Abstract

Background/Objectives: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have transformed the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), yet emerging evidence indicates an increased risk of vascular adverse events, particularly peripheral artery disease (PAD). Reliable biomarkers for early detection of TKI-related vascular toxicity are still lacking. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 78 patients with chronic-phase CML treated at Dr. Soetomo General Hospital, Surabaya. PAD was confirmed using ankle–brachial index. Serum oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) levels were measured using ELISA. Results: PAD was detected in 20% of subjects. The PAD group showed significantly higher OxLDL, lower IL-10, and a markedly elevated OxLDL/IL-10 ratio (all p < 0.001). OxLDL remained independently associated with PAD after adjustment (adjusted OR = 1.132, 95% CI 1.020–1.255, p = 0.019). OxLDL/IL-10 ratio yielded a good diagnostic value (sensitivity 87.5% and specificity of 88.7%). Conclusions: Elevated OxLDL and an increased OxLDL/IL-10 ratio are associated with PAD in CML patients receiving TKI therapy and demonstrated a good diagnostic performance for early detection of TKI-induced vascular toxicity.

1. Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a type of hematologic malignancy characterized by the formation of the BCR::ABL1 oncogene on the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), resulting from a reciprocal chromosomal translocation t(9;22), which leads to the fusion of the BCR::ABL1 oncogene [1,2]. Only 50–60% of CML patients receiving first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), imatinib, achieve the therapeutic milestones [3]. Second- and third-generation TKIs provide improved molecular response rates. However, these agents, such as dasatinib, nilotinib, and ponatinib, have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular toxicity [4,5].

Existing hypotheses suggest that atherosclerosis plays a key role in the pathogenesis of TKI-induced vascular adverse events (VAE) [6]. The most commonly used term is Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD). Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is impaired peripheral perfusion detected by an abnormal ankle–brachial index (ABI ≤ 0.90), which reflects functional or early atherosclerotic changes. In contrast, peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) refers to advanced disease with hemodynamically significant arterial obstruction, typically confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography showing ≥50% luminal stenosis [7]. Nilotinib was the first TKI linked to occlusive peripheral artery disease [8,9]. The reported frequency of PAD varies widely between 1–29% over a two-year evaluation period [10]. This variation is due to differences in the types of TKIs studied, definitions of VAE, study populations, and data collection methods (whether clinical or imaging studies) [11,12].

Timely diagnosis is essential for effective management of peripheral artery disease (PAD). However, the current standard for PAD detection, which is Doppler ultrasonography, has several limitations. Its accuracy is highly operator-dependent, and in many resource-limited settings, access to Doppler examinations is constrained, often resulting in long waiting times and delayed treatment initiation. Moreover, this method is not ideal for routine monitoring of vascular adverse effects in patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), as it is time-consuming and impractical for repeated screening. Another method for detecting PAD is the ankle–brachial index (ABI), which, although simpler to perform, is often less reliable and less sensitive. Currently, no reliable biomarkers exist to facilitate early detection or monitoring of TKI-related cardiovascular toxicity. Instead, clinicians often rely on traditional cardiovascular risk scores developed for the general population, which are inadequate for accurately assessing the true risk profile in CML patients treated with TKIs [13]. Therefore, a more reliable parameter for screening cardiovascular toxicity in patients receiving TKI therapy is imperative.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between serum levels of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL and interleukin-10 (IL-10) with the occurrence of peripheral artery disease (PAD), as assessed by ankle–brachial index (ABI) measurement in patients with chronic-phase CML receiving either imatinib or nilotinib therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was an analytical observational cross-sectional study conducted at the Hematology-Oncology Clinic, Dr. Soetomo General Hospital, Surabaya, between August and November 2025.

2.2. Study Subjects

The study enrolled patients with chronic-phase BCR::ABL1–positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Inclusion criteria were: (1) males aged 18–70 years and premenopausal females aged >18 years; (2) confirmed CML in chronic phase receiving imatinib or nilotinib therapy for at least 12 months; and (3) provision of written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: impaired renal function (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), chronic liver disease, coronary artery disease, stroke, uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension, chronic inflammatory or acute infectious conditions, antioxidant or anti-inflammatory drug use, and damaged or insufficient blood samples.

