Abstract

Background: Malignant lymphomas are among the most common hematological neoplasms and include a heterogeneous group of entities characterized by distinct morphology, immunophenotype, genetics, and clinical features. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics have significantly improved our understanding of the genetic lesions and mechanisms underlying lymphomagenesis. Methods: This review summarizes key developments in molecular pathology relevant to B-cell lymphomas, including updates from the World Health Organization classification and recent progress in genomic, immunophenotypic, and clinical assessment. We highlight findings from next-generation sequencing studies and other molecular approaches used in routine and research settings. Results: Many molecular alterations are now routinely incorporated into diagnostic criteria and influence risk stratification, prognosis, and treatment selection. Although not all lesions are evaluated in everyday clinical practice, several changes have demonstrated prognostic significance and therapeutic relevance. Molecular subclassification has refined our ability to predict clinical behavior and response to targeted therapies. Conclusions: Advances in molecular diagnostics continue to reshape the clinical approach to lymphomas. Improved classification, better identification of therapeutic targets, and more accurate prognostic tools collectively enhance personalized treatment strategies. As a result, molecular tools increasingly guide clinical decision-making and contribute to improved outcomes in patients with B-cell lymphomas.

1. Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) account for approximately 4% of all diagnosed cancers and are the most common hematopoietic tumors. Of these, B-cell NHL accounts for about 80% of all lymphoid tumors, followed by Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) (8%) and T-cell/Natural Killer-cell tumors (T/NK tumors) (12%). The most common subtype of NHL is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which accounts for about 25–30% of all NHL cases [1,2].

Gene mutations can cause NHL at virtually every phase of lymphocyte differentiation; as a result, many subtypes of lymphomas share similarities with their non-cancerous (cell of origin/normal counterpart) equivalents.

The morphological and immunophenotypic similarities are essential for the diagnosis and classification of lymphomas [3]; due to variations in clinical presentation, NHL can be also described as aggressive or indolent. Aggressive B-cell lymphomas encompass, but are not restricted to, DLBCL, nodal T-cell lymphomas and Burkitt lymphoma (BL), while indolent lymphomas comprise various other entities, including follicular lymphoma (FL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma (LPL). Notably, certain entities, like mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), may manifest with either an aggressive or indolent clinical course [2,4].

According to World Health Organization (WHO) classification, the integration of morphology, immunophenotype, molecular genetics and clinical characteristics is necessary to properly diagnose and classify all the hematopoietic tumors.

Although the clinical features, morphology and immunophenotype of lymphomas serve as the basis for the diagnosis and classification of lymphomas, recently more attention has been paid to identifying changes occurring in them from a genetic point of view. The WHO [5] regularly revises the classification of lymphoid neoplasms to add clinical and molecular advances, such as the increasing number of important genetic alterations observed in these diseases. In fact, almost all subtypes of lymphoma exhibit various genetic changes, such as chromosomal changes, somatic mutations, as well as epigenetic changes. Recognizing these phenomena is clinically important for diagnosis and because they may help guide targeted therapy [6]. The Variable, Diversity and Joining (VDJ editing) of immunoglobulin genes in the bone marrow as well as the somatic hypermutation and class switching of immunoglobulin in germinal centers are currently considered main determinants of B-cell lymphomagenesis, by facilitating the occurrence of genetic lesions [3,7]. In this article, the authors reviewed the most recent literature concerning the molecular genetics of aggressive B-cell lymphomas, focusing on diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

2. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (B-NHL) worldwide [8]. The diagnosis and classification of DLBCL have significantly advanced over time. Initially, it only involved evaluating the morphology based on a single hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) slide. However, it now requires several other tests, including immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, flow cytometry and molecular testing. Although these technologies enable improvements in diagnostic subtyping, the disease’s very diverse nature still poses challenges for complete subtyping. Moreover, it is imperative to persist in comprehending the fundamental molecular pathophysiology of the disease, considering its tendency to return despite conventional and even targeted therapy. This study aims to present a comprehensive analysis of the past and present status of DLBCL molecular subtyping. Moreover, we examine recent studies that enhance our comprehension of the pathophysiology of DLBCL and investigate evidence of the interactions between this entity and its surrounding milieu.

2.1. Gene Expression Profiling

Until recently, the identification of liquid cancers relied on the examination of their physical characteristics, immunohistochemical studies and cytogenetics. The initial categorization of DLBCL into molecular subtypes was introduced with the introduction of DNA microarrays, a technique that enables the simultaneous investigation of several expressed genes. This technology, known as DNA microarray, enabled the examination of gene expression patterns in a liquid cancer termed DLBCL. The study conducted by Alizadeh et al., using a tool called Lymphochip, classified DLBCL into different subtypes based on the origin of the cells involved. This study was a significant contribution to the understanding of the molecular aspects of DLBCL. This achievement led to the classification of around 80–85% of all DLBCL cases into biological subtypes. Importantly, it demonstrated that the prognostic values of these subtypes were higher than those of the conventional clinical predictor, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) [5,9,10].

This was later validated by independent and larger studies, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) was accepted as a surrogate marker for the identification of the so-called cell of origin (COO) of DLBCL, with relevant prognostic impact [10,11]. It was shown that GEP patterns are correlated with the likelihood of achieving long-term responses to the R-CHOP scheme (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone). Rosenwald et al. [12] found genetic signatures that are particular to certain cells and others that are not specific to cells. These signatures vary depending on the response to traditional chemotherapies. Irrespective of molecular prognostication and subtyping, molecular study was bound to yield a growing number of precise treatment targets by analyzing biochemical pathways [11,12,13,14]; research conducted using mouse models further corroborated the molecular concepts arising from gene expression profiling (GEP).

Although standard CHOP and R-CHOP have achieved some level of success and there are more novel agents available, the problem of heterogeneity and emergence of drug resistance persists. This is evident from the variable treatment responses and relapses, even after considering COO subtyping. Despite its increasing popularity and effectiveness, there were concerns that the GEP could not accurately recapitulate the underlying abnormal genetic programming, including the presence of major additional genomic events, such as MYC and BCL2 translocations (see below). In addition, in practice, there were other technical obstacles that prevented the early clinical use of GEP in the routine subcategorization of DLBCLs. One such obstacle was the logistical requirement for fresh tissue specimens. At first, overcoming this phase was challenging. However, numerous innovative testing methods, such as those proposed by Nanos Tring [12], HTG [13] and Roche [15], were eventually able to overcome this obstacle. These alternatives facilitated the utilization of formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissues, aligning with the typical pathologic workflow and enabling an expansion in the number of analytical cases that could be examined. Nonetheless, immunohistochemistry remained the most widely used tool to assess DLBCL COO. Of note, the term COO, despite being widely used and accepted, should be better replaced with a “normal counterpart”. In fact, neoplastic cell phenotype represents a specific stage of differentiation (in this case, germinal center B-cells in earlier or later stages of advancement through the follicle) rather than the cell from which the process had originated (e.g., multiple myeloma cells obviously resemble plasma cells that are their normal counterparts but not their origin).

