Simple Summary

For rectal cancer radiation therapy, VMAT beams passing through the treatment couch before reaching the patient can increase the posterior skin dose. This study evaluated how a standard treatment mattress and a low-density foam board affect the posterior skin dose for VMAT treatments. Phantom measurement results show that the mattress does not provide meaningful sparing, while a 10 cm foam board reduced the posterior surface dose by 8.3% on average.

Abstract

Background: One method for the radiation therapy of rectal cancer is to set patients supine and treat them with volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). The posterior skin dose is of concern due to undesirable bolusing from mounting surfaces the patient lays upon, namely the carbon fiber couch (CFC). The posterior skin dose may be mitigated by positioning the patient on top of a low-density material that separates the patient from the CFC. Purpose: Our objective was to determine the reduction in the posterior surface dose when a mattress or foam board is used to prop the patient away from the CFC. Materials and Methods: Three clinical rectal cancer patient VMAT plans were selected. A solid water phantom with optically stimulated luminescence dosimeters (OSLDs) placed at the posterior surface was mounted using three setups: directly on the CFC, with a mattress on the CFC, and with a 10 cm thick foam board on the CFC. The three VMAT plans were delivered to this phantom, with OSLDs measuring the posterior surface dose with each setup. In the treatment planning system (TPS), the CFC only, mattress, and foam board setups were simulated on the patient’s anatomy with posterior surface doses reported. Results: The OSLD measurements in the phantom showed that the mattress reduced the posterior surface dose on average by 1.3%, and the foam board reduced the dose by 8.3%. The TPS estimates demonstrated that, on average, the mattress reduced the surface dose by 15.8%, and the foam board reduced the dose by 33.0%. It is likely that the TPS had limitations accurately modeling the surface dose, so OSLD measurements were closer to clinical reality. Conclusions: The mattress does not reduce the posterior skin dose enough to warrant its use as a skin sparing device. The CFC produces a bolusing effect that can be reduced by separating the patient from the CFC with a 10 cm thick foam board.

1. Introduction

In Canada, the age-standardized incidence rate of colorectal cancer is 60.5 cases per 100,000 people, placing it among the top four highest-incidence cancers [1]. The current standard of care for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer is preoperative radiation therapy or chemo-radiation, followed up with total mesorectal excision [2]. Radiation therapy may be delivered via 3D conformal radiation therapy (3DCRT), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT).

VMAT has been shown to be of clinical benefit in treating rectal cancer patients. Dosimetrically, there is superior small bowel sparing compared with 3DCRT techniques, along with an excellent conformality to the target [3]. Using image-guided radiation therapy mediated with in-room cone beam CT imaging (CBCT), highly conformal VMAT plans can be delivered accurately relative to the patient anatomy.

Traditionally, rectal cancer was treated in the prone position and on a belly board [4,5,6]. The aim of this setup was to move the small bowel away from the treatment volume by depending the abdomen through a hole in the belly board. With increasing sophistication in beam delivery, the supine position has been explored as a more comfortable treatment setup [7,8,9]. A comparison of prone and supine setups with VMAT demonstrated that small bowel and bladder doses are not significantly different between prone and supine setup patients and the supine orientation is more reproducible, as shown by CBCT-derived metrics [8].

The posterior skin dose may become a concern when using the supine position and VMAT. In the supine position, the patient posterior is in contact with the linear accelerator’s carbon fiber couch (CFC). The bolusing effect of CFCs on the skin dose is not negligible [10,11,12,13]. A standard prescription dose for preoperative rectal cancer, 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions, is in the skin toxicity range [14,15], and the planning target volume (PTV) is typically near the posterior surface. Posterior beam entry is often employed for VMAT techniques that use partial or full arcs, producing bolusing effects when passing through the treatment couch and other support structures. In consideration of this, we treat supine patients on top of a 10 cm thick hard foam board for the purposes of posterior skin sparing. There are other potential options, such as having the patient lying on top of either a thin mattress or directly on the CFC, both of which are explored in this study.

