Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to assess the prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with acute leukemia in Vietnam and to identify associated sociodemographic and clinical factors. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Hematology and Blood Transfusion Center of Bach Mai Hospital, a national tertiary care facility in Hanoi, Vietnam. A total of 82 patients diagnosed with acute leukemia were recruited using a convenience sampling method. Data on sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, residence, education, occupation, marital status, and income) and clinical information (e.g., leukemia type, treatment stage, comorbidities, substance use) were collected. Depression and anxiety were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Zung’s Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). Multivariate logistic and Tobit regression analyses were applied to explore associated factors. Results: Participants had a mean age of 43.4 years (SD = 14.0), with 53.7% male and 69.5% residing in rural areas. Most were married (82.9%) and had completed high school (45.1%). Farmers constituted the largest occupational group (29.3%). The mean BDI score was 13.7 (SD = 9.8), and the mean SAS score was 39.2 (SD = 6.3). Overall, 50.0% of patients met criteria for depression, while 26.8% exhibited clinically significant anxiety symptoms. Among those with anxiety, 59.1% had mild symptoms, 22.7% moderate, and 18.2% severe or very severe. Patients with education above high school (OR = 7.32; 95% CI: 1.01–53.23), a spouse (OR = 25.10; 95% CI: 2.14–294.55), or comorbidities (OR = 8.05; 95% CI: 1.63–39.68) had significantly higher odds of depression. A higher income (>10 million VND/month) was associated with lower depression scores (Coef. = −6.05; 95% CI: −11.65 to −0.46). Regarding anxiety, the female gender was associated with higher odds (OR = 3.80; 95% CI: 1.21–11.93) and SAS scores (Coef. = 4.07; 95% CI: 1.64–6.51), while higher income predicted lower anxiety severity (Coef. = −3.74; 95% CI: −6.57 to −0.91). Conclusions: This Vietnamese hospital-based study highlights a high prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with acute leukemia. Routine mental health screening and culturally appropriate psychosocial interventions are strongly recommended to improve patient well being.

1. Introduction

Acute leukemia is a life-threatening hematological malignancy characterized by the rapid proliferation and accumulation of abnormal, immature white blood cells—known as blast cells—in the bone marrow and peripheral circulation [1]. These cells disrupt normal hematopoiesis, leading to anemia, infection, and bleeding due to cytopenias, and the disease requires urgent, intensive treatment [2]. Globally, the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) for leukemia declined from 6.89 to 5.63 per 100,000 between 1990 and 2021, while the age-standardized death rate (ASDR) fell from 5.56 to 3.89 per 100,000, reflecting advancements in diagnosis and treatment [3]. However, subtype trends differ. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)—the most common acute leukemia in adults—has seen an increase in both incidence and mortality, with global AML deaths rising by 1.57 per 100,000 between 1990 and 2019 [4], whereas acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most prevalent in children and young adults, has shown a 50% reduction in mortality despite a 129% increase in case numbers over the past three decades [3,5]. In Vietnam, AML accounts for approximately 80% of adult acute leukemia cases, with a median age of 39 years, and chromosomal abnormalities—most commonly t(15;17)—present in over 60% of cases [6]. These data emphasize the continuing clinical and epidemiological burden of acute leukemia both globally and within Vietnam.

In adults, treatment of acute leukemia typically involves an intensive multimodal approach, which may include induction and consolidation chemotherapy, targeted therapies, radiation therapy, and, in eligible cases, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [7]. Among these, chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment and has been shown to significantly improve survival outcomes for many patients [8]. However, these aggressive therapeutic protocols are often associated with a host of adverse effects, both physical and psychological. Patients frequently report distressing symptoms, such as fatigue, pain, nausea, mucositis, and immunosuppression, as well as emotional challenges, such as fear, hopelessness, and loss of control [9]. These symptoms, when persistent or severe, can markedly diminish patients’ overall quality of life (QoL) and psychological well being [10].

