Abstract

Background/Objectives: Understanding blood group antigen distribution is essential for transfusion safety and preventing alloimmunization in transfused patients. The ABO, RH1, and Kell blood group systems are among the most clinically significant due to their high immunogenic potential and their role in hemolytic transfusion reactions and hemolytic disease of the newborn. Despite their clinical significance, data on the phenotypic frequency of these samples in southern Chile are limited. This study aimed to identify the distribution of ABO, RH1, and Kell blood group systems among blood donors at the Centro de Sangre Concepción, adding regional data to the national transfusion medicine records. Methods: A retrospective, descriptive analysis was conducted using data from 59,318 blood donations collected in 2024 by the Concepción Blood Center, part of the Southern Transfusion Medicine Macronetwork in Chile. Blood typing for the ABO, RH1, and Kell antigen (KEL1) typing was performed in accordance with national regulations established by the Ministry of Health (MINSAL). Results: Blood group O was the most frequent (61.3%), followed by A (27.8%), B (9.0%), and AB (1.9%). RH1 positivity was observed in 94.47% of donors, and Kell positivity in 4.24%. The distribution of Kell phenotypes was comparable between men (4.38%) and women (4.11%), with the highest frequency in donors aged 27–52 years. Conclusions: The phenotypic distribution observed reflects national patterns and shows the genetic makeup of southern Chile. The low but important prevalence of Kell-positive donors emphasizes the need for systematic Kell antigen screening to prevent alloimmunization and improve transfusion safety.

1. Introduction

Blood transfusion persists as one of the most vital interventions in contemporary medicine; however, its safety is significantly dependent on a precise understanding of the antigenic landscape of erythrocytes. Exposure to foreign erythrocyte antigens may provoke alloimmune responses, whereby the recipient’s immune system generates antibodies against epitopes that are not present in their own cells [1]. Among the extensive array of blood group antigens, ABO, RH1, and Kell (KEL1) are acknowledged for their substantial immunogenic potential and their participation in severe hemolytic transfusion reactions [2,3,4]. Mapping the phenotypic distribution of these important antigens in specific populations is crucial for transfusion planning. It helps identify potential compatibility issues and reduces the risk of immune-mediated complications [5].

Blood consists of a liquid part called plasma and cellular components: erythrocytes and leukocytes, which are both cells, as well as cell fragments known as platelets. Erythrocytes have membranes containing lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins. Several of these membrane molecules serve as surface antigens, such as the RH1 antigen, Kell antigen (KEL1), and the ABO group [6]. The blood groups with the greatest influence on transfusion medicine are ABO, RH1, and Kell antigen (KEL1) due to their high immunogenicity and potential to cause severe hemolytic reactions [6,7,8].

Transfusions may result in alloimmunization, a process whereby the recipient’s immune system recognizes foreign antigens on transfused red blood cells and generates specific antibodies against them [1]. This phenomenon is particularly significant for highly immunogenic antigens such as those of the RH1 and Kell (KEL1), as it may complicate future transfusions by diminishing the availability of compatible blood and elevating the risk of delayed hemolytic reactions [9,10]. In clinical practice, alloimmunization may occur following repeated transfusions, organ transplants, or inadvertent exposure to incompatible blood [1,11]. Thus, identifying the antigenic frequency within a population helps to inform transfusion strategies aimed at minimizing the risk of alloimmunization and allows for the selection of highly compatible red blood cell units, particularly for patients who are already alloimmunized.

In this context, the goal of this research is to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the phenotypic frequency of the ABO, RH1 and especially Kell blood antigens in blood donations collected by blood banks in southern Chile. Using a detailed approach, we aim to gain a better understanding of the distribution of less-studied antigens like the Kell system within the population, exploring potential regional or demographic variations. This study adds to the field of hematology by providing accurate data that could be crucial for optimizing blood transfusion processes and enhancing the quality of medical care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the Centro de Sangre Concepción but restrictions apply to their access, as they were used under license for this study and are not publicly available. In Chile, blood typing and compatibility testing at donation centers are regulated by national rules issued by the Ministry of Health (MINSAL) through Norma General Técnica No 31 on Blood Banks and Transfusion Services (2016). These guidelines mandate serological testing for the ABO and RH1 antigens in all donors, in addition to screening for the K antigen (KEL1) due to its high immunogenicity and clinical significance in hemolytic disease of the newborn and transfusion reactions [12]. Other extended antigen determinations, such as RHCE antigen phenotyping (RH4, RH3, RH5, RH2) or weak D testing, are recommended solely for specific clinical circumstances, such as pregnant women, patients with a history of alloimmunization, or complex transfusion backgrounds, and are not routinely necessary for donor screening [12]. This regulatory framework describes the selection of the antigenic samples analyzed in this study and ensures comparability with national transfusion practices.