The objective of this work is to quantify the relative effects of three mounting surfaces on the posterior skin dose: the patient lying directly on the CFC, on a thin standard treatment mattress on top of the CFC, and on a foam board on top of the CFC. We delivered clinical VMAT plans for rectal cancer patients to a solid water phantom propped on these three mounting surfaces and measured the posterior surface dose using optically stimulated luminescence dosimeters (OSLDs) [16,17]. In addition to the phantom measurements, we estimated the posterior skin doses of the clinical plan with the patient anatomy by simulating the effect of the three mounting surfaces in the TPS. There was no expectation that the surface dose is accurately calculated by the TPS due to approximations in the surface dose calculation, particularly when adjacent to low-density accessories [12,18]; however, the TPS results may provide supplementary data to support the conclusions from the phantom measurements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Radiation Treatment Planning

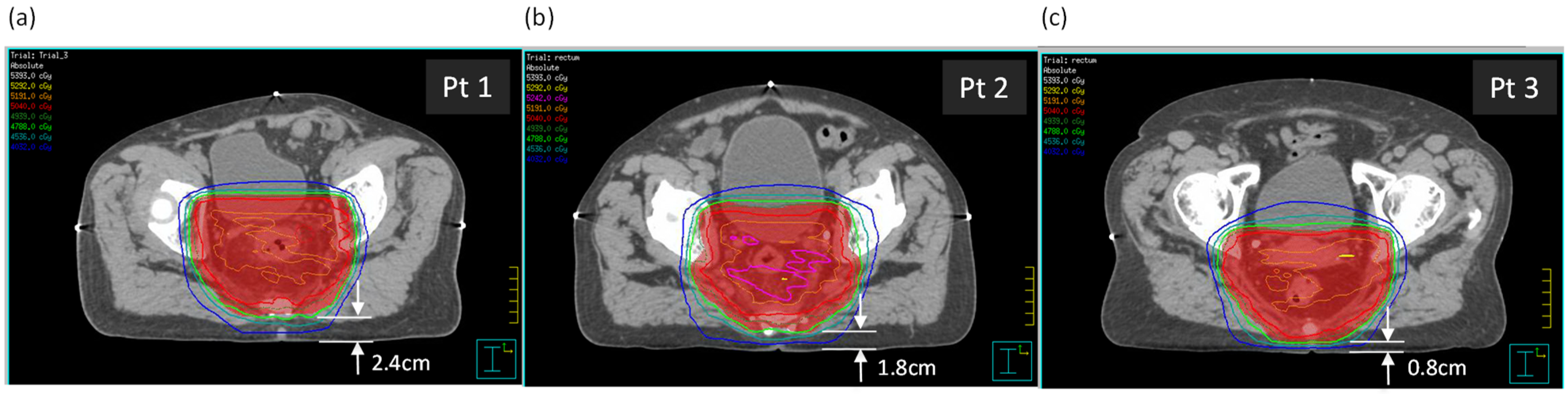

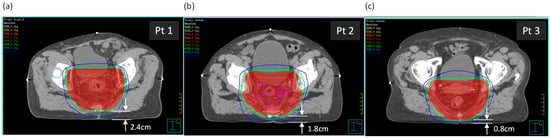

Three rectal cancer patient plans with supine setup were selected, with varying distances between the posterior skin surface and the planning target volume (PTV). Dimensions relevant to the study are in Table 1. The three patients were selected partially due to similar anterior–posterior (AP) and lateral separations, as well as a variation in the distance between the posterior surface and the PTV (see Figure 1). The tabletop height (TTH) is the distance from the posterior surface to the treatment isocenter.

Table 1.

Dimensions for each patient that are relevant to the experimental setup.

Figure 1.

The three patients, (a) Patient 1, (b) Patient 2, and (c) Patient 3, shown at the axial isocentric plane. Distances from the posterior surface to the PTV are shown.

Patients were simulated and treated supine and on top of a 10 cm thick hard foam board, with the intention of reducing the posterior skin dose. Clinical treatment plans were generated in the Pinnacle3 v9.8 TPS from Philips (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for delivery on the Synergy Agility treatment linac from Elekta (Stockholm, Sweden). The VMAT arc geometry was a ~180° posterior arc. Planners aimed to meet a CTV coverage of V50.4 > 99% and a PTV coverage of V47.9 > 99%, limiting V52.9 to <1% of the PTV.

