Abstract

Augmented reality has hastened innovators to create things instantly. It has long been understood that the tourism industry is an industry of cultural exchange and visitation seeking experience, satisfaction, and pride. This study aims to increase behavior intention and delight mediating through experiential value co-creation using service-dominant logic theory. This study answers the focused research question by conducting surveys (n = 307) of members of Generation Y in Jakarta and Semarang city. The findings show that experiential value co-creation and delight directly and indirectly have a positively effect on behavior intention in virtual travel. This research offers a new concept, namely experiential value co-creation, to explain the connection between how tourists’ behavior in surfing the internet can influence their behavior intentions. This research certainly has managerial implications which are very useful for increasing behavioral intention, especially in the tourism sector. Tourist attraction managers must pay attention to content that discusses tourist destinations. Complete and accurate information is very useful in increasing the desire to visit tourist locations.

1. Introduction

A tourist destination is a place to visit where there are many interesting things to see. Information is generated from tour managers, Google, websites, and other sources prior to the determination of one’s visiting intention. People are curious to witness the beauty of the things there. However, in this digital era, visits can be paid for after the fact () provided that there are some points of interest available.

The digital transformation of the travel industry has significantly altered how travelers interact with service providers and experience tourism products. Today’s online travelers actively engage in creating their journeys through platforms that offer personalized, interactive, and community-driven features. In this context, the concept of experiential value co-creation (EVCC) has gained prominence. This concept emphasizes the active role of consumers in shaping their experiences in collaboration with providers or platforms (). Unlike in traditional service delivery, value is no longer pre-packaged but co-constructed through digital interactions such as personalized itineraries, content sharing, and peer feedback mechanisms.

Understanding behavioral intention, which includes intentions to revisit, recommend, or positively review online platforms or destinations, is essential for tourism stakeholders in the increasingly competitive online market. Although numerous studies have examined satisfaction, trust, and perceived quality as predictors of behavioral intention, the role of experiential value co-creation (EVCC) in online travel environments remains underexplored (). Moreover, the emotional outcomes of co-creation, such as delight, and the alignment between traveler identity and platform or destination image (self-image congruence) are critical yet insufficiently examined. Addressing this gap, this study investigates how experiential value co-creation impacts behavioral intention, mediated by delight and identity-based emotional resonance in online traveler contexts.

Behavioral desire refers to the inclination to engage in activities that we enjoy and that we feel reflect our identity and often serves as a strong source of motivation. People tend to feel attached to familiar environments and the communities within them, particularly when harmonious relationships among neighbors are well maintained. The intention to visit, either physically or virtually, reflects the degree of our liking for a particular tourist destination. In the context of this research, the intention to visit a certain destination arises from the influence of information stored in our minds and memories. Desire is always mediated by memory (), which is shaped by positive or negative impressions. When it comes to visiting intentions, such desires are typically sparked by positive impressions, especially when the destination resonates with one’s identity (; ).

The growing availability of advanced technology has increased the desire to explore and travel virtually. As one participant noted, “Every week I don’t have to worry about missing the opportunity to visit a destination that represents me. Each day, my intention to visit grows stronger, and I feel more compelled to invite friends along” (; ). In the digital information era, access to abundant and easily available content about tourist attractions such as marine park tours enhances this intention. According to (), tripartite relationships can foster value co-creation in promoting attractions or destinations. Similarly, () suggests that memories associated with culture, customs, cuisine, and attractions can stimulate a desire to visit. Furthermore, the tripartite relationship between cities, destinations, and tourists can lead to shared and consistent information, as these entities often emphasize similar aspects (). In this paper, the researchers address the following research questions:

- (1)

- What are the factors that affect delight and behavior intention?

- (2)

- How do we increase delight and behavior intention for a particular destination in the digital era?

This research introduces a multi-path mediation model that connects experiential value co-creation (EVCC) with behavioral intention via two critical emotional constructs, delight and self-image congruence. While experiential value co-creation (EVCC) has been studied in offline services and hospitality contexts, its application in digital tourism platforms, where users participate in co-creating value virtually, remains limited (). By focusing specifically on online travelers, this study redefines how digital interactions shape intentions, moving beyond the satisfaction–loyalty paradigm that dominates the current literature.

The second novel contribution of this study lies in positioning delight not just as an outcome but as an emotional mediator that amplifies the effect of co-created experiences on future behavior. This highlights the experiential–affective loop that is increasingly relevant in digitally mediated consumer journeys. Lastly, by integrating self-image congruence into the experiential value co-creation (EVCC) framework, this study advances current models of identity-consistent consumption in tourism. These insights can guide tourism marketers and platform developers in designing more engaging, emotionally resonant experiences for digital-native travelers.

The recent literature has increasingly emphasized the importance of co-creation in tourism and service management. () stress that co-created experiences contribute significantly to tourist satisfaction and emotional outcomes. Similarly, () found that value co-creation, when linked with emotional intelligence, leads to tourist delight and increased loyalty. However, these studies focus largely on offline or hybrid travel settings, with limited focus on the fully digital co-creation process occurring through travel apps, online communities, or AI-based personalization tools.

Moreover, studies exploring the mediating role of delight in the relationship between co-created value and behavioral outcomes remain scarce in the digital tourism context. While research by () explores self-congruity and experiential value, the integration of identity-based constructs into experiential value co-creation (EVCC) models for online travel behavior is still in its infancy. This research aims to fill that theoretical gap by combining co-creation theory, self-image congruence, and emotion-based mediation in one comprehensive model. In doing so, it provides a state-of-the-art contribution to the fields of digital tourism behavior, experiential marketing, and consumer psychology.

The digital era of information is growing: () found that online networking behavior is powered by digital network technologies. At the present time, virtual reality is one of the best choices to present things in an increasingly visual manner without a real visit. Therefore, the objective of this study is to increase delight and behavior intention through experiential value co-creation rooted in service dominant logic theory (). Behavior intention can be increased when individuals, including other stakeholders, take part in symmetric actions (; ; ).

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Behavior Intention

Behavioral intention in the context of tourism refers to repeated action carried out to create a habit, curiosity, and willingness to visit consistently. According to (), consumer expectations suggest that if the brand of an item or destination matches the buyer’s identity, the likelihood of visiting and revisiting increases. Of course, this is related to the expectations of customer or visitor satisfaction itself (). Digital networks suggest that online networking behavior may differ from networking face to face due to the properties of digital network technologies. The most influential factors in increasing intention behavior, according to previous research, are smart information systems and smart sightseeing (; ). The habit of seeking information as often as possible can increase the behavior of intentions toward an object or tourist destination (). () stated that in addition to information seeking, the next most important factor is visibility, where augmented reality technology can play a major role.

However, the researchers assume that there are still many other factors, comprising several subjects and reasons, that drive behavior and intention (; ). An overwhelming desire, ease of visiting with advanced technology, or the similarity of one’s identity to that of a tourist attraction, for example, will increase behavior and intention (; ). The theory of reasoned action (TRA), developed by (), posits that an individual’s behavioral intention is determined by their attitude toward the behavior and subjective norms. In the context of tourism, this theory has been widely applied to explain how beliefs and social influences shape travelers’ intentions and decisions. The theory of reasoned action (TRA) suggests that behavior is not random but rather the result of conscious reasoning grounded in the evaluation of consequences and social pressures. However, the researchers assume that there are still many other factors—consisting of several personal, social, and contextual reasons—that drive behavior and intention. These may include emotional responses, past experiences, brand involvement, and perceived experiential value, which are not explicitly captured in the theory of reasoned action (TRA) but are crucial in understanding the dynamic nature of online traveler behavior. Thus, while the theory of reasoned action (TRA) provides a foundational lens, this study extends beyond it by incorporating experiential value co-creation and self-image congruence to more holistically explain online tourists’ behavioral intentions.

