Abstract

Background/Objectives: Acne is a common skin condition that is characterized by the manifestation of comedones, erythematous papules, pustules, and nodules over follicular areas. A huge contributing factor in the pathogenesis is colonization by Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) (formerly Propionibacterium acnes). Conventional treatments for acne range from topical to systemic agents with variable side effects and safety profiles. Adherence to prescribed treatments for acne is a huge challenge. Method: A quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted among 198 patients with dermatologist-confirmed acne vulgaris at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah. Eligible participants had received topical and/or systemic treatment for at least one month. Exclusion criteria included other acne variants and inflammatory follicular disorders. Data on sociodemographics, medical and treatment history, and clinical characteristics were collected using a structured questionnaire. Treatment adherence was assessed with the validated ECOB scale. Associations between adherence and relevant variables were analyzed using Chi-squared and Mann–Whitney tests in SPSS v26, with significance set at p ≤ 0.05. Results: Non-adherence to anti-acne medications was 50.5% and was significantly associated with experiencing side effects, particularly skin dryness, and with moderate acne severity and topical treatment (p ≤ 0.05). No significant associations were found between adherence and demographic or medical history variables. Conclusions: Adherence to acne treatment remains a significant challenge for many patients. Improving patient education, addressing concerns about side effects, and providing practical support may help patients follow their prescribed therapies more consistently. Incorporating tools like the ECOB questionnaire into routine dermatology visits can support ongoing assessment and better management of treatment adherence.

1. Introduction

Acne (Acne vulgaris) is an extremely common condition that affects many individuals. It is the most frequent inflammatory dermatosis worldwide. It is the eighth common disease globally, and 9.4% of the population is affected [1]. It classically manifests as comedones, erythematous papules, pustules, and nodules over follicular areas, like the face, neckline, and back. Adolescents and adults of both genders are susceptible [1].

There is a wide range of modalities to manage acne, from topical creams, oral medication, to laser [2]. For mild acne, comedonal acne can be treated by topical retinoids, azelaic acid, or salicylic acid, among others. Manual comedonal extraction could be an option. Inflammatory acne is treated by topical antimicrobial, topical retinoids and azelaic acid. Moderate acne is managed by oral antibiotics, topical retinoids, and Benzoyl peroxide (BPO). Oral isotretinoin could be considered if the lesion is nodular, scarring, or recalcitrant. Females could be counseled on oral contraceptive pills and antiandrogenic treatments like Spironolactone for their acne ailment. Conglobata or fulminans are severe forms of acne and are managed by oral isotretinoin, oral dapsone, high-dose antibiotics, BPO, or topical retinoids. Acne fulminans can be treated by oral corticosteroids [3]. Maintenance therapy of acne is crucial; thus, topical retinoids and BPO are often prescribed to prevent the recurrence and maintain the results achieved during the treatment [3].

Adherence to prescribed treatment for acne, either topical or systemic, should be emphasized to patients. Salamzadeh et al. [4] performed a study and reported that acne patients had a very low adherence rate (30%). To evaluate patient adherence, this study used a validated questionnaire (ECOB, Elaboration d’un outil d’evaluation de l’observance des traitements médicamenteux), we selected the ECOB adherence questionnaire because it is a brief, dermatology-specific, and validated tool for assessing adherence to both topical and oral acne treatments. It has been widely used in large acne cohorts and multicenter trials, allowing for comparability across studies. Its 4-item structure enables rapid administration in a clinical research setting without burdening participants, while its binary scoring system provides clear and reproducible classification of adherence status. Compared with generic tools such as MMAS or MARS, ECOB directly captures adherence behaviors relevant to acne therapy and is more appropriate for studies involving topical agents. The studied factors that could affect adherence rate are socio-economic factors, medical history, and medication list. Adherence is a critical cornerstone that affects the patient–physician relationship. Emphasizing adherence and assessing for factors that may decrease it is pivotal to the resolution of the ailment. This cross-sectional study intends to evaluate the adherence to medication among patients with acne vulgaris who received care at a tertiary facility in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

To our knowledge, there is limited research on medication adherence among acne vulgaris patients in Saudi Arabia, and no previous studies have specifically evaluated this issue in the Western region or within tertiary care settings. Our study addresses this gap by providing data on adherence patterns and associated factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

This is a quantitative cross-sectional study that was conducted on acne vulgaris patients visiting the dermatology clinic at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. A dermatologist approved the classification of acne vulgaris, and patients received treatment based on their classification, with cases being classed as mild, moderate, or severe.

