Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) has various clinical presentations; pulmonary TB (PTB) affects only the lungs, whereas extrapulmonary TB involves other organs, including pleural TB (PLTB). Immunological studies of patients with extrapulmonary TB primarily focus on the cellular Th1 response, which produces key cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF, IL-12, and IL-6. TNF and IL-6 play functional roles in host resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. Findings suggest that TNF facilitates macrophage containment of Mtb, whereas IL-6 increases macrophage apoptosis induced by Mtb. Studies of the human genome have identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding cytokines associated with TB susceptibility. This study aimed to assess the potential of the IL6-174G/C (rs1800795), TNF-308G/A (rs1800629), and TNF-238G/A (rs361525) SNPs as genetic biomarkers of susceptibility to PLTB in the Venezuelan mestizo population. A total of 269 individuals were included: 69 patients with PLTB and 200 healthy individuals. The IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms were determined by sequence-specific primer polymerase chain reaction (SSP-PCR). Results showed significantly higher frequencies of the G/C, G/A, and G/A genotypes in patients with PLTB (94.0%, 94.2%, and 83.3%) than in controls (40.0%, 19.0%, and 13.4%) for the IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms, respectively. Logistic regression analysis showed significant associations between the G/C, G/A, and G/A genotypes and susceptibility to PLTB. The IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A gene polymorphisms may serve as genetic biomarkers of susceptibility to PLTB in the Venezuelan mestizo population.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious infectious disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). The World Health Organization (WHO) 2024 Global TB Report highlights the resurgence of TB as the leading infectious killer, posing significant threats to public health [1,2]. Globally, TB has been declared one of the world’s leading infectious killers. For the first time in a decade, cases increased as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, 10.6 million people worldwide fell ill with TB, and 1.3 million died. TB has reclaimed its position as a leading killer after falling behind shortly to COVID-19 and is followed by acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [3].

The complexity of TB stems from the interaction of multiple factors that sustain this endemic disease, most notably poverty, social inequities, the impact of the HIV pandemic, and a limited understanding of key risk factors such as genetic and immunological factors. Among people infected with Mtb, only 5–10% develop active TB. The remaining 90–95% have latent TB (LTB) and are typically asymptomatic, as their immune systems contain the bacteria [4]. TB has different clinical presentations. Pulmonary TB (PTB) affects only the lungs. In contrast, miliary TB (MTB) is a disseminated form of the disease, while pleural TB (PLTB) is a localized disease that affects the pleura [5,6].

The incidence of PLTB varies between countries. It is estimated to account for up to 30% of TB clinical presentations and is classified as an extrapulmonary form. Most cases are accompanied by tuberculous pleural effusion, with an incidence of 4–23%. A high proportion of these patients (65%) will develop other extrapulmonary manifestations within 5 years if the condition is not appropriately treated [7]. In the pathogenesis of TB, the host’s cellular immune response determines whether the infection is arrested as a latent or persistent infection or progresses to active TB disease [7]. Efficient cell-mediated immunity hinders a TB infection by permanently arresting it at a latent or persistent stage. This process prevents bacterial replication within cells, increases the phagocytic activity of macrophages, and allows them to eliminate (or contain) the bacteria successfully. However, if the initial lung infection is not controlled or the immune system is weakened, the disease can progress. Therefore, genetic variants in molecules involved in innate host defense mechanisms are expected to be associated with host susceptibility to TB [7]. Pleural TB is uncommon in young children and is more frequently reported in adolescents and adults. In young patients under 35 years of age from high-TB-prevalence areas, an elevated ADA value (a marker of lymphocytic activity) has a high positive predictive value for diagnosing PLTB. Another useful inflammatory biomarker is IFN-γ, as both ADA and IFN-γ are released in the pleural space during the immune response to Mtb antigens [8].

The regulation and balance of immunity are significantly affected by various mechanisms that Mtb has acquired throughout its evolution to escape the immune response and survive within host cells. To control TB, a Th1-type cellular immune response is required, which involves the participation of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, particularly γδ T lymphocytes, and the production of key cytokines [9,10]. The immune response to TB is regulated by interactions between lymphocytes, antigen-presenting cells, and the cytokines they secrete. Upon infection, phagocytes are activated to produce proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-12 (IL-12). IL-12, in particular, drives T cells and natural killer (NK) cells to produce T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which then activate infected macrophages to eliminate Mtb [9,10].