Sampling was conducted using non-proportional random sampling with a purposive approach. All patients attending the clinic during the study period who met the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited to participate until the minimum required sample size was achieved. The minimum required sample size was estimated using the classical conservative rule of at least 10 outcome events per variable (EPV) for multivariable analysis.

The sample size was calculated using the following formula:

where:

= number of independent variables (2: oxLDL and IL-10).

= proportion of outcome events (prevalence of PAD at Adam Malik Hospital = 29.1%, approximated to 0.30).

Thus, the minimum required sample size was 67 subjects.

After giving informed consent, patients underwent clinical assessment, blood sampling (10 mL, non-fasting, 07:00–10:00), and ankle–brachial index (ABI) evaluation for peripheral artery disease (PAD). Serum samples were analyzed for OxLDL and IL-10 levels at the Prodia Clinical Laboratory. Data were tabulated in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS software.

2.3. Ankle Brachial Index

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was assessed using ankle–brachial index (ABI), following the recommendations of the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF). ABI was calculated by dividing the highest ankle systolic pressure (posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis artery) by the highest brachial systolic pressure. Interpretation was as follows: 1.40 = non-compressible; 1.00–1.40 = normal; 0.91–0.99 = borderline; 0.40–0.90 = mild–moderate PAD; <0.40 = severe PAD.

2.4. Measurement of Serum OxLDL

Serum oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) concentrations were measured using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the Mercodia Oxidized LDL ELISA Kit (Catalog No. 10-1143-01, Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The assay utilizes the monoclonal antibody 4E6, which specifically recognizes oxidatively modified ApoB. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the color intensity—proportional to the OxLDL concentration—was read at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer. Serum samples were stored at 2–10 °C (for ≤2 weeks) or −20 °C to −80 °C (for long-term storage). All samples were analyzed in duplicate.

2.5. Measurement of Serum IL-10

Serum interleukin-10 (IL-10) levels were quantified using the Quantikine High Sensitivity Human IL-10 ELISA Kit (Catalog No. HS100C, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standards and serum samples were incubated in microplates pre-coated with IL-10–specific antibodies, followed by the addition of an HRP-conjugated detection reagent and TMB substrate. The reaction was stopped using 2N sulfuric acid, and absorbance was read at 450 nm with wavelength correction at 540–570 nm. Serum IL-10 concentrations (pg/mL) were calculated by interpolation from a standard curve.

2.6. Statistics

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were presented as median (minimum–maximum), while categorical variables were summarized as frequency and percentage. Data normality was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Since most variables were not normally distributed, differences between groups were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data, as appropriate.

The diagnostic accuracy of serum OxLDL, IL-10, and the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio for detecting peripheral artery disease (PAD) was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated, and the optimal cutoff values were determined using Youden’s Index (J = sensitivity + specificity − 1).

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to control for potential confounders, including age and smoking status, with PAD status as the dependent variable. Results were expressed as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. The model’s goodness of fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and overall model performance was evaluated using the Nagelkerke R2 statistic. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

A total of 78 subjects were included in the analysis, comprising 16 subjects diagnosed with PAD confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography and 62 subjects without PAD. The distribution of baseline characteristics, including sex, comorbidities, duration of CML, and type of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), was comparable between groups. However, the PAD group was significantly younger than the non-PAD group (p < 0.05). In addition, smoking status differed significantly between groups, with a higher proportion of smokers observed in the PAD group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

