Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) features a complex tumor microenvironment, where cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play key roles in tumor progression, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), immune evasion, and resistance to treatment. This article updates our understanding of CAF origins, diversity, and functions in RCC, incorporating recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data that refine CAF subtypes. The paper explores the mechanistic interactions between CAFs and EMT, focusing on CAF-derived signaling pathways like TGF-β, IL-6/STAT3, HGF/c-MET, and Wnt/β-catenin, as well as extracellular-vesicle-mediated transfer of miRNAs and lncRNAs that promote metastatic behavior in RCC. It also addresses how CAF-driven remodeling of the extracellular matrix, metabolic changes, and activation of YAP/TAZ contribute to invasion and resistance to therapies, particularly in relation to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, and immune checkpoint blockade. The review highlights emerging therapeutic strategies targeting CAFs, such as inhibiting specific signaling pathways, disrupting CAF–tumor cell communication, and selectively depleting CAFs. In conclusion, it identifies limitations in current CAF classification systems and proposes future research avenues to improve RCC-specific CAF profiling and exploit the CAF–EMT axis for therapeutic gain.

1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for over 90% of kidney malignancies and presents significant clinical challenges due to its heterogeneity and metastatic behavior at diagnosis in many patients [1]. In recent years, the tumor microenvironment (TME) has gained recognition as a vital player in RCC progression, therapy resistance, and metastasis [2]. Among the stromal constituents of the TME, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are particularly important. CAFs are activated fibroblasts that support tumor progression by remodeling the extracellular matrix (ECM), promoting angiogenesis, and creating an immunosuppressive niche [3]. Unlike normal fibroblasts, which are typically involved in tissue homeostasis and wound repair, CAFs acquire a persistently activated phenotype within the TME, characterized by enhanced secretion of ECM proteins, cytokines, and growth factors [4]. CAFs exert pleiotropic effects on cancer cells, influencing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), immune modulation, angiogenesis, and metabolic reprogramming [5]. Their presence has been strongly correlated with poor clinical outcomes in multiple cancer types, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric carcinoma, lung cancer, and RCC [6,7,8,9,10]. EMT, a process in which epithelial cells lose their polarity and acquire mesenchymal properties, is not only central to metastasis but is increasingly recognized as a source of CAFs in solid tumors, including RCC [2]. While both CAFs and EMT have independently been recognized as critical contributors to RCC progression, the interplay between these two phenomena remains insufficiently explored in the context of RCC [11,12]. This represents a significant gap in the current understanding of the TME’s influence on disease progression and therapeutic resistance [13]. Therefore, the primary aim of this review is to uncover and provide deeper insight into the mechanisms governing the interaction between CAFs and the surrounding stromal components.

2. CAFs Origin and Classification

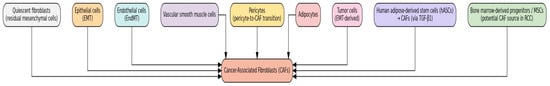

CAFs in RCC are derived from a diverse range of cellular origins (Figure 1). Quiescent fibroblasts—believed to be residual intermediate mesenchymal cells from organ development—may represent one source of CAF precursors. Additionally, various cell types can transdifferentiate into CAFs, including endothelial and epithelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, pericytes, adipocytes, and even tumor cells undergoing EMT. Both EMT and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) have been shown to facilitate the conversion of epithelial and endothelial cells into CAFs, respectively. Furthermore, human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) can differentiate into CAFs when stimulated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and pericyte-to-CAF transition has also been documented [14,15]. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) are additional sources shown to give rise to CAFs in various cancers [16]. Given their abundance in kidney tissue, BM-MSCs present a promising research focus. However, current evidence remains inconclusive regarding their ability to convert into CAFs specifically within RCC [16,17].

Figure 1.

Cellular Origins of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts.

2.1. Challenges in CAF Classification

For a long time, CAFs were primarily believed to comprise two dominant subtypes: myofibroblast-like CAFs (myCAFs) and inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs) [18,19]. However, with the advancement of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), it has become clear that CAFs are far more diverse, comprising multiple subpopulations with distinct phenotypic and functional traits [19]. Increasingly, antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs) are being recognized as a third core CAF subtype present across various tumor types [20,21,22]. Additionally, scRNA-seq has revealed the presence of several rare or specialized CAF subsets in the tumor microenvironments of different cancers [21,22,23,24]. The following section will explore the specific features of each of these CAF subtypes in greater detail.

2.1.1. Myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs)

myCAFs, originally identified in PDAC as contractile, matrix-producing fibroblasts (FAP+ αSMAhigh) marked by ACTA2, CTGF, and COL1A1, have since been recognized in various solid tumors via scRNA-seq, which broadly classifies them into two distinct subtypes despite study-to-study variation in gene expression profiles [7,20].

