Abstract

Tourism is a rapidly growing sector in Kazakhstan, yet Almaty city and its surrounding region have experienced stagnant growth despite rich natural and cultural assets. This study identifies governance-related barriers that impede sustainable tourism development and effective stakeholder participation. Using a mixed-methods design centered on semi-structured interviews with stakeholders from government, business, NGOs (Non-Governmental Organization), and community organizations conducted in 2018 and 2024, and supplemented by PEST (Political, Economic, Sociocultural, and Technological factors) analysis and stakeholder mapping, we distill recurring constraints and opportunities. The findings show that, while digitalization, through digital platforms, improved some administrative processes by 2024, the fundamental obstacles identified in 2018 remained largely unchanged. Three core constraints persisted across both periods: fragmented institutional governance, prolonged and opaque permitting procedures that deter investment, and a deep-seated lack of trust between the private sector and public authorities. These systemic failures continue to limit the sector’s potential, especially amid rapid post-pandemic visitor growth. This paper proposes actionable measures to address these challenges: establishing a unified regional tourism coordination authority, streamlining and standardizing regulations and approval processes, and offering targeted capacity building for SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) and local administrations. Implemented together, these reforms can align Almaty’s tourism governance with international good practices and foster more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable tourism growth.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a key driver of economic development, contributing to job creation, infrastructure growth, and regional branding (UNWTO, 2024). The Almaty region, known for its rich natural landscapes, historical sites, and adventure tourism opportunities, plays a significant role in Kazakhstan’s tourism industry. However, the sector faces multiple challenges, including bureaucratic barriers, funding limitations, and inconsistent infrastructure development. Understanding these factors is crucial for improving tourism governance and ensuring sustainable growth (Abubakirova et al., 2016; Baisakalova & Garkavenko, 2014).

Kazakhstan, an independent state since 1991, has experienced a complex transformation in its tourism sector, shaped by historical ties to the Soviet Union. Prior to independence, tourism in Kazakhstan functioned as a social policy tool rather than a commercial industry, with a focus on state-sponsored recreation and ideological integration (Slocum & Klitsounova, 2020). The collapse of the Soviet Union triggered a shift towards a market-driven economy, yet tourism remained underdeveloped due to economic instability and lack of strategic planning (Hanson, 2003). The first Law on Tourism Activity in Kazakhstan was adopted in 1993, marking an initial effort to establish a legal framework for the industry (Baisakalova & Garkavenko, 2014).

Over the past three decades, Kazakhstan has attempted to position tourism as a strategic economic sector. The inclusion of tourism in the government’s priority sectors in 2010 signaled a commitment to its development, yet the sector continues to face structural barriers. Bureaucratic inefficiencies, limited public–private cooperation, and underdeveloped infrastructure hinder sustainable tourism growth. The Soviet-era centralized governance model still influences policymaking, impacting the ability of stakeholders to collaborate effectively (Yasarata et al., 2010).

The period between the two waves of our study (2018 and 2024) was characterized by unprecedented growth in tourism activity in Kazakhstan, interrupted but then accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for assessing the effectiveness of existing management models.

According to the Bureau of National Statistics (BNS, n.d.), at the national level, the tourism sector has demonstrated impressive recovery and growth. While 8.5 million international tourists visited the country in pre-pandemic 2019, this figure reached 9.2 million in 2023 and exceeded 15 million in 2024. Domestic tourism also strengthened: in the first nine months of 2024, the number of domestic tourists reached 10.5 million. This growth had a direct impact on the economy: tourism’s contribution to the country’s GDP in the first half of 2024 increased to 2.5%, and annual tax revenues from the industry exceeded 500 billion tenge (450 tenge = 1$).

Almaty, the country’s main gateway, experienced this growth most acutely. In 2023, the city welcomed 49% of all international tourists. In 2024, tourist flow to Almaty increased by 14.2%, reaching 1.7 million visitors in the first three quarters. Economic indicators confirm this trend: tax revenues from the city’s tourism sector doubled in the first 11 months of 2024, reaching 85.5 billion tenge ($161.8 million), while investment in fixed assets increased by 12%, reaching 92.9 billion tenge ($175.8 million).

This study examines the structural and external factors affecting tourism development in the Almaty region. By conducting a thematic analysis of stakeholder interviews and integrating PEST (Political, Economic, Sociocultural, and Technological factors) analysis, the research identifies key barriers and opportunities for the sector. Additionally, the stakeholder influence and participation map provides insights into the power dynamics shaping tourism policy. The findings aim to contribute to evidence-based decision-making and strategic planning for tourism development in the region. The study also highlights lessons from international best practices and their applicability to the regional context.

2. Literature Review

The Tourism governance has been widely studied as a multidimensional concept encompassing policymaking, stakeholder collaboration, and sustainable development (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Hall, 2019). Effective governance ensures the coordination of public and private actors (Dredge & Jenkins, 2011), balancing economic benefits with environmental and cultural preservation. However, in emerging tourism markets, governance challenges often include fragmented institutional frameworks, lack of funding mechanisms (Ruhanen, 2013), and regulatory inconsistencies. Studies emphasize that governance efficiency is directly linked to the ability of governments to facilitate investment, streamline regulations (Beritelli & Bieger, 2014), and promote sustainable tourism practices.

