Simple Summary

Corvids often avoid objects they consider risky when searching for food, but it is not well understood which object features make them more cautious. In this study, we observed how wild-caught Large-billed Crows (Corvus macrorhynchos) reacted to five different visual conditions near their food: no object, a cardboard box, an immobile owl decoy, a continuous-motion owl decoy, and an owl decoy that moved suddenly when the birds approached. We recorded how long it took the crows to start feeding, how often they landed and how long they remained near the food, and how much food they ate. All objects caused them to hesitate before feeding, but the owl decoy that moved suddenly led to the strongest avoidance. These results suggest that they are influenced not only by the presence of an object but also by how it moves and/or whether it appears biological. Our findings help explain how crows judge potential risks while foraging and highlight the importance of object complexity in shaping their avoidance behaviour.

Abstract

Corvids exhibit avoidance behaviour when foraging in the presence of potentially risky stimuli, yet it remains unclear how stimulus characteristics influence the strength of such responses. In this paper, we present wild-caught Large-billed Crows (Corvus macrorhynchos) with five conditions: no visual stimulus, a cardboard box (non-biological, stationary), an immobile owl decoy (biological, stationary), a continuous-motion owl decoy (biological, moving), and a sensor-activated-motion owl decoy (biological, moving, and sudden). Avoidance was quantified using feeding latency, landing frequency, total time spent in the feeding area, and food consumption. Compared with the condition with no visual stimulus, the presence of any visual stimulus elicited increased latency, indicating that crows detect and respond to objects near food. Among the four objects, the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy produced stronger avoidance responses of the crows than the non-biological and stationary object (cardboard box). This indicates that they evaluate not only the presence of an object but also its motion characteristics and/or perceived biological cues when adjusting their foraging behaviour. Although sample size and individual variation impose limitations, these findings suggest that both the presence of visual stimuli and/or the complexity of their appearance play key roles in shaping avoidance behaviour in corvids.

1. Introduction

For wild birds, effective foraging requires balancing energetic benefits against multiple sources of risk, including predators, competitors, and human activity [1,2]. Behavioural responses to predation can be broadly categorized into escape, which occurs after threat detection and has been widely quantified using metrics such as flight initiation distance (FID), and avoidance, which proactively reduces the likelihood of encountering danger by shaping habitat use and movement prior to direct encounters [3].

Avoidance becomes especially important when threats are ambiguous rather than overt [4]. In such situations, birds evaluate unfamiliar objects, novel stimuli, or anthropogenic structures without definitive information about risk. These conditions can suppress patch use or delay feeding even in the absence of explicit evidence of predation or disturbance, indicating that uncertainty itself functions as an ecological cost that influences movement and habitat selection [5,6]. While escape responses are well documented, avoidance has received comparatively less empirical attention, despite its central role in determining whether individuals utilize a foraging site in the first place [7]. Avoidance is often expressed as the absence of a behaviour—such as delayed approach, reduced patch use, or complete non-entry into a site—making it inherently difficult to observe, and to distinguish from decisions driven by energetic optimization or social interactions [8,9,10]. This lack of clear behavioural metrics contrasts sharply with standardized measures of escape, highlighting a critical knowledge gap in risk-related decision making.

Corvids, including species in the genus Corvus, may be particularly responsive to neophobia and ambiguous stimuli. Comparative studies demonstrate that corvids frequently avoid novel objects or unfamiliar structures near feeding sites even in the absence of overt threats, suggesting reliance on avoidance when evaluating uncertain conditions [11,12,13]. Experimental work with captive ravens further shows that novelty affects item selection, as individuals reduce use of unfamiliar or large food items when potential risks are unclear [14]. These studies have primarily focused on relatively simple forms of novelty—such as unfamiliar shapes, colours, or small objects. Western Jackdaws (Coloeus monedula) modify their foraging behaviour in response to subtle visual cues, such as the direction of human gaze, suggesting that even small variations in visual information can influence avoidance responses [15]. Similarly, field observations suggest that more complex decoys—such as moving or threat-like appearance—are effective in reducing crop damage by corvids, pointing to a potential role of stimulus complexity in shaping avoidance behaviour [16]. However, despite strong evidence that corvids avoid novel objects, it remains unclear whether avoidance strength scales with the "complexity"—for example, from neutral objects to static and moving bird decoys.

Observations and experiments under wild conditions allow behavioural responses to be assessed in a more natural context, but it is difficult to control for disturbance such as the presence of humans or predators [17,18] and weather fluctuations [19,20]. Therefore, experiments under captivity can be a useful approach for quantifying animal behaviour. To test whether corvids modulate avoidance in response to stimuli differing in ecological relevance and perceived risk, we presented a gradient of static and dynamic objects to wild-caught Large-billed Crows (Corvus macrorhynchos) in captivity. Four stimulus types representing four distinct stages differing in appearance and movement were employed: (i) a cardboard box (non-biological, stationary), (ii) an immobile owl decoy (biological, stationary), (iii) a continuous-motion owl decoy (biological, moving), and (iv) a sensor-activated-motion owl decoy (biological, moving, and sudden). We quantified avoidance in the crows using four metrics: (A) feeding latency, measured as the delay prior to initiating feeding; (B) patch-use decisions, including landing frequency and (C) duration within the feeding area; and (D) total food consumption. We predicted that all stimuli would induce initial hesitation due to novelty [13]. Furthermore, we expected that Large-billed Crows would differentiate between non-threatening and potentially threatening stimuli [21], with avoidance responses scaling with stimulus complexity—such that predator-like or dynamic cues would result in longer feeding latencies, fewer landings, shorter residency time, and lower food consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Subjects

