Abstract

Vanilla planifolia is an endangered orchid of significant commercial relevance, primarily valued for the natural vanillin derived from its cured fruits. However, its global production faces critical threats due to its limited genetic variability and high susceptibility to phytopathogens, particularly vanilla wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae. This review synthesizes the recent advances in plant biotechnology, evaluating the efficacy of in vitro culture systems, plant growth regulators, and the implementation of semi-automated temporary immersion systems, as compared to traditional semisolid methods. Emphasis is placed on the pivotal role of physical factors, such as LED lighting, and the symbiotic associations with orchid mycorrhizal fungi to enhance plant growth and vigor. By synthesizing advanced in vitro regeneration protocols, this study establishes a strategic guide for the mass production of high-quality disease-free plantlets. Finally, the impact of these biotechnological tools on ex situ conservation at institutions such as the Clavijero Botanical Garden is discussed, aiming to support the sustainability of the vanilla industry and preserve Mexico’s biological heritage.

1. Introduction

The genus Vanilla Plum. ex Mill. (Orchidaceae) comprises over 110 species, among which V. planifolia Andrews, V. pompona Schiede, and V. tahitensis J.W. Moore hold primary economic significance [1]. As the most extensively cultivated and productive species, V. planifolia serves as the principal source of natural vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde). This compound is considered the second most valuable spice worldwide, after saffron [1]. Beyond its application in the food industry, vanillin functions as a masking agent in pharmaceutical formulations and personal care products [2]. Although vanillin can be produced synthetically or via biotechnological precursors such as ferulic acid, extraction from cured fruits remains the sole natural method, a distinction that confers significantly higher market value and supports the economies of various producing regions [2,3].

Mexico, specifically the Totonacapan region encompassing parts of Puebla and Veracruz, is recognized as the center of origin for vanilla [4]. Its use in rituals and as a flavoring for cacao-based beverages dates back to the Totonaca and Aztec civilizations [4,5,6]. While the Totonacs established the first plantations in 1767 [5,6], the global dissemination of vanilla began in 1520 following its introduction by the Spanish to Europe, Africa, and Asia [7,8]. Early international cultivation faced substantial challenges related to fruiting, primarily due to abiotic stressors and the absence of natural pollinators. Cultivation practices were finally stabilized between 1793 and 1875 through the implementation of manual pollination techniques on Reunion Island [8,9]. Despite its Mexican origins, contemporary commercial production is predominantly in Madagascar, Indonesia, and India, with Mexico contributing only a minor fraction to the global output [5,8,10,11].

The sustainability of the vanilla industry currently faces significant challenges, particularly as V. planifolia is designated as an endangered species within its native habitat [12]. Worldwide production is substantially hindered by the limited diversity of genetic material, as propagation has predominantly been achieved vegetatively from a restricted number of individuals over many years, resulting in a markedly narrow genetic pool base [13]. This lack of genetic diversity heightens the vulnerability of plantations to abiotic stress and phytopathogenic threats, particularly wilt disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae [14]. Under these circumstances, conventional cultivation methods cannot maintain phytosanitary health or satisfy increasing global demand. Therefore, the development of biotechnological tools is essential for both commercial revitalization and ex situ conservation efforts. Institutions such as the Clavijero Botanical Garden are instrumental in integrating in vitro propagation protocols with conservation strategies to protect this threatened germplasm.

The primary objective of this review is to synthesize recent advances in in vitro propagation and ex situ conservation approaches for V. planifolia. This article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the biological stages involved in the five micropropagation stages, from mother plant selection to greenhouse acclimatization. Section 3 provides an evaluation of the effectiveness of new culture systems, especially comparing semi-automated temporary immersion systems (TISs) with traditional semisolid methods, and an analysis of molecular marker techniques used to ensure genetic stability. Section 4 discusses the incorporation of orchid mycorrhizal fungi (OMF) to enhance plant resilience and metabolic quality. Finally, Section 5 discusses how these protocols impact the strategic conservation and sustainable use of this important plant genetic resource.

2. Vanilla planifolia Botanical Description

Vanilla is a monopodial, terrestrial, and climbing plant reaching up to 20 m, characterized by succulent stem and adventitious aerial roots. The leaves are succulent and oblong–lanceolate or acuminate, with petioles measuring 9 to 23 cm in length [15]. The inflorescence is racemose, bearing between 20 and 25 large yellowish-green flowers [4]. Each flower comprises three sepals and three petals, with one petal modified into a 6 cm labellum. The stamens contain two pollinia each, situated within a structure known as the rostellum, which covers the stigma and ovary [11]. The fruits are cylindrical pods, up to 25 cm in length and 5 to 15 mm in diameter, dark green in color, and turning brown upon capsule maturation (Figure 1). The seeds have a perimeter ranging from 0.556 to 0.630 mm and are dark brown [9,10].

Figure 1.

Morphological characteristics and cultivation systems of Vanilla planifolia Andrews. (A) Adult specimen exhibiting a monopodial climbing habit during the reproductive stage, showing racemose inflorescences and developing pods. (B) Plant established in a traditional or semi-intensive cultivation system, utilizing a citrus tree (Citrus sp.) as a phorophyte or living tutor for support and growth. (C) Detail of the yellowish-green flowers, displaying the modified labellum characteristic of this orchid species. (D) Fleshy cylindrical fruits (pods) in an advanced stage of maturity, reaching lengths of up to 25 cm prior to harvest, which typically occurs 6 to 9 months after pollination. Photos courtesy of David Moreno.

In Mexico and Central America, V. planifolia inhabits hot and humid subtropical and evergreen-deciduous forests. It is cultivated at elevations ranging from 100 to 767 m, with temperature conditions between 20 °C and 30 °C and an annual precipitation of 1600–2500 mm [12,13,14]. The species favors well-drained, sloping terrains. In its natural habitat, this climber attaches to phorophytes via adventitious roots to reach the upper canopy [15]; flowering subsequently occurs, primarily during the dry season [12].

2.1. Pollination of Vanilla planifolia

Flowering depends on various factors: the cutting size and stage, the edaphoclimatic conditions, plant vigor, and the phytosanitary status [12]. In nature, fruit production in V. planifolia occurs through flower fertilization by insect pollinators. However, populations of these pollinators have been drastically reduced or may have even become extinct, likely due to excessive pesticide use [12,16,17]. Although the Melipona bee was suggested as a natural pollinator [4,8,10], this idea has been dismissed, due to its small size compared to the flower. Other researchers have documented vanilla flower pollination by Euglossini [9,18,19]. In Mexico, occasional pollination by species of the genera Eulaema and Euglossa has been recorded, although at low rates, resulting in scarce seed germination under natural conditions [18,19,20].

The limited number of natural pollinators has resulted in the dependence on the manual pollination of flowers for pod production. This technique—involving self- or cross-pollination—requires manually transferring the pollinium to the stigma by bypassing the rostellum [19]. It is a meticulous, labor-intensive, and costly procedure that must be executed early in the morning by skilled labor [20]. Post-fertilization, pods require 6 to 9 months to reach harvest maturity [9,12,21,22].

2.2. Vanilla planifolia Cultivation Systems

In tropical countries such as Mexico, three types of systems are used to cultivate V. planifolia: (A) Traditional systems, in which plants are established within secondary or evergreen forests, with original vegetation species preserved or intercropped with support trees such as Citrus sinensis (orange), Eugenia capulin (capulín), and Erythrina americana (pichoco), among others [17,23]. (B) Semi-intensive systems, which retain the structure of the traditional approach while incorporating elements such as shade mesh to provide varying degrees of coverage and irrigation control (Figure 2A–C). Orange trees are utilized as support due to their high yield potential and minimal management requirements [24]. (C) Technified systems, which are characterized by regulated light, temperature, and humidity conditions, where the natural shade essential for vanilla growth is simulated using a shade mesh that modulates the light levels between 50% and 80% (Figure 2B), and deciduous support trees such as Erythrina species and Gliricidia sepium are employed [19,25].

Figure 2.

Principal Vanilla planifolia cultivation systems utilized in Mexico. (A) Traditional system: plants are established within secondary or evergreen forests, utilizing original vegetation or intercropped support trees such as Citrus sinensis, Eugenia capulin, and Erythrina americana. (B) Semi-intensive system: this approach maintains the traditional forest structure while incorporating technical elements such as shade mesh for coverage and irrigation control. (C) Technified system: this is characterized by highly regulated light, temperature, and humidity conditions, using shade mesh to modulate the light levels between 50% and 80%, along with deciduous tutors. Photos courtesy of David Moreno.

In all three systems, vanilla propagation occurs through stem cuttings taken from healthy, pathogen-free mother plants with high pod-production potential [7]. The cuttings are usually 80 to 100 cm in length and contain six to eight nodes. They are disinfected by immersion in a fungicidal solution for 2 to 5 min. Subsequently, the cuttings are stored in a shaded and well-ventilated area for a period ranging from 7 to 15 days to facilitate slight dehydration. This process ensures the acquisition of a flexible planting material and mitigates the risk of stem rot [12,21].

Planting takes place when the support trees (tutors) attain an optimal size to sustain the vanilla plants, which subsequently reach maturity and flowering between three and four years after planting [26].

