Simple Summary

Radiopharmaceutical therapy is a type of cancer treatment that delivers radiation directly to tumors using targeted drugs. When combined with drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors, which help the immune system attack cancer, this approach may improve treatment outcomes. However, not all radioactive drugs behave the same way, and the amount and pattern of radiation delivered inside tumors can change how the immune system responds. In this study, we tested three different radioactive versions of a tumor-targeting antibody in mice with cancer to understand how each affects immune activity and survival. We found that both the type of radioactive particle and the radiation dose play major roles in stimulating helpful immune responses. When paired with immunotherapy, certain combinations led to stronger tumor control. These results may guide the development of safer and more effective treatment strategies that combine targeted radiation with immunotherapy for difficult-to-treat cancers.

Abstract

Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) offers tumor-selective radiation delivery and represents a promising platform for combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). While prior studies suggest that RPT can stimulate antitumor immunity, synergy with ICIs may depend on radionuclide properties, absorbed dose, and radiation distribution within the tumor microenvironment. This study evaluated how radionuclide selection and dose influence immune stimulation and therapeutic efficacy of GD2-targeted antibody-based RPT combined with ICIs. Dinutuximab, an anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody, was radiolabeled with β−-emitters (90Y, 177Lu) or an α-emitter (225Ac). C57Bl6 mice bearing GD2+ tumors received 4 or 15 Gy tumor-absorbed doses, determined by individualized dosimetry, with or without dual ICIs (anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1). In vivo imaging, ex vivo biodistribution, survival, histological, and gene expression analyses were performed to assess therapeutic and immunological outcomes. All radiolabeled constructs demonstrated preferential uptake in GD2+ tumors. Combination therapy improved survival in a radionuclide- and dose-dependent manner, with the greatest benefit in the 225Ac + ICI group at 15 Gy. Treatment activated type I interferon signaling and increased MHC-I and PD-L1 expression. Notably, 90Y reduced regulatory T cells, enhancing CD8+/Treg ratios, while 225Ac induced robust interferon-driven activation. Radionuclide selection and absorbed dose critically shape immune and therapeutic outcomes of antibody-based RPT combined with ICIs, underscoring the importance of delivery mechanism and dose optimization in combination therapy strategies.

1. Introduction

Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) is a cancer treatment modality that enables the targeted delivery of ionizing radiation to malignant cells using radiolabeled agents [1]. These radiopharmaceuticals, which consist of a radioactive isotope linked to a targeting vector that recognizes tumor-associated molecular features, serve both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes [2]. Increasing evidence from preclinical models supports the therapeutic potential of combining RPT with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) to enhance anti-tumor efficacy [3,4]. For instance, NM600 is a small molecule radiotherapeutic that synergizes with checkpoint blockade to produce enhanced tumor regression in murine models [4,5,6,7,8]. This strategy has entered clinical evaluation, including trials investigating 177Lu-PSMA-617, an agent approved for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, in combination with ICIs [9,10,11].

ICIs have transformed cancer treatment by overcoming regulatory mechanisms that suppress T cell activation and function [12]. These agents, which target pathways such as PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4, unleash endogenous anti-tumor immunity and have shown durable responses in a subset of patients across multiple tumor types [12]. However, many malignancies remain resistant to ICI monotherapy or relapse early during treatment [13], highlighting the need for complementary approaches that stimulate the tumor immune microenvironment.

Monoclonal antibodies serve as effective targeting vectors in RPT by delivering cytotoxic radiation to antigen-expressing tumor cells, thus sparing normal tissues [14]. When combined with ICIs, antibody-based RPT offers the dual advantage of direct tumor cytotoxicity and potential immunogenic modulation [1,14]. This strategy is particularly compelling in the context of GD2, a disialoganglioside that is overexpressed in neuroblastoma, melanoma, and certain sarcomas but exhibits minimal expression in normal tissues [15,16]. Dinutuximab, an anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody approved for high-risk neuroblastoma, mediates tumor cell killing via immune effector mechanisms and is currently under clinical evaluation for other GD2-positive tumors [16,17]. However, due to their relatively large molecular size, monoclonal antibodies exhibit limited tissue penetration and heterogeneous intratumoral distribution, which may restrict therapeutic efficacy, particularly in poorly vascularized or densely cellular tumor regions [18].

Previous studies have shown that external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) can enhance ICI efficacy by promoting immune cell infiltration and altering the tumor microenvironment [19,20]. In some cases, EBRT has been observed to induce abscopal effects, wherein immune-mediated tumor regression occurs at sites distant from the irradiated field, likely due to systemic activation of antitumor immunity [20,21]. However, unlike RPT, EBRT is inherently limited in its capacity to irradiate all tumor sites simultaneously in patients with widespread metastatic disease. This spatial limitation may constrain its ability to stimulate a systemic immune response [4]. In contrast, RPT enables systemic delivery of targeted radiation to both visible and occult tumor lesions [22], making it particularly well-suited for combination with immunotherapy. Indeed, targeted RPT has shown encouraging synergy with ICIs in preclinical and early-phase clinical studies [3,9,10,23]. Radiation itself is known to stimulate antitumor immunity through mechanisms such as immunogenic cell death and activation of dendritic cells [24]. Importantly, heterogeneous radiation dose distribution within tumors may further amplify immune responses and facilitate checkpoint blockade sensitivity. For instance, brachytherapy, which delivers high-dose radiation locally while minimizing exposure to surrounding tissues, can influence the immune response and tumor microenvironment [25,26]. Low-dose radiation has also been shown to reduce cancer-associated fibroblasts and enhance T-cell infiltration [27]. These immunomodulatory effects support the rationale for exploring low- and intermediate-dose RPT in combination with immunotherapy [4,7,8,27].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture

The murine melanoma B78-D14 (B78) cell line, derived from B16 melanoma as previously described, was obtained from Dr. Ralph Reisfeld (Scripps Research Institute; La Jolla, CA, USA) in 2002 [28]. The B16F10(B16) melanoma cell line, syngeneic to C57BL/6 mice, was originally obtained from Dr. William Ershler (University of Wisconsin–Madison; Madison, WI, USA) [29]. B78 cells have functional GD2/GD3 synthase and express the disialoganglioside GD2 whereas the B16 cell line lacks GD2 expression [28,30,31]. The 9464D cell line was originally obtained from Dr. Jon Wigginton (National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, USA) and was developed by Dr. William Weiss (University of California, San Francisco; San Francisco, CA, USA) from spontaneous neuroblastoma tumors arising in TH-MYCN transgenic mice on a C57BL/6 background [32,33]. The neuroblastoma 9464D-GD2 cell line, derived from 9464D neuroblastoma as previously described, was obtained from Dr. Paul Sondel (University of Wisconsin–Madison) [32]. 9464D-GD2 cells have functional GD2 and GD3 synthases and were selected for interferon-γ inducible MHC-I expression [34]. All cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. B78 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. B16 and 9464D cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. 9464D-GD2 cells were additionally supplemented with 1× MEM non-essential amino acids and antibiotics (puromycin at 6 µg/mL and blasticidin at 7.5 µg/mL) to maintain expression of GD2 and GD3 synthases. Cell line authentication was performed according to ATCC guidelines based on morphology and growth characteristics. Mycoplasma testing was routinely performed and was confirmed negative using MycoStrip (InvivoGen; San Diego, CA, USA).

2.2. Murine Tumor Models

All mouse studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (protocol: M005853) and conducted in accordance with the Research Animal Resource Center guidelines. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Taconic at 8–10 weeks of age for melanoma tumor models, and from JAX at 5–7 weeks of age for neuroblastoma tumor models. All mice were stabilized for seven days before the initiation of research studies. Both male and female mice were included in therapy studies, while only female mice were used for imaging and correlative studies.

2.2.1. Imaging Studies

B78 tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous flank injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells on the right flank five weeks before imaging (tumor size ~150–200 mm3), and B16 tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous injection of 1 × 106 tumor cells on the left flank of the same mice (n = 4) two weeks before imaging (tumor size ~200–300 mm3). Tumor size was determined using calipers and volume approximated as (length × width2)/2. 9464D-GD2 tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous flank injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells on the right flank three weeks before imaging (~100–150 mm3), and 9464D tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells on the left flank two weeks prior (~150–200 mm3) for PET/CT, SPECT/CT, and ex vivo biodistribution gamma counting. B78 tumors were engrafted for alpha camera imaging five weeks prior (~150–200 mm3) by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells on the right flank.

