Simple Summary

The present study examined perch height as a driver of foraging behaviour and hunting success of five sympatric kingfisher species (Common Kingfisher, White-throated Kingfisher, Pied Kingfisher, Stork-billed Kingfisher, and Black-capped Kingfisher) in selected wetland habitats of Kerala, India during 2021–2023. Birds were observed using the focal animal sampling method. Most species used mid-height perches for foraging. The Common Kingfisher showed moderate capture success across all perch heights, whereas the Pied Kingfisher exhibited significantly reduced success at higher perches. In contrast, the Stork-billed Kingfisher achieved the highest capture success at mid-height perches (2–5 m). Capture success was weakly and non-significantly negative for the White-throated Kingfisher, while the Black-capped Kingfisher showed a neutral to positive pattern across perch heights. Our findings indicate that differences in perch height among species represent a form of functional adaptations or resource partitioning, thereby reducing interspecific competition among sympatric species.

Abstract

Sympatric species are closely related taxa that coexist within the same habitat through niche partitioning, and kingfishers serve as an ideal group for studying such ecological mechanisms. The present study examined the perch height in relation to foraging behaviour and hunting success of five kingfisher species: Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), White-throated Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis), Pied Kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), Stork-billed Kingfisher (Pelargopsis capensis), and Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata). The study was conducted between 2021 and 2023, across seven habitat types in Kerala, India (Kadalundi–Vallikkunnu Community Reserve (KVCR) mangroves, Kallampara mangroves, Vadakkumpad mangroves, Vazhakkad agroecosystem, Mavoor wetland, Sanketham wetland, and Elathur beach). A generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a binomial distribution and logit link function was used to analyze hunting success across species. The model indicated that the effect of perch height on hunting success varied among species, though neither perch height nor species identity alone had a significant effect. Most species favored mid-height perches (2–5 m) for foraging, with the Common Kingfisher exhibiting moderate success across all heights and habitats. The Pied Kingfisher showed significantly reduced success at higher perches, while the Stork-billed Kingfisher achieved the highest success at mid-heights (2–5 m). The White-throated Kingfisher showed a non-significant negative association with capture success, whereas the Black-capped Kingfisher exhibited a neutral to positive relationship across perch heights. Among all variables tested, prey availability emerged as the sole significant predictor of hunting success, indicating that prey abundance is the principal determinant of foraging efficiency in tropical wetlands, rather than environmental conditions. Our findings confirm a pattern of vertical stratification in resource partitioning among sympatric kingfisher species and underscore the importance of conserving habitats that retain natural perch sites of varying heights.

1. Introduction

Understanding how foraging strategies vary among sympatric species is critical to elucidating the ecological mechanisms that allow coexistence and niche differentiation. Among avian predators, foraging behaviour is often shaped by habitat structure and environmental conditions [1,2]. Structural attributes such as vegetation density and perch height can directly modulate foraging success through vertical variation within the environment [3,4]. Differences in vertical foraging strata (i.e., the height from which individuals hunt) have significant influence on prey detectability, accessibility, and ultimately, hunting outcomes [3,5]. Environmental parameters including water temperature, humidity, and turbidity may also exert indirect effects on the hunting success of carnivorous birds by altering prey availability and mobility [6,7,8].

Wetlands are dynamic ecosystems where microhabitat features such as perch availability, water clarity, and prey density vary substantially [8,9,10,11]. These microhabitat gradients can shape predator-prey interactions and affect species’ foraging efficiency [12]. In these habitats, foraging height influences foraging success and is determined by prey type, visibility and strike range at different vertical levels [3,13].

Wetlands support sympatric species that often share space and resources, which can lead to interspecific interactions when their ecological needs overlap [14,15]. Interspecific competition for food resources is intense in multi-species assemblages, forcing them to adopt strategies to reduce niche overlap [16,17]. Resource partitioning along vertical axes is a well-documented strategy, in which co-existing species exploit different strata to reduce competitive pressure [16,18]. Previous studies on bird groups such as raptors and insectivores have documented clear vertical partitioning that facilitates co-existence [19,20]. However, such studies on piscivorous guilds such as kingfishers remain limited [21,22].

Kingfishers (Family: Alcedinidae; Order: Coraciiformes) are a group of small to medium sized birds with a cosmopolitan distribution [23,24]. They represent an ecologically diverse group of predatory birds known for their specialized foraging techniques and dependence on aquatic or semi-aquatic prey [23,25,26]. Kingfishers inhabit a wide range of habitats and prey on fish, frogs, insects, reptiles, and caterpillars [27]. The coexistence of multiple kingfisher species within the same area provides an excellent model to study ecological niche partitioning [21,22].

In tropical wetlands, where ecological interactions are particularly complex, sympatric kingfisher species often share habitats but may segregate their niches through differences in perch height used for hunting, prey specialization, or temporal patterns of activity [28,29]. While some studies have examined kingfisher foraging ecology [21,28,30], the effect of vertical hunting strata on prey selection and capture success is poorly understood, especially in Indian tropical ecosystems with complex sympatric interactions [31]. Addressing this gap is critical for advancing theoretical ecology and for informing wetland management and biodiversity conservation strategies. Given that wetlands are under increasing anthropogenic pressure [7,32] understanding the behavioral and ecological adaptations of top predators such as kingfishers is of particular relevance.

