Abstract

Wild food plants (WFPs) are consumed by the indigenous communities in various parts of the world for food, nutrition, and medicinal purposes. They are usually collected from the wild and sometimes grown in the vicinity of the forests and the dwellings of the indigenous people in a way such that they are not far from their natural habitats. WFPs are important for the food and nutritional requirements of the indigenous communities. The WFPs are seasonal and collected from the wild whenever they are available. Therefore, the food menu of the tribal co mmunities changes with the seasons. A number of studies have demonstrated various WFPs consumed by indigenous communities including India. The results show that an enormous diversity of WFPs is consumed by the indigenous people of India. However, a few studies also suggest that the consumption of WFPs among the indigenous communities is declining along with the dwindling of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge linked to the collection, processing, cooking, storage, and limited cultivation of WFPs. India can leverage the network of its botanic gardens for the conservation of its wild food plant resources, the traditional and indigenous knowledge linked to it, and its popularization among the citizens within the framework of Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC). This article provided an overview of the need to focus on WFPs, limitations of current studies, and role of botanic gardens in the conservation of wild food plants through the implementation of GSPC. This article further provided a framework for the role of botanic gardens in the popularization of WFPs, increasing the awareness about their importance, documentation, and preservation of the traditional knowledge linked to various aspects of WFPs within the GPSC framework.

1. Introduction

Wild food plants (WFP) are an important group of plants consumed by the tribal and indigenous communities in various parts of the world [1,2,3]. WFPs are collected from their natural habitats by the indigenous communities for their consumption [2]. Various studies from different parts of the world have reported the availability of WFPs and their consumption [4]. A huge diversity of WFPs exist in Africa, Asia, and South America, and many indigenous communities still collect and consume them for nutritional as well as medicinal purposes [1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Various studies have documented the diversity of WFPs in India. A recent study by Ray et al. [11] found that 1,403 species belonging to 184 families are consumed in different parts of India. Studies also show the nutritional and medicinal importance of a number of wild food plants [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, WFPs offer an important opportunity towards eradication of poverty, hunger, and malnutrition, if not in totality at least significantly [13,19]. The WFPs can contribute to ensuring food security of the people and towards the realization of global goals, also known as sustainable development goals [21]. India is home to many WFPs such as leafy vegetables, nutritious fruits, tubers, edible stems, and medicinal plants, including myco-foods such as mushrooms [11,12,21,22,23,24,25]. So far, attention has been paid towards leveraging medicinal plants, but WFPs largely remain ignored because of the underestimation of their economic and nutritional importance and their contribution towards climate-resilient cultivation practices [26]. The WFPs are an important resource and offer great opportunities for India to leverage its potential, but the opportunities need to be tapped sooner rather than later. Though there are studies regarding the usage of plants by various communities in different parts of India, especially in the rural and tribal areas, many of these studies have accentuated their identification, documentation, and classification based on their family or parts used. Most of these studies are ethnobotanical in nature, focusing on the documentation of the traditional knowledge associated with the collection, consumption, mode of preparation, processing, and storage of the WFPs. However, crucial studies, such as those on dwindling nature of the usage of WFPs in recent years, the overharvesting pressure on the regeneration potential of the WFPs, and cultivation potential of the WFPs beyond their natural habitats, have not been attempted, except a few studies [27]. A successful cultivation of WFPs outside their natural habitats is feasible, depending on the species at hand and on its use value in the farmers’ perspective [27]. Considering the importance of wild food plants for future food security and the role of wild genetic stocks in the improvement of the currently available food plants, we highlight the need to focus on WFPs and the limitations associated with the current ethnobotanical studies, addressing the current bottlenecks and the roles of botanic gardens towards this end. The GSPC, which is adopted by various governments of the world, provides an important framework for the conservation of global plant biodiversity through various approaches [28,29]. The GSPC initially aimed to achieve 16 targets that are distributed in five broad objectives by 2020 [30]. Although the targets as envisaged under GSPC have not been achieved despite considerable progress, the framework embodied by the GSPC remains relevant even after 2020. If GSPC strategy is implemented in toto by the botanic gardens in India for the conservation of wild food plant resources and the ethnobotanical and indigenous knowledge linked to it, it can deliver results. The conservation of WFPs and the indigenous traditional knowledge linked to it are in line with various targets of the GSPC [28].