3.2. OxLDL and IL-10

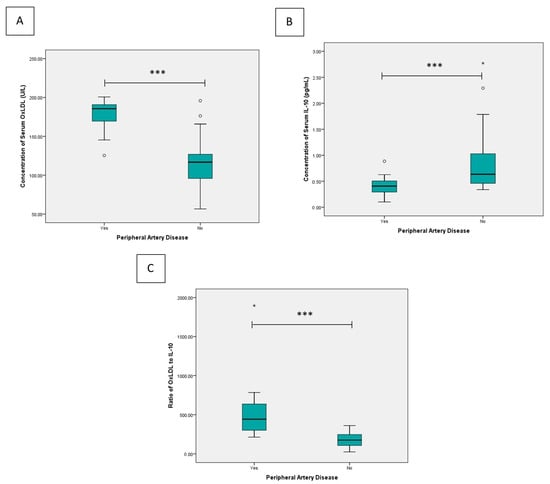

The comparison of serum biomarkers between subjects with and without PAD demonstrated significant differences across all measured parameters (Figure 1). The median concentration of serum OxLDL was markedly higher in the PAD group (185.64 U/L, range 125.33–200.70) compared to the non-PAD group (116.76 U/L, range 56.62–195.82; p < 0.001). Conversely, the median serum IL-10 concentration was lower among PAD subjects (0.41 pg/mL, range 0.10–0.89) than in those without PAD (0.63 pg/mL, range 0.34–2.77; p < 0.001). The OxLDL/IL-10 ratio was substantially elevated in the PAD group (median 442.14, range 213.99–1897.23) compared to the non-PAD group (median 175.80, range 25.55–361.34; p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of (A) serum OxLDL concentration, (B) serum IL-10 concentration, and (C) the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio between groups. Statistical differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. Outlier are shown as circles.

Because the subject characteristics were not balanced for age and smoking status (p < 0.05), a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for these potential confounders. In this model, PAD status was entered as the dependent variable, while OxLDL, IL-10, age, and smoking were included as covariates. The results demonstrated that OxLDL remained independently associated with PAD after adjustment (adjusted OR = 1.132 per U/L, 95% CI = 1.020–1.255, p = 0.019), whereas IL-10 did not reach statistical significance (adjusted OR ≈ 0, 95% CI = 0.000–2.134, p = 0.064). Age was inversely associated with PAD (adjusted OR = 0.815 per year, 95% CI = 0.672–0.988, p = 0.038), and current smoking showed a strong but imprecise association (adjusted OR = 29.317, 95% CI = 1.036–829.450, p = 0.048), likely reflecting the limited number of smokers or outcome imbalance. The overall model demonstrated excellent explanatory power (pseudo-R2 = 0.897) and good calibration according to the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (p = 0.999).

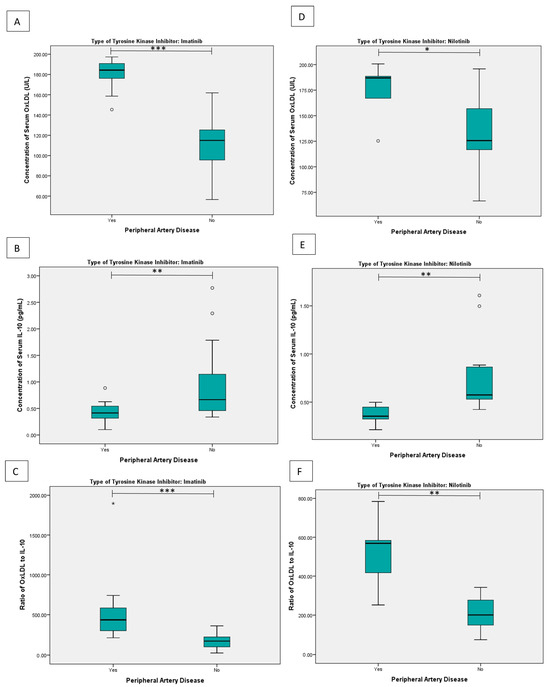

Subgroup analysis based on the type of tyrosine kinase inhibitor showed a similar pattern for both imatinib and nilotinib (Figure 2). Among patients receiving imatinib, the median OxLDL concentration was significantly higher in those with PAD (184.31 U/L [range 145.34–197.29]) compared to those without PAD (114.93 U/L [56.62–161.88], p < 0.001). Conversely, IL-10 levels were significantly lower in patients with PAD (0.42 pg/mL [0.10–0.89] than in those without PAD (0.67 pg/mL [0.34–2.77], p = 0.004). Consequently, the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio was markedly higher in patients with PAD (435.90 [213–1897]) compared to those without PAD (172.06 [25.55–361.34], p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Subgroup comparative analysis based on the type of TKI: (A) serum OxLDL concentration, (B) serum IL-10 concentration, and (C) the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio in patients receiving imatinib; (D) serum OxLDL concentration, (E) serum IL-10 concentration, and (F) the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio in patients receiving nilotinib. Statistical differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Outlier are shown as circles.

A similar pattern was observed in patients treated with nilotinib. Patients with PAD had significantly higher OxLDL levels (186.98 U/L [125.33–200.70]) than those without PAD (125.66 U/L [66.63–195.82], p = 0.025), along with significantly lower IL-10 concentrations (0.35 pg/mL [0.21–0.50] in those with PAD and 0.57 pg/mL [0.42–1.61] in those without PAD, p = 0.002). Accordingly, the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio was significantly higher in patients with PAD (568.56 [251–784]) compared to those without PAD (200.95 [75.29–341.88], p = 0.002).