2.2.2. Therapy Studies

B78 tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells. Mice were randomized immediately before treatment based on tumor size. Only mice with palpable flank tumors were included in the study at four weeks (tumor volume ~50–100 mm3). The day of RPT was defined as “day 1” of treatment. Anti-murine CTLA-4 (IgG2c, clone 9D9, NeoClone; Madison, WI, USA) and anti-murine PD-L1 (IgG2b, clone 10F.9G2, BioXCell; Lebanon, NH, USA), 100 µg each, were administered by intraperitoneal injection on days 4, 7, and 10. Mice were euthanized when tumor size exceeded 2000 mm3 in volume or when recommended by an independent animal health monitor due to morbidity or moribund behavior. Due to institutional radiation safety protocols and the use of multiple radioactive isotopes, all investigators were aware of mouse treatment groups. Delays in radioisotope shipments may have caused variation in tumor size on day 1. Therapy experiments were repeated in duplicate. The number of animals per group and average tumor size at treatment initiation are indicated in figure legends.

2.2.3. Toxicity and Immunoprofiling Studies

B78 tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells on both left and right flanks. At five weeks (~150–200 mm3), mice were randomized by tumor size. Treatment groups included 4 Gy, 4 Gy + ICI, 15 Gy, 15 Gy + ICI, and a cold dinutuximab + ICI control group. Mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation on D0 (n = 5; naïve control) and on days 4, 7, 14, and 21 (n = 4 per timepoint per treatment). Blood was collected for toxicity assessments and flow cytometry. Tumors from both flanks were either processed for flow cytometry or flash frozen in LN2 and stored until decay allowed for gene expression analysis.

2.3. Radiopharmaceuticals

90Y was purchased as 90YCl3 from Eckert and Ziegler (Valencia, CA, USA). 177Lu was purchased as 177LuCl3 from Shine Medical (Janesville, WI, USA) or Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Oak Ridge, TN, USA). 225Ac was obtained as solid 225Ac(NO3)3 from Oak Ridge National Laboratory. 89Zr was produced in a GE PETtrace cyclotron (University of Wisconsin–Madison) by irradiating natural yttrium foils (250 µm, 99.9%) with 13.8 MeV protons, as previously described [35]. Dinutuximab (Unituxin®, United Therapeutics; Silver Spring, MD, USA) was reconstituted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and purified using PD-10 desalting with PBS as the mobile phase. Chelators were conjugated to dinutuximab via exposed lysine residues using established protocols [36,37]. For 89Zr, p-SCN-Deferoxamine (DFO, Macrocyclics; Plano, TX, USA) was used; for 90Y and 177Lu, p-SCN-Bn-CHX-A″-DTPA (DTPA, Macrocyclics); for 225Ac, H2macropa-NCS (macropa) provided by Dr. Justin Wilson (Cornell University; Ithaca, NY, USA). As an actinide, 225Ac exhibits limited stability when coordinated with conventional chelators such as DOTA, often resulting in suboptimal radiolabeling efficiency and in vivo stability. In contrast, the novel chelator macropa has demonstrated markedly improved performance, characterized by higher radiochemical yield, radiochemical purity, specific activity, and serum stability, as well as enhanced tumor uptake in preclinical models [38,39,40,41]. DFO and DTPA were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO and mixed with dinutuximab at a 5:1 molar ratio; pH adjusted to ~8.5 using 0.1 M Na2CO3. Macropa was used at a 15:1 molar ratio and incubated overnight at 4 °C. DFO and DTPA reactions were incubated at room temperature for 1~4h. All conjugates were purified via PD-10 columns and concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter 30K MWCO (Merck; Darmstadt, Germany) at 4000 g for 15 min, then stored at 4 °C. For radiolabeling, 1M HEPES buffer was added to 89Zr for pH 7.5, 0.1M NaOAc buffer was added to 90Y for pH 5.5, 1M NaOAc buffer was added to 177Lu for pH 5.5, and 0.1M HEPES buffer with 0.4% v/v Tween-20 was added to 225Ac for pH 5.5. The neutralized radioisotopes were added to the antibody-chelator conjugate at a ratio of 0.1 mg of DFO-dinutuximab or DTPA-dinutuximab per 37 MBq of 89Zr, 90Y, and 177Lu. For 225Ac, 5 µg of macropa-dinutuximab conjugate was added per 37 kBq. Final volume was adjusted to 500 µL with buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Final products were purified by PD-10 columns and diluted in sterile PBS. For dose consistency, additional unlabeled dinutuximab was added to the low dose (4 Gy) formulations to match antibody content of high dose (15 Gy) formulations based on the apparent molar activities. Radiolabeling yield and purity were assessed via instant thin-layer chromatography using Perkin Elmer silica paper (iTLC-SA) and pH 8.0 50mM EDTA as solvent. Labeled antibody remained at the origin; free radiometals migrated with solvent. A Perkin Elmer Cyclone Plus image reader was used to analyze the chromatograms for quantifying labeling efficiency. For radiolabeling efficiency, n = 4 was performed for all radiolabeled isotopes.

2.4. PET/CT Imaging

Mice (n = 4) bearing B78 and B16 (~150 mm3) or 9464D and 9464D:GD2+ tumors (~150 mm3) were injected intravenously via tail vein with 9.25 MBq of 89Zr-dinutuximab. Imaging was performed at 3, 24, 72, and 168 h post injection using an Inveon microPET/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA). Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and placed prone on the scanner bed. Sequential CT (80 kVp; 1000 mAs; 220 angles) and static PET scans (80 million coincidence events; time window: 3.432 ns; energy window: 350–650 keV) were collected. A three-dimensional ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm was used to reconstruct the PET images. These were then fused with corresponding CT images for attenuation correction and anatomical referencing. Tumors were contoured for region-of-interest analysis to quantify 89Zr-dinutuximab uptake as %IA/g (mean ± SEM) and used for dosimetry.

2.5. SPECT/CT Imaging

Mice (n = 4) were injected intravenously with 18.5 MBq of 177Lu-dinutuximab and imaged using a MILabs U-SPECT6/CTUhr system (Houten, The Netherlands) at 24, 72, 168, and 336 h post-injection. Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and placed prone on a 4-mice multi bed. CT scans (10 min) were acquired for anatomical reference and attenuation correction and fused with the SPECT scans (45 min). Image reconstruction used a similarity-regulated ordered-subset expectation maximization (SROSEM) algorithm. Tumors were contoured for volumes-of-interest analysis and uptake quantified as %IA/g (mean ± SEM), used for dosimetry calculations.

2.6. Alpha Camera Imaging

Mice (n = 3) were injected via tail vein with 9.25 MBq 90Y-dinutuximab, 18.5 MBq 177Lu-dinutuximab, or 7.4 kBq 225Ac-dinutuximab. Mice were euthanized via CO2 at 72 h post-injection, and tumors harvested. Tumors were bisected and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound, frozen in −80 °C, and sectioned to 10 µm using a CM1950 cryostat (Leica; Deer Park, IL, USA). After sectioning, slides were placed against the iQID (QScint; Tucson, AZ, USA) detector window separated from the input window by a thin sheet of mylar (Ludlum Measurements 01-5859; Sweetwater, TX, USA) and the scintillator of choice depending on the radioisotope being scanned. For 225Ac-dinutuximab, a ZnS: Ag detector was used (Eljen Technology EJ-440; Sweetwater, TX, USA) and for 90Y- and 177Lu-dinutuximab, an image intensifying screen meant to detect low-and-medium-energy beta particles was used (Carestream BioMax TranScreen LE; Rochester, NY, USA). An in-house slide holder was used for experiments in order to fix scan bed position of the glass slides for subsequent image registration purposes between other imaging modalities. One scan was performed per slide and all lasted in duration depending on isotope; 1 h duration each for all 177Lu-dinutuximab scans, one 2.6 h and two 1 h scan durations for 90Y-dinutuximab scans, and one 1.9 h, one 4 h and one 1 h scan for 225Ac-dinutuximab.

2.7. Ex Vivo Biodistribution

Mice were injected intravenously with 7.4 kBq 225Ac-dinutuximab and euthanized at 3, 24, 72, and 168 h post-injection (n = 3/timepoint). Organs were harvested, weighed, and stored at 4 °C to reach secular equilibrium with 213Bi. Samples were analyzed using a Perkin Elmer Wizard2 (Westham, MA, USA) or Hidex AMG (Turku, Finland) gamma counter, with decay correction to calculate %IA/g.