At our center, for all clinical plans, we simulate the attenuation of the treatment couch in our TPS using a density-overridden contour (relative density of 1, thickness of 1 cm) that has a water-equivalent thickness to the treatment couch, as suggested by AAPM’s Task Group 176 [11]. This couch model is placed at the level of the CT simulator couch top.

2.2. Carbon Fiber Couch, Mattress, and Foam Board Descriptions

The carbon fiber couch was an iBeam evo couch top manufactured by Elekta mounted on their linear accelerator systems. The construction is a carbon fiber shell with a low-density foam core.

The mattress is from Donaldson Marphil Medical (Brossard, QC, Canada), made of a thin, blue vinyl covering filled with low-density padding material. With a patient or phantom on top of the mattress, it compresses to ~1 cm thick. The density of the mattress interior as measured by CT is approximately 0.05 g/cm3.

The foam board was built in-house, consisting of 10 cm thick low-density structural foam covered with thin plastic sheeting for easy cleaning. The foam board is hard enough that it does not deform with a patient’s weight. The density of the foam board as measured by CT is approximately 0.03 g/cm3.

2.3. Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dosimetry

A commercially available optically stimulated luminescence dosimetry system, the MicroStar reader from Landauer (Glenwood, IL, USA), was used for surface dose measurement. The individual dosimeters were high-accuracy nanoDots (also from Landauer) readable with the MicroStar system.

The nanoDot OSLDs, in their casing, are 10 × 10 × 2 mm in size. Encapsulated within a black plastic casing is a small disc of the optically stimulated luminescence dose-sensitive material, which is Al2O3 doped with carbon. The individual OSLD calibration factor is encoded in a 2D barcode printed on a label affixed to the OSLD. After irradiation, the OSLDs can be inserted into an optically stimulated luminescence reader to obtain the dose.

With our monthly quality assurance process, we determined that, in the dose range of 10–300 cGy, the dose accuracy of the OSLD system is ±3% (all OSLD measurement readings in this study are comfortably within this dynamic range). Angular dependence was determined by Jursinic to be within typical OSLD measurement uncertainty and was not a concern for our phantom geometry [16,17]. We measured the radiological buildup of the OSLD casing and found it to be 1.2 mm for a 6 MV beam, approximately the same as half of the physical thickness of the casing. Although these dosimeters measure at 1.2 mm depth and technically represent the near-surface dose, we refer to OSLDs measuring “surface dose” throughout for brevity.

