Abstract

Introduction: Ropeginterferon alfa-2b is an emerging treatment for polycythemia vera, with growing interest in its application for essential thrombocythemia and early myelofibrosis due to its extended dosing intervals and favorable tolerability profile. However, real-world evidence regarding its dosing strategies and titration practices remains limited. Objective: This study examined seven younger patients, all under 60 years of age, who were treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b. Materials and Methods: This study is a retrospective medical records review of consecutive patients from seven hospitals. Treatment was initiated at a dose of 250 micrograms, with a maintenance dose of 500 micrograms. Results: The regimen demonstrated good safety and tolerability in this real-world setting. Hematological responses were observed, along with a meaningful reduction in JAK2V617F variant allele frequency across the patient cohort. Conclusions: These findings show that the use of high-initial-dose accelerated titration (HIDAT) regimen of ropeginterferon alfa-2b is a safe and effective treatment option for younger patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms.

1. Introduction

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b (ropegIFN), a novel monopegylated, extra-long-acting interferon alpha, was approved for the treatment of polycythemia vera (PV) [1]. Its distinctive feature of an extended dosing interval (q2w or longer) combined with improved tolerability, comparable to hydroxyurea (HU), has sparked growing clinical and research interests. While its primary application is in PV, ropegIFN is also being explored for treatment in other myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) such as essential thrombocythemia (ET) and myelofibrosis (MF). Despite years of availability of this promising therapeutic agent, the dosing and titration strategy for this innovative therapeutic agent remain subjects of ongoing research [2].

Clinical studies have explored various titration and dosage regimens. The phase I/II PEGINVERA study adopted a titration approach starting from 50 mcg, incrementally increasing to 100, 150, 225, 300, 360, 450, and culminating at 540 mcg, with each dose level elevated biweekly [3]. The phase III PROUD-PV study employed a dosage regimen titrating from 100 mcg, adding 50 mcg every two weeks until reaching the target dose (maximum 500 mcg), whereas patients transitioning from HU initiated ropegIFN at 50 mcg [1]. The SURPASS-ET Phase III study implemented a titration method ranging from 250 to 350 to 500 mcg (250–350–500 mcg titration), with the maximal maintenance dose set at 500 mcg [4]. A phase II trial in China utilized the 250–350–500 mcg titration [5], whereas another phase II trial in Japan utilized the titration method in PROUD-PV [6]. In the Low-PV study, enrolling low-risk PV patients, a fixed dose of 100 mcg q2w regimen was utilized in conjunction with phlebotomy [7].

Clinical practice in Taiwan regarding ropegIFN administration is distinctive, as nearly all patients initiate therapy at a dose of 250 mcg or higher, rapidly escalating to a maintenance dose of 500 mcg. This approach is informed by prior experience from local compassionate use programs for MPN prior to ropegIFN approval [8,9] and supported by findings from hepatitis trials [10,11]. Although ropegIFN has received approval for PV treatment in Taiwan, stringent national health insurance criteria limit subsidization to high-risk patients under specific conditions, thereby restricting broader clinical experience with high-dose, rapid titration of ropegIFN in younger patients.

The high-initial-dose accelerated titration (HIDAT) approach is suggested to facilitate faster complete hematologic responses (CHR) and molecular remissions (MR). In this report, we describe the real-world experience in a series of consecutively treated patients age < 60, focusing on safety, hematological response, and JAK2V617F variant allele frequency (VAF) reduction using HIDAT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Population

This study is a retrospective medical records review of consecutive patients from seven hospitals. Ethical requirements were met at each participating hospital. Patients younger than 60 years of age who had received ropegIFN for at least one year were included. In Taiwan, National Health Insurance reimbursement for ropegIFN is limited to patients aged ≥ 60 years or with a history of thrombosis who have received frequent phlebotomy and maximal tolerated HU yet remain inadequately controlled, defined as hematocrit (Hct) greater than 45%, platelet count (PLT) greater than 600 × 109/L, and white blood cell count (WBC) greater than 10 × 109/L. Consequently, only a limited number of younger patients were able to access ropegIFN through alternative channels.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were extracted by respective physicians using a standardized data collection form. The data cut-off was 31 August 2024. Extracted data include birth year, biological sex, year of diagnosis, type of MPN, type of driver mutation, JAK2V617F allele burden where applicable, complete blood count including WBC, PLT, Hct, liver function tests, renal function tests, thyroid function tests, and treatment records. The adverse events were collected systematically with the assistance of MPN case managers in most cases.