2.8. Dosimetry Calculations

To estimate the mean absorbed dose of 225Ac-dinutuximab, organs of interest were collected from each mouse group at 3, 24, 72, and 168 h timepoints. Ex vivo biodistribution was measured at each timepoint as the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) using a gamma counter (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA, USA). Allometric scaling was first performed to estimate the intact organ mass with respect to body mass, assuming 20 g for all C57BL/6 mice. Cumulative activity (MBq-s/MBq_injected) in each organ was calculated by trapezoidal integration of the time activity curves, assuming physical decay only beyond the final timepoint. Absorbed dose to each organ was determined by multiplying the cumulative activity by the corresponding MIRD S-value (mGy/MBq-s) dose factors. S-values were derived assuming each organ as a liquid water sphere of equivalent mass receiving only self-dose. The total absorbed dose for each organ accounted for the full decay chain of 225Ac, considering negligible redistribution of the progenies. The redistribution and off-target accumulation of 225Ac daughter radionuclides remain an active area of investigation. Although we are not aware of a study that precisely matches our pharmaceutical construct and tumor model, a recent study using 225Ac-labeled PSMA ligands reported that the progeny of 225Ac-PSMA I&T is trapped in tumor tissue [42]. We acknowledge that some daughter redistribution (e.g., 213Bi) has been observed in other models, with accumulation reported in the kidneys, liver, or salivary glands via systemic circulation [43]. However, in our ex vivo biodistribution study measuring &IA/g (Figure 1E), we did not observe elevated uptake in the kidneys or liver, suggesting limited redistribution in our specific model. PET/CT- and SPET/CT-based dosimetry followed published methods [6,44,45]. %IA/g extrapolation and standard mouse models were used to convert cumulative activity to absorbed dose per injected activity (Gy/MBq). Dose contributions from surrounding organs were also included in calculations. For all absorbed dose calculations, we accounted for both the biological and physical half-lives of the radiopharmaceutical agents. Time-activity curves (TAC) were constructed using the serial measurements obtained either from imaging data or gamma counter-based quantification, depending on the experimental group. These data were used to estimate time-integrated activity coefficients for accurate dosimetry.

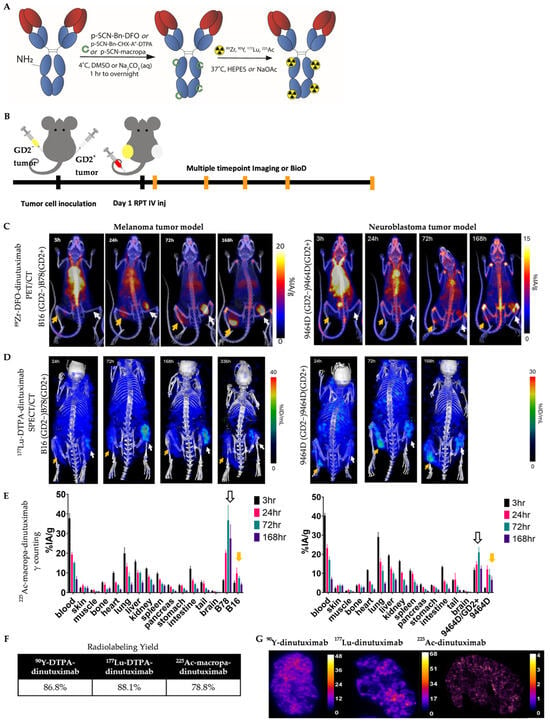

Figure 1.

Imaging, uptake, and distribution of 89Zr-DFO-dinutuximab, 177Lu-DTPA-dinutuximab, and 225Ac-macropa-dinutuximab. (A) Schematic representation of the radiolabeling process. The chimeric anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody dinutuximab was conjugated with the appropriate chelators labeled in green-deferoxamine (DFO) for 89Zr, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) for 177Lu, and macropa for 225Ac-via thiourea bond. Radiolabeling was performed under mild conditions (pH 5.5–7.0) for 1 h at 37 °C. (B) Bilateral tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice were used, with syngeneic GD2-negative (yellow arrow) and GD2-positive (white arrow) B16/B78 melanoma or 9464D/9464D:GD2+ neuroblastoma tumors implanted on the left and right flanks. Tumors were allowed to reach ~180 mm3 before radiopharmaceutical administration. (C) Longitudinal PET/CT imaging of mice injected with 89Zr-DFO-dinutuximab (∼9.25 MBq) was performed at 4, 24, 72, and 168 h post-injection. (D) Serial SPECT/CT imaging of 177Lu-DTPA-dinutuximab (∼18.5 MBq) was performed at 24, 72, 168, and 336 h post-injection. (E) For 225Ac-macropa-dinutuximab (∼7.4 kBq), quantitative ex vivo biodistribution was conducted at 4, 24, 72, and 168 h post-injection. Tissues were harvested, weighed, and radioactivity was measured via gamma counting of 213Bi emissions to estimate 225Ac decay products. (F) Radiochemical yields (n = 4) for each construct are summarized in a table format, as measured by iTLC. (G) Autoradiography of 90Y-, 177Lu-, and 225Ac-dinutuximab treated tumor sections. Cryosections were obtained at 20 µm thickness, exposed to phosphor screens, and imaged with an iQID scanner (QScint; Tucson, AZ, USA).

2.9. Toxicity Assessments

A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) and complete blood count (CBC) analyses were conducted for mice included in toxicity and immunoprofiling studies. All mice had 700 µL of blood collected via intracardiac puncture. CBC analysis was performed using whole blood collected in EDTA tubes and analyzed on a VetScan HM5 hematology analyzer (Abaxis; Union City, CA, USA). Serum was separated by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min, then analyzed using a VetScan VS2 analyzer (Abaxis). Samples not analyzed on the same day were stored at −20 °C and thawed on ice prior to analysis.

2.10. Radiopharmaceutical Therapy (RPT)

90Y-, 177Lu-, or 225Ac-dinutuximab therapy was administered via intravenous tail vein injection on treatment day 1 for all animal studies. Table 1 shows the injected activities corresponding to the prescribed tumor absorbed doses.

Table 1.

Injected activity of RPT for tumor absorbed dose prescriptions.

2.11. Gene Expression Analysis

Tumors were harvested and homogenized in Trizol using a Bead Mill Homogenizer Bead Ruptor Elite (Omni International; Kennesaw, GA, USA). Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN; Germantown, MD, USA) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TaqMan Fast Advanced qPCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher; Waltham, MA, USA). Thermal cycling conditions on the QuantStudio 6 (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA) were as follows: UDG activation at 50 °C for 2 min, Dual-Lock DNA polymerase activation stage at 95 °C for 2 min, then 40 PCR cycles—denaturation at 95 °C for 1 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 20 s. Ct values were exported to Excel, and fold changes normalized to untreated controls were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Hprt served as endogenous controls. A complete list of TaqMan probes is provided in Table S1. All qPCR experiments were performed in duplicate and presented as aggregate data.

2.12. Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described [46]. UltraComp eBeads fluorescent beads (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA) were used for compensation, and fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls were used for gating. Rainbow beads (Spherotech; Lake forest, IL, USA) were used to match voltages to D0 settings. For in vivo analyses, tumors, spleens, and tumor draining lymph nodes were harvested and dissociated using 70 µm Falcon cell strainers (Corning; Corning, NY, USA). Blood was collected via intracardiac puncture. Spleens and blood were treated with RBC lysis buffer (Biolegend; San Diego, CA, USA) and washed with PBS prior to staining. To prevent non-specific binding, cells were incubated with CD16/32 antibody (BioLegend). Live dead staining was performed using Ghost Red Dye 780 (Tonbo Biosciences; San Diego, CA, USA) per manufacturer’s instructions. Afterward, single-cell suspensions were labeled with surface antibodies at 4 °C for 30 min then washed three times with flow buffer (2% FBS + 2 mM EDTA in PBS). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and stained for internal markers with Cytofix/Cytoperm permeabilization solution (BD Biosciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry was conducted on a ThermoFisher Attune NxT Flow Cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo Software v10. A complete list of antibodies, clones, and fluorophores is provided in Table S2. All experiments were repeated in duplicate and presented as aggregate data.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Graphpad Prism 10 and R 4.4.2. Two-way ANOVA or multiple comparison tests using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test were applied to assess group differences in gene expression and flow cytometry data. For statistical analysis of microdosimetry results, separate linear models for each radionuclide were fit to estimate the effect of tumor type (melanoma vs. neuroblastoma) on required dose, adjusting for volume and prescription level. Arithmetic models used the raw required dose (µCi) as the outcome and geometric models used log-transformed required dose to estimate percent differences. For tumor growth analysis, all available data was used. For tumor growth and survival analysis, all available data was used (Figure S2). For experiments on varied radionuclides and ICI treatment, linear mixed models after log base 10 transformation of tumor volume were used with fixed effects covariates of radionuclide, time in weeks, and their interaction. Mouse ID was included as a random intercept. To compare radiation level, ICI, and antiGD2 treatment groups within each radionuclide, linear mixed models were again used, retaining log-transformed tumor volumes as the outcome and mouse ID as a random effect. The fixed effects were treatment group, time in weeks, and the interaction between treatment and time. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate differences in overall survival. Models were fit for each treatment group to estimate the differences between radionuclides. Then, additional models were fit for each radionuclide to estimate the differences by treatment group. All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise noted. For tumor growth and survival graphs, *, p < 0.03; **, p < 0.002; and ***, p < 0.001. For gene expression analysis and flow cytometry graphs, *, p < 0.03; **, p < 0.0021; ***, p < 0.0002; and ****, p < 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. Imaging, Uptake, and Distribution of 89Zr-DFO-, 177Lu-DTPA-, and 225Ac-Macropa-Dinutuximab

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the immunostimulatory potential of antibody-based RPT using different radionuclides in combination with ICIs. As a foundational step toward this goal, we first characterized the in vivo imaging, uptake, and distribution profiles of 89Zr-, 177Lu-, and 225Ac-dinutuximab in syngeneic murine models. Dinutuximab was conjugated with appropriate chelators and radiolabeled with each radionuclide (Figure 1A). Bilateral tumor models were established, with GD2-negative and GD2-positive melanoma or neuroblastoma tumors implanted on opposite flanks of each mouse (Figure 1B).