2.1. Stakeholder Engagement and Tourism Governance

Stakeholder theory posits that successful tourism development hinges on effective coordination among multiple actors, including government agencies, businesses, local communities, and tourists (Freeman, 1984; Jamal & Getz, 1995). Robust stakeholder engagement is linked to fewer conflicts, greater trust, and more inclusive policy outcomes (Sautter & Leisen, 1999). Yet in many destinations—including Kazakhstan—collaboration remains difficult due to power asymmetries and centralized decision-making structures (Hall, 2019; Ruhanen, 2013; Hardy & Pearson, 2018; Sadykova et al., 2020; Abdramanova & Collins, 2022; Tleubekova & Shalpykova, 2021). The tourism governance literature, as discussed by Baggio et al. (2010), underscores that balancing diverse stakeholder interests is vital for sustainable growth, but real-world implementation is frequently impeded by bureaucratic and political constraints.

Sadykova et al. (2020) argue that, in Central Asia, post-Soviet transitions have shaped tourism development models privileging state-led economic growth over sustainability considerations. Although Kazakhstan’s tourism sector benefits from significant natural and cultural assets, research points to persistent weaknesses in infrastructure, limited digitalization, and insufficient community engagement (Abdramanova & Collins, 2022). Comparable governance and implementation gaps are evident in the Almaty region, where policies have struggled to align with stakeholder priorities and market realities (Tleubekova & Shalpykova, 2021). The absence of comprehensive regional strategies and the limited use of data in decision-making have contributed to uneven development and a reactive (rather than proactive) approach to tourism management (Ruhanen, 2013; Baggio et al., 2010; Sadykova et al., 2020; Richards & Hall, 2000; Gretzel et al., 2020). In Central Asia, and Kazakhstan in particular, contemporary policy discourse explicitly frames tourism development as a state task within economic diversification, executed through government-led cluster strategies and other state instruments. Empirical and policy analyses for the region emphasize state programs, strategic roadmaps, and ministerial leadership as core drivers of tourism development and sustainability, further evidencing a centralized approach (Kenzhebekov et al., 2021; Seidahmetov et al., 2014; JICA, 2022).

Prior studies also highlight the pivotal role of the regulatory framework—especially national and regional tourism development programs—in shaping governance effectiveness and stakeholder collaboration. In Kazakhstan, state-driven instruments such as strategic roadmaps and sectoral development projects establish formal guidance on investment, infrastructure, and service quality; however, their implementation varies considerably across regions. Incorporating these policy instruments into the analysis provides a more complete view of the institutional conditions that influence tourism management outcomes.

2.2. The Role of Quality in the Tourism Industry

The quality of services plays a fundamental role in the competitiveness of tourism destinations. As highlighted by Redžić (2018), high-quality services are a critical factor influencing tourist satisfaction, encouraging repeat visits, and shaping the broader destination image. According to Casadesus et al. (2010) and Polukhina et al. (2025), the implementation of internationally recognized quality standards, such as ISO (International Organization for Standardization) or EFQM (European Foundation for Quality Management), enhances the credibility and appeal of tourism services. However, quality management in tourism is not limited to service delivery—it also involves stakeholder perceptions and expectations. A study on stakeholder perception of tourism quality indicates that successful destinations invest not only in infrastructure but also in training programs that improve service professionalism, as noted by Waligo et al. (2013). Sadykova et al. (2020), Abdramanova and Collins (2022), and Tleubekova and Shalpykova (2021) emphasize that Kazakhstan continues to face the challenge of ensuring consistent service quality, especially in remote regions where tourism development is still emerging.

2.3. Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) and Infrastructure Development

Another key aspect of tourism development in post-socialist states is the role of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs). PPPs are often used as a mechanism to stimulate investment and improve service quality in tourism infrastructure (Candrea et al., 2017). In transition economies, where government resources are often constrained, partnerships between the public and private sectors help to fill investment gaps (Linder, 1999). However, UNWTO (2013) highlights that PPPs in developing countries frequently face challenges due to mistrust, lack of stakeholder engagement, and poor policy execution. The effectiveness of PPPs depends on strong institutional frameworks and clear mechanisms for collaboration (Buhalis, 2000).

The Soviet legacy of state-controlled tourism has also left a lasting impact on stakeholder interactions in Kazakhstan. While many post-Soviet states have embraced decentralized tourism governance, Kazakhstan has struggled with inconsistent management structures. The frequent transfer of tourism oversight between different ministries (six changes between 1993 and 2017) has led to a lack of policy continuity (Sadykova et al., 2020; Piirainen, 1997; Shilibekova et al., 2016). Prior research suggests that policy instability discourages long-term investments and undermines industry confidence, as emphasized by Sadykova et al. (2020), Piirainen (1997), and Shilibekova et al. (2016).

2.4. Digitalization and Technological Advancements in Tourism

Recent studies emphasize the role of digitalization in improving tourism governance and visitor experience. The integration of smart tourism technologies, including real-time visitor tracking, AI-driven recommendations, and digital booking systems, is transforming the industry (Gretzel et al., 2020). However, many developing tourism destinations struggle with weak digital infrastructure and slow adoption of technology-driven solutions. In Kazakhstan, the lack of digital mapping, poor online visibility of tourism services, and limited integration of booking platforms remain key obstacles to competitiveness (Gretzel et al., 2020; Polukhina et al., 2025). The digital transformation of tourism is a central policy objective in Kazakhstan, recognized as essential for enhancing global competitiveness and modernizing the industry. Research by Tashpulatova and Suyunova (2025) highlights that government-led initiatives, such as online booking platforms and virtual tours, are designed to improve the country’s appeal. However, they also note persistent challenges, including a digital divide and infrastructure gaps, which can impede the success of these top-down strategies.