Category 1: Contractile/Pericyte-like myCAFs

The first group of myCAFs is defined by a contractile gene signature, including elevated expression of RGS5, MYH11, ACTA2, TAGLN, MYL9, and additional pericyte-associated markers such as NDUFA4L2 and ADIRF. These cells have been described in numerous studies [25]. Depending on the context, they have been labeled as contractile CAFs, stellate-like CAFs, MCAM+ CAFs, RGS5+ CAFs, or MYH11+ CAFs. However, recent findings suggest that their gene expression profiles may overlap with pericytes and other mural cells [25,26]. This has led some researchers to argue that these cells may not be true fibroblasts but rather pericyte-like cells, based on comparisons with normal muscular tissues [25]. Genes such as MYH11, ACTA2, MCAM, and TAGLN support their classification as mural cells. Consequently, some scRNA-seq analyses now propose distinguishing these as pericytes or vascular CAFs (vCAFs) rather than traditional myCAFs [17]. vCAFs, although similar to pericytes in terms of location (surrounding blood vessels) and gene expression (angiogenesis-related genes), show lower expression of RGS5 than true pericytes [21]. Proper identification and separation of RGS5+ MYH11+ populations is essential for accurate study of vascular cells and CAFs within tumors.

Category 2: ECM-Remodeling/Matrix myCAFs

The second major group of myCAFs is defined by high expression of collagen genes (e.g., COL1A1, COL10A1, COL11A1, CTHRC1), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP11), non-collagenous ECM proteins (POSTN, THBS2, VCAN, FN1), and signaling genes like SULF1 and INHBA. These cells have been described under multiple names: matrix CAFs, desmoplastic CAFs, ECM-remodeling CAFs, TGF-β-activated CAFs, and classical CAFs, among others. They are typically derived from resident fibroblasts and are found in collagen-dense regions of the tumor stroma [23]. Their gene profiles and location suggest a strong involvement in ECM remodeling, collagen production, and TGF-β-driven EMT. These fibroblasts enhance tumor invasion and cancer cell motility, and their positioning at the invasive tumor edge supports their role in metastasis [23].

In general, myCAFs are TGF-β–activated, contractile fibroblasts enriched in ACTA2, TAGLN, and collagen genes that localize near tumor clusters, remodel the ECM to stiffen tissue and block therapy penetration, and are found across multiple cancers including PDAC, RCC, breast, gastric, and colorectal tumors. Liu et al. detected a seven-gene signature (COL1A1, COL1A2, COL5A1, COL16A1, EMILIN1, LOXL1, LUM) associated with CAF infiltration in clear-cell RCC (ccRCC), correlating with advanced stage, higher grade and poor prognosis [27].

2.1.2. Inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs)

iCAFs are defined by a secretory phenotype, with high production of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL-6), chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Unlike myCAFs, iCAFs are usually found further from tumor cells and are activated through inteleukin-1/Janus kinases signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (IL-1/JAK/STAT3) signaling instead of TGF-β. These fibroblasts play key roles in suppressing immune responses and promoting EMT via paracrine signaling. In RCC, the presence of iCAFs has been linked to poor clinical outcomes and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors [5,25].

2.1.3. Antigen-Presenting CAFs (apCAFs)

apCAFs are a more recently discovered subset that express MHC class II molecules such as HLA-DRA, CD74, and CIITA, but notably lack costimulatory molecules, suggesting a potential role in modulating T-cell activity and promoting immune evasion. These fibroblasts have mainly been identified in PDAC and breast cancer, although their precise function within the TME remains an active area of investigation [7,8].

2.1.4. Emerging CAF Subtypes

Recent single-cell analyses have revealed diverse and functionally distinct CAF subtypes—including proliferative, interferon-responsive, metabolic, EMT-like, lipofibroblastic, tumor-like, and reticular-like CAFs—highlighting their plasticity and varied roles in tumor progression, immune response, and therapy outcomes [25]. Therefore, categorizing CAFs remains challenging, and the precise number of unique CAF subtypes has yet to be determined.

3. CAF-Mediated EMT and RCC

CAFs are key regulators of EMT, a process crucial for tumor invasion, metastasis, and resistance to therapy [20]. Through both paracrine signaling and extracellular-vesicle-mediated communication, CAFs initiate and sustain EMT in tumor cells across various cancer types, including RCC. The major CAF-induced signaling pathways contributing to EMT are summarized and presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Signaling Pathways Mediated by CAFs in EMT and Cancer Progression.

A pivotal genetic alteration in RCC is the loss of the Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene. The VHL gene is a key gene frequently altered in RCC, with mutations present in about 60% to 80% of patients diagnosed with clear cell renal carcinoma (ccRCC) [32]. This mutation leads to the accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α), which in turn upregulates several downstream factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). These signaling molecules actively recruit normal fibroblasts from the TME and induce their transformation into CAFs. Mechanistically, CAFs promote EMT in RCC by stimulating the phosphorylation of annexin A2, a multifunctional protein involved in cell motility, invasion, and cytoskeletal remodeling [32].