2.3. Curing and Processing of Vanilla Pods

Glucovanillin functions as the precursor to vanillin and is found in immature pods. During the curing process, enzymatic reactions promote the synthesis of aromatic compounds such as ρ-hydroxybenzoic acid, ρ-hydroxybenzaldehyde, and vanillic acid, which contribute to the organoleptic properties observed in mature fruits [15,27]. Natural vanilla extract contains over 248 aromatic and volatile compounds, including vanillin, anisic acid, anisaldehyde, salicylic alcohol, phenolic ethers, phenols, eugenol, and carbonyl compounds [11]. These substances are recognized for their antimicrobial and anticancer activities [21]. The curing or processing entails exposing the pods to sunlight for continuous drying over approximately three months or employing industrial systems equipped with ovens [3,11,15].

Both methods encompass dehydration and fermentation phases and comprise the following stages [7,19,21,22] (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Curing and processing stages of Vanilla planifolia pods. (A) Harvesting and de-peeling: categorization and detachment from the floral peduncle based on maturity. (B) Killing: thermal treatment (63–65 °C) or sun exposure to halt growth and trigger enzymatic activity. (C) Drying and conditioning: sunlight dehydration (~90 days) to 25% moisture content, followed by storage (≥1 month) to refine the aroma. (D) Sorting and grading: final classification by length and quality for international packing. Photos: (A–C) courtesy of David Moreno; (D) courtesy of Alejandro Domínguez.

- Harvesting and de-peeling: pods are categorized based on their size and maturity level; then, the pod is detached from the floral peduncle.

- Killing: to inhibit the growth of the vanilla pod and initiate enzymatic activity, the pods are heated at 63–65 °C for three min or subjected to sunlight, depending on the traditional practices and environmental conditions.

- Sweating: pods are positioned on polyester tarps or bases, covered with dry leaves or polyester, to increase the temperature to 45 °C; the pods begin sweating, developing a chocolate brown coloration, which persists until they achieve 60–70% moisture content.

- Drying: pods are exposed to direct sunlight on tarps for approximately 90 days, allowing for a gradual reduction in the moisture content to approximately 25%.

- Conditioning: pods exhibiting a high-quality aroma that are free from pests or fungi are carefully selected for storage for a minimum duration of one month.

- Sorting and grading: the pods are categorized based on their length, appearance, aroma, and moisture content and are packed in accordance with international standards.

2.4. Importance and Production of Vanilla planifolia

Globally, vanillin is employed in the food (60%), perfume (33%), and pharmaceutical (7%) industries [27]. According to the FAOSTAT statistical database, between 2018 and 2021, the regions with the highest production of crude vanilla were Africa (Madagascar and Reunion Island) with 48%, Asia (Indonesia and India) with 33.7%, Oceania (Tahiti) with 10.2%, and the Americas (Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Costa Rica) with 8% of total production [10].

Between 1998 and 2020, crude vanilla production in Mexico fluctuated. In 1990, the production was 564 tons across 2280 hectares, in 2000, it increased to 637 tons over 1103 hectares, and in 2020, it was 609 tons over 1046 hectares. The primary producing states are Veracruz (645 tons), followed by Puebla (74 tons), Oaxaca (61 tons), and San Luis Potosi (8 tons), collectively representing 24% of the country’s total production [7,19,22,27].

Mexico has a reduced share of global vanilla production due to a combination of problems, ranging from plant propagation, development, and production to pod processing, phytosanitary issues at each stage, market price fluctuations, and the introduction of synthetic vanilla [7,16,17,28,29]. To address the deficit of commercial propagules, farmers have used asexual reproduction (cuttings), because sexual reproduction from seeds in natural conditions takes years and has a low germination percentage. In contrast, the growth of cuttings takes between 6 and 12 months [6]. Although this is a shorter time for replacing new plants, it does not guarantee the health of the plantations [27].

The heavy dependence on asexual reproduction strategies and global cloning initiatives has significantly diminished the genetic diversity of cultivated vanilla, thereby considerably impairing its capacity to adapt to abiotic stressors and increasing its vulnerability to a wide array of biotic pressures [6,30]. This genetic bottleneck has engendered notable phytosanitary challenges, including viral infections such as Cymbidium mosaic virus, potyvirus, and cucumber mosaic virus, which induce leaf deformation; bacterial soft rot caused by Dickeya dadantii; and various fungal diseases such as anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.) and rust (Uromyces joffrini and Puccinia sinanoema). Additionally, different forms of rot and dieback are associated with Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Sclerotium spp., Phytophthora spp., Fusarium proliferatum, and F. solani. Despite this broad spectrum of threats, the most destructive pathogen globally, particularly within Mexican plantations, remains Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae. This pathogen is the primary causative agent of vanilla wilt and continues to be the predominant factor contributing to substantial yield reductions and the decline of plantations [31].

Given the factors affecting vanilla cultivation, alternative methods have been explored to conserve and mass-produce high-quality vanilla plants to meet the increasing demand for this product. Plant tissue culture, also known as in vitro culture, is a highly effective biotechnological technique for the large-scale propagation of V. planifolia. It provides a rapid method for multiplying pathogen-free plants and has proven valuable for germplasm preservation, genetic improvement, and metabolite biosynthesis [32,33].

3. In Vitro Culture as a Tool for the Production and Conservation of Vanilla planifolia

In vitro culture encompasses techniques for isolating or selecting plant organs, tissues, or cells under aseptic conditions and cultivating them in synthetic media containing essential nutrients for tissue growth and development [19,32,33,34]. This technique is based on the “totipotency” hypothesis, proposed by Gottlieb Haberlandt in 1902, which states that every cell possesses the genetic potential to produce exact replicas of the plant species of interest [33]. Regeneration is achieved through cell division and differentiation to form new organs, a process obtained via incubation under controlled conditions of temperature, light, and humidity [27,33,34].

The main in vitro regeneration pathways are (1) somatic embryogenesis (SE), the formation of bipolar embryos (root and shoot) from somatic cells without gamete fusion and vascular connection to the donor tissue [32], and (2) organogenesis, the formation of unipolar primordia from a section of plant tissue, leading to the development of new shoots.

Both processes can be direct (somatic embryos developing directly from cells) or indirect (through the formation of a mass of undifferentiated cells called callus) [32,34,35]. In orchids, the morphogenetic response often begins with the formation of spherical structures called PLBs (protocorm-like bodies), which then organize to form shoots [36].

3.1. Micropropagation

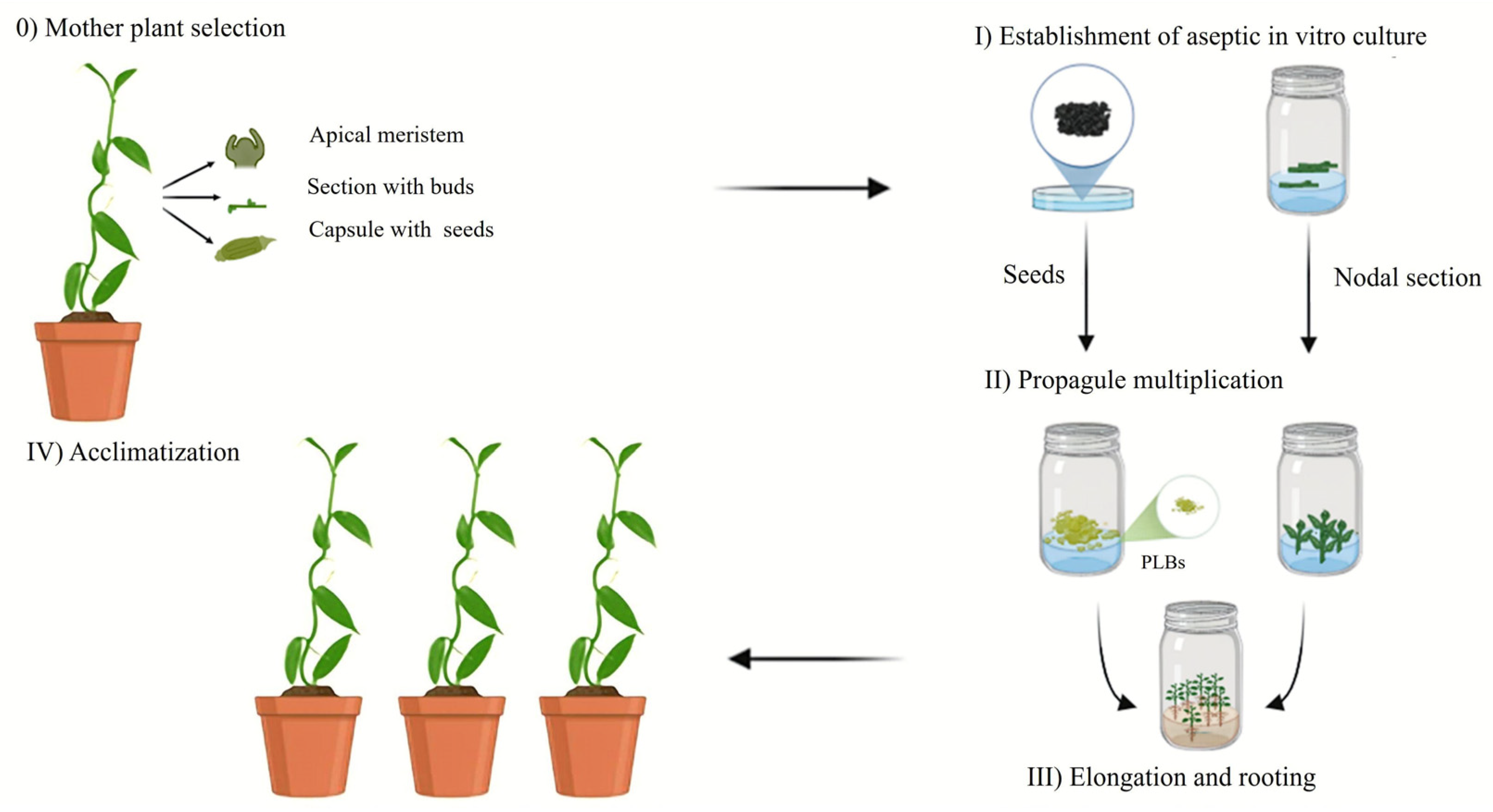

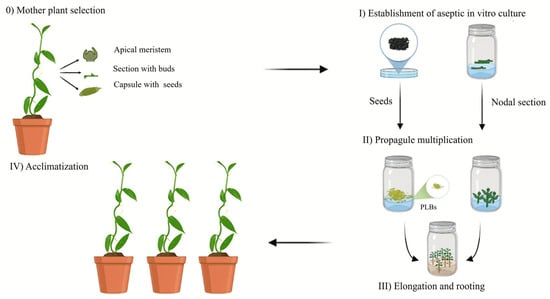

Micropropagation is a set of in vitro techniques for the mass production of plants from an explant (whole plant, organ, tissue fragment, or cell) derived from a mother plant [34,37]. Its advantage is the rapid production of plants under controlled laboratory conditions (Figure 4). Its stages are as follows.