2.2. Cytogenetics and/or Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

Cytogenetics and FISH investigations have a role in identifying anomalies associated with DLBCL and are also used to rule out more aggressive high-grade lymphomas, such as double- or triple-hit lymphomas (the latter no longer included in the most recent classification). These necessitate a minimum reorganization of the MYC gene and BCL2. In the past, the detection of MYC rearrangements in DLBCL was often done when there were noticeable high-grade morphologic characteristics or high proliferation rates. Nevertheless, these characteristics are not consistently effective in distinguishing double-hit or triple-hit lymphomas [16]. The Royal College of Pathologists (UK) implemented a more streamlined algorithmic technique, as described in the 2015 lymphoma dataset [17]. This approach suggests conducting FISH testing for MYC and BCL2. It is advised to carry out MYC FISH +/− BCL2 FISH or BCL2 IHC testing if the cell of origin belongs to the GCB subtype. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) has implemented similar criteria, stating that MYC immunohistochemistry (IHC) can be useful in predicting MYC translocations, which can then be confirmed using FISH [18]. Overall, several studies indicated that DLBCL cases with MYC and BCL2 abnormalities and, in part, MYC and BCL2 IHC over-expression, had the most adverse prognoses.

2.3. DLBCL Classification Based on Genetic Profile

DLBCL oncogenic drivers were mapped using full exome sequencing and transcriptome sequencing [19,20]. These studies revealed the presence of oncogenic driver mutations in genes including EZH2 and MYD88, which facilitated the development of lymphoma [21]. Concurrently, in the field of molecular subclassification, there were other challenges related to analysis, such as the establishment and integration of various platforms (e.g., whole-exome sequencing and RNA sequencing), which were necessary to accurately detect different types of genetic abnormalities, including mutations, translocations and changes in the number of copies of genes [22,23].

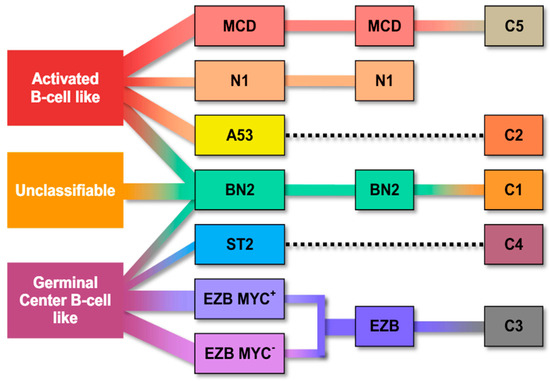

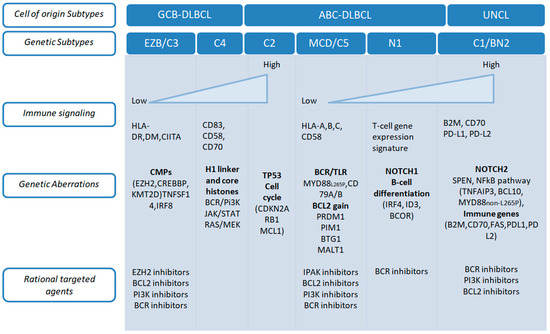

Chapuy et al. [22] used genomic methods to identify rare genetic changes, recurring mutations, changes in the number of copies of genes and structural variations in DLBCL. They also created five distinct genetic patterns to further classify DLBCL (Figure 1). C1 was associated with NOTCH2 mutations and had a favorable outcome. C2 had frequent CDKN2A deletion, biallelic TP53 loss of function and was associated with a worse clinical course. C3, by contrast, was related to mutations affecting epigenetic modifiers (KMT2D, CREBBP and EZH2), BCL2::IGH translocation and PTEN aberrations, still with unfavorable outcome. C4 was associated with BCR-PI3K, NF-κB or RAS-JAK signal transducer, and had aberrations in the BRAF and STAT3 pathways, histone gene mutations and possible immune escape (expression of CD83, CD70 and CD58), but more favorable clinical course. C5 is defined by the presence of mutations affecting CD79B, BCL2, PRDM1, MYD88L265P and PIM1 with unfavorable outcome. The predictive ability of the subtypes was similarly unaffected by the clinical gold standard International Prognostic Index (IPI) [22].

Figure 1.

Molecular classification systems of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to gene expression profiling and the potential relationship between the molecular entities and the cell of origin groups [24]. EZB: EZH2 mutation/BCL2 translocation–enriched cluster; MYC+: cases with MYC rearrangement; EZB MYC+: EZB subtype with MYC rearrangement.

Schmitz et al. [23] used their GenClass algorithm to simultaneously characterize four subsets of DLBCL. These subsets are called MCD (MYD88L265P, CD79B co-mutation), BN2 (BCL6 fusions or NOTCH2 mutation), N1 (NOTCH1 mutations) and EZB (EZH2 mutation or BCL2 translocation). The classification was based on a more uniform set of genomic abnormalities (Figure 2). Remarkably, they successfully identified specific targets within the subtypes that carry a high risk. For instance, they found that MCD may have a stronger response to ibrutinib due to constant BCR signaling [23].

Figure 2.

Genetic lesions associated with distinct transcriptional and genetic subtypes of DLBCL [25].

The Chapuy C1, C3 and C5 clusters exhibited overlap with the Schmitz GenClass BN2, EZB and MCD groupings, respectively, when compared. The Chapuy C2 and C4 subtyping were distinct from all other Schmitz subtyping, with no overlap. These discrepancies may have been considered less important than variations in bioinformatic analytical methods [22].

Wright et al. used previous molecular classifications to create a probabilistic definition of seven genetic subtypes of DLBCL, using LymphGen. These subtypes were determined based on specific genes that predict the subtype, such as mutations, copy number alterations and fusions. Each subtype had different gene expression profiles (GEPs), immune microenvironments and outcomes after immunochemotherapy. The algorithm, known as LymphGen, was made available to the public. It uses a Bayesian prediction model to classify tumors into seven different genetic subtypes: MCD, N1, A53, BN2, ST2, EZB/MYC+ and EZB/MYC-. It also identifies specific genetic characteristics and precision drug targets for each subtype. The researchers examined the impact of blocking specific biochemical pathways identified in their analysis by using loss-of-function CRISPR/Cas9 on cell lines that mimic each of the seven subtypes. This facilitated more investigation into the tumor’s inherent development and a more comprehensive comprehension of the potential medication impacts on the established biochemical pathways [26].

Curiously, some subtypes of DLBCL identified byLymphGen exhibited some features characteristic of indolent lymphomas. Follicular lymphomas were characterized by EZBs, marginal zone lymphomas by BN2, and ST2 lymphomas by signatures resembling both nodular lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin’s lymphoma and T-cell-rich, histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.

Significantly, the MCD subtypes had genetic characteristics that suggested the presence of immune evasion mechanisms, with many them being in immune privileged areas [26]. The authors contend that their findings support the notion that the occurrence of various genetic alterations, such as the disruption of MHC class I, T and/or NK cell activation, was necessary for evading immune surveillance and enabling growth in immune-protected areas [27].

Each subtype of the disease showed distinct variations in how it responded to the standard R-CHOP treatment. Additionally, specific molecular targets were identified that could potentially be targeted by existing precision drugs. These targets include Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) inhibitors (BN2, MCD, A53), lenalidomide (MCD, BN2), BET inhibitors (MCD, BN2), JAK1 inhibitor (MCD), IRAK4 (MCD), EZH2 inhibitors (EZB with EZH2 mutations), venetoclax or navitoclax (MCD) [26].

3. High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma

In the latest edition of the WHO Classification (2022), two entities were recognized as distinct from DLBCL-NOS, namely high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) not otherwise specified (NOS) and DLBCL/HGBCL with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements (so-called double-hit/DH lymphomas) [1,2].