A person’s self-congruence causes their identity to be synonymous with that of an object, attraction, or interesting tourist destination, of course. Behavior intention, according to (), indicates a traveler’s intent to visit, revisit, recommend, or engage with a destination. Using technological advances such as augmented reality, one can invite friends to a location through social media, which is already widely used by members of Generation Y, who make up part of the population of this study. Cooperation in the value of a preferred tourist object is very easy to carry out, as evidenced by English football fans in Indonesia and other countries (; ; ).

The theory of generations suggests that individuals born in specific time periods share distinct traits, preferences, and behavioral patterns shaped by shared experiences and technological exposure (). Members of Generation Y (whose members are also known as millennials), born between 1981 and 1996, are digital natives who frequently use technology for decision-making, including travel planning (). Their affinity for online platforms, user-generated content, and immersive digital experiences makes these individuals highly relevant for studying behavioral intentions in virtual tourism contexts. This generational cohort represents a key segment in tourism marketing due to their strong preference for experiential and co-created value propositions (). Therefore, this study focuses on Generation Y to better understand how digital experiential strategies influence their travel behavior. Behavioral intention refers to an individual’s stated likelihood or readiness to engage in a particular behavior in the future. In the context of tourism, it represents the tourist’s motivation to visit, revisit, recommend, or positively interact with a destination, either physically or virtually. Behavioral intention is often seen as a strong predictor of actual behavior and is influenced by factors such as attitudes, perceived value, satisfaction, and emotional experiences (). It is widely used in consumer behavior and tourism research to assess how various stimuli (experiential value, delight, self-congruence) influence a person’s decision-making process. Thus, behavioral intention acts as a crucial bridge between psychological responses and actual consumer actions in tourism settings.

2.2. Surfing Involvement

Surfing involvement refers to the degree of personal relevance, attention, and cognitive effort that individuals invest when browsing or searching for information online, particularly related to products, services, or experiences. In the tourism context, it captures how actively and emotionally engaged travelers are when exploring digital content about destinations, attractions, or travel services. High surfing involvement is characterized by deeper information processing, more selective attention, and stronger emotional connections to the content, which may influence decision-making and behavioral intentions (; ). Tourists with high involvement are more likely to interact with interactive media, user reviews, virtual tours, and promotional materials that shape their travel perceptions and intentions. As such, surfing involvement plays a key role in digital consumer journeys and in the co-creation of meaningful pre-travel experiences.

The growing digital era allows people to obtain information and knowledge and to trade, including personal needs and hobbies. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, millennials and members of Generation Z are accustomed to surfing the internet to meet their personal needs regarding finding attractive destinations. The whole world was shocked by the historical event caused by the outbreak of COVID-19. Changes in our life, lifestyle, and way of survival occurred rapidly at that time. During the COVID-19 pandemic, travel limitations led to changes in tourism providers, destinations, and visitors. Now, in normal times, younger generations can travel without limits.

Recently, the theory of self-congruence has been used to understand the way in which users engage with the internet to find information about unique destinations that align with their personal brands (). The following indicators for surfing involvement were adapted from (): “I always pay attention to information about amusement park tours”; “finding amusement park information through the internet is important for my daily life”; “searching for theme park information through the internet means a lot to me”; “I am interested in finding information about amusement parks on the internet”; “information about amusement parks on the internet is quite relevant”; “information about amusement parks on the internet caught my attention”; “it’s great to get information about theme parks on the internet.”

2.3. Self-Image Congruence

Self-image congruence refers to the degree of alignment or similarity between an individual’s self-concept (how they see themselves) and the perceived image of a brand, product, or destination. In tourism, self-image congruence occurs when travelers perceive that a destination reflects or enhances their identity, values, or lifestyle. This psychological match fosters stronger emotional attachment, satisfaction, and loyalty, as individuals are naturally drawn to experiences that reinforce their self-identity (). When tourists view a destination as self-congruent, they are more likely to engage with it, form positive evaluations, and exhibit favorable behavioral intentions such as visiting or recommending it. Therefore, self-image congruence plays a vital role in understanding consumer motivation and preference in destination choice and branding. The following indicator of self-image congruence is adapted from (): “if a destination is identical to oneself, it will attract his attention to visit it. If there are constraints on cost, time, and formalities in the form of a visa to go to that destination, I try to do it digitally. The younger generation has not lost their minds. Traveling can be done even if only by following a virtual way. Advances in information technology provide flexibility for businesspeople to create unique services and products. Destination managers are required to transform the disrupting problem. If a destination is identical to oneself, it will attract his attention to visit it. If there are constraints on cost, time, and formalities in the form of a visa to go to that destination, I try to do it digitally to visit it. The younger generation has not lost their minds. Traveling can be done even if only by following a virtual way. Advances in information technology provide flexibility for businesspeople to create unique services and products. Destination managers are required to transform the disrupting problem”. Of course, this process requires stages and time needed to draw conclusions and new experiences, and () added that personal appraisal can be realized through collaboration.

2.4. Experiential Value Co-Creation

Experiential value co-creation refers to the process by which consumers actively participate in shaping their own experiences with a service, product, or destination, creating value not just through consumption but through interaction, personalization, and emotional engagement. In tourism, this involves travelers engaging with digital content, immersive technologies, or destination platforms to construct meaningful, personalized pre-travel or in-destination experiences. The value created is not solely delivered by providers but is co-produced through the involvement, preferences, and perceptions of the tourist (). Experiential value includes emotional, relational, and functional benefits, such as enjoyment, personal relevance, and social connection (). Thus, experiential value co-creation plays a vital role in enhancing customer satisfaction, delight, and behavioral intentions in modern tourism experiences. The indicator adapted from () regarding functional, emotional, and relational components assesses tourists’ perception of value created through interactive, participatory experiences in virtual or physical tourism settings.

To illustrate how experiential value co-creation is implemented in practice, we present the example of IKEA’s digital strategy. Although IKEA is not a tourism business, its innovative use of augmented and virtual reality to facilitate customer engagement and co-design reflects principles highly transferable to tourism destination management. Similar strategies have also been applied in tourism, such as Visit Dubai’s use of virtual reality tools to offer immersive pre-travel experiences. IKEA reported that it made a profit of USD 1.9 billion (; ). IKEA’s strategy is to obtain such a large profit with two precise practices. First, offline sales points are closed to save operational costs. Second, IKEA introduced online shopping with virtual reality and augmented reality. Both tools reliably reduce the difference between offline and online shopping. With these two instruments, prospective buyers can see the furniture in IKEA’s main warehouse and select it virtually and place it in the desired space. This means that shopping can be carried out according to the interior design style, model, suitability of the place, and tastes and desires of the buyer. After everything is in order, the client can then proceed with searching for price information to set a purchase budget and, subsequently, decide to make a purchase ().

