Abstract

Background: Social media has become a space for sharing personal experiences and shaping public opinion. This study explored how people respond to substance misuse recovery journeys shared on TikTok. Methods: The researchers collected 3583 comments from 350 TikTok videos under the hashtags #wedorecover, #recovery, and #sobertok using a scraper tool. A discourse analysis categorized comments into Narrative Strategies, Rhetorical Strategies, Linguistic Features, and Power Relationships, each with subcategories revealing public perceptions of substance use and recovery. A correlation analysis was also conducted to examine the role of emojis across narrative and linguistic features. Results: Most comments (94%) expressed support or positivity toward recovery videos. The heart emoji was the most common (93.35% of all emojis), symbolizing connection, encouragement, and solidarity. Four themes emerged reflecting public attitudes: encouragement and positive messaging, acknowledgment of struggle, the culture of sharing, and the influence of broader social narratives. Conclusions: These results provide insight into public responses to recovery content on TikTok, suggesting that peer support may be facilitated through the platform’s algorithmic design. While TikTok shows promise as a supportive digital space, further research is needed to understand its broader implications for substance use recovery support.

1. Introduction

Substance use often provokes a polarized discussion in the public sphere. The term “substance” encompasses a wide range: alcohol, tobacco, nicotine, cannabis, and illicit drugs. In the United States, among people aged 12 or older, 59.8% were defined as “current substance users” in 2022, while 17.3% had a substance use disorder (SUD) [1]. In Canada, 13% of people aged 15 and older have exceeded the “acute effects” guideline for alcohol use, and 1.4 million people reported using cannabis daily in 2019 [2]. In addition to personal cost attributable to substance use, there is also a significant financial strain on Canada’s public healthcare system. In 2020, healthcare costs attributable to substance use were $13.4 billion [3].

Certain substances, such as alcohol and tobacco, when consumed responsibly and in moderation, may be viewed as socially conventional due to their prevalent use. However, it is essential to acknowledge that what may be considered ‘moderate’ consumption for some individuals might still be harmful to others, depending on their individual sensitivities and health conditions. For this study, substance misuse is defined as individuals identifying adverse effects on their quality of life due to substance use. Specifically, the individuals perceive that their substance use significantly hinders their ability to engage in meaningful daily activities and/or maintain relationships. We align this with the established definition of substance misuse as the use of alcohol, illegal drugs, or over-the-counter or prescription medications in a way that they are not meant to be used and could be harmful to the user or others [4]. We chose this term, rather than substance abuse or substance use disorder, to reflect both harmful patterns of use and perceived consequences, while avoiding stigmatizing language. The purpose of this study is to examine public attitudes toward substance misuse as reflected on social media among English-speaking populations in Western culture.

1.1. Recovery and Substance Misuse

Because recovery from substance misuse involves a deeper transformation related to lifestyle, social, and interpersonal aspects, “recovery” is often viewed as an ongoing process [5]. Recovery is unique to each person; therefore, it is essential to acknowledge that there is no single, universal definition of recovery in this context. Worley (2017) defines recovery as a process in which a person experiences not only changes in substance use but also improvements in personal and social elements of their lives [6]. In this regard, Worley notes that individuals should be seen as being in a state of ongoing “recovery” rather than already “recovered” from a substance use disorder; this perspective allows recovery to be viewed as a complex, yet comprehensive, process of enhancing wellness in personal and social areas and overall quality of life. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2023) provides a recovery model, stating that recovery is “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential” [1]. SAMHSA emphasizes that recovery is supported through peers, allies, and social networks, which offer hope, support, and encouragement, as well as strategies and resources for change. In this study, such an understanding of recovery will inform our perspective on narratives of substance misuse recovery.

1.2. Public Attitude Towards Substance Misuse

A Canadian Census conducted in British Columbia between February and March 2023 surveyed individuals aged 18 about public opinion on substance use. The census found that 88% of Canadians want their friends or family members who use drugs to feel comfortable talking to them about it, and 81% show empathy for people struggling with substance use. Additionally, 62% believe that decriminalization would improve access to health and social services, while 51% think it would increase risks associated with substance use, including overdoses [7]. The public attitude toward substance misuse reflects a balance of support and empathy, combined with cautious views on the broader implications of decriminalization. However, a study by Cunningham & Koski-Jännes (2019) in Canada, covering the years 2008 to 2018, revealed increasing public concern regarding the seriousness of substance misuse and its associated risks [8]. Despite the legalization of some substances such as cannabis, the study found minimal alleviation of negative perceptions regarding substance misuse.

Substance misuse remains heavily stigmatized in public perception [9]. Stigma—a negative and often presumptive set of beliefs or attitudes directed toward a person or group—is socially constructed through language and meaning-making processes [10]. Language shapes how society views and responds to individuals with substance use disorder (SUD), influencing perceptions, behaviours, and treatment approaches [10]. The semantics of language not only help individuals interpret the world but also reinforce stigmatizing narratives by creating schemas that define reality. These linguistic frameworks influence the quality of support and care that people with SUD receive, thereby impacting their recovery journeys. Internalized stigma can lead to low self-esteem, diminished self-efficacy, and feelings of shame or embarrassment among individuals with SUD [9,11]. Research indicates that stigma negatively impacts help-seeking behaviour and serves as a barrier to community integration [12]. Furthermore, societal prejudice often portrays substance misuse in punitive terms, pushing individuals with SUD to the margins of society [13]. It is therefore critical to examine how societal attitudes and responses can either facilitate or hinder recovery.

1.3. The Influence of Social Media and Substance Misuse

Social media has become a powerful force, shaping nearly every aspect of people’s daily lives—from communication and personal identity to broader societal norms. Russell et al. (2021) argue that digital recovery narratives not only facilitate discussions around substance misuse but also promote help-seeking behaviours [14]. Public online spaces can play a meaningful role in supporting recovery. For example, approximately 73.6% of individuals in outpatient addiction treatment programs report having at least one social media account, with 76.1% engaging with these platforms daily [15]. Exposure to personal stories of substance use and recovery can foster new recovery pathways and encourage behavioural change [14]. Similarly, platforms like YouTube offer opportunities for peer support by enabling individuals with severe mental illness to share their experiences and connect with others [16]. Bliuc et al. (2017) further demonstrate that online engagement in recovery forums can support recovery by helping individuals build “recovery capital”—a set of social and personal resources critical to maintaining recovery—and reduce self-stigma. Their findings show that positive online interactions, particularly within supportive communities, promote identity transformation and group belonging, both of which are associated with sustained engagement in recovery programs [17]. Building on this foundation, the present study explores how social media can serve as a resource for individuals navigating substance misuse and mental health challenges. As technology becomes increasingly integrated into healthcare, understanding its role and impact is crucial for both providers and policymakers.

