Abstract

This article represents a brief overview of the recent achievements in the treatment of multiple myeloma. New opportunities and treatment challenges are discussed in the context of risk factors regarding outcomes. The options for specific targeted treatments are discussed, and references are made to recent guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma.

1. The Landscape of Multiple Myeloma

The treatment outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) have significantly improved since the introduction of novel agents such as proteasome inhibitors (PI), immunomodulatory agents (IMiDs), and, more recently, anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab and isatuximab), resulting in higher response rates, better quality of responses, higher rates of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity, longer progression-free survival (PFS), and improved overall survival (OS) when compared with conventional chemotherapy [1,2]. In spite of these gains, high-dose melphalan followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (HDM/ASCT) remains the standard in young, fit patients [3,4]. Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide in first remission is an approved standard treatment, while the optimal duration remains an issue of debate [5].

More recently, a large number of new myeloma drugs have been approved by the FDA and/or EMA, many of which are based on a novel mode of action. New generation IMiD drugs include pomalidomide, the CELMoD drugs iberdomide, and others. The Nuclear Export Inhibitor 1 selinexor, PD-1(L) inhibitors, the peptide drug conjugate melphalan flufenamide, and, most of all, the new classes of immune therapies have been approved for triple-refractory patients [6]. The most significant new therapeutic modalities are T-cell redirection approaches such as bispecific anti-BCMA antibodies, including teclistamab and elranatamab, and antibody drug conjugates such as belantamab and mafodotin, which have demonstrated significant activity in advanced RRMM and are now being introduced in earlier stages of the disease, including frontline treatment regimens [7]. Patient-specific cellular modalities, such as CAR-T-cell treatment with cilta-cel or ide-cel, have been approved for first relapse, and these will change the clinical treatment landscape of MM [8]. New modalities have made it possible to offer patients unique therapies for refractory disease or when progression occurs. This is clinically relevant, as many patients who progress after initial treatment will be triple or quadruple exposed or even refractory. As a result, numerous treatment options are now available to the treating physician, from whom choices have to be made for the individual patient. This is one of the most difficult challenges today, since most patients tolerate only a limited number of treatments, and the attrition rate among elderly patients is high. The clinical limitations of tolerability and/or efficacy dictate that after standard initial treatment, patients who progress should only be treated with the most effective and well-tolerated regimens in order to avoid dose-limiting toxicity and development of refractory disease. In addition, healthcare resource restraints or limited drug access are hurdles that define the options available in daily practice.

2. The Role of Prognostic Factors

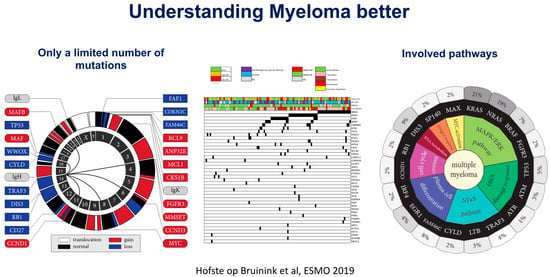

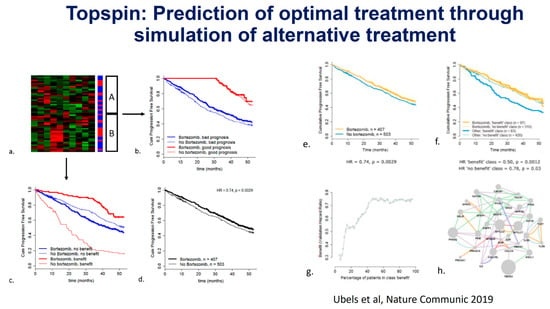

For a long period of time, patients with MM were equally treated using standard regimens. Since the introduction of HDM/ASCT, the general recommendation has been to treat younger, fit patients with induction followed by intensification, while older (>65 yrs) or unfit/frail patients receive less intensive treatment. However, the recognition that large differences in outcome may occur between patients led to attempts to identify subgroups with different risk categories for response and/or survival, such as the Durie–Salmon classification, which included MM-related organ damage. This system has been applied for patients in clinical trials, but also for routine clinical practice and individual patient risk assessments. Since the introduction of bortezomib, thalidomide, lenalidomide, and other agents, it has become possible to make clinical treatment choices based on their expected benefit to patients. Also, the assumption that so-called high-risk (HR) patients as defined by ISS and FISH would require more intensive treatment for optimal treatment results urged the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) to construct classifications initially based on serum beta-2 microglobulin and albumin (International Staging System, ISS), to which several unfavorable FISH abnormalities (t(4;14), inv(16), del17p) and serum LDH were added (R-ISS) [9,10,11]. More recently, a large data analysis performed in the EU-funded Harmony program enabled them to perform an update, in which 1q/1p abnormalities were included (R2-ISS) [12]. The ISS classifications identified groups of patients with high- or low-risk disease; however, they failed to clearly define a large group of intermediate-risk patients in more detail. Until today, patients who are classified as high-risk represent small groups (10–15%) in clinical trials, and, consequently, their outcome can often not be determined separately. In addition, these systems do not include important biological and molecular characteristics, such as mutations and chromosomal abnormalities not detected by FISH, that may be relevant for the course of the disease (Figure 1) [13]. These systems, while useful to compare between matching of subgroups in clinical trials, cannot easily be used for prognostication of individual patients nor for prediction of drug/treatment sensitivity in high-risk subgroups. Hence, new computational algorithms based on large clinical databases may offer an alternative approach for individual prognostication to a specific drug (Figure 2). Recently, the International Myeloma Society organized a consensus meeting in September 2023 to define (very) high-risk disease based on molecular and other abnormalities [14].