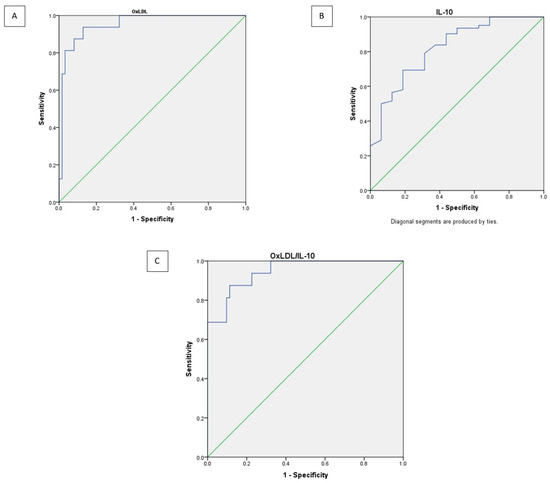

3.3. Diagnostic Value

The ROC analysis showed that all three biomarkers had meaningful diagnostic power for distinguishing PAD from non-PAD. Among them, OxLDL and the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio performed exceptionally well, each showing excellent discrimination based on their very high AUC values (Figure 3). IL-10, while still significant, demonstrated a more modest ability to separate the two groups.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating curve analysis of OxLDL (A), IL-10 (B), and OxLDL/IL-10 ratio (C) as shown as purple lines. Diagonal segments (green line) are produced by ties.

The cutoff values for each biomarker were determined using Youden’s Index, which helps identify the point that best balances sensitivity and specificity (Table 2). Based on this method, an OxLDL level above 144.13 U/L was found to most accurately distinguish patients with PAD, showing high sensitivity (93.8%) and specificity (87.1%). For IL-10, the optimal threshold was below 0.518 pg/mL, providing moderate sensitivity (69.4%) and specificity (81.2%). Meanwhile, the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio performed similarly to OxLDL alone, with a cutoff of >281.84, achieving sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 88.7%. Overall, these findings suggest that elevated OxLDL levels and a higher OxLDL/IL-10 ratio are strong indicators of PAD, while IL-10 alone offers more limited diagnostic value.

Table 2.

Diagnostic value of OxLDL, IL-10, and ratio of OxLDL/IL-10.

4. Discussion

This study revealed a high prevalence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) among patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy, with PAD identified in 20% of the cohort. Patients with PAD demonstrated significantly higher serum levels of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL), lower levels of interleukin-10 (IL-10), and a markedly elevated OxLDL/IL-10 ratio compared with non-PAD patients. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that, after adjusting for potential confounders including age and smoking status, OxLDL remained an independent factor associated with PAD. In contrast, IL-10 did not retain statistical significance after adjustment, suggesting that its apparent association in univariate analysis was influenced by age and smoking status as confounding variables. These findings align with previous studies showing oxLDL as a potent biomarker of endothelial dysfunction and IL-10 as a modulator of atherogenesis [14,15,16].

PAD was chosen as the vascular endpoint in this study based on its mechanistic and clinical relevance. Compared to coronary artery disease (CAD) or cerebrovascular events, PAD represents an earlier and more frequent manifestation of atherosclerosis in TKI-treated patients, particularly those on nilotinib [17]. The peripheral arteries, especially in the lower limbs, are more susceptible to endothelial dysfunction due to smaller diameter and turbulent blood flow at bifurcations [18]. Clinical reports have documented progressive peripheral arterial occlusive lesions in nilotinib-treated patients, often requiring revascularization procedures [17]. Furthermore, PAD is amenable to early detection through non-invasive methods such as the ankle–brachial index (ABI) or Doppler ultrasound, making it a practical and reproducible outcome measure in clinical research [19].

The relatively higher incidence of PAD observed in this study compared with previous reports may be explained by several methodological and population-related factors. First, PAD was identified using ankle–brachial index (ABI) measurement, which is sensitive for detecting early or subclinical peripheral perfusion impairment and may capture vascular dysfunction before the development of overt arterial obstruction, in contrast to studies that defined vascular events strictly as PAOD confirmed by imaging [20]. Additionally, differences in study design, patient characteristics, cardiovascular risk profiles, and duration of TKI exposure across cohorts may further contribute to variability in reported PAD prevalence. Together, these factors likely account for the higher PAD incidence observed in our cohort and should be considered when comparing our findings with existing literature.