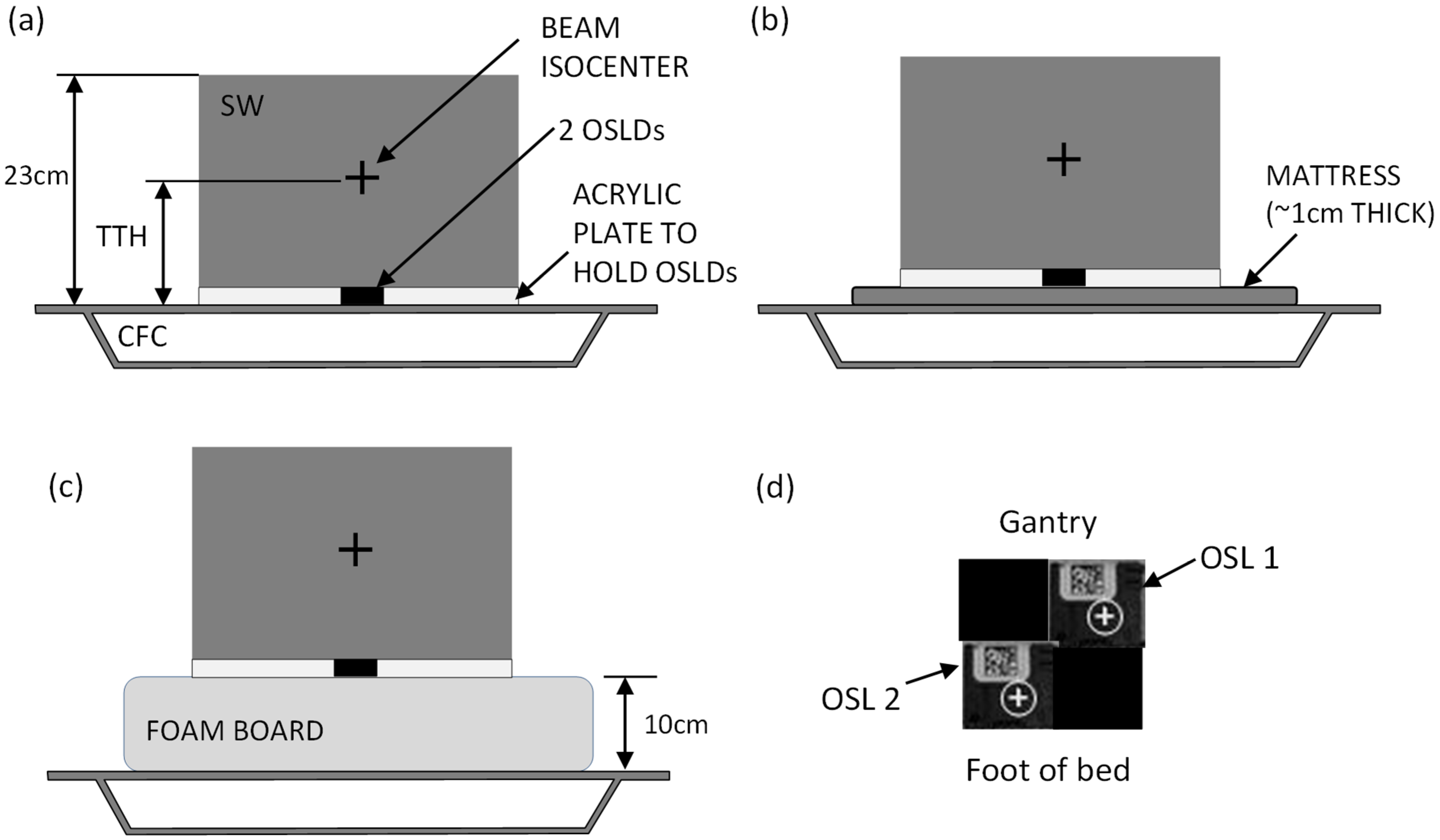

2.4. Solid Water Phantom Setup

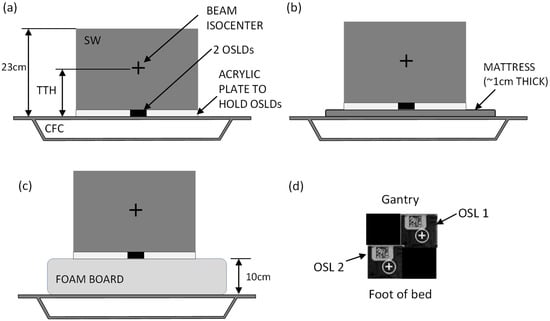

Solid water (SW) phantom measurements were selected for a controlled evaluation of posterior surface dose under reproducible conditions. This approach isolated the dosimetric effects of different support structures while avoiding confounding factors such as patient motion or setup variability. A stack of solid water 23 cm high, 30 cm long and 30 cm wide was used to simulate the patient anatomy (Figure 2) and is representative of patient anterior–posterior and lateral separations (Table 1), although there are limitations, as the phantom does not replicate patient contours or internal anatomy. The density of the solid water was 1.0 g/cm3. The SW sat upon a 2 mm thick acrylic plate with a central square hole for inserting OSLDs. Two OSLDs were placed inside this acrylic plate, as shown in Figure 2d. Three setups were used: the phantom directly on top of the CFC; the phantom on top of a mattress mounted on the CFC; and the phantom on top of a foam board mounted on the CFC (Figure 2a–c). The VMAT plan of each of the three patients was delivered to this phantom for each of the three setups, with the beam isocenter placed according to the specified TTH parameter for each plan. The OSLDs were read <24 h afterwards.

