Abstract

Successful implantation requires a finely regulated endometrial microenvironment during the window of implantation. Chronic endometritis, defined by plasma cell infiltration, and stromal senescence, indicated by p16 expression, represent separate but potentially interacting mechanisms associated with impaired endometrial receptivity. The relationship between these processes remains poorly understood. We aim to examine whether stromal senescence is associated with plasma cell density and clustering in the human endometrium during the implantation window. Forty mid-luteal (LH+7) endometrial biopsies were retrospectively analyzed and stratified into low-senescence (<0.5% stromal p16+ cells, n = 20) and high-senescence (>3.5%, n = 20) groups. Plasma cells were identified by immunohistochemistry for MUM1 and CD138 and quantified using HALO® software (version 3.4). Group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test and chi-squared analysis. CD138+ plasma cells were significantly more abundant in high-senescence endometria than in low-senescence controls (0.065 ± 0.10 vs. 0.014 ± 0.027 cells/mm2, p = 0.02). Only MUM1+ cells formed stromal clusters, which were more frequent in high-senescence samples (67% vs. 31%, p = 0.05). High endometrial stromal senescence during the implantation window is associated with increased plasma cell infiltration and clustering. This interplay may contribute to chronic endometritis and impaired receptivity, providing new insights into potential diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for reproductive failure.

1. Introduction

Successful embryo implantation requires a receptive endometrium, which is established during the mid-luteal phase, also known as the window of implantation [1,2]. During this period, stromal–epithelial interactions and immune cell regulation are tightly coordinated to allow trophoblast attachment and invasion [3]. Disturbances in the endometrial microenvironment can lead to impaired receptivity and implantation failure [4]. Endometrial receptivity depends not only on hormonal signaling but also on the local immune and cellular environment, including coordinated actions of uterine NK cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and regulatory T cells [5]. Dysregulation of this immunological balance may result in a pro-inflammatory endometrium, creating a hostile environment for implantation [6].

Chronic endometritis (CE) is increasingly recognized as a contributor to infertility and recurrent implantation failure. The histological hallmark of CE is the presence of plasma cells, most reliably detected by immunohistochemistry for CD138 (syndecan-1) [7,8,9] and MUM1 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1) [10,11]. Increased numbers of plasma cells and the formation of stromal plasma cell clusters have been linked to persistent endometrial inflammation and suboptimal implantation outcomes [12,13]. Recent studies have demonstrated that even mild, subclinical CE can alter endometrial receptivity related to implantation and local immune tolerance [14]. CE often coexists with abnormal cytokine production, increased vascularization, and stromal remodeling, suggesting that it may contribute to a chronic inflammatory state in the endometrium [15].

In parallel, cellular senescence has emerged as an important biological process in reproductive biology. Senescent cells accumulate in the endometrium with age and pathological states and are commonly identified by expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a [16,17]. Endometrial stromal senescence has been associated with altered tissue remodeling, inflammation, and impaired receptivity [18,19]. Several studies proposed that premature or excessive decidual senescence in the stromal compartment impairs decidual transformation, leading to implantation failure and pregnancy loss [3,19,20,21]. This concept links senescence not merely to aging but to aberrant tissue responses under stress and inflammation. Moreover, the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) may sustain a pro-inflammatory microenvironment [22], potentially facilitating plasma cell recruitment or persistence. Our group has contributed to this field by demonstrating that a decreased number of epithelial p16-positive cells in the endometrium is associated with miscarriage, highlighting their potential role as markers of reproductive success [23]. More recently, we reported that stromal senescent cells are spatially associated with immune cell localization in women with repeated implantation failure, suggesting that there is an active interplay between endometrial senescence and immune microenvironment [24].