Botanic gardens of the world have immensely contributed towards the ex situ conservation of the vascular plants, and their role is predicted to be even more under the climate change [31,32]. Considering the issues related to food security and the importance of biodiversity and genetic resources for securing future food security, the roles of botanic gardens are increasingly considered as multifunctional ecological resources [33,34,35,36]. The WFPs are one of the most important components of food security programs and efforts must be taken to leverage the network of botanical gardens to extend research and education on WFPs for a hunger-free world. India has a vast network of botanic gardens, and they can act as important ecological resources as well as centers of conservation and technological innovations. With this background, the article specifically focused on the future roles of botanical gardens towards popularization and ex situ conservation of WFPs, preservation of the ethnobotanical knowledge associated with WFPs, and scientific validation of the ethnobotanical knowledge using modern scientific tools within the GSPC framework.

2. Why Focus on WFPs?

The global diversity of food crops is declining due to over-emphasis on a few domesticated and cultivated crops. It has been reported that about 70% of global food production comes from less than 15 species [37,38]. The reliance on a limited number of domesticated species despite the availability of a large number of edible food plants in the wild shows that the cultivated species tap a minute fraction of the global genetic diversity. It means that much of the biodiversity is yet to be explored for new crops that can be used for the production of foods in the future. Considering the limited number of crop plants in the current food supply and impact of climate change regimes on the homogenized usage of crops [39], much research is needed towards recognizing alternative crop resources such as WFPs, and realizing their potential benefits and the goals of conserving their germplasm. Steps are needed to identify crop wild relatives of the commercial crops that we use today and which can be used for the current crop improvement programs either through conventional breeding programs or gene modification as well as gene editing techniques. In general, India must emphasize the importance and roles of WFPs for the future. Considering the vast tribal population of India and the diversity of wild edible foods they consume [11], steps must be taken towards increasing research on WFPs and their utilization for food and nutritional purposes [40]. Studies regarding usage of wild plants by different communities across states are available, but crucial aspects such as their consumption patterns, factors required for their optimal growth, their timing of flowering, mode of propagation, presence of any anti-nutrients, and their nutraceutical potential have not been given due attention. These studies are fundamental to WFPs and are necessary to understand the fundamentals of the wild food plants consumed by indigenous communities.

On account of increased rural-to-urban migration, people usually take to the mainstream food crops as their income levels rise above average [40,41]. It becomes even more critical to enhance our research on WFPs considering at least three reasons. Firstly, the knowledge on the usage of these plants is mostly orally transmitted and prone to erosion over time as people change their lifestyles [42]; secondly, the consumers’ reliance on a limited number of crop plants necessitates the bioprospecting and identification of new wild food plants [39,43]; thirdly, the urgency to consider FAO’s six important dimensions of ensuring food security, viz., availability, access, utilization, stability, agency, and sustainability [44]. Since the WFPs are mostly gathered from the wild, they are evolving along with the changing environmental conditions at their own pace, unlike domesticated crop plants. The WFPs also offer important benefits over domesticated crop plants because of their lower vulnerability and increased resilience to climate change [45]. Another reason for supporting their increased consumption is that the WFPs’ ability to act as shock absorbers in times of inflation-related price hikes, as they do not involve long-distance transportation and market inflation hardly impacts their prices as they are consumed in local markets on small scales [46]. Besides this, WFPs can grow under the canopy trees, providing a better option for multiple cropping systems. WFPs may not be able to completely diminish supply-demand food gap, but they can significantly reduce it and restrict it from widening further [47]. On the other hand, direct harvesting of WFPs from the wild might foster unsustainable practices which, in turn, might lead to issues of species extinction or endangerment [2,48]. This highlights the importance of identifying destructive and harmful practices associated with the harvesting of WFPs and devising strategies that are sustainable. For instance, a sexually reproducing wild plant consumed for its vegetative parts (such as leaves or stem only) might be harvested before setting seed, thus impairing its reproduction. Therefore, the scientific management of WFP resources cannot be restricted to in situ or ex situ conservation but must expatiate on reaching out to indigenous communities and raise their awareness regarding best practices for harvesting while preserving the reproductive potential of WFPs. The excessive exploitation of some wild food plants for industrial purposes is also reported and studies suggest that there should be policies in place to deal with industrial overexploitation of the WFPs. Oral tradition of ethnobotanical knowledge and its vulnerability to erosion over time coupled with climate change, over-exploitation, migration, and lifestyle-led dwindling may result in the substantial disappearance of these food plants sooner or later. These apprehensions and opportunities require concerted efforts from various corners including botanic gardens, curators and managers of botanic gardens, policy makers, conservation botanists, and ethnobotanists.