CAFs secrete IL-6, osteopontin (OPN), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and chemokines such as CXCL12 (also known as SDF-1) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), all of which play pivotal roles in influencing the behavior of RCC. These secreted molecules can initiate and sustain EMT, a key process in tumor invasion and metastasis. They activate several oncogenic signaling pathways in RCC cells, including the JAK/STAT3, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades. This activation triggers downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK, promoting cancer cell proliferation, survival, and migration. Importantly, the HGF/c-MET axis induces EMT by upregulating EMT transcription factors like Snail, Slug, and Twist while downregulating epithelial markers such as E-cadherin, thus enhancing invasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance [31,33]. The continuous interaction between CAF-secreted HGF and tumor c-MET creates a feedback loop that sustains tumor aggressiveness and remodeling of the TME (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The major signaling pathways and key activators in CAF-mediated tumor progression.

When the VHL gene is inactivated, it results in the stabilization of HIF1α and HIF2α, which in turn drives alterations in cellular metabolism, promotes angiogenesis, and facilitates EMT, invasion, and metastasis—all of which play key roles in the progression of ccRCC [34,35].

In the canonical Smad-dependent TGFβ signaling pathway, TGFβ ligands bind to the type II receptor (TβRII), which recruits and phosphorylates the type I receptor (TβRI, also known as ALK5 or ALK5-FL). This activation leads to the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3, which then form a complex with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus to regulate gene expression involved in processes such as EMT. The non-canonical TGFβ pathway operates independently of Smads and involves the nuclear translocation of the TβRI intracellular domain (TβRI-ICD or ALK5-ICD). Within the TME, CAFs secrete TGFβ, driving EMT in adjacent epithelial or cancer cells and promoting invasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Moreover, TGFβ acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine in settings such as renal inflammation [36].

Mechanistically, CAFs promote EMT in RCC by stimulating the phosphorylation of annexin A2 (ANXA2), a multifunctional protein involved in cell motility, invasion, and cytoskeletal remodeling. This phosphorylation is mediated through the secretion of growth factors such as HGF and IGF-1 by CAFs. These factors bind to their respective receptors-c-Met for HGF and IGF-1R for IGF-1-on the surface of RCC cells, leading to the activation of downstream signaling pathways such as MAPK and PI3K/AKT. As a result, ANXA2 undergoes phosphorylation, which facilitates cytoskeletal reorganization, loss of epithelial characteristics, and acquisition of mesenchymal traits. This cascade of events ultimately enhances the migratory and invasive potential of cancer cells, contributing to tumor progression and metastasis [37]. Additionally, TGFβ released by CAFs has been shown to induce EMT through an epigenetic process that involves the lncRNAs ZEB2NAT and HOTAIR [5,38]. Furthermore, MAPK signaling interacts synergistically with other EMT-related pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT3, amplifying the pro-metastatic phenotype of RCC cells in response to CAF-derived signals [35].

In RCC, tumor cells that undergo EMT not only gain migratory and invasive abilities but also promote remodeling of the TME by secreting pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors, such as TGF-β and IL-1β, which activate fibroblasts into CAFs. These CAFs, in turn, release molecules like HGF and IL-6 that reinforce EMT in tumor cells, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances tumor progression by supporting stemness, immune evasion, and metastasis while fostering a supportive stromal environment for cancer growth.

In patients with metastatic RCC, circulating tumor cells often exhibit elevated expression of CXCR4 and HIF1α, both of which are linked to increased metastatic capacity. Additionally, HIF-2α has been found to promote tumor growth in RCC xenograft models, particularly in cases of renal-origin lung metastases, by accelerating cell cycle progression. The EMT transcription factor Snail also plays a regulatory role in CAF activity, influencing tumor stiffness and enhancing cell motility. Beyond this, CAFs influence EMT in cancer cells through multiple mechanisms, including intercellular signaling, paracrine factor release, supporting tumor cell proliferation, stimulating angiogenesis, and modifying ECM stiffness—all of which contribute to tumor progression and dissemination [18,31].

CAFs influence RCC progression by altering metabolism, dampening immune responses, and contributing to therapy resistance. As RCC progresses, the number of CAFs increases, and the RME shows more stromal content and immune evasion. Specific proteins secreted by CAFs, such as MMP-2, MMP-9, and FAP, are linked to greater tumor aggressiveness and poorer survival, making them useful prognostic markers. CD248, a marker found only in activated fibroblasts, promotes an immunosuppressive tumor environment and is associated with worse outcomes in RCC. Furthermore, activation of FGF/FGFR signaling in CAFs has been tied to advanced disease and aggressive tumor traits, highlighting CAFs as key players and potential targets in RCC prognosis and therapy [18].