These findings emphasize that senescent cells are not only passive markers but also active regulators of endometrial receptivity and immune homeostasis. However, whether stromal senescence contributes to, or results from, endometrial inflammation remains unclear. Investigating the potential link between stromal senescence and plasma cell infiltration could help clarify mechanisms underlying chronic endometritis and reproductive failure. Taken together, they raise the possibility of a mechanistic link between stromal senescence and plasma cell infiltration. However, the relationship between senescence and plasma cell clustering during the window of implantation has not yet been addressed.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to compare the density and clustering of plasma cells in endometrial stroma with low versus high levels of p16-defined senescence during the window of implantation.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nadezhda Women’s Health Hospital (approval number 45/07 December 2020). All participants provided written informed consent for the use of their samples for research purposes.

2.1. Study Population

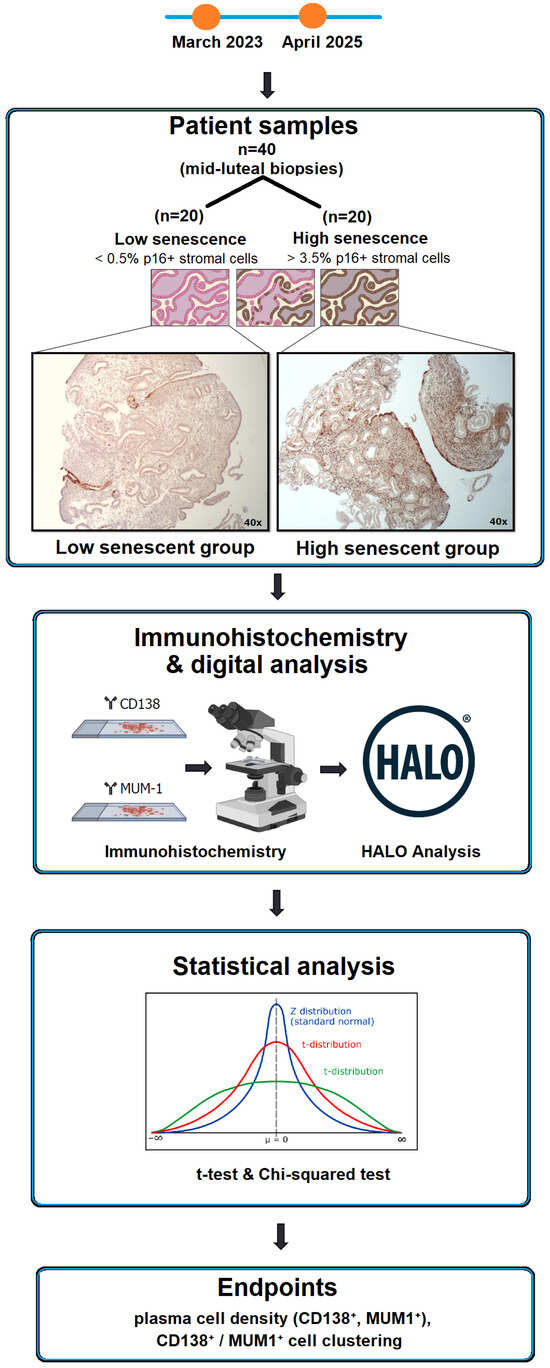

This retrospective study included forty endometrial samples obtained from the tissue bank of Nadezhda Women’s Health Hospital (Sofia, Bulgaria) between March 2023 and April 2025 (Figure 1). Biopsies were collected during the mid-luteal phase (LH+7) of unstimulated cycles, corresponding to the implantation window, which represents the period of maximal endometrial receptivity and physiological immune activation. This specific time point was chosen to ensure comparable hormonal and cellular conditions across samples. None of the patients were receiving hormonal treatment at the time of biopsy. Based on previous immunohistochemical assessment of stromal senescence, twenty samples with a low percentage of p16-positive stromal cells (<0.5%) were classified as the low-senescence group, and twenty samples with a high percentage (>3.5%) as the high-senescence group. Clinical and demographic data were anonymized before analysis. The mean ± SD age of patients was 35.8 ± 4.9 years in the low-senescence group and 36.1 ± 5.2 years in the high-senescence group (p = 0.79). All women were diagnosed with unexplained infertility and had no systemic inflammatory or autoimmune conditions.