3. Redefining the Role of Botanic Gardens within the Framework of GSPC

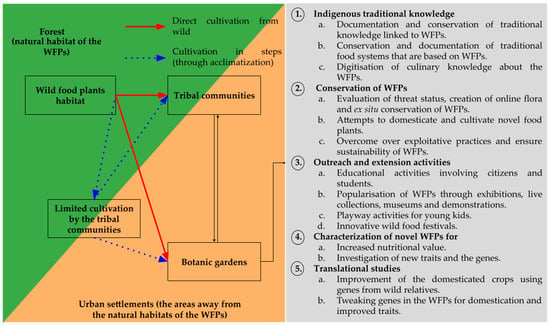

Like many other botanic gardens in the world which are doing excellent work, India’s botanic gardens have also contributed towards the conservation of the flora and research and extension activities [49,50,51,52]. Considering the current global situation and the future exigencies in various forms, a study report by Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG), School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester and commissioned by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) suggested revamping and repositioning of their core philosophies, values, and practices so that they can contribute more towards societal welfare and create societal impact [53]. Botanic gardens in general must implement the GSPC framework that specifically provides guidelines for the conservation of plant diversity. Botanic gardens must redefine their roles and mandates as per the demands of the 21st century [52,53]. The GSPC is a general framework for the conservation of global biodiversity. However, the botanic gardens must implement the GSPC guidelines for the conservation of the WFPs and their sustainable utilization. Multiple targets that were envisaged under the GSPC are still relevant. If we link botanic gardens and wild food plants with the GSPC, the steps taken to conserve the wild food plants and the indigenous knowledge linked to their use falls within the GSPC framework. Table 1 explains an outline action plan for the conservation of WFPs. The action plan is in line with GSPC. For example, Targets 1 and 2, which provide for the creation of an online flora for all the known plants and assessment of the status of the plants, respectively, are also important for wild food plants. Their flora as well as evaluation of the threat status are essential for devising the conservation strategies (Target 3). Many of the WFPs are economically important and some of them are wild relatives of the crops that we grow today; therefore, their conservation is of immense importance (Target 9). Wild food plants are harvested from the wild, so there are some inherent threats to their survival, such as premature harvesting and overharvesting; therefore, scientific studies must focus on the issues related to unsustainable practices and the identification thereof will help devise better practices that are sustainable (Targets 11, 12). The indigenous knowledge that is associated with the WFPs, their collection, preparation, storage, and processing must be protected. The indigenous culinary knowledge is also important and must be documented and digitized within the botanic gardens (Target 14). Finally, it is essential to enhance the capacity building of botanic gardens, strengthen their capabilities, and increase cooperation and collaboration between the regional, sub-regional, and national botanic gardens (Targets 15, 16). Figure 1 explains the future roles of botanic gardens.

Table 1.

Action plan for the conservation of WFPs and the indigenous ethnobotanical knowledge linked to it through the implementation of GSPC.

Figure 1.

Redefining future roles of botanic gardens for the conservation and sustainable use of WFP resources of India. To increase the usage of wild food plants and enhance their cultivation, we must focus on the species that can be directly transplanted from their natural habitats in the agricultural fields or in the homesteads or botanic gardens (red color represents a direct route from natural habitats to their new habitats of cultivation). Tribal communities practice direct cultivation near the vicinity of the natural habitats of the WFPs or away from the natural habitats depending upon the ease of growth. The blue dotted lines represent the indirect route of cultivation away from the natural habitats through a two-step process because plants from natural habitats may not grow at longer distances because of the changes in climate. Therefore, acclimation is required before their introduction at large distances. The green-colored triangle shows the natural habitat of the WFPs, whereas the orange color represents the new habitat of the WFPs, such as botanic gardens or agricultural fields.

3.1. Estimation, Creation of Online Floras and Ex Situ Conservation of WFPs

In India, there are a number of national botanic gardens which have collections of various types of plants including economically important plants ([54]; also see Table 2). The botanic gardens owned by universities and colleges are managed by the faculty members of the respective departments and perform limited activities related to various groups of plants. However, extensive studies and exercises involving specific WFPs are not reported that point towards potential gaps in the ex situ conservation of WFPs in the botanic gardens of India. Botanic gardens mainly focus on medicinal, rare, endangered, and endemic groups of plants. Colleges and universities must also encourage the students to take up field studies on collection of data related to WFPs and their digitization. The online herbarium of all the wild food plants collections must be completed (Target 1). However, many students in the rural and tribal areas still are not well versed in computers and digital platforms. Their digital empowerment through various digital missions will enable digitization of the records associated with WFPs. Most of the undergraduate students coming from rural and tribal families are familiar with the WFPs that are used in their localities; therefore, the preparation of the herbarium sheets and their digitization under the mentorship of the teachers will help in the long run.

Table 2.