For the six patients carrying the JAK2V617F mutation, allele burden was assessed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) (n = 2), quantitative competitive allele-specific TaqMan duplex polymerase chain reaction (qCast-Duplex PCR) (n = 3) [12], or genomic DNA quantitative PCR reaction with TaqMan probe in (n = 1). Two patients were evaluated by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction before April 2022 and followed by NGS) (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) from May 2022 onwards. Three patients were evaluated by qCast-Duplex PCR, an improved and patented PCR method which has been validated against digital droplet PCR, showing a correlation of 0.99. The detection sensitivity threshold for all methods was 0.01%.

3. Results

A total of seven cases were consecutively recruited (Table 1). There were four female and three male patients, with a median age at diagnosis of 43 years. The median age at initiation of ropegIFN was 45 years. Baseline antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) were not tested in most cases and were available in only one patient. Ferritin levels were assessed during follow-up in three cases, all of which demonstrated improvement and normalization in the absence of phlebotomy. All but one patient with PV discontinued phlebotomy after initiation of ropegIFN; the remaining patient underwent phlebotomy only once, at week 18. No autoimmune disorders were observed following ropegIFN treatment. Mild transaminase elevation was observed in two cases.

Table 1.

Overview of Seven Younger Patients Diagnosed with Polycythemia Vera or Essential Thrombocythemia Treated with Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b.

RopegIFN was initiated for different clinical reasons across cases. Cases 1, 3, 4, and 5 required cytoreductive therapy, but declined HU and elected to receive ropegIFN based on shared decision-making [13]. Cases 2 and 7 were initiated on ropegIFN due to young age, for whom ropegIFN was considered a preferred option over HU, in accordance with guideline recommendations. Case 6 was resistant to HU.

3.1. Case 1: JAK2V617F VAF Reduction by 88%

A 52-year-old man was diagnosed with PV after pancytosis and gout. Initial JAK2V617F VAF was 49%. He underwent phlebotomy for 5 years while on clopidogrel due to gastric ulcers. Persistent leukocytosis and thrombocytosis led to the initiation of ropegIFN, which the patient preferred over HU.

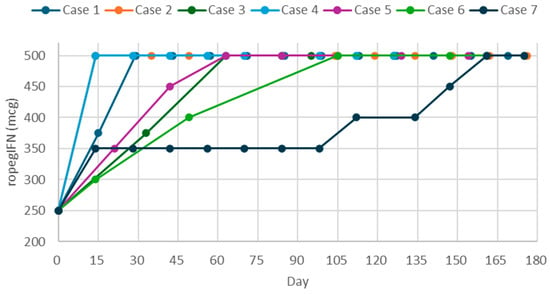

Mild dizziness and chills occurred initially, but resolved spontaneously. The dose was titrated to 500-mcg q2w, then gradually extended to q8w to maintain hematologic response and reduce JAK2V617F VAF (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Titration and dosage regimens of ropeginterferon alfa-2b over the first 180 days in a real-world setting.

RopegIFN achieved rapid normalization of blood counts without phlebotomy (Supplemental Figure S1). Over 3 years, JAK2V617F VAF declined from 99.4% to 11.7%. Transient AST elevation (28–46 U/L) resolved without intervention; ALT remained normal. Free T4 and TSH were stable. Occasional fatigue, dizziness, and postural hypotension were reported.

3.2. Case 2: Maximum Dosage Regimen Required for HR

A 24-year-old woman was diagnosed with ET 11 years ago. At diagnosis, PLT was >1000 × 109/L and HU was started. During her studies abroad, therapy was switched to conventional interferon. While she recalled a positive JAK2 result overseas, re-evaluation revealed a negative JAK2 and positive CALR mutation. After returning to Taiwan, she was treated with another interferon, but developed fever and poor tolerability, prompting ropegIFN initiation.

Tolerating treatment well, she proceeded to 500 mcg q2w (Supplemental Figure S2). After nine injections, PLT decreased to 474 × 109/L, and dosing was extended to q4w. However, PLT rose over 8 m, prompting reversion to 500 mcg q2w. After 18 injections over 9 m, PLT dropped to 466 × 109/L. Occasional mild headaches were reported.