Patients diagnosed with acne vulgaris who have been undergoing treatment with topical and/or systemic medications for a minimum duration of one month were included in the study, and a minimum of one month of therapy was chosen to allow sufficient exposure for initial patient experience and to enable meaningful assessment of adherence. Individuals with alternative types of acne and other inflammatory follicular disorders, including hidradenitis suppurativa or acne rosacea, were not included in the study.

2.2. Study Setting, Design, and Sample Size

A total of 198 patients with acne vulgaris who visited the dermatology clinics at King Abdulaziz University Hospital were included in the study. After verbally consenting to participate in the study, the patients were evaluated by dermatologist-directed questionnaire. A validated 4-item questionnaire known as ECOB (Elaboration d’un outil d’évaluation de l’observance des traitements médicamenteux) was employed to assess adherence to both oral and topical treatments [5]. The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and insurance status, were recorded. Additionally, the patients’ past medical and drug history regarding acne, age at disease onset, duration of treatment (oral and/or topical), distribution and severity of acne lesions (as assessed by both the patient and physician), family history of acne in first-degree relatives, medications utilized for acne, any concurrent medical conditions and associated medications, use of complementary and alternative medicines within the past three months, number of dermatologist visits, history of tobacco use, drug or food allergies, and side effects of medications were also recorded. This study evaluated the relationship between participants’ medication adherence and their sociodemographic factors, medication history, and reported side effects.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS application version 26. To assess the association between the variables, the Chi-squared test (χ2) was applied to qualitative data that was expressed as numbers and percentages. In order to assess the strength of relationships between medication adherence and participant demographic, clinical, and treatment-related characteristics, effect size measures were computed to supplement the significance testing. Effect sizes were reported using Cramér’s V (V) for tables greater than 2 × 2 and the Phi coefficient (φ) for 2 × 2 tables. The relationship between the quantitative non-parametric variables that were expressed as median and interquartile range (Median-IQR) was examined using the Mann–Whitney test, and the test statistic (r = Z/√N) was used to quantify the effect size, reported as r. Conventional thresholds (small = 0.10, moderate = 0.30, large = 0.50) were used to interpret effect size values. A multivariable logistic regression model served as a predictor of medication adherence among studied patients. The Odds Ratio was calculated at a Confidence Interval (CI) of 95%. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The ethical committee of the faculty of medicine and surgery at King Abdulaziz University Hospital approved the study (reference No 243-22). The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients received explanations during their clinic visits to obtain data, and their verbal consent was taken for inclusion in the research. Furthermore, patients were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that all patient information would remain confidential.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

The median age of the participants was 27 years, and their median BMI was 25.1 kg/m2. Of them, 90.4% (179/198) were females, 11.1% (22/198) were smokers, and 58.1% (115/198) had an insurance. Only 19.7% (39/198) had a current medical condition, of them 94.9% (37/198) were on medications. More than half (54% (107/198)) had a history of acne in a first-degree relative, and 26.8% had a food allergy (shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of participants according to their demographic data, insurance status, smoking status, medical conditions, and data on family history of acne and drug allergies (No.: 198).

The median age of acne onset was 17 years. Overall, 40.9% (81/198) had moderate acne, and 65.5% (129/198) were on topical treatment only (shown in Table 2). The most commonly used medication was topical retinoids (45.5% (90/198)), and 46.5% (92/198) were taking the anti-acne medication once a day. Most of them, (54% (107/198)) had an acne duration of more than 6 months, and 33.8% (67/198) had a treatment duration for more than 5 months. Most of them (61.6% (122/198)) had single-site acne.

Table 2.

Distribution of the participants according to clinical data of acne vulgaris (No.: 198).