Figure 4.

Micropropagation stages of Vanilla planifolia. (Stage 0): selection and preparation of the donor mother plant to ensure the health and genetic quality. (Stage I): surface sterilization and aseptic establishment of the explant in a nutrient medium. (Stage II): mass multiplication of propagules through shoot proliferation or protocorm-like bodies (PLBs), typically mediated by cytokinins. (Stage III): shoot elongation and adventitious root induction to produce self-sufficient plantlets. (Stage IV): multi-step acclimatization process for transitioning plantlets from in vitro conditions to ex vitro greenhouse or field environments. Illustration elaborated by Gabriela García-Vázquez.

(Stage 0) Mother plant selection. This stage focuses on selecting and preparing a mother or donor plant in a vigorous, preferably juvenile, physiological state, as young tissue has a higher growth response than mature tissue and is free of diseases [37,38,39]. The plants may originate from natural habitats or greenhouses, and foliar disinfection treatments are performed using commercial bactericides and fungicides to remove external contaminants before in vitro establishment [39]. The selection of V. planifolia mother plants is determined by the phenotypic characteristics of the donor plant [40,41,42,43,44]. The most used explants for the in vitro culture of V. planifolia are nodal segments, although apices, leaves, stem sections with axillary buds, and seeds can also be selected (Table 1) [45,46,47,48,49,50].

(Stage I) Establishment of aseptic in vitro cultures. This stage involves the disinfection protocols for the explants to be cultured, aiming to eliminate the contaminants and exogenous and endogenous microorganisms. The disinfectant solutions include ethanol, sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), mercuric chloride (HgCl2), surfactants (Tween 20 and 80), fungicides, and bactericides [38,39]. The concentrations and exposure times vary depending on the type of tissue or explant. The disinfected explants are cultured in basal media supplemented with plant growth regulators (PGRs). The most common media at this stage are Woody Plant Medium (WPM), B5 Gamborg (B5), and Murashige & Skoog (MS) [47,48,50].

To establish V. planifolia nodal sections, disinfection protocols include a washing series starting with water and commercial soap, followed by surface disinfection with 70% ethanol, HgCl2 solutions at concentrations of 0.1%, 0.2%, and 1.3% with varying exposure times, and final rinses with sterile water [40,41,45,51,52,53]. Commercial chlorine at 20% and active chlorine at 6% have also been used [47,54,55,56,57]. However, although some studies report the shoot proliferation, they do not mention the success rate of explant disinfection, which is a crucial step.

(Stage II) Propagule multiplication. For the multiplication of V. planifolia shoots, various media, including Terrestrial Orchid medium, Knudson C (KC), and Murashige & Skoog (MS), have been evaluated [46,58,59]. The MS medium is the most used because of the high content of nitrogen salts in its basal composition and the addition of organic supplements such as coconut water to promote shoot growth in semisolid or liquid culture systems (Table 1). It is necessary to culture explants in media supplemented with different PGRs, mainly auxins and cytokinins, either alone or combined. PGRs are chemically synthesized compounds that fulfill the function of phytohormones, regulating growth and development. Their addition to the culture medium results in morphogenetic responses, such as shoot proliferation, that maximize plant production under in vitro conditions [34]. The application and concentration of PGRs influence the in vitro regeneration response and the genetic variability generated during the culture stages [60]. The cytokinin 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) is primarily used for shoot proliferation. Other cytokinins that have been tested include Kinetin (Kn), meta-topolin (mT), and Thidiazuron (TDZ), combined with auxins such as indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), and coconut water (CW), among others (Table 1).

Table 1.

Influence of explant type and plant growth regulator (PGR) combinations on the in vitro shoot proliferation of Vanilla planifolia Andrews.

Table 1.

Influence of explant type and plant growth regulator (PGR) combinations on the in vitro shoot proliferation of Vanilla planifolia Andrews.

| Explant | Culture Medium | PGRs | Concentration µM | Proliferation Rate (Shoots/Explant) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodal section (2 cm) | Semisolid MS 50% | BAP/ANA | 4.44/2.68 | 5.33 | [42] |

| Nodal section (2 cm) | Semisolid MS | BAP/Kn | 4.44/6.97 | 4.17 | [51] |

| Three sections of stem with axillary bud | Semisolid MS | BAP | 8.88 | 6.1 | [61] |

| Nodal section (1.5–2 cm) | Semisolid MS | BAP/SNP | 4.44/10 | 10.33 | [59] |

| Nodal section | Semisolid MS | BAP/IAA | 8.88/1.42 | 7.33 | [60] |

| Callus from leaf (0.2 g) | Semisolid MS | BAP/ANA | 13.32/13.43 | 14.0 | [62] |

| Nodal section (1.5 cm) | Semisolid MS | BAP/Kn | 2.22/9.3 | 3–4 | [63] |

| Axillary bud | Semisolid MS | BAP/ANA | 9.55/0.445 | 18.5 | [54] |

| Nodal section (1.5–2 cm) | Semisolid MS + CW | BAP | 4.44 | 8.42 | [55] |

| Section of stem (2 cm) | Semisolid MS | BAP/IBA | 8.88/4.92 | 2.04 | [64] |

| Sections (1.5–2 cm) with a bud | Semisolid MS | BAP | 6.65 | 3.27 | [65] |

| Nodal section (2–4 cm) | Semisolid MS | mT | 4.14 | 5.0 | [40] |

| Nodal sections (2–4 cm) | Liquid MS | mT/ANA | 2.07/1.34 | 62 | [40] |

| Twenty nodal sections (1 cm) | Semisolid MS | BAP/IBA | 4.44/2.46 | 13.5 | [23] |

| Nodal section with one bud | DP MS | BAP/CW | 4.44 | 11.6 | [66] |

| Nodal section | MS | BAP | 2.22 | 6.06 | [58] |

| Nodal section | MS | BAP | 8.88 | 6.8 | [67] |

Cytokinins: BAP: 6-Benzylaminopurine; Kn: Kinetin; mT: meta-Topolin; auxins: IBA: indole-3-butyric acid; ANA: 1-naphthaleneacetic acid; CW: coconut water 15%; SNP: sodium nitroprusside; DP: double phase.

Most studies on vanilla propagation have used conventional semisolid media, with or without plant growth regulators (PGRs), which typically include gelling agents such as gellan gum, Phytagel, or agar–agar [32,68]. Semisolid media provide advantages for transportation and export due to their small volumes and reduced space requirements [38]. However, they also have limitations for scaling up production, including the need for repeated subcultures due to nutrient depletion, a low multiplication rate, an increased risk of contamination during handling, and high production costs (40–60%), primarily due to the labor costs for manual handling and the high cost of gelling agents [69,70,71].

To overcome these limitations, liquid culture media, both basal and PGR-supplemented, have been used, providing direct contact and uniform access to essential nutrients [72,73]. Despite this, liquid systems can cause issues such as asphyxia and hyperhydration, leading to physiological disorders in the explants [74]. To prevent these problems, improvements include the use of culture supports such as cellulose paper or sponges [75] and the development of semi-automated TISs, which have been shown to increase multiplication rates, reduce hyperhydration, and lower contamination from repeated handling, compared to semisolid cultures [74,76].

TIS technologies include the Recipient of Automated Temporary Immersion RITA®, SETIS®, Temporary Immersion Bioreactors (BITs), and the SETISTM temporary immersion bioreactor system [71,72]. These bioreactors operate by intermittently contacting the explant with the culture medium for short periods and are controlled by solenoid valves. These systems regulate parameters such as the pressure, oxygen transfer, dilution of toxic components, and pH, thereby promoting shoot proliferation and growth, ensuring uniform nutrient access, and facilitating superior gas exchange. As a result, the plants obtained are more vigorous, the production costs are significantly reduced because no gelling agents are used, and the risk of contamination decreases due to less manual handling [70,71]. Although the initial investment in automation and infrastructure may be higher, the reduced manual intervention and accelerated growth cycles make TIS a more efficient biotechnological tool for the large-scale production of high-quality plantlets [70,76].