89Zr-labeled dinutuximab was used as a PET surrogate for 90Y-dinutuximab, consistent with its conventional role in theranostic applications [37,47]. The half-life of 89Zr (3.3 days) aligns more closely with 90Y (2.67 days) than other isotopes such as 86Y (0.618 days) [48,49]. Serial PET/CT imaging revealed preferential uptake of 89Zr-dinutuximab in GD2-positive tumors, consistent with target-specific binding. Similarly, 177Lu-dinutuximab demonstrated selective accumulation in GD2-positive tumors on SPECT/CT (Figure 1C,D) which was corroborated by ex vivo biodistribution at the final timepoint (Figure S1A). Both 89Zr- and 177Lu-dinutuximab showed progressive clearance from non-target tissues and sustained retention in tumors up to seven days post-injection.

Due to imaging limitations of alpha-emitters, ex vivo biodistribution was used to evaluate 225Ac-dinutuximab. Temporal biodistribution profiles indicatd consistent and prolonged accumulation in GD2-positive tumor tissue (Figure 1E). Radiochemical yields for all conjugates exceeded 80% as confirmed by iTLC (Figure 1F). Despite the limited penetration depth of monoclonal antibodies and the short path length of alpha particles, autoradiographic analysis suggests 225Ac-dinutuximab is distributed intratumorally (Figure 1G).

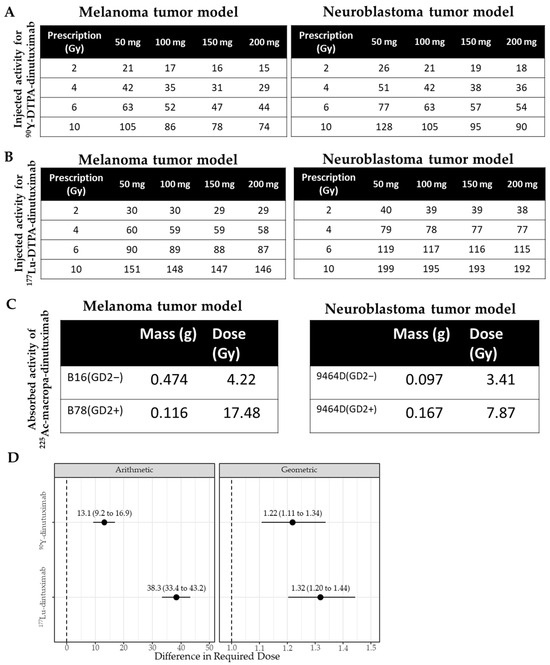

3.2. Dosimetry Highlights the Need for Absorbed Dose-Based RPT Evaluation

While injected activity remains the clinical standard for RPT dosing, it fails to account for inter-model variability in tumor uptake and radiation distribution [50,51,52,53]. To better reflect biological impact, voxel-based absorbed dose estimates were derived using longitudinal PET/CT or SPECT/CT data and a Monte Carlo-based dosimetry platform [45] (Figure 2A,B). Absorbed dose calculations revealed substantial differences between models, even when the same radiolabeled construct was used. For 225Ac-dinutuximab, tumor dose was estimated via its 213Bi daughter (t½ = 45.6 min), which enabled higher-resolution microscale dose modeling (Figure 2C). Overall, neuroblastoma tumors had a higher injected activity (µCi) required than melanoma tumors to achieve any equivalent tumor deposited dose (Figure 2D). For 90Y-dinutuximab, this was 22% greater (confidence interval 11–34%, p < 0.001) and for 177Lu-dinutuximab, this was 32% greater (20–40%, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Different microdosimetry results based on the same vector, radionuclide and chelator but in different tumor models. (A) Based on the absorbed dose estimates for the tumor with 89Zr-dinutuximab, a table was created to inform approximations for injected activity of 90Y-dinutuximab needed to deliver a prescribed dose to a tumor of different masses. (B) The required amount of injected activity (µCi) of 177Lu-dinutuximab to achieve a prescription absorbed dose (Gy) in a corresponding tumor mass (mg). (C) B16/B78 tumors received an absorbed dose of 21.1 and 87.4 Gy/µCi, and 9464D/9464D:GD2+ tumors received an absorbed dose of 17.1 and 39.3 Gy/µCi, respectively. For an injected activity of 0.2 µCi, the absorbed doses to the B16/B78 were 4.22 and 17.5 Gy and 9464D/9464D:GD2+ tumors were 3.41 and 7.87 Gy, respectively. (D) Statistical difference between required dose (µCi) in melanoma and neuroblastoma tumors under arithmetic and geometric considerations for 90Y- and 177Lu-dinutuximab. Dotted lines indicate the baseline.

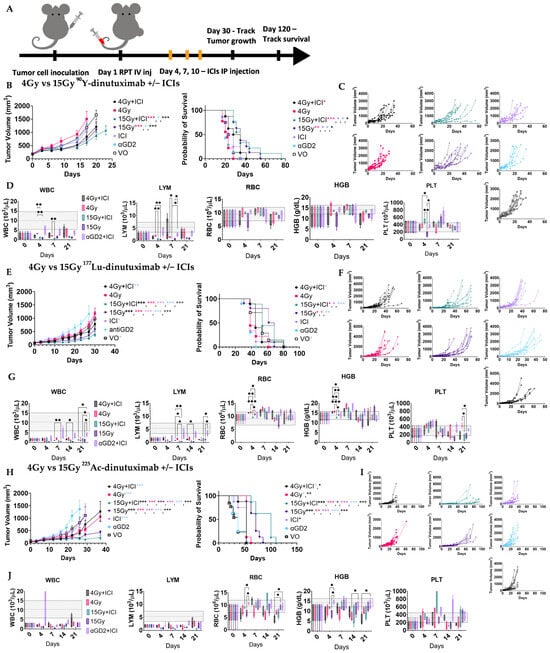

3.3. RPT and ICI Synergy Is Both Dose- and Radionuclide-Dependent

To evaluate the impact of absorbed dose on RPT–ICI synergy, mice received 90Y-, 177Lu-, or 225Ac-dinutuximab at doses corresponding to a low (4 Gy) or high (15 Gy) tumor absorbed dose. Injected activities to achieve these prescriptions were 1.369 MBq and 5.217 MBq for 90Y-dinutuximab, 2.22 MBq and 8.251 MBq for 177Lu-dinutuximab, and 1.702 kBq and 6.29 kBq for 225Ac-dinutuximab, respectively. These were administered with or without dual ICI therapy (anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1) on days 4, 7, and 10 (Figure 3). Control groups included saline and non-radiolabeled dinutuximab matched to the protein dose used in RPT groups. For both 90Y- and 177Lu-dinutuximab, 15 Gy groups with or without ICIs significantly improved survival (Figure 3B,C,E,F). 225Ac-dinutuximab led to survival improvement across all treatment arms, but the greatest benefit was observed in the 15 Gy + ICI group (Figure 3H,I). There was limited acute toxicity in both doses in all treatment groups (Figure 3D,G,J and Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic interaction between RPT + ICIs is dose-dependent and radionuclide-dependent. (A) Schematic of treatment schedule. B78 bearing mice (n = 8, 9) were randomized into groups and treated on Day 1 with either 90Y-, 177Lu-, or 225Ac-dinutuximab, unlabeled dinutuximab (aGD2) only, ICI only or saline (VO) with radiolabeled doses selected to deliver either 4 Gy (low dose) or 15 Gy (high dose) based on tumor-specific absorbed dose calculations. Anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) were administered intraperitoneally on Days 4, 7, and 10 in applicable groups. (B,C) Effects of 90Y-dinutuximab dose on tumor growth and overall survival. (D) Complete blood counts on days 0, 4, 7, 21. WBC: white blood cells, LYM: lymphocytes, PLT: platelets, HGB: hemoglobin, RBC: red blood cells. Gray box indicates normal range of respective values in mice. (E,F) Effects of 177Lu-dinutuximab dose on tumor growth and overall survival. (G) Complete blood counts on days 0, 4, 7, 14, 21. (H,I) Effects of 225Ac-dinutuximab dose on tumor growth and overall survival. (J) Complete blood counts on days 0, 4, 7, 14, 21.

