Abstract

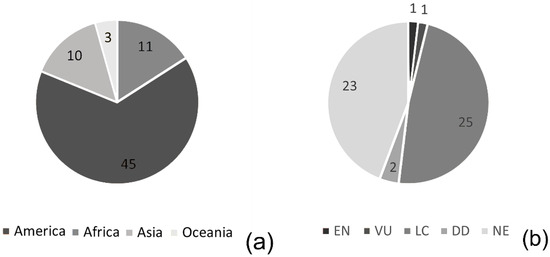

Ex situ conservation of plants is a current and urgent issue, especially in the Brazilian context. While Brazil has the world’s highest plant diversity, few consistent initiatives are aimed at conserving the potential of our living collections toward reaching Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC). Objective II of GSPC calls for the conservation of plant diversity, with Target 8 specifying 75% of threatened plant species in ex situ collections. It was only after cataloging the collection of Malvaceae from the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden (JBRJ) for scientific publication that we realized the potential of this collection for ex situ conservation. With this in mind, we carefully catalog the individuals present, updating the names of species and counting their individuals. We found that Malvaceae is represented by 63 species and 216 individuals in the arboretum, 45 species native to America, 11 from Africa, 10 from Asia, and 3 from Oceania. Using IUCN criteria, only two species are threatened and two are data-deficient, with one or two individuals each. Based on these data and the specific biology of this taxonomic group, we identified the main problems and listed recommendations to make this collection more representative of the endangered taxa of the Brazilian flora. Therefore, we expect this effort to be a solid contribution to Target 8 mandated by GSPC, as well as a replicable pilot project for other taxonomic groups of Brazilian flora.

1. Introduction

Botanical gardens make a significant contribution to the ex situ conservation of endangered plant species, playing an important role in maintaining biodiversity and raising public awareness about plant conservation in the context of medicinal and economic benefits [1,2,3]. These institutions serve not only as areas of natural beauty in urban areas but also as centers for the dissemination of botanical knowledge and environmental education through community-driven research and education programs [4,5,6]. The synergy among entities like botanical gardens, universities, and research centers has strengthened botanical science and expanded knowledge about plant diversity [7,8]. Recent studies emphasize the relevance of these institutions in identifying new plant species and investigating medicinal, food, and industrial uses of plants [9,10]. Collaboration with other conservation stewards is critical to the success of managing endangered species programs, improving conservation capacity, and increasing the impact of interventions [11,12].

Accordingly, the management and periodic updating of living collections enable botanical gardens to maintain their relevance in plant conservation. These institutions have a unique role in leading efforts to achieve the goals of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) [13], especially Target 8, which seeks to ensure that at least 75% of threatened plant species are in ex situ collections, preferably in the country of origin, and that at least 20% are available for recovery and restoration programs [4,6].

Founded in 1808 and located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden (JBRJ) occupies a total area of 143.98 hectares. In situ conservation takes place on 85.18 hectares, covering an area of Atlantic Forest adjacent to the Tijuca National Park. Ex situ conservation covers 38.8 hectares, following recent expansions in the cultivated landscape area. The topography is predominantly flat, but steeper to the north and northwest, reaching about 250 m [14,15] (see Figure 1 in [14]).

Its creation aimed to introduce and acclimate plants that supply spices from the West Indies. After profound modifications over decades, it currently functions as a research institute. Its mission today is to promote, carry out, and disseminate scientific research with an emphasis on flora, aiming at the conservation and valuation of biodiversity, as well as carrying out activities that promote the integration of science, education, culture, and nature [14,15].

In early 2024, our group worked on the second edition of a book entitled “Malvaceae cultivada no arboreto do Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro: a família do hibiscus” [16]. This was a scientific dissemination action authorized by the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden (JBRJ) and part of the series of books documenting the families present in the collection with the aim of providing information about the species to visitors. We found that our collection of the Malvaceae family consists of 63 species, representing a considerable increase (ca. 10%) compared to the last survey conducted in 2019, which recorded 57 species. Thus, the Malvaceae family does have the highest number of species cataloged so far, surpassing Bignoniaceae (44), Convulvulaceae (16), Costaceae (5), Heliconiaceae (13), Malpighiaceae (20), Melastomataceae (13), and Zingiberaceae (16). However, we are not implying that it is the most representative of the collection. In a recent publication [14], Malvaceae was cited as the fourth most representative family in number of species in the JBRJ living collection since Fabaceae (252), Arecaceae (154), and Myrtaceae (78) are the most representative families.