The genetic features of DLBCL/HGBCL-DH are rather uniform and comparable to those of FL, containing numerous molecular anomalies in BCL2, KMT2D, CREBBP, TNFRS14 and EZH2. Multiple recent investigations have documented cases of DLBCL with a GEP that closely resembles that of HGBCL (DH-like GEP signature) [28,29]. These cases also have common mutations in MYC, BCL2, DDX3X, TP53 and KMT2D [30], as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genetic features and common mutations in Burkitt lymphoma (BL), double-hit lymphoma (DH) and DLBCL-NOS.

Lymphoid neoplasms that have both MYC and BCL6 rearrangements are currently classified as a subtype of DLBCL/NOS, or HGBCL/NOS, both their GEP and clinical behavior being quite different from those of DLBCL/HGBCL-DH.

HGBCL-NOS is classified as a distinct subtype that encompasses cases that do not fit into any other categories. From a molecular standpoint, this category includes activated B-cell lymphomas that have mutations in MYD88, CD79B or TBL1XR1, making it a diverse group. TP53 and KMT2D are the most frequent mutations. Gene expression analysis revealed that almost 50% of the cases of HGBCL-NOS contain the DH-like GEP profile that has been previously characterized [29,30,31].

Ennishi et al. [30] employed targeted resequencing, whole-exome sequencing, RNA sequencing and immunohistochemistry to create a gene expression signature (DHITsig) capable of differentiating between DLBCL/HGBCL-DH and GCB-DLBCL. Sha et al. [29] discovered a category called molecular high grade (MHG) that had gene expression patterns that fall between those of DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma. Remarkably, DHITsig revealed that at least 19% of DLBCL/HGBCL-DH tumors were undetectable by FISH, indicating their cryptic nature [31].

Of note, Wright et al. improved the DHIT signature by specifically targeting GCB cases with worse outcomes in the field of double- and triple-hit lymphomas. According to their suggestion, EZB-MYC subtypes undergo progressive somatic genetic abnormalities that lead to the development of EZB-MYC+ subtypes. It is worth noting that only 38% of EZB-MYC+ patients exhibit both MYC abnormality and a BCL2 translocation. Ultimately, the study demonstrated that in cases of GCB without EZB mutations, there was no negative correlation between DHITsig and outcomes [26]. Recent genomic and transcriptomic studies have further refined the biological spectrum of high-grade B-cell lymphomas, particularly HGBCL, NOS. A recent functional-genomic analysis of 55 HGBCL, NOS cases with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma gene expression signatures revealed high genomic complexity and frequent alterations in genes involved in B-cell activation (CD79B, MYD88, PRDM1, CARD11), epigenetic regulation (KMT2D, TET2) and cell-cycle control (TP53, CDKN2A, RB1). Copy-number changes affecting BCL6, REL and STAT3 were also common, underscoring the marked genetic heterogeneity of HGBCL, NOS and its overlap with both de novo DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma [32]. These findings provide further insight into the natural progression of DLBCL and the histologic phenomenon where diagnostic evidence of multiple lymphomas was found in the same specimen (referred to as composition [32], or evidence of clonal evolution from an indolent tumor (known as transformation) could be documented [33].

4. Adding New Agents to Conventional Chemo-Immunotherapy Based on DLBCL Biology

There was a strong expectation that the advancement of molecular GEP would have a substantial impact on the classification of prognostic DLBCL, which would then allow for customized therapy approaches. However, most attempts yielded inconsistent results.

R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) has been the established treatment for untreated DLBCL for the past twenty years. The molecular subtyping of DLBCL has suggested that tailoring treatment to specific subtypes could enhance response rates, particularly for patients who do not achieve complete remission or experience disease relapse (about 40% of those treated with R-CHOP) [34]. Ibrutinib, an innovative oral drug that inhibits Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) through covalent bonding, demonstrates selective effectiveness in activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL [35]. A randomized multicenter trial [29] aimed to assess whether the inclusion of ibrutinib would enhance the effectiveness of R-CHOP in ABC DLBCL. Notably, the inclusion of ibrutinib in R-CHOP treatment resulted in enhanced event-free survival and overall survival rates among patients under the age of 60. Regrettably, those over the age of 60 experienced a higher incidence of severe side effects when treated with a combination of ibrutinib and R-CHOP. It is important to mention that the process of molecular subtyping resulted in a delay of 27 days in reaching a diagnosis, perhaps leading to the exclusion of patients who need emergency treatment. This study demonstrates the potential of implementing subtype-specific treatment and emphasizes the importance of timely diagnostic results when incorporating molecular subtyping. Furthermore, the PHOENIX study consistently showed better results in younger patients who received a combination of ibrutinib and R-CHOP treatment. Additionally, there was improved overall survival in particular molecular subgroups, such as MCD and N1, as compared to treatment with R-CHOP alone [36]. In a study conducted by Landsburg and his colleagues, it was discovered that the use of ibrutinib as a single treatment resulted in a 60% rate of positive response in patients with a non-germinal center and the MYC and BCL2 double expressor phenotype who had relapsed or were refractory [37].

The ROBUST study is a phase 3 clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of adding lenalidomide to R-CHOP therapy compared to R-CHOP therapy alone for treating the ABC subtype of DLBCL. Historically, ABC-type DLBCL has exhibited resistance to standard R-CHOP therapy. However, recent phase 2 trials are indicating potential benefits of incorporating lenalidomide into R-CHOP (R2-CHOP) for ABC-type treatment. The main objective of the study was to assess the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients who received R2-CHOP, in comparison to those who only received R-CHOP. While the hazard ratio for PFS was 0.85, the median PFS was not determined for either group. R2-CHOP demonstrated a tendency to be more beneficial, but also more toxic, in patients with higher-risk diseases. The ROBUST research was the first phase 3 trial to use gene expression profiling to identify COO-based biomarkers in patients with ABC-DLBCL, and it demonstrated a consistent safety profile of R2-CHOP [38].

Davies et al. (REMoDL-B) were the pioneers in demonstrating the feasibility of using GEP for prospective treatment assignments [39]. Nevertheless, the outcomes of their randomized phase 3 clinical trial were unsatisfactory. GEP and functional studies did indicate that ABC-DLBCL largely relies on nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kB) activation to survive. Therefore, targeting NF-kB with specific inhibitors as well as with proteasome inhibitors (that, among others, target NF-kB) had a strong rationale for clinical applications. However, the larger clinical trials failed to demonstrate a significant benefit in terms of overall survival for ABC DLBCLs [39]. It should be underlined, in addition, that targeting NF-kB may have significant side effects as several cell types do rely on its activation.

Remarkably, a recent study provided the first evidence that targeted therapy combination can be safely and effectively administered before chemotherapy [40]. Specifically, non-GCB-like DLBCL patients were treated with two course of rituximab, lenalidomide and ibrutinib (RLI) before adding conventional chemo [40]. This approach induced an overall response rate after two cycles of RLI of 86.2%, and a complete response rate at the end of RLI chemotherapy of 94.5%.