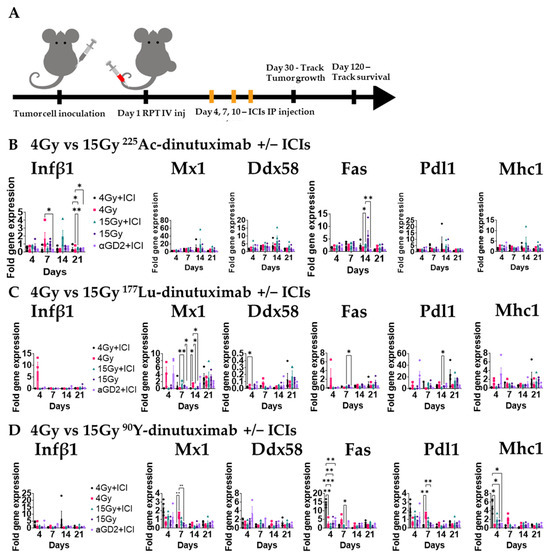

3.4. 225Ac-Dinutuximab Induces Sustained Type I Interferon Responses

We next examined how different radionuclides affect the in vivo type I interferon (IFN-I) response. Mice bearing bilateral B78 tumors were treated with 90Y-, 177Lu-, or 225Ac-dinutuximab and ICIs as described above (Figure 4A). Tumors were harvested at days 4, 7, 14, and 21 for qPCR analysis. 225Ac-dinutuximab elicited higher and more sustained expression of Ifnb1 and Fas at later timepoints (Figure 4B), suggesting prolonged immunostimulatory activity. In contrast, 90Y-dinutuximab induced earlier peaks in Mx1, Fas, Pdl1, and Mhc1 expression and 177Lu-dinutuximab exhibited only moderate upregulation of Mx1, Pdl1, and Mhc1 (Figure 4C,D). The prolonged IFN-I activation observed in the 15 Gy 225Ac-dinutuximab plus ICI group may contribute to the favorable immunologic milieu for dendritic cell recruitment and effective checkpoint blockade [54,55] (Figure S6H).

Figure 4.

In vivo type I IFN response is activated with 225Ac-dinutuximab as compared to 90Y- or 177Lu-dinutuximab. (A) Experimental timeline for gene expression analysis. B78 bearing mice with bilateral flank tumors were treated on Day 1 with either 90Y-, 177Lu-, or 225Ac-dinutuximab, or unlabeled dinutuximab. Mice receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs; anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4) were dosed on Days 4, 7, and 10. Tumors were harvested on Days 4, 7, 14, and 21 (n = 4/timepoint) for gene expression profiling. (B) In vivo qPCR results following 225Ac-dinutuximab. qPCR was used to quantify gene expression and is reported as fold changed normalized to untreated controls (Day 0, n = 5) performed in duplicates. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to compare fold change in expression between treatment groups. (C) In vivo qPCR results following 177Lu-dinutuximab. (D) In vivo qPCR results following 90Y-dinutuximab.

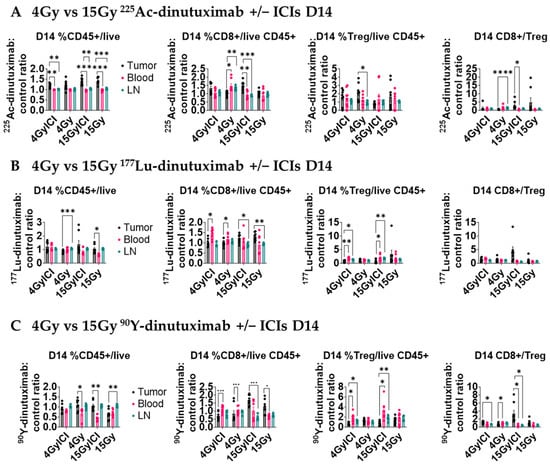

3.5. 15 Gy 90Y- and 225Ac-Dinutuximab Enhance CD8+ T Cell Infiltration and CD8+/Treg Ratio

Given the role of IFN-I in priming CD8+ T cell responses [54], we investigated the downstream effects of IFN-1 signaling on the tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) population following RPT. Using the same B78-bearing mice as for the qPCR experiments above, we investigated the immune cell composition of host immune organs (blood and tumor-draining inguinal lymph node) and disaggregated tumor tissue compared to control mice by flow cytometry. All data were normalized to the control mice treated with unlabeled dinutuximab combined with ICIs. The day 14 CD45+, CD8+, regulatory T cell (Treg), and CD8+/Treg ratio are reported for all of the tissues following injection on day 1 (Figure 5). In Figures S4–S6, CD45+, CD8+, regulatory T cell (Treg), CD8+/Treg ratio, %PD1+ CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, NK cells, CD11b+ cells, M1- and M2-like macrophages, and dendritic cells are reported at days 3, 7, 14, and 21 are reported for same treatment groups and tissues. The CD8+/Treg ratio significantly increased (p > 0.05) in tumor microenvironment relative to other tissues with 15 Gy + ICI 225Ac- and 90Y-dinutuximab groups (Figure 5A,C). Notably, a significant change in CD8+ frequency was observed in the tumor for these groups (225Ac-dinutuximab tumor: blood, p < 0.005; lymph node, p < 0.001 and 90Y-dinutuximab tumor: lymph node, p < 0.0001). This finding suggests that the limited tissue penetration capacity of the monoclonal antibody may stimulate the composition of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment at high-dose compared to the low-dose small-molecule RPT [4,7,8]. In addition, 15 Gy 225Ac-dinutuximab with ICIs significantly increased the frequency of dendritic cells in the tumor microenvironment relative to the tumor draining lymph node (p < 0.005) on D21 correlative to IFN-1 activation (Figure S6H).

Figure 5.

15 Gy of 90Y- or 225Ac-dinutuximab potentiates immune response when combined with ICIs. (A–C) Quantification of tumor-infiltrating and systemic immune populations on Day 14 following RPT ± ICI treatment. All mice treatment groups are the same as Figure 4. Mice were euthanized and tumor tissue, blood, and draining inguinal lymph nodes were collected for flow cytometric analysis. Cell populations were normalized to those from mice treated with unlabeled dinutuximab + ICIs and performed in duplicates. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to compare treatment groups. (A) Flow cytometry data in the tumor microenvironment for 225Ac-dinutuximab treatment groups. (B) Flow cytometry data in the tumor microenvironment for 177Lu-dinutuximab treatment groups. (C) Flow cytometry data in the tumor microenvironment for 90Y-dinutuximab treatment groups.

4. Discussion

In this study, we present in vivo quantitative imaging and dosimetry data for 90Y-, 177Lu-, and 225Ac-labeled dinutuximab in syngeneic melanoma (B16/B78) and neuroblastoma (9464D/9464D:GD2+) models. In the melanoma model, survival was significantly improved with absorbed dose-matched 15 Gy administration of all three RPTs. However, only 225Ac-dinutuximab demonstrated a significant additive survival benefit when combined with ICIs. Our immunophenotyping and gene expression data further correlated these survival trends with distinct longitudinal changes in tumor and systemic immune cell composition.

The cooperative therapeutic interaction between RPT and ICIs is critically dependent on both the delivery mechanism and microdosimetric distribution. Antibody-based RPT exploits antigen specificity to preferentially deliver ionizing radiation to malignant tissues while minimizing off-target toxicity. In our case, dinutuximab’s affinity for GD2 [15,17] facilitated selective tumor uptake across all conjugated radionuclides. Nevertheless, the restricted tissue penetration of full-length antibodies, coupled with the inherently short range of α-particles, results in a more pronounced peak-to-valley radiation distribution within tumors compared with β-particle emitters (Figure S7). This dose heterogeneity is known to influence therapeutic outcomes [56] and may explain the superior results observed with 15 Gy of 225Ac-dinutuximab combined with ICIs. Importantly, emerging evidence suggests that such heterogeneity may not be purely detrimental. As shown in previous brachytherapy studies [57], dose distributions that preserve low-dose regions within the tumor microenvironment (TME) may be critical for sustaining immune activity, particularly dendritic cell function and migration. In line with this, Patel et al. demonstrated that in the B78 melanoma model treated with the small molecule RPT NM600, immune stimulation was optimal at ~2 Gy but diminished at 5 Gy, underscoring the importance of low-dose regions for productive antitumor immunity [4].