List of botanic gardens involved in WFPs research in India, their location, specialization, collections and URL/website.

Following digitization of flora and considering the huge diversity and economic importance of WFPs in India, attempts to conserve those WFPs which face threats must be made (Target 2). The prioritization of the conservation of WFPs must be based on threats, usefulness, and rarity (Target 5). The wild relatives of the crop plants also should be conserved as a priority as they are important genetic resources for crop improvement programs (Target 9). To analyze the threats, usefulness, and rarity, taxonomic and nutritional profiling studies could help. The ex situ conservation of the WFPs will be possible only if they are acclimated to grow outside their natural habitats. Many of the WFPs may not have been exposed to the environments beyond their natural habitats. Therefore, it is extremely difficult to raise them in botanic gardens. Their actual ex situ conservation may involve several steps including acclimation in the proximity of their natural habitats and then their transplantation into the botanical gardens located away from their natural habitats. However, the species that need prioritization for conservation must be conserved in their natural habitats or in proximity to the natural habitats. If there is a threat to the survival of the WFPs due to over-exploitation, over-harvesting, international trade, and unsustainable practices, then steps must be taken to ensure the sustainability of the WFPs (Targets 11, 12).

3.2. Documentation and Conservation of Indigenous Traditional Knowledge, Local Innovations and Practices Linked to WFPs

Botanic gardens are located in various universities and colleges of different parts of India. The botanic gardens that are located in the rural and tribal areas must be strengthened and encouraged to undertake those studies that are linked to the documentation of traditional knowledge related to WFPs. Proper documentation of the traditional indigenous knowledge and the innovative practices linked to the WFPs must also be carried out (Target 13). The dwindling traditional knowledge about the culinary preparations from the WFPs also points towards its conservation. Botanic gardens can act as important points of contact with the traditional knowledge holders to save the age-old plant-human cultural interactions.

3.3. Awareness about WFPs Diversity, Its Importance and Popularization

The botanic gardens should further act as important centers of WFP popularization using various approaches such as exhibitions, live collections, demonstrations, and audiovisual materials (Target 14). Schoolchildren should be encouraged to visit botanic gardens and informed about the WFP resources, their uses, and roles in the future. The live collections of WFPs will provide them more information about the identities of the plants and may familiarize them with the usefulness of the WFPs in the ethnic food traditions of the indigenous communities. Awareness programs regarding the WFP diversity and its importance and need for conservation will deliver encouraging results.

3.4. Enhancing Cooperation among the Botanic Gardens

The botanic gardens of India must be linked digitally and there should be enhanced cooperation and coordination between different botanic gardens. The interlinking of the gardens will improve the conservation efficiency. The best practices from one another can be adopted. The sharing of technical know-how between the different regional, sub-regional, and national botanic gardens will empower those gardens which are less efficient and need more support.

3.5. Limited Cultivation and Domestication Attempts

As discussed in the preceding sections, it may be difficult to conserve WFPs ex situ before sufficient acclimatization. However, the WFPs that have been sufficiently acclimatized must be further attempted for further domestication. Domestication may take many years; however, recent approaches involving speed breeding and de novo domestication could help in accelerating the process of domestication, which is essential for future resilience and readiness under unpredictable climatic conditions.

4. Botanical Survey of India: Current Status and Future Roles of the 130-Year-Old Institution

In recent years, we have seen significant developments in the establishment of new botanic gardens in India. However, it is very important to mention the role of the Botanical Survey of India (BSI), which was established on 13 February 1890. Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden, Howrah, which is one of the oldest botanic gardens in the world and spread over an area of 300 acres, is a constituent part of BSI [72]. BSI was conceived to “explore the frontier and trans-frontier regions in north-west Punjab, the Central Provinces, Central India, Rajputana, Assam, Burma and the Andamans” [73]. The proposal for setting up the survey was accepted in July 1887, and it finally came into existence on 13 February 1890 [73]. The objectives of the survey were formulated as “Exploring the vegetable resources of the Indian Empire coordinating the botanical work in different parts of India” [73,74]. This was a watershed mark 130 years ago in recognizing the importance of India’s vegetable resources. After independence, with a changed political system, the BSI was reorganized on 29 March 1954 with an aim to “boost the economy”. The revised objectives were formulated in 1954 by GoI as: “(1) undertaking intensive floristic surveys and collecting accurate and detailed information on the occurrence, distribution, ecology and economic utility of plants in the country; (2) collecting, identifying and distributing materials that may be of use to educational and research institutions; and (3) acting as the custodian of authentic collections in well planned herbaria and documenting plant resources in the form of local, district, state and national flora (BSI)” [75]. Although new revised objectives expanded the scope of BSI, it slightly deviated from its prime objective of exploring the vegetable resources.