Kazakhstan has recently introduced e-Qonaq, a mandatory national electronic platform for registering tourists and collecting accommodation statistics. The system, launched in 2021, aims to improve data reliability, reduce underreporting, and provide government agencies with timely information for tourism policy. The development of digital infrastructure is crucial for enabling a more efficient and data-driven tourism sector.

This challenge is not unique to Kazakhstan. A critical analysis of Spain’s tourism sector by Sánchez-Bayón et al. (2024) provides a cautionary international perspective. They argue that public intervention, especially post-pandemic recovery policies, can create a “double bureaucracy” that ultimately harms competitiveness. Their work warns that, without a focus on genuine readjustment and talent development, public management of digitalization can be ineffective.

2.5. Implications for Sustainable Tourism Development

Sustainable tourism planning requires active participation from all stakeholders to balance economic growth with environmental and social considerations. Case studies from Europe highlight that integrating community voices in tourism policy leads to more resilient and adaptable governance structures (Seidahmetov et al., 2014; Bramwell, 2010; Koščak et al., 2019; Wanner et al., 2020; Ottaviani et al., 2024). Findings suggests that participatory planning methods, including stakeholder workshops and collaborative decision-making, enhance the long-term sustainability of tourism destinations.

This study builds upon existing literature by applying a qualitative approach to analyze tourism governance in the Almaty region. By integrating thematic analysis with PEST and stakeholder mapping, the research contributes to a deeper understanding of the factors shaping tourism policy and practice in the region. Furthermore, this study offers policy recommendations based on findings from stakeholder interviews, aligning them with global best practices for tourism governance.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative comparative cross-sectional design with two independent waves of empirical data collection: in 2018 and in 2024. This design allows us to compare stakeholders’ perceptions at two points in time without assuming continuity between them. The focus was on Almaty city and Almaty region as interconnected but distinct contexts of tourism governance. A map of the study area is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of Almaty region, Kazakhstan (created by authors).

In 2018, 45 semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of local administrations, businesses, and government agencies. In 2024, 32 interviews were conducted with key stakeholders, including tourism entrepreneurs and public sector representatives. Thus, two independent samples (2018 and 2024) are compared, rather than a continuous period “between” these dates.

Sampling was purposive and snowball-based to ensure coverage of the main stakeholder groups: government bodies, tourism enterprises (accommodation, tour operators/agents, food services/guides), associations and community organizations, as well as protected areas/national parks administrations. Authors targeted “key stakeholders” because they occupy decision-making and implementation roles that provide privileged, experience-based knowledge of governance processes, inter-agency coordination, and regulatory bottlenecks. Recruitment was carried out through professional networks and local administrations. All participants provided informed consent, and data were anonymized at the stage of transcription. In total, two independent samples were collected: 45 respondents in 2018 and 32 respondents in 2024. In 2018, government bodies accounted for the largest share of the sample (44%), followed by tourism enterprises such as accommodation providers and resort operators (13%), tour operators and guides (9%), national parks and protected areas (11%), cultural institutions and museums (9%), associations and NGOs (Non-Governmental Organization) (11%), and service/hospitality enterprises (2%). By 2024, the distribution had shifted: government bodies represented 22%, national parks 22%, tourism businesses (tour operators and guides) 16%, accommodation providers 9%, cultural institutions and museums 12%, associations 6%, and service/hospitality enterprises 13%.

To provide greater transparency, we also included the gender composition of respondents. Male participants predominated in both years (69% in 2018 and 69% in 2024), while female stakeholders represented 31% of the total sample in both periods. Table 1 presents the detailed distribution by stakeholder group, organizational type, governance level, and gender.

Table 1.

Respondent profile by stakeholder group and gender (2018 and 2024).

The semi-structured interview guide was developed directly by the authors, drawing upon a review of relevant literature on tourism governance and public–private interaction, as well as the specific context of the Almaty region. The interview guide was refined after two trial interviews to improve clarity and wording. Interviews were conducted by members of the research team (Sakypbek M. and Assipova Zh.), either face-to-face or online, depending on participants’ preferences. The guide included thematic blocks on: governance architecture and coordination; bureaucratic barriers (permit procedures); access to funding/subsidies; data collection and use (including e-Qonaq); infrastructure bottlenecks; and trust and mechanisms of government–business interaction. Interviews lasted on average 60–90 min.

All quotations are reported in anonymized form, indicating role and year (e.g., tourism entrepreneur, interview, 2024), without simulating a bibliographic reference. This protects confidentiality while preserving contextual meaning.

Before each interview, participants received information about the aims of the study, voluntary participation, the right to withdraw, and confidentiality principles. Consent was recorded either in writing or verbally on audio at the beginning of the interview.

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, followed by inductive thematic analysis. Two researchers independently coded the transcripts, reconciled discrepancies through discussion, and iteratively refined the coding framework. No specialized software was used; standard text editors were applied. All data were anonymized. Analytical categories corresponded to the thematic areas of the guide (bureaucratic barriers; access to funding; statistics/monitoring; infrastructure; coordination; trust), ensuring comparability across the 2018 and 2024 datasets.

To contextualize the findings, we conducted a PEST analysis (Political, Economic, Social, Technological factors) based on interview materials and document analysis. This approach links identified barriers to macro-environmental drivers.

An influence–interest matrix was constructed using interview data and expert judgment of the research team to visualize the distribution of power and involvement of different groups in tourism governance.