Mental health disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, are highly prevalent among individuals diagnosed with malignancies such as acute leukemia. These conditions are classified as internalizing symptoms, which involve inwardly directed emotional distress such as persistent sadness, excessive worry, fear, hopelessness, and withdrawal from social interactions. Internalizing disorders often remain unnoticed, as their symptoms are less overt than externalizing behaviors, yet they significantly impair daily functioning and overall well being. In cancer populations, including those with acute leukemia, the psychological burden of these disorders is profound. The abrupt nature of the diagnosis, along with the intensity and uncertainty of treatment, substantially increases vulnerability to psychological distress [11,12]. Empirical evidence consistently highlights the high burden of mental health conditions in this population. For example, Zhong et al. (2024) reported depression and anxiety rates of 43.2% and 48.5%, respectively, among adult AML patients [13], while Dogu et al. (2017) observed a striking 81% prevalence of depression and 38.1% of anxiety in newly diagnosed acute leukemia cases [14]. In younger populations, Cano-Vázquez et al. (2022) found that 43.2% of pediatric patients exhibited depressive symptoms, though anxiety was lower at 10% [15]. Among young adults with AML, Bedurftig (2022) reported an anxiety prevalence of 8.8% [16], underscoring the variability in psychological burden across age groups and disease stages. These mental health conditions are not merely secondary concerns but have substantial clinical implications. Depression and anxiety have been consistently linked to reduced treatment adherence, delayed medical appointments, and impaired ability to follow complex treatment regimens [17,18]. Depression, in particular, can lead to apathy, low energy, and impaired decision-making capacity—factors that hinder active participation in care and may negatively affect recovery and survival outcomes [17,18].

Given these implications, early identification and management of psychological distress are vital. Timely psychological interventions—such as counseling or cognitive-behavioral strategies—can alleviate emotional suffering, improve treatment compliance, and enhance overall health outcomes. Importantly, comprehensive cancer care must attend to both the physical and psychological dimensions of illness [19,20]. Despite growing awareness, depression and anxiety in acute leukemia patients are frequently underdiagnosed or misattributed to the disease or its treatment. Overlapping symptoms such as fatigue, anorexia, and sleep disturbances may be perceived by healthcare providers and patients as expected responses to illness, leading to delayed recognition and missed opportunities for early intervention [19,20]. Addressing these gaps in care is essential for improving quality of life and optimizing clinical outcomes for this vulnerable population.

In Vietnam, research into the psychological health of cancer patients, particularly those with acute leukemia, remains limited. There is a notable lack of systematic studies evaluating the prevalence of depression and anxiety and the factors contributing to these conditions in this patient population. Addressing this gap is essential for informing clinical practice and improving holistic cancer care. Therefore, the present study was conducted to assess the levels of depression and anxiety among patients with acute leukemia and to identify factors associated with these psychological conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at the Hematology and Blood Transfusion Center of Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam. This study aimed to assess the prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among patients diagnosed with acute leukemia. Between January 2022 to July 2022, the Hematology and Blood Transfusion Center of Bach Mai Hospital treated 82 patients diagnosed with acute leukemia, and all of these patients were included in this study. No refusals were recorded, ensuring complete coverage of eligible cases during the data collection period. The recruitment process adhered to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and quality of the sample.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who met the diagnostic criteria for acute leukemia based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines [21]; (2) clinical presentation that was consistent with characteristic signs and symptoms of acute leukemia; (3) the presence of ≥20% blast cells with nuclei identified in bone marrow aspirate; and (4) patients who provided informed consent to participate in this study.

Exclusion criteria included (1) patients experiencing acute medical complications, such as severe infections or coma; (2) patients with chronic severe comorbidities or physical impairments that interfered with communication or comprehension; (3) individuals with cognitive impairment or disorders of consciousness that precluded meaningful participation; (4) patients with a documented history of depression prior to their leukemia diagnosis; and (5) individuals who declined to participate in the research.

A convenient sampling method was employed to select participants who met the eligibility criteria during the study period. The study protocol received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Bach Mai Hospital (Approval Code: 7004/QD-BM).

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected through a combination of clinical assessments, medical record reviews, and patient self-reports using standardized instruments. A customized medical record form was developed to align with the study objectives and was used to collect comprehensive data in three domains: (1) demographic and clinical characteristics, (2) anxiety assessment, and (3) depression assessment.

2.3. Demographic and Clinical Variables

Collected demographic information included age, gender, place of residence (urban or rural), level of education, employment status, marital status, household economic condition, and living arrangements. Clinical data encompassed age at diagnosis, disease duration, existing comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease), history of substance use (e.g., tobacco, alcohol), treatment stage (induction, consolidation, or maintenance), and treatment modality (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or transplantation).