Now, after 130 years of its existence, there is no doubt that BSI has made significant strides and contributions in various areas such as ex situ conservation, floristic and taxonomic studies, exploration of plant resources, protected areas, and ethnobotanical studies. With regard to vegetable resources, BSI has made efforts in the collection, introduction, multiplication, and maintenance of the germplasm of wild, edible plants and other economically important plant species. Considering the 130-year-old original vision of the British government, which aimed to explore the vegetable resources of the country, its efforts in the field of exploration of vegetable resources of the country are noteworthy. Most of the Indian universities and colleges involved in teaching and research on botany own botanic gardens. Many of the botanic gardens of the Indian universities have contributed immensely to the conservation of local genetic resources. However, an integration of the various regional, sub-regional, and national botanic gardens has not taken place yet. There is no formal database on the various botanic gardens of India. The botanic gardens of India need to be integrated into a common database showcasing their collections, specializations, and priority areas. The development of an online database and the appointment/constitution of a national taskforce/body/organization to coordinate with the various botanic gardens and for the prioritization of the conservation of the wild genetic resources are crucial. With the changed demands of the 21st century, the botanic gardens of the country must reorient their goals and mandates towards the conservation of WFPs.

Considering the importance of wild resources at a time when the world is moving towards achieving sustainable development goals, sustainable production, and consumption patterns, India must also expedite the process of the country’s wild food plant resources. To date, the task of exploration of vegetable resources is a work in progress, and further studies focusing on the domestication and cultivation of wild genetic resources for sustainable use must be taken up. The work carried out by BSI in exploration, discovery, and documentation is highly commendable. Other botanic gardens of the country can also draw inspirations from BSI and its associated botanical garden, Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden. The botanic gardens in various corners of the country must also include other food plants such as wild fruits, leafy vegetables, and myco-foods such as wild edible mushrooms before they disappear completely from the food menu. Conservation of WFPs is important especially under the climate change regimes, and studies suggest that domesticated crops are more prone to abiotic and biotic stresses. The wild food plants which grow in the wild may be more stress tolerant and may provide an option towards diversifying the food basket [43,45]. The WFPs may also act as sources of horticulturally important genes for crop-improvement programs. The recognition of potential of WFPs is the first step and must be seriously taken up with respectable funding and short-term and long-term goals must be set for creating a WFPs germplasm and also for creating capacities for cultivation of WFPs for commercial purposes as well as for carrying out applied research. India is already late in taking steps towards securing wild vegetable resources; this area needs an immediate attention of the policy makers and the scientific community and they must take concerted steps to create a national facility for the WFPs of India. Both in situ and ex situ steps must be taken for their conservation and propagation, but, most importantly, the expansion of translational research. This would further ensure food security in addition to providing livelihood opportunities to the people involved in these WFP programs.

5. Strengthening Institutional Botanic Gardens

Many of the colleges and universities run botanic gardens which are managed by the botany departments. However, many of them are involved in academic research activities. The departmental botanic gardens in the universities and colleges must be strengthened with the required staff, and they should be empowered to undertake conservation activities related to WFPs (Targets 15, 16).

6. Financing Institutional, Non-Institutional and Private Botanic Garden Initiatives

The institutional, non-institutional, and private or NGO-run botanic gardens must be financed sufficiently. New frontiers of funding must be explored including corporate social responsibility funding. Many of the corporates have biodiversity, sustainability, and conservation as one the key areas of CSR fund-allocation policies; therefore, the CSR funds should be channeled towards financing botanic gardens and strengthening them technically as well as with manpower. M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), established by M. S. Swaminathan in 1988, is one of the important collections of wild resources of plants including wild edible plants. The associated M. S. Swaminathan Botanical Garden (MSSBG) of MSSRF is involved in the conservation of the wild plant resources for dietary requirements [62]. Similar successful models should be replicated in different parts of the country based on the local availability and popularity of the WFPs.