In October 2024, 22 wild Large-billed Crows (sex unknown) were captured using a box trap (3.5 m × 8.0 m × 2.5 m) in Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. The birds were transported by vehicle to the Akagi Testing Center of the Central Research Institute of the Electric Power Industry (Maebashi, Gunma Prefecture), approximately 165 km from the capture site, on the same day they were trapped. Each individual was placed in a separate plastic container with air holes to ensure adequate ventilation. During transport, the temperature inside the vehicle was maintained at approximately 25 °C by air conditioning.

Mouth colouration is a reliable indicator for distinguishing fledglings from adults in Large-billed Crow. Nestlings exhibit entirely pink or red mouths, which gradually darken to black within 8–12 months [22]. Because none of the captured individuals had fully black mouths and they were trapped during the post-breeding season, all were classified as immature.

Each bird was fitted with a numbered metal leg ring for identification. The birds were housed together in an outdoor aviary (6 m × 6 m × 2.5 m) constructed from steel pipe and wire mesh, with a removable roof to maintain exposure to natural light and ambient temperature. Located more than 1 km from the Akagi Testing Center office, the aviary was rarely accessed by anyone other than caretakers and researchers. The crows were provided ad libitum access to perches, drinking water, and nutritionally complete dog food (Vita One, Nippon Pet Food), for which this species shows a strong preference [23]. All individuals were acclimated to captivity for 25 ± 7 days (mean ± SD) days prior to experimentation.

Trapping was conducted under permits issued by Nagaoka City, Niigata Prefecture (No. 10-1, 10-2, 10-3). The birds were released into the wild at the original capture site after the experiments.

2.2. Testing Cage and Experimental Trial

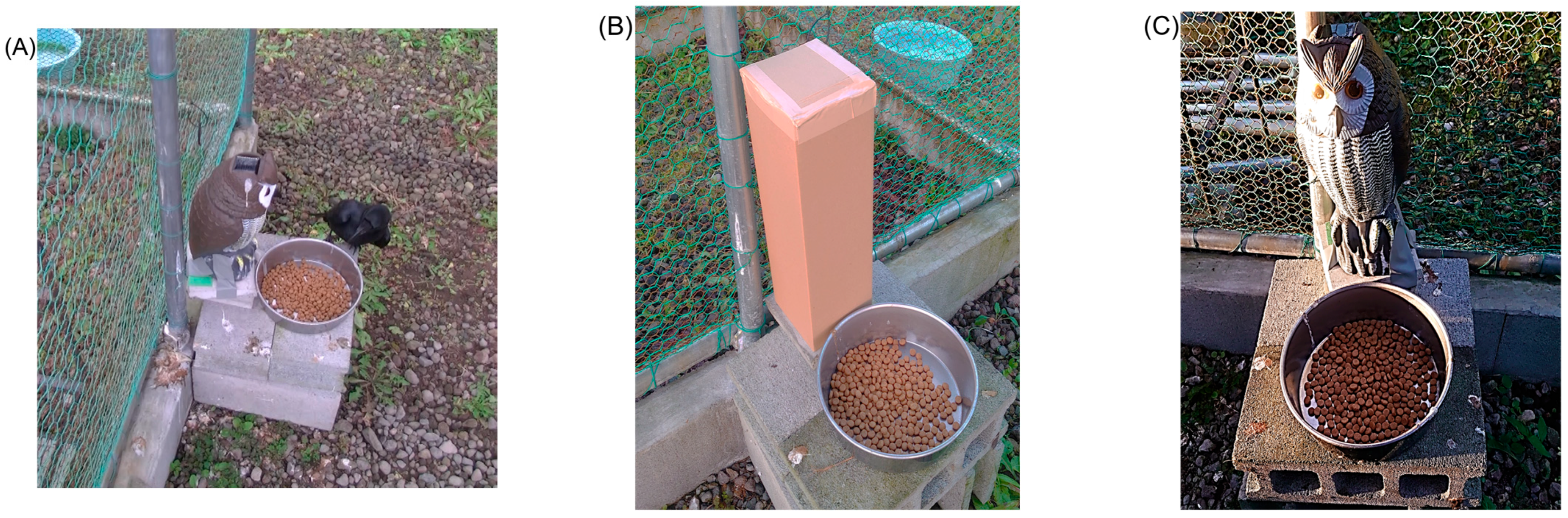

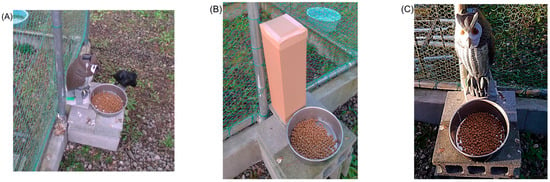

Experiments were conducted from October to November 2024 in an outdoor testing cage at the Akagi Testing Center, under natural light and ambient temperature conditions [23]. Across experimental days, the mean ambient temperature was 13.1 ± 4.1 °C and the mean relative humidity was 76.8 ± 14.4% (Table S1). The outdoor testing cage was U-shaped (4 m × 6 m × 2.5 m), enclosed with 16 mm hexagonal wire mesh, and equipped with perches. It consisted of two end compartments (each 2 m × 4 m × 2.5 m) connected by a central corridor (2 m × 2 m × 2.5 m). One compartment was designated the feeding area and housed concrete blocks supporting a feeding dish (Figure 1A). A round water dish was also placed inside the cage to provide ad libitum access to drinking water throughout the trials.