In this context, the present study investigates the perch height, prey capture and hunting success of a sympatric kingfisher community in a tropical wetland. The objectives were to assess the prey capture across different perch height levels among kingfisher species, and to compare the hunting success of each species across these vertical strata. Based on ecological theory on niche partitioning and previous studies on vertical stratification in avian predators, we hypothesized that perch height plays a key role in shaping hunting success in sympatric kingfisher species. Specifically, we expected hunting success to vary across perch height categories. We hypothesized that species specific variation in perch height use represents a mechanism of vertical resource partitioning that facilitates species specific adaptive behaviour among sympatric kingfishers by reducing interspecific competition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

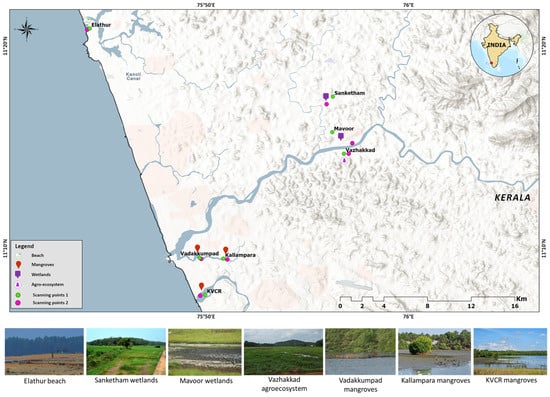

The study was carried out across seven sites situated in the northern region of Kerala: Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu Community Reserve (KVCR) mangroves, Kallampara mangroves, Vadakkumpad mangroves, Vazhakkad agroecosystem, Mavoor wetland, Sanketham wetland, and Elathur beach (Figure 1). All habitats fall under the Tropical Monsoon Climate (Am) zone, characterised by high rainfall (southwest and northeast monsoons), high relative humidity, and warm temperatures throughout the year [7,33]. Vegetation across the study landscapes ranges from agroecosystems dominated by mixed crops, to freshwater wetlands, coastal beaches, tidal mudflats, and true mangrove ecosystems along the Kozhikode coastline [7,34]. Elathur beach was included in the study due to the occurrence of the Black-capped Kingfisher, a winter visitor to Kerala.

Figure 1.

Map showing the study areas. Two scanning points for each study area are shown on the map. These points were selected based on the occurrence of the study species following an intensive pilot survey.

KVCR mangroves (11.127580 N, 75.829649 E) constitute a coastal wetland along the Arabian Sea, spanning the Kozhikode and Malappuram districts of Kerala. The wetland is characterized by mudflats, mangroves, sandy beaches, and a rapidly expanding sand bed located between the beach and the mudflat. Avicennia officinalis is the most abundant mangrove species in the reserve. The Kadalundi River, which drains into the Arabian Sea at the mouth of KVCR, flows through the reserve. The habitat is influenced by tidal action, and during low tide the sand bed, which restricts water flow between the river and the sea, becomes prominently visible [7,32,34,35,36,37].

Kallampara mangroves (11.158767 N, 75.847927 E), located in Feroke Grama Panchayath of Kozhikode district, represents an inland mangrove habitat situated approximately 4 km from the KVCR mangroves and 5 km from Chaliyam beach. The river flowing through the Kallampara mangroves merges with the Chaliyar River at Chaliyam, and together they drain into the Arabian Sea [7,34,37].

Vadakkumpad mangroves (11.158334 N, 75.829306 E) are inland mangroves located approximately 2 km from the Kallampara mangroves, 3 km from Chaliyam Beach and 4 km from KVCR mangroves. The area falls within Changaroth Grama Panchayath, Kozhikode district. A railway bridge spans the river at Vadakkumpad [7,37,38].

The Vazhakkad agroecosystem (11.244157 N, 75.951707 E), located on the banks of the Chaliyar River in Vazhakkad village, Kondotty Taluk, Malappuram district, comprises wetlands and agricultural fields where rice cultivation and banana plantations are practiced. This habitat supports numerous species of waterbirds and shorebirds, both resident and migratory [7,21,37,38].

Mavoor wetlands (11.260530 N, 75.938780 E) belong to Mavoor Panchayath of Kozhikode district, located approximately 20 km from Kozhikode town. The wetland lies about 7 km away (2 km aerial distance) from the Vazhakkad agroecosystem. Palliyol, Pipeline, and Kalpalli are the major areas comprising the Mavoor wetlands, with Pipeline hosting a heronry where many waterbird species breed [7,21,37,39].

Sanketham wetlands (11.288627 N, 75.934299 E), located in Chathamangalam Grama Panchayath of Kozhikode district, span approximately 15 ha and comprise agricultural land, wetlands, and diverse vegetation. The habitat is positioned approximately 3 km from Mavoor wetlands and is noted for its rich biodiversity, including several migratory waterbird species.