3.3. Case 3: Extended Injection Interval Achieved MR

A 47-year-old woman diagnosed with PV 4 years ago reported pruritus and extremity numbness. Initial management included aspirin and phlebotomy. To achieve improved hematologic and molecular control, ropegIFN was initiated, and phlebotomy was discontinued concurrently.

Due to financial limitations, dosing began at every 30 days for 6 m, later extended to every 45 days. Blood counts remained within normal range throughout. JAK2V617F VAF declined from 36.1% to 0.7% after 29 injections over 40 m (Supplemental Figure S3). She reported intermittent abdominal pain, alopecia, asthma, headache, nausea, and tingling.

3.4. Case 4: CHR in 1 Year and CMR in 2.5 Years

A 37-year-old woman was diagnosed with PV following abnormal counts detected after surgery. Initial management included aspirin and phlebotomy. RopegIFN was subsequently initiated, and phlebotomy was discontinued. Leukocytosis and thrombocytosis were rapidly controlled (Supplemental Figure S4). JAK2V617F VAF was 80% at 6 m and declined to 7% at 15 m. CMR was achieved after 29 m. Adverse events included mild fever, dizziness, fatigue, myalgia, pruritus, night sweats, diarrhea, and alopecia. All resolved spontaneously or were manageable.

3.5. Case 5: Rapid Reduction in JAK2V617F VAF and Eventual Complete MR

A 42-year-old man with PV, initially managed with aspirin and phlebotomy, experienced persistent leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, fatigue, flushing, and iron deficiency. Due to HU refusal, ropegIFN was initiated.

The patient underwent titration at 250, 350, and 450 mcg every two weeks, then maintained on 500 mcg q3w/q4w due to transaminase elevation (Supplemental Figure S5). Over 2.6 years, he achieved stable counts and a remarkable JAK2V617F VAF decline from 86.6% to undetectable within 19 m. Mild flu-like symptoms occurred during titration, but resolved in the maintenance phase.

3.6. Case 6: Transition from HU to RopegIFN

A 54-year-old man with PV and JAK2V617F VAF of 49.0% was diagnosed following a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (Supplemental Figure S6). Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease. He was initially treated with aspirin, phlebotomy, and HU up to 2000 mg/d. Despite normalized WBC and PLT, Hct remained >50%, and frequent angina episodes necessitated transitioning to ropegIFN.

RopegIFN began at 250 mcg, titrated to 500 mcg with monthly injections while tapering HU until discontinuation after six doses of ropegIFN, and the injection interval was shortened to three weeks. CHR was achieved, and blood count rebounds occurred briefly after HU cessation. No adverse events or angina recurred during 10 m of ropegIFN.

3.7. Case 7: Initiation and Re-Initiation of RopegIFN

A female patient was diagnosed with PV at seven following investigation for persistent urticaria. At age 15, due to uncontrolled leukocytosis and thrombocytosis, she was started on ropegIFN at 250 mcg and titrated to 500 mcg q2w (Supplemental Figure S7), achieving CHR before tapering to 500 mcg q4w.

RopegIFN was discontinued for 2.4 years due to relocation. Within 2 m, blood counts worsened and were managed with anagrelide and then HU. Upon return and considering her young age and reproductive potential, ropegIFN was re-initiated at 500 mcg q2w. After two doses, PLT and WBC normalized, and JAK2V617F VAF decreased from 29.99% to 22.45%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Treatment Recommendations for PV

Current treatment recommendations in the United States and Europe prioritize the prevention of thrombotic complications as the primary therapeutic objective in PV. The 20-year cumulative risk of thrombosis has been reported to be approximately 26% [14]. Thrombosis prevention is generally achieved through regular phlebotomy to maintain Hct levels below 45%, in combination with antiplatelet therapy, and is applied across all PV risk categories.

Cytoreductive therapy is typically reserved for patients with high-risk PV, with HU and interferon recommended as first-line treatment options, while ruxolitinib is considered in the second-line setting [15]. Despite these guideline recommendations, disparities have been observed in real-world clinical practice in the United States, where approximately 35% of high-risk PV patients reportedly did not receive cytoreductive therapy [16].