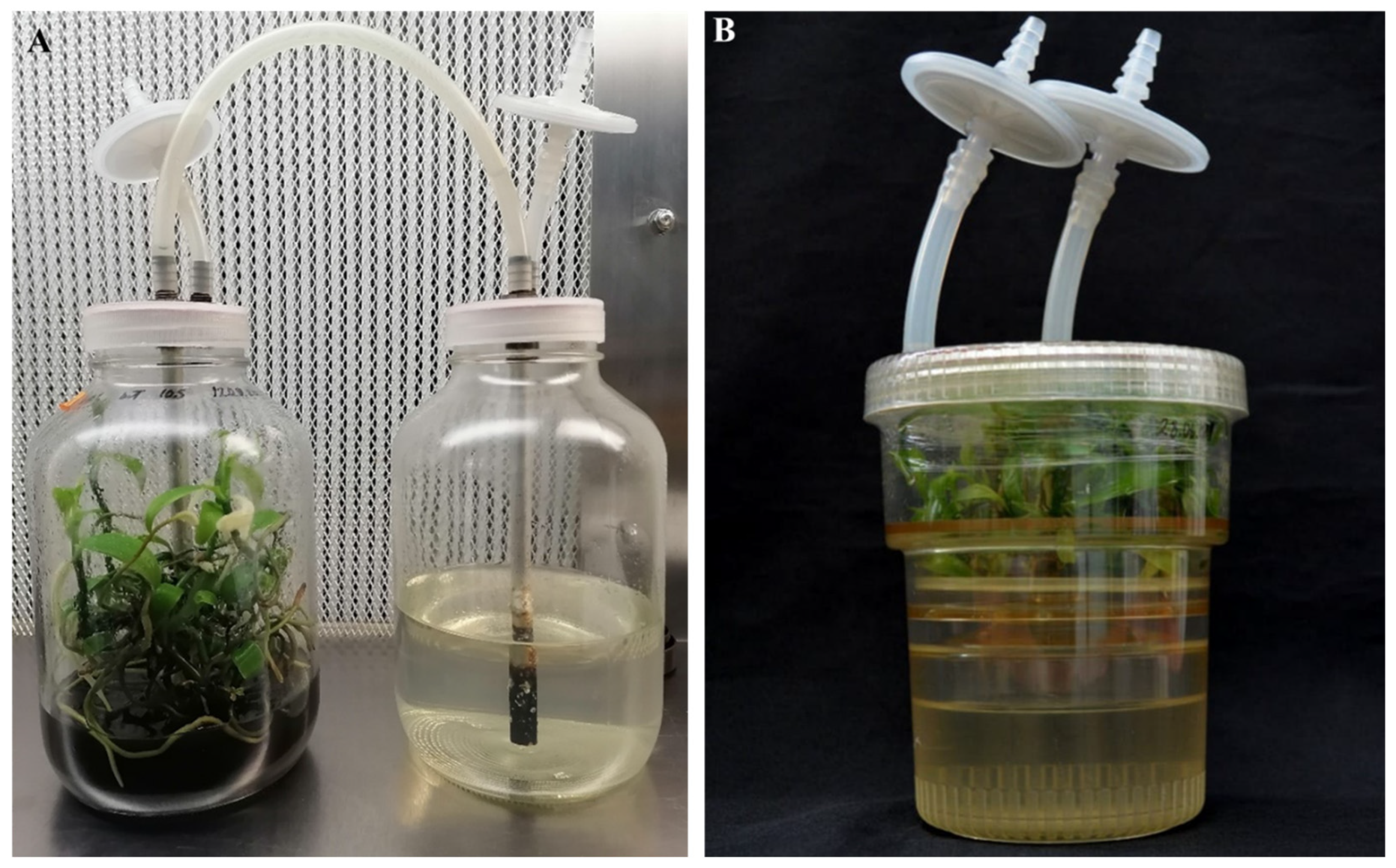

In the in vitro culture of plants, TIS mitigates tissue oxidation by diluting phenol and decreasing hyperhydration, thereby improving the nutrient absorption, due to the short exposure time to the medium. Furthermore, the gas exchange provided by these systems prevents tissue asphyxia [37,76,77]. Research comparing these systems in vanilla propagation indicates that BIT and SETIS generally produce more vigorous shoots, higher multiplication rates, and a superior morphological quality, including more height and root development, than semisolid cultures (Table 1 and Table 2). However, the morphogenetic response is design-dependent; for instance, the RITA® system yields shorter shoots compared to those developed in the BIT (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Comparative efficiency of explant types and immersion frequencies for the large-scale in vitro shoot multiplication of Vanilla planifolia using various temporary immersion systems.

Figure 5.

Temporal immersion systems used for the in vitro propagation of Vanilla planifolia at the Ecology Institute laboratory. (A) Temporary Immersion Bioreactor (TIB); (B) Recipient of Automated Temporary Immersion (RITA®). Photo: Gabriela García-Vázquez.

Although positive responses have been observed, further research is needed to establish effective protocols for inducing V. planifolia shoots. The full range of regulators should be tested at various micromolar concentrations and across different culture systems. Additionally, studies should examine the effects on the genetic stability of the propagated clones and germplasm conservation.

(Stage III) Elongation and Rooting. After the induction period, which typically lasts between 21 and 45 days, periodic subcultures are performed to promote shoot growth and root development. During this phase, the shoots are separated and cultivated in MS media without PGRs. As the nutritional requirements change, carbohydrates (sucrose) are added as the primary carbon source, and activated charcoal is included to absorb phenolic exudates [46,62,63,64]. While some orchid species form roots in basal media without PGRs, many others need auxins such as NAA (1-naphthaleneacetic acid), IAA (indoleacetic acid), or IBA (indole-3-butyric acid) at micromolar levels [38,39]. It has been reported that NAA at 4.45 and 5.37 μM promotes root formation in 88% and 93% of shoots, respectively [54,55]. Similarly, IAA and IBA at concentrations of 2.85 and 5.70 μM also support root development in vanilla explants [42,47,50,66].

(Stage IV) Acclimatization. In vitro cultured plants are produced in sterile environments with controlled growth conditions, including temperature, humidity, light intensity, gas exchange, and nutrient supply. These conditions cause the plants to rely on heterotrophic or mixotrophic nutrition, exhibit low photosynthetic efficiency, and develop non-functional stomata, leading to poor water transport [80].

For successful establishment and growth in the greenhouse, in vitro plants must gradually adapt to new conditions of light intensity, humidity, and temperature. This adjustment enables the necessary morphological and physiological changes for developing an autotrophic nutrition system [81,82]. The highest rate of plant loss occurs when in vitro plants are transferred to substrates or soil. To reduce this, acclimatization protocols are used, starting with selecting plants that have developed leaves and roots and completely removing the agar or culture medium components to prevent contamination [80,82,83,84].

To acclimatize these plants, it is also necessary to select substrates that provide the appropriate nutrients and water for the growth of the in vitro-cultivated species; therefore, solid and porous components, whether organic or synthetic, are mixed. To establish orchids in the greenhouse, substrates with adequate moisture retention, good drainage, and aeration are preferred [85]. Typical mixtures include mineral charcoal, pine bark, pumice, agrolite, compost, earthworm humus, zeolite, Sphagnum moss, coconut fiber, and gravel [83,84,85]. Different substrate mixtures have been evaluated for V. planifolia, achieving 80–100% plant survival (Table 3). Another limiting factor is the susceptibility of vanilla to pathogenic fungi [27]. Consequently, alternatives are being sought to increase plant survival, such as obtaining genotypes resistant to F. oxysporum f. sp. vanillae [86] and the addition of salicylic acid as a biostimulant for stem, leaf, and root formation [78].

3.2. Genetic Stability in Vanilla planifolia Plants

In vitro culture is essential for rapid plant production. However, the propagation process can cause genetic variations (somaclonal variation) and physiological changes. These changes are linked to factors such as recalcitrance, oxidative stress, culture age, periodic subcultures, and PGR addition, which can result in point mutations, DNA methylation, and chromosomal rearrangements in plants of the same parental line [87,88,89,90,91].

In the propagation of commercial species such as V. planifolia, it is important to maintain the genetic integrity of the mother plant. These phenotypes are selected for traits such as vigor, apparent resistance to pests and diseases, and high productivity potential [27,92].

Molecular markers based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used to verify the genetic integrity or variation of in vitro-grown plants. These markers include Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA (RAPD), Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP), Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) or Short Tandem Repeat (STR), and Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR) [5,88,89]. They enable the detection of genetic stability, diversity, interspecies hybridization, and gene sequence variations [89]. In studies of somaclonal variation in V. planifolia, ISSR markers are most commonly used, due to their high reproducibility in detecting polymorphisms and monomorphisms [91,93,94]. Some studies have confirmed the absence of genetic variation [63,93,94,95], while others have detected it [45,96,97,98].

Table 3.

Impact of various substrate compositions on the survival and ex vitro acclimatization of Vanilla planifolia plantlets under greenhouse conditions.

Table 3.

Impact of various substrate compositions on the survival and ex vitro acclimatization of Vanilla planifolia plantlets under greenhouse conditions.

| Substrate Components | Mixing Ratio | Survival Rate (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peat moss Agrolite | 1:1 | 80–100 | [43,54,67,74,75,79,86] |

| Pine bark Compost Pumice | 1:1:1 | 93.33 | [99] |

| Sand Compost | 1:2 | 80–85 | [55,59] |

| Topsoil Compost | 2:1 | 90 | [47] |

| Vermicompost Sand Manure | 1:1:1 | 85 | [48] |

| Sand Topsoil Charcoal Coconut fiber | 1:1:1:1 | 86 | [60] |

| Vermicompost Garden soil | 1:1 | 100 | [40] |

| Pumice Vermiculite Compost | 1:1:1 | 80 | [62] |

3.3. Physical Factors Involved in the Regeneration of Vanilla planifolia in In Vitro Culture

Most in vitro cultures are incubated in chambers or rooms with a controlled temperature, light, photoperiod, and humidity [37]. Among these factors, light is the most essential for photosynthesis, biochemical regulation, morphological processes, pigment formation, endogenous hormone regulation, morphogenesis, and gene expression related to rooting. These processes are affected by the quality, quantity, and duration of the photoperiod provided in the culture systems [32,100,101,102].