Elathur Beach (11.346638 N, 75.735889 E), within Kozhikode Corporation, is bounded by the Arabian Sea to the west and the Korappuzha River to the north. The adjoining backwaters (11.347967 N, 75.736913 E) and tidal inlets within the human settlements serve as major attractions for kingfishers.

2.2. Study Species

Five species of kingfishers (Order: Coraciiformes; Family: Alcedinidae) were considered for the present study: Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), White-throated Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis), Pied Kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), Stork-billed Kingfisher (Pelargopsis capensis), and Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata).

The Common Kingfisher is a small, brightly colored bird with a short tail and a pointed bill. The sexes are dimorphic, with males having entirely black bills, while females show an orange lower mandible and black upper mandible [40,41]. The species forages using two main strategies: hovering and diving from a perch, and was recorded primarily near water sources across all selected study areas.

White-throated Kingfisher is a medium-sized, brightly coloured bird, easily recognised by the prominent white patch extending from its throat to breast. Its head and underparts are chestnut, while the wings and tail are bright blue. The species is widespread and was recorded across all the habitats studied. It typically forages from a perch and is a generalist carnivore [40,42].

Unlike other kingfishers, Pied Kingfisher is characterized by black and white plumage with black bills. Sexes are dimorphic. Males are identified by two distinct black bands on the breast while females have a single, broken band. They can forage by hovering and from a perch as Common Kingfisher [40,43]. They are mostly seen near water bodies and were recorded only from Vazhakkad agroecosystem, Mavoor wetlands and Sanketham wetlands.

The Stork-billed Kingfisher is a tree kingfisher that primarily prefers wooded areas near water bodies and forages from a perch. It is the largest of the five selected species, characterized by a large red bill, brown head, greenish-blue upperparts, and buff underparts [40,44]. The species was observed and recorded at all study sites.

Black-capped Kingfisher, a winter visitor to Kerala has a dark blue and black plumage, white neck, light brown underpart, a black head and red bills [40,45]. The species forage from a perch and were recorded from KVCR mangroves, Vadakkumpad mangroves and Elathur beach. It is red listed as Vulnerable (VU) by IUCN with a declining population [7,46].

Stork-billed Kingfisher, White-throated Kingfisher, Pied Kingfisher, and Common Kingfisher are resident species in Kerala and are considered Least Concern (LC) globally, however they are undergoing noticeable declines within their local ranges [7,41,42,43,44,45].

2.3. Field Study Methods

2.3.1. Observational Protocol

Kingfisher observations were conducted using the focal animal sampling method, in which a single individual is observed for a defined period of time [47]. Once an individual was selected, the presence of other kingfishers in the area was disregarded. Observations began as soon as a bird was detected and continued until it moved out of view. Each individual was monitored for a 30-min focal session, and if it remained visible afterward, a new session was initiated following a 5-min pause. For each session, the start and end times were recorded, along with additional parameters such as perch height, prey type, hunting success, and other relevant behaviours.

The sexes of the observed individuals were recorded as either male or female, while those that could not be identified were marked as unknown [40,41,42,43,44,45]. Observations were carried out in the study area thrice in a month (2021–2023) using a binocular (Nikon 10 ×50, Nikon Corporation, Dongguan, China) and a 4 k high speed motion video camera (Nikon D500, Nikon Corporation, Ayutthaya, Thailand + Nikkor 200–500 mm lens, Nikon Corporation, Ayutthaya, Thailand). Behavioural data for the focal individuals were recorded, and the videos were later examined using the play-and-replay approach.

2.3.2. Prey Identification and Hunting Success

Prey captured by the focal bird was documented either through direct binocular observations or later via the play-and-replay method. Prey that could not be identified were noted as unknown. While species-level identification was frequently difficult, distinctly recognizable prey such as dragonflies, frogs, lizards, and crickets were recorded individually. All other prey items were classified into broader categories, including fish, insects, amphibians, and reptiles.

Any attempt made by the focal individual resulted in the capture and consumption of prey was considered a hunting success [21]. Not all the attempts ended in success and the number of attempts preceding a successful hunt varied among the kingfisher species. Instances in which prey was captured but not consumed were also observed and recorded but not counted as hunting success.

2.3.3. Perch Height

For each foraging attempt, the perch height recorded was from which the bird initiated the attempt. Perch height and line of sight varied among species and were measured relative to either the ground or the water surface, depending on context [21]. Heights above ground were measured directly using a measuring tape, whereas heights above water were visually estimated and later cross-verified with a mobile application (AR Measure Tape: Smart Ruler). All measurements were taken only after the bird had departed to ensure that the focal individual was not disturbed. The approximate hovering height was also accounted as perch height in the case of hovering species—Common Kingfisher and Pied Kingfisher.