IKEA’s strategy is a model that was able to be applied during the COVID-19 pandemic to enjoy interesting and fun tourist destinations. Obstacles to visiting due to crowding restrictions kill the tourism industry. Engagement, such as virtual shopping with virtual travel, is a solution in today’s era that may be tempestuous and is a tendency for the younger generation and the elderly due to time and physical limitations. () proposed that to achieve a competitive advantage, companies should apply service-dominant logic (S-D logic) along with resource and capability perspectives. The pleasure of virtual travel provides hope and then this continues, with offline travel, allowing tourists to obtain more pleasant satisfaction. () found that Unilever has also enjoyed profitability through handless services. The success story of IKEA, for instance, because it is the leading furniture producer worldwide, has succeeded in influencing potential buyers by procuring space, tools, ways, and involvement in choosing and deciding the intention to buy desired goods. Cooperation in conducting trials is an interesting experience for prospective buyers in the sharing economy (; ; ). As digital marketing advances, satisfaction and pleasure in an object can be obtained by surfing the internet. When a person obtains what represents them, they will repeatedly and continuously generate positive reviews of what is identical to them. Such a person will try to interact with others and tell them what they like and what represents them. Furthermore, they will want to carry out value-added cooperation so that other people will also want to work together to obtain goods or visit tourist attractions that they like.

Industrial goods, for example, are sold by marketers using virtual reality technology to sell their products by inviting potential buyers to choose and determine what they need and want (; ; ). In addition to the purpose of selling, marketers of household products, for instance, also aim to provide learning and experience regarding how to make the correct decisions according to the wishes or tastes of prospective buyers. The inclusion of IKEA’s strategy serves as a metaphorical and conceptual anchor to understand how value co-creation can be systematically applied across industries. In the context of tourism, similar co-creation strategies are evident in digital platforms such as Airbnb and Booking.com. These platforms empower travelers to actively participate in shaping their experiences by enabling them to personalize stays, interact with local hosts, share detailed reviews, and contribute content that influences future users. Airbnb, for example, leverages guest–host engagement as a form of co-created value where unique local experiences become part of the service offering (). Similarly, Booking.com utilizes user-generated feedback loops to refine service delivery and align offerings with evolving customer preferences (). These examples underline how co-creation is no longer an abstract concept but is a dynamic, practical strategy embedded in digital tourism ecosystems, enhancing user satisfaction and fostering repeat usage.

2.5. Delight

Customer delight is the objective in the hospitality industry. In many articles, customer delight has been largely deployed as a dependent variable (; ). It is expected that the delighted customer will prefer to stay at the property afterward (; ). Customer delight that generates the passion of joy, thrill, and happiness contributes to an enduring positive memory (; ). Delight indicators are adapted from (, , ); these indicators include positive affect, arousal, surprise, and cognitive and emotional responses beyond satisfaction.

Delight is a positive emotional response that exceeds customer expectations and results in feelings of joy, surprise, and pleasure. It goes beyond simple satisfaction by generating a strong affective reaction that leads to heightened customer loyalty, memorable experiences, and favorable behavioral intentions such as word-of-mouth recommendations and repeat visits (). In the context of tourism, delight occurs when the service experience, whether digital or physical, delivers unexpected value, emotional connection, or personalization that resonates deeply with the traveler. Delight involves a combination of cognitive appraisal and emotional arousal; it is often triggered by service excellence, immersive experiences, or identity alignment with the destination (). Because it enhances customer retention and advocacy, delight is considered a key outcome of experiential value co-creation.

2.6. Hypothesis Development

2.6.1. Surfing Involvement and Experiential Value Co-Creation

In the digital tourism environment, surfing involvement reflects the degree of attention, interest, and emotional engagement that consumers invest when browsing online information related to destinations or travel experiences. According to (), individuals with high involvement process information more deeply, which increases their cognitive and emotional connection to the content. This heightened engagement enhances the opportunity for experiential value co-creation, as tourists actively construct personal meaning and preferences during their online interactions (). The service-dominant logic framework posits that value is co-created through collaborative interactions between consumers and service providers, especially when users contribute knowledge, feedback, or personalized engagement during their digital experience (). Empirical studies also support that deeper online involvement, such as interacting with virtual reality content or destination storytelling, can foster anticipatory emotions, immersion, and co-created value in tourism (; ; ). Therefore, our first proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H1.

Surfing involvement positively affects experiential value co-creation.

2.6.2. Surfing Involvement and Behavioral Intention

Surfing involvement refers to the degree of cognitive and emotional engagement individuals experience while searching for and interacting with online information. In tourism, users who are highly involved in exploring destination-related digital content, such as virtual tours, reviews, and social media, develop a stronger familiarity and connection with the destination, which may shape their future behavior (). Research suggests that higher involvement leads to greater motivation to act, as it enhances information processing and fosters positive attitudes toward the travel decision (). This is supported by the theory of planned behavior (TPB), which posits that behavioral intention is influenced by attitudes formed through prior engagement and evaluation of information (). Therefore, individuals with higher levels of surfing involvement are more likely to form intentions to visit, revisit, or recommend a destination, even in virtual contexts (; ).

People use the internet for different purposes and with different frequencies, especially innovators (). When people engage with a product, surfing the internet can lead to situational and lasting relationships with the product. In this study, involvement is interpreted by individual involvement in the process of searching for information through the internet about tourist destinations that will be visited both virtually and on the spot. The interactions that occur within online platforms, such as social media and websites, can shape the manner in which this information is subsequently referred to. Therefore, our second proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H2.

Surfing involvement positively affects behavioral intention.

2.6.3. Self-Image Congruence and Experiential Value Co-Creation

Self-image congruence refers to the psychological alignment between an individual’s self-concept and the perceived image of a product, brand, or destination. When tourists perceive that a destination reflects their identity, values, or lifestyle, they are more likely to experience emotional connection and immersion in co-created experiences (; ). Such congruence enhances the authenticity and relevance of the experience, thereby contributing to greater experiential value co-creation through emotional, functional, and social dimensions (). According to service-dominant logic, value is co-created not merely through service delivery but through active consumer engagement, which is strongly influenced by the consumer’s identification with the brand or destination (). Empirical studies have shown that travelers with strong self-image congruence are more engaged and derive higher value from participatory experiences, especially in digital tourism and personalized service contexts (; ; ). Spectators of a certain sport may be loyal fans of certain clubs. They will follow the success or failure of a favorite team because they feel that this team represents their personal brand due to congruity between their identity and that of the team (). Similar behavior applies to an individual’s personal brand in relation to a tourist destination. Marketers present digital content so that the members of the target market can see, observe, and choose destinations that match their identity. The use of digital content marketing (DCM) becomes a media link between prospective tourists and tourist attractions. The efficacy of digital content marketing (DCM) can no longer be denied in introducing a product, service, and tourist destination (; ). Regarding the main drivers of self-congruence, () found that they were connectivity, interaction, and real-time dynamic engagement among stakeholders. Recently, awareness and education about the environment have been posited as one of the triggers for digital content marketing (DCM) changes. Therefore, our third proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H3.

Self-image congruence positively affects experiential value co-creation.

2.6.4. Experiential Value Co-Creation and Behavioral Intention

Experiential value co-creation (EVCC) refers to the joint creation of value between consumers and providers through personalized interactions, emotional engagement, and mutual participation in the service experience. This concept has gained prominence in the context of tourism, where tourists are no longer passive consumers but active co-creators of their own experiences (; ). The co-creation process enhances tourists’ perception of authenticity, personalization, and emotional attachment, contributing to meaningful and memorable experiences that influence their behavioral outcomes. Value is no longer derived solely from service attributes but from the experience of engaging with the destination, community, or brand.