2.2. Sample Selection and Instrument

Samples from blood banks located in southern Chile, which make up the Southern Macronetwork of Transfusional Medicine, covering various regions to ensure broad representation, were selected. These included health services in Maule, Ñuble, Concepción, Talcahuano, Biobío, Arauco, and Araucanía Norte. All blood donations recorded at the Centro de Sangre Concepción in 2024 were included in this study. This dataset covers the entire year’s donations. To prevent multiple entries from the same donor, all repeated donations were consolidated so that only one donation per person was analyzed. This method ensured an unbiased and accurate estimation of phenotypic frequencies, providing a true representation of blood group antigen distribution in the regional donor population.

2.3. Study Design and Samples

Blood samples were obtained and processed in accordance with the regulations established by the Chilean Health Authority. All procedures adhered to current national standards for blood donor screening, handling, and laboratory analysis. Samples were collected at the Concepción Blood Center as part of routine donor phenotyping workflows.

2.4. ABO and RH Phenotyping

Phenotyping of ABO and RH antigens was performed using a standard plate hemagglutination technique. The following monoclonal reagents (Immucor, Immucor–Werfen, Barcelona, Spain) were used: immuClone Anti-A IgM (Code 66001), immuClone Anti-B IgM (Code 66002), immuClone Anti-AB IgM (Code 66003), immuClone Anti-D Rapid IgM (Code 66008), Novaclone Anti-D IgM + IgG Monoclonal Blend (Code 66036), and immuClone Rh-Hr Control (Code 66006). In addition, Referencells-2 (Group A1 and B; Code 2345, Immucor) were used as reference red cells for reverse typing. All procedures were carried out strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions provided by Immucor–Werfen.

2.5. Kell (KEL1) Phenotyping

Phenotyping of the Kell blood group antigen KEL1 was conducted using the same plate hemagglutination technique. The following reagents were used: immuClone Anti-Kell IgM (Code 66020, Immucor) and immuClone Rh-Hr Control (Code 66006, Immucor). The assay was performed strictly in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations provided by Immucor–Werfen.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis to characterize donors and to summarize phenotypic frequencies of the ABO, RH1, and Kell (KEL1). Categorical variables (sex, ABO group, RH1 status, Kell status, and combined phenotypes) were reported as counts and percentages relative to the total sample. No hypothesis testing or multivariable modeling was performed, as the study aimed to estimate distributions rather than compare groups. All computations and tabulations were performed in R (v4.3.1) and Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

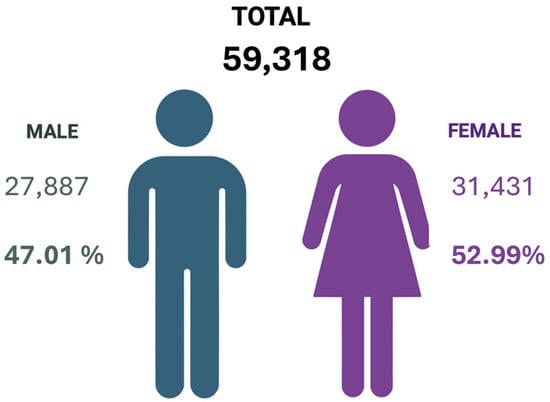

A total of 59,318 blood samples from donors delivered to the Centro de Sangre Concepcion during 2024 were analyzed. Based on the data collected, it was determined that the same number of donors was received during this period. The distribution of the studied population by sex is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution by sex of the total blood donations analyzed by the Centro de Sangre Concepción during the year 2024. Created in BioRender. Alarcón, S. (2025) (Accessed on 25 June 2025).

3.2. Antigen Prevalence by Blood Group System

Subsequently, the prevalence of ABO, RH1 and Kell blood groups was studied in the universe of samples collected by the Centro de Sangre Concepción during the period described above. Based on the information provided about ABO blood types, the data analysis showed that a high percentage of the collected samples belong to blood type O, while the blood type with the lowest frequency among the samples was type AB. All details regarding the total number of samples received in 2024 are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of phenotypic frequencies of ABO, RH1, and Kell blood group systems from southern Chile.