- Interview Questions

To gain insights into the key challenges and developments in tourism governance, the following questions were asked during the interviews in both 2018 and 2024:

- How is tourism governance structured in your region?

- What are the main bureaucratic barriers businesses face when operating in the tourism sector?

- How has the coordination between government bodies and private stakeholders evolved over time?

- What challenges exist in accessing financial support, grants, and subsidies for tourism projects?

- How is tourism data collected and monitored? Have there been improvements in recent years?

- What are the major infrastructure-related challenges in tourism development?

- How would you describe the level of trust between businesses and government institutions in tourism policymaking?

- What role do digital platforms play in improving coordination and information sharing?

- Have any new regulations or policies had a significant impact on the tourism industry?

- What recommendations would you propose to improve tourism governance in your region?

Interviews were conducted using purposive and snowball sampling to ensure coverage of key stakeholder groups, including government representatives, tourism businesses, associations, and community organizations. Participants were recruited through professional networks and local administrations, and all provided informed consent prior to participation. Data were anonymized at the transcription stage, and thematic coding was applied inductively. Two researchers coded the material independently and resolved discrepancies through discussion; no specialized software beyond standard word-processing tools was used.

4. Results

4.1. Thematic Categorization of Responses

Based on the interview data, responses were categorized into four key areas: bureaucracy, funding, statistics, and infrastructure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key Barriers and Challenges in Tourism Development: Comparison of 2018 vs. 2024 Findings.

4.2. Stakeholder Coordination

In 2018, the lack of coordination among stakeholders was one of the key barriers to tourism development in the Almaty region. Local administrations had limited engagement with private businesses, and tourism management was often fragmented across different government departments. Interviews from 2018 indicated that tourism responsibilities were frequently assigned to sports or entrepreneurship departments, leading to inefficiencies and a lack of specialized focus. Respondents also highlighted the absence of structured communication platforms for stakeholder engagement. One respondent from the Department of Entrepreneurship in 2018 stated, “Tourism is not a priority for local authorities, and there is no single coordination mechanism.” Another respondent from a local tourism board added, “We often don’t know who is responsible for tourism development—it keeps shifting between departments.”

By 2024, some improvements have been observed. The introduction of digital platforms, such as e-Qonaq, has facilitated better information-sharing and coordination between tourism operators and government authorities. However, local administrations still lack dedicated tourism specialists, and decision-making remains centralized, limiting the effectiveness of regional tourism management. Businesses continue to express concerns about the slow responsiveness of government institutions and limited collaboration opportunities. A 2024 interviewee from a private tour company noted, “We now have better tools for reporting, but communication with local governments is still bureaucratic and slow.” Another business owner commented, “We submit requests online, but the processing time hasn’t improved. The system is there, but it’s not working efficiently.”

4.3. Bureaucratic Barriers

The 2018 interviews revealed that bureaucratic inefficiencies significantly hindered tourism development. Frequent changes in tourism governance structures, delays in obtaining permits, and complex regulatory requirements discouraged private investment. Many businesses reported difficulties in accessing subsidies and government support programs due to a lack of transparency in application processes. As one business owner from a guesthouse in 2018 explained, “It takes months to get simple approvals, and the rules keep changing.” Another respondent from a travel agency added, “We don’t even apply for government support because the process is too complicated and unclear.”

In 2024, while some progress has been made, bureaucratic barriers persist. Digitalization has improved administrative processes, yet many regulatory procedures remain cumbersome. Stakeholders indicate that inconsistent policies and overlapping responsibilities among different agencies continue to create obstacles for business operations. Additionally, local administrations report challenges in enforcing tourism-related regulations, particularly in rural and natural areas. A tourism entrepreneur from the Almaty region in 2024 remarked, “We now have online forms, but approvals still depend on personal connections rather than clear procedures.” Another entrepreneur stated, “Each region seems to have its own rules, and no one follows a unified process.”

One of the most prominent themes in the interviews was the issue of weak stakeholder engagement and lack of coordination between government agencies and private enterprises. Respondents highlighted that bureaucratic complexity and unclear regulations hinder investment and business development. As one tourism entrepreneur noted: “We now have online forms, but approvals still depend on personal connections rather than clear procedures.” (Tourism entrepreneur, 2024). Another business owner shared: “Each region seems to have its own rules, and no one follows a unified process.” (Business owner, 2024).

4.4. Infrastructure and Investment

In 2018, infrastructure deficiencies were a major issue for tourism development in the Almaty region. Poor road conditions, a lack of proper sanitation facilities, and limited accommodation options were frequently mentioned as barriers. Many tourism enterprises were officially registered in Almaty, which meant that local budgets in rural areas did not benefit from tourism-generated revenues. A respondent from a regional tourism office in 2018 noted, “Our roads are terrible, and tourists avoid some areas because of accessibility issues.” Another local official added, “Investors hesitate to develop projects in rural areas because of the lack of basic utilities.”

By 2024, infrastructure development has seen some improvements. Investments in road construction have enhanced accessibility to key tourist destinations. However, challenges remain in areas such as water supply, electricity, and digital connectivity, particularly in remote regions. Interviews indicate that while private sector interest in tourism infrastructure has grown, bureaucratic delays and land ownership issues still discourage long-term investments. One business owner from a travel agency in 2024 stated, “There is more interest in investment, but securing land for tourism projects remains a huge challenge.” Another entrepreneur remarked, “We see new hotels being planned, but the permit process is still painfully slow.”

