Simple Summary

Availability is an often undervalued portion of the detection probability related to a bird’s song rate that can affect our understanding of habitat relationships and density. I documented the probability of detecting a song per minute for common survey lengths in relation to Golden-cheeked Warblers in central Texas, USA. Males sang less when paired, and later in the day and season, and more when conspecific males were singing contemporaneously. These results provide information to improve survey protocols (e.g., optimal survey windows) and also confirm potential issues in predicting density and populations from single-visit point surveys. The biggest concern identified is how differences in pairing success across available breeding habitats can contribute to an availability bias when predicting density.

Abstract

Incomplete detection during auditory point counts includes the component that individuals are present but silent (“availability”). If the probability of being ‘available’ is less than one and is not random with respect to time or space, population estimates that fail to address availability will be biased. I recorded minute-by-minute singing of 60 male Golden-cheeked Warblers (Setophaga chrysoparia) in 2010–2011 (133 surveys; 6517 min) to estimate availability, evaluate predictors, and provide survey guidance. The per-minute availability was 0.45 (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 0.37–0.54). The availability was higher for unpaired versus paired males (0.82 [0.64–0.92] versus 0.30 [0.20–0.42]) and when ≥1 conspecific was singing (0.61 [0.46–0.75] vs. 0.54 [0.39–0.68]). Availability declined across both day of year and hour of day. Aggregating to common survey lengths, the probability of ≥ 1 song per bin increased with duration but showed the same temporal declines: 3 min = 0.61 (0.52–0.70), 5 min = 0.72 (0.63–0.79), and 10 min = 0.83 (0.74–0.90). Temperature had a modest positive effect, clearest at the 10 min bins. Interaction terms among day, hour, and temperature were unsupported (all likelihood ratio tests p > 0.10). These findings indicate that availability is <1 and varies predictably with day and time, implying that point count protocols should standardize survey windows or model availability explicitly.

1. Introduction

Point counts are the most widely used technique for monitoring bird populations [1,2], but the widespread use of point counts to infer abundance or density has garnered controversy because it is difficult to measure the portion of the population being counted [3,4,5]. For this reason, unadjusted point counts are considered an index, but to consider comparisons of indices valid between different habitats or time periods, we must assume the detection probability is constant—that is, the same proportion of the population is being counted in different years or sites [2,6]. Concern over this assumption has driven the development of several design- and model-based techniques to estimate various portions of the detection probability [2,7,8]. Design-based methods attempt to control for sources of variation such as time, the date within the season, and weather conditions when collecting data in the field [1], whereas model-based methods attempt to reconcile detection issues using ancillary data such as the distance to the detected individuals [9], the time of detection [7], repeated surveys within a period of population closure [10], or multiple observers [11]. However, how well these techniques work depends on if the design and model assumptions can be met [5]. One component of the detection probability is availability, or the likelihood that a bird is singing (if reliant on vocalizations to detect presence) given that it is present within the point count radius during a survey [12,13]. Previous studies assessing the availability and singing behavior of passerines have shown that availability is often less than one [13,14,15,16,17]. Singing rates may differ based on pairing status, time of day, day of season, or nesting stage [16,17,18]. Therefore, population estimates based on inferences may be erroneous if differences exist in the proportion of males in various stages.

Golden-cheeked Warblers (Setophaga chrysoparia; hereafter “warbler”) are a federally endangered species in the United States with a restricted breeding and wintering range [19,20]. On their breeding grounds, they are a habitat specialist, nesting exclusively in the juniper and juniper–oak woodlands of central Texas; on their wintering grounds, they are found in the pine–oak forests within Central America [19,20]. Population size estimates vary widely, even within studies, from several thousand breeding pairs to > 200,000 breeding males [20,21,22,23]. While population size is not a specific recovery criterion, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service cited “sufficient breeding habitat has been protected to ensure the continued existence of at least one viable, self-sustaining population in each of eight regions outlined in the plan” as one delisting criteria [20]. Hence, knowledge of how many birds constitute a self-sustaining population, how warbler density varies within potential breeding habitat and across the range, and if survey methods such as point counts are reliable estimators of abundance are necessary. Thus far, studies have shown that warbler density has been overpredicted using multiple modeling approaches and field techniques [24,25,26,27,28], making range-wide population estimates questionable. Inferences regarding density and population size drawn from studies reliant on point count data must ensure that design and model assumptions are met, and that the proportion of the population not detected is random with respect to time and space.

I documented the singing behavior of warblers under a range of conditions and explored the impact of variation in singing behavior on point count performance. My objectives were to (1) estimate the per-minute availability and identify predictors; (2) estimate the availability for 3, 5, and 10 min windows to align with common survey lengths; and (3) describe seasonal patterns in song rate and song types. I predicted that paired males would sing less than unpaired males and that availability would decline throughout the day and season.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

I conducted this study on Balcones Canyonlands Preserve (BCP), Travis County, TX, USA (30.40° N, −97.85° W). BCP is ~12,000 ha urban preserve located along the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau ecoregion, typified by rolling to dissected hills dominated by mixed juniper forests [29]. The climate is characterized as humid subtropical, with long, hot summers and mild winters; annual mean temperatures range from 13 to 27 °C and annual precipitation averages 746 mm [29]. Spring 2011 was exceptionally dry and unseasonably warm due to a developing historic drought [29].

I chose seven 40 ha plots distributed across the BCP to sample within; the density ranged from 0.07–0.48 males per plot. The vegetation structure of all plots comprised closed-canopy woodland/forest dominated by Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei), plateau live oak (Quercus fusiformis), Texas red oak (Q. buckleyi), shin oak (Q. sinuata), cedar elm (Ulmus crassifolia), and black cherry (Prunus serotina).