Prior studies suggest that when tourists perceive themselves as active participants in co-creating value, their behavioral intentions, such as their intention to revisit, willingness to recommend, and likelihood to engage in positive word-of-mouth communications, are significantly strengthened (; ). The collaborative nature of co-creation empowers tourists and enhances their satisfaction, which positively impacts their loyalty and intention to engage further with the destination or brand. Behavioral intention in this context can be defined as a tourist’s psychological willingness to engage in future behavior such as returning, recommending, or supporting the destination ().

Moreover, the service-dominant logic framework emphasizes the importance of operant resources (skills, knowledge) and operant resources (physical assets) in facilitating value co-creation that enhances experiential value (). This implies that destinations or tourism providers that design participatory, interactive, and personalized experiences are more likely to stimulate favorable behavioral intentions. For example, offering cooking classes, art workshops, or eco-tourism activities allows tourists to immerse themselves and contribute to the service experience, thereby increasing their intention to revisit or advocate for the destination.

The relationship between experiential value co-creation (EVCC) and behavioral intention is also mediated by psychological outcomes such as tourist delight, affective involvement, and perceived self-efficacy (). When individuals feel that they have contributed meaningfully to their travel experiences, their emotional response becomes more intense, enhancing their commitment and loyalty behaviors. This emotional pathway reinforces the notion that value co-creation is not just functional but deeply experiential, rooted in social and affective dimensions that shape behavioral decisions.

This intentional behavior includes visiting, revisiting, recommending, and sharing positive word-of-mouth communication about destinations, especially when the experience has been emotionally engaging and personally meaningful (; ). Furthermore, empirical findings show that the stronger the perceived value from co-creation, the more likely individuals are to form behavioral intentions, as value co-creation enhances both psychological attachment and commitment (; ). Therefore, experiential value co-creation serves as a critical predictor of tourists’ future behavioral responses in digitally mediated and experience-driven tourism services. Thus, our fourth proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H4.

Experiential value co-creation positively affects behavioral intention.

2.6.5. Experiential Value Co-Creation and Delight

Experiential value co-creation (EVCC) emphasizes the collaborative process between consumers and service providers in generating personalized, meaningful, and emotionally engaging experiences. In tourism settings, this involves tourists actively participating in shaping their experiences through interaction, customization, and immersion in local culture and services (). Such participatory engagement is known to enhance the perceived value of the experience beyond utilitarian benefits, fostering emotional connections that are essential for achieving higher levels of customer satisfaction and delight.

Delight, defined as a profoundly positive emotional response that exceeds customer expectations, is often triggered by surprise, novelty, and deeply satisfying service encounters (; ; ). Unlike mere satisfaction, delight reflects a stronger emotional reaction that leads to customer loyalty, favorable word-of-mouth communications, and lasting memories. When tourists are actively engaged in co-creating their travel experience, such as designing their itinerary, interacting with locals, or choosing unique service elements, they are more likely to experience a sense of control, autonomy, and joy, all of which contribute to delight.

Empirical research supports the argument that co-creation enhances emotional outcomes. For instance, () found that tourists who participated in co-creative activities reported significantly higher levels of delight and emotional fulfilment compared with those in passive consumption settings. The personalized nature of co-creation enhances the relevance and resonance of experience, fostering positive emotions and affective evaluations that transcend standard satisfaction. This aligns with ’s () experiential economy theory, which argues that memorable and delightful experiences stem from customer participation and immersion.

Furthermore, research by () demonstrates that the social dimension of co-creation (interacting with other tourists or locals) plays a pivotal role in amplifying emotional intensity and delight. Social interactions add richness to the experience, contributing to emotional contagion, shared enjoyment, and affective reinforcement. These factors are particularly important in tourism, where emotional outcomes often determine overall experience quality and influence future behavioral intentions.

Based on the theoretical foundations and empirical evidence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that experiential value co-creation significantly contributes to tourist delight. This relationship is mediated through personalized engagement, emotional resonance, and perceived authenticity of the experience. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

Experiential value co-creation positively affects delight.

2.6.6. Delight and Behavioral Intention

Customer delight is usually described in the marketing literature and consumer behavior literature as a positive emotion experienced by consumers in response to consumer expectations being exceeded at a high level (). The conceptualization of customer delight as an emotional or affective response to customer experience () originated in the emotion literature with an emphasis on the primary emotion model ().

Based on a study () focusing on the distinction between attributes, namely satisfaction and delight, a scale was developed to measure the extent of satisfaction and delight in a customer experience. () defined customer satisfaction as “going beyond the satisfaction of providing what can be described as a pleasant experience for the client”. () confirmed that customer satisfaction is based on emotions, needs, and disconfirmation theory. () explained that customer satisfaction is frequently associated with emotional responses such as surprise and delight. While meeting or exceeding customer needs typically results in satisfaction, combining delight with surprise tends to generate greater happiness (). According to (), this sense of excitement originates from fulfilling consumers’ basic needs and is inherently linked to their emotional state. Similarly, () and () identified a strong relationship between product evaluation, emotional arousal, positive affect, and satisfaction, emphasizing that arousal significantly shapes the way evaluations influence emotions and, ultimately, satisfaction. Based on disconfirmation theory, exceeding customer expectations enhances satisfaction levels (). Moreover, () and () highlight that delighting customers can lead to long-term business profitability ().

Within the theory of reasoned action (TRA), two key determinants influence behavior changes in beliefs about the consequences of performing or not performing a specific behavior and perceptions of whether others will approve or disapprove of that behavior (; ). The theory of reasoned action (TRA) posits that individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that secure desirable outcomes and are supported by social approval (; ). This model predicts consumer intentions based on normative attitudes and beliefs, with a central premise being that behavioral intention reflects a person’s willingness and effort to perform a particular behavior (). Although customer delight has been recognized as a relatively new construct with limited empirical exploration (), existing research indicates that high customer satisfaction and positive experiences directly foster favorable behavioral intentions toward service providers (; ). () and () further assert that satisfaction strongly influences behavioral intentions, whereas dissatisfaction often leads to negative actions such as customer churn or negative word-of-mouth communications. From a service marketing perspective, especially in emerging markets, () emphasize the need for deeper investigation into the links between employee competence, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions.

In tourism, behavioral intention refers to actions repeatedly undertaken that develop into habits, curiosity, and a consistent desire to visit. () and () note that when a destination or brand aligns closely with consumer identity, the likelihood of initial and repeat visitation increases, which is closely tied to visitor satisfaction (). In digital contexts, networking behavior may differ from face-to-face interactions due to the unique properties of online technologies. Prior research identifies smart information systems and smart sightseeing as critical factors in strengthening behavioral intention (; ). Furthermore, frequent information seeking can reinforce the intention to visit a particular destination (), while augmented reality technologies enhance visibility and engagement (). Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Delight positively affects behavioral intention.