Antigenic stimulation of T cells in the presence of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, and costimulatory molecules induces IL-2 secretion. The binding of IL-2 to its receptor triggers the clonal expansion of antigen-specific T cells, an enhanced secretion of cytokines, and the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules. Additionally, IL-6 secreted by macrophages is known to stimulate early IFN-γ production [11]. In this context, cytokines play a pivotal role in the anti-mycobacterial response and can determine the type of TB. Genetic polymorphism studies of cytokines have shown that polymorphisms in the promoter or coding regions of many cytokine genes can influence transcriptional levels. These genetic variants have been associated with both susceptibility to and disease severity, including latent and active Mtb infections [12,13,14,15,16,17]. As proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and TNF are related to the pathogenesis of many chronic inflammatory diseases, including TB [15]. IL-6 and TNF likely play multiple roles in TB. It is known to block interferon (IFN)-γ- mediated signaling and to downregulate IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) expression in CD4+ T cells, which is associated with T helper cell depletion [15,18].

Studies of the human genome have identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in many genes that encode immune proteins, which are associated with susceptibility to TB [14,15,16,19]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the potential of the IL6-174G/C (rs1800795), TNF-308G/A (rs1800629), and TNF-238G/A (rs361525) polymorphisms as biomarkers for susceptibility to pleural tuberculosis in the Venezuelan mestizo population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Groups

A descriptive, cross-sectional, retrospective, association (case–control) study included a total of 269 patients classified into two groups: Group 1: Patients with active M. tuberculosis infection and symptoms compatible with PLTB (n = 69) based on the criteria above [20]. Group 2: Healthy individuals (n = 200). The average age was 41.6 ± 20.0 and 47.6 ± 12.2 for PLTB and controls, respectively. The sex ratio (male/female) was 62.3/37.7 in the PLTB group and 37.5/62.5 in the control group. The study group consisted of diagnosed cases of PLTB or with TB pleural effusion, whereas the non-TB effusion formed the control group. All the patients were HIV negative. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and individual controls before blood and pleural effusion samples were collected. The study of patients with TB pleural effusion (PLTB) was included in Project FONACIT No. 2023PGP319. All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Biomedicine Institute “Dr. Jacinto Convit” of the Central University of Venezuela.

2.2. Diagnosis of Tuberculous Pleural Effusions and Therapeutic Conduct

The PLTB diagnostic methods included imaging (chest X-rays), samples of pleural effusions, which were subjected to cytological, microbiological (including mycobacteriological) culture (Lowenstein–Jensen culture), and the determination of enzymes, like adenosine deaminase (ADA) assays. For molecular diagnosis, the endpoint polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is used. All patients included in the study underwent thoracentesis for diagnostic purposes by the Department of Pneumonology at the Vargas Hospital of Caracas. The pleural fluid aspirate was subjected to cytological examination, microbiological culture, and cytokine assays. Pleural biopsy was performed only when results of staining for acid-fast bacillus (smear) or culture of pleural fluid for Mtb. were negative. The PLTB was diagnosed using one of the following criteria as suggested in the national program of TB [21]: (1) M. tuberculosis isolated from pleural effusion by culture; (2) pleural biopsy showing granulomatous inflammation together with stainable acid-fast bacilli; (3) pleural biopsy showing granulomatous inflammation but no stainable acid-fast bacilli, together with a sputum culture positive for Mtb or a good radiographic response to anti-tuberculous treatment; (4) no histological or bacteriological confirmation, but with other likely alternative diagnoses excluded, together with a good clinical and radiographic response to anti-tuberculous treatment. The latter was initiated in all identified cases of PLTB, in which microbiological evidence suggestive of TB and bacteriological confirmation by bacilloscopy or culture were obtained. Clinical and nutritional follow-up occurred for six months after anti-TB drug treatment to evaluate the improvement of these aspects as therapeutic confirmation, permitting corroboration of the diagnosis. All PLTB patients were assessed for residual pleural scarring in thorax X-rays after completing anti-TB treatment.