During tumor development, CAFs persistently secrete enzymes that crosslink the ECM, such as the lysyl oxidase (LOX) family and MMPs, facilitating ECM remodeling [39]. This process reorganizes collagen and fibronectin fibers, increasing tumor stiffness and thereby aiding RCC invasion and metastasis. Elevated expression of LOX family genes, including LOX and LOXL2, is associated with poorer survival outcomes in patients with ccRCC [40]. Functionally, LOX and LOXL2 enhance collagen stiffness, stabilize integrin α5β1, promote fiber formation, and inhibit protease and proteasome activity in ccRCC. Additionally, CAF-derived MMPs such as MMP-9 and MMP-2 contribute to tumor invasion and metastasis and serve as potential prognostic markers in ccRCC [41]. Notably, suppression of MMP-9 via microRNA mir-124 reduces RCC invasiveness in vitro [42]. MMP-13, regulated by TGF-β1, is more closely linked to RCC bone metastasis than to primary tumors or normal kidney tissue. In RCC, SDF-1 secreted by CAFs binds to the CXCR4 receptor on cancer cells, promoting tumor angiogenesis and metabolic regulation within the TME [41].

CAFs significantly contribute to EMT in RCC through the activation of the YAP/TAZ signaling pathway, which is central to the Hippo cascade. CAFs influence RCC cells by remodeling the ECM and secreting cytokines (like TGF-β and CTGF), which increase ECM stiffness and cytoskeletal tension. This cellular tension inhibits the activity of LATS1/2 kinases, allowing YAP/TAZ to translocate to the nucleus, where they drive the expression of EMT-related genes such as ZEB1, vimentin, and TWIST1, while suppressing E-cadherin. These changes promote tumor cell detachment, migration, and invasion, key features of metastatic RCC. Furthermore, CAF-derived exosomes containing YAP-activating signals, including ECM-modifying enzymes and regulatory miRNAs, may enhance mechanotransduction and stabilize YAP/TAZ, thereby supporting EMT progression and interaction with other signaling pathways like PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin, which reinforce EMT and stemness in RCC cells [31].

Several studies have highlighted the crucial role of cancer-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) in promoting EMT [29,43,44]. Wang et al. found that RCC stem cells release higher levels of CD103+ sEVs, which function as “pathfinders,” directing RCC cells to metastatic sites [43]. Deficiency of CD103+ sEVs significantly impairs RCC cells’ ability to colonize distant organs. These sEVs also carry miR-19b-3p, which targets PTEN in recipient cells, enhancing RCC metastasis by inducing EMT. Li et al. reported that apolipoprotein C1 (ApoC1) levels are abnormally high in ccRCC, with a negative correlation to survival [44]. They demonstrated that ApoC1 promotes EMT in ccRCC by activating STAT3, and sEVs transport ApoC1 to endothelial cells, stimulating EMT and boosting the proliferative, invasive, and metastatic properties of RCC cells. Furthermore, Jin et al. found that sEVs from RCC cells carry metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1), which regulates TFCP2L1 expression through the transcription factor ETS1, further promoting EMT in RCC cells [45].

In the TME, CAF-derived EVs are key contributors to the development of RCC. Fu et al. showed that sEVs released by CAFs are efficiently taken up by RCC cells, where they enhance cell invasiveness by increasing the expression of metastasis-related proteins such as fibronectin, N-cadherin, vimentin, MMP9, and MMP2 [30].

These sEVs also promote cell cycle progression, boosting RCC cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis, although the specific cargo responsible for these effects was not identified. Ding et al. discovered that CAF-derived sEVs are rich in miR-181d-5p, which, upon uptake by RCC cells, activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [46]. MiR-181d-5p targets the tumor suppressor RNF43, downregulating its expression and promoting cancer stemness and tumor growth. Additionally, CAF-derived sEVs carry miR-224-5p, which contributes to the malignant transformation of ccRCC cells. These studies underscore the crucial role of CAF-derived EVs in RCC progression, though more research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms and identify potential therapeutic targets [29].

4. Discussion and Future Research Directions

Considerable further investigation is required to define the full spectrum of CAF subpopulations in human cancers and to elucidate their distinct biological roles within the TME. A deeper understanding of their plasticity, origins, and interactions—particularly in RCC—is essential. Despite this, the extensive data collected so far positions the field to begin translating CAF-related discoveries into therapeutic strategies. The terminology used for CAFs can be confusing because similar CAF types are often given the same label across different cancers, while CAFs with comparable characteristics may receive different names. This lack of consistency complicates cross-cancer comparisons and makes it challenging to draw reliable conclusions about CAFs. In contrast, classifying CAFs based on their function is a more universal approach that remains consistent across various tissue types and species. Moreover, this functional classification allows CAFs to be grouped into meaningful categories more easily. Therefore, applying a functional classification system to CAFs in RCC could help standardize comparisons with CAFs from other cancers. Alternatively, researchers could adopt a gene expression–based strategy to develop a distinct and precise CAF classification specifically for RCC, despite the challenges involved. Additionally, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies in RCC have provided valuable insights into the tumor immune environment, cellular origins, tumor markers, and treatment responses [18].