4.5. Tourism Data and Monitoring

In 2018, one of the major concerns was the lack of accurate data on tourist flows. Most local administrations did not have a systematic method for tracking visitor numbers, relying on estimations rather than concrete statistics. Businesses were reluctant to report their actual visitor numbers due to concerns about taxation and regulatory scrutiny. A government official from the Ministry of Tourism in 2018 admitted, “We estimate visitor numbers based on hotel bookings, but many tourists stay in private accommodations.” Another respondent from a local tourism office said, “There is no real tracking system; we mostly rely on word-of-mouth estimates from businesses.”

By 2024, the situation has partially improved. The implementation of e-Qonaq has introduced a more structured approach to data collection, allowing for better monitoring of visitor statistics. However, discrepancies between reported and actual figures remain an issue, as some businesses still avoid full compliance with reporting requirements. Additionally, statistical monitoring in rural areas remains inadequate, leading to gaps in understanding the true scale of tourism activity. A tourism expert from a research institute in 2024 commented, “The new system helps, but many businesses still underreport their numbers to avoid extra taxation.” Another business owner confirmed, “We register our guests, but we know many small operators who still don’t.”

4.6. Trust Between Government and Business

In 2018, interviews indicated a low level of trust between government bodies and private businesses. Many entrepreneurs viewed government support programs with skepticism, citing a lack of transparency in decision-making and difficulties in accessing financial aid. One entrepreneur from a resort in 2018 said, “We apply for grants, but they always go to the same well-connected companies.” Another respondent added, “Public-private partnerships exist only on paper, but in reality, businesses are left out of the decision-making process.”

In 2024, the relationship between public and private sectors has slightly improved, but challenges remain. Some businesses report increased engagement from local authorities, particularly through online platforms and business forums. However, concerns about favoritism, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and inconsistent enforcement of regulations persist. Many stakeholders still feel that government policies are developed without sufficient consultation with industry representatives, leading to a disconnect between policy intentions and practical implementation. A tourism business owner from a national park in 2024 noted, “We are consulted more often now, but key decisions are still made without real industry input.” Another entrepreneur said, “The dialogue is better, but there is still a long way to go before businesses and the government truly work as partners.”

4.7. PEST Analysis of Tourism in Almaty Region

The findings from the stakeholder interviews highlight several structural challenges and opportunities in the development of tourism in the Almaty region. To better understand the external factors shaping the industry, a PEST analysis was conducted, examining political, economic, social, and technological influences (Table 3).

Table 3.

PEST (Political, Economic, Sociocultural, and Technological factors) Analysis of Tourism in Almaty Region.

4.8. Stakeholder Influence and Participation Map

A key discussion point emerging from the data was the role of PPPs in tourism governance. While PPPs are recognized as a mechanism for stimulating investment and improving service quality (Candrea et al., 2017), findings suggest that their implementation in Kazakhstan faces institutional and trust-related challenges. Respondents pointed out that although organizations like Visit Almaty were designed to foster public–private cooperation, limited funding and unclear mandates reduce their effectiveness. A tourism association representative stated: “We hold meetings with policymakers, but sometimes our proposals take years to be implemented.” (Tourism association representative, 2024).

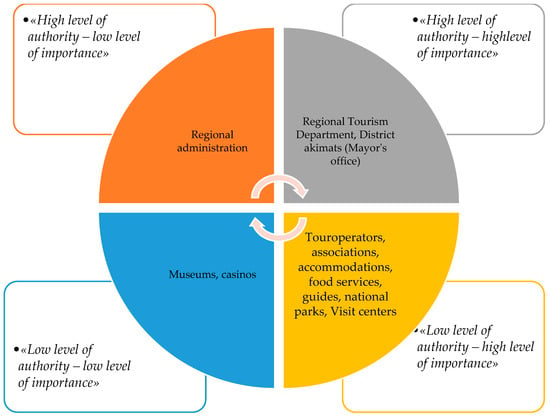

As shown in the Figure 2, Stakeholders are categorised according to their level of influence and interest:

Figure 2.

Stakeholder Matrix-Map by the “Influence–Interest” Category.

- (a)

- High Influence—High Participation: These are the key decision-makers who directly shape tourism development, such as regional tourism authorities, local government bodies, and major investors. “We hold meetings with policymakers, but sometimes our proposals take years to be implemented.” (Tourism association representative, 2024)

- (b)

- High Influence—Low Participation: These stakeholders hold significant power but are less actively involved in everyday tourism activities. This includes financial institutions and national regulatory bodies. “We provide funding options, but the sector needs better risk assessment mechanisms.” (Bank representative, 2024)

- (c)

- Low Influence—High Participation: This group includes small business owners, tour operators, and local entrepreneurs who actively contribute to the industry but have limited policymaking power. “We create jobs and attract visitors, yet our voices are often ignored in strategic planning.” (Tour operator, 2024)

- (d)

- Low Influence—Low Participation: These are peripheral stakeholders such as local NGOs, small cultural institutions, and independent guides who have minimal control over tourism policies but still contribute to the ecosystem. “We try to promote sustainable tourism, but without policy support, our impact is limited.” (Eco-tourism advocate, 2024)

By mapping out these stakeholders, it becomes evident that, while decision-making remains concentrated at the top, greater inclusion of local businesses and communities could enhance tourism development in the Almaty region. Findings suggest that high-influence actors dominate decision-making, often sidelining local businesses and community stakeholders. This imbalance in power dynamics leads to policy inefficiencies and a lack of grassroots involvement, further reinforcing bureaucratic challenges in tourism governance.