Figure 1.

Study design and workflow. Schematic overview of sample grouping, immunohistochemistry workflow, digital image analysis, and statistical evaluation. Arrows indicate the sequential steps of the workflow.

2.2. Tissue Collection and Preparation

Endometrial biopsies were immersed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at 4 °C for overnight fixation, followed by dehydration and paraffin embedding according to routine histopathological procedures. Serial sections of 4 μm thickness were prepared from paraffin blocks and mounted on X-tra adhesive microscopic slides (3800200E, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) for subsequent immunohistochemical analysis.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using the Novolink Polymer Detection System (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), as previously described [18]. Sections were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against human p16^INK4a^ (Ready-to-Use, clone MX007, MAD-000690QD-7, Master Diagnostica, Granada, Spain) to identify stromal senescent cells. Plasma cells were detected by a rabbit monoclonal antibody against MUM1 (Ready-to-Use, clone MUM1p IR64461-2, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against CD138 (Ready-to-Use, clone MI15, IR64261-2, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Standard antigen retrieval and detection protocols were applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included in each staining batch.

2.4. Image Analysis

Immunopositive cells were quantified using HALO image analysis software (version 3.4, Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM, USA). The density of senescent cells (p16+), MUM1+ and CD138+ plasma cells was expressed as the number of positive cells per mm2 stromal tissue. Clusters were defined as stromal regions containing three or more MUM1+ cells located within a 45 μm radius, identified using the HALO Nearest Neighbor v2.1 algorithm.

The algorithm calculated pairwise intercellular distances and applied a spatial density threshold (kernel radius = 45 μm; minimum cluster size = 3 cells) to delineate high-density areas. Heatmaps were generated using the HALO Density Map module (version 2.1, Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM, USA) with adaptive kernel smoothing and automatic color scaling (blue = low, red = high cell density) to visualize gradients of local plasma-cell accumulation. All image annotations and quantitative outputs were independently verified by two observers to ensure reproducibility.

2.5. Sample Size and Power Analysis

Sample size was determined a priori based on our pilot data. Power calculations were performed in R (v4.4.x, package pwr), indicating that a minimum of 20 samples per group provided sufficient statistical power to detect the expected differences in plasma cell density and MUM1+ cluster occurrence between low- and high-senescence groups at α = 0.05.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were compared between groups with the independent-samples Student t-test. Categorical variables, including the frequency of cluster occurrence, were compared using the chi-squared test. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Presence of Plasma Cells in the Endometrium

Stromal plasma cells were identified by immunohistochemistry for CD138 and MUM1. Across all 40 endometrial biopsies, the mean density of CD138+ cells was 0.08 ± 0.14 cells/mm2, whereas the mean density of MUM1+ cells was 0.43 ± 0.38 cells/mm2 (Figure 2A). Representative staining patterns are shown in Figure 2B,C. CD138+ cells were typically scattered within the stroma, while MUM1+ cells were occasionally observed in small aggregates.

Figure 2.

The overall presence of plasma cells in the endometrial stroma. (A) Mean densities of CD138+ and MUM1+ stromal cells (cells/mm2) in all patients. Black dots represent individual patient values; horizontal lines indicate mean values. (B) Representative image of CD138+ plasma cells (arrows). (C) Representative image of MUM1+ plasma cells (arrows). Images at 100× magnification.