Currently, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are used because they provide a higher flux of photons suitable for photosynthesis, specific spectral ranges, minimal heat emission, and low electrical consumption, which helps reduce costs [34,103]. Plants absorb light within the spectral range of 400 to 700 nanometers (nm), known as photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). Wavelengths of red light (660 nm), blue light (460 nm), and white light (420 nm) have been shown to induce a higher photosynthetic rate in various plant species [104], either with a single light spectrum or in combinations of two or more, under photoperiods of 16 h of light [102,104].

In the Orchidaceae family, LED systems have been utilized to optimize callus induction, the development of protocorm-like bodies (PLBs), and axillary shoot proliferation. In genera such as Dendrobium, Cattleya, Cymbidium, and Oncidium, the synergistic effect of red and blue light is often superior to monochromatic or fluorescent lighting for promoting vegetative growth [102,105]. Specifically, for Vanilla planifolia, the interaction between the spectral quality and the photoperiod is a decisive factor for the multiplication efficiency. Current research indicates that a combination of red and blue light under a 12 h photoperiod yields a maximum proliferation rate of 16.08 ± 0.72 shoots per explant [106]. Interestingly, increasing the photoperiod to 16 h under the same spectral conditions resulted in lower proliferation rates ranging from 5.80 ± 0.48 to 10.8 ± 0.59 shoots per explant, suggesting that an excessive light duration may lead to physiological saturation or inhibitory effects in this species [107,108].

The evolutionary progression of LED technology has enabled its emergence as a crucial instrument for optimizing plant growth within controlled environments. This technology provides an advanced method for enhancing productivity in commercial settings, particularly through the precise regulation of the light environment. It is well recognized that light conditions, specifically irradiance and spectral quality, significantly influence in vitro morphogenetic responses in cultured cells and tissues. Nevertheless, a notable limitation persists within current biotechnological protocols: the specific spectral quality and irradiances employed are often under-reported or inadequately defined.

Despite the worldwide increase in research on LED-mediated lighting modifications, studies that focus exclusively on the Orchidaceae family and the genus Vanilla in particular remain notably limited. Although the existing literature confirmed differential physiological and morphological effects resulting from various light spectra, the systemic failure of researchers to specify the precise spectral qualities constitutes a fundamental obstacle to the reproducibility of protocols. This lack of standardization severely hampers the ability to rigorously compare data across different studies.

Moreover, most studies focus on short-term in vitro results, typically ranging from 4 to 12 weeks. Consequently, there is a substantial knowledge gap regarding the long-term effects of spectral quality. There is an urgent need for long-duration studies to ascertain how early-stage light treatments influence subsequent acclimatization processes and the ultimate agricultural productivity of mature plants. Addressing these deficiencies is vital for the development of standardized high-efficiency propagation systems for economically significant species such as Vanilla planifolia.

4. Vanilla planifolia and Orchid Mycorrhizal Fungi

Orchids establish essential symbiotic relationships with orchid mycorrhizal fungi (OMF) through associations established between the host roots and the fungal mycelium [109]. This interaction is pivotal during the protocorm stage, where the fungus supplies organic carbon and essential nutrients, which are necessary for germination [110]. During the juvenile and mature stages, OMF augment the host’s photosynthetic capacity by facilitating the assimilation of nutrients with limited soil mobility, such as phosphorus and nitrogen [111,112].

Structurally, OMF mycelia develop as endophytes within cortical cells, forming specialized spiraling structures known as pelotons [113,114,115,116]. Orchids regulate this colonization through enzymatic activity, including peroxidases, ascorbic acid, and polyphenol oxidase, which facilitates the degradation of pelotons and the activation of phytoalexins, thereby promoting nutrient exchange [114]. In this reciprocal relationship, the fungus receives carbon compounds derived from the photosynthesis of the plant [110,112].

The fungal genera most frequently associated with orchids include Sebacina, Ceratobasidium, Tulasnella, and Rhizoctonia (Basidiomycetes) [117]. Species such as Rhizoctonia solanii and R. repens are particularly prominent [118]. These filamentous fungi are characterized by their tendency to grow primarily as mycelium in vitro, rarely producing asexual spores [110,118]. Symbiotic seed culture techniques have utilized endophytic fungi such as Ceratobasidium sp., Thanatephorus cucumeris, and Tulasnella calospora to significantly enhance in vitro germination rates, as these fungi degrade complex polymers in the culture medium to supply the embryo directly [119,120,121,122,123].

In V. planifolia, associations with Tulasnella and Ceratobasidium have been documented in strains isolated from the roots of mature plants in both wild and agroforestry systems [115,118,124,125]. Specifically, Ceratobasidium isolates have proven effective in improving seed germination, in vitro growth, and the survival of plantlets during acclimatization [126,127]. Beyond growth promotion, these endophytic fungi influence the V. planifolia metabolome, affecting the biochemical composition of the pods and vanillin biosynthesis during the curing process [124].

OMF promote growth by secreting phytohormones—including auxins, cytokinins, gibberellic acid, abscisic acid, and ethylene—and by inducing the production of secondary metabolites in response to biotic and abiotic stress [128]. Molecular studies have elucidated these interactions through genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses, identifying genes involved in the transport of nitrogen, phosphate, ammonium, oligopeptides, and amino acids [129,130,131,132]. Furthermore, OMF modulate the signaling pathways of phytohormones and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [133].

Under greenhouse conditions, symbiosis facilitates acclimatization and enhances growth, a phenomenon linked to the upregulation of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis [134].

Notwithstanding the progress made in orchid–fungal research [116], a notable gap remains regarding the specific fungal genes and metabolic pathways exclusive to vanilla species. Investigations conducted at the Clavijero Botanical Garden of INECOL have demonstrated that the in vitro inoculation of V. planifolia plantlets with mycorrhizal isolates from wild individuals significantly enhances the seedling growth. Furthermore, greenhouse assessments confirm a positive impact on the physiological development and acclimatization, highlighting the substantial biotechnological potential of these associations to optimize the commercial production of V. planifolia.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Vanilla micropropagation is now a crucial biotechnological method for the large-scale distribution of planting material and for improving crop health. Unlike traditional methods, such as the use of cuttings, which can spread pests and genetic problems, in vitro cultivation produces virus-, bacterium-, and fungus-free seedlings, including those infected with pathogenic fungi such as Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae. This technique allows for the safe exchange of germplasm regionally and internationally under strict phytosanitary standards, ensuring vigorous and uniform propagules. It also contributes to preventing pest spread by providing a sterile environment and serves as a strategic alternative to reduce economic losses and promote sustainable production, even as biotic pressures increase. Although advances have been made in vanilla in vitro propagation—demonstrated by the success of the MS medium, BAP, auxin combinations, and increased TIS productivity—the protocols still need refinement. Research at the Plant Tissue Culture Laboratory in collaboration with the Clavijero Botanical Garden aims to develop reliable protocols for the mass propagation and germplasm conservation of V. planifolia to support sustainability and the livelihoods of local farmers.