2.2. Study Species

Male warblers arrive on the breeding grounds in central Texas beginning in early March, with females arriving ~1 week later, and have established territories by late March [30]. Nesting occurs primarily from late March through to mid-June [21,30]. They are socially monogamous and raise 1–2 broods by mid-June [21,30]. Males primarily sing two song types, classified as A and B [14]. Type A song is characterized as a stereotyped, buzzy trill (often described as sounding like “La Cucaracha”), and is associated with territory establishment and advertisement, whereas Type B song is on average longer and lower, is more variable and more individual, and is associated with territorial defense [14]. Song types are easily distinguished by skilled observers in the field.

2.3. Field Methods

I recorded the singing behavior of male warblers from 3 April to 21 May 2010 and from 16 March to 21 May 2011. I chose these sample windows to capture the range of early-to-late breeding stages; singing rates are very low in June. I selected focal males with consideration for ease of monitoring (i.e., I chose males whose territory covered terrain that would make it relatively easy to closely follow them for long periods). Each male was monitored 1–4 times within the breeding season at different times of the day (6:55–16:30 CDT) to evaluate intra- and inter-male variation and the effects of time of day and day of year on singing rates. I surveyed singing behavior under low wind conditions and no precipitation, similar to the conditions that point count surveys are conducted under. I monitored both banded and un-banded males. Banded males were uniquely marked with two or three color bands and a numbered aluminum band issued by the U.S. Geological Survey prior to song sampling as part of long-term monitoring. Banded males were aged as second-year (“SY”) or after-second-year (“ASY”), based on the criteria described by Peak and Lusk (2010) [31]. I delineated each focal male’s territory prior to observation to ensure I knew where to look for the male during availability surveys and throughout the season as part of long-term monitoring.

I sampled singing behavior of each focal male for 30–140 min per observation, beginning shortly after I located him and confirmed his identity. I discontinued the survey if I lost track of the male visually or vocally and discarded any surveys <30 min. For each minute during the observation period, I recorded if I detected the male by song, the song type, the number of conspecifics singing, and presence of a female or fledgling(s). All data was recorded on data forms. For a subsample of intervals, I also recorded the number of songs begun in a minute to calculate the song rate and the song type in order to characterize the relationship between song type and pairing status. I assigned pairing status and breeding stage for each sampling period. I categorized breeding stage as follows: (1) male unpaired during the observation period, (2) male paired during the observation period but pre-nesting, (3) male paired and nest was in the egg stage, (4) male paired and feeding nestlings, and (5) male paired and feeding fledglings. The pairing status and breeding stage could change for males that were surveyed multiple times within a season. I determined the breeding stage via intensive monitoring of the focal males throughout the breeding season and only included males whose breeding stage I was confident of for analyses involving breeding stage.

2.4. Statistical Methods

I truncated the recordings to ≤120 min per survey and included males of known pairing status. I conducted all analyses in R version 4.5.2 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). I modeled minute-level detections (DET; 0/1) with binomial GLMMs (logit link; package glmmTMB). I included male identity and survey ID (unique per male–survey) as random intercepts to account for repeated measures of males and multiple observations per survey. Fixed effects considered were the pairing status, presence of ≥1 conspecific singing, presence of a female, presence of dependent young, territory density (site–year specific), day of year, hour of day, breeding stage, and age (for banded males). Continuous predictors were centered and scaled as needed to aid convergence and interpretation [32]. Fixed effects were evaluated with likelihood ratio χ2 tests (LRT) by comparing the full model to reduced models that dropped the term of interest [33,34]. I obtained model-based marginal means (response scale) with proportional weighting across observed covariate distributions (package emmeans). I also computed an overall, population-level per-minute availability via a marginal estimate with proportional weighting across covariates and a raw mean for comparison.

To align with common point count durations, I aggregated 1 min series into non-overlapping 3, 5, and 10 min bins within male × survey. A bin was one if ≥1 song occurred, and otherwise it was zero. For each bin size, I fitted a binomial GLMM with random intercepts for male and survey, and fixed effects day of year, hour of day (bin midpoint, h), and ambient temperature (°C; Camp Mabry, Austin, TX, USA). I first tested all two-way interactions by LRTs against the additive model; none were supported at any bin size (all p > 0.10), so I retained the additive model for inference. I derived model-averaged availability per bin (marginal, response scale) using proportional weighting.

To evaluate song structure, I decomposed the minute–series into consecutive singing and silent bouts for surveys ≥45 min. The first and last bouts were treated as right censored because the full duration of the bout was not observed. Kaplan–Meier curves estimated bout length distributions, restricted mean lengths (±SE), and their confidence intervals. I tested group differences (singing vs. silent; paired vs. unpaired) using log rank tests (package survival). I used Wald–Wolfowitz runs tests to assess temporal dependence in bout sequences.

Because song types and song rates were also of interest, I assessed two complementary models on the song type and song rate subsets. First, I modeled the probability that a minute was Type A using aggregated counts cbind(nA, n − nA) at the male × survey level (random intercept for male; fixed effects = pairing status, day of year, hour of day, and territory density) in a survey-level binomial GLMM. Second, a minute-level Gaussian GLMM modeled songs·min−1 with song type (A vs. B) plus day of year, hour of day, territory density, and pairing status as fixed effects, and random intercepts for male and survey. These models allow statements about (a) how often Type A songs occur (probabilities) and (b) whether Type A and B songs differ in rate (songs·min−1), while adjusting for the same temporal and ecological covariates. The statistical significance was assessed at α = 0.05.

I included 60 unique males of known pairing status and ≥30 min of observation, in which I detected the focal male by song at least once in 124 of 133 surveys (93%). Nine males not detected by vocalizations during the surveys were detected visually; of these, one male was paired but pre-nesting, six males had nests in the incubation stage, one male was observed feeding fledglings during the survey, and one male had an unknown status. I monitored 44 color-banded males in 97 surveys, totaling 5126 observation min, and 16 un-banded males in 36 surveys, totaling 1391 min. Four banded males were monitored in both years but were treated as independent. The surveys averaged (±SD) 48.8 ± 33.1 (n = 65) and 47.8 ± 24.1 (n = 68) min in 2010 and 2011, respectively. I determined that males were paired during 109 surveys (82%). Five males changed pairing status between surveys (i.e., male was unpaired during ≥1 survey(s) and paired during ≥1 survey(s)). I classified breeding stage in 124 surveys, of which 24, 29, 43, 16, and 12 samples were classified as unpaired, paired but not yet involved in nesting, nest building or female incubating, pair feeding nestlings, and pair feeding fledglings, respectively. I detected conspecifics singing during 0.21 ± 0.41 of the total sampling min.