The information presented in Table 1 summarizes the overall distribution of phenotypic frequencies for the three major blood group systems—ABO, RH1, and Kell—in a cohort of 59,318 blood donors from southern Chile. As expected, group O was the most common (61.3%), followed by groups A (27.83%), B (9.02%), and AB (1.85%), reaffirming the well-described predominance of blood group O in Latin American populations. Regarding the RH1 system, 94.47% of donors were RH1-positive, while only 5.53% were RH1-negative. For the Kell system, the Kell-negative phenotype was highly prevalent (95.76%), whereas 4.24% of donors expressed the KEL1 antigen. Together, these findings underscore the predominance of O and RH1-positive phenotypes and highlight the low but clinically significant frequency of the KEL1 antigen—information that is essential for transfusion planning and for reducing the risk of alloimmunization in regional blood banks.

3.3. Combined Antigen Group Frequencies

Subsequently, a combined evaluation of the blood group antigens in this article was performed. Analyzing phenotypic combinations like ABO, RH1, and Kell is crucial for predicting incompatibilities, optimizing blood unit allocation, and guiding donor recruitment. This study maps their distribution among donors, revealing common and rare phenotypes. These insights enhance understanding of antigen diversity and its impact on transfusion safety. First, the association between the ABO/Rh samples in the collected samples was evaluated. The relationship between these samples is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of RH1 phenotype within ABO blood groups.

The information in Table 2 summarizes the combined distribution of the ABO and RH1 antigens, expressed as the eight possible phenotype combinations calculated relative to the total number of donors (n = 59,318). The results show that the O RH1+ phenotype was the most frequent, accounting for 57.8% of the total population, followed by A RH1+ (26.3%), B RH1+ (8.5%), and AB RH1+ (1.8%). The RH1-negative phenotypes were less common across all ABO groups, with O RH1− representing 3.4% of the total, A RH1− 1.5%, B RH1− 0.5%, and AB RH1− 0.1%.

Later, the association between the ABO and Kell (KEL1) antigens in the collected samples was then assessed. The relationship between these samples is illustrated in Table 3. Here, we present the distribution of the ABO and Kell (KEL1) antigens, also recalculated to reflect the eight phenotype combinations relative to the total sample. Similarly to the RH1 distribution, the O KEL1− phenotype was the most common (58.7%), followed by A KEL1− (26.6%), B KEL1− (8.6%), and AB KEL1− (1.8%). In contrast, the KEL1-positive phenotypes were infrequent, with O KEL1+ (2.6%), A KEL1+ (1.2%), B KEL1+ (0.4%), and AB KEL1+ (0.1%).

Table 3.

Distribution of Kell phenotype within ABO blood groups.

These results reinforce the predominance of KEL1-negative phenotypes (>95%) in all ABO groups and emphasize the low but clinically relevant presence of Kell-positive donors in the studied population. Together, the recalculated data provide a more detailed overview of the combined antigenic profiles, enhancing the capacity to predict transfusion compatibility and identify rare phenotypes within the regional donor pool.

To conclude this section, the relationship between the RH1 and Kell antigens in the sampled data was analyzed. The relationship between these samples is shown in Table 4. The data indicates that RH1 positive and KEL1-positive donors comprised 4.01% of the total sample, while RH1 negative and KEL1-positive donors accounted for 0.22%. Thus, the total number of positive KEL1 antigens reached 4.23%. The percentage of negative KEL1 antigens was 95.77%, both RH1+ and RH1−.

Table 4.

Distribution of Kell phenotype within RH1 groups.