5. Discussion

This study compared stakeholder perceptions of tourism governance in Almaty city and its surrounding region between 2018 and 2024. The research aimed to identify bureaucratic, infrastructural, and coordination barriers that limit tourism development and to examine how these evolved over time. The results highlight that while certain processes have been modernized through digitalization and selective infrastructure upgrades, three systemic barriers remain: fragmented governance structures, prolonged and opaque regulatory procedures, and a persistent trust deficit between public and private actors. These factors limit the capacity of Almaty’s tourism sector to transform its natural and cultural assets into sustained, competitive growth. The following subsections interpret these findings in light of existing research and theoretical frameworks.

5.1. Governance Fragmentation and Bureaucratic Load

Respondents consistently emphasized the complexity of regulatory procedures, frequent changes in administrative responsibilities, and long approval processes. In 2024, despite digital tools, approvals were still said to depend on “personal connections”. These challenges align with previous research indicating that fragmented governance structures create barriers for effective tourism management (Hall, 2019; Tleubekova & Shalpykova, 2021). Stakeholder theory, as outlined by Freeman (1984), suggests that inclusive decision-making leads to better tourism outcomes, yet evidence shows that Kazakhstan continues to struggle with top-down governance, limiting the influence of businesses and local communities. This confirms earlier observations that post-Soviet governance structures remain highly centralized and prone to administrative inefficiencies (Sadykova et al., 2020; Abdramanova & Collins, 2022).

5.2. Stakeholders, Participation, and Trust

The interviews indicate that, while digital platforms like e-Qonaq have provided more structured reporting, many small operators remain skeptical of government intentions and underreport to avoid taxation. Low levels of trust between businesses and authorities reflect findings from earlier research showing that power imbalances and weak consultation practices hinder meaningful collaboration, as highlighted by Jamal and Getz (1995) and Sautter and Leisen (1999). In practice, these limits both compliance and innovation, since entrepreneurs hesitate to formalize or invest where rules feel unpredictable and support mechanisms are viewed as inaccessible or biased.

5.3. Public–Private Partnerships and Investment

Respondents often mentioned that PPPs exist “on paper,” but in practice their mandates and outcomes remain unclear. Organizations like Visit Almaty have facilitated dialog but without consistent follow-through. The literature highlights that successful PPPs require strong legal frameworks, long-term commitment, and clearly defined roles, as emphasized by UNWTO (2013) and Buhalis (2000). The findings suggest that Kazakhstan has yet to establish the necessary institutional stability to support effective PPPs in tourism. This helps explain why investment interest exists but is slowed by opaque land-use approvals, lengthy permits, and uncertainty about government commitments. As Candrea et al. (2017) and Linder (1999) demonstrate, unstable institutional frameworks in post-socialist contexts similarly discourage private sector confidence.

5.4. Data Systems, Digitalization, and Service Quality

The partial adoption of e-Qonaq reflects Kazakhstan’s attempt to modernize data collection and tourism monitoring. However, persistent underreporting and weak rural coverage show that compliance and capacity lag behind technology. According to Polukhina et al. (2025), smart tourism initiatives contribute to improved governance outcomes only if they are accompanied by sufficient digital connectivity and mechanisms that encourage stakeholder participation. At the same time, stakeholders highlighted that service quality remains uneven across the region. Studies on destination competitiveness underline that infrastructure alone is insufficient; investments in staff training, professional standards, and customer service are equally critical for improving tourist satisfaction and repeat visitation (Redžić, 2018; Waligo et al., 2013).

5.5. Infrastructure and Land-Use Frictions

Improvements in road networks and new hotel projects indicate positive movement, yet difficulties with land acquisition and basic utilities remain significant bottlenecks. These “last-mile” issues, where macro-level investments fail to translate into local service quality, are widely documented in tourism development literature (Ruhanen, 2013; Richards & Hall, 2000). Stakeholder accounts of delays in obtaining permits, alongside inconsistent enforcement of land-use regulations, suggest that bureaucratic rather than financial constraints are now the critical factor impeding investment.

5.6. Synthesis and Implications

Findings from the study reveal that, despite significant digitalization efforts and infrastructure upgrades, core governance barriers identified in 2018—namely fragmented governance, opaque regulatory procedures, and low stakeholder trust—persisted in 2024. This persistence of systemic issues is especially concerning when viewed against the backdrop of the explosive tourism growth documented between the two study periods. Taken together, the results show that progress in Almaty’s tourism sector is incremental and uneven. Digitalization and selective infrastructure upgrades have improved surface-level processes but not the deeper governance structures that shape trust, efficiency, and investment confidence. This confirms the argument that tourism governance in post-socialist contexts remains constrained by institutional instability and centralized decision-making (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Hall, 2019; Dredge & Jenkins, 2011; Sadykova et al., 2020; Piirainen, 1997). Sadykova et al. (2020) emphasize that the challenges of fragmented responsibilities, policy inconsistency, and weak trust in authorities are common across post-Soviet and transition economies, where they act as barriers to sustainable tourism growth. Placing Almaty within this regional picture highlights that its challenges are not isolated but part of broader systemic legacies. To address these challenges, the several implications that emerge are as follows:

- Clarify mandates and streamline approvals: Public authorities should publish clear, time-bound permit and subsidy procedures, reducing discretion and uncertainty.

- Institutionalize participation: Beyond ad hoc meetings, structured mechanisms for SME (Small and Medium-sized Enterprise) and community involvement can improve trust and policy relevance.