Figure 1.

Summary of genetic changes observed in multiple myeloma. Courtesy of D. Hofste op Bruinink & P. Sonneveld, ESMO proceedings 2019. (accessed on 27 February 2024, https://www.kimia-pharma.co/UserFile/Download/2019-ESMO-Essentials-for-Clinicians-Leukaemia-and-Myeloma-PDF.pdf).

Figure 2.

(a–h) Prediction of bortezomib sensitivity using an AI approach to integrate data from a large prospective Phase 3 trial. J. Ubels, P. Sonneveld et al. Nature Communications 2019 [15].

3. Prediction of Treatment Response

In oncology, physicians generally try to develop a specific test for targeted drug sensitivity that separates responding patients from refractory patients. Examples are the presence of bcr/abl fusion protein in chronic myelocytic leukemia, which is 100% specific, or hormone receptor presence in breast cancer. In these diseases, a positive test will influence the choice of treatment regimen. In MM, such an approach has not been possible due to the lack of specific identified targets or minor differences between risk groups of patients. Proteasome subunits are known targets of bortezomib and carfilzomib; however, these have not been shown to differentiate between refractory and responding patients. Similarly, cereblon and its downstream ubiquitin cascade, while being lenalidomide targets, are not differentiated enough to be used for pre-treatment selection. B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) is an epitope expressed on MM cells, which was identified as a specific target for CAR-T-cells and bispecific antibodies. While initial trials with cilta-cel and ide-cel in late-stage disease have been very successful, ultimately, all patients progress. Consequently, it remains to be determined if variables such as BCMA expression levels, soluble serum BCMA, and viability of the T-cell microenvironment are determinants of the ultimate disease response in individual patients. Treatment schedules that include CAR-T-cells of bispecific antibodies to target BCMA and/or other myeloma-specific antigens may offer a new option to improve outcomes with front-line treatment

4. New Approaches to Precision Treatment

Upfront classification of disease-related risk has, as of yet, not been possible, due to incomplete data on molecular assessment of relevant genes and pathways in prospective clinical trials or patient populations. Genomic analysis of myeloma plasma cells has revealed many altered pathways of proliferation and cell survival, as well as remarkable patterns of early and late mutations; however, this has not been to a level to where these findings fully explain the differences in treatment outcome, possibly with the exception of patients with a high mutational load or inactivation of the TP53 gene [16]. Gene expression profiling and deep sequencing of myeloma samples from cell lines and patients have demonstrated that a wide variety of mutations and pathway activations may occur at an increasing rate in advanced disease (Figure 1). Recent insights obtained by single-cell RNA sequencing have revealed that myeloma cells interact with the microenvironment, such as the neutrophil compartment, mesenchymal cells, and immune cells, through signaling and inflammation [17]. Moreover, it is now recognized that an intact immune response is required to kill myeloma cells. The recent development of bispecific antibodies directed at BCMA or GPRC5D has demonstrated that specific targeting combined with the mobilization of T-cells effectively kills myeloma. Similarly, anti-BCMA CAR-T-cell strategies employ redirected T-cell function to specifically target myeloma [18]. These approaches have already demonstrated impressive responses and durations of response in advanced disease and will be investigated in early disease states as well. Other potential molecules for specific T-cell targeting include APOBEC, April/BAFF, and signaling pathways. The benefits of precision medicine in myeloma using such targeted agents ideally include pre-treatment target identification, more rapid and higher rates of tumor cell kill, less nonspecific organ toxicity, and avoidance of treatment-induced drug resistance, while maintaining or improving treatment response and survival.