1.4. Purpose of This Study

While existing research has explored both social media use and the stigma surrounding substance misuse, limited attention has been given to public attitudes toward recovery narratives shared on social platforms. This study focuses on TikTok—a platform that curates highly engaging content through user interaction algorithms—to examine how recovery stories are received by the public. Specifically, it investigates how audience responses and interactions may foster a sense of support and reciprocity, encouraging others to share their own experiences. The research also considers the broader implications of social media engagement on mental health and substance misuse, assessing both potential benefits and risks in a digital context. The central research question guiding this study is: What are the public’s attitudes and reactions towards substance use recovery on TikTok?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Critical Discourse Analysis

In this study, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is used to explore, interpret, and discuss the relationship between language and the social context within which it is used [18]. CDA offers a useful lens for examining how power, ideology, and identity are constructed and maintained through discourse—particularly in public forums such as social media. In the context of this study, CDA provided a guiding framework for analyzing how TikTok users respond to recovery-related content, with attention to the ideologies and social norms embedded in their language. Drawing from CDA principles and prior discourse analysis literature, we organized the data into four analytic domains: narrative structures, rhetorical strategies, linguistic features, and power relationships. Narrative structure refers to the way in which comments are written to construct a specific perspective, and rhetorical strategies identify the approach the author takes to persuade readers of their intended effect. Linguistic features focus on specific language choices such as emojis or tone markers, and power relationships assess the implied dynamics between commenters and content creators [18]. These domains enabled a structured analysis of how recovery discourse is shaped, supported, or challenged in the TikTok environment.

2.2. Search Generation and Data Collection

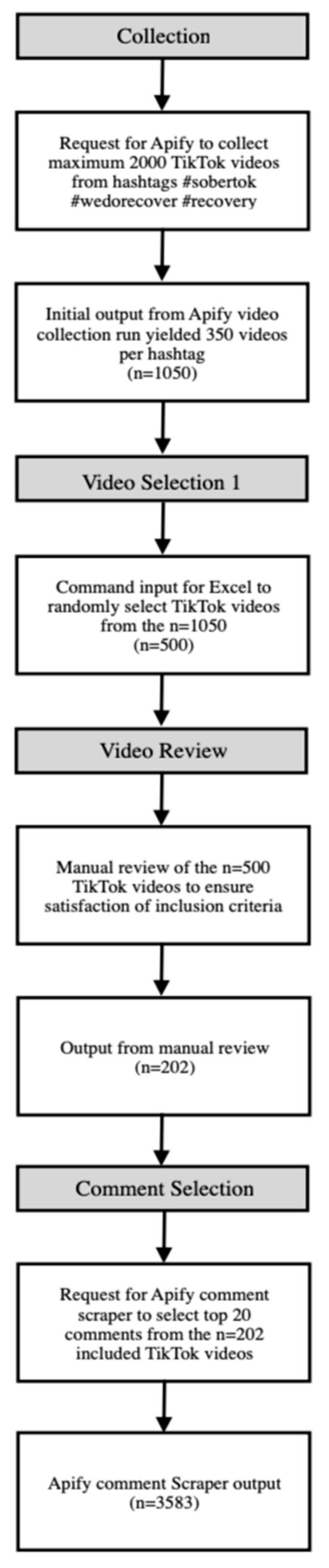

The Apify TikTok scraper tool [19] was first used to collect a random sample of TikTok videos within the search criteria. The request input for the initial video scrape included the hashtags #sobertok, #wedorecover, and #recovery. These hashtags were determined to be the most relevant through a preliminary, informal TikTok search by the researchers. The initial video scrape was conducted on 12 February 2024 and produced 1050 videos, 350 videos per hashtag. The 1050 video URLs collected were then exported into an Excel file, and a shortlist of 500 video URLs was randomly selected from the data pool. The Excel random function was used to assign a number to each URL, and then each URL was subsequently ordered from smallest to largest. The first 500 of these were selected for manual verification. The 500 videos were divided among the three researchers and manually verified to ensure they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria before being selected for the final dataset. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) video caption included at least one of the following hashtags: #wedorecover #sobertok #recovery; (2) videos with at least one comment; (3) videos in English; and (4) videos contained an aspect of a substance use recovery journey personal to the speaker, including comparison photos, talking about recovery journey (i.e., vlog style, self-recording), sober curious, videos celebrating number of days sober, comedic interpretations of recovery journey, and songs about recovery journey. The exclusion criteria were: (1) videos not in English; (2) videos with comments turned off; (3) comedic videos not exclusively sharing personal recovery journey; (4) videos on non-substance-related recovery stories; and (5) videos focusing on product advertisements related to substance (e.g., non-alcoholic wine). Two hundred and two chosen videos were then put through an Apify TikTok Comments Scraper [20], where the top 20 comments of each video were scraped on 21 February 2024. In this context, “top” refers to the first 20 comments returned by the scraper, which mirrors TikTok’s default comment display order. This ordering is generally influenced by a combination of factors, including the number of likes and the time of posting, although TikTok’s exact algorithm is not publicly available. This resulted in 3583 comments. See Figure 1 for the data extraction procedure.

Figure 1.

Data extraction procedure.

2.3. Qualitative Analysis

Out of a total of 1050 videos, randomly selected by Apify using the three hashtags #sobertok, #wedorecover, and #recovery, 3583 comments (the top 20 comments per video) were equally split amongst the three researchers to manually review. Prior to coding, the three researchers independently reviewed and coded a subset of comments to calibrate their understanding of the analytic framework and to refine the coding scheme collaboratively. After reaching consensus, each researcher proceeded to code approximately one-third of the dataset. Regular meetings were held to discuss uncertainties, ensure consistency, and align interpretations across the four categories of discourse analysis: Narrative Strategies, Linguistic Features, Rhetorical Strategies, and Power Relationships [21,22]. Ambiguous or complex comments were discussed with the senior researcher (project supervisor) to mitigate potential bias and enhance analytic rigour.