4.2. Treatment for Low-Risk Patients in PV

Cytoreductive therapy may be considered for low-risk PV patients who experience intolerance to phlebotomy, symptomatic or progressive splenomegaly, persistent or progressive leukocytosis, extreme thrombocytosis, inadequate Hct control requiring frequent phlebotomies, persistently elevated cardiovascular risk, or a sustained high symptom burden [17]. Given the younger age of this patient population, international experts from European LeukemiaNet have recommended recombinant IFN, including ropegIFN and pegylated IFN alfa-2a, as preferred cytoreductive treatment options for low-risk patients [17].

However, despite these recommendations, access to recombinant IFN may be limited for younger patients requiring cytoreductive therapy due to health insurance policies or drug availability, leading to the continued use of HU in this population. Some patients subsequently develop HU resistance or intolerance, defined by one or more of the following criteria: persistent need for phlebotomy to maintain Hct below 45% or uncontrolled myeloproliferation despite at least 3 months of HU at doses of ≥2 g/day; failure to adequately reduce symptomatic splenomegaly after sufficient HU exposure; development of significant cytopenias at the lowest effective HU dose; or occurrence of unacceptable HU-related nonhematologic toxicities, including leg ulcers or other severe adverse effects [18]. Case 6 exemplifies this scenario, having received HU at doses of ≥2 g/day for three months while continuing to exhibit elevated Hct, PLT, and WBC, highlighting the need for alternative cytoreductive strategies beyond HU, even in low-risk patients.

Importantly, “low-risk” primarily refers to thrombotic risk rather than the risk of disease progression. A population-based cross-sectional study in Taiwan demonstrated comparable rates of myelofibrotic progression and AML transformation between low- and high-risk patients [19]. Consistent with these findings, a 2024 update on PV estimated the 20-year cumulative risks of post-PV myelofibrosis and AML transformation to be approximately 16% and 4%, respectively [14]. In the context of emerging therapies with disease-modifying potential, these observations suggest that a proactive treatment strategy in younger patients may become increasingly relevant, particularly for those in whom long-term disease control and prevention of progression are key therapeutic goals.

4.3. Personalized Management

Personalized regimens can be highly variable and require careful consideration of many aspects, including alleviating symptoms, minimizing side effects, maintaining normal blood counts while considering the differential responses of various parameters, preventing thrombosis, ensuring good quality of life, maintaining adherence to the regimen, addressing financial constraints, and achieving deeper molecular responses. Current utilization of ropegIFN is limited to the traditional trial-and-error approach to adjust the optimal personalized management of these chronic diseases.

There is a growing body of evidence highlighting the prognostic importance of high-risk co-occurring genetic mutations, including TET2, DNMT3A, IDH1/2, ASXL1, EZH2, SRSF2, U2AF1, and TP53 [20]. Mutations in TET2, DNMT3A, and ASXL1 have been reported as age-independent risk factors for thrombosis in PV [21]. The SRSF2 mutation has been associated with adverse outcomes in blast-phase disease [22]. In addition, SRSF2, IDH2, and ASXL1 mutations have been identified as predictors of overall survival in PV [23]. An improved understanding of these somatic mutations may further inform risk stratification, prognostication, and management strategies in PV.

Future research on personalized approaches such as genome-wide association studies testing the association between genetic factors and response to interferon may provide further guidance to clinicians to decide on optimal, personalized ropegIFN regimen. Aligning with this goal, a previous targeted sequencing study reviewed 21 MPN patients who had received ropegIFN treatment [8]. The results suggest that inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPA) SNPs rs6051702 A > C and rs1127354 C > A were associated with an inferior complete hematological response rate within one year, as well as inferior molecular response. Additionally, ITPA SNPs rs6051702 A > C may be associated with the risks of hepatotoxicity.

Case 2 illustrates the importance of maintaining the maximal dosage regimen of 500 mcg q2w. Although the patient initially achieved a partial response on this schedule, transitioning to q4w led to progressive PLT elevation, necessitating a return to q2w to restore control. Conversely, Case 3 demonstrates that treatment regimens can be successfully adapted to balance clinical goals and financial considerations. The patient maintained CHR over 3.7 y on 500 mcg at gradually extended intervals (q30d to q45d), while achieving a marked reduction in JAK2V617F VAF (from 36.08% to 0.66%).