Figure 1.

(A) Large-billed Crow (C. macrorhynchos) foraging during the experiment with immobile owl decoy, (B) cardboard box (14 cm × 15 cm, 43 cm high), and (C) owl decoy (18 cm × 20 cm, 40 cm high).

To monitor crow behaviour, two video cameras (HDR-CX7, SONY, Tokyo, Japan; GZ-HM880-B, JVC, Yokohama, Japan) were installed inside the cage (Figure S1). As visual stimuli, we used either a cardboard box (14 cm × 15 cm × 43 cm high, Figure 1B) or a modified commercial owl decoy (KJ-125, Kojima Co., Ltd., Sanjo, Japan; 18 cm × 20 cm × 40 cm, Figure 1C). Although owls are carnivorous predators, and their morphology elicits wary behaviour in prey species, in Japan, owls primarily prey on voles and mice, and there is no evidence that crows are among their typical prey [24,25]. Thus, in this study, the owl decoys were used simply as biological visual stimuli. The owl decoy originally featured two motion patterns: immobile and sensor-activated head movement triggered by infrared detection (range: ~1–1.2 m; angle: ~90° horizontal). We added a third motion pattern, continuous head-shaking, referred to as continuous motion. The sound pressure levels (SPLs, Z-weighted) generated by the movement of the decoy and by the camera were measured using a digital sound level metre (NL62A, RION Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and were confirmed to be below 35 dB.

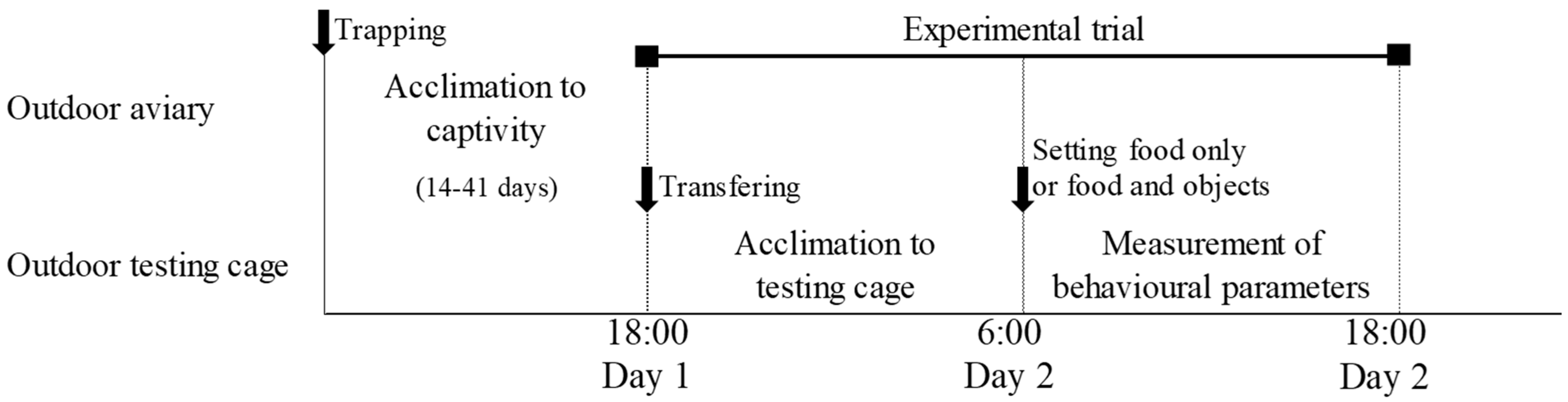

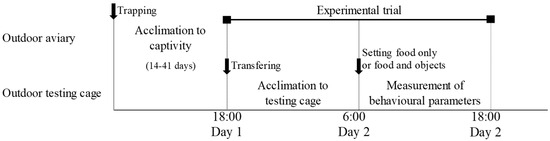

The 22 birds were randomly assigned to five groups: no visual stimulus (n = 6), cardboard box (n = 4), immobile owl decoy (n = 4), continuous-motion owl decoy (n = 4), and sensor-activated-motion owl decoy (n = 4). Each trial lasted 24 h, from 18:00 on day 1 to 18:00 on day 2, and involved a single individual (Figure 2). A bird was captured in the aviary using a hand net and then placed into a ventilated plastic container. The bird was transported from the aviary to the testing cage at 18:00, and no food was provided until 6:00 the following morning. At that point, the experimental setup began: the bird was placed in a cotton bird bag while the stimulus (cardboard box or owl decoy) was positioned approximately 5 cm in front of a food dish (27 cm in diameter, 7.3 cm high) containing 100 g of dog food.

Figure 2.