Future efforts should focus on optimizing PGRs and their concentrations across different systems and assessing the impacts on genetic stability and conservation. It is also essential to incorporate orchid mycorrhizal fungi, which can enhance germination, survival, and plant health. Additionally, addressing climate change through genetic improvements that improve resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses is vital to developing versatile, disease-resistant vanilla lines suitable for diverse climates. This biology-based approach offers a comprehensive solution for increasing productivity and resilience in commercial vanilla farming. Successful implementation of these biotechnologies will help meet global vanilla demand, promote sustainability, and improve farmers’ livelihoods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.-V. and M.M.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.-V. and M.M.-R.; writing—review and editing, G.G.-V., M.M.-R., G.C. and A.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Moreno and Alejandro Domínguez for providing the photographs used in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reyes-López, D. Acclimatization of Intraspecific Hybrids of Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews, Obtained In Vitro. Agro Product. 2016, 9, 72–77. Available online: https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/848 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Banerjee, G.; Chattopadhyay, P. Vanillin Biotechnology: The Perspectives and Future. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisoni, M.; Nany, F. The Beautiful Hills: Half a Century of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews) Breeding in Madagascar. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, M.; Solís-Montero, L.; Alavez, V.; Rodríguez-Juárez, P.; Gutiérrez-Alejo, M.; Wegier, A. Vanilla cribbiana Soto Arenas Vanilla Hartii Rolfe Vanilla Helleri, A.D. Hawkes Vanilla inodora Schiede Vanilla insignis Ames Vanilla Odorata C. Presl Vanilla phaeantha Rchb. f. Vanilla planifolia Jacks Ex. Andrews Vanilla pompona Schiede Orchidaceae. In Ethnobotany of the Mountain Regions of Mexico; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1547–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bory, S.; Lubinsky, P.; Risterucci, A.-M.; Noyer, J.-L.; Grisoni, M.; Duval, M.-F.; Besse, P. Patterns of Introduction and Diversification of Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae) in Reunion Island (Indian Ocean). Am. J. Bot. 2008, 95, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubinsky, P.; Bory, S.; Hernández Hernández, J.; Kim, S.-C.; Gómez-Pompa, A. Origins and Dispersal of Cultivated Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. [Orchidaceae]). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Barrientos, A.; Perea-Flores, M.d.J.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, H.; Patrón-Soberano, O.A.; González-Jiménez, F.E.; Vega-Cuellar, M.Á.; Dávila-Ortiz, G. Physicochemical, Microbiological, and Structural Relationship of Vanilla Beans (Vanilla planifolia, Andrews) during Traditional Curing Process and Use of Its Waste. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2023, 32, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Morales, M.; Herrera-Cabrera, B.E.; Delgado-Alvarado, A. Intraspecific Variation of Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae) in the Huasteca Region, San Luis Potosí, Mexico: Morphometry of Floral Labellum. Plant Syst. Evol. 2021, 307, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinsky, P.; Van Dam, M.; Van Dam, A. Pollination of Vanilla and Evolution in Orchidaceae. Lindleyana 2006, 75, 926–929. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Viramontes, S.; Hernández-Apolinar, M.; Fernández-Concha, G.C.; Dorantes-Euán, A.; Dzib, G.R.; Castillo, J.M. Wild Vanilla planifolia and Its Relatives in the Mexican Yucatan Peninsula: Systematic Analyses with ISSR and ITS. Bot. Sci. 2017, 95, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, R.T.; Da Silva Oliveira, J.P.; Macedo, A.F. Vanilla beyond Vanilla planifolia and Vanilla × Tahitensis: Taxonomy and Historical Notes, Reproductive Biology, and Metabolites. Plants 2022, 11, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ruiz, J.; Herrera-Cabrera, B.E.; Delgado-Alvarado, A.; Salazar-Rojas, V.M.; Bustamante-Gonzalez, Á.; Campos-Contreras, J.E.; Ramírez-Juarez, J. Potential Distribution and Geographic Characteristics of Wild Populations of Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae) Oaxaca, Mexico. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2016, 64, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellestad, P.; Forest, F.; Serpe, M.; Novak, S.J.; Buerki, S. Harnessing Large-Scale Biodiversity Data to Infer the Current Distribution of Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 196, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyyappurath, S.; Atuahiva, T.; Le Guen, R.; Batina, H.; Le Squin, S.; Gautheron, N.; Edel Hermann, V.; Peribe, J.; Jahiel, M.; Steinberg, C.; et al. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-vanillae Is the Causal Agent of Root and Stem Rot of Vanilla. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, K.; Shyamala, B.N.; Naidu, M.M. Vanilla—Its Science of Cultivation, Curing, Chemistry, and Nutraceutical Properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 1250–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbolla Pérez, V.; Iglesias Andreu, L.G.; Escalante Manzano, E.A.; Martínez Castillo, J.; Ortiz García, M.M.; Octavio Aguilar, P. Molecular and Microclimatic Characterization of Two Plantations of Vanilla planifolia (Jacks Ex Andrews) with Divergent Backgrounds of Premature Fruit Abortion. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 212, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Deméneghi, M.V.; Aguilar-Rivera, N.; Gheno-Heredia, Y.A.; Armas-Silva, A.A. Vanilla Cultivation in Mexico: Typology, Characteristics, Production, Agroindustrial Prospective and Biotechnological Innovations as a Sustainability Strategy. Sci. Agropecuria 2023, 14, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, R.W.; Wheeler, G.S.; Madeira, P.T. Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Pollination of Vanilla planifolia in Florida and Their Potential in Commercial Production. Fla. Entomol. 2023, 106, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.H. Vanilla (Vanilla spp.) Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Industrial and Food Crops; Al-Khayri, J.M., Jain, S.M., Johnson, D.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 707–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Euán, J.J.G.; Guerrero-Herrera, R.O.; González-Ramírez, R.M.; MacFarlane, D.W. Frequency and Behavior of Melipona Stingless Bees and Orchid Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Relation to Floral Characteristics of Vanilla in the Yucatán Region of Mexico. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, T.; Majeed, H.; Waheed, M.; Zahra, S.S.; Niaz, M.; AL-Huqail, A.A. Vanilla. In Essentials of Medicinal and Aromatic Crops; Zia-Ul-Haq, M., Abdulkreem AL-Huqail, A., Riaz, M., Farooq Gohar, U., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 341–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, J. Vanilla Diseases. In Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology; Havkin-Frenkel, D., Belanger, F.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada-Molina, P.C.; Pérez-Silva, A.; Cerdán-Cabrera, C.R.; Soto-Enrique, A. Climatic and Microclimatic Conditions in Vanilla Production Systems (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews) in Mexico. Agron. Mesoam. 2022, 33, 48682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran, M.; Suseela Bhai, R.; Menchaca Garcia, R.; Aarthi, S.; Devasahayam, S.; Nirmal Babu, K.; Sudarshan, M.R. Vanilla. In Handbook of Spices in India: 75 Years of Research and Development; Ravindran, P.N., Sivaraman, K., Devasahayam, S., Babu, K.N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 2591–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Rodriguez, A.I.; Herrera-Cabrera, B.E.; Jaramillo-Villanueva, J.L.; Escobedo-Garrido, J.S.; Bustamante-González, A. Characterization of vanilla production systems (Vanilla planifolia A.) under orange tree and mesh shade in the Totonacapan region. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2009, 10, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- González Reyes, H.; Rodríguez Guzmán, M.D.P.; Yáñez Morales, M.D.J.; Escalante Estrada, J.A.S. Temporal Dynamics of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) Wilting Associated With Fusarium spp. in Three Production Systems in Papantla, Mexico. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2020, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantait, S.; Kundu, S. In Vitro Biotechnological Approaches on Vanilla planifolia Andrews: Advancements and Opportunities. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Posadas, M.; Zavaleta-Mancera, H.A.; Delgado-Alvarado, A.; Salazar-Rojas, V.M.; Herrera Cabrera, B.E. Morphological Identification and Characterization of the Formation of Floral Primordium in Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae). Agro Product. 2024, 17, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis-Rojas, S.; Ramírez-Valverde, B.; Díaz-Bautista, M.; Pizano-Calderón, J.; Rodríguez-López, C. Vanilla Production (Vanilla planifolia) in Mexico: Analysis and Prognosticate. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2020, 11, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watteyn, C.; Reubens, B.; Bolaños, J.B.A.; Campos, F.S.; Silva, A.P.; Karremans, A.P.; Muys, B. Cultivation Potential of Vanilla Crop Wild Relatives in Two Contrasting Land Use Systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 149, 126890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Miranda, J.J.; Martínez-Soto, D.; Ceballos-Maldonado, J.G.; Castillo-Pérez, L.J.; Rodriguez-Vargas, R.; Carranza-Álvarez, C. Organic Vanilla Production in Mexico: Current Status, Challenges, and Perspectives. Plants 2025, 14, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, G.C.; Garda, M. Plant Tissue Culture Media and Practices: An Overview. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2019, 55, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidabadi, S.S.; Jain, S.M. Cellular, Molecular, and Physiological Aspects of In Vitro Plant Regeneration. Plants 2020, 9, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, V.; Pellegrino, A.; Muleo, R.; Forgione, I. Light and Plant Growth Regulators on In Vitro Proliferation. Plants 2022, 11, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, H.; Meena, M.; Barupal, T.; Sharma, K. Plant Tissue Culture as a Perpetual Source for Production of Industrially Important Bioactive Compounds. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 26, e00450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongdam, P.; Beleski, D.G.; Tikendra, L.; Dey, A.; Varte, V.; El Merzougui, S.; Pereira, V.M.; Barros, P.R.; Vendrame, W.A. Orchid Micropropagation Using Conventional Semi-Solid and Temporary Immersion Systems: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhojwani, S.S.; Dantu, P.K. Culture Media. In Plant Tissue Culture: An Introductory Text; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgen, M.P.; Van Houtven, W.; Eeckhaut, T. Plant Tissue Culture Techniques for Breeding. In Ornamental Crops; Van Huylenbroeck, J., Ed.; Handbook of Plant Breeding; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11, pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.F.; Hall, M.A.; Klerk, G.-J.D. Micropropagation: Uses and Methods. In Plant Propagation by Tissue Culture; George, E.F., Hall, M.A., Klerk, G.-J.D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manokari, M.; Priyadharshini, S.; Jogam, P.; Dey, A.; Shekhawat, M.S. Meta-Topolin and Liquid Medium Mediated Enhanced Micropropagation via Ex Vitro Rooting in Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2021, 146, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Fuentes, M.K.; Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Cruz-Izquierdo, S.