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in CML patients on TKIs is multifactorial. The constitutive activation of BCR::ABL1 triggers inflammatory and proliferative signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR, JAK/STAT, and NF-κB, leading to systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [8,16]. These changes facilitate the oxidation of native LDL into oxLDL, a key mediator of vascular injury. Nilotinib, in particular, exacerbates this process by inducing dyslipidemia and exerting off-target effects on vascular repair receptors (DDR1, VEGFR, PDGFR, c-KIT), further impairing endothelial homeostasis [21].

Previous research has shown that oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) play important roles in the balance between oxidative stress and inflammation, two key processes in the development of atherosclerosis and vascular injury [22,23,24]. OxLDL contributes to blood vessel damage by triggering inflammation, promoting foam cell formation, and impairing endothelial function—all of which lead to plaque buildup in the arteries. Higher levels of OxLDL have been consistently linked with the presence and severity of peripheral artery disease (PAD) and other cardiovascular complications [25]. On the other hand, IL-10 acts as a protective, anti-inflammatory cytokine that helps calm excessive immune responses and prevent vascular inflammation. When IL-10 levels are low, this protective balance is lost, making the blood vessels more prone to damage [26,27]. Together, an increase in OxLDL and a decrease in IL-10 reflect an imbalance between oxidative stress and inflammation—a pattern that may underlie TKI-related vascular toxicity. For this reason, OxLDL and IL-10 are promising biomarkers to help detect or monitor early signs of cardiovascular toxicity in CML patients receiving TKI therapy.

IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, acts to counterbalance vascular inflammation by suppressing NF-κB activation and reducing LOX-1 expression, thereby limiting oxLDL uptake by macrophages [15]. In this study, bivariate analysis showed that serum IL-10 levels were significantly lower in patients with PAD. However, after adjusting for potential confounders such as age and smoking status in multivariate analysis, IL-10 was no longer statistically significant. This finding suggests that the variability in IL-10 levels was largely influenced by these confounding factors rather than a direct association with PAD. In contrast, the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio effectively reflected the imbalance between oxidative injury and anti-inflammatory regulation, supporting its potential as a composite biomarker for vascular risk in CML patients receiving TKI therapy. The diagnostic performance of the oxLDL/IL-10 ratio suggests it may serve as a superior marker compared to either component alone. This finding is consistent with a previous study that showed ratios between pro- and anti-inflammatory biomarkers better reflect the net pathophysiological burden of vascular disease [28].

These findings have several clinical implications. First, they suggest that TKI-treated CML patients—particularly those on nilotinib—should be systematically screened for subclinical PAD, using ABI and biomarker profiling. Second, oxLDL and the oxLDL/IL-10 ratio may serve as useful tools to stratify vascular risk and guide preventive interventions such as statin therapy or TKI switching. Third, the strong diagnostic performance of the oxLDL/IL-10 ratio supports its potential role in future longitudinal studies aiming to predict major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Further research is needed to validate these cut-off values in larger cohorts and to determine whether modulation of these biomarkers can alter clinical outcomes. The integration of novel vascular biomarkers with non-invasive functional tests (ABI, CAVI, or endothelial function imaging) may enhance early detection and allow tailored vascular monitoring in this unique patient population.