2.3.4. Estimation of Water Temperature and Humidity

Water temperature and humidity were measured thrice in every month during 2021–2023. A digital Salinity meter (Thomas@Traceable salinity meter, Sasebo, Japan) was used for measuring water temperature and a digital Hygrometer (Besantek BST-HYG2 Large Display Thermo-Hygrometer, Shenzhen, China) for humidity [7].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We used a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a binomial distribution and logit link function to identify significant predictors of hunting success. The predictor variables included: Sex, Prey type, Perch height, Hovering behavior, Climate variables (Water temperature, Humidity). We then performed an Analysis of Deviance (ANOVA) with a Chi-square test to evaluate the significance of each variable. To assess factors influencing hunting success, we fitted a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a binomial distribution and logit link function, as our response variable (hunting success) was binary (1/0). The model included the interaction between perch height and species as fixed effects, while habitat was incorporated as a random effect to account for site-specific variability. Since the data were not normally distributed, the binomial family with a logit link was appropriate for modeling binary outcomes.

We evaluated potential overdispersion using the performance package, confirming that the model adequately accounted for data variability. To test the significance of each term including interactions, we performed Type III Wald chi-square tests via ANOVA. We used the ‘ggplot2: R version 4.2.3’ package [48] to visualize the relationships. All statistical analyses were conducted in R software [49].

3. Results

The sampling effort yielded a total of 628 kingfisher observations. The Common Kingfisher was both the most frequently observed species (n = 353) and the most widely distributed, being recorded in all 7 sites, during all 12 months, and across all three study years (2021–2023). The White-throated Kingfisher was the second most common species (n = 171) and showed similarly broad ecological and temporal occurrence, appearing in all 7 sites and all 12 months over the same three-year period. In contrast, the remaining three species exhibited more restricted distributions. The Stork-billed Kingfisher was observed 58 times in all 7 sites over 11 months (2021–2023). The Pied Kingfisher (n = 24) and Black-capped Kingfisher (n = 22) were the rarest, each recorded in only 2 sites, and their monthly occurrences were more limited (8 and 6 months, respectively). Notably, the Black-capped Kingfisher was not recorded in 2023 (Tables S1 and S2).

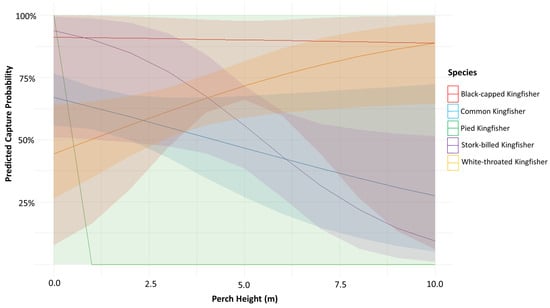

The models detected no significant main effects of Perch height (p = 0.954) or Species alone (p > 0.05). However, species-specific patterns emerged, for instance, Pied Kingfisher have an implausibly large coefficient (β = 12.56, p = 0.98) and standard error (SE = 874.0) reflect data sparsity at specific perch heights, suggesting incomplete sampling when compared with the other species. On the other hand, White-throated Kingfisher showed a non-significant negative association with capture success (β = −2.57, p = 0.301), potentially indicating context-dependent foraging strategies (Table 1 and Figure 2). Habitat showed minimal variability (variance = 0.091, SD = 0.30), suggesting little effect on capture rates across different habitats (Table S1).

Table 1.

Summary of fixed and random effects from the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) evaluating the influence of perch and species on hunting success. The table presents fixed-effect estimates along with their standard errors (Std. Error), z-values, and corresponding p-values. Interaction terms (Perch × Species) represent species-specific variations in response to perch type. None of the fixed effects were statistically significant (p > 0.05), indicating that perch type and species had limited influence on the response variable in this model. The random effect of Habitat (standard deviation = 0.301) accounts for variation among habitats.

Figure 2.

Marginal effects of perch height on predicted capture success by kingfisher species (Red—Black-capped Kingfisher, Blue—Common Kingfisher, Green—Pied Kingfisher, Purple—Stork-billed Kingfisher, Orange—White-throated Kingfisher) in India.

Diagnostic checks using the performance package confirmed the model adequately accounted for overdispersion (dispersion ratio = 1.019). The analysis revealed a statistically significant perch × species interaction (p = 0.025), indicating that the effect of perch height on hunting success varied by species. Neither perch height (p = 0.954) nor species alone (p = 0.104) showed significant main effects (Table 2, Tables S1 and S2). Factors, including sex, hovering behavior, water temperature, and humidity, did not show significant associations with hunting success; only the capture of a specific prey type had a significant effect (Table 3 and Table S3).

Table 2.

Analysis of Deviance (Type III Wald χ2 Tests). Significance * p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Summary of effects from the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) evaluating the influence of sex, type of prey, perch, hovering, and climate variables on hunting success. The table presents fixed-effect estimates. Significant values < 0.05.