2.6.7. Experiential Value Co-Creation and Delight as Mediation

Self-image congruence refers to the psychological compatibility between a consumer’s self-concept and the image of a destination, product, or experience. In tourism contexts, such congruence enhances the tourist’s emotional attachment, which fosters their desire to co-create experiences that align with their personal identity. These aligned experiences promote experiential value co-creation, as individuals become more immersed in the service process, thereby enhancing the perceived quality of their involvement (). The emotional fulfillment derived from these co-creative interactions often results in delight, a heightened emotional state where expectations are surpassed. Together, these elements create a holistic pathway toward behavioral intentions such as revisiting, recommending, or sharing positive experiences.

Empirical studies confirm that both experiential value co-creation and delight serve as critical mediators in converting self-image congruence into behavioral intention. Tourists who experience delight through identity-aligned experiences report stronger intentions to maintain a relationship with the service provider or destination (). Experiential value acts as the operational mechanism, while delight functions as the emotional reinforcement. This dual mediation emphasizes both the cognitive and affective dimensions of the tourist experience. Therefore, it is hypothesized that experiential value co-creation and delight jointly mediate the relationship between self-image congruence and behavioral intention.

Experiential value co-creation occurs when consumers actively participate in the formation of service experiences, particularly through personalization and interaction. In tourism, this manifests in engaging with local culture, customizing itineraries, or contributing to service delivery, which enhances perceived control and satisfaction (). These interactive experiences heighten the probability of eliciting emotional responses such as delight. Delight, defined as an emotional state where the experience exceeds expectations, serves as a pivotal link between cognitive involvement and affective loyalty. The transformation of co-created value into delight underpins tourists’ favorable post-travel behaviors.

Research shows that delight strengthens the psychological connection between the traveler and destination, amplifying behavioral intentions such as revisitation and electronic word-of-mouth communication (). Without emotional reinforcement, co-creation may not be sufficient to trigger commitment. Thus, delight acts as a necessary affective pathway for ensuring the full realization of experiential value’s behavioral impact. This sequential mediation reflects the importance of emotional outcomes in value-driven tourism strategies. Accordingly, it is proposed that delight mediates the relationship between experiential value co-creation and behavioral intention.

Surfing involvement refers to the degree to which surfing is personally important, engaging, and emotionally significant to an individual. Tourists with high involvement are likely to actively seek immersive and co-created experiences at surf destinations (). Their deep emotional investment encourages them to interact with the environment, instructors, and community, resulting in experiential value co-creation. This participatory experience is often characterized by novelty and autonomy, which elevate emotional responses. Delight emerges because of meaningful and personally relevant co-creative experiences, enhancing the tourism experience’s memorability.

The linkage between surfing involvement and behavioral intention is reinforced through the dual mediators of co-creation and delight. Tourists who feel both empowered and emotionally fulfilled are more likely to exhibit loyalty behaviors such as repeat visits and positive advocacy (). Active engagement satisfies both cognitive and affective needs, creating a comprehensive experience. These findings suggest a two-step mechanism where surfing involvement first drives co-creation, which then triggers delight and, finally, leads to behavioral intention. Thus, this hypothesis proposes that experiential value co-creation and delight jointly mediate the relationship between surfing involvement and behavioral intention.

Self-image congruence creates a sense of psychological alignment between a tourist’s identity and the image of a destination or service, which enhances emotional commitment. This alignment increases the likelihood of participation in co-creative processes such as choosing activities that resonate with personal values (). Through such interactions, tourists gain experiential value, which transforms a passive service encounter into a participatory and meaningful experience. These experiences, in turn, strengthen the sense of belonging and perceived authenticity. As the perceived value of the co-created experience rises, so does the intention to revisit or recommend the destination.

Co-creation serves as the bridge that converts identity fit into behavioral loyalty. Tourists derive personal significance from shaping their travel experiences, which validates their self-concept. Studies confirm that co-created value enhances emotional attachment and trust, both of which are antecedents of behavioral intention (). This process highlights the instrumental role of experiential value in realizing the benefits of identity-based marketing. Therefore, it is hypothesized that experiential value co-creation mediates the relationship between self-image congruence and behavioral intention.

Tourists highly involved in surfing often seek experiences that reflect their personal values and skills. Their psychological engagement predisposes them to interact with the environment and service providers, thus promoting value co-creation (). These co-creative processes offer customization, learning, and social interaction opportunities, all of which contribute to experiential value. The sense of agency and fulfilment derived from this engagement increases perceived authenticity and satisfaction. Consequently, the experience becomes not only enjoyable but also self-validating, reinforcing commitment to the destination.

Experiential value co-creation acts as a mediator by transforming activity-based involvement into behavioral responses. Through co-created experiences, surfing enthusiasts find greater emotional and cognitive satisfaction, which motivates behavioral intention (). This mechanism underscores the role of engagement as both a driver and a reinforcer of loyalty. Tourists are more likely to revisit or recommend destinations where they felt deeply involved and valued. Hence, this hypothesis posits that experiential value co-creation mediates the relationship between surfing involvement and behavioral intention.

The compatibility between a tourist’s identity and the brand or destination image fosters a sense of belonging, which enhances emotional responses. This congruence increases motivation to co-create experiences that reflect personal identity (). As tourists engage more deeply in co-creative practices, they gain autonomy and personal relevance, which amplifies emotional outcomes. The experiential value generated through these interactions leads to a heightened sense of appreciation. Consequently, delight arises when self-congruent experiences are not only met but exceeded.

Experiential value co-creation mediates the path between identity alignment and delight by acting as the functional mechanism through which emotional outcomes are produced. The more a tourist feels involved in shaping their journey, the more likely they are to feel surprised and emotionally fulfilled (). These findings suggest that delight is not a direct result of identity fit but a consequence of meaningful engagement. The co-creative process enhances the emotional depth of the experience, leading to higher levels of delight. Therefore, this hypothesis proposes that experiential value co-creation mediates the relationship between self-image congruence and delight.

Surfing involvement reflects deep emotional and cognitive investment in the activity, which motivates tourists to seek personally relevant and interactive experiences. These individuals are more inclined to engage with local communities, instructors, and other surfers, thereby facilitating experiential value co-creation (). The immersive and participatory nature of these experiences leads to greater emotional resonance. This process aligns well with the emotional response of delight, which is often triggered by meaningful and surprising experiences. When tourists feel that their involvement has shaped the outcome, the experience becomes more emotionally rewarding.

Experiential value co-creation acts as a catalyst in converting involvement into delight by offering opportunities for expression, creativity, and agency. This interaction transforms a recreational activity into an emotionally charged event that resonates deeply with personal values (). Delight, in this context, is not only about enjoyment but also about fulfilment and self-validation. Empirical research supports that value co-creation enhances the affective dimensions of tourism, especially in adventure and sports-based contexts. Thus, it is hypothesized that experiential value co-creation mediates the relationship between surfing involvement and delight.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7.

Self-image congruence has a positive and significant effect on behavioral intention mediated by experiential value co-creation and delight.

H8.

Experiential value co-creation positively affects behavioral intention mediated by delight.

H9.

Surfing involvement has a positive and significant effect on behavioral intention mediated by experiential value co-creation and delight.

H10.

Self-image congruence positively affects behavior intention mediated by experiential value co-creation.

H11.

Surfing involvement positively affects behavior intention mediated by experiential value co-creation.

H12.

Self-image congruence positively affects delight mediated by experiential value co-creation.

H13.

Surfing involvement positively affects delight mediated by experiential value co-creation.