3.2. Treatment Adherence

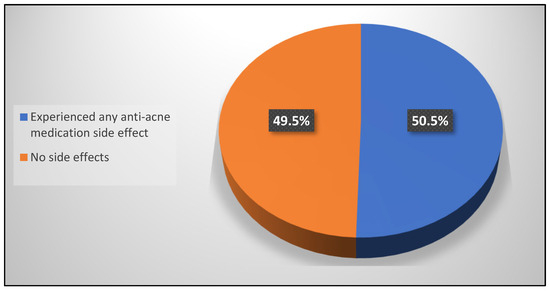

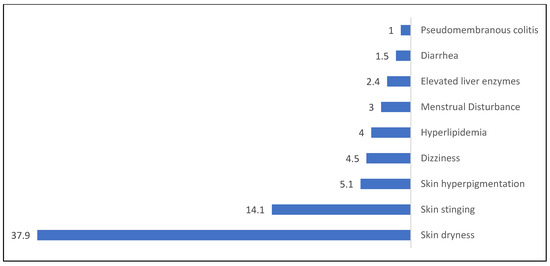

Almost half of the participants, 50.5% (100/198), suffered from anti-acne medication side effects (shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2). The most common side effects were skin dryness (37.9%) and skin staining (14.1%). Among the patients on topical or combined treatment, 52% (103/198) remember the name of the last drug taken, 67.2% (133/198) tolerated these drugs well, and 66.2% (131/198) found these drugs useful for them (shown in Table 3). For 32.8% (65/198), they stopped taking these drugs because they thought they would do more harm than good. Among participants that were on oral or combined treatment, only 29.8% (59/198) remember the name of the last drug taken, 33.8% (67/198) used these drugs, and 22.7% (45/198) forgotten to take these drugs at any time during the treatment period. For 32.3% (64/198), these drugs improved their acne.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of the participants according to prevalence of anti-acne medication side effects (No.: 198).

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of the participants according to prevalence of types of anti-acne medication side effect (No.: 100).

Table 3.

Distribution of the participants according to pattern, effect and adherence to the used treatment (No.: 198).

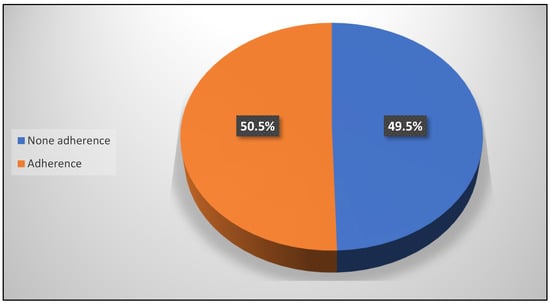

The prevalence of non-adherence to any of the used medications was 50.5% (shown in Figure 3). Non-adherence was significantly more frequent among smokers (p ≤ 0.05), while a non-significant relationship was found between medication adherence and participants’ demographic data, insurance status, medical conditions, family history of acne, or drug allergy (p ≥ 0.05). The majority of demographic factors had poor to nonexistent relationships with medication adherence, according to effect size values. The effects of age (r = 0.063) and BMI (r = 0.032) were negligible. Negligible-to-small relationships were also shown by gender (φ = 0.089), insurance status (φ = 0.019), current medical conditions (φ = 0.084), medication use for existing conditions (φ = 0.086), family history of acne (φ = 0.000), and allergy history (φ = 0.040). Although still in the small range (φ = 0.164), smoking status had the biggest influence, as shown in Table 4, suggesting a weak but discernible link between smoking and lower adherence. The effect size analysis for (Table 4) indicates that participants’ medication adherence is not significantly impacted by demographic characteristics.

Figure 3.

Percentage distribution of the participants according to prevalence of adherence to the used anti-acne medications (No.: 198).

Table 4.

Relationship between medication adherence and participants’ demographic data, insurance status, smoking status, medical conditions, and data on family history of acne, and drug allergies (No.: 198).

Table 5 shows that non-adherence to medications used was significantly higher among participants who were on topical treatment only, as well as those who experienced skin dryness, hyperlipidemia, or skin stinging as side effects of medication used (p ≤ 0.05). At the same time, non-adherence to medications used was significantly higher among patients who experienced any anti-acne medication side effect, patients who used topical or combined treatment and saw that these drugs were useful for them, and patients who used oral or combined treatment and saw that these drugs improved their acne (p ≤ 0.05). On the other hand, acne adherence was significantly higher among those who had a single-site lesion and those who had mild acne (p ≤ 0.05). Compared with demographic factors, clinical characteristics and treatment-related variables showed stronger associations with adherence. Age at acne onset had a negligible effect (r = 0.134). Treatment type showed a small-to-moderate association (V = 0.232), indicating differing adherence between patients receiving oral therapy versus topical or combined regimens. Medication frequency, disease duration, and treatment duration demonstrated negligible-to-small effects (V = 0.131, 0.060, and 0.039, respectively). Lesion distribution showed a small-to-moderate association (V = 0.236), with patients presenting multi-site lesions displaying different adherence patterns than those with localized involvement. Patient-reported acne severity and the other variable have a moderate correlation, according to the reported effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.298). This implies a significant but weak link.

Table 5.

Relationship between medication adherence and participants’ clinical data and pattern and effect of the used anti-acne vulgaris medications (No.: 198).