Updated real-world clinical data also highlights promising advances in targeted therapy for genetically defined DLBCL subtypes. A 2024 single-center study evaluating BTK inhibitors combined with immunochemotherapy in newly diagnosed MYD88-mutated and/or CD79B-mutated DLBCL demonstrated a 100% overall response rate and markedly improved 1-year progression-free survival compared to standard therapy. Although ctDNA-guided treatment selection was not assessed, these findings reinforce the therapeutic relevance of molecular profiling in MCD-type DLBCL [41].

5. Burkitt’s Lymphoma

Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) is a particularly aggressive form of NHL that is characterized by the fast growth of mature B-cells [1,2,42]. Adult lymphomas include just 1–2% of cases, although it is a frequently occurring kind of cancer in children [43].

The WHO classifications used recognize three BL clinical variants: endemic, non-endemic or sporadic, and immunodeficiency-related. These variants have been identified historically. The three subtypes exhibit equal morphological and immunophenotypical characteristics, although they differ in terms of clinical and epidemiological aspects [1,2,44]. Pathological characteristics are common to all clinical variations. In the latest edition of lymphoma classification, this distinction has been replaced by a simpler division of BL based on the presence of EBV. Nonetheless, it should be kept in mind that specific factors are associated with BL in different settings, such as malaria in the formerly called endemic BL.

One characteristic that distinguishes BL is the constant increase in the amount of MYC due to a rearrangement of this cancer-causing gene with one of the three immunoglobulin genes found on chromosomes 14, 2 and 22. These translocations are responsible for approximately 80%, 15% and 5% of cases, respectively. Translocations commonly associated with lymphoma, such as BCL2 and BCL6, are not found in this particular condition [2,42]. Nevertheless, the dysregulation of MYC alone is insufficient for the development of lymphoma. Consistently, other genomic changes can be identified [45,46].

It is crucial to address the challenge of distinguishing BL from other HGBCLs in clinical practice. Studies analyzing GEP have identified a unique BL signature, establishing it as a separate and distinct entity [47,48,49]. Several studies have shown that the genetic landscape of Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) involves the GEP of early centroblasts, tonic BCR-PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling and disruptions in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis [47,48,49]. These processes play crucial roles in the development of BL. Recurrent mutations that deactivate tumor-suppressor genes, including TP53, CDKN2A and DDX3X, are commonly found in BL [46,50,51]. Furthermore, the inactivation of TP53 has been identified as a potential prognostic biomarker due to its higher occurrence in patients who do not respond well to treatment [50]. Similarly, the greater occurrence of BL in males can be partly attributed to inactivating changes in DDX3X. DDX3X mutations that result in loss of function have a moderating effect on global protein synthesis driven by MYC. Malignant cells that have already formed restore their full ability for protein synthesis by expressing their Y chromosomal analog, DDX3Y, which is normally only expressed in the testis [51]. Cell migration and dissemination disruptions are partially caused by the inactivation of P2RY8 and GNA13 [52] while elevated levels of proliferation result from both CCND3 activation and CDKN2A inactivation [46]. Another way in which cancer-causing changes occur is through the constant stimulation of BCR signaling caused by somatic mutations affecting TCF3 and its negative regulator ID3.

As a result, BCR signaling triggers the activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, which emphasizes the importance of modifying PTEN and FOXO1 to ensure the survival of BL [46,53]. However, it is worth noting that whereas BL frequently experiences changes in several chromatin regulators, mutations in EZH2, CREBBP and KMT2D are rarely reported, unlike in germinal center B-cell-like (GCB)-DLBCL [54]. In addition, research investigating novel ways for subdividing BL with clinical implications indicates that the status of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) could be a promising approach in the future [54,55]. EBV-positive BL has markedly elevated levels of abnormal somatic hypermutation (SHM), a reduced number of driver mutations, especially in the apoptotic pathway, and fewer mutations in TCF3 and ID3 [54] (as shown in Table 1).

As mentioned, the revised WHO classification advises distinguishing EBV-positive and EBV-negative BL as separate subtypes [2]. Recent evidence (2024) has illuminated distinct biological features of EBV-positive versus EBV-negative Burkitt lymphoma (BL). A systematic review highlighted that EBV-positive BL displays elevated activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) activity, fewer canonical driver mutations (such as TCF3/ID3) and an immune-modulated microenvironment consistent with viral oncogenesis. These findings support the notion of EBV-positive BL as a biologically distinct entity [56]. When it comes to differential diagnosis, more commonly BL can be identified based on morphology and immunophenotype. In selected cases, the recognition of a specific MYC translocation (with an immunoglobulin partnering the absence of the chromosomal 11q-gain/loss pattern seen in another aggressive NHL lymphoma is also worthy. Similarly, it might be advisable to investigate the distinct patterns of mutations in TCF3 and ID3, which are frequently mutated in BL, as well as EZH2, CREBBP and KMT2D, which are mutated in other types of lymphomas.

Finally, the mutational status of TP53 has the potential to offer predictive information [57].

6. The Immune Ecosystem of Aggressive B-Cell Lymphomas

A comprehensive understanding of B-NHL pathogenesis necessitates a deep integration of immune biology. In fact, these are neoplasms of B-lymphocytes, cells whose development, differentiation and survival are inextricably linked to the physiological machinery of the immune system. Second, the malignant B-cell clones do not exist in isolation; they are embedded within a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) composed of “bystander” non-neoplastic immune cells (such as T-cells, macrophages and NK cells) and stromal elements [58]. This TME exerts profound bidirectional influences, representing both the host’s attempt at anti-tumor surveillance and a tumor-supportive niche that the lymphoma cells co-opt for survival and immune evasion [59]. Third, and of increasing clinical importance, is the therapeutic landscape. While the introduction of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab represented the first transformative immunotherapeutic advance since the CHOP regimen, the most dramatic recent improvements have stemmed from a new wave of immunotherapies, such as T-cell redirecting therapies, that directly target the tumor–immune interface [60,61]

6.1. Aberrant B-Cell Receptor Signaling and the Breach of Immune Tolerance

The immunobiology of the malignant cell itself is often pathognomonic. Many B-cell lymphomas, particularly those originating from mature B-cells, exhibit an “addiction” to signals from the B-cell receptor (BCR), a pathway essential for the survival of their normal counterparts [62]. However, the nature of this signaling dependency differs profoundly between histotypes. A key dichotomy exists between tonic, antigen-independent signaling and chronic active, antigen-driven signaling. Tonic BCR signaling is a low-level, constitutive, antigen-independent signal required for the basal survival of the B-cell. This mechanism is the hallmark of Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) [46,49,63]. While BL pathogenesis is defined by the translocation of MYC, MYC activation alone is insufficient for sustained tumorigenesis [42]. BL cells require this tonic BCR signal, which characteristically proceeds through the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway [42,64,65,66]. This pathway is notably independent of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) and the canonical NF-κB cascade [42,64,65,66]. This mechanistic distinction is not merely academic; it explains the genetic landscape of BL and its therapeutic vulnerabilities. The tonic PI3K signal provides the selective pressure for the recurrent mutations in TCF3 (E2A) and its negative regulator ID3, which are pathognomonic for BL and function to sustain this specific pathway. It also explains why BL is clinically resistant to BTK inhibitors like ibrutinib, as it bypasses the BTK-dependent NF-κB axis [42,64,65,66].