3. Results

3.1. Availability

Using a binomial GLMM with random intercepts for male and survey (n = 60 males, 133 surveys, 6517 min), the availability per minute was strongly associated with the pairing status, presence of singing conspecifics, day of year, and hour of day, but not with the presence of females or fledglings, territory density, or year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of predictors on per-minute availability of male Golden-cheeked Warblers from binomial GLMM.

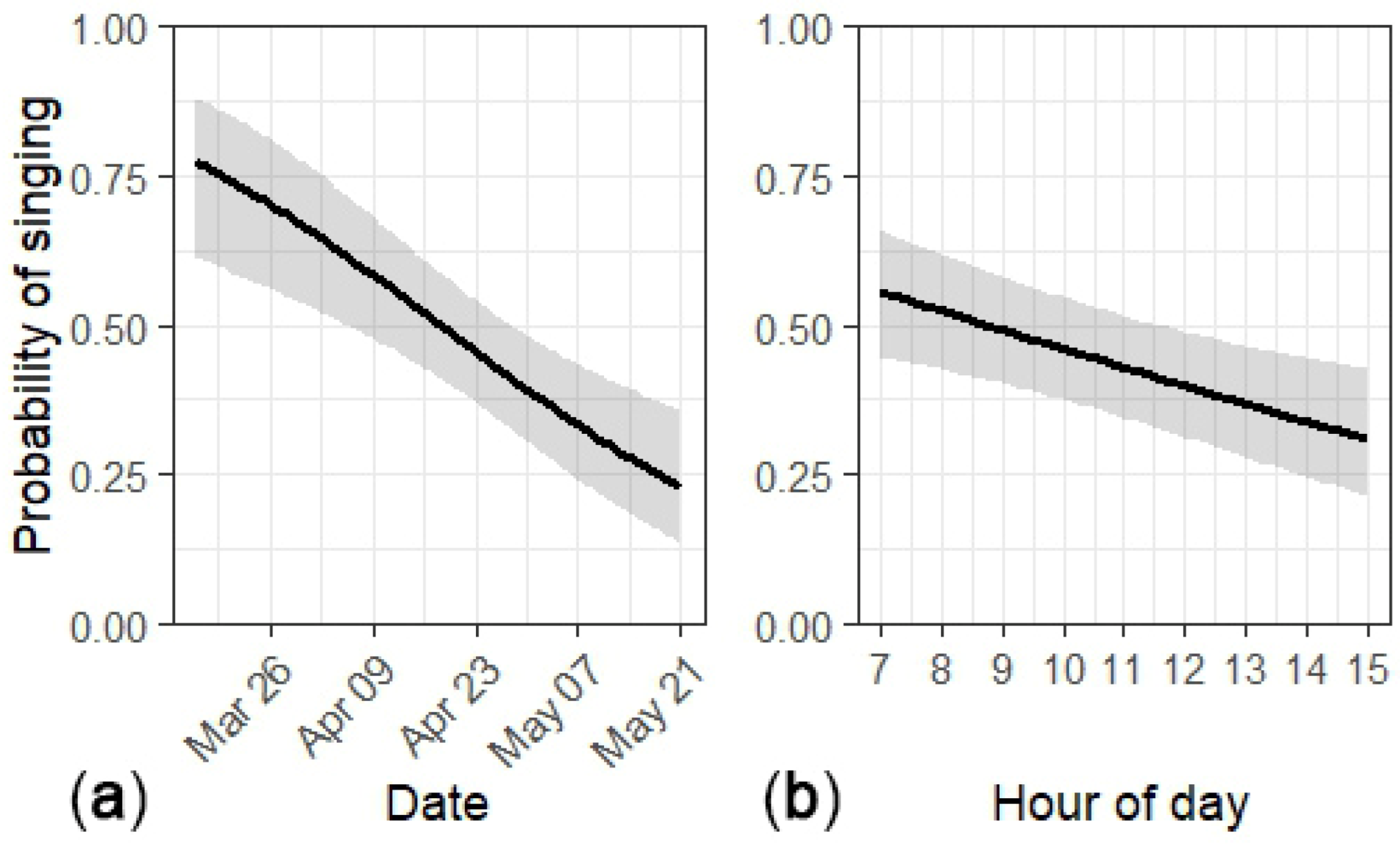

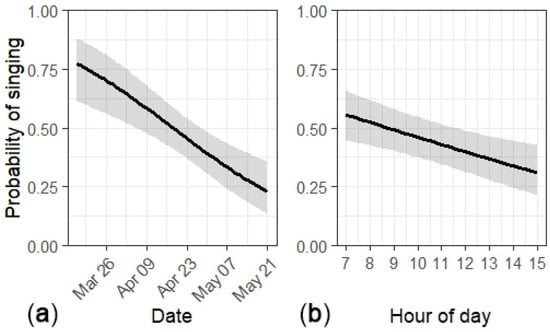

Availability was greater for unpaired vs. paired males, 0.82 (95% CI: 0.64–0.92) vs. 0.29 (95% CI: 0.19–0.42), and when conspecifics were singing vs. when none were detected, 0.61 (95% CI: 0.46–0.75) vs. 0.54 (95% CI: 0.39–0.68). Predicted availability strongly declined throughout the season and moderately declined throughout the day (Figure 1). The overall per-minute availability was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.37–0.54); the raw mean was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.43–0.46).

Figure 1.

Per-minute availability (detection of singing) of male Golden-cheeked Warblers decreased as a (a) function of day of year and (b) hour of day in Balcones Canyonlands Preserve, Austin, Texas, 2010–2011. The black line is the mean predicted availability and the gray area represents the 95% confidence intervals.