Although α-particles have a limited range (<100 μm) in tissues, their high linear energy transfer (LET) enables them to induce dense, irreparable DNA double-strand breaks, which are highly immunogenic [58]. In our experiments, 90Y-dinutuximab treatment led to early upregulation of antigen presentation (Mhc1, Pdl1) and apoptotic markers (Fas). In contrast, 225Ac-dinutuximab produced a more prolonged IFN- I response, a critical mediator of antitumor immunity through its enhancement of dendritic cell activation and CD8+ T cell infiltration [59,60]. This was corroborated by flow cytometry, which demonstrated that the 15 Gy 225Ac-dinutuximab + ICI group showed the highest CD8+/Treg ratio and dendritic cell recruitment within the tumor microenvironment by day 21, consistent with the strongest observed survival benefit. However, 177Lu-dinutuximab did not demonstrate the same degree of early upregulation observed with 90Y-dinutuximab, despite both radionuclides being β-emitters. This disparity may be attributable to the lower maximum β energy and substantially shorter tissue penetration of 177Lu (0.5 MeV; ~1.5–2 mm) relative to 90Y (2.28 MeV; ~11 mm) [61], which results in more spatially confined tumor cell injury and may consequently attenuate or delay immunomodulatory signaling without achieving the effective dose heterogeneity observed with 225Ac (Figure S7). Furthermore, previous reports indicate that 90Y induces broader tumor and stromal disruption, facilitating the release of tumor-associated antigens and danger-associated molecular patterns, thereby promoting more rapid and pronounced immune activation [62,63].

Our results strongly suggest that administered activity alone (e.g., in MBq or µCi) is an inadequate predictor of therapeutic outcome, particularly when the goal is to stimulate an immune response. Tumor-specific factors such as antigen density, vascularity, and microenvironmental composition significantly influence the actual absorbed dose. Our voxel-based Monte Carlo dosimetry revealed considerable variability in tumor absorbed dose between models and radionuclides, despite equal injected activities. These findings reinforce the necessity of individualized dosimetry to guide therapeutic decision-making and accurately interpret treatment outcomes. However, implementing patient-specific dosimetry in the clinical setting presents several challenges. Accurate dosimetry requires multiple timepoint imaging sessions—typically via PET or SPECT—over a span of several days. While feasible in preclinical models, this approach imposes substantial logistical, financial, and radiation exposure burdens in human patients [50]. Multiple imaging appointments, prolonged scanner occupancy, and radiopharmaceutical accessibility across timepoints pose barriers in many clinical environments. These are compounded by vulnerable populations, including pediatric, elderly, or terminally ill patients. As a result, clinical protocols often default to empiric or fixed dosing regimens, which risk under- or over-treating individuals. To address this gap, there is an urgent need for streamlined and clinically viable dosimetry methods—such as single-timepoint dose estimation, machine learning-based modeling, or surrogate imaging biomarkers [64,65]. These strategies could reduce the patient burden while maintaining sufficient precision for dose optimization.

We acknowledge the limitations of using murine models, which do not fully recapitulate the complexity of human tumors or immune systems [66]. While these models are indispensable for mechanistic and early translational studies, further validation in large-animal models and clinical trials will be necessary to confirm the therapeutic implications of our findings. Another limitation is that despite their advantages, radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies are underrepresented in clinical RPT protocols compared to small molecules or antibody fragments [67]. This is at least partially attributable to their large size, which restricts tumor penetration and promotes dose heterogeneity [18]. As such, optimizing delivery strategies through alternative formats like minibodies or bispecific antibodies remains a critical area of future research [53,68]. Lastly, although 225Ac-dinutuximab demonstrated robust immunostimulatory activity, only a single α-emitting radionuclide was evaluated. As such, it remains premature to conclude that 225Ac is categorically superior to β-emitting constructs. Inclusion of additional α-emitters with distinct physical properties—such as 212Pb or 149Tb—would provide a more comprehensive assessment of α-particle–mediated therapeutic efficacy.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the delivery mechanism and resulting microdosimetry of radiopharmaceutical therapy are central to achieving effective synergy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Our findings show that functionally distinct immune outcomes can arise even when using the same antibody vector, emphasizing the critical role of radionuclide properties—particularly radiation type, LET, and spatial distribution—in shaping tumor immunogenicity.

We confirm that dinutuximab selectively targets GD2-positive tumors and supports the sustained intratumoral retention of radiolabeled agents. However, the immunological and survival outcomes varied markedly depending on the radionuclide used. The short-range, high-LET emission of 225Ac enabled localized immune priming, resulting in the most robust IFN-I responses, CD8+ T cell infiltration, and dendritic cell recruitment—key hallmarks of successful immunotherapy. In contrast, β-emitters like 90Y and 177Lu produced less pronounced or more transient effects in our models, despite equivalent injected activities.

Our voxel-based dosimetry analysis revealed that injected activity does not correlate directly with tumor-absorbed dose, underscoring the inadequacy of current empirical dosing paradigms. Instead, personalized dosimetry is necessary to optimize immunological outcomes and therapeutic efficacy. This biologically guided approach enables a more accurate interpretation of treatment responses and the design of more effective combination protocols.

We suggest that for combined modality treatments with RPT and immunotherapies, RPT microdosimetry is a biological imperative. Sub-therapeutic or poorly distributed radiation may not only fail to activate immune pathways but may also contribute to immune suppression or resistance. Because antibody-based RPT is limited by tissue penetration and spatial heterogeneity, understanding different tumor heterogeneity is crucial for maximizing therapeutic benefit—particularly in combination with immunomodulators.

Together, these results advocate for a paradigm shift from standardized dosing to biologically informed, individualized RPT planning. Integrating personalized microdosimetry into both preclinical and clinical studies will be essential for realizing the full potential of RPT and ICI combinations in precision oncology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/radiation5040039/s1: Figure S1: Biodistribution of 89Zr-dinutuximab in melanoma and neuroblastoma murine models; Figure S2: Statistical tests performed on survival and tumor growth curves; Figure S3: Acute toxicity profile of 177Lu and 225Ac-dinutuximab; Figure S4: 90Y-dinutuximab tumor immune cell composition in tumor microenvironment; Figure S5: 177Lu-dinutuximab tumor immune cell composition in tumor microenvironment; Figure S6: 225Ac-dinutuximab tumor immune cell composition in tumor microenvironment; FigureS7: Activity map distribution of sectional slices of tumor treated with 90Y-, 177Lu-, and 225Ac-dinutuximab from Figure 1G; Table S1: List of TaqMan probes utilized for quantitative RT-PCR experiments; Table S2: List of flow cytometry antibody targets, clones, and fluorophores.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H., Z.S.M., and J.P.W.; methodology, C.P.K., C.A.F., J.J.G., and A.K.E.; validation, Z.S.M., and J.P.W.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, C.L., J.Z., O.K., and A.O.A.; resources, J.Z., O.K., A.O.A., H.C.R., M.B.I., P.A.C., W.J.J., A.K.E., E.A.-S., T.K., J.J.W., J.W.E., R.H., B.B., Z.S.M., and J.P.W.; data curation, C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.S.M. and J.P.W.; visualization, C.L.; supervision, J.P.W.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, Z.S.M., and J.P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the University of Wisconsin–Madison Carbone Cancer Center (CCC) Flow Cytometry Laboratory and Small Animal Imaging and Radiotherapy Facility (SAIRF) for technical support. This project was supported, in part, through the NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI), grant P01CA250972. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors would like to acknowledge the CCC Support Grant: NCI P30 CA014520 and SAIRF MiLabs microSPECT/CT SIG: NIH S10OD028670-01 for supporting this work. Funding for C.L. was provided in part by PhRMA Foundation Drug Delivery Predoctoral Fellowship. Research by TK and JJW was supported by the National Institutes of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under the award number R56EB029259.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All mouse studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (protocol: M005853, approved: 4/23/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 225Ac | Actinium-225 |

| 89Zr | Zirconium-89 |

| 90Y | Yttrium-90 |

| 177Lu | Lutetium-177 |

| Ab | Antibody |

| B78 | Murine melanoma cell line |

| CD4 | Cluster of Differentiation 4 (helper T cell marker) |

| CD8 | Cluster of Differentiation 8 (cytotoxic T cell marker) |

| CD11b | Cluster of Differentiation 11b (myeloid cell marker) |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 |