2.3. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction, and IL-6 and TNF Genotyping

To determine the genotype frequencies of the IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A gene polymorphisms between PLTB patients and healthy controls, genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from peripheral blood samples collected before the initiation of anti-tuberculosis therapy. Briefly, 3 mL of whole blood obtained by venipuncture with EDTA as the anticoagulant was spun at 3000 rpm for 30 min; the resulting buffy coat containing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was stored at 4 °C for further use. A Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used to isolate DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was stored at −20 °C until use; a UV spectrophotometer was used to evaluate gDNA concentration and quality. For the IL-6-174G/C (rs1800795), TNF-308G/A (rs1800629), and TNF-238G/A (rs361525) single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were determined by sequence-specific primer polymerase chain reaction (SSP-PCR), using specific primers [22,23,24] (Table 1). The amplification products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gels stained with SYBR Green and examined under a transilluminator.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Genetic analyses to determine allele frequencies and to estimate the Hardy-Weinberg (H-W) equilibrium were performed using the SNPstats platform (Devel Version: 1.61.0, Bioconductor 3.21/3.23) [25]. Age was reported as mean ± standard deviation (X ± SD), given its normal distribution in the study population. Chi-squared, or Fisher’s exact tests, were used for examining age, male, and female sex differences among groups. Genetic analyses to determine genotypic frequencies and binomial logistic regression to evaluate associations between polymorphisms and TB risk, using adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with gender and age as potential confounders, were performed using the MedCalc Software Ltd. (version 17763.0, 8400 Ostend, Belgium). Odds Ratio Calculator and IBM SPSS Statistics 2025 (risk analysis Version 23.3.7).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

The study involved 269 individuals, 69 of whom were diagnosed as being infected by Mtb with pleural TB or PLTB based on the criteria above, and 200 were healthy individuals. Table 2 presents a comparison of demographic data between the study groups. There were statistically significant differences in percentage or distribution by gender between the patient and control groups; the comparison between male (62.3%) and female (37.7%) in the patient group was significant (p < 0.001). In the control group, a substantial proportion of participants was male (37.5%) compared with female (62.5%), p < 0.0007 (Table 2). Among patients, 66.6% were ADA-positive (>40 U/L), compared with 0% in controls (p < 0.0001). Chest X-rays were performed in all patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical information of the individuals enrolled in the study.

3.2. IL6 and TNF Polymorphisms and Allele Frequencies

The results for IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms showed a highly significant difference in allele frequencies between the patient and control groups (Table 3). The G allele for IL6-174, TNF-308, and TNF-238 was markedly overrepresented in the control group (80.0%, 88.4%, and 90.0%, respectively) compared with the patient group (50.0%, 53.0%, and 58.3%, respectively), with p-values <0.0001 (Table 3). Conversely, the C allele and A alleles predominated significantly in the patient group (50.0%, 47.1%, and 41.7%, respectively) compared with the controls (20.0%, 11.6%, and 10.1%, respectively), with p-values <0.0001 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Allele frequencies of IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A.

3.3. IL6 and TNF Polymorphism Genotypes and Association with Pleural Tuberculosis

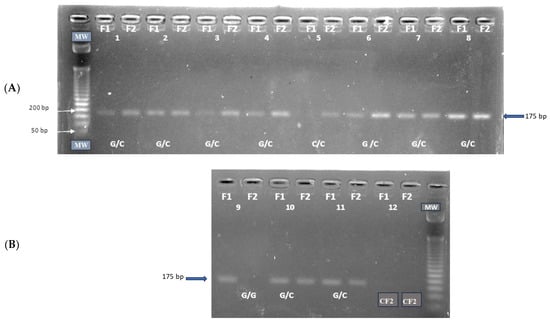

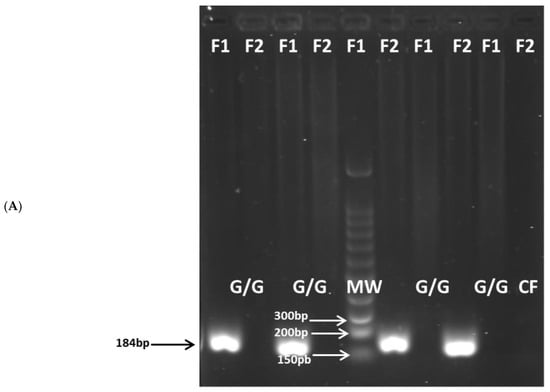

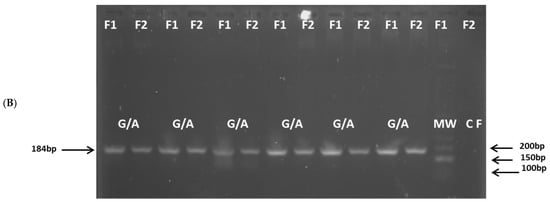

All gDNA was of high quality and purity. The amplified products for the IL6-174G/C (Figure 1), TNF-308G/A (Figure 2), and TNF-238 (Figure 3) gene polymorphisms were obtained at the expected molecular size.