2.4. Anxiety Assessment

Anxiety levels were evaluated using Zung’s Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), a validated self-report instrument comprising 20 items that assess both psychological and somatic symptoms of anxiety. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time) based on the respondent’s experiences during the past week. The total raw score ranges from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety symptoms [22]. Based on total SAS scores, participants were categorized into five groups: no anxiety (≤40), mild anxiety (41–50), moderate anxiety (51–60), severe anxiety (61–70), and very severe anxiety (71–80) [23].

2.5. Depression Assessment

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a widely recognized and validated screening tool for evaluating the severity of depression. The Vietnamese-translated version of the BDI was used for this study. The inventory consists of 21 items, each rated from 0 to 3, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 63. The following cut-off points were used for categorization: no depression (0–13), mild depression (14–19), moderate depression (20–28), and severe depression (29–63) [24].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using Stata version 16.0. The data underwent descriptive statistical analysis. The chi-squared test and the Mann–Whitney U test were utilized to assess variations in the prevalence of depression among different demographic and clinical profiles. A multivariate logistic and Tobit regression analysis was conducted to determine the variables associated with depression, anxiety, and their scores. A stepwise forward model was employed to build the reduced model. The statistical significance was determined using a p-value of less than 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 82 patients diagnosed with acute leukemia participated in this study. The gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 53.7% male (n = 44) and 46.3% female (n = 38). The majority of participants resided in rural areas (69.5%), while 30.5% lived in urban settings. In terms of educational attainment, most had completed high school (45.1%), followed by those with an undergraduate degree or higher (25.6%), secondary education (19.5%), and elementary education (9.8%).

Regarding occupational status, farmers made up the largest proportion of the sample (29.3%), followed by white-collar workers and others (each 20.7%), businesspeople (19.5%), students (6.1%), and blue-collar workers (3.7%). A significant proportion of patients were married (82.9%), while 17.1% were single, widowed, or divorced.

When classified by household monthly income, 37.8% of participants reported earning less than 5 million VND, 31.7% earned between 5 to 10 million VND, 22.0% had an income ranging from 10 to 20 million VND, and only 8.5% reported earning more than 20 million VND per month. The mean current age of the participants was 43.4 years (SD = 14.0), and the mean age at disease onset was 42.5 years (SD = 14.2).

In terms of disease duration, the majority of patients (68.3%) had been diagnosed within the past six months, 14.6% had a duration between 7–12 months, and 17.1% had lived with the disease for more than 12 months. Regarding comorbidities, 75.6% reported no existing comorbid condition. Among those with comorbidities, digestive diseases (14.6%) were the most common, followed by heart-related diseases (8.5%), and smaller proportions reported respiratory (3.7%), endocrine (3.7%), musculoskeletal diseases (3.7%), and others (4.9%).

With respect to substance use, 26.8% of patients reported smoking, 7.3% used pipe tobacco, and 24.4% consumed alcohol. The majority of patients were diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML, 76.8%), while the remaining 23.2% had acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

In terms of treatment stage, 50.0% were undergoing induction therapy, 12.2% were in the consolidation phase, 9.8% were receiving maintenance therapy, 3.7% were in relapse, and 24.4% were not receiving active treatment at the time of the survey. Most patients (75.6%) were being treated with a chemical regimen, while 24.4% received supportive care only (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients.

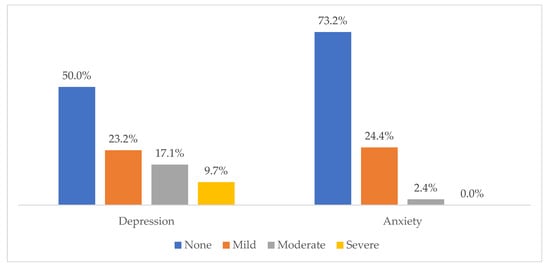

The mean BDI score was 13.7 (SD = 9.8), and the SAS score was 39.2 (SD = 6.3). Figure 1 shows that according to the Beck scale, mild depression accounts for the highest rate at 23.2%, and moderate and severe depression is less at 17.1% and 9.8%, respectively. Overall, 50% of patients suffered from depression. Regarding anxiety, 73.2% did not have an anxiety disorder, 24.4% had a mild anxiety disorder, and 2.4% had a moderate anxiety disorder. Generally, 26.8% experienced an anxiety disorder.