4.4. Re-Introduction of RopegIFN

The experience in Case 7 showed that the re-introduction of ropegIFN was feasible. After 2.5 years of ropegIFN treatment, it was discontinued for 2.4 years partly due to relocation. During the period of discontinuation, although the patient’s CBC was partially controlled, it was not optimal and CHR was not maintained. This demonstrated that continuous treatment with ropegIFN is necessary to maintain CHR, especially in the presence of a relatively high level of JAK2V617F allele burden. When the patient was re-initiated with ropegIFN, all hematological parameters normalized and the VAF continued to show a decreasing trend.

4.5. Molecular Response and VAF

In addition to achieving hematological control, molecular response was included as one of the key treatment goals. Of the five patients assessed, Cases 4 and 5 achieved undetectable levels (<0.01%) of JAK2V617F allele burden after 824 and 854 days of treatment, respectively. Case 3 reached an allele burden of 0.7% after 1198 days of q30d/q45d treatment. Case 1 achieved a significant reduction in the allele burden from 99% to 12%. Incidentally, Case 1, 3, 4, and 5 with significant reduction were found to be HU-naïve. However, since somatic mutation data were unavailable, the effect of other mutations, namely DNMT3A, cannot be ruled out.

The association between JAK2V617F allele burden and clinical characteristics has long been debated. According to a meta-analysis, JAK2V617F allele burden was shown to be significantly and positively associated with red blood cell count, WBC, spleen size, and lactate dehydrogenase levels, as well as the risks of pruritus, splenomegaly, thrombosis, MF progression, and leukemic transformation [24]. Furthermore, previous studies of PV patients receiving pegylated interferon, ropegIFN, and ruxolitinib showed that the reduction in JAK2V617F allele burden conferred better outcomes, such as lower relapse rates after treatment discontinuation and higher rates of progression-free survival, event-free survival, and overall survival [25,26,27]. These pieces of evidence provide a compelling basis for considering the reduction in JAK2V617F VAF to be one of the treatment goals, at least in PV patients with JAK2V617F mutation.

4.6. Real-World Treatment Patterns and Implications

A population-based study in Taiwan surveyed 2647 PV patients found that 73.9% of high-risk and 51.2% of low-risk patients received phlebotomy and/or HU prior to the regulatory approval of ropegIFN [19]. Currently, in Taiwan, only high-risk patients who meet specific criteria, such as pancytosis and certain treatment histories, are eligible for full subsidy of ropegIFN. This research highlights the unmet clinical needs of low-risk patients.

With the availability of disease-modifying agents, reducing the allele burden of driver mutations in MPNs has emerged as a potential treatment goal. Historically, therapeutic options for PV were limited, with some treatments, such as pipobroman and chlorambucil, associated with leukemogenic risks [28,29]. As a result, low-risk patients were often managed with low-dose aspirin and phlebotomy alone, as the risks of past available therapies outweighed their benefits. However, new disease-modifying agents provide a strong rationale for actively treating PV patients, including those previously classified as low-risk.

From the perspective of Taiwanese physicians, our immediate objective is to control blood counts and prevent thromboembolic events while ensuring a good quality of life. In the long term, as a primary treatment goal in PV management, realized through shared decision-making with patients, we aim to reduce the JAK2V617F allele burden to undetectable levels. For patients achieving undetectable JAK2V617F levels, drug holidays and molecular monitoring would be considered, with the hope of sustained remission and preventing relapse. This underscores the need for further investigation into the dosage and regimen of ropegIFN to develop an optimized, personalized approach [20,30,31]. Moreover, as patients gain greater access to medical knowledge, they increasingly seek therapies that may delay disease progression as the treatment goal [32]. We believe that by employing disease-modifying agents and closely monitoring JAK2V617F allele burden, PV patients will experience improved overall survival, event-free survival, and treatment-free survival rates.