Chronic active BCR signaling, by contrast, is a robust, high-level signal that mimics a state of continuous antigen stimulation, driving proliferation. This mechanism is the signature of the ABC subtype of DLBCL [62]. Unlike the tonic signal in BL, this chronic active signal engages the full downstream cascade, including SYK, BTK and the CBM (CARD11-BCL10-MALT1) signalosome [67]. The critical terminus of this pathway is the constitutive activation of the NF-κB transcription factor, the central survival pathway for ABC-DLBCL [10,65]. This “pathway addiction” explains the sensitivity of ABC-DLBCL to BTK inhibitors, which directly shut down this oncogenic driver.

6.2. The “Broken Tolerance” Mechanism

The existence of a “chronic active” signal implies that the lymphoma B-cell is recognizing an antigen, and in many cases, a self-antigen. In a healthy immune system, such autoreactive B-cells are eliminated or functionally inactivated (anergized) through tolerance checkpoints [68]. The persistence of these autoreactive lymphoma cells is, therefore, evidence of a “broken tolerance” state. This breach of tolerance is not a passive event; it is an active, oncogenic process driven by specific genetic mutations that the lymphoma cell acquires. To date, two primary mechanisms for this breach have been elucidated. First, the so-called “Two-Signal” breach (genetic cooperation): normal B-cell activation requires two signals: Signal 1 (BCR engagement) and Signal 2 (co-stimulation, often via Toll-like receptors, or TLRs). Signal 1 alone (autoreactivity) leads to anergy or deletion [68]. The lymphoma cell breaks tolerance by acquiring mutations that “hard-wire” both signals. The pathognomonic example is the MCD (MYD88/CD79B) genetic subtype of ABC-DLBCL. In this subtype, mutations in CD79B (a component of the BCR) provide a constitutively “on” Signal 1 [65]. Concurrently, the MYD88 L265P mutation provides a constitutive Signal 2, mimicking a TLR signal [65]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the MYD88 L265P mutation is a potent mechanism for allowing an autoreactive B-cell to “break anergy” and proliferate, providing the second “hit” needed for lymphomagenesis [65]. The cooperation between these two mutations results in the potent, sustained NF-κB activation that defines this aggressive subtype [65].

In addition, more recent, a second, antigen-independent mechanism that phenocopies antigen-driven signaling has been identified. In a subset of non-GCB DLBCLs (often IgM-isotype), somatic mutations are acquired “within the BCR’s heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 (HCDR3) itself” [69]. These mutations cause the BCR to become “autonomously” active, capable of cross-linking with other BCRs on the same cell surface without any antigen present. This self-association triggers the full “chronic active” signaling cascade, representing a novel immunological oncogenic driver that intrinsically bypasses all peripheral tolerance checkpoints [69].

Of interest, transcriptomic analyses (like GEP microarrays or bulk RNA-sequencing) can capture a signature that is inherently a composite signature of neoplastic cells plus the entire TME. This TME-related data can be better “unmasked” through computational deconvolution. Algorithms such as CIBERSORT can be applied to bulk GEP/RNA-seq data [70]. Indeed, the molecular classification systems proposed for lymphomas already provide latent evidence of this. The LymphGen classification, for example, identifies an “ST2” subtype, which is defined by signatures resembling T-cell-rich, histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (TCRHRLBCL). TCRHRLBCL is defined not by its tumor genetics, but by its overwhelmingly T-cell-inflamed TME. Similarly, the identification of “immune evasion mechanisms” in the MCD and C4 genetic subtypes is further evidence of the GEP data capturing the TME’s functional state.

6.3. Immune Profiling and Predictive Clinical Information

The TME-derived information, derived from standard molecular diagnostics, is not merely descriptive; it contains powerful, independent “predictive information”. While this information is not yet “codified” into routine clinical guidelines, its clinical utility is the focus of intense investigation. A foundational study identified four major lymphoma microenvironment (LME) categories that were strongly associated with distinct biological programs and, critically, distinct clinical behaviors and outcomes [71]. Subsequently, “single-nucleus multiome” sequencing was adopted to dissect the complex lymphoma microenvironments at single-cell resolution [72]. Together, these and further studies provided evidence that prognostic information can be TME-related and independent of, and complementary to, tumor-cell-intrinsic classifications.

It is noteworthy that, alongside biological and predictive information, TME has become more and more relevant for therapeutic purposes. Particularly, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), as well as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy [61] and T-cell-engaging bispecific antibodies (BSAs) [60], are mechanistically dependent on the immune system. Indeed, the TME is the primary source of resistance to these novel treatments, and immune profiling may become a new standard in lymphoma diagnostics in the future [60] (Table 2).

Table 2.

The immunobiological landscape of aggressive B-cell lymphomas.

7. Liquid Biopsy and Minimal Residual Disease

The term minimal residual disease (MRD) is used to describe a low-level disease which is not detectable by conventional cytomorphology [76]. Detection of MRD can be clinically relevant, as it may anticipate impending relapse or treatment failure. In many lymphomas, lower MRD levels correlate with reduced tumor burden. Evidence from a National Cancer Institute cohort showed that patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL who achieved undetectable MRD after two treatment cycles had a substantially higher probability of remaining progression-free at 5 years compared with those who still had measurable MRD [35]. By contrast, MRD is studied in BL only when presenting in its leukemic form.

7.1. Methods of Detecting Minimal Residual Disease

Two main laboratory approaches are used to assess MRD in blood or bone marrow: (1) detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) by flow cytometry, and (2) analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) using PCR-based methods or next-generation sequencing (NGS).

In DLBCL, ctDNA has emerged as the most informative analyte for monitoring molecular response, owing to its sensitivity and ability to capture tumor heterogeneity more effectively than CTC-based measures [77].

7.2. Circulation Tumor DNA

Circulating tumor DNA consists of small fragments of cell-free DNA released into the bloodstream by malignant lymphoid cells. Their presence reflects tumor turnover, including apoptosis and, in some cases, necrosis. Physiological cfDNA from healthy tissues is also present, but ctDNA specifically originates from tumor cells [78].

At diagnosis and during therapy, ctDNA dynamics provide important prognostic information in DLBCL. Quantification of ctDNA can support non-invasive molecular characterization, including identification of tumor-specific mutations and subtyping. Baseline ctDNA concentrations correlate not only with traditional clinical indices—such as LDH, Ann Arbor stage, IPI and metabolic tumor volume (MTV)—but also with survival outcomes [79].

7.3. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) and Digital PCR (dPCR)

Real-time quantitative PCR is a well-established approach for MRD evaluation in several B-cell malignancies, such as mantle cell lymphoma. However, in DLBCL this method has important limitations, because many tumors do not carry stable or disease-defining chromosomal rearrangements that can be consistently monitored [80]. RQ-PCR targeting immunoglobulin gene rearrangements has been explored in DLBCL, but designing patient-specific allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) primers requires individualized optimization and considerable laboratory effort. Furthermore, ongoing somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin loci reduces assay reliability, restricting the broader application of this method.

7.4. Massive Parallel Sequencing

High-throughput sequencing techniques have been effectively used in recent years for the analysis of liquid biopsy, particularly in the examination of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). NGS methods are potentially the most sensitive with a detection rate of 10−6 and panel-directed NGS appears to be the most sensitive platform [81]. Several targeted sequencing approaches aimed at different genomic regions have been developed and applied in DLBCL. Immunoglobulin gene rearrangements can be analyzed using the ClonoSEQ assay from Adaptive Biotechnologies (commonly referred to as IgNGS), whereas somatic mutation profiling is performed through highly sensitive, panel-based next-generation sequencing methods such as cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing CAPP-Seq [82].