However, researchers assume that there are still many other factors, consisting of several subjects and reasons, that drive behavior and intention (; ; ). An overwhelming desire, ease of using advanced technology, and the similarity of one’s identity with that of a tourist attraction, for example, will increase behavior and intention (). A person’s self-congruence determines whether their identity is recognized by others as synonymous with that of an object, attraction, or interesting tourist destination, of course.

Excitement can also be generated by the experience of cooperation. The experience between people who have something in common in enjoying something or representing something can cause someone to become a fanatic. The same can occur when enjoying the same experience of a destination or tourist attraction. They will feel the same happiness in surfing amazing creations, ruins, and destinations that lead to behavioral intention (). (), combining service-dominant logic theory and social exchange theory, found that value co-creation had a desirous sharing behavior.

3. Methodology

The research methodology outlines the framework for planning strategies and procedures used in the study. The research design specifies the approaches for data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results. It refers to the systematic methods and procedures applied to obtain and evaluate quantitative data. This study adopted a quantitative research design.

3.1. Research Approach

This subsection elaborates on the specific quantitative methods and techniques applied in the study. The quantitative approach focuses on objectively measuring facts, utilizing appropriate measurement instruments, and clarifying the relationships among variables (). Studies have adopted this approach to describe the opinions, attitudes, and thoughts of specific individuals concerning an examined phenomenon and to describe the individual providing such a description. The main quantitative data collection instrument adopted in this study was a questionnaire that has been validated. This study employed a quantitative approach using a structured questionnaire as the primary data collection instrument. The questionnaire items were developed by adapting established scales from prior research, grounded in service-dominant logic theory (), self-congruence theory (), and relevant constructs in experiential value co-creation and customer delight (; ) Each construction was operationalized based on previous empirical studies, and items were contextualized for online travel and virtual tourism experiences.

A pre-test was conducted with a panel of three academic experts and ten representatives from the target population to assess item clarity, relevance, and cultural suitability. Following feedback, minor modifications were made to ensure clarity and content validity. The final questionnaire was pilot-tested and demonstrated strong reliability and validity, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values above 0.7.

3.2. Population and Sampling Technique

We focus on the young generation with ages of 20 to 25. People of this age are assumed to be the correct subjects for this type of research—research that demands that the subject has a habit of surfing the internet. The subjects of this research consist of students domiciled in Jakarta (80%) and Semarang (20%). Following the purposive sampling technique, the valid sample was 307 out of the 350 questionnaires distributed (). The target population consisted of members of Generation Y (aged 20–25) residing in Jakarta and Semarang. Given their high engagement with digital platforms and virtual tourism content, they were deemed appropriate for the study objectives. Purposive sampling was used to select participants who met the inclusion criteria (age, location, and active internet use related to tourism).

The online questionnaire was distributed via university mailing lists, official student social media groups, and email invitations with the support of academic partners in Jakarta and Semarang.

Out of 350 distributed questionnaires, 307 were completed and deemed valid for analysis, resulting in a response rate of 87.7%. Participation was voluntary, and data were screened for completeness and consistency.

3.3. Data Analysis

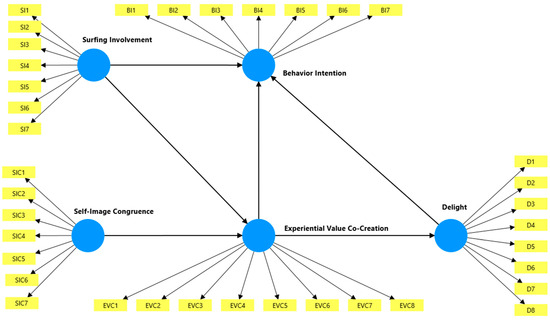

Data analysis was carried out by PLS-SEM using SmartPLS 4.0. Both the outer and inner models were tested for each construct on discriminant validity and multicollinearity. The path coefficient and predictive relevance were attained to test the hypotheses and the goodness of fit (). The structural model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural model.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Validity and Reliability of the Measures

The data entered in the SmartPLS model constructs is subsequently analyzed to assess validity and reliability. This evaluation may be performed iteratively until all indicator loading factor values exceed the threshold of 0.70, as recommended by (). Indicators with loading factor values below 0.70 are eliminated to enhance the model’s overall validity and reliability. The final SmartPLS results, which meet the established validity and reliability criteria, are presented in the following figure and table.

Convergent validity is assessed by examining item reliability, which is reflected in the loading factor value. The loading factor represents the correlation between the score of a specific question item and the score of the construct indicator intended to measure that construct. A loading factor value above 0.7 is generally considered valid. Nevertheless, () note that for an initial assessment of the loading factor matrix, a value of around 0.3 can be regarded as meeting the minimum threshold. A loading factor value of approximately 0.4 is typically regarded as acceptable, while values above 0.5 are generally deemed significant. In this research, a threshold of 0.7 was adopted as the criterion. Following data analysis with SmartPLS 4.0, the resulting loading factor values are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Convergent measurement items, reliability, and validity.

Based on the SmartPLS analysis results presented in Table 2, all indicators for each variable in this study achieved loading factor values exceeding 0.70, indicating that they satisfy the criteria for convergent validity.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity test with cross-loading criteria.

Discriminant validity is assessed by examining the cross-loading values of the construct measurements. Cross-loading values indicate the strength of the correlation between each construct and its respective indicators, as well as the indicators of other construct blocks. A measurement model demonstrates good discriminant validity when the correlation between a construct and its indicators is higher than the correlation with indicators from other construct blocks. Following data processing with SmartPLS 4.0, the cross-loading results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. The results in Table 3 reveal that the correlation values between each construct and its indicators are generally higher than their correlations with other constructs, indicating that all latent constructs or variables possess adequate discriminant validity. In addition to evaluating convergent and discriminant validity, the outer model can also be assessed for construct reliability using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values. A construct is considered reliable when both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability exceed 0.7 ().

Table 3.

VIF value.

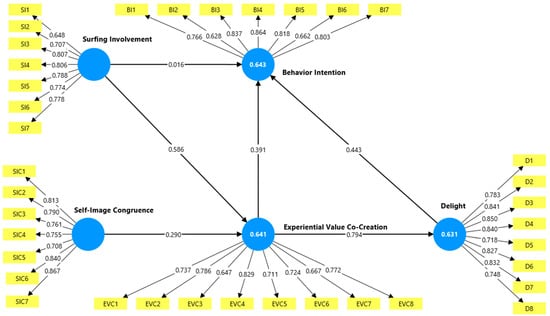

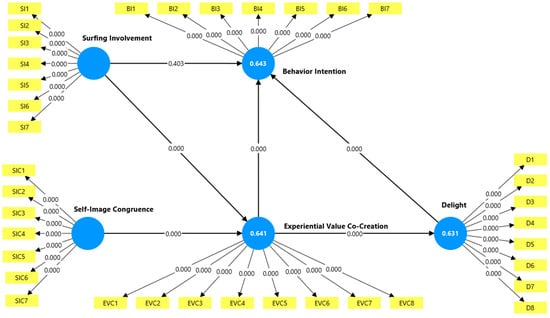

Figure 2.

Outer model.

The results of the SmartPLS output in Table 2 indicate that the composite reliability values for all constructs exceed 0.70. With the resulting value, all constructs have good reliability according to the required discriminant value limit.