In the subset with breeding stage classified (n = 60 males, 124 surveys, 6167 min), the availability differed among stages and decreased with day of year, but not with hour of day, female or fledgling presence, territory density, or year (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of predictors on per-minute availability of male Golden-cheeked Warblers from the breeding stage subset.

Availability was highest when the males were unpaired [0.81 (95% CI: 0.62–0.92)] and lower during nesting/parental stages (Table 3).

Table 3.

Model-averaged means (probability of singing per minute) by breeding stage.

In the subset with age classified (n = 48 males, 108 surveys, 5486 min), the availability was only affected by breeding stage and day of year (Table 4). Availability was similar for ASY [0.47 (95% CI: 0.34–0.61)] and SY [0.44 (95% CI: 0.29–0.60)] males, and did not differ by hour of day or year.

Table 4.

Effects of predictors on per-minute availability of male Golden-cheeked Warblers from the age subset.

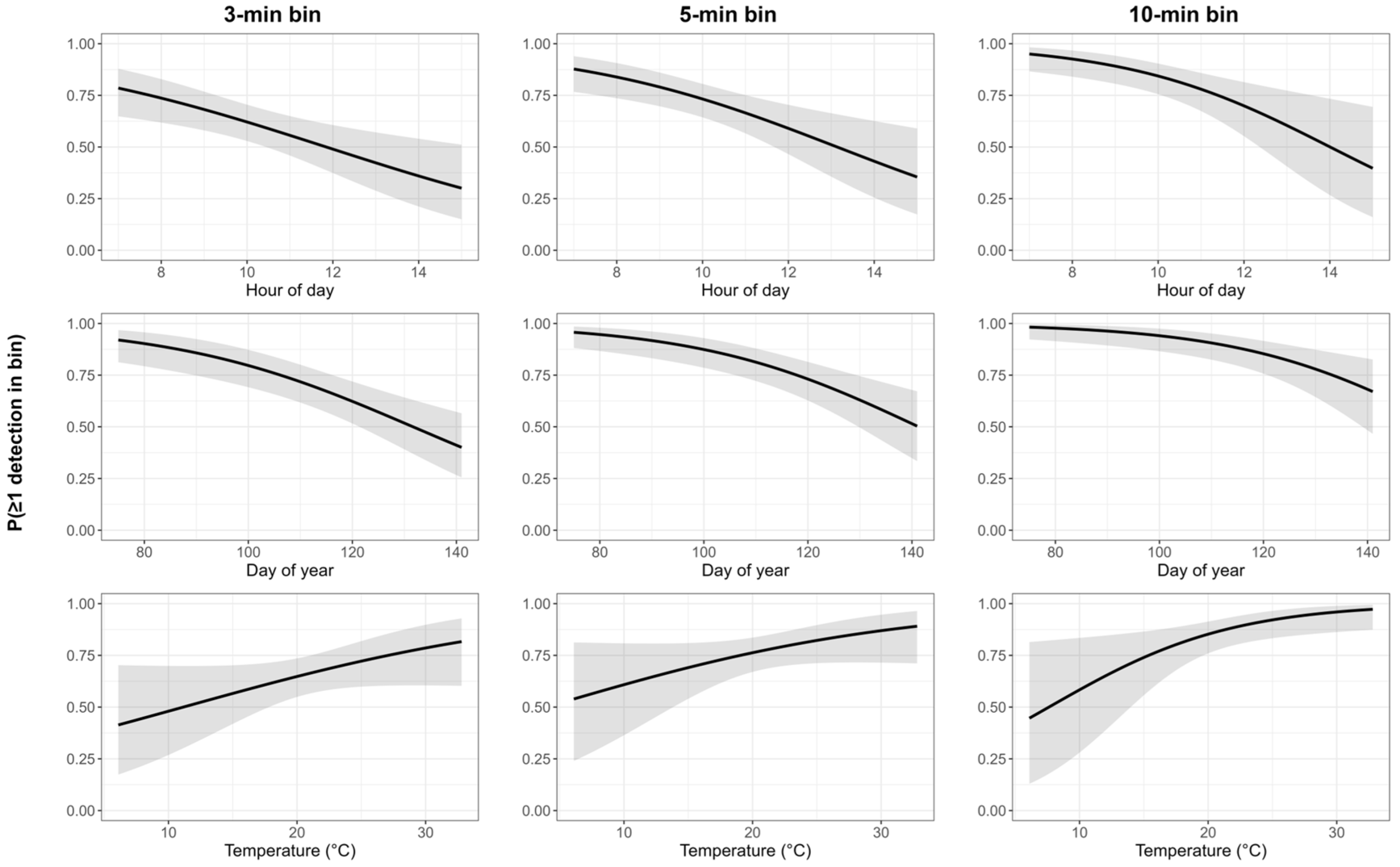

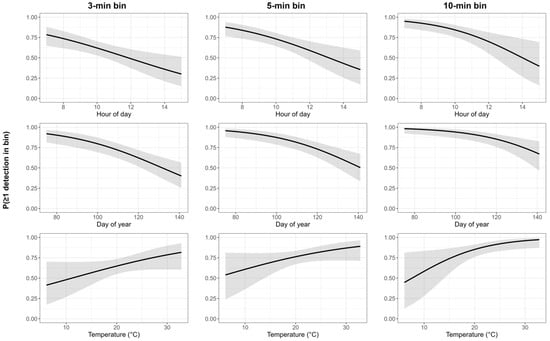

Sample sizes were 2053, 1263, and 595 bins for 3, 5, and 10 min, respectively (131 surveys; 60 males). Availability decreased by day of year and hour of day across all bins, whereas temperature showed a modest increase, and was clearest at 10 min bins (Table 5; Figure 2). The model-averaged availability was 0.61 (95% CI: 0.52–0.70), 0.72 (95% CI: 0.63–0.79), and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.74–0.90) for the 3, 5, and 10 min bins, respectively.