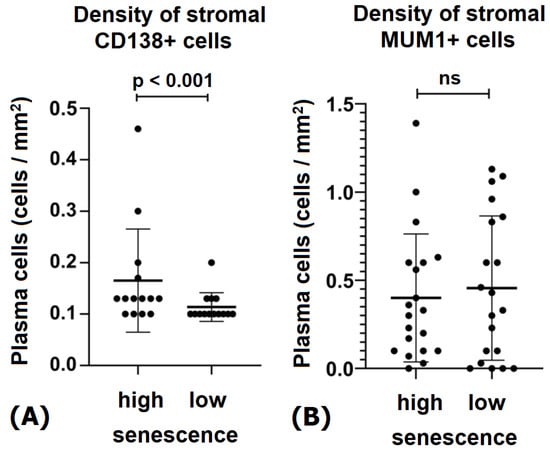

3.2. Plasma Cell Density in Low- and High-Senescence Groups

The mean number of stromal CD138+ plasma cells was significantly higher in endometrial biopses with high senescence compared with those with low senescence (0.065 ± 0.10 vs. 0.014 ± 0.027 cells/mm2, p = 0.02) (Figure 3A). In contrast, the density of MUM1+ plasma cells did not differ significantly between the groups (0.36 ± 0.25 vs. 0.35 ± 0.29 cells/mm2, p > 0.05) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The density of plasma cells in endometrial stroma with low and high senescence. (A) Density of CD138+ plasma cells (cells/mm2). Data are presented as mean ± SD. (B) Density of MUM1+ plasma cells (cells/mm2). Black dots represent individual patient values; horizontal lines indicate mean values; “ns” denotes non-significant differences.

Although the overall MUM1+ cell density did not differ significantly between groups, their spatial aggregation into compact clusters was markedly increased in high-senescence endometria. This qualitative difference prompted further analysis of plasma cell clustering, described below.

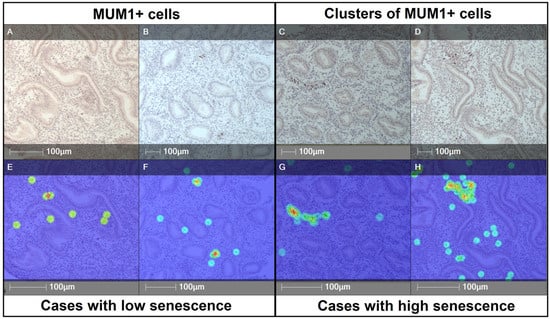

3.3. Plasma Cell Clustering and Spatial Distribution

MUM1+ cells, but not CD138+ cells, demonstrated the tendency to form clusters within the stromal compartment. These clusters were observed predominantly in perivascular and periglandular regions. The frequency of cluster occurrence was significantly higher in high-senescence endometria compared with low-senescence controls (67% vs. 31%, p = 0.05). The maximum local density of MUM1+ clusters reached 7130 cells/mm2, while CD138+ cells remained scattered individually throughout the stroma (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The distribution and clustering of plasma cells in the endometrial stroma. (A) Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD138+ plasma cells showing scattered individual stromal cells (arrows). (B) Representative staining for MUM1+ plasma cells demonstrating their ability to form stromal clusters (circled areas, arrows). (C) Higher magnification of a MUM1+ cluster indicating typical dimensions (~45 μm). Images taken at 40×, 100×, and 200× magnification as indicated.

To further characterize their spatial organization, HALO® heatmap analysis was applied. Endometria with low stromal senescence (<0.5% p16+ cells) showed only sparse MUM1+ plasma cells without evidence of aggregation, resulting in diffuse and low-density patterns. In contrast, high-senescence cases (>3.5% p16+ cells) displayed compact and locally enriched MUM1+ clusters, visualized as focal hot-spots of cell density on heatmaps. These spatial differences illustrate how stromal senescence is associated not only with higher plasma cell presence but also with their reorganization into dense stromal aggregates (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Representative immunohistochemistry and heatmap analysis of MUM1+ plasma cells in endometrial stroma with low and high senescence. (A,B,E,F) Cases with low stromal senescence (<0.5% p16+ cells) showing sparse distribution of MUM1+ plasma cells without evidence of clustering. (C,D,G,H) Cases with high stromal senescence (>3.5% p16+ cells) demonstrating increased density and formation of compact MUM1+ cell clusters. Panels (A–D): immunohistochemical staining; panels (E–H): corresponding HALO®-generated heatmaps highlighting areas of high local cell density. Heatmap colors represent local cell density (blue = low, green/yellow = intermediate, red = high). Scale bars = 100 μm.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that stromal senescence during the implantation window is associated with an increased presence of CD138+ plasma cells and a higher frequency of MUM1+ cell clusters in the human endometrium. These findings extend previous knowledge on the role of chronic endometritis and senescence in reproductive dysfunction by providing evidence for a potential link between stromal senescent cells and plasma cell infiltration.