3.4. Kell Antigen Prevalence by Sex and Age

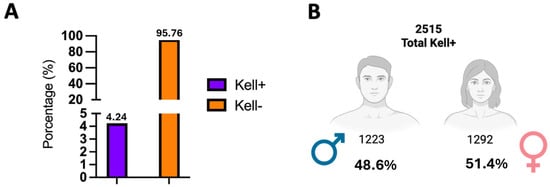

Later, we examined the prevalence of KEL1+ and KEL1− antigens by sex in the samples collected during 2024. Figure 2 shows that out of the total samples collected, only 4.24% are KEL1+, which corresponds to 2515 samples. When broken down by sex, 1223 K-positive donors came from men, while 1292 came from female donors (Figure 2). It is important to note that, to determine the frequency of the K antigen, an anti-K (KEL1) reagent was used; therefore, our study did not include the typing of the k antigen (Cellano) and it was not possible to discriminate between the KEL1+, KEL2+ and KEL1−, KEL2+ phenotypes within the K− group.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of K antigen (KEL1) by sex. (A) The figure shows the distribution of the positive and negative Kell phenotypes in 59,318 blood donors tested during 2024. In total, 4.24% of the samples were Kell positive (n = 2515). (B) Of these, 1292 were women (4.11% of the total females) and 1223 were men (4.38% of the total males). The negative Kell phenotype predominated widely in both sexes, exceeding 95%. These results demonstrate a relatively even distribution of the K antigen (KEL1) between men and women, with no clinically relevant differences.

Subsequently, the results of this analysis are shown in Table 5. In the female population, 4.1% were Kell-positive while 95.9% were Kell-negative. In the male population, the prevalence of Kell-positive was 4.38%, and 95.62% were Kell-negative.

Table 5.

Kell prevalence by sex.

Table 5 presents the distribution of the Kell phenotype among 59,318 blood donors, categorized by gender. In the female cohort (n = 31,431), 1292 individuals were KEL1-positive antigen (4.11%), while 30,139 were KEL1-negative (95.89%). Among the male cohort (n = 27,887), 1223 individuals tested KEL1-positive (4.38%), and 26,664 were KEL1-negative (95.62%). Overall, 2515 samples (4.24%) were KEL1-positive, whereas 56,803 (95.77%) were KEL1-negative. These findings indicate a consistent distribution of the Kell phenotype across genders, with no statistically significant differences observed in its prevalence.

Finally, Table 6 presents the distribution of Kell phenotypes among 59,318 blood donors, categorized by age groups. The age group of 27–52 years exhibited the highest proportion of Kell-positive donors (n = 1572; 62.5%), followed by the 17–26 years group (n = 615; 24.5%), and the age group of 53 years and above (n = 328; 13.0%). The Kell-negative phenotype was predominantly observed across all age ranges (≥95%). Overall, 2515 samples (4.24%) tested positive for Kell, confirming the low prevalence of the antigen within the study population and indicating that the majority of positive cases originate from donors in middle adulthood.

Table 6.

Kell prevalence by age group.

4. Discussion

This study used data from 59,318 blood donors collected by the Concepción Blood Center in 2024. It helped determine the phenotypic frequency of the ABO, RH1, and Kell blood group system in a large cohort of southern Chilean blood donors. In our study, we found that the distribution of ABO blood group components was dominated by phenotype O, comprising 61.3% of the samples. This was followed by phenotype A at 27.8%, phenotype B at 9%, and phenotype AB at 1.9%. This amount matches the report by the Public Health Institute, which indicates that the distribution of the O phenotype in the Chilean population is 59.89% [13] and other Latin American populations [14,15]. These results differ from those reported in studies conducted in other Latin American regions, such as Ecuador, where the O phenotype accounted for 75.46% [16], and in Bolivia, it reached 73% [17] of the samples analyzed, respectively. A study conducted in Mexico suggests that the differences in blood group distribution across regions could be partly explained by variations in ethnic makeup, including the proportion of indigenous populations [18].

A recent multicenter study conducted in Lima, Peru, involving 20,141 blood donors, reported that the majority of donors were men (69.5%), with a predominance in the 29–38-year age group (30.9%). Most donors were of Peruvian nationality (97.9%), while among foreign donors Venezuelans were the most frequent (1.5%). Regarding blood group distribution, the O Rh+ phenotype was by far the most common, representing 79% of the donors [19]. This genetic diversity should be taken into account when designing transfusion strategies and blood donation campaigns, as it directly impacts the availability and compatibility of blood components [19].