Figure 2.

Solid water phantom setup. (a) SW and OSLDs set up directly on the CFC; (b) phantom set up on the mattress; (c) phantom setup on the foam board. The beam isocenter is centered laterally and in the cranio-caudal direction. Panel (d) shows the OSLD layout (top view) as set inside the acrylic plate, with two measurement OSLDs and two “filler” OSLDs to avoid air gaps.

2.5. TPS Estimation of Skin Doses

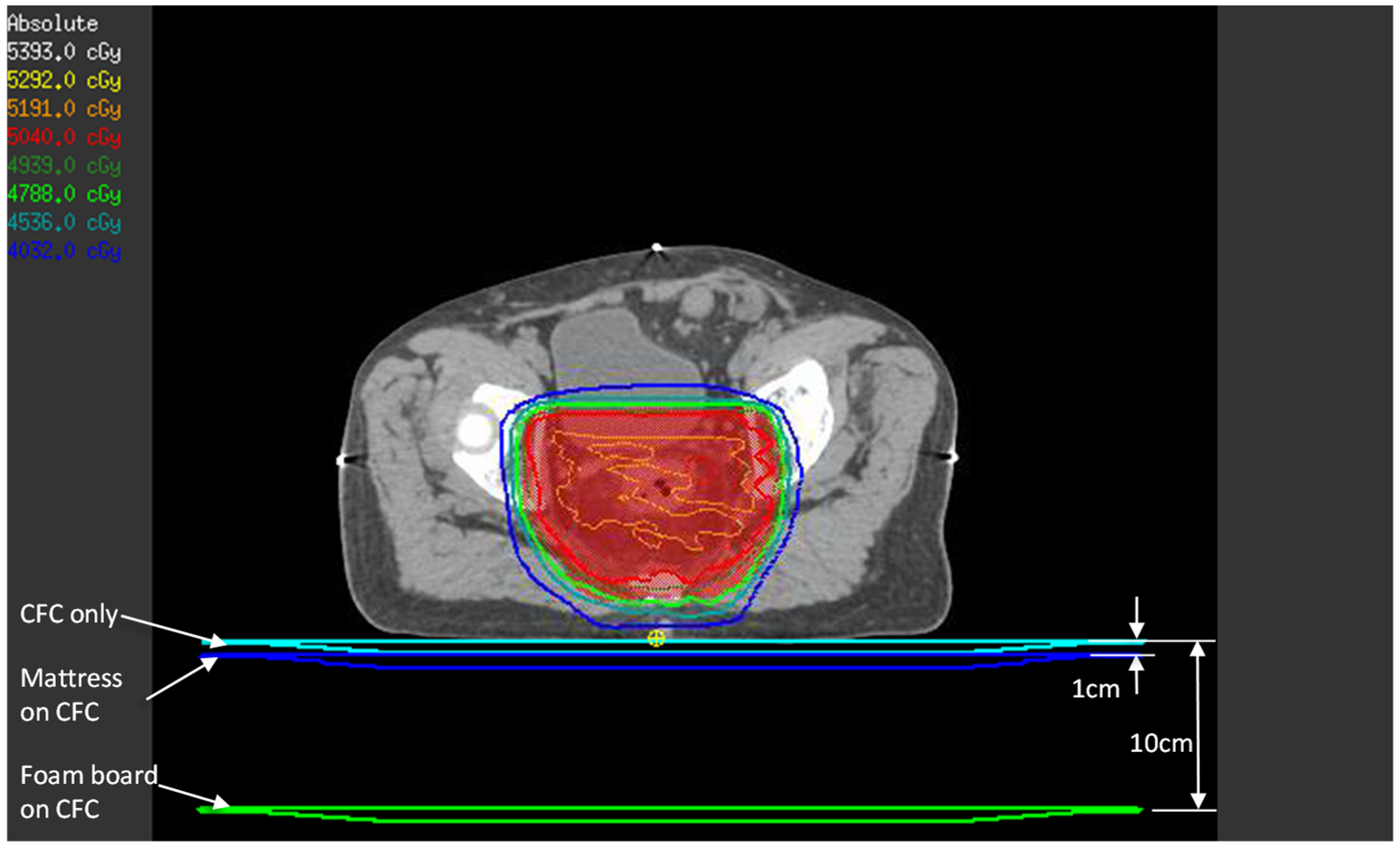

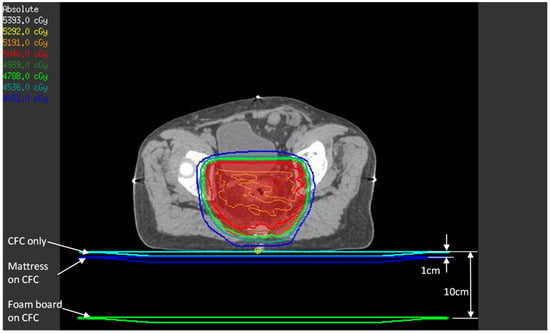

Although TPS estimation of the surface and buildup doses has accuracy issues when using a collapsed cone convolution algorithm [18], we thought it would be instructive to compare TPS calculations and the OSLD phantom measurements. The patients’ treatment CT images and VMAT plans were used in this estimation. To simulate the effect of each setup, the 1 cm water-equivalent couch model that we use clinically was placed directly under the patient (simulates CFC only setup), 1 cm from the posterior of the patient (simulates mattress setup), and 10 cm from the patient’s posterior surface (simulates foam board setup), as in Figure 3. A dose point was created at 1.2 mm depth from the patient’s posterior surface immediately below the beam isocenter—this represents the approximate location of the OSLD sensitive volume in the phantom experiment.

Figure 3.

TPS estimate of posterior skin dose with the three setups. For each setup (CFC only, mattress, and foam board), the three couch models shown were density-overridden to 1 g/cm3 one at a time, and beams were calculated to obtain the posterior skin dose, represented by the small yellow point of interest.

In the Pinnacle3 TPS, creating a region of interest to represent the mattress or the foam board and density-overriding it does not factor into the dose calculation. The TPS treats these as “air”, since the mattress and the foam board have a much lower density than the threshold density above which the dose calculation algorithm acts upon (we set this threshold to 0.6 g/cm3). Hence, the method described above is the closest approximation to the three setups in this study.