4.1.1. Assessment of Structural Model

Once the outer model has been validated, the next step is to test the inner model (structural model). The evaluation of the inner model involves assessing multicollinearity.

Based on Table 3, the outer model analysis requires the assumption that no multicollinearity issues are present. Multicollinearity occurs when there is a correlation, or a strong intercorrelation, among the indicators. The limitation is a correlation value of >0.9, which is usually indicated by the value of the variance-inflating factor (VIF) in the indicator level being > 5 ().

The SmartPLS results in Table 3 show satisfactory correlation among variables (i.e., VIF < 5.00), which means that multicollinearity is not an issue in the model. The value of VIF must be less than 5 because if it is more than 5, it indicates collinearity between constructs ().

Variant analysis (R2), or the determination test, is carried out to determine the magnitude of the influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable (the value of the coefficient of determination). Please see Table 4 for the results of this analysis.

Table 4.

Analysis of R-squared and adjusted R-squared.

The behavioral intention variable can be explained by the variables of surfing involvement, self-image congruence, experiential value co-creation, and delight by 64.3%, while 35.7% is explained by other factors. Furthermore, the delight variable can be explained by the variables of surfing involvement, self-image congruence, experiential value co-creation, and behavioral intention by 63.1%, while 36.9% is explained by other factors. Furthermore, the experiential value co-creation variable can be explained by the variables of surfing involvement, self-image congruence, behavioral intention, and delight by 64.1%, while 35.9% is explained by other factors. R-square value criteria of 0.75, 0.50, or 0.25 are described with substantial, medium, and weak values (). Subsequently, the value of R-square indicates if the model has medium strength.

In addition to assessing whether there is a significant relationship between variables, researchers must also use effect size or f-squared to assess effect size between variables (). An f-value of 0.02 is small, a value of 0.15 is medium, and a value of 0.35 is large. Values less than 0.02 may be ignored or considered to have no effect ().

Based on Table 5, the size of the influence of the behavioral intention variable on delight is 0.200, indicating that the influence is moderate. The influence of the delight variable on experiential value co-creation is 1.780, indicating a great influence. The magnitude of the two-variable behavioral intention in relation to experiential value co-creation is 0.111, indicating moderate influence. The size of the variable of experiential value co-creation relative to that of self-image congruence is 0.142, demonstrating moderate influence. The variable of experiential value co-creation in relation to surfing involvement is 0.579, demonstrating great influence. The magnitude of the variable of behavioral intention in relation to surfing involvement is 0.000, indicating no influence.

Table 5.

Results of F-square analysis.

Based on Table 6, the Q2 effect size was calculated to evaluate the contribution of exogenous constructs to the Q2 value of endogenous latent variables (). Q2 serves as an indicator of the model’s predictive relevance for the endogenous latent variables and is obtained through the blindfolding procedure. All Q2 values were positive and greater than zero (BI = 0.373; D = 0.403; EVC = 0.341), indicating that the model possesses predictive relevance for the two endogenous constructs. In SEM, a Q2 value greater than zero for a reflective endogenous construct signifies that the path model has predictive relevance for that construct ().

Table 6.

Prediction accuracy analysis results.

Based on Table 7, the degree of model fit or model accuracy indicates how capable the developed model is of explaining data. In model fit testing, based on the results of PLS model estimation, standardized root mean square (SRMR) for structural models is 0.005, which is less than the threshold of 0.8 (). Thus, the current PLS path modeling has a corresponding overall fit.

Table 7.

Results of analysis of model fit.

4.1.2. Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is conducted based on the results of testing the inner model (structural model), parameter coefficients, and t-statistics. To determine whether one hypothesis, among others, can be accepted or rejected, one considers the significance value between constructs, t-statistics, and p-values. In this study, hypothesis testing was carried out with the help of SmartPLS 4.0 software. These values can be observed from the results of bootstrapping. The rules of thumb used in this study were t-statistics > 1.96, with significance reached with a p-value of 0.05 (5%) and a positive beta coefficient. The value of testing this research hypothesis is shown in Table 8, and the results of this research model are shown in Figure 3.

Table 8.

Direct and indirect effects.

Figure 3.

Inner model.

The first hypothesis tests whether surfing involvement positively affects behavioral intention. The test results show that there was no significant effect. The test results show a value of the beta surfing involvement coefficient on behavioral intention of 0.016 and a t-statistic of 0.252, or <1.96, and p-values of 0.801, or >0.05, so that the first hypothesis was rejected. This proves that SI is not proven to have a positive influence on BI.

The second hypothesis examines whether surfing involvement positively affects experiential value co-creation. The test results show a value of the beta coefficient of surfing involvement to experiential value co-creation of 0.586, a t-statistic of 10.367, and a p-value of 0.000. From these results, the t-statistic was deemed significant. Because it is >1.96, with a p-value of <0.05, the second hypothesis is accepted. This proves that surfing involvement is proven to have a positive influence on experiential value co-creation.

The third hypothesis examines whether self-image congruence positively affects experiential value co-creation. The test results show the value of the beta surfing involvement coefficient against experiential value co-creation, as it amounted to 0.290, with a t-statistic of 4.824 and a p-value of 0.000. From these results, one can conclude that the value is statistically significant. Because it is greater than 1.96, with a p-value <0.05, the third hypothesis is accepted. This proves that self-image congruence has a positive influence on experiential value co-creation.

The fourth hypothesis examines whether experiential value co-creation positively influences behavioral intention. The test results show a value of the beta experiential value co-creation coefficient of behavioral intention of 0.0391, a t-statistic of 5.036, and a p-value of 0.000. From these results, one can observe that the t-statistic is significant. Because the t-value is >1.96, with a p-value of <0.05, the fourth hypothesis is accepted. This proves that experiential value co-creation has a positive influence once experiential value co-creation occurs.

The fifth hypothesis tests whether experiential value co-creation positively affects delight. The test results show a value of the beta experiential value co-creation coefficient of delight of 0.794, a t-statistic of 26.601, and a p-value of 0.000. From these results, one can observe that the value is statistically significant. Because it is >1.96, with a p-value of <0.05, the fifth hypothesis is accepted. This proves that experiential value co-creation has a positive influence on delight.

The sixth hypothesis examined the positive effect of delight on behavioral intention. The analysis yielded a beta coefficient of 0.443, a t-statistic of 6.840, and a p-value of 0.000, indicating statistical significance. As the t-statistic exceeds 1.96, and the p-value is below 0.05, the sixth hypothesis is supported. This finding confirms that delight has a positive impact on behavioral intention.

The seventh hypothesis examines whether self-image congruence positively affects experiential value co-creation, which positively affects behavioral intention through delight. The test results show a beta coefficient value of self-image congruence to experiential value co-creation to behavioral intention through delight of 0.102, a t-statistic of 4.062, and a p-value of 0.000. This result is statistically significant. Because it is greater than 1.96, with a p-value of less than 0.05, the seventh hypothesis is accepted. This proves that self-image congruence has a positive influence on experiential value co-creation, which positively affects behavioral intention through delight.

The eighth hypothesis examines whether experiential value co-creation positively influences behavioral intention through delight. The test results show a value of the beta experiential value co-creation coefficient on behavioral intention through delight of 0.352, a t-statistic of 4.062, and a p-value of 0.000, indicating statistical significance. Because it is greater than 1.96, with a p-value of less than 0.05, the eighth hypothesis is accepted. This proves that experiential value co-creation has a positive influence on behavioral intention through delight.