Regarding the RH1 system, the analyzed sample showed that the majority of the population is RH1 positive (94.47%), which is important information for transfusion planning and preventing alloimmunization. These findings are consistent with data from the Public Health Institute, which states that at the national level, the RH1 positive phenotype accounts for 94.4% of the country’s population [13]. This finding supports the stability of the RH1 system distribution in the population of the south-central region of the country, despite demographic and geographic diversity. In the Latin American context, our findings also align with other regional studies. For example, a study conducted in Mexico shows that the prevalence was 95.6% among a large donor cohort [15]. Similarly, studies conducted in Quito, Ecuador, and La Paz, Bolivia, report that 97.93% and 97.61% of the evaluated samples were Rh positive, respectively [16,17]. The low frequency of RH1 negative patients, although consistent, creates challenges in transfusion management because this group needs careful planning to ensure compatible units for RH1 negative individuals, especially women of childbearing age, where preventing anti-D alloimmunization is vital.

To enhance the historical and demographic context of our findings, we conducted a comparison between the observed phenotype frequencies and those documented within Indigenous and European-descendant populations. Research involving Aymara and Huilliche groups has reported a predominance of group O and RH1-positive phenotypes, aligning with Amerindian genetic heritage [20,21]. In contrast, European reference populations, especially those from Spain and the Basque Country, exhibit higher proportions of group A and a slight rise in Kell positivity, reflecting typical European genetic traits [15,22]. These contrasts correspond with genomic evidence suggesting that the Chilean population, particularly in the southern regions, possesses a substantial Amerindian component, mirroring historical admixture between Indigenous peoples and European settlers [23]. In this context, the antigenic landscape observed in our study not only provides valuable information for transfusion safety but also serves as biological evidence of Chile’s demographic and historical identity.

Finally, we found that out of 59,318 samples analyzed, 2515 were positive for the KEL1 antigen, which is a prevalence of 4.24%. Studies in the Chilean population show similar results in the frequency of KEL1-positive samples for the KEL1 antigen: 4% [24] and 4% [25]. A study conducted on a sample of 120 individuals from rural communities in the Coquimbo region reported a positive frequency of 2.47% for the Kell antigen [26]. According to the authors, this trend might result from racial mixing caused by colonization [26]. Studies in other regions of the Americas show that in Argentina the frequency of KEL1-positive samples positive for the KEL1 antigen is 6.21% [27], in Mexico it reaches 2% [28]. Interestingly, studies from other regions around the world show that the prevalence of the positive KEL1-positive antigen varies among different ethnic groups. A study conducted in Riyadh found that 14% of the samples from the Arab population tested positive for the KEL1 antigen [22].

With regard to the Kell system, its infrequent occurrence yet significant clinical relevance highlights the necessity for systematic antigen screening within blood banks. Although an initial analysis examined Kell phenotype frequencies by sex and age, these comparisons were subsequently omitted, as no biological or historical evidence has been reported to substantiate such differences within healthy donor populations. The Kell antigen (KEL1) is encoded on chromosome 7 (7q33), independent of sex-linked inheritance, and its expression remains consistent across various demographic groups [1,29]. Therefore, the discussion of the Kell system in this study centers on its clinical and population significance. The Kell-negative phenotype was predominant in our cohort, aligning with the pattern observed in other populations globally, where K+ frequencies generally range from 2% to 9% [15,22]. Beyond transfusion compatibility, these frequencies can be examined through the perspective of population genetics. As described earlier, indigenous population of Chile populations such as the Aymara and Huilliche exhibit a pronounced prevalence of O and RH1+ phenotypes, accompanied by notably low frequencies of Kell positivity, which reflects the strong Amerindian genetic heritage [20,21], while populations of European descent—especially those from Spain and the Basque Country—show higher frequencies of group A and a slightly increased prevalence of Kell-positive phenotypes [30,31].

From a clinical perspective, the Kell system remains recognized as one of the most immunogenic non-ABO antigens, with anti-K antibodies linked to severe cases of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). The successful implementation of preventive policies—such as the Netherlands’ comprehensive K-matched transfusion protocol for women under the age of 45—has led to a measurable decrease in anti-K alloimmunization rates and the occurrence of HDFN [32]. Within this framework, our findings emphasize the importance of incorporating routine Kell antigen typing into blood bank screening protocols nationwide in Chile, with a particular focus on prioritizing Kell-negative units for women of childbearing age and patients with prior alloimmunization.