Although the phantom experiment and the TPS estimation process use different geometries to determine dose (i.e., SW stack vs. patient CT), reasonably close numerical agreements are expected since the lateral and AP separations are well matched.

3. Results

3.1. Solid Water Phantom Measurements

Table 2 shows the OSLD measurements for the three setups (dose was scaled up to 28 fractions). The two OSLDs used per irradiation were always close in magnitude, which lends confidence to the measurement results, as the OSLDs were placed within ~1 cm of each other.

Table 2.

OSLD dose measurements from phantom experiment, in cGy. The OSLD result was multiplied by 28 to obtain the total dose for 28 fractions. The percent reductions due to the mattress and foam board are displayed.

The percent difference (relative to the CFC-only setup) from using the mattress and the foam board are also shown. This percent difference was calculated using the average of the two OSLD measurements per irradiation. On average, the mattress reduces the posterior surface dose by 1.3%, and the foam board reduces the surface dose by 8.3%. For each of the three patient plans, the foam board measurements showed a lower posterior surface dose than the mattress, and the mattress had a lower posterior surface dose than for the CFC alone.

3.2. TPS Estimation of Skin Doses

Table 3 displays the TPS estimates of posterior skin dose. The percent difference due to the mattress and the foam board were calculated in a similar manner to the phantom experiment. As calculated by the TPS, the percent reduction due to the mattress on average was 15.8%; for the foam board, it was 33.0%. As with the OSLD measurements, the TPS-calculated foam board posterior skin doses were lower than for the mattress, which in turn were lower than for the CFC alone.

Table 3.

TPS estimation of posterior skin dose simulating different patient setups, in cGy, with the percent reductions due to the mattress and foam board displayed.