Based on the high number of species of the Malvaceae collection, we carried out a detailed survey focusing on its potential use in ex situ conservation strategies. Thus, the present study analyzed the current state of the family in this collection by cataloging each species, number of individuals, natural geographic distribution, and conservation status. A list of threatened Malvaceae species in Brazil not yet present in the JBRJ collection was compiled with the intention of directing efforts to collect and include specimens of these species in the arboretum for the purpose of ex situ conservation. In addition, recommendations are herein offered to improve the ex situ conservation of Malvaceae species in the arboretum.

2. Materials and Methods

We began our systematic cataloging of individuals present in the JBRJ arboretum in 2016 by using the institution’s planting records. During this process, individuals were taxonomically identified, by the APG IV (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) system, updating names as needed, and then photographed and georeferenced. Fertile branches were collected for integration in the collection of the institution’s herbarium (RB). This information was organized in spreadsheets. All data are made available on the Jabot platform (https://rb.jbrj.gov.br/arboreto/arboretoleaflet.php (accessed on 20 June 2024)), which is continuously updated. The distribution data and correct names of species were based on the platforms Flora e Funga do Brasil [17] and World Flora Online [18], and, when necessary, we consulted specific taxonomic treatments. For the state of conservation, we consulted the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list [19].

3. Results

Malvaceae is represented by 63 species cultivated in the JBRJ, including 216 individuals. They are mainly distributed across planting beds in sections 3, 9, and 22 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Planting beds with the highest concentration of Malvaceae individuals. (a) 3; (b) 9; (c) 22.

Malvaceae species from various parts of the world are found in the arboretum. Among them are species from Africa, Asia, and Oceania, such as Adansonia digitata, Azanza garckeana, Berrya cordifolia, Cola verticillata, Dombeya tiliacea, Durio zibethinus, Pterospermum acerifolium, Talipariti tiliaceum, Thespesia populneoides, and Triplochiton zambesiacus. Those of Neotropical origin are the most representative in number of species (43) and include Apeiba tibourbou, Cavanillesia umbellata, Ceiba pentandra, Eriotheca macrophylla, Herrania nitida, Hydrogaster trinervis, and species of Luehea and Pachira (Figure 2a). The collection presents at least one species of eight of the nine subfamilies of Malvaceae, lacking only Tilioideae.

Figure 2.

Data about species cultivated in JBRJ. (a) Native distribution; (b) conservation status.

Species of economic importance, including ornamentals and edibles, were also included in the collection. Ornamental species are found in many parts of the world, such as Ceiba speciosa, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, H. schizopetalus, Malvaviscus arboreus, Talipariti tiliaceum, and Thespesia populneoides. For the food industry, Durio zibethinus, Hibiscus acetosella, Theobroma cacao, and T. grandiflorum are cultivated.

Of the most cultivated native Brazilian species in the arboretum, the following stand out: Apeiba tibourbou (9), Ceiba pentandra (12), Ceiba speciosa (8), Pachira glabra (7), Patinoa paraensis (8), Pterygota brasiliensis (8), and Sterculia apetala (11). It is important to note that species cultivated in the JBRJ, including Ceiba jasminodora, Hydrogaster trinervis, Pachira manausensis, Pavonia alnifolia, Pavonia makoyana, and Pseudobombax munguba, can be considered endemic of a particular region or phytogeographic domain.

Below, we present a table listing all Malvaceae species cultivated in the arboretum, along with the number of individuals, the subfamily to which they belong, conservation state, and native distribution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Malvaceae species from the JBRJ arboretum.

Most species represented in the arboretum are not threatened or remain to be evaluated for their conservation status (Figure 2b). The collection is still lacking in the representation of endangered species, currently numbering only two, one EN (endangered) (Pseudobombax petropolitanum) and one VU (vulnerable) (Ceiba jasminodora). It also has only two DD (data-deficient) species, Luehea divaricata and Scleronema grandiflorum. One species, Dombeya x cayeuxii, has no present conservation status because it is a hybrid (see [20]).

4. Discussion

Mindful of GSPC mandates, namely Target 8, we surveyed the living collection of Malvaceae from JBRJ. The collection presents a high number of species, possibly one of the largest scientific collections of Malvaceae in the world. However, some changes should be considered to make the collection more effective for the ex situ conservation of species.

Although the collection presents a high number of species and high representativeness for the family, we observed that the number of individuals of some species is still insufficient to warrant their classification as ex situ conserved. More than half of these species present only one or two individuals (34), including all endangered or data-deficient species of the collection. For a given species to be considered ex situ conserved, the number of specimens in a collection is relative [5]. Nonetheless, we have concluded that the number of individuals above is insufficient for ex situ conservation, even without a specific analysis for each species. In some cases, this makes it impossible to produce fruits and seeds, as is the case of Ceiba jasminodora, a species that does not accept self-pollination and is represented by only one individual in the collection (Figure 3a). This is a reality that needs attention and an urgent strategy for reversal.

Figure 3.