Similarly, considering the implications of the Kell system for women of reproductive age, it is also crucial to address the obstetric aspect of immunohematologic risk. Current clinical guidelines highlight that routine prenatal screening for irregular red cell antibodies—especially anti-D and anti-K—is essential for preventing hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). According to the British Society for Haematology, all pregnant women should undergo ABO/RH1 typing and red-cell antibody screening at their first visit and again at 28 weeks because of the high risk associated with clinically significant antibodies like anti-D and anti-K [32,33]. Mechanistic and clinical studies also demonstrate that anti-K can suppress fetal erythropoiesis—rather than merely causing hemolysis—resulting in severe fetal anemia even at low titers [34]. Furthermore, national policy evaluations have shown that implementing K-matched transfusion strategies for women of reproductive age significantly reduces the incidence of anti-K–mediated HDFN [35]. Based on this evidence, our results highlight the need to strengthen antenatal antibody screening programs in Chile and to prioritize K-negative red blood cell units for pregnant women or those who might become pregnant.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the most comprehensive characterization to date of the phenotypic distribution of blood group antigens ABO, RH1, and Kell blood in southern Chile, encompassing over 59,000 blood donors. The predominance of group O and RH1-positive phenotypes reflects the strong Amerindian genetic contribution that historically shaped Chile’s population structure. In contrast, the low frequency of Kell-positive phenotypes (4.24%) aligns with regional data and supports the notion of limited European admixture in southern regions. These findings not only offer valuable insights into the biological diversity of Chile’s population but also have direct implications for transfusion safety. Given the high immunogenic potential of Kell antigens, systematic Kell typing should be integrated into donor screening—especially for women of reproductive age—to prevent alloimmunization and hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. The observed antigenic distribution also provides a foundation for improving transfusion protocols, optimizing inventory management, and anticipating regional blood compatibility needs. In a broader context, our data contribute to understanding the intersection between population genetics, clinical transfusion practice, and historical ancestry in Chile and South America.

Therefore, we recommend that blood banks in Chile update their Good Practice Guidelines to include (1) systematic Kell antigen screening in all donors; (2) targeted recruitment of Kell-negative donors, particularly for women of childbearing age; and (3) implementation of regular irregular antibody screening programs for both donors and recipients.

In addition to transfusion-related concerns, our findings highlight the need to strengthen antenatal immunohematologic screening in Chile. Considering the high clinical significance of anti-D and anti-K antibodies in hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn, routine ABO/RH1 typing and red-cell antibody screening during pregnancy—along with prioritizing Kell-negative red blood cell units for women of reproductive age—should be adopted into national protocols. Incorporating these measures into obstetric care would help lower alloimmunization rates and enhance maternal–fetal safety, aligning Chilean practices with international standards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R., M.M. and M.Á.M.; methodology, M.M. and M.Á.M.; software, C.R. and S.A.; validation, C.R., M.M. and M.Á.M.; formal analysis, C.R. and S.A.; investigation, C.S.-E., B.L. and P.W.; resources, M.M. and M.Á.M.; data curation, C.R., M.M. and M.Á.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.-E., B.L. and P.W.; writing—review and editing, C.R. and S.A.; visualization, C.S.-E., B.L. and P.W.; supervision, B.R. and S.A.; project administration, C.R. and S.A.; funding acquisition, B.R., C.R. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Scientific Ethics Committee of Universidad San Sebastián, after reviewing the background information issued on 12/11/2024, a ‘Certificate of Exemption from Review No. 193-24’.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the data used in this study were provided in anonymized form, making it impossible to identify individual participants. The Centro de Sangre Concepción obtained informed consent for blood collection and initial testing in accordance with Chilean national regulations and institutional ethical standards.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