- Narrative Strategies: This category aimed to dissect the underlying connotations of the included comments. Through an analytical breakdown of the included comments, the intention was directed toward understanding the public’s overall perception of substance use and/or their reaction toward shared recovery stories.

- Rhetorical Strategies: This category within discourse analysis aims to identify the key strategies used by commenters on TikTok to convey their viewpoint or influence readers’ perceptions of their message. Such literary devices may include appeals to emotion (pathos), logic (logos), or credibility (ethos).

- Linguistic Features: This category describes the specific word selections and terms used by commenters, and can help create links between common themes as well as provide an indication of the perspective taken by the commenter.

- Power Relationships: This category was included to investigate the presence of power disparities between the original creator and the commenters. Researchers aimed to evaluate the language used within a comment and describe what the nature of the interaction was for the commenter towards the video creator.

2.4. Emoji Co-Occurrence Analysis

After all 3583 comments were coded and categorized according to the discourse analysis framework, we conducted an exploratory co-occurrence analysis to examine how emojis were used across different narrative and rhetorical categories. Emojis were selected for this analysis because they represent a visually distinctive and quantifiable linguistic feature that appears frequently in social media discourse, particularly on TikTok. Emojis function as nonverbal cues that can reinforce, soften, or shift the tone of a message, making them especially relevant for understanding how sentiment and solidarity are expressed in this context. We identified the most frequently used emojis within the dataset and calculated how often each appeared in comments associated with each coded category. These frequencies were compiled into a summary table. This analysis was descriptive and intended to identify patterns in emoji use as a form of affective expression. The goal was to explore how emoji usage might reflect or reinforce the tone and function of comments within the broader discourse on recovery.

3. Results

The 3583 comments were examined using discourse analysis. Within the four categories (narrative strategies, rhetorical strategies, linguistic features, and power relationships), subcategories were established to better understand the nature of the comments for a more in-depth view of the public’s perception of recovery and substance use. Table A1 offers a detailed qualitative breakdown of these categories, along with their respective frequencies.

3.1. Narrative Strategies

Four narrative strategies were identified that reveal the underlying tones of the comments and highlight the social ideologies surrounding substance use (see Appendix A for the definitions of narrative strategies). Of the 3583 comments analyzed, 54.9% were categorized as Supportive Towards Recovery, 4.2% as Unsupportive Towards Recovery, 3.7% as Negative Towards Substance Use, and 33.7% as Sharing. These strategies help assess whether TikTok, as a platform, facilitates, discourages, or remains neutral toward naturally occurring peer support for substance misuse recovery. The four narrative strategies are:

3.1.1. Supportive Towards Recovery (54.9%)

Over half of the comments showed positivity towards the original poster’s recovery journey or overall recovery from substance misuse. This positive sentiment was identified through linguistic features such as exclamation points, emojis expressing support or positivity, and words of encouragement. For example, “Still so impressed with your attitude and very proud of your daily journey…”; “I am soooo proud of you!! You DID THAT. and survived. ❤️”; and “Talk about a GLOW UP!! congratulations!! you got this!! keep breaking your records!!”

3.1.2. Sharing (33.7%)

This category includes comments that share strategies, stories, knowledge, and/or tag others. Shared strategies involve resources and/or personal methods they have encountered or used themselves. For example, “you gotta remember your hobbies from 7–10 yrs old and start doing them again trust me”. Shared stories typically come from commenters’ personal experiences and histories that create relatability to the relevant TikTok, such as “my therapist once said anxiety is just disorganized motivation & when i think of it like that it helps me use it to my advantage”. Sharing knowledge often involves comments that include facts about a specific substance, milestones of recovery for certain substances, biological reactions during recovery processes from a particular substance, and other related facts related to substance use, misuse, or recovery. Tagging others involves tagging other TikTok users with the goal of sharing the video and increasing the audience for that specific TikTok.

3.1.3. Unsupportive Towards Recovery (4.2%)

Comments categorized here contained content that was more apathetic in their response to recovery journeys but did not show hostility towards shared content. This category was further divided into the subcategories Indifferent Towards Recovery (2.3%) and Pro-Substance (2.0%). Comments labelled as Indifferent Towards Recovery were assessed based on the subtle messages they conveyed, often using linguistic features that expressed impassiveness or indifference towards the progress of someone’s shared recovery journey. For example, “high rn ☺️”; “‘that won’t solve your problems’ ‘yes it will’; and “Lmaooo if you don’t serve him someone else well that’s how I feel about selling Florida snow and me being addicted to it at one point”. This subcategory also includes comments that touched on other aspects of the TikTok video with a significant disregard for recovery or substance misuse.

Comments coded into the Pro-Substance category had shown overt support and encouragement for continued use of substances or insinuated a preference for continued use over experiencing the challenges related to recovery. For instance, comments such as “This is your sign to do it <3” suggested active encouragement; others, like “my mother tried to lock me up and it ruined my life i forgot how to socialize and when i got back out i did the same thing im not gonna stop” conveyed resistance to recovery efforts and a rejection of imposed intervention. Comment like “Sometimes we gotta try it out for ourselves” implied that personal experimentation with substances is necessary or valid, subtly undermining the idea of abstinence or structured recovery. Though relatively rare, these comments reflect a counter-narrative that challenges dominant recovery-oriented discourse on the platform.

3.1.4. Negative Towards Substance Use (3.7%)

A few comments contained content that conveyed hostility or patronization towards the original poster and/or their shared recovery journey. Subcategories included Shaming/Blaming, Stigma and Pitiful/Sympathetic. Within the Shaming/Blaming subcategory, comments expressed pointed malice towards the individual, their engagement with substance use, and presumed irresponsibility towards themselves and others. The following comments demonstrate the negative attitude: “It’s amazing how easy it is to come up with an excuse to drink”; “Oh pls. Everyone is faking illnesses because it seems cool in tiktok. It’s embarrassing to lie ab this”; “You should feel guilty”; and “You should have aborted it. My mom used while pregnant w me. I will never forgive her for it. Your kids probably never will either. Selfish addict”.