7. Conclusions

Wild food plants are important due to their multiple benefits. India is a vast country with diverse biogeographical regions. The country is also inhabited by diverse tribal groups with different dietary patterns and traditions based on their geographical locations. Many of the tribal communities in India still consume the WFPs by directly collecting from the wild and have developed traditional food systems based on them. Archaeological and archaebotanical data suggest that Indians used wild food plants in times of situations when there were yield losses in the mainstream crops, suggesting the importance of wild food plants during the natural disasters or bad years when yields are lower [76]. Scientific evidence suggests the importance of WFPs for future food security, especially under climate change. Being vast and diverse in its tribal population, food plants, and food traditions, India also has an informal network of botanic gardens especially in the universities and colleges. The informal network of botanic gardens can be formalized by integrating them. A national authority can be established to oversee, direct, and fund the botanical gardens. The botanic gardens need to redefine the mandates and roles to implement the GSPC guidelines. Recognizing the vast wild food plant resources and their future roles in the alleviation of poverty and hunger, steps must be taken to strengthen the botanic gardens and must be encouraged to incorporate the components of wild food plants for food security. The conservation of WFPs and the associated indigenous knowledge must be prioritized. The botanic gardens of the country must reorient their roles towards creating societal impact considering the environmental issues such biodiversity loss, sustainable development goals, and sustainable management of resources. India must draw inspiration from successful traditional food plant projects (for example, The African Orphan Crops Consortium [77]) as the growing evidence shows that WFPs provide significant health and economic benefits to the indigenous communities. India should also make attempts towards preserving and revitalizing traditional food systems which are based on WFPs. Finally, to leverage WFPs for ensuring food security and achieving sustainable development goals, India must focus on five R’s: (1) recognition of its wild food plant resources, (2) realization of the potential of botanic gardens and benefits of WFPs for sustainable food security, (3) redefining the roles and mandate of its botanic gardens, (4) promoting translational research on WFPs, and (5) reimaging synergies between different regional and national botanic gardens.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the continuing support by Central University of Kerala, Kasaragod, Kerala, India. I also knowledge the anonymous reviewers and academic editor for their valuable, and critical comments/suggestions that helped improve this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, K.; Pieroni, A. Folk Knowledge of wild food plants among the tribal communities of Thakht-e-Sulaiman Hills, North-West Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawera, L.; Khomsan, A.; Zuhud, E.A.M.; Hunter, D.; Ickowitz, A.; Polesny, Z. Wild Food plants and trends in their use: From knowledge and perceptions to drivers of change in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Foods 2020, 9, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Langenberger, G.; Sauerborn, J. A Comparison of the wild food plant use knowledge of ethnic minorities in Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve, Yunnan, SW China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Khan, S.M.; Pieroni, A.; Haq, A.; Haq, Z.U.; Ahmad, Z.; Sakhi, S.; Hashem, A.; Al-Arjani, A.-B.F.; Alqarawi, A.A.; et al. A Comprehensive appraisal of the wild food plants and food system of tribal cultures in the Hindu Kush Mountain range; A Way forward for balancing human nutrition and food security. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, G.F. Wild food plants used by the indigenous peoples of the South American Gran Chaco: A general synopsis and intercultural comparison. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2010, 83, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotto, I.M.; Amorozo, M.C.d.M.; Neto, G.G.; Oldeland, J.; Damasceno-Junior, G.A. Knowledge and use of wild edible plants in rural communities along Paraguay River, Pantanal, Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Garcia, G.S.; Struik, P.C.; Johnson, D.E. Wild harvest: Distribution and diversity of wild food plants in rice ecosystems of Northeast Thailand. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 78, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Lamxay, V.; Tongchan, K.; Xayphakatsa, K.; Phimmakong, K.; Radavanh, S.; Kanyasone, V.; Pietras, M.; Karbarz, M. Wild food plants and fungi sold in the markets of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurney, R.P.H.; Griffin, C.; Paul, A.A.; Greenberg, D.C. The Nutritional composition of African wild food plants: From compilation to utilization. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2004, 17, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, P.M.; dos Santos, G.M.C.; Barbosa, D.M.; Gomes, L.C.A.; da Costa Santos, É.M.; da Silva, R.R.V. Local knowledge as a tool for prospecting wild food plants: Experiences in Northeastern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Ray, R.; Sreevidya, E.A. How many wild edible plants do we eat—Their Diversity, use, and implications for sustainable food system: An exploratory analysis in India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttahariyappa, H.R.; Setty, R.S.; Ravikanth, G. Dependency and economic benefits of use of wild food plants use among tribal communities in Malai Madeshawara hills wildlife sanctuary, Southern India. Future Food J. Food Agric. Soc. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, S.; Narzary, H. Nutritional Value, phytochemicals and antioxidant property of six wild edible plants consumed by the bodos of North-East India. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 10, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zhuo, J.; Liu, B.; Long, C. Eating from the wild: Diversity of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-La Region, Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, C.R.; Khruomo, N. Assessment of Nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of some popular underutilized edible crops of Nagaland, India. Nat. Resour. 2021, 12, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Amoo, S.O.; Ncube, B.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Phytochemical and antioxidant properties of unconventional leafy vegetables consumed in Southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 84, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, V.; Signorini, M.A.; Tonini, M.; Bruschi, P. Wild medicinal and food plants used by communities living in Mopane woodlands of Southern Angola: Results of an ethnobotanical field investigation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 177, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, D.; Wang, G.-T.; Wen, J.; Wang, R.-J. Nutritional and functional properties of wild food-medicine plants from the coastal region of South China. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2020, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyman, M.V.; Afolayan, A.J. The suitability of wild vegetables for alleviating human dietary deficiencies. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2006, 72, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguma, H.T. Wild edible plant nutritional contribution and consumer perception in Ethiopia. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 2958623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Komal; Ramchiary, N.; Singh, P. Role of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and indigenous communities in achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajurel, P.R.; Doni, T. Diversity of wild edible plants traditionally used by the galo tribe of Indian Eastern Himalayan State of Arunachal Pradesh. Plant Sci. Today 2020, 7, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.C.; Pradheep, K.; Chaurasia, O.P.; Sood, S.; Sharma, R.M.; Singh, A.; Negi, R. Genetic resources of wild edible plants and their uses among tribal communities of cold Arid Region of India. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DW. Keeping Indigenous Wild Food Traditions Alive in India. DW. 4 May 2021. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/keeping-indigenous-wild-food-traditions-alive-in-india/a-57387215 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Chandrasekara, A.; Josheph Kumar, T. Roots and tuber crops as functional foods: A review on phytochemical constituents and their potential health benefits. Int. J. Food Sci. 2016, 2016, 3631647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilgrim, S.E.; Cullen, L.C.; Smith, D.J.; Pretty, J. Ecological knowledge is lost in wealthier communities and countries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Garcia, G.S. Management and motivations to manage “wild” food plants. A case study in a mestizo village in the amazon deforestation frontier. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Global Strategy for Plant Conservation: 2011–2020; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Richmond, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-905164-41-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock, S.L.; Botanic Gardens Conservation International. GSPC: Global Strategy for Plant Conservation: A Guide to the GSPC: All the Targets, Objectives and Facts; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Richmond, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-905164-37-0. [Google Scholar]