Some species with a single individual in the JBRJ arboretum. (a) Ceiba jasminodora; (b) Spirotheca riveri var. rivieri.

In this sense, most of the specimens in the collection lack information about their origin and planting data, especially those included in the collection before the current century. This problem can be solved in the future by performing molecular studies of known native populations of each species and, thus, finding, by genetic similarity, the population of origin of the individuals cultivated in the collection.

Considering the proportion of the collection, we expected to find a greater number of endangered or data-deficient species. In the IUCN red list [19], 40 species of Malvaceae are listed as threatened or data deficient in the Brazilian territory (VU = 5; EN = 17; CR = 7; DD = 11). Since only 10% of these are represented in the collection, we cannot necessarily consider them preserved ex situ. To accomplish this, case-by-case studies must be conducted to understand how many individuals and from which native populations should be collected to effectively conserve them.

Understanding the reproduction system of Malvaceae species is still another issue relevant to their conservation since this can directly affect the viability of ex situ fruit and seed production. This implicates two particularly important cases in the family: (1) dioecious species and (2) species that do not accept self-pollination. The first is observed only in one species in the arboretum, Hydrogaster trinervis. This presents one female (pistillate flowers) and two male (staminate flowers) and is currently not considered threatened, despite occurring in a very restricted area of the Atlantic Forest. In the second case, some species of Malvaceae, such as Ceiba, do not accept self-pollination [21]. During field research, we observed that this apparently also occurs with Spirotheca riveri var. rivieri, a species that presents only one individual in the collection (Figure 3b), and it is one with no observable development of its fruits, even though it annually produces a large number of flowers, similar to that reported for C. jasminodora. Therefore, we emphasize the need for an updated database that contains reproduction information on endangered species of the Brazilian flora.

To improve the capacity of JBRJ to promote ex situ conservation of endangered species of Malvaceae from Brazil, we list all threatened or data-deficient species for the Brazilian territory (Table 2).

Table 2.

Threatened or data deficient Malvaceae species in Brazil. Not listed are those already in the JBRJ.

The recommendations listed above pertain to JBRJ’s Malvaceae collection. They reflect a quick response to obvious deficiencies and are to be considered as additional suggestions to those already described by the IUCN, but not replacing them [5].

To direct the collection and conservation of these species, we list below some further recommendations that would benefit efforts to collect, cultivate, and conserve Malvaceae species.

- (1)

- Perform a literature review of endangered and/or deficient species, mainly considering data on distribution, ecology, taxonomic synonymy, and reproduction of the species.

- (2)

- Re-evaluate conservation status as needed.

- (3)

- List by order of priority: (a) species with the highest possibility of population loss; (b) species without any protected population by conservation units; (c) species with highest ex situ reproduction potential; (d) species with higher production of seeds and fruits; and (e) species with a greater likelihood of surviving transport to the germination or planting site.

- (4)

- Consider the reproductive system of species before structuring a collection strategy.

- (5)

- Create a database for these species, mainly considering the places of occurrence and fruiting season. Based on these data, stipulate target locations for collection, giving priority to those with the possibility of collecting a greater number of species.

- (6)

- Carry out expeditions to perform collections in targeted localities based on the fruiting period of the species.

- (7)

- During the collection of fruits, seeds, and seedlings, make careful notes on vegetation formation, moisture, insolation, and soil characteristics, especially its composition and granulometry. Whenever possible, it is strongly advised that seedlings be bagged with the soil of origin, or at least a mixture thereof.

- (8)

- The number of cultivated seedlings or germinated seeds should be 50 to 75% higher than the final number expected for planting, considering the limitations of the populations of the selected species. In cases with populations with few individuals and/or suffering strong environmental pressure, it is preferable to collect fruits and seeds instead of seedlings.

- (9)

- Encourage the creation of a method for Malvaceae vegetative propagation by cuttings, which in some cases may allow the production of seedlings in species with low seed viability rates. In addition, individuals from cuttings represent a considerable gain of time compared to those originating from seeds by producing fruits and propagules more quickly.

- (10)

- Follow, as closely as possible, the environmental and pedological standards of the place of collection of native populations when choosing a site for planting individuals in the arboretum.

For some species, ex situ cultivation is advisable, but it will not result in significant conservation [22]. Items 3 (c) and (d) set out above help in the decision-making process, but the results of the introduction can go far beyond the simple success/failure of an individual’s cultivation. For example, individuals in the Tashkent (Uzbekistan) Botanical Garden (TBG) can remain in the vegetative stage for decades, or even bear fruit once with seeds damaged by parasites. Therefore, a decision tree was created in TBG for possible ex situ introductions (see [22]).