Timeline of the experimental procedure from trapping to behavioural testing. After individuals were captured in the field, they were housed in the aviary for an acclimation period before the trials. Each bird was then transferred to the test cage, where behavioural responses to the treatments were recorded over a 12 h experimental session.

Then, to minimise handling effects, the bird was transferred to a cardboard box fitted with a black curtain before the experimenter exited the cage. The start time of the trial was defined as the moment the bird exited the cardboard box, as recorded by one of the cameras (Video S1). Trials were terminated at 18:00 on the second day, and all individuals were promptly returned to the outdoor aviary. The remaining food was weighed at the end of each trial using an electric balance (±1 g), and the amount of food consumed (food amount) was calculated by subtracting this value from the initial 100 g provided. Each bird was tested only once to avoid habituation to the stimuli [26]. To account for potential environmental effects, all experiments were conducted on rain-free days with wind speeds below 5 m/s.

2.3. Data Analysis

To obtain behavioural parameters, video recordings from each experimental trial were analysed over a 12 h period (Video S2A–E). The feeding area was defined as the entire area on the concrete blocks, including the feeding dish. From these recordings, we extracted three behavioural parameters, each reflecting a different aspect of risk perception and foraging behaviour:

- 1.

- Latency (min): Defined as the duration between the bird’s emergence from the curtained cardboard box and its first foraging event at the feeding area. Longer latencies indicate hesitation or increased wariness toward novel objects or potentially threatening stimuli [13]. For individuals that did not forage during the trial, a latency time of 720 min was assigned.

- 2.

- Number of landings (times): The total number of distinct landings in the feeding area during the observation period. Reduced visit frequency is commonly observed in birds foraging under perceived predation risk or in the presence of food competitors [1].

- 3.

- Total time spent in the feeding area (min): The cumulative time the bird spent within the feeding area, calculated from each landing until take-off and summed across the entire trial. Shorter residency times are typically associated with increased wariness or perceived danger [27].

All analyses were performed in R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [28]. Generalised linear models (GLMs) were used to evaluate the effects of test condition (i.e., no visual stimulus, cardboard box, immobile owl decoy, continuous-motion owl decoy, sensor-activated-motion owl decoy) on each behavioural parameter and the amount of food consumed. A GLM with a gamma error distribution and log link function in the R package “stats” [28] was applied to the latency, while a GLM with a negative binomial distribution and log link function in the R package “MASS” [29] was used for the number of landings. The total time spent in the feeding area and the amount of food consumed were analysed using a GLM with a Gaussian distribution and an identity link function in the R package “stats”. Significance of model terms was assessed using Wald chi-squared tests in the R package “car” [30]. To test for differences in each parameter among test conditions, we used post hoc Tukey’s highly significant difference (HSD) tests for pairwise comparisons in the R package “multcomp” [31].

All values are reported as means ± SD. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