Multivariable logistic regression model was performed to assess the risk factors (independent predictors) of medication adherence among studied acne vulgaris patients. The strongest independent impacts were seen in treatment-related factors. Compared to patients receiving topical therapy alone, those receiving combination or oral medications had a much higher adherence rate. Significantly reduced probabilities of adherence were linked to any medication-related side effects, especially skin dryness, hyperlipidemia, and skin stinging. Reduced adherence was also significantly influenced by clinical features such as multi-site lesion distribution and increased patient-perceived severity. The only demographic factor that remained significant in the corrected model was smoking. A significant amount of the diversity in adherence behavior was described by the model (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.48), suggesting that adherence behaviors are significantly influenced by medication type, side effect burden, and clinical presentation (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariable logistic regression model for predictors of medication adherence (N = 198).

4. Discussion

In this study, we assessed treatment adherence, in addition to potential circumstances and variables that impact medication adherence in patients with acne vulgaris. Total adherence to acne treatment was measured to be 49.5%; specifically, adherence was observed in 83% of patients on topical treatments, 12% of patients on oral treatments, and 5% of patients on a combined regimen. Numerous studies have found that treatment adherence ranges from 7 to 98% [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Compared to other research studies, the average age of our patients was 28.47 years [5,12,13]. Females constituted 90.4% of the total number of participants, comparable to other studies [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. The discrepancy between topical and oral therapy adherence has been shown in numerous studies. Nonetheless, oral therapies (24.5%), in our study, were associated with the worst adherence compared with topical treatment (46.9%) and combined regimens (28.6%) [4,5,7,14]. In our study, there was a significant difference between oral and topical treatment adherence. The best treatment for acne patients showed acceptable adherence to topical therapies (45.5%), which is comparable to the results reported by Miyachi et al. [8] and Dreno et al. [6], as in their studies, higher adherence was observed in patients using topical treatments. On the other hand, Salamzadeh et al. [4] have reported no difference in patients’ persistence between topical and oral treatments. The variations between the studies can largely be attributed to factors such as sample size discrepancies, differing measurement methods, selection bias, and the diversity of populations and ethnic groups involved. It has been noted that Europe exhibited the lowest levels of adherence [6]. No prior research has evaluated the adherence to acne vulgaris treatments among patients in Saudi Arabia. An important aspect influencing adherence is age. Younger patients generally show lower adherence levels to acne treatment [6,15]. Nonetheless, neither our study nor other previous reports have demonstrated this correlation [12,16]. It has been observed that treatment adherence and satisfaction were stronger in younger patients, and older patients tend to adhere to their topical treatment, although they are not fully satisfied with it [12]. Satisfaction with topical treatment might be a factor influencing patients to adhere to the prescribed treatment [4,12]. Interestingly, our data showed that some non-adherent patients reported perceived improvement in their acne despite not following the prescribed treatment regimen. This counterintuitive finding may reflect a common phenomenon in acne management: self-discontinuation after initial clinical improvement. Patients may prematurely stop or modify treatment once they notice positive changes, believing further adherence is unnecessary. This underscores the importance of patient education regarding the need to continue therapy for the full recommended duration to achieve optimal outcomes and prevent relapse. It is important to acknowledge that several potential confounding factors may have influenced our study outcomes. Variables such as disease severity, socioeconomic status, and patient education could have impacted the outcomes measured.

The primary obstacles to acne vulgaris treatment adherence are a weak physician–patient relationship, little knowledge about the severity of acne, influence from media, prescription of equivalent medications, concerns about negative side effects, uncertainty over the appropriate usage of medications, and the overall cost. Moreover, failing to observe progress, the intricacy of the treatment plan, a hectic lifestyle, memory lapses, difficulties in managing routines, and mental health issues have been noted as additional factors that hinder compliance with acne vulgaris therapy [17]. When a patient never begins taking the treatment, we call this primary non-adherence, whereas not utilizing the medication according to given instructions is known as secondary non-adherence. Patients with persistent acne vulgaris have been known to encounter the latter frequently [4,17]. Successful adherence was noted when a single treatment was prescribed [18]. Additionally, the frequency of office visits could influence treatment adherence. Several studies have indicated that patients tend to improve their adherence before upcoming follow-up appointments [4,16,19,20]. Therefore, the frequency of visits may be a contributing factor in enhancing patients’ adherence. Nonetheless, in our analysis, there was no significant correlation between treatment adherence and the quantity of medications or the frequency of office visits. In our study, the most commonly prescribed treatment was topical retinoids (45.5%), and the most frequently reported side effects were dryness (37.9%) and skin stinging (14.1%). Anti-acne topical preparations might affect patients’ adherence to treatment, as 67.2% tolerated their prescribed medications, and 66.2% believed that prescribed topicals are useful for them. One efficient approach to increase adherence is to reduce the adverse effects of the medication prescribed [4,6,8,11,17]. Isotretinoin has a higher rate of adverse effects, according to a few studies, but patients adhere to it more frequently than they do other medications [12,15]. It could be argued that experiencing side effects might remind patients to take their medication [7].