4. Discussion

In clinical rectal cancer treatment with VMAT, posterior beam entry is common due to the target location and dose constraints for normal tissue. The interaction of the beam with supportive structures underneath the patient and the patient’s posterior surface may not be fully accounted for with regard to the posterior surface dose. This study examined three support structures—the linac’s carbon fiber couch, a standard treatment mattress that is typically used for patient comfort, and a 10 cm thick foam board—to determine their effect on posterior surface dose.

The phantom measurements in this study show a minimal decrease in the posterior skin dose due to the mattress, and a much larger decrease due to the foam board. The average reduction due to the mattress of 1.3% is not nearly enough to justify its use as a skin sparing device, though it does not increase the surface dose either. Also, the mattress is deformable, which may result in some inaccuracies due to interfraction changes in the patient posterior surface. The foam board, on the other hand, resulted in an 8.3% average posterior skin dose reduction. At skin dose levels spanning 35–46.5 Gy with the CFC only, this level of dose reduction may be clinically meaningful for patient skin toxicity [14]. However, clinical outcomes are out of the scope of this study; only dosimetric results are reported here. The foam boards are rigid enough that they do not deform under a patient’s weight.

For the CFC-only setup, the OSLD measurements and the TPS estimated doses were similar. The OSLD averages and the TPS estimates were, for patient 1, 4103 cGy and 4167 cGy; for patient 2, 3814 cGy and 3832 cGy; and, for patient 3, 4611 cGy and 4882 cGy. As mentioned previously, this should not be too surprising, as the solid water phantom dimensions and the patient AP and lateral separations were well-matched. The TPS estimates of percent reduction statistics for the mattress and foam board were quite far apart from the OSLD measurements (Table 2 and Table 3). One partial explanation is that Pinnacle underestimates the surface dose because the electrons liberated from the mattress or the foam board are not accounted for in the dose calculation. Indeed, the TPS posterior skin dose estimates for the mattress and foam board setups are much less than those of the OSLD measurements. Also, superposition–convolution dose algorithms rely on precomputed dose kernels that assume a charged particle equilibrium, which breaks down near material interfaces, particularly where there are pronounced build-up effects. It is reasonable to trust the phantom measurements for the mattress and foam board setups over the calculations from the TPS.

The differences between the measurements and the TPS results suggest that using inverse optimization to limit the posterior skin dose during planning is limited by the ability of the TPS to accurately model dose near the patient’s surface. Monte Carlo treatment planning systems, with their superior ability to model interface effects compared to convolution systems, may prove useful in this regard [19]; however, the inherent bolusing effects associated with treatment couches and support devices remain, as elucidated in TG176 [11], which this work aims to address.

There is a variation in VMAT implementations for pelvic radiation therapy, with full arcs, multiple arcs, and a diversity of treatment platforms being available. For rectal cancer radiation therapy, the target is typically posteriorly located, and VMAT arcs commonly include posterior beam entry. Although this study was limited to using a 180° posterior VMAT arc, other VMAT arc geometries are expected to exhibit similar posterior surface dose effects, as beams are likely to enter the posterior surface across most clinical implementations.

To our knowledge, this is the first look at how the posterior skin dose might be affected when treating rectal cancer patients in the supine position and with VMAT. For the prone setup, this was never a concern because the patient posterior surface was in air and benefiting from the full skin sparing effect of megavoltage photon energies. When supine, beaming through a mounting surface on the way to the posterior skin may result in unintentional bolusing, the effects of which were studied in this work.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that the selection of support surfaces can meaningfully influence the posterior surface dose, and that these effects may not be reliably reflected in treatment planning system dose calculations. We measured in-phantom the posterior surface dose for rectal cancer patients in the supine position and using VMAT, with three different setups: the direct placement on a CFC, with a standard mattress, and with a 10 cm foam board. The mattress in this study does not reduce the posterior skin dose enough to warrant its use as a skin sparing device; its primary use is for patient comfort. The CFC produces a bolusing effect that can be reduced by separating the patient from the CFC with a 10 cm foam board, which may be clinically desirable.

By providing a measurement-based characterization of the posterior surface dose under controlled phantom conditions, this work supplements planning-based approaches and supports more informed evaluations of patient support material effects for supine rectal cancer VMAT treatments, as well as similar patient treatment settings.