The main strength of this study is its focus on direct biomarker evaluation in relation to clinical PAD, which differentiates it from prior observational studies that only assessed PAD prevalence without biological correlates. The use of validated ELISA kits and ABI/CAVI protocols ensures high measurement reliability. However, limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes assessment of temporal changes in OxLDL, IL-10, and the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio, as well as their direct relationship with subsequent clinical events. Consequently, causal inferences cannot be established, and the observed associations should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating. Furthermore, detailed hematologic and molecular parameters, including white blood cell count, additional chromosomal abnormalities, genetic mutations, Sokal score, and BCR::ABL1 international scale, could not be comprehensively assessed due to feasibility constraints of the study design and the retrospective nature of this study. Nevertheless, this approach provides valuable insight into the inflammatory and oxidative stress profiles associated with PAD in patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors at a specific clinical time point. Future prospective longitudinal studies with serial biomarker measurements and clinical follow-up are needed to elucidate biomarker dynamics over time and to determine their prognostic significance for vascular outcomes in this population. The relatively small sample size and the inclusion of only imatinib- and nilotinib-treated patients limit the generalizability of our findings and preclude comparisons with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as dasatinib and ponatinib, which are known to have different vascular risk profiles. In addition, the biomarker panel was restricted to OxLDL and IL-10, focusing on the interplay between oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory responses; however, incorporation of a broader range of inflammatory, oxidative, and endothelial markers (e.g., hs-CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, ICAM, VCAM) would provide a more comprehensive characterization of vascular dysfunction. Furthermore, vascular involvement was assessed using subclinical PAD detected by ankle–brachial index measurements, without evaluation of major adverse cardiovascular events or integration with established cardiovascular risk scores. While this approach enables early detection of vascular impairment, longitudinal studies with larger cohorts, expanded biomarker panels, and clinical cardiovascular endpoints are warranted to validate and extend the clinical relevance of these findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the utility of OxLDL and the OxLDL/IL-10 ratio as potential biomarkers of PAD in CML patients receiving TKI therapy. The high diagnostic accuracy and biological plausibility of these markers support their role in vascular risk assessment and underscore the need for proactive cardiovascular surveillance in hematologic oncology practice, while also informing future studies evaluating preventive interventions or treatment modification strategies.

Author Contributions

H.S. designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the final version of the manuscript. M.N.D., M.S., P.N.A.A., P.Z.R., H.N., N.L. and A.A. contributed to data collection and manuscript editing. S.U.Y.B. conceived the study and provided senior supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Dr. Soetomo General Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia (No. 1457/KEPK/XI/2025). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and local regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABI | Ankle–Brachial Index |

| ACCF | American College of Cardiology Foundation |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| BCR::ABL1 | Breakpoint Cluster Region–Abelson Fusion Gene |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CAVI | Cardio–Ankle Vascular Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CML | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia |

| DDR1 | Discoidin Domain Receptor 1 |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| JAK/STAT | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| LOX-1 | Lectin-Like Oxidized LDL Receptor-1 |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-B |

| OxLDL | Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| PAD | Peripheral Artery Disease |

| PAOD | Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease |

| PDGFR | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor |

| PI3K/AKT | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B |

| Ph | Philadelphia Chromosome |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TKI | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| VEGFR | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor |

| c-KIT | Receptor Tyrosine Kinase KIT |

References

- Hehlmann, R.; Hochhaus, A.; Baccarani, M. Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2007, 370, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, I.; Winston, K. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, from Pathophysiology to Treatment-Free Remission: A Narrative Literature Review. J. Blood Med. 2023, 14, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.P.; Eide, C.A.; Druker, B.J. Response and Resistance to BCR-ABL1-Targeted Therapies. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirmi, S.; El Abd, A.; Letinier, L.; Navarra, M.; Salvo, F. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Used in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: An Analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System Database (FAERS). Cancers 2020, 12, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douxfils, J.; Haguet, H.; Mullier, F.; Chatelain, C.; Graux, C.; Dogné, J.M. Association Between BCR-ABL Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and Cardiovascular Events, Major Molecular Response, and Overall Survival. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, D.; Ame, S.; Charbonnier, A.; Coiteux, V.; Cony-Makhoul, P.; Escoffre-Barbe, M.; Etienne, G.; Gardembas, M.; Guerci-Bresler, A.; Legros, L.; et al. Recommandations 2015 du France Intergroupe des Leucémies Myéloïdes Chroniques pour la gestion du risque d’événements cardiovasculaires sous nilotinib au cours de la leucémie myéloïde chronique. Bull. Cancer 2016, 103, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.C.; Mauro, M.J.; Moslehi, J. Cardiovascular care of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) on tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy. Hematology 2017, 2017, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.D.; Rea, D.; Schwarz, M.; Grille, P.; Nicolini, F.E.; Rosti, G.; Levato, L.; Giles, F.J.; Dombret, H.; Mirault, T.; et al. Peripheral artery occlusive disease in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with nilotinib or imatinib. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, F.J.; Mauro, M.J.; Hong, F.; Ortmann, C.E.; McNeill, C.; Woodman, R.C.; Hochhaus, A.; Le Coutre, P.D.; Saglio, G. Rates of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase treated with imatinib, nilotinib, or non-tyrosine kinase therapy: A retrospective cohort analysis. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P.; Hadzijusufovic, E.; Schernthaner, G.H.; Wolf, D.; Rea, D.; le Coutre, P. Vascular safety issues in CML patients treated with BCR/ABL1 kinase inhibitors. Blood 2015, 125, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasvolsky, O.; Leader, A.; Iakobishvili, Z.; Wasserstrum, Y.; Kornowski, R.; Raanani, P. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor associated vascular toxicity in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cardio-Oncology 2015, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.T.; Huang, S.T.; Lin, C.W.; Ko, B.S.; Chen, W.J.; Huang, H.H.; Hsiao, F.Y. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Vascular Adverse Events in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Population-Based, Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study. Oncologist 2021, 26, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upshaw, J.N.; Travers, R.; Jaffe, I.Z. ROCK and Rolling Towards Predicting BCR-ABL Kinase Inhibitor-Induced Vascular Toxicity. Cardio Oncol. 2022, 4, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiano, S.; Montagnaro, S.; Puzio, M.V.; Severino, L.; Pagnini, U.; Barbarino, M.; Cesari, D.; Giordano, A.; Florio, S.; Ciarcia, R. Effects of antioxidants on apoptosis induced by dasatinib and nilotinib in K562 cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 4845–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, A.; Mirabile, G.; Caserta, S.; Stagno, F.; Russo, S.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Oxidative Stress and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Balance between ROS-Mediated Pro- and Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 461. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38671909 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Appel, S.; Rupf, A.; Weck, M.M.; Schoor, O.; Brummendorf, T.H.; Weinschenk, T.; Grunebach, F.; Brossart, P. Effects of Imatinib on Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Are Mediated by Inhibition of Nuclear Factor-κB and Akt Signaling Pathways. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfel, D.; Lechner, C.J.; Joas, S.; Funk, T.; Gutknecht, M.; Salih, J.; Geiger, J.; Kropp, K.N.; Maurer, S.; Müller, M.R.; et al. The BCR-ABL inhibitor nilotinib influences phenotype and function of monocyte-derived human dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 775–783. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29468363 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tedgui, A.; Mallat, Z. Cytokines in Atherosclerosis: Pathogenic and Regulatory Pathways. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 515–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchia, M.; Galimberti, S.; Aprile, L.; Sicuranza, A.; Gozzini, A.; Santilli, F.; Abruzzese, E.; Baratè, C.; Scappini, B.; Fontanelli, G.; et al. Genetic predisposition and induced pro-inflammatory/pro-oxidative status may play a role in increased atherothrombotic events in nilotinib treated chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 72311–72321. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27527867 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sicuranza, A.; Ferrigno, I.; Abruzzese, E.; Iurlo, A.; Galimberti, S.; Gozzini, A.; Luciano, L.; Stagno, F.; Russo Rossi, A.; Sgherza, N.; et al. Pro-Inflammatory and Pro-Oxidative Changes During Nilotinib Treatment in CML Patients: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Front-Line TKIs Study (KIARO Study). Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 835563. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35178353 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.G.; Florida, E.; Li, H.; Parel, P.M.; Mehta, N.N.; Sorokin, A.V. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein associates with cardiovascular disease by a vicious cycle of atherosclerosis and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 9, 1023651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjuman, A.; Chandra, N.C. Effect of IL-10 on LOX-1 expression, signalling and functional activity: An atheroprotective response. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2013, 10, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criqui, M.H.; Aboyans, V. Epidemiology of Peripheral Artery Disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1509–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, K.; Hiruta, N.; Song, M.; Kurosu, T.; Suzuki, J.; Tomaru, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Saiki, A.; Takahashi, M.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index (CAVI) as a Novel Indicator of Arterial Stiffness: Theory, Evidence and Perspectives. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2011, 18, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, J.J.; Deininger, M. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor–Associated Cardiovascular Toxicity in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4210–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam Sunder, S.; Sharma, U.C.; Pokharel, S. Adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: Pathophysiology, mechanisms and clinical management. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matter, M.A.; Paneni, F.; Libby, P.; Frantz, S.; Stähli, B.E.; Templin, C.; Mengozzi, A.; Wang, Y.J.; Kündig, T.M.; Räber, L.; et al. Inflammation in acute myocardial infarction: The good, the bad and the ugly. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M. Novel Inflammatory Markers of Coronary Risk. Circulation 1999, 100, 1148–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.