It is generally accepted that CAFs represent a cellular condition rather than a distinct cell type, which helps explain their remarkable diversity and functional variability across different tumor contexts. However, the absence of specific markers for their identification poses a significant challenge for developing effective therapies that can selectively target CAFs in cancer [39].

Extensive research is still needed to fully characterize the diverse CAF subpopulations and their plasticity, especially in RCC, but current data lays a strong foundation for developing CAF-targeted therapies. Targeting key signaling pathways such as IL-6/JAK/STAT3 and TGF-β, along with modulating CAF-induced ECM remodeling, may provide more effective cancer treatment strategies by enhancing immune infiltration and reducing tumor progression and metastasis [47]. In RCC, CAFs drive EMT by remodeling the extracellular matrix, releasing profibrotic cytokines, and enhancing mechanical tension, all of which activate the Yes-associated protein and Transcriptional Coactivator with PDZ-binding Motif (YAP/TAZ) signaling pathway and promote the nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of EMT-associated genes. Additionally, CAF-derived exosomes and integration with other signaling pathways like PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin sustain EMT and stemness in RCC cells, making the YAP/TAZ pathway a key therapeutic target in RCC progression [48].

CAF-Targeting Therapeutic Strategies in RCC

Given the high degree of CAF heterogeneity and adaptability, focusing on specific signaling pathways or molecular drivers-rather than targeting particular CAF subtypes or their cells of origin-may offer a more effective treatment approach. Across different tumor types, iCAFs commonly exhibit increased IL6/IL6R signaling, making them viable candidates for IL-6–targeted therapies like siltuximab or tocilizumab. Additionally, since immunoregulatory CAFs can activate JAK/STAT signaling in tumor cells, targeting this pathway might serve as an effective component of combination therapies. Another promising strategy involves targeting ECM modifications induced by CAFs. In tumors with dense stroma, immune cell infiltration is often limited, diminishing the effectiveness of immunotherapies. Modulating CAF activity to normalize the ECM could improve immune cell access to tumors and enhance the efficacy of immunotherapeutic interventions [47]. Blocking IL-6 signaling using the IL 6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab may restore the effectiveness of anti-RCC therapies—such as interferon-alpha (IFN α) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)—which often lose efficacy due to therapy-induced IL-6-mediated resistance. In RCC models, combined treatment with tocilizumab and a TKI (e.g., sorafenib) suppressed tumor growth more effectively than TKI alone by inhibiting the IL-6–driven activation of the AKT mTOR pathway and angiogenesis. Likewise, in IFN α–resistant RCC cells, tocilizumab enhanced IFN α–induced anti-tumor activity by reversing IL-6–mediated STAT3 activation and improving STAT1 signaling. These promising preclinical findings suggest that clinical trials assessing combinations of IL-6R antibodies like tocilizumab with IFN α or TKIs may be warranted to overcome therapeutic resistance in RCC [49].

Targeting the interactions between CAFs and EMT represents a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment. Several approaches are currently being explored to interfere with the signaling pathways that mediate CAF-induced EMT and tumor progression. One key target is the TGF-β pathway, a major driver of EMT in cancer cells. TGF-β inhibitors such as galunisertib and fresolimumab have been developed to block TGF-β signaling and thereby inhibit EMT induction, reducing tumor invasiveness and metastasis [39,41]. These agents have shown efficacy in preclinical models and early-phase clinical trials, although their broad effects on normal tissue homeostasis remain a concern. Another important pathway involves IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, which is critical in the CAF-cancer cell crosstalk promoting EMT and immunosuppression. The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib has been tested to disrupt IL-6–mediated activation of STAT3, thereby attenuating EMT and the pro-tumorigenic functions of CAFs [39]. Despite promising results, resistance mechanisms and systemic immunosuppressive effects challenge its clinical application. Additionally, c-MET signaling, activated by HGF from CAFs, is crucial for EMT and tumor progression, with inhibitors like cabozantinib and crizotinib showing potential in targeting this pathway in solid tumors. However, while direct CAF depletion strategies also hold promise, clinical application faces challenges due to resistance and immunosuppressive effects, making c-MET inhibitors a more feasible approach to block CAF-driven EMT and tumor progression [50].

One notable approach involves targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a surface marker highly expressed on CAFs, using immunotherapies such as FAP-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells or antibody–drug conjugates [50]. While these methods can effectively reduce CAF populations, preclinical evidence suggests that complete CAF ablation may paradoxically accelerate tumor progression by disrupting the stromal barrier and altering immune surveillance [39,47]. Another critical perspective is understanding how CAF-induced EMT contributes to minimal residual disease and therapy resistance. EMT endows tumor cells with stem-like traits and quiescence, allowing them to evade cytotoxic therapies and later seed metastases. Targeting EMT plasticity through epigenetic inhibitors or YAP/TAZ pathway modulators could limit relapse risk. Future studies should explore how CAF-driven epigenetic reprogramming sustains EMT and identify vulnerabilities within this axis [51].