Figure 1.

Levels of depression and anxiety among acute leukemia patients.

In Table 2, the logistic regression analysis identified several factors significantly associated with the likelihood of having depression. Patients with a household monthly income above 10 million VND had significantly lower odds of depression (OR = 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.44), indicating a strong protective effect of higher income. In contrast, those with education levels higher than high school were significantly more likely to experience depression (OR = 7.32; 95% CI: 1.01–53.23), suggesting that greater educational attainment may be associated with heightened awareness or emotional burden. Marital status also showed a strong association, with patients who were married exhibiting markedly higher odds of depression (OR = 25.10; 95% CI: 2.14–294.55). Additionally, the presence of any comorbidity was a significant risk factor (OR = 8.05; 95% CI: 1.63–39.68). Age, disease duration, and education at the high school level did not significantly influence the odds of depression.

Table 2.

Factors associated with depression and anxiety among acute leukemia patients.

Tobit regression analysis of the BDI depression scores revealed similar trends to the binary depression outcome. Patients with household incomes greater than 10 million VND had significantly lower depression scores (Coef. = −6.05; 95% CI: −11.65 to −0.46), consistent with the protective role of higher economic status. Likewise, the presence of comorbid conditions was associated with significantly higher BDI scores (Coef. = 6.74; 95% CI: 2.07 to 11.41), suggesting a greater psychological burden among those with additional health issues. Other variables, such as marital status and education above high school, did not show statistically significant associations with the depression score, although the directions of effect were consistent with the binary findings. High school education and moderate income were associated with lower scores, but these did not reach statistical significance.

In the logistic regression analysis, gender and marital status were significantly associated with the presence of anxiety. Female patients had significantly higher odds of experiencing anxiety compared to males (OR = 3.80; 95% CI: 1.21–11.93), highlighting gender as a key risk factor. Similarly, patients who were married were more likely to report anxiety than their unmarried or widowed counterparts (OR = 4.21; 95% CI: 1.00–7.41). Household income and education level did not show statistically significant associations with the odds of anxiety, although patients with higher income (>10 million VND) tended to report lower odds (OR = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.07–1.11). Other factors, such as age, comorbidity, treatment stage, and disease duration, did not demonstrate significant associations with anxiety presence in the logistic model.

Regarding anxiety severity, measured by the Zung SAS score, several significant associations were observed. Female gender was associated with significantly higher anxiety scores (Coef. = 4.07; 95% CI: 1.64–6.51), reinforcing the higher emotional vulnerability among women. Patients with a household income exceeding 10 million VND per month had significantly lower anxiety scores (Coef. = −3.74; 95% CI: −6.57 to −0.91), indicating the mitigating effect of better financial resources on anxiety symptoms. Other variables, including education level, marital status, and treatment stage, did not significantly influence the anxiety score. Although some associations trended in expected directions—such as higher education and being married linked with higher anxiety—these did not reach statistical significance.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the levels of anxiety and depression among patients diagnosed with acute leukemia and to identify associated factors. The findings revealed a markedly high prevalence of psychological distress in this population, with depression affecting 50.0% of participants and anxiety present in 26.8%. Several sociodemographic and clinical variables, including gender, educational attainment, income, marital status, and comorbidities, were significantly associated with mental health outcomes. These findings contribute important insights into the psychological burden borne by patients with acute leukemia and underscore the necessity for integrated mental health support within hospital-based care for this vulnerable group.

The reported prevalence of depression in this study aligns closely with prior research conducted by Gu (2019) [12] and Zhou (2007) [25], which documented rates of 45.6% and 47.83%, respectively. However, our observed rates were notably higher than those reported by Aili (2021) [26], Gheihman (2015) [11], and Lennmyr (2020) [27], where prevalence ranged from 17.8% to 31%. This disparity may be attributed to differences in study populations, settings, cultural contexts, and diagnostic tools [20]. Consistent with previous findings by Wang et al. (2021) [28], who reported anxiety and depression rates of 50.7% and 43.7%, respectively, our results highlight the unique psychological challenges faced by acute leukemia patients. Unlike many solid tumors, acute leukemia presents a rapid clinical course with an unpredictable prognosis, invasive diagnostic and treatment procedures, and a higher perceived risk of recurrence and mortality. These factors likely exacerbate psychological distress among patients and contribute to elevated rates of both depression and anxiety [29,30].