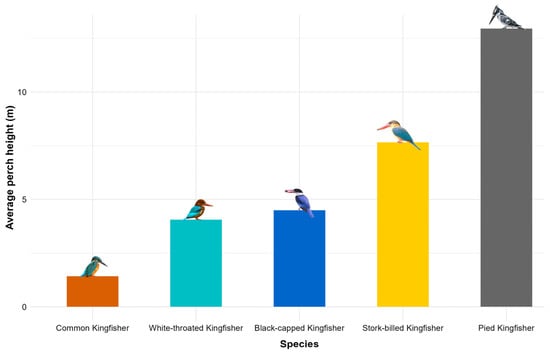

Species exhibited distinct perch-height preferences (Figure 3) and hunting success: Black-capped Kingfishers showed neutral/positive effects across heights. Common Kingfishers displayed moderate success at all heights. Pied Kingfishers had significantly reduced success at high perches while Stork-billed Kingfishers performed best at mid-heights (2–5 m), and White-throated Kingfishers showed context-dependent results, likely influenced by prey availability or habitat-specific factors. These findings suggest that optimal hunting success is influenced by species-specific perch-height preferences, with mid-heights (2–5 m) being favorable for most species.

Figure 3.

Bar diagram showing average perch height (m) for Common Kingfisher, White-throated Kingfisher, Black-capped Kingfisher, Stork-billed Kingfisher and Pied Kingfisher.

4. Discussion

Our findings revealed species-specific variations in perch height preference and hunting success. The most notable result was the significant interaction between perch height and species in predicting hunting success. Although perch height and species alone did not have significant main effects, the interaction term was statistically significant. This supports the idea that kingfishers exhibit vertical resource partitioning, a mechanism that reduces direct competition for prey resources and facilitates species-specific foraging adaptations, as described in classic ecological theory [16,18,19].

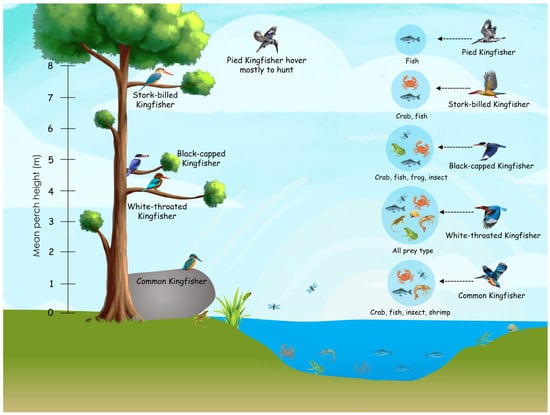

Most kingfisher species in the present study preferred perches at mid-heights (Figure 4). However, hunting success varied among species depending on their perch height and prey preferences. The positive relationship between body size and perch height indicates that larger kingfisher species typically select higher perches and target larger prey. These elevated perches likely provide greater potential energy or momentum for capturing prey in deeper waters, whereas smaller species tend to use lower perches suited for hunting smaller prey in shallower habitats (Figure 4) [17,30].

Figure 4.

Representation of mean perch heights of five species of kingfishers (Common Kingfisher, Pied Kingfisher, White-throated Kingfisher and Black-capped Kingfisher) and their prey in an aquatic ecosystem.

Common Kingfishers exhibited moderate foraging success across all perch height ranges, which was consistent with previous studies of Borah et al. [14] and Noor et al. [50]. Relative to their body size, they exhibited a narrower niche and accordingly used different perches along water bodies with shallow depths [14,17,41]. Though they have moderate success at all perch heights, they prefer lower perches across the habitats. Hunting small fishes and shrimps in shallow water demands minimal energy, allowing individuals to forage effectively from ground-level positions without the need for elevated perches (Figure 4) [17,30].

Our analysis indicated a reduced hunting success of Pied Kingfishers at higher perches. This species primarily captures fish by either hovering or diving from a perch and success rates are generally lower during hover hunting than during perch-based hunting [51]. In the present study, most observed individuals engaged in hover hunting, which likely contributed to the lower success rates recorded. Even though hover hunting is less successful, Pied Kingfishers prefer this method to scan for prey in open waters, especially when suitable perches are limited or unavailable [51]. Furthermore, the population of Pied Kingfishers has been declining drastically in recent years [7], resulting in fewer sightings and a smaller sample size in this study. The relatively high standard error associated with this species in the model further reinforces the inference of limited data availability.

Our observations revealed that Stork-billed Kingfishers achieved higher hunting success from mid-elevation perches (2–5 m) across the study sites. This was also consistent with previous study [44]. They are highly sensitive and use elevated vegetation to survey broader prey fields; a strategy similarly observed in other large-bodied piscivores [7,23,44]. For example, in the present study, higher perches (≥5 m) like electric lines were preferred in open habitats like agroecosystems that lack well wooded vegetation near water bodies. Perches below 5 m were often preferred at mangrove habitats which provide better perches with cover. However, hunting success was consistent at mid-elevation perches across the habitats.

Black-capped Kingfishers exhibited positive or neutral hunting success across perch heights. This pattern may be attributed to their reliance on prey available within a limited range of accessible habitats. As winter visitors to Kerala [7], extensive habitat scanning during their short stay may be energetically costly and could increase predation risk. This suggests a potential adaptation to efficiently exploit a specific area within their temporary habitat [7,45].