It is also necessary to perform molecular studies to understand the viability of populations and then prioritize them based on their genetic diversity. We understand that these studies require subsidies and financial resources. Thus, in the case of JBRJ’s Malvaceae collection, it is recommended that a more immediate strategy be considered for recovery in propagules and seedlings in the field while carrying out population genetics studies later and complementing the collection when necessary.

5. Conclusions

We recognize Malvaceae as a model family with which to commence studies focused on ex situ conservation of the endangered flora of Brazil. Having the 29 endangered species of this family conserved ex situ would represent the conservation of approximately 2% of the 1369 threatened plant species in Brazil [19]. It is a small number, but the most important contribution of this work will be the experience acquired through carrying out the process. The ex situ conservation of Malvaceae species, as described in this study, should be seen as a pilot project to be replicated in other plant groups. Thereafter, it is anticipated that within a few decades, we could have a robust and functional ex situ conservation project on a large scale, one that involves several domains of knowledge and institutions combined with enough financial support and human effort to maintain the work now so that it can be expanded by the next generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation and investigation, C.D.M.F. and M.G.B.; writing—review and editing and investigation, J.R.d.M. and M.A.N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author thanks the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES–Finance Code 001) for financial support (process number: 88887.933206/2024-00). The second author thanks the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES–Finance Code 001) for financial support (process number: 88887.824627/2023-00).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The supporting data can be found in the JBRJ collection management system (https://rb.jbrj.gov.br/arboreto/arboretoleaflet.php (accessed on 20 June 2024)).

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical team from JBRJ who helped us collect samples during this research, especially Ricardo Matheus and Fabiano Rodrigues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maunder, M.; Higgens, S.; Culham, A. The Effectiveness of Botanic Garden Collections in Supporting Plant Conservation: A European Case Study. Biodivers. Conserv. 2001, 10, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, K.; Kramer, A.T.; Guerrant, E.O. Getting Plant Conservation Right (or Not): The Case of the United States. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 175, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, N.; da Cunha, T.S.; Do Couto Pereira, R.; Rodrigues Turini, L.; Rocha Barbosa, O.; Ribeiro de Almeida, J. Gestão de Jardins Botânicos. Rev. Int. Ciências 2023, 13, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse Jackson, P.; Sutherland, L.A. International Agenda for Botanic Gardens in Conservation; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Surrey, UK, 2000; ISBN 0952027593. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN/SSC. Guidelines on the Use of Ex Situ Management for Species; IUCN Species Survival Commission: Gland, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock, S.L.; Jones, M. Conserving Europe’s Threatened Plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Surrey, UK, 2009; ISBN 9781905164301. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, V.H.; Iriondo, J.M. Plant Conservation: Old Problems, New Perspectives. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 113, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, S.F. Botanic Gardens and the Conservation of Tree Species. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.S.; Lowry, P.P.; Aronson, J.; Blackmore, S.; Havens, K.; Maschinski, J. Conserving Biodiversity through Ecological Restoration: The Potential Contributions of Botanical Gardens and Arboreta. Candollea 2016, 71, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender, N.; Donnelly, G. Intersecting Urban Forestry and Botanical Gardens to Address Big Challenges for Healthier Trees, People, and Cities. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, A.D.; Watkins, J.H.R.; Baxter, T.J.; Miesbauer, J.W.; Male-Muñoz, A.; Martin, K.W.E.; Bassuk, N.L.; Sjöman, H. Using Botanic Gardens and Arboreta to Help Identify Urban Trees for the Future. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.; Laliberté, B.; Guarino, L. Trends in Ex Situ Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources: A Review of Global Crop and Regional Conservation Strategies. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2010, 57, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. The Global Strategy for Plant Conservation: 2011–2020; Botanic Gardens Conservation International for the Convention on Biological Diversity: Richmond, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781905164417. [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida, T.M.H.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Peixoto, A.L. Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden: Biodiversity Conservation in a Tropical Arboretum. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.L.M.N. Diversidade Biológica Nos Jardins Botânicos Brasileiros; Rede Brasileira de Jardins Botânicos: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Mattos, J.R.; Ferreira, C.D.M.; Bovini, M.G.; Coelho, M.A.N. Malvaceae, Cultivadas No Arboreto Do Jardim Botânico Do Rio de Janeiro: Família Dos Hibiscos, 2nd ed.; Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2024; ISBN 9788560035281. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro Flora e Funga Do Brasil. Available online: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- WFO World Flora Online. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Version 2024-1; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria; Standards and Petitions Committee: Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, P.; Semir, J. A Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Ceiba Mill. (Bombaceae). An. Jard. Bot. Madr. 2003, 60, 259–300. [Google Scholar]

- Volis, S. Living Collections of Threatened Plants in Botanic Gardens: When Is Ex Situ Cultivation Less Appropriate than Quasi In Situ Cultivation? J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 4, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).