Figure 1.

Amplification of the IL6 -174G/C (rs1800795) polymorphism: (A) G/C and C/C genotypes; (B) G/G and G/C genotypes. CF1: negative control forward primer F1, CF2: negative control forward primer F2, MW: molecular size marker, Amplicon size: 175 bp.

Figure 2.

Amplification of the TNF(-308G/A) (rs1800629) polymorphism: (A) G/G genotype; (B) G/A genotype. CF: negative control forward primer, MW: molecular size marker, Amplicon size: 184 bp.

Figure 3.

Amplification of the TNF(-238G/A) (rs361525) polymorphism: (A) G/G and G/A genotypes; (B) G/A and A/A genotypes. CF1: negative control forward primer F1, CF2: negative control forward primer F2, MW: molecular size marker, Amplicon size: 175 bp.

For IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms, the genotype frequencies results showed a highly significant prevalence of the heterozygous G/C, G/A, and G/A genotypes (94.0%, 94.2%, and 83.3%, respectively) in the patient group compared to the control group (40.0%, 19.0%, and 13.4%, respectively), p < 0.0001. The latter genotypes are associated with intermediate IL-6 and TNF production phenotypes. Conversely, the homozygous G/G, G/G, and G/G genotypes (associated with high IL-6 and TNF production phenotypes) were significantly more prevalent in the control group (59.5% for IL6-174, 78.8% for TNF-308, and 81.1% for TNF-238) than in the patient group (2.9%, 5.8%, and 16.6%, respectively), p < 0.0001. A similar low frequency of the homozygous C/C, A/A, and A/A genotypes (associated with low IL-6 and TNF production) was observed in both the patient group (2.9% for IL6-174, 0% for TNF-308, and 0% for TNF-238) and the control group (0.5%, 2.1% and 1.4%, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genotype frequency and logistic regression for modeling the relationship between the genotype and the risk of pleural tuberculosis.

Using SNPStats, the genotypic distribution of the polymorphism under study was found to be in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. After adjusting for sex and age using logistic regression (IBM SPSS STATISTICS 2025, Version 23.3.7); the analysis showed a significant association between the G/C genotype and susceptibility to PLTB for IL6-174G/C (OR: 48.343; 95% CI: 11.507–203.095; p < 0.0001) (Table 4), for TNF-308G/A (OR: 67.256; 95% CI: 22.993–196.729; p < 0.0001) (Table 4) and for TNF-238G/A (OR: 23.333; 95% CI: 9.282–58.655; p < 0.0001) (Table 4). Thus, logistic regression analysis of the association between IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A heterozygous genotypes and susceptibility to PLTB showed significant associations for the G/C, G/A, and G/A genotypes, respectively. In addition, although the majority of patients in the group were male, sex-adjusted association analyses indicate that the G/C IL-6-174 genotype and the G/A TNF-308 and TNF-238 genotypes were associated with the risk of developing pleural tuberculosis, regardless of sex (Table 5).

Table 5.

Gender groups were studied for the association between risk of pleural tuberculosis and IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms.

4. Discussion

Several reports indicate that the IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms may be associated with various infectious and inflammatory diseases. A functional cytokine network is a central element in maintaining the homeostasis of the immune system, and its alteration can lead to an abnormal immune response. Extensive immunological studies have been conducted to explain the various aspects of cytokine dynamics in patients with extrapulmonary TB. These studies primarily focus on the Th1-type cellular response, which produces cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF, IL-12, and IL-6. These cytokines are essential for the control of Mtb infection, due to their role in the activation and enhancement of macrophages, which will begin to synthesize reactive nitrogen species such as nitric oxide (NO) to reinforce phagocytic and microbicidal activity [26,27,28,29].

Genetic variants in the IL-6 gene have been linked to the susceptibility and severity of a wide range of diseases, including chronic hepatitis C and respiratory tract infections like tuberculosis [26]. Furthermore, IL-6 is associated with more severe TB, which includes greater radiological severity and impaired lung function. It also promotes Mtb growth and monocyte expansion following human hematopoietic stem-cell infection [27].

Increased serum TNF levels have been observed in several infectious diseases, including advanced TB [30]. The TNF gene, which encodes the cytokine TNF, is located within the class III region of the MHC. TNF is expressed as a transmembrane protein that can be processed into a soluble form (sTNF) that exerts its functions via two receptors, TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2 [30].