Interestingly, White-throated Kingfishers displayed context-dependent success rates. The non-significant negative association with hunting outcomes suggests that prey type and local habitat features may play a more dominant role than perch height in determining their success. This species is known for its broader diet and variable hunting strategies, which may explain the lack of a consistent pattern [52]. As a contextual hunter, the White-throated Kingfisher can modify its foraging strategy based on prey accessibility, often shifting to terrestrial prey such as insects, caterpillars, and lizards during low-tide periods or under high turbidity conditions, or when suitable perches are unavailable near water bodies. They can also hunt in midair when targeting flying dragonflies, often using electric lines as perches.

White-throated Kingfisher, and Black-capped Kingfisher showed only slight variation in perch height which may be attributed to their relatively similar body sizes [42,45]. The Pied Kingfisher primarily consumes fish and is mostly observed near water bodies, either hovering or perching while hunting [43,51]. Throughout the study period, the species predominantly hunted by hovering, resulting in the highest average perch-height preference observed (Figure 3). The White-throated Kingfisher, with a more diverse diet (including small insects to large fish) and a context-dependent foraging strategy, forage across various habitats [42]. The White-throated Kingfisher exhibits a broad and predominantly terrestrial diet, feeding extensively on insects, lizards, and small amphibians, with relatively fewer aquatic prey [23,24,52]. Although the Black-capped Kingfisher also has a complex diet, its local migratory behavior and tendency to utilize smaller areas may limit the range of available prey. Additionally, its preference for higher perches for safer foraging further restricts it to targeting only the prey present within this limited range.

Habitat showed minimal variability in hunting success in the present study. This suggests that despite habitat-level differences in perch availability, hunting success is largely maintained within species-specific perch-height ranges. Along with perch height and habitat preferences, the study examined environmental and behavioural variables that determine hunting success. Factors, including sex, hovering behavior, water temperature, and humidity, did not show significant associations with hunting success. However, climatic variables such as humidity and water temperature may have differential effects on prey types and in turn, alter their availability, thereby influencing the foraging success of specific kingfisher species [7,53]. Additionally, turbidity may be a major factor restricting prey visibility, as kingfishers typically forage in clear water [54,55,56,57]. Shifa et al. [7] observed a gradual increase in turbidity over the years in the habitats studied, which was linked to reduced kingfisher abundance. While past research highlights the negative effect of turbidity on their numbers, this study did not directly examine its effect on hunting success. Further research is therefore recommended to address this gap.

In the sympatric kingfisher community studied, prey type appears to be a good indicator of hunting success. However, because over 40% of captured prey could not be fully identified, further research is needed. Characteristics such as prey abundance and detectability are central determinants shaping foraging efficiency. This supports previous findings that prey density often outweighs behavioral or morphological factors in determining hunting success among birds [58,59]. Further research should explore how prey distribution and microhabitat features modify these relationships.

Vertical partitioning among sympatric species is a well-documented strategy in birds, especially among insectivores [20,29,60]. The present study is one of the few assessments that quantify this strategy in a tropical kingfisher community, using detailed field observations and statistical modeling. The observed differences in perch heights suggest that niche differentiation is at least partially mediated by vertical space, allowing ecologically similar species to exploit different microhabitats within the same wetland. However, perch height cannot alone explain prey choice or capture success. Thus, future research is recommended to establish the relationship between prey type and hunting success by considering multiple interrelated traits such as body size, bill shape, bill length, visual field and water clarity.