Chronic endometritis (CE) has been recognized as an underdiagnosed condition that impairs endometrial receptivity and contributes to infertility and recurrent implantation failure [25,26,27,28]. During the window of implantation, some of the characteristic hysteroscopic indicators of CE, such as hyperemia with a “strawberry pattern,” mucosal edema, and polypoid areas, may be subtle or obscured [29,30]. Likewise, spindle-cell transformation, stromal vascularization, and the presence of lymphoplasmacytoid infiltrates are often difficult to discern microscopically at this stage. These macro- and microscopic features are more easily identifiable during the proliferative phase; however, the gold standard for diagnosing CE in both proliferative and secretory endometrium remains the demonstration of plasma cells within the stromal compartment [28]. The diagnostic hallmark of CE is the presence of plasma cells, most reliably detected by CD138 and MUM1 immunohistochemistry [7,31,32]. CD138 and MUM1 largely label overlapping plasma-cell populations [7,10,32]. However, MUM1 is a nuclear marker of late B-cell differentiation and can occasionally be expressed in activated T cells [10]. This partial overlap explains minor discrepancies between CD138+ and MUM1+ cell counts and supports the use of both markers for accurate identification of plasma cells in chronic endometritis. We prefer the combined use of both markers because CD138 staining may occasionally produce diffuse, artifactually intense background labeling that can hinder the identification of true plasma cells, whereas MUM1 provides a cleaner nuclear signal but can also be expressed in activated T lymphocytes. Thus, the application of both markers in our study not only confirms the diagnosis of CE but also raises interesting questions regarding the potential involvement of T lymphocytes in chronic inflammatory conditions of the endometrium. Our findings confirm this diagnostic approach and further suggest that high levels of stromal senescence correlate with greater CD138+ plasma cell density and more frequent MUM1+ clusters. While the overall density of MUM1+ cells was not increased, their organization into clusters in high-senescence samples highlights a qualitative feature of CE that may be clinically relevant.

Cellular senescence is increasingly viewed as a driver of tissue dysfunction due to the SASP, which includes cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and TGF-β [22,33,34]. In the endometrium, stromal senescent cells accumulate under pathological conditions and impair receptivity [18,35,36]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β can accelerate stromal senescence and interfere with decidualization [37], while IL-17 signaling has also been implicated in senescence induction [38].

Our group has previously shown that a decreased number of epithelial p16+ cells in the endometrium is associated with miscarriage [23] and that stromal senescent cells are spatially associated with immune cell infiltration in women with repeated implantation failure [24]. Together with the current data, these findings reinforce the concept that senescence is not only a marker of impaired receptivity but also an active modulator of the endometrial immune microenvironment.

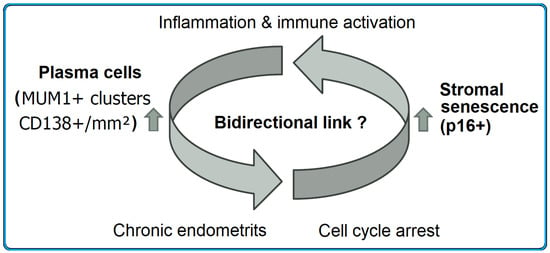

The interplay between stromal senescence and plasma cells may be bidirectional. On the one hand, SASP factors could facilitate plasma cell accumulation by sustaining a chronic inflammatory condition [22,39,40]. On the other hand, persistent inflammation and CE could induce stromal senescence, creating a vicious cycle [19,37,38]. Multi-omic analyses have also supported a link between cell aging, chronic inflammation and reproductive disorders [41]. This reciprocal interaction is conceptually illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The hypothetical interplay between stromal senescence and plasma cell infiltration in the endometrium. Arrows indicate the proposed bidirectional relationship between stromal senescence and chronic inflammatory plasma cell accumulation.

