anti-RhD Alloantibody from Donor to Recipient After an Haploidentical ABO Compatible Peripherical Blood Stem Cells Transplant. Int. Blood Res. Rev. 2021, 16, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Valentini, B.; Zegarra, R.R.; Ghi, T.; Dall’Asta, A. Red blood cell alloimmunization and pregnancy: Diagnosis and management. Pregnancy 2025, 1, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinc, D.; Lazarus, A.H. Mechanisms of anti-D action in the prevention of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Hematology. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2009, 16, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, H.; Lloyd-Jones, M.; Rees, A. Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for RhD negative women: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2009, 13, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liumbruno, G.M.; D’Alessandro, A.; Rea, F.; Piccinini, V.; Catalano, L.; Calizzani, G.; Puppella, S.; Grazzini, G. The role of antenatal immunoprophylaxis in the prevention of maternal-foetal anti-Rh (D) alloimmunization. Blood Transfus. 2010, 8, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Ajne, G.; Wikman, A.; Lindqvist, C.; Reilly, M.; Tiblad, E. Management and clinical consequences of red blood cell antibody in pregnancy: A population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 2216–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, K.H.M.; Gissler, M.; Thunbo, M.Ø.; Hsia, E.; Tjoa, M.L.; Liu, S.; Almgren, M.; Stafanovic, V.; Pedersen, L.H.; Wikman, A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnancies at-risk of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark: A population-based register study. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2025, 5, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugrue, R.P.; Moise, K.J.; Federspiel, J.J.; Abels, E.; Louie, J.Z.; Chen, Z.; Bare, L.; Alagaia, D.P.; Kaufam, H.W. Maternal red blood cell alloimmunization prevalence in the United States. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 4311–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, Y.; Guo, G.; Xie, R.; Wu, Y. Comparison of the detection rate and specificity of irregular red blood cell antibodies between first-time pregnant women and women with a history of multiple pregnancies among 18,010 Chinese women. J. Pregnancy 2024, 2024, 5539776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, K.J. Red blood cell alloimmunization in pregnancy. Semin. Hematol. 2005, 42, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegoraro, V.; Urbinati, D.; Visser, G.H.A.; Di Renzo, G.C.; Zipursky, A.; Stotler, B.A.; Spitalnik, S.L. Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn due to Rh(D) incompatibility: A preventable disease that still produces significant morbidity and mortality in children. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, G.H.A.; Thommensen, T.; Di Rienzo, G.C.; Naasar, A.H.; Spitalnik, S.L. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: A call to action. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 152, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, C.; Esmaeilisaraji, L.; Thuku, M.; Michaud, A.; Sikora, L.; Fung-Kee-Fung, K. Antenatal and postpartum prevention of Rh alloimmunization: A systematic review and GRADE analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. Blocked D phenomenon. Blood Transfus. 2023, 11, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, K.; Fasano, R.M.; Karafin, M.S.; Hendrickson, J.E.; Francis, R.O. Mechanisms of alloimmunization in sickle cell disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2019, 26, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, S.; Revelli, N.; Baluce, B. A new blood group system: Scientific relevance and media resonance. Blood Transfus. 2022, 20, 441–442. [Google Scholar]

- Koelewijn, J.M.; de Haas, M.; Vrijkotte, T.G.; van der Schoot, C.E.; Bonsel, G.J. Risk factors for RhD immunisation despite antenatal and postnatal anti-D prophylaxis. BJOG 2009, 116, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandone, E.; Cromi, A.; Vinciguerra, M.; Tiscia, G.L.; Makatasriya, A.; Khizroeva, J.; Bitsadze, V.; De Laurenzo, A.; Colaizzo, D.; Sciannamè, N.; et al. Perinatal outcome in pregnant women: The impact of blood transfusion. Blood Transf. 2025, 23, 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- DelBaugh, R.M.; Murphy, M.F.; Staves, J.; Fachini, R.M.; Wendel, S.; Hands, K.; Bonet-Bub, C.; Kutner, J.M.; Cohn, C.S.; Cox, C.A.; et al. Why do people still make anti-D over 50 years after the introduction of Rho(D) immune globulin? A Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative study. Transfusion 2025, 65, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, M.C.; Souter Sc Zipkin, R.J.; Ackerman, M.E. Current insight into K-associated fetal anemia and potential treatment strategies for sensitized pregnancies. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2024, 78, 150779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, G.; Tormey, C.A. Estimating the immunogenicity of blood group antigens: A modified calculation that corrects for transfusion exposures. Br. J. Hematol. 2016, 175, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattizzo, B.; Bortolotti, M.; Fantini, N.N.; Glenthoj, A.; Michel, M.; Napolitano, M.; Raso, S.; Chen, F.; McDonald, C.; Murakhovskaya, I.; et al. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia during pregnancy and puerperium: An international multicenter experience. Blood 2023, 141, 2016–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Ziman, A.; Yan, M.T.S.; Waters, A.; Virk, M.S.; Tran, A.; Shih, A.w.; Scally, E.; Raval, J.S.; Pandey, S.; et al. Serologic reactivity of unidentified specificity in antenatal testing and hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn: The BEST collaborative study. Transfusion 2023, 63, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.