We found genetic variants in the TNF and IL-6 genes associated with TB susceptibility, specifically the SNPs rs1800795, rs1800629, and rs361525, in an analysis of allele and genotype frequencies between PLTB patients and controls. The present results suggest strong associations between the IL6-174G/C, TNF-308G/A, and TNF-238G/A polymorphisms and susceptibility to PLTB in the Venezuelan mestizo population. Our findings indicate that the heterozygous G/C genotype, associated with an intermediate IL-6 production phenotype, was significantly more prevalent among patients (94.0%) than among healthy controls (59.5%). Conversely, the homozygous G/G genotype was markedly overrepresented in the control group. This pattern of genotypic distribution, along with the allelic frequencies, suggests that the C allele is a risk factor for PLTB. In contrast, the G allele may confer a protective effect in the Venezuelan mestizo population. Furthermore, an analysis using the dominant inheritance model confirmed a significant association, indicating a higher risk of PLTB among individuals carrying the C allele. This finding underscores the potential of the IL6-174G/C polymorphism as a valuable genetic biomarker for susceptibility to this specific form of TB.

Importantly, the associations observed in this study should be interpreted in the context of tuberculosis-specific immune susceptibility rather than as genetic determinants of pleural effusion as a general clinical phenotype. Although pleural effusion may occur in several pathological conditions, including malignancies, the immunopathogenesis of tuberculous pleuritis is fundamentally different from that of malignant pleural effusions, which are primarily driven by tumor invasion, lymphatic obstruction, or cancer-related inflammation [5,6,7]. Polymorphisms in IL6 and TNF genes have been widely reported to modulate host immune responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, particularly macrophage activation, granuloma formation, and containment of infection, rather than directly promoting fluid accumulation [13,15,26,27,30]. Thus, altered cytokine production associated with these variants may impair effective immune control of M. tuberculosis, favoring extrapulmonary dissemination and pleural involvement in the setting of active TB infection [9,26,27,28,29]. Patients with pleural effusion of non-infectious origin, such as malignancy, were not included in this study, and therefore, the genetic associations reported here should not be extrapolated to pleural effusions unrelated to tuberculosis.

A meta-analysis by Liu et al. included 25 studies to investigate the relationship between IL6 and IL18 polymorphisms and tuberculosis susceptibility. To evaluate the role of IL6 polymorphisms, 14 papers were included. The rs1800795 polymorphism was significantly associated with TB in China (in a recessive model) and in Iran, Pakistan, and India (in dominant, recessive, and allele comparisons). The authors suggested that genetic polymorphisms of IL6 rs1800795 and IL18 rs187238 may increase susceptibility to TB, particularly in Asian populations [31]. Makhatadze et al. examined significant histocompatibility complex polymorphisms among Venezuelan mestizos. They reported that genes of Mongoloid, Negroid, and Caucasoid origin have contributed to a unique human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genetic profile in this hybrid population. This research highlights that the Venezuelan mestizo population is genetically distinct from Asian populations [32]. The Venezuelan mestizo population is highly admixed, with Mongoloid, Negroid, and Caucasoid ancestry, which explains the presence of heterozygous GC individuals. Thus, genetic admixture may contribute to differences in susceptibility patterns compared to monomorphic populations.

Graça et al. reported findings on cytokine genetic polymorphisms in 245 patients with clinical TB from Belém, Pará, Brazil. Of these patients, 82% had the pulmonary form and 18% had the extrapulmonary form of the disease. The study found that the wild-type GG genotype and the G allele of the IL6-174G/C polymorphism were associated with a fourfold increased risk of TB infection and disease development compared with healthy controls. The GG and CC genotypes were associated with higher and lower cytokine levels, respectively. The presence of the CC genotype was therefore associated with a lower risk of TB. However, the same authors reported a contrasting study from India in which the CC genotype was associated with a higher risk of the disease [33].

Most studies on the IL6 polymorphism have reported a relationship primarily with susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. However, a recent study by Silva et al. demonstrated a significant association between IL6-174G/C and TB risk, including cases of extrapulmonary TB, in a Brazilian population. Silva et al. reported their findings based on the IL6-174 G > C SNP in patients from northeastern Brazil. They observed that the heterozygous GC genotype predominated among patients with PTB. In contrast, the homozygous GG genotype was significantly more frequent among those with miliary TB, a form of extrapulmonary TB [34]. This contrasts with our findings in the Venezuelan mestizo population. While the GC genotype was associated with PTB in the Brazilian study, our research found the same genotype to be associated with pleural tuberculosis, a form of extrapulmonary TB. This suggests that the specific genetic association of the IL6-174G/C polymorphism may vary across populations and even among clinical forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Evidence suggests that the TNF-α gene is associated with the development of TB [30]. However, there are controversial studies regarding the association of the -308 TNF genotypes. Correa et al. (2004 and 2005) found an association between the -308 TNF G/G genotype and TB and concluded that the A/A genotype was a protective factor against TB [35,36]. In contrast, other authors observed an increase in A/A -308 TNF in PTB and chronic TB compared with controls [35,36]. However, the most substantial evidence of a protective role of TNF in human TB is the high incidence of TB reactivation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with monoclonal antibodies against TNF [37].