Although this study is limited by the small cohort size and lack of comparators, it represents a significant proportion of younger MPN patients who had access to ropegIFN and accurately reflects current clinical practices in Taiwan, thereby providing unique real-world insights into the existing literature on ropegIFN dosing strategies. Future plans include expanding this research with a large-scale retrospective cohort study.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the real-world application of ropegIFN in consecutive low-risk MPN patients in Taiwan, initiating treatment with a titration from an initial dose of 250 mcg to a maintenance dose of 500 mcg, while taking individual response and tolerability into consideration during titration by adjusting the dose and/or injection frequency. Our findings provide early real-world evidence supporting the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of HIDAT regimen. However, given the retrospective design and limited sample size, definitive conclusions regarding efficacy and long-term outcomes cannot be drawn from individual cases alone. Larger prospective studies and randomized clinical trials are required to further validate these observations and to define the optimal role of this regimen in the management of low-risk MPN patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hemato7010002/s1. Figure S1. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, JAK2V617F variant allele frequency, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 1. Figure S2. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 2. Figure S3. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, JAK2V617F variant allele frequency, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 3. Figure S4. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, JAK2V617F variant allele frequency, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 4. Figure S5. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, JAK2V617F variant allele frequency, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 5. Figure S6. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, JAK2V617F variant allele frequency, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 6. Figure S7. Long-term follow-up of hematocrit, platelet count, leucocyte count, JAK2V617F variant allele frequency, and dosage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Case 7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.H.-L.Y. and H.-A.H.; Data curation: S.-N.P., C.G.-S.C., H.-W.K., H.-E.T., M.-L.H., C.-C.C., and H.-A.H.; Funding acquisition: L.H.-L.Y. and H.-A.H.; Investigation: S.-N.P., C.G.-S.C., H.-W.K., H.-E.T., M.-L.H., C.-C.C., and H.-A.H.; Methodology: L.H.-L.Y. and H.-A.H.; Project administration: J.H.-W.W.; Resources: C.-C.C., L.H.-L.Y., and H.-A.H.; Supervision: H.-A.H.; Visualization: J.H.-W.W. and L.H.-L.Y.; Writing—original draft: S.-N.P., C.G.-S.C., H.-W.K., and J.H.-W.W.; Writing—review and editing: H.-E.T., M.-L.H., C.-C.C., L.H.-L.Y., and H.-A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical requirements were met at each participating hospital. This study received the following ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at the participating hospitals. MacKay Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Board (23MMHIS110e, 2023/06/12); E-DA Healthcare Group Institutional Review Board (2023006, 2023/10/18). NTUH Ethics Center Research Ethics Section (202207050RINB, 2022/07/05; 202407053RINA, 2024/07/05); Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board (CY-202302012B0, 2024/01/24; LK-202301956B0, 2024/01/26); TMU-Joint Institutional Review Board (N202409052, 2024/10/17).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, or patient consent was waived based on the ethical requirement of the institution.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alex Jia-Hong Lin for administrative assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

Jasmine Hsiang-Wei Wang and Lennex Hsueh-Lin Yu are full-time employees for Panco Healthcare Co., Ltd., a Pharmaessentia Company. Sung-Nan Pei and Huey-En Tzeng declared honorariums from PharmaEssentia Corporation. Hsin-An Hou and Chih-Cheng Chen declare honorarium, travel, and research support from PharmaEssentia Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| CBC | complete blood count |

| CHR | complete hematologic response |

| CMR | complete molecular remission |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ET | essential thrombocythemia |

| Hct | hematocrit |

| HIDAT | high-initial-dose, accelerated titration |

| HU | hydroxyurea |

| ITPA | inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase |

| JAK2V617F | Janus kinase 2 V617F mutation |

| Low-PV | Low-risk polycythemia vera study |

| MF | myelofibrosis |

| mg/d | milligrams per day |

| MPN | myeloproliferative neoplasm(s) |

| MR | molecular remission |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PLT | platelet count |

| PV | polycythemia vera |

| q2w | every 2 weeks |

| q3w | every 3 weeks |

| q4w | every 4 weeks |

| q8w | every 8 weeks |

| q30d | every 30 days |

| q45d | every 45 days |

| qCast-Duplex PCR | quantitative competitive allele-specific TaqMan duplex PCR |

| ropegIFN | ropeginterferon alfa-2b |

| SNP/SNPs | single nucleotide polymorphism(s) |

| SURPASS-ET | Phase III ropegIFN study |

| T4/Free T4 | thyroxine |

| TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| U/L | units per liter |