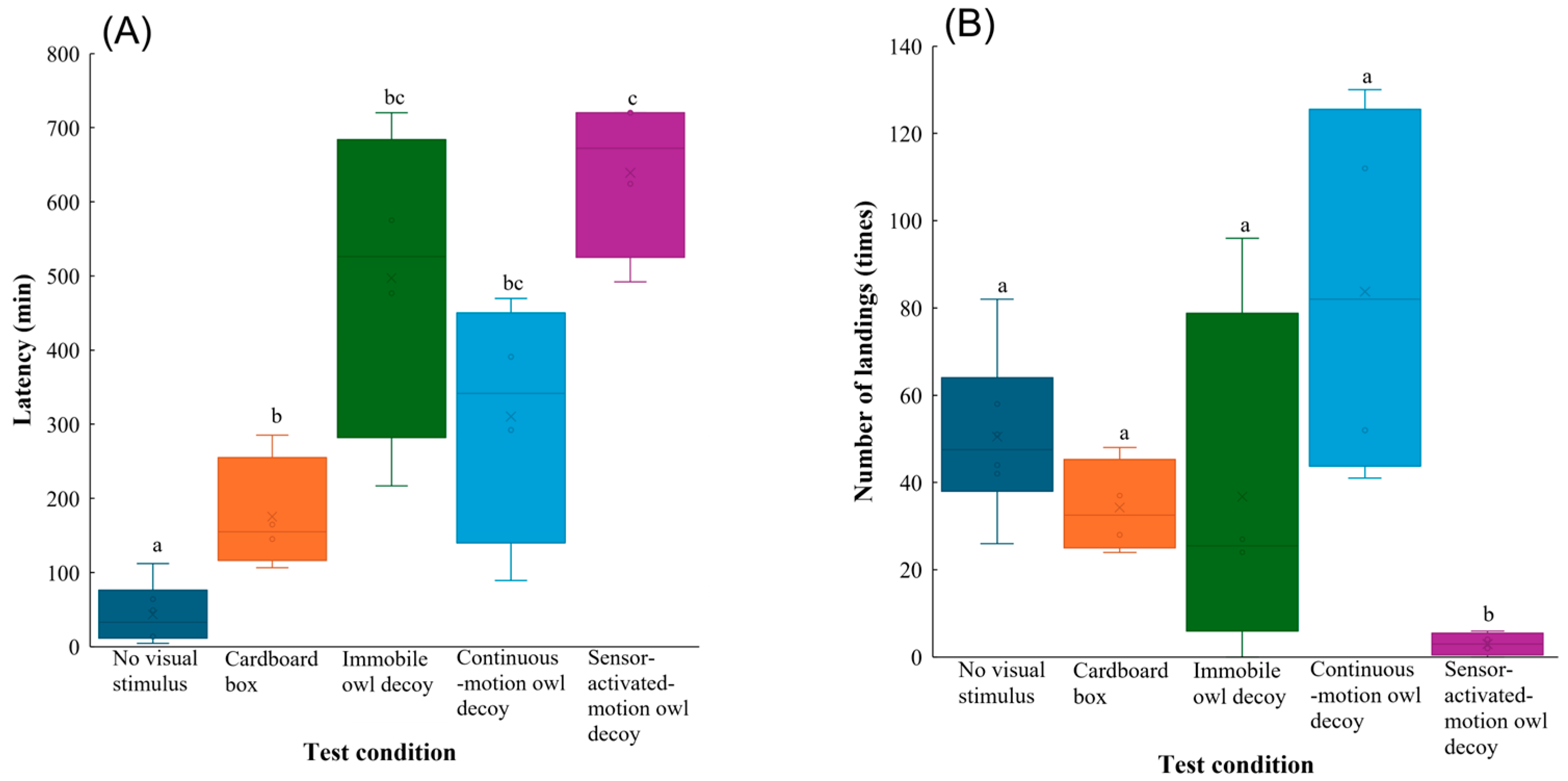

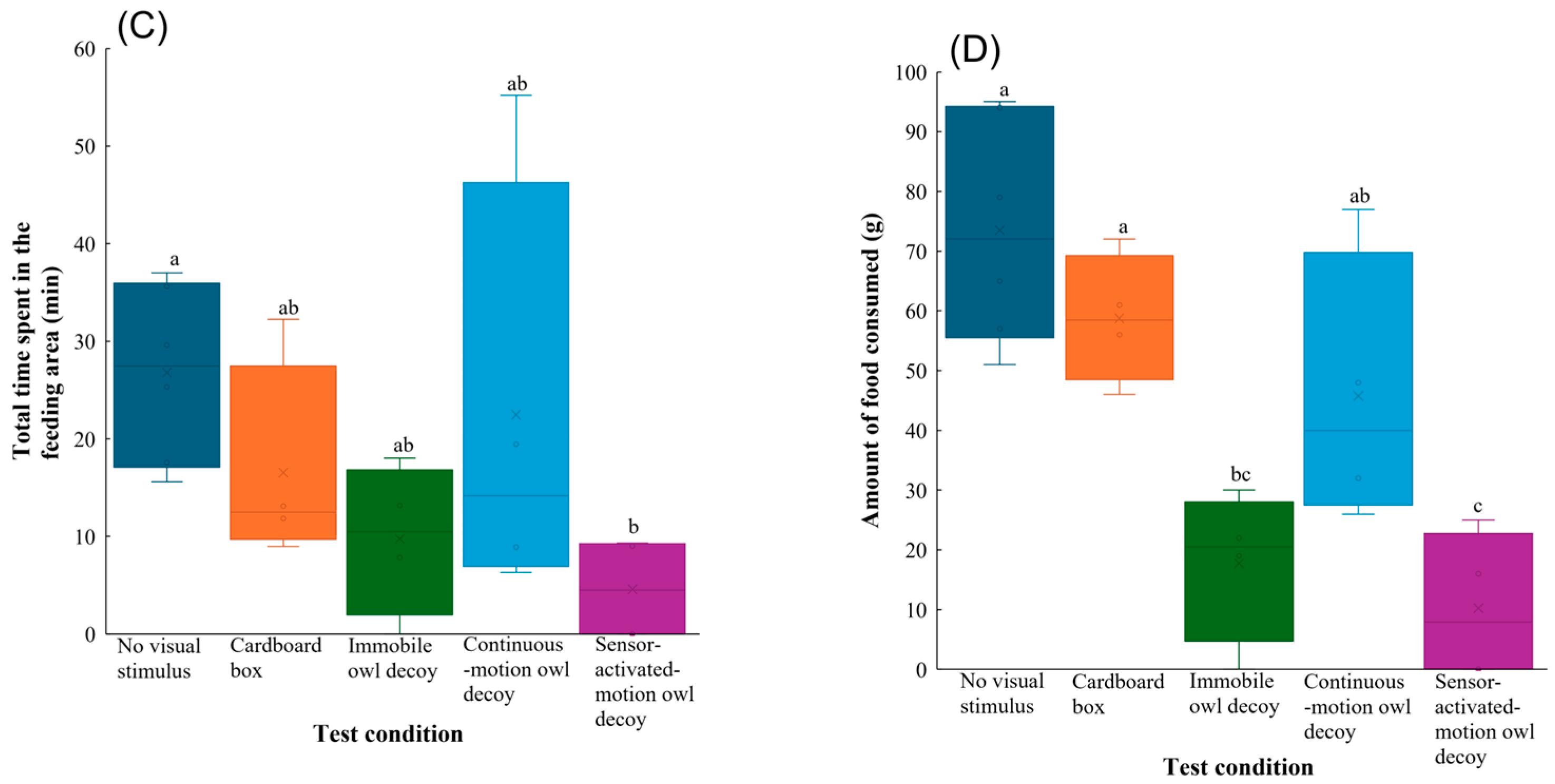

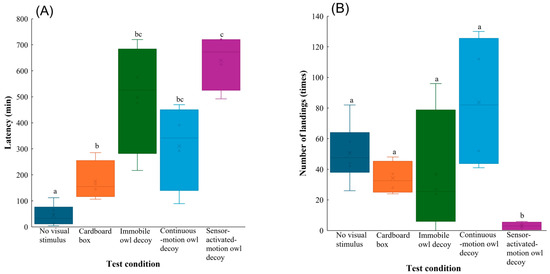

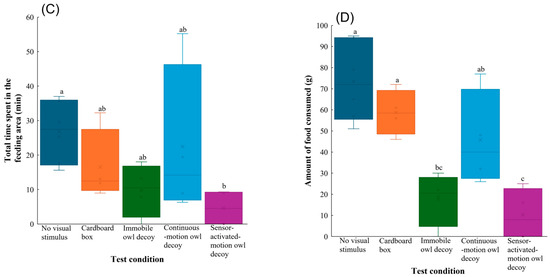

All behavioural parameters differed significantly among the test conditions (Table 1). According to varying results from the post hoc procedure (Table S2), the latency was shortest in the group with no visual stimulus and significantly longer in the other groups (vs. cardboard box: z = 3.5, p = 0.0040, vs. immobile owl decoy: z = 6.1, p < 0.001, vs. continuous-motion owl decoy: z = 5.0, p < 0.001, vs. sensor-activated-motion owl decoy: z = 6.8, p < 0.001). In addition, the latency in the group with the sensor-activated motion owl decoy was longer than that in the group with the cardboard box (z = 3.0, p = 0.024) (Figure 3A).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD) and results of the general linear models analysing the variation in latency, number of landings, total time spent in the feeding area, and the amount of food consumed.

Figure 3.

Behavioural responses of Large-billed Crows to no visual stimulus, a cardboard box, and owl decoys: (A) latency, (B) number of landings, (C) total time spent in the feeding area, and (D) amount of food consumed during the experimental trials. Whiskers represent minimum and maximum values, and boxes represent the 25–75th percentiles. Cross marks represent mean values. Letters indicate a significant pairwise difference based on Tukey’s highly significant difference post hoc test (different letters denote significant differences at p < 0.05; shared letters denote no significant difference).

The number of landings in the group with the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy was lowest, which significantly differed to those in the other test conditions (vs. no visual stimulus: z = −5.6, p < 0.001; vs. cardboard box: z = −4.5, p < 0.001; vs. immobile owl decoy: z = −4.7, p < 0.001; vs. continuous-motion owl decoy: z = −6.3, p < 0.001) (Figure 3B). Post hoc comparisons also showed that the group with the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy spent significantly less total time in the feeding area than that with no visual stimulus (z = −2.8, p = 0.038) (Figure 3C).

The amount of food consumed also significantly differed among test conditions (Table 1). Compared to when no visual stimulus (z = −5.2, p < 0.001) or cardboard box (z = −3.5, p = 0.0039) was present, the Large-billed Crows consumed significantly less food when the immobile owl decoy was deployed. Furthermore, the sensor-activated-motion decoy significantly reduced the food intake of the Large-billed Crows compared to no visual stimulus (z = −5.9, p < 0.001), the cardboard box (z = −4.2, p < 0.001), and continuous-motion owl decoy (z = −3.0, p = 0.020) (Figure 3D).

4. Discussion