Table 5.

Effects of predictors on discrete availability (≥1 song detected) of male Golden-cheeked Warblers across 3, 5, and 10 min sampling windows.

Figure 2.

Availability (measured as ≥one song detected) within 3, 5, and 10 min bins as additive partial effects of hour of day, day of year, and temperature. The black line is the mean predicted availability and the gray area represents the 95% confidence intervals.

3.2. Song Structure

Using minute-level detections from all surveys (n = 138 surveys, including five surveys with unknown pairing status), a Wald–Wolfowitz runs test showed that the sequences of singing vs. silence were non-random in most surveys (107/138 with p < 0.05; median p < 0.001), and were consistent with singing in bouts [35]. Treating the first and last run in each survey as censored, Kaplan–Meier estimators produced a restricted mean bout length (±SE) of 9.55 ± 0.65 min for singing and of 13.23 ± 1.55 min for silent bouts. Singing bout length differed by pairing status (χ2 = 24.10, df = 1, p < 0.001): unpaired males averaged 19.51 ± 2.24 min, whereas paired males averaged 8.73 ± 0.73 min.

3.3. Song Rates and Song Types

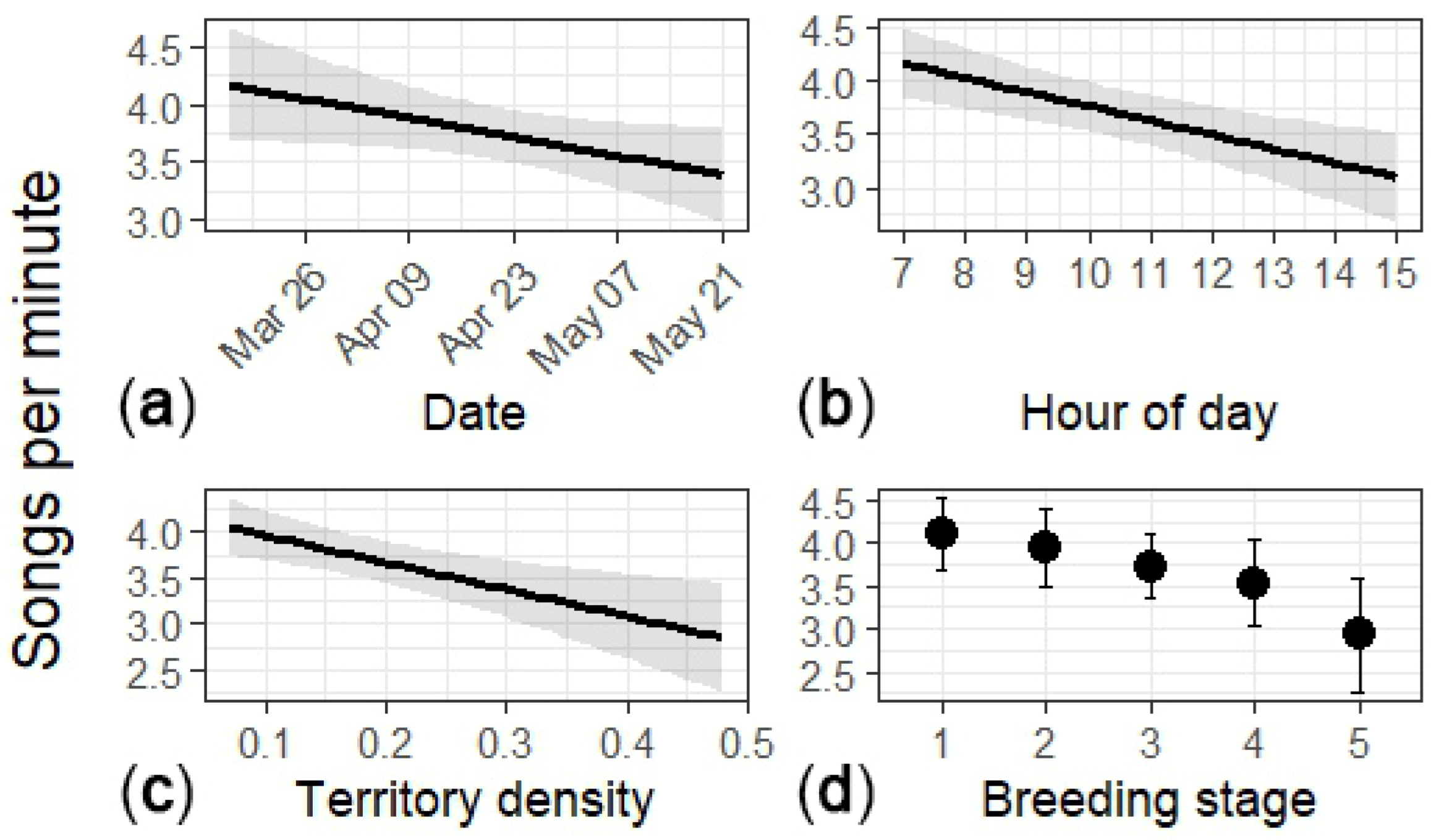

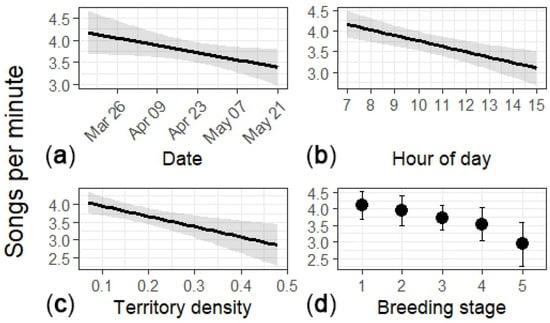

I collected song-rate samples from 55 males (n = 93 surveys; 1830 min). The overall song rate was 3.82 songs·min−1 (95% CI: 3.57–4.08). The predicted song rate declined through the season and over the course of the day, and with territory density (Table 6; Figure 3). The rates did not differ between paired and unpaired males (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effects of predictors on song rate (songs per minute) of male Golden-cheeked Warblers.