When compared to other chronic illnesses, the mental health burden among acute leukemia patients remains substantial. For instance, the prevalence of depression in individuals with diabetes has been reported to range between 34% and 50%, with anxiety rates between 38% and 50% [31,32]. Among patients with cardiovascular disease, depression and anxiety rates are even higher, reaching 53% and 61.6%, respectively [33,34]. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), depression affects approximately 62.1% of patients, while anxiety ranges from 17% to 47.8% [35]. A pooled estimate among cancer patients in general revealed depression and anxiety prevalences of 39.1% and 47.8%, respectively [36]. Compared to these conditions, the prevalence of depression (50.0%) in our sample is consistent with the upper ranges reported in chronic diseases and general oncology populations, while anxiety (26.8%) appears slightly lower than in some other groups. Nonetheless, these comparisons underscore the pressing need for integrated psychosocial care in the management of acute leukemia.

The regression results showed that higher household income was a consistent protective factor against both depression and anxiety. Patients with income levels above 10 million VND per month had significantly lower odds of depression (OR = 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.44) and lower BDI scores (Coef. = −6.05; 95% CI: −11.65 to −0.46). This aligns with previous research indicating that financial hardship is a major predictor of psychological distress in cancer patients, often contributing to what is referred to as “financial toxicity” [29]. Interestingly, income also had a significant inverse association with anxiety severity (Coef. = −3.74; 95% CI: −6.57 to −0.91), although the effect on anxiety likelihood did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that financial stability may not only reduce depressive symptoms through reduced material hardship but may also buffer emotional reactivity in stressful healthcare contexts.

Gender emerged as a significant predictor of anxiety but not depression. Female patients had significantly higher odds of experiencing anxiety (OR = 3.80; 95% CI: 1.21–11.93) and significantly higher Zung SAS scores (Coef. = 4.07; 95% CI: 1.64 to 6.51), consistent with global patterns showing greater vulnerability to anxiety among women in both general and clinical populations [37,38]. Biological differences in stress response, as well as sociocultural expectations—especially in Vietnamese society, where women frequently serve as primary caregivers—may contribute to this disparity. Although gender was not significantly associated with depression in this study, the overall trend still pointed toward greater psychological burden among women [39].

Marital status showed a surprising pattern in both regression models. Married patients were significantly more likely to experience depression (OR = 25.10; 95% CI: 2.14–294.55) and anxiety (OR = 4.21; 95% CI: 1.00–7.41), though the association with BDI and SAS scores was not statistically significant. These findings contrast with studies suggesting that marital relationships typically serve as a protective factor against psychological distress. One possible explanation lies in the bidirectional emotional strain that may occur within patient–caregiver dyads, especially when partners face significant caregiving burdens and shared financial stress [40,41]. It is also plausible that individuals in intimate relationships may experience compounded worry about the future, partner well being, and family responsibilities, contributing to elevated emotional burden.

Comorbidities were significantly associated with both the presence and severity of depression. Patients with any comorbid condition had over eight times the odds of experiencing depression (OR = 8.05; 95% CI: 1.63–39.68) and significantly higher BDI scores (Coef. = 6.74; 95% CI: 2.07–11.41). This aligns with prior research showing that multiple health burdens can lead to functional limitations, increased treatment complexity, and poorer coping resources, all of which may exacerbate depressive symptoms. Interestingly, comorbidities were not significantly associated with anxiety, which may suggest that the cumulative effect of chronic disease on mood disturbances is more relevant for depressive outcomes than for anxiety in this specific clinical context.

Additionally, educational attainment demonstrated a complex relationship with depression. Compared to patients with lower educational levels, those with an education above high school had significantly higher odds of depression (OR = 7.32; 95% CI: 1.01–53.23), though this was not mirrored in the continuous depression scores. This may reflect increased health literacy and awareness of disease prognosis among more educated patients, potentially intensifying their psychological burden [39]. However, it is worth noting that educational attainment was not significantly associated with anxiety outcomes, suggesting that its effect may be more relevant to internalized emotional responses (e.g., depression) than to anxious arousal.