- Strengthen PPP frameworks: Standard contracts that allocate risks and define roles ex-ante are needed to attract private investment.

- Invest in human capital: Training programs, service quality standards, and workforce development are necessary complements to physical infrastructure.

- Link digital tools with incentives: Reporting platforms must return value to businesses—through data dashboards, promotion, or easier access to grants—to increase compliance and accuracy.

Beyond competitiveness, addressing these issues is also essential for sustainability. Inclusive governance and reliable data are prerequisites for balancing economic growth with community well-being and environmental stewardship. If stakeholders continue to view tourism as opaque or unfair, the sector risks not only underperformance but also low social acceptance, which can undermine long-term resilience.

The findings of this study also underline the importance of considering national and regional tourism development programs as a contextual factor in evaluating governance effectiveness. By analyzing state-driven strategies, the objectivity of the results has been strengthened, since these programs directly affect regulatory procedures, investment incentives, and coordination mechanisms. This integration of policy instruments into the analysis provides a more nuanced perspective on how top-down frameworks interact with local stakeholder practices in the Almaty region.

5.7. Limitations and Future Research

This study’s findings derive from qualitative interviews conducted in 2018 and 2024 with partially overlapping respondent groups. While core themes were consistent across years, some differences may reflect sample composition. Because tourism in Kazakhstan is shaped by a post-Soviet, state-centered governance tradition, many respondents tended to equate “tourism governance” with government-led promotion and regulation; this interpretive lens reflects the empirical reality of internal tourism development but may limit the transferability of findings to contexts with more diversified governance arrangements. The focus on the Almaty region further constrains generalizability to other parts of Kazakhstan with different institutional settings or resource bases. Future research should triangulate stakeholder interviews with standardized surveys (e.g., Likert scales in the range of 1–5 or 1–10) and administrative e-Qonaq data as coverage improves to enhance the objectivity and comparability of findings. Comparative studies with other Central Asian destinations could also clarify which governance reforms are most transferable to Kazakhstan’s context.

6. Conclusions

This study has shown that, despite Almaty’s strong tourism potential, systemic governance barriers continue to constrain its growth. The comparison of stakeholder perspectives from 2018 and 2024 revealed that regulatory complexity, fragmented institutional responsibilities, and limited trust between government and business remain the most pressing obstacles. While digital platforms such as e-Qonaq and recent infrastructure upgrades mark progress, these measures have not yet resolved underreporting, bureaucratic delays, or coordination gaps.

The key contribution of this research lies in demonstrating how legacies of centralized governance, weak stakeholder engagement, and insufficient institutional frameworks limit the effectiveness of tourism policy in a post-Soviet context. By linking these findings to international scholarship, the study highlights the critical importance of governance reforms for destination competitiveness and sustainable development.

Policy implications are clear. First, regulatory procedures must be simplified and standardized across districts to reduce uncertainty for investors and operators. Second, public–private partnerships require stable legal frameworks, transparent mandates, and accountability mechanisms in order to attract long-term capital. Third, capacity building and service quality improvements are essential to strengthen the human dimension of tourism. Finally, digital platforms should be integrated with incentives and reliable infrastructure to ensure that data collection translates into value for both businesses and policymakers. The recommended governance reforms align with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 (decent work and inclusive growth) through enabling investment and formalization; SDG 9 and 11 via infrastructure and service-quality improvements; and SDG 16 through transparent, participatory institutions that build trust between public and private actors (United Nations, 2015).

In conclusion, the rapid, post-pandemic expansion of tourism in Almaty presents both a significant economic opportunity and a critical governance challenge. The recommendations proposed in this study—namely, the establishment of a unified regional authority and the streamlining of regulatory processes—are not merely theoretical improvements. They are essential, practical steps required to manage this growth sustainably and ensure that the doubling of tax revenues and rising investments translate into long-term resilience rather than short-term strain. Addressing these long-standing governance barriers is imperative if Almaty is to fully capitalize on its tourism potential in an inclusive and sustainable manner.

Looking ahead, addressing these challenges will require a multi-level governance approach that builds trust, empowers local actors, and embeds participatory mechanisms into policy design. This would not only enhance competitiveness but also ensure that tourism contributes to inclusive and sustainable development in Almaty and beyond. Future research should extend this analysis to other regions of Kazakhstan and explore how specific governance reforms influence long-term outcomes in tourism performance and community well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and L.M.; Methodology, M.S., Z.A. and L.M.; Validation, Z.A. and M.Y.; Formal analysis, M.S., Z.A. and L.M.; Investigation, M.S.; Resources, M.S. and M.Y.; Data curation, M.S., M.Y., Z.A. and A.A.; Writing—original draft, M.S., Z.A., L.M. and M.Y.; Writing—review and editing, M.S., Z.A., L.M. and M.Y.; Visualization, M.S., M.Y. and Z.A.; Supervision, A.A. and M.S.; Project administration, A.A.; Funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has was funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR21882122), BR21882122—Sustainable development of natural-industrial and socio-economic systems of the West Kazakhstan region in the context of green growth: a comprehensive analysis, concept, forecast estimates and scenarios.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Local Ethical Committee (LEC) of Al-Farabi Kazakh National University (approval code: (IRB00010790) IRB-A1547 and approval date: 27 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions, as they contain information provided in confidence by stakeholders during interviews. Summarized or anonymized data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the administration of Almaty Tourism Bureau, Visit Alatau and Open Travel Advisory LLP for their invaluable support in providing data and facilitating field research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PPP | Public–Private Partnership |

| PEST | Political, Economic, Social, and Technological analysis |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| UNWTO | United Nations World Tourism Organization |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| EFQM | European Foundation for Quality Management |