We investigated whether judgements of an object’s biological nature might influence avoidance decision making in Large-billed Crows as a potential threat. As expected, our results showed that Large-billed Crows in captivity increased their latency in response not only to biological objects but also to non-biological ones. Corvids are generally highly neophobic, often displaying delayed food acquisition and heightened wariness in the presence of novel, non-biological objects [13]. For example, Torresian Crows (C. orru) [11], Eurasian Magpies (Pica pica), and Common Ravens (C. corax) [5] have shown increased latency to approach food when unfamiliar items such as pipe cleaners or shiny metal teaspoons were present—consistent with the response to the cardboard box in our study. Notably, Torresian crows also exhibited longer latency when dead twigs, common in their habitat, were placed near food; however, these twigs did not affect subsequent fearful behaviours [11]. These findings imply that corvids respond to the mere presence of objects, even if those objects are familiar within their environment. This study also found no clear differences in the number of landings based on the presence or absence of the object, or in the total time spent in the foraging area, except for the sensor-activated motion owl decoy. Although it is necessary to note that our sample size is limited, the experimental setup and procedures used in this study were considered to have detected avoidance responses in crows, consistent with previous research.

Large-billed Crows also showed a strong avoidance tendency when the owl decoy suddenly moved in the feeding area, compared with when the cardboard box was used. Because animals often perceive moving objects as biologically active and potentially risky [32,33], it is not surprising that the moving stimuli elicited rapid escape responses. However, the suddenly moving stimulus presented influenced crows’ level of subsequent avoidance behaviours in the feeding area. Large-billed Crows were more likely to reduce the number of landings in the presence of the sensor-activated motion owl decoy than in the presence of the other objects in the feeding area, resulting in a significant decrease in the amount of food consumed. Recent studies have shown that birds can categorize objects and distinguish potentially dangerous from non-dangerous items [34,35]. In addition, some bird species respond differently to non-biological versus biological objects [36,37], and in corvids, unexpected object movement can trigger startle responses [21]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the magnitude of avoidance is shaped not only by the mere presence of an object but also by additional factors such as its appearance and/or movement characteristics, although the present study could not identify which factor contributed most strongly to this heightened avoidance.