Exosomes hold substantial promise as versatile tools in the management of RCC. Clinically, they can be isolated non-invasively from blood or urine and contain specific miRNA signatures—such as serum exosomal miR-210 and miR-1233 for early detection and monitoring, and urinary miR 126 3p (especially when combined with other miRNAs) as a diagnostic marker with high sensitivity and specificity. On the therapeutic front, exosomes can be engineered to deliver a variety of bioactive cargos—including siRNAs, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunomodulatory molecules—with excellent biocompatibility, stability, and targeted delivery efficiency compared to conventional carriers. By integrating exosome-based biomarker detection and targeted drug delivery, precision and efficacy in RCC diagnosis and treatment can be significantly enhanced, offering a highly personalized approach to clinical care [52,53].

A thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving drug resistance and metabolic reprogramming mediated by EVs is essential for developing effective treatments for RCC. Targeting EVs and their specific cargo molecules, such as lncARSR and miR-31-5p, holds promise as potential therapeutic strategies to combat drug resistance and enhance the effectiveness of RCC therapies. However, additional research is needed to fully uncover the precise mechanisms by which EVs contribute to drug resistance and metabolic changes in RCC, as well as in other types of cancer [29].

Single-cell technologies, such as single-cell transcriptomics and proteomics, are powerful tools for uncovering cellular diversity and discovering more accurate biomarkers for targeted treatment. Importantly, each CAF subset’s interactions—not only with cancer cells but also with other stromal elements and among themselves—must be carefully studied to categorize them based on function. Furthermore, due to the varied origins of CAFs and their ability to change throughout tumor development, understanding how different CAF subtypes relate to each other—whether in hierarchical, parallel, or overlapping structures-would be highly informative. In this regard, reliable in vivo tumor models paired with genetic tools like the Cre–lox system provide valuable platforms for studying CAF function across different tumor stages. While much current research focuses on identifying tumor-promoting CAF subsets and selectively targeting them, it is equally important to identify tumor-suppressing CAF populations and understand how to preserve or enhance their functions. Promoting these beneficial CAFs or reprogramming harmful ones into supportive roles should be a key goal of future stroma-targeted therapies. There is increasing recognition that therapeutic strategies aimed at normalizing or reprogramming the tumor stroma into a more inactive or even tumor-inhibiting state could significantly improve clinical outcomes and patient survival. CAF-targeting therapies have struggled due to CAFs’ complexity, underscoring the need for precise, context-specific strategies using advanced tools to distinguish and modulate their diverse roles in cancer [54].

A comprehensive analysis integrating genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data could more precisely characterize gene expression patterns in CAFs and reveal key molecular mechanisms underlying their tumor-promoting roles in ECM remodeling in RCC.

5. Limitations in Understanding the Heterogeneity and Targeting of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in RCC

A limitation of this review is the insufficient exploration of the inherent complexity and heterogeneity of CAFs across different stages and subtypes of RCC. While CAFs are recognized as critical contributors to tumor progression, their diverse origins, dynamic interactions with the TME, and functional plasticity remain under-explored, making it challenging to identify consistent therapeutic targets. Additionally, the lack of specific and standardized markers for CAF identification complicates the development of targeted therapies and the ability to reliably assess CAF involvement in RCC progression. Future research should focus on refining CAF classification systems and examining the functional roles of distinct CAF subsets to improve treatment strategies and therapeutic outcomes.