Within the subcategory of Stigma, comments included stereotypical presumptions about substance use or attributed it to social deviance. Comments mourning different aspects of the original poster’s life following their engagement with substances were included in the subcategory Pity/Sympathetic. This subcategory was included because of the power dynamics it suggests, particularly comments that expressed pity towards an individual, creating a dynamic of superiority and inferiority between the commentator and the substance user.

3.2. Rhetorical Strategies

Due to the short-form text (comments) and the influence of the colloquial nature of the language used on social media, the primary rhetorical strategies used by TikTok users included exclamations, capitalizations of entire words or sentences, emojis, and questions.

3.2.1. Exclamation (22.7%)

Exclamation marks were used to emphasize key points. A total of 813 comments that included at least one exclamation mark were used in an encouraging or positive manner towards recovery, such as “Proud of you!!!” and “Congratulations on 2 months of sobriety!!”.

3.2.2. Emojis (10.9%)

Out of 3583 comments, emojis appeared in 391 of them. The most common emoji was the heart emoji, found in 265 comments in various forms (e.g., ❤️,❣️, <3). These emoji variations typically show affection, care, or sympathy for the video creator. They were either part of larger comments or used alone as a supportive message, such as “If you’re struggling right now, I’m sending you so much love. We do recover ❤️”. The sparkle/star emoji (✨) appeared in 21 comments and generally did not carry a significant meaning. In these instances, the sparkle emoji was free of sarcastic or mocking tones, unlike some other social media contexts. The happy face emoji (e.g., :), 🙂) appeared in 19 comments and was used to express happiness or support, like “Proud of you king you’re amazing:)”. The snowflake emoji (❄️) showed up 18 times, often as a substitute for the word cocaine, which could lead to content restrictions or removal. The sad face emoji (e.g., :(, 🙁) occurred in 14 comments, used to express sadness or empathy for difficult situations, such as “I’m so sorry:( alcoholism is scary wish young kids would realize”.

3.2.3. Capitalization (7.2%)

Aside from the standard practice of capitalizing the first letter of a sentence or proper noun, capitalization was used to highlight specific parts of a comment, such as a key word, or entire sentences. For example, “Look at that GLOW ✨️❇️” and “YOURE SO STRONG!!”.

3.2.4. Question (6.1%)

Comments in this section contained at least one question mark or were phrased as questions without punctuation. These comments aimed to ask questions either of the video creator, the general public reading the comments, or were rhetorical. Examples include: “How much drinking do you think is too much drinking ?” “I’m trying to figure out why I have such a hard time sleeping when I’m drinking? I’ll sleep really good for the first three or four hours and then not” and “3 weeks so far … any advice?”.

3.3. Linguistic Features

Four specific groups of terms, slang, and jargon were found to indicate particular perspectives regarding substance misuse and/or recovery journeys. These viewpoints contribute to an aggregated understanding of the public’s overall reaction to the sharing of recovery stories.

3.3.1. Encouragement (53.5%)

Comments within this category explicitly show support for the video creator sharing part of their recovery journey. Comments denoting encouragement were a significant portion of all comments analyzed, making up half of the total. Notably, the largest subcategory was comments including linguistic features that displayed peer status, such as “Ma’am, Queen, Girl, Sis, Brother, Man, King”. “Proud” and “Terms of encouragement” which included a variety of encouraging words (see Table A1 for examples) were also included in a significant portion of the comments. These terms did not necessarily require the commenter to personally relate to the video creator, but rather the general population also provided support and encouragement. Examples of encouragement include: “CONGRATULATIONS!!!! YOU GO GIRL YOU GET YOUR BEST LIFE” “Great job, it’s quite amazing. It’s not easy, but so rewarding. Proud of you” and “For anyone in recovery. No matter how far in you are, I’m so proud of you and you should be proud of yourself. I love you all and I believe in you ❤️”.

3.3.2. Identifying the Stage of Recovery (26.8%)

People use specific terms to express their definition and measurement of recovery. The terms “clean” and “sober/sobriety” were predominantly used to describe recovery; this signifies that recovery within the TikTok community is understood as abstinence from substances. This was further numerically measured by using numbers of days/months/year to disclose the amount of time someone has been on their recovery journey. For example, “Great job! 15 years clean for me! You got this!” and “Congrats❤️I’ve been sober for 18 years”.

In this regard, “addict/addiction/addicting” was also coded within this category to describe the nature of substance misuse; in other words, defining substance misuse as a compulsive, chronic, physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance. These two comments illustrate this feature: “so proud of you my bf is trying to overcome alcohol addiction. So many people say just stop they don’t understand how hard it is”. And “Can someone describe the pain? Why does the withdrawal cause it? I’ve never suffered from addiction. I’m so curious. Sorry”.

3.3.3. Challenges of Recovery (15.2%)

This group of terms presents overall challenges individuals face during substance misuse recovery, including both negative connotations linked to specific difficulties in recovery or substance misuse, as well as positive connotations linked to inspiration or positive examples for viewers/commenters. Terms with negative connotations predominantly included variations of “Brutal, Hard, Struggle, Horrible, Suffering” and “Relapse, Cycle, Cycling”. Such comments depicted either a sense of relatedness with the video creator or some form of general acknowledgment or validation of difficulties associated with recovery. For instance, “I’ve been struggling so much recently and this has me in tears. Some people don’t understand how brutal it is”.

Comments using terms with positive connotations included “Strong, Strength, Self-Control, Powerful”, “Inspiration, Motivation”, and “Hope”. These comments were largely represented by users sharing how the video creator has positively impacted them on their recovery journey or provided a positive example and inspiration to start their journey, like “YES!!!! Proud of you! Best thing I ever did. Keep being strong!”.

3.3.4. Community Hashtags/Slogans (1.5%)

Comments within this category were coded based on the usage of community-created hashtags, such as “We Do Recover” or “ODAAT/(One Day At A Time)”. Hashtags are a rhetorical tool that can be used to help users find related content under a phrase and bring communities together. These slogans were used predominantly in a supportive nature, such as, such as “good on you for sharing! addiction is hard, We Do Recover Together ❤️”and “Amazing! I got 6 months 2 days ago! We do recover! #ODAAT”.

3.4. Power Relationships

Two main subcategories were found. Most commenters were positioned as peers/same status, with an insignificant number falling within the condescending/ patronizing category.