Senescent stromal cells may promote a pro-inflammatory environment through the SASP, thereby supporting plasma cell accumulation and cluster formation. Conversely, chronic endometritis and persistent immune activation may induce senescence and cell cycle arrest in stromal cells, establishing a potential vicious cycle.

The identification of stromal senescence as a correlate of plasma cell infiltration suggests potential diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The application of p16 biomarker, combined with plasma cell markers, may improve CE diagnosis in women with unexplained infertility or implantation failure. Targeting senescent cells or modulating their SASP activity is being explored in other fields [42,43] and could represent a novel therapeutic avenue in reproductive medicine. However, our study was not designed to assess implantation or pregnancy outcomes, and the direct clinical significance of stromal senescence–plasma cell interactions remains to be validated. The proposed therapeutic considerations should therefore be viewed as hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive, pending confirmation in larger, prospective clinical studies.

The relatively small cohort size and the retrospective design represent limitations of this study, despite adequate statistical power for the comparisons performed. Although the sample size was sufficient for detecting group differences, the limited cohort restricts the generalizability of the findings. Larger, prospectively collected, multi-center studies are warranted to confirm these results. Furthermore, the exclusive reliance on immunohistochemistry and image analysis without functional assays restricts mechanistic interpretation. As an observational immunohistochemical study, our results reveal associations rather than causative relationships. Future investigations combining cytokine profiling, single-cell transcriptomics, and co-culture models of stromal and immune cells, together with larger, prospectively collected cohorts, would be valuable to mechanistically assess senescence–plasma cell interactions and to validate these findings. In addition, the application of multiplex immunofluorescence or flow cytometric validation could further improve cell-type resolution and confirm co-expression patterns of plasma cell markers such as CD138 and MUM1. Finally, because all biopsies were obtained at a single time point (LH+7), our findings provide a cross-sectional snapshot of the implantation window. Longitudinal sampling across the menstrual cycle would be necessary to determine temporal dynamics and causal relationships between stromal senescence and immune cell infiltration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P., D.M., S.H. and G.S.; methodology, D.P. and N.V.; validation, D.P. and D.M.; formal analysis, D.P.; investigation, D.P., D.M., M.H., J.S. and L.J.; resources, D.P.; data curation, D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P., D.M., R.G. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, D.P., D.M., R.G., M.R., S.H. and G.S.; visualization, D.P.; supervision, S.H. and G.S.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the European Union-NextGenerationEU through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No. BG-RRP-2.004-0004-C01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee of Nadezhda Women’s Health Hospital (project code 45/07 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Chronic endometritis |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| p16^INK4a^ (p16) | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 4A |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| HALO | Digital image analysis software (Indica Labs) |