To San Sebastián and the Escuela de Medicine, Tres Pascualas Campus, Concepcion, USS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arthur, C.M.; Stowell, S.R. The Development and Consequences of Red Blood Cell Alloimmunization. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2023, 18, 537–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G.; Bublitz, M.; Steiert, T.A.; Löscher, B.-S.; Wittig, M.; ElAbd, H.; Gassner, C.; Franke, A. A structure-based in silico analysis of the Kell blood group system. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1452637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Patra, K.; Marandi, M.M. Prevalence of Kell Blood Group Antigens among Blood Donors & Impact of its Alloimmunization in Multi-transfused Thalassemia & Sickle Cell Disease Patients with Recommendation of Transfusion Protocol—Need of the Hour. J. Med. Sci. Health 2023, 9, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ristovska, E.; Bojadjieva, T.M.; Velkova, E.; Dimceva, A.H.; Todorovski, B.; Tashkovska, M.; Rastvorceva, R.G.; Bosevski, M. Rare Blood Groups in ABO, Rh, Kell Systems–Biological and Clinical Significance. Prilozi 2022, 43, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Beshlawy, A.; Salama, A.A.; El-Masry, M.R.; El Husseiny, N.M.; Abdelhameed, A.M. A study of red blood cell alloimmunization and autoimmunization among 200 multitransfused Egyptian β thalassemia patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinja, N.; Narain, R. ABO, Rh, and kell blood group antigen frequencies in blood donors at the tertiary care hospital of Northwestern India. Asian J. Transfus. Sci. 2020, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuran, O.; Al-Mehaisen, L.; Qasem, R.; Alhajji, S.; Al-Abdulrahman, N.; Alfuzai, S.; Alshaheen, S.; Al-Kuran, L. Distribution of ABO and Rh blood groups among pregnant women attending the obstetrics and gynecology clinic at the Jordan University Hospital. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, T.; Fatima, M.; Noureen, S.; Javed, S.; Abdulsattar, S.; Shahid, F.; Abiha, U.; Shakeel, R.; Noureen, N.; Maqbool, U.; et al. Kell Blood Group System: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Preprint, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Hao, X.; Gao, W.; Wang, Q. Research progress in RBC alloimmunization. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1677581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumee, B.; Devi, A.M.S.; Sitalakshmi, S. Prevalence of ABO, Rh (D, C, c, E, and e), and Kell (K) antigens in blood donors: A single-center study from South India. Asian J. Transfus. Sci. 2024, 18, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makroo, R.N.; Agrawal, S.; Chowdhry, M. Rh and Kell Phenotype Matched Blood Versus Randomly Selected and Conventionally Cross Matched Blood on Incidence of Alloimmunization. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2017, 33, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud de Chile (MINSAL). Norma General Técnica No. 31: Bancos de Sangre Y Servicios de Transfusión; Departamento de Sangre y Tejidos: Santiago, Chile, 2016; Available online: https://www.sochihem.cl/bases/arch1087.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Depto Biomédico Nacional y de Referencia, Depto Asuntos Científicos. Informe de Resultados del Estudio de Indicadores Inmunohematológicos en Población CHILENA Año 2015; Depto Biomédico Nacional y de Referencia; Depto Asuntos Científicos: Santiago, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Fonseca, J. Frecuencia de los grupos sanguíneos ABO y Rh en la población laboral del valle de Aburrá y del cercano oriente de Antioquia. Acta Médica Colomb. 2006, 31, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Canizalez-Román, A.; Campos-Romero, A.; Castro-Sánchez, J.A.; López-Martínez, M.A.; Andrade-Muñoz, F.J.; Cruz-Zamudio, C.K.; Ortíz-Espinoza, T.G.; León-Sicairos, N.; Llanos, A.M.G.; Velázquez-Román, J.; et al. Blood Groups Distribution and Gene Diversity of the ABO and Rh (D) Loci in the Mexican Population. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1925619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, I. Prevalence of ABO and Rh blood groups in the city of Quito-Ecuador. Rev. San Gregor. 2022, 1, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Navia-Bueno, M.; Farah-Bravo, J.; Yaksic-Feraude, N.; Espinoza-Pinto, V.; Salamanca-Kasic, M.; Philco-Lima, P.; Alis, N.M.; Valeria, S.V. Frequency of bloods groups ABO and Rh factor in residents high altitud La Paz-Bolivia. Cuad. Hosp. Clín. 2024, 65, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Buentello-Malo, L.; Peñaloza-Espinosa, R.I.; Salamanca-Gómez, F.; Cerda-Flores, R.M. Genetic admixture of eight Mexican indigenous populations: Based on five polymarker, HLA-DQA1, ABO, and RH loci. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2008, 20, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovera-Ancajima, C.d.P.; Cumpa, L.Y.C.; Lezama-Cotrina, I.D.; Walttuoni-Picón, E.; Cárdenas-Mendoza, W.W.; Culqui-García, J.E.; Retuerto-Salazar, W.R.; Poma, R.C.C. Phenotypic Identification of Blood Groups in Blood Donors: A Peruvian Multicenter Analysis. J. Blood Med. 2025, 16, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llop, E.; Henríquez, H.; Moraga, M.; Castro, M.; Rothhammer, F. Brief communication: Molecular characterization of O alleles at the ABO locus in Chilean Aymara and Huilliche Indians. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2006, 131, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, G.A.; Sutton, H.E.; Raul, B.E.; Swanson, J.; Robinson, A. Distribution of hereditary blood groups among Indians in South America. IV. In Chile with inferences concerning genetic connections between Polynesia and America. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1967, 27, 157–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalshaikh, M.; Almalki, Y.; Hasanato, R.; Almomen, A.; Alsughayir, A.; Alabdullateef, A.; Sabbar, A.; Alsuhaibani, O. Frequency of Rh and K antigens in blood donors in Riyadh. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2022, 44, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyheramendy, S.; Martinez, F.I.; Manevy, F.; Vial, C.; Repetto, G.M. Genetic structure characterization of Chileans reflects historical immigration patterns. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes, L.; Valenzuela, C.; Cruz Coke, R.; Armanet, L.; Lyng, C.; Harb, Z. Caracterización genética de la población hospitalaria de Santiago. Rev. Med. Chil. 1988, 116, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, M.; Castillo, D.; Pavez, Y.; Maldonado, M.; Mena, A. Frecuencia de antígenos del sistema sanguíneo Rh y del sistema Kell en donantes de sangre. Rev. Cuba. Hematol. Inmunol. Hemoter. 2015, 31, 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña, P.M.; Llop, R.E.; Rothhammer, E.F. Composición genética de la población chilena: Las comunidades urales de los valles de Elqui, Limarí y Choapa. Rev. Med. Chil. 2000, 128, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, N.; Fernández, C.; Orellana, S.; Villanueva, M.; Núñez Harris, E.; Romero, M.; Molina, L.; Mestra Campos, B.; Barañano, M.C.; Miguez, G.S. Prevalencia de los antígenos del sistema kell en los donantes de sangre en un hospital del conurbano bonaerense. Rev. Argent. Transfus. 2021, 48, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Chargoy-Vivaldo, E.; Azcona-Cruz, M.; Ramírez-Ayala, R. Prevalencia del antígeno Kell (K+) en muestras obtenidas en un banco de sangre. Rev. Hematol. Mex. 2016, 17, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, S.; Khan, A.; Kumar, R.; Das, B.; Singh, N.; Nayan, N.; Lahare, S. Frequency of Rh and Kell antigens among blood donors: A retrospective analysis from a tertiary care center in Eastern India. J. Hematol. Allied Sci. 2024, 3, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopetegi, I.; Muñoz-Lopetegi, A.; Arruti, M.; Prada, A.; Urcelay, S.; Olascoaga, J.; Otaegui, D.; Castillo-Triviño, T. ABO blood group distributions in multiple sclerosis patients from Basque Country; O-as a protective factor. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2019, 5, 2055217319888957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Culla, M.; Roncancio-Clavijo, A.; Martínez, B.; Gorostidi-Aicua, M.; Piñeiro, L.; Azkune, A.; Alberro, A.; Monge-Ruiz, J.; Castillo-Trivino, T.; Prada, A.; et al. O group is a protective factor for COVID19 in Basque population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, F.; Veale, K.; Robinson, F.; Brennand, J.; Massey, E.; Qureshi, H.; Finning, K.; Watts, T.; Lees, C.; Southgate, E.; et al. Guideline for the investigation and management of red cell antibodies in pregnancy: A British Society for Haematology guideline. Transfus. Med. 2025, 35, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Qureshi, H.; Massey, E.; Needs, M.; Byrne, G.; Daniels, G.; Allard, S. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guideline for blood grouping and red cell antibody testing in pregnancy. Transfus. Med. 2016, 26, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, J.I.; Manning, M.; Warwick, R.M.; Letsky, E.A.; Murray, N.A.; Roberts, I.A.G. Inhibition of Erythroid Progenitor Cells by Anti-Kell Antibodies in Fetal Alloimmune Anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luken, J.S.; Folman, C.C.; Lukens, M.V.; Meekers, J.H.; Ligthart, P.C.; Schonewille, H.; Zwaginga, J.J.; Janssen, M.P.; van der Schoot, C.E.; van der Bom, J.G.; et al. Reduction of anti-K-mediated hemolytic disease of newborns after the introduction of a matched transfusion policy: A nation—Wide policy change evaluation study in the Netherlands. Transfusion 2021, 61, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).