3.4.1. Peer/Same Status (91.9%)

Comments in this category were coded based on the absence of inferior or superior attitudes from the commenter, with a greater emphasis on camaraderie, for example, “Well done brother so proud of you ❤️❤️” and “I’ve been down that alley … took me 10 years to get out … 6/5/14 we do recover ♡♡”.

3.4.2. Condescending/Patronizing (2.6%)

Comments in this category were classified based on the presence of negative, shaming, stigmatizing, or pitying tones. Comments that were condescending or patronizing often established a dynamic between the commenter and the content creator, positioning the commenter as morally superior to the individual sharing their recovery journey. The two comments—“Bro you didn’t drink for a month chill” and “‘We’ were healing? Bull crap. A son of an addict, you have no idea what you’ve done to your kids. There’s no healing for them. Smh”—exemplify this power imbalance. Table A1 displays the frequency of the data coded above.

3.5. Intersection Between Narrative Strategies and Linguistic Features

A correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between various emoticons and their appearance alongside Narrative Strategies and Linguistic Features. The five emoticons (❤️, ✨,🙂, 🙁, ❄️) were analyzed, revealing a variety of interactions between the established categories. It is important to note that emoticons can be expressed in multiple categories simultaneously. Table A2 provides a comprehensive breakdown of the correlation results.

Regarding narrative strategies, the heart emoji (❤️) is mainly used in supportive comments, with 250 instances, constituting 94.3% of total usage. It is the most commonly used emoticon, primarily paired with supportive comments that were used to uplift and encourage the context creator through their journey of recovery. For example, the comment “I’ve been clean for only 3 weeks … you got this❤️we got this” shows the utilization of the heart to foster a sense of connection, support, and encouragement. The sparkle emoji (✨) and smile emoji (🙂) also appear in supportive and encouraging settings, but less often.

For linguistic features, the heart emoji (❤️) occurs in 180 encouraging comments (67.9%), the sparkle emoji (✨) in 13 comments (57.1%), and the smile emoji (🙂) in 10 comments (52.6%). The hashtags category does not show any use of these emojis. The sad emoji (🙁) is mainly found in sharing and unsupportive comments, showing negative feelings. The snowflake emoji (❄️) is used sparingly in various contexts.

Integrating the results of the discourse analysis with the intersection between narrative strategies and linguistic features, four overarching themes emerged that capture the public’s attitudes and reactions toward substance use recovery on TikTok. These themes reflect a predominantly encouraging and positive tone, frequent acknowledgment of personal struggle and mutual empathy, a strong culture of sharing experiences and knowledge, and subtle traces of broader social narratives surrounding addiction and recovery. Together, they present a nuanced understanding of how recovery journeys are received, supported, and sometimes contested within this digital space.

3.6. Theme 1. Encouragement and Positive Messaging as Support

The results of this study reveal a high prevalence of messaging that expresses encouragement and support. This is demonstrated by the frequent use of the heart emoji and encouraging terms in the comments. For example, “I am soooo proud of you!! You DID THAT. and survived.❤️” and “The recovering community on TikTok has given me more motivation than anything irl”. The inclusion of these narrative and rhetorical strategies is interpreted as emphasising positive communication towards individuals sharing their recovery journeys.

Importantly, encouragement extended beyond simple praise, reflecting more nuanced understandings of substance use. Some comments recognized structural and contextual factors that influence substance use, as in: “Hi mama, as a 14 year old who’s seen her close family fall into addiction, I’m proud of you”. Here, intergenerational exposure and family dynamics shape the commenter’s understanding, situating substance use within broader social contexts such as trauma and family background. Such comments indicate that substance use is increasingly being framed within broader social contexts—acknowledging contextual influences and societal pressures—rather than solely as an individual moral failing.

3.7. Theme 2. Acknowledgment of Struggle

Within the comments, terms with negative connotations were often used to reflect the community’s acknowledgment of the difficulties related to substance misuse and recovery. This helps create a narrative that both validates and shows empathy for the challenges faced by individuals on their journey to recovery, for example, “Yayyyyyy I’m proud of you! It must be really hard and im glad you are on this way!” and “wow just reading these comments made me realize how many people actually experience this horrible experience. i’m so sorry to whoever has had to deal”.

Additionally, such recovery stories inspire others on their own journeys to share their struggles as well; this fosters a sense of community where the audience can find validation and empathy from the TikTok community through sharing their own challenges during recovery. For example, “I’ve been struggling so much recently and this has me in tears. Some people don’t understand how brutal it is” and “Congrats! 7 years sober but it’s still a struggle some days! Proud of you!” With the widespread presence of this linguistic feature across 545 comments, the data suggests that the challenges of one’s recovery journey are acknowledged and validated by their peers. Recognising these challenges may indicate a growing understanding of the complexities of substance misuse and the various barriers or difficulties faced during recovery.

3.8. Theme 3. The Culture of Sharing

We have observed a culture developing that shows vulnerability when someone shares their recovery journey. With about a third of all comments sharing personal stories and experiences in response to the original videos, it’s clear that many TikTok users aim to foster a recovery-positive environment by being vulnerable themselves. Like people shared: “This is high key what I’ve been doing this year. I had to stop drinking for mental health reasons. I’ll have a craft beer for the taste, but I have cut” Many other TikTok users chose to simply share their own recovery journey progress by posting their significant milestones or sober dates. These comments were prompted mainly by video creators sharing their own milestones or sober dates within their videos, such as “19 days no alcohol. Needed this today”; “38 days in recovery ❤️”; and “Exactly 10 years later omg. Stay clean for 3+ years now. Proud of you so much!!!❤️”.

Another aspect of the sharing culture within this TikTok community involves neutral commenters who seem genuinely curious about substance use recovery or other parts of the individual’s journey. Some appear to be individuals experiencing similar situations and show interest in the recovery process, often called “sober curious” on social media. These comments were mostly categorized as “Gaining Understanding of Misuse,” for example: “How much did you use and for how long? This is really informative and important for other people”.