Figure 3.

Song rate as a function of (a) day of year, (b) hour of day, (c) territory density, and (d) breeding stage. Breeding stage: (1) unpaired, (2) male paired but pre-nesting, (3) male paired and nest was in the egg stage, (4) male paired and feeding nestlings, and (5) male paired and feeding fledglings. Results for (a–c) are from the full dataset, and (d) is from the breeding stage subset. The plots show mean (black line or circle) and associated 95% confidence intervals (gray area or error bars).

In the subset with breeding stage (n = 51 males; 86 surveys; 1739 min), stage showed a marginal negative trend overall (Figure 3). Song rates declined with hour of day and territory density (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effects of predictors on song rate (songs per minute) of male Golden-cheeked Warblers from the breeding stage subset.

I recorded song types for a subsample of total observations (n = 55 males; 93 surveys; 1830 min). After excluding minutes with multiple song types recorded, 1786 min remained for analysis. The probability of singing Type A songs was affected by the pairing status, day of year, and hour of day, but not by territory density (Table 8).

Table 8.

Effects of predictors on song type (probability of singing Type A song) of male Golden-cheeked Warblers.

Within minutes classified as Type A or B, song rate varied by song type, day of year, hour of day, and territory density, with weak support for an effect of pairing status (Table 9). Type B songs were delivered at higher rates (4.24 songs·min−1, 95% CI: 3.95–4.54) than Type A songs (3.69 songs·min−1, 95% CI: 3.44–3.93), and predicted rates declined across the season, later in the day, and in higher-density territories.

Table 9.

Effects of predictors on song rate (songs per minute) for Type A and B songs of male Golden-cheeked Warblers.

4. Discussion

This study provides an estimate of the availability of singing Golden-cheeked Warblers for individual minutes and for intervals corresponding to commonly used point count survey lengths. The availability based on singing was significantly less than one and may need to be considered in conclusions regarding warbler density or abundance. Because warblers sing in bouts, often exceeding 10 min of silence in between songs, observers would fail to detect some portion of males present but not available for detection in typical auditory surveys. Reducing the survey length to a shorter duration, such as the 2 min survey proposed by Peak (2011) [36] or 3 min survey used in Mueller et al. (2022) [23] and Sesnie et al. (2016) [37], would result in even less of the breeding population being available for detection. This is especially problematic for large-scale studies where disparities in pairing success due to differences in habitat quality could bias the data in favor of unpaired males who sing more frequently. Shorter surveys also reduce the number of observations when availability is incomplete, which will reduce precision. Longer surveys provide more opportunity to detect paired males, resulting in higher availability [13,38], but will also result in less time to complete additional surveys in a day and may be incompatible with other methods to estimate detection such as distance sampling, which assumes birds do not move during survey periods. This study shows the trade-offs of shorter vs. longer surveys in the probability of a male singing within each window.

Pairing status had the strongest influence on singing behavior of male warblers. Several studies on singing behavior of wood warblers have demonstrated that paired males sing less than their unpaired cohorts [14,16,17,39,40,41,42]. My results are consistent with those reported for other wood warblers, including American Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla), who sang in 49% of 5 min intervals when paired versus 99% when unpaired [16], and Cerulean Warblers (Setophaga cerulea), who sang in 62% of 5 min intervals when paired and 97% when unpaired [17]. One study even proposed that pairing status could be quickly ascertained for American Redstarts within a point count survey using song rate [16]. Based on the range overlap of the song rates I observed, this does not seem like a reliable method to assess the pairing status of Golden-cheeked Warblers. Considering pairing success is generally high for this species, at least at sites where intensive monitoring is performed [43,44,45], the availability of populations may be much lower than one. Additionally, pairing success is not constant across years or sites and is often lower at low density sites [29,44], so this source of variation can lead to biased conclusions if not considered for studies involving many years or locations. Confounding this issue, abundance at low-quality sites may be overestimated due to a higher proportion of unpaired males singing at higher rates, and abundance at high-quality sites where almost all males are paired may be underestimated due to low availability. A previous study observed this when it compared the spot-mapped abundance of color-banded males with predicted abundance from N-mixture models [46]; the study also suggested that sites with a higher density would have higher individual song rates because the presence of neighboring singing males would induce territorial males to sing more often in defense of their territories or females, and these higher song rates would in turn lead to higher availability. Although availability was positively influenced by the singing behavior of conspecifics, I did not find support for territory density as affecting availability. Moreover, I found a trend that song rate actually declined with higher territory density, similar to Ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapillus) and Black-throated Blue Warblers (Setophaga caerulescens) [47]. Further investigation of the effects of territory size and density on singing behavior and song rates, and the implications for the monitoring of this species, is warranted.

Male singing behavior was influenced by the breeding stage they were in, but not necessarily by presence of females and dependent fledglings observed within the survey. Males were often silent or softly chipping while mate guarding and pair bonding (J. Reidy, personal observation). During this period, they are unlikely to be detected during an auditory survey. Because adults take approximately a month to arrive on the breeding grounds (J. Reidy, peronal observation), pairing takes place across a multiple-week period, which should be considered when designing surveys. Once males have fledglings, they spend much of their time engaged in feeding them and less time doing other activities, such as singing or defending territories. Males that are successful early in the season continue to sing and are often still located by song in their territory, especially those males with active subsequent nests (double broods), whereas males that are successful later in the season are often quiet post-fledgling, and can only be located through chip notes produced by themselves or their young. I did not record singing behavior in late May or June, but based on years of cumulative observations, singing drops off precipitously at this time as successful males quietly tend to their fledglings or prepare for migration and unsuccessful males give up for the season and often begin wandering outside of their territory, likely prospecting for future territories. While breeding stage is an important influence on singing behavior, it interacts with day of year: most paired males with dependent fledglings will continue singing through mid-to-late May, but even unpaired males will dramatically reduce or stop singing in June.