Using IgNGS, tumor-specific immunoglobulin rearrangements can be detected in baseline biopsy samples, enabling MRD monitoring in approximately 70–80% of patients with DLBCL [83]. Panel-directed NGS assays demonstrate superior sensitivity for identifying plasma-derived somatic variants, detecting tumor-associated alterations in about 67–87% of diagnostic samples [81].

Of note, while tissue biopsy is considered the gold standard for mutational profiling, cfDNA genotyping would serve as a valuable addition to it. Additionally, this method could be highly effective in some scenarios, such as when addressing tumors that are difficult to reach or when working with little tissue samples. It is also useful in cases where a repeat biopsy is necessary after a recurrence, transformation or other clinical occurrences. The concordance between ctDNA and FFPE in aggressive lymphomas is approximately 80%, while it is slightly lower in indolent lymphomas with a low tumor load [84]. Nevertheless, even in these instances, ctDNA research has demonstrated its validity.

Basal or pre-treatment cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis is highly advantageous for tumor genotyping and serves as a reliable substitute for assessing the tumor burden. The serial analysis enables the continuous monitoring of treatment response, tracking the evolution of clones and measuring minimal residual disease (MRD) [77,83,85,86,87]. Due to this rationale, ctDNA genotyping is likely to enhance tissue analysis soon.

Furthermore, the examination of “in-phase” variations, conducted by two separate study teams that employed slightly different methodologies [88,89], has enhanced the sensitivity of ctDNA detection. This method is beneficial in lymphomas that have an abundance of areas with abnormal somatic hypermutation (SHM), which can result in a more effective identification of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and therefore a higher capacity to detect minimal residual disease (MRD) [33,84,88,89].

Nevertheless, it is vital to make ongoing efforts to establish uniformity in each stage of applying liquid biopsy in the clinical setting, encompassing sample manipulation and bioinformatic analysis [42,87,90,91]. The technological and analytical concerns mentioned pose significant obstacles and are currently the focus of various collaborative projects aimed at enabling their eventual implementation in regular clinical practice.

Over the past decade, several prospective studies have demonstrated that early ctDNA kinetics provide stronger prognostic information than traditional clinical indices in DLBCL. In a landmark multicenter study of 217 patients, a ≥2-log decrease in ctDNA after one cycle (“early molecular response”, EMR) and a ≥2.5-log decrease after two cycles (“major molecular response”, MMR) stratified patients into groups with markedly different event-free survival, independently of IPI [82,92].

Recent advances in phased-variant enrichment and detection sequencing (PhasED-Seq) have markedly improved the analytical sensitivity of ctDNA-based MRD assays. An analytical validation study in B-cell malignancies demonstrated a limit of detection of approximately 7 × 10−7 (0.7 parts per million), enabling reliable detection of residual disease at very low tumor fractions [92,93].