3.9. Theme 4. Influence of Social Narrative

The presence of both supportive and unsupportive comments indicates that a power dynamic exists in social narratives. The majority of comments came from a position of peer status (91.1%) and were supportive towards recovery (55.0%). For example, “we’ll be here when you get out! can’t wait to hear updates and keep up the support when you’re all done! proud of you for taking this brave journey!” However, the existence of unsupportive comments suggests an ongoing struggle between positive reinforcement and stigmatization within the community, for example: “Are you employable? my guess no and never will be. Monumental drain on society. What made you become addicted… that was your decision in the 1st place”. The overwhelming amount of positive comments shows that recovery stories may be accepted within the TikTok community. However, existing stigma, bias, and pity show that those recovering from substance misuse may still reap the consequences of existing societal conceptions.

4. Discussion

This study examined the public’s attitudes and reactions to stories about substance use recovery shared on TikTok. Most comments were positive or supportive of recovery efforts and helped create an online space that encouraged peer support naturally. Many comments also showed vulnerability by sharing their own recovery experiences or those of someone close to them. A small number of comments were negative and unsupportive of substance use recovery.

4.1. TikTok as a Supportive Space

The majority of comments analyzed were supportive and positive, suggesting the presence of a generally encouraging subcommunity within the broader TikTok platform. However, an important consideration is the influence of TikTok’s algorithm on the visibility of content and the audience it reaches. The platform’s algorithm is known to prioritize factors such as user retention and time spent on the app [23], using a combination of indicators—including user engagement history and likely user demographics, such as age—to recommend videos. As a result, the search terms used in this study likely surfaced videos that aligned with content users are more inclined to engage with, potentially contributing to the predominance of positive feedback received by creators. Another factor to consider is the inherently subjective nature of interpreting online comments. While many comments had clearly positive or negative tones, the absence of nonverbal cues—such as facial expressions, vocal tone, or body language—means that interpretation can vary, introducing a degree of ambiguity to the analysis.

Our findings align with trends previously noted by Russell et al. (2021) [14], who analyzed popular TikTok videos and found that recovery-related content often centers on sharing personal journeys, celebrating milestones, and fostering a recovery-oriented identity. While their study focused on the content created by individuals in recovery, our analysis complements and extends this work by examining public responses to such content. Specifically, we found that the majority of comments were supportive, empathetic, or affirming, indicating that TikTok not only facilitates the dissemination of recovery narratives but also fosters an environment where those narratives are met with encouragement and solidarity. This provides a fuller picture of the platform’s potential role in shaping recovery discourse—not just through the stories told, but through the social engagement they generate.

Our results also suggest that online peer support can provide opportunities for users and viewers to disclose their feelings and views, contributing to a decreased sense of isolation. Conveying positivity and support among the active TikTok community offers encouraging effects for others to engage in a shared identity and interact with peers in ways that attract the collective aspiration of positive behaviour change.

A benefit of social media platforms is their increased accessibility, which differs from the traditional, more limited support group formats often organized in person at specific times and locations. It also provides a layer of anonymity for commenters, which can make sharing vulnerable experiences more enticing and less risky. Overall, the current landscape of the substance use recovery community provides data that indicates the promising possibility of using social media outlets such as TikTok as an alternative platform for unstructured peer support.

4.2. The Benefits of Algorithmic Influences on Stigma

Existing literature on public perceptions of substance misuse and recovery often highlights expectations of stigmatizing responses to personal narratives. However, our analysis revealed a lower prevalence of stigma and marginalization in comparison to the volume of supportive and encouraging comments. This more positive reception may reflect a broader cultural shift in how substance use and recovery are understood. Increased societal exposure to the complexities of substance misuse and recovery processes appears to foster deeper empathy and a move away from simplistic, moralizing judgments. Rather than framing substance use as a failure of personal character or strength, public discourse increasingly recognizes the structural and contextual factors that shape individual behaviour. Growing awareness of social justice issues and systemic inequalities—operating at both macro and meso levels—may be contributing to this shift in attitude [24]. In this context, the surge in supportive commentary on recovery stories can be interpreted as part of a changing social narrative that views unsanctioned behaviours like substance use through a more compassionate and justice-oriented lens.

It is also important to note that while positivity and encouragement showed the greatest occurrence among the comments, negative reactions and stigmatizing commentary were still present. The continued presence of negative comments or reactions to shared recovery stories suggests that society still holds negative views towards substance misuse. The prevalence of positive and encouraging commentary may be influenced by TikTok’s algorithm. A study by Karizat et al. (2021) indicates that algorithms actively filter and suppress certain social identities in response to users’ online behaviours such as liking, commenting, and sharing [25]. If users predominantly comment and interact with TikTok content that supports recovery and substance misuse, the algorithm is understood to tailor user exposure to similar sentiments, assuming the user adopts a social identity supportive of recovery. This could explain the overrepresentation of positive comments on the TikTok videos analysed in this study, as users with negative views on substance use and recovery stories might not be exposed to the same extent due to the algorithm’s operation. However, this does not disqualify TikTok as a platform capable of providing supportive mental health resources for individuals in recovery. Recognising the mechanisms behind TikTok’s algorithm, the filtering of opposing or negatively oriented content might be viewed as a positive feature of the platform that helps maintain a positive and productive online environment.

While algorithmic “echo chambers” are often discussed in negative terms—particularly in relation to political polarization or misinformation (e.g., Cinelli et al., 2021) [26]—in this context, personalization appears to foster a positive discursive environment. The algorithm may act as a gatekeeper, curating content and comments that align with recovery-supportive norms while minimizing exposure to stigmatizing or antagonistic viewpoints. This can be seen as a double-edged dynamic: on one hand, it creates a safer space where individuals in recovery can share their experiences without fear of shame or trolling—an important factor in mental health support and community-building. On the other hand, it may also mean that individuals who hold stigmatizing beliefs are absent or self-select out of these conversations, leaving their views unchallenged. Rather than directly confronting stigma, the platform enables a parallel discourse in which new norms flourish organically. This quiet but powerful shift aligns with Ghosh’s (2021) notion of a “quiet revolution,” wherein institutional or cultural change occurs not through confrontation but through the steady normalization of alternative values [27]. TikTok’s recovery community may represent one such grassroots transformation in how addiction and recovery are perceived in the public sphere.