| VAF | variant allele frequency |

| WBC | white blood cell count |

References

- Gisslinger, H.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Rossiev, V.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): A randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e196–e208, Erratum in Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30069-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, A.; Urbanski, R.W.; Yu, L.; Ahmed, T.; Mascarenhas, J. An alternative dosing strategy for ropeginterferon alfa-2b may help improve outcomes in myeloproliferative neoplasms: An overview of previous and ongoing studies with perspectives on the future. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1109866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gisslinger, H.; Zagrijtschuk, O.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Thaler, J.; Schloegl, E.; Gastl, G.A.; Wolf, D.; Kralovics, R.; Gisslinger, B.; Strecker, K.; et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b, a novel IFNα-2b, induces high response rates with low toxicity in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood 2015, 126, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Verstovsek, S.; Komatsu, N.; Gill, H.; Jin, J.; Lee, S.-E.; Hou, H.-A.; Sato, T.; Qin, A.; Urbanski, R.; Shih, W.; et al. SURPASS-ET: Phase III study of ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus anagrelide as second-line therapy in essential thrombocythemia. Futur. Oncol. 2022, 18, 2999–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Qin, A.; Zhang, L.; Shen, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Xiao, Z. A phase II trial to assess the efficacy and safety of ropeginterferon α-2b in Chinese patients with polycythemia vera. Futur. Oncol. 2023, 19, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edahiro, Y.; Ohishi, K.; Gotoh, A.; Takenaka, K.; Shibayama, H.; Shimizu, T.; Usuki, K.; Shimoda, K.; Ito, M.; VanWart, S.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ropeginterferon alfa-2b in Japanese patients with polycythemia vera: An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Int. J. Hematol. 2022, 116, 215–227, Erratum in Int. J. Hematol. 2022, 116, 642–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-022-03440-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbui, T.; Vannucchi, A.M.; De Stefano, V.; Masciulli, A.; Carobbio, A.; Ferrari, A.; Ghirardi, A.; Rossi, E.; Ciceri, F.; Bonifacio, M.; et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus phlebotomy in low-risk patients with polycythaemia vera (Low-PV study): A multicentre, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e175–e184, Erratum in Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00021-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Kuo, M.; Wang, Y.; Pei, S.; Huang, M.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Shih, L. Treatment outcome and germline predictive factors of ropeginterferon alpha-2b in myeloproliferative neoplasm patients. Cancer Med. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, C.-E.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Hsu, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tsou, H.-Y.; Li, C.-P.; Lai, Y.-H.; Lu, C.-H.; Chen, P.-T.; Chen, C.-C. Real-world experience with Ropeginterferon-alpha 2b (Besremi) in Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, S.-J.; Yu, M.-L.; Su, C.-W.; Peng, C.-Y.; Chien, R.-N.; Lin, H.-H.; Lo, G.-H.; Su, W.-W.; Kuo, H.-T.; Hsu, C.-W.; et al. Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b administered every two weeks for patients with genotype 2 chronic hepatitis C. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Hsu, S.; Lu, S.; Chuang, W.; Hsu, C.; Chien, R.; Yang, S.; Su, W.; Wu, J.; Lee, T.; et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b in patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C: Pharmacokinetics, safety, and preliminary efficacy. JGH Open 2021, 5, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Huang, C.-E.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Lung, J.; Leu, Y.-W.; Li, C.-P.; Tsou, H.-Y.; Chuang, W.-H.; Lu, C.-H.; et al. Quantitative competitive allele-specific TaqMan duplex PCR (qCAST-Duplex PCR) assay: A refined method for highly sensitive and specific detection of JAK2V617F mutant allele burdens. Haematologica 2018, 103, e450–e454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A.; Barbui, T. Polycythemia vera: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1465–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerds, A.T.; Gotlib, J.; Ali, H.; Bose, P.; Dunbar, A.; Elshoury, A.; George, T.I.; Gundabolu, K.; Hexner, E.; Hobbs, G.S.; et al. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 1033–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zeinah, G.; Hunter, A.M.; Shatzel, J.J.; Yacoub, A.; Qin, A.; Chien, H.-L.; Mesa, R.A. Real-world analysis of polycythemia vera treatment reveals nonadherence to NCCN guidelines in a large proportion of patients. Blood Neoplasia 2025, 2, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Griesshammer, M.; Harrison, C.; Koschmieder, S.; Gisslinger, H.; Álvarez-Larrán, A.; De Stefano, V.; Guglielmelli, P.; Palandri, F.; et al. Appropriate management of polycythaemia vera with cytoreductive drug therapy: European LeukemiaNet 2021 recommendations. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e301–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barosi, G.; Birgegard, G.; Finazzi, G.; Griesshammer, M.; Harrison, C.; Hasselbalch, H.; Kiladijan, J.; Lengfelder, E.; Mesa, R.; Mc Mullin, M.F.; et al. A unified definition of clinical resistance and intolerance to hydroxycarbamide in polycythaemia vera and primary myelofibrosis: Results of a European LeukemiaNet (ELN) consensus process. Br. J. Haematol. 2010, 148, 961–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, T.-H.; Yu, L.H.-L.; Yu, M.-S.; Huang, S.-H.; Lin, A.J.-H.; Lee, K.-D.; Chen, M.-C. Real-world patient characteristics and treatment patterns of polycythemia vera in Taiwan between 2016 and 2017: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2023, 14, 20406207231179331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, P.; Xiao, Z.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Prchal, J.T.; Duan, M.; Yacoub, A.; Rampal, R.; Kiladjian, J.-J.; Hobbs, G.S.; Tashi, T.; et al. Highlights from MPN Asia 2025: Advances in Molecular Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Curr. Hematol. Malign. Rep. 2025, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Díaz, A.; Stuckey, R.; Florido, Y.; Sobas, M.; Álvarez-Larrán, A.; Ferrer-Marín, F.; Pérez-Encinas, M.; Carreño-Tarragona, G.; Fox, M.L.; Vega, B.T.; et al. DNMT3A/TET2/ASXL1 Mutations are an Age-independent Thrombotic Risk Factor in Polycythemia Vera Patients: An Observational Study. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 124, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-J.; Rampal, R.; Manshouri, T.; Patel, J.; Mensah, N.; Kayserian, A.; Hricik, T.; Heguy, A.; Hedvat, C.; Gönen, M.; et al. Genetic analysis of patients with leukemic transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms shows recurrent SRSF2 mutations that are associated with adverse outcome. Blood 2012, 119, 4480–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.S.; Iftikhar, M.; Jadoon, Y.; Abdelmagid, M.; Viswanatha, D.S.; He, R.; Reichard, K.K.; Pardanani, A.D.; Gangat, N.; Tefferi, A. The Mutational Landscape in Polycythemia Vera: Phenotype, Genotype, and Prognostic Correlates. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, J.L.; Lin, A.J.; Yu, L.H.; Hou, H.A. Association of JAK2V617F allele burden and clinical correlates in polycythemia vera: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 1947–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, R.D.; Soret-Dulphy, J.; Zhao, L.-P.; Marcault, C.; Gauthier, N.; Verger, E.; Maslah, N.; Parquet, N.; Raffoux, E.; Vainchenker, W.; et al. Interferon-Alpha (IFN) Therapy discontinuation is feasible in Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (MPN) patients with complete hematological remission. Blood 2020, 136, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.N.; Nangalia, J.; Boucher, R.; Jackson, A.; Yap, C.; O’Sullivan, J.; Fox, S.; Ailts, I.; Dueck, A.C.; Geyer, H.L.; et al. Ruxolitinib Versus Best Available Therapy for Polycythemia Vera Intolerant or Resistant to Hydroxycarbamide in a Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3534–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gisslinger, H.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; Sivcheva, L.; et al. Event-free survival in patients with polycythemia vera treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus best available treatment. Leukemia 2023, 37, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parmentier, C.; Gardet, P. The use of 32 phosphorus (32P) in the treatment of polycythemia vera. Nouv. Rev. Fr. Hematol. 1994, 36, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kiladjian, J.J.; Chevret, S.; Dosquet, C.; Chomienne, C.; Rain, J.D. Treatment of polycythemia vera with hydroxyurea and pipobroman: Final results of a randomized trial initiated in 1980. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3907–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Tefferi, A.; Vannucchi, A.M. The dosage of ropeginterferon in polycythaemia vera: Balancing efficacy, safety and pharmacoeconomics across risk categories. Br. J. Haematol. 2025, 206, 984–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Zhang, L.; Jin, J. The higher initial dose and accelerated titration regimen of ropeginterferon as a treatment option for certain patients with polycythaemia vera. Br. J. Haematol. 2025, 206, 986–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa, R.A.; Miller, C.B.; Thyne, M.; Mangan, J.; Goldberger, S.; Fazal, S.; Ma, X.; Wilson, W.; Paranagama, D.C.; Dubinski, D.G.; et al. Differences in treatment goals and perception of symptom burden between patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and hematologists/oncologists in the United States: Findings from the MPN Landmark survey. Cancer 2017, 123, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.