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, thanks to terrific advances in molecular techniques, we have not only learned more about lymphomagenesis but also expanded the range of applications used in daily clinical practice. In fact, several new techniques have a significant impact on the clinical approach of lymphoma patients. The main applications of molecular pathology in lymphomas now include diagnosis, risk stratification, identification of therapeutic targets, treatment resistance and determination of MRD measurements. However, despite significant progress made in recent years, many methods still require validation in terms of diagnostic accuracy, and/or are limited to experimental use. It is conceivable that soon such issues will be implemented and a broader application of high-throughput methods such as next generation sequencing will be possible, also due to reduced costs and improved standardization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.P.; writing, original draft preparation, P.P.P. and V.T.; writing, review and editing, P.P.P., L.K., P.C. and B.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work reported in this publication was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, RC2025-2797263.This work was also supported by PRIN 2022NXK38S (VT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Pier Paolo Piccaluga is currently affiliated to the University of Nairobi (Nairobi, Kenya) and the University of Botswana (Gaborone, Botswana).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaggio, R.; Amador, C.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Attygalle, A.D.; Araujo IBde, O.; Berti, E.; Chuang, S.-S.; Berti, E.; Calaminici, M.; Chadburn, A.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, G.; Staudt, L.M. Aggressive Lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.C.; Banks, P.M.; Cleary, M.L.; Delsol, G.; De Wolf-Peeters, C.; Falini, B.; Delsol, G.; De Wolf- Peeters, C.; Falini, B.; Gatter, K.C. A Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms Proposed by the International Lymphoma Study Group: A Summary Version. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1995, 103, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyatskin, I.L.; Artemyeva, A.S.; Krivolapov, Y.A. Revised WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 2017 (4th edition): Lymphoid tumors. Arkhiv Patol. 2019, 81, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blombery, P.A.; Wall, M.; Seymour, J.F. The molecular pathogenesis of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 95, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katia Basso, R.D.F. Germinal centres and B cell lymphomagenesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, T.R.; Slonim, D.K.; Tamayo, P.; Huard, C.; Gaasenbeek, M.; Mesirov, J.P. Molecular Classification of Cancer: Class Discovery and Class Prediction by Gene Expression Monitoring. Science 1999, 286, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.A.; Eisen, M.B.; Davis, R.E.; Ma, C.; Lossos, I.S.; Rosenwald, A.; Boldrick, J.C.; Sabet, H.; Tran, T.; Yu, X.; et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 2000, 403, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipp, M.A.; Ross, K.N.; Tamayo, P.; Weng, A.P.; Kutok, J.L.; Aguiar, R.C.T. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwald, A.; Wright, G.; Chan, W.C.; Connors, J.M.; Campo, E.; Fisher, R.I.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Muller-Hermelink, H.K.; Smeland, E.B.; Giltnane, J.M.; et al. The Use of Molecular Profiling to Predict Survival after Chemotherapy for Diffuse Large-B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, G.; Wright, G.; Dave, S.S.; Xiao, W.; Powell, J.; Zhao, H. Stromal Gene Signatures in Large-B-Cell Lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2313–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Wang, S.; Major, C.; Hodkinson, B.; Schaffer, M.; Sehn, L.H. Comparison of immunohistochemistry and gene expression profiling subtyping for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the phase III clinical trial of R-CHOP ± ibrutinib. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 194, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W.; Wright, G.W.; Williams, P.M.; Lih, C.J.; Walsh, W.; Jaffe, E.S. Determining cell-of-origin subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using gene expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Blood 2014, 123, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzankov, A.; Xu-Monette, Z.Y.; Gerhard, M.; Visco, C.; Dirnhofer, S.; Gisin, N. Rearrangements of MYC gene facilitate risk stratification in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-CHOP. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.E.; Dojcinov, S.; Dotlic, S.; Hartmann, S.; Hsi, E.D.; Klimkowska, M. Correction to: Mediastinal large B cell lymphoma and surrounding gray areas: A report of the lymphoma workshop of the 20th meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology. Virchows Arch. 2023, 484, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ta, R.; Yang, D.; Hirt, C.; Drago, T.; Flavin, R. Molecular Diagnostic Review of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Its Tumor Microenvironment. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, R.; Santini, C.; Gou, P.; Lee, G.; Tai, Y.C.; O’Brien, C.; Fontecha, M.; Grant, C.; Bacon, L.; Finn, S.; et al. Molecular Subtyping of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Using a Novel Quantitative RT-PCR Assay. J. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 23, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.; Zhang, J.; Davis, N.S.; Moffitt, A.B.; Love, C.L.; Waldrop, A. Genetic and Functional Drivers of Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Cell 2017, 171, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Q.; Jeelall, Y.S.; Humburg, P.; Batchelor, E.L.; Kaya, S.M.; Yoo, H.M. Synergistic cooperation and crosstalk between MYD88L265P and mutations that dysregulate CD79B and surface IgM. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 2759–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuy, B.; Stewart, C.; Dunford, A.J.; Kim, J.; Kamburov, A.; Redd, R.A. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.; Wright, G.W.; Huang, D.W.; Johnson, C.A.; Phelan, J.D.; Wang, J.Q. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodicka, P.; Klener, P.; Trneny, M. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL): Early Patient Management and Emerging Treatment Options. OncoTargets Ther. 2022, 15, 1481–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondello, P.; Ansell, S.M.; Nowakowski, G.S. Immune Epigenetic Crosstalk Between Malignant B Cells and the Tumor Microenvironment in B Cell Lymphoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 826594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.W.; Huang, D.W.; Phelan, J.D.; Coulibaly, Z.A.; Roulland, S.; Young, R.M. A Probabilistic Classification Tool for Genetic Subtypes of Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma with Therapeutic Implications. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, H.; Vesely, M.D.; Koboldt, D.C.; Rickert, C.G.; Uppaluri, R.; Magrini, V.J. Cancer exome analysis reveals a T-cell-dependent mechanism of cancer immunoediting. Nature 2012, 482, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewski, A.J.; Kurt, H.; Evens, A.M. Defining and treating high-grade B.-cell lymphoma, NOS. Blood 2022, 140, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, C.; Barrans, S.; Cucco, F.; Bentley, M.A.; Care, M.A.; Cummin, T. Molecular High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma: Defining a Poor-Risk Group That Requires Different Approaches to Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennishi, D.; Jiang, A.; Boyle, M.; Collinge, B.; Grande, B.M.; Ben-Neriah, S. Double-Hit Gene Expression Signature Defines a Distinct Subgroup of Germinal Center B-Cell-Like Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennishi, D.; Hsi, E.D.; Steidl, C.; Scott, D.W. Toward a New Molecular Taxonomy of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, W.; Bouska, A.; Herek, T.A.; Amador, C.; Song, J.; Xu, A.M. High-grade B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma gene expression signatures: Genomic analysis and potential therapeutics. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rincón, J.; Méndez, M.; Gómez, S.; García, J.F.; Martín, P.; Bellas, C. Unraveling transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, G.S.; Chiappella, A.; Witzig, T.E.; Spina, M.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Zhang, L. ROBUST: Lenalidomide-R-Chop Versus Placebo-R-Chop in Previously Untreated Abc-Type Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschewski, M.; Dunleavy, K.; Pittaluga, S.; Moorhead, M.; Pepin, F.; Kong, K. Circulating tumour DNA and CT monitoring in patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A correlative biomarker study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.H.; Wright, G.W.; Huang, D.W.; Hodkinson, B.; Balasubramanian, S.; Fan, Y. Effect of ibrutinib with R-CHOP chemotherapy in genetic subtypes of DLBCL. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landsburg, D.J.; Hughes, M.E.; Koike, A.; Bond, D.; Maddocks, K.J.; Guo, L. Outcomes of patients with relapsed/refractory double-expressor B-cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib monotherapy. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, G.S.; Chiappella, A.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Scott, D.W.; Zhang, Q.; Jurczak, W. ROBUST: A Phase III Study of Lenalidomide Plus R-CHOP Versus Placebo Plus R-CHOP in Previously Untreated Patients With ABC-Type Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.; Cummin, T.E.; Barrans, S.; Maishman, T.; Mamot, C.; Novak, U. Gene-expression profiling of bortezomib added to standard chemoimmunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (REMoDL-B): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, J.; Davis, R.E.; Feng, L.; Hagemeister, F.; Steiner, R.; Lee, H.J. Smart Start: Rituximab, Lenalidomide, and Ibrutinib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, M.; Gu, J.; Huang, L.; Zhou, X. A single-centre, real-world study of BTK inhibitors for the initial treatment of MYD88mut/CD79Bmut diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roschewski, M.; Staudt, L.M.; Wilson, W.H. Burkitt’s Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K.A.; Lozanski, G.; Byrd, J.C. Adult Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma. Blood 2004, 104, 3009–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.C.J.; Tadros, S.; Bouska, A.; Heavican, T.; Yang, H.; Deng, Q. Subtype-specific and co-occurring genetic alterations in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica 2021, 107, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panea, R.I.; Love, C.L.; Shingleton, J.R.; Reddy, A.; Bailey, J.A.; Moormann, A.M. The whole-genome landscape of Burkitt lymphoma subtypes. Blood 2019, 134, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.; Young, R.M.; Ceribelli, M.; Jhavar, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, M.; Wright, G.; Shaffer, A.L.; Hodson, D.L.; Buras, E.; et al. Burkitt lymphoma pathogenesis and therapeutic targets from structural and functional genomics. Nature 2012, 490, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, S.S.; Fu, K.; Wright, G.W.; Lam, L.T.; Kluin, P.; Boerma, E.J. Molecular Diagnosis of Burkitt’s Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2431–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, M.; Bentink, S.; Berger, H.; Klapper, W.; Wessendorf, S.; Barth, T.F.E. A Biologic Definition of Burkitt’s Lymphoma from Transcriptional and Genomic Profiling. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccaluga, P.P.; De Falco, G.; Kustagi, M.; Gazzola, A.; Agostinelli, C.; Tripodo, C.; Leucci, E.; Onnis, A.; Astolfi, A.; Sapienza, M.R.; et al. Gene expression analysis uncovers similarity and differences among Burkitt lymphoma subtypes. Blood 2011, 117, 3596–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Zaka, M.; Zhou, P.; Blain, A.E.; Erhorn, A.; Barnard, A. Genomic abnormalities of TP53 define distinct risk groups of paediatric B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leukemia 2022, 36, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Krupka, J.A.; Gao, J.; Grigoropoulos, N.F.; Giotopoulos, G.; Asby, R. Sequential inverse dysregulation of the RNA helicases DDX3X and DDX3Y facilitates MYC-driven lymphomagenesis. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 4059–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muppidi, J.R.; Schmitz, R.; Green, J.A.; Xiao, W.; Larsen, A.B.; Braun, S.E. Loss of signalling via Gα13 in germinal centre B-cell-derived lymphoma. Nature 2014, 516, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabrani, E.; Chu, V.T.; Tasouri, E.; Sommermann, T.; Baßler, K.; Ulas, T. Nuclear FOXO1 promotes lymphomagenesis in germinal center B cells. Blood 2018, 132, 2670–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, B.M.; Gerhard, D.S.; Jiang, A.; Griner, N.B.; Abramson, J.S.; Alexander, T.B.; Allen, H.; Ayers, L.W.; Bethony, J.M.; Bhatia, K.; et al. Genome-wide discovery of somatic coding and noncoding mutations in pediatric endemic and sporadic Burkitt lymphoma. Blood 2019, 133, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoncini, L. Epstein–Barr virus positivity as a defining pathogenetic feature of Burkitt lymphoma subtypes. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 196, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solares, S.; León, J.; García-Gutiérrez, L. The Functional Interaction Between Epstein–Barr Virus and MYC in the Pathogenesis of Burkitt Lymphoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Kleinheinz, K.; Aukema, S.M.; Rohde, M.; Bernhart, S.H.; Hübschmann, D. Genomic and transcriptomic changes complement each other in the pathogenesis of sporadic Burkitt lymphoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, M.; Leivonen, S.-K.; Brück, O.; Mustjoki, S.; Jørgensen, J.M.; Karjalainen-Lindsberg, M.-L. Immune cell constitution in the tumor microenvironment predicts the outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2020, 106, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opinto, G.; Vegliante, M.C.; Negri, A.; Skrypets, T.; Loseto, G.; Pileri, S.A. The Tumor Microenvironment of DLBCL in the Computational Era. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, J.; Westin, J. The future of immunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah-Yunes, S.A.; Robertson, M.J.; Davé, U.P.; Ghione, P.; Perna, F. Novel Immune-Based treatments for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The Post-CAR T Cell Era. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 901365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemann, C.U.; Wiestner, A. B-cell receptor signaling as a driver of lymphoma development and evolution. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013, 23, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, F.; Ambrosio, M.R.; Mundo, L.; Laginestra, M.A.; Fuligni, F.; Rossi, M. Distinct Viral and Mutational Spectrum of Endemic Burkitt Lymphoma. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.H.; Young, R.M.; Schmitz, R.; Yang, Y.; Pittaluga, S.; Wright, G. Targeting B cell receptor signaling with ibrutinib in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 922–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M.; Shaffer, A.L.; Phelan, J.D.; Staudt, L.M. B-Cell Receptor Signaling in Diffuse Large B-Cell lymphoma. Semin. Hematol. 2015, 52, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M.; Staudt, L.M. Targeting pathological B cell receptor signalling in lymphoid malignancies. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2013, 12, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argentiero, A.; Andriano, A.; Marziliano, D.; Desantis, V. Navigating Lymphomas through BCR Signaling and Double-Hit Insights: Overview. Hematol. Rep. 2024, 16, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Kwak, K. Both sides now: Evolutionary traits of antigens and B cells in tolerance and activation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1456220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eken, J.A.; Koning, M.T.; Kupcova, K.; Yáñez, J.H.S.; de Groen, R.A.L.; Quinten, E. Antigen-independent, autonomous B cell receptor signaling drives activated B cell DLBCL. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20230941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etebari, M.; Navari, M.; Agostinelli, C.; Visani, A.; Peron, C.; Iqbal, J. Transcriptional Analysis of Lennert Lymphoma Reveals a Unique Profile and Identifies Novel Therapeutic Targets. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlov, N.; Bagaev, A.; Revuelta, M.V.; Phillip, J.M.; Cacciapuoti, M.T.; Antysheva, Z. Clinical and Biological Subtypes of B-cell Lymphoma Revealed by Microenvironmental Signatures. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1468–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Singhal, K.; Deng, Q.; Chihara, D.; Russler-Germain, D.; Harkins, R.A. Large B cell lymphoma microenvironment archetype profiles. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengol, M.; Santos, J.C.; Fernández-Serrano, M.; Profitós-Pelejà, N.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Roué, G. Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors in B-Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Luo, K.; He, X.; Hu, X.; Zhai, Y.; Jiang, Y. Programmed-Cell-Death-Related Signature Reveals Immune Microenvironment Characteristics and Predicts Therapeutic Response in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Abramson, J.S. Current Treatment of Burkitt Lymphoma and High-Grade B-Cell Lymphomas. Oncology 2022, 36, 499. [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann, M.; Kotrova, M. Minimal residual disease in adult ALL: Technical aspects and implications for correct clinical interpretation. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 2456–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, F.; Kurtz, D.M.; Newman, A.M.; Stehr, H.; Craig, A.F.M.; Esfahani, M.S. Distinct biological subtypes and patterns of genome evolution in lymphoma revealed by circulating tumor DNA. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 364ra155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Winter, A.; Hill, B.T. The Emerging Role of Minimal Residual Disease Testing in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcoceba, M.; Stewart, J.P.; García-Álvarez, M.; Díaz, L.G.; Jiménez, C.; Medina, A. Liquid biopsy for molecular characterization of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and early assessment of minimal residual disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 205, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottcher, S.; Ritgen, M.; Buske, S.; Gesk, S.; Klapper, W.; Hoster, E. Minimal residual disease detection in mantle cell lymphoma: Methods and significance of four-color flow cytometry compared to consensus IGH-polymerase chain reaction at initial staging and for follow-up examinations. Haematologica 2008, 93, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, A.F.; Armand, P. Minimal Residual Disease Assessment in Lymphoma: Methods and Applications. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3877–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, D.M.; Green, M.R.; Bratman, S.V.; Scherer, F.; Liu, C.L.; Kunder, C.A. Noninvasive monitoring of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing. Blood 2015, 125, 3679–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, D.M.; Scherer, F.; Jin, M.C.; Soo, J.; Craig, A.F.M.; Esfahani, M.S. Circulating Tumor DNA Measurements As Early Outcome Predictors in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Miranda, I.; Pedrosa, L.; Llanos, M.; Franco, F.F.; Gómez, S.; Martín-Acosta, P. Monitoring of Circulating Tumor DNA Predicts Response to Treatment and Early Progression in Follicular Lymphoma: Results of a Prospective Pilot Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscaggin, A.; di Bergamo, L.T.; Spina, V.; Hodkinson, B.; Forestieri, G.; Bonfiglio, F. Circulating tumor DNA for comprehensive noninvasive monitoring of lymphoma treated with ibrutinib plus nivolumab. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 4674–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ubieto, A.; Poza, M.; Martin-Muñoz, A.; Ruiz-Heredia, Y.; Dorado, S.; Figaredo, G. Real-life disease monitoring in follicular lymphoma patients using liquid biopsy ultra-deep sequencing and PET/CT. Leukemia 2023, 37, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, V.; Bruscaggin, A.; Cuccaro, A.; Martini, M.; Di Trani, M.; Forestieri, G. Circulating tumor DNA reveals genetics, clonal evolution, and residual disease in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2018, 131, 2413–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, D.M.; Soo, J.; Co Ting Keh, L.; Alig, S.; Chabon, J.J.; Sworder, B.J. Enhanced detection of minimal residual disease by targeted sequencing of phased variants in circulating tumor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meriranta, L.; Alkodsi, A.; Pasanen, A.; Lepistö, M.; Mapar, P.; Blaker, Y.N. Molecular features encoded in the ctDNA reveal heterogeneity and predict outcome in high-risk aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2022, 139, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbon, E.; Alcazer, V.; Cheli, E.; Huet, S.; Sujobert, P. How to Obtain a High Quality ctDNA in Lymphoma Patients: Preanalytical Tips and Tricks. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschewski, M.; Rossi, D.; Kurtz, D.M.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Wilson, W.H. Circulating Tumor DNA in Lymphoma: Principles and Future Directions. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022, 3, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauer, E.M.; Mutter, J.; Scherer, F. Circulating tumor DNA in B-cell lymphoma: Technical advances, clinical applications, and perspectives for translational research. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2151–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimova, N.; Close, S.; Kurtz, D.M.; Hockett, R.D.; Hyland, L. Analytical validation of a circulating tumor DNA assay using PhasED-Seq technology for detecting residual disease in B-cell malignancies. Oncotarget 2025, 16, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).