| DFO | Desferrioxamine |

| DTPA | Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid |

| Fas | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily Member 6 (apoptosis marker) |

| GD2 | Disialoganglioside 2 |

| Gy | Gray (unit of absorbed dose) |

| γH2AX | Phosphorylated Histone H2AX (marker of DNA damage) |

| ICI | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| IFN | Interferon |

| kBq | Kilobecquerel |

| MBq | Megabecquerel |

| MHC I | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I |

| mAb | Monoclonal Antibody |

| MX1 | Myxovirus Resistance Protein 1 (Type I IFN response marker) |

| NK | Natural Killer (cell) |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RPT | Radiopharmaceutical Therapy |

| SPECT | Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cell |

References

- Sgouros, G. Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. Health Phys. 2019, 116, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decazes, P.; Bohn, P. Immunotherapy by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Nuclear Medicine Imaging: Current and Future Applications. Cancers 2020, 12, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinendorst, S.C.; Oosterwijk, E.; Bussink, J.; Westdorp, H.; Konijnenberg, M.W.; Heskamp, S. Combining targeted radionuclide therapy and immune checkpoint inhibition for cancer treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 3652–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.B.; Hernandez, R.; Carlson, P.; Grudzinski, J.; Bates, A.M.; Jagodinsky, J.C.; Erbe, A.; Marsh, I.R.; Arthur, I.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; et al. Low-dose targeted radionuclide therapy renders immunologically cold tumors responsive to immune checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, R.; Walker, K.L.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; Patel, R.; Zahm, C.D.; Pinchuk, A.N.; Massey, C.F.; Bitton, A.N.; Brown, R.J.; et al. Y-NM600 targeted radionuclide therapy induces immunologic memory in syngeneic models of T-cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; Massey, C.F.; Pinchuk, A.N.; Bitton, A.N.; Patel, R.; Zhang, R.; Rao, A.V.; Iyer, G.; et al. Lu-NM600 Targeted Radionuclide Therapy Extends Survival in Syngeneic Murine Models of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C.P.; Sheehan-Klenk, J.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Adam, D.P.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Ferreira, C.A.; Bates, A.M.; Jin, W.J.; Kwon, O.; Olson, A.P.; et al. The effects of clinically relevant radionuclides on the activation of an ifn1 response correlate with radionuclide half-life and linear energy transfer and influence radiopharmaceutical antitumor efficacy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2025, 13, 1190–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C.P.; Jin, W.J.; Liu, P.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Ferreira, C.A.; Rojas, H.C.; Oñate, A.J.; Kwon, O.; Hyun, M.; Idrissou, M.B.; et al. Priming versus propagating: Distinct immune effects of an alpha- versus beta-particle emitting radiopharmaceutical when combined with immune checkpoint inhibition. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Sam, S.L.; Koshkin, V.; Small, E.; Feng, F.; Kouchkovsky, I.; Kwon, D.; Friedlander, T.; Borno, H.; Bose, R.; et al. Immunogenic priming with 177Lu-PSMA-617 plus pembrolizumab in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): A phase 1b study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Hofman, M.; Stockler, M.; Martin, A.; Pokorski, I.; Goh, J.; Pattison, D.; Dhiantravan, N.; Gedye, C.; et al. Evolution: Phase II study of radionuclide 177Lu-PSMA-617 therapy versus 177Lu-PSMA-617 in combination with ipilimumab and nivolumab for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC.; ANZUP 2001). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, TPS271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Hetzheim, H.; Kratochwil, C.; Benesova, M.; Eder, M.; Neels, O.C.; Eisenhut, M.; Kübler, W.; Holland-Letz, T.; Giesel, F.L.; et al. The Theranostic PSMA Ligand PSMA-617 in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer by PET/CT: Biodistribution in Humans, Radiation Dosimetry, and First Evaluation of Tumor Lesions. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, K.M.; Johnson, C.E.; Williams, C.J. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 62, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, L.; Theodorescu, D. Determinants of Resistance to Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taunk, N.K.; Escorcia, F.E.; Lewis, J.S.; Bodei, L. Radiopharmaceuticals for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy: New Targets, New Therapies-Alpha-Emitters, Novel Targets. Cancer J. 2024, 30, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazha, B.; Inal, C.; Owonikoko, T.K. Disialoganglioside GD2 Expression in Solid Tumors and Role as a Target for Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machy, P.; Mortier, E.; Birklé, S. Biology of GD2 ganglioside: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1249929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achbergerová, M.; Hederová, S.; Hrašková, A.; Kolenová, A. Dinutuximab beta in the treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma: A follow-up of a case series in Bratislava. Medicine 2022, 101, e28716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Tannock, I.F. The distribution of the therapeutic monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and trastuzumab within solid tumors. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiljo, J.; Harpain, F.; Carotta, S.; Bergmann, M. Radiotherapy as a Backbone for Novel Concepts in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2019, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shao, C. Radiotherapy-Mediated Immunomodulation and Anti-Tumor Abscopal Effect Combining Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancers 2020, 12, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kong, L.; Shi, F.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J. Abscopal effect of radiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C.P.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Nguyen, T.P.; Hernandez, R.; Weichert, J.P.; Morris, Z.S. Developments in Combining Targeted Radionuclide Therapies and Immunotherapies for Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, M.C.; Patel, R.B.; Anderson, C.J. Combined Targeted Radiopharmaceutical Therapy and Immune Checkpoint Blockade: From Preclinical Advances to the Clinic. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 1636–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.B.; Bear, H.; Prabhakaran, S.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Thomas, A.; Cobain, E.; McArthur, H.; Balko, J.M.; Gameiro, S.R.; Nanda, R.; et al. Two may be better than one: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade combination approaches in metastatic breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, X.; Hu, Y. Iodine-125 seed brachytherapy combined with pembrolizumab for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of first-line chemotherapy: A report of two cases and literature review. J. Contemp. Brachytherapy 2023, 15, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodinsky, J.C.; Vera, J.M.; Jin, W.J.; Shea, A.G.; Clark, P.A.; Sriramaneni, R.N.; Havighurst, T.C.; Chakravarthy, I.; Allawi, R.H.; Kim, K.; et al. Intratumoral radiation dose heterogeneity augments antitumor immunity in mice and primes responses to checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadk0642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.R.; Barsoumian, H.; Verma, V.; Cortez, M.A.; Welsh, J.W. Low-Dose Radiation Decreases Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and May Increase T-Cell Trafficking into Tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108, e530–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, M.; Yamashiro, S.; Yamamoto, A.; Furukawa, K.; Takamiya, K.; Lloyd, K.O.; Shiku, H. Isolation of GD3 synthase gene by expression cloning of GM3 alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase cDNA using anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 10455–10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmilevich, A.L.; Imboden, M.; Hao, Z.; Macklin, M.D.; Roberts, T.; Wright, K.M.; Albertini, M.R.; Yang, N.S.; Sondel, P.M. Effective particle-mediated vaccination against mouse melanoma by coadministration of plasmid DNA encoding Gp100 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 952–961. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.C.; Varki, N.; Gillies, S.D.; Furukawa, K.; Reisfeld, R.A. An antibody-interleukin 2 fusion protein overcomes tumor heterogeneity by induction of a cellular immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 7826–7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, T.J.; Komjathy, D.; Rodriguez, M.; Stuckwisch, A.; Feils, A.; Subbotin, V.; Birstler, J.; Gillies, S.D.; Rakhmilevich, A.L.; Erbe, A.K.; et al. Short-course neoadjuvant in situ vaccination for murine melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voeller, J.; Erbe, A.K.; Slowinski, J.; Rasmussen, K.; Carlson, P.M.; Hoefges, A.; VandenHeuvel, S.; Stuckwisch, A.; Wang, X.; Gillies, S.D.; et al. Combined innate and adaptive immunotherapy overcomes resistance of immunologically cold syngeneic murine neuroblastoma to checkpoint inhibition. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, M.D.; Burkhart, C.A.; Marshall, G.M.; Weiss, W.A.; Haber, M. Expression of N-myc and MRP genes and their relationship to N-myc gene dosage and tumor formation in a murine neuroblastoma model. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2000, 35, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, T.J.; Erbe, A.K.; Zebertavage, L.; Komjathy, D.; Feils, A.S.; Rodriguez, M.; Stuckwisch, A.; Gillies, S.D.; Morris, Z.S.; Birstler, J.; et al. Mechanism of effective combination radio-immunotherapy against 9464D-GD2, an immunologically cold murine neuroblastoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Sun, H.; England, C.G.; Valdovinos, H.F.; Ehlerding, E.B.; Barnhart, T.E.; Yang, Y.; Cai, W. CD146-targeted immunoPET and NIRF Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with a Dual-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1918–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, C.G.; Jiang, D.; Ehlerding, E.B.; Rekoske, B.T.; Ellison, P.A.; Hernandez, R.; Barnhart, T.E.; McNeel, D.G.; Huang, P.; Cai, W. 89Zr-labeled nivolumab for imaging of T-cell infiltration in a humanized murine model of lung cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, C.G.; Ehlerding, E.B.; Hernandez, R.; Rekoske, B.T.; Graves, S.A.; Sun, H.; Liu, G.; McNeel, D.G.; Barnhart, T.E.; Cai, W. Preclinical Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution Studies of 89Zr-Labeled Pembrolizumab. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobba, K.N.; Bidkar, A.P.; Meher, N.; Fong, C.; Wadhwa, A.; Dhrona, S.; Sorlin, A.; Bidlingmaier, S.; Shuere, B.; He, J.; et al. Evaluation of 134Ce/134La as a PET Imaging Theranostic Pair for 225Ac α-Radiotherapeutics. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, C.W.; Morgan, K.A.; Cao, Z.; Osellame, L.D.; Guo, N.; Gan, H.; Reilly, E.; Burvenich, I.J.G.; O’Keefe, G.J.; Donnelly, P.S.; et al. Radiolabeling and Preclinical Evaluation of Therapeutic Efficacy of (225)Ac-ch806 in Glioblastoma and Colorectal Cancer Xenograft Models. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, C.A.; Zitzmann-Kolbe, S.; Moen, I.; Klotz, M.; Nair, S.; Stargard, S.; Bjerke, R.M.; Wickstrøm Biseth, K.; Feng, Y.Z.; Indrevoll, B.; et al. Preclinical Efficacy of a PSMA-Targeted Actinium-225 Conjugate (225Ac-Macropa-Pelgifatamab): A Targeted Alpha Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, N.A.; Brown, V.; Kelly, J.M.; Amor-Coarasa, A.; Jermilova, U.; MacMillan, S.N.; Nikolopoulou, A.; Ponnala, S.; Ramogida, C.F.; Robertson, A.K.H.; et al. An Eighteen-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand for Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 14712–14717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzer, A.; Sun, B.; Saleh, S.; Brosch-Lenz, J.; Fischer, S.; Kossatz, S.; Hürkamp, K.; Li, W.B.; Eiber, M.; Morgenstern, A.; et al. [225Ac]Ac-PSMA I&T: A Preclinical Investigation on the Fate of Decay Nuclides and Their Influence on Dosimetry of Salivary Glands and Kidneys. J. Nucl. Med. 2025, 66, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Merkx, R.I.J.; Rijpkema, M.; Franssen, G.M.; Kip, A.; Smeets, B.; Morgenstern, A.; Bruchertseifer, F.; Yan, E.; Wheatcroft, M.P.; Oosterwijk, E.; et al. Carbonic Anhydrase IX-Targeted α-Radionuclide Therapy with 225Ac Inhibits Tumor Growth in a Renal Cell Carcinoma Model. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besemer, A.E.; Yang, Y.M.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Hall, L.T.; Bednarz, B.P. Development and Validation of RAPID: A Patient-Specific Monte Carlo Three-Dimensional Internal Dosimetry Platform. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2018, 33, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarz, B.; Grudzinski, J.; Marsh, I.; Besemer, A.; Baiu, D.; Weichert, J.; Otto, M. Murine-specific Internal Dosimetry for Preclinical Investigations of Imaging and Therapeutic Agents. Health Phys. 2018, 114, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.J.; Erbe, A.K.; Schwarz, C.N.; Jaquish, A.A.; Anderson, B.R.; Sriramaneni, R.N.; Jagodinsky, J.C.; Bates, A.M.; Clark, P.A.; Le, T.; et al. Tumor-Specific Antibody, Cetuximab, Enhances the In Situ Vaccine Effect of Radiation in Immunologically Cold Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 591139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verel, I.; Visser, G.W.; Boellaard, R.; Boerman, O.C.; van Eerd, J.; Snow, G.B.; Lammertsma, A.A.; van Dongen, G.A. Quantitative 89Zr immuno-PET for in vivo scouting of 90Y-labeled monoclonal antibodies in xenograft-bearing nude mice. J. Nucl. Med. 2003, 44, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis, B.; Lewis, J. The bioconjugation and radiosynthesis of 89Zr-DFO-labeled antibodies. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2015, 96, 52521. [Google Scholar]