Our findings on the TNF-308G/A polymorphism indicate that the heterozygous G/A genotype, associated with an intermediate TNF production phenotype, was significantly more prevalent among patients (94.2%) than among healthy controls (19.0%). Conversely, the homozygous G/G genotype was markedly overrepresented in the control group (78.8% vs. 5.8%). This pattern of genotypic distribution, along with the allelic frequencies, suggests that the A allele is a risk factor for PLTB. In contrast, the G allele may confer a protective effect in the Venezuelan mestizo population. Regarding the TNF-238G/A polymorphism, the heterozygous G/A genotype, associated with an intermediate TNF production phenotype, was significantly more prevalent among patients (83.3%) than among healthy controls (13.4%). Conversely, the homozygous G/G genotype was markedly overrepresented in the control group (81.1% vs. 16.6%). This pattern of genotypic distribution, along with the allelic frequencies, suggests that the A allele is a risk factor for PLTB. In contrast, the G allele may confer a protective effect in the Venezuelan mestizo population.

There are reports on the correlation between TNF-308 and TNF-238 gene polymorphisms and TB infection across different populations, but the results are inconsistent [30]. A comprehensive understanding of the relationship between IL6 and TNF polymorphisms and TB susceptibility requires data from diverse populations, as differences in results may reflect ethnic variation. Our results indicate that the IL6-174G/C (rs1800795), TNF-308G/A (rs1800629), and TNF-238G/A (rs361525) polymorphisms are interesting candidates to explain individual differences in susceptibility to extrapulmonary TB among the Venezuelan mestizo population. A broader analysis of the existing literature supports these findings. For instance, subgroup analyses based on ethnicity have found significant associations between the IL6-174G/C polymorphism and TB risk in Asian and Latino populations. In contrast, no significant association was observed in Caucasian populations. This strongly suggests that ancestral genetic factors have a considerable impact on TB risk [38,39]. Further supporting the role of ethnicity in TB pathogenesis, our studies on Warao indigenous and non-indigenous populations revealed a low incidence of pleural TB (PLTB) among the Warao people compared to non-indigenous populations. This is a notable finding, given the high incidence and prevalence of pulmonary TB (PTB) among Warao indigenous people. This observation suggests that genetic background may not only influence overall TB risk but also the specific clinical form the disease presents [40,41]. Ultimately, more studies are needed to investigate the precise mechanisms by which IL6 and TNF polymorphisms regulate IL-6 and TNF production and influence susceptibility to various forms of TB, particularly PLTB.

5. Conclusions

The present study has highlighted the genetic association of intermediate IL-6 and TNF production phenotypes, which may serve as genetic biomarkers to improve understanding of TB pathogenesis and to identify genetic and immunological risk factors for PLTB, regardless of gender. An allele frequency in which dominant models (GC + CC vs. GG; IL6-174G/C) and (GA + AA vs. GG; TNF-308G/A and TNF-238G/A) predominate indicates a greater probability of developing PLTB in the Venezuelan mestizo population.

Author Contributions

Z.A.: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing. J.H.d.W.: Data curation, molecular and ADA assays for the confirmatory diagnosis of pleural tuberculosis. M.F.-M.: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, supervision. D.S.: Polymorphism assays and molecular characterization. C.J.S.: Formal analysis. L.A.D.J.-G.: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing. J.E.L.-R.: Data curation. B.R.-S.: Investigation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the budget provided by the Fondo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (FONACIT) of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Project FONACIT No. 2023PGP319).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Biomedicine Institute “Dr. Jacinto Convit” of the Central University of Venezuela and approved on 4 March 2024 (Protocol No. 2023PGP319).