- CBD Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Succeeds in Aligning Actions to Protect Plant Diversity around the World. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/gspc/ (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Primack, R.B.; Miller-Rushing, A.J. The role of botanical gardens in climate change research. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, J.; Güsewell, S.; Kreft, H.; Kuzevanov, V.Y.; Lehvävirta, S.; Parmentier, I.; Pautasso, M. Species-richness patterns of the living collections of the world’s botanic gardens: A matter of socio-economics? Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzevanov, V.; Nikulina, A.N. Towards the definition of the term ‘ecological resources’. Bull. Krasoyarsk State Agric. Univ. 2016, 5, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzevanov, V.; Ochirbat, G.; Enkhtuya, L.; Nanjidsuren, O. Botanic gardens of mongolia—New scientific, ecological and socially significant resources: History of establishment and prospects. East Sib. J. Biosci. 2021, 102, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzevanov, V.; Sizykh, S.; Gubiy, E. Botanic gardens and arboreta as world ecological resources. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Environmental Sciences of the Korean Environmental Sciences Society, Irkutsk, Russia, 1–7 July 2014; pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzevanov, V.; Gubiy, E. Botanic gardens as world ecological resources for innovative technological development. Proceedings of Irkutsk State Univ. (Biology, Ecology). [Izvestiya Irkutskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta, Seria Biologia, Ecologia]. Izv. Irkutsk. Gos. Univ. Ser. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 10, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, D.; Jackson, W.; Bender, M.; Pickett, W. Perennial grains—An ecology of new crops. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 1986, 11, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Ibarra, J.; Morrell, P.L.; Gaut, B.S. Plant domestication, a unique opportunity to identify the genetic basis of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumsky, S.; Hickey, G.; Pelletier, B.; Johns, T. Understanding the contribution of wild edible plants to rural socialecological resilience in semi-arid Kenya. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M. Nutrient content of important fruit trees from Arid zone of Rajasthan. J. Hortic. For. 2009, 1, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.J.; Turner, K.L. “Where our women used to get the food”: Cumulative effects and loss of ethnobotanical knowledge and practice; case study from Coastal British Columbia. Botany 2008, 86, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnatje, T.; Peñuelas, J.; Vallès, J. Reaffirming ‘ethnobotanical convergence’. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Lammerts van Bueren, E.T.; Ceccarelli, S.; Grando, S.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Ortiz, R. Diversifying food systems in the pursuit of sustainable food production and healthy diets. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLPE. Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative towards 2030. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Fentahun, M.T.; Hager, H. Exploiting locally available resources for food and nutritional security enhancement: Wild fruits diversity, potential and state of exploitation in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talberth, J.; Leopold, S. Reviving Dormant Ethnobotany: The Role of Women and Plant Knowledge in a Food Secure World. 2012. Available online: https://sustainable-economy.org/reviving-dormant-ethnobotany/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Bharucha, Z.; Pretty, J. The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2913–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, L.; Homewood, K.; Dawson, T.P.; Diazgranados, M. Sustainability of wild plant use in the Andean community of South America. Ambio 2021, 50, 1681–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BSI. Ex-Situ Conservation. Available online: https://bsi.gov.in/page/en/ex-situ-conservation (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Singh, P.; Dash, S.S. Indian Botanic Gardens—Role in Conservation, 1st ed.; Botanical Survey of India: Kolkata, India, 2017; ISBN 9788181770929.