References

- Koot, Y.E.; Teklenburg, G.; Salker, M.S.; Brosens, J.J.; Macklon, N.S. Molecular aspects of implantation failure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 1943–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessey, B.A.; Young, S.L. Homeostasis imbalance in the endometrium of women with implantation defects: The role of estrogen and progesterone. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2014, 32, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellersen, B.; Brosens, J.J. Cyclic decidualization of the human endometrium in reproductive health and failure. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 851–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volovsky, M.; Seifer, D.B. Current status of ovarian and endometrial biomarkers in predicting ART outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, M.; Lee, S.K. Role of endometrial immune cells in implantation. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2011, 38, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, S.A.; Moldenhauer, L.M.; Green, E.S.; Care, A.S.; Hull, M.L. Immune determinants of endometrial receptivity: A biological perspective. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 117, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer-Garner, I.B.; Korourian, S. Plasma cells in chronic endometritis are easily identified with syndecan-1. Mod. Pathol. 2001, 14, 877–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ughade, P.A.; Shrivastava, D. Unveiling the role of endometrial CD138: A comprehensive review on its significance in infertility and early pregnancy. Cureus 2024, 16, e54782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, M.; You, G.; Lian, R.; Huang, C.; et al. The effect of the number of endometrial CD138+ cells on the pregnancy outcomes of infertile patients in the proliferative phase. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15, 1437781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, E.; Haimovich, S.; De Ziegler, D.; Raz, N.; Ben-Tzur, D.; Andrisani, A.; Ambrosini, G.; Picardi, N.; Cataldo, V.; Balzani, M.; et al. MUM-1 immunohistochemistry has high accuracy and reliability in the diagnosis of chronic endometritis: A multi-centre comparative study with CD-138 immunostaining. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Travaglino, A.; Inzani, F.; Angelico, G.; Raffone, A.; Maruotti, G.M.; Straccia, P.; Arciuolo, D.; Castri, F.; D’Alessandris, N.; et al. The role of plasma cells as a marker of chronic endometritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, M. Correlation of hysteroscopic findings of chronic endometritis with CD138 immunohistochemistry and their correlation with pregnancy outcomes. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024, 41, 2477–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Golde, R.; Van Haren, A.; Stevens, L.; Brentjens, S.; Sofia, X.; Bert, D.; Servaas, M. Higher incidence of CD138+ cells indicating chronic endometritis in patients with recurrent implantation failure. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, deaf097.755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, S.; Huang, C.; Lian, R.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Diao, L.; Markert, U.R.; Zeng, Y. Evaluation of peripheral and uterine immune status of chronic endometritis in patients with recurrent reproductive failure. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 187–196.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Li, Q.; Chen, Q. Uterine NK cell polarization associates with chronic endometritis and predisposition to recurrent implantation failure. Int. J. Womens Health 2025, 17, 4255–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.G.; Krizhanovsky, V. Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 4373–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safwan-Zaiter, H.; Wagner, N.; Wagner, K.D. P16INK4A—More than a senescence marker. Life 2022, 12, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomari, H.; Kawamura, T.; Asanoma, K.; Egashira, K.; Kawamura, K.; Honjo, K.; Nagata, Y.; Kato, K. Contribution of senescence in human endometrial stromal cells during proliferative phase to embryo receptivity. Biol. Reprod. 2020, 103, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryabin, P.; Griukova, A.; Nikolsky, N.; Borodkina, A. The link between endometrial stromal cell senescence and decidualization in female fertility: The art of balance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.S.; Vrljicak, P.; Muter, J.; Diniz-da-Costa, M.M.; Brighton, P.J.; Kong, C.S.; Lipecki, J.; Fishwick, K.J.; Odendaal, J.; Ewington, L.J.; et al. Recurrent pregnancy loss is associated with a pro-senescent decidual response during the peri-implantation window. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, T.M.; Makwana, K.; Taylor, D.M.; Molè, M.A.; Fishwick, K.J.; Tryfonos, M.; Odendaal, J.; Hawkes, A.; Zernicka-Goetz, M.; Hartshorne, G.M.; et al. Modelling the impact of decidual senescence on embryo implantation in human endometrial assembloids. eLife 2021, 10, e69603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J.P.; Desprez, P.Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: The dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvanov, D.; Ganeva, R.; Vidolova, N.; Stamenov, G. Decreased number of p16-positive senescent cells in human endometrium as a marker of miscarriage. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvanov, D.; Ganeva, R.; Arsov, K.; Decheva, I.; Handzhiyska, M.; Ruseva, M.; Vidolova, N.; Scarpellini, F.; Metodiev, D.; Stamenov, G. Association between endometrial senescent cells and immune cells in women with repeated implantation failure. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaya, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Mizuta, S.; Matsubayashi, H.; Ishikawa, T. Chronic endometritis: Potential cause of infertility and obstetric and neonatal complications. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 75, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Abbasi, H.; Salehpour, S.; Saharkhiz, N.; Nemati, M. Prevalence of chronic endometritis in infertile women undergoing hysteroscopy and its association with intrauterine abnormalities: A cross-sectional study. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2024, 28, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Meng, S.; Tu, X.; Wang, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; He, W. Analysis of the risk factors of chronic endometritis in infertile women. BMC Womens Health 2025, 25, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Jiao, J.; Wang, X. The pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic endometritis: A comprehensive review. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1603570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, E.; Resta, L.; Nicoletti, R.; Tartagni, M.; Marinaccio, M.; Bulletti, C.; Colafiglio, G. Detection of chronic endometritis at fluid hysteroscopy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2005, 12, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouet, P.E.; El Hachem, H.; Monceau, E.; Gariépy, G.; Kadoch, I.; Sylvestre, C. Chronic endometritis in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and recurrent implantation failure: Prevalence and role of office hysteroscopy and immunohistochemistry in diagnosis. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fang, R.; Luo, Y.; Luo, C. Analysis of the diagnostic value of CD138 for chronic endometritis, the risk factors for the pathogenesis of chronic endometritis and the effect of chronic endometritis on pregnancy: A cohort study. BMC Womens Health 2016, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Qin, P.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Q. The combination of CD138/MUM1 dual-staining and artificial intelligence for plasma cell counting in the diagnosis of chronic endometritis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 89, e13671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, J.; Gil, J. Senescence and the SASP: Many therapeutic avenues. Genes. Dev. 2020, 34, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; Demaria, M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brighton, P.J.; Maruyama, Y.; Fishwick, K.; Vrljicak, P.; Tewary, S.; Fujihara, R.; Muter, J.; Lucas, E.S.; Yamada, T.; Woods, L.; et al. Clearance of senescent decidual cells by uterine natural killer cells in cycling human endometrium. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemerinski, A.; Garcia de Paredes, J.; Blackledge, K.; Douglas, N.C.; Morelli, S.S. Mechanisms of endometrial aging: Lessons from natural conceptions and assisted reproductive technology cycles. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1332946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.N.; Berga, S.L.; Zou, E.; Washington, J.; Song, S.; Marzullo, B.J.; Bagchi, I.C.; Bagchi, M.K.; Yu, J. Interleukin-1β induces and accelerates human endometrial stromal cell senescence and impairs decidualization via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, K.; Matsumura, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Araki, H.; Hamada, N.; Kuramoto, K.; Yagi, H.; Onoyama, I.; Asanoma, K.; Kato, K. Endometrial senescence is mediated by interleukin-17 receptor B signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.; Alqahtani, T.; Venkatesan, K.; Sivadasan, D.; Ahmed, R.; Sirag, N.; Elfadil, H.; Mohamed, H.A.; T.A., H.; Elsayed Ahmed, R.; et al. SASP modulation for cellular rejuvenation and tissue homeostasis: Therapeutic strategies and molecular insights. Cells 2025, 14, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, N. The roles and mechanisms of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): Can it be controlled by senolysis? Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yi, Y.; Nie, J. Multi-omic insight into the involvement of cell aging related genes in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delenko, J.; Hyman, N.; Chatterjee, P.K.; Safaric Tepes, P.; Shih, A.J.; Xue, X.; Gurney, J.; Baker, A.G.; Wei, C.; Munoz Espin, D.; et al. Targeting cellular senescence to enhance human endometrial stromal cell decidualization and inhibit their migration. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Xie, F.; Lee, L.M.Y.; Lin, Z.; Tu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Yu, P.; Wu, J.; Chen, B.; Zhang, G.; et al. Cellular senescence in cancer: From mechanism paradoxes to precision therapeutics. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.