Numerous research studies have indicated that adherence often decreases over time in individuals with chronic conditions [16,21]. Longer treatment duration is a factor that diminishes adherence to acne vulgaris medications [17]. In our study and previously reported studies, long treatment duration (greater than 6 months) was not correlated as a factor in non-adherence [4,12].

Forgetting to take or apply medications could be a reason affecting adherence [10,12,17]. Utilizing technology like text messaging has been linked to enhanced compliance with treatment, improved clinical results, higher attendance at appointments, a reduction in the number of missed medications, and fewer interruptions in treatment [22,23]. Weekly web-based educational resources showed a positive impact on adherence; nonetheless, telephone-based reminders on a daily basis did not improve medication persistence [24]. On the other hand, some studies have failed to report any correlation between automated text messages and improved adherence to the treatment plan [16].

Providing education to the patient in a more direct manner could improve adherence to medication. Maradi Tuchayi et al. [17] proposed that engaging education and effective communication between patients and physicians could enhance adherence to the treatment plan.

Physicians may attribute poor adherence to poor memory or not comprehending treatment application; certain patients intentionally do not adhere to treatment. This may be due to a lack of motivation, misinformation, or fear of side effects [4]. Encouraging patients through effective education about the advantages of their medications, acknowledging patients’ concerns, and honoring patients’ beliefs are all elements that can enhance adherence to treatment in individuals with acne vulgaris [25].

5. Limitations

This research had limitations that should be acknowledged, as they may impact how results are interpreted. We investigated treatment compliance among 198 individuals diagnosed with acne vulgaris who were directed to the dermatology clinic at a teaching hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. An expanded participant pool, which includes additional clinics and hospitals, may be suitable for yielding a more generalized outcome. We employed the validated ECOB questionnaire to assess participants’ subjective adherence to treatment. However, employing more objective measures for evaluating adherence, including pill counts, reviewing prescriptions, analyzing blood or urine medication levels, and utilizing electronic monitoring of medications, would yield more accurate outcomes and minimize recall bias. Our study included patients who were followed up in the clinic, and so assessing primary non-adherence was not applicable. Improving treatment adherence would greatly impact the health system by decreasing the cost of repeated drug prescription, and this is one of the essential goals to be considered to improve the consistency of patients adhering to their prescribed regimen.