The ninth hypothesis examines whether surfing involvement positively affects experiential value co-creation and positively affects behavioral intention through delight. The test results show a beta coefficient value of self-image congruence to experiential value co-creation to behavioral intention through delight of 0.206, a t-statistic of 5.324, and a p-value of 0.000, indicating statistical significance. Because it is >1.96, with a p-value of <0.05, the ninth hypothesis is accepted. This proves that surfing involvement has a positive influence on experiential value co-creation and positively affects behavioral intention through delight.

The tenth hypothesis tests whether self-image congruence positively affects behavioral intention through experiential value co-creation. The test results show a value of the beta experiential value co-creation coefficient of behavioral intention through delight of 0.113, a t-statistic of 3.021, and a p-value of 0.003, indicating statistical significance. Because it is greater than 1.96, with a p-value of less than 0.05, the eighth hypothesis is accepted. This proves that self-image congruence has a positive influence on behavioral intention through experiential value co-creation.

The eleventh hypothesis tests whether surfing involvement positively influences behavioral intention through experiential value co-creation. The test results show a value of the beta surfing involvement coefficient on behavioral intention through experiential value co-creation of 0.229, a t-statistic of 4.885, and a p-value of 0.000, indicating statistical significance. Because it is >1.96, with a p-value of <0.05, the eleventh hypothesis is accepted. This proves that surfing involvement exerts a positive influence on behavioral intention through experiential value co-creation.

The twelfth hypothesis tests whether self-image congruence positively influences delight through experiential value co-creation. The test results show a value of the beta surfing involvement coefficient on behavioral intention through experiential value co-creation of 0.231, a t-statistic of 4.730, and a p-value of 0.000, indicating statistical significance. Because it is >1.96, with a p-value of <0.05, the eleventh hypothesis is accepted. This proves that self-image congruence has a positive influence on delight through experiential value co-creation.

5. Conclusions

The results of the empirical analysis carried out in this research are very useful. Of the twelve hypotheses proposed, one hypothesis was rejected, and the other eleven were accepted. The hypothesis that was rejected was the hypothesis regarding the positive relationship between surfing involvement and behavioral intention. These results go beyond previous predictions because continuously surveying information can influence the behavioral intention of a technology user. This hypothesis was not accepted because the participants’ involvement in the survey was too diverse: thus, consumers did not experience deep enough involvement with a particular tourist attraction, especially tourist attractions visited online. Another very useful research finding is the acceptance of the hypothesis concerning the relationship between surfing involvement and experiential value co-creation. When tourists surf to find out which tourist location they want to visit, they can find information that provides an initial experience before visiting the tourist location. Of course, this experience is supported by conformity with the image that tourists have. Tourists have their own preferences in choosing tourist attractions according to their tastes and image, so it is logical that self-image congruence influences experiential value co-creation. Behavioral intention can also be influenced by experiential value co-creation. The value of tourists’ experience can direct behavioral intention in choosing tourist locations and choosing accommodation. Tourists’ experiences when surfing the internet provide motivation to visit a place if the initial experience makes the tourist interested.

Experiential value co-creation also influences customer delight. Feelings of joy and happiness can occur via surfing experiences that produce valuable experiences. With valuable experiences, tourists feel happy even before visiting tourist attractions. Feelings of pleasure can lead tourists toward changes in behavioral intention, and thus, it is logical that the findings of this research show that customer delight can influence behavioral intention. The experience received by tourists will crystallize in the tourist’s memory if it is in accordance with the tourist themself. The similarity of the image of a tourist location with its image in tourists’ minds can lead tourists to valuable experiences.

This research also examines the role of delight in mediating the relationship between experiential value co-creation and behavioral intention, and the results are significant. Valuable experiences provide tourists a feeling of pleasure, thereby leading tourists to changes in behavioral intention. The more meaningful the experience gained, the more enjoyable tourists will feel, and this will increase their behavioral intention toward the tourist attractions they visit, even if only through a device screen. A mediating influence that is also discussed in this research is that of experiential value co-creation and delight mediating the relationship between surfing involvement and behavioral intention. Continuing from the previous mediation relationship, experiential value co-creation can be obtained from the surfing involvement carried out by tourists. The easier to obtain and the more complete the information about tourist attractions is, the more meaningful the experience gained will be; thus, it is not surprising that this can increase delight and ultimately increase behavioral intention. Furthermore, this research also proves the importance of experiential value co-creation in influencing the relationship between self-image congruence and behavioral intention. Tourists who feel that a tourist location matches their image will increase their behavioral intention. Tourists have different tastes and images regarding tourist locations; the suitability of a tourist destination location with their personal image will further increase their interest in visiting the tourist location. Apart from having an impact on the relationship between self-image congruence and behavioral intention, experiential value co-creation also influences the relationship between surfing involvement and behavioral intention. While surfing in cyberspace, tourists obtain information and abstract images about the tourist location they are going to. The information obtained while surfing the internet will provide experiences that motivate tourists to be interested in visiting tourist locations. Therefore, it is logical that experiential value co-creation can be a bridge between surfing information and value co-creation. An additional benefit of experiential value co-creation is that it can mediate self-image congruence toward delight.

6. Implications and Future Research

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the sample was restricted to Generation Y individuals residing in Jakarta and Semarang, which may limit the generalizability of the findings across different generational cohorts and geographic regions. Future studies could expand the demographic coverage to include Gen Z and older age groups across multiple provinces or countries. Second, the research relied on self-reported data collected using structured questionnaires: the results may be influenced by social desirability bias. Lastly, although the study used validated measurement instruments, it focused on virtual tourism, which might not capture all aspects of actual tourist behavior in physical contexts.

Experience can be interpreted differently by each actor involved depending on the preferences, tastes, and knowledge of the recipient of the experience (). This research offers a new concept, namely experiential value co-creation, to explain how tourists’ behavior in surfing the internet can influence behavior intention. This research certainly has managerial implications which are very useful for increasing behavioral intention, especially in the tourism sector. Tourist attraction managers need to pay attention to content that discusses tourist destinations. Complete and accurate information will be very useful in increasing the desire to visit tourist locations. Apart from this, the experience gained while surfing the internet can also be used as a key to increasing behavioral intention. Providing a dedicated website may be beneficial in improving the tourist experience.

This research was structured with a service-dominant logic perspective, in which there are several factors involved in creating useful value, for example, in the form of pleasant experiences. This research provides additional knowledge regarding service-dominant logic, where the experiences of tourists can even occur through online channels. This research also provides various insights regarding the emergence of experiences originating from online channels. Future research on more specific tourist destinations and a wider range of respondent locations would be very useful for generalizing research results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., J.J. and G.P.R.; methodology P.S., J.J. and G.P.R.; software, P.S. and J.J.; validation, P.S. and J.J.; formal analysis, P.S. and J.J.; investigation, P.S., J.J. and G.P.R.; resources, P.S., J.J., G.P.R. and A.P.S.S.; data curation, P.S. and G.P.R.; writing—original draft, P.S. and J.J.; writing—review and editing, P.S., J.J. and G.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Muria Kudus, Indonesia (Approval Code No. 413/LPPM.UMK/B.02.42/VII/2025, with the approval granted on 23 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the respondents who participated in this research and who were willing to be data sources.

Conflicts of Interest