In the current era, we are moving from a paradigm of non-specific, cytotoxic drug therapy to immune treatments that are delivered specifically to the target cell. None of this has been specifically designed for or applied to high-risk patients. However, for the first time, there is hope that patients with an otherwise dismal prognosis may benefit from rational therapeutic approaches.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Moreau, P.; Attal, M.; Hulin, C.; Arnulf, B.; Belhadj, K.; Benboubker, L.; Béné, M.C.; Broijl, A.; Caillon, H.; Caillot, D.; et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019, 394, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonneveld, P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Boccadoro, M.; Quach, H.; Ho, P.J.; Beksac, M.; Hulin, C.; Antonioli, E.; Leleu, X.; Mangiacavalli, S.; et al. Daratumumab, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, A.; Rajkumar, S.V.; San Miguel, J.F.; Larocca, A.; Niesvizky, R.; Morgan, G.; Landgren, O.; Hajek, R.; Einsele, H.; Anderson, K.C.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus statement for the management, treatment, and supportive care of patients with myeloma not eligible for standard autologous stem-cell transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrot, A. How I treat frontline transplantation-eligible multiple myeloma. Blood 2022, 139, 2882–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, G.H.; Davies, F.E.; Pawlyn, C.; Cairns, D.A.; Striha, A.; Collett, C.; Waterhouse, A.; Jones, J.R.; Kishore, B.; Garg, M.; et al. Lenalidomide before and after ASCT for transplant-eligible patients of all ages in the randomized, phase III, Myeloma XI trial. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Moreau, P.; Terpos, E.; Mateos, M.V.; Zweegman, S.; Cook, G.; Delforge, M.; Hájek, R.; Schjesvold, F.; Cavo, M.; et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosny, M.; Verkleij, C.P.M.; van der Schans, J.; Frerichs, K.A.; Mutis, T.; Zweegman, S.; van de Donk, N.W.C.J. Current State of the Art and Prospects of T Cell-Redirecting Bispecific Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Donk, N.; Pawlyn, C.; Yong, K.L. Multiple myeloma. Lancet 2021, 397, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greipp, P.R.; San Miguel, J.; Durie, B.G.; Crowley, J.J.; Barlogie, B.; Blade, J.; Boccadoro, M.; Child, J.A.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Kyle, R.A.; et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3412–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, A.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Oliva, S.; Lokhorst, H.M.; Goldschmidt, H.; Rosinol, L.; Richardson, P.; Caltagirone, S.; Lahuerta, J.J.; Facon, T.; et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report from International Myeloma Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2863–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonneveld, P.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Lonial, S.; Usmani, S.; Siegel, D.; Anderson, K.C.; Chng, W.-J.; Moreau, P.; Attal, M.; Kyle, R.A.; et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics: A consensus of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood 2016, 127, 2955–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, M.; Cairns, D.A.; Lahuerta, J.J.; Wester, R.; Bertsch, U.; Waage, A.; Zamagni, E.; Mateos, M.-V.; Dall, D.; van de Donk, N.W.C.J.; et al. Second Revision of the International Staging System (R2-ISS) for Overall Survival in Multiple Myeloma: A European Myeloma Network (EMN) Report Within the HARMONY Project. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3406–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, F.E.; Pawlyn, C.; Usmani, S.Z.; San-Miguel, J.F.; Einsele, H.; Boyle, E.M.; Corre, J.; Auclair, D.; Cho, H.J.; Lonial, S.; et al. Perspectives on the Risk-Stratified Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022, 3, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avet-Loiseau, H.; Davies, F.E.; Samur, M.K.; Corre, J.; D’Agostino, M.; Kaiser, M.F.; Raab, M.S.; Weinhold, N.; Gutierrez, N.C.; Paiva, B.; et al. International Myeloma Society/International Myeloma Working Group Consensus Recommendations on the Definition of High-Risk Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 2739–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubels, J.; Sonneveld, P.; van Beers, E.H.; Broijl, A.; van Vliet, M.H.; de Ridde, J. Predicting treatment benefit in multiple myeloma through simulation of alternative treatment effects. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.A.; Mavrommatis, K.; Wardell, C.P.; Ashby, T.C.; Bauer, M.; Davies, F.; Rosenthal, A.; Wang, H.; Qu, P.; Hoering, A.; et al. A high-risk, Double-Hit, group of newly diagnosed myeloma identified by genomic analysis. Leukemia 2019, 33, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, M.M.E.; Kellermayer, Z.; Papazian, N.; Tahri, S.; Hofste Op Bruinink, D.; Hoogenboezem, R.; Sanders, M.A.; van de Woestijne, P.C.; Bos, P.K.; Khandanpour, C.; et al. The multiple myeloma microenvironment is defined by an inflammatory stromal cell landscape. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Donk, N.; Themeli, M.; Usmani, S.Z. Determinants of response and mechanisms of resistance of CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021, 2, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).