Author Contributions

A.K. (Anthony Kim): Concept, methodology, experimentation, analysis, writing; A.K. (Aliaksandr Karotki): Concept, methodology, experimentation, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was prepared without any external source of funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted as part of institutional quality improvement activities and did not require research ethics board approval.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2023-statistics/2023_PDF_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2026).

- Kennedy, E.; Vella, E.T.; Blair Macdonald, D.; Wong, C.S.; McLeod, R. Optimisation of preoperative assessment in patients diagnosed with rectal cancer. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 27, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dröge, L.H.; Weber, H.E.; Guhlich, M.; Leu, M.; Conradi, L.C.; Gaedcke, J.; Hennies, S.; Herrmann, M.K.; Rave-Fränk, M.; Wolff, H.A. Reduced toxicity in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: A comparison of volumetric modulated arc therapy and 3D conformal radiotherapy. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelt, A.L.; Sebag-Montefiore, D. Technological advances in radiotherapy of rectal cancer: Opportunities and challenges. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2016, 28, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allal, A.S.; Bischof, S.; Nouet, P. Impact of the “belly board” device on treatment reproducibility in preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2002, 178, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Chie, E.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Cho, K.H.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Sohn, D.K.; Jeong, S.Y.; Park, J.G. Comparison of the belly board device method and the distended bladder method for reducing irradiated small bowel volumes in preoperative radiotherapy of rectal cancer patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 62, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drzymala, M.; Hawkins, M.A.; Henrys, A.J.; Bedford, J.; Norman, A.; Tait, D.M. The effect of treatment position, prone or supine, on dose-volume histograms for pelvic radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 2009, 82, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.; Karotki, A.; Presutti, J.; Gonzales, G.; Wong, S.; Chu, W. The effect of prone and supine treatment positions for the preoperative treatment of rectal cancer on organ-at-risk sparing and setup reproducibility using volumetric modulated arc therapy. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijkamp, J.; Doodeman, B.; Marijnen, C.; Vincent, A.; van Vliet-Vroegindeweij, C. Bowel exposure in rectal cancer IMRT using prone, supine, or a belly board. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 102, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaylov, I.B.; Penagaricano, J.; Moros, E.G. Quantification of the skin sparing effect achievable with high-energy photon beams when carbon fiber tables are used. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 93, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olch, A.J.; Gerig, L.; Li, H.; Mihaylov, I.; Morgan, A. Dosimetric effects caused by couch tops and immobilization devices: Report of AAPM Task Group 176. Med. Phys. 2014, 41, 061501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kry, S.F.; Smith, S.A.; Weathers, R.; Stovall, M. Skin dose during radiotherapy: A summary and general estimation technique. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2012, 13, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Cao, Z.; Wei, Y.; Cao, T.; Shen, J.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Radiation dosimetry effect evaluation of a carbon fiber couch on novel uRT-linac 506c accelerator. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, P.N. Surface dose and acute skin reactions in external beam breast radiotherapy. Med. Dosim. 2020, 45, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zou, H.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X.; He, H.; Zhang, D.; Du, D.; Zou, C. Efficacy and safety of different radiotherapy doses in neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1119323. [Google Scholar]

- Jursinic, P.A. Characterization of optically stimulated luminescent dosimeters, OSLDs, for clinical dosimetric measurements. Med. Phys. 2007, 34, 4594–4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jursinic, P.A. Angular dependence of dose sensitivity of nanoDot optically stimulated luminescent dosimeters in different radiation geometries. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 5633–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaptan, I.; Akdeniz, Y.; Ispir, E.B. A comparative evaluation of surface dose values: Radiochromic film measurements versus computational predictions from different radiotherapy planning algorithms. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.B.; Sarfehnia, A.; Paudel, M.R.; Kim, A.; Hissoiny, S.; Sahgal, A.; Keller, B. Evaluation of a Commercial MRI-Linac-Based Monte Carlo Dose Calculation Algorithm with GEANT4. Med. Phys. 2016, 43, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.