References

- Abdramanova, G., & Collins, R. (2022). Tourism development in Kazakhstan: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Central Asian Studies, 15(2), 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakirova, A., Syzdykova, A., Kelesbayev, D., Dandayeva, B., & Ermankulova, R. (2016). Place of tourism in the economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Procedia Economics and Finance, 39, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R., Scott, N., & Cooper, C. (2010). Network science: A review focused on tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 802–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baisakalova, A., & Garkavenko, V. (2014). Competitiveness of tourism industry in Kazakhstan. In M. A. Editor (Ed.), Tourism in central Asia (pp. 16–37). Apple Academic Press (Taylor & Francis/CRC Press). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P., & Bieger, T. (2014). From destination governance to destination leadership: Defining and exploring the significance with the help of a perspective. Tourism Review, 69(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. (2010). Participative planning and governance for sustainable tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(3), 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of National Statistics (BNS). (n.d.). Tourism statistics. Agency for strategic planning and reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Candrea, A., Constantin, C., & Ispas, A. (2017). Public–private partnerships for a sustainable tourism development of urban destinations: The case of Braşov, Romania. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 13(SI), 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus, M., Marimon, F., & Alonso, M. (2010). The future of standardised quality management in tourism: Evidence from the Spanish tourist sector. The Service Industries Journal, 30(14), 2457–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2011). Tourism policy and planning: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U., Fuchs, M., Baggio, R., Hoepken, W., Law, R., Neidhardt, J., Pesonen, J., Zanker, M., & Xiang, Z. (2020). e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Information Technology & Tourism, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Tourism governance: Relations, markets, and power. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, P. (2003). The rise and fall of the Soviet economy: An economic history of the USSR 1945–1991. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A., & Pearson, L. (2018). Examining stakeholder group specificity: An innovative sustainable tourism approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (2022). Central Asia region data collection survey on tourism industry promotion: National policies, CAREC Tourism Strategy 2030, ministerial roles. JICA. Available online: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12363974.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Kenzhebekov, N., Zhailauov, Y., Velinov, E., Petrenko, Y., & Denisov, I. (2021). Foresight of tourism in Kazakhstan: Experience economy. Information, 12(3), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koščak, M., O’Rourke, T., & Bilić, D. (2019). Community participation in the planning of local destination management. Informatologia, 52(3–4), 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, S. H. (1999). Coming to terms with the public–private partnership: A grammar of multiple meanings. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(1), 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, D., Åberg, H. E., & de Luca, C. (2024). Achieving the SDGs through cultural tourism: Evidence from practice in the TExTOUR project. European Journal of Cultural Management and Policy, 31, 12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piirainen, T. (1997). Towards a new social order in Russia: Transforming structures, institutions, and everyday life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Polukhina, A., Sheresheva, M., Napolskikh, D., & Lezhnin, V. (2025). Digital solutions in tourism as a way to boost sustainable development: Evidence from a transition economy. Sustainability, 17(3), 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redžić, D. (2018). Significance of quality in the tourism industry: Research study on the perception of stakeholders in tourism. Menadžment u hotelijerstvu i turizmu, 6(2), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G., & Hall, D. (2000). Tourism and sustainable community development. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhanen, L. (2013). Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadykova, G., Yessentayeva, B., & Tleubekova, G. (2020). Tourism governance in post-Soviet Central Asia: A case study of Kazakhstan. Central Asian Journal of Tourism Research, 5(2), 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sautter, E. T., & Leisen, B. (1999). Managing stakeholders: A tourism planning model. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A., Sastre, F., & Isasi, L. (2024). Public management of digitalization into the Spanish tourism services: A heterodox analysis. Review of Managerial Science, 19, 2235–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidahmetov, M., Aidarova, A., Abishov, N., Dosmuratova, E., & Kulanova, D. (2014). Problems and perspectives of development of tourism in the period of market economy (Case Republic of Kazakhstan). Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 143, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shilibekova, B., Syzdykbayeva, B., Ayetov, S., Agybetova, R., & Baimbetova, A. (2016). Ways to improve strategic planning within the tourist industry (case of Kazakhstan). International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(11), 4205–4217. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1114824.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Slocum, S. L., & Klitsounova, V. (Eds.). (2020). Tourism development in post-Soviet nations: From communism to capitalism. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashpulatova, L., & Suyunova, F. (2025). Digital transformation of the tourism industry and its impact on export potential: Evidence from Kazakhstan. Journal of Central Asian Studies, 23(1), 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleubekova, G., & Shalpykova, U. (2021). Tourism policy in Kazakhstan: Achievements and future challenges. Journal of Asian Studies, 10(3), 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development (A/RES/70/1). United Nations. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- UNWTO. (2013). Public–private partnerships: Tourism development and cooperation strategies. United Nations World Tourism Organization. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. (2024). International tourism highlights, 2024 edition. United Nations World Tourism Organization. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V. M., Clarke, J., & Hawkins, R. (2013). Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tourism Management, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, A., Seier, G., & Pröbstl-Haider, U. (2020). Policies related to sustainable tourism: An assessment and comparison of European policies, frameworks and plans. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 29, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasarata, M., Altinay, L., Burns, P., & Okumus, F. (2010). Politics and sustainable tourism development: Can they coexist? Voices from North Cyprus. Tourism Management, 31(3), 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).