Notably, age, treatment stage, and disease duration were not significantly associated with any psychological outcome in either model. While older patients might be presumed to face greater vulnerability due to declining physical resilience, our findings did not support a significant association between age and psychological distress. Similarly, no clear patterns were found across treatment phases (induction, consolidation, relapse, or maintenance), which may reflect the heterogeneity of individual experiences at each treatment stage. These null findings may also be due to limited sample size and potential confounding factors not captured in this model.

The findings of this study have important implications for clinical practice. Given the high prevalence of psychological distress among acute leukemia patients, routine mental health screening using validated tools should be integrated into standard oncology care to enable early detection and intervention. Psychological symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances are frequently mistaken for side effects of treatment, leading to under-recognition of depression and anxiety. A range of evidence-based interventions has shown effectiveness in this population. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) remains the most established method for addressing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors, while mindfulness-based interventions, including virtual reality-assisted meditation, have demonstrated reductions in anxiety and improvements in quality of life during chemotherapy [42]. Pharmacological treatment may be appropriate for patients with severe psychological distress, especially when symptoms interfere with daily functioning or treatment adherence [43,44]. Family-centered interventions that engage both patients and caregivers have also proven effective in improving psychological outcomes and enhancing caregiver resilience [28]. Additional approaches, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Schema Therapy, may offer benefits, particularly for patients with entrenched emotional schemas or chronic distress. Importantly, all interventions should be culturally adapted to the Vietnamese context, considering local beliefs, family structures, and healthcare system access to ensure relevance and effectiveness.