These findings have important ecological implications. In degraded or urban wetlands with fewer perch options, the loss of vertical complexity may particularly affect species with strong perch-height preferences. Moreover, heavy metal toxicity, anthropogenic pressures, climate change, and declining fish density across habitats have collectively led to a marked decrease in kingfisher abundance over the years [7,37]. The combined effects of reduced prey availability and loss of vertical complexity may further intensify interspecific competition among sympatric species. Therefore, conservation efforts should prioritize preserving or restoring vertical habitat structures, including natural perches and snags, to maintain ecological heterogeneity.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that vertical foraging strata influences the hunting success of kingfishers in Asian tropical wetlands, particularly through species-specific interactions with perch height. The observed species-specific patterns in perch height suggest mechanisms of vertical niche partitioning that facilitate resource partitioning. These insights enhance our understanding of foraging ecology in structurally complex habitats and underscore the importance of conserving vertical habitat features in wetland ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/birds7010005/s1, Table S1: Kingfisher observations across habitats: frequency, number of species present, hunting success percentage, and average perch height. Table S2: Summary of kingfisher species: number of observations, percentage of total records, number of occupied sites, hunting success rates, types of prey identify in the diet of birds and average perch height. Table S3: Mean water temperature and humidity across seven study sites in India (2021–2023).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.A.; Methodology, K.M.A.; Formal Analysis, K.M.A. and J.A.A.-B.; Data Curation, C.T.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.T.S., K.A.R., S.B.M., M.N.M., T.R.A. and K.M.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.T.S., J.A.A.-B., K.A.R., T.J., P.T., S.B.M., M.N.M., T.R.A. and K.M.A.; Resources—T.J. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.T Shifa was supported by UGC-CSIR 08/739(0005)/2021-EMR-I. and A-B.J.A. was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; Process #141025/2022-0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Remsen, J.; Scott, R. A classification scheme for foraging behavior of birds in terrestrial habitats. Stud. Avian Biol. 1990, 13, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, M.L.; Marcot, B.G.; Mannan, R.W. Wildlife-Habitat Relationships: Concepts and Applications; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.; Wallander, J.; Isaksson, D. Predator perches: A visual search perspective. Funct. Ecol. 2009, 23, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanle, J.; Duguid, M.C.; Ashton, M.S. Legacy Forest structure increases bird diversity and abundance in aging young forests. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, R.; Dias, M.P.; Chumbinho, A.C.; Bloise, C. Influence of perch height and vegetation structure on the foraging behaviour of little owls Athene noctua: How to achieve the same success in two distinct habitats. Ardea 2011, 99, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.J.; Elmberg, J. Ecosystem services provided by waterbirds. Biol. Rev. 2014, 89, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifa, C.T.; Dayananda, S.K.; Xu, Y.; Rubeena, K.A.; Muzaffar, S.B.; Nefla, A.; Jobiraj, T.; Thejass, P.; Reshi, O.R.; Aarif, K.M. Long-term anthropogenic stressors cause declines in kingfisher assemblages in wetlands in southwestern India. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 111062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, R.; Schalcher, K.; Séchaud, R.; Michler, S.; Apolloni, N.; Roulin, A.; Almasi, B. Influence of prey availability on habitat selection during the non-breeding period in a resident bird of prey. Mov. Ecol. 2023, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Gosselink, J.G. Wetlands, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, J.E.; Bortolotti, J.Y.; Rooney, R.C. Wetland microhabitats support distinct communities of aquatic macroinvertebrates. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2018, 33, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husen, M.A.; Storey, R.G.; Gurung, T.B. Water quality patterns, trends and variability over 17+ years in Phewa Lake, Nepal. Lakes Reserv. Sci. Policy Manag. Sustain. Use 2023, 28, e12426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carothers, J.H.; Jaksić, F.M. Time as a niche difference: The role of interference competition. Oikos 1984, 42, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.B.A.; Barnard, C.J. Prey selection by plovers: Optimal foraging in mixed species groups. Anim. Behav. 1984, 32, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, J.; Ghosh, M.; Harihar, A.; Pandav, B.; Gopi, G.V. Food-niche partitioning among sympatric Kingfishers in Bhitarkanika mangroves, Odisha. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 2012, 109, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Tryjanowski, P.; Jiguet, F.; Han, Z.; Wang, H. Distribution pattern and niche overlap of sympatric breeding birds along human-modified habitat gradients in Inner Mongolia, China. Avian Res. 2025, 16, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.H. Population ecology of some warblers of Northeastern coniferous forests. Ecology 1958, 39, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, S.; Katoh, K. Food-niche differentiation in sympatric species of kingfishers, the Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis and the Greater Pied Kingfisher Ceryle lugubris. Ornithol. Sci. 2008, 7, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarto, S.; Timothy, O.B.; Margaret, K.; Jatna, S.; Adi, B. Resource partitioning among kingfishers in Tangkoko Duasudara Nature Reserve, North Sulawesi. Trop. Biodivers. 1999, 6, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Terborgh, J.W. The conservation status of neotropical migrants: Present and future. In Migrant Birds in the Neotropics: Ecology, Behavior, Distribution, and Conservation; Keast, A., Morton, E.S., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1980; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Naikatini, A.N.; Keppel, G.; Brodie, G.; Kleindorfer, S. Interspecific Competition and Vertical Niche Partitioning in Fiji’s Forest Birds. Diversity 2022, 14, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renila, R.; Bobika, V.K.; Nefla, A.; Manjusha, K.; Aarif, K.M. Hunting behavior and feeding success of three sympatric kingfishers’ species in two adjacent wetlands in Southwestern India. Proc. Zool. Soc. 2020, 73, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, L.C.; Ortega, Z. Perch selection of three species of kingfishers at the Pantanal of Brazil. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 46, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, C.H.; Fry, K.; Harris, A. Kingfishers, Bee-Eaters and Rollers: A Handbook; Cristopher Helm Publishers: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (Eds.) Handbook of the Birds of the World, Mousebirds to Hornbills; Lynx Editions: Barcelona, Spain, 2001; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Woodall, P.F. Family Alcedinidae (Kingfishers). In Handbook of the Birds of the World, Mousebirds to Hornbills; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Eds.; Lynx Editions: Barcelona, Spain, 2001; Volume 6, pp. 130–249. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, D.W.; Billerman, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. Kingfishers (Alcedinidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; Billerman, S.M., Keeney, B.K., Rodewald, P.G., Schulenberg, T.S., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, A.; Miranda, R.; Arizaga, A. Fish Prey Selection by the Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis in Northern Iberia. Acta Ornithol. 2012, 47, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodacki, G.D.; Skipper, B.R. Partitioning of Foraging Habitat by Three Kingfishers (Alcedinidae: Cerylinae) along the South Llano River, Texas, USA. Waterbirds 2019, 42, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmel, K.; Riegert, J.; Paul, L.; Novotný, V. Vertical stratification of an avian community in New Guinean tropical rainforest. Popul. Ecol. 2016, 58, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, A.; Arizaga, J.; Salvo, I.; Miranda, R. An experimental evaluation of the influence of water depth and bottom color on the Common kingfisher’s foraging performance. Behav. Process. 2013, 98, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, R.; Santos, E.S.A. Tropical Bird Communities. In Tropical Biology and Conservation Management; Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS): Paris, France, 2007; Volume 8, pp. 1–22. Available online: https://www.eolss.net/sample-chapters/c20/e6-142-tz-07.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Aarif, K.M.; Prasadan, P.K.; Babu, S. Conservation significance of the Kadalundi-Vallikunnu Community Reserve. Curr. Sci. 2011, 101, 717–718. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifa, C.T.; Rubeena, K.A.; Abbas, A.; Jobiraj, T.; Thejass, P.; Nefla, A.; Muzaffar, S.B.; Aarif, K.M. Kingfisher in Mangroves: Unveiling Ecological Insights, Values, and Conservation Concerns. In Mangroves in a Changing World: Adaptation and Resilience; Padmakumar, V., Shanthakumar, M., Eds.; Wetlands: Ecology, Conservation and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 13, pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarif, K.M.; Muzaffar, S.B.; Babu, S.; Prasadan, P.K. Shorebird assemblages respond to anthropogenic stress by altering habitat use in a wetland in India. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarif, K.M.; Nefla, A.; Nasser, M.; Prasadan, P.K.; Athira, T.R.; Muzaffar, S.B. Multiple environmental factors and prey depletion determine declines in abundance and timing of departure in migratory shorebirds in the west coast of India. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifa, C.T.; Angarita-Báez, J.A.; Rubeena, K.A.; Jobiraj, T.; Thejass, P.; Muzaffar, S.B.; Nayeem, M.; Aarif, K.M. Declining kingfisher assemblages in the face of hazardous metal pollution in tropical Wetlands. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2025, 17, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarif, K.M.; Nefla, A.; Rubeena, K.A.; Xu, Y.; Bouragaoui, Z.; Nasser, M.; Shifa, C.T.; Athira, T.R.; Jishnu, K.; Anand, J.; et al. Assessing environmental change and population declines of large wading birds in Southwestern India. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 25, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobika, V.K.; El-H Khemis, M.D.; Renila, R.; Manjusha, K.; Aarif, K.M. Does substrate quality influence diversity and habitat use of waterbirds? A case study from wetlands in southern India. Ekologia 2021, 42, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmett, R.; Inskipp, C.; Inskipp, T. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press & Christopher Helm: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–528. [Google Scholar]