- Rösch, F.; Herzog, H.; Qaim, S. The Beginning and Development of the Theranostic Approach in Nuclear Medicine, as Exemplified by the Radionuclide Pair 86Y and 90Y. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G. Dosimetry, Radiobiology and Synthetic Lethality: Radiopharmaceutical Therapy (RPT) With Alpha-Particle-Emitters. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2020, 50, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, S.A.; Hobbs, R.F. Dosimetry for Optimized, Personalized Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 31, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, J.; Zanzonico, P.; Humm, J.; Kesner, A. Dosimetry in Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St James, S.; Bednarz, B.; Benedict, S.; Buchsbaum, J.C.; Dewaraja, Y.; Frey, E.; Hobbs, R.; Grudzinski, J.; Roncali, E.; Sgouros, G.; et al. Current Status of Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Gerber, S.A.; Murphy, S.P.; Lord, E.M. Type I interferons induced by radiation therapy mediate recruitment and effector function of CD8(+) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, B.C.; Liang, H.; Lee, Y.; Chlewicki, L.; Khodarev, N.N.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Fu, Y.X.; Auh, S.L. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type i interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2488–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, M.E.; Berg, T.J.; Morris, Z.S. The Effects of Radiation Dose Heterogeneity on the Tumor Microenvironment and Anti-Tumor Immunity. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 34, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodinsky, J.C.; Jin, W.J.; Bates, A.M.; Hernandez, R.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Marsh, I.R.; Chakravarty, I.; Arthur, I.S.; Zangl, L.M.; Brown, R.J.; et al. Temporal analysis of type 1 interferon activation in tumor cells following external beam radiotherapy or targeted radionuclide therapy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6120–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danforth, J.M.; Provencher, L.; Goodarzi, A.A. Chromatin and the Cellular Response to Particle Radiation-Induced Oxidative and Clustered DNA Damage. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 910440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Alard, A.; Aryankalayil, M.J.; Sarfraz, Y.; Diamond, J.M.; Schneider, R.J.; Inghirami, G.; Coleman, C.N.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.R.; Fuertes, M.B.; Corrales, L.; Spranger, S.; Furdyna, M.J.; Leung, M.Y.; Duggan, R.; Wang, Y.; Barber, G.N.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity 2014, 41, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Jakobsson, V.; Greifenstein, L.; Khong, P.-L.; Chen, X.; Baum, R.P.; Zhang, J. Alpha-peptide receptor radionuclide therapy using actinium-225 labeled somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1034315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccelli, L.; Boschi, A.; Cittanti, C.; Martini, P.; Panareo, S.; Tonini, E.; Nieri, A.; Urso, L.; Caracciolo, M.; Lodi, L.; et al. 90Y/177Lu-DOTATOC: From Preclinical Studies to Application in Humans. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, V.; Lee, Y.H.; Pan, L.; Nasir, N.J.M.; Lim, C.J.; Chua, C.; Lai, L.; Hazirah, S.N.; Lim, T.K.H.; Goh, B.K.P.; et al. Immune activation underlies a sustained clinical response to Yttrium-90 radioembolisation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2019, 68, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.F.; Wahl, R.L.; Frey, E.C.; Kasamon, Y.; Song, H.; Huang, P.; Jones, R.J.; Sgouros, G. Radiobiologic optimization of combination radiopharmaceutical therapy applied to myeloablative treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungberg, M.; Celler, A.; Konijnenberg, M.W.; Eckerman, K.F.; Dewaraja, Y.K.; Sjögreen-Gleisner, K.; Bolch, W.E.; Brill, A.B.; Fahey, F.; Fisher, D.R.; et al. MIRD Pamphlet No. 26: Joint EANM/MIRD Guidelines for Quantitative 177Lu SPECT Applied for Dosimetry of Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wege, A.K. Humanized Mouse Models for the Preclinical Assessment of Cancer Immunotherapy. BioDrugs 2018, 32, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, A.G.; Idrissou, M.B.; Torres, A.I.; Chen, T.; Hernandez, R.; Morris, Z.S.; Sodji, Q.H. Immunological effects of radiopharmaceutical therapy. Front. Nucl. Med. 2024, 4, 1331364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Roncali, E.; Hobbs, R.; James, S.S.; Bednarz, B.; Benedict, S.; Dewaraja, Y.K.; Frey, E.; Grudzinski, J.; Sgouros, G.; et al. Toward Individualized Voxel-Level Dosimetry for Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).