6. Conclusions

The present research indicated that compliance with treatment was significantly low among patients with acne vulgaris who received either topical or oral medications. The chronicity of acne vulgaris and its special treatments necessitate a better strategy in improving compliance with medications. Based on this research, patients’ education about the disease and methods of utilizing the prescribed regimen greatly impacts treatment adherence. Based on previously conducted studies, employing technology to prompt patients to apply or take their medications, increasing the number of visits, simplifying treatment regimens, effectively addressing side effects, and adjusting particular elements that could hinder adherence may help enhance treatment compliance. We encourage other dermatologists to frequently employ the ECOB questionnaire during patient appointments to track medication adherence in individuals with acne vulgaris.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. (Sahar Alsifri), Y.A. and S.N.A.; Methodology, S.A. (Saud Aleissa), Y.A., S.N.A. and S.A. (Sahar Alsifri); Formal Analysis, S.N.A. and S.A. (Sahar Alsifri); Data Curation, S.N.A. and S.A. (Sahar Alsifri); Writing—Original Draft, Y.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.A., S.N.A. and S.A. (Sahar Alsifri); Visualization, A.B., B.Z., M.H.A. and J.H.; Supervision, S.A. (Saud Aleissa), A.B., B.Z., M.H.A. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This is an IRB-approved study by King Abdulaziz University’s scientific committee (Reference No 243-22) Non-Intervention (Cross Sectional).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Layton, A.M.; Thiboutot, D.; Tan, J. Reviewing the global burden of acne: How could we improve care to reduce the burden? Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, H. Acne, the Skin Microbiome, and Antibiotic Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun, R.; Daye, M.; Durmaz, K. Acne and rosacea: What’s new for treatment? Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamzadeh, J.; Torabi Kachousangi, S.; Hamzelou, S.; Naderi, S.; Daneshvar, E. Medication adherence and its possible associated factors in patients with acne vulgaris: A cross-sectional study of 200 patients in Iran. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lott, R.; Taylor, S.L.; O’Neill, J.L.; Krowchuk, D.P.; Feldman, S.R. Medication adherence among acne patients: A review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2010, 9, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S.; Crandell, I.; Davis, S.A.; Feldman, S.R. Medical adherence to acne therapy: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2014, 15, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B.; Thiboutot, D.; Gollnick, H.; Finlay, A.Y.; Layton, A.; Leyden, J.J.; Leutenegger, E.; Perez, M.; on behalf of the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Large-scale worldwide observational study of adherence with acne therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010, 49, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyachi, Y.; Hayashi, N.; Furukawa, F.; Akamatsu, H.; Matsunaga, K.; Watanabe, S.; Kawashima, M. Acne management in Japan: Study of patient adherence. Dermatology 2011, 223, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, C.; Park, C.; Chung, J.; Balkrishnan, R.; Feldman, S.; Chang, J. Medication Adherence in Children and Adolescents with Acne Vulgaris in Medicaid: A Retrospective Study Analysis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2016, 33, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grada, A.; Perche, P.; Feldman, S. Adherence and Persistence to Acne Medications: A Population-Based Claims Database Analysis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2022, 21, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Al-Dabagh, A.; Davis, S.A.; Lin, H.-C.; Balkrishnan, R.; Chang, J.; Feldman, S.R. Medication adherence, healthcare costs and utilization associated with acne drugs in Medicaid enrollees with acne vulgaris. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2013, 14, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayran, Y.; İncel Uysal, P.; Öktem, A.; Aksoy, G.G.; Akdoğan, N.; Yalçın, B. Factors affecting adherence and patient satisfaction with treatment: A cross-sectional study of 500 patients with acne vulgaris. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.K.; Balagurusamy, M.; Fung, K.; Gupta, A.K.; Thomas, D.R.; Sapra, S.; Lynde, C.; Poulin, Y.; Gulliver, W.; Sebaldt, R.J. Effect of quality of life impact and clinical severity on adherence to topical acne treatment. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2009, 13, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawin, H.; Beylot, C.; Chivot, M.; Faure, M.; Poli, F.; Revuz, J.; DrÉNo, B. Creation of a tool to assess adherence to treatments for acne. Dermatology 2009, 218, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, S.S.; Cunliffe, W.J.; Goodfield, M.J. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 152, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boker, A.; Feetham, H.J.; Armstrong, A.; Purcell, P.; Jacobe, H. Do automated text messages increase adherence to acne therapy? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi Tuchayi, S.; Alexander, T.M.; Nadkarni, A.; Feldman, S.R. Interventions to increase adherence to acne treatment. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.L.; Dothard, E.H.; Huang, K.E.; Feldman, S.R. Frequency of Primary Nonadherence to Acne Treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yentzer, B.A.; Gosnell, A.L.; Clark, A.R.; Pearce, D.J.; Balkrishnan, R.; Camacho, F.T.; Young, T.A.; Fountain, J.M.; Fleischer, A.B.; Colón, L.E.; et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of strategies to increase adherence in teenagers with acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.R.; Camacho, F.T.; Krejci-Manwaring, J.; Carroll, C.L.; Balkrishnan, R. Adherence to topical therapy increases around the time of office visits. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 57, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.L.; Feldman, S.R.; Camacho, F.T.; Manuel, J.C.; Balkrishnan, R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: Commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 51, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannisto, K.A.; Koivunen, M.H.; Välimäki, M.A. Use of mobile phone text message reminders in health care services: A narrative literature review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnarumma, M.; Fattore, D.; Greco, V.; Ferrillo, M.; Vastarella, M.; Chiodini, P.; Fabbrocini, G. How to Increase Adherence and Compliance in Acne Treatment? A Combined Strategy of SMS and Visual Instruction Leaflet. Dermatology 2019, 235, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, G.; Patel, I.; Chang, J.; Tan, X. Improving adherence to acne treatment: The emerging role of application software. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 7, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.T.; Bussell, J.; Dutta, S.; Davis, K.; Strong, S.; Mathew, S. Medication Adherence: Truth and Consequences. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 351, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.