- Woodall, P.F. Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, P.F.; Kirwan, G.M. White-throated Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, P.F. Pied Kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, P.F.; Kirwan, G.M. Stork-billed Kingfisher (Pelargopsis capensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, P.F.; Kirwan, G.M. Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International. Halcyon pileata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022. Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/black-capped-kingfisher-halcyon-pileata (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Altmann, J. Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Noor, A.; Mir, Z.; Khan, M.; Kamal, A.; Habib, B.; Ahmad, K.; Shah, J. Diurnal activity pattern and foraging behaviour of common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) in Dal Lake, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. Res. 2014, 2, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, M.; Marco, H. The role of experimental perches on the hover and perch hunting preferences of the Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis. Ostrich 2023, 94, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ripley, S.D. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan: Together with Those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka (Compact Edition); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; Bombay Natural History Society: Mumbai, India, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, J.M.; Pomeranz, J.F.; Todd, A.S.; Walters, D.M.; Schmidt, T.S.; Wanty, R.B. Aquatic pollution increases use of terrestrial prey subsidies by stream fish. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, M.V.; Kattenfeld, M.G. The role of turbidity as a constraint on predator-prey interactions in aquatic environments. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1997, 40, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E. Particulate Matter, Turbidity, and Color. In Water Quality; Boyd, C.E., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strod, T.; Arad, Z.; Izhaki, I.; Katzir, G. Cormorants keep their power: Visual resolution in a pursuit diving bird under amphibious and turbid conditions. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sibomana, C.; Nduwayezu, P.J. Pollution and Foraging Behavior of Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis in Bujumbura Bay of Lake Tanganyika, Burundi: Conservation Implications. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 3, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.T.; Schultz, J.C. Food availability for forest birds: Effects of prey distribution and abundance on bird foraging. Can. J. Zool. 1988, 66, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildstein, K.L. Migrating Raptors of the World: Their Ecology and Conservation; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mansor, M.S.; Ramli, R. Foraging niche segregation in Malaysian babblers (Family: Timaliidae). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.