6. Conclusions

CAFs represent a pivotal component of the TME, orchestrating tumor progression, therapy resistance, and metastatic dissemination through complex paracrine and mechanical interactions. Their ability to induce EMT underscores their role in enhancing tumor cell plasticity and aggressiveness. CAF classification in RCC is challenging due to their heterogeneity, overlapping markers, and context-dependent plasticity. Their interaction with EMT processes drives tumor progression, immune evasion, and resistance to therapies through pathways like TGF-β and IL-6/JAK/STAT3. Advancing high-resolution CAF profiling in RCC is essential for understanding their roles and developing targeted stromal therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.V. and A.B.T.; writing—original draft preparation: S.V., N.T.E. and K.Z.B.; writing—review and editing: S.V., A.B.T. and K.Z.B.; project administration: A.B.T. and N.T.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Union-Next Generation EU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No. BG-RRP-2.004-0009-C02.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval are not applicable to this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasorsa, F.; Rutigliano, M.; Milella, M.; Ferro, M.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Crocetto, F.; Tataru, O.S.; Autorino, R.; Battaglia, M.; Ditonno, P.; et al. Cellular and molecular players in the tumor microenvironment of renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fee, K.; Burley, A.; Stewart, S.; Wilkins, A. Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) to Optimize Radiation Responses. Cancer J. 2025, 31, e0776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Gieniec, K.A.; Wright, J.A.; Wang, T.; Asai, N.; Mizutani, Y.; Denda, S.; Sakai, K.; Tsuda, M.; Ikeda, H.; et al. The origin and contribution of cancer-associated fibroblasts in colorectal carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 890–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M. Cancer associated fibroblasts in cancer development and therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Wu, C.; Mao, H.; Gu, H.; Dong, H.; Yan, J.; Qi, Z.; Yuan, L.; Dong, Q.; Long, J. Subpopulations of cancer-associated fibroblasts link the prognosis and metabolic features of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Kieffer, Y.; Scholer-Dahirel, A.; Pelon, F.; Bourachot, B.; Cardon, M.; Sirven, P.; Magagna, I.; Fuhrmann, L.; Bernard, C.; et al. Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive environment in human breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 463–479.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calon, A.; Espinet, E.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Tauriello, D.V.F.; Iglesias, M.; Céspedes, M.V.; Sevillano, M.; Nadal, C.; Jung, P.; Zhang, X.H.F.; et al. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-β-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; et al. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumorigenesis of gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellinen, T.; Luomala, L.; Mattila, K.E.; Hemmes, A.; Välimäki, K.; Brück, O.; Paavolainen, L.; Kankkunen, E.; Nisén, H.; Järvinen, P.; et al. Fibroblast activation protein defines an aggressive, immunosuppressive EMT-associated tumor subtype in highly inflamed localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.S.; Kanugula, S.S.; Sudhir, S.; Pereira, M.P.; Jain, S.; Aghi, M.K. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, W.; Hao, W.; Gong, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qian, Z.; Xu, K.; Cai, W.; Gao, Y. CXCL3/TGF-β-mediated crosstalk between CAFs and tumor cells augments RCC progression and sunitinib resistance. iScience 2024, 27, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.D.; Dolan, B.; Laklouk, I.A.; Rassi, S.; Lozar, T.; Emamekhoo, H.; Wentland, A.L.; Lubner, M.G.; Abel, E.J. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment in renal cell carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppe, C.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Kranz, J.; Zhang, X.; Ziegler, S.; Perales-Patón, J.; Jansen, J.; Reimer, K.C.; Smith, J.R.; Dobie, R.; et al. Decoding myofibroblast origins in human kidney fibrosis. Nature 2021, 589, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camorani, S.; Hill, B.S.; Fontanella, R.; Greco, A.; Gramanzini, M.; Auletta, L.; Gargiulo, S.; Albanese, S.; Lucarelli, E.; Cerchia, L.; et al. Inhibition of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells homing towards triple-negative breast cancer microenvironment using an anti-PDGFRβ aptamer. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3595–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Cai, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shi, T.; Liu, W.; Mao, L.; Deng, B.; Ying, Z.; Gao, Y.; Luo, H.; et al. CAFs shape myeloid-derived suppressor cells to promote stemness of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma through 5-lipoxygenase. Hepatology 2022, 75, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, W.; Lu, J.; Anwaier, A.; Ye, D.; Zhang, H. Heterogeneity and function of cancer-associated fibroblasts in renal cell carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2023, 3, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlund, D.; Handly-Santana, A.; Biffi, G.; Elyada, E.; Almeida, A.S.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Corbo, V.; Oni, T.E.; Hearn, S.A.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbo, P.M., Jr.; Zang, X.; Zheng, D. Molecular features of cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes and their implication on cancer pathogenesis, prognosis, and immunotherapy resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 2636–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cords, L.; Tietscher, S.; Anzeneder, T.; Langwieder, C.; Rees, M.; de Souza, N.; Bodenmiller, B. Cancer-associated fibroblast classification in single-cell and spatial proteomics data. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yang, C.; Peng, A.; Sun, T.; Ji, X.; Mi, J.; Wei, L.; Shen, S.; Feng, Q. Pan-cancer spatially resolved single-cell analysis reveals the crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wan, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Ge, C.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, G.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic architecture and intercellular crosstalk of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Xia, X.; Huang, L.B.; An, H.; Cao, M.; Kim, G.D.; Chen, H.N.; Zhang, W.H.; Shu, Y.; Kong, X.; et al. Pan-cancer single-cell analysis reveals the heterogeneity and plasticity of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakova, A.N.; Lukina, M.M.; Anufrieva, K.S.; Bekbaeva, I.V.; Ivanova, O.M.; Shnaider, P.V.; Slonov, A.; Arapidi, G.P.; Shender, V.O. Exploring the diversity of cancer-associated fibroblasts: Insights into mechanisms of drug resistance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1403122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Splunder, H.; Villacampa, P.; Martínez-Romero, A.; Graupera, M. Pericytes in the disease spotlight. Trends Cell Biol. 2024, 34, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Zhan, Y.; Wu, B.; Pan, S. Identification of a gene signature for renal cell carcinoma-associated fibroblasts mediating cancer progression and affecting prognosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 604627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Paiva, R.; Gomes, I.; Casimiro, S.; Fernandes, I.; Costa, L. c-Met Expression in Renal Cell Carcinoma with Bone Metastases. J. Bone Oncol. 