4.3. Contrasting Definitions of Recovery

Recovery in mental health now is seen as a process, not a one-time event [28]. In healthcare, recovery-oriented practices are being incorporated into mental health models, where personal recovery—defined as a process of readjusting attitudes, feelings, perceptions, and beliefs about oneself, others, and life; involving discovery, self-renewal, and transformation—is emphasized [29]. This supports the restitution narrative, which focuses on transformation rather than just restoration during the recovery journey. In this context, recovery is understood as a non-linear, ongoing, and individual process influenced by biological, personal, and environmental factors [30]; this ultimately means each person’s recovery remains a unique journey, making it difficult to give a fixed definition.

However, in this study, TikTok users seem to have different views of substance use recovery. Linguistic features related to abstinence, such as “sober/ sobriety” and “clean”, were used alongside “__days/months/years” to clearly define and measure an individual’s recovery journey. This may indicate that the general public equates recovery with abstinence. As TikTok users describe their recovery journey by the amount of time since their last use, they may develop a more concrete understanding of recovery. When people continue to use this measure over long periods (e.g., 20 years sober), it aligns with the literature in that there is no fixed end goal or outcome; rather, using time as a measure reflects the ongoing journey they are still undertaking with abstinence and sobriety.

4.4. Implication

This study suggests that TikTok may serve as an informal, unstructured space for peer support around recovery, offering encouragement, shared experience, and a sense of community. While the platform is not a clinical environment, its algorithmic features appear to foster a positive recovery discourse, which could complement traditional support systems. However, the open and user-driven nature of TikTok also raises concerns about the potential spread of misinformation or exposure to triggering content. Future research could explore how mental health service providers might ethically engage with such spaces to amplify accurate, supportive narratives while remaining mindful of the platform’s limitations. These insights may also inform broader discussions about how digital platforms can be designed or guided to support mental health–related communities more intentionally.

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

Although this study has captured a variety of public reactions to substance use recovery journey videos on TikTok, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on the top 20 comments per video, as ranked by TikTok’s algorithm at the time of scraping. These rankings prioritize visibility and engagement, which may introduce selection bias by overrepresenting popular or positive reactions while underrepresenting negative, dissenting, or niche viewpoints. Additionally, the search mechanism did not allow for the inclusion of subcomments (i.e., replies to comments), limiting insight into interaction dynamics within comment threads.

Second, the study is observational and context-specific. All data were collected from videos using pro-recovery hashtags such as #Recovery, #SoberTok, and #WeDoRecover, which likely foster supportive discourse. As such, the overwhelmingly positive tone observed may not generalize to other corners of TikTok or to different social media platforms, especially those without a recovery-oriented framing or where more adversarial discourse may dominate. Third, the dataset was limited to English-language comments, which primarily reflect Western, anglophone TikTok users. Cultural norms, stigma, and discourse around substance misuse and recovery may vary widely across languages and cultures, and these perspectives are not captured in this study.

Fourth, although some commenters identified themselves as being in recovery, it was not possible to verify the background or recovery status of users. As a result, the sample may reflect a semi-insider community with shared lived experience, rather than the general public. Finally, while our search methods yielded a large dataset, time and resource constraints required that the three researchers divide the coding work. Although cross-validation was not possible for every comment, the team co-developed a shared coding framework, discussed coding strategies regularly, and cross-checked flagged or ambiguous cases to ensure consistency and reduce bias.

However, these limitations do not diminish the study’s contributions but instead highlight important directions for future research. Expanding this work to include other hashtags, platforms, languages, and cultural contexts could offer deeper insights into the evolving digital landscape of recovery discourse.

5. Conclusions

The majority of individuals who posted videos about their personal substance use recovery journeys on TikTok received positive or encouraging responses. Many comments share recovery strategies and personal experiences. While negative reactions were present, their rate of occurrence was not significant. This study suggests that social media platforms, such as TikTok, can serve as an accessible and supportive source of peer support for individuals in recovery, likely due to the algorithm and the high rates of commenters sharing their personal experiences. However, users should be aware of potential negative reactions. Future research could explore responses to initial comments for a deeper understanding of interactions within comment sections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., C.H., A.W. and S.-P.C.; methodology, S.-P.C.; formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation: M.C., C.H. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, R.A. and S.-P.C.; supervision, S.-P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived due to the collected data for this study was directly from an open-access public platform.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement was waived due to the collected data for this study was directly from an open-access public platform.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available on TikTok.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| CDA | Critical Discourse Analysis |

Appendix A. Definitions of Narrative Strategies

- Supportive Towards Recovery

- Comments in this category expressed positivity toward the original poster’s recovery journey or toward recovery from substance misuse more broadly. Support ranged from encouraging affirmations to expressions of admiration or celebration.

- 2.

- Unsupportive Towards Recovery

- Comments here showed limited or no engagement with the recovery content in a positive way. Rather than being overtly hostile, these responses were often apathetic, dismissive, or disengaged. This category includes two subtypes:

- Indifferent Towards Recovery: Comments that show disinterest or neutrality.

- Pro-Substance: Comments that normalize, promote, or joke about substance use.

- 3.

- Negative Towards Substance Use

- This category includes a small number of comments that were explicitly hostile or patronizing toward the original poster and/or their recovery journey. These responses often involved stigmatizing language or shaming tones.

- 4.

- Sharing

- Comments that shared additional knowledge, experiences, or strategies related to recovery. This category also includes tagging others to spread awareness or encourage dialogue, as well as references to personal or secondhand stories.

Appendix B

Appendix B contains details and data supplemental to the main text.

Table A1.

Coded Data (N = 3583).

Table A1.

Coded Data (N = 3583).