Informed Consent Statement

The Informed Consent was obtained from all patients and individual controls before blood and pleural effusion samples were collected.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude is extended to the patients and to the Tuberculosis Laboratory of the “Dr. Jacinto Convit” Institute of Biomedicine (UCV).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Castro, V.; Celiz, J. Tuberculosis: Una Vieja Enfermedad Conocida Que No Deja de Sorprendernos. 2017. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35362011/Tuberculosis_Una_Vieja_enfermedad_conocida_que_no_deja_de_sorprendernos (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2024-tuberculosis-resurges-as-top-infectious-disease-killer (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- MacNeil, A.; Glaziou, P.; Sismanidis, C.; Date, A.; Maloney, S.; Floyd, K. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis and progress toward meeting global targets—worldwide, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcel, J.M. Tuberculous Pleural Effusion. Lung 2009, 187, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.C.; Feller-Kopman, D.; Niederman, M.S.; Spiro, S.G. Year in review 2010: Tuberculosis, pleural diseases, respiratory infections. Respirology 2011, 16, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barssa, L.; Connors, W.J.A.; Fisher, D. Chapter 7: Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. Can. J. Resp. Crit. Care Sleep Med. 2022, 6, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, M.; Prakash-Nayak, O.; Murmu, M.; Ranjan-Partra, S.; Baa, M. Role of CBNAAT in Suspected Cases of Tubercular Pleural Effusion. J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2019, 18, 46–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreiro, L.; San Jose, E.; Valdes, L. Tuberculous pleural effusion. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2014, 50, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, Y.J.; Li, F.G.; Chang, X.J.; Zhang, T.H.; Wang, Z.T. Analysis of cytokine levers in pleural effusions of tuberculous pleurisy and tuberculous empyema. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 3068103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antas, P.; Borchert, J.; Ponte, C.; Lima, J.; Georg, I.; Bastos, M.; Trajman, A. Interleukin-6 and-27 as potential novel biomarkers for human pleural tuberculosis regardless of the immunological status. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, F.; Schurz, H.; Yates, T.A.; Gilchrist, J.J.; Möller, M.; Naranbhai, V.; Ghazal, P.; Timpson, N.J.; Tom Parks, T.; Pollara, G. Altered IL-6 signalling and risk of tuberculosis: A multi-ancestry mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.P.; Scanga, C.A.; Yu, K.; Scott, H.M.; Tanaka, K.E.; Tsangm, E.; Chih, T.M.; Flynn, J.L.; John, C.J. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha on host immune response in chronic persistent tuberculosis: Possible role for limiting pathology. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Adrian, T.B.; Leal-Montiel, J.; Fernández, G.; Valecillo, A. Role of cytokines and others factors involved in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. World J. Immunol. 2015, 5, 16–50. Available online: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2824/full/v5/i1/16.htm (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, P.; Alagarasu, K.; Harishankar, M.; Vidyarani, M.; Nisha-Rajeswari, D.; Narayanan, P.R. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and cytokine levels in pulmonary tuberculosis. Cytokine 2008, 43, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao, M.I.; Montes, C.; París, S.C.; García, L.F. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in Colombian patients with different clinical presentations of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2006, 86, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, Ö.; Musellim, B.; Ongen, G.; Topal-Sarıkaya, A. IL-10 and TNF Polymorphisms in tuberculosis. J. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 28, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varahram, M.; Farnia, P.; Javad-Nasir, M.; Afraei-Karahrudi, M.; Kazempour-Dizag, M.; Akbar-Velayati, A. Association of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Lineages with IFN-γ and TNF Gene Polymorphisms among Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patient. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 6, e2014015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilullah, S.A.; Harapan, H.; Hasan, N.A.; Winardi, W.; Ichsan, I.; Mulyadi, M. Host genome polymorphisms and tuberculosis infection: What we have to say? Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 2013, 63, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Larrea, C.; Giampietro, F.; Luna, J.; Singh, M.; de Waard, J.H.; Araujo, Z. Diagnosis accuracy of immunological methods in patients with tuberculous pleural effusion from Venezuela. Inves. Clin. 2011, 52, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- MPPS (Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Salud de Venezuela). 2016. Available online: http://www.minsalud.com (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Ambruzova, Z.; Mrazek, F.; Raida, L.; Jindra, P.; Vidan-Jeras, B.; Faber, E.; Pretnar, J.; Indrak, K.; Petrek, M. Association of IL6 and CCL2 gene polymorphisms with the outcome of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009, 44, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verjans, G.M.; Brinkman, B.M.N.; Van Doornik, C.E.M.; Kijlstra, A.; Verweij, C.L. Polymorphism of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) at position -308 in relation to ankylosing spondylitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994, 97, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, R.F.; Ana Cristina Biral, A.C.; Pancoto, J.A.T.; Donadi, E.A.; Texeira Mendes-Júnior, C. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha -238 and -308 as genetic markers of susceptibility to psoriasis and severity of the disease in a long-term follow-up Brazilian study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, X.; Guino, E.; Valls, J.; Iniesta, R.; Moreno, V. SNPStats: A web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1928–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Sun, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H. Advances in cytokine gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 10, e0094424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scriba, T.J.; Coussens, A.K.; Fletcher, H.A. Human Immunology of Tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas Santiago, B.; Vieyra Reyes, P.; Araujo, Z. Respuesta de inmunidad celular en la tuberculosis pulmonar. Revisión. Investig. Clín. 2005, 46, 391–412. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, Z.; Acosta, M.; Escobar, H.; Baños, R.; Fernández de Larrea, C.; Rivas Santiago, B. Respuesta inmunitaria en tuberculosis y el papel de los antígenos de secreción de Mycobacterium tuberculosis en la protección, patología y diagnóstico: Revisión. Investig. Clin. 2008, 49, 411–441. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Zhou, R.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Xiao, H. Association of the TNF-308, TNF-238 gene polymorphisms with risk of bone-joint and spinal tuberculosis: A meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20182217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Dai, X. The association of cytokine gene polymorphisms with tuberculosis susceptibility in several regional populations. Cytokine 2022, 156, 155915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhatadze, N.J.; Franco, M.T.; Layrisse, Z. HLA class I and class II allele and haplotype distribution in the Venezuelan population. Hum. Immunol. 1997, 55, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça-Amoras, E.S.; Gouvea-de Morais, T.; do Nascimento-Ferreira, R.; Monteiro-Gomes, S.T.; Martins-de Sousa, F.D.; Rosário-Vallinoto, A.C.; Freitas-Queiroz, M.A. Association of Cytokine Gene Polymorphisms and Their Impact on Active and Latent Tuberculosis in Brazil’s Amazon Region. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Luiz, R.D.S.; Alves-Campelo, T.; Soares-Silva, C.; de Lima-Nogueira, L.; de Oliveira- Sancho, S.; Alves-da Silva, A.K.; Cunha-Frota, C.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-beta in pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the State of Ceará, northeastern Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2025, 120, e240147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, P.; Gómez, L.; Anaya, J. Polimorfismo del TNF- alfa en autoinmunidad y tuberculosis. Biomedica 2004, 24, 43–51. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47867884_Polimorfismo_del_TNF-alfa_en_autoinmunidad_y_tuberculosis (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, P.; Gómez, L.; Cadena, J.; Anaya, J. Autoimmunity and tuberculosis. Opposite association with TNF polymorphism. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 219–224. Available online: https://www.jrheum.org/content/32/2/219.long (accessed on 5 May 2024). [PubMed]