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Gamma Radiation (60Co) Induces Mutation during In Vitro Multiplication of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, Y.; Tefera, W.; Bantte, K. Enhanced Protocol Development for in Vitro Multiplication and Rooting of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andr.) Clone (Van.2/05). Biotechnol. J. Int. 2017, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Bello-Bello, J.J. SETISTM Bioreactor Increases in Vitro Multiplication and Shoot Length in Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2021, 43, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoso-Castillo, J.L.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Pérez-Sato, J.A.; Morales-Ramos, V.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Antimicrobial and Hormetic Effects of Silver Nanoparticles on in Vitro Regeneration of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews) Using a Temporary Immersion System. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017, 129, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoo, D.; Jayakumar, V.N.; Veena, S.S.; Vimala, J.; Basha, A.; Saji, K.V.; Nirmal Babu, K.; Peter, K.V. Genetic Variations and Interrelationships in Vanilla planifolia and Few Related Species as Expressed by RAPD Polymorphism. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008, 55, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchaca, R.A.; Ramos, J.M.; Moreno, D.; Luna, M.; Mata, M.; Vázquez, L.M.; Lozano, M.A. In vitro germination of hybrids of Vanilla planifolia and Vanilla pompona. Rev. Colomb. De Biotecnol. 2011, 13, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zuraida, A.R.; Fatin Liyana Izzati, K.H.; Nazreena, O.A.; Wan Zaliha, W.S.; Che Radziah, C.M.Z.; Zamri, Z.; Sreeramanan, S. A Simple and Efficient Protocol for the Mass Propagation of Vanilla planifolia. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, C.; Vatsala, T.M.; Ponmurugan, P. In vitro Multiple Shoot Proliferation and Plant Regeneration of Vanilla planifolia Andr.—A Commercial Spicy Orchid. J. Plant Biotechnol. 2006, 8, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Leal, C.A.; Puente-Garza, C.A.; García-Lara, S. In Vitro Plant Tissue Culture: Means for Production of Biological Active Compounds. Planta 2018, 248, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, E.; Cruz-Cruz, C.A.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L.; Bello-Bello, J.J. In Vitro Response of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews) to PEG-Induced Osmotic Stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, Z.; Mengesha, A.; Teressa, A.; Tefera, W. Efficient in Vitro Multiplication Protocol for Vanilla planifolia Using Nodal Explants in Ethiopia. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 8, 6817–6821. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, K.; Karupan, P. In Vitro Studies on Tropical Orchid, Vanilla planifolia Using Different Concentration of Growth Regulators. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 6, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Azofeifa Bolaños, J.B.; Rivera-Coto, G.; Paniagua-Vásquez, A.; Cordero-Solórzano, R.; Salas-Alvarado, E. Disinfection of Nodal Segments on the Morphogenetic Performance of Vanilla planifolia Andrews In Vitro Plants. Agron. Mesoam. 2019, 30, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Espinosa, H.E.; Murguía-González, J.; García-Rosas, B.; Córdova-Contreras, A.L.; Laguna-Cerda, A.; Mijangos-Cortés, J.O.; Barahona-Pérez, L.F.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G.; Santana-Buzzy, N. In Vitro Clonal Propagation of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia ‘Andrews’). HortScience 2008, 43, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.C.; Chin, C.F.; Alderson, P. An Improved Plant Regeneration of Vanilla planifolia Andrews. Plant Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 2011, 21, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar Mercado, S.A.; Amaya Nieto, A.Z.; Barrientos Rey, F. Evaluation of Different In Vitro Culture Media in the Development of Phalaenopsis Hybrids (Orchidaceae). Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol. 2013, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuhara, K.; Sato, H.; Abe, A.; Mii, M. In Vitro Optimization of Seed Germination and Protocorm Development in Gastrochilus japonicus (Makino) Schltr. (Orchidaceae). Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 101, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, G.F.; Nur, W.; Razak, A.b.W.A.; Rahman, Z.A.; Subramaniam, S. The Effect of Thin Cell Layer System in Vanilla planifolia in Vitro Culture. Curr. Bot. 2016, 5, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.C.; Chin, C.F.; Alderson, P. Effects of Sodium Nitroprusside on Shoot Multiplication and Regeneration of Vanilla planifolia Andrews. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2013, 49, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantait, S.; Mandal, N.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Das, P.K.; Nandy, S. Mass Multiplication of Vanilla planifolia with Pure Genetic Identity Confirmed by ISSR. Int. J. Plant Dev. Biol. 2009, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Rodríguez, M.A.; Menchaca-García, R.A.; Alanís-Méndez, J.L.; Pech-Canché, J.M. In Vitro Cultivation of Axillary Buds of Vanilla planifolia Andrews with Different Cytokinins. Rev. Científica Biológico Agropecu. Tuxpan 2015, 4, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Janarthanam, B.; Seshadri, S. Plantlet Regeneration from Leaf Derived Callus of Vanilla planifolia Andr. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2008, 44, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erawati, D.N.; Wardati, I.; Humaida, S.; Fisdiana, U. Micropropagation of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) with Modification of Cytokinins. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 411, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaños, O.F.; Zometa, J.F.C. In vitro germination of Vanilla planifolia Jacks seeds and comparison of micropropagation methods. Av. Investig. Agropecu. 2017, 21, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Inderiati, S. In vitro propagation of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia andr.) on different concentration of cytokinins. Agroplantae 2019, 12, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, S.O.D.; Sayd, R.M.; Balzon, T.A.; Scherwinski-Pereira, J.E. A New Procedure for in Vitro Propagation of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) Using a Double-Phase Culture System. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 161, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G. Indirect Organogenesis and Assessment of Somaclonal Variation in Plantlets of Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015, 123, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Escamilla, A.L.; Loaiza-Alanís, C.; López-Herrera, M. Effect of different gelling agents on the germination and in vitro development of Echinocactus platyacanthus link et Otto (Cactaceae) seedlings. Polibotanica 2016, 42, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.P. The Status of Temporary Immersion System (TIS) Technology for Plant Micropropagation. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 14025–14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, H.; Berthouly, M. Temporary Immersion Systems in Plant Micropropagation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002, 69, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V.; Schumann, A.; Pavlov, A.; Bley, T. Temporary Immersion Systems in Plant Biotechnology. Eng. Life Sci. 2014, 14, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabe, A.H.; Hajiahmad, A.; Fadavi, A.; Rafiee, S. Temporary Immersion Systems (TISs): A Comprehensive Review. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 357, 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, A.; Tarraf, W.; Lambardi, M.; Benelli, C. Temporary Immersion System for Production of Biomass and Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G. Evaluation of Different Temporary Immersion Systems (BIT®, BIG, and RITA®) in the Micropropagation of Vanilla planifolia Jacks. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2016, 52, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G.; Favián-Vega, E.; Teixeira Da Silva, J.A.; Leyva-Ovalle, O.R.; Murguía-González, J. Morphogenetic Stability of Variegated Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Plants Micropropagated in a Temporary Immersion System (TIB®). Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 2019, 30, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas Ramírez, J.; Palma Zúñiga, T. Morphogenetic characterization of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) for its propagation. Agron. Costarric. 2022, 46, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Andreu, L.G. Establishment of a bioreactor system for the micropropagation of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews). Agro Product. 2014, 7, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Macareno, L.C.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G. Stimulating Effect of Salicylic Acid in the In Vitro and In Vivo Culture of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks). Agrivita J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 44, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Castellá, A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G.; Bello-Bello, J.; Lee-Espinosa, H. Improved Propagation of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Ex Andrews) Using a Temporary Immersion System. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant. 2014, 50, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasemin, S.; Beruto, M. A Review on Flower Bulb Micropropagation: Challenges and Opportunities. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuammee, A.; Pingyot, T.; Foowan, S.; Pumikong, S.; Rujichaipimon, W.; Sornpood, S.; Panyadee, P. Effect of Substrates of Transplantation of the Rare Epiphytic Orchid Dendrobium farmeri for Conservation. Biodiversitas 2024, 25, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Da Silva, J.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Sharma, M.; Dobránszki, J.; Cardoso, J.C.; Zeng, S. Acclimatization of in Vitro-Derived Dendrobium. Hortic. Plant J. 2017, 3, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniewozik, M.; Parzymies, M.; Szot, P.; Rubinowska, K. Paphiopedilum Insigne Morphological and Physiological Features during In Vitro Rooting and Ex Vitro Acclimatization Depending on the Types of Auxin and Substrate. Plants 2021, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, L.; Nie, T.; Chen, Y.; Yin, Z. In Vitro Rapid Propagation Technology System of Dendrobium moniliforme (L.) Sw., a Threatened Orchid Species in China. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2023, 17, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello Castañeda, N.; Coy Barrera, C.A.; Perez, M.M. Systematic Review on Types of Substrates Used in Orchid Propagation Under Greenhouse Conditions. Rev. Mutis 2022, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Iglesias Andreu, L.G.; Noa Carrazana, J.C.; Armas-Silva, A.A. Biotechnological Techniques for the Production of Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Genotypes Resistant to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae. Cuad. Biodivers. 2018, 54, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Kumar, N. Application of Molecular Markers for the Assessment of Genetic Fidelity of In Vitro Raised Plants: Current Status and Future Prospects. In Molecular Marker Techniques; Kumar, N., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranghoo-Sanmukhiya, V.M. Somaclonal Variation and Methods Used for Its Detection. In Propagation and Genetic Manipulation of Plants; Siddique, I., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azofeifa-Delgado, Á. Use of Molecular Markers in Plants; Applications in Tropical Fruit Trees. Agron. Mesoam. 