This measure of availability was computed by sampling across long time periods and included periods of tracking silent males; it was also completed across a larger temporal and seasonal window than most point count surveys are conducted under in order to demonstrate the effects of time, season, and weather on availability. As such, these results differ from a measure of availability determined within a point count survey, such as time-of-first-detection or time-removal approaches [7,26].

5. Conclusions

To approximate the within-season demographic and geographic closure, surveys should begin after the breeding population has arrived. Ninety-seven percent of returning banded males were resighted by the end of first week of April (J. Reidy, unpublished data), so point count surveys should not begin earlier than ~1 April. By mid- to late-May, intra-season dispersal is common (City of Austin, unpublished data). Additionally, the day of the year and the hour of the day influenced singing behavior, with availability generally declining throughout the breeding season; therefore, surveys should be discontinued by mid-May because of both the declining availability and the violations of population closure. The time of day was also a strong predictor of availability, with much more singing activity in the morning. Additionally, most surveys are conducted at minimum temperatures of 10 °C but I found that availability is generally higher at temperatures ≥ 20 °C. Cumulatively, these results provide guidelines for future surveys to be undertaken under generally the highest availability: the early weeks of April, the hours from post-sunrise through to 3–4 h post-sunrise, and when temperature is ≥20 °C. These narrow constraints limit the number of possible surveys a single observer can complete, however, and add a further complication, requiring many observers to complete surveys. Multiple surveys at a given point across the breeding season may be necessary to maximize the probability of detecting a territorial male and may have contributed to the higher predictive power of a distance model reported in Sesnie et al. (2016) [37]. Careful examination of designs and analytical techniques are warranted to provide context for past and future population estimates and habitat use of Golden-cheeked Warblers. Future research should determine if the availability estimated from data collected during a point count survey appropriately accounts for males present but not detected via song.

Funding

This research received no external funding but was permitted under guidance of the City of Austin Wildland Conservation Division.

Institutional Review Board statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study because it was observational. Banding and handling of Golden-cheeked Warblers was conducted as part of a separate monitoring program.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not archived but are available upon request from author.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the City of Austin Wildland Conservation Division for providing access to the sites and other logistical support and supporting independent research. F. R. Thompson III provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, I consulted ChatGPT version 5 for the purposes of editing R code and reviewing text of methods. I have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ralph, C.J.; Droege, S.; Sauer, J.R. Managing and monitoring birds using point counts: Standards and applications. In Monitoring Bird Populations by Point Counts; Ralph, C.J., Sauer, J.R., Droege, S., Eds.; General Technical Report PSW-GTR-149; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J.D.; Thomas, L.; Conn, P.B. Inferences about landbird abundance from count data: Recent advances and future directions. In Modeling Demographic Processes in Marked Populations; Thomson, D.L., Cooch, E.G., Conroy, M.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 201–235. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.H. Point counts of birds: What are we estimating? In Monitoring Bird Populations by Point Counts; Ralph, C.J., Sauer, J.R., Droege, S., Eds.; General Technical Report PSW-GTR-149; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.L. Toward reliable bird surveys: Accounting for individuals present but not detected. Auk 2002, 119, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.H.; McIntyre, C.L.; MacCluskie, M.C. Accounting for incomplete detection: What are we estimating and how might it affect long-term passerine monitoring programs. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 160, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thogmartin, W.E.; Howe, F.P.; James, F.C.; Johnson, D.H.; Reed, E.T.; Sauer, J.R.; Thompson, F.R., III. A review of the population estimation approach of the North American landbird conservation plan. Auk 2006, 123, 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, G.L.; Pollock, K.H.; Nichols, J.D.; Simons, T.R.; Hines, J.E.; Sauer, J.R. A removal model for estimating detection probabilities from point-count surveys. Auk 2002, 119, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pollock, K.H.; Nichols, J.D.; Simons, T.R.; Farnsworth, G.L.; Bailey, L.L.; Sauer, J.R. Large scale wildlife monitoring studies: Statistical methods for design and analysis. Environmetrics 2002, 13, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, S.T.; Anderson, D.R.; Burnham, K.P.; Laake, J.L.; Borchers, D.L.; Thomas, L. Introduction to Distance Sampling: Estimating Abundance of Biological Populations; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Royle, J.A. N-mixture models for estimating population size from spatially replicated counts. Ecology 2004, 85, 2200–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, J.D.; Hines, J.E.; Sauer, J.R.; Fallon, F.W.; Fallon, J.E.; Heglund, P.J. A double-observer approach for estimating detection probability and abundance from point counts. Auk 2000, 117, 393–408. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Farnsworth, G.L.; Nichols, J.D.; Sauer, J.R.; Fancy, S.G.; Pollock, K.H.; Shriner, S.A.; Simons, T.R. Statistical Approaches to the Analysis of Point Count Data: A Little Extra Information Can Go a Long Way; General Technical Report PSW-GTR-191; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 2005.

- Diefenbach, D.R.; Marshall, M.R.; Mattice, J.A.; Brauning, D.W. Incorporating availability for detection in estimates of bird abundance. Auk 2007, 124, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsinger, J.S. Use of two song categories by Golden-cheeked Warblers. Condor 2000, 102, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.A.; Lee, P.; Greene, G.C.; McCallum, D.A. Singing Rate and Detection Probability: An Example from the Least Bell’s Vireo (Vireo bellii pusillus); General Technical Report PSW-GTR-191; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 2005.