- Casas, L.A.; Gómez Gutiérrez, A. Asociación de polimorfismos genéticos de FNT-α e IL-10, citocinas reguladoras de la respuesta inmune, en enfermedades infecciosas, alérgicas y autoinmunes. Infection 2008, 12, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, M.C.D. Bases genéticas de la susceptibilidad a enfermedades infecciosas humanas. Rev. Inst. Nac. Hyg. Rafael Rangel. INHRR 2007, 38, 43–54. Available online: http://ve.scielo.org › scielo › pid=S0798-04772007000 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Araujo, Z.; Camargo, M.; Moreno-Pérez, D.A.; Wide, A.; Pacheco, D.; Díaz-Arévalo, D.; Celis- Giraldo, C.T.; Salas, S.; de Waard, J.H.; Patarroyo, M.A. Differential NRAMP1gene’s D543N genotype frequency: Increased risk of contracting tuberculosis among Venezuelan populations. Hum. Immunol. 2023, 84, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, F.; de Waard, J.H.; Rivas-Santiago, B.; Enciso-Moreno, J.A.; Salgado, A.; Araujo, Z. In vitro levels of cytokines in response to purified protein derivative (PPD) antigen in a population with high prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis. Hum. Immunol. 2010, 71, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, Z.; Palacios, A.; Enciso-Moreno, L.; Lopez-Ramos, J.E.; Wide, A.; de Waard, J.H.; Rivas-Santiago, B.; Serrano, C.J.; Bastian-Hernandez, Y.; Castañeda-Delgado, J.E.; et al. Evaluation of the transcriptional immune biomarkers in peripheral blood from Warao indigenous associate with the infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.