This study was a pilot trial designed to examine how Large-billed Crows respond to biological and non-biological objects, and it has several limitations. For example, although the amount of food consumed in the presence of the immobile owl decoy was significantly lower than under the condition with the cardboard box, no differences were detected in the other behavioural parameters. This suggests that the appearance of the objects may influence the avoidance behaviour in Large-billed Crows; however, our ability to detect statistically significant effects in the other measures may have been limited by the small sample size (n = four birds per group). Because a small sample size increases the likelihood of committing a Type II error—i.e., a false-negative result [38]—some differences may have gone undetected. In this study, each individual was tested only once in order to standardize prior experimental experience, which inevitably constrained the sample size. Future studies should employ larger sample sizes to enable more detailed and robust assessments.

The stress associated with transfer to captivity or temporary isolation may have heightened the birds’ wariness and hesitation, potentially prolonging feeding latency and reducing landing frequency independently of the experimental stimuli [39,40,41]. However, because all individuals experienced the same procedures, any stress-related alterations in feeding behaviours are likely to have affected only the baseline level of response rather than the relative differences among stimulus conditions. Moreover, the number of days individuals spent in captivity before testing varied in our study, raising the possibility that their levels of habituation or chronic stress differed among birds [26,42]. In this study, birds assigned to the condition with the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy—who had been held in captivity for the longest period—showed the strongest avoidance responses, whereas birds under the conditions with no visual stimulus and the cardboard box had shorter holding periods and showed weaker responses. Even if prolonged captivity had facilitated habituation and thereby reduced avoidance responses, the birds under the condition with the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy still showed significantly stronger avoidance than those under the other conditions. Therefore, captivity duration, at the very least, would have had only a minimal impact on the conclusions of this study; the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy elicited significantly stronger avoidance in Large-billed Crows than with both no visual stimulus and the cardboard box.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Large-billed Crows in captivity show avoidance responses to visual stimuli ranging from no visual object to non-biological and biological objects. Among the test conditions, the sensor-activated-motion owl decoy elicited the greatest increase in latency and the strongest reductions in subsequent behaviours, including landing frequency, compared with the non-visual and non-biological conditions. These findings suggest that crows evaluate not only the presence of an object but also its appearance, movement characteristics, and associated biological cues when adjusting their avoidance behaviour. While we made every effort to control extraneous influences and ensure the reliability of our captive experiments, we recognise that avoidance behaviour may be shaped by ecological factors that cannot be fully replicated in captivity. Thus, integrating controlled captive trials with field experiments will be essential to clarify how crows evaluate risk and adjust their foraging decisions in real-world environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/birds6040064/s1, Table S1: Information for all individuals used in the experiment. Table S2: Results of post hoc test; Figure S1: Experimental cage; Video S1: Curtained cardboard box, Video S2A–E: Crow–object interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., M.Y. and M.S.; methodology, M.F. and M.S.; investigation, M.F. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.; writing—review and editing, M.F., M.Y. and M.S.; supervision, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Experiment Committee of the Sustainable System Research Laboratory of the Electric Power Industry (protocol code: 2102-3 and date of approval: September 2024) and Nagaoka University of Technology in March 2024 (protocol code: R5-6 and date of approval: March 2024).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available via the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Akagi Testing Center and CERES, Inc. for assisting with animal care. We also thank Electric Power Engineering Systems, who improved the owl decoys. We are also grateful to Mataichi Hayashi for trapping the crows.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Manikowska-Ślepowrońska, B.; Ślepowroński, K. Is Winter Feeder Visitation by Songbirds Risk-Dependent? An Experimental Study. Birds 2025, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurim, I.; Abramsky, Z.; Kotler, B.P. Foraging Behavior of Urban Birds: Are Human Commensals Less Sensitive to Predation Risk than their Nonurban Counterparts? Condor 2008, 110, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.L.; Dill, L.M. Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: A review and prospectus. Can. J. Zool. 1990, 68, 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.L.; Feyten, L.E.A.; Preagola, A.A.; Ferrari, M.C.O.; Brown, G.E. Uncertainty about predation risk: A conceptual review. Biol. Rev. 2023, 99, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, M.; Slagsvold, T. The Neophobia Hypothesis: Nest decoration in birds may reduce predation by corvids. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 250427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathot, K.J.; Arteaga-Torres, J.D.; Besson, A.; Hawkshaw, D.M.; Klappstein, N.; McKinnon, R.A.; Sridharan, S.; Nakagawa, S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of unimodal and multimodal predation risk assessment in birds. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, T. Antipredator Defenses in Birds and Mammals; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam, J.F.; Fraser, D.F. Habitat Selection Under Predation Hazard: Test of a Model with Foraging Minnows. Ecology 1987, 68, 1856–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.L. Nonlethal Effects in the Ecology of Predator-Prey Interactions: What are the ecological effects of anti-predator decision-making? BioScience 1998, 48, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creel, S.; Christianson, D. Relationships between direct predation and risk effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.J.; Jones, D.N. Cautious crows: Neophobia in Torresian crows (Corvus orru) compared with three other corvoids in suburban Australia. Ethology 2016, 122, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greggor, A.L.; Clayton, N.S.; Fulford, A.J.C.; Thornton, A. Street smart: Faster approach towards litter in urban areas by highly neophobic corvids and less fearful birds. Anim. Behav. 2016, 117, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.; Lambert, M.L.; Frohnwieser, A.; Brecht, K.F.; Bugnyar, T.; Crampton, I.; Garcia-Pelegrin, E.; Gould, K.; Greggor, A.L.; Izawa, E.; et al. Socio-ecological correlates of neophobia in corvids. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kijne, M.; Kotrschal, K. Neophobia affects choice of food-item size in group-foraging common ravens (Corvus corax). Acta Ethologica 2002, 5, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.L.; Clayton, N.S.; Thornton, A. Wild jackdaws, Corvus monedula, recognize individual humans and may respond to gaze direction with defensive behaviour. Anim. Behav. 2015, 108, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, M.R. Protecting Vegetables from Crows Using an Animated Crow-Killing Owl Model. J. Wildl. Manag. 1985, 49, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bötsch, Y.; Gugelmann, S.; Tablado, Z.; Jenni, L. Effect of human recreation on bird anti-predatory response. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.; James, P. The Landscape of Fear as a Safety Eco-Field: Experimental Evidence. Biosemiotics 2023, 16, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, B.A.; Chen, J.R.J.; Lin, H.S.; Sun, Y.H. The Effects of Rainfall, Temperature, and Wind on a Community of Montane Birds in Shei-Pa National Park, Taiwan. Zool. Stud. 2017, 56, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, R.E. Avian Diversity of Rice Fields in Southeast Asia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greggor, A.L.; McIvor, G.E.; Clayton, N.S.; Thornton, A. Wild jackdaws are wary of objects that violate expectations of animacy. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 181070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamada, K. Sexual differences in the external measurements of Carrion and Jungle Crows in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn. J. Ornithol. 2004, 53, 93–97. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Shirai, M. Evaluation of food preference in wild-caught Large-billed Crows under captive feeding conditions: A pilot study. In Proceedings of the 31st Vertebrate Pest Conference, Monterey, CA, USA, 11–14 March 2024; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8977c3m9 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Chiba, A.; Onojima, M.; Kinoshita, T. Prey of the long-eared owl Asio otus in the suburbs of Niigata City, central Japan, as revealed by pellet analysis. Ornithol. Sci. 2005, 4, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Takatsuku, S.; Higuchi, A.; Saito, I. Food habits of the ural owl (Strix uralensis) during the breeding season in Central Japan. J. Raptor Res. 2013, 47, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluen, E.; Rönkä, K.; Thorogood, R. Prior experience of captivity affects behavioural responses to ‘novel’ environments. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, Z.; Liker, A.; Mónus, F. The effects of predation risk on the use of social foraging tactics. Anim. Behav. 2004, 67, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team 2020: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friant, S.C.; Campbell, M.W.; Snowdon, C.T. Captive-born cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus) respond similarly to vocalizations of predators and sympatric nonpredators. Am. J. Primatol. 2008, 70, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisenden, B.D.; Harter, K.R. Motion, not Shape, Facilitates Association of Predation Risk with Novel Objects by Fathead Minnows (Pimephales promelas). Ethology 2001, 107, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, N.; Veselý, P.; Fuchs, R. Object categorization by wild ranging birds—Winter feeder experiments. Behav. Process. 2017, 143, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Møller, A.P.; Morelli, F.; Biaduń, W.; Brauze, T.; Ciach, M.; Czechowski, P.; Czyż, S.; Dulisz, B.; Goławski, A.; et al. Urbanization affects neophilia and risk-taking at bird-feeders. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensel, L.; Wilder, J. The effects of owl decoys and non-threatening objects on bird feeding behavior. Quercus Linfield J. Undergrad. Res. 2012, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Heales, H.E.; Flood, N.J.; Oud, M.D.; Otter, K.A.; Reudink, M.W. Exploring differences in neophobia and anti-predator behaviour between urban and rural mountain chickadees. J. Urban Ecol. 2024, 10, juae014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborsky, M. Sample Size in the Study of Behaviour. Ethology 2010, 116, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, M.J.; Earle, K.A.; Romero, L.M. Initial transference of wild birds to captivity alters stress physiology. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2009, 160, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattin, C.R.; Pechenenko, A.V.; Carson, R.E. Experimentally reducing corticosterone mitigates rapid captivity effects on behavior, but not body composition, in a wild bird. Horm. Behav. 2017, 89, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, A.M.; Stocker, M.; Stöwe, M.; Massen, J.J.M.; Bugnyar, T. Behavioural and Hormonal Stress Responses to Social Separation in Ravens, Corvus corax. Ethology 2017, 123, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.P.; Wright-Lichter, J.; Romero, L.M. Chronic stress and the introduction to captivity: How wild house sparrows (Passer domesticus) adjust to laboratory conditions. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2018, 259, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).