2020, 25, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, X.; Mao, Y.; Gan, R.; Chen, Z. Extracellular Vesicles in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Challenges and Opportunities Coexist. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1212101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Nie, H.; Gao, B.; Yin, F.; Wang, B.; Li, T.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; et al. Exosomes Derived from Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Regulate Cell Progression in Clear-Cell Renal-Cell Carcinoma. Nephron 2022, 146, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, B. Extracellular Matrix Stiffness: Mechanisms in Tumor Progression and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Li, G.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, B.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, G. The molecular code of kidney cancer: A path of discovery for gene mutation and precision therapy. Mol. Asp. Med. 2025, 101, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, R.; Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Su, P.; Liang, H.; Dong, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, K. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumour microenvironment of urinary system. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumder, S.; Higgins, P.J.; Samarakoon, R. Downstream Targets of VHL/HIF-α Signaling in Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Relevance. Cancers 2023, 15, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, L.; Mamtimin, M.; Braun, A.; Anders, H.J.; Andrassy, J.; Gudermann, T.; Mammadova-Bach, E. Inflammatory Networks in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Bai, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tuoheti, K.; Yisha, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Lu, P.; Liu, T. TGFBI promotes proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal cell carcinoma through PI3K/AKT/mTOR/HIF-1α pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M.; Ma, Y.; Ye, X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and EGFR-TKI resistance of non-small cell lung cancers via HGF/IGF-1/ANXA2 signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Lu, Q.; Shen, B.; Huang, X.; Shen, L.; Zheng, X.; Huang, R.; Yan, J.; Guo, H. TGFβ1 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition of bladder cancer cells through lncRNA-ZEB2NAT. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokhanbigli, S.; Haghi, M.; Dua, K.; Oliver, B.G.G. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Cell Surface Markers as Potential Biomarkers or Therapeutic Targets in Lung Cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zheng, L.; Lu, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Z. Comprehensive analysis on the expression levels and prognostic values of LOX family genes in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 8624–8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Yiu, W.H.; Tang, P.M.; Tang, S.C. New Insights into Fibrotic Signaling in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1056964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, L.D.; Sun, M.C.; Gu, W.D.; Geng, H.Z. Over-expression of mir-124 inhibits MMP-9 expression and decreases invasion of renal cell carcinoma cells. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 6308–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yang, G.; Zhao, D.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Peng, Q.; Wang, H.; Fang, R.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; et al. CD103 Positive CSC Exosome Promotes EMT of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Role of Remote MiR-19b-3p. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-L.; Wu, L.-W.; Zeng, L.-H.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Lin, N.-M. ApoC1 promotes the metastasis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via activation of STAT3. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6203–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Shi, L.; Li, K.; Liu, W.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q. Mechanism of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in regulating renal cell carcinoma progression by the delivery of MALAT1. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 46, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Diao, W.; Kan, Y.; Cao, W.; Chen, W.; Jiang, B.; Qin, H.; Gao, J.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote the Stemness and Progression of Renal Cell Carcinoma via Exosomal miR-181d-5p. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, D.; Ben Shmuel, A.; Erez, N.; Scherz Shouval, R. Cancer Associated Fibroblasts in the Single Cell Era. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ten Dijke, P. Harnessing Epithelial Mesenchymal Plasticity to Boost Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Koguchi, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Onagi, A.; Tanji, R.; Takinami-Honda, R.; Hoshi, S.; Onoda, M.; Kurimura, Y.; Hata, J.; et al. Interleukin-6 induces drug resistance in renal cell carcinoma. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2018, 64, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhong, M.; Zhong, H.; Ruan, R.; Xiong, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Deng, J. Targeting HGF/c-MET signaling to regulate the tumor microenvironment: Implications for counteracting tumor immune evasion. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, V.; Higgins, P.J.; Samarakoon, R. Emerging Role of Hippo-YAP (Yes-Associated Protein)/TAZ (Transcriptional Coactivator with PDZ-Binding Motif) Pathway Dysregulation in Renal Cell Carcinoma Progression. Cancers 2024, 16, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavinia, A.; Razavinia, A.; Jamshidi Khalife Lou, R.; Ghavami, M.; Shahri, F.; Tafazoli, A.; Khalesi, B.; Hashemi, Z.S.; Khalili, S. Exosomes as novel tools for renal cell carcinoma therapy, diagnosis, and prognosis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussios, S.; Devo, P.; Goodall, I.C.A.; Sirlantzis, K.; Ghose, A.; Shinde, S.D.; Papadopoulos, V.; Sanchez, E.; Rassy, E.; Ovsepian, S.V. Exosomes in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Renal Cell Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhuang, Q. Cancer Associated Fibroblasts: From Basic Science to Anticancer Therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).