- Stacier, C.A.; Ingalls, V.; Sherry, T.W. Singing behavior varies with breeding status of American Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). Wilson J. Ornithol. 2006, 118, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, M.B.; Nyári, Á.S.; Papeş, M.; Benz, B.W. Song rates, mating status, and territory size of Cerulean Warblers in Missouri Ozark riparian forest. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2009, 121, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.M.; Bart, J. Reliability of singing bird surveys: Effects of song rate and nest attentiveness. Condor 1985, 87, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- BirdLife International. Setophaga chrysoparia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: E.T22721692A181039629. 2020. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22721692/181039629 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Golden-Cheeked Warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia) Recovery Plan; U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Groce, J.E.; Mathewson, H.A.; Morrison, M.L.; Wilkins, N. Scientific Evaluation for the 5-Year Status Review of the Golden-Cheeked Warbler; Institute of Renewable Natural Resources and the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson, H.A.; Groce, J.E.; McFarland, T.M.; Morrison, M.L.; Newman, J.C.; Snelgrove, R.T.; Collier, B.A.; Wilkins, R.N. Estimating breeding season abundance of Golden-cheeked Warblers in Texas, USA. J. Wildl. Manag. 2012, 76, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J.M.; Sesnie, S.E.; Lehnen, S.E.; Davis, H.T.; Giacomo, J.J.; Macey, J.N.; Long, A.M. Multi-scale species density model for conserving an endangered songbird. J. Wildl. Manag. 2022, 86, e22236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.W.; Weckerly, F.W.; Ott, J.R. Reliability of occupancy and binomial mixture models for estimating abundance of Golden-cheeked Warbler (Setophaga chrysoparia). Auk 2012, 129, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peak, R.G.; Thompson, F.R., III. Amount and type of forest cover and edge are important predictors of Golden-cheeked Warbler density. Condor 2013, 115, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, J.L.; Thompson, F.R., III; Amundson, C.; O’Donnell, L. Landscape and local effects on densities of an endangered wood-warbler in an urbanizing landscape. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, H.L.; Long, A.M.; Mathewson, H.A.; Morrison, M.L. Does age structure influence Golden-cheeked Warbler responses across areas of high and low density? West. N. Am. Nat. 2017, 77, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, L.; Farquhar, C.C.; Hunt, J.W.; Nesvacil, K.; Reidy, J.L.; Reiner, W., Jr.; Scalise, J.L.; Warren, C.C. Density influences accuracy of model-based estimates for a forest songbird. J. Field Ornithol. 2019, 90, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, J.F.; Poteet, M.F.; Symstad, A.J.; Musgrove, M.; Long, A.J.; Mahler, B.J.; Norton, P.A. Historical and Projected Climate (1901–2050) and Hydrologic Response of Karst Aquifers, and Species Vulnerability in South-Central Texas and Western South Dakota; U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2014–5089; U.S. Department of Interior, Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reidy, J.L.; Thompson, F.R., III; Connette, G.M.; O’Donnell, L. Demographic rates of Golden-cheeked Warblers in an urbanizing woodland preserve. Ornithol. Appl. 2018, 120, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peak, R.G.; Lusk, D.J. Alula characteristics as indicators of Golden-cheeked Warbler age. N. Am. Bird Bander 2010, 34, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Schielzeth, H. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B.M.; Brooks, M.E.; Clark, C.J.; Geange, S.W.; Poulsen, J.R.; Stevens, M.H.H.; White, J.-S. Generalized linear mixed models: A practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, X.A.; Donaldson, L.; Correa-Cano, M.E.; Evans, J.; Fisher, D.N.; Goodwin, C.E.D.; Robinson, B.S.; Hodgson, D.J.; Inger, R. A brief introduction to mixed effects modelling and multi-model inference in ecology. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenowitz, E.A.; Margoliash, D.; Nordeen, K.W. An introduction to birdsong and the avian song system. J. Neurobiol. 1997, 33, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peak, R.G. A field test of the distance sampling method using Golden-cheeked Warblers. J. Field Ornithol. 2011, 82, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesnie, S.E.; Mueller, J.M.; Lehnen, S.E.; Rowin, S.M.; Reidy, J.L.; Thompson, F.R., III. Airborne laser altimetry and multispectral imagery for modeling golden-cheeked warbler (Setophaga chrysoparia) density. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sólymos, P.; Matsuoka, S.M.; Bayne, E.M.; Lele, S.R.; Fontaine, P.; Cumming, S.G.; Stralberg, D.; Schmiegelow, F.K.A.; Song, S.J. Calibrating indices of avian density from non-standardized survey data: Making the most of a messy situation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.P.; Probst, J.R.; Rakstad, D. Effect of mating status and time of day on Kirtland’s Warbler song rates. Condor 1986, 88, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.P.; Wenny, D.G. Song output as a population estimator: Effect of male pairing status. J. Field Ornithol. 1993, 64, 316–322. [Google Scholar]

- Stacier, C.A. Honest advertisement of pairing status: Evidence from a tropical resident wood-warbler. Anim. Behav. 1996, 51, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKillip, S.R.; Islam, K. Vocalization attributes of Cerulean Warbler song and pairing status. Wilson J. Ornitho. 2009, 121, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peak, R.G. Golden-cheeked warbler demography on Fort Hood, Texas, 2010. In Endangered Species Monitoring and Management at Fort Hood, Texas: 2010 Annual Report; The Nature Conservancy, Fort Hood Project: Fort Hood, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy, J.L.; O’Donnell, L.; Thompson, F.R., III. Evaluation of a reproductive index for estimating songbird productivity: Case study of the Golden-cheeked Warbler. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2015, 39, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, J.N.; Collins, K.R.; Gamble, M.D.; Grigsby, N.; Raginski, N.M.; Kunberger, J.M.; Finn, D.S.; Colón, M.R.; Carrusco, S.; Long, A.M. Examining the potential impacts of geolocators on a small migratory songbird, the Golden-cheeked Warbler: Results from a multi-year study. Avian Conserv. Ecol. 2025, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.C.; Veech, J.A.; Weckerly, F.W.; O’Donnell, L.; Ott, J.R. Detection heterogeneity and abundance estimation in populations of Golden-cheeked Warblers (Setophaga chrysoparia). Auk 2013, 130, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, J.P. Spatial and Temporal Variation in Singing Rates of Two Forest Songbirds, the Ovenbird and the Black-Throated Blue Warbler: Implications for Aural Counts of Songbirds. Master’s Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).