2006, 17, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Li, S.-G.; Fan, X.-F.; Su, Z.-H. Application of Somatic Embryogenesis in Woody Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimarsetiowati, R.; Setiadi Daryono, B.; Theresia Maria Astuti, Y.; Semiarti, E. Anatomical Studies and Evaluation of Genetic Stability in Plantlets Derived from Somatic Embryos of Arabica Coffee. HAYATI J Biosci. 2023, 30, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, J.L.M.; Villa, A.C.; Ávila, V.M.C. Sustainable Regional Development Strategy in Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) In Vitro Cultivation. Univ. Cienc. 2021, 10, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- González-Arnao, M.T.; Cruz-Cruz, C.A.; Hernández-Ramírez, F.; Alejandre-Rosas, J.A.; Hernández-Romero, A.C. Assessment of Vegetative Growth and Genetic Integrity of Vanilla planifolia Regenerants after Cryopreservation. Plants 2022, 11, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Aguilar, J.R.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G.; Martínez-Castillo, J.; Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Ortiz-García, M.M. In Vitro Conservation and Genetic Stability in Vanilla planifolia Jacks. HortScience 2021, 56, 1494–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, R.V.; Venkatachalam, L.; Bhagyalakshmi, N. Genetic Fidelity of Long-term Micropropagated Shoot Cultures of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) as Assessed by Molecular Markers. Biotechnol. J. 2007, 2, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigant, R.; Brugel, A.; De Bruyn, A.; Risterucci, A.M.; Guiot, V.; Viscardi, G.; Humeau, L.; Grisoni, M.; Besse, P. Nineteen Polymorphic Microsatellite Markers from Two African Vanilla Species: Across-Species Transferability and Diversity in a Wild Population of V. Humblotii from Mayotte. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012, 4, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.C.; Chakrabarty, D.; Jena, S.N.; Mishra, D.K.; Singh, P.K.; Sawant, S.V.; Tuli, R. The Extent of Genetic Diversity among Vanilla Species: Comparative Results for RAPD and ISSR. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 29, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leah, N.S.; Joseph, N.W.; Maurice, E.O. Diversity Assessment of Vanilla (Vanilla Species) Accessions in Selected Counties of Kenya Using Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) Markers. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoso-Castillo, J.L.; Bello-Bello, J.J. CO2-enriched Air in a Temporary Immersion System Induces Photomixotrophism During In Vitro Multiplication in Vanilla. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 155, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, F.; Bassil, E.; Crane, J.H.; Shahid, M.A.; Vincent, C.I.; Schaffer, B. Spectral Light Distribution Affects Photosynthesis, Leaf Reflective Indices, Antioxidant Activity and Growth of Vanilla planifolia. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 182, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chashmi, K.A.; Omran, V.O.G.; Ebrahimi, R.; Moradi, H.; Abdosi, V. Light Quality Affects Protocorm-Like Body (PLB) Formation, Growth and Development of In Vitro Plantlets of Phalaenopsis pulcherrima. Biol. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2022, 49, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, D.S.; Felipe, S.H.S.; Silva, T.D.; De Castro, K.M.; Mamedes-Rodrigues, T.C.; Miranda, N.A.; Ríos-Ríos, A.M.; Faria, D.V.; Fortini, E.A.; Chagas, K.; et al. Light Quality in Plant Tissue Culture: Does It Matter? In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant. 2018, 54, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta Gupta, S.; Jatothu, B. Fundamentals and Applications of Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) in in Vitro Plant Growth and Morphogenesis. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2013, 7, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Manivannan, A.; Wei, H. Light Quality-Mediated Influence of Morphogenesis in Micropropagated Horticultural Crops: A Comprehensive Overview. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 4615079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Kumar, R. Microclimatic Buffering on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: A Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 160, 113144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.M.H.; Boonkorkaew, P.; Boonchai, D.; Wongchaochant, S.; Thenahom, A.A. Light Quality Affects Shoot Multiplication of Vanilla pompana Schiede in Micropropagation. Thai J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 52, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda, M.A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.G.; Luna-Sánchez, I.J. Light Quality Affects Growth and Development of in Vitro Plantlet of Vanilla planifolia Jacks. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 109, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Bello, J.J.; Martínez-Estrada, E.; Caamal-Velázquez, J.H.; Morales-Ramos, V. Effect of LED Light Quality on in Vitro Shoot Proliferation and Growth of Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, L.W.; Corey, L.L. Orchid Mycorrhizal Fungi: Isolation and Identification Techniques. In Orchid Propagation: From Laboratories to Greenhouses—Methods and Protocols; Lee, Y.-I., Yeung, E.C.-T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearnaley, J.; Perotto, S.; Selosse, M. Structure and Development of Orchid Mycorrhizas. In Molecular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Martin, F., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, S.; Sillo, F.; Ghirardo, A.; Perotto, S.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Balestrini, R. Integration of Fungal Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Provides Insights into the Early Interaction between the ORM Fungus Tulasnella sp. and the Orchid Serapias vomeracea Seeds. IMA Fungus 2024, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Langthasa, M.; Choure, K.; Agnihotri, V.; Srivastava, A.; Rai, P.K.; Tilwari, A.; Maheshwari, D.K.; Pandey, P. Non-Rhizobial Nodule Endophytes Improve Nodulation, Change Root Exudation Pattern and Promote the Growth of Lentil, for Prospective Application in Fallow Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1152875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M. Orchid Mycorrhiza: Isolation, Culture, Characterization and Application. South Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, O.; Agrawala, D.K.; Chakraborty, A.P. Studies on Orchidoid Mycorrhizae and Mycobionts, Associated with Orchid Plants as Plant Growth Promoters and Stimulators in Seed Germination. In Microbial Symbionts and Plant Health: Trends and Applications for Changing Climate; Mathur, P., Kapoor, R., Roy, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Chávez, M.D.C.A.; Torres-Cruz, T.J.; Sánchez, S.A.; Carrillo-González, R.; Carrillo-López, L.M.; Porras-Alfaro, A. Microscopic Characterization of Orchid Mycorrhizal Fungi: Scleroderma as a Putative Novel Orchid Mycorrhizal Fungus of Vanilla in Different Crop Systems. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favre-Godal, Q.; Gourguillon, L.; Lordel-Madeleine, S.; Gindro, K.; Choisy, P. Orchids and Their Mycorrhizal Fungi: An Insufficiently Explored Relationship. Mycorrhiza 2020, 30, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, C.; Hou, M.; Xing, Y.; Chen, J. Perspective and Challenges of Mycorrhizal Symbiosis in Orchid Medicinal Plants. Chin. Herb. Med. 2024, 16, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras-Alfaro, A.; Bayman, P. Mycorrhizal Fungi of Vanilla: Diversity, Specificity and Effects on Seed Germination and Plant Growth. Mycologia 2007, 99, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchan, M.; Verma, J.; Bhatti, S.K.; Thakur, K.; Kusum; Sagar, A.; Sembi, J.K. Orchids and Mycorrhizal Endophytes: A Hand-in-Glove Relationship. In Endophyte Biology; Apple Academic Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, W.; Hou, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, X.; Xu, L. Effects and Benefits of Orchid Mycorrhizal Symbionts on Dendrobium officinale. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, L.W.; Dvorak, C.J. Tulasnella calospora (UAMH 9824) Retains Its Effectiveness at Facilitating Orchid Symbiotic Germination in Vitro after Two Decades of Subculturing. Bot. Stud. 2021, 62, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, L.; Xia, W.; Liang, L.; Bai, X.; Li, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, L. Mycorrhizal Compatibility and Germination-Promoting Activity of Tulasnella Species in Two Species of Orchid (Cymbidium mannii and Epidendrum radicans). Horticulturae 2021, 7, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Zheng, B.; Wang, T.; Cao, X. Isolation of Tulasnella Spp. from Cultivated Paphiopedilum Orchids and Screening of Germination-Enhancing Fungi. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.J.A.N.; Gónzalez-Chávez, M.D.C.A.; Carrillo-González, R.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Mueller, G.M. Vanilla Aerial and Terrestrial Roots Host Rich Communities of Orchid Mycorrhizal and Ectomycorrhizal Fungi. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Espinosa, A.T.; Bayman, P.; Otero, J.T. Ceratobasidium as a mycorrhizal fungus of orchids in Colombia. Acta Agronómica 2010, 59, 316–326. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique-Barros, S.; Flanagan, N.S.; Ramírez-Bejarano, E.; Mosquera-Espinosa, A.T. Evaluation of Tulasnella and Ceratobasidium as Biocontrol Agents of Fusarium Wilt on Vanilla planifolia. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, N.F.; Díez, M.C.; Otero, J.T. The vanilla and the fungus mycorrhizae formers. Orquideología 2012, 29, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, K.; Shah, S.; Sharma, J.; Paudel, M.R.; Pant, B. Isolation, Characterization, and Plant Growth-Promoting Activities of Endophytic Fungi from a Wild Orchid Vanda cristata. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1744294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fochi, V.; Chitarra, W.; Kohler, A.; Voyron, S.; Singan, V.R.; Lindquist, E.A.; Barry, K.W.; Girlanda, M.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Martin, F.; et al. Fungal and Plant Gene Expression in the Tulasnella calospora–Serapias vomeracea Symbiosis Provides Clues about Nitrogen Pathways in Orchid Mycorrhizas. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampejsová, R.; Berka, M.; Berková, V.; Jersáková, J.; Domkářová, J.; Von Rundstedt, F.; Frary, A.; Saiz-Fernández, I.; Brzobohatý, B.; Černý, M. Interaction With Fungi Promotes the Accumulation of Specific Defense Molecules in Orchid Tubers and May Increase the Value of Tubers for Biotechnological and Medicinal Applications: The Case Study of Interaction Between Dactylorhiza sp. and Tulasnella calospora. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 757852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Yang, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, M.; Lv, F. Deep Sequencing–Based Comparative Transcriptional Profiles of Cymbidium Hybridum Roots in Response to Mycorrhizal and Non-Mycorrhizal Beneficial Fungi. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardo, A.; Fochi, V.; Lange, B.; Witting, M.; Schnitzler, J.; Perotto, S.; Balestrini, R. Metabolomic Adjustments in the Orchid Mycorrhizal Fungus Tulasnella calospora during Symbiosis with Serapias vomeracea. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1939–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, M.; Chong, S.; Si, J.; Wu, L. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Approaches Deepen Our Knowledge of Plant–Endophyte Interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 700200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, C. Combined Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Pivotal Role of Mycorrhizal Fungi Tulasnella sp. BJ1 in the Growth and Accumulation of Secondary Metabolites in Bletilla Striata (Thunb.) Reiehb.f. Fungal Biol. 2025, 129, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]