Nonetheless, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences between associated factors and psychological outcomes. Second, the use of convenience sampling at a single tertiary hospital in Vietnam may introduce selection bias and restrict the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of patients with acute leukemia. Third, the modest sample size may limit the statistical power to detect associations with smaller effect sizes. Additionally, important psychosocial variables such as social support, coping strategies, and caregiver burden were not assessed in this study, despite their potential influence on mental health outcomes. Future research should consider longitudinal designs to examine changes in depression and anxiety over time while also incorporating a broader range of psychosocial and contextual factors. Multicenter studies with larger and more diverse samples are also recommended to enhance generalizability and inform targeted interventions.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals a high prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with acute leukemia, emphasizing the psychological toll of this aggressive disease. Factors such as female gender, higher education, lower income, marital status, and the presence of comorbidities were significantly associated with increased psychological distress. These findings highlight the urgent need to integrate routine mental health screening into standard oncology care for early identification and management of emotional disorders. Furthermore, targeted psychosocial interventions—tailored to the cultural and clinical context—should be implemented to support both patients and their caregivers. Strengthening the mental health component of cancer care has the potential to improve treatment adherence, enhance quality of life, and ultimately lead to better clinical outcomes for individuals affected by acute leukemia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T.H.A., D.M.T., and N.T.T.; data curation, P.L.H.; formal analysis, N.T.V. and P.T.M.N.; investigation, N.T.T., P.T.T.H., and P.T.M.N.; methodology, T.T.H.A., D.M.T., and P.L.H.; project administration, N.T.V., D.M.T., and V.T.L.; resources, N.T.T., P.T.T.H., and P.T.M.N.; software, T.T.H.A.; supervision, D.M.T., P.T.T.H., P.L.H., and V.T.L.; validation, T.T.H.A. and N.T.V.; visualization, V.T.L.; writing—original draft, T.T.H.A., N.T.V., D.M.T., N.T.T., P.T.T.H., P.L.H., V.T.L., and P.T.M.N.; writing—review and editing, T.T.H.A., N.T.V., D.M.T., N.T.T., P.T.T.H., P.L.H., V.T.L., and P.T.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of Bach Mai Hospital (Approval Code: 7004/QD-BM; Approval date: 7 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical approval requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shimony, S.; Stahl, M.; Stone, R.M. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 502–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, E.N.; Ronnebaum, S.M.; Zaidi, O.; Patel, D.A.; Nehme, S.A.; Chen, C.; Almeida, A.M. A systematic literature review of disease burden and clinical efficacy for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Blood Res. 2021, 11, 325–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Pang, W.; Deng, M.; Zheng, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, Z.; Bai, Z. Global, regional, and national burden of leukemia, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease in 2021. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1542317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, H. Global, national, and regional burden of acute myeloid leukemia among 60-89 years-old individuals: Insights from a study covering the period 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1329529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, D.; Dhruvkumar, G.; Fnu, S.; Nupur, S.; Mohit, L.; Saifullah, S.; Adit Alpesh, D.; Dharmik, P.; Vishrant, A.; Juhi, P.; et al. Epidemiological Trends of Acute Lymphoid Leukemia in Individuals Younger Than 20 Years across 204 Countries and Territories from 1990–2021: A Benchmarking Global Analysis. Blood 2024, 144 (Suppl. 1), 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, L.T.T.; Ha, C.T.; Ha, N.T.T.; Beaupha, S.M.C.; Nghia, H.; Tung, T.T.; Son, N.T.; Binh, N.T.; Dung, P.C.; Vu, H.A.; et al. Cytogenetic Characteristics of de novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Southern Vietnam. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubnitz, J.E.; Inaba, H.; Dahl, G.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Bowman, W.P.; Taub, J.; Pounds, S.; Razzouk, B.I.; Lacayo, N.J.; Cao, X.; et al. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: Results of the AML02 multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leak Bryant, A.; Walton, A.L.; Pergolotti, M.; Phillips, B.; Bailey, C.; Mayer, D.K.; Battaglini, C. Perceived Benefits and Barriers to Exercise for Recently Treated Adults With Acute Leukemia. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2017, 44, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhang, M.; Wan, C.; Li, X. Reliability analysis of the Chinese version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Leukemia (FACT-Leu) scale based on multivariate generalizability theory. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.A. Physiologic and psychological symptoms experienced by adults with acute leukemia: An integrative literature review. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2014, 41, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheihman, G.; Zimmermann, C.; Deckert, A.; Fitzgerald, P.; Mischitelle, A.; Rydall, A.; Schimmer, A.; Gagliese, L.; Lo, C.; Rodin, G. Depression and hopelessness in patients with acute leukemia: The psychological impact of an acute and life-threatening disorder. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Hao, X.; Cong, L.; Sun, J. The prevalence, risk factors, and prognostic value of anxiety and depression in refractory or relapsed acute myeloid leukemia patients of North China. Medicine 2019, 98, e18196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Dan, X.; Wenchao, L. Prevalence, risk factors, and prognostic value of anxiety and depression in acute myeloid leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2024, 147, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmet Hilmi, D.; Rafet, E.; Ebru, Y.; Nihan, N.; Ceyda, A.; Osman, Y.; Elif, S.; Habip, G. Are We Aware of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Leukemia. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elba Nelly, C.-V.; Ángeles Abigail, G.-G.; Polette Alejandra, S.-F.; Luis Eduardo, G.-C.; Daniel Alejandro, O.-F.; Irma Beatriz, G.-M.; Máximo Alejandro, G.-F.; Socorro, M.-M. Depression, anxiety and quality of life in pediatric patients with leukemia. Rev. Medica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2022, 60, 517–523. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B. Psychological Distress in Young Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Undergoing Induction Chemotherapy. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2022, 136, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleoni, M.; Mandala, M.; Peruzzotti, G.; Robertson, C.; Bredart, A.; Goldhirsch, A. Depression and degree of acceptance of adjuvant cytotoxic drugs. Lancet 2000, 356, 1326–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.J. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.; Esplen, M.J.; Peter, E.; Howell, D.; Rodin, G.; Fitch, M. How haematological cancer nurses experience the threat of patients’ mortality. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 2175–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, G.; Yuen, D.; Mischitelle, A.; Minden, M.D.; Brandwein, J.; Schimmer, A.; Marmar, C.; Gagliese, L.; Lo, C.; Rydall, A.; et al. Traumatic stress in acute leukemia. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.A.; Shah, B.; Advani, A.; Aoun, P.; Boyer, M.W.; Burke, P.W.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Dinner, S.; Fathi, A.T.; Gauthier, J.; et al. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2021, 19, 1079–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W.W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 1971, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W.W. How Normal Is Anxiety? Upjohn Company: Portage, MI, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhang, W.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, D.; Su, Z.; Meng, X.; Hui, L.; Tian, W. The changes of oxidative stress and human 8-hydroxyguanine glycosylase1 gene expression in depressive patients with acute leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2007, 31, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili, K.; Arvidsson, S.; Nygren, J.M. Health related quality of life and buffering factors in adult survivors of acute pediatric lymphoblastic leukemia and their siblings. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennmyr, E.B.; Karlsson, K.; Abrahamsson, M.; Ebrahim, F.; Lübking, A.; Höglund, M.; Juliusson, G.; Hallböök, H. Introducing patient-reported outcome in the acute leukemia quality registries in Sweden. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020, 104, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Lin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, R. Comparison of the anxiety, depression and their relationship to quality of life among adult acute leukemia patients and their family caregivers: A cross-sectional study in China. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, G.; Deckert, A.; Tong, E.; Le, L.W.; Rydall, A.; Schimmer, A.; Marmar, C.R.; Lo, C.; Zimmermann, C. Traumatic stress in patients with acute leukemia: A prospective cohort study. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, M.; Neale, R.E.; Klein, K.; O’Connell, D.L.; Gooden, H.; Goldstein, D.; Merrett, N.D.; Wyld, D.K.; Rowlands, I.J.; Beesley, V.L. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in people with pancreatic cancer and their carers. Pancreatology 2017, 17, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.-E.; Nada, K.A.; Gehad, T.G.; Madeeh, A.K.; Moaz, K.; Mahmoud, R.; Wessam, H.H.; Eman, A.A.; Marwa Gamal, M.; Ahmed, A.; et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among diabetic patients in Egypt: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2023, 102, e35988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasturi, H.; Ali, M.F.; Saurabh, A.; Sanjay Kumar, V.; Vipul, R.S. Assessment of depression, anxiety and stress among patients with type II diabetes mellitus attending a tertiary care centre. Int. J. Adv. Med. 2023, 10, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongguang, L.; Jue, C.; Junxia, W.; Min, T.; Jingyi, G.; Jingyu, H.; Qing, Z.; Gang, Z.; Xiaoli, H.; Beibei, H. The Degree of Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Cardiovascular Diseases as Assessed Using a Mobile App: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e48750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihitina, S.; Missaye, M.; Tewodrose, H.; Tafere Mulaw, B. The prevalence of depression and anxiety among cardiovascular patients at University of Gondar specialized hospital using beck’s depression inventory II and beck anxiety inventory: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, P.; Supa, P. Anxiety and depressive features in chronic disease patients in Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam. South Afr. Med. J. 2016, 22, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivana, B.; Erik, R.S.; Erik, R.S.; Erik, R.S.; Hege, S.; Ottar, B.; Ottar, B. Prevalence trends of depression and anxiety symptoms in adults with cardiovascular diseases and diabetes 1995–2019: The HUNT studies, Norway. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.; Mackenzie, R.; Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinz, A.; Herzberg, P.Y.; Lordick, F.; Weis, J.; Faller, H.; Brähler, E.; Härter, M.; Wegscheider, K.; Geue, K.; Mehnert, A. Age and gender differences in anxiety and depression in cancer patients compared with the general population. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Hu, R.; Wu, Y. Factors associated with quality of life of adult patients with acute leukemia and their family caregivers in China: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivziku, D.; Clari, M.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G.; Matarese, M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and caregivers: An actor-partner interdependence model analysis. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2019, 28, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Carver, C.S.; Spillers, R.L.; Crammer, C.; Zhou, E.S. Individual and dyadic relations between spiritual well-being and quality of life among cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 20, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixia, Z.; Xiao, J.; Xiaolin, K.; Biyu, S.; Ding-Rong, Q.; Jinrui, P.; Erhui, C.; Xiping, D.; Xiaoling, C.; Cho Lee, W. Effects of a Virtual Reality-Based Meditation Intervention on Anxiety and Depression Among Patients With Acute Leukemia During Induction Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 47, E159–E167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, W.; Ewa, W.; Krzysztof, K. Mental state and its psychophysical conditions in patients with acute leukaemia treated with bone marrow transplantation. Psychiatr. Danub. 2015, 27, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Anna, W.; Irena, K.-M.; Krzysztof, K. Anxiety and depression in patients with acute leukaemia treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychiatr. Danub. 2019, 31, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).