| Discourse Analysis Categories | Themes | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative strategies | Supportive Towards Recovery | 1969 (54.9%) |

| Sharing Strategies Stories Knowledge Tagging Others | 1207 (33.7%) 129 (3.6%) 929 (25.9%) 103 (2.9%) 46 (1.3%) | |

| Unsupportive Towards Recovery Indifferent Towards Recovery Pro-Substance | 152 (4.2%) 81 (2.3%) 71 (2.0%) | |

| Negative Towards Substance Use Shaming/Blaming Stigma Pitiful/Sympathetic | 133 (3.7%) 43 (1.2%) 29 (0.8%) 61 (1.7%) | |

| Other Unrelated Excluded (i.e., Language) | 333 (9.3%) 261 (7.3%) 72 (2.0%) | |

| Rhetorical Strategies | Exclamation | 813 (22.7%) |

| Emoji ❤️/❣️/ <3 😀/ :) ☹️/ :( ✨ ❄️ Other | 391 (10.9%) 265 (7.4%) 19 (0.5%) 14 (0.4%) 21 (0.6%) 18 (0.5%) 54 (1.5%) | |

| Capitalization | 258 (7.2%) | |

| Question | 219 (6.1%) | |

| Other | 2205 (61.5%) | |

| Linguistic Feature | Encouragement Proud Terms of encouragement Thank you for sharing Ma’am/Queen/Girl/Sis/Brother/Man/King Congratulations/Congrats/Celebrate Happy | 1917 (53.5%) 426 (11.9%) 552 (15.4%) 201 (5.6%) 651 (18.2%) 87 (2.4%) 52 (1.5%) |

| Identifying Stage of Recovery __day/month/year Sobriety/Sober Clean Addiction/Addicted/Addict | 962 (26.8%) 525 (14.7%) 343 (9.6%) 94 (2.6%) 112 (3.1%) | |

| Challenges of Recovery Brutal/Hard/Struggle/Horrible/Suffering Strong/Strength/Self-Control/Powerful Motivation/Inspiration Relapse/Cycle/Cycling Journey Hope Quit | 545 (15.2%) 244 (6.8%) 93 (2.6%) 76 (2.1%) 37 (1.0%) 23 (0.6%) 56 (1.6%) 30 (0.8%) | |

| Community Hashtag/ Slogan | 52 (1.5%) | |

| Other | 1575 (n = 43.9%) | |

| Power Relationship | Peer/Same Status | 3263 (91.1%) |

| Condescending/ Patronizing | 94 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 201 (5.6%) |

Table A2.

Correlation analysis of emoticons with narrative strategies and linguistic features.

Table A2.

Correlation analysis of emoticons with narrative strategies and linguistic features.

| ❤️ (n = 265) | ✨ (n = 21) | 🙂 (n = 19) | 🙁 (n = 14) | ❄️ (n = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative strategies | Supportive | 250 (94.3%) | 14 (66.7%) | 10 (52.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Unsupportive | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (16.7%) | |

| Sharing | 81 (30.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 14 (100%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Negative | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Linguistic Features | Stage of recovery | 66 (24.9%) | 3 (14.3%) | 9 (47.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Challenges of recovery | 22 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Encouragement | 180 (67.9%) | 13 (57.1%) | 10 (52.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| hashtags/slogans | 5 (0.02%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 1 (0.06%) |

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA’s Working Definition of Recovery: 10 Guiding Principles of Recovery; SAMHSA: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep12-recdef.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS): Summary of Results for 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2023. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-alcohol-drugs-survey/2019-summary.html (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Scientific Working Group. Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms 2007–2020; (Prepared by the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction); Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://csuch.ca/documents/reports/english/Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs-and-Harms-Report-2023-en.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Levinthal, C.F. Drugs, Behavior, and Modern Society, 9th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberger, S.F.; Park, T.W.; dellaBitta, V.; Hadland, S.E.; Bagley, S.M. “My life Isn’t defined by substance Use”: Recovery perspectives among young adults with substance Use disorder. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worley, J. Recovery in substance use disorders: What to know to inform practice. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Canadians’ Knowledge and Attitudes Around Drug Decriminalization: Results from a Public Opinion Research Survey; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/canadians-knowledge-attitudes-drug-decriminalization-results-public-opinion-research-survey-2024.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Cunningham, J.A.; Koski-Jännes, A. The last 10 years: Any changes in perceptions of the seriousness of alcohol, cannabis, and substance use in Canada? Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2019, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-P.; Stuart, H. Prejudices and discrimination related to substance use problems. In The Stigma of Mental Illness; Dobson, K.S., Stuart, H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zwick, J.; Appleseth, H.; Arndt, S. Stigma: How it affects the substance use disorder Patient. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Kuwabara, S.A.; O’Shaughnessy, J. The public stigma of mental illness and drug addiction: Findings from a stratified random sample. J. Soc. Work. 2009, 9, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.; Thornicroft, G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, D. Sociological perspectives on addiction. Sociol. Compass 2011, 5, 298–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel, A.M.; Bergman, B.G.; Colditz, J.B.; Kelly, J.F.; Milaham, P.J.; Massey, P.M. Using tiktok in recovery from substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 229, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, R.; Lynch, K.; Curtis, B. Technology and social media use among patients enrolled in outpatient addiction treatment programs: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, J.A.; Grande, S.W.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Elwyn, G. Naturally occurring peer Support through social media: The experiences of individuals with severe mental illness using YouTube. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliuc, A.M.; Best, D.; Iqbal, M.; Upton, K. Building addiction recovery capital through online participation in a recovery community. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 193, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical discourse analysis. In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Clockworks. Apify TikTok Scraper. [Computer Software]. 2024. Available online: https://apify.com/clockworks/tiktok-scraper (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Clockworks. Apify TikTok Comments Scraper. [Computer Software]. 2024. Available online: https://apify.com/clockworks/tiktok-comments-scraper (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Johnstone, B.; Andrus, J. Discourse Analysis, 4th ed.; Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulou, A.; Goutsos, D. Discourse Analysis: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. How TikTok Reads Your Mind. The New York Times, 5 December 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/business/media/tiktok-algorithm.html (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Singh, M. The place of social justice in higher education and social change discourses. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2011, 41, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karizat, N.; Delmonaco, D.; Eslami, M.; Andalibi, N. Algorithmic folk theories and identity: How TikTok users co-produce knowledge of identity and engage in algorithmic resistance. Assoc. Comput. Mach. 2021, 5, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A. The politics of alignment and the ‘quiet transgender revolution’ in Fortune 500 corporations, 2008 to 2017. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2021, 19, 1095–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madill, A.; Duara, R.; Goswami, S.; Graber, R.; Hugh, J.S. Pathways to recovery model of youth substance misuse in Assam, India. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deegan, P.E. Part One: Consumer/survivor perspectives: Recovery as a self-directed process of healing and transformation. In Recovery and Wellness: Models of Hope and Empowerment for People with Mental Illness; Brown, C., Ed.; The Haworth Press Inc.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-P.; Krupa, T.; Lysaght, R.; McCay, E.; Piat, M. The development of recovery competencies for in-patient mental health providers working with people with serious mental illness. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 40, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).