- Deshpande, S.M.; Yadav, S.R. Role of botanical gardens in conservation of rare plants: A case study of lead botanic garden of Shivaji University. Indian For. 2017, 143, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Novy, A. The role of botanic gardens in the twenty-first century. CAB Rev. 2016, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.; Jones, C. Redefining the Role of Botanic Gardens—Towards a New Social Purpose; Botanic Gardens Conservation International: Surrey, UK, 2010; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- CBD. CBD India (Directory of Botanic Gardens). Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/in/in-ex-bg-en.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Sims Park—Coonoor, The Nilgiris District, Tamilnadu, India. Available online: https://nilgiris.nic.in/tourist-place/sims-park-coonoor/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- BSI. BSI Garden. Available online: https://bsi.gov.in/garden-page/en?rcu=140,21 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Assam State Zoo cum Botanical Garden Assam State Zoo Cum Botanical Garden. Principal Chief Conservator of Forest & Head of Forest Force|Government Of Assam, India. Available online: https://forest.assam.gov.in/information-services/assam-state-zoo-cum-botanical-garden (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- BGCI. Barapani Experimental Garden. Available online: https://tools.bgci.org/garden.php?id=876?id=876 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- JNTBGRI. Jawaharlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute. Available online: https://jntbgri.res.in/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- MBGIPS. KSCSTE MBGIPS—KSCSTE. Available online: https://mbgips.in/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- BGCI. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Available online: https://tools.bgci.org/garden.php?id=4195 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- MSSBG. Wild Food Species Garden—MSSBG. Available online: https://mssbg.mssrf.org/attractions/wild-food-species-garden/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Manoj, E.M. Botanical Garden to Keep Biodiversity Safe. The Hindu 2018. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/botanical-garden-to-keep-biodiversity-safe/article22423424.ece (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- BSI. Northern Regional Centre, Dehradun. Available online: https://bsi.gov.in/rc-page/en?rcu=131,72 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- AMU. Department of Botany, AMU. Available online: https://amu.ac.in/department/botany (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- BGCI. Aligarh Muslim University Botanic Garden. Available online: https://tools.bgci.org/garden.php?id=922?id=922 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- BGCI. National Orchidarium and Experimental Garden. Available online: https://tools.bgci.org/garden.php?id=878?id=878 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- BGCI. Kerala University Botanic Garden. Available online: https://tools.bgci.org/garden.php?id=2290?id=2290 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Calicut University Botanical Garden. Calicut University Botanical Garden (CUBG). Available online: https://www.uoc.ac.in/index.php/about-botanical-garden (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- SFRI. State Forest Research Institute, Department of Environment & Forests, Government of Arunachal Pradesh. Available online: http://www.sfri.nic.in/tipi.htm (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- NBPGR. Issapur Farm, Division of Germplasm Evaluation. Available online: http://www.nbpgr.ernet.in/Issapur_Farm.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- BSI Garden. Available online: https://bsi.gov.in/bsi-garden/en?rcu=140 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Botanical Survey of India. Nature 1891, 44, 347–348. [CrossRef][Green Version]

- BSI Brief History. Available online: https://bsi.gov.in/page/en/brief-history (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- ENVIS Centre, Ministry of Environment & Forest, Govternment of India. Available online: http://bsienvis.nic.in/Content/ENVISCentreonFloralDiversity_3929.aspx?format=Print (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Smith, M.L. How ancient agriculturalists managed yield fluctuations through crop selection and reliance on wild plants: An example from Central India. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCC. African Orphan Crops Consortium—Healthy Africa through Nutritious, Diverse and Local Food Crops. Available online: http://africanorphancrops.org/ (accessed on 19 July 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).